Chapter 46: Larynx

1/111

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

112 Terms

What is the mucous membrane covering the lumen of the larynx composed of?

Lumen is lined by a mucous membrane composed of stratified squamous and pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium

Which laryngeal cartilages are paired?

Arytenoid cartilages and attached corniculate processes

Which laryngeal cartilages are unpaired?

Cricoid

Thyroid

Epiglottic

Cricoid Cartilage

Signet ring shaped

Positioned rostral to the first tracheal ring

Connected to the trachea by the cricotracheal membrane

Thyroid Cartilage

Largest of the laryngeal cartilages

Situated rostral to the cricoid cartilage

Arytenoid Cartilages

Positioned on either side of the cricoid cartilage, being conjoined at the cricoarytenoid articulations Articulations are diarthrodial joints that allow the arytenoid cartilages to rotate dorsolaterally during abduction and medially during adduction

Each arytenoid cartilage has a corniculate process forming part of the dorsolateral border of the rima glottidis, a vocal process, and a muscular process that serves as the insertion for the cricoarytenoideus dorsalis muscle

Articulations with the cricoid cartilage allow complete closure of the glottis during swallowing (adduction) and maximal opening (abduction) during exercise

What type of cartilage are the thyroid, crycoid, and arytenoid cartilages made of?

The thyroid, cricoid, and arytenoid cartilages are composed mainly of hyaline cartilage which is subject to ossification with age or trauma Corniculate process is made up of elastic cartilage

Epiglottis

Rests on the dorsal surface of the body of the thyroid cartilage and is held there by the thyroepiglottic ligaments

Made of elastic cartilage

Function of Intrinsic Laryngeal Muscles

Movement of the laryngeal cartilages in relation to each other is achieved by intrinsic laryngeal muscles Contraction of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles produces changes in the cross-sectional area of the rima glottidis first by abducting or adducting the corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages and second by increasing or decreasing tension of the vocal folds

Function of Extrinsic Laryngeal Muscles

Movement or stabilization of the larynx as a whole results from extrinsic laryngeal muscles

Cricoarytenoideus Dorsalis (CAD) Function

Major abductor muscle that widens the laryngeal aperture by abducting the corniculate process of the arytenoid cartilage and mechanically tensing the vocal folds

Cricoarytenoideus Dorsalis (CAD) Innervation

Motor innervation by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve

Thyroarytenoideus (Ventricularis and Vocalis) Function

Adduct the corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages, narrowing the rima glottidis and protecting the lower airway during swallowing

Thyroarytenoideus (Ventricularis and Vocalis) Innervation

Motor innervation by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve

Cricothyroideus Function

Tenses the vocal folds during vocalization

Cricothyroideus Innervation

Receives efferent motor innervation from the external branch of the cranial laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve

Cricoarytenoideus Lateralis Function

Adduct the corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages, narrowing the rima glottidis and protecting the lower airway during swallowing

Cricoarytenoideus Lateralis Innervation

Motor innervation by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve

Arytenoideus Transversus Function

Produces arytenoid cartilage adduction by drawing the medial margins of the arytenoid cartilages toward midline

Adduct the corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages, narrowing the rima glottidis and protecting the lower airway during swallowing

Arytenoideus Transversus Innervation

Motor innervation by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve

Extrinsic Muscles of the Larynx

Thyrohyoideus

Hyoepiglotticus

Cricopharyngeus

Thyropharyngeus

Sternothyroideus

What forms the aryepiglottic folds?

The mucous membrane covering the epiglottic cartilage reflects off the lateral border of the epiglottis and blends with the mucous membrane covering the corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages, forming the aryepiglottic (AE) folds

What forms the vocal folds and laryngeal saccules?

The mucous membrane lines the vocal ligaments and lateral ventricles and forms the vocal folds and the laryngeal saccules

Laryngeal Saccules

Saccules are about 2.5 cm deep with a a capacity of 5-6 mL

Extend between the medial surface of the thyroid cartilage and the ventricularis and vocalis muscles

What innervates the sensory mechanoreceptors in the laryngeal mucosa?

Receive afferent neural supply from the internal branch of the cranial laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve

Arterial Blood Supply of the Larynx

Larynx receives arterial blood supply from the caudal laryngeal artery and branches of the ascending pharyngeal arteries

Venous Drainage of the Larynx

Venous drainage is provided by the caudal laryngeal and ascending pharyngeal veins which flow to the external jugular vein via the thyroid vein

Lymphatic Chains that Serve the Larynx

Include retropharyngeal, cranial, and deep cervical lymph centers

Recurrent Laryngeal Neuropathy (Laryngeal Hemiplegia) Etiology and Incidence

Genetic cause has been proposed

Dupuis et al identified two genome-wide loci in Warmbloods that were a protective halotype in controls

In Throughbreds, Boyko et al found a strong genetic correlation between the withers height and RLN (LCORL/NCAPG locus on ECA3)

Progressive rather than immediate loss of muscle function so varying degrees of abnormal movements of the arytenoid cartilage(s) are frequently observed endoscopically

Prevalence of RLN varies between breeds with the largest population studied being the Thoroughbred where between 2.6 and 8% of horses are reported to be affected

In the heavy draught breeds, a prevalence of up to 35% has been reported

Hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and metabolic acidosis develop more rapidly than in normal horses with the same workload, causing early musculoskeletal fatigue and poor performance

Recurrent laryngeal nerve can be damaged as a result of perivascular jugular vein injection, guttural pouch mycosis, trauma from injuries or surgical procedures of the neck, strangles abscessation of the head and neck, and impingement by neoplasms of the neck or chest

Organophosphate toxicity, plant poisoning, hepatic encephalopathy, lead toxicity, and central nervous system diseases have also been shown to cause laryngeal paralysis

A study of naturally occurring RLN in a mixed-breed population of horses indicated that 94% were of unknown causes in origin (Dixon et al, 2001)

In the 6% of horses with an identifiable cause of RLN, over half were bilaterally affected

Recurrent Laryngeal Neuropathy (Laryngeal Hemiplegia) Diagnosis

Produce an abnormal inspiratory respiratory noise during exercise described as a nonvibratory single-tone whistle

Result of turbulence created by a narrowed rima glottidis as air passes over the affected vocal cord and ventricle which acts as a resonator

On palpation, can feel percutaneous prominence of the muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage or a more easily palpable dorsal aspect of the cricoid cartilage

Havemeyer grading system was validated both by a correlation with histopathological assessment of the CAD muscles and correlation with the standard exercising laryngeal grade

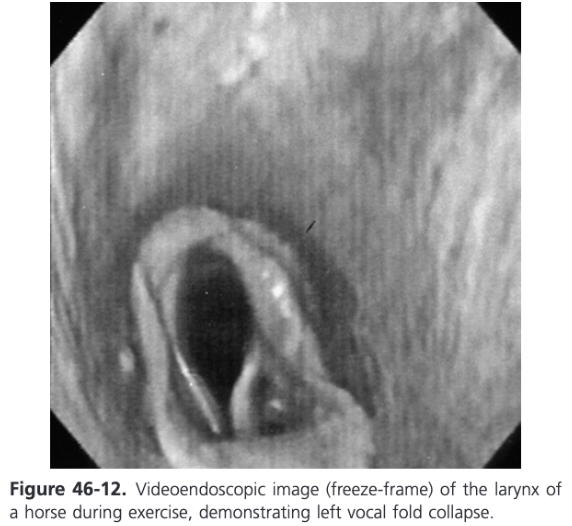

Dynamic endoscopy allows identification of the additional upper airway collapses (comorbid association) that are present in at least 30% of horses with RLN

Complex forms of dynamic collapses are caused by the flow disturbances (changes in kinetic energy, velocity, and increased turbulence) because of the obstruction

When dynamic videoendoscopy is not available, momentary full abduction of the arytenoid cartilages after swallowing is through to be more reliable than nasal occlusion at predicting which horses would demonstrate arytenoid cartilage collapse during treadmill endoscopy at speed

In many horses that cannot achieve full abduction during nasal occlusion, the arytenoids will collapse at speed, but not all will

Horses that showed full symmetrical abduction after swallowing all maintained full abduction at speed

It is well established in horses standing at rest, without clinical evidence of upper respiratory obstruction, that the arytenoid cartilages can be positioned asymmetrically and/or have asynchronous movements

This asymmetry and/or asynchrony may or may not predict failure of arytenoid function during athletic exercise

A study of horses over several years demonstrated that there was no apparent progression from asynchronous arytenoid cartilage movements to complete paralysis (Baker, 1982)

A 2002 study supported the progressive nature of RLN; the long term histories and clinical findings in horses suffering from RLN were examined for evidence of progression of laryngeal asymmetry (Dixon et al, 2002)

15% of cases had evidence of progressive laryngeal dysfunction over a median period of 12 months

Another study highlighted the progressive nature of the disease with successive treadmill examinations over time (Davidson, Martin, and Parente, 2007)

Many foals with marked arytenoid dysfunction can show improved laryngeal function 12 months later so endoscopic findings on a given day may not apply to the future and periodic reexamination is justified

Rapid progression in as little as 6 weeks has been reported

Havemeyer Grade I

All arytenoid cartilage movements are synchronous and symmetrical and full arytenoid carilage abduction can be achieved and maintained

Havemeyer Grade II

Arytenoid cartilage movements are asynchronous and/or larynx is asymmetric at times but full arytenoid cartilage abduction can be achieved and maintained

Havemeyer Grade III A

Transient asynchrony, flutter, or delayed movements are seen

Havemeyer Grade II B

There is asymmetry of the rima glottidis much of the time owing to reduced mobility of the affected arytenoid cartilage and vocal fold, but there are occasions, typically after swallowing or nasal occlusiong, when full symmetrical abduction is achieved and maintained

Havemeyer Grade III

Arytenoid cartilage movement are asynchronous and/or asymmetric. Full arytenoid cartilage abduction cannot be achieved and maintained

Havemeyer Grade III A

There is asymmetry of the rima glottidis much of the time owing to reduced mobility of the affected arytenoid cartilage and vocal fold, but there are occasions, typically after swallowing or nasal occlusion, when full symmetrical abduction is achieved but not maintained

Havemeyer Grade III B

There is obvious arytenoid abductor muscle deficit and arytenoid cartilage symmetry. Full abduction is never achieved

Havemeyer Grade III C

There is marked but not total arytenoid abductor muscle deficit and arytenoid cartilage asymmetry with little arytenoid cartilage movement. Full abduction is never achieved

Havemeyer Grade IV

Complete immobility of the arytenoid cartilage and vocal fold

Recurrent Laryngeal Neuropathy Treatment - General Considerations

Horses that work and race at speed for farther than 800 (0.5 mile) are significantly affected by obstruction of the upper airway

At these speeds and distances, reduction in the laryngeal aperture by 50% increases the work of breathing 16 fold, therefore some form of surgical intervention is warranted

Most common technique is prosthetic laryngoplasty, preferably with a ventriculocordectomy (VC)

Studies in experimentally induced RLN demonstrated that ventriculocordectomy (preferrably bilateral) in grade 4 hemiplegic horses effectively reduced inspiratory noise by 90 days after surgery

Both unilateral and bilateral VC can modestly improve airway flow mechanics and improvement in exercise performance and noise reduction has been identified with ventriculocordectomy

Further advantage of ventriculocordectomy over laryngoplasty is that postoperative complications after laryngoplasty are more prevalent and severe

Can include dysphagia, bilateral nasal discharge of feed, water, and saliva, aspiration pneumonia, chronic coughing, wound infection, prosthesis failure, and chondritis

Many horses still make varying levels of noise during exercise following laryngoplasty so sound production should not be used as an indicator of surgical success in horses where restoration of upper airway flow mechanics is the primary goal of surgery

There is a poor correlation between the sound indices and degree of airway obstruction as measured by inspiratory pressure

A strong positive correlation exists in the degree of arytenoid abduction and sound indices

Greater arytenoid abduction is correlated with more respiratory noise

Partial arytenoidectomy (muscular process left in situ) is chosen to treat laryngeal hemiplegia when there is a congenital malformation of cartilages of when the laryngoplasty technique has failed because of fractures in the cartilage

Has been shown to improve airway mechanics to a level similar to laryngoplasty and Thoroughbred horses have returned to successful careers

Nerve muscle pedicle graft is suitable for horses of all breeds and ages but is most commonly used in young horses, where return to athletic function is not expected before 4 months after surgery

Successful reinnervation is possible in grade 4 RLN, horses with grade 3 arytenoid cartilage movements are thought to be better candidates because less muscle atrophy is present

Nerve-pedicle technique is being replaced by nerve implantation technique

Horses fasted 8-12 hours before laryngeal surgery

Recurrent Laryngeal Neuropathy Treatment Options

Surgical treatments include prosthetic laryngoplasty, ventriculectomy (sacculectomy), ventriculocordectomy, reinnervation of the CAD muscle, and occasionally arytenoidectomy

Traditional Laryngoplasty

Lateral recumbency with head and neck extended

Videoendoscope secured transnasally

10-12 cm incision made immediately ventral and parallel to the linguofacial vein, extending caudally from a point 4 cm cranial to the ramus of the mandible

Linguofacial vein dissected from the lateral margin of the omohyoideus muscle

Elevate the linguofacial vein at the middle of the incision to expose the cleavage plane between the cricopharyngeus and cricothyroideus muscles which is digitally opened and enlarged

Caudal border of the cricoid cartilage is bluntly freed from connective tissue

Exposure of the dorsal aspect of the cricoid cartilage is improved by lateral traction of the cricoid cartilage using a towel clamp held by the surgeon

Muscular process exposed by sharply separating the cricopharyngeus and thyropharyngeus muscles along the junction of their aponeurosis

Elevate the wide isthmus of the esophagus and its adventitia

Alternatively, a plane of dissection can be created off the back edge of the cricopharyngeus muscle under the vascular plexus that lies over the CAD muscle

Rostral retraction of the cricopharyngeus muscle often exposes almost the entire CAD muscle and musclar process without interference from the cricopharyngeus muscle

Rotating the larynx laterally by placing a spay hook on the thyroid lamina improves the exposure of the muscular process

Suture materials that have been used include braided polyester with (#5 Ti-Cron) or without silicone coating, 6 mm surgical stainless-steel wire, braided lycra, Polyblend suture, Polyblend tape, and nylon

Prosthetic suture first placed through the cricoid cartilage

Use of two sutures is common and has been shown in vitro to be mechanically superior to one and results in a larger cross-sectional area of the rima glottidis

Different needles have been used: swaged on, reverse cutting needle on the Ti-Cron, #3 Martin uterine reverse cutting needle

Using the left index finger as a guide, the needle is "walked off" the caudal edge of the cricoid cartilage 2-3 mm lateral to the dorsal midline until the point slips under the cartilage (there is a palpable notch in the cricoid cartilage at this site) and the needle is advanced in a cranial direction will avoiding penetration into the lumen of the larynx and then the needle is rotated to penetrate the cricoid cartilage 2-3 cm cranial to its caudal border and 1 cm lateral to the dorsal ridge

Alternatively, both strands of a suture can be passed through a titanium button prior to placing the suture through the cricoid cartilage

Can consistently be placed at a planned distance from the sagittal ridge of the cricoid cartilage through a thicker portion of cricoid cartilage and result in a constant angle of tension in relation to the muscular process

If this technique is used, the needle should be advanced no more than 1 cm from the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage to allow proper "docking" of the button to the ventral aspect of the cricoid cartilage

When the needle has been drawn through the cartilage and out of the incision, the needle is cut off and the suture ends are tagged with a small hemostat

Second suture is usually placed 10 mm lateral to the first using the same technique

If the cricopharyngeus muscle has not been retracted forward, a Glover forceps is passed under the cranial aspect of the cricopharyngeus muscle to bring both ends of the first and second suture cranial toward the muscular process of the cricoid cartilage

Placement of the suture through the muscular process can be achieved by a variety of techniques

Heavy needle drivers and a reverse cutting #6 Mayo needle or #6 Martin uterine needle

Use of 3 mm bone trocar to create a tunnel for the suture has been reported to reduce fissure formation and risk of cartilage failure from suture pullout

12 to 16 gauge Jamshidi needle can also be used

Prosthesis can be placed through a loop of #1 stainless-steel wire that is then passed through the tunnel in the muscular process

Before needle placement, the cricoarytenoideus articulation should be opened and curetted or rasped to facilitate early ankyloses of the joint

Some transect the tendon of insertion of the CAD muscle onto the muscular process to access the joint while others use a curbed Crile hemostatic forceps to create access for a curette or Miller rasp

Goal of this step is to reduce the loss of abduction frequently observed in the early postoperative period

To enhance this further injection of PMMA has been advocated as a better method of joint ankylosis

Removal of the attachment of the cricoarytenoideus tendon has been hypothesized to reduce the opportunity for cycling of the prosthesis in horses with grade 3 RLN which is thought to increase the early postoperative loss of arytenoid abduction

Typically the needle is passed through the muscular process from the caudomedial aspect to the craniolateral aspect

Some prefer to pass the hypodermic or Jamshidi needle from caudolateral to craniomedial, parallel to the cricoarytenoid joint

Needle can also be placed in a caudal to cranial (sagittal) direction

After removal of the needle, tension is placed on the cranial and caudal ends of the suture to remove any slack, ensuring the prosthesis is tight against the larynx

If a trocar is being used, both sutures can pass through a single tunnel; otherwise the second suture is placed approximately 5-10 mm more cranial in the muscular process

Engaging the spine of the muscular process rather than its tip is essential to achieve maximal biomechanical advantage and to avoid early pull-through of the prosthesis

The trailing ends of the prosthetic sutures can be drawn under the cricopharyngeus muscle if necessary with a hemostat and the sutures are tied

When using suture as the prosthesis, leaving the cut ends 1.5-2 cm long can allow the knot to be undone and retied if repeat laryngoplasty is performed within the first week of the original surgery

After sutures have been tied, the thyropharyngeus and cricopharyngeus muscles are reapposed with simple continuous suture

Dixon Grade?

1

Dixon Grade?

2

Dixon Grade?

3

Dixon Grade?

4

Dixon Grade?

5

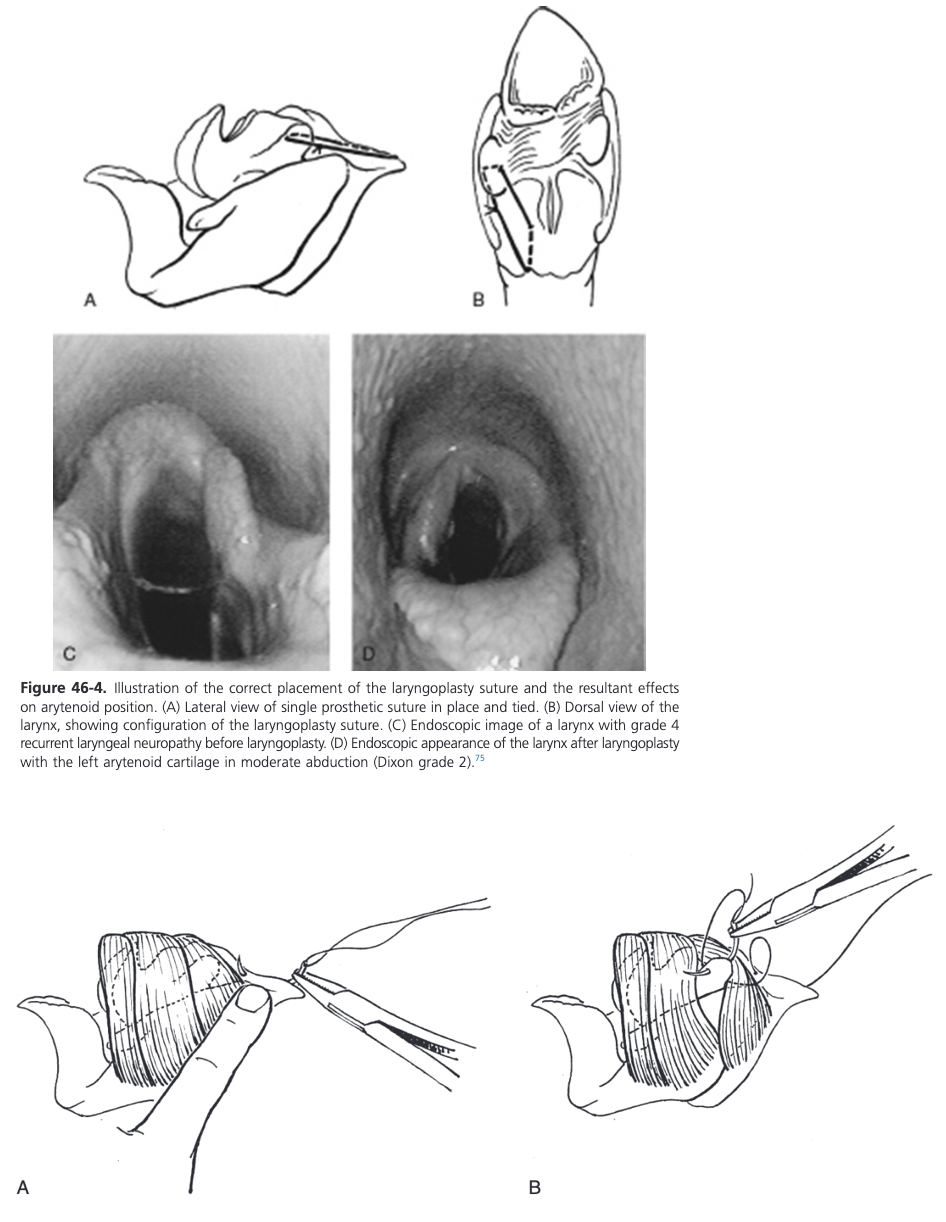

Abduction Obtained During Laryngoplasty

Abduction obtained during laryngoplasty has been classified into five grade by Dixon et al

Grade 1 - maximal abduction

Not necessary to achieve success and may be associated with increased morbidity (tracheal aspiration)

Grade 2 - approximately 88% of maximal rima glottidis cross-sectional area

Sufficient to allow adequate airflow

As a general guide, when the curvature of the corniculate process comes into contact with the wall of the pharynx, the ideal degree of abduction has bee achieved

Standing Laryngoplasty Advantages

Two main advantages over traditional technique

Avoids the need for and complications associated with general anesthesia

Allows a more accurate assessment of the degree of arytenoid abduction achieved during surgery

Subjectively less force is needed on the sutures to create abduction, presumably because the larynx is not compressed by right side recumbency and internally fixed by an endotracheal tube

Standing Laryngoplasty

Almost identical to traditional technique except for the following points

Protective head gear is placed on the horse to prevent debris from contaminating the surgery site, an ipsilateral eye cup is applied and ear plugs are used, a head band without a strap in the throat latch is placed over the head gear

Endoscope is placed in the right nostril and local anesthetic applied to prevent swallowing. After the endoscope is secured to the nose band, the light on the endoscope is turned off until sutures are passed into the cricoid cartilage

Anesthesia is obtained by standard CRI and infiltration of local anesthetic at the ventral aspect of the linguofacial vein and surrounding C2 nerve branches

Prior to infiltration of local anesthetic, skin staples are placed on the ventral border of the linguofacial vein as a guide to position the skin incision immediately ventral to the staple line because the contour of the vein is lost by infiltration of local anesthesia

Head position is less extended than traditional laryngoplasty

Variations of Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Technical variations of the laryngoplasty include the use of one prosthetic suture only or using a crochet- style hook rather than a loop of wire to pull the leading edge of the prosthesis through the muscular process

A technique to refine the tension applied to create arytenoid abduction involves using a tension and crimping device to adjust and secure the prosthetic suture (Securos Equine Tie-Back System)

In an invitro study, an increase in holding strength of a double loop fixation of the suture through the muscular process was shown (Kelly et al, 2008)

The use of a titanium corkscrew as suture anchor in the muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage and a stress-reducing washer at the cricoid showed significantly higher forces to failure compared with the original laryngoplasty technique but no significant in vivo information is present to validate its use

Placement of one suture dorsally and one about 10 mm laterally in the cricoid cartilage is important for achieving adequate abduction

Placement of the suture too far laterally results in inadequate abduction

The ideal position is between 10 and 30 degrees from zero (zero degrees is defined as a line through the muscular process of the left arytenoid cartilage and parallel to the wing of the thyroid cartilage when viewed dorsally)

Intraoperative Complications of Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Hemorrhage from deep in the surgical site, needle breakage, perforation of the laryngeal mucosa, and prosthetic suture "cut-through" of either the cricoid cartilage or muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage

Significant hemorrhage can arise from the plexus of laryngeal vessels that are inadvertently punctured as the needle is passed through the cricoid cartilage and vascular blood supply of the CAD muscle

If attempts to find a broken needle are unsuccessful because the needle is embedded in cartilage or buried in the adjacent soft tissues and has not penetrated the lumen of the larynx, the needle is left because extensive dissection increases the risk of postoperative dysphagia

Damage to the muscular process from suture pullout can necessitate placing the new suture at 90 degrees to the original and farther down the spine of the muscular process to minimize the opportunity of a repeat complication

Perforation of the laryngeal mucosa is most likely to occur when curetting the cricoarytenoid joint or while placing the needle under the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage

Placement of the sutures in the muscular process is the most likely time when the esophagus can be penetrated

Complications in the First 2 Weeks Post Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Complications in the first 2 weeks postoperatively include seroma, wound infection, wound dehiscence, dysphagia, coughing (often, but not always) associated with eating and mild to excessive loss of abduction

Coughing and Dysphagia Post Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Following laryngoplasty, many horses experience some degree of coughing and dysphagia

Dysphagia can be related to excessive and prolonged retraction or surgical damage to the cricopharyngeus and thyropharyngeus muscles because these muscles comprise the cranial esophageal sphincter

Sutures inadvertently placed through the adventitia of the esophagus can also result in chronic coughing or odd swallowing behavior

Initially odynophagia, may result in reluctance to swallow

In the first few days after surgery, saliva, water, and food material may enter the trachea when the horse eats and drinks, resulting in significant coughing

Intensity of coughing often reduces over 7-10 days but many horses have some degree of residual coughing when eating

Incidence of coughing in the immediate postoperative period has been reported to be as high as 43%

Persistent coughing is most likely the result of continued tracheal contamination with saliva, water, or food material

Dysphagia immediately after surgery may be caused by temporary pharyngeal dysfunction, which occurs simple from surgical manipulation

Other factors that may result in more significant dysphagia include (1) overabduction, (2) failure of the contralateral arytenoid and vocal fold to compensate to seal the larynx, (3) esophageal reflux from fibrosis of the cranial esophagus which may have multiple causes: modification of the normal anatomy of the vestibulum esophagi when passing its adventitia with the sutures or surgical damage or fibrosis interfering with the cranial esophageal sphincter and (4) excessive fibrosis of the hemilarynx (deviating the larynx to the operated side) such that the appropriate covering of the rima glottidis by the epiglottis during swallowing does not occur properly

Identification of the exact cause can be made using an endoscopic swallowing test or barium study

Removal of the prosthesis may resolve the contamination problem and even the chronic cough in some horses, but other treatments such as performing a laryngeal tie-forward or simply allowing more time to pass may permit this problem to resolve

Mild upper airway contamination increases the risk of postlaryngoplasty DDSP while moderate and severe contamination increases the risk of secondary septic pulmonary disease

Chronic coughing has been reported in up to 14% of horses more than 6 months after surgery with many of them having concurrent pulmonary disease

Postoperative Complications Following Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Excessive or failed abduction may necessitate a revision laryngoplasty

If the prosthetic suture becomes infected, antimicrobial therapy may resolve the infection and removal of the prosthetic suture is often not necessary and should be delayed for about 4 months because early removal will result in failure of arytenoid cartilage abduction

Prosthetic suture pullout resulting in failure of laryngoplasty has been proposed to be more likely in yearlings or 2 year old horses but experimentally there is significant effect of age on the in vitro cartilage retention of the prosthesis

Most commonly suture pullout occurs at the muscular process

Loss of abduction is a well-recognized phenomenon that occurs during the first 30 days after surgery

Partial muscular process cartilage failure suggested as the likely cause

Suture cutting through or sliding laterally on the cricoid cartilage is equally as likely

One retrospective clinical study revealed a much higher rate of successful outcome after prosthetic laryngoplasty in horses that were 2 years old or younger than in horses 3 years old or older (Russell and Sloane, 1994)

No hard evidence to exclude young horses (<2 years old) from laryngoplasty treatment and they are at no greater risk for laryngoplasty failure than older horses

Chronic Complications of Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Chronic complications include persistent coughing, chronic airway contamination with feed, saliva, and water, chronic tracheitis and bronchitis, lung abscess formation, pneumonia, chondritis with formation of a luminal suture sinus, isolated inflammation and granuloma formation on the corniculate process of the arytenoid cartilage, perilaryngeal abscess formation, suture pullout, progressive loss of abduction, and persistent nasal discharge of feed, water, and saliva

Revision Laryngoplasty

Revision laryngoplasty may be necessary for loss of abduction or when overabduction results in persistent coughing and aspiration of feed

Requirement for revision surgery has been reported to be as high as 10% for loss of abduction and up to 7% for management of overabduction

Easiest when performed early in all cases and should be the preference in all cases where a standing revision laryngoplasty is planned

The timing should be considered carefully in the first 10 days after surgery if performed under general anesthesia

Performing revision laryngoplasty in the standing horse improves vision, exposure, and assessment of revised arytenoid abduction

Goal of reoperation in the early postoperative period (first 14 days) is to tighten or loosen the prosthesis by twisting if wire was used or to extract the original laryngoplasty sutures and replace them with another suture or sutures that achieves more ideal arytenoid cartilage abduction

Very rarely, one can retie the suture if there has not been pullout from either cartilage

Under general anesthesia, if the cartilage is elevated away from the endotracheal tube it is likely that the goal of improving abduction has been achieved, if not, it is likely that the reoperation attempt will fail

Can decide whether to place another suture to try to achieve greater abduction or whether to advise of the need for arytenoidectomy

If overabduction after laryngoplasty produces excessive and persistent airway contamination, a new prosthesis can be placed that fixes the arytenoid cartilage with less abduction than the original suture if the reoperation is performed within 2 weeks of the initial surgery

When reoperation takes place more than 120 days after the first surgery, removal of the sutures without replacement may be all that is necessary

Prognosis Following Prosthetic Laryngoplasty

Reported success rates have ranged from 5-100% it is realistic to expect that between 70 and 80% of racehorses treated with laryngoplasty will have improved racing performance after surgery

Outcome will be more successful in horses that are not intended to race after surgery

In a retrospective performance analysis after prosthetic laryngoplasty, the degree of arytenoid abduction did not correlate with a successful surgical outcome

An in vitro analysis has ascertained that an airway with an opening of 88% of the maximal rima glottidis cross-section (Dixon grade 2) allows adequate airflow for exercise (Rakesh et al, 2008)

Clinically, even in horses with Dixon grade 3 abduction following laryngoplasty, satisfactory performance is achievable

Ventriculectomy (Sacculectomy, Hobday Procedure)

Ventriculectomy (VC) (unilateral or bilateral) refers to the removal of the muscoal lining of the laryngeal ventricle located caudal to the vocal fold

Usually performed to eliminate noise and has minimal beneficial effects on performance

In draft-type horses, complication rates of traditional laryngoplasty (e.g. failure, myopathy, neuropathy, anesthetic problems, coughing) can be as high as 25%, therefore, bilateral VC, either through a laryngotomy or via transendoscopic laser excision in the standing horse is an acceptable alternative when standing laryngoplasty is not available

Transendoscopic laser VC is more commonly performed, but the procedure can be complete through a laryngotomy under GA, frequently at the conclusion of a laryngoplasty

Ventriculectomy Under General Anesthesia Through a Laryngotomy

If it is performed under GA and after the laryngotomy has been completed, the endotracheal tube can be removed or left in place

Use of a smaller endotracheal tube (<20 FR) often negates the need for tube removal

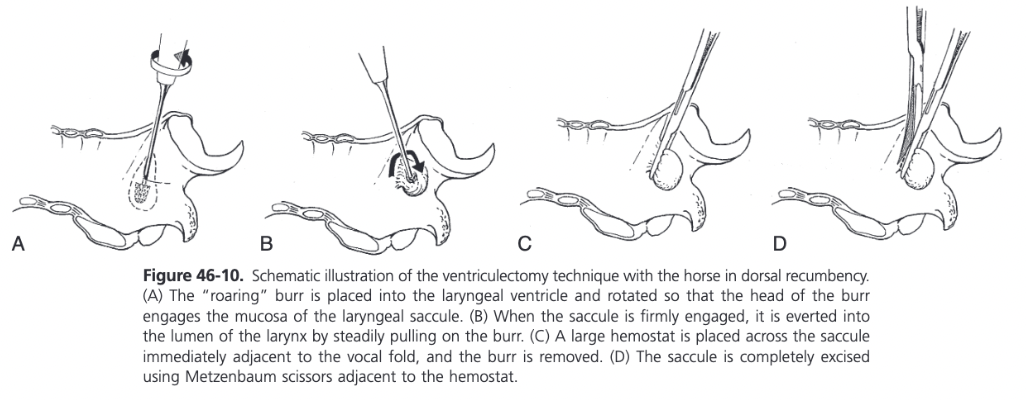

A burr (e.g. Williams burr) is introduced into the ventricle to its maximum depth and twisted to engage the mucosa in the projections on the burr

Burr is subsequently withdrawn slowly from the ventricle, everting the attached saccule

A large forceps (Carmalt, curved Crile) is placed across the everted saccule between the head of the burr and the vocal fold

With traction on the clamp, a second forceps is placed behind it

By applying digital pressure on the opening of the ventricle, the entire saccule is everted and subsequently excised with Metzenbaum scissors

The same procedure is repeated on the other side if bilateral VC is indicated

Ventriculocordectomy

Removal of the mucosal lining of the laryngeal ventricle as well as the removal of a crescent-shaped wedge of tissue from the leading edge of the vocal fold

Had replaced VC as first line of treatment because VC yields little improvement in reducing vocal cord collapse associated with recurrent laryngeal neuropathy

Improved airway mechanics around 30% in horses with experimentally created laryngeal hemiplegia

Evidence that ventriculocordectomy can allow improved athletic performance in a subset of horses with RLN

Suitable candidates for ventriculocordectomy include:

Sport horses with grade 4 laryngeal movements where the primary complaint is respiratory noise and exercise intolerance is not a feature

Racehorses with grade 3 laryngeal movements that do not experience complete arytenoid collapse during high-speed exercise but do experience vocal fold collapse identified with exercising videoendoscopy

Racehorses that have had a laryngoplasty and still experience vocal fold collapse during high-speed exercise

Bilateral ventriculocordectomy, especially when associated with laryngoplasty, might increase the risk of coughing and dysphagia compared to unilateral (left) ventriculocordectomy

Preserving some tissue at the most ventral part between the vocal folds may reduce the risk of cicatrix formation (webbing)

Transendoscopic laser-assisted ventriculocordectomy can be performed in the standing sedated horse

Commonly a diode laser is used and surgery is performed via manipulation of the vocal fold by Equine laryngeal forceps of a modified Blatternburg burr

Ventriculocordectomy via Laryngotomy

Can be performed via laryngotomy

Following the ventriculectomy as described earlier, a 2 cm long and 2-3 mm wide crescent-shaped wedge of tissue is removed from the leading edge of the vocal fold

If the procedure is performed standing, the incisions are left to heal without suturing

If the horse is under general anesthesia, using a continuous suture pattern of 2-0 polydioxanone, the outside (lateral edge of the vocal fold) and inside (medial) border of the ventricle are apposed

Suturing limits hemorrhage at the time of surgery while lessening cicatrix formation and redundant tissue folds during healing of the surgery site, leaving a smooth surface over the ventral half of the rima glottidis

Laryngotomy

10-15 cm incision made along ventral midline from just rostral to the palpable keel of the thyroid cartilage extending caudad to just beyond the cricoid cartilage

Sternothyrohyoideus muscles are separated along the full length of the incision using Metzenbaum or Mayo scissors

Cricothyroid membrane and underlying mucosa are incised along midline with a #10 or #11 scalpel blade

Membrane is incised from the cricoid to the cranial limit of the thyroid cartilage V

For VC and most laryngeal lumen procedures, incising the cricothyroid membrane will provide adequate exposure; however in some cases, (arytenoidectomy), transecting the cricoid cartilage and partially splitting the keel of the thyroid cartilage is acceptable to achieve better surgical exposure

Two options for closure: leave the entire incision open or close the cricothyroid membrane with simple interrupted absorbable sutures

Complete closure of the laryngotomy has traditionally not been recommended because up to 52% of horses have been reported to have complications associated with the closure including subcutaneous emphysema and incisional infection

Postoperative Management Following Laryngotomy

Under normal circumstances, laryngotomy incisions heal within 21 days

Complications Following Laryngotomy

Rare

Excessive retraction during surgery can cause bruising and trauma to the sternothyrohyoideus muscle followed by necrosis and local infection several days later, resulting in malodorous and excessive wound discharge

Resection of necrotic tissue results in a rapid resolution

Clostridial infection at the laryngotomy site can occur within a 24 hour period after surgery producing tremendous swelling of the head and neck and resulting in a massive tissue slough with potentially fatal outcome

If occurs treatment with penicillin indicated

Occasionally excessive granulation tissue forms in the ventricles after sacculectomy but usually resolves with time and the application of antiinflammatory sprays

Laryngeal Reinnervation

Any horse with RLN is a candidate but younger horses and those with grade 3 laryngeal movements are the ideal candidates for this procedure

Most common technique involves implanting a nerve-muscle pedicle (NMP) graft into the affected CAD muscle

Omohyoideus muscle is innervated by a nerve formed by the first and second cranial nerve branches (C1/C2 nerve)

Junction of branches of this nerve to a small (5mm) block of muscle are used from the NMP graft because the omohyoideus muscle is an accessory muscle of respiration (active on inspiration) and the C1/C2 nerve is in close proximity to the larynx

The recently described nerve-implantation technique is replacing the nerve-muscle pedicle procedure

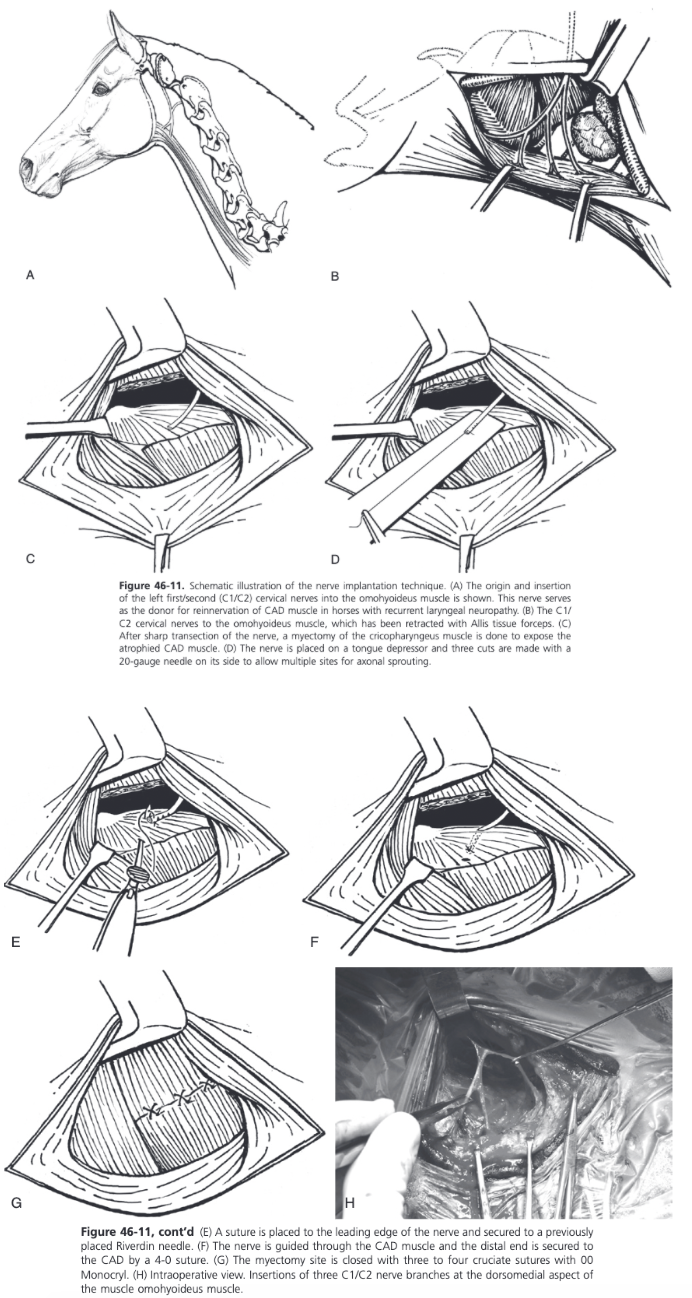

Nerve-Implantation Technique for Laryngeal Reinnervation

Surgical instruments should include very small atraumatic thumb forceps, a spay hook, a nerve holding thumb forceps, and small blunt Weitlaner self-retaining retractors in addition to the instruments used for laryngeal surgery

For left RLN, right lateral recumbency and head and neck positioned as for laryngoplasty

12 cm linear incision made along the ventral border of the linguofacial vein, which is carefully separated from the omohyoideus muscle

First cervical nerve usually lies under the linguofacial vein at the caudal half of the incision

Ventral branch of the first cervical nerve emerges through the alar foramen of the atlas, and after joining with branches of the C2 nerve, descends over the caudal aspect of the larynx before dividing into two or three branches as it enters the omohyoideus muscle

Main body of C1/C2 nerve is identified with the help of a single pulse nerve stimulator (1 mA)

Stimulation of a branch of C1/C2 results in synchronized twitching of the omohyoideus muscle

Insertions of the C1/C2 nerve branches can be found in the dorsomedial aspect of the muscle belly

Meticulous dissection to expose the fine branches of the nerve as they enter the omohyoideus muscle

Exposure is improved by ventral retraction of the omohyoideus muscle using two Allis tissue forceps

Middle branch of the nerve often divides into smaller branches and can be traced to a point of muscle entry: one or two branches are identified, gently dissected proximally so they can be implanted without tension in the CAD muscle

Anastomoses with other nerves in the atlantal fossa are preserved

Main branch which, when stimulated, produces the strongest contraction of the OH is selected

This branch is gently elevated using a spay hook or a nerve holding thumb forceps and is freed from its fascial attachments on the lateral aspect of the larynx

The distal end of the nerve is cut with a fresh 15 blade

One additional smaller branch is usually freed and cut similarly

End of the nerve is wrapped in a saline soaked sponge

Thyropharyngeus and cricopharyngeus muscles are bluntly separated

Rostral two-thirds of the cricopharyngeus muscle are clamped using long Satinsky forceps and sectioned transversally to expose the CAD

A 4-0 suture nylon is placed in the distal end of the nerve to allow implantation of the nerve

To facilitate multiple sprouting areas of the nerve, it is placed on a tongue depressor and three small cuts are made along the distal 15 mm of the nerve with the bevel of a 20 gauge needle

Larynx is rotated laterally by placing a spay hook on the thyroid lamina and a Reverdin needle is passed from lateral to medial in the midbody of the CAD

The suture is secured to the needle

The nerve is implanted within the CAD tunnel by retraction of the needle

Suture is cut and another 4.0 suture is placed in the epineurium of the distal end of the nerve

Suture is then guided back inside the lateral end of the tunnel and sutured to the lateral belly of the CAD muscle, approximately 5 mm medial to the exit point of the nerve

The exit point of the nerve medially is retracted by a nerve hook so that the nerve and its three cut ends are located within the belly of the CAD muscle

Alternatively, the small transverse cuts at the distal part of the nerve can be performed after tunneling the nerve through the CAD, just before suturing

Any excess nerve branch is implanted directly in a small slit in the lateral muscle belly of the CAD as described

Partial myotomy of the cricopharyngeus is then closed with three simple cruciate patterns

Postoperative Care Following Laryngeal Reinnervation

Horse confined to a stall for 2-3 weeks then paddock turnout for 14 weeks, then put into training 16 weeks after surgery

Earliest time to see clinical evidence of reinnervation is around 12 weeks following surgery

This can be tested by direct stimulation of the C1 nerve under endoscopic control

When the horse is returned to exercise, episodes of fast exercise should be introduced as early and as frequently as possible

After 6 weeks of training the horse should have an endoscopic assessment of the larynx

At rest the left arytenoid cartilage usually appears as it did before surgery

Under ultrasonographic control, a 26 gauge bipolar nerve stimulation needle is inserted in the ipsilateral foramen of the Atlas

Stimulation is used while under endoscopic control

Repeatable twitching of the left arytenoid, synchronous with the stimulation frequency confirms the reinnervation

Other less reliable techniques are the observation of a spontaneous flicker or single abduction of the left arynteoid cartilage

This reflex can sometimes be induced by pulling back rapidly with a finger or with the bit, resulting in sudden pressure on the commissure of the horse's lips

Sudden abduction of the left arytenoid cartilage occurs if reinnervation has been successful

Reflex can be stimulated from the left or right side of the head

When reinnervation has been identified, the recommendation is to continue training toward a return to racing

If there is no evidence of movement at the first revist, the horse is turned out again for another 8 weeks, receives 6 weeks of training, and is rexamined

Horses can take up to 12 months to show evidence of successful reinnervation

If there is no arytenoid abduction as a result of reinnervation 9 months after surgery, the chance of future improvement is small

Reinnervation probably occurs in nearly all patients by 4-5 months

Quality of successful reinnervation is best assessed with dynamic upper airway endoscopy

In treadmill studies, it was found that horses with visible movement of the left arytenoid cartilage at rest maintained arytenoid abduction during vigorous exercise but often not maximal

Complications Following Laryngeal Reinnervation

Most common complication is seroma formation 3-5 days after surgery

Horses with postoperative incisional infection have gone on to have successful reinnervation so it seems that this complication does not necessarily compromise success of the laryngeal reinnervation graft

Prognosis Following Laryngeal Reinnervation

Can take between 6 and 12 months depending on the amount of CAD muscle atrophy

Horses with grade 3 RLN will respond sooner (in 4-6 months) than those that have grade 4 RLN

Horses best suited for the transplantation technique are those whose immediate return to performance is not necessary such as yearling or early 2 year old racehorses and pleasure horses

Horses that have had previous laryngoplasty are not candidates for this surgery because of disruption of the first cervical nerve during that surgery or trauma and resultant fibrosis of the CAD muscle

Group of racing Thoroughbreds followed to the end of their racing careers

Unraced horses had an average time of 13.5 months from surgery to their first race with a range of 7-28 months

51/71 horses unraced prior to surgery started a race and 63% won at least one race

On average these horses had 14.6 starts

In the raced group, the average time to the first race was 8 moths

60% of horses won at least one start and 52% of horses won more prize money in total after surgery

Only 39% earned more money per start after surgery and only 45% had an improved performance ranking

Based on follow-up endoscopy, 80% were considered to have a successful reinnervation because of the presence of flickering abductory movements of the arytenoid cartilage observed at rest

In a recent study on a smaller group of 17 client owned sport and racehorses using a nerve-implantation technique, successful reinnervation was achieved in 11/12 horses tested using C1 nerves stimulation (Rossignol et al, 2018)

13/14 that underwent a preoperative and postoperative exercising endoscopy improved or maintained their dynamic RLN grade

These horses did not show any instability of the left arytenoid during the 12 month follow up period, despite an intermediate degree of arytenoid abduction

14/17 horses had complete resolution of reported respiratory noise and all could perform successfully at their intended use

Success rate is comparable to prosthetic laryngoplasty

Vocal Fold Collapse

Can only be observed during high-speed exercise using videoendoscopy

Stabilization of the vocal cord occurs when the cricothyroid muscle, which is innervated by a branch of the cranial laryngeal nerve, contracts

Occasionally, medial deviation of the fold occurs in horses with resting laryngeal grade 3 RLN

Observed after laryngoplasty when only a concurrent VC has been performed

Treatment is bilateral ventriculocordectomy

Bilateral Laryngeal Paralysis

Associated with oragnophosphate toxicity, central nervous system diseases, such as EPM, hepatic dysfunction, hepatic encephalopathy, and lead toxicity and has been seen temporarily following general anesthesia

Also has been observed in horses with Australian stringhalt

Horses with bilateral laryngeal paralysis do not tolerate even minimal exercise or stress and make a loud inspiratory noise when in distress, even at rest

Both arytenoid cartilages are affected but the degree of paresis may differ between sides

Horses with bilateral laryngeal paralysis that is associated with EPM can show improved laryngeal function after appropriate medical treatment

Unilateral laryngoplasty can be performed on the more severely affected side to salvage the horse for nonperformance activities

Airway contamination with feed, water, and saliva, can be severe because adductor function on the contralateral side may be compromised so some estimate of adductor function should be made before unilateral laryngoplasty is undertaken

Bilateral laryngoplasty is not recommended so a permanent tracheostomy should be considered

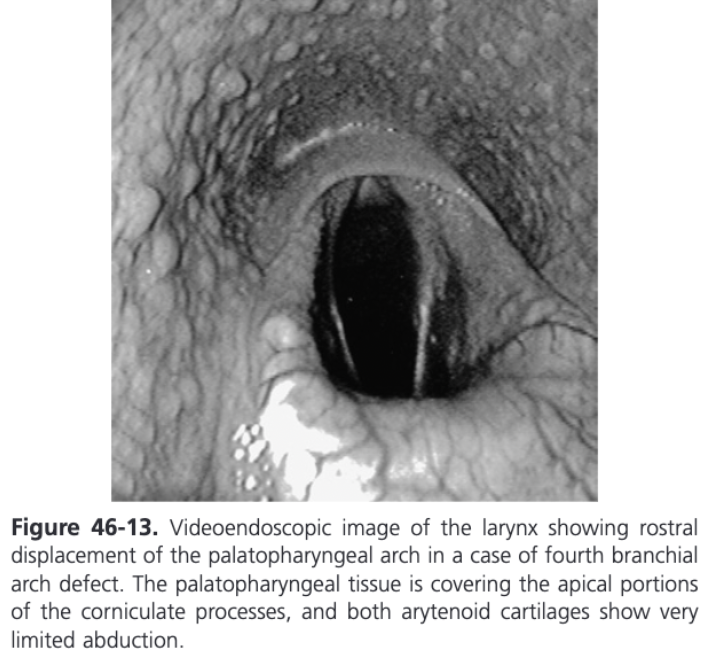

Cricopharyngeal-Laryngeal Dysplasia (Fourth Branchial Arch Defects)

In the horse, the lateral wings of the thyroid cartilage, cricoarytenoid articulation, the cricoid cartilage, and the cricothyroideus, thyropharyngeus, and cricopharyngeus muscles are all derived from the embryological fourth branchial arch

Abnormal development of one or more of these structures, unilaterally or bilaterally produces a syndrome defined as fourth branchial arch defects (4-BAD syndrome)

Incidence of 0.02%

Most common presentation is exercise induced respiratory noise secondary to dynamic collapse of soft tissues or cartilaginous laryngeal tissues

CAD muscle is normal but the abnormal cartilage skeleton renders CAD contraction ineffective

Right side of the larynx is most frequently affected and bilateral involvement is more common than left-sided involvement alone

Horses with a severe deformity can show respiratory obstruction associated with collapse of the palatopharyngeal arch, failure of arytenoid abduction, vocal cord collapse, DDSP, and all of the above

Dysphagia and repeated colic because of a deformity and dysfunction of the cranial esophageal sphincter muscles (cricopharyngeus and thyropharyngeus) can be observed

Can be detected on laryngeal palpation

Most horses have an obviously palpable deficit of the thyroid wing on one or both sides or an easily palpated gap between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages because of the absence or atrophy of the cricothyroid muscle

Rostral displacement of the palatopharyngeal arch is commonly used to report the abnormal endoscopic findings when the caudal margin of the ostium intrapharyngeum is displaced rostral to the dorsal tips of the corniculate processes of the arytenoid cartilages

If laryngeal endoscopy indicates right-sided RLN, 4-BAD should be on the top of the differential diagnosis list until proved otherwise

Radiography can support a diagnosis of 4-BAD

Air in the upper esophagus will be continuous with air in the pharynx as a result of dysfunction of the cranial esophageal sphincter

The palatopharyngeal arch may also be seen as a soft tissue mass rostral to the corniculate process

Dynamic endoscopy is recommended prior to instituting treatment

No standardized surgical solution for horses with 4-BAD defects and the treatment should be tailored to the patient

Partial arytenoidectomy is the treatment recommended when obstruction by the arytneoid cartilage is noted

Some horses can respond to laryngoplasty if the thyroid lamina is removed and the cricoid cartilage is not involved in the deformity but the outcome of the surgery is unpredictable

Some horses can perform athletically, but usually not to their full potential

Tie-forward ahs been suggested when DDSP is observed

Laser resection of the palatopharyngeal arch is useful when dynamic collapse of the palatopharyngeal arch is identified with dynamic videoendoscopy without significant collapse of the arytenoid cartilages

Right-Sided Laryngeal Hemiplegia

Rare

Idiopathic form of RLN does not usually affect the right CAD muscle to a level resulting in marked paresis or paralysis

In a series of horses treated for right-sided laryngeal hemiplegia, 7/11 Thoroughbreds had congenital malformation of the laryngeal cartilages resulting in a high percentage of failure of a laryngoplasty

Partial arytenoidectomy may be selected as a treatment, but dynamic videoendoscopy is recommended prior to advising surgery

Spontaneous recovery from right-sided laryngeal hemiplegia has been reported, but it would not be an expected outcome in a 1-2 year old Thoroughbred

Poor prognosis for athletic function should be given

Collapse of the Apex of the Corniculate Process

Reported as a finding on high-speed treadmill videoendoscopy and during resting endoscopy after swallowing or nasal occlusion

Postmortem studies have found a significant widening of the transverse arytenoid ligament that normally keeps the tips of the corniculate cartilages in close apposition

Currently no reported treatment available

Medial Deviation of the Aryepiglottic Folds - Diagnosis

Occurs during maximal exertion and causes dynamic partial upper respiratory tract obstruction

Contralateral aryepiglottic collapse is seen in horses with laryngeal hemiplegia

Mild to moderate AE fold collapse can also be seen in horses with DDSP

Diagnosis requires videoendoscopic examination during high-speed exercise

In a study of affected horses 80% were racing Thoroughbreds, 13% were racing Standardbreds, and 7% were racing Arabians

Abnormal respiratory noise and exercise intolerance were the most common clinical manifestations

Condition is almost always bilateral, but unilateral involvement if present, has been reported to be right-sided

Medial Deviation of the Aryepiglottic Folds - Treatment

Transendoscopic laser surgery using a Nd:YAG or diode laser with a 600 um fiber in contact fashion can be performed with the horse standing or anesthetized

The lateral part of the aryepiglottic fold that is collapsing into the airway during exercise is grasped and placed under tension with an Equine laryngeal forceps, and an approximately 2 cm wide triangle is excised transendoscopically

Don't remove the medial part of the fold connected to the ventral part of the corniculate process

Can also be performed through a laryngotomy in the anesthetized horse

Allis tissue forceps can be used to grasp the tissue, and Metzenbaum scissors are used to rim the redundant tissue

No suturing is necessary

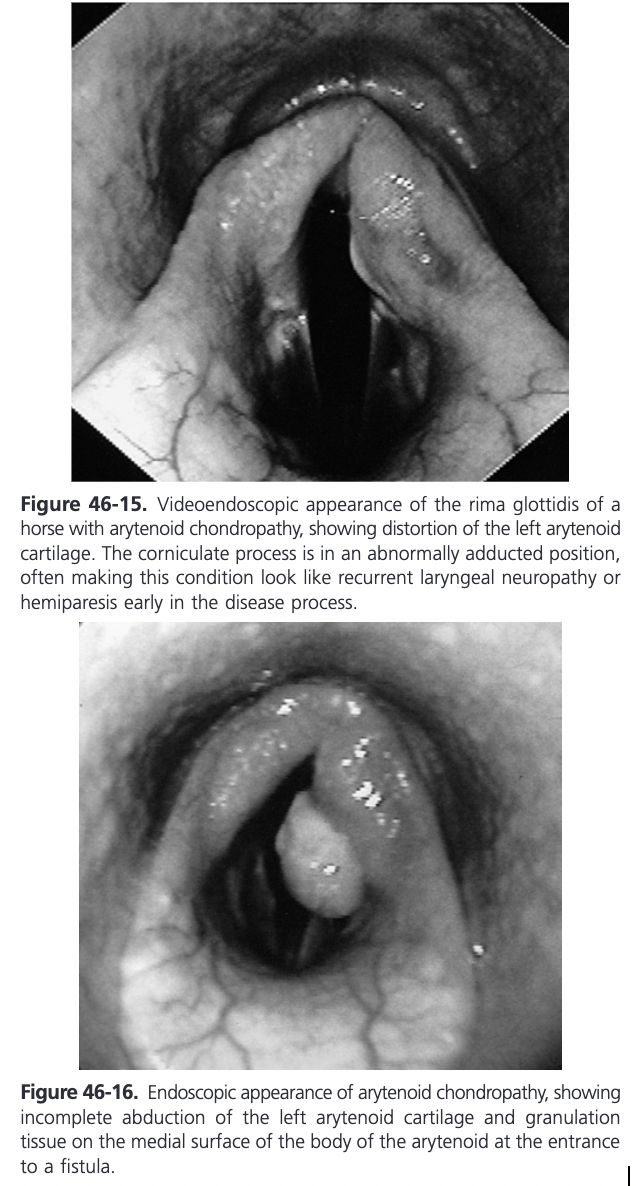

Arytenoid Chondropathy

Disease of one or both arytenoid cartilages resulting in abnormal enlargement

Pathologic changes identified in affected cartilages include chondritis, chondrosis, chondroma formation, dysplasia, necrosis, perichondritis, granulating laryngitis, and abscessation

Proposed that mucosal injury is followed by ascending infection and subsequent inflammation of the underlying cartilage

Results in superficial chondritis with formation of granulation tissue and a fistulous tract, or if deeper infection occurs, the development of an abscess

Respiratory tract infection is likely very significant and can cause mucositis and mucosal injury

Trauma-induced mucosal injury from endoscopic examination, previous laryngeal surgery, inhaled or swallowed foreign objects, or from concussion from the opposing cartilage can occur

Inadvertent trauma of the arytenoid cartilages by nasogastric intubation can result in arytenoid inflammation but is unlikely to cause mucosal ulceration leading to chondropathy

Hereditary component also suggested in Thoroughbreds

Inflammatory processes involve not only the laryngeal mucosal surface and the arytenoid cartilages but also periarytneoid tissues and dorsal muscular structures

End result is usually fibrous tissue lamination, necrosis, deposition of poor-quality cartilage matrix, and mineralization of the laminar portion of primarily the body of the arytenoid cartilage

Frequently the affected cartilage has reduced mobility

Partial or complete failure of abduction is caused by the laterally positioned thyroid cartilage physically restricting movement and/or because the inflammatory process extends and impairs function of the cricoarytenoid joint or the dorsal cricoarytenoid muscle

Net outcome is a reduced rima glottidis aperture and airflow compromise

Arytenoid Chondropathy History and Clinical Signs

Can be acute but more commonly chronic and affects all breeds and ages of horses causing respiratory obstruction and exercise intolerance

In working horses, typically young racing horses, signs are not detected at rest but occur during strenous exercise where even small changes in the cross-sectional area of the rima glottidis caused by the chondropathy manifest as respiratory stridor and exercise intolerance

Disease can be asymptomatic but generally there is a slow progression of clinical signs

Because of the reduced respiratory demand in nonworking horses, the effects of arytenoid chondropathy are not recognized until there is marked airway narrowing and chronic disease is present

These horses commonly present with obvious respiratory noise or dyspnea during mild exercise or at rest

Typically affected horses are older and have an insidious onset of clinical signs with gradual worsening over months to years

Acute inflammatory chondropathy results from generalized laryngitis (perichondral submucosal edema), causing a markedly reduced diameter of the rima glottidis and therefor stridor or dyspnea at rest

More common in older nonworking horses, where clinical signs can be rapid in onset and progress quickly and depression, fever, and leukocytosis may be present

The acute form of the disease may be an intermittent or severe manifestation of chronic inflammatory chondropathy

Acute disease has also been observed in yearling Thoroughbreds, associated with severe upper respiratory tract infections, including strangles

Arytenoid Chondropathy Diagnosis

Usually made during endoscopic examination of the larynx

RLN might be suspected because the arytenoid cartilage is in an adducted position and shows little movement

Affected cartilage is usually misshapen or distorted

One of the endoscopic hallmarks of arytenoid chondropathy is the presence of intraluminal projections of granulation tissue

Fistula or sinus tract in the center of the granulation tissue communicating with the body of the arytenoid is frequently present

A contact ulcer or projection of granulation tissue can often be seen on the opposing cartilage (kissing lesion) and the palatopharyngeal arch on the affected side is often more prominent

In acute chondropathy, the predominant endoscopic feature is mucosal and submucosal perchondral edema and perilaryngeal swelling with intense hyperemia

Thickening around the muscular process can be palpated in cases of arytenoid chondropathy and might be the only diagnostic finding on palpation

Larynx may feel less resilient to digital palpation and firm manual pressure may cause stridor or dyspnea

Radiographic features of arytenoid chondropathy include abnormal patterns of cartilage mineralization, increased density of the arytenoid cartilages, abnormal contour or size of the corniculate process, obliteration of the laryngeal ventricle, and laryngeal masses

Extensive mineralization of the larynx is a poor prognostic sign for successful surgical treatment

Arytenoid Chondropathy Treatment

Depends on the stage of the disease (acute or chronic), the degree of airway dysfunction, and whether athletic activity is required

In the acute form, horses may be presented in respiratory distress and stertor with laryngeal edema

Medical therapy with broad spectrum antibiotics, NSAIDs, and/or steroids and throat sprays often resolves the condition but occasionally an emergency tracheotomy is required

7-10 day course of treatment followed by endoscopic re-evaluation

In some animals, the chondropathy regresses and arytenoid cartilage function returns to normal or near normal

In other animals, chronic chondropathy ensues, but if airway obstruction is not severe, it is possible for some athletic animals to continue to compete

In cases where rima glottidis size is reduced because of granulation tissue or cartilage abscessation but arytenoid function is acceptable, local excision or drainage using endoscopic scissors, laser therapy, or local curettage can be attempted

If cartilage function is significantly impaired and/or the laminar portion of the arytenoid cartilage is thickened sufficiently (chronic form), surgical removal of the affected arytenoid cartilage is usually necessary

Condition is most often unilateral and therefore treated with unilateral arytenoidectomy

If the condition is bilateral, unilateral arytenoidectomy of the most affected cartilage may be sufficient

Some believe bilateral arytenoidectomy is inevitable and prefer a single-stage procedure

Considered a salvage procedure

Permanent tracheostomy is a valid procedure for bilateral disease in nonathletic animals and has been used with good results in Thoroughbred broodmares with the disease

Arytenoidectomy

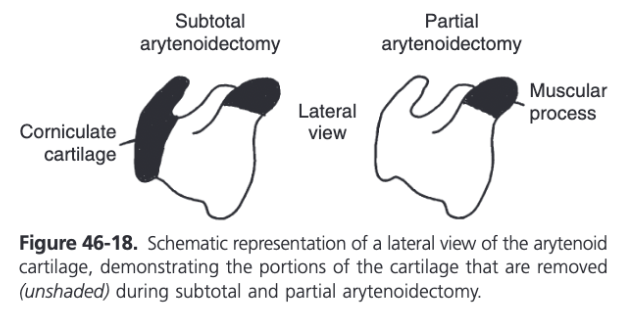

Two methods described:

Subtotal - the muscular process and rim of the corniculate process are left intact

Partial - only the muscular process is left intact

In a quantitative evaluation in 1990, it was demonstrated that subtotal arytenoidectomy failed to improve upper airway function in horses exercising on a high-speed treadmill with surgically induced left laryngeal hemiplegia (Belknap et al, 1990)

The effect of partial arytenoidectomy on upper airway function was evaluated by tidal breathing flow-volume analysis, measurement of upper airway impedance, and videoendoscopic examination of the larynx in strenuously exercising horses with surgically induced left laryngeal hemiplegia in 1994 (Lumsden et al, 1994)

Partial arytenoidectomy improved upper airway function in exercising horses with surgically induced left laryngeal hemiplegia and was superior to subtotal arytenoidectomy as a treatment for both failed laryngoplasty and arytenoid chondropathy

Number of methods and modifications for partial arytenoidectomy

Controversy exists over whether the mucosa on the medial surface of the arytenoid cartilage should be retained and sutured closed for primary wound healing or if complete resection of the cartilage with attached mucosa gives the best results

Recommend combining a partial arytenoidectomy with a ventriculocordectomy, removing all devitalized and redundant mucosa, and suturing the lesion so that all excised mucosal edges are apposed and the luminal surface is as smooth as possible

Any redundant tissue left in the airway creates turbulence and noise and may interfere with airway function

Such tissue should be removed at 30 days after surgery via laser ablation before cicatrix formation and mineralization make it impossible

Ventriculocordectomy site is left open for ventral drainage

Most rostral and lateral mucosa covering the corniculate cartilage should be retained

Partial arytenoidectomy does not completely restore the upper airway to normal but that the procedure is a viable treatment option for arytenoid cartilage malfunction in the horse

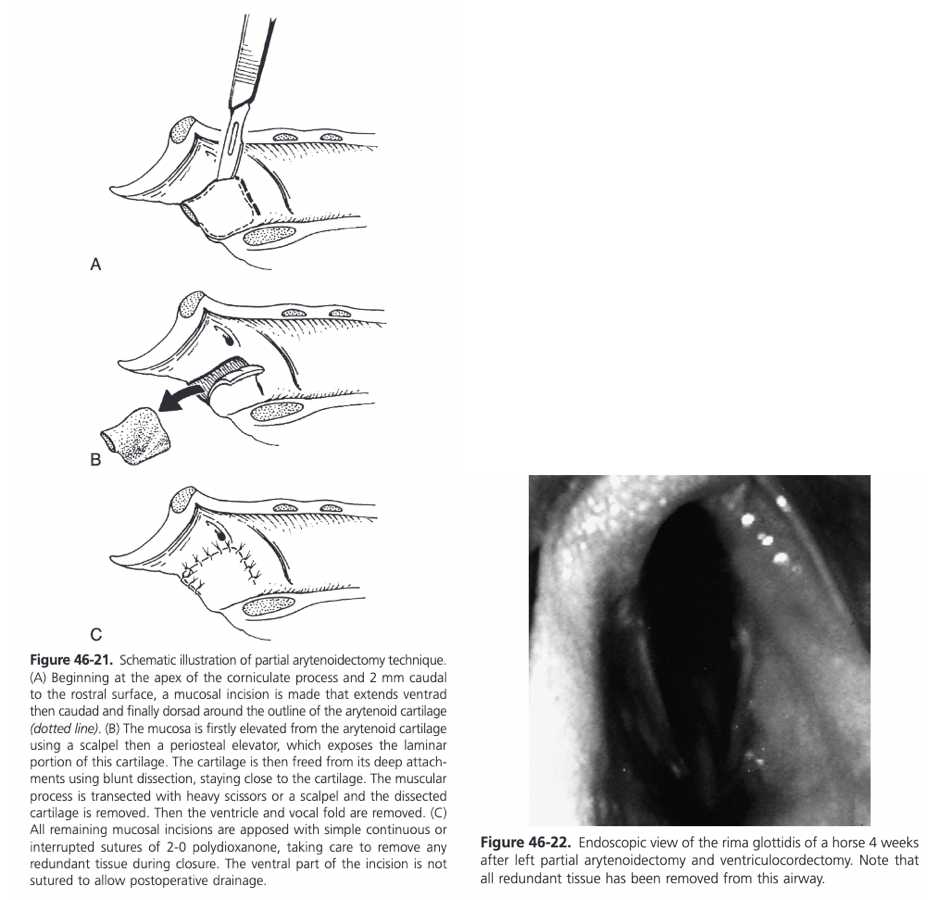

Partial Arytenoidectomy

Dorsal recumbency under GA with endotracheal tube placed through a tracheotomy

Endoscope placed via the nostril with the tip positioned in the dorsal pharynx is useful for illumination of the surgical site, as is a headlamp

Ventral laryngotomy performed

For increased exposure, the cricoid cartilage can be split longitudinally, as can the body of the thyroid if needed

Submucosal injection of epinephrine helps to elevate the mucosal membrane and to control bleeding

Using a #15 scalpel, a dorsally based U-shaped mucosal flap is made overlying the arytenoid cartilage

Mucosal incision starts at the apex of the corniculate cartilage 2 mm caudal to the rostral surface and extends ventrad then caudad and finally dorsad around the outline of the arytenoid cartilage forming a three-sided U-shaped incision

If the mucosa on the luminal side of the arytenoid cartilage is not too compromised it is elevated started caudad and working rostrad toward the corniculate portion

A scalpel is used to sharply undermine the mucosal tissue initially, and then the dissection is completed with a periosteal elevator, leaving the dorsal mucosa attached

Lateral surface of the arytenoid cartilage is freed from its soft tissue attachments using blunt dissection, staying close to the cartilage, and the remaining mucosa over the rostral and lateral aspect of the corniculate cartilage is separated using sharp and blunt dissection

Arytenoid cartilage is elevated rostrally using Allis tissue forceps or a towel clamp and the muscular process is transected using heavy Mayo scissors or a scalpel

Any diseased or irregular cartilage attached to the muscular process dorsally is removed with rongeurs

Ventriculocordectomy is performed by incising the mucosa around the orifice of the ventricle and removing the entire saccule, followed by resection of the cord

Rostral and lateral corniculate mucosa is retracted slightly caudad and sutured with minimal tension to the leading rostrall edge of the mucosa flap using interrupted or continuous suture

Obliteration of the piriform recess should be avoided by not pulling the leading edge of this tissue caudal to the palatopharyngeal arch

Remainder of the mucosal flap is sutured to the adjacent laryngeal mucosa similarly but leaving the ventral part of the incision open for drainage

Ventriculocordectomy incisions are not sutured

Large mucosal defects are left unsutured to heal by second intention, and the corniculate mucosa is sutured laterally to the remaining soft tissues

If the cricoid cartilage was divided the two sides are brought into close apposition by suturing the soft tissues immediately ventral to the cartilage ends in a simple interrupted or cruciate pattern

Don't place sutures through the cartilage to prevent chondroma formation

Laryngotomy left unsutured because of possibility of laryngeal edema and subsequent airway obstruction

Food is withheld for 24 hours at which time the larynx is evaluated endoscopically and airway patency is assessed

When feed is reintroduced at 24 hours, only wet hay should be fed from the ground until the horse is able to swallow without coughing

Stall rest for 4-6 weeks prior to complete healing which usually occurs within 8-10 weeks

In clinical cases, 62% of Thoroughbreds raced successfully after the treatment of unilateral arytenoid chondropathy

Modification of Partial Arytenoidectomy

Modification of the technique has been described experimentally and used clinically

Flap of mucosa on the luminal or medial side of the arytenoid cartilage is not elevated and retained for suturing, instead the arytenoid cartilage is removed in two pieces with accompanying mucosa attached, one with the body of the arytenoid and the other with the corniculate process

The rostral and lateral mucosa overlying the corniculate process is retained and together with the continuous arypepiglottic fold is drawn caudad over the defect left by arytenoid cartilage removal and sutured with 3-0 absorbable suture material in a continuous pattern, leaving only the ventral 5 mm of the repair open to drain at the site of the ventriculocordectomy

Proposed benefits include easier dissection, shorter surgery time, and a reduction in the amount of soft tissue lining the airway, which could be subjected to dynamic collapse during fast exercise

Experimental and clinical studies did not show an increased incidence of postoperative dysphagia or coughing using this modification

Different techniques or modifications for partial arytenoidectomy have been described but not critically compared

Partial artyenoidectomy with or without primary mucosal closure can be performed

Proposed benefits or primary mucosal closure include a faster healing time, reduction in postoperative excessive granulation tissue production, and an ability to streamline or smooth the luminal surface of the wound

Some elect to perform all partial arytenoidectomies without mucosal closure citing quicker surgery time, prevention of hematoma formation, and no suture dehiscence problems

Healing time in one study of unsutured partial arytenoidectomies was only 8 weeks, similar to that reported for primary mucosal closure

The number of horses racing three or more times after surgery was only 55% compared to 63% of horses treated with primary mucosal closure in another report

Complications of Arytenoidectomy

Dyspnea and dysphagia are the most important complications

Dyspnea occurs as a result of edema or hemorrhage trapped under the sutured mucosal flap

Dysphagia with regurgiatation of food and water through the nares has been reported in up to 36% of horses after arytenoidectomy, however significant dysphagia was not encountered in more recent reports

It has been proposed that atraumatic transection of the body of the arytenoid from the muscular process and of the soft tissue attachments on the lateral surface of the arytenoid cartilage may reduce problems with degluttion after surgery

Maintaining sufficient rostral mucosa, especially of the ventral part of the repair is also suggested to reduce aspiration

Coughing during eating is common and may continue for some months

One study showed horses with induced RLN subjected to a partial arytenoidectomy had significant increases in neutrophils and macrophages containing intracellular bacteria as well as an increase in the number of lymphocytes in transbronchial fluid aspirates taken 30 minutes after strenuous exercise (Radcliffe et al, 2006)

Formation of intralaryngeal granulation tissue was identified 1 month after surgery in 17% of horses treated with partial arytenoidectomy (typically at the dorsal aspect of the rostral part of the incision

Granulation tissue and any excess mucosa should be excised using a transendoscopic laser or endoscopic scissors at this time

Advanced laryngeal cartilage mineralization rendering horses useless for work was reported in 5% of horses treated with a partial arytenoidectomy

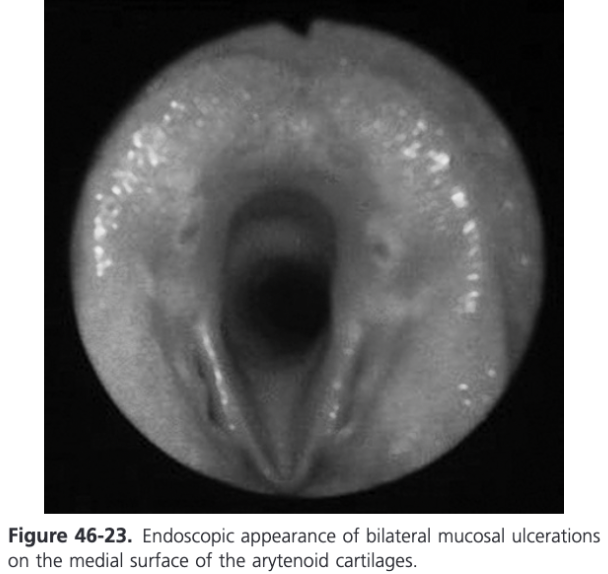

Mucosal Disease of the Arytenoid Cartilages in Young Thoroughbreds in Australia and New Zealand

Mucosal disease of the arytenoid cartilages in young Thoroughbred horses in Australia and New Zealand has been described

Bilateral kissing lesions are found on or near the vocal processes just proximal to the attachment of the vocal cords

Etiology is unknown so this had been termed idiopathic mucosal lesions

Manifest as small erosions or ulcer or raised areas of epithelial injury

Often hyperemic and can have small, slightly purulent centers

Incidence of mucosal lesions in two surveys of Thoroughbred yearlings presented to public auction sales was 0.6%, the incidence of arytenoid chondropathy was 0.21%

In a population of racing Thoroughbreds, 2.4% had mucosal lesions

These lesions do not affect subsequent racing performance and many heal uneventfully with or without medical therapy

Treatment is recommended because in one report, lesions progressed to granulomas in 10% and to arytenoid chondropathy in 5% of the affected horses (Kelly et al, 2003)

Broad spectrum antibiotics, NSAIDs, and pharyngeal washes are recommended for 10-14 days

Granulomas of the Arytenoid Cartilage

Occasionally, particularly in Thoroughbred and Standardbred racehorses, a mass projecting from the medial surface of the arytenoid cartilage at its junction with the corniculate process just dorsal to the insertion of the vocal cord is seen on endoscopic examination

Commonly referred to as chondromas, however histologic examination of the excised tissue reveals granulation tissue with or without underlying cartilage disease

An ulcerated mucosal defect is often seen on the medial surface of the opposing arytenoid where the granulation tissue rubs during laryngeal adduction

Pathology may extend in the underlying body of the arytenoid cartilage with or without abscessation

If abductor function of the affected cartilage is normal or only slightly reduced, the mass should be removed to improve airflow, prevent further advancement of chondropathy, and protect the opposite cartilage from contact injury

This technique may be temporarily successful when combined with antibiotic and antiinflammatory therapy in some performance horses and many sedentary patients

Recurrence and progression of the disease may necessitate a further surgical approach such as drainage of the abscess and arytenoidectomy

Options for treatment include laryngotomy followed by scalpel or laser excision and focal curettage under GA or transendoscopic laser excision in the standing sedated patient

Treatment of Granulomas of the Arytenoid Cartilages

A dissection plane is established at the perimeter of the mass between the granulation tissue and the underlying cartilage, either with a laser or an endoscopic scissor

The mass is completely freed up except for small remaining tags of attachment and it is retrieved with the equine laryngeal grasping forceps

Gaining access to the medial aspect of the cartilage can be difficult

A more direct approach can be made by introducing a laser fiber through a 5 mm by 6.5 cm trocar inserted through a stab incision through the cricothyroid membrane

Exercise is restricted until the defect heals

Regrowth of the granulation tissue can occur in 16% of horses requiring a second procedure but in some cases the regrowth regressed with medical therapy and time

Prognosis for Granulomas of the Arytenoid Cartilages

Depends on the nature and extent of the disease and the respiratory demands placed on the patient

If treatment is instituted early, the condition is unilateral, and arytenoid function is minimally affected, medical management can halt progression, and in one study palliative treatment allowed some horses to race for 1-2 years (Tulleners, Harrison, and Raker, 1988)

The likelihood of Thoroughbred horses with idiopathic arytenoid mucosal lesions racing more than three times is not different from unaffected control animals

Excision of intralaryngeal granulation tissue in nonracehorses has an excellent prognosis

A group of five racehorses with only slight cartilage thickening and no other laryngeal pathology all returned to racing three or more times with only one having reduced performance after treatment

If moderate cartilage thickening is present or concurrent laryngeal pathology exists, only 50% of treated horses returned to racing and usually at a lower level of performance

Prognosis for Partial Arytenoidectomy

Partial artyenoidectomy is very effective in restoring rima glottidis diameter, but prognosis depends on the respiratory demands for exercise

75% of horses with occupations other than racing were useful after partial arytenoidectomy was performed for unilateral chondropathy, bilateral chondropathy, or failed laryngoplasty

In general, the prognosis in nonworking horses treated with partial arytenoidectomy is favorable but is reduced in cases of advanced unilateral chondropathy accompanied by complicating lesions

Even horses with bilateral arytenoidectomy may have a better prognosis for survival compared to those with advanced unilateral chondropathy and accompanying lesions

In these horses a permanent tracheostomy might be a better option

The prognosis for athletic activity after partial arytenoidectomy in working horses, primarily racing Thoroughbreds has been reported to be between 45 and 80%

It is likely that partial arytenoidectomy for the treatment of arytenoid chondropathy will allow two thirds or more of treated horses to train, race, and earn money

A shortened athletic career is likely

Bilateral partial arytenoidectomy for bilateral arytenoid chondropathy is a salvage procedure and carries a poor prognosis for continued racing (22%)

Epiglottis

A vascular pattern is present on the dorsal surface with a main vessel on either side that courses from the base toward the tip, parallel to and approximately 8-10 mm in from the margin

From these two major vessels, small perpendicular branches are seen coursing toward the epiglottic margins

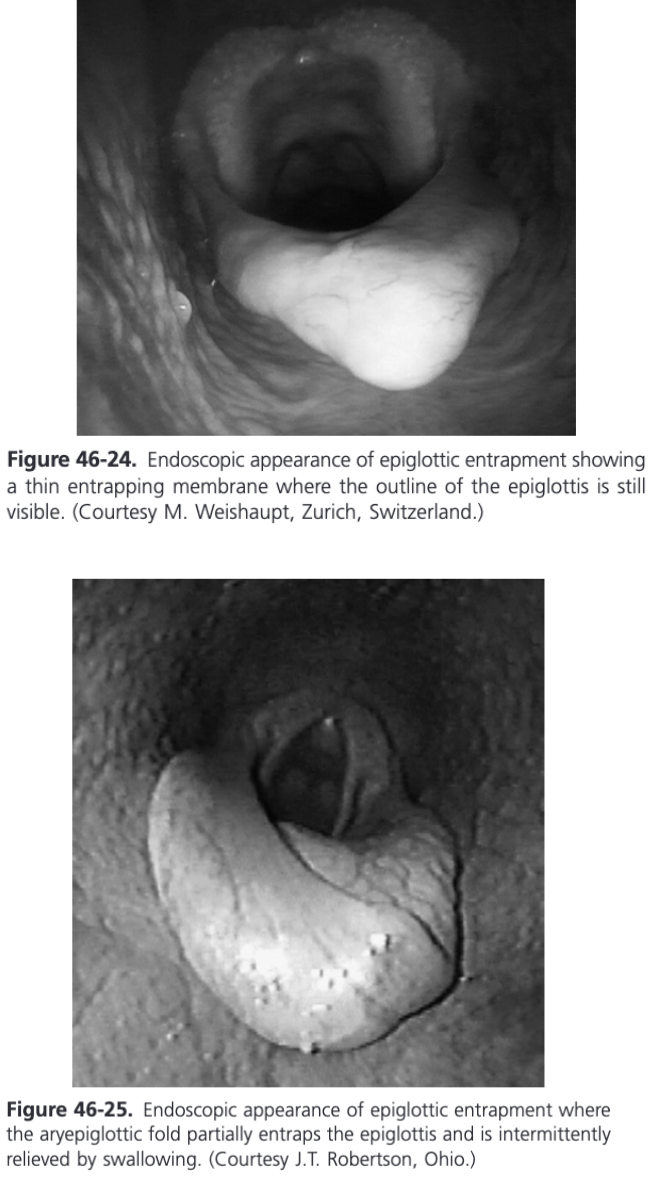

Epiglottic Entrapment

Epiglottic entrapment occurs when the loose subepiglottic mucosa membrane becomes positioned above the dorsal epiglottic surface and then appears continuous with the aryepiglottic folds

Common cause of abnormal respiratory noise and often, but not always, exercise intolerance

Other less frequent complaints associated with epiglottic entrapment are coughing and nasal discharge, sometimes after drinking

Occasionally an incidental finding

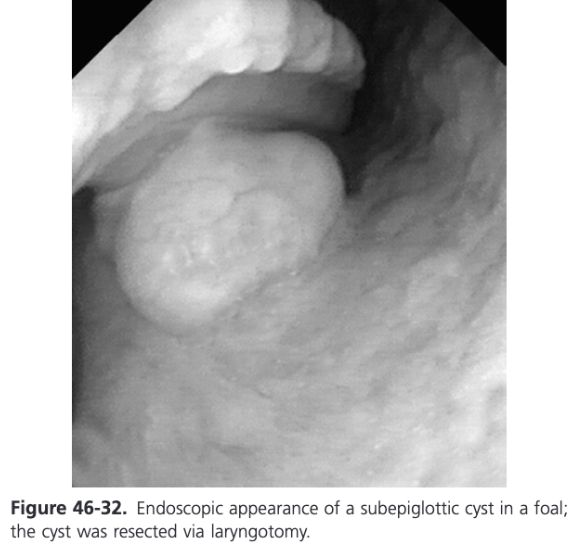

Epiglottic Entrapment Diagnosis