!! Bulk, Single Cell, and Spatial RNA-Seq

1/40

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

41 Terms

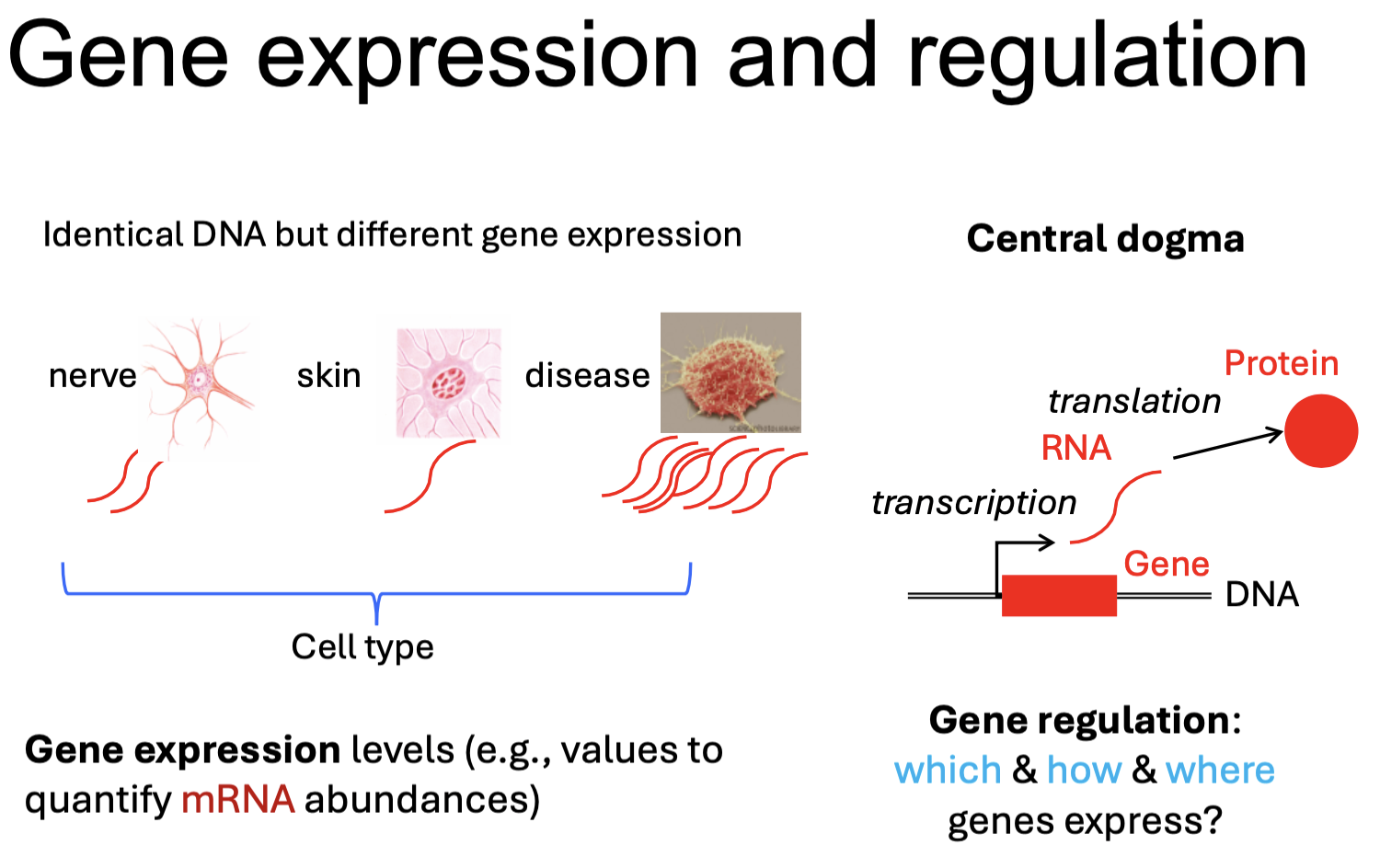

Why study RNA?

RNA is dynamic, capturing more information than static DNA.

RNA is the first quantitative link between DNA sequence and phenotype.

RNA capture regulatory complexity beyond gene sequence.

The transcriptome encodes layers of control not visible in DNA through alternative splicing and noncoding RNA regulation.

Gene expression

A gene is a short DNA section containing instructions for making proteins.

Exons, introns.

Alternative splicing.

Different combinations of exons.

Multiple transcripts.

Gene expression level is the number of gene transcripts produced in an organism or cell.

It’s the process of using DNA information to create RNA and proteins.

Detecting gene expression

RNA-Seq and DNA microarray can be used to profile gene expression.

cDNA (complementary DNA) is used in gene expression studies to detect and quantify gene expression products.

RNA is not stable and can be easily degraded.

cDNA libraries are gene libraries containing only genes expressed in a cell or tissue.

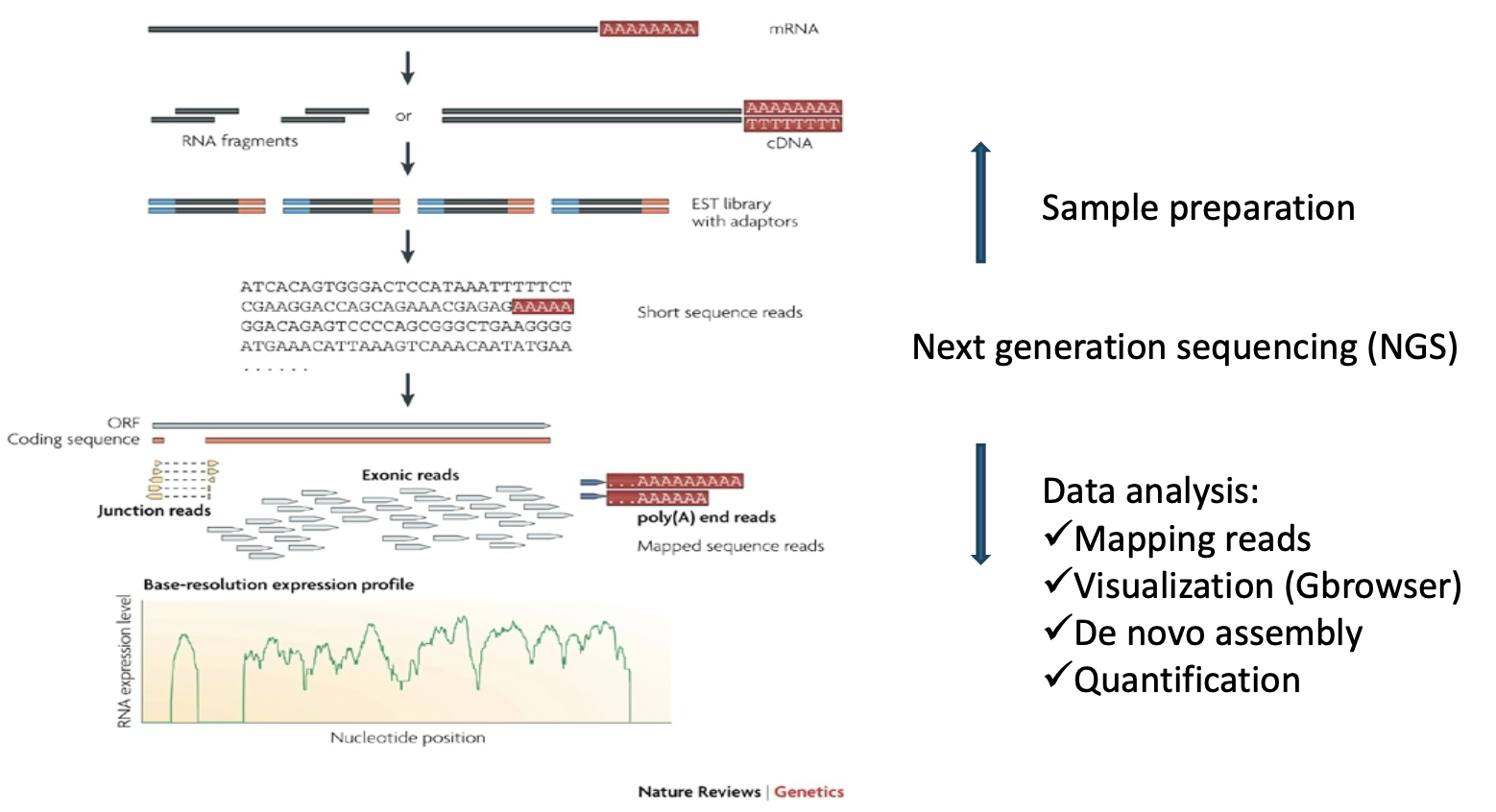

RNA-Seq steps

Sample preparation: Prepares the mRNA for sequencing.

Starting material: Total RNA is isolated, explicitly focusing on the mRNA.

Fragmentation/cDNA synthesis: The mRNA can either be fragmented directly into RNA fragments or be converted into more stable cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

Adapters: Sequencing adapters are ligated (attached) to the ends of fragments, creating a sequencing library.

Next Generation Sequencing: The prepared library is sequenced to produce raw data.

Sequencing: The fragments are sequenced to generate millions of short sequence reads.

Data analysis: The raw sequencing reads are processed to quantify gene expression.

Mapping reads: The short reads are aligned against a known reference genome or transcriptome.

Exonic reads map entirely within an exon.

Junction reads span a splice junction (connecting two exons).

Poly(A) end reads map to the end of the transcript, confirming the 3’ end.

Visualization (genome browser).

De novo assembly: If a reference genome is unavailable, reads can be assembled to build transcripts.

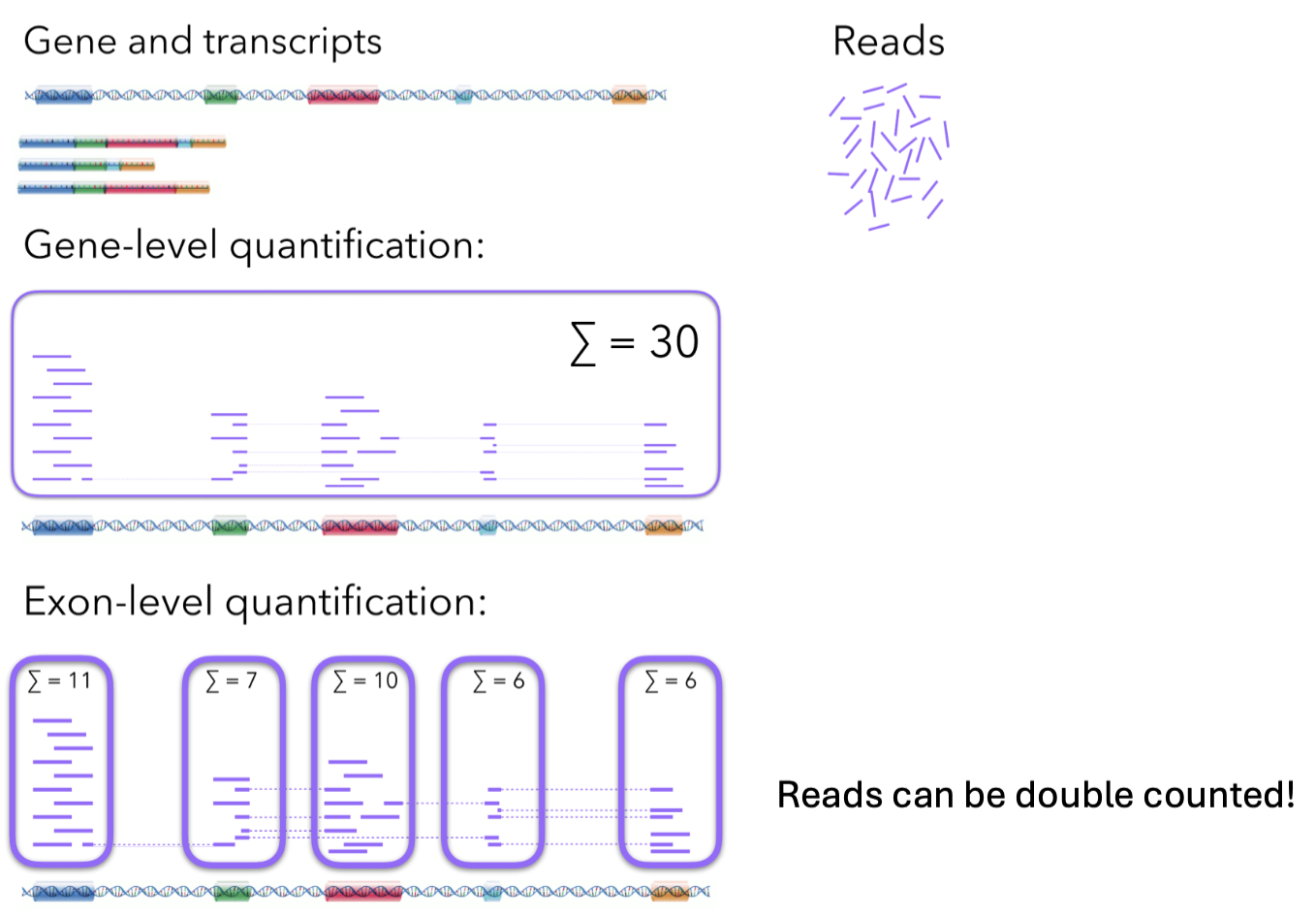

Quantification: he number of reads mapping to a gene or transcript is counted to determine its expression level. The final result is a Base-resolution expression profile, a graph showing the abundance of RNA (read coverage) across the transcript length.

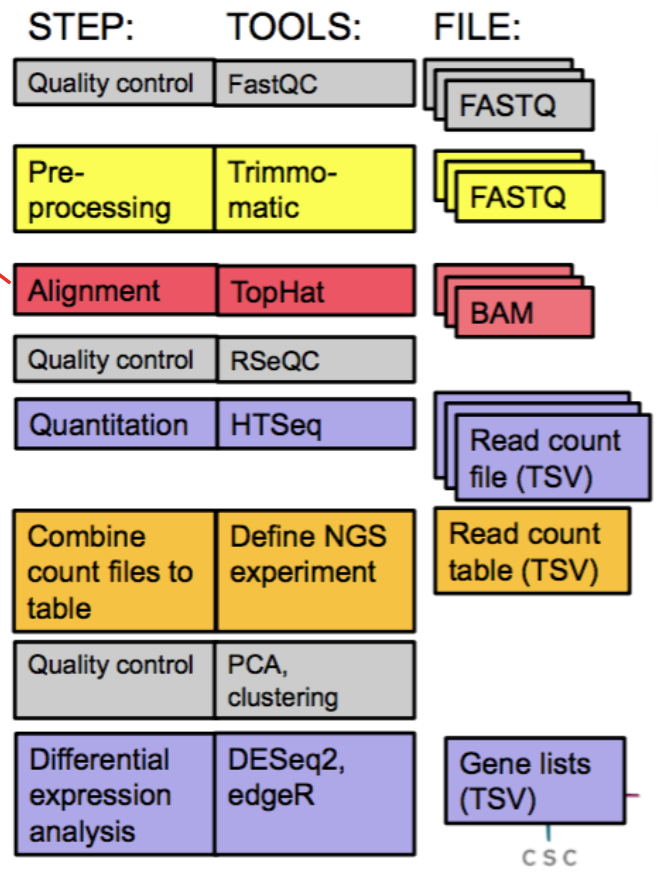

RNA-Seq analysis steps

Quality control sequence output = FASTQ files.

Pre-processing notes: If the reads contain low-quality bases or adapter sequences, you might want to trim or filter them.

Alignment notes: map reads to reference genome/transcriptome; output = BAM files.

Quantitation notes: abundance quantification; gene, exon, or transcript levels.

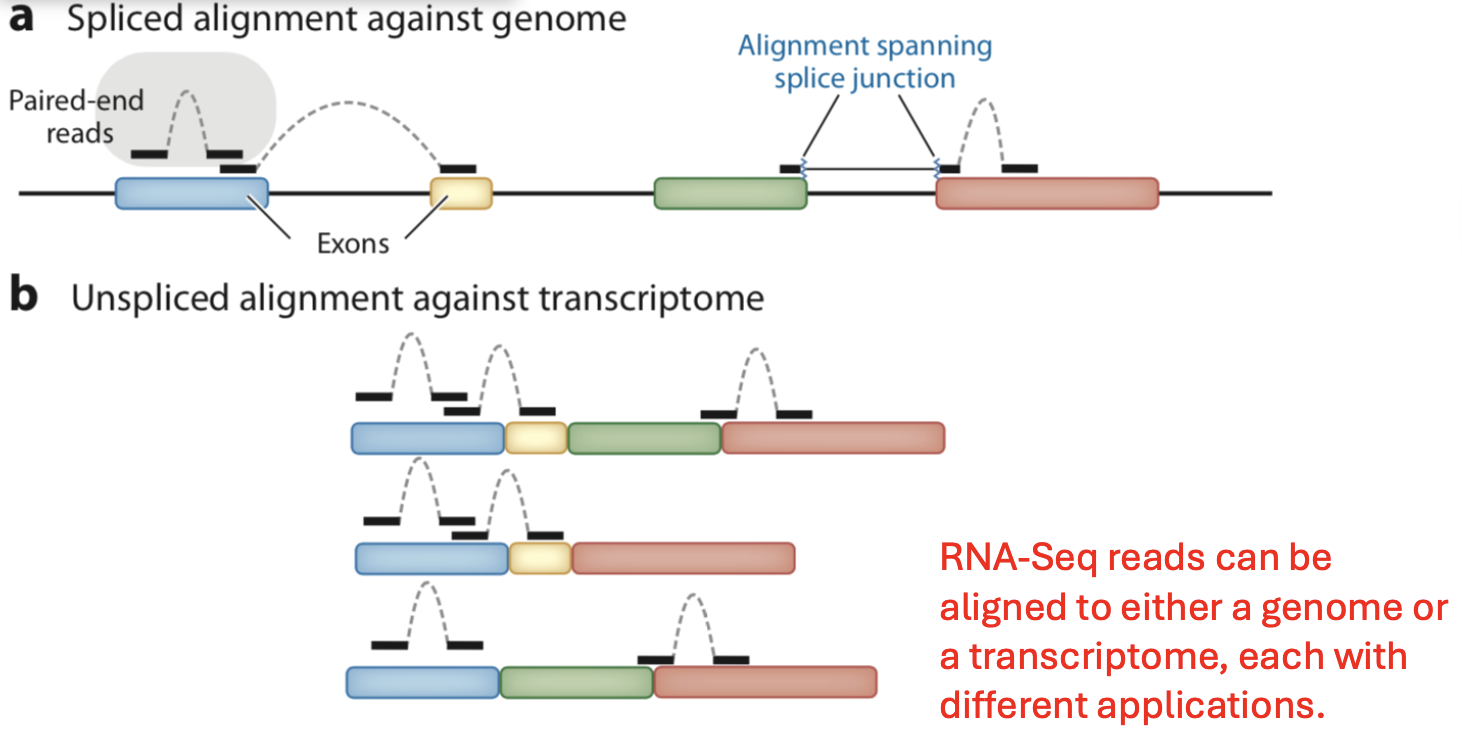

RNA read alignment

Find the position of a sequencing read on the reference genome.

Reads can be unaligned or aligned to more than one location.

A paired-end read will only be counted as one read if both ends align to the genome.

Given a list of transcripts, each read can be mapped to one of the four classes: exonic, partially overlaps an exon, intronic, or between genes.

Why intronic: They are mostly unspliced pre-mRNA or functional non-coding RNAs transcribed from those genomic regions.

Abundance quantification

Raw counts can be biased:

Sequencing depth: Different total numbers of reads between samples.

Correction: Normalizing by total library size.

Gene length: Longer genes have more space for reads to map, leading to higher raw counts even if the gene's concentration is the same as a shorter gene.

Correction: Normalizing by transcript/gene length.

RNA composition: A few highly expressed genes can take up a significant fraction of the total reads, making other genes appear to have lower expression than they really do. This affects the comparison between samples.

Correction: Using specialized between-sample normalization methods.

RNA-seq normalization methods

Within sample:

Required to compare the expression of genes within an individual sample.

It can adjust data for two primary technical variables: transcript length and sequencing depth.

Counts per million (CPM).

FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped).

Transcripts per million (TPM).

Counts per million (CPM)

The number of raw counts mapped to a transcript, scaled by the total number of sequencing reads in your sample, multiplied by a million.

It normalizes RNA-seq data for sequencing depth but not gene length.

Not yet ready for comparison of gene expression.

FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped) & RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped)

FPKM = paired-end data.

RPKM = single-end data.

Correct for both library size and gene length.

Good for comparison of gene expression within a single sample, but not for across-sample comparison.

Transcripts per million (TPM)

Represent the relative number of transcripts you would detect for a gene if you had sequenced one million full-length transcripts.

Correct for both sequencing depth and transcript length.

Suitable for within-sample comparison of gene expression, but not for across-sample comparison.

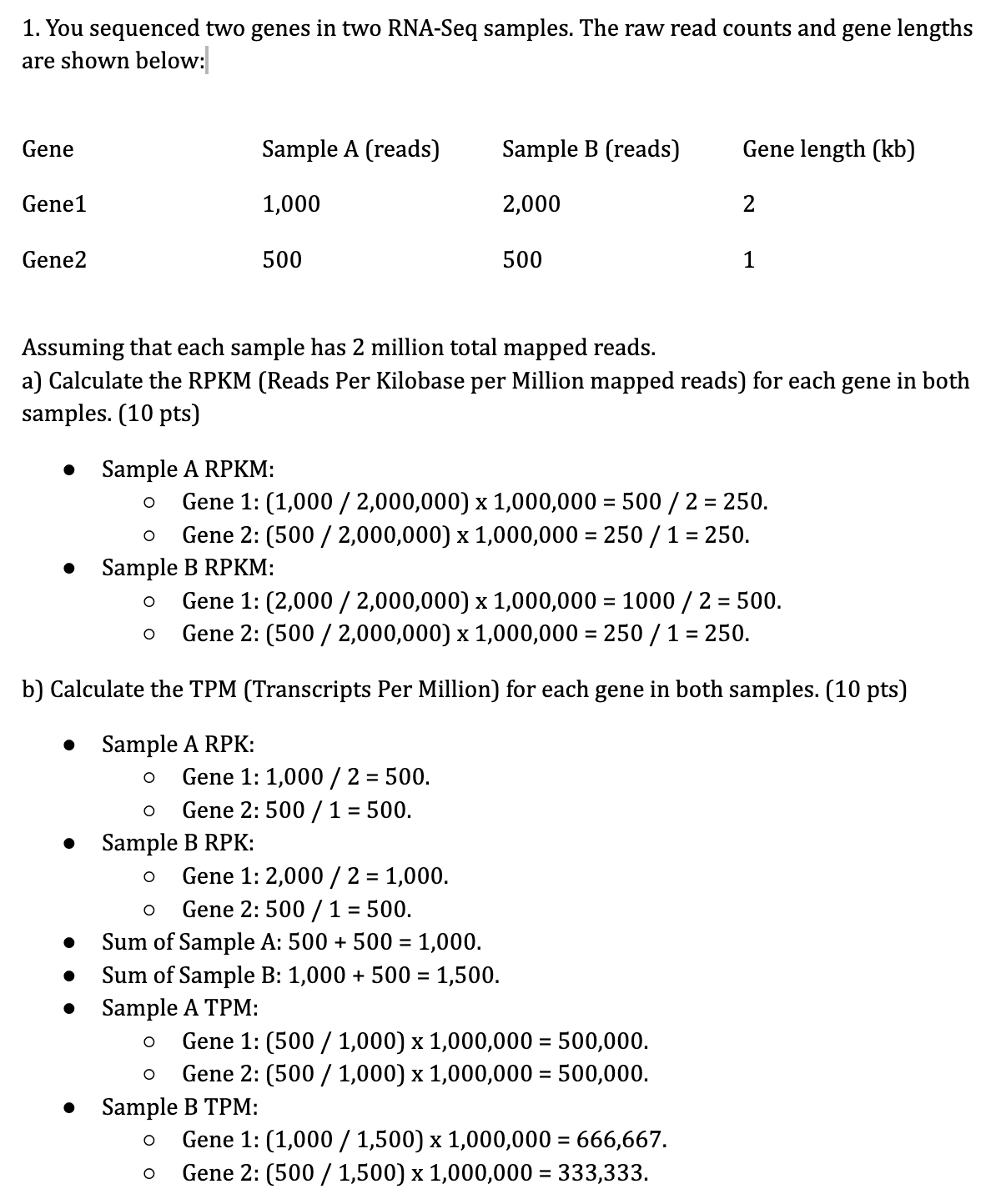

RPKM summary

Step 1 = normalize for sequencing depth: RMP = (raw counts for gene / (total mapped reads / 10)) x 1,000,000.

Divide the total mapped reads by 10 to simplify the number.

Step 2 = normalize for gene length: RPKM = RPM / gene length in kilobases.

Example:

Gene length = 2 kb.

Gene raw counts = 10.

Total mapped reads = 35.

Step 1: (10 / (35/10)) x 1,000,000 = 2.86.

Step 2: 2.86 / 2 = 1.43.

TPM vs. RPKM

RPKM:

Reads mapped / (gene length * total mapped reads in millions).

Normalizes for depth first, then length.

The total RPKM/FPKM of all genes in a sample does NOT sum to the same value across different samples.

Only for comparing the expression between different genes within a single sample.

TPM:

((Reads mapped / gene length in kb) / (sum of all genes) (reads mapped / gene length in kb)) * 106.

Normalizes for length first, then scales the length-normalized values (the RPK) by the total sum of all RPKs in the sample.

The sum of all TPM values in a sample is always 106 (one million), making samples directly comparable.

Recommended for comparing the expression of a single gene across different samples (replicates).

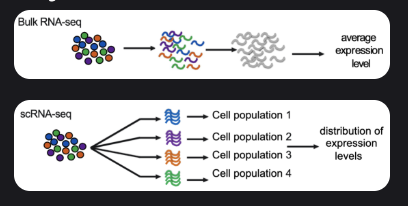

Evolution of gene expression measurements

Bulk RNA-seq: Measures average gene expression across many cells.

Cost-effective and straightforward, but masks cell-to-cell differences.

Single-cell RNA-seq: Profiles individual cells to reveal cellular heterogeneity, rare cell types, and dynamic states.

Spatial RNA-seq: Captures where genes are expressed within tissue, preserving spatial context and cell-cell interactions.

Why study single cells?

When compared to bulk RNA-seq, single-cell studies:

Reveals cell-to-cell differences and provides an unbiased view of cellular complexity within a tissue.

Allows for the discovery and precise identification of rare cell types and dynamic cellular states (e.g., transitional stages).

Provides the highest resolution view of the intermediate step between genotype and phenotype (where cells are the functional constituents).

Bulk vs. scRNA-seq

Bulk RNA-seq:

Quantifying expression signatures from ensembles.

Insufficient for studying a heterogeneous system.

scRNA-seq:

Inference of gene regulatory networks across the cells.

Heterogeneity of cell responses.

Cell type identification.

scRNA-seq analysis cell- and gene-level analysis

Cell-level:

Marker gene identification.

Cluster analysis.

Trajectory analysis.

Gene-level analysis:

Single-cell differential expression analysis.

Gene set analysis.

Gene regulatory networks.

scRNA-seq process

Sample preparation.

Single-cell RNA sequencing.

Data processing.

Data analysis.

scRNA-seq sample preparation

Cells are physically separated into a single-cell solution from which specific cell types can be enriched or excluded.

Each cell is captured by one droplet.

Each droplet contains a unique barcode and the necessary reagents for reverse transcription.

Each individual RNA molecule captured within that droplet is tagged with its own unique molecular identifier (UMI).

The UMI distinguishes unique RNA molecules from duplicates that arise during PCR amplification.

scRNA-seq single-cell RNA sequencing

Extremely small amount of RNAs within a cell → hard to detect.

PCR amplification → start sequencing.

scRNA-seq data processing

UMI.

Gene counts.

Drop-outs in single cell.

Imputation method: MAGIC.

Unique molecular identified (UMI)

UMIs are short (4-10 bp) random barcodes added to transcripts during reverse-transcription.

UMIs enable sequencing reads to be assigned to individual transcript molecules and thus the removal of amplification noise and biases from scRNA-Seq data.

They reduce the amplification noise by allowing (almost) complete duplication of fragments.

Counting the number of distinct UMI sequences is easier.

This information does not get lost during the amplification process.

Gene counts

In each gene, within each cell, the total number of unique UMI is counted and reported as the number of transcripts of that gene for a given cell.

Drop-outs in single cell

A gene can be observed at a moderate or high expression level in one cell but not detected in another.

Why do dropouts occur in a single cell:

Technical artifacts.

Cell type differences.

Statistical sampling.

Biological factors.

Zero inflation: unusually high number of zeros (undetected gene expression values).

What should we do about dropouts?

Ignore zero inflation:

Let downstream statistical methods do the heavy lifting.

Aggregate information across similar cells.

Clustering or pseudobulk approaches.

Smooth out noise and highlight consistent expression patterns.

Impute scRNA-seq gene count matrix before analysis.

Estimate missing gene expression values and reduce sparsity caused by dropouts.

Why do we need imputation methods?

Downstream analyses rely on the accuracy of gene expression measurements.

Imputation methods:

MAGIC.

Droplet.

DrImpute.

scDoc.

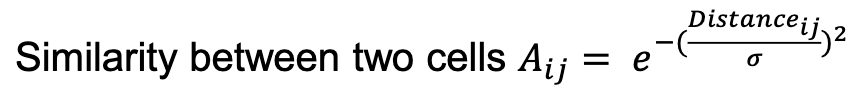

MAGIC (Markov affinity-based graph imputation of cells)

Denoise high-dimensional scRNA-seq data.

Impute missing expression values by sharing information across similar cells.

Transform the similary of matrix A into Markov transition matrix M.

Raise the Markov matrix to the power of t: Mt, which determines the weight of cells.

scRNA-seq data analysis

Dimensionality reduction.

Clustering and marker identification.

Trajectory analysis.

Gene expression analysis: clustering

Organize objects into groups based on similarity.

A cluster is a collection of objects which are similar to objects in the same cluster, but are dissimilar to objects in other clusters.

Hierarchial clustering

Divisive:

Starts with all data points in one cluster.

Choose split so that data points in the two clusters are most similar (maximize “distance” between clusters).

Continue until all data points are in single gene clusters.

Agglomerative: union between the two nearest clusters.

Start with each data point in its own cluster.

Joins the two most similar clusters.

Continues until all data points are in one cluster.

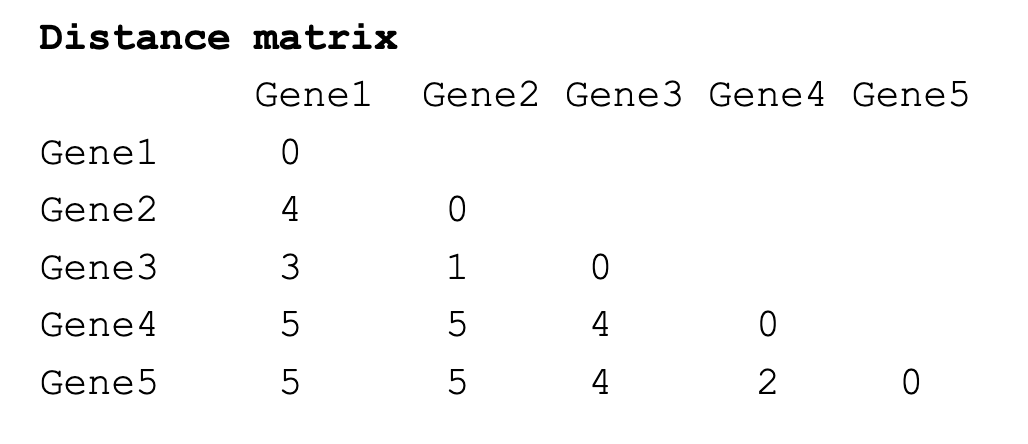

How to find the two most similar clusters

Single linkage: shortest distance.

Complete linkage: longest distance.

Average linkage: average distance.

!! Single-linkage example

ask gemini

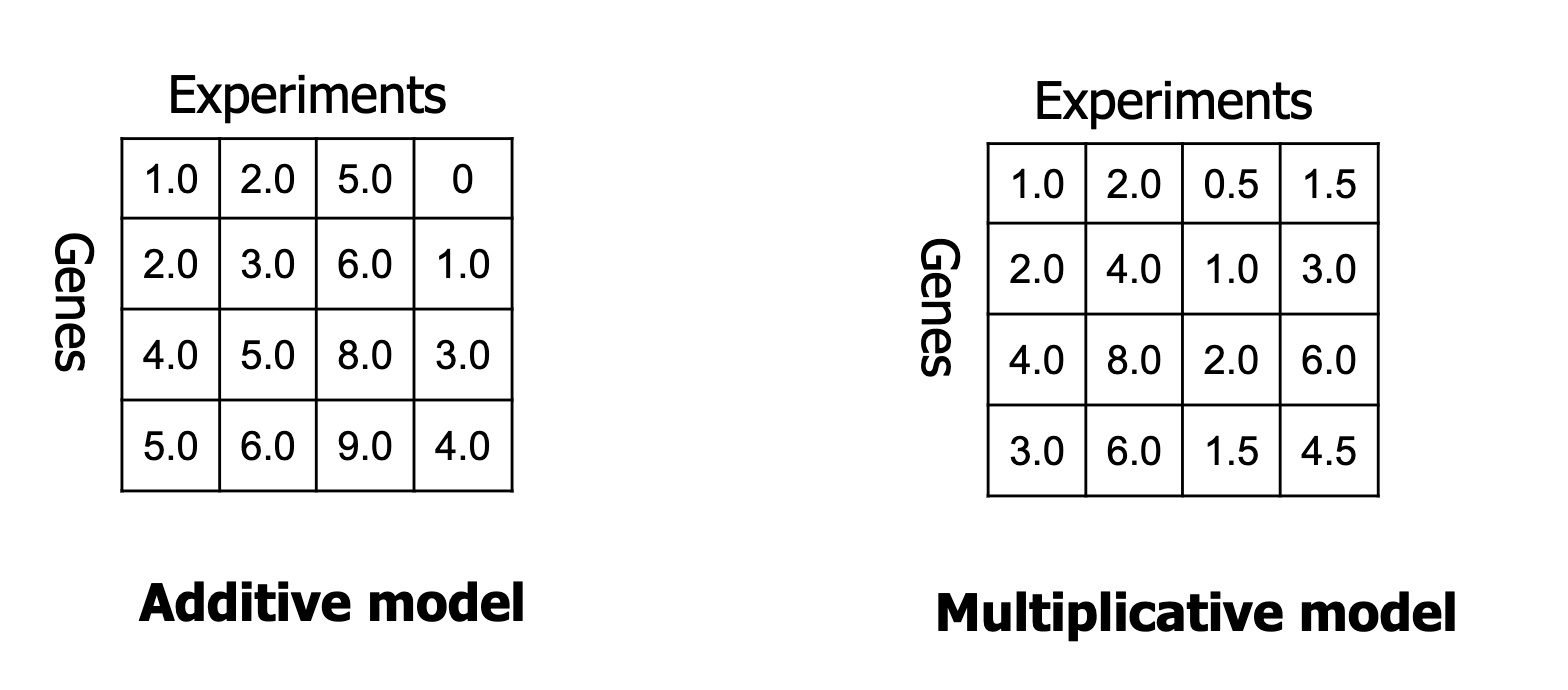

!! Biclustering

Clustering becomes too restrictive on large datasets:

Seeks a global partition of genes based on their expression similarity across ALL conditions.

Relevant knowledge can be revealed by identifying genes with a typical pattern across a subset of the conditions: e.g., genes co-expressed under some conditions.

Bi-clustering patterns

Constant values: might be an over/under-expression of a group of genes in a subset of experiments.

Constant rows: a gene signature of a subset of experiments.

Constant columns: a set of co-expressed genes in a subset of experiments.

Coherent values: a common trend in a group of genes in a subset of experiments.

The picture holds examples.

!! A good bi-cluster

!! δ (Delta) bi-cluster

Find bi-clusters with mean squared residue < δ.

Repetitive procedure:

Remove the row/col that reduces H the most.

Add rows/cols that do not increase H.

Stop when H < δ.

Mask bi-cluster with random values.

Repeat to find more bi-clusters.

WHAT IS δ AND WHAT IS H????

!! Differential gene expression

What to compare - differential gene expression

TPM: correct for sequencing depth and gene length.

Tool: edge, suitable for small sample sizes.

TMM: correct for differences in transcript pool composition; extreme outliers.

logCPM: stabilize variance; remove dependence of variance on the mean.

Tool: Limma, suitable for moderate to large sample sizes.

All aim to provide better comparison across samples.

Other tool: DESeq2.

Negative binomial model with geometric size-factor normalization; shrinkage of dispersion & fold-change.

Broadly used.

Normalization in differential gene expression analysis

EdgeR, DESeq2, and some others want to keep the integer read counts in the differential gene expression testing because they:

Use a discrete statistical power.

Want to retain statistical power.

But they are simplified as part of the differential gene expression analysis.

Limma is fine with continuous values like FPKM.

!! Parametric vs. non-parametric

Parametric methods often work better.

For experiments with fewer than 12 samples per group: use edgeR.

UseDESeq2 otherwise.

WHAT IS PARAMETRIC VS. NON-PARAMETRIC???

!! Be careful with DE analysis

Too many false positives.

Take-away message:

Wilcoxon rank-sum test is recommended.

what the hell is this