Japanese Art History Midterm #2 Review

1/72

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

73 Terms

Tai-an Tea Room, Myōki-an, Kyoto, 16th century

Sen no Rokyu’s tea room in a hut

The most distinguished tea-master of the wealthy Sakai merchant class

Promoted spiritual ideas of ‘harmony, represect, purity, and tranquility’

Noted for having taken the eat ceremony to its farthest extreme

Asymmetric and irregular forms

Rough textured earth walls, unpolished exposed beams

Small in size

The tea house as a personal art forms, catering to the intense Japanese need for the preservation of the private self as distinct from the public space

Shoin-style architecture

Teahouse

The small space forces intimacy and participation

The tea ceremony is very slow and silent

big emphasis on slowness and silence during the whole process

You still have to show your appreciation despite not speaking since everything was made specially and carefully for you

wabicha 侘茶—first formulated by Murata Shukō 村田珠光 (or Jukō, 1423-1502)

“Tea based on wabi”

Sen no Rikyu achieved the ultimate wachiba settings by adopting as his preferred teahouse a stark hut of only two mats in size, which could at most accommodate two or three people in one gathering

There was a compatibility between formal tea, using such utensils, and the “grass” style of informal tea without them

Rikyu found wabi in the vernal grasses amid the snow from late winter to early spring

Shoin-style archtiecture

Chigaidana: asymmetrical overhanging shelves

Fusuma: traditional sliding doors

Shoji: the newer, lighter sliding doors

Consisted of lattice like wooden frameworks with translucent rice paper pasted on one side

Tatami: standardized rush matting used to cover floors entirely

Tokonoma: an alcove

Longquan-ware (celadon) water joa, Song dynasty, China, ca. 1200

Tenmoku (Jian ware) tea bowl, Song dynasty, China, ca. 1200

Korean tea bowl, 15th-century Joseon Korea

Black Raku tea bowl named “Katsujishi” by Chojiro, Momoyama period (16th century)

Weathered over time, wabi aesthetic in the imperfections

Oguro was made during a period of war, thus more dark and simple

More evocative because it makes the viewer more imaginative

More austere ->closer to samurai values of the tea ceremony

Shino-ware (志野焼) tea bowl known as “Kogan” (“Ancient Shore”)

in the wabi-sabi spirit

Cracked and weathered, rustic

Spring grass in the snow?

Nature aspect

Shigaraki-ware (信楽焼) water jar, 15th century

`Rustic flare -> tied to Shinto with the nature aspect

Iga-ware (伊賀焼) water jar known as “Yabure-Bukuro” (“Torn Pouch”)

Himeji (White Heron) Castle, first built in 1346, rebuilt by Hideyoshi in 1581

The purpose of castles is defense, fortification, and also for living quarters and an office for administration purposes

Surrounded by a moat to pose as an obstacle for enemies (first layer of defense)

First gate (second layer of defense)

Second gate

Irregularity in the placement of gates to make enemies lost (should they find their way in)

Third, fourth, fifth gates

The tower (main structure)

Timber structure surrounded by stone

Limited natural light for the sake of fortification

Ōhiroma (Great Audience Hall) of Ninomaru Palace, Noji Castle, Decorated with Kanō Tanyū’s painting of Pines, 17th Century, Kano School

First built by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1602 with two main structures

Ninomaru Palace with Ohiroma (Great Audience Hall) in the center

Shoin-style architecture on a larger scale compared to tea houses

Separate rooms designated for specific groups of people -> elevation is used to determine hierarchy/rank

Ex: samurai/bodyguards/attendants, general public, close friends/allies, the shogun

A sense of vulnerability and gentleness

Sliding doors

Ohiroma (great Audience Hall) of Ninomaru Palace, Nijo Castle, with Kano Tanyu’s paintings of Pines

The gold background helped to reflect the little natural light and candlelight in the dark rooms

The gold was also considered expensive and tied to power

Eitoku, Cypress, Kano School, eight-panel byōbu (folded screen), Momoyama period, ca. 1580

Twisting, gnarled cypress trees set against a background of rocks, azure water, and gold-leaf clouds

Very bold

Old pine and evergreen trees shows hardship since they’re able to survive so many winters

Shows power and vigor and endurance

A big pine tree was always used as the main subject of panels (so big that parts have to be cut off)

Cut-off composition continues from Tale of Genji paintings

Gold clouds

The choice of the specific tree (Japanese cypress) is tied to the Japanese identity

Byobu was mainly used during the Heian period

It means portable

Eitoku’s is much bolder, with less attention to detail (compared to Tohaku’s Maple tree and Flowers)

More bold and masculine

More defined

No signature

Bold in color

Lots of details

more decorative

Strong sense of a pattern

Echoes of the shape of the branches in the background

Eitoku, Kano School, Four Season Landscape, 16 fusuma (sliding-door) panels, Momoyama period, 1566

Kano school style is rooted in Chinese landscape paintings

It was this that the personal style of Eitoku emerged against the more conservative one of Shoei, most notably in his monumental forms of the pine tree

The form of the sturdy pine trunks dominates the composition, bringing the foreground elements closer to the picture plane and the viewer

At the same time facilitating the rapid horizontal, sequential movement of the panels from right to left

He always emphasized the picture plane and made no effort to draw the viewer’s attention into the background

He was preoccupied with the rendition of a single motif dominating a composition

Kano school style: singular, dominant motif that occupies the focus and extends beyond each panel

Reminiscent of Yamato-e with the small subtleties and the sensitivity to nature and the changing of the seasons

Very evocative

Very sketchy (brushstrokes are very obvious)

Eitoku, Kano School, Four Season Landscape: Spring, 16 fusuma (sliding-door) panels, Momoyama period, 1566

Very sketchy and calligraphic (the hand/brushwork of the artist is very clear)

Not a gold background, but yellowish

Eitoku, Kano School, Four Season Landscape: Autumn, 16 fusuma (sliding-door) panels, Momoyama period, 1566

Very chinese

Very poetic

Eitoku, Kano School, Four Season Landscape: Winter, 16 fusuma (sliding-door) panels, Momoyama period, 1566

Tohaku, Maple Tree and Flowers, four fusuma panels, color and gold leaf on paper, Momoyama period, 1592

Kano school style/composition

He trained in the Kano style

Made right after Eitoku’s death

Importance and prominence of Eitoku

Tohaku’s is much more dynamic and detailed (compared to Eitoku;s Cypress)

Also has a stronger diagonal in the angularity of the tree

Much more subtle -> attention to details

Particularly the details in the leaves and flowers of the tree

Very sweet, more feminine

More reflective of the taste of the urban townspeople

Tohaku, Pine Trees in Mist , Right screen; pair of 6-panel screens, ink on paper, late 16th century

Completely opposite of the Kano school style

Far more simple

Ink monochrome

Only black and white

Reminiscent of Zen paintings and Sesshu’s work

Asymmetry, simplicity, unadorned loftiness, spontaneity, spiritual depth, unworldliness, inner serenity

Sense of eeriness and mystique

Lot’s of space, very atmospheric

Subtle and faint lines for the mountains in the background

Lack of a center -> no dominant motif

There is still a motif of the pine tree but executed differently

repetition through variation

A sense of rhythm, lot’s of vertical and diagonal lines

A diagonal leads the viewer’s eyes to the mountain

A superb synthesis of chinese media and techniques with japanese expression

Nearly 85% of the painting surface is left blank and yet the entire screen is suffused with a sense of the mists and stillness of an autumn dawn

He shows the trees tall and gaunt, using a straw brush on thin, coarse paper, varying the intensity of his ink from faint to dark in swift, sure strokes

His cluster of pine trees strikingly enhance, in the best Zen-like tradition, the emptiness of the remainder of the screens’ surface

This painting is the culmination of his attempt to unite the Chinese and Japanese artistic styles

The grove of pine trees, which had long been a favorite subject of traditional yamato-e paintings, has here been executed in the new Chinese style of ink painting

The deception even permits the flickering of the morning light in the mist to be perceived, and most importantly, the sense of progress in time from dawn to the early morning, suggested by the movement of mist through the pine trees

This insertion of the time element in a painting is clearly the expression of the concept of mujo which symbolizes the ever-changing nature of worldly phenomena, and is the essence of Japanese art

Kōetsu, Raku tea bowl named “Fujisan” (Mt. Fuji), early 17th century, Rinpa School

The opaque white glaze over the upper half, leaving the darker glaze for the bottom creates an effect by firing of gently falling snow

The vigor and grandeur of Mount Fuji are suggested

The impression is of monumentality

Keotsu echoed the simplicity and purity of Rikyu’s time, following the forthright form produced by Chijiro

Shows the rise in the tea ceremony

Rinpa school style

Compared to Black Raku tea bowl named “Oguro” by Chojiro, 16th century

Fujisan is more of a literary reference

White is used to represent snow (snow-capped mountain top)

A bit more of a sense of flavor

Shows the more urban tastes of merchants/consumers

a sense of rustic beauty

Kōetsu, Inkstone box "Boat Bridge,” Momoyama-early Edo, early 17th century, Rinpa School

Contains inkstone, ink, and brush

Clearly inspired by Heian lacquers

Although the box is nearly square, the decoration is entirely asymmetrical

Balance is restored by the inscription of a waka poem, applied in high relief silver over the whole scene

Rinpa school objects all had names

Merchants emphasized good taste since they were of the lowest class

They wanted to show their money

Everything expensive: lacquer, gold, silver, etc

Also wanted to show their education

Reference to poetry

SŌTATSU, Waves at Matsushima (Pine Island) pair of 6-panel screens, ink, color, gold and silver on paper, Rinpa School, early 17th century

Decorative style of the Rinpa school

Makes reference to Ise Shrine

Blue and green are reminiscent of the Heian period and yamato-e

The pattern of the lines in the waves is reminiscent of the Asuka period and its decorative patterns

Sotatsu and Toshichiro, Painted Fans Mounted on a Screen, pair of 8-panel screens, ink, colors, and gold on paper, early 17th century, Rinpa School

Decorative style of the Rinpa school

The fans show images that were popular during the Heian period

The clothing of figures, yamato-e landscape

Fans with rich references -> like tale of genji or a war from the past

Creates something very narrative in the storytelling of the fan images

Kōetsu and Sōtatsu, Flowers (silver pigment) and Grasses (gold pigment) of the Four Seasons, section of a handscroll in the tarashikomi (dripped in) technique, Rinpa School, early 17th century

Rinpa style: repetition of the same motif: flowers

Sensitivity to nature/preference for the four seasons leftover from the Heian period

Gold and silver pigments for color

Koetsu’s calligraphy is heavy and dark, but there are also thin lines

Lots of movement, doesn’t follow a specific structure

Tries to fit in with the composition

Ex: diagonal instead of vertical

Kōetsu (calligraphy) and Sōtatsu (painting) Deer Scroll, sections of a handscroll, ink and color on paper, 1615, Rinpa School

Rinpa style

Repetition of the same motif: deer

A cut-off figure

Heian style calligraphy: cursive, quick and rushed brushwork, the characters blend and flow together

Mix of thick and thin, dark and light lines

Very elegant

Korin, Irises at Yatsubashi (Eight Bridges), pair of 6-panel screens, ca. 1710

Best known painting, in a purely design-like and decorative manner

Inspired by an episode from The Tales of Ise

Made no attempt to reproduce the narrative itself, but simply placed irises in “disembodied” fashion against a stark gold-leaf background

The flowers seem almost to dance before the viewer’s eyes due to the stark contrast of blue and green against the golden screen

The screens seem flashy and light

Traces of black ink outlines are visible here and there

The flower petals have slight shading

The white base color is apparent

All of these elements create a sprightly and showy effect

The gold is shiny and bright

The irises are more realistic, their shape suggesting a variety known as iris laevigata

The bridge is quite stylized

Painted in 1711 to 1715, after Korin returned to Kyoto following a disappointing move to Edo (Tokyo) in search of new patrons

Reflects when the daimyo in Edo had a more conspicuous celebration of classic themes

The later one is a bit more shiny and bright

The gold is heavier

Also has a black outline

Two-step process -> more time consuming, thus more labor needed, thus likely more expensive

Appealed to the taste of the merchants

The bridge and irises come from the story of the Tale of Ise

A literary/narrative reference

A way for the merchants/patrons to display their education along with their wealth

Also a reference to the Heian period through this literary reference

Korin, Irises, pair of 6-panel screens, ca. 1701

Repetitions of a single motif: blue irises, green leaves

Motion is created in the asymmetrical grouping and the repetition of the motif out-of-phase

His daring and unrelenting use of gold, blue, and green, where Korin displays his supreme self-confidence

By removing all external props, “framework” or “borders,” both men plunge the viewer into the scene, and create a sense of dramatic immediacy and personal involvement

The screens seem formal and still

The pigments are built up

In places where the leaves overlap, the individual blades are indicated by the layering of pigment, without the use of outlines

The gold luster is subdued and slightly brown in tone

The irises are fuller and larger, their shape resembling the species known as iris ensata

Painted around 1701-1702, when Korin received the honorary title “bridge of the law, or dharma”

Reflects the popularity of gorgeous gold screens in Kyoto among both court nobility and wealthy townsfolk

the earlier one’s pigment was applied through layering

tarashikomi (dripped in) technique: the method of dropping ink or color pigment on to still-wet areas of the painting surface

Pair of 6-panel namban byōbu by an anonymous Kanō painter color and gold leaf on paper, 17th century

One showing the departure of the Portuguese carrack (great ship) from Goa or Macao and the other its arrival at Nagasaki

More tied to the imperial court

Depicts both Western and Japanese figures

All figures have a ¾ view, looking at the painting of Jesus, except for two figures

One figure is looking directly at the viewer to engage the viewer

Another figure is fully turning their back away from the viewer and facing the Jesus painting

Makes the use of space more interesting

Creates a communication between the viewer and the painting

Jesus looks like Confucius

Nanban (or Namban) 南蛮—literally “Southern Barbarians”

The foreign and exotic culture of the Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries

Much of namban art was either iconographic or religious, but some depicted European cities, landscapes, and nonclerical people

Shiba Kōkan, A meeting of Japan, China, and the West Late 18th century

Separation between China and the West + China by a decorative vase

The Dutch and the Japanese figures are placed sitting close together

An alignment of Japanese with the Dutch

Japan is moving further away from China’s influence and closer to the Netherlands’ influence

China is depicted as something old and ancient

The Dutch depicted as new and modern

Dutch figure: western-style chair

holding a medical book (?) with a picture of a skeleton

Chinese figure:

has a leopard print chair, Chinese-style furniture

has a wooden object in the shape of a fungus

a Chinese-style handscroll

Japanese figure in the middle

represented by the geometric Japanese style of furniture

Holding a folded fan

A snake wrapped around his wrist

Tied to Shinto and Japanese sensitivity to nature

Old-fashioned vase and maple leaves

None of the figures are looking at the viewer

Kano School style

Kōkan, The Barrel-maker, ca. 1789, hanging scroll, oil on silk (yoga)

“-ga” associated with foreignness/non-native things

Based on/inspired by an imported print

More alignment of the Japanese with the Dutch

Done using western-style of painting and technique (oil)

The figures are also in western clothing

The tree framing the painting adds a touch of Japanese style

Anonymous, Bird’s-eye View of the Port of Nagasaki with the fan-shaped Deshima in the foreground, c. 1854-64, Oban woodblock print

Dejima (or Deshima) 出島 in Nagasaki Harbor, built in 1634 (through 1854)

An artificial island was created for the Dutch at the Port of Nagasaki called Deshima

The Dutch were the only Westerners allowed, so the Japanese could learn from them

The island allowed the Japanese to still closely control the Dutch

Maruyama OKYO, Sketchbook of Insects: Cicadas and Bees, ca. 1750

An observation of life

The same subjects in different perspectives

Western training

Maruyama ŌKYO, Pine Trees in Snow in the tsuketate technique, pair of 6-panel byōbu, Edo period, ca. 1780

Compared to Eitoku’s Cypress, ca. 1580

Okyo’s Pine Trees

Less bold in color

Same singular motif of a tree

The tree is cut off due to its size, just like Eitoku’s

Has a signature at the bottom

Both have stretched out branches

More simple

There’s a certain kind of air circulating

A modern feeling through the simplicity

Same subject of a pine tree

Also an observation from life

Molding and shadows to create texture and volume in the tree trunk

Through the use of the tsuketate technique

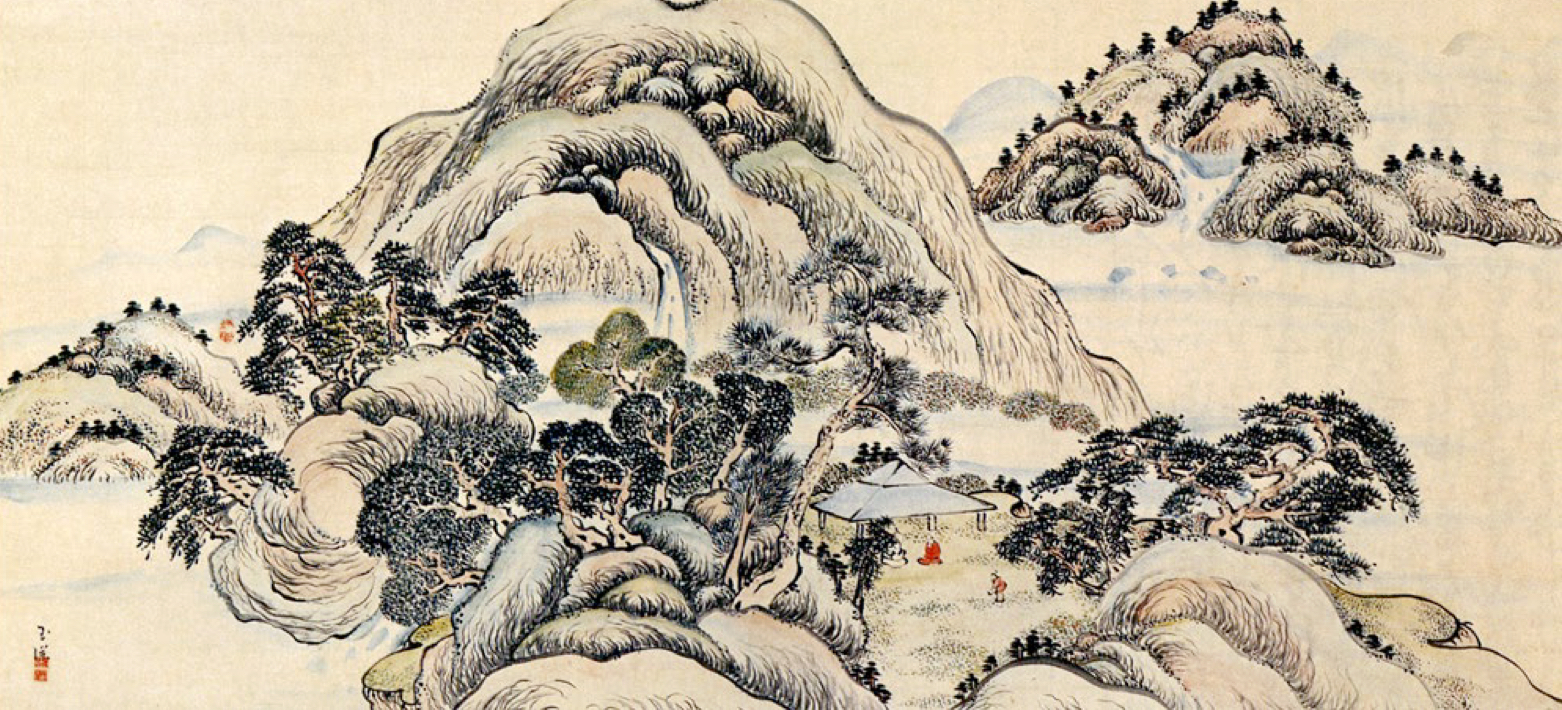

Taiga, First Visit to Red Cliff (illustrating a poem by Chinese poet Su Dongpo in 1082), one of the pair of six-panel byōbu, Edo period, 1749

A historical location where a famous battle took place (a literary reference)

Archaic style of calligraphy for the title

Like a typical Chinese-style painting

It’s still Japanese in the 6-panel byobu format

nanga

Taiga, True View of Mt. Asama, inscribed with a Chinese-style poem ink and color on paper, Edo period, 1760

True view means it will show something realistic, as if you’re seeing it through your eyes

Japanese site paired with a Chinese poem

nanga

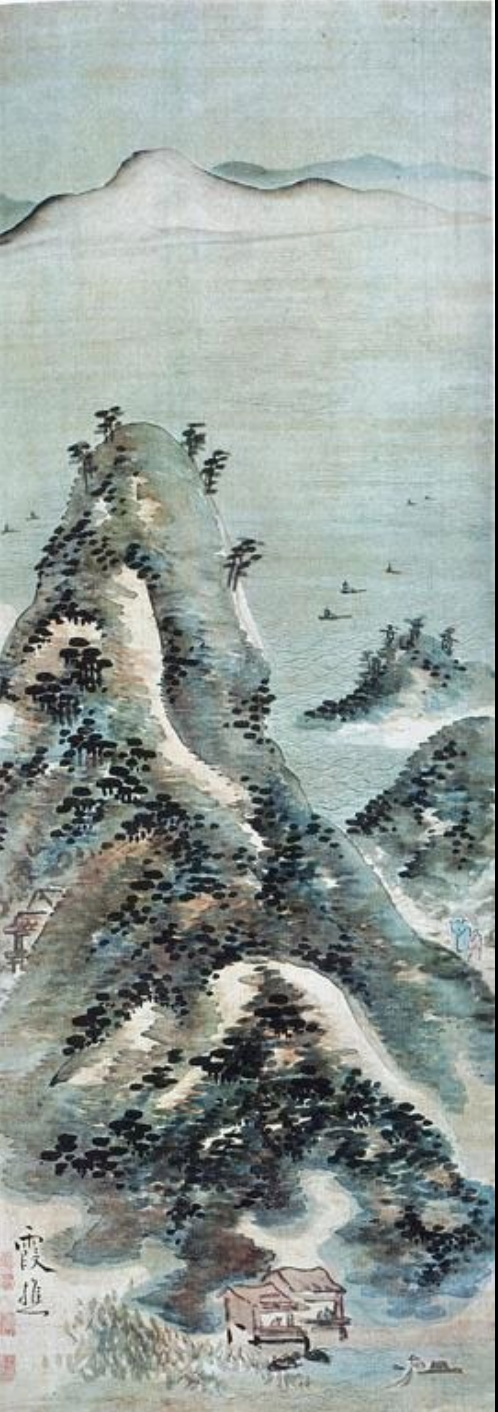

Taiga, True View of Kojima Bay, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, Edo period, ca. 1760

Mi-style (a prominent chinese style) dots technique for the trees

Japanese site/subject in a Chinese style

nanga

Kikaku, Melon Skin, haiga, ink on paper, Edo period

He depicts the most tawdry of objects, a section of melon rind floating down a stream

Just like the subject itself, this is a painting that viewers could easily pass by, in search of something more rare, grand, and colorful

Yet, this unglamorous subject, simply rendered with freely flowing calligraphy, allows Kikaku to express his fresh poetic vision of ordinary life

The painting helps to illuminate the scene, as Kikaku shows that someone had cut the melon in sections in order to eat its fruit

Now these sliced sections of skin gradually spread out and bob on the water

Haiga is the illustration that accompanies haiku (5-7-5 syllable pattern)

Haiku is indigenous to japan, thus so is haiga

The calligraphy is incorporated into the image, it's not separated from the image

Indicates a stronger relationship between the two

A mundane object that invites the viewer to think more deeply about this mundane object that people may typically overlook

Haiga was not created to be sold, thus it is not a commercial artwork (Southern school)

Unlike Rinpa and other professional artworks that were very commercial and meant to be sold (Northern School)

It’s more of a personal expression of the artist’s emotion, much more personal and intimate, much more evocative

Likely is rooted in Zen/teahouses

An irrational connection between melon skin and spider legs floating on the water

A Zen principle

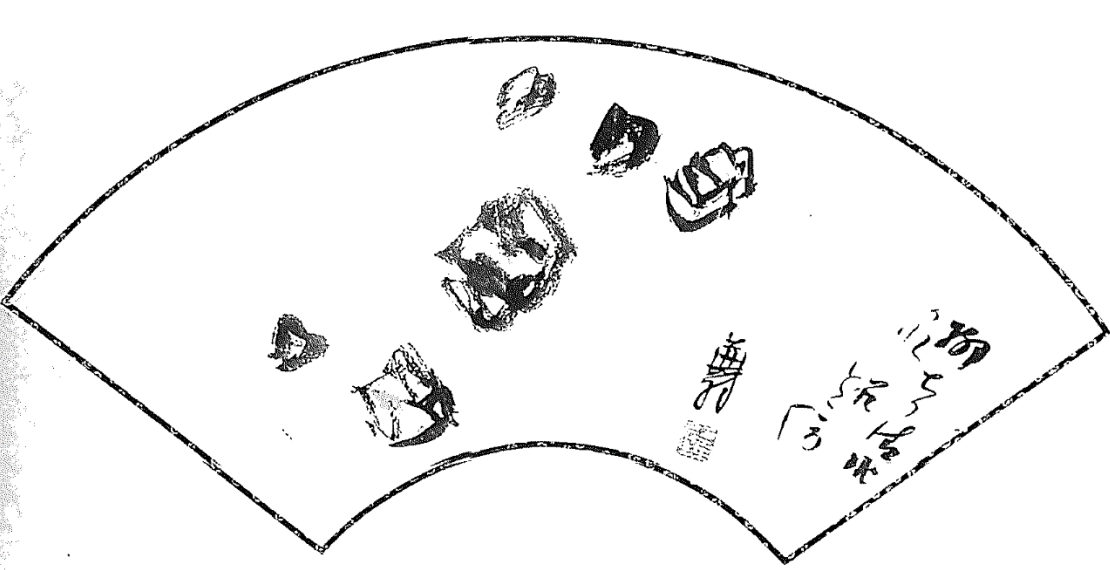

Buson, Rocks Fan, haiga, Edo period

He often painted rocks, sometimes allowing them to float freely over the surface of the painting with no anchor to the reality of ground and gravity

Despite the simplicity of the rocks, they carried with them multiple allusions to Chinese and Japanese poets of the past

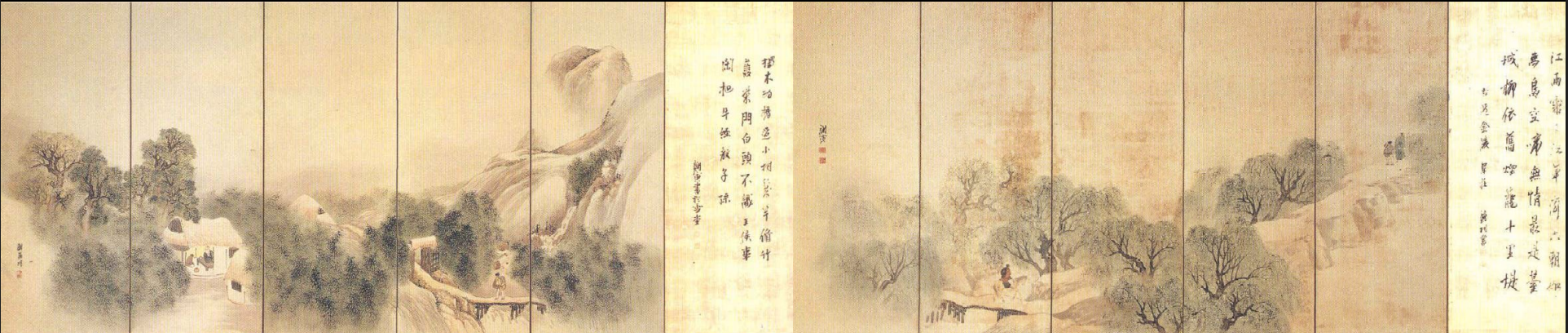

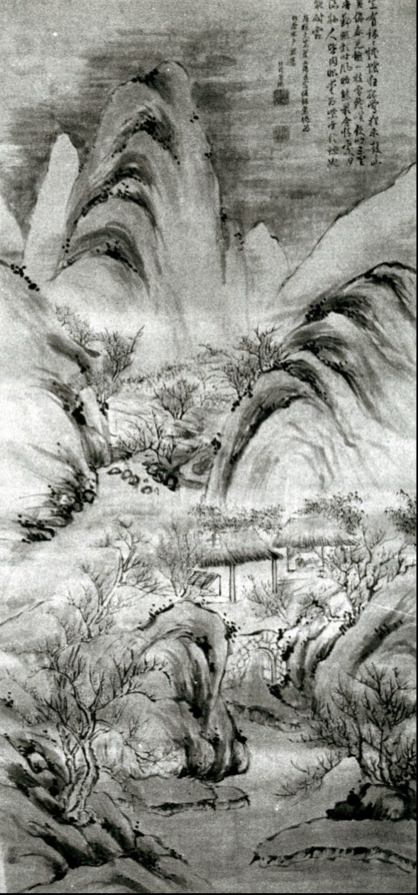

Buson Recluse’s Cottage in a Bamboo Grove, 1770s Pair of 6-panel screen paintings

Buson-Taiga Collaboration Illustrating Li Yu’s (Chinese, 1611-1680) Poems of Ten Pleasures and Ten Conveniences: Taiga’s Ten Conveniences: The Convenience of Fishing 1771

Sketchier brushstroke

More zoomed in, a bit up close

Buson-Taiga Collaboration Illustrating Li Yu’s (Chinese, 1611-1680) Poems of Ten Pleasures and Ten Conveniences: Buson’s Ten Pleasures: The Pleasure of Summer, 1771

More zoomed out

Buson-Taiga Collaboration Illustrating Li Yu’s (Chinese, 1611-1680) Poems of Ten Pleasures and Ten Conveniences: Taiga’s Ten Conveniences: The Convenience of Reciting Poems, 1771

Buson-Taiga Collaboration Illustrating Li Yu’s (Chinese, 1611-1680) Poems of Ten Pleasures and Ten Conveniences: Buson’s Ten Pleasures: The Pleasure of Autumn, 1771

Gyokuran, Orchid, ink on paper, late Edo period

three broad brushstrokes to create the leaves

With two going in the same direction and one going in the opposite direction

Orchids as a subject

Symbolic of the integrity of your high character, regardless of social status/class

Shows the purity of your mind

Orchids were largely painted by women

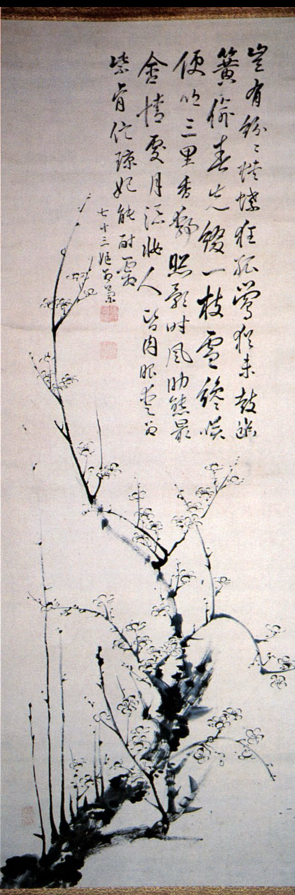

Gyokuran, Plum Blossoms ink on paper, Late Edo period

Depicts an old tree trunk with new leaves and blossoms

Refers to someone who is old (old tree trunk) but still has vitality (blossoms)

Gyokuran, Landscape, ink and color on paper, Late Edo period

Landscapes were considered the most ambitious kind of painting

In order to be considered a successful/respected artist, you need to paint a landscape

Chō KŌRAN, Landscape in the Mi Style, ca. 1830

Under Chikuto’s influence Koran also began to explore the literati landscape tradition, as can be seen in this painting

Like the works associated with Mi Fu, a chinese master of the Sung dynasty, Koran’s painting features mountains composed of overlapping layers of repeated horizontal dots

This work is not dated, but on the basis of style and signature it must be a work of her early career

After placing a foreground bank and a grove of trees at the bottom, she arranged the layers of mountains along a vertical axis, occasionally interspersing plateaus and areas of mist-shrouded houses and trees

By using a range of ink tones from light gray to black, she created a feeling of moist atmosphere and lush foliage

The repetition of similarly shaped mountain forms and brushstrokes establishes a sense of unity and stability

At the same time, the layering of short horizontal strokes creates a shimmering surface pattern

Mi Fu style: (a prominent chinese style) dots technique for the landscape

Used in this case for the trees and mountains

Cho Koran, Plum Villa Landscape for Kido Takayoshi, ca. 1875

Its focus on the elegant beauty of blossoming plum trees dotting the hillsides

By this time her husband had already passed away

Her new patron and friend: Kido Takayoshi

He’s wealthy art collector

A very ambitious painting

Kōran, Plum Blossoms, 1876

This painting in monochrome ink emphasizes the toughness of the old tree with its battered trunk and branches

Both the painting and poem communicate the idea that blossoms last only a moment, but the tree endures

more tied and connected to the poem

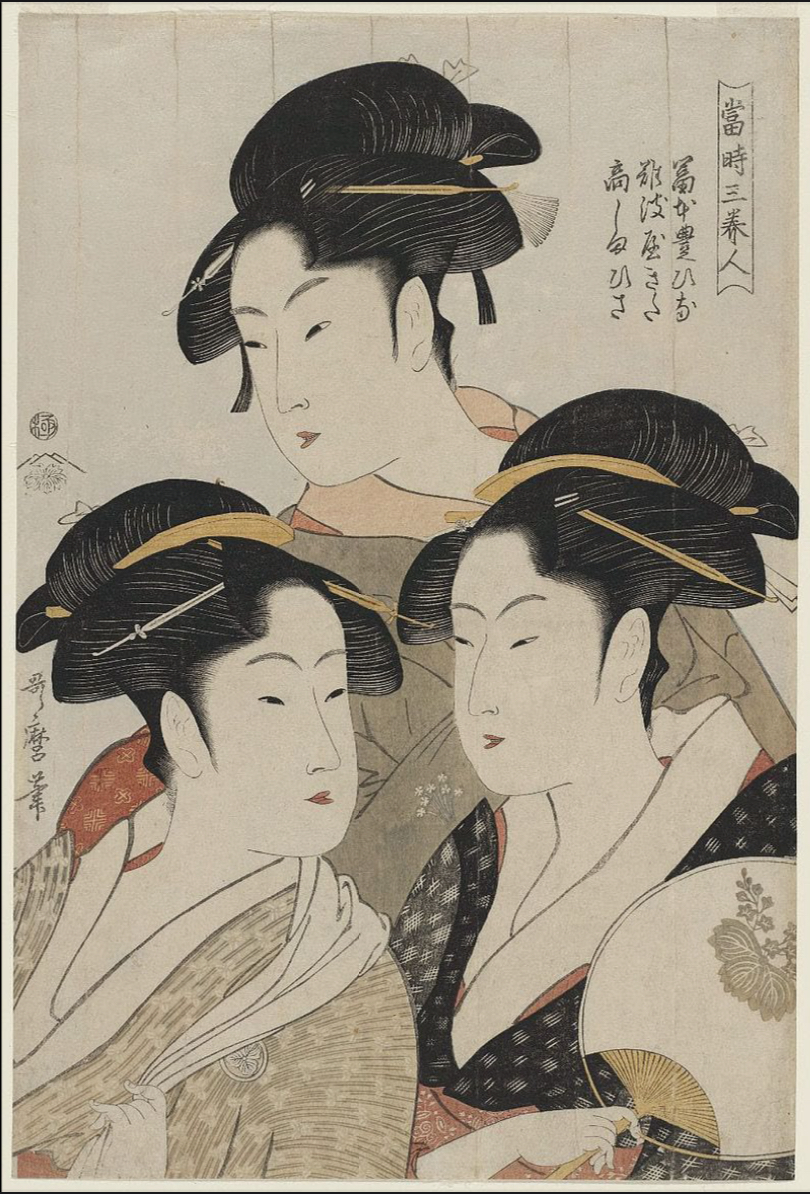

Utamaro, Three Beauties of the Present Day: Tomimoto Toyohina, Naniwaya Kita, Takashima Hisa, 1793, ōkubi-e

Kind of similar to the Heian “line for the eye and hook for the nose”

The women look identical

The three women’s names are identified by their individual flower crests

“oriental beauty”

Utamaro, Woman of the Coquettish type, from the series "Ten physiognomic types of women" c.1791

Shows a close-up view of a woman just out of the bath; although her hair is meticulously piled up, her kimono is carelessly worn and the sash is loosely tied

The background has been rubbed with mica to produce a silvery grey, which highlights the warmth and softness of the fleshtones

His typical beauties are long and willowy and have about them a languid and sensual air (as seen in this painting)

A lot of the appeal of these prints is their sensual nature

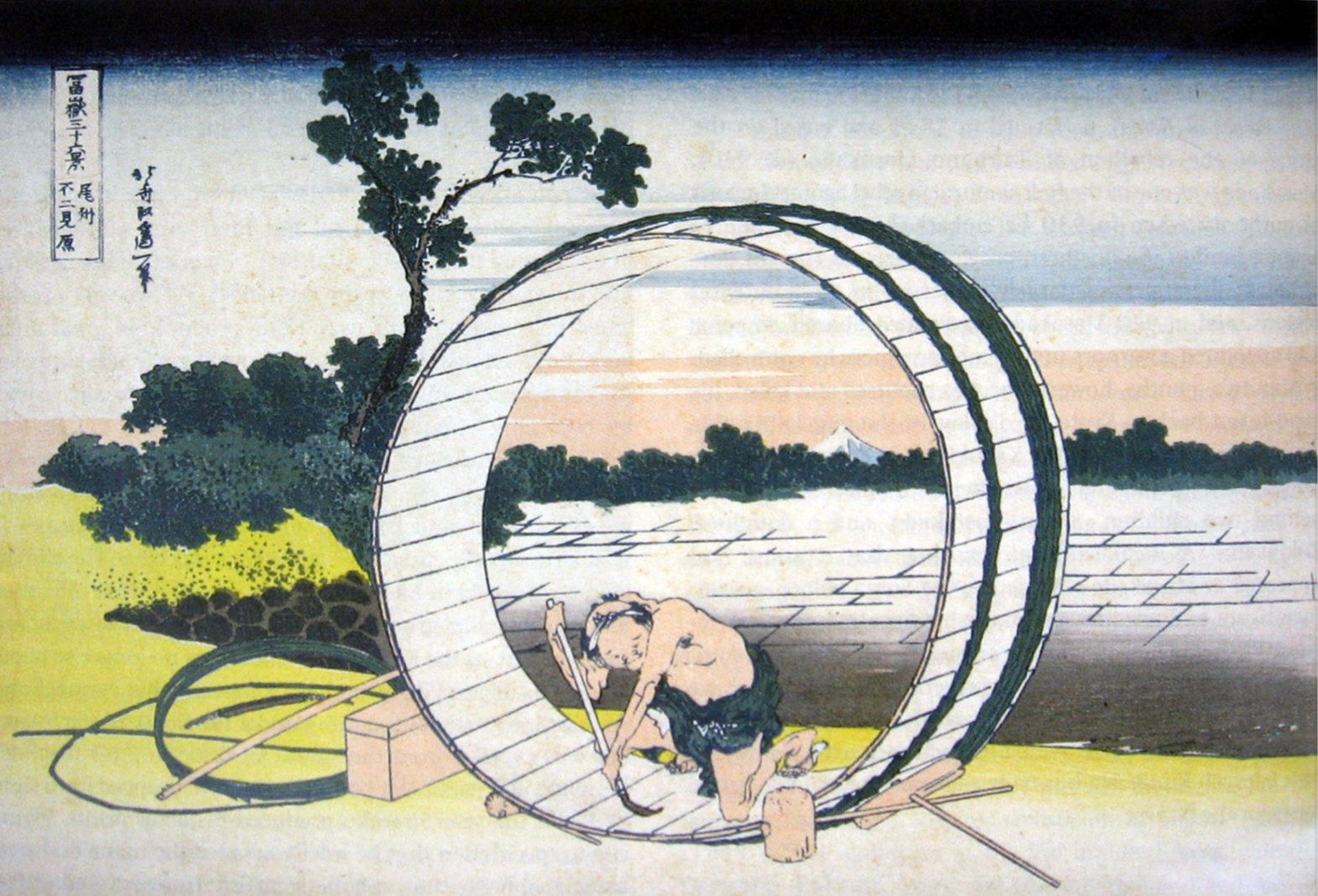

Hokusai, View of Fuji from the Rice Fields in Owari Province (#9), 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, 1830-33

Artists encouraged to travel to these locations in order to depict them

Very local which makes people love it

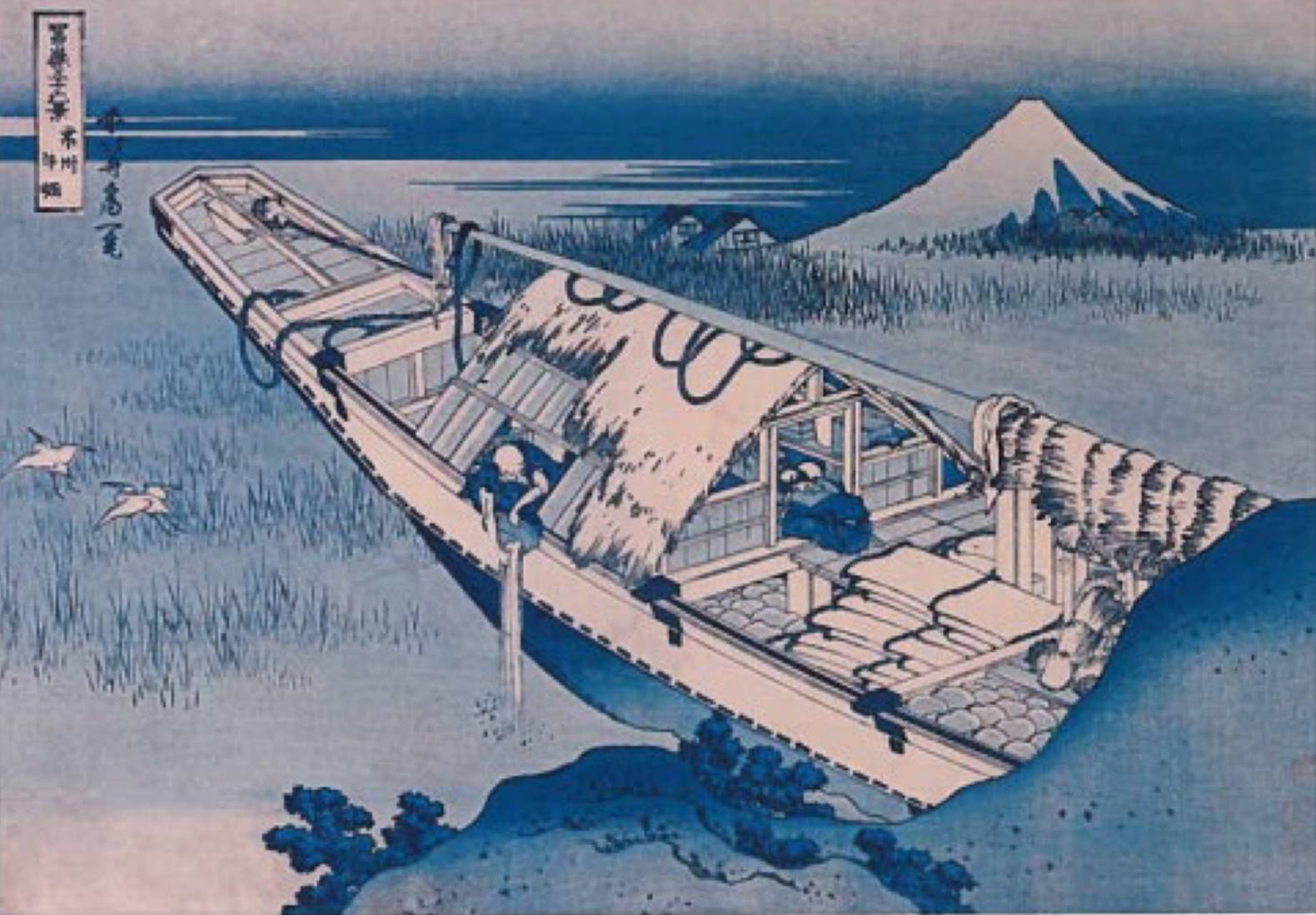

Hokusai, Ushibori in Hitachi Province (#20), aizuri-e, 36 of Views of Mt.Fuji, 1830-33

Aizuri-e: monochromatic blue prints

aizuri-e and Prussian blue

Prussian blue was a European synthetic pigment

Proved suitable for woodblock printing, and it extended the palette of blue hues that had been limited to the organic pigments of indigo and dayflower blue

More vivid and didn’t fade, also viewed as exotic, thus more appealing to the public

Contains Prussian blue

A European synthetic pigment, not organic

The more blue you have in your print, the more appealing it was

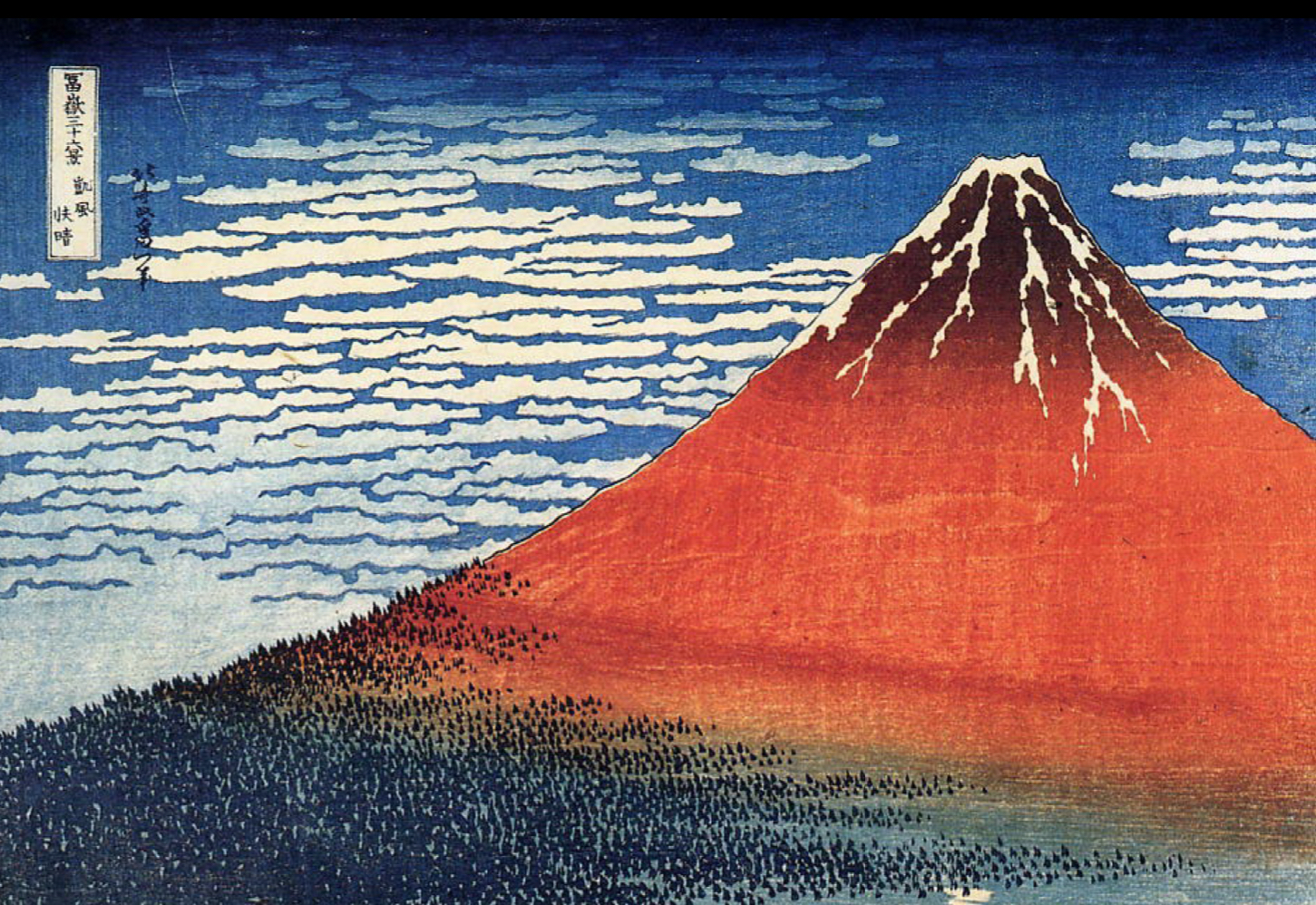

Hokusai, South Wind in Clear Weather (Red Fuji) (#2), 36 of Views of Mt.Fuji, 1830-33

Known for the strong, reddish-brown iron oxide coloration of typical impressions

The southern wind and thin trails of snow are phenomena of late summer

Bands of white clouds drift across a striking blue sky

Its impressions where the sky is lighter, it appears to recede behind the mountain, thus creating a greater illusion of volume in the mountain itself

Hokusai helped make Mt. Fuji become apart of the Japanese national identity, not just the Edo identity

So bold, so monumental, and never seen before

Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (#1), aizuri-e, 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, 1830-33

His most famous artwork

Reveals a variety of block carving and printing techniques

Undulating lines of varied thickness delineate the top of each of a series of waves, while irregular, slightly interrupted patterns of curving lines form the stylized, claw-like crests of the breaking waves

Mt Fuji, with a heavy cap of snow, is silhouetted by a dark grey sky

It's about to engulf three boats of terrified fishermen

An image about Japan facing an uncertain and unstable future during their period of isolation

There was a big fear of invasion by sea

Creates an element of dread and uncertainty

Particularly with the claw-like details of the wave

A hybrid of Japanese and Western art

Commercial appeal

Historical context of the uncertainty of Japan’s future

Looming threat of invasion from the sea by foreigners

Hiroshige, Snow at Kambara (#15), from 53 Stations of the Tokaido, 1833-35

A focus on the people and local customs along the East Coast Highway

Travelers in an evening snow

Strong diagonals

Asymmetrical

Travelers going in different directions

More realistic

Hiroshige, Rain Shower at Shōno (#45), from 53 Stations of the Tokaido, 1833-35

Must be in the summer

echoes/repetition in the background of trees

Repetition of the same motif shows that it has decorative value

Strong diagonals

Diagonals of rain

Diagonals of trees going in the opposite direction

Travelers going in opposite directions

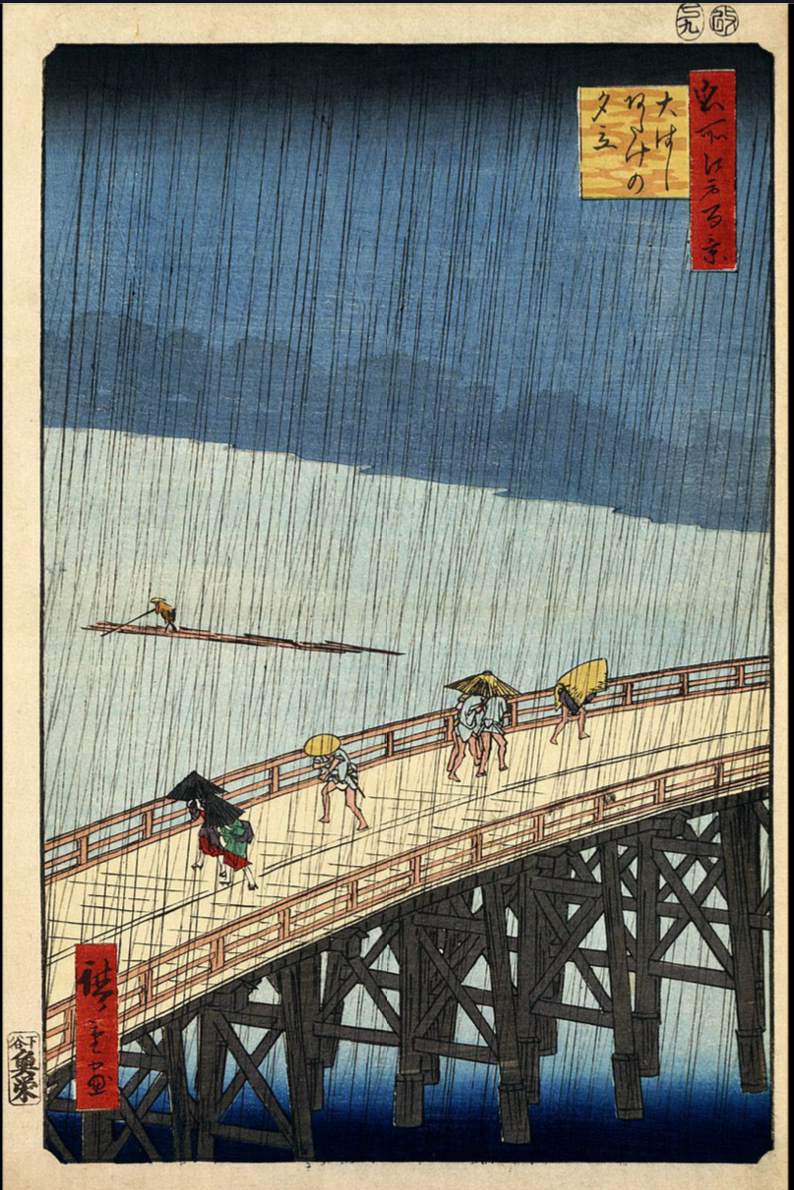

Hiroshige, Rain Shower over Ohashi Bridge and Atake (#30), from 100 Views of Edo, 1848-58

Travelers going in opposite directions

Prussian blue at the top and bottom of the print

Diagonals

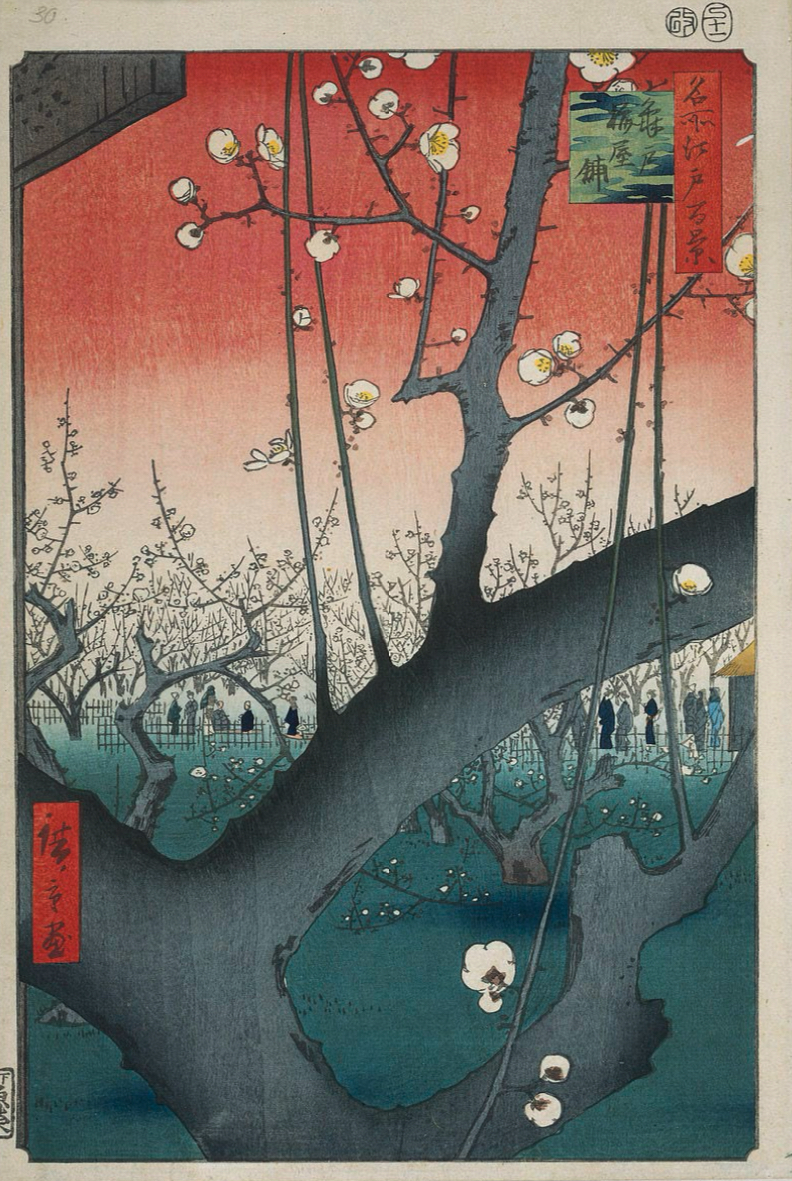

Hiroshige, The Plum Garden in Kameido (#58), from 100 Views of Edo, 1848-58

Strong diagonal

Interesting perspective from the tree

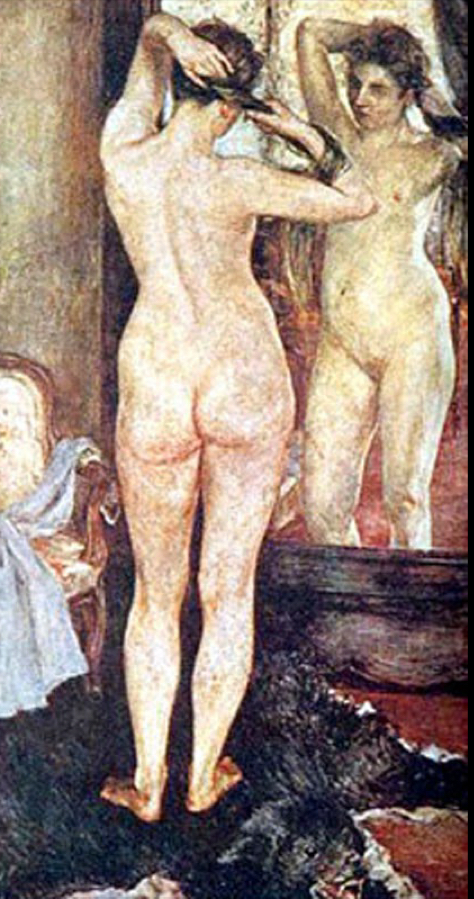

Kuroda, Morning Toilette, 1893, yoga

caused a minor furor by publicly exhibiting a painting of a nude for the first time in Japan

Illusion of the mirror: an image within an image

A very French taste

Scandalous for depicting a fully nude woman

Kuroda, Study for Talk on Ancient Romance (Composition II), oil on canvas, 1897, yoga

Where he attempted “grand scale painting”

It is clear in his mind, that kosoga must involve historical narrative as its subject, and he planned for groups of people posing in a landscape

The subject matter for such a painting should express eternal values of love, peace, or courage, and in this context, the depicted human figures in the painting are best portrayed in the nude, since clothing invariably reflects a particular historical and cultural background

There was strong public opposition to paintings of nude figures

The Meiji government in 1873 prohibited nudity in public

A westernized style on a Japanese ideal of narrative storytelling

Compre: David, The Oath of Haratii, 1784 (L)

Both show a female figure crouching down

Both depict a story/narration

Both are historical paintings

L is a tragic story

When people come back from studying in Paris, they attempt to make a historical painting

Historical paintings are held in the highest regard/respect in Europe

Kuroda, Lakeside, oil on canvas, 1897, yoga

Shows a woman resting by a lake after bathing

An ingenious treatment of late 19th century French composition with the aura of Japan’s unique courtesan-prints

Something new, yet still Japanese

The color palette is very muted, and the brushstrokes are quite visible

Very Impressionist

The woman is Japanese and in Japanese garb

She’s not high class, but still comes across as very confident

Very modern

Nature background

Inspired by yamato-e

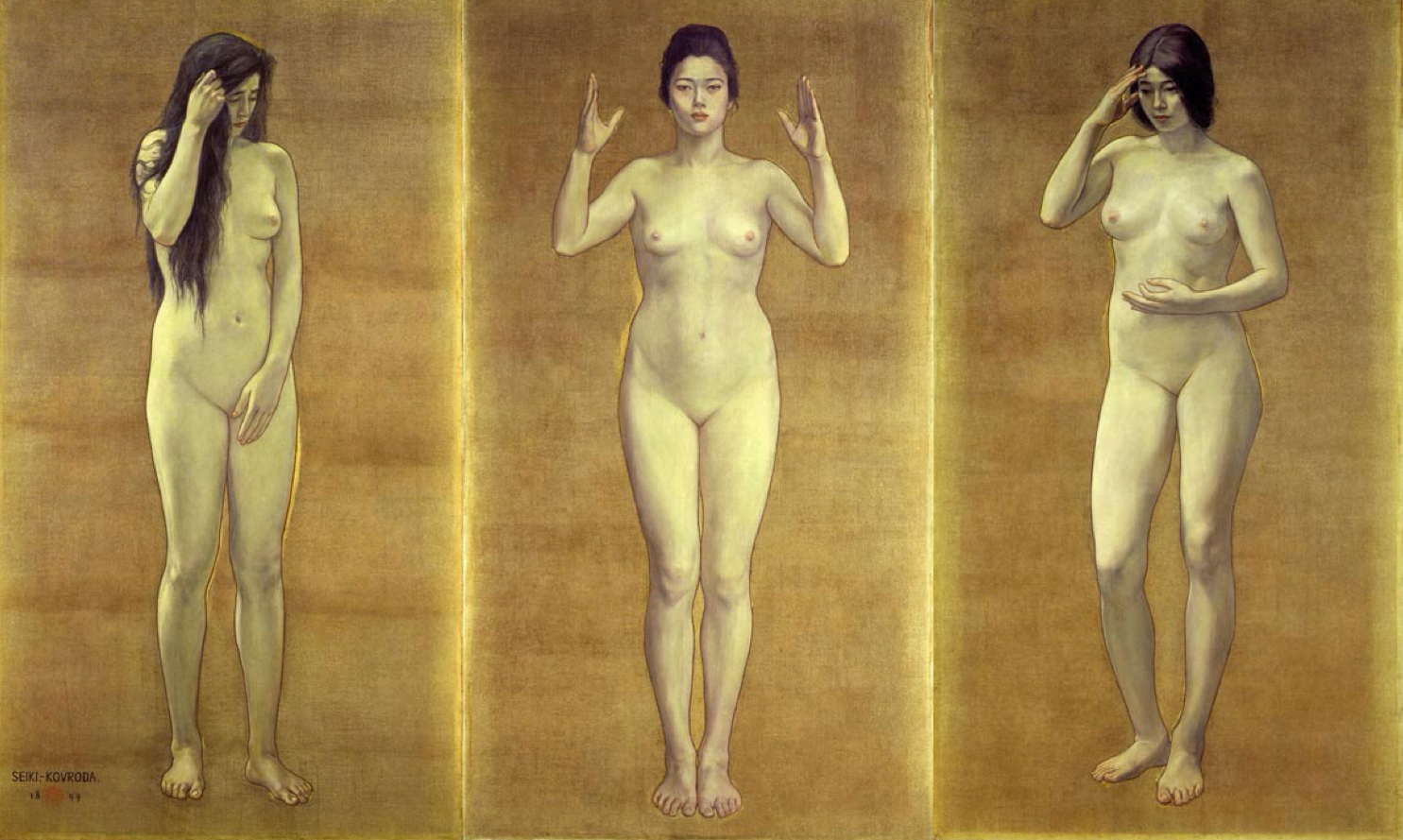

Kuroda, Triptych of Wisdom (right), Impression (center), Sentiment (left), 1899 Oil on canvas, yoga

The key words of Japanese culture

Wisdom

The only figure facing the viewer

The gesture is balanced and rational

Symmetrical

The hair is tied up

Quite Roman, refers to modesty

The woman is more mature

Both Impression and Sentiment figures are in a ¾ position, turned facing towards the middle

Sentiment

Has long hair worn down, usually associated with emotions

Similar to how the Princess Nyosa in Tale of Genji wears her hair down

A very emotional response

Similar in posing to Greek sculptures

One hand is in her hair

The three nude female figures is similar to the Three Graces in a 1st century fresco at Pompeii

Thus, the triptych is quite western

The hairstyles are different

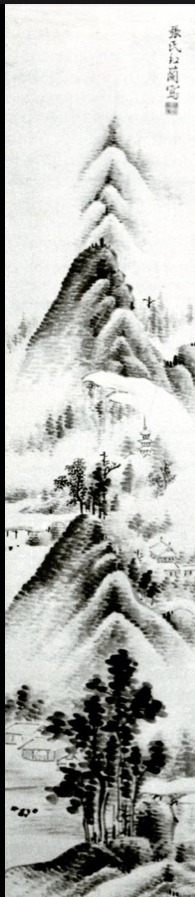

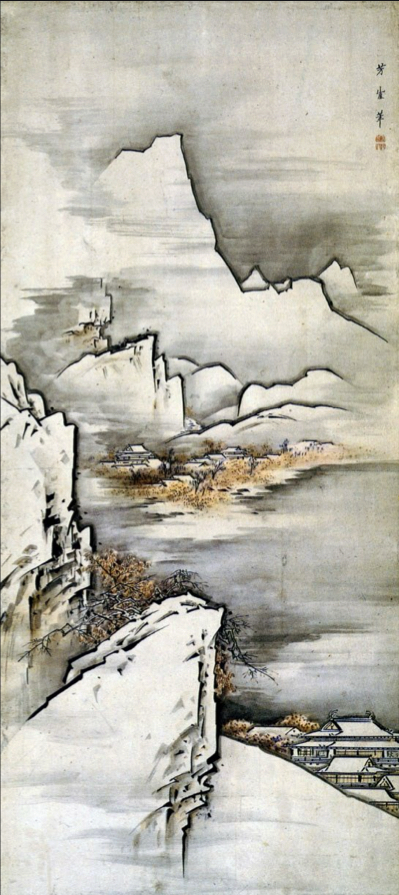

Hogai, Landscape in Snow, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, Meiji, 1867

A Kano school traditional landscape painting

Made before he met Fenellosa

Similar to Sesshu’s Landscape of four seasons: Winter

Hogai, Eagles in a Ravine, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, ca. 1885-86, Nihonga

Considered the first Nihonga painting

A Japanese/traditional subject

Western techniques

The white, flat, stripe is a waterfall

Kinda abstract

Very naturalistic

The detail of the eagle’s feathers almost creates a pattern that echoes the Rinpa school

A mix of so many elements (Chinese, Japanese, Western, Modern, Traditional styles)

There’s a small diagonal of the top of the trees that ties the eagle on the left to the eagles on the right

Hishida, Fallen Leaves (Ochiba), pair of 6-panel screens, mineral pigments on paper, 1909-10, Nihonga

Combines Western realism with the poetry of space: trees seem to recede into an all-pervading mist, losing definition

Western linear perspective: there’s a clear foreground and background

Criticized for experimenting by not using line drawing

A clear and tangible light source

More western/modern

to some degree are related to the Kano school

repeat the same motif: trees

From Rinpa school

Very detailed

more of an observation of the trees/is more scientific and realistic

Bakusen, Abalone Divers (Ama), 1913 color on silk, pair of six-panel folding screens

Nihonga

The subject of half nude women is inspired by Western art

Japanese format of 6-panel screens

Depicts indigenous women fishing in the old fashioned way

Differs from the modern mass farming techniques that was popular at this time

The divers didn’t wear any clothes/protection whereas modern divers wore diving gear

Rinpa style of large/flat surfaces of color

Usually primary colors: blue, red, yellow

The subject itself derives from ukiyo-e eortic imagery while the social significance of labor is stressed by the figures’ activities

The figures on the right screen are shown at work, while the women on the left screen enjoy rest

Reminiscent of printing techniques are the glistening background covered with mica powder, the forceful colorism of the women’s brownish-yellow skin, the deep blue in their loincloths and in the sea, and the accents of green in the plants on the right screen

Bakusen, Obara Maidens (Oharame), 1927, color on silk/framed, Nihonga

An endeavor to challenge Western masterpieces

The frivolous encounter of naked women with fashionably dressed gentlemen is transfigured into innocuous folklore

The mixing of males and females is consciously avoided

Leisure seems to redeem the hardship of work

The approach is something like folk art

Focus on indigenous women

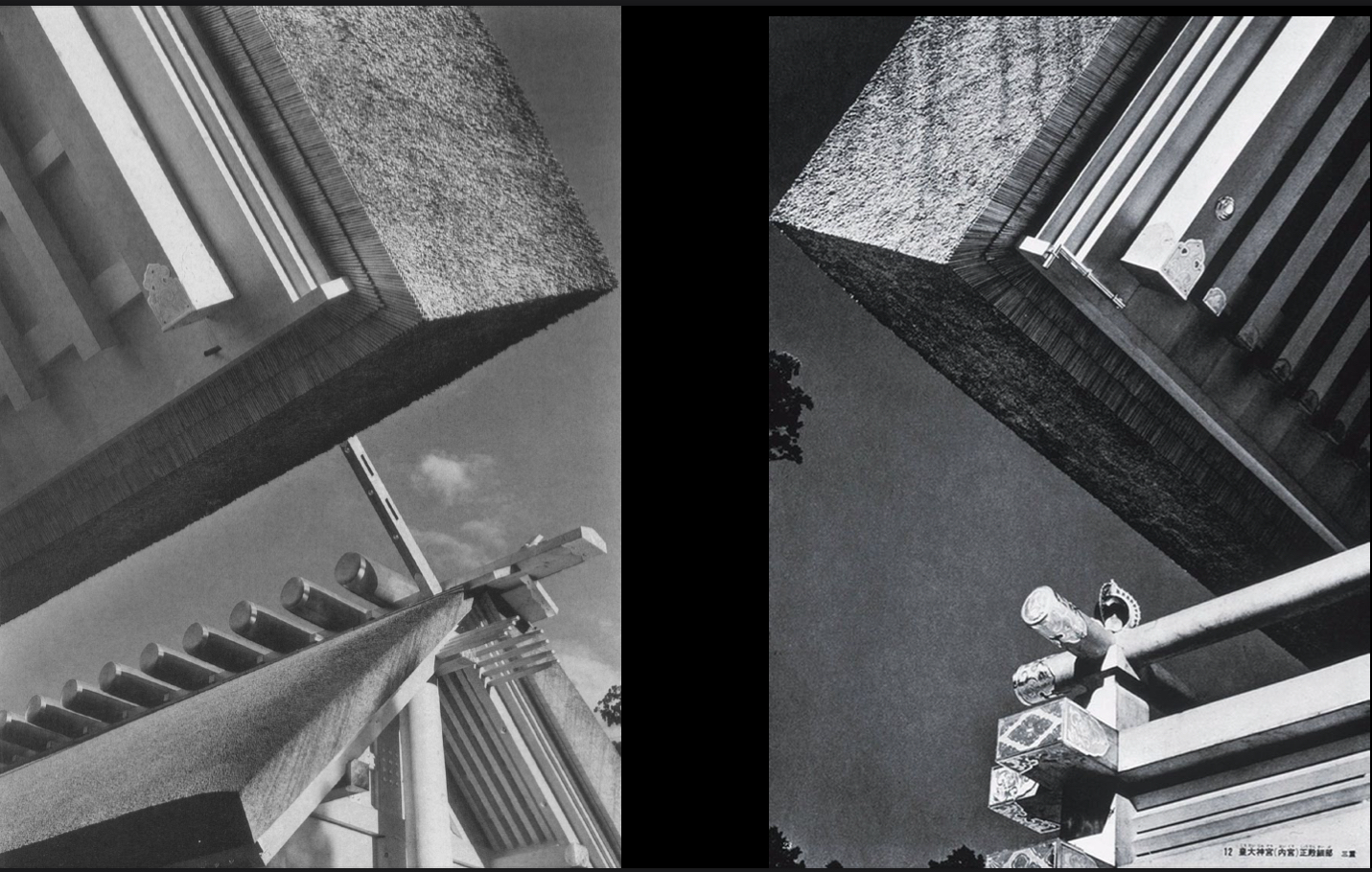

Watanabe, Ise Shrine, set of photos, 1953

These new photographs established an unprecedented level of intimacy and in doing so undermined the religious aura that had always shielded the shrines

At the same time, they enabled Tange and others to elevate the shrine buildings to a new position as the prototype for all of Japan’s later architectural achievements

The photographs of Ise chosen for the book were among the more “objective” images in the series

Intended to serve a “documentary function”

In each photo the camera angle was level with the ground and the camera was placed far enough away from its subject so that the photographs would depict entire buildings rather than fragments

The photos appear to function as tools for conveying information about the architecture rather than as an expressive medium for the photographer

In addition to the comparatively “straight” images, as well as extensive plans and elevations, were also comparatively “abstract” images

Even with few clouds to be seen, several of the photos were highly charged with emotion

The majority of the images were gathered together as a coherent portfolio

This portfolio has a narrative structure, designed to evoke the experience of visiting the shrines

Usually a visit to Ise involves sharing the experience with many others, yet not a single person appears in these photos

Noone is allowed to intrude on the viewer’s reverie

Contributed to the rebuilding of a Japanese identity after WWII

Yoshio made the Ise Shrine modern by changing the view of the shrine by using different kinds of camera angles to showoff certain details

Totally different view of Ise Shrine -> modern

A statement for modernity and modernization

The eye looking at the Ise Shrine is what changed, not the shrine itself

A sort of distorted angle to change something so primitive to something modern

Modern art is free from any reference

Modernism transformed Ise from an imperial object into an aesthetic object embodying moderity

Watanabe, Ochanomizu Station, photo, 1933

His first published architectural photograph

Shot from a disorientingly low camera angle

Made use of dramatic contrasts of light and dark that tend to transform the architecture into relatively abstract geometric forms

The actual train station looks so ordinary

A move away from the pictorial image to a new and modern angle

The new camera angel makes it into something modern and dramatic using light and shadow

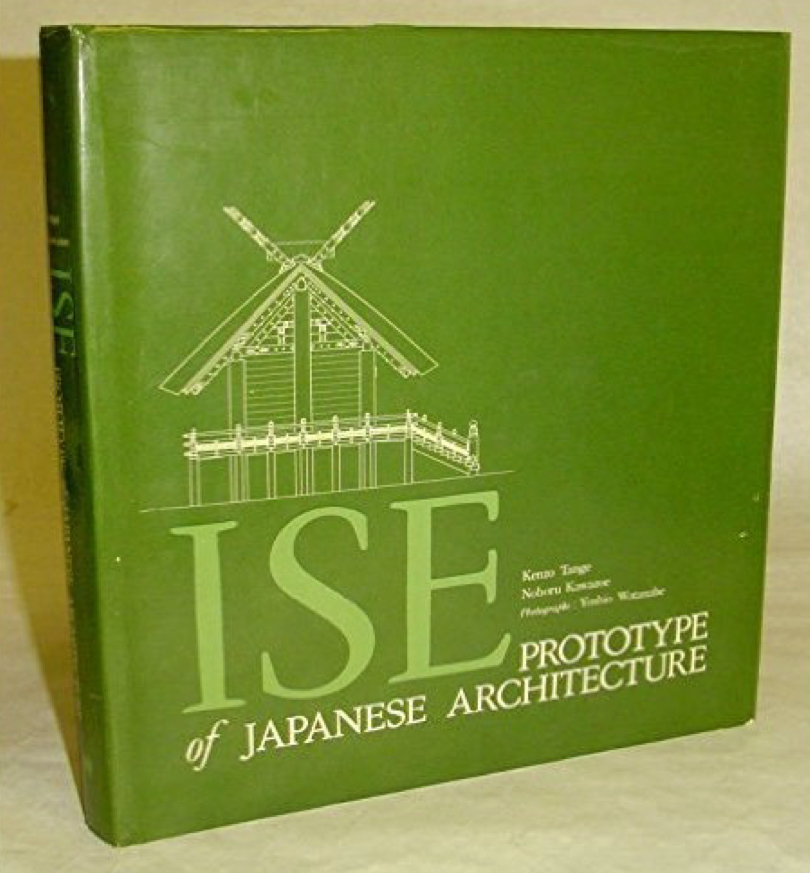

Ise: Prototype of Japanese Architecture Kenzō Tange and Noboru Kawazoe. Photos. by Yoshio Watanabe. Layout and book design by Yusaku Kamekura (MIT 1965)

Promoted the architecture at Ise even more aggressively by claiming a unique position for Ise as prototype for all later Japanese architecture

A highly selective interpretation of the shrine architecture especially well suited to the needs of the modernists communities in Japan and abroad

Emphasized the ancient origins of the shrines

“Nature” is the vehicle that allows Tange to travel into the remote past

Placed emphasis on architectural proportions and the harmony between Japanese architecture and “nature” and in doing so reproduced conventional modernist rhetoric about pre modern Japanese architecture

Tange believed that Ise, as the starting point for all later Japanese architecture, embodied the fusion of the Jomon and Yayoi styles

Argued that both modes of religious practice were still preserved at Ise

The presence of both Jomon and Yayoi cultures contributed to the depth and complexity to the Ise complex

Tang's impulse toward wild mystification in combination with his urge for seemingly more concrete historical argument

With the text, readers could imagine that through Ise they had

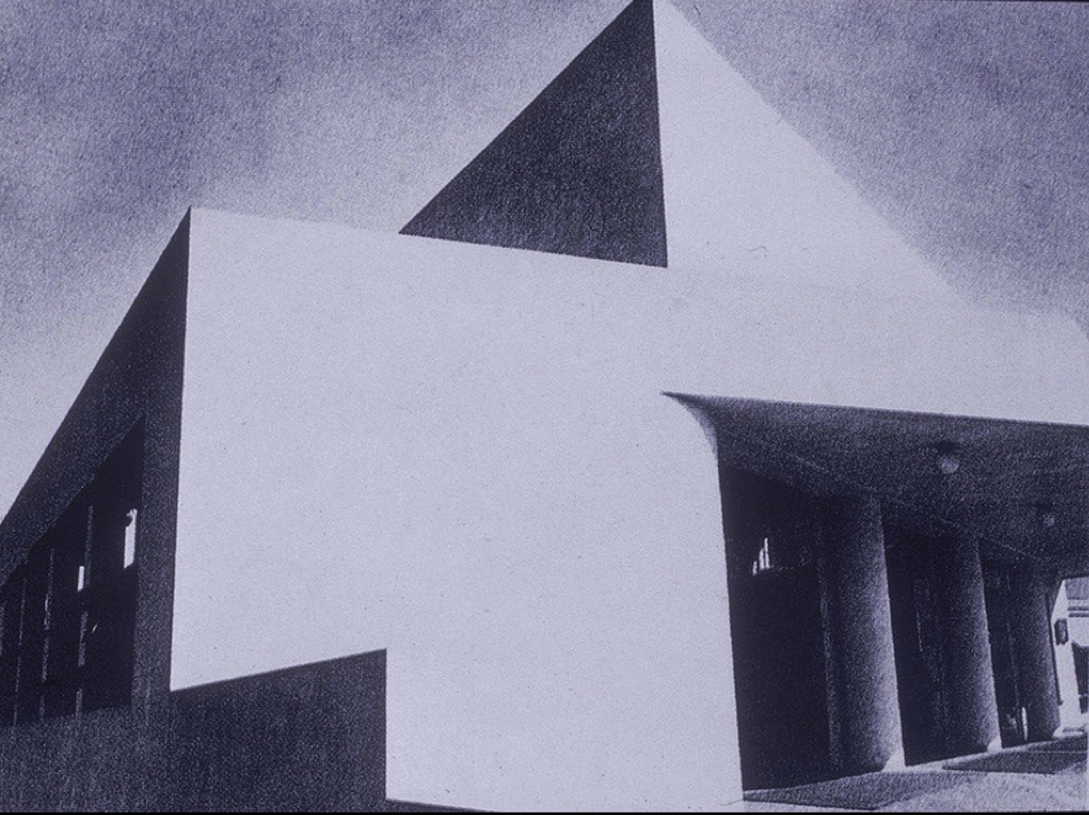

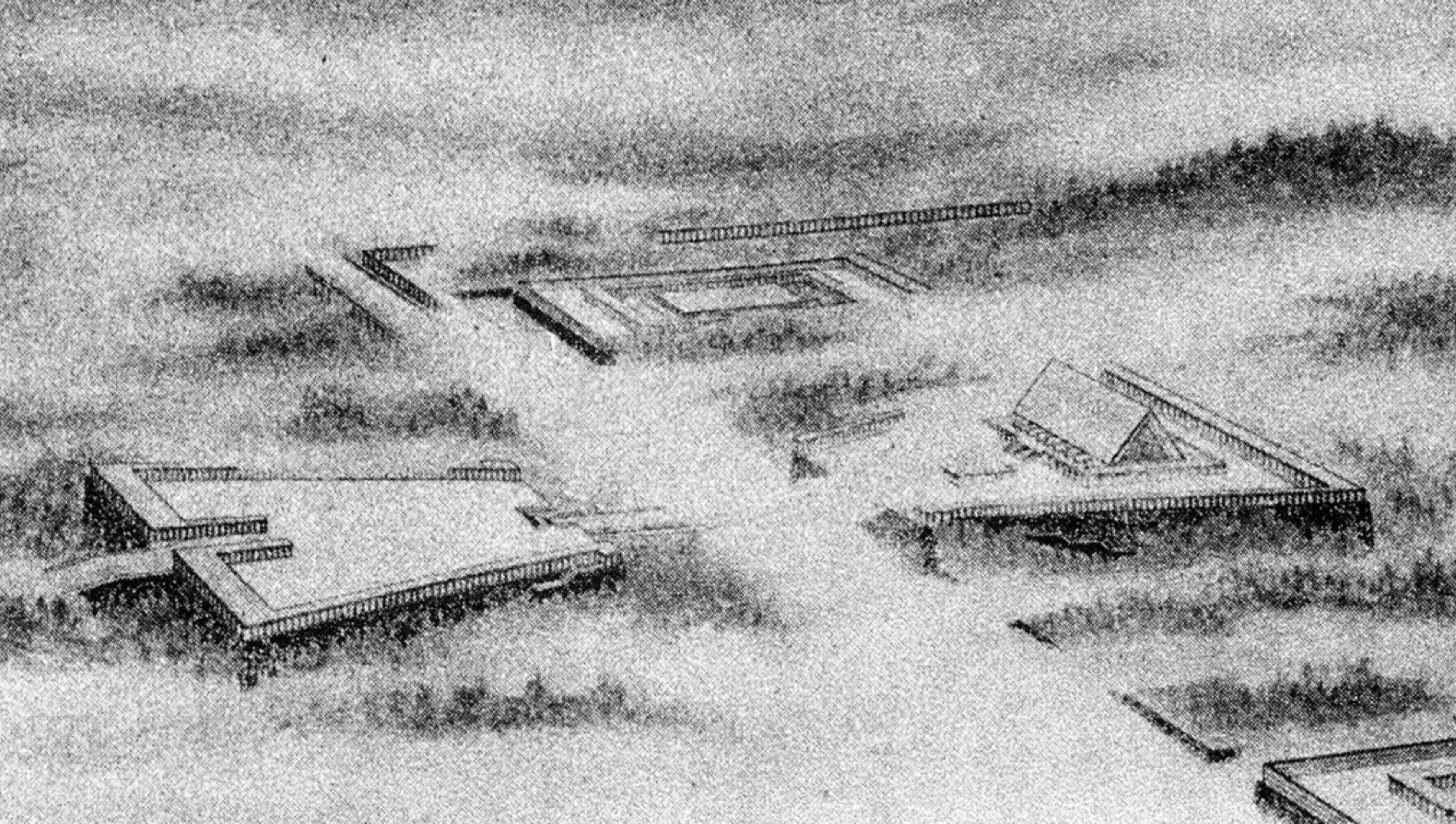

Tange, Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall Competition design, 1942

The ideal of Ise to proclaim Japan’s position as a world power poised to dominate Asia during WWII (assuming Japan won the war)

Making Ise extremely public vs small and intimate

To legitimize the imperial institution

Close tie between Japan’s imperial ambition during the war and Ise

“The ghost of Japanese imperialism”

Lot’s of open space

Tange Kenzo, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, 1955

Lot’s of open space covered in white pebbles, similar to Ise and even a Zen garden

The shape of the structure echoes an ancient grain/storehouse style

Based on a haniwa

Monumental in size and also in its Japaneseness

Very simple, straightforward, clear, very Japanese

Tange United Nations University Headquarters and Trust Building, Tokyo, 1985-95

Very moden: steel frame construction, plate glass, electricity, elevator, reinforced concrete, tall

Also very Japanese/tied to Ise: gabled roof/slanted roof/strong diagonals, the industrial grid lines in the windows echoes the fence of Ise, very symmetrical and proportional with clean lines