9 - periodic table

1/86

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

87 Terms

periodicity

the repeating patterns or trends in the chemical and physical properties of elements as they are arranged by atomic number in the periodic table (in periods)

atomic radius

the distance between the nucleus and the outermost electron of an atom

The atomic radius is measured by taking two atoms of the same element, measuring the distance between their nuclei and then halving this distance

metallic radiys

Half the distance between the nuclei of neighbouring ions in a metallic crystal.

covalent radius

Half the distance between the nuclei of covalently bonded atoms.

van der waal’s radius

Half the distance between the nuclei of neighbouring atoms or molecules/ the closest distance another atom can approach it without encountering significant repulsive forces

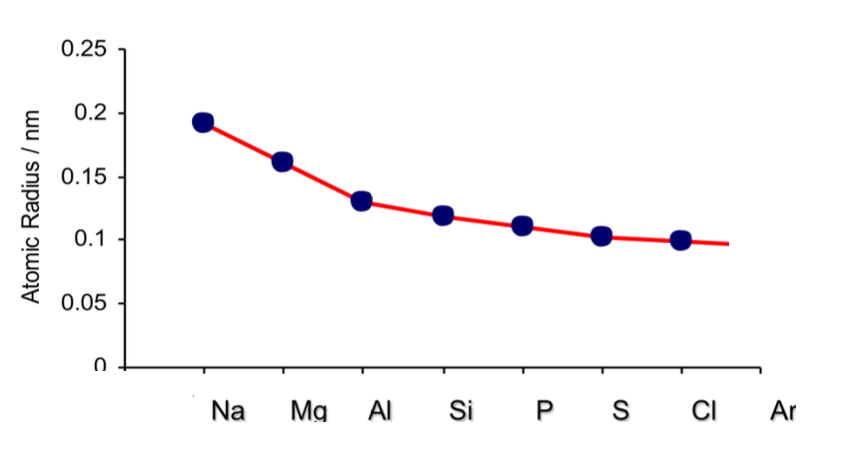

atomic radii across a period

Across the period, the atomic radii decrease

This is because the number of protons (the nuclear charge) and the number of electrons increases by one every time you go an element to the right

The elements in a period all have the same number of shells (so the shielding effect is the same)

This means that as you go across the period the nucleus attracts the electrons more strongly pulling them closerto the nucleus

Because of this, the atomic radius (and thus the size of the atoms) decreases across the period

why are noble gases excluded from graphs that show the variation of atomic radii across a period

They don’t form covalent bonds

Atomic radius for most elements is measured using the covalent radius

Noble gases rarely form covalent bonds because they have full outer electron shells and are chemically unreactive/inert.

so they don’t have standard covalent radii, making their atomic size difficult to compare fairly.

Their radii are measured differently

Instead of covalent radius, noble gases are usually assigned a van der Waals radius.

Van der Waals radii are typically larger than covalent radii, so noble gases appear artificially large on a graph.

They break the smooth trend

Across a period, atomic radius generally decreases smoothly from left to right due to increasing nuclear charge.

Noble gases have unusually small, tightly held electron clouds despite their large van der Waals radii, causing inconsistencies in the trend if included.

Including them would create a sudden drop or irregularity in the graph that doesn’t reflect the true trend based on bonding atoms.

They are not directly comparable

Because their radii are measured differently and they don’t behave like other elements in terms of bonding and electron attraction, comparing noble gases to other elements would be inconsistent.

ionic radius

the distance between the nucleus and the outermost electron of an ion

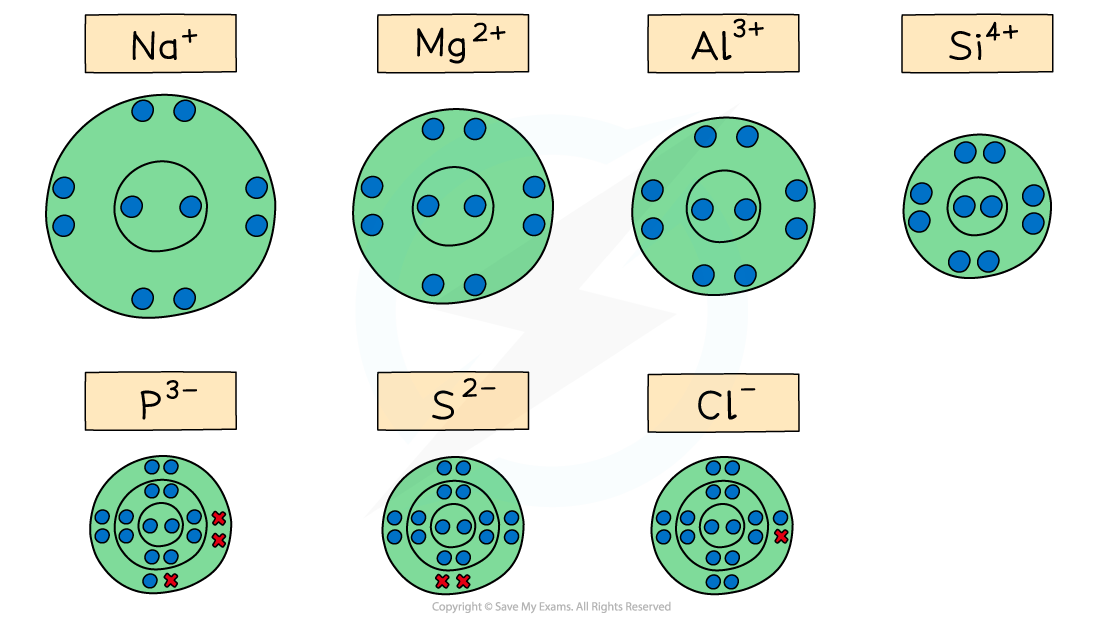

cationic and anionic radii

Metals produce cations whereas nonmetals produce anions

The cations have lost a complete shell and their valence electrons which causes them to be much smaller than their parent atoms

This is because there are less electrons, which also means that there is less shielding of the outer electrons

The anions are larger than their original parent atoms because each atom has gained one or more electrons in their third principal quantum shell

This increases the repulsion between electrons, while the nuclear charge is still the same, causing the electron cloud to spread out

ionic radii across a period

Going across the period from Na+ to Si4+ the ions get smaller due to the increasing nuclear charge attracting the outer electrons in the second principal quantum shell nucleus (which has an increasing atomic number)

Going across P3- to Cl-, the ionic radii decrease as the nuclear charge increases across the period and fewer electrons are gained by the atoms (P gains 3 electrons, S 2 electrons and Cl 1 electron)

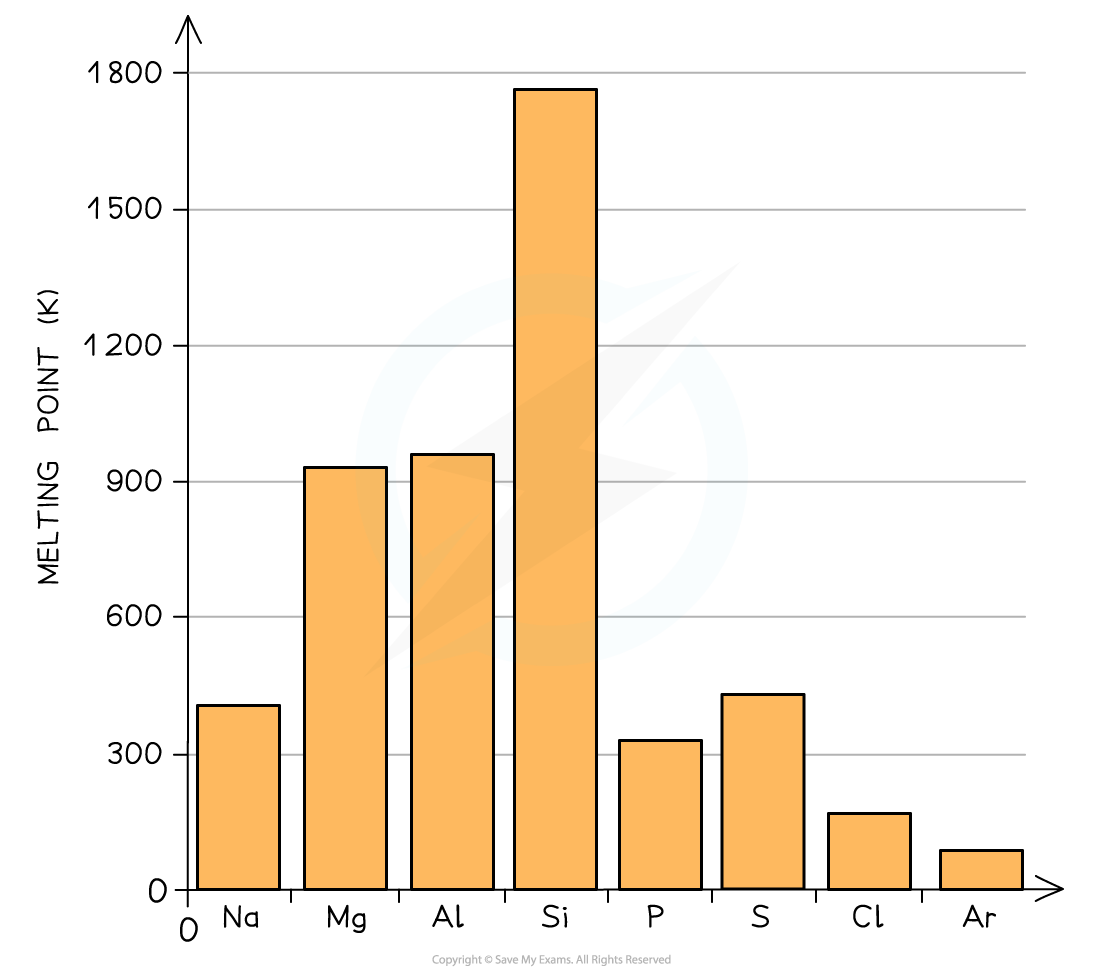

melting points across period 3 - describe general trend.

Period 3 element

Na - 371

Mg - 923

Al - 932

Si - 1683

P - 317

S - 392

Cl - 172

Ar - 84

(melting points in K)

The melting point of an element is determined by its structure. The highest melting point is observed in Group VI elements which have a giant covalent structure. The lowest is observed in the noble gases which exist as single atoms with very weak van der Waals’ forces.

A general increase in melting point for the Period 3 elements up to silicon

Silicon has the highest melting point

After the Si element, the melting points of the elements decrease significantly

explanation of melting points for period 3 elements

1. Sodium (Na), Magnesium (Mg), Aluminium (Al):

These elements have metallic structures, consisting of positive metal cations in a sea of delocalised electrons.

The melting points depend on the strength of metallic bonding, which:

Increases from Na to Al,

Due to a greater number of delocalised electrons (Na donates 1, Mg donates 2, Al donates 3),

And smaller cation size (Na⁺ > Mg²⁺ > Al³⁺).

Stronger metallic bonding leads to higher melting points as you move from Na → Mg → Al.

The electrostatic attraction between Al³⁺ ions and a larger number of delocalised electrons is much stronger than in Na⁺, hence Al has a significantly higher melting point.

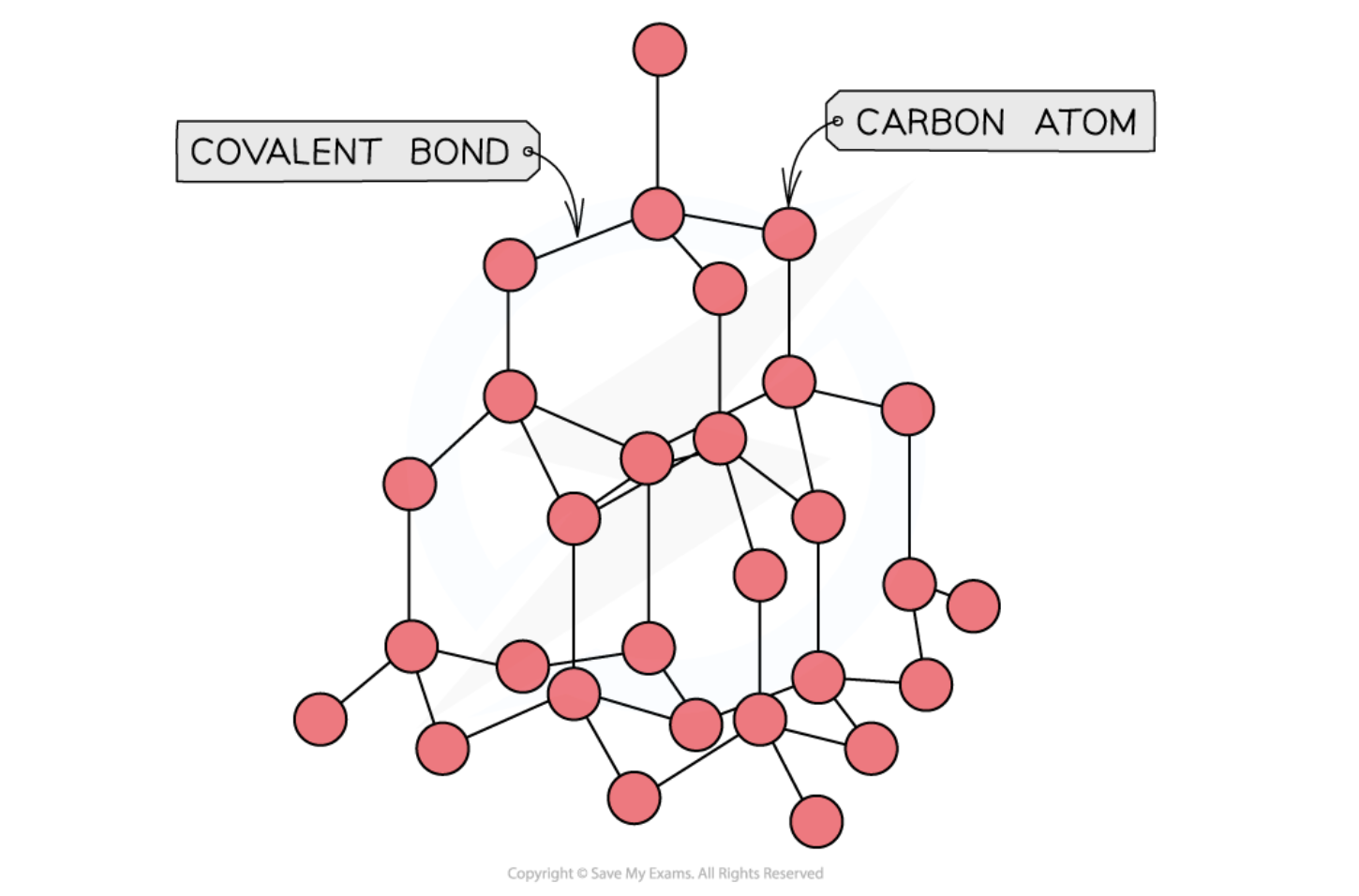

2. Silicon (Si):

Si has a giant covalent (macromolecular) structure, where each Si atom forms strong covalent bonds with four other Si atoms in a 3D tetrahedral network.

Breaking this structure requires a large amount of energy because many strong covalent bonds must be broken.

Therefore, silicon has the highest melting point across Period 3.

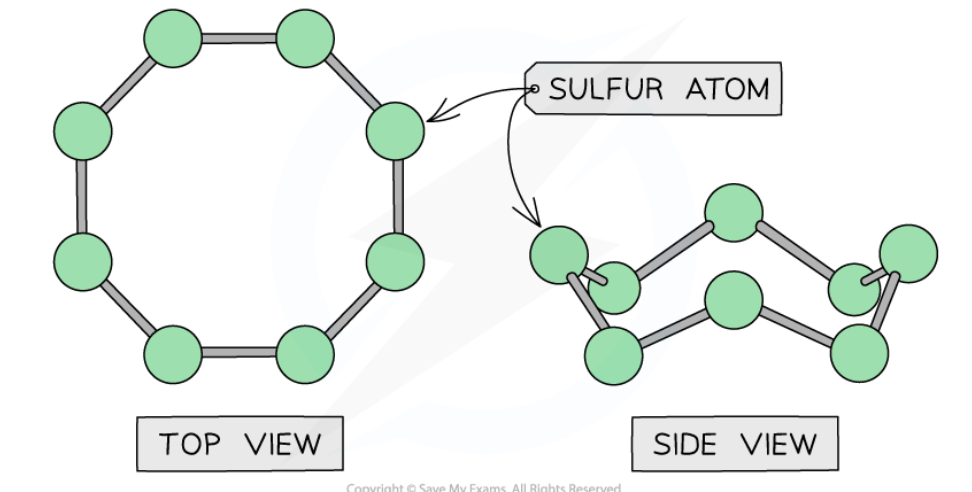

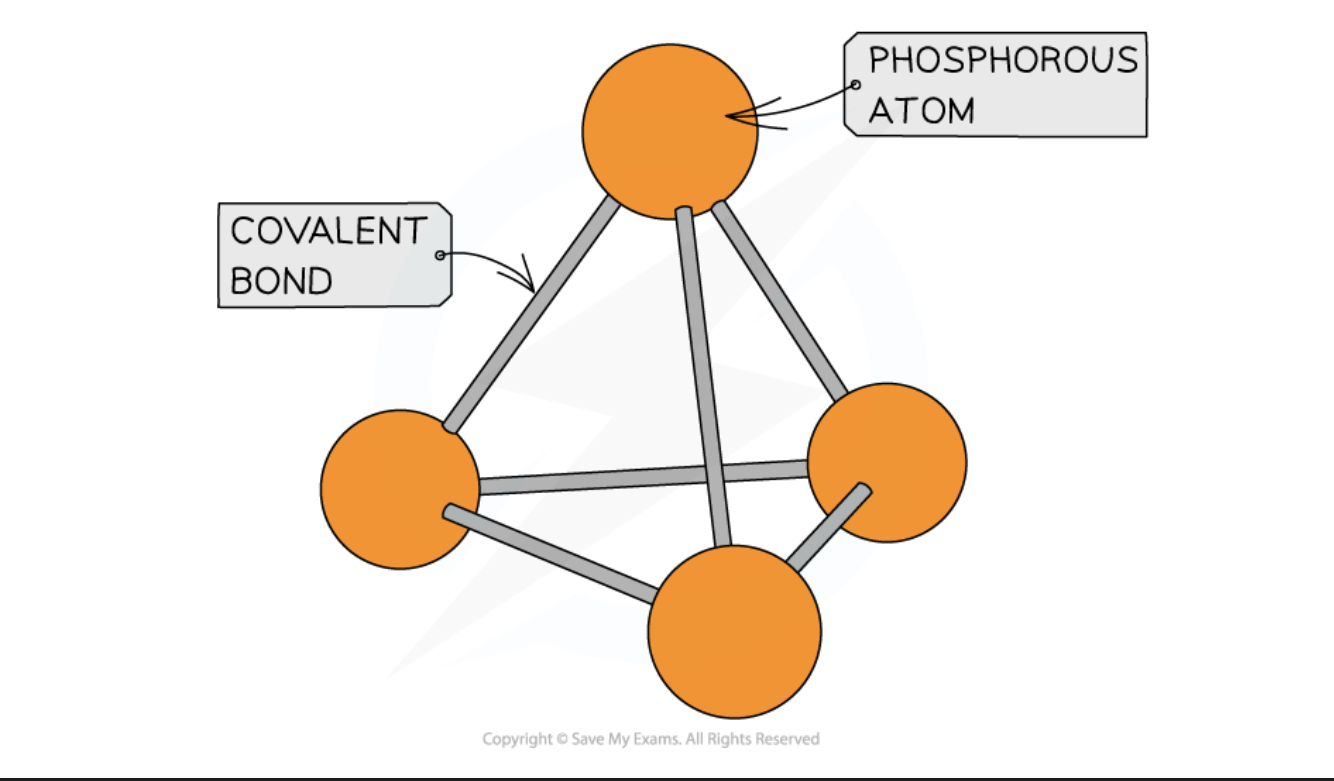

3. Phosphorus (P₄), Sulfur (S₈), Chlorine (Cl₂):

These are non-metals with simple molecular covalent structures.

The individual molecules are held together by weak van der Waals’ (induced dipole-induced dipole) forces.

The strength of these intermolecular forces depends on:

The size of the molecule, and

The number of electrons.

Sulfur (S₈) has the highest melting point among them because:

It exists as larger S₈ rings with more electrons, creating stronger van der Waals’ forces.

Phosphorus (P₄) is smaller (tetrahedral structure), with fewer electrons, so its melting point is lower than S₈.

Chlorine (Cl₂) is even smaller and has weaker van der Waals’ forces, so it has the lowest melting point among the three.

4. Argon (Ar):

Argon is monatomic and exists as single atoms.

It has very few electrons and forms very weak van der Waals’ forces between atoms.

As a result, argon has the lowest melting and boiling point of all Period 3 elements.

electrical conductivity

refers to how well a substance can conduct electricity

electrical conductivity across period 3

he electrical conductivity decreases going across the Period 3 elements

From sodium (Na) to aluminium (Al), electrical conductivity increases. This is because these three elements are metals with a structure consisting of positive metal ions in a sea of delocalised electrons. As you go from Na → Mg → Al:

The number of delocalised electrons per atom increases (Na donates 1, Mg donates 2, Al donates 3).

More delocalised electrons means more charge carriers, so conductivity increases across these metals.

Aluminium is the best conductor among them because it has the most delocalised electrons and a higher charge density (small ion, high charge), allowing electrons to move more easily through the structure.

At silicon (Si), conductivity drops sharply. Silicon has a giant covalent (macromolecular) structure where electrons are held tightly in covalent bonds and not free to move. However, Si is a semiconductor — under certain conditions (e.g. heat, doping), a small number of electrons can become mobile and conduct electricity.

From phosphorus (P) to argon (Ar), the elements are simple molecular substances. Their structures consist of discrete molecules held together by weak van der Waals forces. These elements:

Have no delocalised electrons,

Do not conduct electricity in solid or liquid form,

And are classified as non-conductors.

reaction of period 3 elements with oxygen: sodium

Sodium burns (in heat) vigorously in oxygen with a bright yellow flame to produce a white ionic solid - sodium oxide. Freshly cut sodium metal tarnishes rapidly on exposure to air.

4Na (s) + O2 (g) → 2Na2O (s)

reaction - vigorous

reaction of magnesium with oxygen

burns in oxygen with a bright/brilliant white flame to produce magnesium oxide - a white ionic solid.

2Mg (s) + O2 (g) → 2MgO (s)

reaction - vigorous

reaction of aluminium with oxygen

burns in oxygen if it is powdered, otherwise the strong oxide layer on Al tends to inhibit the reaction. if you sprinkle aluminium powder into a bunsen fame, you get bright white sparkles and aluminium oxide is formed - a white ionic powder.

4Al (s) + 3O2 (g) → 2Al2O3 (s)

reaction - fast

reaction of silicon with oxygen

No reaction at room temperature. Silicon will burn in oxygen if heated strongly and if powdered - burns with bright white sparkles. Silicon dioxide is produced which is a white giant covalent powder.

Si (s) + O2(g) → SiO2 (s)

reaction - slow

reaction of phosphorus with oxygen

White phosphorus catches fire spontaneously in excess air, burning with a yellow or white flame and producing white oxide (seen as white fumes when formed in combustion because it is initially produced as tiny solid particles suspended in hot gases. These particles disperse in the air like smoke or mist, which we describe as fumes.). Red phosphorus catches fire on heating.

4P (s) + 5O2 (g) → P4O10 (s)

or

P4 (s) + 5O2 (g) → P4O10 (s) (because white phosphorus typically exists as P4)

reaction - vigorous

conditions - excess oxygen

reaction of sulfur with oxygen

Sulfur burns in air or oxygen when powdered on heating - creates a blue flame. It produces colourless sulfur dioxide gas (toxic fumes)

S (s) + O2(g) → SO2(g)

reaction - gentle

reaction of chlorine with oxygen

Chlorine does not react directly with oxygen though its oxides are present (While chlorine and oxygen can be part of the same compounds, those compounds are formed through indirect synthesis, not simple combination.)

reaction of period 3 elements with chlorine : sodium

Sodium burns in chlorine with a bright yellow flame. White solid sodium chloride is produced.

2Na (s) + Cl2 (g) → 2NaCl (s)

reaction - vigorous

reaction condition - heat

reaction of magnesium with chlorine

Magnesium burns with its usual intense white flame to give white magnesium chloride.

Mg (s) + Cl2 (g) → MgCl2 (s)

reaction - vigorous

reaction conditions - heat

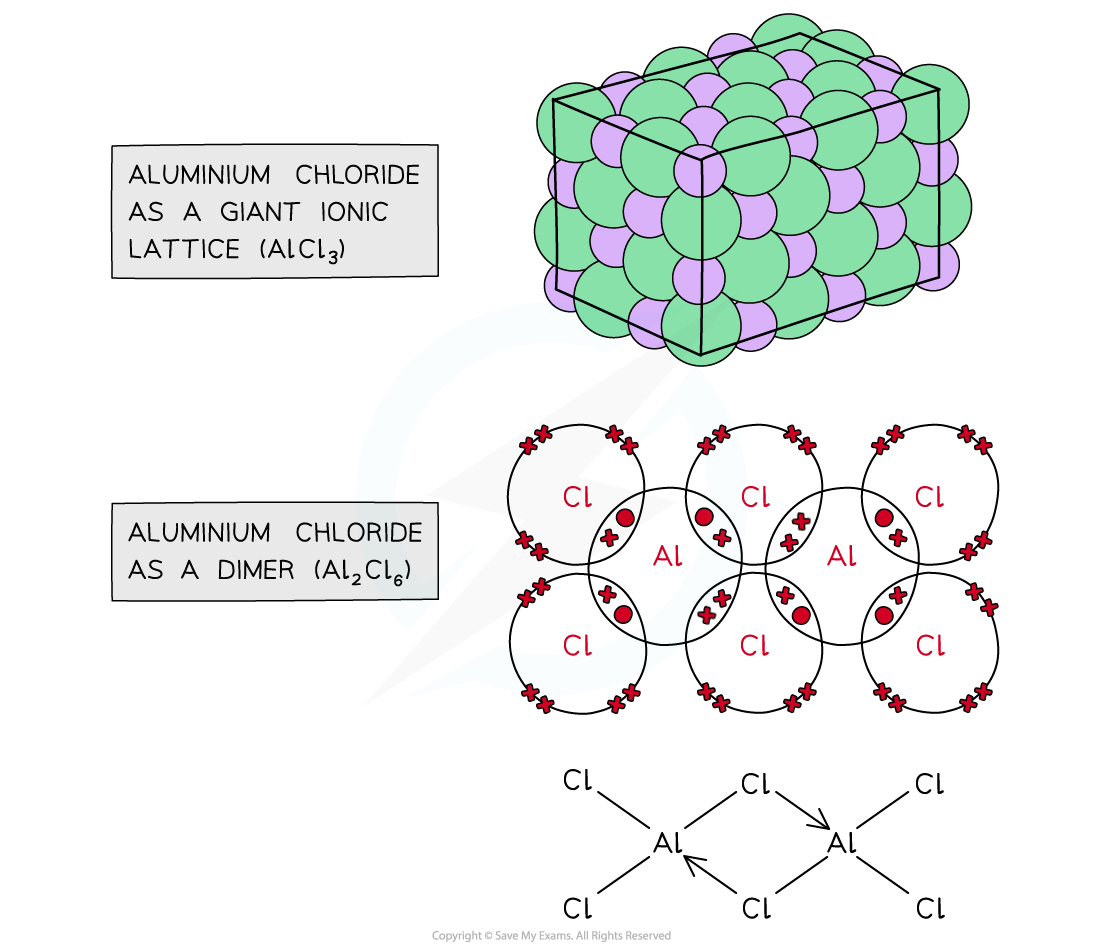

reaction of aluminium with chlorine

Aluminium is often reacted with chlorine by passing dry chlorine gas over heated aluminium foil in a long tube. The aluminium burns in the stream of chlorine to produce solid aluminium chloride, Al2Cl6, which appears as a very pale yellow (almost white) solid.

At room temperature and in the solid state, aluminium chloride exists as a dimer, Al2Cl6. This compound sublimes at around 180 °C, forming gaseous Al2Cl6 molecules.

When this vapour is heated to higher temperatures, the dimer dissociates into gaseous AlCl3 monomers:

2Al (s) + 3Cl2 (g) → Al2Cl6 (s)

reaction - vigorous

reaction conditions - heat

why does AlCl3 sublime (technically al2cl6 sublimes but alcl3 is just the empirical formula)

1⃣ Nature of Al₂Cl₆

Al₂Cl₆ is a covalent molecular compound (a dimer held together internally by covalent + coordinate bonds).

In the solid, those dimers are held together only by intermolecular forces — London dispersion forces + dipole–dipole interactions — which are much weaker than ionic or covalent bonding between molecules.

2⃣ Why It Sublimes

When you heat solid Al₂Cl₆, you don’t need to break any strong Al–Cl bonds — just the weak forces between the dimers.

Because these forces are weak, it doesn’t need much energy to separate molecules, so it sublimes at a relatively low temperature (~180 °C) instead of melting into a liquid first.

This is a typical property of simple molecular solids (like I₂, CO₂, naphthalene).

3⃣ Key Takeaway

Even though Al₂Cl₆ has dipole–dipole forces, they are still weak compared to ionic bonding. That’s why:

It’s volatile (can easily turn into gas)

It sublimes rather than melting into a liquid first

(only the dimer is polar, the monomer is non polar)

reaction of silicon with chlorine

If chlorine is passed over silicon powder heated in a tube, it reacts to produce silicon tetrachloride. This is a colourless liquid which vaporises readily and can be condensed further along the apparatus.

Si (s) + 2Cl2 (g) → SiCl4(l)

reaction - slow

reaction conditions - heat

reaction of phosphorus with chlorine

White phosphorus burns spontaneously in chlorine to produce phosphorus(V) chloride .

Phosphorus(V) chloride is an off-white (pale yellow) solid that forms when chlorine is in excess. (PCl3 is produced when chlorine is limited)

P4 (s) + 10Cl2 (g) → 4PCl5 (l)

reaction - vigorous

reaction conditions - excess chorine

Textbooks sometimes show the combustion of phosphorus as

4P + 5O2 → P4O10

But this shorthand isn’t safe for exams

Phosphorus exists as P4 molecules, as stated in the syllabus and mark schemes

So, you should write reactions with P4

Also, be careful with phosphorus(V) oxide:

Examiners expect the molecular formula P4O10, not the empirical formula P2O5

reaction of sulfur with chlorine

If a stream of chlorine is passed over some heated sulphur, it reacts to form an orange, foul smelling liquid, disulfur dichloride, S2Cl2.

2S (s) + Cl2 (g) → S2Cl2 (l)

which period 3 elements react with water

only sodium and magnesium

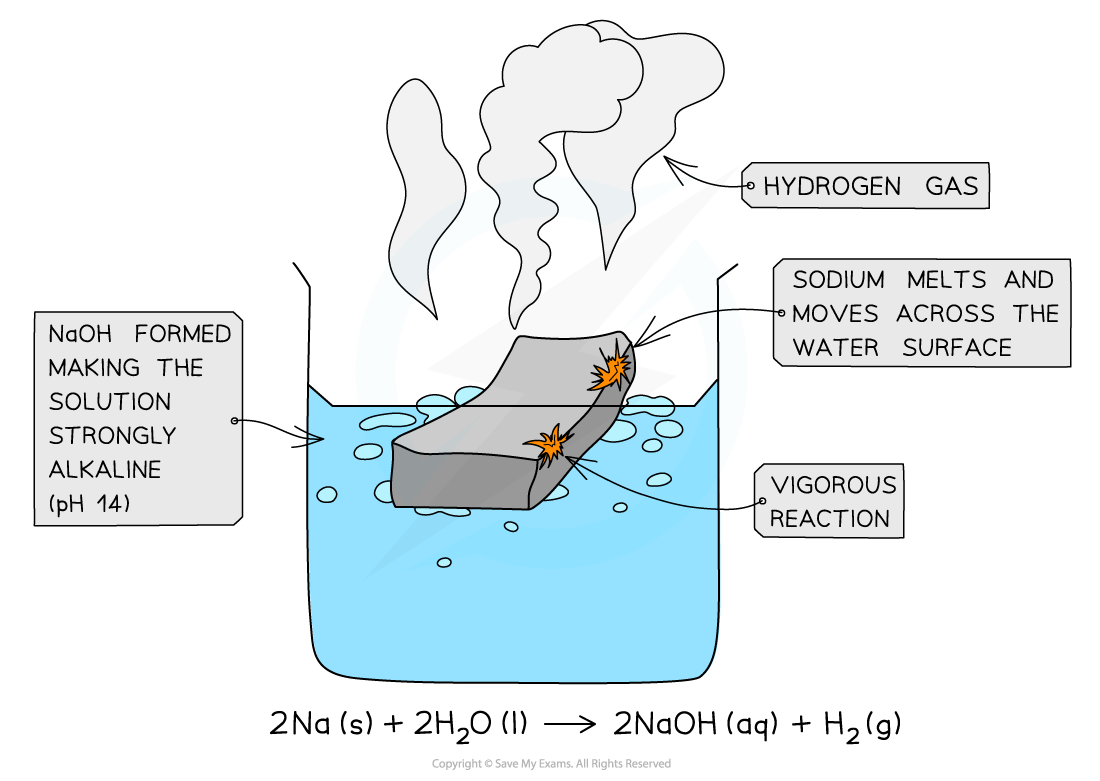

reaction of sodium with water

Sodium reacts vigorously with cold water:

2Na (s) + 2H2O (l) → 2NaOH (aq) + H2 (g)

The sodium melts into a ball and fizzes while moving across the water surface until it disappears

Hydrogen gas is given off

The solution formed is strongly alkaline (pH 14) due to the sodium hydroxide which is formed (a white ionic solid)

If it get stuck at one place, it can catch fire burning with a yellow flame.

reaction of magnesium with water

Magnesium reacts extremely slowly with cold water:

Mg (s) + 2H2O (l) → Mg(OH)2 (aq) + H2 (g)

The solution formed is weakly alkaline (pH 11) as the formed magnesium hydroxide is only slightly soluble

When magnesium is heated, it reacts vigorously with steam (water) to make magnesium oxide (a white ionic solid) and hydrogen gas:

Mg (s) + H2O (g) → MgO (s) + H2 (g)

Phosphorus exists as an allotrope. A common allotrope is P4and is known as white phosphorus. It can also exist as red phosphorus.

White phosphorus reacts spontaneously with excess oxygen to produce phosphorus(V) oxide via the following reaction.

P4 (s) + 5O2 (g) → P4O10 (s)

P4 (s) + 5O2 (g) → 2P2O5 (s)

-

oxidation number of period 3 elements in their chlorides

Chlorine is more electronegative than the other Period 3 elements

Therefore, the other Period 3 elements will generally have positive oxidation states in their chlorides, while the chlorine has a negative oxidation state of -1

oxidation number of period 3 elements in their oxides

Oxygen is more electronegative than any of the Period 3 elements

Therefore, the Period 3 elements will have positive oxidation states in their oxides, while the oxygen has a negative oxidation state of -2

The normal Oxidation Number Rules apply to the Period 3 oxides

examiner tip - SiO2 is not written in the specification as expected knowledge but you should be able to apply the oxidation number rules to this and other chemicals

-

reaction of period 3 oxides with water (not all period 3 oxides react with or are soluble with water): sodium oxide

Na2O (s) + H2O (l) → 2NaOH (aq)

forms a strongly alkaline solution of pH 12-14

reaction of magnesium oxide with water

MgO (s) + H2O (l) → Mg(OH)2 (aq)

forms a weakly alkaline solution of 8 - 10

At first glance, magnesium oxide powder does not appear to react with water. However, the pH of the resulting solution is about 9, indicating that hydroxide ions have been produced. In fact, some magnesium hydroxide is formed in the reaction, but as it is almost insoluble, few hydroxide ions actually dissolve.

reaction of aluminium oxide with water

Aluminum oxide is insoluble in water and does not react like sodium oxide and magnesium oxide. The oxide ions are held too strongly in the solid lattice to react with the water

reaction of silicon dioxide with water

Silicon dioxide does not react with water/is insoluble, due to the thermodynamic difficulty of breaking up its network covalent structure. (the energy cost of breaking the silicon dioxide lattice is extremely high. The energy gained from forming new interactions with water is too small. The overall process is thermodynamically unfavourable → it requires more energy input than it gives back, so the dissolution doesn’t happen.)

reaction of oxides of phosphorus with water

Phosphorus(V) oxide: Phosphorus(V) oxide reacts violently with water in vigorous reaction to give a solution containing phosphoric(V) acid, H3PO4 - a weakly acidic solution of pH 3-4

P4O10 (s) + 6H2O (l) → 4H3PO4 (aq)

reaction of oxides of sulfur with water - sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide: Sulfur dioxide reacts with water to give a solution of sulfurous acid (also known as sulfuric(IV) acid), H2SO3. This species only exists in solution, and any attempt to isolate it gives off sulfur dioxide.

SO2 (g) + H2O (l) ⇌ H2SO3 (aq)

solution formed is strongly acidic with a pH of 1-2

reaction of sulfur trioxide with water

Sulfur trioxide reacts violently with water to produce a fog of concentrated sulfuric acid droplets.

SO3 (g) + H2O (l) → H2SO4 (aq)

solution formed is strongly acidic with a pH of 1-2

reaction of chlorine (vii) oxide with water

Chlorine(VII) oxide reacts with water to give the very strong acid, chloric(VII) acid.

Cl2O7 (l) + H2O (l) → 2HClO4 (aq)

examiner tip - Since aluminium oxide does not react or dissolve in water, the oxide layer protects the aluminium metal from corrosion

The reaction of silicon(IV) oxide is not required knowledge

-

acid/base nature of period 3 oxides (summary)

Na₂O - basic

MgO - basic

Al₂O₃ - amphoteric

SiO₂ - acidic

P₄O₁₀- acidic

SO₂ - acidic

SO₃ - acidic

acid/base behaviour of sodium oxide

As a strong base, sodium oxide reacts with acids. It reacts with dilute hydrochloric acid to produce sodium chloride solution.

Na2O (s) + 2HCl (aq) → 2NaCl (aq) + H2O (l)

acid/base behaviour of magnesium oxide

Magnesium oxide reacts with warm dilute hydrochloric acid to give magnesium chloride solution. MgO is used in indigestion remedies by neutralizing excess acid in the stomach.

MgO (s) + 2HCl (aq) → MgCl2 (aq) + H2O (l)

acid/base behavior of aluminium oxide

Aluminium oxide contains oxide ions and thus reacts with acids in the same way sodium or magnesium oxides do – to form a salt and water. Aluminium oxide reacts with hot dilute hydrochloric acid to give aluminium chloride solution. Aluminium oxide also reacts with hot, concentrated alkali (NaOH) to form a salt - a colorless solution of sodium aluminate

Al2O3 (s) + 3H2SO4 (aq) → Al2(SO4)3 (aq) + 3H2O (l)

Al2O3 (s) + 2NaOH (aq) + 3H2O (l) → 2NaAl(OH)4 (aq)

acid/base properties of silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide does not react with water and dilute alkali due to the thermodynamic difficulty of breaking up its network covalent structure but it reacts with hot, concentrated sodium hydroxide solution, forming a colorless solution of sodium silicate.

SiO2 (s) + 2NaOH (aq) → Na2SiO3 (aq) + H2O (l)

acid/base properties of phosphorus oxide

Phosphorus(V) oxide reacts with sodium hydroxide to give sodium phosphate , Na3PO4

P4O10 (s) + 12NaOH (aq) → 4Na3PO4(aq) + 6H2O (l)

acid base properties of sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide reacts directly with sodium hydroxide solution. Bubbling sulfur dioxide through sodium hydroxide solution forms sodium sulfite solution.

SO2 (g) + 2NaOH (aq) → Na2SO3 (aq) + H2O (l)

acid/base properties of sulfur trioxide

Sulfur trioxide reacts with sodium hydroxide solution to form sodium sulfate solution.

SO3 (g) + 2NaOH (aq) → Na2SO4(aq) + H2O (l)

acid/base properties of chlorine oxide

Chlorine(VII) oxide reacts directly with sodium hydroxide solution to give a solution of sodium chlorate(VII).

2NaOH (aq)+ Cl2O7 (l) → 2NaClO4 (aq) + H2O(l)

The acidic and basic nature of the Period 3 elements can be explained by looking at their structure, bonding and the Period 3 elements’ electronegativity, write down the relative melting points, type of chemical bonding and structure of each period 3 oxide.

Na₂O – High melting point – Ionic bonding – Giant ionic structure

MgO – High melting point – Ionic bonding – Giant ionic structure

Al₂O₃ – Very high melting point – Ionic (with some covalent character) bonding – Giant ionic structure

SiO₂ – Very high melting point – Covalent bonding – Giant covalent structure

P₄O₁₀ – Low melting point – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure

SO₂ – Low melting point – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure

SO₃ – Low melting point – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure

electronegativity of period 3 elements :

Period 3 element | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Electronegativity | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

Oxygen has an electronegativity value of 3.5

Therefore, the difference in electronegativity between oxygen and Na, Mg and Al is the largest

So, electrons will be transferred to oxygen when forming oxides giving the oxide an ionic binding

The oxides of Si, P and S will share the electrons with the oxygen to form covalently bonded oxides

The giant ionic and giant covalent structured oxides will have high melting pointsas it is difficult to break the structures apart

oxides of Na and Mg in water

The oxides of sodium and magnesium are basic oxides with purely ionic bonding. When they dissolve in water, their oxide ions (O²⁻) react with water molecules to form hydroxide ions (OH⁻), making the solution alkaline.

O2- (aq) + H2O (l) → 2OH- (aq)

oxides of P and S in water

The oxides of P and S which show purely covalent bonding produce acidic solutions with water because when these oxides react with water, they form an acid which donates H+ ions to water

Eg. SO3 reacts with water as follows:

SO3 (g) + H2O (l) → H2SO4 (aq)

The H2SO4 is an acid which will donate a H+ to water:

H2SO4 (aq) + H2O (l) → H3O+ (aq) + HSO4- (aq)

Al and Si oxides in water or acid/base solutions

Aluminum (Al) oxide and Silicon (Si) oxide are insoluble in water, meaning they do not dissolve easily.

When you react them with hot, concentrated alkaline solutions (like sodium hydroxide, NaOH), they behave like acidsin that reaction — even though they are oxides.

Because they behave like acids, they react with the alkali to form a salt.

This kind of behaviour — reacting with bases/alkalis like an acid — is typical of covalently bonded oxides (as opposed to ionic oxides, which usually react with acids).

Al can also react with acidic solutions to form a salt and water. This behaviour is very typical of an ionic bonded metal oxide

This behaviour of Al proves that the chemical bonding in aluminium oxide is not purely ionic nor covalent: it is amphoteric

period 3 hydroxides : sodium hydroxide

NaOH is a strong base and will react with acids to form a salt and water:

NaOH (aq) + HCl (aq) → NaCl (aq) + H2O (l)

magnesium hydroxide

Mg(OH)2 is also a basic compound which is often used in indigestion remedies by neutralising the excess acid in the stomach to relieve pain:

Mg(OH)2 (s) + 2HCl (aq) → MgCl2 (aq) + 2H2O (l)

aluminium hydroxide

Al(OH)3 is amphoteric and can act both as an acid and base:

Al(OH)3 (s) + 3HCl (aq) → AlCl3 (s) + 3H2O (l)

Al(OH)3 (s) + NaOH (aq) → NaAl(OH)4 (aq)

examiner tip - Electronegativity is the power of an element to draw the electrons towards itself in a covalent bond.

For example, in Na2O the oxygen will draw the electrons more strongly towards itself than sodium does.

-

Chlorides of Period 3 elements show characteristic behaviour when added to water which can be explained by looking at their chemical bonding and structure:

NaCl – Ionic bonding – Giant ionic structure – White solid dissolves to form colourless solution – pH 7.0

MgCl₂ — White solid dissolves to form colourless solution (slightly hydrolysed) – pH 6.5

Al₂Cl₆ – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure – Reacts with water giving off white fumes of hydrogen chloride gas – pH 3.0

SiCl₄ – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure – Reacts with water giving off white fumes of hydrogen chloride gas – pH 2.0

PCl₅ – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure – Reacts with water giving off white fumes of hydrogen chloride gas – pH 2.0

SCl₂ – Covalent bonding – Simple molecular structure – Reacts with water giving off white fumes of hydrogen chloride gas and SO2 gas– pH 2.0

As you move from left to right across Period 3, the chlorides change from ionic to covalent in bonding — and this directly affects how they behave in water.

🔹Ionic chlorides(e.g. NaCl, MgCl₂):

Made of ions (e.g. Na⁺ and Cl⁻).

When added to water, they simply dissolve — the ions separate but do not chemically react with the water.

These solutions are:

Neutral if the metal ion (like Na⁺) doesn’t affect water.

Slightly acidic if the metal ion (like Mg²⁺) weakly hydrolyses water and releases some H⁺.

NaCl(s)→Na+(aq)+Cl−(aq)NaCl(s)→Na+(aq)+Cl−(aq)

✅ No hydrolysis, just dissolution.

✅ pH ~7 (NaCl), or ~6 (MgCl₂)

🔹Covalent chlorides(e.g. AlCl₃, SiCl₄, PCl₅):

These are simple covalent molecules, not ionic.

When added to water, they do not just dissolve — they hydrolyse.

💡 What does “hydrolyse in water” mean?

It means the compound reacts chemically with water, breaking bonds and forming new products — often producing hydrogen chloride (HCl), which dissolves in water to form H⁺ ions, making the solution acidic.

describe the trend in bonding and structure of period 3 chlorides

As you move across Period 3 from sodium (Na) to sulfur (S), the type of bonding in their chlorides changes gradually from ionic to covalent.

Sodium (Na) and magnesium (Mg) are metals that are very electropositive (they lose electrons easily), so their chlorides (NaCl, MgCl₂) are mainly ionic.

Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) shows a little bit of covalent character because the Mg²⁺ ion is small and highly charged (high charge density) , so it polarizes (distorts) the electron cloud of the chloride ion a bit, pulling electrons toward itself.

Aluminium (Al), the third element, forms a covalent chloride (AlCl₃) because the small, highly charged Al³⁺ ion strongly polarizes the chloride ions, making the bonds covalent rather than ionic.

Aluminium chloride actually changes form depending on temperature:

At low temperature, it exists as a dimer, Al₂Cl₆ (two AlCl₃ units joined together).

In the gas phase (higher temperature), these dimers break apart into individual electron-deficient AlCl₃ molecules.

Silicon tetrachloride (SiCl₄) is a colourless covalent liquid, meaning it has covalent bonds and exists as molecules.

Phosphorus forms two volatile covalent chlorides:

PCl₃ (phosphorus trichloride) with a boiling point of 76ºC

PCl₅ (phosphorus pentachloride) which sublimes at 161ºC (turns from solid to gas without melting).

how does structure effect the behavior of period 3 chlorides when added to water

Giant ionic structure (like NaCl and MgCl₂):

These compounds consist of a lattice of ions held together by strong ionic bonds.

They tend to dissolve in water by separating into ions, without breaking covalent bonds.

This means NaCl simply dissolves to give neutral solutions, while MgCl₂ can hydrolyze a bit because Mg²⁺ is more polarizing, making the solution slightly acidic. (When MgCl₂ dissolves, Mg²⁺ attracts the lone pairs on water molecules very strongly. This polarises the O–H bonds in water molecules that surround the ion (hydration shell). Because the O–H bonds are weakened, one of the hydrogens can be released as a proton (H⁺))

Simple molecular structure (like Al₂Cl₆, SiCl₄, PCl₅, SCl₂):

These exist as discrete molecules with covalent bonds.

When added to water, these covalent molecules react chemically (hydrolyze) because water can break their covalent bonds, producing acidic products like HCl gas.

Their simple molecular structure means they don’t just dissolve — they chemically change, explaining the acidic fumes and low pH.

how does the chemical bonding of period 3 chlorides affect their behavior in water

Ionic bonding (NaCl, MgCl₂):

The bond is between metal cations and chloride anions.

These compounds dissociate into ions easily when dissolved in water.

NaCl fully dissociates to give neutral solutions because neither ion reacts further.

MgCl₂ dissociates but the Mg²⁺ ion is small and highly charged, so it polarizes water molecules and can hydrolyze, making the solution slightly acidic.

Covalent bonding (Al₂Cl₆, SiCl₄, PCl₅, SCl₂):

Bonds are between non-metal atoms sharing electrons.

These molecules don’t just dissolve; they react chemically with water (hydrolysis) because water can attack and break the covalent bonds.

This produces hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas and acidic solutions, lowering the pH.

ionic vs covalent chlorides in water

Ionic chlorides simply dissolve in water without getting hydrolysed. The ions get hydrated as water molecules surround them. The solution is neutral with pH 7. Covalent chlorides undergo hydrolysis producing acidic solutions with low pH.

sodium and magnesium chloride in water

NaCl and MgCl₂ do not react chemically with water because the polar water molecules are attracted to the positive metal ions and negative chloride ions. This attraction causes the giant ionic lattice to break apart, dissolving the chlorides and forming hydrated metal and chloride ions. As a result, these compounds simply dissociate in water without undergoing hydrolysis. MgCl2, is ionic with degree of covalent character and get hydrolysed to a very little extent. The resulting solution has pH around 6 – 6.5.

NaCl (s)waterNa+(aq)+Cl−(aq)

MgCl2(s)→Mg2+(aq)+2Cl−(aq)

two forms of aluminium chloride

AlCl3 is a giant lattice with ionic bonds (but with strong polarization)

Al2Cl6 is a dimer with covalent bonds

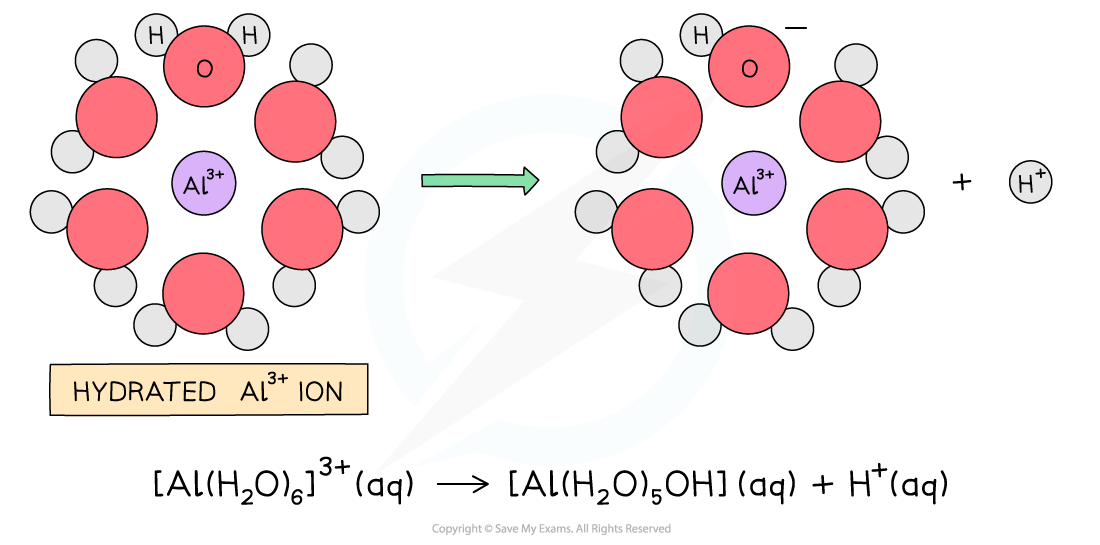

aluminium chloride in water

When aluminium chloride (AlCl₃) is added to water, it does not simply dissolve but instead reacts with the water.Initially, the AlCl₃ dimers (Al₂Cl₆) present in the solid or gaseous form are broken down in water, producing Al³⁺ ions and Cl⁻ ions in solution.

The Al³⁺ ion, which has a high positive charge and a small ionic radius, strongly attracts water molecules. It forms a hexaaquaaluminium complex ion, [Al(H₂O)₆]3+[Al(H₂O)₆]3+, through co-ordinate (dative covalent) bonds where water molecules donate lone pairs to the aluminium ion.

This complex ion is highly polarizing due to the strong positive charge of the Al³⁺ ion. As a result, the electron density in the O–H bonds of the coordinated water molecules is drawn towards the aluminium ion. This causes one of the bonded water molecules to lose a proton (H⁺) in a process called hydrolysis, which occurs stepwise and releases H⁺ ions into the solution, making the solution acidic.

The released H⁺ ions then combine with the Cl⁻ ions from the dissociated aluminium chloride to form hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas, which is observed as white fumes above the solution.

Dissolution and Complex Formation:

AlCl₃ (s) + 6 H₂O (l) → [Al(H₂O)₆]³⁺ (aq) + 3 Cl⁻ (aq)

Hydrolysis:

[Al(H₂O)₆]³⁺ (aq) ⇌ [Al(H₂O)₅(OH)]²⁺ (aq) + H⁺ (aq)

Overall (Combined Reaction):

AlCl₃ (s) + 6 H₂O (l) → [Al(H₂O)₅(OH)]²⁺ (aq) + H⁺ (aq) + 3 Cl⁻ (aq)

silicon chloride in water

When silicon tetrachloride (SiCl₄) reacts with water, it undergoes a rapid and violent hydrolysis reaction, producing solid silicon dioxide (SiO₂) as a white precipitate and releasing white fumes of hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas. The reaction is highly exothermic and can be represented as:

SiCl4 (l) + 2H2O (l) → SiO2 (s) + 4HCl (g)

Some of the hydrogen chloride gas dissolves in water to form an acidic solution.

Silicon tetrachloride also fumes in moist air because it reacts with water vapour present in the atmosphere to produce hydrogen chloride gas.

phosphorus chlorides in water

phosphorus (III) chloride reacts violently with water to generate phosphorus acid, H3PO3, and hydrogen chloride fumes.

PCl3 (l) + 3H2O (l) → H3PO3 (aq) + 3HCl (g)

Phosphorus(V) chloride reacts violently with water (hydrolyzed), producing phosphoric(V) acid and hydrogen chloride fumes.

PCl5 (s) + 4H2O (l) → H3PO4 (aq) + 5HCl (g)

Both H3PO4 and dissolved HCl are highly acidic

disulfur dichloride in water

Disulfur dichloride (S2Cl2) reacts slowly with water to produce a complex mixture of hydrochloric acid, sulfur, hydrogen sulfide and various sulfur-containing acids and anions.

electronegativity and its variation across a period

the power of an element to draw the electrons towards itself in a covalent bond. it increases across a period.

why does electronegativity increase across period 3 from Na to Cl

As the atomic number increases going across the period, there is an increase in nuclear charge

Across the period, there is an increase in the number of valence electrons however the shielding is still the same as each extra electron enters the same shell

As a result of this, electrons will be more strongly attracted to the nucleus causing an increase in electronegativity across the period

bonding and structure of period 3 elements

As you move across the Periodic Table from aluminium (Al) to sulfur (S), both bonding and structure change:

Bonding changes from metallic (in Al) to covalent (in Si, P, S, etc.)

Structure changes from giant lattices to simple molecular structures

Na - metallic bonding, giant metallic structure

Mg - metallic bonding, giant metallic structure

Al - metallic bonding, giant metallic structure

Si - covalent bonding, giant molecular structure

P - covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

S - covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

Cl - covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

Ar - simple molecular structure

bonding and structure from Na to Al

Sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), and aluminium (Al) are all metals

They form a giant metallic lattice:

Positive metal ions are arranged in a regular lattice

They are surrounded by a ‘sea’ of delocalised electrons

These electrons come from the outer shell (valence shell) of each atom

delocalized electrons and bond strength from Na to Al

Na donates 1 electron per atom

Mg donates 2 electrons per atom

Al donates 3 electrons per atom

As a result:

More delocalised electrons = stronger electrostatic forces between the metal ions and the electron cloud

Al³⁺ forms stronger metallic bonds than Na⁺, due to:

Higher ionic charge

Greater number of delocalised electrons

electrical conductivity from Na to Al

Because aluminium contributes more delocalised electrons, it has:

More charge carriers

Stronger metallic bonding (Stronger bonding pulls positive ions closer together → denser structure. A denser lattice means electrons can move more easily between ions, reducing resistance.)

Therefore, aluminium is a better conductor of electricity than sodium or magnesium

bonding and structure of silicon

Silicon (Si) is a non-metallic element that forms a giant molecular (giant covalent) structure. In this structure, each silicon atom is covalently bonded to four neighbouring silicon atoms in a three-dimensional network. These strong covalent bonds hold the atoms firmly in place, giving silicon a high melting point and great hardness.

Unlike metals, silicon does not have delocalised electrons within its giant covalent lattice. Because of this absence of free electrons, silicon cannot conduct electricity well under normal conditions.

Due to its intermediate properties—such as its semiconductor behaviour and its position between metals and non-metals in the periodic table—silicon is classified as a metalloid.

bonding from P to Ar

Phosphorous, sulfur, chlorine and argon are non-metallic elements

Phosphorous, sulfur and chlorine exist as simple molecules (P4 , S8 , Cl2)

Argon exists as single atoms

The covalent bonds within the molecules (intramolecular) are strong, however, between the molecules (intermolecular) there are only weak instantaneous dipole-induced dipole forces

It doesn’t take much energy to break these intermolecular forces which is why these substances generally have low melting and boiling points.

The lack of delocalised electrons means that these compounds cannot conduct electricity

bonding and structure of period 3 chlorides

NaCl

Ionic bonding, giant ionic structure

MgCl₂

Ionic bonding, giant ionic structure

Al₂Cl₆

Covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

SiCl₄

Covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

PCl₅

Covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

SCl₂

Covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

chemical bonding and structure of period 3 oxides

Na₂O

Ionic bonding, giant ionic structure

MgO

Ionic bonding, giant ionic structure

Al₂O₃

Mainly ionic bonding with some covalent character, giant ionic structure

SiO₂

Covalent bonding, giant covalent structure

P₄O₁₀

Covalent bonding, simple molecular structure

SO₂ and SO₃

Covalent bonding, simple molecular structures

general description of trend of period 3 chlorides and oxides + their reactions with water

Going across Period 3, their chlorides and oxides become more covalent and their structure shifts from a giant ionic to a simple molecular structure

Their reactions with water become more vigorous as a result of this, as it becomes easier to hydrolyse the chlorides and oxides

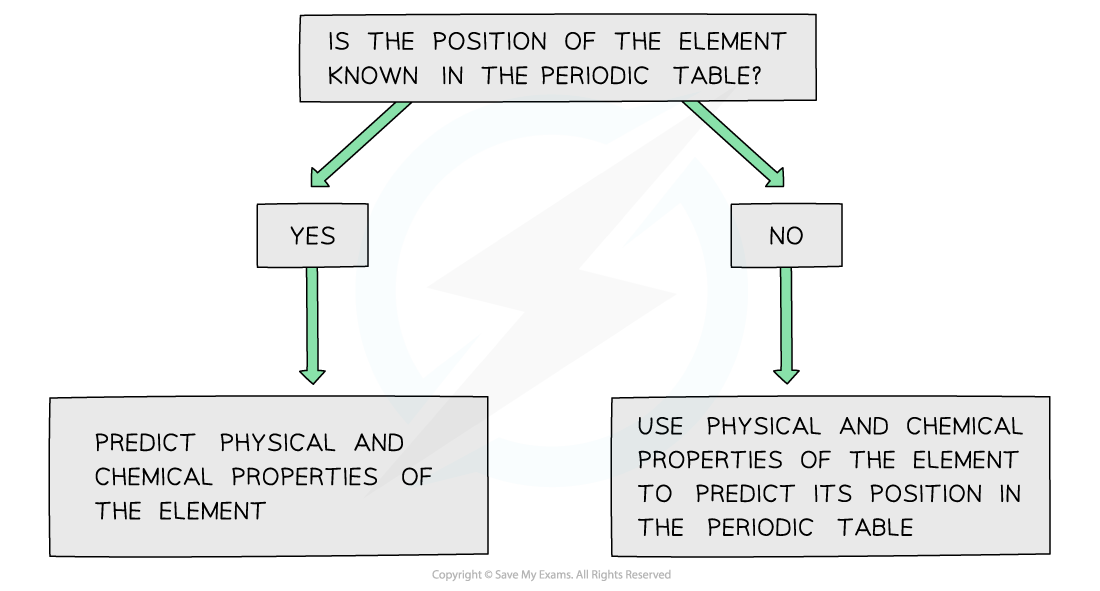

periodicity - predicting position and properties

If the chemical and physical properties of an element are known, the position of that element in the Periodic Table can be predicted

Similarly, predictions can be made about the physical and chemical properties of elements if the position of the element in the Periodic Table is known

white vs red phosphorus

🔹 White phosphorus (P₄)

Structure: Exists as discrete P₄ tetrahedral molecules.

Bonding: Each P atom forms 3 bonds, leaving strained 60° bond angles (very unstable).

Appearance: Waxy, white/yellow solid.

Reactivity:

Very reactive because of the strained bonds.

Ignites spontaneously in air → stored under water to prevent contact with oxygen.

Poisonous.

Uses: Manufacture of phosphoric acid, incendiary bombs, flares.

🔹 Red phosphorus

Structure: A polymeric network (chains of linked P atoms).

Bonding: No severe bond strain (bond angles closer to normal).

Appearance: Dark red solid.

Reactivity:

Much less reactive than white phosphorus.

Does not ignite in air at room temp.

Non-toxic (relative to white P).

Uses: Safety matches (on the striking surface), fireworks, pyrotechnics.

✅ Summary:

White P → molecular, unstable, reactive, toxic, stored under water.

Red P → giant covalent-like network, stable, safe, used in matches.

ceramics

Ceramic materials are crystalline oxides, nitrides and carbides.

Ceramic materials are solid, and regardless of whether the bonds are ionic or covalent, giant lattice structures are formed.

Giant lattice structures have high melting and boiling points because strong ionic or covalent bonds must be broken in order to separate individual compounds.

Giant lattice structures also do not conduct electricity when in the solid state because there are no mobile ions or electrons to carry an electrical charge.