Unit 3: Implications in the Real World - Criminal Behaviours

1/32

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

33 Terms

Characteristics of Criminal Behaviour

Criminal behaviours cannot be defined by a set of characteristics that fit all.

One thing that all criminal behaviours have in common is that the behaviour has a detrimental or harmful effect (physical, psychological, financial etc) on a victim, and the person committing the crime (the perpetrator) knows that what they are doing is wrong or illegal.

Criminal behaviours are a social construct as they rely on the laws of a society and the social context in which the behaviour takes place.

At any time in history some behaviours may have been deemed as criminal, where as we may not regard them in the same way now. For example, until 1969, homosexuality was illegal in the UK (it still is in some countries e.g. Saudi Arabia).

Additionally, there are occasions when criminal behaviour is morally right. For example, people break the law to highlight a problem with the law, or the social norms of a society in general. E.g. Nelson Mandela

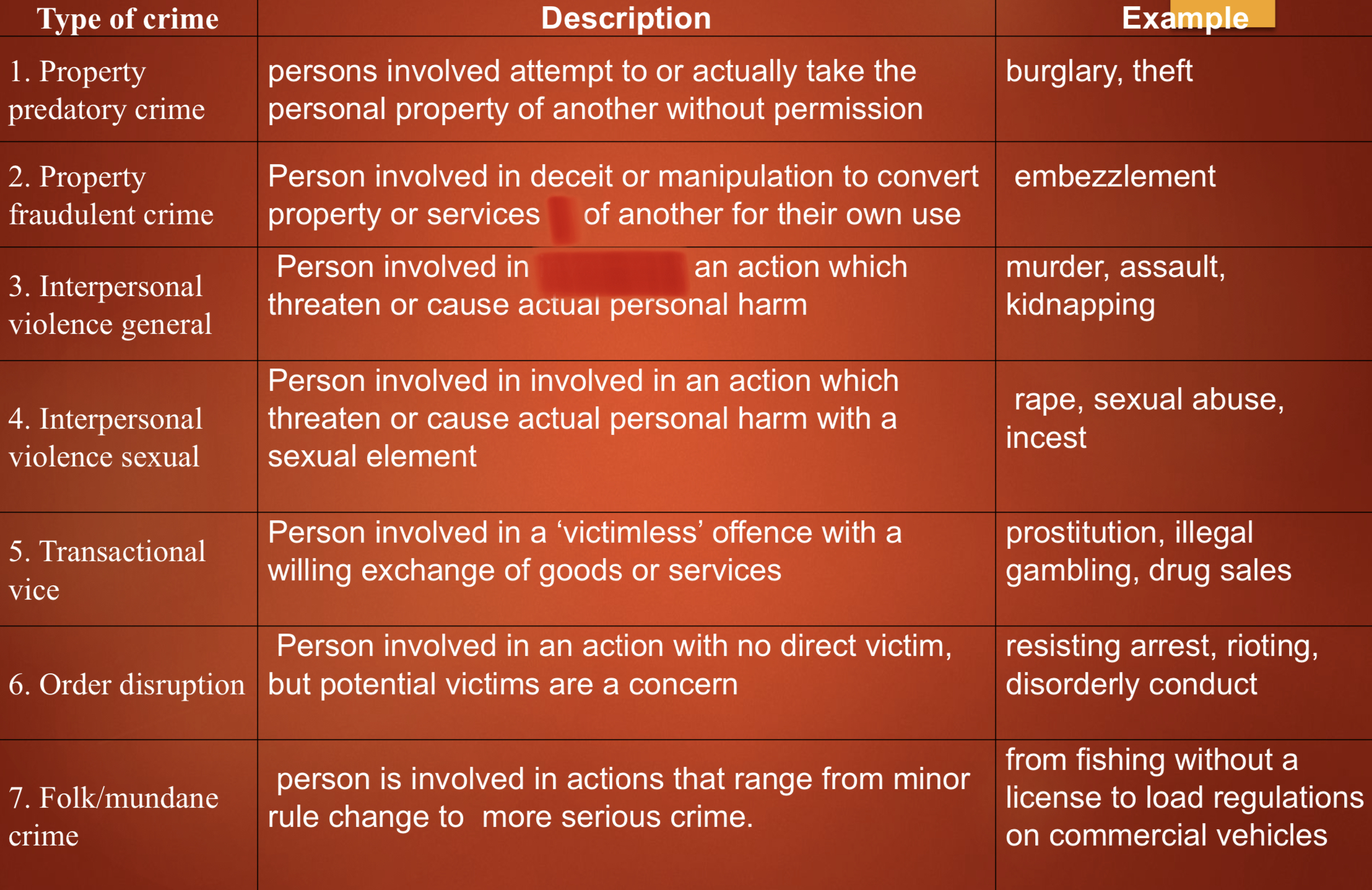

Types of Crime (Farr and Gibbons 1990) & Data on crime

The Office of National Statistics collects and publishes information about the different types and number of instances of criminal behaviour in the UK. It categorises criminal behaviours into two primary offence groups:

Victim based crimes

Crimes against society

Most people consider crimes as those typified in the first group of offence, such as murder or theft. The second group may include drug offences, possession of weapons and are larger in number.

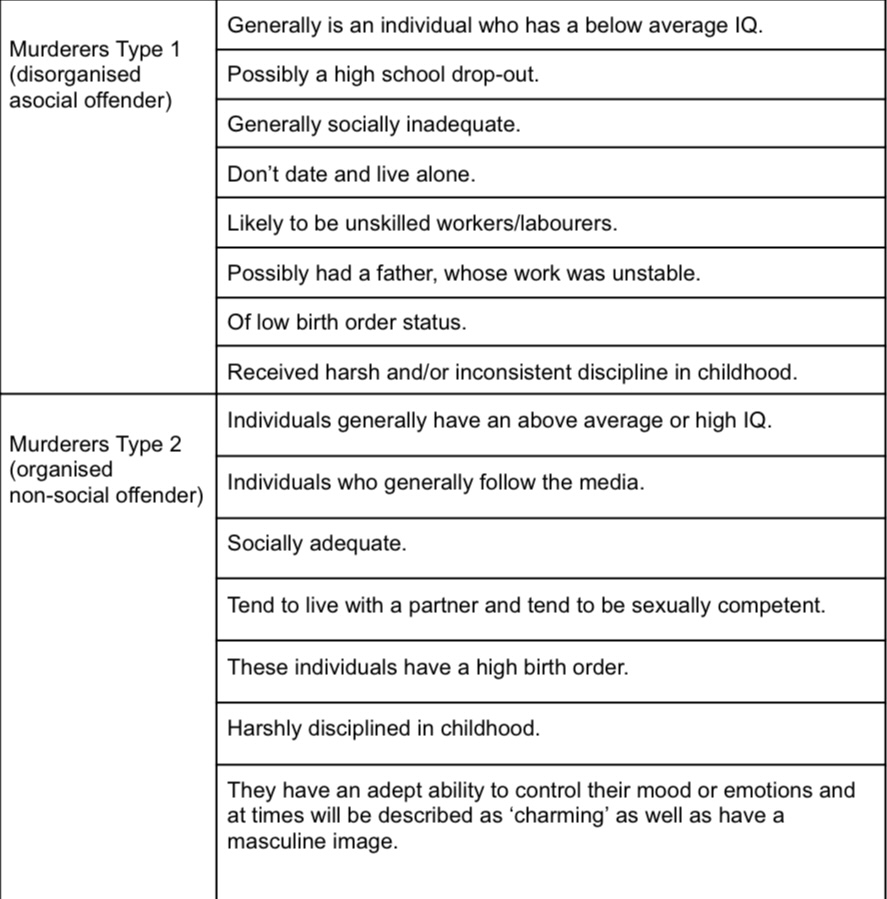

Characteristics of Criminals

Fraud

Fraud is the most common form of criminal behaviour in the UK. In December 2022, The ONS reported that there were 3.7 million fraud cases that year.

Fraud can be perpetrated against individuals, but it can also be perpetrated against organisations, such as companies and charities.

Acquisitive criminals are risk-takers (fraud, burglary, extortion, aggravated burglary and robbery) who generally seek access to criminal activity for pleasure or thrill.

Biological Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - Inherited Criminality (Genetic Factors)

One explanation of criminal behaviour is inherited criminality. In other words, genes are used to explain the causes of criminality and why certain people are criminals, and others aren’t.

Genes are made up of DNA which code for proteins. We inherit half our genes from each parent. Therefore, this theory suggests that some people inherit a biological predisposition to commit crime (Hollin, 1992).

For example, it may be that someone has the gene for impulsivity, thus making them fearless and more likely to commit crime.

Biological Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - Inherited Criminality (Genetic Factors) - Twin Studies

This theory uses a genetic basis to explain criminal behaviour. Thus, twin studies have can be used to look at the concordance rates between MZ (monozygotic: genetically identical) and DZ (dizygotic: share 50% of genes) twins.

Rosanoff (1934) found that MZ twins have a concordance rate of 67% compared to 13% of DZ twins.

The fact that MZ twins, who have identical genes, have a much higher concordance rate than DZ twins who have different genes seems to suggest a genetic basis for crime.

Furthermore, as both sets of twins share an environment, the higher concordance rate of the MZ twins suggests that genes may be the cause.

Biological Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - Inherited Criminality (Genetic Factors) - Family Studies

Family studies look at families with a history of crime and use concordance rates to establish if genes are the cause.

Osborn and West (1979) found 20% of sons of criminal fathers also had criminal records.

As genes are shared within a family, this suggests a genetic explanation.

Biological Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - Inherited Criminality (Genetic Factors) - MAOA Gene

However, it may be that someone may have the gene for the criminal behaviour but it is only expressed as their behaviour if the gene is “switched on”.

This means that having genes that predispose you to criminal behaviour alone is not enough for a person to actually become a criminal.

An environmental trigger, such as abuse or a poor upbringing may cause certain genes that lead to criminal behaviour to be activated.

For example, Capsi et al (2002) found that 12% of men with low MAOA gene (the “warrior” gene, a gene that has been linked with violent and aggressive behaviour) experienced maltreatment as children. These men were responsible for 44% of violent crimes.

Therefore genes combined with other factors such as the environment may be better explanations for criminal behaviour than genes alone.

Evaluation

Biological Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - The role of the amygdala (Sidekick)

The amygdala — a part of the brain involved in fear, aggression and social interactions — is implicated in crime.

The amygdala is a structure in the brain linked to the hypothalamus, the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex as well as other parts of the brain through neural links.

The amygdala takes information from the thalamus and interprets whether it is a threat or not; it produces fear or aggression, the famous ‘fight or flight’ response.

The amygdala is responsible for controlling our emotions and urges, therefore when it malfunctions our ability to control our emotions and urges may be impaired, resulting in behaviour which could be criminal.

Research - Amygdala size

Matthies et al. (2012) scanned the brains of 20 healthy adults and found that those with higher aggression scores had amygdalas 16–18% smaller than less aggressive participants.

This strong negative link suggests that smaller amygdala size may be connected to a naturally more aggressive personality, even in healthy individuals.

Amygdala & Fear Conditioning

Impaired fear processing, dependent on amygdala function can lead to violence because it weakens the natural fear that stops most people from hurting others.

Gao et al (2010) found that 3-year-olds who didn't show normal fear responses later became more likely to commit crimes as adults.

This suggests that reduced amygdala function - which limits fear and caution - can make people more prone to risky, impulsive, and violent behavior.

Evaluation

Individual Differences Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - Eysenck’s Criminal Personality

Eysenck proposed a theory of personality based on biological factors, suggesting that criminal and non-criminal behaviour differs as individuals inherit a type of nervous system that affects their ability to learn and adapt to the environment.

Humans are naturally pleasure-seeking (hedonistic), and theft and violence may be pleasurable to the person doing it, but a conditioned conscience opposes this tendency.

Criminals, according to Eysenck, fail to develop a strong conscience because their nervous system makes them less responsive to conditioning, making them more likely to break societal rules.

Eysenck’s Criminal Personality - 3 Independent Scales

He argued that an individuals’ personality can be measured on three independent scales: Each aspect of personality (extraversion, neuroticism and psychoticism) could be traced back to a different biological cause.

Extraversion-Introversion: An extraverts’ need for constant stimulation and new and dangerous experience, stems from an under-aroused nervous system and is likely to bring them into conflict with the law and they are more likely to carry out criminal activities.

Neuroticism–Stability: Highly neurotic individuals have strong emotional reactions due to a reactive sympathetic nervous system, which can drive habitual behaviours; if these are antisocial, they may lead to criminal activity.

Psychoticism–Normality: High psychoticism involves hostility, cruelty, and lack of empathy, often seen in habitual violent offenders, and is linked to higher testosterone levels that increase impulsive and aggressive tendencies.

Eysenck’s Criminal Personality - Link to criminal behaviour

High neuroticism strengthens the other personality traits, meaning that someone high in neuroticism will be even more extraverted or introverted.

Introverts condition quickly because they are fear-averse, whereas individuals high in both extraversion and neuroticism condition poorly, as they struggle to learn society’s rules and respond ineffectively to punishment, making them more common in criminal populations.

The final dimension, psychoticism, is strongly linked to crime, as high psychoticism involves traits such as aggression, rule breaking, and impulsivity.

Individual Differences Explanations of Criminal Behaviour - Cognitive Factors

Cognitive distortion is a form of irrational thinking whereby the individual’s perception of events is wrong but they think that it is accurate.

Hostile attribution bias refers to what we think when we observe someone’s behaviour and draw a negative inference from it.

As well as errors in attributing the behaviour of others, Gudjonson (1984) developed the Blame Attribution Inventory (BAI) to measure the way in which offenders attribute blame for their own crimes. There are three separate factors:

External attribution: criminals are more likely to blame their criminal behaviour on external factors, such as society their social circumstances, or even blame their victims.

Mental-element attribution: Criminals may blame their crimes on mental illness or a lack of self-control

Guilt-feeling attribution: Feelings of regret or remorse for committing their crimes.

Gudjonsson and Singh (1988) found that sex offenders were more likely to experience guilt-feeling attributions, while violent offenders were more likely to demonstrate mental-element attributions.

Cognitive Factors - Minimalisation & ToM

Other cognitive distortions include minimalisation, which suggests that a criminal, may under exaggerate the negative interpretation of their crime, which helps them accept the consequences of their own behaviour and means that negative emotions can be reduced.

Spenser et al (2015) found that a lack of pro-social skills is characteristic of an antisocial or offending personality.

It is therefore reasonable to assume that an inadequate understanding of another's mental state, caused by a poorly functioning theory of mind may contribute to antisocial or offending behaviour.

Social Psychological Explanation: Differential Association Theory (Superhero)

Differential association theory (DA) was first proposed by Sutherland (1939) suggesting that criminal behaviour came from how a person was socialised.

The term “differential association” refers to the fact that people vary the frequency with which they socialise with various groups.

If someone was socialised around many people who held pro- crime attitudes, they would accept these attitudes as the norm and would then take on these same attitudes and views. This socialisation, he argued, comes mainly from the family environment and peer groups.

The individual will also learn about which types of crime are considered to be acceptable.

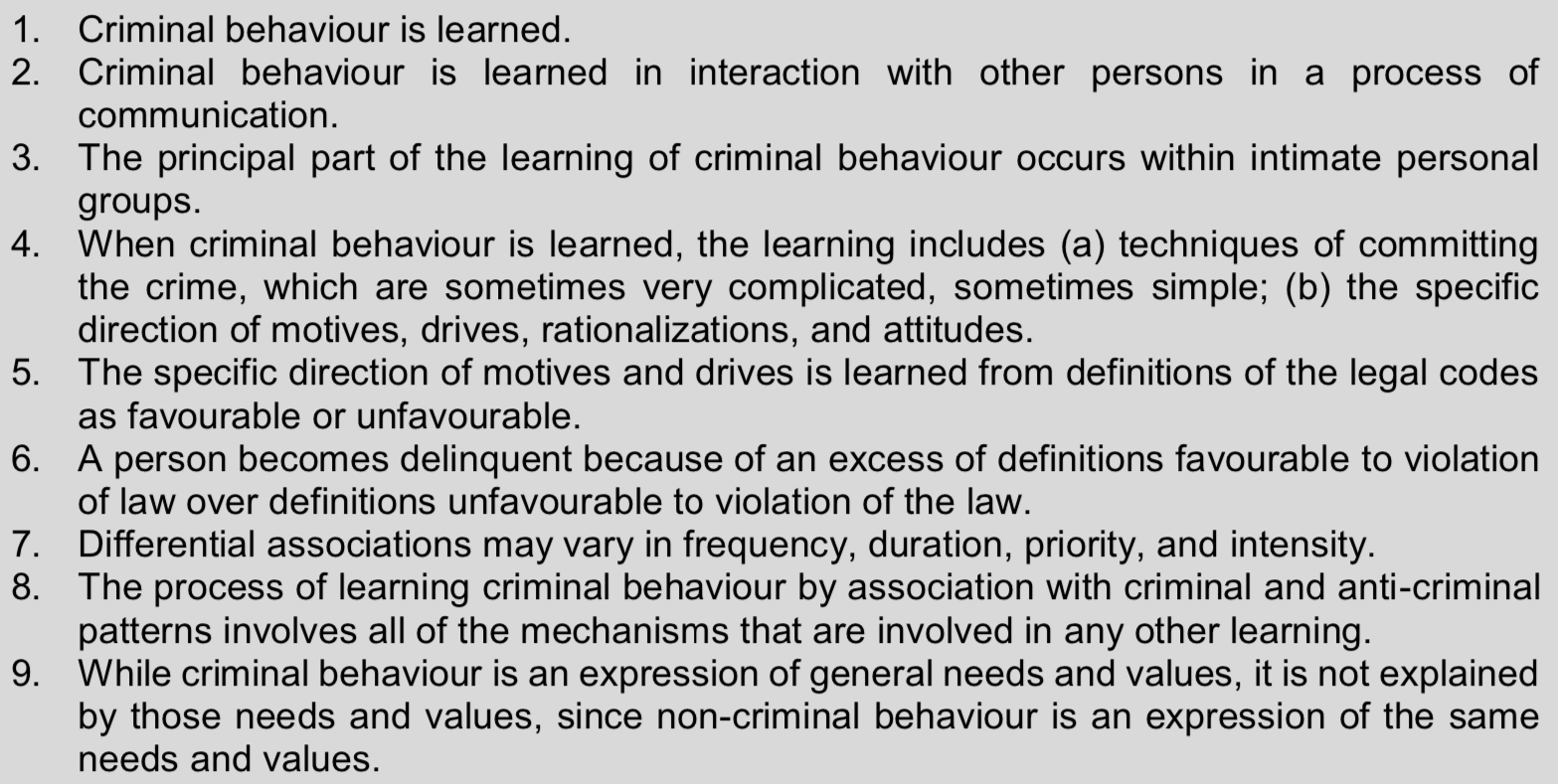

Differential Association Theory: 9 Key Principles

Sutherland’s (1939) Differential Association Theory gives priority to the power of social influences and learning experiences and can be expressed in terms of 9 key principles to explain DA. These can be summarised:

Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory argues that criminal behaviour is learned through interaction and communication with others, primarily within intimate personal groups.

This learning includes both the techniques of committing crime and the motives, drives, rationalisations and attitudes associated with offending. Individuals learn definitions of the law as favourable or unfavourable, and a person becomes delinquent when there is an excess of definitions favourable to violation of the law.

Differential associations vary in frequency, duration, priority and intensity, and the learning process involves the same mechanisms as any other learning. Although criminal behaviour expresses general needs and values, it is not explained by them, as non-criminal behaviour reflects the same needs and values.

Differential Association Theory: The process of learning

As for the actual process by which the learning occurs, Sutherland suggested that degree of influence is determined by the frequency, length and meaningfulness of the interactions.

In other words, those that have the greatest influence on criminals are those who they see the most often (frequency) with which they spend the most time (length), and where the interaction is significant (meaningfulness).

Therefore, it is easy to see how parents, family and peer groups have the biggest effect as they meet all three criteria. Learning may also takes place through the usual methods of operant conditioning and social learning from role models.

Sutherland emphasised that DA Theory applies to privileged groups as well, arguing that white-collar and organisational crime is shaped by the values of an individual’s immediate social circle; because communities support both criminal and non-criminal behaviour, it is the specific social networks people belong to that distinguish offenders from conformists.

Evaluation of DA Theory

Deterministic - Sutherland (1939) - reduces stigma as doesn’t place blame inside criminal (social influences), interventions can be put in place.

Reductionist - Ignores biological factors. Rosanoff (1934) 67% MZ Twins & 13% of DZ Twins.

Application - Disengagement and Distraction Activites (Method of Modifying)

Cause and Effect - Data collected is correlational (criminals may seek out other criminals as peers)

Social Psychological Explanation: Gender Socialisation (Sidekick)

Sutherland (1949) argues that the different patterns of socialisation experienced by boys and girls reinforces behaviour that may encourage criminality in boys, and discourage in it girls, as boys are encouraged to be tough risk takers, while girls are not. Sex role theory suggests that this results in boys becoming more delinquent.

One explanation for the infrequency of female criminality is that girls are socialised to conform, are more strictly supervised by their parents and are shown greater disapproval for breaking societal rules than boys (Hagan et al 1979).

Furthermore, Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977) suggests that people—especially children—learn behaviours by observing and imitating older role models who are usually similar to them.

As a result, gendered behaviour is largely learned from parents, with boys tending to imitate their fathers and girls their mothers.

Albert Cohen (1995) argues that although access to the role model is easy for girls, it is more difficult for boys as their father is traditionally less accessible, therefore, boys are more likely to rebel against the socialisation offered by their mother.

Boys pursue opportunities to express their masculinity, seeking all male peer groups that reward masculine behaviours such as aggression, toughness and rule breaking which may lead to criminal behaviour.

Gender Socialisation: Crime rates for women

Women are mainly law abiding. They are convicted of fewer crimes across the world as research suggests that 80% of crimes are committed by men (Heidensohn 1991).

As adults, women have fewer opportunities to commit crime because of domestic restrictions such as housework and childcare.

Carlen (1990) argues that women’s crimes are typically “crimes of the powerless,” often linked to poverty or control by male partners. Carlen found that women often commit crime as a rational response to difficult circumstances.

During interviews, many women stated that they turned to crime because low-paid work, unemployment, and unhappy family lives left them feeling unrewarded and powerless, making crime seem like a practical alternative.

Evaluation of Gender Socialisation

Deterministic - Hagan et al (1979)

Reductionist - Bandura (1977) - Ignores biological factors, higher testosterone levels in males leads to aggression.

Cause and effect - Carlen (1990) - many women do commit crimes despite socialisation, therefore we cannot be sure socialisation causes criminality

Application - Cohen (1995) preventative measures, providing boys with positive male role models, addressing domestic control for women

Methods of Modifying Behaviour: Anger Management

Anger management programmes are one of the cognitive behavioural therapies that have been widely used with offenders.

They are based on the assumption that anger is a primary cause of violent criminal acts and that learning to control this will reduce bad behaviour in prisons and rates of re-offending.

Anger management as a treatment for crime has two main aims. Firstly, it aims to reduce rates of recidivism.

If anger can be controlled, and its effects limited, then offenders who are prone to angry outbursts may be able to reduce the likelihood that their anger causes them to engage in criminal (most often, violent) behaviour.

A second aim of anger management is to reduce the levels of anger and aggression in the short term, in particular in prisons.

Novaco (2013) refers to prisons as “anger factories”. This approach aims to change the way that the person handles anger and aggression.

The situation may not change, but the person should be able to change the way they think about it, and thus change their behaviour.

Anger Management: Stress Inoculation

The main aim of anger management is to equip individuals with skills to cope with stressful and anger-provoking situations.

Stress inoculation acts like a form of “vaccination” against anger, helping individuals to manage their reactions when faced with anger-triggering situations and reducing the likelihood of angry behaviour. This approach is most commonly used with offenders in prison or on parole, particularly those with a history of angry outbursts.

Ainsworth (2000) suggests that stress inoculation should be delivered in group sessions with offenders and should involve three stages:

Cognitive preparation – individuals are encouraged to think about their own patterns of anger and consider the effects of their anger.

Skill acquisition – individuals learn more effective ways of dealing with anger and anger-provoking situations. These include:

Cognitive skills, such as rehearsing thoughts about controlling anger (e.g. “I must not allow myself to get angry”).

Behavioural skills, such as relaxation techniques and assertiveness training, which involve expressing feelings calmly and effectively without aggression.

Application practice – individuals practise these skills through role-play to prepare them for real-life situations.

Anger Management: CALM

Another variation of anger management is the Controlling Anger and Learning to Manage it (CALM).

This is often used in prisons, and is designed for male offenders (Keen 2000). This anger management course is used within a young offenders’ institution, conducted with male offenders aged between 17 and 21 years. The aims of the course are to:

Increase offender awareness of the process by which they become angry

Raise awareness of the need to monitor their own behaviour

Educate in the benefits of controlling anger

Improve techniques for controlling anger

Practice anger management techniques in role play

The course involved eight two hour sessions, the first seven over a 2-3 week period, with the last session a month later.

Course members were asked to keep a diary detailing their experiences of anger and the way they handled it – this was used as the basis for questioning and challenging individual thought processes that led to feelings of anger.

Evaluation of Effectiveness of Anger Management: Ainsworth (2000) - Strength

One strength of anger management is that it can be effective when used appropriately. Ainsworth (2000) argues that anger management works best when it is properly managed, well resourced and targeted at offenders whose crimes are linked to poor anger control.

This suggests it can successfully reduce offending by addressing the root cause of behaviour rather than treating all offenders the same.

For example, offenders who commit impulsive or violent crimes linked to anger are more likely to benefit from cognitive preparation, skill acquisition and application practice, as these directly target their anger triggers and responses.

Therefore, anger management has practical value as a rehabilitation method which can reduce reoffending when applied to the right offenders.

Evaluation of Effectiveness of Anger Management: Howitt (2009) - Weakness

In some cases, anger management may have the inverse effect on offenders, causing higher levels of violent and aggressive behaviour.

Howitt (2009) points out that some offenders act violently not out of anger but to achieve specific goals. Such individuals are unlikely to benefit from anger management, and there are circumstances under which treatment may be counterproductive.

Anecdotally, there have been offenders who have learned how to better control their anger through anger management, and have therefore prevented themselves from flying into a rage and hurting another person there and then.

However, rather than this being the end of the incident, the offender will wait until there are no witnesses, and then will attack the individual. Anger management may give offenders the skills to become better at evading capture, increasing reoffending rates.

Evaluation of Effectiveness of Anger Management: Hunter (1993) - Strength

One strength of anger management is evidence showing it leads to positive behavioural changes.

Hunter (1993) reported considerable improvements in offenders who took part in anger management programmes, including reductions in impulsiveness, depression and interpersonal problems.

This suggests that anger management does not only reduce anger but also improves emotional control and social functioning.

Therefore, this supports the effectiveness of anger management as it helps offenders develop skills that may reduce the likelihood of future offending, increasing its value as a rehabilitation technique.

Evaluation of Effectiveness of Anger Management: Gender Bias - Weakness

One weakness of anger management is that it could be argued to be sexist. Most anger management schemes are designed for male offenders, and nearly all research into their effectiveness has been carried out on men, such as Hunter (1993) whose sample consisted mainly of male offenders.

On one hand, this suggests that anger management reflects the fact that men commit the majority of violent crime and are generally more aggressive.

However, this creates limited treatment options for female offenders whose crimes may also originate in anger, as the causes and treatment of women’s anger may differ from men’s.

Therefore, traditional male-focused anger management programmes may be an inappropriate and less effective treatment choice for women.

Ethical Issues of Anger Management: