Cancer Biology UARK Exam 1 (With bonus questions)

1/68

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Yuuchun Du

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

69 Terms

Cellular definition of Cancer is

a group of diseases in which abnormal cells proliferate without control and can invade nearby tissues.

Genetic definition of Cancer is

a type of genetic diseases, resulting from mutations.

Major sources of gene mutations:

➢ DNA replication

➢ Endogenous cellular biochemical factors

➢ Exogenous factors (carcinogens)

A tumor is:

An abnormal mass of tissue formed by an abnormal

growth of cells: benign or malignant; multicellular

Cancer is:

Malignant; single cell or multicellular

Classification of tumors

Primary tumor, Metastasis, Benign, Malignant

(Neolplasm=Tumor; neoplasia, new growth)

Primary tumor:

The original tumor

Metastasis:

Formed by cancer cells that have

spread from other part of the body

Benign tumor:

Grow locally without invading adjacent tissues

Malignant:

What type of tumor has invaded nearby tissues

Cancer classification, carcinomas:

Squamous cell carcinomas and Adenocarcinomas make up 80%

Cancer classification, Non-epithelial cancers:

Sarcomas: 1%, Leukemia/Lymphomas: 7%, Neuroectodermal tumors: 2.5%

Carcinomas:

Derive from epithelial cells; responsible for >80% the cancer-related deaths.

-Squamous cell carcinomas: From protective epithelial cells

-Adenocarcinomas: From secretory epithelial cells

Sarcomas:

Derive from mesenchymal cells; responsible for

~1% of tumors in the clinic

Leukemia/Lymphomas:

Derive from blood-forming

(hematopoietic) cells; responsible for ~7% of cancer-related

death.

Neuroectodermal tumors:

Derive from nervous system;

responsible for ~2.5% of cancer-related death.

The journey to malignancy:

1. Normal: normal appearance, normal division, and normal assembly

2. Hyperplasia: normal appearance, abnormal division, and normal assembly

3. Metaplasia: normal appearance, normal division, and abnormal assembly

4. Dysplasia: abnormal appearance, abnormal division, and abnormal assembly

5. Locally invasive tumors: abnormal appearance, abnormal division, abnormal assembly, and invasion to adjacent tissues

6. Metastases: abnormal appearance, abnormal division, abnormal assembly, invasion to adjacent tissues, and spread to other organs

5 hows of cancer:

➢ Tumors seem to develop progressively.

➢ Tumors are monoclonal growth.

➢ Cancer cells exhibit an altered energy metabolism.

➢ Specific physical, chemical, or viral agents induce cancers.

➢ The great majority of the commonly occurring cancers are caused by environmental factors.

Warburg effect:

The observation that most cancer cells obtain their energy from glycolysis, even in the presence of abundant O2

Cancer-causing agents are:

physical, chemical, or viral agents

Carcinogens vs. mutagens rule

➢ All mutagens are carcinogens

➢ Not all carcinogens are mutagens

Factors that contribute to cancer development:

-Heredity.

-Environment

Incidence rates:

The rates with which the disease is diagnosed. Cancer incidence rates are dramatically different among different populations.

The great majority of the commonly occurring

cancers are caused by

environment factors

- Physical environment: air, water, sunlight, etc

- Lifestyle: dietary choices, reproductive habits, tobacco usage, etc.

Basics of viruses

➢ A sub-microscopic infectious agent

(10-300 nm in diameter).

➢ Unable to grow or reproduce outside

a host cell (bacteria, plants, or animals).

➢ Structure: genome (DNA or RNA)

wrapped in a protein coat (capsid)

Anchorage independence:

Cells grow without attachment to the

solid substrate.

Tumorigenicity:

The ability of cultured cells to give rise to either benign

or malignant progressively growing tumors in in immunologically

nonresponsive animals.

Provirus:

The DNA version of the viral genome.

Retrovirus:

A single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus

with a DNA intermediate in the host cells.

Oncogene:

A gene capable of transforming a normal

cell into a tumor cell

Proto-oncogene:

The precursor of an active oncogene

what do the terms mean: src, c-src: , v-src

src is an additional gene found in RSV. cellular src , viral src

Why was the discovery of c-src gene a milestone in cancer research

➢ The concept of proto-oncogene implied that:

— the genomes of normal cells carry genes that have the potential to induce cancer.

— Other tumor viruses may convert other proto-oncogenes into oncogenes using a similar mechanism.

— The proto-oncogene can be activated by other mechanisms than virus

➢ There might be many more other proto-oncogenes.

➢ c-src is the first proto-oncogene discovered.

Insertional mutagenesis:

Activation of cellular proto-oncogene by inserting provirus near the proto-oncogene

Three types of retroviruses that induce cancers

➢ Carry no oncogenes [e.g., avian leukosis virus (ALV)]; induce cancers slowly (weeks to months) through insertional mutagenesis.

➢ Carry acquired oncogenes [e.g., Rous sarcoma virus (RSV)]; induce cancers rapidly (days to weeks)

➢ Carry endogenous viral oncogenes [e.g., human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-I)]

Tumor viruses are generally either

➢ DNA viruses [e.g.,SV-40]

➢ Retroviruses

Molecular mechanisms of

proto-oncogene activation

➢ ras

➢ myc

➢ HMGA2

➢ EGF-R

➢ bcr-abl

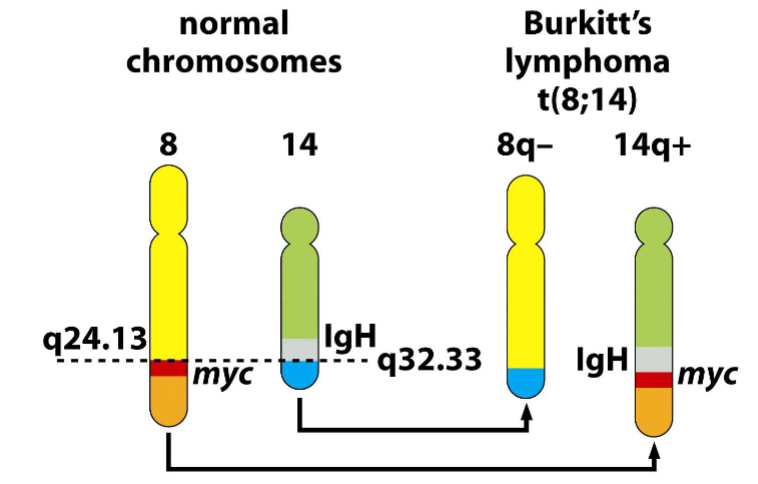

Three alternate ways of activating the c-myc proto-oncogene:

Provirus Integration

Gene amplification

Chromosomal translocation

Gene amplification:

The production of multiple copies

of a particular gene or genes

-does not always result in over-expression of the gene.

Amplicon:

The region of chromosome DNA that undergoes amplification.

-may be a long stretch of DNA (0.5–10 MB)

and becomes visible in metaphase through light

microscope

myc amplification

➢ FISH: Fluorescence in situ hybridization.

➢ N-myc amplification (10-150 copies) is responsible for 40% of advanced pediatric neuroblastomas

Kaplan-Meier plot:

The percentage of patients surviving is plotted as a

function of the time after initial diagnosis or treatment.

Burkitt’s lymphoma

-Chromosomal translocations

-chromosome translocation in Burkitt's lymphomas

places c-myc gene under control of the IgH sequence

➢ IgH: immunoglobulin heavy-chain; IgH sequence direct high, constitutive expression

-related to malarial and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection

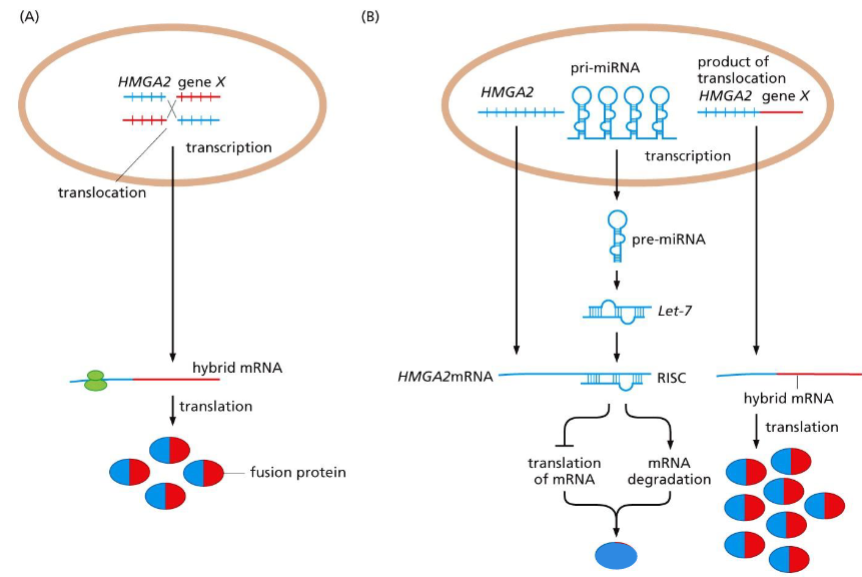

HMGA2 pro-oncogene activation:

-Translocations liberating an mRNA from miRNA regulation

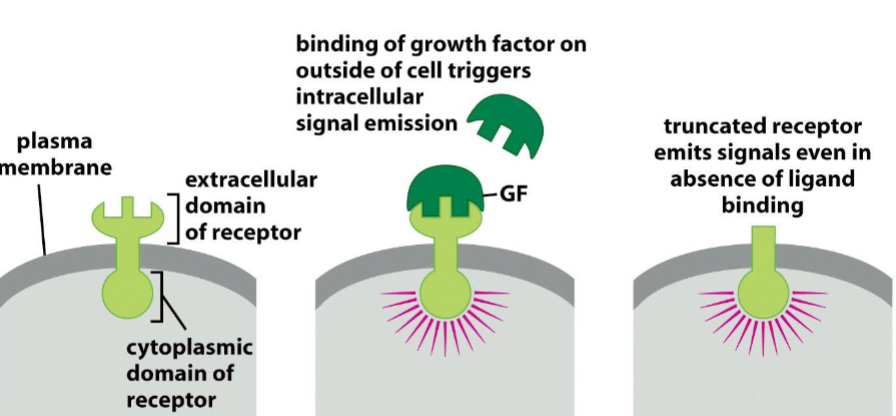

Deregulated firing of growth factor receptors:

truncated (decapitated) receptor emits signals even in absence of ligand binding

Proto-oncogene overexpression:

— Gene amplification: cMyc

— Expression under strong promoter: cMyc

— Escaping from miRNA regulation: HMGA2

Changes of proto-oncoprotein structure:

— Point mutation: Ras

— Truncation: EGF-R

— Creation of fusion oncoprotein: Bcr-Abl

What types of observation allow a pathologist to identify the tissue of origin of a tumor?

Tissue of origin can be identified by location, histologic architecture, cellular morphology, immunohistochemical staining, and molecular signatures

Why are certain tumors extremely difficult to assign to a specific tissue of origin?

Tumors become hard to classify when they are poorly differentiated (anaplasia), share overlapping features, or lose lineage markers, leaving few clues about their origin

Under certain circumstances, all tumors of a class can be traced to a specific embryonic cell layer, while in other classes of tumors, no such association can be made. What tumors would fit into each of these two groupings.

Fixed embryonic lineage: Carcinomas (ecto-/endoderm), sarcomas and hematopoietic tumors (mesoderm).

Not assignable: Germ cell tumors (pluripotent origin) and some undifferentiated tumors.

What evidence persuades that a cancer arises from the native tissues of an individual rather than invading the body from outside and thus being of foreign origin.

Evidence from genetic identity, tissue continuity, immunology, and transplantation experiments shows that cancers are derived from the native cells of the host (genetically host-specific). They are not foreign invaders, but corrupted versions of the body’s own tissues.

How compelling are the arguments for the monoclonality of a tumor cell populations, and what logic and observations undermine the conclusion of monoclonality.

The most compelling evidence (X-inactivation, Ig/TCR rearrangements, shared chromosomal abnormalities) strongly supports that tumors are monoclonal in origin.

However, tumors do not remain monoclonal. With time, mutations, selection pressures, and clonal evolution generate polyclonal heterogeneity.

In some settings (heavy mutagen exposure, field cancerization, or clonal cooperation), there may even be truly polyclonal origins.

How can we estimate what percentage of cancers in a population are avoidable (through virtuous lifestyles) and what percentage occur independently of lifestyle.

We estimate the fraction of avoidable cancers through epidemiological comparisons, attributable risk calculations, and twin/familial studies. Current consensus: about half of cancers could be prevented with lifestyle and public health measures, while the other half occur due to intrinsic aging and random mutation processes.

What limitations does the Ames test have in predicting the carcinogenicity of various agents.

The Ames test is sensitive for mutagens (especially point mutations/reversions) but limited because not all carcinogens are mutagens, not all mutagens are carcinogens, and bacterial metabolism/biology differ from humans.

In absence of being able to directly detect mutant genes within cancer cells, what types of observation allow one to infer that cancer is a disease of mutant cells?

Even without directly sequencing DNA, the following observations can be found:

Consistent chromosomal abnormalities, Clonal origin of tumors, Hereditary cancer patterns, Mutagen/carcinogen correlations, Stable inheritance of malignant traits.

What observations favor or argue against the notion that cancer is an infectious disease?

Some cancers can indeed be initiated by infections (especially viruses). In humans, cancer is not generally an infectious disease, because it lacks person-to-person transmission and is mainly driven by mutations, environment, and aging.

Why are oncogene-bearing viruses like Rous sarcoma virus so rarely encountered in wild populations of chickens.

Oncogene-bearing retroviruses like RSV are rare in wild chicken populations because (1) they’re less fit than normal viruses, (2) they harm hosts too quickly to spread efficiently, and (3) oncogene capture is a rare genetic accident (laboratory controlled).

What evidence suggests that the phenotypes of cells transformed by tumor viruses in vitro reflect comparable phenotypes of tumor cells in vivo?

Parallels in morphology, growth control, metabolism, tumorigenicity, and molecular pathways

Why do retroviruses like avian leukosis virus take so long to induce cancer?

Avian leukosis virus takes a long time to induce cancer because it lacks a viral oncogene and must rely on the rare, random activation of host proto-oncogenes by insertional mutagenesis, followed by additional mutations and clonal expansion.

What evidence suggests that the chromosomal integration of tumor virus genomes is an intrinsic, obligatory part of the replication cycle of RNA tumor viruses but an inadvertent side product of DNA tumor virus replication.

Retroviruses: Integration into host DNA is intrinsic and obligatory — it’s how the virus ensures expression of its genes and propagation of its genome.

DNA tumor viruses: Integration is unintentional. Their normal life cycle doesn’t require it, but when it happens, it can lock in oncogene expression and contribute to transformation.

How can one prove that tumor virus genomes must be present in order to maintain the transformed states of a virus-induced tumor? (Hit and run process?)

Viral DNA/RNA is consistently detectable in every tumor cell.

Key viral transforming genes are continuously expressed.

Inactivation of those genes (via mutation, temperature sensitivity, or immune attack) causes reversion of the transformed phenotype.

Cells infected with viruses lacking those genes fail to transform.

What evidence suggests that a proto-oncogene like c-src is a actually a normal cellular gene rather than a gene that has been inserted into the germ line by an infecting retrovirus?

It exists in the germline DNA of all vertebrates, including uninfected species.

It is expressed in normal cells with important physiological roles.

It is conserved through evolution, independent of retroviral infection.

How do you imagine that Dna tumor viruses and retroviruses like avian leukosis virus arose in the distant evolutionary past?

Retroviruses probably evolved from retrotransposons, occasionally picking up host proto-oncogenes during their replication.

DNA tumor viruses likely evolved from ancient small DNA viruses that learned to subvert cell cycle control to replicate in resting cells.

In both, tumorigenesis is an evolutionary accident. A by-product of their replication strategies, not a purposeful adaptation.

What evidence do we have that suggests that endogenous retrovirus genomes play little if any role in the development of human tumor-associated oncogenes?

Human oncogenes are cellular in origin, not retroviral.

Human endogenous retrovirus (ERVs) are mostly ancient fossils, lacking the mobility and gene capturing functions of active retroviruses in other animals.

While ERVs can occasionally influence gene regulation, they play little or no role in generating the core oncogenes that drive human cancers.

Why might an assay like the transfection focus assay fail to detect certain types of human tumor-associated oncogenes?

Biased toward detecting:

Dominant, single-gene, gain-of-function oncogenes (like mutant RAS).

Tends to miss:

Tumor suppressor genes

Genes requiring cooperation

Genes needing amplification or rearrangements

Oncogenes active only in specific tissues

What molecular mechanisms might cause a certain region of chromosomal DNA to accidentally undergo amplification.

The key routes are (not on the test):

-Breakage–fusion–bridge cycles (HSR staining). Replication fork stalling and misrepair. Episome formation (double minutes) and re-insertion. Genome catastrophes like chromothripsis.

Amplification arises when normal safeguards of replication and repair fail.

How many distinct molecular mechanisms might be responsible for converting a single proto-oncogene into a potent oncogene

(only six bolded necessary)

Point mutation

Gene amplification

Chromosomal translocation (regulatory or fusion)

Insertional Mutagenesis or Viral/transposon insertion

Promoter/enhancer hijacking (myc/IgH)

Epigenetic dysregulation

Abnormal splicing/truncation

Post-translational regulation defects

How many distinct molecular mechanisms might allow for chromosomal translocations to activate proto-oncogenes into oncogenes?

Promoter/enhancer hijacking. Fusion protein. Truncation. Indirect amplification. Abnormal splicing site (Bcr-Abl, fusion of gene)

Since proto-oncogenes represent distinct liabilities for an organism, in that they can incite cancer, why have these genes not been eliminated from the genomes of chordates?

They are indispensable for development, tissue renewal, and survival.

Cancer mainly strikes after reproduction, so the evolutionary penalty is low.

They provide adaptive advantages in healing and immune response.

Organisms evolved tumor suppressors rather than eliminating growth-promoting genes.

They embody Evolutionary compromise, early benefits outweigh late risks.