BIOL112 midterm test: Genetics

1/76

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

77 Terms

define gene

sequence of DNA that programs cells to synthesise proteins (most but not all do this)

what is an allele

heredity unit, variants of genes, the specific version of a gene that an individual has

may be various options, or only one

these are passed onto offspring, not genes themselves

where are genes and alleles found in eukaryotes

describe the structure of these

on chromosomes in the nucleus of each cell

these are single DNA strands, coiled with associated proteins, and tightly packed into the nucleus

in meiosis, they supercoil into visible structures

100-1000 genes per chromosome, located at specific loci

also contain non-coding DNA regions (which have no associated gene / protein they create)

how do chromosomes differ between species

different numbers

different gene density

characteristically specific for each species

humans have 46 chromosomes, or 23 pairs of homologous chromosomes, which have genes located at roughly the same areas (on the loci)

how do sexual and asexual reproduction differ?

give an example of each

asexual

single parent passes on copies of all its alleles to the offspring

so the offspring produced is genetically identical to the parent

e.g. hydra do budding via mitosis, to produce a clone, which branches off and forms a new individual

sexual

two parents each pass on half their copies of alleles to the offspring

these combine to create a full set of alleles in the offspring (half from each parent)

this creates a genetically distinct individual from its parents

e.g. humans

describe the diploid → haploid → diploid lifecycle for humans

why is this important

all body cells are diploid (2n, 46 chromosomes)

(diploid → haploid) in ovaries and testes meiosis occurs, forming haploid gametes

(haploid → diploid) fertilisation occurs as the opposite gametes fuse

important to keep halving and combining chromosome numbers, so they dont double exponentially

give a brief overview of meiosis

a 2n cell has chromosomes that replicate and join to the replicant (sister chromatid) by the centromere

these then pair up with their homologous chromosome (23 pairs, one from each parent) which is their non-sister chromatid

two divisons then occur to produce 2 daughter cells, twice (overall 4 1n cells)

firstly meiosis I, where homologous pairs seperate, forming 1n cells with replicants

secondly meiosis II, where replicants (sister chromatids) are seperated, forming 1n cells with 1 copy of each chromosome

describe each phase of meiosis breifly (at the level needed for this course)

(prophase I) = chromosomes condense and form tetrads (joined to sister chromatid, and paired with homologous pair), where crossing over occurs (DNA swapped between non-sister chromatids at synapses)

(metaphase I) = tetrads line up along the metaphase I plate (independent assortment)

(anaphase I) = homologous pairs seperate to opposite cell poles

(telophase I / cytokinesis) = the cell divides to form 2x haploid daughter cells (with 1x homologous chromosome in each cell, with its replicant)

(prophase II) =

(metaphase II) = sister chromatids (replicated individuals of homologous pairs) line up along the metaphase II plate

(anaphase II) = sister chromatids are seperated, pulled to opposite poles

(telophase II / cytokinesis) = cell divison occurs to in total form 4x haploid daughter cells (each with one homologous chromosome of the pair, unreplicated)

what is the difference between sister chromatids and non sister chromatids

when are each of these seperated during meiosis

sister chromatids are replicated chromosomes joined to their pair, identical

are seperated in meiosis II (anaphase II)

non-sister chromatids are homologous chromosomes with their pair, non-identical as each comes from each parent (same genes, different alleles - versions of these genes)

are seperated in meiosis I (anaphase I)

name and describe the 3 mechanisms of meiosis that create the origin of genetic variation

independent assortment

metaphase I

tetrads line up along the metaphase I plate randomly, chance puts homologous pairs on the respective side of the cell

therefore when they are seperated (anaphase I), it is random which homologous chromosome ends up in each daughter cell, and the other homologous chromosomes that end up here too

this creates unique combinations of maternal / paternal homologous chromosomes (& unique gametes)

crossing over / recombination

prophase I

when tetrads form, non-sister chromatids (homologous pairs) cross over, which exchanges sections of DNA from where they do so

the amount depends on chromosome size & centromere location (~3 per chromosome)

like in sex chromosomes, doesnt happen very much in humans (X and Y quite different) - may do in different species though

so when homologous chromosomes are seperated and remain with their replicant sister chromatid, they are no longer identical to eachother, or to the original chromosome - they are recombinants

this creates new combinations of maternal / paternal DNA (alleles), in each gamete

random fertilisation

fertilisation

which sperm fertilises which egg is random

this increases genetic variation as gametes are made randomly with lots of variation already, so this further randomises the combnation of alleles that end up in the offspring

describe the Kakii / Poaka example in terms of meiosis

a fully Kakii father + hybrid Kakii/Poaka mother → fully Kakii offspring (99% genetic assignment probability, Kakii on loci of interest)

this is interesting, as the mother had Poaka DNA, so you would assume the offspring would inherit some of this, and form a hybrid too

however, due to the randomness of meiosis, the mother’s egg that was fertilised, mustve had Kakii alleles at all loci, combined with the Kakii alleles at all loci of the sperm (Kakii father) resulting in a Kakii offspring

what was the first model suggested for inheritance

was this satisfactory? why or why not

the blending mode of inheritance

this suggested genetic material found in each parent was mixed up and put into the offspring

this was unsatisfactory

lots of empircal evidence suggested otherwise (e.g. agriculture, horticulture)

and had the large flaw of if true, how would we get back to original genetic traits - theyd forever get to a more and more blended state

what was the next model (currently accepted) suggested for inhertiance?

who suggested this and when

what were the 4 points of this

the particulate mode of inheritance suggested by Gregor Mendel, 1865

suggested that parents passed on discrete heritable units, to offspring, which retained seperate identities (but both make up the offspring’s genetics)

alternative versions of genes (heritable units / alleles) account for variation in heritable characters

organisms inherit 2 alleles for each character, 1 from each parent

for individuals with 2 differing alleles, dominant alleles determine the appearance (phenotype), while recessive alleles have no noticeable effect

2 alleles for each character seperate during gamte formation, so end up in different gametes (=law of segregation)

what was Mendel’s background, and what was the state of science knowledge at that point

he was a monk with lots of time and money, so was able to test ideas about inheritance using an innovative quantitative experimental approach

at this point in time, genes were unknown, how these linked to chromosomes / DNA was unknown, and it was unknown that chromosomes were made of DNA

he originally sought to experiment on bees, but changed to garden peas for his main research into inheritance

what was Mendel’s initial experimental approach

why did he choose garden peas

he used plants, specifically garden peas, to study inheritance as he could strictly control crosses, by manually dusting pollen from the stamen, onto the carpel - so he knew which parents produced which offspring (and could test traits of interest)

plants have many offspring, and short generation times (lots of data to study, provided quickly)

garden peas also had naturally occurring variation (characters / heritable features varying between individuals) that had a manageable number of options (traits / variants of each character)

purple / white flower colour, yellow / green peas, round / wrinkled peas, inflated / constricted pods, green / yellow pods (and so on)

what did Mendel hypothesise when testing the blending mode of inheritance

what did he find

and how did this help him come up with his new model (particulate mode of inheritance)

if the blending model was correct, all offspring of purple x white flowers would be pale purple, and white flowers would not reappear

however, he found that white flowers could repappear in offspring F2 generations, allowing him to deduce the particulate model

he called these traits “heritable factors”, so he knew the concept of a gene, and how these controlled characters, but not a whole idea (heritable unit = gene, heritable factor = allele)

he did a quantitative approach with many crosses, and found a 3:1 ratio of the traits over all the characters (in F2 generations), which he went on to use as evidence for his model

but he also used this to name traits dominant / recessive

what was Mendel’s Law of Segregation

at the locus for a gene on a chromosome, alleles are located

in gamete formation, these alleles seperate (Segregate) when forming each haploid gamete, so they only have 1 allele for each gene

then in fertilisation, opposite gametes with 1 allele each fuse, so the offspring has 1 allele from each parent

this told him important ideas about dominant / recessive, and the fact that alleles can still be in the genotype without being visibly expressed in the phenotype

what law informs Punnett Squares

what is a Punnett Square

law of segregation

as it shows all possible combinations of alleles in offspring, when segregating them, from crossing genetically known individuals

alleles are denoted different letters

homozygous individuals have identical alleles (AA, aa)

heterozygous have different alleles (Aa)

phenotype vs genotype

phenotype

the genetic trait observed visibly, at the level of the observer

so we can define this level as we choose, organism / biochemical / molecular - which may produce different types of dominance for these alleles in the genotype

e.g. complete dominance applies for Pea Flower colour at the organism level, but incomplete dominancne applies at the biochemical level, as intermediate enzyme activity is occurring (half)

genotype

all the alleles within the individual

how do genes and alleles function in DNA

describe using the Pea Flower Colour example

genes may encode proteins / switch on enzyme pathways / switch on or off chromosomes

alleles are different versions created by mutation, so may do these actions differently / do them less or more / not do them at all / have no change

e.g. pea flower colour

at the loci on the chromosome for flower colour gene, the alleles (white and purple) have the same nucleotide sequence except the first pair (C vs A)

the purple colour allele codes for / produces a functional enzyme, that helps synthesise purple pigment, and deposit it into flower petals (flowers visibly appear purple)

the white colour allele’s point mutation results in the absense of this enzyme, as the transcription factor in the enzyme synthetic pathway was not switched on

however, even one purple color allele produces enough enzyme to produce enough pigment to make the flower appear purple (so Aa and AA appear the same, despite different allele make ups)

what is Mendel’s Law of Independent Assortment

how did he come up with this

during gamete formation, each pair of alleles segregate independently of other pairs of alleles (for other genes)

he came up with this due to creating new hypotheses when he moved on to look at multiple characters together - he wanted to test whether alleles stay together or not, if one allele influences another

he created punnett squares based upon these, to show expected phenotype counts in F2, using seed colour (yellow / green) and seed coat (wrinkled / smooth)

dependant assortment would have a 3:1 ratio (YR yr stay together)

independent assortment would have a 9:3:3:1 ratio (more possibilities, are individual alleles, as they are hypothesised to seperate independently)

his experiments found the 9331, thus he formed this law

define complete dominance

how does this work

provide an example

a gene with alleles that are either dominant or recessive

dominant meaning that when this allele is present, it is expressed in the phenotype even with the recessive allele present (homozygous dominant and heterozygous both produce the dominant trait)

this is due to enough protein being coded for with one allele present (usually recessive is a lack of this protein being coded for), to produce the same effect as two copies present

so a dominant allele doesnt subdue a recessive allele, they have no interaction, it is the pathway between genotype and phenotype where they differ (mutations mean they code differently, most often present / absent)

so we cannot tell the genotype from the phenotype

e.g. Mendel’s Peas Flower Colour (purple = dominant, white = recessive)

what is the idea of a spectrum of dominance

most genes dont have alleles that are simply either dominant or recessive (complete dominance) - it exists on a spectrum

define incomplete dominance

provide an example

a heterozygous individual produces a phenotype in the middle / intermediate, between the two alleles

no dominant / recessive alleles in the system, just different traits between homozygotes & heterozygotes

can tell the exact genotype of the individual from its phenotype

note - still disproves the blending model as original alleles can reappear, blending doesnt exponentially occur

e.g. Red Snapdragons for Flower Colour (red / white, wth a pink heterozygote), due to the red allele coding for pigment deposition, but only one present only produces half (only enough for pink petals)

define codominance

give an example

a heterozygous individual equally expresses both alleles, creating a phenotype of both alleles expressed

no dominant / recessive alleles in this system

e.g. blood types in humans, pA/pB produce different types of carbohydrates on blood cells, i lacks them, homozygous for pA/pB have one type, and heterozygous pApB produce both types of carbohydrates

define “multiple alleles” system of inheritance

give an example

when there are more than 2 alleles possible for a single gene

each individual will only have 2 alleles total

different alleles may show different spectrums of dominance / dominance hierarchies

e.g. rabbits have 4 coat colour alleles (wild type / chinchilla / himalayan / albino), with a dominance hierarchy

what is interesting about the rabbit himalayan phenotype, in the multiple alleles system

this himalayan phenotype comes from an allele that codes for a temperature-dependent gene product (TYR / tyrosinase gene) that only produces pigment in cooler extremeties of the rabbit (Adaptation to cool climates)

also underlies the himalayan phenotype in other animals (same gene product / enzyme produced, with mutations on different areas between species)

what is pleiotrophy

give an example

pleio = more

when a single gene has multiple phenotypic effects

it isnt multiple alleles creating multiple phenotypes, it is simply one allele for one gene, giving multiple phenotypic effects

e.g. gene for huntington’s disease, this certain allele causes the disease, via multiple phenotypic effects (physical, mental, etc)

e.g. gene that controls Pea Flower Colour (purple / white) also controls Axil colour (purple / green) and seed coat colour (opaque / transparent)

what is polygenic inheritance

give an example

most phenotypes are controlled by multiple genes working together, the additive effect of two or more genes on a single phenotypic character (multiple genes impacting the single phenotype)

creates phenotypes / characters that vary along a continuum (quantitative - human skin colour, height) rather than being discrete (categorical - purple or white flower petals)

e.g. human skin colour, multiple genes impact skin colour pigmentation, the combination of alleles result in different melanin skin pigment deposition, causing different skin colours (~300 genes control this, not all pigment-related though)

what is epistasis

give an example

where one gene at one locus, controls what happens at another gene locus (altering the phenotypic expression therefore)

what happens at the molecular level, depends on the system

e.g. Retriever Fur Colour

(black / brown / golden) controlled by two genes (B/b & E/e), B gene shows complete dominance, BB/Bb gives black fur, bb gives brown fur - but if the E gene is homozygous recessive (ee), it doesnt matter what the B locus alleles are, the coat will be golden

this is due to the Mc1r gene (E/e) having the e allele as a loss-of-function mutation, making the gene unable to produce Mc1r to interact with the protein created by CBD103 (B/b gene) - B-defensin, so Eumelanin pigment cannot be deposited in the fur, only Pheomelanin is created (yellow) so only a yellow coat phenotype can be expressed

for Mc1r heterozygous (Ee), enough Mc1r is produced to interact with B-defensin to deposit pigment and create a black/brown coat

what laws and principles do Mendelian Inheritance refer to

do these apply in all systems?

are these accepted today?

law of segregation

law of independent assortment

particulate mode of inheritance

yes still accepted and applying to most systems no matter the complexity (not all, some exceptions - but does not disprove his theories)

how did Mendel get lucky in terms of figuring out inheritance, when he chose to experiment on garden peas (4 ways)

would he have still figured it out if they were different?

all 7 characters for peas showed complete dominance

if not it would’ve been harder to figure out his laws, but still possible to disprove the blending model, as original genes would still show up (e.g. if Snapdragons tested with their incomplete dominance)

only 2 possible alleles for each of the 7 characters

if not he would’ve still been able to figure out his laws, as he likely would’ve chosen characters without multiple (2< alleles), or just crossed individuals with 2 allele types total

genes studied had one phenotypic effect (not pleiotrophic)

just wouldve made it less simple, same ideas likely still figured

the phenotypes studied based on the genes were controlled by these genes alone (not a case of polygenic inheritance / epistasis)

garden peas are hermaphroditic (both gender parts) so have no sex chromosomes (no influence of sex-linked genes etc)

diploid

how does nature vs nurture relate to genetics

give an example

the variation seen in the world is equally due to genetics and the environment (10% each), with the remaining 80% a combination of both

genes control phenotypes, but so do the environment they are in - the extent depending on the species

like in phenotypic plasticity, where a range of phenotypes can be produced by a single genotype, due to environmental influence

e.g. Hydrangea Petal Colour, same genotype can produce different phenotypes based on soil pH and minerals available

e.g. Human Blood Type, environment has little effect on their phenotype, is mostly determined by genes

how do Mendel and Darwin fit together in the history of Evolutionary Science

(1859) Mendel’s findings largely ignored / unseen / dismissed

(1865) Darwin comes up with ‘descent with modification’ and evolutionary theory in Origin of Species, largely accepted, but the mechanisms unknown (natural selection he proposed, was unsupported due to lack of evidence for how heritable variation appeared and was transmitted - no DNA knowledge)

(1900) Mendel’s findings rediscovered, providing an explanation behind Darwin’s theory - explaining how heritable variation is passed from parent to offspring, and supporting natural selection as a mechanism for evolution

(1908) Population genetics were established and focus shifted to inheritance in populations of a whole (allele combnations and genetic crosses throughout)

(1930) genetics and evolution merged with ‘The Modern Synthesis’ theory to explain their linkage, and therefore how evolution / speciation / micro / macro occurs on a larger scale - with variation in genetics (Darwin’s thinking about non-discrete traits, helped us understand different systems of inheritance)

how do Mendel’s laws apply to chromosomes

what theory is this called

when was this realised, and what was the state of science

Chromosomal Theory of Inheritance (late 1800s, early 1900s)

we started to understand how chromosomes acted during meiosis, then realised they belong with genes and inheritance - yet to know that chromosomes were made of DNA however

(Law of Segregation) - two alleles for each gene seperate during gamete formation, due to existing on seperate homologous chromosomes which seperate in Anaphase I

(Law of Independent Assortment) - alleles on genes of nonhomologous chromosomes assort independently during gamete formation, as tetrads line up on the Metaphase I plate randomly, in Metaphase I

what organism was studied to understand chromosomes in terms of inheritance (Genetics)

when

why were they chosen

fruit flies, early 1900s

few chromosomes (4), with diploid-dominant lifecycles

simple sex chromosome system (XY)

could semi-control matings (place individuals of interest into food vials)

single matings produce hundreds of offspring, with short generation times (lots of data to study, produced quickly)

have variation to look at for inherited similarities and differences (mutant phenotypes arisen in the lab, white-eyed mutant vs red-eyed wild type)

variation is simple to look at and distinguish phenotypes (eye colour, body shape, wing length)

small and easy to study

what was interesting about fly Eye Colour gene

what was this a case of

what evidence did this provide for science at the time

who were the scientists involved

a case of sex-linked genes

Thomas Hunt Morgan & Co, crossed White-Eyed males (short bodies) x Red-Eyed females (long bodies), and found the expected 3:1 (red:white) phenotypic ratio of complete dominance in F2

but they realised all female offspring had Red eyes (none White), while males were half:half (red:white)

so they reasoned the gene for Eye Colour resided on the X sex chromosome, so males would only have 1 allele (Y and X not homologous) - therefore only males had the possibilitiy of no dominant Red allele (thus possibility of recessive White-eye phenotype expressed)

note - White eye females could be bred, just not by these crosses, had to use heterozygous female x homozygous recessive male

this provided evidence for genes residing on chromosomes

what was interesting about the fruit fly genes for body colour and wings

what genetics concept did this discover

Wild Type flies had Grey Bodies x Long Wings, double mutant flies had Black Bodies x Vestigial (flightless) Wings - so hypotheses were made about these two genes being on the same chromosome

test crosses were done to investigate, showing the genotype options of the offspring (based on parents of known genotypes), and the ratios of the phenotypes if obeying independent assortment (1:1:1:1 ratio in F2)

however, more parental types were observed than the recombinant types predicted based on independent assortment, which provided evidence for linkage (that these genes are located on the same chromosome thus are inherited together most often, and dont undergo independent assortment)

what is linkage for chromosomes

how do resulting offspring phenotype ratios AND recombinant frequencies, differ?

where the alleles (loci) for two or more genes, are on the same chromosome

they can be seperated and undergo independent assortment, if crossing over occurs between them (resulting in recombinant-type gametes)

if close together, they are likely to be inherited together (resulting in linked gametes) as crossing over is less likely to occur in their small in-between

if unlinked, phenotype ratio is 1:1:1:1 (of parental types & recombinant types) OR if linked but far apart (50% recombination frequency)

if linked, phenotype ratio would differ - the recombination frequency (recombinants / total offspring x 100) would be lower than 50%

what are sex chromosomes

how did they originate

chromosomes that determine the sex of an individual, as they contain sex-determining gene / genes

distinct from autosomes (other chromosomes that hold most genes)

differ in number and combination for sex-determining, depending on the species

resulted from supressed recombination between one autosomal pair of chromosomes, around a sex-determining locus, due to adaptative advantage of these genes being inherited together

how do human sex chromosomes work

what organisms share this system

how did the distinct X & Y originate

XY system, XX produces females (homogametic sex) while XY produces males (heterogametic sex) - so sex is determined whether the sperm has X or Y (haploid gametes mean they each inherit X or Y of the ‘homologous’ pair - and female eggs only have X to provide)

shared by mammals and fruit flies (though evolved seperately)

X & Y originally looked the same, but Y lost genes unnessesary for sexual reproduction, so got smaller over evolution (advantageous to have just the sex-determining loci)

some XY systems may have more similar XY chromosomes, simply means they are newer, less time to lose genes

what is the ZW system of sex chromosomes

what organisms have this

birds

opposite system to XY - females have ZW (heterogametic sex) while males have ZZ (homogametic sex) - sex determined by if the egg gamete inherits Z or W

what is the X-0 system of sex chromosomes

what organisms have this

grasshoppers

females have XX, while males just have X - so some sperms simply wont have a sex chromosome, and combine with an X egg to form a male individual (then some will have X, combining to form an XX female)

what is the haplo-diploid system of sex determination

what organisms have this

bees

males are unfertilised eggs (haploid individuals) while females are fertilised eggs (diploid individuals) - so eggs fertilised by sperm become female, and unfertilised eggs become males

are exceptions to sex-determination being based on sex-determining loci on sex chromosomes possible?

give an example

yes!

e.g. Reptiles

some have a ZW system (genetic determined sex), but some have other factors influencing sex determination

this evolved seperately, multiple times, for different species (Rather than inherited from a common ancestor)

some have sex determined by temperature of sand around gametes (temperature-dependent sex determination)

how is sex-determination and sexes of organisms, less binary (distinct males / females) than we think?

provide an example

there are many exceptions and different cases, depending on the species - used to seem an anomalie, but now seen more commonly (likely to provide some evolutionary advantage)

some species have intersex individuals, with characters that dont fit the typical male / female distinction (potentially due to additional / fewer sex chromosomes, or differences in genes (sex & autosomal) associated with hormone control / detection)

some species change sex depending on environmental conditions (advantageous to have only certain sexes, in ceertain conditions)

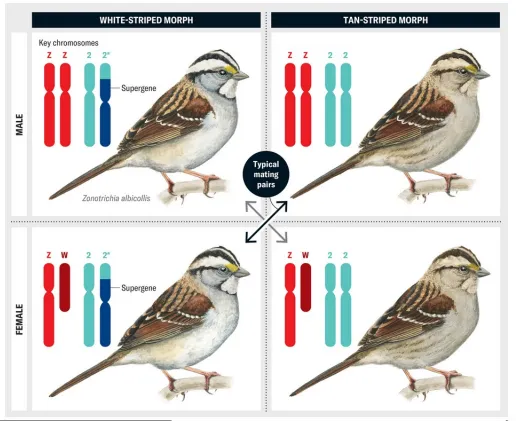

e.g. White-Throated Sparrows

have a ZW system of 2 sexes (male ZZ, female ZW), but said to have 4 sexes as they also have females that look like males (and act more agressive), and males that look like females (and act more docile)

is due to a sex-determining loci on another pair of chromosomes, where inversion has occurred and trapped these genes here (very little recombination as chromosome doesnt match its homologous pair - genes in different regions)

males have this supergene, which gives them male characters, so females that have this supergene act / look more male (but are ZW), while males that lack this act / look more female (but are ZZ)

what are sex-linked traits

give an example

genes that appear on sex chromosomes (that aren’t nescessarily sex-determining)

therefore they are linked with sex / have different inheritance patterns, as sex chromosomes are inherited differently to autosomes, and have little crossing-over (not really homologous, if different sizes like X & Y)

e.g. fruit fly Eye Colour attributed to a loci on the X chromosome (made it likelier for females to have red eyes only, while males had an even mix of white / red eyes)

e.g. colour blindness in humans is majorly determined by the Y-linked gene (recessive trait), so is more common in males (but some other genes come into play)

what is X inactivation

what organisms does this occur in

occurs in female mammals

both females and males have X chromosomes, but male mammals only have 1X chromosome, so all alleles for survival must be on this X (as Y is very small), but then females have 2 sets of all these genes - which may become messy

in every mammal female cell therefore, one X chromosome is randomly shut down (becomes Barr body and bunches up via long non-coding RNA)

this creates a mosaic individual of 2 cell types / resulting phenotypic trait (active maternal X vs active paternal X, may have different alleles at these gene loci being switched on / off) - for heterozgous individuals for specific genes

e.g. cats with Fur Colour gene on X chromosomes, have patchy orange / black fur coat patterns, as when the alleles for this gene are different, different cells across the coat produce either oragne / black fur colour (randomly)

what is interesting about reproductive success in male Zebra Finch?

their sperm has morphology of a head with DNA, midpiece for strength penetration, and tail for speed - affected by different alleles

their sex chromosome system is ZW, so males have ZZ, but these have differing ZA & ZB alleles, corresponding to order of genes, so heterozygous (ZAZB) individuals, have homologous chromosomes ordered completely differently (inversion / supergene) - so during meiosis crossing over largely cannot occur (genes dont match)

ZA alleles have the variants for fast and strong sperm, while ZB has alleles for slower sperm (worse reproductive success)

however, this inversion contains 90% of genes associated with tail and midpiece length of sperm, so in heterozygous individuals these are stuck together - producing the best sperm (as good and bad cannot mix) ZAZB

this means a strong selection against ZBZB individuals (lowest reproductive success) HOWEVER, the ZB allele is maintained and not lost in the population due to heterozygote advantage (at expense of ZBZB individuals with less success)

what is an example of linkage for Garden Peas

did this affect Mendel or not?

Flower Colour and Seed Colour loci were on the same chromosome, but so far apart that linkage was not observed (50% recombinant frequency, the highest)

so it was alike they were unlinked, therefore didn’t affect Mendel’s experimental evidence and observed ratio s

what is the difference between physical and genetic linkage

physical linkage is loci for genes on the same chromosome (so technically linked, but may behave unlinked if far apart)

genetic linkage is where physical linkage occurs close together, so they behave linked (recombinant frequency lower than 50%)

what is the original source of genetic variation

and how?

mutation! - random change in base sequence of DNA

this produces new alleles, if it occurs in a region coding for a gene, and if it changes the resulting protein / gene expression

can be harmful / neutral / beneficial, most often neutral / harmful (and selected against)

is only passed on into populations if occurring in gametic cells however

rare - 1 per 100,000 genes per generation

what is another change in DNA (aside from base sequence mutations) that impacts genetic variation?

define this

chromosome changes, mutations in chromosomes

doesn’t change the allele / generate new alleles, but can change gene order, number, linkage - thus affecting genetic variation & evolution

can be harmful / neutral / beneficial

what are the 3 types of chromosome mutations

(aneuploidy) - change in chromosome number

(polyploidy) - change in chromosome set

(deletion / duplication / inversion / translocation) - change in chromosome structure

what is aneuploidy

how does this occur

provide a real-life example

change in chromosome number, adding or removing an autosome

occurs via nondisjuction (homologous pairs) - meiosis anaphase I, the entire tetrad is pulled to one cell pole, so upon divison the daughter gametes have more / less chromosomes than in the normal set

occurs via nondisjunction (sister chromatids) - meiosis anaphase II, sister replicants fail to seperate, so upon divison some daughter gametes are normal, and some have more / less chromosomes

this changes the amount of chromosomes in each gamete produced, depending on where non-disjunction occurs

e.g. Down Syndrome, an extra chromosome 21 (due to nondisjunction in Meiosis I), causes various varying symptoms / characteristics (like learning disability, significant health issues, characteristic facial features, short stature)

what is polyploidy

chromosome mutations changing entire sets of chromosomes

so resulting individuals have more than 2 sets of chromosomes (triploids, tetraploids, hexaploids) - depending on nature of polyploidy event / opposite gamete fused with

how does the frequency of polyploidy differ in animals vs plants

why?

animals

not common, but has occurred in some fishes, amphibians, a few mammals (e.g. Argentinian rat)

due to animals having complex growth stages and embryo development, and sex chromosomes, so ploid individuals dont often form

also as it can only be caused by meiotic error in gamete-producing cells (asexual reproduction and self-fertilisation far less common)

plants

very common (e.g. wheat, more than half of land plants, agriculturally important plants)

due to simple growth patterns, and often lacking sex chromosomes, so ploid individuals can survive

also as it can occur in both meiotic and mitotic error, as gametes are produced by somatic cells

either non-disjunction in meiosis OR through mitotic error (nondisjunction) affecting the chromosome number of subsequent cells, if these branch off and form flowers, their gametes formed will be ploid (e.g. tetraploid somatic cells formed in mitosis, then form diploid gametes)

also due to many being capable of self fertilisation (both gametes produced on the same plant so more common for a ploid gamete to form a zygote as it doesnt just have to mate with another ploid)

and many capable of asexual reproduction, which would amplify the ploid population

what are the changes in chromosome structure that can occur through mutation

describe these

changes of structure over individual chromosomes, but over large regions of DNA, changing various genes (number, order, and location)

not generating new alleles / diversity, but still have important ramifications for populations

can occur in meiosis or mitosis, will only be passed on if in meiosis

(deletion) removes a segment from the chromosome, resulting in genes removed from it

(duplication) repeats a segment of the chromosome, causing multiple copies of genes

(inversion) reversing a segment within a chromosome, trapping these genes together (linked / supergene), as it prevents crossing over between homologous pairs (regions don’t match)

(translocation) moving a segment from a chromosome, to another non-homologous chromosome - either two way or one directional

what is a real-life example of chromosome mutations in ecology

owl monkeys in South America

captive breeding programmes in zoos aimed to breed diverse individuals from different populations for maximum diversity, but struggled having success

they realised their struggle was due to mating individuals that were too different, as they realised different populations had different karyotypes

one population had undergone a translocation event (which added a large section to another chromosome), which changed the type of gametes formed in meiosis, as usual lining up of pairs was prevented

another population had undergone a translocation of an entire chromosome to the Y sex chromosome, affecting meiosis pairings again, and thus gametes produced

after this realisation, they now avoid breeding individuals too closely related, but breed within populations for maximal success

how may chromosome mutations have been involved with invasive Ragweed

Ragweed was distributed around North America, but when introduced to Europe, flourished and is now found throughout

analysis of population karyotypes found chromosomal changes (inversions) in every invaded European population

this suggests that chromosome inversions may have provided beneficial adaptations to select for when spreading across Europe - potentially due to their supergene ability (linking many genes)

quick recap on DNA structure

sugar phosphate backbone, creating a ladder structure - the rungs are 4 nitrogenous base nucleotides - then this is twisted into a double helix

this is packed into chromosomes

quick recap on DNA → protein process

DNA structure is unwound, and transcription occurs to make a matching (but opposite bases, and U instead of T) strand of mRNA

then translation occurs, as this mRNA is translated from triplets of base pairs (codons), into an amino acid

these amino acids produced from codons on the mRNA, form peptide bonds, forming a polypeptide (protein)

these then form 3D structure, and form functional proteins

what is the universal code

what does it mean that it is ‘redundant but not ambiguous’

the code of base triplets (nucleotide codons) that translate to amino acids (the 20 that form life)

is redundant meaning that multiple codons / triplets can form a certain amino acid

is not amibguous because only certain codons / triplets can form certain aminos

how do base sequence / point changes affect protein production

what are the ramifications for populations

they can change the resulting amino acid coded from that triplet of nucleotides (missense mutation), which changes the interactions / bonds formed between the aminos in a protein’s 3D structure - thus changing its function

this can result in changes in the organism (e.g. new allele produced, as this gene now does a new thing), increasing variation, which can be involved with evolution thereafter

can also induce stop codons (mutation results in triplet now being read as stop), which results in more drastic changes (full protein not created) - often leading to a dead individual (non functional protein)

these mutations can be silent, as redundancy of the universal code means that often changing a single nucleotide base won’t change the amino formed (multiple triplets code for each amino)

most are silent, and retained within populations (not adapted for or against)

why are point mutations most often silent

redundancy of the universal code - multiple codons code for the same amino, so a base change may not change the amino

DNA is mostly non-coding regions (98.5% of human genome) - these are introns which are spliced during transcription processing (only the exons read and transcribed to proteins)

so most point mutations occur here, where they are silent, as these regions dont code for proteins

what is a real-life example involving a point mutation

sickle cell disease

normal red blood cells (Hb AA - homozygous dominant) are plump (haemoglobin made of 4 protein subunits, coming together into a particular structure), suiting their role at carrying oxygen around the body, via blood vessels

individuals homozygous recessive for that gene (Hb SS) have sickle-shaped red blood cells, creating ‘hooks’ that get stuck to eachother, creating fibres in blood (very painful as blood vessels are tiny and become jammed), and glob up subunits so they are bad at carrying oxygen (cannot do their role)

this is due to the S allele, being created from a single point mutation in haemoglobin DNA, changing a CTT → Glu sequence, into a CAT → Val sequence

why can sickle cell disease reach frequencies as high as 20% in regions of Africa, despite its harmful effects (and therefore the assumption of it being selected against)?

what is this an example of?

due to heterozygous advantage

being heterozygous Hb AS for haemoglobin (red blood cells) results in haemoglobin proteins produced as normal for half, while half are sickle shaped (codominance) - so individuals can survive as they have some normally-functioning hameoglobin protein red blood cells produced

they simply have the sickle cell TRAIT which may be harmful at low blood O2, but not normally

this provides an advantage because the pathogen for Malaria (more common in these African regions), which invades blood cells via mosquito transmission, finds it hard to infect sickle-shaped blood cells

therefore this harmful Hb S allele is retained in populations at these frequencies, due to its advantage, and its cross producing normal blood individuals too (the most selected for), at the expense of the ¼ chance production of a Hb SS individual (which has no advantage)

shows that even harmful mutations may have reason to persist in populations

what is the difference between genetics and genomics

what field are these used in

used in conservation

genetics involves the study of few genetic markers, to get information about species and populations

genomics involves the study of many genomic markers, to get this information

therefore looking at individual genes vs whole genomes (piece of the puzzle vs a nearly completed puzzle)

why is genomics beneficial?

does this rule out using genetics?

genetics was all that was available initially, it is still good to use if it can answer the question you want to investigate

genomics has allowed us to provide more evidence alonside genetic data, answer old questions that were out of the scope of genetics, and new questions (but not all require this)

both beneficial for conservation

what are 2 methods of genetic analysis / data used for conservation

describe each

PCR (polymerase chain reaction)

uses a lab version of DNA replication to make many copies of a region of DNA of interest, a 3-step cycle to yield exponential increase (1 → 1 billion within hours)

great for low yield / quality DNA, as it amplifies this target sequence (using primers (manufactured RNA strands) specific to this region of interest)

microsatellites (Genetic markers)

a type of genetic marker, short repeating DNA sequences (e.g. CA (di), CAG (tri), GATA (tetra)

these tend to vary (different number of repeats), having many alleles per locus, with each loci bipaterentally inherited

so works well in populations with lots of alleles (Can effectively look at the amount of variation between each)

what is an example in conservation where microsatellites (genetic markers) were useful

e.g. Albatross parental relations to chicks in the nest

monogamy was known to occur, with extra-pair paternity (unrelated fathers parenting a female’s chicks)

so microsatellites were used to investigate this, to determine if the father was related or not

looking at the microsatellite alleles, the amounts of CAG repeats showed the relation of parents to chicks (Fathers were in fact unrelated, while mothers were related)

this works because of the large number of alleles within these populations (Variation to distinguish between)

what is a method of genomic analysis / data for conservation

SNPS (single nucleotide polymorphics)

this analyses DNA sequences closely to find all differences between samples analysed - as even similar individuals have small differences

produces lots of data, as it uses lots of the organisms DNA (full puzzle vs puzzle pieces of microsatellite genetic analysis), providing greater resolution of the genomes

this is necessary to investigate difficult questions (that are unanswered with genetic markers), e.g. for populations with fewer alleles / inbreeding (Where microsatellites may be unhelpful)

what is an example of SNPS used in conservation, due to the limitations of microsatelitte analysis

and why!

e.g. Karure (black robins) extra-pair paternity

critically endangered (~100) on 2 small NZ islands, and very inbred (all descending from 1 breeding pair)

so they moved females between islands, hoping to increase diversity, and attempted captive breeding / targetted males to mate

however, when looking at parents and chicks, they couldnt determine true fathers just by observation, as the male in the social pair isnt always the father (extra-pair paternity)

so they looked to use microsattelite markers, but due to inbred, their alleles had little variation so often the numbers of repeats were the same anyway (thus unable to determine relation)

using SNPS instead allowed them to look at whole DNA sets to find even small differences, allowing for relation to be determined for all individuals (Vs only some using microsattelites)

this was important to see how introducing new parents, affected population growth (positvely or negatively)

what is an example of SNPS used in conservation, to provide more evidence alongside microsattelite (genetic markers)?

e.g. hybridisation in Kaki

these are endangered black stilts in NZ, at risk due to hybridisation with self-introduced Poaka (another stilt)

microsatellites were used to investigate cryptic hybrids (birds which they couldn’t determine if they were Kaki / Poaka / Hybrids, based on observation alone - like appearingly Poaka /Kaki hybrid, that was really genetically Kaki - by chance had gotten all Kaki alleles despite Kaki x Hybrid parents)

SNPS can be used to investigate individuals further, looking even closer at the DNA to determine even smaller differences suggesting what type of bird they are

they also helped determine that Poaka and Kaki are infact two different species, as they are genetically distinct - showing that hybridisation does pose extinction risk, but not too much

how was genomic analysis beneficial in Project Kakapo 125+

this project kicked off when only 125 Kakapo remained in NZ (critically endangered on an island)

they generated whole genome sequence data for every living bird, providing reference genomes to investigate to help determine why they were endangered, and what could be done to help (e.g. specific genes gave them specific vulnerabilities, which should be minimised in management)

a reason for endangerment was over 50% hatching failure, originally thought to be due to male infertility, but after looking inside unhatching eggs they found evidence of cell divison - suggesting early embryo death was the reason instead

analysis of genomic data can help understand why this happens, what DNA leads to this (possible mutations?)

can also look at associations of genes / alleles and disease vulnerability, to make predictions, and determine which birds are growing on track, and those who are vulnerable (and may need more help)

what is Huntington’s Disease?

how did genetic analysis help treatment of it?

disease caused by a lethal dominant allele that causes death (even with only 1 copy), which may not occur until later in life, where this allele may have been passed onto offspring

before looking at the genetics, facts about inheritance were hardly known

genetic analysis found the gene was on the tip of the chromosome, and looking at the DNA itself, the allele had too many CAG repeats (>35), creating a faulty protein

this was a DNA repair enzyme, which triggered DNA expansion througn faulty repair, causing expression of too many phenotypes - causing the disease’s symptoms

this allowed treatment development targeted at reducing DNA repair (but not too much so that normal repair was inhibited)

what is a genetic or genomic conservation method to determine the sex of an individual, from a DNA sample

PCR!

e.g. Kaki