community foundations

1/66

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

67 Terms

communication in nursing practice

a life long nursing process

essential part is having what

assertiveness allows to build relationships with families and multidisciplinary members

therapeutic communication

occurs within healing relationship between nurse and patient

caring relationships are at the core of nursing practice

true

breakdown of communication is major cause of medical Errors

true

NPSG

national patient safety goals

national patient safety goals

identify patient correctly

improve staff communication

use medicine safely

use alarms safely

prevent infection

identify patient safety risks

prevent mistake in surgery

communication and interpersonal relationships

communication is the means to establish helping trust relationship

ability to relate to others very important for interpersonal communication

developing this skill requires communication process and communication experience

developing communication skills

those with critical thinking skills, clincial judgment are best communicators

critical thinking can what with patient interaction?

helps to overcome perceptual biases or stereotypes

clinical decision is always contextual

the nurses communication can result in both harm and good

intrapersonal

occurs within self talk

interpersonal

one to one between two people

small group

interactions with small number of people

public

interaction with an audience

electronic

portals, text email

referent

motivates one person to communicate with another. In a health care setting, sights, sounds, sensations, perceptions, and ideas are examples of cues that initiate the communication process

. Knowing a stimulus or referent that initiates communication allows you to develop and organize messages more efficiently.

For example, a patient’s request for help prompted by difficulty in breathing causes a different response than does a patient’s request for pain medication.

sender

is the person who encodes and delivers a message,

The sender’s message acts as a referent for the receiver. Transactional communication involves the role of sender and receiver switching back and forth between nurse and patient.

receiver

is the person who receives and decodes the message.

message

is the content of the communication. It contains verbal and nonverbal expressions of thoughts and feelings. Effective messages are clear, direct, timely, and in understandable language.

Individuals with cognitive disorders (e.g., confusion, dementia) or communication barriers may need assistance (e.g., hearing aids, interpreters, or pictures) to clarify information to understand messages sent and received

channels

to send and receive messages through visual, auditory, and tactile senses. Facial expressions send visual messages; spoken words travel through auditory channels. Touch uses tactile channels. Individuals usually understand a message more clearly when the sender uses more channels to send it.

feedback

is the message a sender receives from the receiver. It indicates the extent to which the receiver understood the meaning of the sender’s message. Feedback occurs continuously between a sender and receiver.

A sender seeks verbal and nonverbal feedback to evaluate the receiver’s response and effectiveness of a communicated message. The type of feedback a sender or receiver gives depends on factors such as background, prior experiences, education, attitudes, cultural beliefs, and self-esteem. A sender and receiver need to be sensitive and open to each other’s messages, to clarify the messages, and to modify behavior accordingly for successful communication.

interpersonal values

factors within both the sender and receiver that influence communication. Perception provides a uniquely personal view of reality formed by an individual’s culture, expectations, and experiences.

Each person senses, interprets, and understands a communicated message differently. A nurse says, “You haven’t been talking very much since your family left. Is there something on your mind?

environment

the setting for sender-receiver interaction.

An effective communication setting provides participants with physical and emotional comfort and safety. Noise, temperature extremes, distractions, and lack of privacy or space create confusion, tension, and discomfort.

Environmental distractions are common in health care settings and interfere with messages sent between people. You control the environment as much as possible to create favorable conditions for effective communication.

communication must be

congruent to verbal and non verbal and vocal and visual,

*non verbal more important

nurse patient caring relationships

nurses need self-awareness, motivation, empathy and social skills to build helping therapeutic relationships

aring therapeutic relationships are the foundation of clinical nursing practice. In such relationships you assume the role of a professional who cares about each patient and the patient’s unique health needs, human responses, and patterns of living. T

therapeutic relationships

promote a psychological climate for positive change and growth, such as your patients’ ability to attain health-related outcomes (Arnold and Boggs, 2020).

The outcomes of a therapeutic relationship focus on a patient achieving optimal personal growth related to personal identity, ability to form relationships, and ability to satisfy needs and achieve personal goals

Nurse family relationships

the same principles that guide communication with family units, but family communication also requires understanding of the complexities of family dynamics needs and relationships

Many nursing situations, especially those in community and home care settings, require you to form caring relationships with entire families.

Nurse health team relationships

effective communication with other members of the HC team affects patient outcomes patient safety and work environment

SBAR

SACCIA

lateral violence- bullying in workplace increases patient safety risk

Effective communication with other members of the health care team affects patient outcomes, patient safety, and the work environment (Hannawa, 2018). Problems occur when communication is inconsistent, inaccurate, not timely, and incomplete. Patients moving from one nursing unit to another or from one provider to another are situations in which miscommunication can easily occur.

nurse community relationships

share information and discuss issues important to community health

Many nurses form relationships with community groups by participating in local organizations, volunteering for community service, or becoming politically active.

As a nurse, learn to establish relationships with your community to be an effective change agent. Providing clear and accurate information to members of the public is the best way to prevent errors, reduce resistance, and promote change

pre-interaction phase

occurs before meeting the patient

Review available data, including the medical and nursing history (e.g., ability of patient to communicate, pathology of any speech mechanisms, medications affecting mood, reports of previous behavior problems).

• Talk to other caregivers who have information about the patient.

• Anticipate health concerns or issues that arise.

• Identify a location and setting that fosters comfortable, private interaction.

• Plan enough time for the initial interaction.

orientation phase

when the nurse and the patient meet and get to know each other

Set the tone for the relationship by adopting a warm, empathetic, caring manner. Sit down next to the patient if possible.

• Recognize that the initial relationship is often superficial, uncertain, and tentative.

• Expect the patient to test your competence and commitment.

• Let the patient know when to expect the relationship to be terminated.

• Closely observe the patient and expect to be closely observed by the patient.

• Begin to make inferences and form judgments about patient messages and behaviors.

• Assess the patient’s health status.

• Prioritize the patient’s problems and identify expected outcomes.

• Clarify the patient’s and your roles.

• Form contracts with the patient that specify who will do what.

working phase

when the nurse and the patient work together to solve problems and accomplish goals

Encourage and help the patient express feelings about health.

• Encourage and help the patient with self-exploration.

• Provide information needed to understand and change behavior.

• Collaborate with the patient to set individualized outcomes.

• Take action to meet the outcomes set with the patient.

• Use therapeutic communication skills to facilitate successful interactions.

• Use appropriate self-disclosure and confrontation.

termination phase

occurs at the end of the relationship

Remind the patient that termination is near.

• Evaluate achievement of expected outcomes with the patient.

• Reminisce about the relationship with the patient.

• Separate from the patient by relinquishing responsibility for care.

• Achieve a smooth transition for the patient to other caregivers as needed.

MI

motivational interviewing,

) is a technique that encourages patients to share their thoughts, goals, beliefs, fears, and concerns with the aim of changing their behavior.

MI provides a way of working with patients who may not seem ready to make behavioral changes that are considered necessary by their health practitioners. You can use it to evoke change talk, which links to improved patient outcomes (Brown et al., 2018; Magil et al., 2019).

For example, an interviewer uses information about a patient’s personal goals with respect to maintaining health to promote the patient’s adherence to a new medication or an exercise plan, or adopt an alcohol moderation program. It is important to incorporate what the patient wants or perceives is important to be successful in achieving change. T

he interviewing is delivered in a nonjudgmental, guided communication approach. When using MI, a nurse tries to understand a patient’s motivations and values using an empathic and active listening approach. The nurse identifies differences between a patient’s current health goals and behaviors and current health status. The patient is supported even though a phase of resistance and ambivalence often occurs. Communication then focuses on recognizing the patient’s strengths and supporting those strengths to make positive changes.

5 general principles of motivational interviewing

express empathy through reactive listening

develop discrepancy between clients’ goals or values and their current behavior

roll with resistance and direct confrontation

roll with resistance

support self efficacy an optimism

this strategy elicit personally relevant to reasons to change

elements of professional communication

appearance demeanor and behavior

courtesy

use of names

trustworthiness

autonomy and responsibility

assertiveness

ADIET

acknlowdge

introduce

duration

explian

thank u

therapeutic communication

purposeful use of communication to build and maintain helping relationships with clients and families and significant others

characteristics of therapeutic communication

patient centered -not social or reciprocal

purposeful, planned and goal directed

essential components of therapeutic communication include

time

attending behaviors

caring attitude

honesty

trust

empathy

nonjudgmental attitude

active listening be where ur feet are

being attentive to what a patient is saying both verbally and non-verbally

facilitates patient communication and enhances trust

SURETY

sit facing the patient

uncross arms and legs

relax

eye contact

touch

your intuition

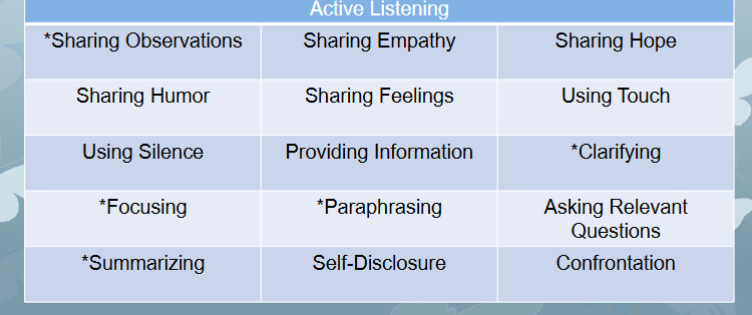

therapeutic communication

techniques are specific responses that encourage the expression of feelings and idea and covey acceptance and respect

sharing observations

Nurses make observations by commenting on how the other person looks, sounds, or acts. Stating observations often helps a patient communicate without the need for extensive questioning, focusing, or clarification. This technique can help start a conversation with a patient who is quiet or withdrawn. Do not state observations that will embarrass or anger a patient, such as telling someone, “You look a mess!” Even if you make such an observation with humor, the patient can become resentful.

Sharing observations differs from making assumptions, which means drawing unnecessary conclusions about the other person without validating them. Making assumptions puts a patient in the position of having to contradict you. Examples include interpreting a patient’s fatigue as depression or assuming that untouched food indicates lack of interest in meeting nutritional intake goals. Making observations is a gentler and safer technique: “You look tired . . .,” “You seem different today . . .,” or “I see you haven’t eaten anything.

sharing empathy

Empathy is the ability to understand and accept another person’s reality, accurately perceive feelings, and communicate this understanding to the other. This is a therapeutic communication technique that enables you to understand a patient’s situation, feelings, and concerns (Lorié, 2017). To express empathy, you reflect that you understand and feel the importance of the other person’s communication.

Empathetic understanding requires you to be sensitive and imaginative, especially if you have not had similar experiences. Strive to be empathetic in every situation because it is a key to unlocking concern and communicating support for others. Statements reflecting empathy are highly effective because they tell a person that you heard both the emotional and the factual content of the communication.

Empathetic statements are neutral and nonjudgmental and help establish trust in difficult situations. For example, a nurse says to an angry patient who has low mobility after a stroke, “It must be very frustrating to not be able to do what you want.”

sharing hope

Nurses recognize that hope is essential for healing and learn to communicate a “sense of possibility” to others. Appropriate encouragement and positive feedback are important in fostering hope and self-confidence and for helping people achieve their potential and reach their goals.

Foster hope by commenting on the positive aspects of the other person’s behavior, performance, or response. Sharing a vision of the future and reminding others of their resources and strengths also strengthen hope. Reassure patients that there are many kinds of hope and that meaning and personal growth can come from illness experiences. For example, a nurse says to a patient discouraged about a poor prognosis, “I believe that you’ll find a way to face your situation because I’ve seen your courage and creativity.”

sharing humor

Humor is an important but often underused resource in nursing interactions. It is a coping strategy that can reduce anxiety and promote positive feelings (Mota Sousa et al., 2019). It is a perception and attitude in which a person can experience joy even when facing difficult times. It provides emotional support to patients and professional colleagues and humanizes the illness experience. It enhances teamwork and relieves tension. Bonds develop between people who laugh together (Mills et al., 2019). Patients use humor to release tension, cope with fear related to pain and suffering, communicate a fear or need, or cope with an uncomfortable or embarrassing situation. The aim of using humor as a health care provider is to bring hope and joy to a situation and enhance a patient’s well-being and the therapeutic relationship (Mota Sousa et al., 2019). It makes you seem warmer and more approachable. Use humor during the orientation phase to establish a therapeutic relationship and during the working phase as you help a patient cope with a situation.

You will care for patients from different cultural backgrounds. Humor often has a cultural context. When you interact with patients, be sensitive and realize that they may misunderstand or misinterpret jokes and statements meant to be humorous, and you may decide that humor is inappropriate for a particular patient (Giger and Haddad, 2021). It is never appropriate, with any patient, to joke about sexual orientation, race, economic status, disability, or any cultural attribute.

Health care professionals sometimes use a kind of dark, negative humor after difficult or traumatic situations to deal with unbearable tension and stress. This coping humor has a high potential for misinterpretation as uncaring by people not involved in the situation. For example, nursing students are sometimes offended and wonder how staff are able to laugh and joke after unsuccessful resuscitation efforts. When nurses use coping humor within earshot of patients or their loved ones, great emotional distress results.

sharing feelings

Emotions are subjective feelings that result from one’s thoughts and perceptions. Feelings are not right, wrong, good, or bad, although they are pleasant or unpleasant. If individuals do not express feelings, stress and illness may worsen. Help patients express emotions by making observations, acknowledging feelings, encouraging communication, giving permission to express “negative” feelings, and modeling healthy emotional self-expression. At times patients will direct their anger or frustration prompted by their illness toward you. Do not take such expressions personally. Acknowledging patients’ feelings communicates that you listened to and understood the emotional aspects of their illness situation.

When you care for patients, be aware of your own emotions because feelings are difficult to hide. Students sometimes wonder whether it is helpful to share feelings with patients. Sharing emotions makes nurses seem more human and brings people closer. It is appropriate to share feelings of caring or even to cry with others if you are in control of the expression of these feelings and express them in a way that does not burden the patient or break confidentiality. Patients are perceptive and sense your emotions. It is usually inappropriate to discuss personal emotions such as anger or sadness with patients. A social support system of colleagues is helpful. Employee assistance programs, peer group meetings, and the use of interprofessional teams, such as social work and pastoral care, provide other means for nurses to safely express feelings away from patients.

using touch

Because of modern fast-paced technical environments in health care, nurses face major challenges in bringing the sense of caring and human connection to their patients (see Chapters 7 and 32). Touch is one of the most potent and personal forms of communication. It expresses concern or caring to establish a feeling of connection and promote healing (Varcarolis and Fosbre, 2021). Touch conveys many messages, such as affection, emotional support, encouragement, tenderness, and personal attention. When performing nursing procedures, a gentle approach to touch conveys competence. Comfort touch such as holding a hand is especially important for patients who are vulnerable or experiencing severe illness with its accompanying physical and emotional losses

Some students initially find giving intimate care to be stressful, especially when caring for patients of the opposite gender. They learn to cope with intimate contact by changing their perception of the situation. Because much of what nurses do involves touching, you need to learn to be sensitive to others’ reactions to touch and use it wisely. When performing a nursing procedure that involves touching sensitive areas of the body, let the patient know what you are going to do before touching. For example, as you prepare to provide perineal hygiene or cleanse a site for a urinary catheter insertion say, “I am going to gently pull the skin around the area where you urinate so I can get a better view and cleanse correctly. This will not be painful.” Touch should always be as gentle or as firm as needed and delivered in a comforting, nonthreatening manner. Sometimes you withhold touch for highly suspicious or angry persons who respond negatively or even violently to you.

Nurses need to be aware of patients’ nonverbal cues and ask permission before touching them to ensure that touch is an acceptable way to provide comfort. Some individuals may be sensitive to physical closeness and uncomfortable with touch. When this occurs, share the information with other nurses who will care for the patient. Nurses should be aware of a patient’s concern and act accordingly. A nod, gesture, body position, or eye contact can also convey interest and acceptance of touch, which promotes a bonding moment with a patient (Varcarolis and Fosbre, 2021).

Using silence.

It takes time and experience to become comfortable with silence. Most people have a natural tendency to fill empty spaces with words, but sometimes these spaces really allow time for a nurse and patient to observe one another, sort out feelings, think about how to say things, and consider what has been communicated. Silence prompts some people to talk. It allows a patient to think and gain insight (Varcarolis and Fosbre, 2021). In general, allow a patient to break the silence, particularly when the patient has initiated it.

Silence is particularly useful when people are confronted with decisions that require much thought. For example, it helps a patient gain the necessary confidence to share the decision to refuse medical treatment. It also allows the nurse to pay attention to nonverbal messages, such as worried expressions or loss of eye contact. Remaining silent demonstrates patience and a willingness to wait for a response when the other person is unable to reply quickly. Silence is especially therapeutic during times of profound sadness or grief.

providing information

Providing relevant information tells other people what they need or want to know so that they are able to make decisions, experience less anxiety, and feel safe and secure. It is also an integral aspect of health teaching (see Chapter 25). It usually is not helpful to hide information from patients, particularly when they seek it. If a health care provider chooses to withhold information, it becomes your role to explain and clarify a situation with the patient so as to not conflict with the health care provider’s choice. However, patients have a right to know about their health status and what is happening in their environment. Information of a distressing nature needs to be communicated with sensitivity, at a pace appropriate to a patient’s ability to absorb it, and in general terms at first: “John, your heart sounds have changed from earlier today, and so has your blood pressure. I’ll let your doctor know.” A nurse provides information that enables others to understand what is happening and what to expect: “Mrs. Evans, John is getting an echocardiogram right now. This test uses painless sound waves to create a moving picture of his heart structures and valves and should tell us the effect, if any, of his murmur on his heart.”

clarifying

To check whether you understand a message accurately, restate an unclear or ambiguous message to clarify the sender’s meaning. In addition, ask the other person to rephrase it, explain further, or give an example of what the person means. Without clarification you may make invalid assumptions and miss valuable information. Despite efforts at paraphrasing, you still may not understand a patient’s message. Let the patient know if this is the case: “I’m not sure I understand what you mean by ‘sicker than usual.’ What is different now?”

focusing

Focusing involves centering a conversation on key elements or concepts of a message. If conversation is vague or rambling or patients begin to repeat themselves, focusing is a useful technique. Do not use focusing if it interrupts patients while they are discussing important issues. Rather, use it to guide the direction of conversation to important areas: “We’ve talked a lot about your medications; now let’s look more closely at the trouble you’re having in taking them on time.”

paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is restating another’s message more briefly using one’s own words. Through paraphrasing you send feedback that lets patients know that they are actively involved in the search for understanding and clarity. Accurate paraphrasing requires practice. If the meaning of a message is changed or distorted through paraphrasing, communication becomes ineffective. For example, a patient says, “I’ve been overweight all my life and never had any problems. I can’t understand why I need to be on a diet.” Paraphrasing this statement by saying “You don’t care if you’re overweight” is incorrect. It is more accurate to say, “You’re not convinced that you need to make different food choices because you’ve stayed healthy.

Validation.

Validation is a technique that nurses use to recognize and acknowledge a patient’s thoughts, feelings, and needs. Patients and families know they are being heard and taken seriously when the caregiver addresses their issues. For example, a nurse validates a patient’s comments by saying, “Tell me if I understand your concerns regarding your surgery. You’re worried that you will not be able to do some of the things you could do before your surgery.” This type of statement enables a nurse to convey empathy and interest in the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and perceptions.

asking relevant questions

Ask relevant questions to seek information needed for decision making. Ask only one question at a time, and fully explore one topic before moving to another area. During patient assessment you ask questions that follow a logical sequence and usually proceed from general to more specific. Open-ended questions allow patients to take the conversational lead and introduce pertinent information about a topic. For example, “Tell me what is your biggest problem at the moment?” Use focused questions when more specific information is needed in an area: “How has your pain affected your life at home?” Allow patients to respond fully to open-ended questions before asking more focused questions. Closed-ended questions elicit a yes, no, or one-word response: “How many times a day are you taking pain medication?” Although they are helpful during assessment, they are generally less useful during therapeutic exchanges.

Sometimes asking too many questions is dehumanizing. Seeking factual information does not allow a nurse or patient to establish a meaningful relationship or deal with important emotional issues. It is a way for a nurse to ignore uncomfortable areas in favor of more comfortable, neutral topics. A useful exercise is to try to converse without asking the other person a single question. By using techniques such as giving general leads (“Tell me about . . .”), making observations, paraphrasing, focusing, and providing information, you discover important information that would have remained hidden if you had limited the communication process to questions alone

Asking relevant questions.

Ask relevant questions to seek information needed for decision making. Ask only one question at a time, and fully explore one topic before moving to another area. During patient assessment you ask questions that follow a logical sequence and usually proceed from general to more specific. Open-ended questions allow patients to take the conversational lead and introduce pertinent information about a topic. For example, “Tell me what is your biggest problem at the moment?” Use focused questions when more specific information is needed in an area: “How has your pain affected your life at home?” Allow patients to respond fully to open-ended questions before asking more focused questions. Closed-ended questions elicit a yes, no, or one-word response: “How many times a day are you taking pain medication?” Although they are helpful during assessment, they are generally less useful during therapeutic exchanges.

Sometimes asking too many questions is dehumanizing. Seeking factual information does not allow a nurse or patient to establish a meaningful relationship or deal with important emotional issues. It is a way for a nurse to ignore uncomfortable areas in favor of more comfortable, neutral topics. A useful exercise is to try to converse without asking the other person a single question. By using techniques such as giving general leads (“Tell me about . . .”), making observations, paraphrasing, focusing, and providing information, you discover important information that would have remained hidden if you had limited the communication process to questions alone

Self-disclosure.

Self-disclosures are subjectively true personal experiences about the self that are intentionally revealed to another person. This is not therapeutic for a nurse; rather it shows a patient that the nurse understands his experiences and that they are not unique. You choose to share experiences or feelings that are like those of the patient and emphasize both the similarities and differences. This kind of self-disclosure is indicative of the closeness of the nurse-patient relationship and indicates respect for the patient. You offer self-disclosure as an expression of sincerity and honesty; it is an aspect of empathy (Lorié, 2017). Self-disclosures need to be relevant and appropriate and made to benefit the patient rather than yourself. Use them sparingly so that the patient is the focus of the interaction.

Confrontation.

When you confront someone in a therapeutic way, you help the other person become more aware of inconsistencies in feelings, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Varcarolis and Fosbre, 2021). This technique improves patient self-awareness and helps the patient recognize growth and deal with important issues. Use confrontation only after you have established trust and do it gently with sensitivity: “You say you’ve already decided what to do, yet you’re still talking a lot about your options.”

no therapeutic

special communication considerations

patients who cannot speak clearly: listen actively ask yes or no questions don’t interrupt

Cognitive impairment: use simple sentences, avoid long explanations, allow time for response, include family

hearing impairment: check for hearing aid, provide if available reduce environment noise, get patients attention before speaking face patient with mouth visible , use normal tine, don’t shout

visual impairment: check use of glasses , provide , identify urself,

unresponsive: call by their name use touch and words speak as if they could hear u explain and avoid talking over

patients who do not speak English: establish mehtod to requst for help communication aids use interpeter/family

older folk

avoid demeaning words or elder talk

standardizing communication

promotes patient safety by helping communicate shared set of expectations

allows for concise and structured format

improves efficiency and accuracy

SBAR

situation: room name what the problem is

background: diagnosis date history code

assessment: what did u think see include peritnent info fidnings and concerns

recommendation : what do u think shoudl be the follow up or concern

if i: included its identify or introduce

who u are and role

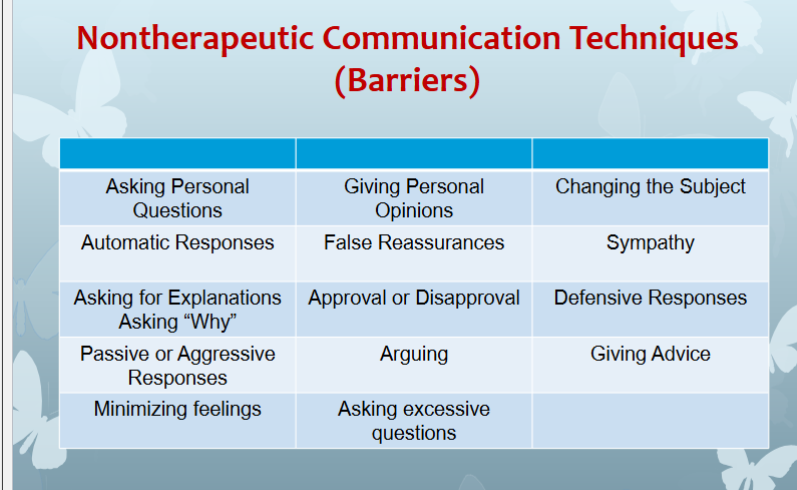

non therapeutic

Asking personal questions.

“Why don’t you and John get married?” “Is it true your wife does not agree with your decision?” Asking personal questions that are not relevant to a situation simply to satisfy your curiosity is inappropriate professional communication. Such questions are nosy, invasive, and unnecessary. If patients wish to share private information, they will. To learn more about a patient’s interpersonal roles and relationships, ask questions such as “How would you describe your relationship with John?”

Asking for explanations.

“Why are you so anxious?” Some nurses are tempted to ask patients why they believe, feel, or act in a certain way. Patients frequently interpret “why” questions as accusations or think nurses know the reasons and are simply testing them. Regardless of a patient’s perception of your motivation, asking “why” questions causes resentment, insecurity, and mistrust. If you need additional information, it is best to phrase a question to avoid using the word “why.” For example, “You seem upset. What’s on your mind?” is more likely to help an anxious patient communicate.

Approval or disapproval.

“You should not even think about stopping your cancer treatments.” Do not impose your own opinions, attitudes, values, beliefs, and moral standards on others while in the professional helping role. Other people have the right to be themselves and make their own decisions. Judgmental responses often contain terms such as should, ought, good, bad, right, or wrong. Agreeing or disagreeing sends the subtle message that you have the right to make value judgments about patient decisions. Approving implies that the behavior being praised is the only acceptable one. Often a patient shares a decision with you not to seek approval but to provide a means to discuss feelings. Disapproval implies that the patient needs to meet your expectations or standards. Instead, help patients explore their own beliefs and decisions. For example, the response “Have you had the opportunity to talk to your doctors about stopping cancer treatments? Tell me more about your thoughts” gives the patient a chance to express ideas or feelings without fear of being judged.

Defensive responses.

“No one here would intentionally lie to you.” Becoming defensive in the face of criticism implies that the other person has no right to an opinion. The sender’s concerns are ignored when the nurse focuses on the need for self-defense, defense of the health care team, or defense of others. When patients express criticism, listen to what they have to say. Listening does not imply agreement. Listen nonjudgmentally to discover reasons for a patient’s anger or dissatisfaction. By avoiding a defensive attitude, you are able to defuse anger and uncover deeper concerns. A better response would be “You believe that people are dishonest with you. It must be hard to trust anyone.”

Passive or aggressive responses.

“Things are bad, and there is nothing I can do about it.” “Things are falling apart, and it is all your fault.” Passive responses serve to avoid conflict or sidestep issues. They reflect feelings of sadness, depression, anxiety, powerlessness, and hopelessness. Aggressive responses provoke confrontation at the other person’s expense. They reflect feelings of anger, frustration, resentment, and stress. Nurses who lack assertive skills also use triangulation (i.e., complaining to a third party rather than confronting the problem or expressing concerns directly to the source). This lowers team morale and draws others into the conflict situation. Assertive communication is a far more professional approach for a nurse to take.

Arguing.

“How can you say you didn’t sleep a wink when I heard you snoring all night long?” Challenging or arguing against perceptions denies that they are real and valid. A skillful nurse gives information or presents reality in a way that avoids argument, with a statement such as “You feel as if you did not get any rest at all last night, even though I thought you slept well since I heard you snoring.”

non therapeutic 2

Giving personal opinions.

“If I were you, I would put your mother in a nursing home.” When a nurse gives a personal opinion, it takes decision making away from the other person. It inhibits spontaneity, stalls problem solving, and creates doubt. Personal opinions differ from professional advice. At times people need suggestions and help to make choices. Suggestions that you present are options; the other person makes the final decision. Remember that the problem and its solution belong to the other person and not to you. A much better response is “Let’s talk about the options available for your mother’s care.” The nurse also should not make promises to a patient about situations that require collaboration. For example, “I cannot recommend that you stop taking the medications because of your side effects, but I would be happy to inform your primary care provider and ask whether a change in medication is appropriate.”

Sympathy.

“I’m so sorry about your mastectomy; you probably feel devastated.” Sympathy is concern, sorrow, or pity felt for another person. A nurse often takes on a patient’s problems as if they were his or her own. Sympathy is a subjective look at another person’s world that prevents a clear perspective of the issues confronting that person. If a nurse overidentifies with a patient, objectivity is lost, and the nurse is unable to help the patient work through the situation (Varcarolis and Fosbre, 2021). Although sympathy is a compassionate response to another’s situation, it is not as therapeutic as empathy. A nurse’s own emotional issues sometimes prevent effective problem solving and impair good judgment. A more empathetic approach is “The loss of a breast is a major change. Do you feel comfortable talking about how it will affect your life?”

Asking for explanations.

“Why are you so anxious?” Some nurses are tempted to ask patients why they believe, feel, or act in a certain way. Patients frequently interpret “why” questions as accusations or think nurses know the reasons and are simply testing them. Regardless of a patient’s perception of your motivation, asking “why” questions causes resentment, insecurity, and mistrust. If you need additional information, it is best to phrase a question to avoid using the word “why.” For example, “You seem upset. What’s on your mind?” is more likely to help an anxious patient communicate.

Approval or disapproval.

“You should not even think about stopping your cancer treatments.” Do not impose your own opinions, attitudes, values, beliefs, and moral standards on others while in the professional helping role. Other people have the right to be themselves and make their own decisions. Judgmental responses often contain terms such as should, ought, good, bad, right, or wrong. Agreeing or disagreeing sends the subtle message that you have the right to make value judgments about patient decisions. Approving implies that the behavior being praised is the only acceptable one. Often a patient shares a decision with you not to seek approval but to provide a means to discuss feelings. Disapproval implies that the patient needs to meet your expectations or standards. Instead, help patients explore their own beliefs and decisions. For example, the response “Have you had the opportunity to talk to your doctors about stopping cancer treatments? Tell me more about your thoughts” gives the patient a chance to express ideas or feelings without fear of being judged.

3

Changing the subject.

“Let’s not talk about your problems with the insurance company. It’s time for your walk.” Changing the subject when another person is trying to communicate a story is rude and shows a lack of empathy. It blocks further communication, and the sender then withholds important messages or fails to openly express feelings. In some instances, changing the subject serves as a face-saving maneuver. If this happens, reassure the patient that you will return to the concerns: “After your walk let’s talk some more about what’s going on with your insurance company.”

Automatic responses.

“Older adults are always confused.” “Administration doesn’t care about the staff.” Automatic responses are often triggered by stereotypes that are generalized beliefs held about people. Making stereotyped remarks about others reflects poor nursing judgment and threatens nurse-patient or team relationships. A cliché is a stereotyped comment such as “You can’t win them all” that tends to belittle the other person’s feelings and minimize the importance of the person’s message. These automatic phrases communicate that you are not taking concerns seriously or responding thoughtfully. Another kind of automatic response is parroting (i.e., repeating what the other person has said word for word). Parroting is easily overused and is not as effective as paraphrasing. A simple “Oh?” gives you time to think if the other person says something that takes you by surprise.

A nurse who is task oriented automatically makes the task or procedure the entire focus of interaction with patients, missing opportunities to communicate with them as individuals and meet their needs. Task-oriented nurses are often perceived as cold, uncaring, and unapproachable. When students first perform technical skills, it is difficult to integrate therapeutic communication because of the need to focus on the procedure. In time you learn to integrate communication with high-visibility tasks and accomplish a procedure or action more effectively.

False reassurance.

“Don’t worry; everything will be all right.” When a patient is seriously ill or distressed, you may be tempted to offer hope with statements such as “You’ll be fine” or “There’s nothing to worry about.” When a patient is reaching for understanding, false reassurance discourages open communication. Offering reassurance not supported by facts does more harm than good. Although you are trying to be kind, it has the secondary effect of helping you avoid the other person’s distress, and it tends to block conversation and discourage further expression of feelings. To use a more facilitative response you can say “It must be difficult not to know what the surgeon will find. What can I do to help?