Chapter 12 - Cognitive Control(Decision-Making)

1/30

Earn XP

Description and Tags

all key experiments for cognitive neuroscience course at kaist bcs221

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

31 Terms

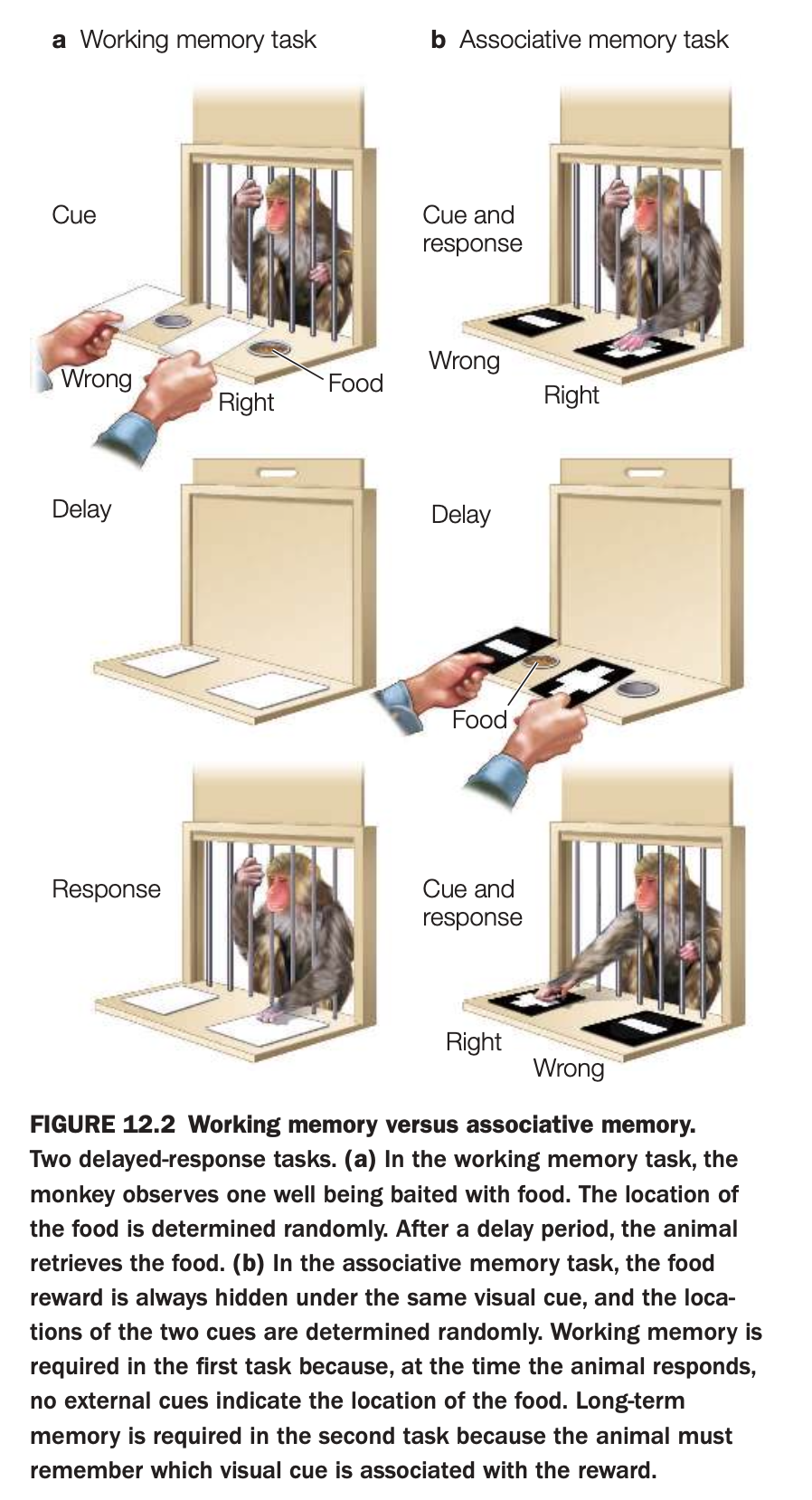

1. Purpose of the study

The goal is to show that short‑term maintenance of a specific location (working memory) can be behaviorally separated from learning a stable cue–reward association (associative or long‑term memory).

These tasks are then used to link different prefrontal and medial temporal regions to distinct memory processes.

2. Methods and procedures

In the working‑memory task (panel a), the experimenter baits one of two wells with food while the monkey watches; well identity is random each trial.

After a delay with the wells covered, the monkey must remember the most recently baited location to obtain the reward, with no external cue indicating the correct side.

In the associative‑memory task (panel b), the food is always hidden under the same visual cue (e.g., a particular pattern), while cue locations are randomized.

Following a delay, the monkey must choose the well covered by the rewarded cue, relying on a learned, long‑term association between that visual pattern and food.

3. Main findings illustrated

Success in the working‑memory task depends on retaining a trial‑specific spatial representation across a short delay, whereas success in the associative task depends on stable long‑term knowledge of which cue predicts reward.

Lesion and recording studies using these paradigms show that dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is critical for the spatial working‑memory task, while medial temporal and other associative regions support the visual cue–reward memory.

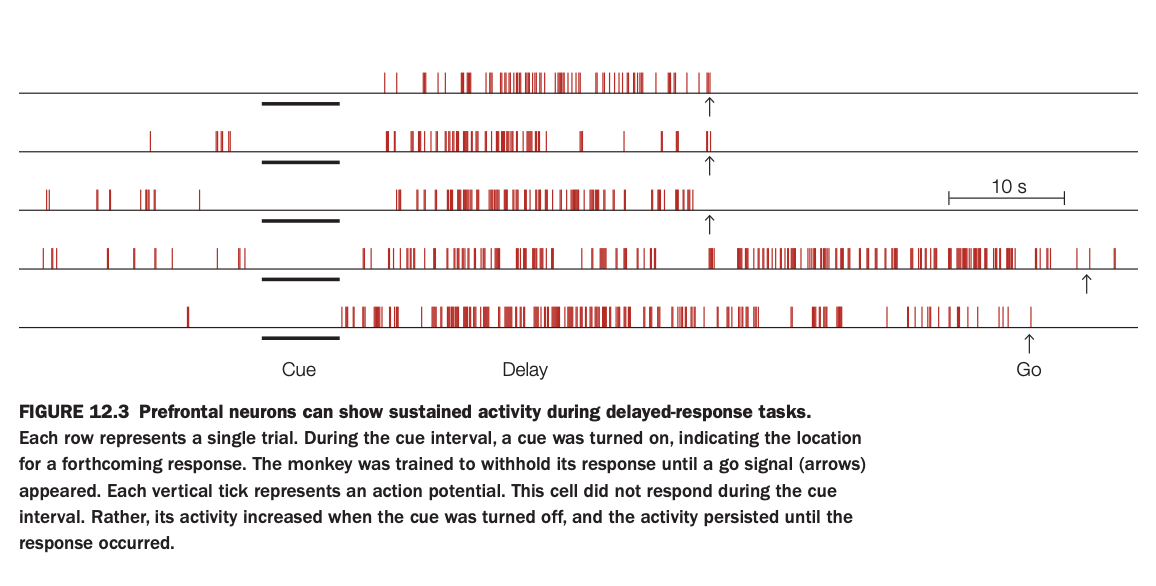

1. Purpose of the study

The aim was to record single‑unit activity in prefrontal cortex while monkeys performed a delayed‑response task to see how neurons encode information across the delay.

Researchers wanted to test the idea that sustained firing in prefrontal cells maintains task‑relevant information in working memory.

2. Methods and raster plot

Each row is one trial; vertical red ticks mark action potentials over time.

A cue indicating target location is presented (cue epoch, black bar), then removed during a delay, and finally a “go” signal (arrow) tells the monkey to respond.

3. Activity pattern illustrated

This particular neuron shows little or no response during the cue itself but begins firing strongly once the cue is turned off and continues throughout the delay until the response.

The persistent delay activity is reliable across trials, only dropping after the go cue when the behavior is executed.

4. Main findings

Such delay‑period neurons are common in prefrontal cortex and are tuned to specific cue locations or rules, suggesting they hold the content of working memory.

Their activity bridges the temporal gap between stimulus and response, providing a neural substrate for short‑term maintenance without external input.

5. Neuroscientific implications

These results support models in which recurrent prefrontal networks keep information “online” via sustained firing, rather than relying solely on transient synaptic traces.

They also explain why prefrontal lesions selectively impair delayed‑response tasks that require remembering a location or rule over a brief interval.

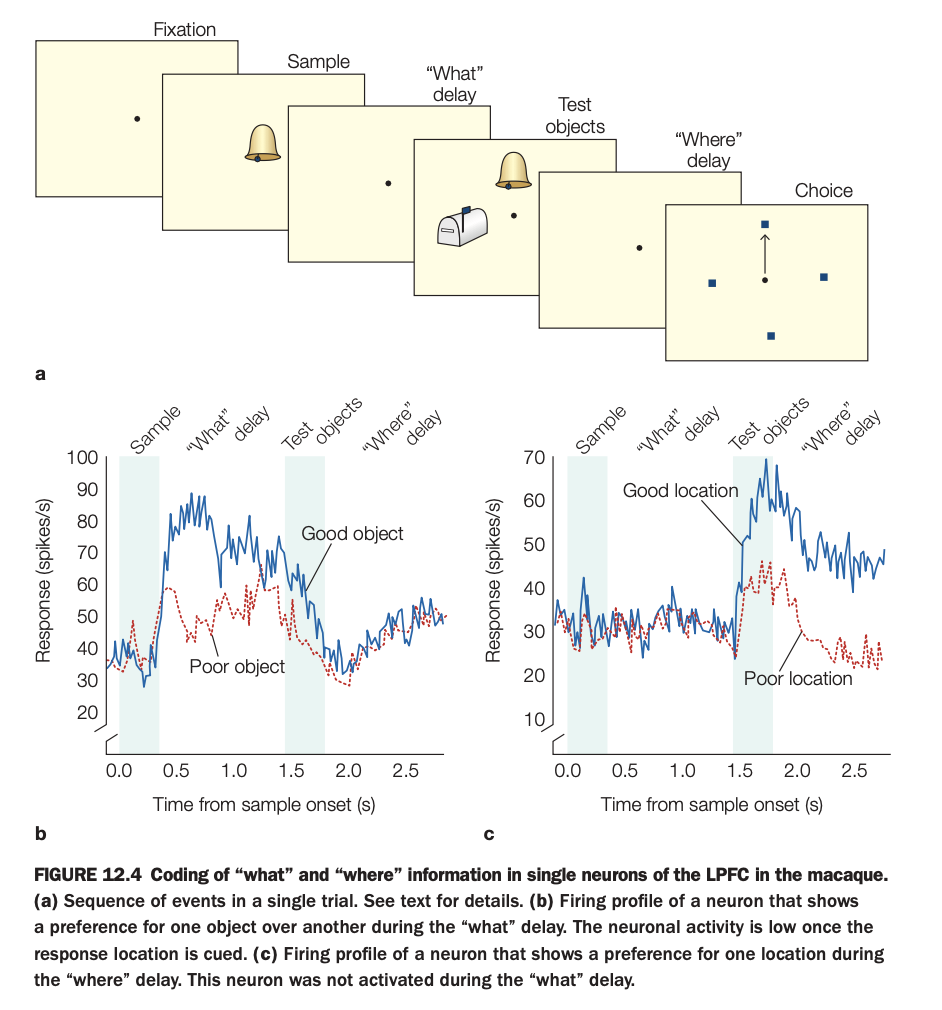

1. Purpose of the study

The goal was to determine whether individual LPFC neurons carry content‑specific working‑memory signals for objects versus spatial locations during a task that temporally separates these demands.

This helps clarify how prefrontal cortex supports multiple components of working memory within a single circuit.

2. Methods and trial sequence

Monkeys first fixate, then see a sample object, followed by a “what” delay where they must remember which object was shown.

Next, test objects appear, then a “where” delay where the animal must remember the correct spatial location before making a choice among several locations.

3. Panels and activity profiles

Panel b plots firing of a “what”‑selective neuron: during the “what” delay, it fires more for the preferred (“good”) object than for the nonpreferred (“poor”) object, but activity drops once the response location is later cued.

Panel c shows a “where”‑selective neuron: it fires similarly across objects but during the “where” delay shows higher activity for the preferred (“good”) location than for the poor location; it was not strongly active during the prior “what” delay.

4. Main findings

Some LPFC neurons maintain object‑specific information across the object delay, while others maintain location‑specific information across the spatial delay, with tuning that persists over seconds.

The selectivity switches in time with task demands: object cells quiet down when location becomes relevant, and vice versa.

5. Neuroscientific implications

These results support the view that prefrontal cortex contains mixed but functionally specialized populations that maintain different kinds of task‑relevant information in working memory.

They also show that “what” and “where” information can be dynamically routed and sustained within LPFC, enabling flexible cognitive control over objects and locations in complex behaviors.

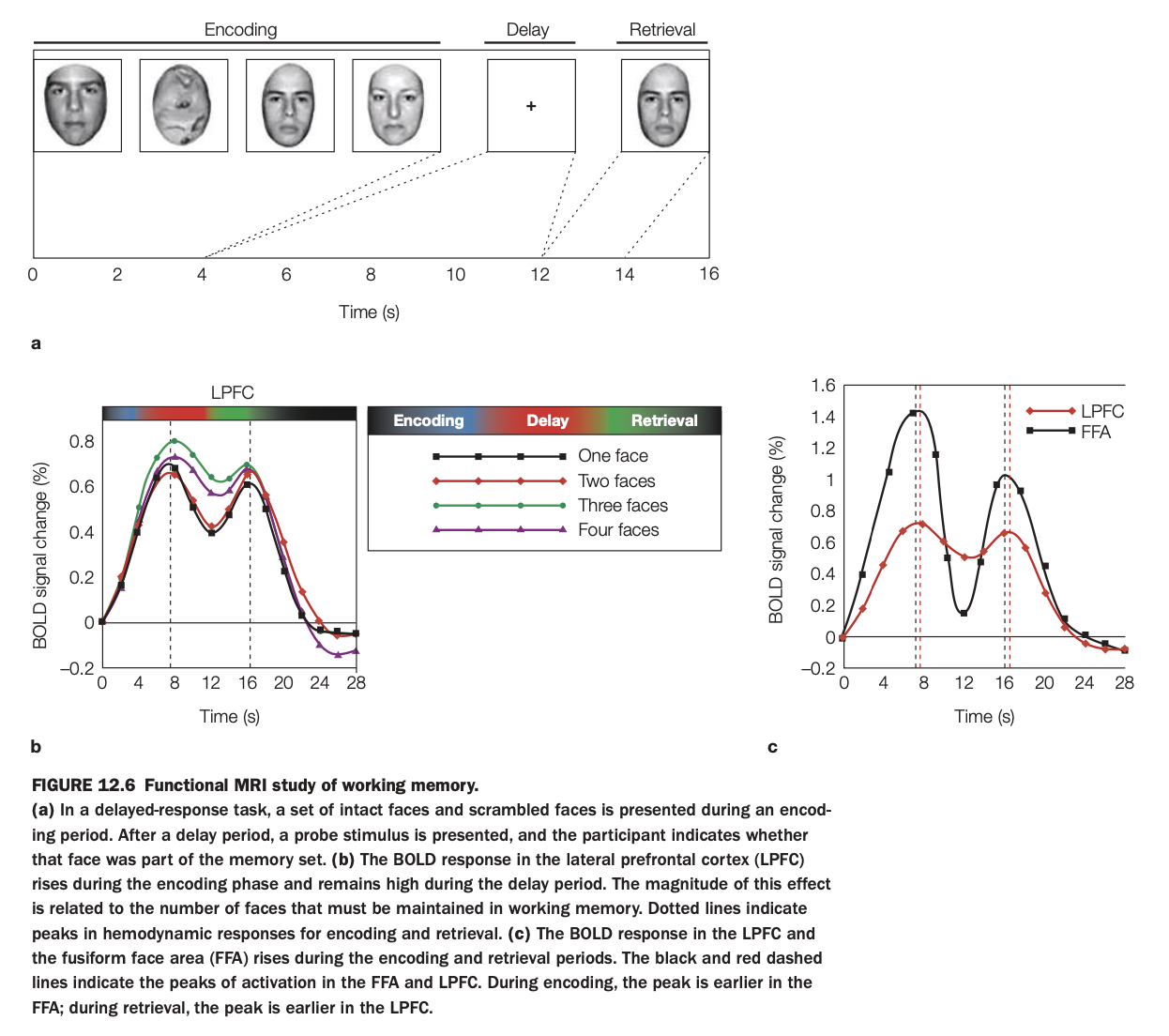

1. Purpose of the study

The aim was to use fMRI to examine how LPFC and FFA contribute differently to encoding, maintenance, and retrieval of face information in a delayed‑recognition task.

By varying the number of faces to remember, the study also tested whether LPFC activity scales with working‑memory load.

2. Methods and trial structure

Participants saw sets of intact and scrambled faces during an encoding phase, held them in mind across a delay with only a fixation cross, and then judged whether a probe face had been in the memory set.

BOLD responses were measured in LPFC and FFA as a function of time and memory load (one to four faces).

3. LPFC time course and load effect

Panel a (left graph) shows that LPFC activity rises during encoding and stays elevated through the delay; the amplitude increases systematically with more faces to maintain.

This load‑sensitive, sustained activation is characteristic of a working‑memory maintenance region rather than a purely perceptual area.

4. LPFC vs FFA dynamics

Panel c (right graph) compares LPFC and FFA: FFA peaks early during encoding and again at retrieval, consistent with face perception and re‑perception of the probe, but shows little sustained delay activity.

LPFC peaks later during encoding and remains more active during the delay, with a smaller retrieval peak; the vertical dashed lines mark these timing differences.

5. Neuroscientific implications

The results support a division of labor in which FFA represents face content during sensory input and output, while LPFC maintains an abstract, load‑dependent working‑memory representation across delays.

They align with models where prefrontal regions provide domain‑general control and maintenance signals that operate over modality‑specific posterior areas storing detailed stimulus features.

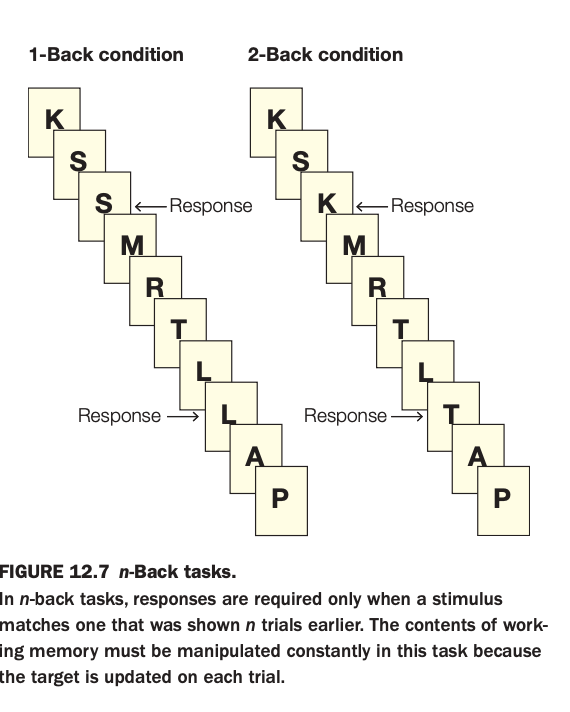

1. Purpose of the task

The goal is to tax online maintenance and manipulation in working memory by asking participants to detect when the current stimulus matches one shown n trials earlier.

By varying n (e.g., 1‑back vs. 2‑back), researchers can parametrically increase working‑memory load and examine associated behavioral and neural changes.

2. Methods and conditions

Stimuli (here, letters) are presented one at a time in a continuous stream.

In the 1‑back condition, participants respond when the current letter is identical to the immediately preceding one; in the 2‑back condition, they respond when the current letter matches the one two positions back in the sequence.

3. Panels and responses

The left sequence shows a 1‑back run where an S following S and an L following L require responses.

The right sequence shows a 2‑back run where a K that matches the letter two steps earlier and an L that matches the letter two steps earlier trigger responses.

4. Main cognitive demands

Performance requires continuously updating the contents of working memory, discarding old items and re‑coding new ones on every trial.

As n increases, the task becomes more difficult, engaging lateral prefrontal and parietal regions associated with executive control and maintenance of multiple items.

5. Neuroscientific implications

The n‑back paradigm is widely used in neuroimaging to index working‑memory capacity and frontal‑parietal network function in both healthy individuals and clinical populations.

It helps dissociate short‑term storage demands from simple perceptual or motor processes, making it a core tool for studying executive aspects of working memory.

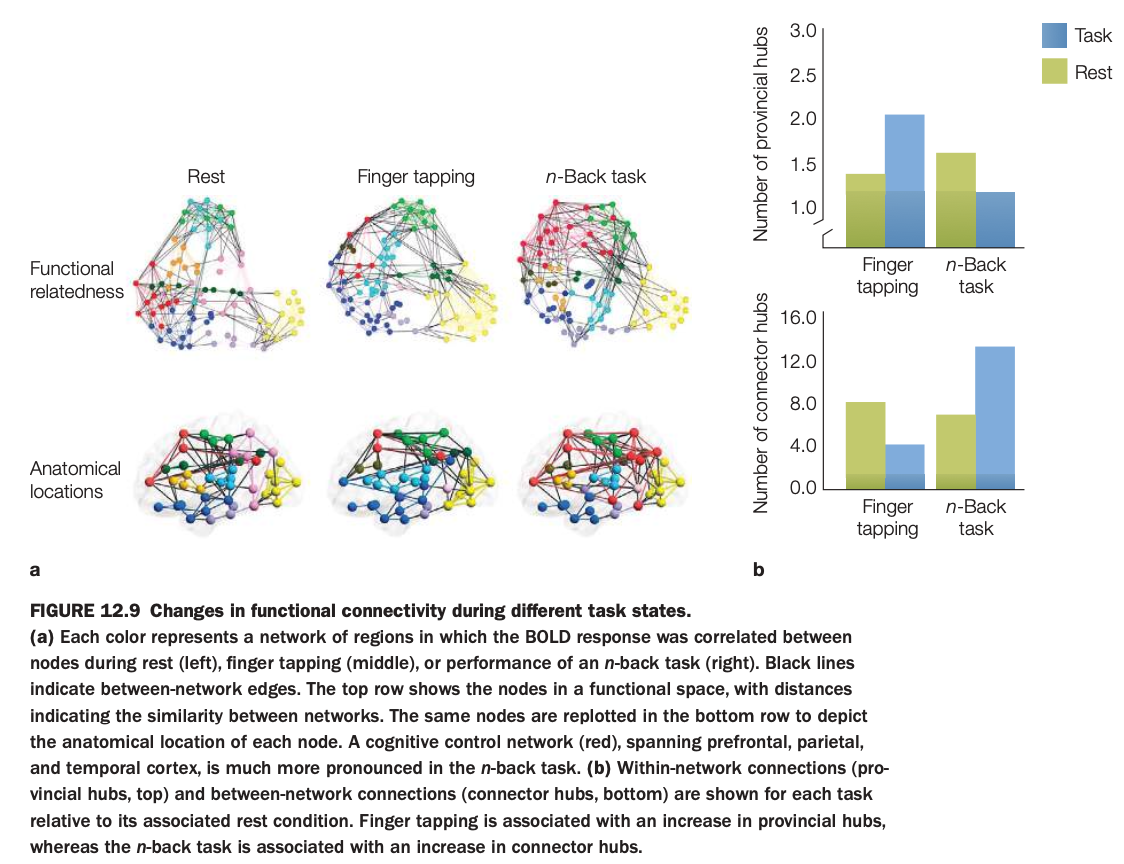

1. Purpose of the study

The aim was to examine how functional connectivity patterns and network hubs differ across cognitive states (rest, simple motor task, demanding working‑memory task).

It tests whether task demands selectively engage control networks and alter between‑network communication.

2. Methods and network maps

Functional MRI data were parcellated into nodes, and correlations between BOLD time series defined edges, yielding graphs for rest, finger tapping, and n‑back performance.

Top row in panel a plots networks in a “functional space” where distance reflects similarity; bottom row re‑plots the same nodes on the cortical surface according to anatomical location.

3. Connectivity patterns

At rest, multiple networks (different colors) are present with moderate interconnections.

During finger tapping, motor‑related networks strengthen; during the n‑back task, a frontoparietal cognitive control network (red) spanning prefrontal, parietal, and temporal cortex becomes especially prominent.

4. Hub changes (panel b)

Provincial hubs (highly connected within one network) increase slightly during finger tapping relative to rest, reflecting more within‑motor‑network cohesion.

Connector hubs (nodes linking different networks) show a marked increase during the n‑back task compared with rest and finger tapping, indicating greater cross‑network integration for demanding working‑memory processing.

5. Neuroscientific implications

The results support the idea that the brain flexibly reconfigures its functional architecture depending on task demands, with control‑heavy tasks recruiting more connector hubs to coordinate distributed systems.

Simple sensorimotor tasks mainly strengthen local, within‑network connectivity, while complex cognition relies on integrative hub nodes that bridge multiple networks.

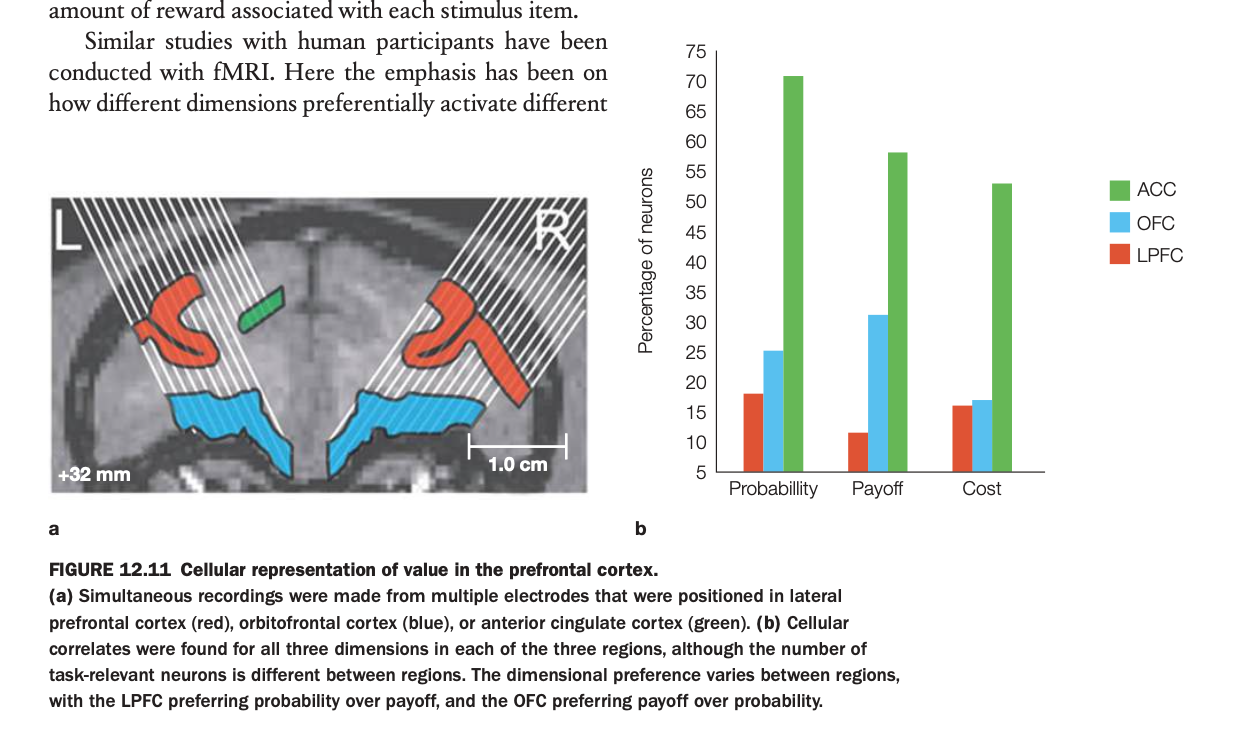

1. Purpose of the study

The aim was to compare how lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) represent various components of expected value.

By recording simultaneously from these areas, researchers could see which regions preferentially encode probability of reward, magnitude of payoff, or associated costs.

2. Methods and recordings

Multielectrode arrays were implanted in LPFC (red), OFC (blue), and ACC (green) in monkeys performing a task where options varied independently in reward probability, payoff size, and cost.

Neurons were classified according to which dimension their firing correlated with most strongly, yielding the percentage of cells tuned to each factor in each region.

3. Bar graph patterns

In ACC, the majority of task‑related neurons encode probability and cost, with especially high percentages for probability and substantial representation of cost.

OFC shows more neurons preferring payoff than probability, consistent with its role in coding reward magnitude and subjective value, while LPFC shows more tuning to probability than payoff and some sensitivity to cost.

4. Main findings

All three regions contain neurons responsive to each dimension, but the distribution differs systematically, indicating regional specializations within a distributed value network.

LPFC is relatively probability‑focused, OFC is payoff‑focused, and ACC prominently represents probability and cost, consistent with its role in monitoring action outcomes and effort.

5. Neuroscientific implications

These results support models in which economic decision making relies on partially specialized prefrontal subcircuits that encode complementary aspects of value.

Integration of these signals across LPFC, OFC, and ACC likely underpins flexible choices that weigh likelihood, benefit, and cost of potential actions.

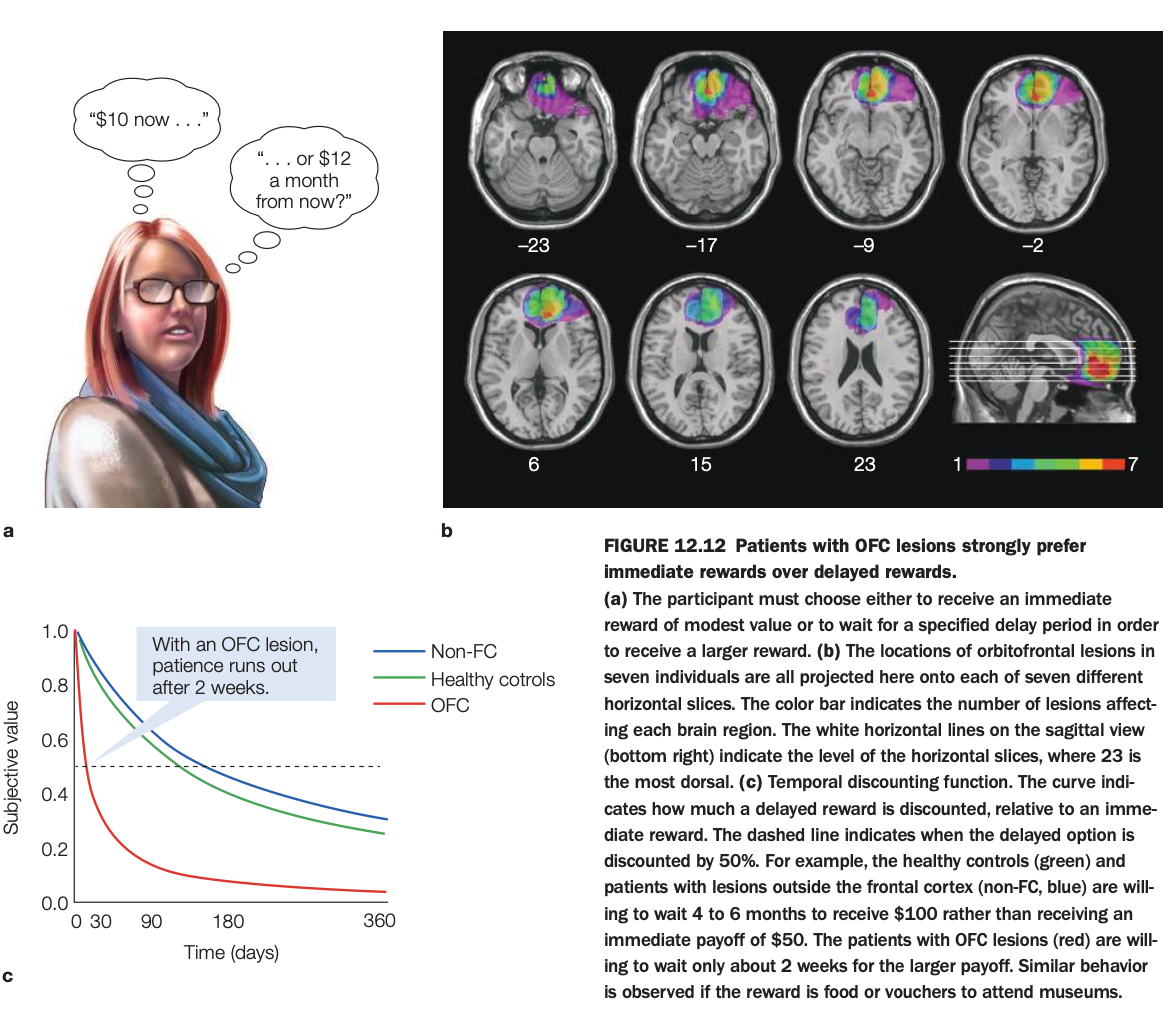

1. Purpose of the study

The aim was to test how damage to OFC affects intertemporal choice—decisions between smaller‑sooner versus larger‑later rewards.

By comparing these patients to healthy controls and non‑frontal lesion patients, researchers assessed OFC’s role in patience and value integration over time.

2. Methods and task

Participants repeatedly chose between options like “$10 now” versus “$12 in a month,” with varying delays up to many months.

Choices were used to estimate each person’s temporal discounting curve, expressing the subjective value of a delayed reward relative to an immediate one.

3. Lesion locations (panel b)

Overlapping lesion maps in seven individuals show damage concentrated in ventromedial/orbitofrontal regions of frontal cortex.

Color coding reflects how many patients had lesions in each voxel, confirming consistent OFC involvement across the sample.

4. Discounting curves (panel c)

Healthy controls and non‑frontal lesion patients discount delayed rewards moderately and are willing to wait 4–6 months to receive $100 instead of $50 now (subjective value remains above 0.5 for long delays).

OFC patients’ curves drop steeply, with delayed rewards losing value rapidly; they are willing to wait only about two weeks for the larger payoff before preferring the smaller immediate reward.

5. Neuroscientific implications

The results indicate that OFC is critical for representing the future value of delayed outcomes and for exercising patience in economic decisions.

When OFC is damaged, people become myopic decision makers, over‑weighting immediate gratification relative to longer‑term benefits, a pattern also relevant to addiction and impulse‑control disorders.

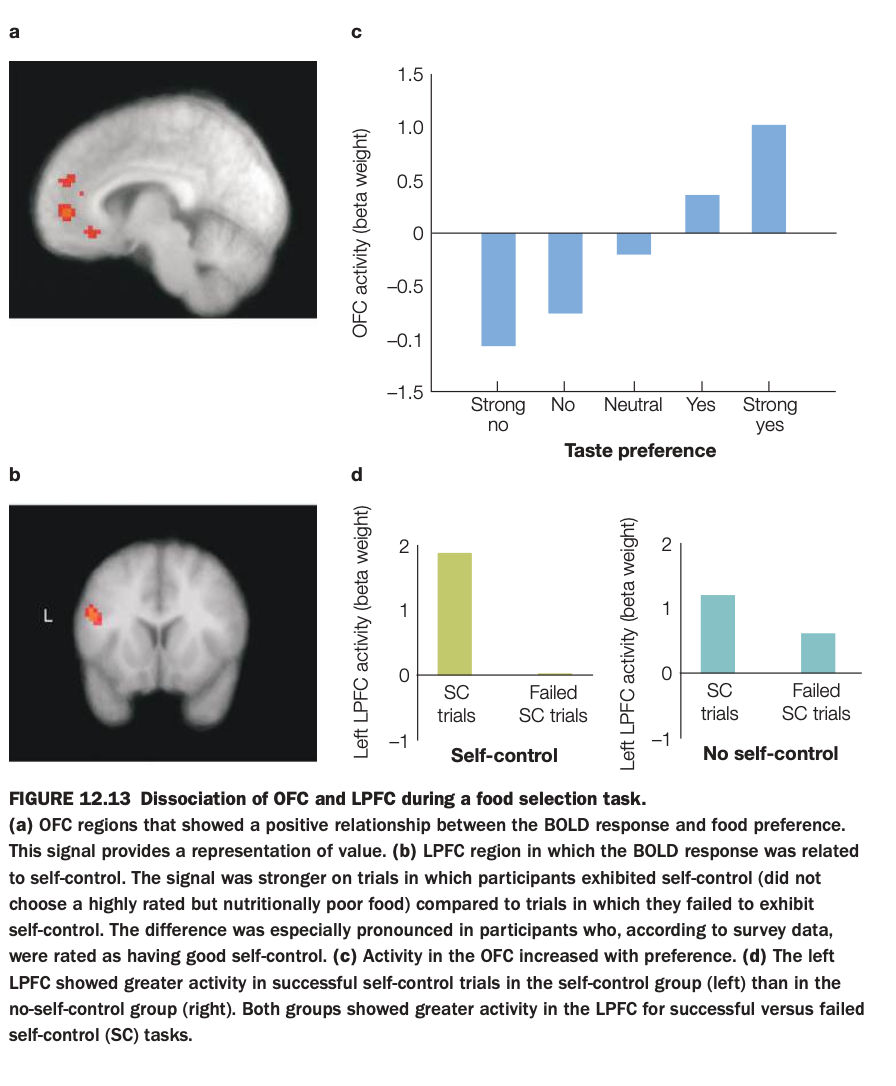

1. What is the purpose of the study/figure?

To show how orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) represents the subjective value of foods, and how lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) supports self‑control when choosing between tasty but unhealthy and healthier options.

2. What methods/tasks were used?

Participants in an fMRI scanner rated how much they liked various foods and then made choices about whether to eat them, sometimes needing to resist highly liked but unhealthy items.

BOLD activity was measured in OFC (value‑related region) and left LPFC (control‑related region), and trials were categorized by taste preference and by whether participants succeeded or failed at self‑control.

3. What do the panels show and how are they related?

Panel a shows OFC voxels where activity increases with food preference; panel c plots this quantitatively, with OFC activity going from negative for “strong no” foods to strongly positive for “strong yes” foods.

Panel b shows a left LPFC region linked to self‑control; panel d compares LPFC activity on successful versus failed self‑control (SC) trials, separately for people with good self‑control and those with poor self‑control.

4. What are the main findings?

OFC activity scales monotonically with how much participants like a food, indicating a neural value signal that is higher for more preferred items.

LPFC activity is greater on trials where people successfully override temptation than when they give in, and this effect is especially strong in individuals rated as having good self‑control.

5. What are the neuroscientific/psychological implications?

OFC primarily encodes the subjective value of options, while LPFC implements top‑down control that can veto high‑value but unhealthy choices when self‑control is exercised.

This dissociation supports models in which valuation and control are implemented in partially distinct prefrontal systems that interact during real‑world decision making about temptations like food.

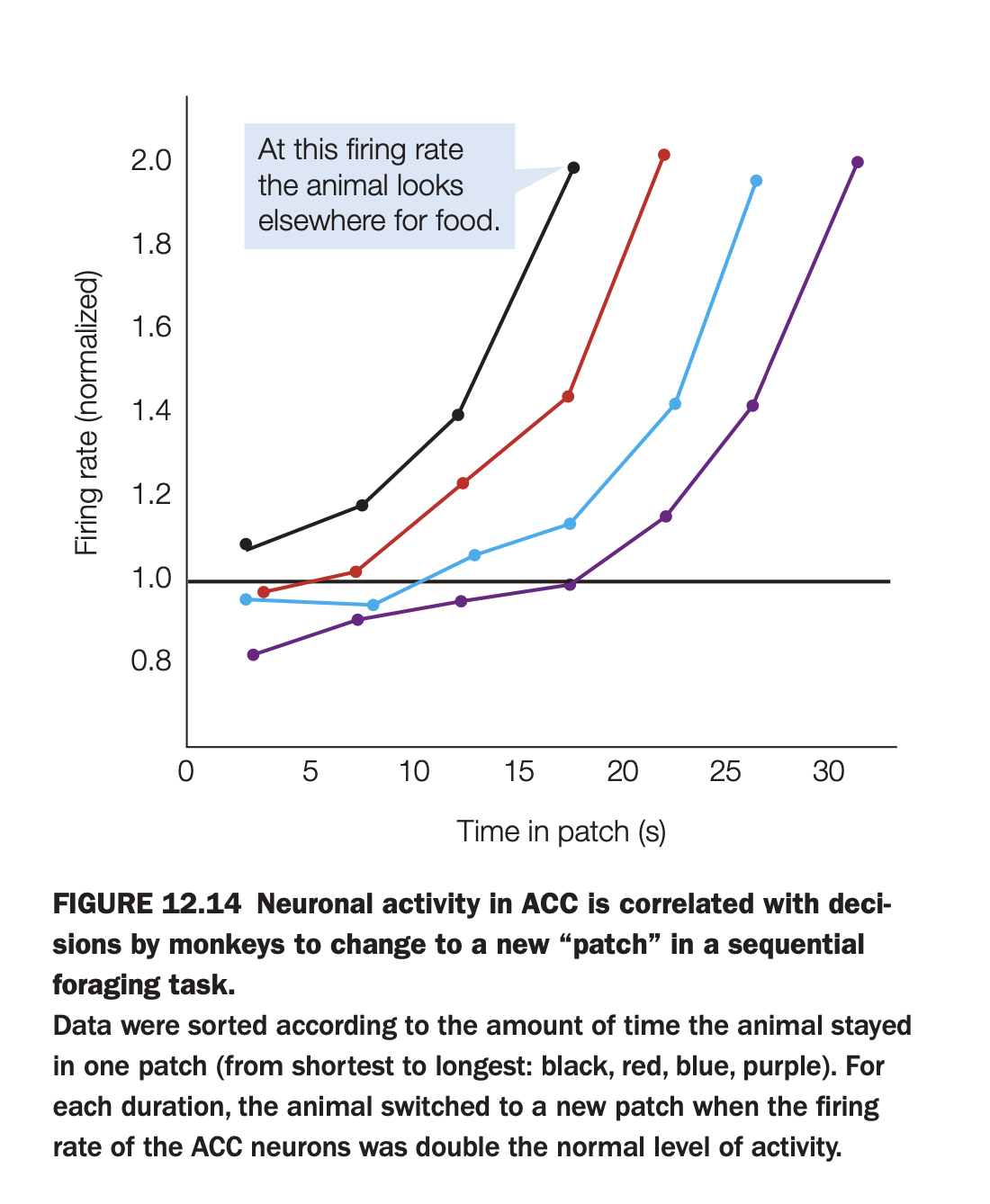

1. What is the purpose of the study/figure?

To show that activity in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) ramps up while a monkey exploits a food “patch” and reaches a stereotyped level right when the animal decides to leave that patch and search elsewhere.

2. What methods/tasks were used?

Monkeys performed a sequential foraging task where they collected rewards from one patch for some time and then chose when to move to a new patch.

Single‑unit activity was recorded in ACC, and trials were grouped by how long the monkey stayed in the patch (shortest to longest: black, red, blue, purple curves).

3. What do the axes and curves show?

The x‑axis is time spent in the current patch (seconds), and the y‑axis is normalized ACC firing rate.

Each colored line shows how firing rate increases over time for trials with a particular total patch duration; the callout marks a firing level at which the monkey typically switches patches.

4. What are the main findings?

Across all durations, ACC firing ramps upward while the monkey remains in the patch and reaches roughly twice the baseline level at the moment the animal decides to leave.

Although the ramp is steeper for shorter stays and shallower for longer ones, the “threshold” firing rate at the decision to leave is similar across conditions.

5. What are the neuroscientific/psychological implications?

ACC appears to encode an accumulating decision variable about whether to stay or switch, with a threshold mechanism triggering the move to a new foraging patch once cost–benefit evidence crosses a critical level.

This supports models in which ACC tracks opportunity costs and guides adaptive changes of strategy when continuing the current behavior becomes less advantageous.

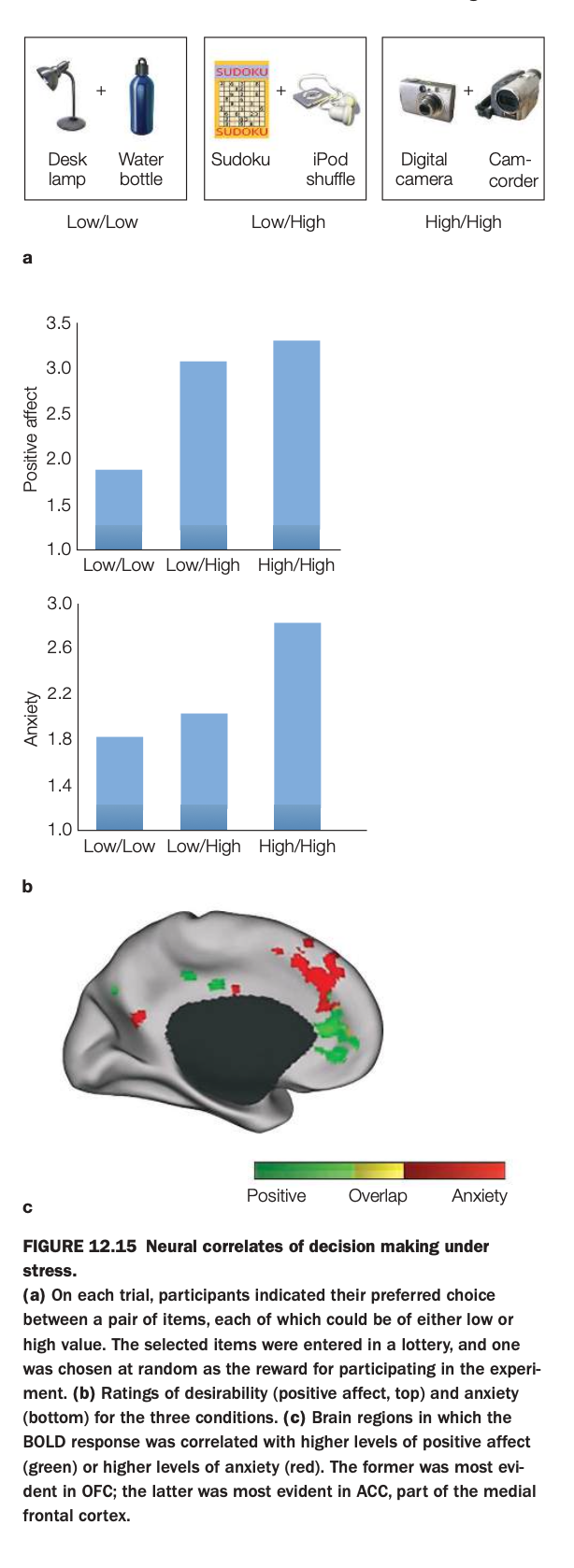

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how making choices between low‑ and high‑value options elicits both positive affect and anxiety, and how these emotional components map onto different regions of medial frontal cortex under decision stress.

2. Methods / task used

On each trial, participants chose their preferred item from a pair of consumer goods; each item in a pair could be low or high in subjective value, producing Low/Low, Low/High, or High/High choice sets.

Choices entered a lottery so that one selected item would actually be received, increasing the stakes; participants then rated positive affect and anxiety, while fMRI measured BOLD responses.

3. Panels and relationships

At the top are example pairs for the three conditions (Low/Low, Low/High, High/High).

Panel a shows bar graphs: positive affect (top) is higher for Low/High and High/High than for Low/Low, while anxiety (bottom) is highest for High/High choices, where both options are attractive.

Panel b/c display medial frontal cortex, with green voxels where activity correlates with positive affect, red voxels where activity correlates with anxiety, and yellow where the two overlap.

4. Main findings

Mixed high‑value choices (especially High/High) produce both strong positive affect and elevated anxiety, reflecting the “stress” of choosing between two good options.

Positive affect–related activity is prominent in OFC regions, whereas anxiety‑related activity is strongest in anterior cingulate/medial frontal areas, with some regions responding to both.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Decision making under high stakes engages partially distinct valuation (OFC) and conflict/anxiety (ACC) systems, explaining why choosing between desirable alternatives can feel both exciting and stressful.

These results support models in which medial prefrontal subregions track emotional components of choice, with ACC signaling conflict and potential loss while OFC tracks anticipated reward.

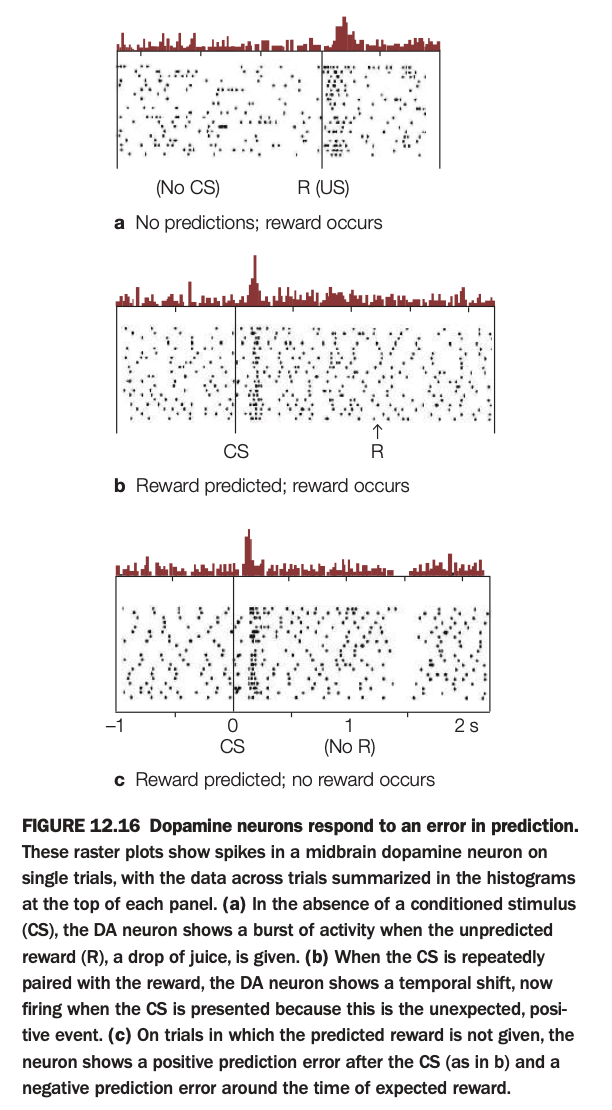

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how midbrain dopamine neurons encode reward prediction error: the difference between expected and received reward, rather than reward itself.

2. Methods / task used

Spikes from a single dopamine neuron were recorded across many trials while a monkey received drops of juice (reward, R), sometimes preceded by a conditioned stimulus (CS) that predicted the reward.

Raster plots show individual spikes on each trial; histograms above each raster summarize average firing over time.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a (no CS) shows trials where an unexpected reward is delivered: firing is low until juice arrives, then there is a burst at reward time.

Panel b (CS→R) shows that after learning, the burst shifts from reward delivery to CS onset, with little change at reward time because it is now predicted.

Panel c (CS but no R) shows a burst at CS onset followed by a dip below baseline around the time when reward was expected but omitted.

4. Main findings

Dopamine neurons fire strongly to unexpected rewards, transfer this response to predictive cues once learning occurs, and decrease firing when an expected reward fails to occur.

Thus, their activity reflects positive prediction error when outcomes are better than expected and negative prediction error when outcomes are worse.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

These firing patterns support reinforcement‑learning models where dopamine signals a teaching signal that updates value estimates in striatum and cortex.

Such prediction‑error coding explains how organisms learn which cues predict reward and underlies many theories of habit formation, addiction, and adaptive decision making.

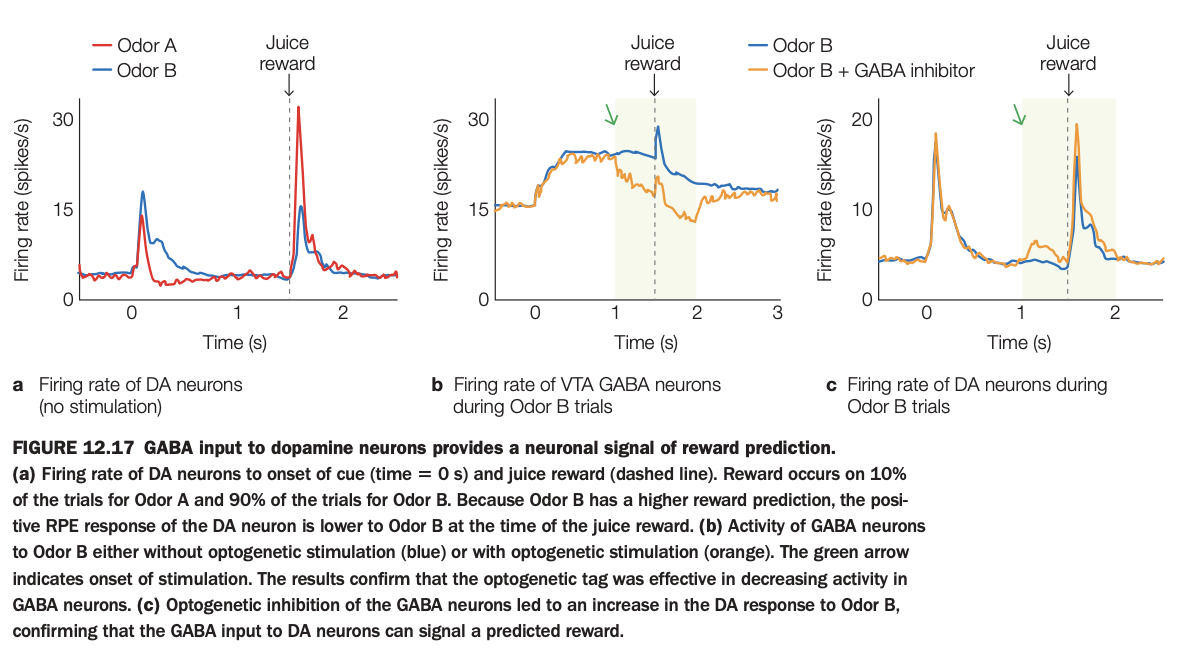

Using the 5‑question structure:

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show that inhibitory GABA input to dopamine (DA) neurons in ventral tegmental area (VTA) carries information about predicted reward and thus helps generate reward‑prediction error signals.

2. Methods / task used

Mice learned that two odors predicted juice reward with different probabilities (Odor A low, Odor B high).

Researchers recorded firing rates of DA neurons and nearby GABA neurons, and used optogenetic inhibition of GABA cells during Odor B trials to test causality.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a shows DA firing without stimulation: both odors evoke modest cue responses, but a big burst occurs at juice delivery, slightly smaller for highly predictive Odor B because reward is less surprising.

Panel b shows VTA GABA activity on Odor B trials, with and without optogenetic stimulation; optogenetic activation (orange) suppresses GABA firing during the shaded window after odor onset.

Panel c shows DA firing on Odor B trials with and without GABA inhibition; when GABA cells are inhibited (orange), DA response to expected reward is larger, as if the reward were more surprising.

4. Main findings

GABA neurons increase firing when a reward is predicted and their activity normally dampens DA responses to expected rewards, reducing positive prediction error.

Optogenetically inhibiting these GABA cells disinhibits DA neurons, boosting their firing to a predicted reward and demonstrating that GABA input can encode the prediction signal used to compute error.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

VTA DA prediction‑error signals are partly constructed by inhibitory GABA inputs that represent expected value, not solely by DA cell intrinsic properties.

This circuit mechanism explains how learning about reward probabilities can modulate DA bursts and thereby shape reinforcement learning and behavior.

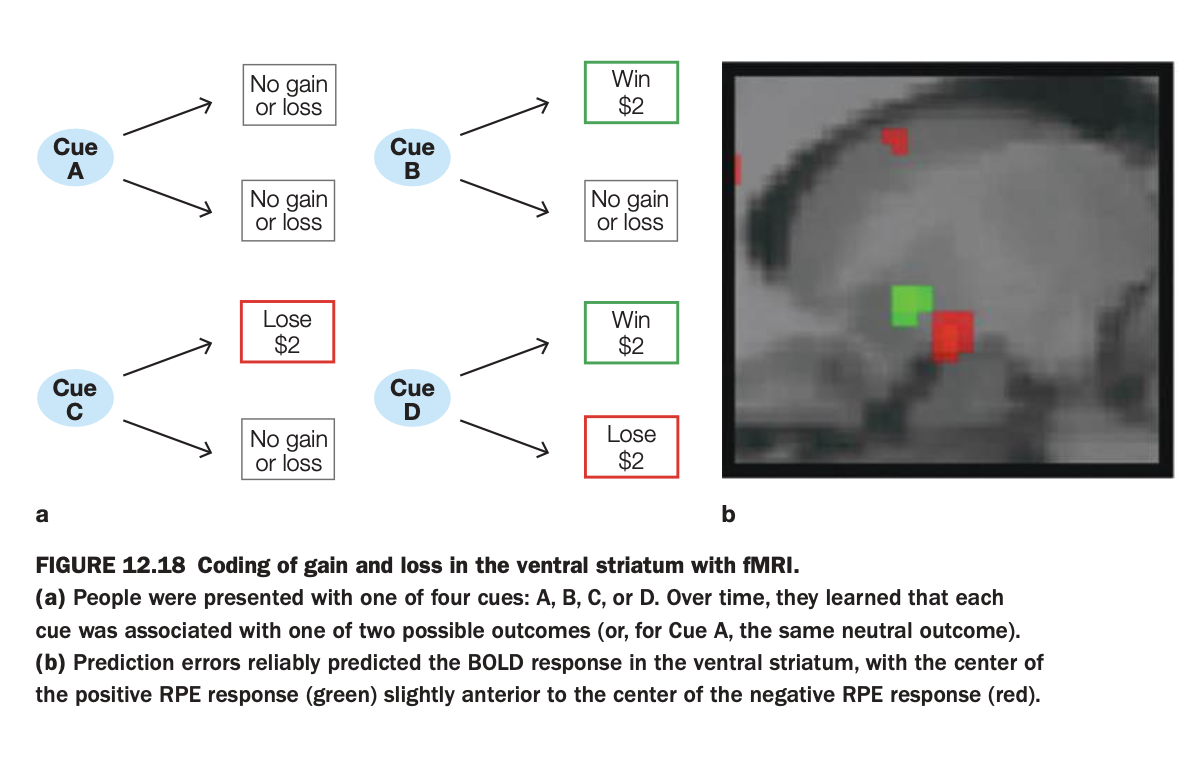

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how the human ventral striatum encodes prediction errors for both monetary gains and losses during a learning task.

2. Methods / task used

Participants saw one of four cues (A–D), each probabilistically associated with outcomes: always neutral (A), possible win (B), possible loss (C), or possible win versus loss (D).

While participants learned these cue–outcome contingencies, fMRI measured BOLD activity in the ventral striatum.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a schematizes the contingencies: Cue A → neutral; Cue B → win or neutral; Cue C → loss or neutral; Cue D → win or loss.

Panel b shows ventral striatal voxels where BOLD signal correlated with positive prediction errors (green, better‑than‑expected outcomes) and negative prediction errors (red, worse‑than‑expected outcomes).

4. Main findings

Both unexpected wins and unexpected avoided losses (positive prediction errors) activate a region of ventral striatum, whereas unexpected losses or missed gains (negative prediction errors) activate an adjacent but slightly more posterior region.

The centers of positive and negative prediction‑error responses are spatially shifted but overlapping, indicating partially segregated coding of gains versus losses within the same structure.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Ventral striatum supports reinforcement learning for both appetitive and aversive monetary outcomes by encoding prediction errors of opposite sign in nearby neural populations.

This organization helps explain how the same circuitry can drive approach toward rewarding cues and avoidance of loss‑predicting cues in human decision making.

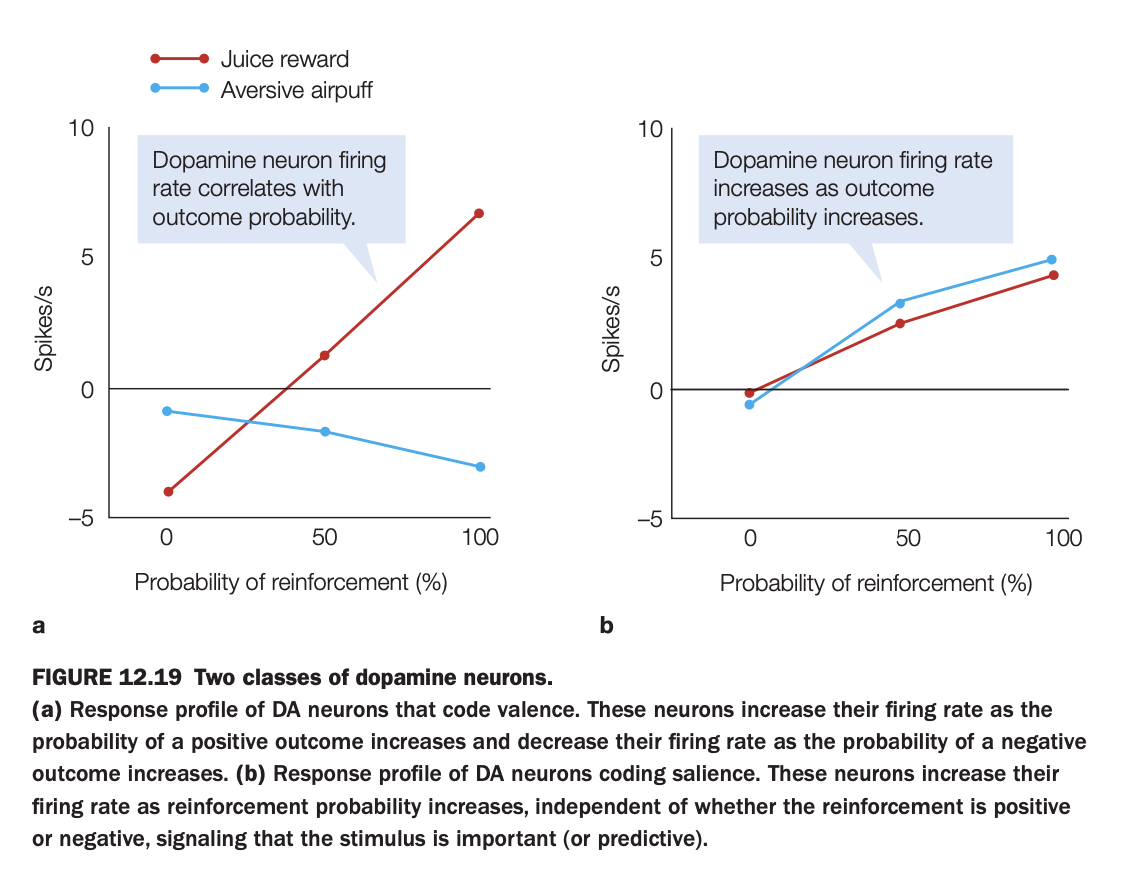

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To demonstrate that there are at least two functional classes of midbrain dopamine neurons: some code outcome valence (good vs bad), while others code motivational salience (importance) regardless of valence.

2. Methods / task used

Neural firing rates were recorded while animals experienced either a positive reinforcer (juice reward) or a negative reinforcer (aversive air puff) at different probabilities (0, 50, 100%).

For each neuron type, average firing rate was plotted as a function of reinforcement probability separately for juice and air puff.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a shows “valence‑coding” DA neurons: firing increases with the probability of juice but decreases with the probability of air puff, crossing zero around intermediate probabilities.

Panel b shows “salience‑coding” DA neurons: firing increases with reinforcement probability for both juice and air puff, with similar positive slopes for appetitive and aversive outcomes.

4. Main findings

Valence‑coding neurons treat rewards and punishments oppositely, signaling how good or bad the likely outcome is.

Salience‑coding neurons respond more whenever an outcome (good or bad) is more likely, highlighting stimuli that are predictive and behaviorally important.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Dopamine’s role is not unitary: some DA populations provide value signals for reinforcement learning, while others provide salience/attention signals that may influence orienting and arousal.

Understanding this heterogeneity helps reconcile why dopamine can be involved in both reward processing and responses to salient aversive events.

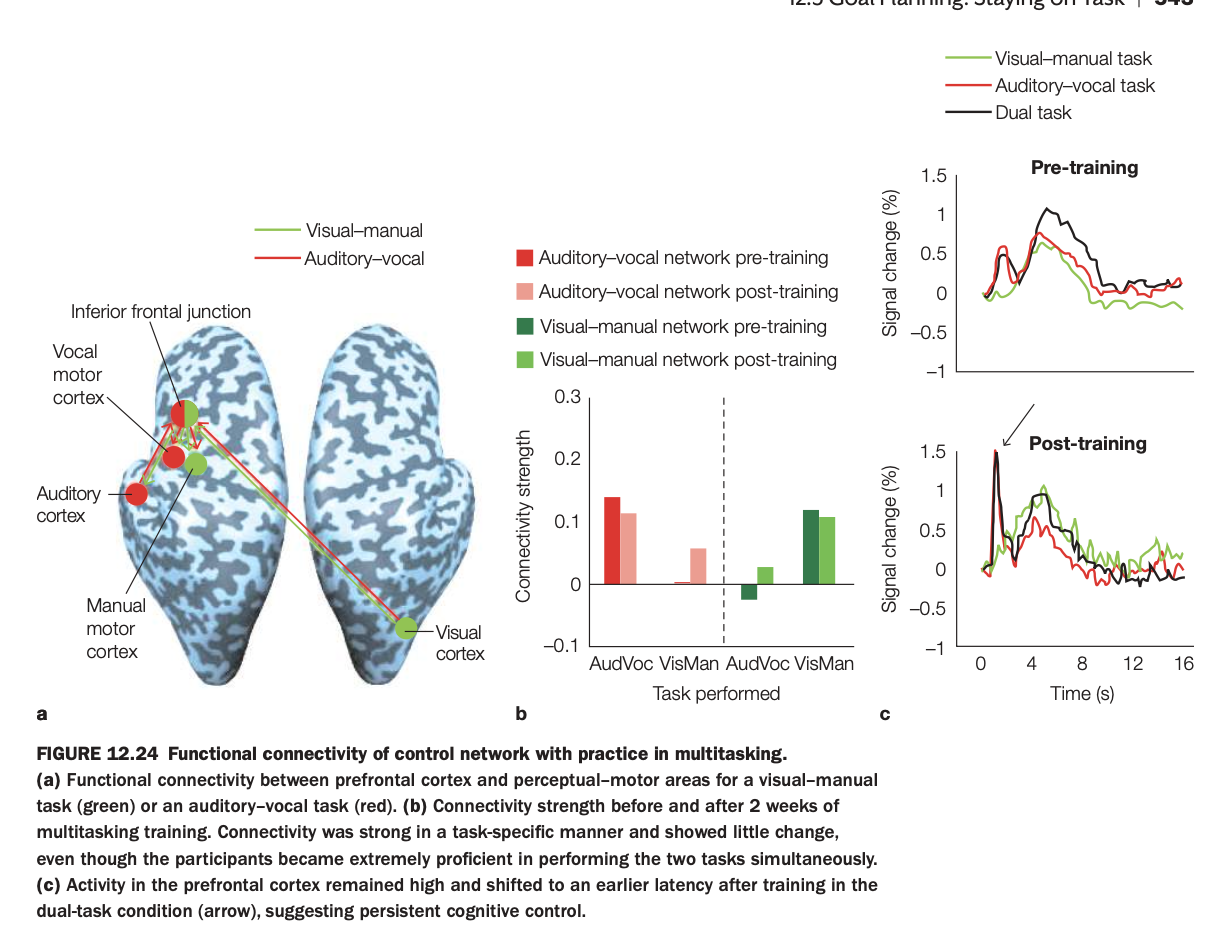

. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how functional connectivity within control networks and prefrontal activation patterns change with practice in dual‑task (multitasking) performance.

2. Methods / task used

Participants performed a visual–manual task and an auditory–vocal task separately and then together as a dual task, before and after two weeks of multitasking training.

fMRI measured connectivity between prefrontal cortex (inferior frontal junction) and sensory–motor regions (visual, auditory, vocal, manual motor cortices), and task‑evoked signal in prefrontal cortex.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a maps the task‑specific control networks: green nodes/edges for the visual–manual network and red for the auditory–vocal network, both linked to inferior frontal junction.

Panel b shows connectivity strength for each network during each task, pre‑ and post‑training: connectivity is strongest within the relevant network (e.g., visual–manual network during the visual–manual task) and changes little with training.

Panel c plots prefrontal time courses for single tasks and dual task, pre‑ vs post‑training: after training, dual‑task prefrontal activity peaks earlier but remains robust, indicating more efficient but still engaged control.

4. Main findings

Task‑specific connectivity between inferior frontal junction and the appropriate sensory–motor areas is stable and selective, even after extensive practice.

Training improves behavioral multitasking performance but does not eliminate prefrontal involvement; instead, prefrontal responses become earlier and perhaps more efficient in the dual‑task condition.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Cognitive control in multitasking relies on dedicated fronto‑sensory–motor networks that remain engaged even when tasks become highly practiced.

Practice leads to temporal reorganization rather than disengagement of prefrontal control, supporting models where automaticity reduces, but does not abolish, top‑down coordination in complex multitasking.

Using the 5‑question structure:

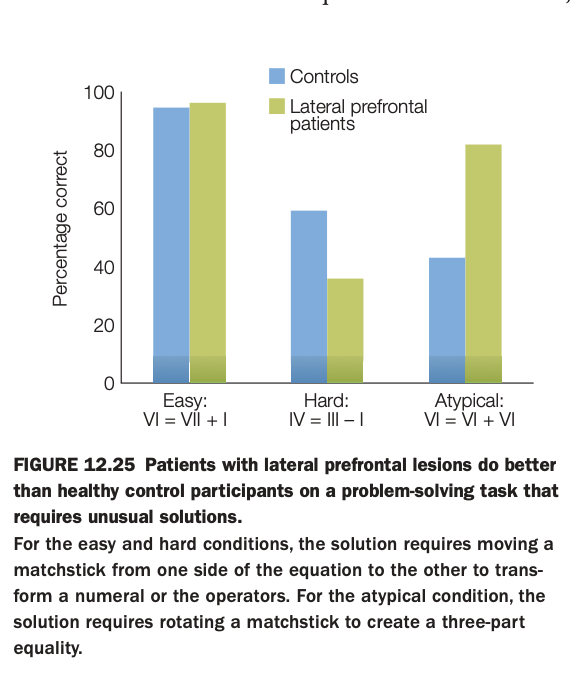

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show that patients with lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) lesions can outperform healthy controls on problem‑solving tasks that require atypical, insight‑based solutions, despite doing worse on more standard problems.

2. Methods / task used

Participants solved matchstick arithmetic problems of three types: easy, hard, and atypical.

Easy and hard problems could be solved by moving a stick to change a numeral or operator, whereas atypical problems required a more unusual transformation (e.g., rotating a stick to form a three‑part equality).

3. Panels and relationships

The bar graph plots percent correct for controls (blue) and LPFC patients (green) across the three conditions.

Controls outperform patients on the hard condition but perform similarly on easy problems, while patients do better than controls on the atypical condition.

4. Main findings

LPFC damage impairs performance on demanding but conventional problems that rely on maintaining and manipulating task rules.

However, the same patients are more likely than controls to discover atypical solutions, suggesting reduced top‑down constraints can sometimes facilitate creative insight.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Lateral prefrontal cortex supports goal maintenance and adherence to standard problem‑solving strategies, which is beneficial for routine tasks but can hinder flexible restructuring when an unconventional solution is needed.

This double pattern illustrates how executive control both enables complex cognition and can “overconstrain” thinking, limiting creativity in certain contexts.

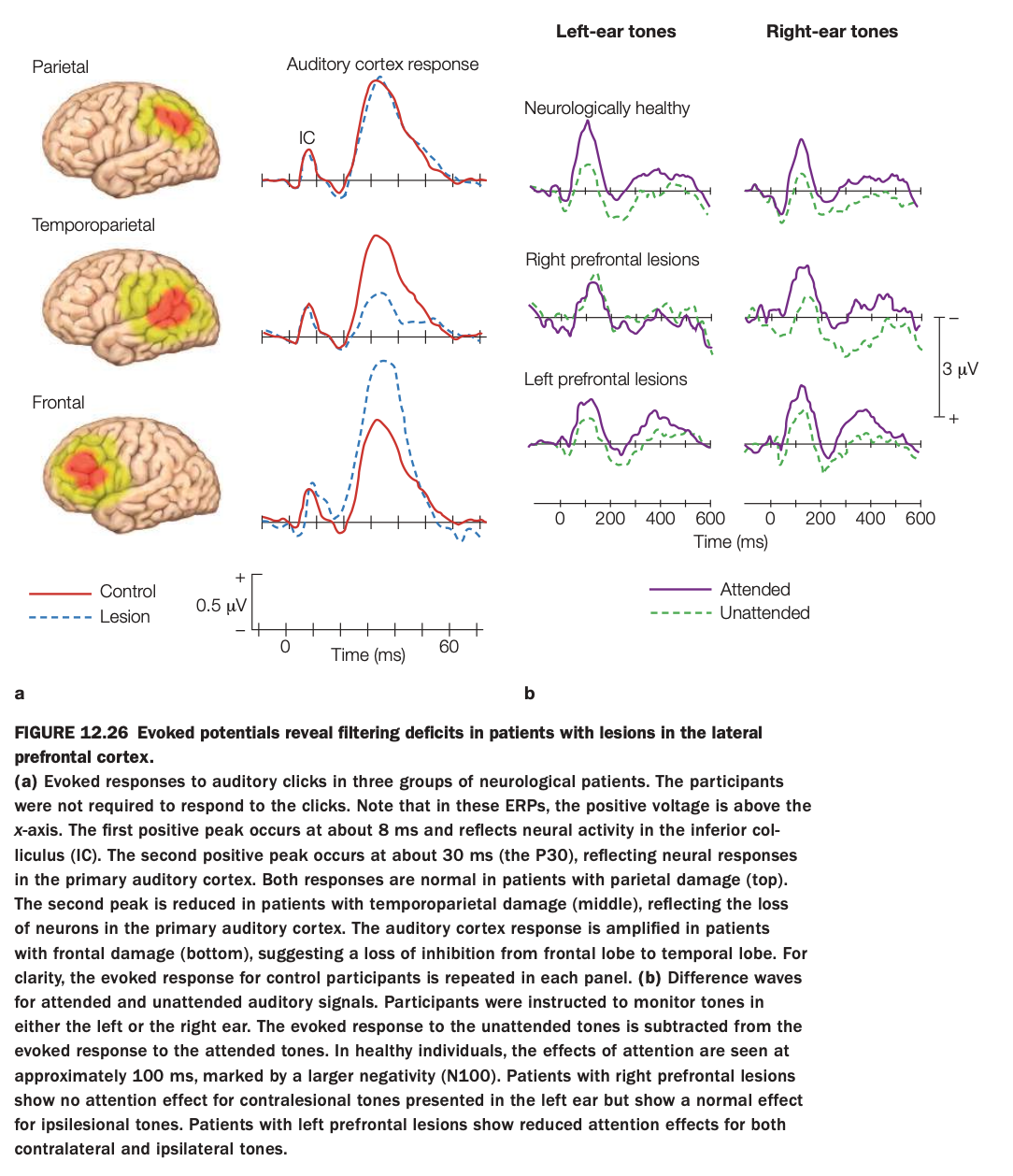

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how lesions in different parts of lateral prefrontal and temporoparietal cortex affect early sensory responses and attentional filtering of auditory stimuli, as measured by event‑related potentials (ERPs).

2. Methods / task used

Neurological patients with parietal, temporoparietal, or frontal lesions and controls heard auditory clicks or tones while ERPs were recorded.

In panel b, participants attended to tones in one ear while ignoring the other; difference waves (attended minus unattended) indexed attentional modulation of auditory cortex responses.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a compares early auditory‑evoked responses (around 8 ms IC peak and 30 ms P30) between controls (solid red) and lesion groups (dashed blue) for parietal, temporoparietal, and frontal damage.

Panel b shows attentional difference waves for left‑ and right‑ear tones in healthy controls, patients with right prefrontal lesions, and patients with left prefrontal lesions, separately for attended (purple) and unattended (green) conditions.

4. Main findings

Basic early auditory responses are normal with parietal lesions, reduced with temporoparietal lesions (loss of primary auditory neurons), and abnormally enlarged with frontal lesions, suggesting reduced frontal inhibition of temporal cortex.

In attention tasks, healthy participants show clear N100 attention effects; right prefrontal lesions abolish attention effects for contralesional (left‑ear) tones, and left prefrontal lesions reduce attention effects for both ears.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Temporoparietal regions are critical for generating normal primary auditory responses, whereas lateral prefrontal cortex is crucial for top‑down filtering of irrelevant auditory input.

Right PFC appears especially important for contralateral spatial attention, while left PFC contributes more bilaterally, supporting models of asymmetric but cooperative prefrontal control over sensory processing.

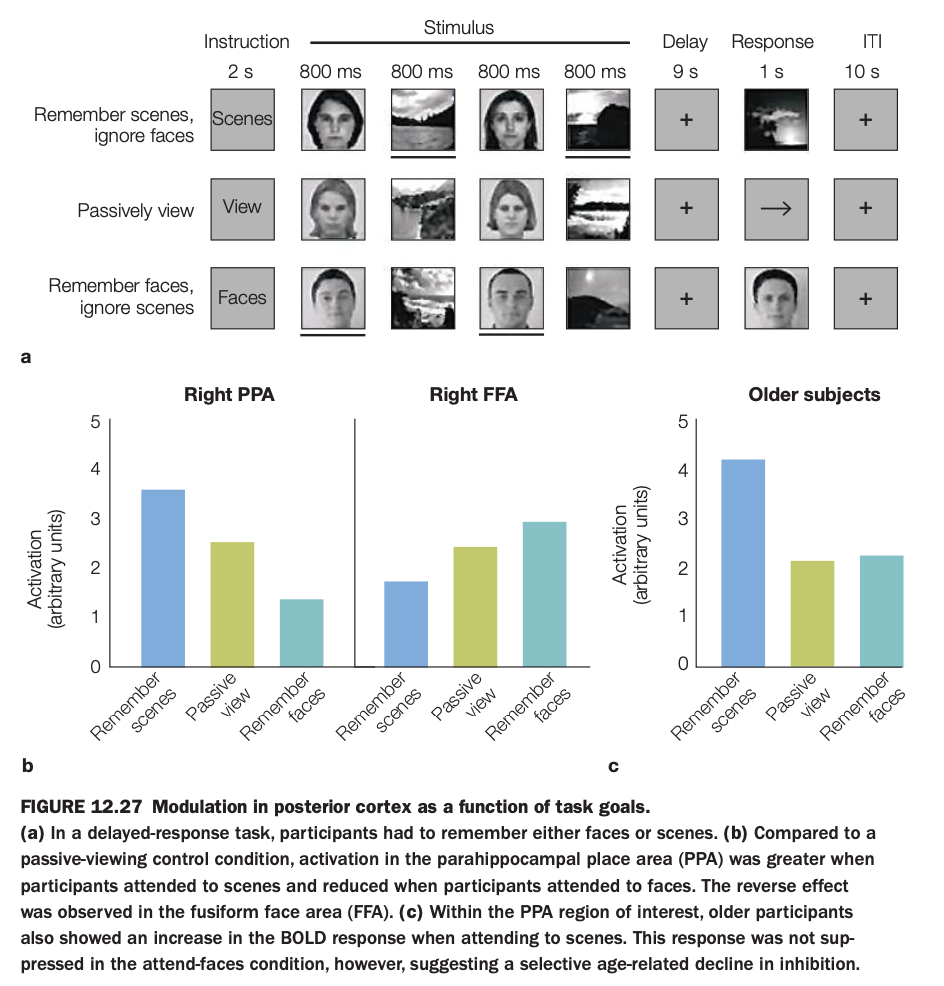

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how task goals (remembering faces vs scenes) modulate category‑selective activity in posterior cortex (PPA and FFA), and how this modulation changes with aging.

2. Methods / task used

In a delayed‑response fMRI task, participants were instructed on each trial either to remember scenes and ignore faces, remember faces and ignore scenes, or passively view mixed face–scene displays.

After a delay, they made a memory judgment about the task‑relevant category, allowing measurement of goal‑dependent BOLD responses in right parahippocampal place area (PPA) and right fusiform face area (FFA).

3. Panels and relationships

The top schematic shows trial structure with instructions, alternating face/scene stimuli, a long delay, and response/ITI periods.

Panel a presents bar graphs for younger adults: in PPA, activation is highest when remembering scenes and lowest when remembering faces; in FFA, the pattern reverses, with highest activation when remembering faces.

Panel c shows PPA responses in older adults, who exhibit strong activation when remembering scenes but less suppression when instructed to remember faces, relative to passive viewing.

4. Main findings

Goal‑directed attention enhances activity in the region selective for the attended category and suppresses it when that category is to be ignored, demonstrating top‑down modulation of posterior visual cortex.

Older adults still enhance PPA for scene memory, but they fail to fully suppress PPA when scenes are irrelevant, suggesting an age‑related decline in inhibitory control rather than in enhancement.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Posterior category‑selective regions are not purely stimulus‑driven; their activity is shaped by current task goals via control signals from frontoparietal networks.

Aging selectively weakens goal‑directed inhibition of irrelevant information, which may contribute to older adults’ greater susceptibility to distraction in memory tasks.

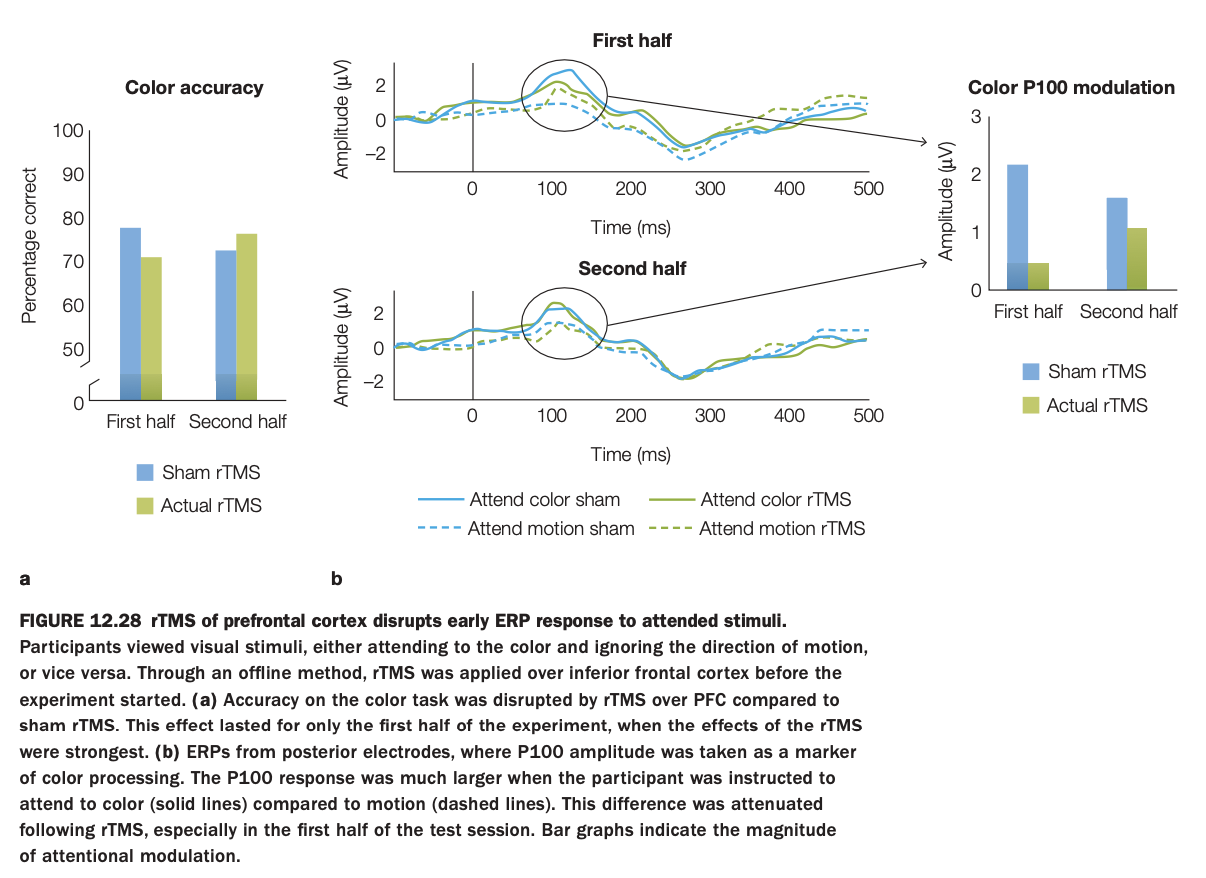

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To test whether disrupting prefrontal cortex with rTMS impairs early attentional modulation of visual processing and behavioral performance on a color‑attention task.

2. Methods / task used

Participants viewed moving colored stimuli and were cued either to attend to color and ignore motion or to attend to motion and ignore color.

Before the experiment, offline rTMS was applied over inferior frontal cortex (actual rTMS vs sham), then color‑discrimination accuracy and posterior ERPs (P100 component) were measured across the first and second halves of the session.

3. Panels and relationships

Left bar graph (a) shows color‑task accuracy: performance is worse with actual rTMS than sham in the first half but converges by the second half.

Middle ERPs (b) show P100 responses when attending color (solid) vs motion (dashed), with and without rTMS, for first and second halves; early attentional enhancement of P100 is clear in sham but reduced after rTMS, especially early in testing.

Right bar graph summarizes P100 modulation amplitude (attend‑color minus attend‑motion) for sham vs rTMS in each half, mirroring the behavioral pattern.

4. Main findings

rTMS over prefrontal cortex transiently reduces both color‑discrimination accuracy and the early P100 attention effect, indicating disrupted top‑down modulation of visual cortex.

These impairments are strongest in the first half of the session, suggesting that the rTMS effect wanes over time.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Inferior frontal cortex is causally involved in amplifying early sensory responses to attended features, not just late decision processes.

When prefrontal control is disrupted, visual cortex shows less differential response to attended versus unattended features, leading to poorer selective performance.

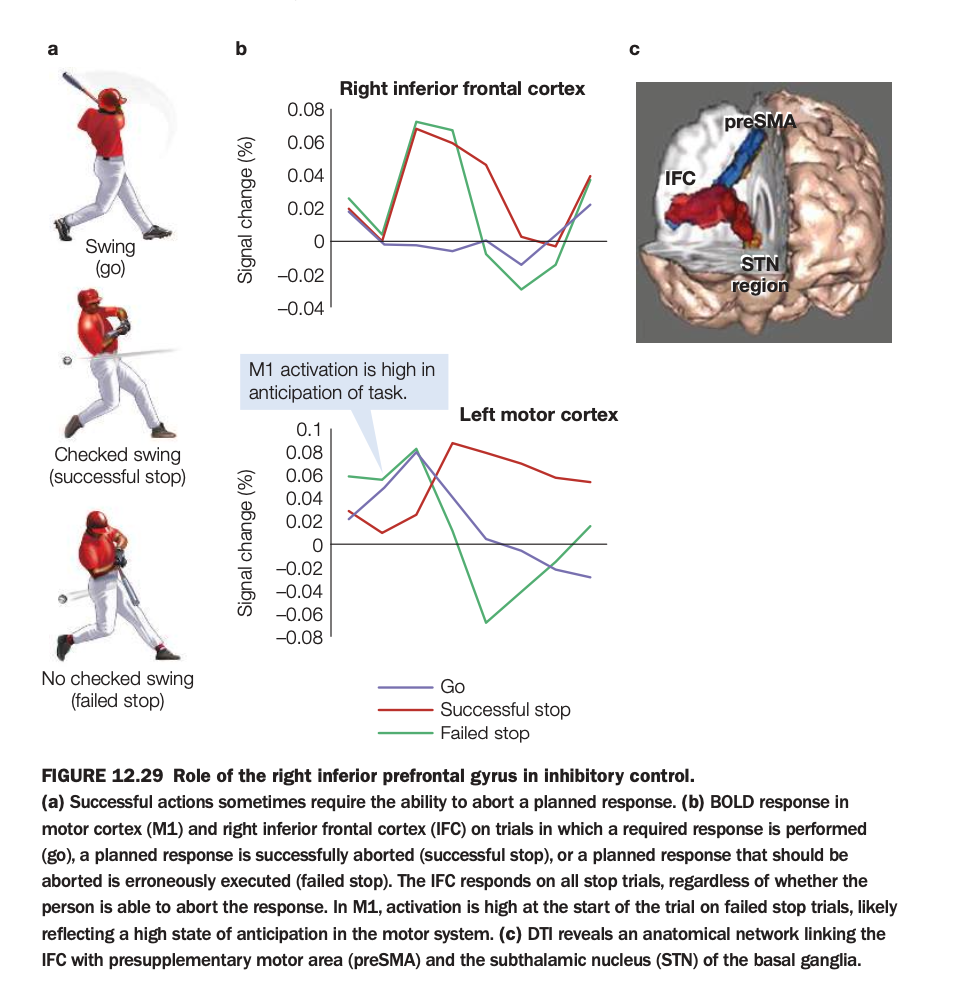

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how right inferior frontal cortex (IFC) and connected regions support inhibitory control when a planned movement must be stopped, using a stop‑signal–like task.

2. Methods / task used

Participants prepared a motor response (like swinging a bat) on go trials, but on some trials a stop signal instructed them to abort the movement, producing successful‑stop or failed‑stop trials.

fMRI measured BOLD responses in right IFC and left primary motor cortex (M1), and diffusion imaging identified structural connections from IFC to preSMA and subthalamic nucleus (STN).

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a illustrates behavior: full swing on go, checked swing on successful stop, and incomplete stopping on failed stop.

Panel b shows time courses: in right IFC, activation rises on both successful and failed stop trials but not on go trials, indicating engagement whenever stopping is required; in M1, activation is highest on failed stops, reflecting strong movement preparation.

Panel c depicts the network linking IFC with preSMA and STN, suggesting a pathway by which frontal signals can rapidly suppress motor output.

4. Main findings

Right IFC is selectively activated on stop trials regardless of outcome, consistent with triggering an inhibitory command.

Greater early M1 activity on failed stops suggests that when motor drive is too strong or too early, IFC‑initiated inhibition cannot prevent the action.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Inhibitory control relies on a right‑lateralized fronto‑basal‑ganglia circuit (IFC–preSMA–STN) that can rapidly cancel actions already in preparation.

Failures of this system—due to weak IFC engagement or overpowering motor activation—may underlie impulsive behaviors and clinical deficits in stopping actions.

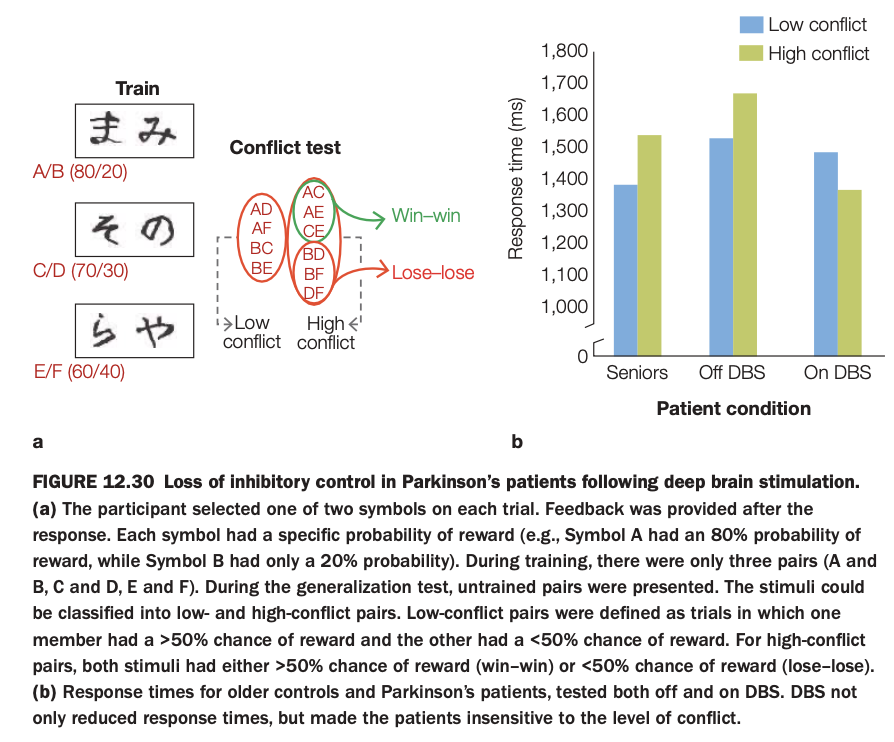

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To examine how deep brain stimulation (DBS) in Parkinson’s disease affects inhibitory control during value‑based decision making, especially when choices involve conflict between similarly valued options.

2. Methods / task used

Participants first learned reward probabilities for symbol pairs (A/B, C/D, E/F), where one symbol in each pair was more frequently rewarded than the other.

In a later “conflict test,” new combinations of symbols were presented without feedback: some low‑conflict pairs combined a likely winner with a likely loser, while high‑conflict pairs combined two likely winners (win–win) or two likely losers (lose–lose).

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a schematizes training contingencies and how test pairs are classified into low‑ and high‑conflict sets.

Panel b shows response times for healthy seniors, Parkinson’s patients off DBS, and the same patients on DBS, separately for low‑ and high‑conflict trials.

4. Main findings

Healthy seniors and PD patients off DBS are slower on high‑conflict than low‑conflict trials, reflecting normal conflict‑induced caution.

When DBS is turned on, PD patients’ overall response times speed up and the difference between high‑ and low‑conflict trials shrinks, indicating reduced sensitivity to conflict.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

DBS in basal ganglia circuits can impair inhibitory control, making patients less likely to slow down when choices are difficult or ambiguous.

This supports the idea that frontostriatal loops normally use conflict signals to adjust decision thresholds, and that overstimulation can bias behavior toward faster, less controlled responding.

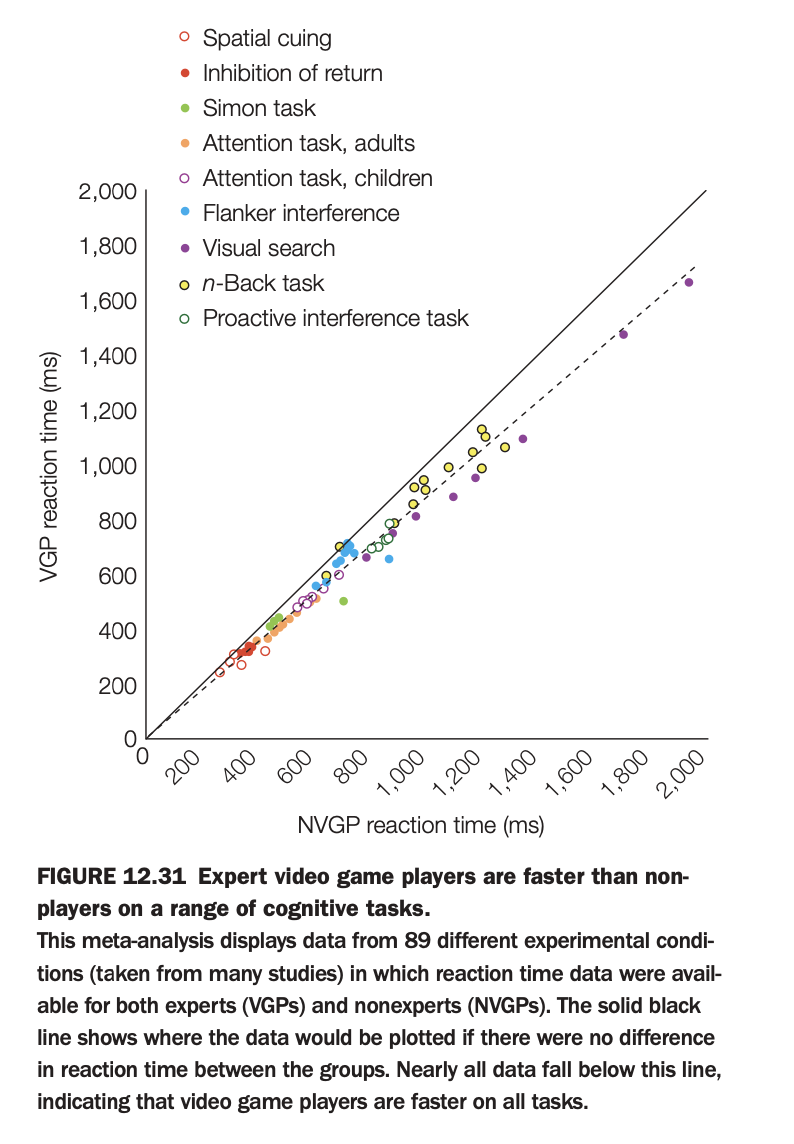

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To summarize evidence that expert video‑game players (VGPs) respond faster than non–video‑game players (NVGPs) across a wide variety of cognitive tasks.

2. Methods / task used

The figure is a meta‑analysis aggregating reaction‑time data from 89 experimental conditions across many studies, each reporting RTs for VGPs and NVGPs on tasks such as spatial cuing, visual search, flanker, Simon, n‑back, and interference paradigms.

Each point plots the mean RT for NVGPs on the x‑axis against the corresponding mean RT for VGPs on the y‑axis, color‑coded by task type.

3. Panels and relationships

A single scatterplot compares VGP vs NVGP reaction times; the solid diagonal line indicates where points would lie if both groups were equally fast.

The dashed regression line shows the best‑fit relationship between VGP and NVGP RTs across tasks.

4. Main findings

Nearly all points fall below the equality line, meaning VGPs are faster than NVGPs across almost every task type included.

The regression line lying below the diagonal confirms a consistent RT advantage for gamers that scales with task difficulty (slower tasks show larger absolute differences).

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Extensive action video‑game experience is associated with broadly enhanced speed of perceptual decision making and attentional processing, not just task‑specific practice effects.

These data support the view that certain types of gaming can train domain‑general mechanisms like visual attention, task switching, and motor readiness.

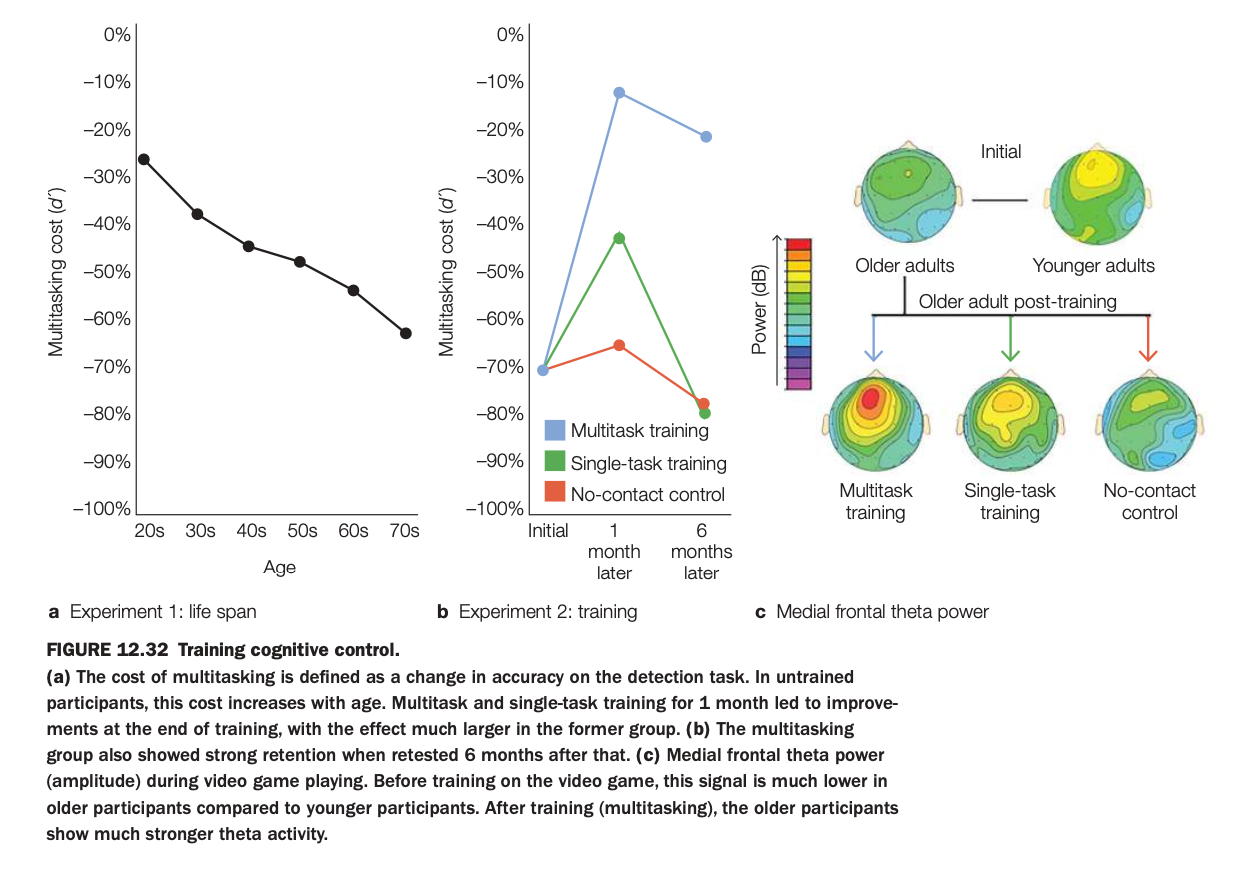

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how multitasking ability declines with age but can be improved in older adults through multitask training, and how these improvements relate to medial frontal theta power, a neural marker of cognitive control.

2. Methods / tasks used

Experiment 1 measured multitasking cost (drop in detection accuracy when dual‑tasking vs single‑tasking) across adults from their 20s to 70s.

Experiment 2 randomly assigned older adults to one month of video‑game multitask training, single‑task training, or a no‑contact control, then retested them 1 and 6 months later while recording medial frontal theta during game play.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a shows that multitasking cost becomes more negative (worse) with age, indicating increasing interference in untrained participants.

Panel b plots older adults’ multitasking cost over time: the multitask‑training group improves dramatically at 1 month and largely maintains gains at 6 months, whereas single‑task and no‑contact groups show little change.

Panel c shows scalp maps of medial frontal theta: initially older adults have lower theta than younger adults; after training, only the multitask‑training group shows a strong increase in medial frontal theta power.

4. Main findings

Age is associated with larger multitasking costs, but targeted multitask training can substantially reduce these costs and benefits persist for at least 6 months.

Training‑related performance gains are accompanied by enhanced medial frontal theta activity, suggesting strengthened control‑network engagement.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Cognitive control and multitasking are plastic in older adulthood and can be improved through appropriate practice rather than being fixed deficits.

Increases in medial frontal theta power appear to be a neural signature of this training‑induced improvement, linking oscillatory activity in control networks to real‑world multitasking performance.

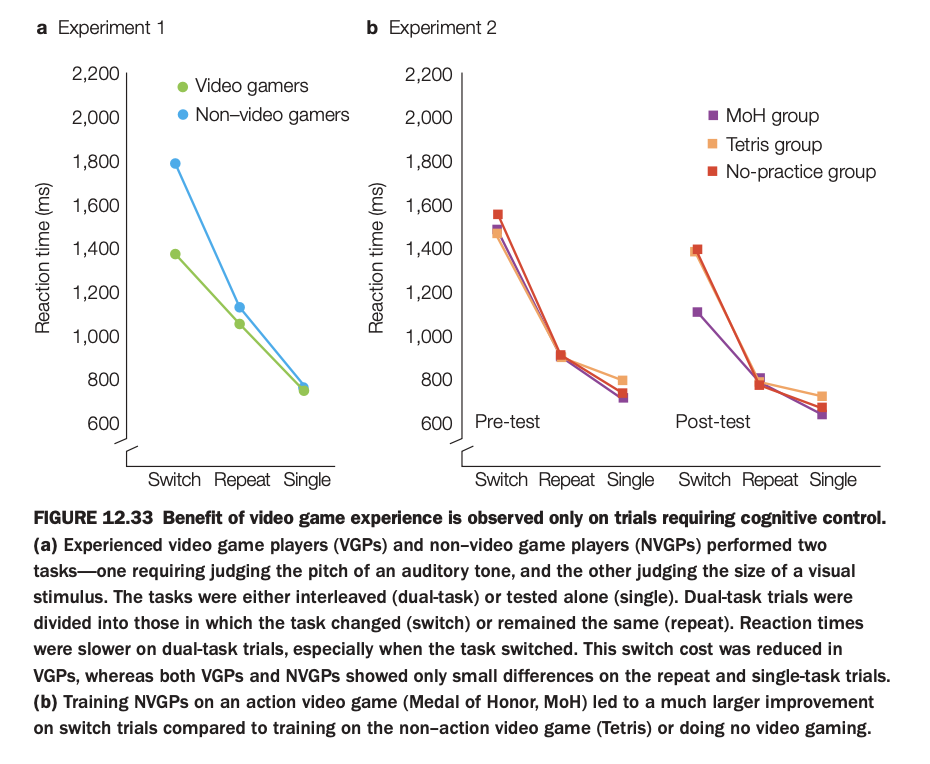

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show that both prior and newly acquired action video game experience selectively improve performance on tasks that require cognitive control, particularly task switching.

2. Methods / tasks used

In Experiment 1, experienced video game players (VGPs) and non‑video game players (NVGPs) performed two interleaved tasks (auditory pitch judgment and visual size judgment) under dual‑task conditions that either repeated the same task or required switching, plus single‑task blocks.

In Experiment 2, NVGPs were trained for several weeks on an action game (Medal of Honor, MoH), a non‑action game (Tetris), or had no practice, and then completed the same switching paradigm at pre‑ and post‑test.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a shows that VGPs are faster than NVGPs mainly on switch trials, with smaller advantages on repeat and single trials, indicating reduced switch cost.

Panel b shows pre‑ and post‑test reaction times for the three training groups: after training, the MoH (action) group exhibits the largest reduction in switch RTs, whereas Tetris and no‑practice groups change little, especially on switch trials; repeat and single‑task RTs are similar across groups.

4. Main findings

Both long‑term gamers and individuals newly trained on action games show specific benefits for dual‑task trials that require switching between tasks, not for easier repeat or single trials.

Non‑action gaming or no practice does not confer this selective improvement in cognitive control.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Action video game play appears to train cognitive control processes such as task switching and flexible allocation of attention, rather than simply speeding motor responses.

These results support the idea that certain complex, fast‑paced games can serve as targeted interventions to enhance executive control functions.

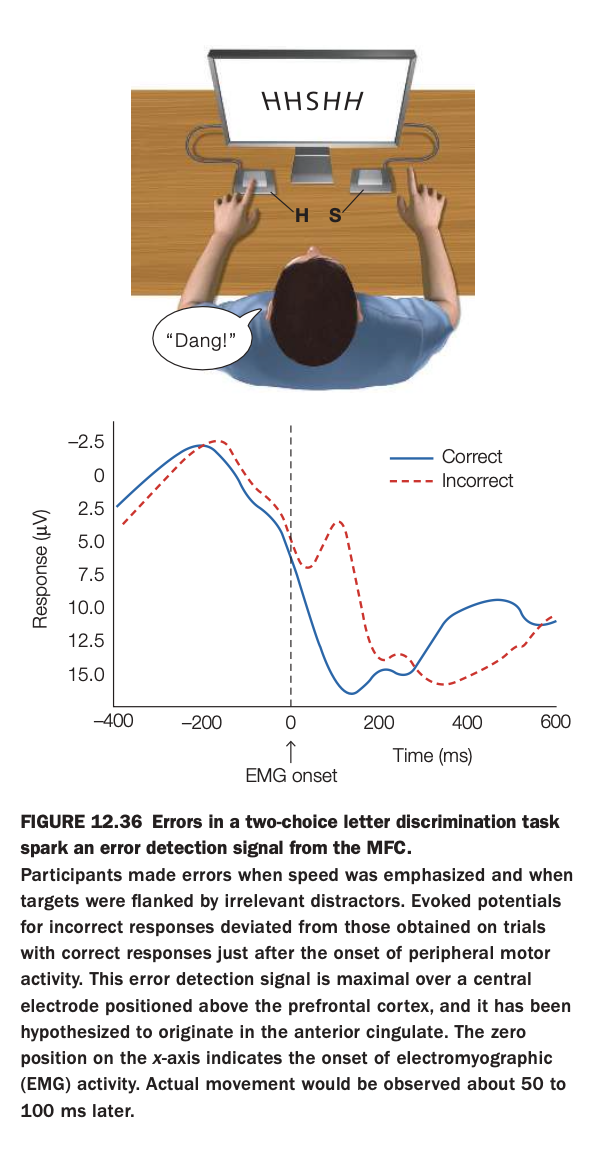

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To demonstrate that making an incorrect response in a speeded choice task elicits a distinct error‑related brain signal originating in medial frontal cortex, time‑locked to the onset of motor activity.

2. Methods / task used

Participants performed a two‑choice letter discrimination task (e.g., press left key for H, right key for S) while ignoring flanking distractor letters, with high emphasis on speed.

Electroencephalography (EEG) and electromyography (EMG) were recorded; ERPs were aligned to EMG onset to compare brain activity on correct versus incorrect trials.

3. Panels and relationships

The top cartoon illustrates the task setup, with central target letter and flankers plus left/right key responses.

The lower plot shows a central‑scalp ERP: after EMG onset (time 0), the waveform for incorrect trials (red dashed) diverges from that for correct trials (blue), producing a prominent negativity associated with error detection.

4. Main findings

A reliable error‑related potential appears shortly after movement onset on incorrect trials but not on correct trials.

This signal is maximal over medial frontal electrodes and is thought to originate in anterior cingulate cortex, reflecting rapid monitoring of response outcomes.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Medial frontal cortex continuously evaluates actions and generates fast error signals that can guide adjustments in behavior on subsequent trials.

Such error‑monitoring mechanisms are central to cognitive control, enabling people to detect when they “slip” and to adapt strategies or response thresholds accordingly.

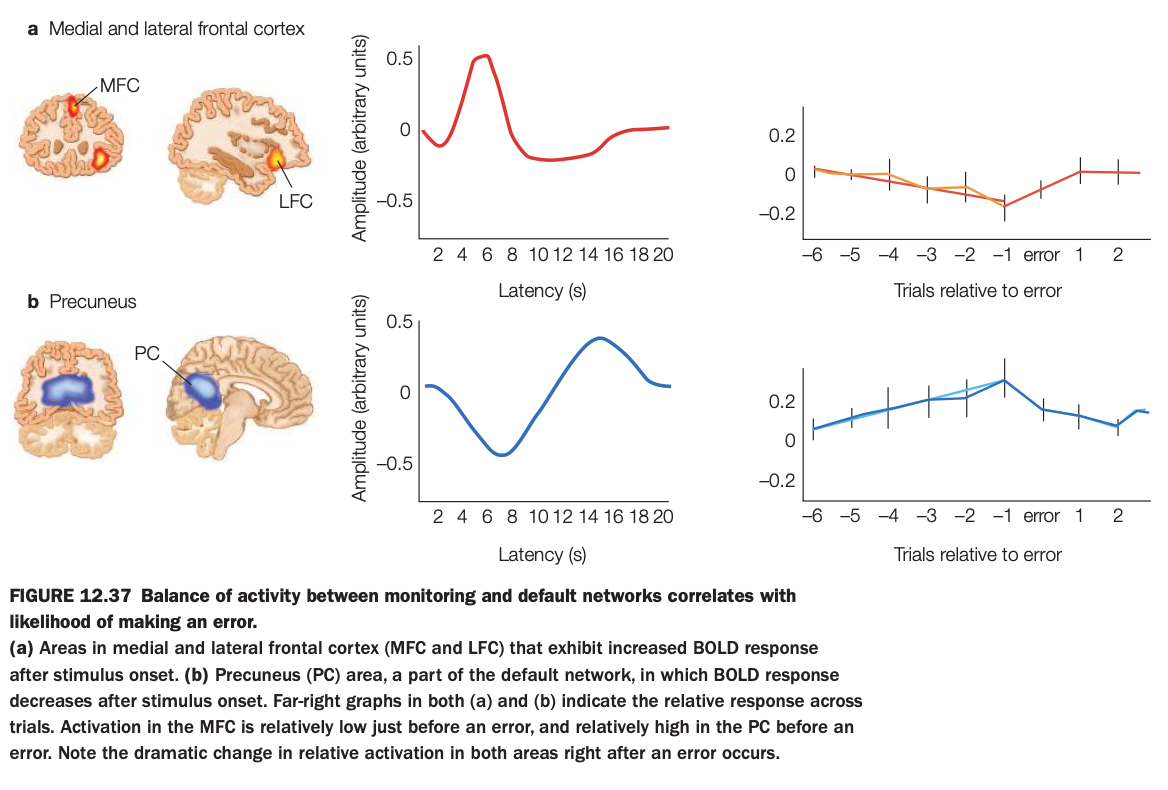

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show that the relative balance of activity between a monitoring network in medial/lateral frontal cortex and the default‑mode precuneus predicts the likelihood of upcoming errors.

2. Methods / task used

Participants performed a challenging task while fMRI measured BOLD responses in medial frontal cortex (MFC), lateral frontal cortex (LFC), and precuneus (PC), a key default‑mode region.

Trial sequences were aligned around error trials to examine how activity in these regions changed in the several trials before and after an error.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a (top) shows frontal regions where activity increases after stimulus onset, their averaged hemodynamic response, and a plot of relative MFC/LFC activity across trials surrounding an error, which dips below zero just before errors.

Panel b (bottom) shows the precuneus, where activity decreases after stimulus onset, its time course, and trial‑aligned data showing that PC activity rises above baseline before an error and drops afterward.

4. Main findings

Immediately before an error, frontal monitoring regions are relatively underactive while the precuneus/default‑mode region is relatively overactive, indicating a shift away from task‑focused control.

Right after an error, this balance reverses, with increased frontal activation and reduced precuneus activity, consistent with reengagement of control.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Moment‑to‑moment fluctuations in the competition between control networks (MFC/LFC) and the default network (PC) help determine whether a lapse of attention will occur.

Errors are more likely when default‑mode activity dominates and less likely when monitoring regions are strongly engaged, supporting dynamic‑balance models of attentional control.

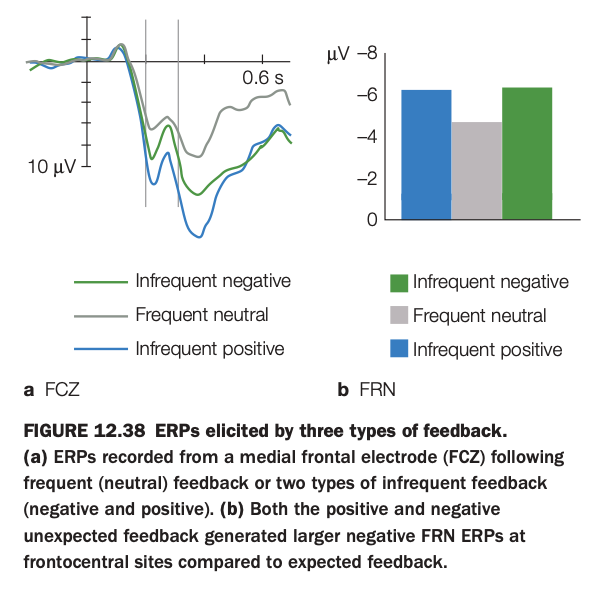

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how medial frontal event‑related potentials (ERPs) differ when feedback is frequent/expected versus infrequent/unexpected, and to illustrate the feedback‑related negativity (FRN) component.

2. Methods / task used

Participants performed a task that produced three types of feedback: frequent neutral outcomes and two kinds of infrequent, unexpected outcomes (negative and positive).

ERPs were recorded from a medial frontal electrode (FCz) time‑locked to feedback onset and averaged separately for each feedback type.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a shows ERP waveforms: frequent neutral feedback (gray) elicits a relatively small negativity, whereas both infrequent negative (green) and infrequent positive (blue) feedback produce a larger negative deflection around the FRN latency window.

Panel b summarizes FRN amplitude as bar graphs, confirming that both kinds of infrequent feedback evoke more negative FRN values than frequent neutral feedback at frontocentral sites.

4. Main findings

FRN amplitude is driven more by outcome expectancy (infrequent vs frequent) than by valence (positive vs negative) of feedback.

Unexpected positive and negative outcomes alike generate larger medial frontal negativities compared with expected neutral outcomes.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Medial frontal cortex signals the detection of unexpected feedback events, consistent with a role in monitoring prediction errors or surprise rather than simply coding reward versus punishment.

Such FRN responses provide a rapid teaching signal that can guide learning from both unexpectedly good and bad outcomes.

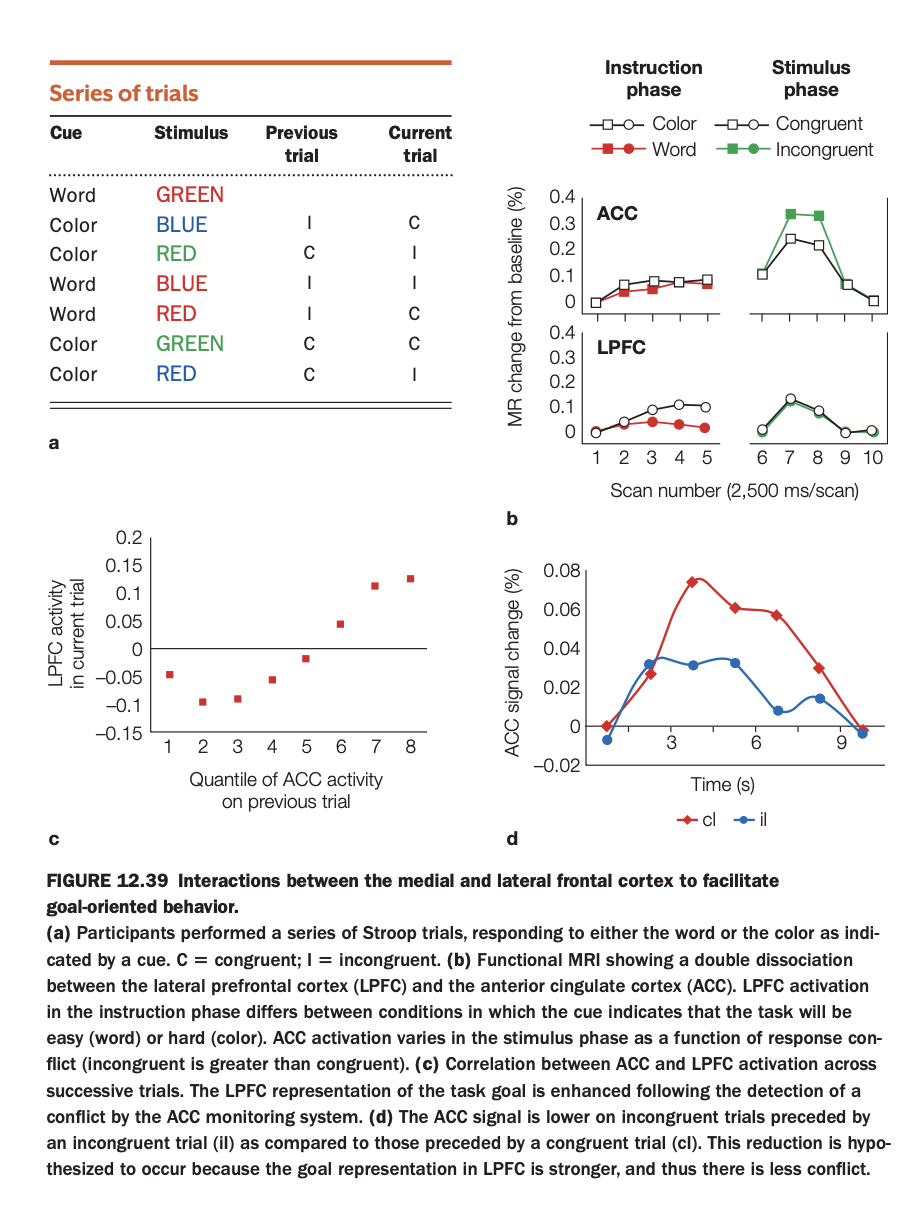

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To illustrate how anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; medial frontal) and lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) interact across trials during a Stroop task to support goal‑directed behavior and conflict adaptation.

2. Methods / task used

Participants performed cued Stroop trials, sometimes naming the ink color and sometimes reading the word, with stimuli being congruent or incongruent; trial sequences allowed comparison of current‑trial conflict given previous‑trial ACC activity.

fMRI measured BOLD responses in ACC and LPFC during instruction and stimulus phases, and trial‑by‑trial relationships between these regions were analyzed.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a lists example trial sequences labeling previous and current trials as congruent (C) or incongruent (I).

Panel b shows a double dissociation: LPFC activates more when the cue indicates the harder “color‑naming” task during the instruction phase, whereas ACC activates more for incongruent than congruent stimuli during the stimulus phase.

Panel c plots LPFC activity on the current trial as a function of ACC activity on the previous trial, showing a positive correlation; panel d shows that ACC conflict signal is reduced on incongruent trials that follow an incongruent trial (iI) relative to incongruent trials following congruent trials (cI).

4. Main findings

ACC monitors response conflict on a given trial, and higher ACC activation predicts stronger LPFC activation on the next trial, consistent with conflict‑driven up‑regulation of control.

Consequently, ACC conflict signals diminish on successive incongruent trials (iI), indicating successful proactive control adjustment and reduced conflict.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Medial frontal cortex (ACC) acts as a performance monitor that detects conflict, while LPFC implements task goals; their interaction enables adaptive control across trials.

This cortico‑cortical loop explains phenomena like conflict adaptation in the Stroop task and supports broader models where monitoring signals trigger strategic adjustments in prefrontal control systems.

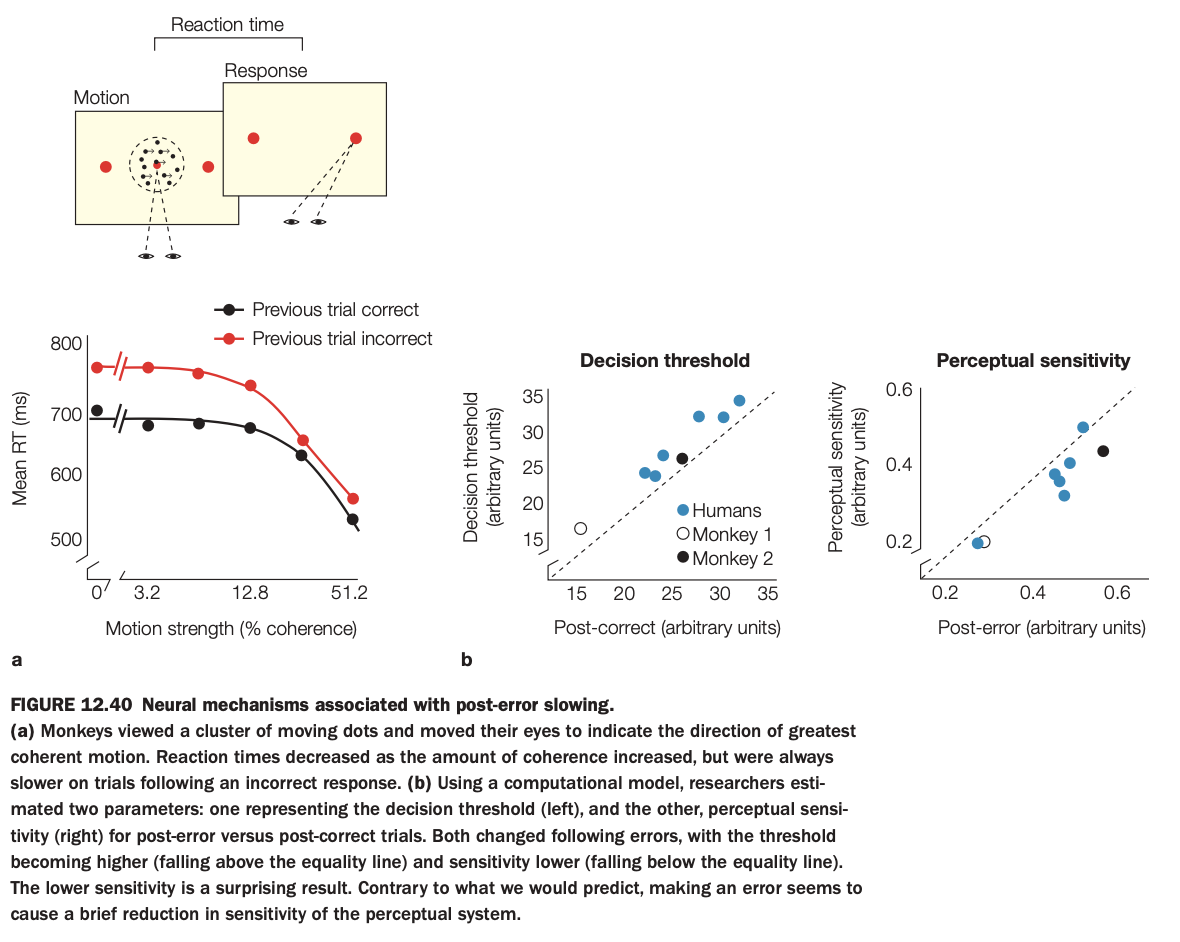

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show how making an error leads to post‑error slowing in a motion‑discrimination task and to identify whether this behavioral adjustment reflects changes in decision threshold, perceptual sensitivity, or both.

2. Methods / task used

Monkeys viewed random‑dot motion and made eye‑movement choices indicating motion direction; reaction time and accuracy were measured as motion coherence varied.

Using a drift‑diffusion–type computational model, researchers estimated decision threshold and perceptual sensitivity on trials following correct versus incorrect responses, and compared similar effects in humans and two monkeys.

3. Panels and relationships

Panel a plots mean reaction time versus motion strength, separately for trials preceded by correct (black) or incorrect (red) responses; RTs are consistently slower after errors, especially at low motion coherence.

Panel b shows scatterplots: left graph compares decision thresholds post‑correct versus post‑error (points above the diagonal indicate higher thresholds after errors); right graph compares perceptual sensitivity post‑correct versus post‑error (points below the diagonal indicate reduced sensitivity after errors).

4. Main findings

After errors, subjects adopt a higher decision threshold, leading to slower but more cautious decisions, and also show a transient reduction in perceptual sensitivity.

Both humans and monkeys exhibit this pattern, suggesting conserved mechanisms of post‑error adjustment across species.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Post‑error slowing reflects not only strategic caution (raising thresholds) but also a brief disruption of perceptual processing itself.

Error‑monitoring systems therefore influence both decision policy and sensory gain, helping the brain balance speed and accuracy after mistakes.

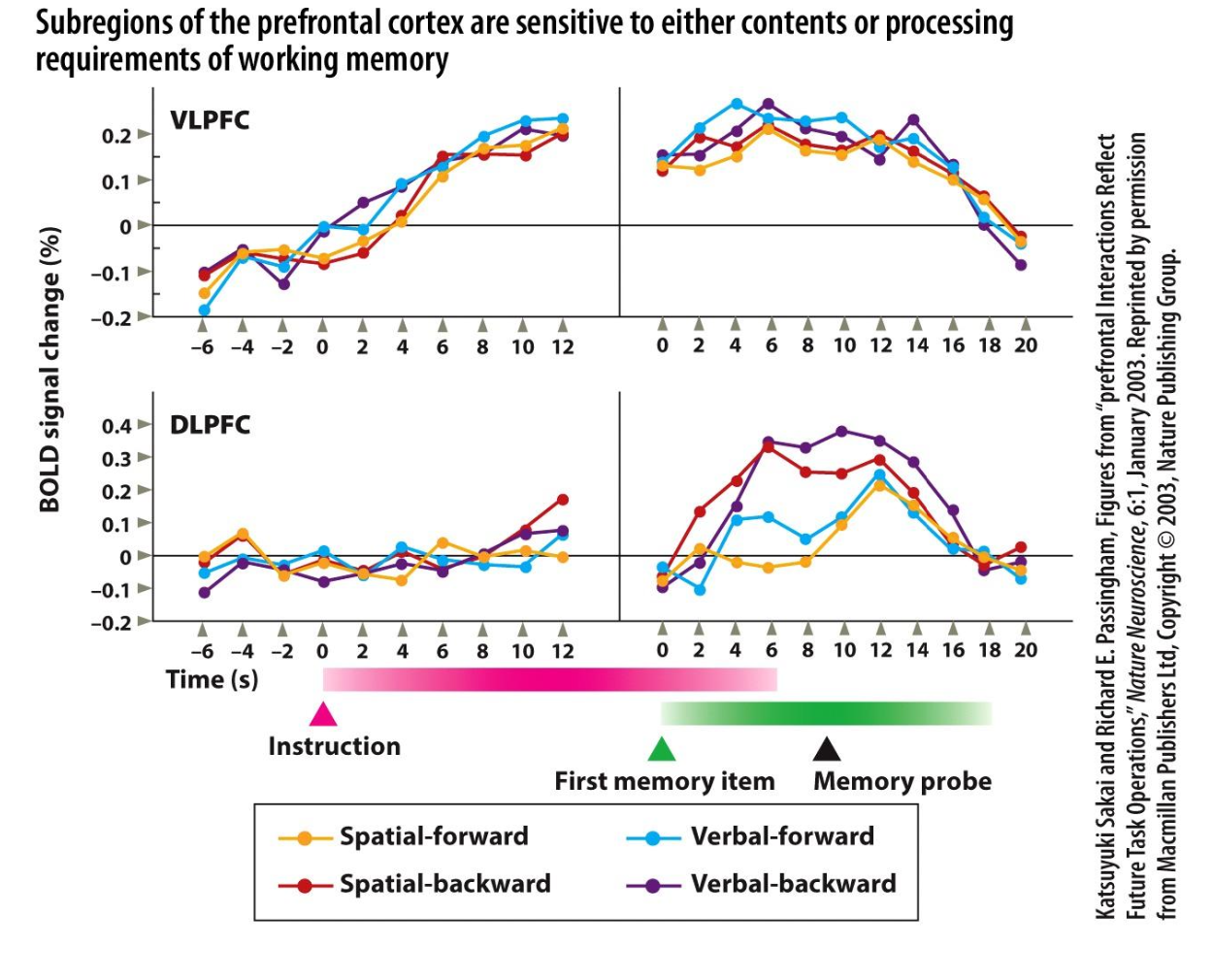

1. Purpose of the study/figure

To show that different subregions of prefrontal cortex specialize for either the contents of working memory (spatial vs verbal information) or the processing demands placed on that content (simple maintenance vs backward manipulation).

2. Methods / task used

Participants performed four delayed working‑memory tasks: spatial‑forward, spatial‑backward, verbal‑forward, and verbal‑backward, with instruction, memory encoding, delay, and probe periods while BOLD fMRI was recorded.

Forward tasks required simple maintenance and recall in presented order, whereas backward tasks required mentally reversing the sequence before responding, increasing processing demands.

3. Panels and relationships

Time‑courses are shown separately for ventrolateral PFC (VLPFC, top) and dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC, bottom), aligned to instruction and then to the memory period.

Colored lines indicate the four task types: spatial‑forward (yellow), spatial‑backward (red), verbal‑forward (blue), and verbal‑backward (purple) across the trial, allowing comparison of content (spatial vs verbal) and process (forward vs backward) effects within each region.

4. Main findings

In VLPFC, spatial and verbal tasks with the same processing demand produce similar activation magnitudes and time‑courses, indicating sensitivity mainly to stimulus domain (spatial vs verbal content).

In DLPFC, backward versions of both spatial and verbal tasks elicit stronger and more prolonged activity than forward versions, showing that this region is tuned to manipulation/processing demands rather than content type.

5. Neuroscientific / psychological implications

Working memory is implemented by a division of labor within PFC: VLPFC maintains modality‑specific representations, while DLPFC supports higher‑order operations such as reordering and transforming those representations.

This functional specialization explains why lesions or disruption of DLPFC disproportionately impair complex, manipulation‑heavy tasks (like backward span) while leaving simple maintenance relatively preserved.