art history final exam fall 2025

1/29

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

30 Terms

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz

El Greco

mannerism

Oil on canvas

15 ft. 9 in. × 11 ft. 9¾ in

he studied the paintings of Tintoretto which are characterized by loose brushstrokes and bold contrasts between light and dark

Trained in icon painting on the island of Crete where artists continued to work in the Greek Orthodox, post-Byzantine style of more abstract, symbolic religious imagery

he moved to Toledo in Spain, where he worked on religious commissions until his death

El Greco’s eclectic style features elongated figures and compressed space consistent with Mannerism

The painting is curved at the top to fit onto the vaulted chapel wall

chapel is dedicated to the virgin mary

an earthly realm divides by a row of heads from a heavenly realm just above

the prophet John the Baptist kneels and gestures to the Virgin Mary

Christ hovers above the pair, wearing a loosely painted white robe that blends into the surrounding clouds, which are made from swirling heavenly angels and figures.

Above the body of the Count, an angel wearing a yellow robe carries the count’s soul into heaven, connecting the natural and the supernatural realms.

The space and the crowded figures, which are elongated beyond anatomical realism, are compressed to bring earth and heaven together, while the loose brushstrokes lend a sense of immediacy to the painting and its monumental size impresses the viewer

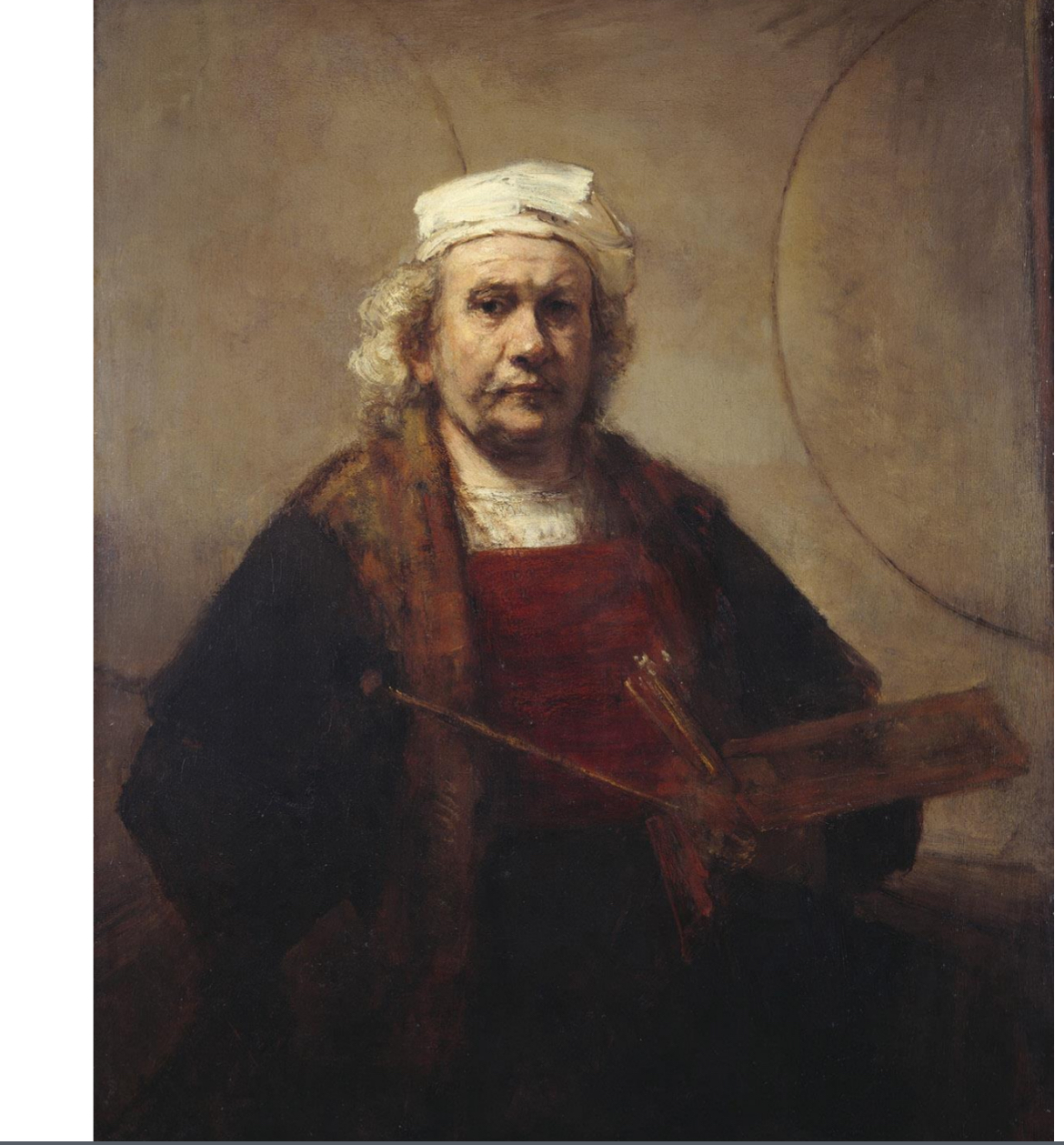

Self-Portrait with Two Circles

Rembrandt van Rijn

Dutch Baroque

Oil on canvas

44⅞ × 37 in

Darkly contemplative self-portrait, reveals his professional self-image with a striking depth of feeling

The sketchy, unfinished quality of the brushwork is a significant aspect of the painting

Variations in the texture and color of the paint around Rembrandt’s face encourage the viewer to scrutinize the work closely — this puts the artist’s image and the viewer in close proximity

This creates an intimate relationship between artist and viewer

He is framed by half of two circles

The tone, texture, and stripes to the circles have been interpreted as depicting the surface of a hung canvas

Could also be interpreted as showing off artistic genius by freehanding a perfect circle

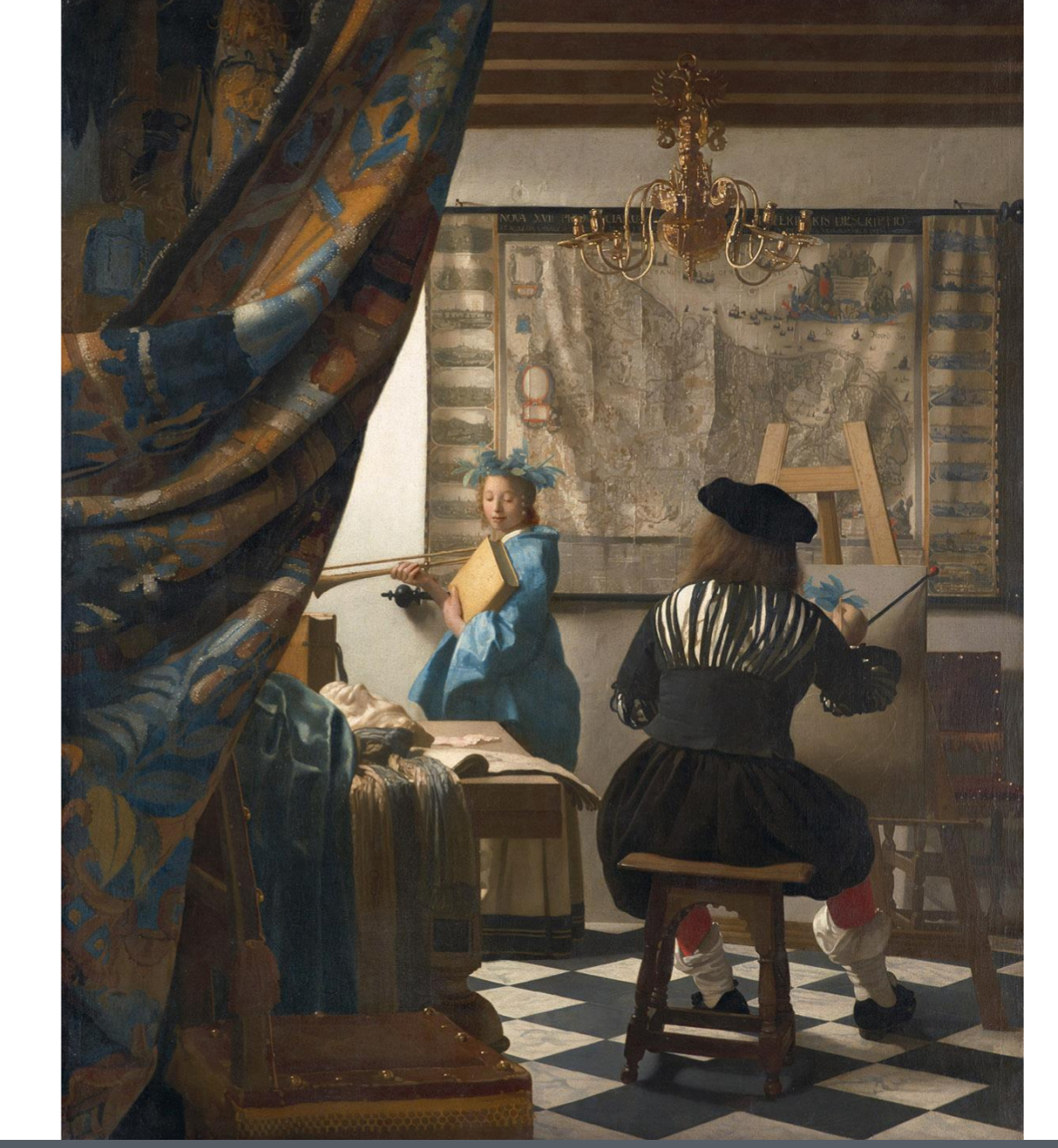

The Art of Painting

Johannes Vermeer

Dutch Baroque

Oil on canvas,

47¼ × 39⅜ in

a showpiece that he displayed in his own studio to demonstrate to potential patrons and visitors the full range of his artistic and intellectual talent

Depicts an artists studio with the artist seated at an easel, painting the female model in front of him

The painter wears elaborate, traditional clothing that allies him with earlier northern European painters

The model holds a book and a trumpet and is crowned with a laurel wreath — attributes that identify her as Clio, the muse of histor

: the painting on the easel; the plaster mask on the table; an ornate gilded chandelier; the tapestry gathered like a curtain in the foreground; and the decorative map on the wall

The book in the model’s hand refers to knowledge, while the mask is a reference to the concept of imitation that was central to the pictorial arts of the period.

The Oath of the Horatii

Jacques-Louis David

Neo-classical

Oil on canvas

10 ft. 10 in. × 13 ft. 11¼ in.

During his long career, David consistently adapted his art to speak to the changing social and political climate of the time

is a high point of the Academic approach to history painting, brilliantly articulating its intellectual, artistic, and social goals.

David painted the work while living in Rome, and the composition and attention to the human figure were based on his study of ancient Greek and Roman art.

The detailed articulation of the men’s musculature and the forms of their bodies, visible even through the surface of their clothes, demonstrates David’s skill with the Academic focus on the human figure.

Compositionally, the painting is rigorously ordered, with a focal point directly at the father’s hand grasping the swords.

The woman dressed in white is Sabina, sister of the Curiatii and married to one of the Horatii brothers. She rests her head in a mournful pose on the chair of Camilla, a sister of the Horatii who is engaged to one of the Curiatii and who tilts her head down in sympathy and sorrow

No matter what the outcome of the battle, these women will lose their partner, their brother, or both. In the end, as the story goes, when the remaining Horatii brother returns home victorious, he finds his sister Camilla weeping over the death of her fiancé and murders her on the spot for placing her own feelings above the glory of Rome.

Marie Fargues, Wife of the Artist, in Levantine Costume

Jean-Étienne Liotard

enlightenment

Pastel on vellum

40⅞ × 31½ in.

Liotard’s work somewhat resists typical European perspective, in which the orthogonal lines create an illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface

Asian art, particularly Chinese and Persian painting, traditionally often used oblique lines that create a flatter picture plane

Liotard partially employs this oblique perspective, in which the seat of the divan does not meet either the wall or its own back at a 90-degree angle creating a slanting, flat effect

shows his wife dressed in the costume of what was then called the Levant, the area of the eastern Mediterranean that sat at the nexus of Asia, Africa, and Europe

Liotard spent five years in the Ottoman Empire and fashioned himself “Liotard, the Turkish Painter” when he returned in 1743 to western Europe

Marie Fargues seems to have shared, or at least humored, her husband’s enthusiasm for Turkish fashion

Her shalwar, or loose trousers gathered at the ankle, were considered radically modern

Fargues’s braided hair is gathered in a vaguely turban-like scarf, and she sits on a divan, a low, armless sofa with a cushioned back that, along with the patterned, flat-woven rug, was an essential feature of any supposedly exotic European interior.

By depicting her in an easy, informal posture, with an expression that suggests she is lost in thought, and with the sewing basket and book next to her on the divan, Liotard implies that she is not posing in costume but rather has been captured in a private moment in her own home.

Liotard was especially known for his almost complete lack of shadowing on the faces of his subjects

“The Tête à Tête,” from Marriage A-LaMode, c.

William Hogarth

enlightenment

Oil on canvas

27½ × 35¾ in

A satirical piece on the taste the elite have and a mockery of modern fashion

Hogarth called his prints “modern moral subjects,” and his goals were both comedy and commentary

an equal-opportunity satirist, taking aim at the highest and lowest members of society and everyone in between.

Hogarth shows the newly married couple’s financial stability and morality to be as shaky as their commitment to their marriage

features a couple at a mahogany tea table set with Chinese porcelain in a room adorned with an oriental rug and Italian paintings

The couple slouch in their chairs

Lord Squanderfield stares absently at the floor, with a broken sword at his feet, signifying impotence.

A black mark on his neck is perhaps a beauty patch to place over a blemish — could also allude to the lesions that result from syphilis

a tiny dog (often a symbol of marital fidelity) sniffs at the frilly maid’s cap stuffed in his pocket

Lady Squanderfield sits with legs splayed and arms raised in a wakeful stretch, holding a small cosmetic mirror in her hand

Her pose is confident and lewd; her gaze is sly

A mantel crammed with knickknacks—Chinese porcelain dolls in parody of the fashionable style of Chinoiserie, a male Roman portrait bust with a badly repaired nose and woman’s hairstyle—presides above the couple’s heads

The room beyond is decorated with paintings of the apostles

Madonna of the Long Neck

Parmigianino

Mannerism

Oil on panel

7 ft. 1 in. × 52 in

The Virgin, with her extended neck and petite head, gazes down at Christ, whose stretched-out body sprawls across her lap in a deep sleep that prefigures his premature death

Christ’s pose also recalls that in Michelangelo’s Pietà but his proportions do not conform to the Classical ideal

More concerned with the flow of the painting and not with anatomy

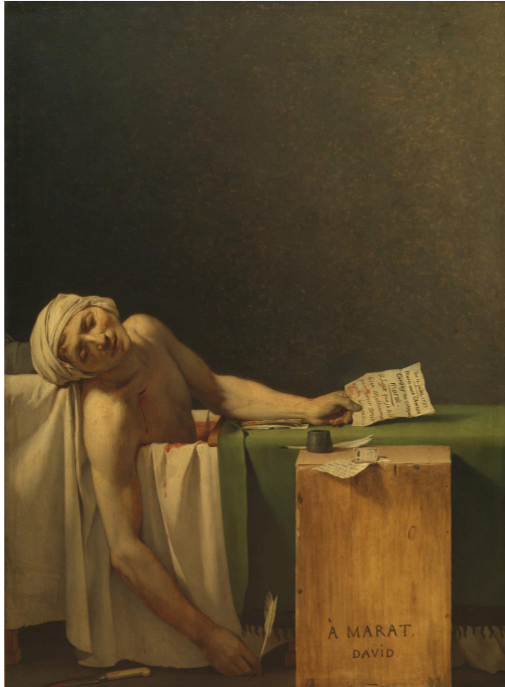

The Death of Marat

Jacques-Louis David

1793.

Oil on canvas

5 ft. 5 in. × 50⅜ in

David’s personal and political tribute to the revolution

It depicts the murder scene of David’s friend and fellow Jacobin Jean-Paul Marat (1743–1793), an author and scientist who became a radical journalist and revolutionary leader.

Marat was murdered by Charlotte Corday (1768–1793), a member of the rival Girondin faction.

Corday gained access to Marat’s home under false pretenses, and upon admittance, she stabbed him to death in his bathtub

. David created this work as an homage to his friend and ally, signing the painting poignantly in the foreground—“To Marat, David”—and in the process he created a radically modern history painting

Marat slumps over the tub, his quill still in one hand, Corday’s duplicitous letter in the other. His slack pose (as with West’s General Wolfe before him) resembles the martyred Christ in his descent from the cross

Marat’s body is fictionalized with an athletic physique, with no trace of the skin condition that forced him to spend most of his time in a medicinal bath

a single wound to his chest with a small trickle of blood.

A dark, plain background takes up nearly half of the canvas, highlighting the vibrantly illusionistic crate and green cloth over a slab of wood that Marat used as a meager desk.

Bathed in a holy warm glow of light, this idealized, humble image of Marat renders him universal, identifiable to all as a martyr.

Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor)

Diego Velázquez

1656. Oil on canvas

10 ft. 5⅛ in. × 9 ft. ½ in.

The viewers perspective is that of the king in queen, shown in the mirror

captures a sense of reality while also highlighting the illusory nature of depiction

Princess Margarita—the only heir to the Spanish throne—stands in the center foreground surrounded by her attendants (las meninas), along with two people with dwarfism who were members of the king’s court.

The princess appears to be posing for her portrait, though her back is turned to the painter behind her

That painter is a self-portrait of Velázquez, standing with palette and brushes in front of a massive canvas

Velázquez was not only painter to the king but also a palace chamberlain

The red cross on his chest indicates his membership of the Order of Santiago,

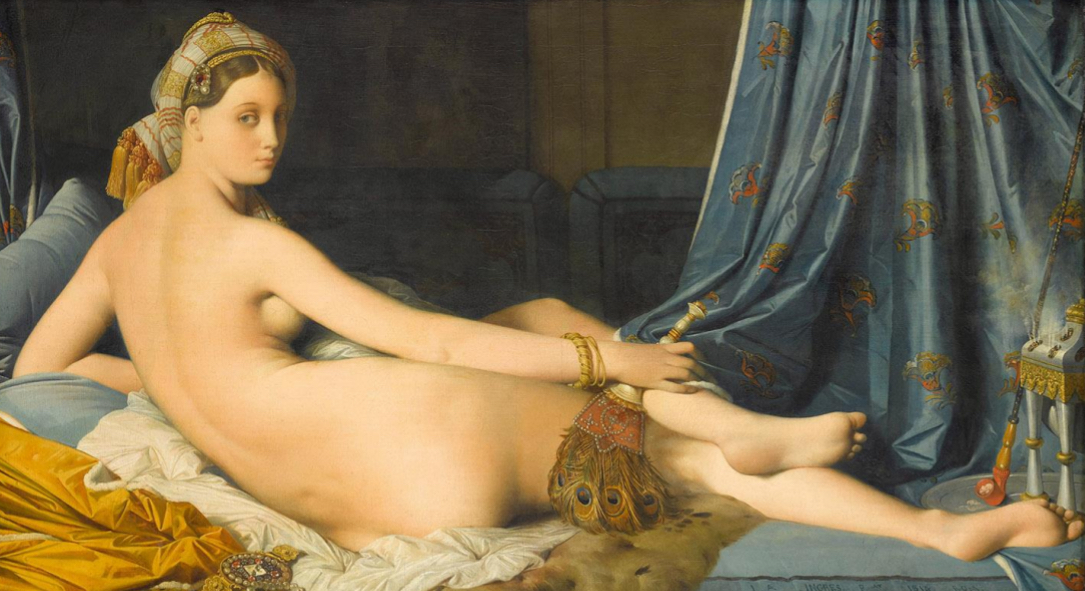

Jean-AugusteDominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque

1814

Oil on canvas

36 in. × 5 ft. 3 in.

The light in La Grande Odalisque appears to come from the front, minimizing shadows and making the edges of forms stand out

Shown mainly from the back, the woman twists to gaze coolly at the viewer, holding a phallic peacock-feather fan in her right hand

The idealized face resembles those in paintings by Renaissance artist Raphael

. Ingres deviated from the idealized but believable anatomical proportions of Classically beautiful bodies to distort the woman’s body

She appears to have extra vertebrae in her back, widened hips, and an impossibly long right arm with no joints

The elongations evoke images by sixteenth-century Mannerists,

The long, sinuous curves emphasize the erotic sensuousness of her body, contradicting the artist’s controlled technique and the woman’s aloof expression

e follows in the tradition of the reclining female nude, a major theme in European art.

. Ingres’s justification for the nudity and erotic pose in a painting made for public display was that the woman belonged to a foreign world, where European rules of propriety allegedly did not apply.

Paul Revere

John Singleton Copley

1768.

Oil on canvas

35⅛ × 28½ in.

depicts Paul Revere, the Boston silversmith who became a political revolutionary, as a craftsman engaged in his trade. Posing without a wig or coat he wears simple work clothes: a plain white linen shirt and an unfastened blue-green vest.

The combination of austerity and the suggestion of richness add to the illusionism of the portrait

The crisp folds and billowing texture of Revere’s linen sleeve pop out against the deep-black background of the portrait — the detail mimics that of still lifes

luminous depiction of the silver teapot

The dull leather cushion along with the black background, provide a matte contrast to the silver teapot and the polished mahogany table

His right eye stares directly toward the viewer, his eyebrow arched in wry cheerfulness, while his left eye remains unfocused almost entirely obscured in darkness and suggesting a psychological complexity; this is an image of a man who works with his hands and his mind. In this genuinely reflective portrait,

Copley depicts his sitter as both a craftsman and an individual.

The Raft of the Medusa

Théodore Géricault

1818–19.

Oil on canvas,

16 ft. 1 in. × 23 ft. 6 in.

. The enormous scale matches grand history painting, but the theme, an actual shipwreck of a French naval ship on its way to a French trading post on the coast of Senegal, in Africa, which had occurred just three years earlier, was of the moment.

Approximately 150 people set forth from the wreckage on a makeshift raft, but only fifteen survived.

The painting mixes real details with conventions derived from past art

For the design, he borrowed a Baroque-style triangular composition receding into depth. The pyramid fuses together the survivors rising to wave at a distant ship, with an African man at the apex

The sea rises in a second pyramidal shape on the left, threatening to engulf the raf

. Strong contrasts of light and dark and twisting poses intensify the drama.

A tangle of naked corpses with idealized body types sprawls across the lower part of the painting, along with an older man grieving his dead son.

The raft fills the width of the canvas—almost 24 feet across—showing the mingled death, anguish, and hope in extreme close-up.

The theme that The Raft of the Medusa takes is the epic struggle for survival against the sea—a Romantic theme

The Ambassadors

Hans Holbein the Younger

1533

Oil on panel

6 ft. 9 in. × 6 ft. 10 in.

It shows Jean de Dinteville, the ambassador of Francis I of France

Skull can be seen 3D if you look at it from the side

Georges de Selve, the French Bishop of Lavaur, who were both in London to persuade Henry VIII to keep England Catholic

The painting exemplifies Holbein’s capacity for precise realism and his ability to capture minute descriptive details.

The two figures stand beside a table filled with objects related to earthly existence, including musical instruments, books, globes, and optical devices, which served as symbols of humanistic pursuits and advancements in scientific measurement and observation.

The ambassador, standing proudly on our left in a broad-shouldered, fur-lined cape, holds a spyglass in his hand and wears an honorific medallion around his neck.

The bishop, who, on our right, fills a smaller portion of the painting, holds his robe close to him in a more restrained manner.

the bishop’s brown fur robe also speaks of material wealth, which helps to explain the distorted, illusionistic image of a human skull stretching across the bottom foreground of the painting in an anamorphic projection

Skulls were reminders of humans’ fleeting earthly existence and a warning to focus on eternal salvation rather than the trappings of the material world.

Am I Not a Man and a Brother?

William Hackwood (modeler) for Wedgwood

1787

White jasper, black basalt, and gilt metal

1¼ in. high

industrial materials and methods of production were also taking hold, particularly in England —

Wedgewood was the first company in the world to employ steamengine technology, and his work promoted the close link between science, industry, and art

Made in support of the British Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Wedgewood continued to produce versions of the medallion throughout the nineteenth century, when people wore it on bracelets, necklaces, hair ornaments, or belt buckles

An indication of one’s opposition to enslavement—a radical opinion in Britain in the late eighteenth century—it signified the wearer’s political beliefs

it nevertheless affirmed the common racial stereotypes of its mostly white audiences, who were accustomed to seeing images of subservient Black figures

The question “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” surrounds a man kneeling with his hands clasped, thus associating the figure of the enslaved person with Christianity and therefore, according to the prevailing view of the time and culture, civilization

The phrase is reminiscent of English scripture and the pose is one of prayer.

The kneeling figure’s imploring gesture and the shackles that chain his hands, feet, and neck depict him as a supplicant, begging heaven and white society to recognize his humanity.

The medallion reflects the paradox of contemporary Enlightenment ideas that simultaneously advocated rationality and human equality, while creating racial hierarchies that justified the institutions of enslavement and colonialism.

That both the institution of enslavement, and the movement to abolish it, used Enlightenment theories for their justification

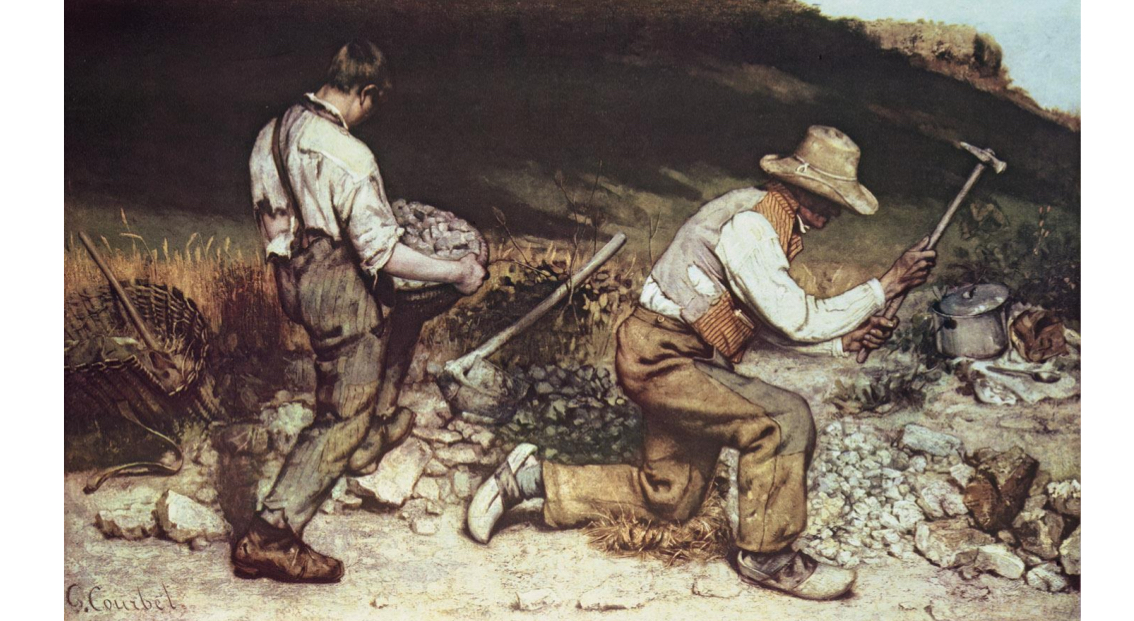

The Stonebreakers,

Gustave Courbet

1849– 50

Oil on canvas

5 ft. 5 in. × 8 ft. 5 in

Formerly Gemäldegalerie, Dresden, Germany (destroyed in the bombing of Dresden, 1945)

Courbet hoped his viewers would empathize with the poor and downtrodden

There is nothing heroic or sentimental about The Stonebreakers (Fig. 61.10), an image of backbreaking labor

A man and a boy are shattering stones by hand to make gravel for roads, a grueling job that today would be accomplished with heavy machinery

The figures, who are painted life-size in the extreme foreground, wear patched, torn clothing and cracked shoes.

Their faces are turned away, making them not individual portraits but representatives of workers at the bottom of the economic scale.

Style and technique were important to Courbet as a means of conveying his socially progressive political message.

The figures are not idealized body types. Courbet actually saw these two people working and asked them to model for him in his studio.

He painted the figures with the same brown and gray colors as the background hill and stones. As a result, the forms blend together, suggesting that the workers are trapped within their limited environment.

Courbet’s technique includes rough brushstrokes, as well as the use of a palette knife to lay on areas of thick, crusty paint.

The image suggests an unedited factual record because it lacks the artificial formulas that reordered raw experience into a unified composition, such as freezing a scene at a dramatic moment.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Rembrandt van Rijn

1632

Oil on canvas

5 ft. 6¾ in. × 7 ft. 1¼

established Rembrandt’s reputation in Amsterdam, bringing the Baroque qualities of realism, intimacy, and dramatic lighting and composition to the group-portrait format.

Rembrandt does not depict an actual dissection, which would probably have begun with the abdomen

Instead, he offers a far more intimate, visually engaging, and imaginative image, with the cadaver foreshortened into the semicircle of men gathered around it

bathed in the same bright light that illuminates the doctors’ faces.

Eight surgeons stand in a curving pyramidal composition, visually stacked upon one another

The man holding the paper behind Dr. Tulp’s right shoulder stares out, which has the effect of bringing viewers of the painting into the group, completing its circle and acknowledging the viewers’ presence as fellow spectators

The painting’s dual attention to the work of both eye and hand addresses the overlapping practices of art and medicine in the seventeenth century, as both professions required skilled handwork

scientists and philosophers embraced empiricism, the theory that knowledge is derived primarily from sensory experience

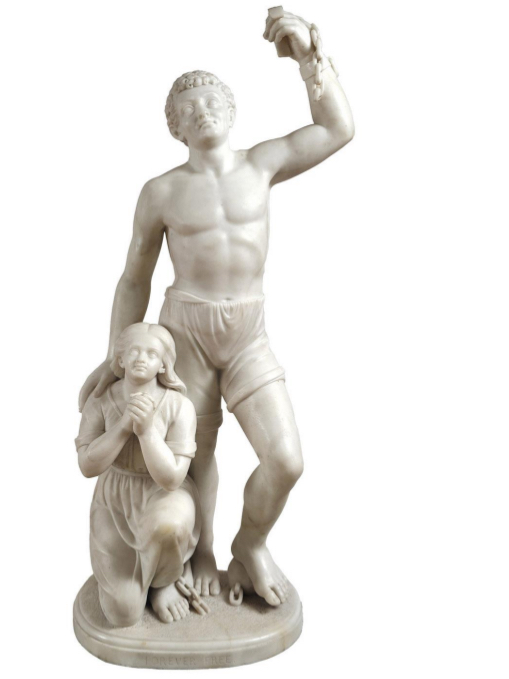

Forever Free

Edmonia Lewis,

1867–68.

Marble,

height 41¼ in.

” Lewis blended Neoclassical elements, including an idealized treatment of form and the contrapposto pose of the male figure, with current subject matter

Her composition binds the two figures together as a unit within an overall triangular configuration.

The man has one foot on the metal ball to which he was once shackled, and he raises a broken chain in his left hand, participating in his own emancipation

Unlike the figure on the Wedgewood Medallion, however, this woman is giving thanks for her freedom rather than praying for it.

Lewis’s version restores dignity to the woman by depicting her clothed rather than stripped to the waist

The Happy Hazards of the Swing

Jean-Honoré Fragonard

1767. Oil on canvas

31¾ × 25¼ in

represents a high point of the Rococo’s emphasis on play in both subject matter and form

Here Fragonard suggests something of the pleasurably dizzy sensation of swinging and its attendant visual disorientation

depicting a fashionably dressed woman in pink being reeled back on a swing by an old man seated on a bench amidst a hazy landscape.

The sexual euphemisms in this image are so overt as to be comical, which was entirely the point of the painting

is an explicitly erotic painting that celebrates the potential freedom and pleasure of a secret sexual liaison.

Cupid’s shush allows the viewer to share in the joke of the hidden lover

The brushwork of the surrounding landscape is loose and agitated, while all of the figures have fully extended limbs, a playful reference to the dramatic diagonal movement that was a feature of the Baroque style.

Pendant portraying Queen Idia

the Iyoba, kingdom of Benin, sixteenth century

Ivory, iron, copper

height 9⅜ in

Mud fish line her head, resembles Portuguese hats

Iron inlaid

During this period, the people of Benin believed that the Portuguese sailors were spirits who came from the land of the dead, for they were as pale as corpses

Rue Transnonain on April 15, 1834

Honoré Daumier

1834

Lithograph, sheet: 13⅜ × 19 in

image: 11¼ × 17⅜ in

Daumier was inspired to create Rue Transnonain by events of April, 1834, when the French government took violent action against on-strike workers who were protesting their economic exploitation and working conditions

produced just months after the event it captures

A police officer was killed during the riots, and in retaliation police broke into a working-class apartment building in Paris killing and wounding people

Daumier shows three generations of a family sprawled on the floor of their apartment with blood everywhere.

The man in the center is tangled in bedsheets. Not immediately apparent, a dead baby lies underneath him. Two other corpses—an old man and a woman—lie at either side of the composition

Although the subject was of the moment, Daumier’s style draws on past art, including images of the dead Christ

the figure is forshortend

However, the police quickly confiscated all circulating copies.

Judith Slaying Holofernes

Artemisia Gentileschi

c. 1620.

Oil on canvas

4 ft. 9¾ in. × 3 ft. 6⅝ in

Gentileschi seems to have understood the power of drawing an analogy between the artist and her painted subjects

The first version of Gentileschi’s numerous Judith paintings was probably painted immediately following the trial of 1612 in which her father accused his former colleague of raping Artemisia

During the trial, Artemisia provided direct testimony of Tassi’s violent sexual assault, which was facilitated by her supposed friend Donna Tuzia

it is overly simplistic to interpret Judith Slaying Holofernes solely in biographical terms as a revenge fantasy

The painting’s clever allusions, the tremendous dynamism of the composition, the gripping emotion of the subject, and vivid illusionism place Gentileschi among the principal exponents of Baroque naturalism in painting.

The Calling of St Matthew

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

1599–1600

Oil on canvas

10 ft. 6 in. × 10 ft. 9 in

Jesus is pointing but we do not know who he is pointing to

Considered Baroque naturalism, based on a dark, dramatic, and vividly realistic treatment of his subjects

represents the moment in which Jesus calls Matthew, at that time a tax collector named Levi, to follow him.

The scene is one of spiritual conversion, the moment in which a lost soul is called to Christ

the strong diagonal line created by the light flooding in from an unseen window, is directed at the bearded man

A strong contrast of dark and light, known as tenebrism, adds a sense of drama to the image.

Caravaggio enjoyed visual ambiguity, which allowed the viewer to interpret the work subjectively

Levi sits among a group of opulently dressed but spiritually bankrupt men gathered around a table counting their riches, while Christ and his brawny companion, Peter, are barefoot and dressed as humble travelers.

Lady Sarah Bunbury Sacrificing to the Graces

Joshua Reynolds

1763–65

Oil on canvas

7 ft. 11½ in. × 59¾ in.

Reynolds developed a style that became known as the Grand Manner. Grand Manner portraiture flattered the nobility of the sitter and elevated the status of the portrait painter

Kneeling on one knee, she offers liquid that wafts up to the statue as fragrant steam. The middle Grace in the statue seems to come alive to return the honor, reaching out to offer Lady Sarah a tiny laurel wreath. In this way, Reynolds draws a circular connection between the Graces and Lady Sarah, conferring on his subject the Graces’ charm, beauty, creativity, and imagined racial purity.

Lady Sarah Lennox (1745–1826) was well known for her beauty, attracting the attention of King George III when she was fifteen

Her husband commissioned Reynolds to depict his wife in this portrait shortly after their marriage

depicts Lady Sarah dressed in a style that seems vaguely reminiscent of the ancient Romans

paying tribute to a statue of the Three Graces, a trio of Greek mythological goddesses associated with charm, beauty, and creativity

The painting includes many references to ancient Roman culture.

Just as Neoclassical sculpture and architecture (such as Figs. 57.3 and 57.6) emphasized the aesthetics of white surfaces, eighteenth-century European portraits communicated contemporary racial ideology that established whiteness as a supposedly superior racial category

In keeping with the principles of Neoclassicism, Reynolds did not simply copy ancient art. Rather, he built on existing artistic models to make something new

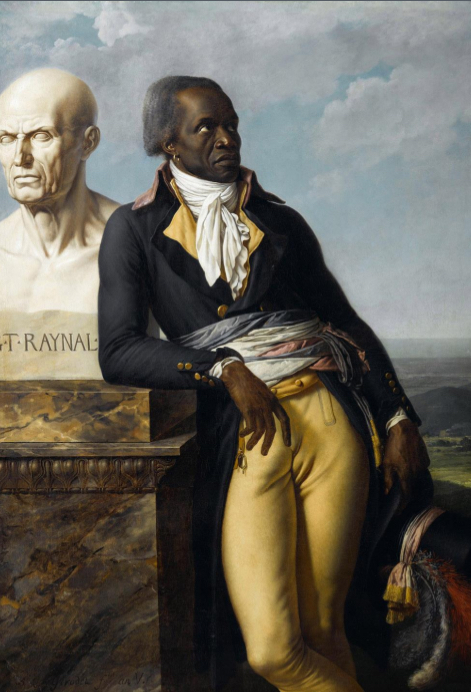

Portrait of Citizen Belley, ExRepresentative of the Colonies

Anne-Louis Girodet

1796–97

Oil on canvas

5 ft. 2½ in. × 43¾ in.

Belley was born in Senegal and transported as an enslaved child to Saint-Domingue. He purchased his freedom in 1764 and joined the French army, fighting with French-American forces in Georgia during the American Revolutionary War

Once back in Saint-Domingue he became a merchant.

He was a leader with and other self-liberated enslaved people of the Haitian Revolution of 1791

Girodet’s portrait of Belley celebrates that triumphant democratic moment, picturing a new type of citizen.

He stands in a specific place: the landscape beyond him depicts the interior mountains of the north side of SaintDomingue

Belley is a symbol of liberty — He is literally wrapped in the revolutionary French flag, a redwhite-and-blue sash around his waist with feathers of the same color adorning the hat he casually holds in his left hand

color adorning the hat he casually holds in his left hand. His contrapposto pose and eyes gazing skyward suggest a confident, free individual.

The visual contrast between white and black is repeated throughout the composition

Belley’s crisp white cravat around his neck contrasts with his dark skin and the deep color of his coat.

Girodet also emphasized Belley’s groin

A Burial at Ornans

Gustave Courbet

1849–50

Oil on canvas

10 ft. 4 in. × 21 ft. 11 in.

A Burial at Ornans is an enormous group scene of a country funeral in Courbet’s small hometown

The burial has not yet taken place. There is a newly dug grave at the bottom center of the painting, surrounded by a great S-curve of pallbearers, clergy, altar boys, a dog, and a sea of black-clad mourners

e. The painting does not idealize the figures or the scene, nor does it dramatize the experience of grief with extravagant gestures, as a Romantic painting would.

To contemporary sensibilities, the composition seemed badly organized.

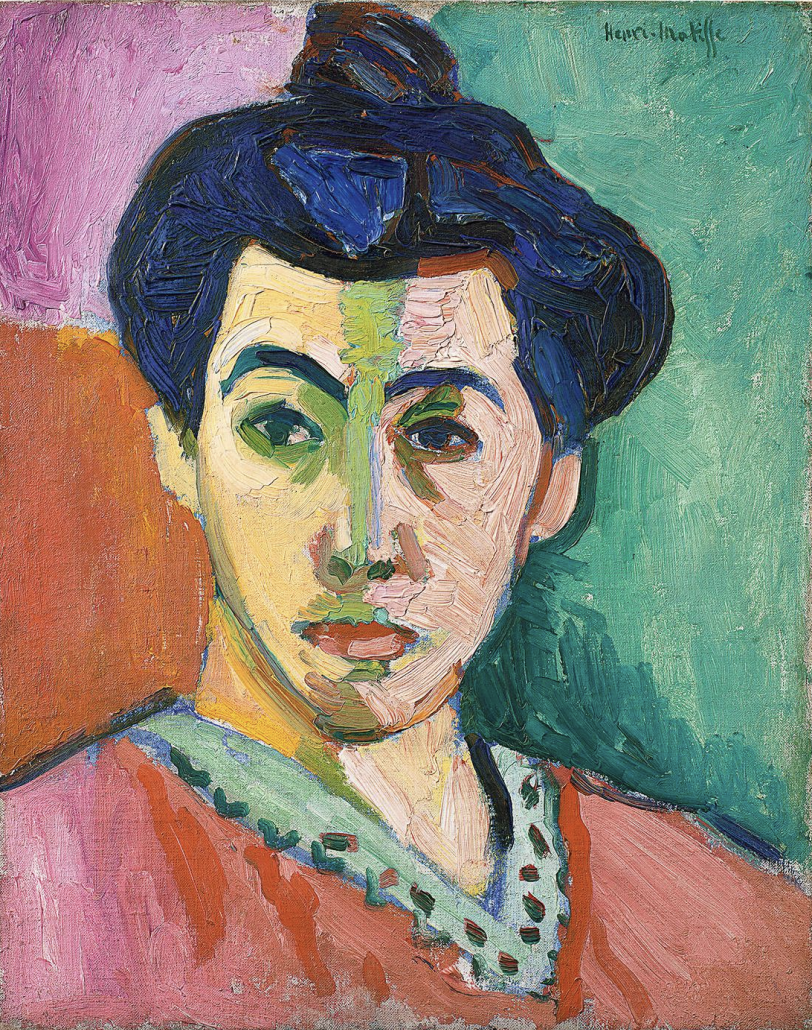

Portrait of Madame Matisse

Henri Matisse

The Green Line

1905

Oil on canvas, 16 × 13 in

Nicknamed the Green Line because of the green line separating the portrait

Matisse realized that color relationships can be adjusted merely by changing the proportion of a color in a painting

As he said, “One square centimeter of blue is not as blue as a square meter of the same blue.”

his use of saturated colors, simple flowing lines, flattened pictorial space, and limited detail had a deep and widespread influence

Matisse claimed to be seeking emotional expression, but his emotions—like those of Derain and other Fauves—are positive, not gloomy and anxious

The Basket of Apples

Paul Cézanne

c. 1893.

Oil on canvas,

25½ × 31½ in

He was of the same generation as the Impressionists

He expressed enormous admiration for Monet’s ability to discern subtle nuances in the light and color of a scene he was observing directly

Cézanne did not want to achieve such compositions by replicating the techniques of Old Master painters, such as one-point perspective and the dark-to-light modeling of chiaroscuro

Instead, Cézanne continued the swing away from what remained of the Renaissance tradition.

He embraced the bright color palette and broken brushwork of the Impressionists

he took those practices in a conceptual direction and experimenting with space, time, perspective, and color

In The Basket of Apples, for example, painted objects appear in ways that would be physically impossible with real objects in real space

The sides of the table do not align to form a connected rectangle, as those of a real table do

The tabletop is tilted, while some of the fruit is seen straight on. The bottle appears warped because the curves of the left and right sides do not mirror each other in a symmetrical fashion.

He chose to distort the appearance of objects if doing so served to make a composition more solid or expressive

Cézanne wanted to find new means to construct a coherent painted image that would still remain true to the process of seeing.

The Starry Night

Vincent van Gogh

1889

Oil on canvas

29 × 36¼ in.

Van Gogh turned vivid color and emphatic brushstrokes into vehicles for self-expression, distorting reality in order to express emotions

He intensified colors, lines, and textures, and he distorted shapes to communicate his fervor

The sinuous vertical strokes that define the flame-like cypresses in The Starry Night seem to embody fertility and growth

Equally vigorous are the diverse, contrasting strokes of paint covering every other area of the painting, making the mountains, sky, moon, and stars all appear ablaze with life and movement.

Various forms are emphatically outlined, including the cypresses, mountains, and the huddled buildings and church steeple of the village.

The vibrant yellows of the heavenly bodies glow against the contrasting blue shades in the sky; their halos of light lend them the aura of religious icons

Van Gogh was interested in the science of complementary colors, and he used his knowledge to select colors not for naturalistic effects but for symbolic and expressive purposes.

The Rehearsal

Edgar Degas

c. 1874.

Oil on canvas,

23 × 33 in.

The bold composition in Degas’s painting The Rehearsal deviates from linear perspective

Degas understood that we do not usually see the world as in traditionally composed pictures, with perfectly centered images and space receding with mathematical regularity.

Instead of looking straight ahead, the viewpoint in The Rehearsal is slightly from above.

Picture space is compressed, with an asymmetrical arrangement of forms. Degas has left a wide area of floor space in the center empty and looming upward, with dancers concentrated in the upper left and right front.

. The open floor is animated by looping shadows from the dancers and by warm tones of sunlight

An important influence on Degas’s novel approach to composition and his interest in depicting a quick moment in time was photography—specifically the candid photographs

Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (Luncheon on the Grass

Édouard Manet

1863.

Oil on canvas

6 ft. 10 in. × 8 ft. 8 in.

caused a particularly negative reaction among most critics and the public

The nudity of the woman shown picnicking with two clothed men was scandalous to conventional morality

Art viewers were used to seeing nude women in paintings only when depicted as goddesses, characters from literature, or exotic foreigners

. Here, the clothing of the two young men identifies them as modern Parisians

. The nude woman’s discarded clothing, also in the latest fashion, is arranged with fruit, bread, and a picnic basket in the lower left.

Many viewers assumed that both women were prostitutes.

To many viewers, Manet’s technique was just as offensive as the subject matter.

His large, separate brushstrokes looked crude compared to the blended brushstrokes and polished surfaces of Academic art

Manet downplayed traditional illusionistic devices such as the use of linear perspective and chiaroscuro modeling.

The figures do not appear integrated into the space of their surroundings.

For example, the bather in the background would be smaller and dimmer if Manet had chosen to represent perspective accurately.

There are no middle tones in the flesh to create gradual transitions between the lightest and darkest areas as a means to create an illusion of volume.

The only shading on the underside of the nude woman’s thigh is a narrow black line, which silhouettes and flattens her form.

Manet makes numerous allusions to “museum” art.

The composition of the three central figures is copied from a group in a print by Marcantonio Raimondi after a painting by Renaissance master Raphael