Cognitive Psychology: Mental Processes and their Neural Substrates (Quiz 1)

1/30

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

31 Terms

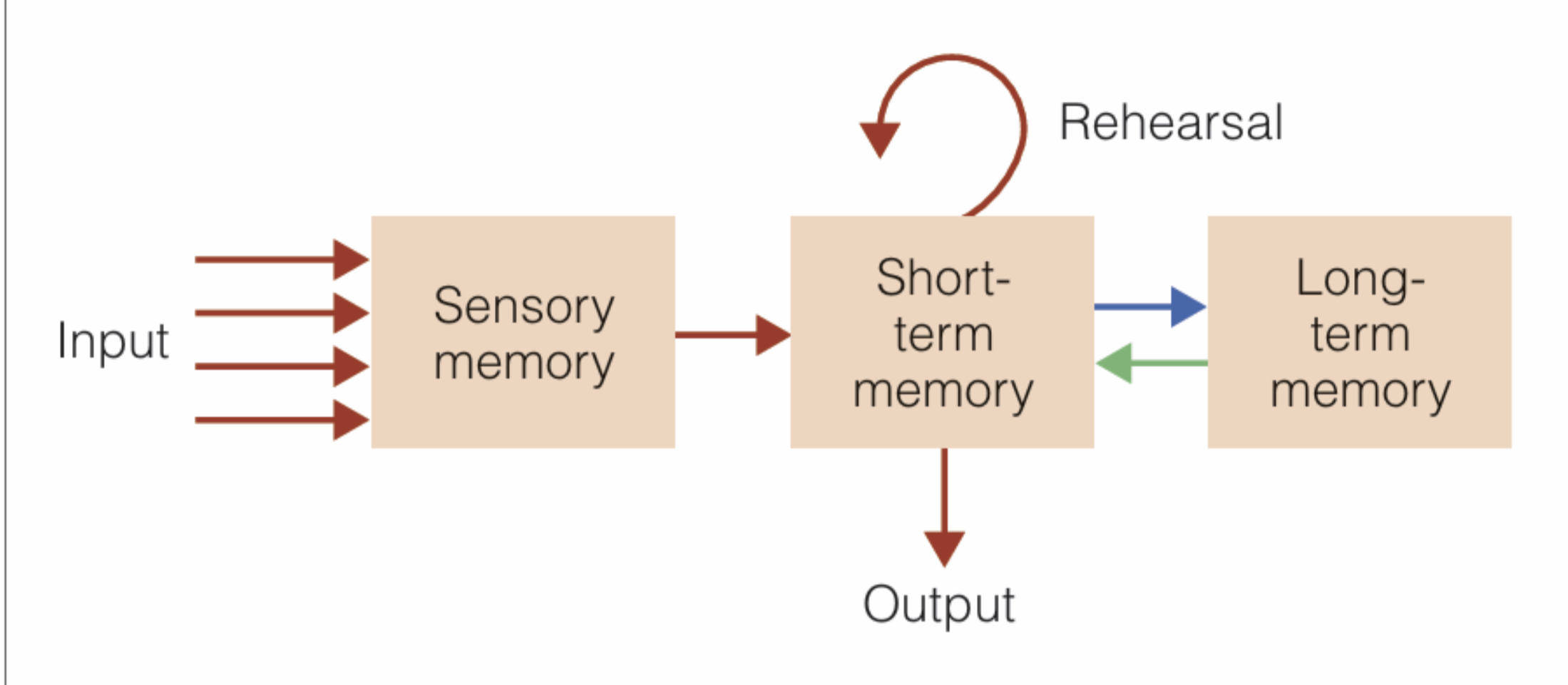

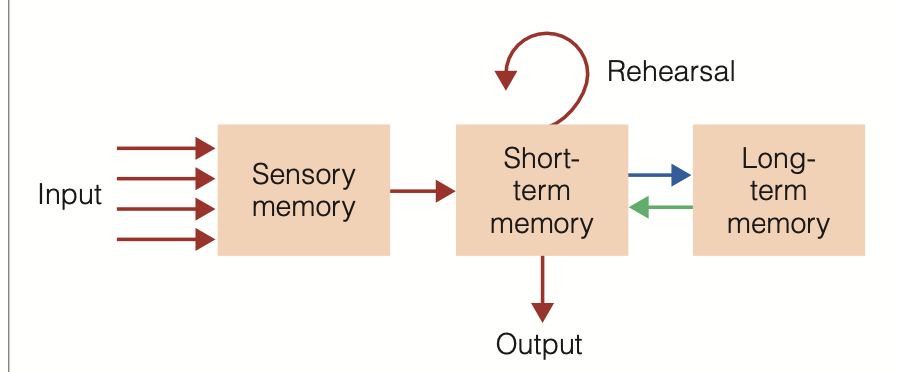

Atkinson-Shiffrin model - a model which describes how human memory works

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages:

1) Sensory Memory- storage of brief sensory events, such as sights, sounds, and tastes

2) Short-Term Memory- is a temporary storage system that processes incoming sensory memory; sometimes it is called working memory. Short-term memory takes information from sensory memory and sometimes connects that memory to something already in long-term memory. Short-term memory storage lasts about holds five to seven items for about 15–20 seconds

3) Long-Term Memory-the continuous storage of information. Unlike short-term memory, the storage capacity of LTM has no limits

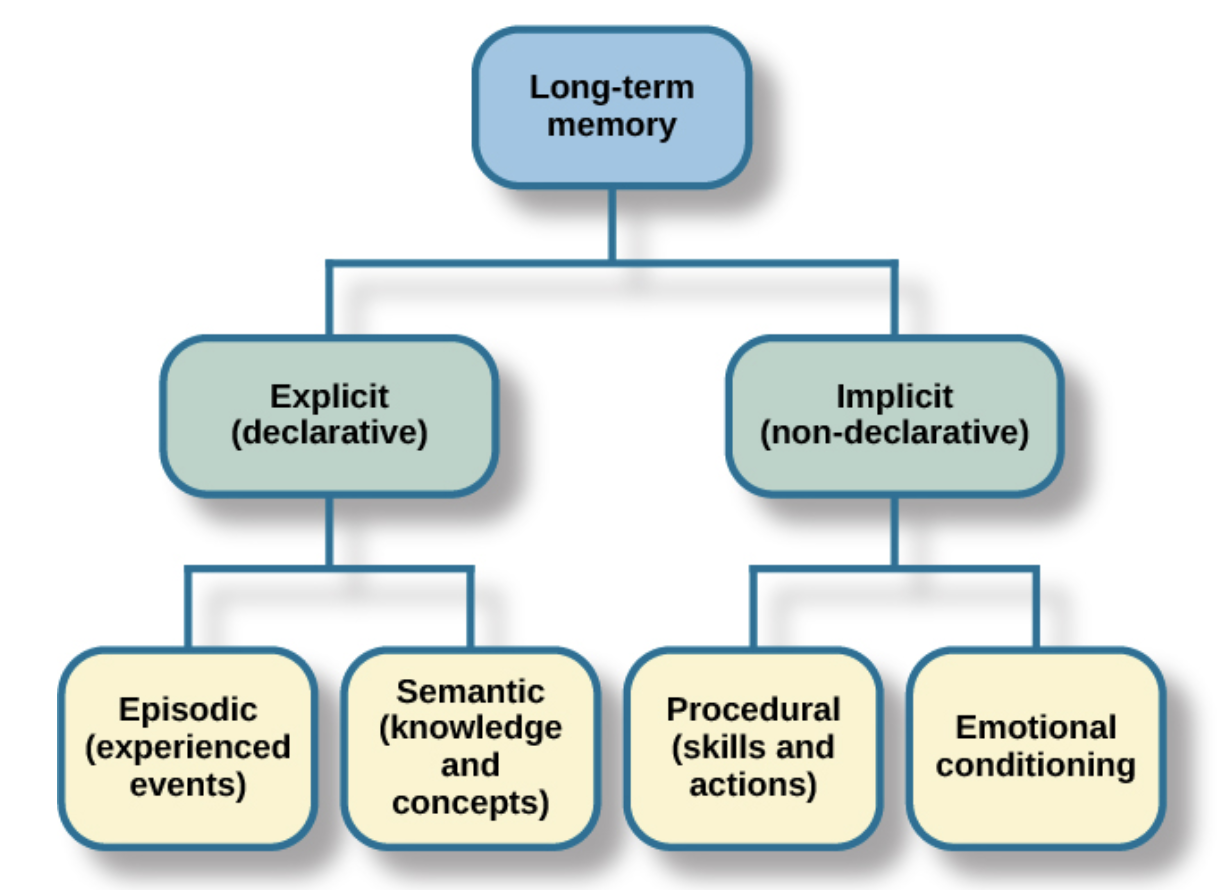

Two types: explicit and implicit

Explicit memories are those we consciously try to remember and recall. For example, if you are studying for your chemistry exam, the material you are learning will be part of your explicit memory.

Implicit memories are memories that are not part of our consciousness. They are memories formed from behaviors. Implicit memory is also called non-declarative memory.

Dissection of the Atkinson-Shiffrin model image

The curved arrow - represents the process of rehearsal, which occurs when we repeat something, like a phone number, to keep from forgetting it.

The blue arrow - indicates that some information in short-term memory can be transferred to long-term memory, a high-capacity system that can hold information for long periods of time (like your memory of what you did last weekend, or the capitals of states).

The green arrow- indicates that some of the information in long-term memory can be returned to short-term memory. The green arrow, which represents what hap pens when we remember something that was stored in long-term memory, is based on the idea that remembering something involves bringing it back into short-term memory.

What does Atkinson-Shiffrin model of memory explain?

The primacy effect, which is the tendency to remember the first items on a list more than the middle items

The recency effect, which is the tendency to remember the last items on a list more than the middle items

Why some information is easy to remember, like a phone number, while other information is easy to forget, like mathematical principles

To move STM into long-term memory is called _________________

memory consolidation.

Stroop Effect

describes why it is difficult for us to name a color when the word and the color of the word are different.

For example: upon seeing the word “yellow” in green print, you should say “green,” not “yellow.” This experiment is fun, but it’s not as easy as it seems.

Broadbent’s Model Could Not Explain...

Why participants can shadow meaningful messages that switch from

one ear to another

– Dear Aunt Jane (Gray & Wedderburn, 1960)

Treisman and Schmidt's 1982 study

– Participants report combination of features from different stimuli.

– Illusory conjunctions occur because features are “free floating.” – Ignore black numbers and focus on objects

– Participants can correctly pair shapes and colors

Purpose:

The study aimed to investigate how attention affects feature integration in visual perception. Specifically, Treisman and Schmidt explored whether attention is necessary to correctly bind visual features (like color, shape, and location) into coherent objects, introducing the concept of illusory conjunctions.

Method:

Participants were shown brief visual displays containing:

Multiple colored shapes (such as colored letters) flashed on a screen for about 200 milliseconds.

Distractors were included to divide participants' attention.

Afterward, participants were asked to report:

What colors and shapes they saw.

Whether specific combinations of features (like a red "X") appeared.

Results:

When attention was divided or insufficient, participants often reported illusory conjunctions — incorrect combinations of features (e.g., seeing a red "O" when the red color belonged to an "X").

When participants were given more time or asked to focus on specific locations, accuracy improved, and illusory conjunctions decreased.

Conclusion:

Attention is critical for correctly binding features into unified objects.

Without attention, features are processed independently and can be miscombined, supporting Treisman’s Feature Integration Theory (FIT) of attention.

In Treisman and Schmidt's 1982 study, ignoring the black numbers and focusing on objects was an important part of the experimental design because…

The purpose of this task was to direct participants' attention specifically to the visual features of the target objects (like shapes, colors, and orientations) while preventing distraction from irrelevant stimuli (such as the black numbers).

By asking participants to ignore the numbers, Treisman and Schmidt were able to examine how attention is allocated when people are processing a mixture of meaningful objects and irrelevant distractors. This helped them explore how attention impacts the binding of features (such as shape and color) to form a coherent perception of objects. In trials where participants were unable to focus on the objects due to distractions, illusory conjunctions (mistakes in feature integration) were more likely to occur. This confirmed the idea that attention is needed to correctly combine features and accurately identify objects in a complex visual scene.

Feature Integration Theory

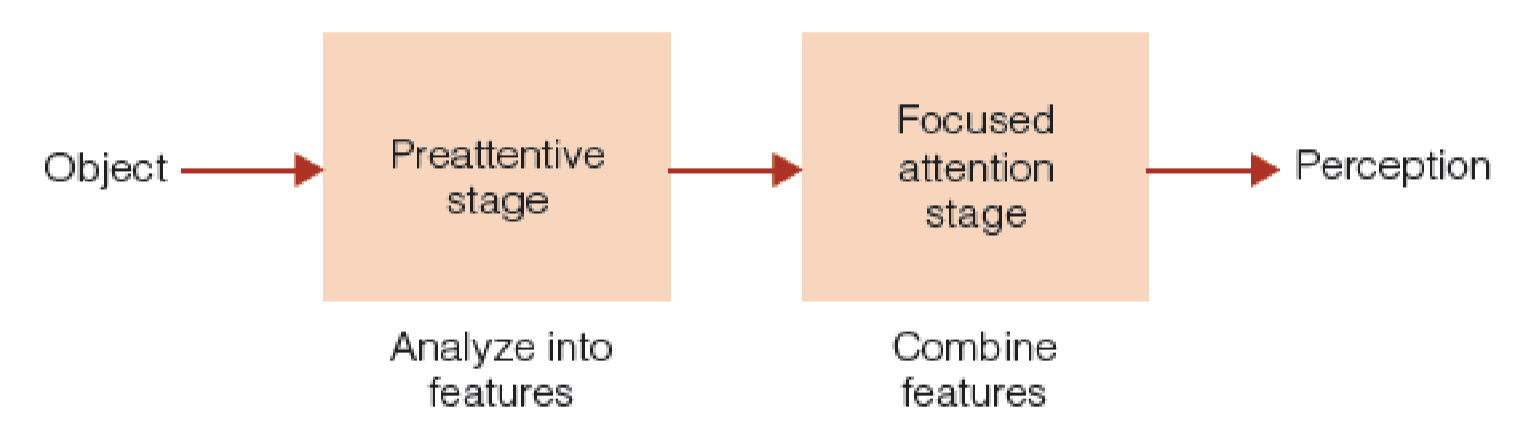

Feature Integration Theory was proposed by Anne Treisman in the early 1980s to explain how we perceive and process objects in our visual environment. According to FIT, our brain doesn't process complex objects in a single step. Instead, it breaks down the visual information into basic features (such as color, shape, size, orientation, and location) and processes these features in parallel (simultaneously and independently).

However, to form a coherent representation of an object, these features need to be integrated together, a process that requires attention.

What are the different stages for the Feature Integration Theory

Stage 1: Parallel Processing of Features

At the initial stage of perception, when we look at a visual scene, the brain quickly processes basic features of all the objects in the environment. This stage occurs in parallel, meaning that we process all features across the scene at once, rather than focusing on one object at a time.

For example:

Color (e.g., red, blue, green)

Shape (e.g., circle, square, triangle)

Orientation (e.g., tilted left, upright)

Size (e.g., large, small)

This parallel processing happens automatically and doesn't require focused attention. Our sensory system, particularly the visual cortex, can detect and identify these features of multiple objects in a scene without consciously focusing on them. This is why we can simultaneously perceive a variety of features (e.g., different colored shapes) in our visual field.

Stage 2: Attention and Feature Binding

The key point of Feature Integration Theory is that while we can detect and process these basic features in parallel, attending to an object is essential to integrate (or "bind") these features together into a coherent perception of the whole object.

For example, if you see a red circle and a blue square in your visual field, your brain processes the features of color and shape independently (the red and the circle, the blue and the square). However, to recognize them as distinct objects (a red circle and a blue square), attention is required to combine the shape and color of each object into a unified representation.

What is a result of the Feature Integration Theory

The results from the experiment showed that when attention was divided or not fully focused on the objects, participants were more likely to make illusory conjunctions

illusory conjunction

occurs when a person mistakenly combines features from different objects. For instance, a participant might report seeing a red "X" (combining the color of one object and the shape of another), or a green letter "T" (mixing up color and shape features from different stimuli).

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie (2007) overview

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie (2007) explored the relationship between attentional load (the amount of mental effort required by a task) and the detection of irrelevant distractors in a visual scene. The main question was whether high cognitive load in a task would affect the ability to detect distractors that were not the focus of attention.

Key Concepts

Cognitive Load: Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental resources required for a task. A high load means the task is demanding and consumes a lot of mental capacity, while a low load means the task is relatively easy and less taxing on cognitive resources.

Attentional Load: This is the portion of cognitive load related to the task’s demand for attention. When we are engaged in a difficult or complex task that requires focused attention, the attentional load is high. When the task is simple and doesn’t demand much concentration, the attentional load is low.

Irrelevant Distractors: These are stimuli in the visual scene that are not part of the task at hand but could interfere with the task if the brain is unable to filter them out effectively. For example, in a task that requires identifying a particular shape, other shapes in the visual field could be irrelevant distractors.

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie Experiment

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie conducted experiments using the visual search task paradigm, where participants were required to focus on identifying a target object (like a letter or shape) among a set of distractors. The key aspect of the experiment was manipulating the cognitive load of the primary task.

In some conditions, the attentional load was high, meaning the task was complex and required participants to focus their attention heavily on finding the target.

In other conditions, the attentional load was low, where the task was relatively simple and didn’t demand as much attention.

Key Findings

The main findings of the study were:

Higher Cognitive Load Leads to Reduced Detection of Irrelevant Distractors:

When the attentional load was high, participants were less likely to detect irrelevant distractors in the visual scene. This result suggests that when our attention is fully occupied with a demanding task, we become less sensitive to distractors that are outside the focus of attention. Essentially, the higher the cognitive load, the less we notice irrelevant items.

Low Cognitive Load Increases Sensitivity to Distractors:

When the task was easier (i.e., low cognitive load), participants were more likely to detect distractors. This suggests that when attention is not fully occupied with a demanding task, the visual system has more resources available to detect irrelevant stimuli, and people are more likely to notice things that are outside the scope of their focus.

Support for Load Theory of Attention:

These results support the Load Theory of Attention, which was proposed by Nilli Lavie (who co-authored the study). According to this theory, when attentional load is high, people are less likely to notice distractors because they are focusing their attention on the target and filtering out irrelevant information. Conversely, when the load is low, more cognitive resources are available to process non-target stimuli, leading to greater distractor detection.

What was the key aspect of the experiment_________________________________

manipulating the cognitive load

Attention and Working Memory:Object Perception

Object perception refers to the process by which we identify, recognize, and understand objects in our environment. It involves the brain's ability to integrate sensory information (visual, auditory, tactile, etc.) and use prior knowledge to make sense of the objects we encounter. Both attention and working memory play crucial roles in object perception, guiding how we focus on, process, and remember objects in our surroundings.

Here’s an exploration of how attention and working memory influence object perception:

1.Attention in Object Perception:

Selective Attention: When perceiving objects, our attention helps us focus on particular features or objects while filtering out distractions. This is important because the environment is often full of irrelevant stimuli, and we need to selectively attend to certain objects or attributes.

Example: In a crowded room, your attention might be drawn to the object of interest (like a cup) while ignoring background noise or movement. You can focus on its shape, size, and color.

Focused vs. Divided Attention:

Focused Attention: This is when we concentrate on one specific object or a set of objects. It allows for a deeper processing of the features of an object, such as its texture, color, or spatial relationships.

Divided Attention: In situations where multiple objects are present, attention is divided across them. For example, driving and observing both traffic lights and pedestrians at the same time requires divided attention. The brain has to constantly shift focus and manage competing information.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Attention in Object Perception:

Bottom-Up Attention: This is driven by the physical properties of the object, such as brightness, size, or movement. A flashing light or a moving object may automatically capture attention.

Top-Down Attention: Guided by our goals, knowledge, and expectations, top-down attention helps us focus on specific features of objects that are relevant to a task at hand. For instance, if you are looking for a red apple in a fruit basket, your prior knowledge of an apple's color and shape helps you focus on the right object.

Visual Attention and Object Recognition: When perceiving objects visually, attention is often directed toward the most salient features—such as edges, contours, and colors—helping to identify and categorize objects. Object recognition is facilitated by attention to critical features, like the shape of a car’s wheels or the texture of a fruit.

2.Working Memory in Object Perception:

Object Memory: Working memory plays a key role in maintaining and manipulating information about objects over short periods. When perceiving an object, our working memory holds a representation of the object’s characteristics (e.g., shape, color, size) to support further processing.

Example: If you see a red apple and then look away, your working memory allows you to retain a mental image of the apple’s characteristics, even if it’s no longer in your direct line of sight.

Updating Object Information: As we perceive objects and their features, working memory updates this information to reflect any changes in the environment or object itself. This helps us track objects across time and space.

Example: If you are following a moving car in traffic, your working memory constantly updates the car's location, speed, and direction, allowing you to adjust your behavior accordingly.

Manipulating Object Features: Working memory allows us to manipulate the features of objects. For example, if you are assembling furniture, your working memory will keep track of how different pieces fit together based on their shapes and orientations.

Interplay Between Attention and Working Memory: Attention and working memory interact in object perception. Attention helps focus on certain aspects of an object, while working memory maintains and updates the information for later use.

Example: If you’re examining a painting, attention directs your focus toward various elements, such as the artist's signature, the use of color, or the brush strokes. Working memory holds onto the details as you process and analyze the artwork.

3.Object Perception in Complex Environments:

Multiple Objects and Cognitive Load: In environments with multiple objects (like a busy street or a cluttered room), attention and working memory work together to manage the cognitive load. Attention helps prioritize the most relevant objects or features, while working memory holds onto important information and supports decision-making.

Object Tracking and Working Memory: Tracking multiple objects simultaneously (such as people in a crowd or items on a conveyor belt) requires working memory to hold representations of each object and attention to direct focus as needed.

Example: When playing a video game, players use attention to focus on key elements of the game (like the character they are controlling), while their working memory helps them track game objectives and other players’ positions.

4.Neural Mechanisms in Object Perception:

The Role of the Parietal Cortex: The parietal cortex is involved in the integration of sensory information and the allocation of attention to different objects in the environment. It plays a key role in directing attention to objects and maintaining spatial relationships between objects.

The Role of the Prefrontal Cortex: The prefrontal cortex is involved in working memory, guiding attention, and organizing object-related information. It helps maintain object representations and coordinate complex cognitive tasks like decision-making or problem-solving.

The Visual Cortex and Object Recognition: The occipital lobe and associated visual cortex regions are responsible for processing visual stimuli. These areas contribute to object recognition, identifying features such as shape, color, and texture. The temporal lobe also contributes to storing and retrieving object-related information from memory.

Attention and Working Memory: Top-Down Effects

1. Attention:

Definition: Attention refers to the cognitive process of selectively focusing on specific information or stimuli while ignoring others. It enables us to prioritize certain tasks or inputs, especially in environments with multiple distractions.

Top-Down Attention: This form of attention is guided by our internal goals, intentions, or expectations. It contrasts with bottom-up attention, which is driven by external stimuli (like a loud noise or bright light). Top-down attention is an active, goal-directed process that helps us focus on relevant information based on what we expect or want to focus on.

Example: If you're looking for a friend in a crowded room, your attention is directed towards people who match your friend’s appearance or behavior, based on your knowledge of how they look or act. This is a top-down process.

Role in Working Memory: Top-down attention helps filter and select information for storage in working memory. For example, when you are trying to remember a phone number, top-down attention helps you focus on the digits and ignore irrelevant distractions.

2. Working Memory:

Definition: Working memory refers to the system responsible for temporarily storing and manipulating information that is actively used in cognitive tasks, such as problem-solving, reasoning, and decision-making.

Top-Down Effects on Working Memory: In the context of working memory, top-down effects refer to how prior knowledge, expectations, and goals influence what information is maintained, retrieved, and processed.

Example: When solving a math problem, your existing knowledge of arithmetic rules or formulas will help you focus on relevant parts of the problem and discard irrelevant information, enhancing your ability to solve the task efficiently.

Active Maintenance of Information: Top-down control can guide which pieces of information should be maintained in working memory. For example, if you’re studying for an exam, your motivation and specific study goals will guide your attention and memory toward the most relevant material.

Updating and Manipulating Information: When we need to update or manipulate information in working memory (such as switching between tasks or adjusting a plan), top-down processes help determine which items are most important and how to adjust our cognitive resources.

3. Interactions Between Attention and Working Memory:

Focused Attention and Memory Encoding: Focused attention ensures that relevant information is encoded efficiently into working memory. Top-down attention, influenced by our goals, determines what we pay attention to and what we store.

Inhibition of Irrelevant Information: Top-down processes help in suppressing irrelevant or distracting stimuli that may interfere with the retention or manipulation of information in working memory. This ability to inhibit distractions is crucial for cognitive tasks that require focus and memory.

Cognitive Load: Top-down processes in both attention and working memory also manage cognitive load. When we have to perform complex tasks, top-down control can help allocate resources effectively, reducing the strain on memory systems.

4. Neuroscientific Insights:

The prefrontal cortex is a key brain area involved in top-down control. It regulates attention, working memory, and other executive functions by exerting control over other regions of the brain, such as the parietal cortex (which is involved in spatial attention) and the temporal cortex (which helps in processing stimuli).

Top-down effects rely on neural networks that involve the prefrontal cortex sending signals to sensory and memory areas, helping guide the focus of attention and the selection of relevant information for working memory.

Attention and Working Memory; Long-Term Memory

Attention and Long-Term Memory

Focused Attention: Key for encoding information into long-term memory.

Example: Studying with focus improves memory retention.

Selective Attention: Filters out irrelevant info, aiding memory encoding.

Example: Focusing on lecture highlights important details.

Top-Down Attention: Guided by goals, enhances encoding.

Example: Looking for key points during an exam prep.

Working Memory and Long-Term Memory

Encoding: Working memory helps process and organize info for long-term storage.

Example: Chunking information (e.g., phone numbers) aids encoding.

Rehearsal: Repeating info strengthens memory.

Example: Repeating a name helps store it in long-term memory.

Deep Processing: Organizing and making connections aids memory retention.

Example: Relating new concepts to prior knowledge.

Retrieving from Long-Term Memory

Attention During Retrieval: Focused attention helps access memories.

Example: Paying attention to a question aids correct recall.

Working Memory in Retrieval: Combines long-term info with current needs.

Example: Applying a formula to solve a problem requires working memory.

Consolidation

Role of Attention and Working Memory: Active engagement enhances consolidation of memories.

Example: Focusing on and rehearsing information strengthens memory.

Sleep: Crucial for memory consolidation, especially post-learning.

Neural Mechanisms

Prefrontal Cortex: Manages attention, working memory, and memory retrieval.

Hippocampus: Vital for encoding and consolidation into long-term memory.

Neocortex: Long-term storage and retrieval of memories.

Practical Implications

Learning Strategies: Use focused attention, rehearsal, and active recall for better retention.

Memory Disorders: Issues with attention or working memory can impair long-term memory encoding.

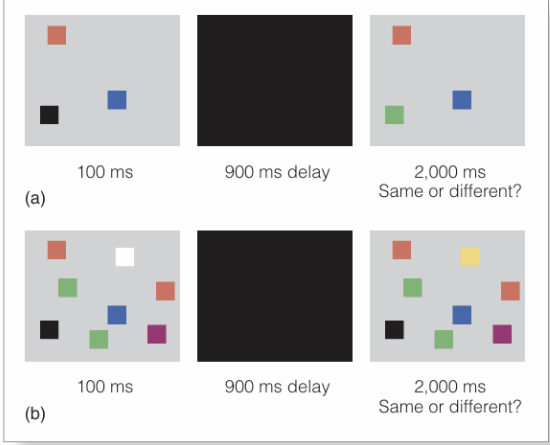

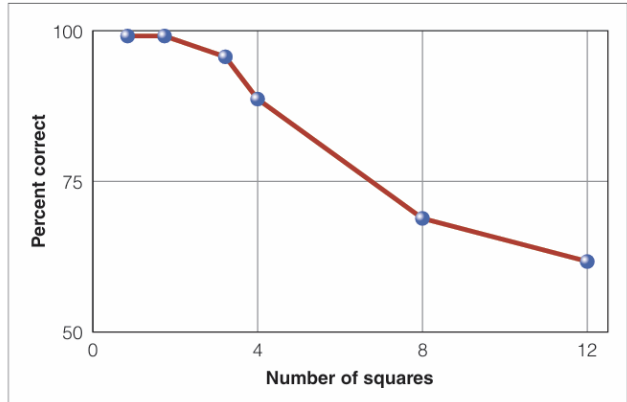

Luck and Vogel (1997) - Visual Working Memory

Their study, titled "The capacity of visual working memory for objects and features", is widely regarded in cognitive psychology and memory research. They aimed to understand the capacity limits of visual working memory.

Key Points:

They conducted experiments to investigate how much visual information people could hold in memory at once.

They found that the capacity for visual working memory is typically limited to around three to four objects (or "items") at a time.

Interestingly, features of objects (such as color, shape, or orientation) could be remembered separately, but the total amount of information one could remember at once was constrained.

Impact:

This research was significant because it showed that, contrary to earlier beliefs that memory could be limitless or extremely high capacity, our visual working memory has a finite limit, typically around three or four objects. This has been foundational in understanding cognitive processing, especially in how we handle complex visual environments and how our brain processes and stores this information.

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie (2007)

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie (2007) conducted an influential study in the field of cognitive psychology, specifically focused on visual attention and inattentional blindness.

Cartwright-Finch and Lavie (2007)- Study on Inattentional Blindness

Key Findings:

Load Theory: They found that the level of cognitive load (how much information a person is processing at once) plays a crucial role in whether inattentional blindness occurs. Specifically:

When people are under high cognitive load (e.g., focusing on a demanding task), they are more likely to fail to notice irrelevant or unexpected objects in their visual field.

Under low cognitive load, they are more likely to notice unexpected objects, even if they are not actively focused on them.

Attentional Resources: The study suggested that the amount of attentional resources available to an individual plays a significant role in whether they can detect unexpected stimuli in their environment. When cognitive load is high, fewer resources are available for processing irrelevant information, leading to inattentional blindness.

Impact:

The research has had a profound impact on the understanding of how attention works. It showed that:

Inattentional blindness is not just about failing to pay attention to something; it's also about the mental resourcesbeing used by a person to process information.

The findings extended the Load Theory of Attention, which suggests that tasks requiring more cognitive resources leave fewer resources available for processing other things, making individuals more likely to miss unexpected stimuli.

Egly et al. (1994)

Egly et al. (1994) conducted an important study on visual attention and how attention is allocated in space. The paper, titled "Shifting visual attention between objects and locations: Evidence from normal and parietal lesion subjects", focused on the spatial allocation of attention and how attention shifts when individuals are asked to focus on different objects or locations.

Key Focus of the Study:

Egly and colleagues were interested in how attention is directed not only to specific locations but also to objects. Their study examined the nature of object-based attention.

Key Findings:

Object-based Attention:

They found that attention is not always allocated purely by spatial location (i.e., where something is in the visual field). Instead, attention can also be directed toward objects themselves, independent of their spatial location.

This was demonstrated through experiments in which participants were asked to focus on certain locations or objects, and they showed faster responses when the cued area was part of an object they were attending to, even if the object extended across multiple locations.

Spatial and Object-Based Attention:

Their results revealed that shifting attention across objects (rather than locations) could be more efficient. For example, when participants shifted attention to one part of an object, their attention was also implicitly spread to other parts of the object, suggesting a kind of object-based processing.

Important Implication for Theories of Attention:

This study provided important evidence against theories that focused only on spatial attention, arguing instead for a more integrated view where attention is directed to both spatial locations and object-based representations. The idea that attention can be object-based had significant implications for later research on attention and perception.

Egly and colleagues were interested in how attention is directed not only to specific _________ but also __________

locations-objects

Forster and Lavie (2008)

Forster and Lavie (2008) conducted a significant study on cognitive load and its effects on inattentional blindness, expanding on their previous work with Lavie and others. The study, titled "Environmental Load and Inattentional Blindness: The Role of Perceptual Load" (published in Psychological Science), explores the relationship between the amount of perceptual load (how demanding a task is) and the likelihood of missing unexpected objects in the visual field.

Key Focus of the Study:

Forster and Lavie focused on the idea of perceptual load, which refers to the complexity or difficulty of the primary task a person is engaged in. Their research aimed to determine how perceptual load affects inattentional blindness, the phenomenon in which people fail to notice unexpected objects in their environment because their attention is focused elsewhere.

Key Findings:

The Role of Perceptual Load:

High perceptual load (i.e., when the primary task is complex or requires a lot of attention) increases the likelihood of inattentional blindness. When individuals are busy with a demanding task, they have fewer cognitive resources to notice unexpected stimuli in the environment.

Low perceptual load, on the other hand, leaves more cognitive resources available for processing non-task-related stimuli, making people more likely to notice unexpected objects.

Load Theory of Attention:

The study supported the Load Theory of Attention, which suggests that when perceptual load is high, fewer resources are available for processing irrelevant or distractor stimuli, leading to inattentional blindness. When the load is low, attention is less focused, and people are more likely to notice things outside of their primary task.

Object-Based Attention and Inattentional Blindness:

The researchers also extended the work on object-based attention, which suggests that people are more likely to miss unexpected stimuli that are not part of the task they are focusing on, especially when their attention is already being taxed by a complex task.

Impact of the Study:

This study emphasized how attentional resources are allocated and how cognitive load can influence our perception of the world.

It had a major impact on the study of attentional control and visual perception, showing that individuals' attentional capacity is not unlimited, and the level of cognitive load can significantly influence what we do and do not notice in our environment.

Gray and Wedderburn (1960)

Gray and Wedderburn (1960) conducted a classic experiment in the field of auditory attention and dichotic listening, which helped advance the understanding of how we process and attend to information coming from multiple sources

Gray and Wedderburn (1960) ; Study Overview

The paper, titled "Attending to the other side: The role of selection in the perception of speech" (published in The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology), explored how people can attend to one stream of auditory information while ignoring another. Specifically, they were interested in how individuals process information presented simultaneously in both ears, a task known as dichotic listening.

Key Findings:

Dichotic Listening and Auditory Attention:

The researchers used a dichotic listening task, where participants were presented with different messages in each ear (one in the left ear and one in the right ear) and asked to pay attention to one ear while ignoring the other.

Speech Perception and Auditory Attention:

Gray and Wedderburn found that when participants were presented with word pairs that were delivered across both ears (one word in each ear), people didn’t just process the words from one ear. Instead, they often combined the words from both ears to make meaningful phrases (e.g., "the cat" from one ear and "is on" from the other). This phenomenon was called "split attention" or "integrated attention".

Selective Attention is More Flexible:

The study demonstrated that auditory attention is not as rigid as previously thought. Rather than focusing exclusively on one ear or one message, participants were able to integrate information from both ears, showing a more flexible and dynamic approach to how we attend to and process speech in complex auditory environments.

Impact:

Challenge to Early Theories of Auditory Attention: Before this study, the dominant view was that people could only attend to one auditory stream at a time, and any information presented in the unattended ear was essentially ignored. Gray and Wedderburn's work challenged this view by showing that speech processing could involve the integration of information from multiple sources.

Contributions to Attention Theories: The study highlighted that auditory attention is not strictly about filtering out information but can involve some degree of integration and processing of competing stimuli, especially in the case of speech.

Posner et al. (1978)

Purpose:

Posner et al. sought to investigate how attention influences the detection of visual signals. They were particularly interested in understanding whether attentional shifts could speed up reaction times even without eye movements.

Method:

Participants were asked to sit in front of a computer screen and focus on a central fixation point.

A visual cue (an arrow) was presented on either the left or right side, signaling where the target was likely to appear.

The cues could be:

Valid cues: Correctly indicated the target location.

Invalid cues: Incorrectly indicated the target location.

Neutral cues: Gave no information about target location.

Participants were instructed to press a button as soon as they detected the target.

Results:

Reaction Times:

Faster reaction times were observed for validly cued trials compared to neutral or invalid trials.

Invalid cues led to slower reaction times due to the need for attentional reorientation.

Conclusion:

Attention can be directed independently of eye movements.

Posner distinguished between two types of attention:

Endogenous attention: Voluntary, goal-driven (responding to the arrow cues).

Exogenous attention: Reflexive, automatic (responding to sudden target appearances).

Raveh and Lavie (2015)

Purpose:

Raveh and Lavie aimed to explore the relationship between sensory load and selective attention, particularly how auditory load (complexity or demands of auditory tasks) influences visual attention and susceptibility to distractions.

Method:

Participants were tasked with detecting visual targets on a screen while listening to auditory sequences. The auditory task varied in difficulty (sensory load):

Low Load Condition: Simple, repetitive auditory patterns (e.g., listening for a single tone).

High Load Condition: Complex auditory patterns requiring more cognitive processing (e.g., identifying changes in pitch).

Simultaneously, participants were exposed to visual distractors irrelevant to their task.

Results:

Low Auditory Load: Participants were more susceptible to visual distractions, showing slower reaction times and reduced accuracy when visual distractors appeared.

High Auditory Load: Visual distractions had less of an impact, as participants were more focused on the demanding auditory task.

Conclusion:

When sensory load in one modality (auditory) is high, selective attention improves in other modalities (visual), leading to better filtering of irrelevant stimuli.

The findings supported Lavie’s Load Theory of Attention, which posits that attentional capacity is limited and task load affects the ability to ignore distractions.

Sperling (1960)

Purpose:

Sperling aimed to investigate the capacity and duration of sensory memory, particularly iconic memory (visual sensory memory). The study sought to determine how much visual information humans can retain after a brief exposure and whether partial report techniques could reveal more information than whole report methods.

Method:

Participants were shown a grid of 12 letters (arranged in 3 rows of 4) for 50 milliseconds. There were two conditions:

Whole Report Condition: Participants were asked to recall as many letters as possible from the entire grid.

Partial Report Condition: After the letter display, a high, medium, or low-pitched tone was played, indicating which row the participants should recall.

Results:

Whole Report: Participants could recall only about 4-5 letters on average, even though they reported seeing more.

Partial Report: Participants could accurately recall about 3 letters from any cued row, suggesting they had briefly retained information for the entire display.

Conclusion: Iconic memory has a large capacity but very short duration (less than one second).

A Few Details • Luck & Vogel and Sperling

Luck & Vogel (1997) — Short-Term Memory Storage Capacity:

Estimated that short-term visual working memory can store about 3-4 objects regardless of the complexity of the visual features.Sperling (1960) — Percentage of Letters Seen:

Sperling estimated that participants initially saw and stored about 75-80% of the letters immediately after the display, although they could only report about 35-40% using whole-report methods due to rapid fading of iconic memory.

Sergent (2018) in Lecture

Purpose:

Claire Sergent aimed to explore the relationship between conscious processing and working memory, focusing on the ability to manipulate information "offline" — after sensory input is no longer present. The study examined how consciousness allows for complex cognitive functions such as reasoning, imagination, and planning.

Method:

Participants were assigned tasks that required them to maintain and manipulate information in working memory without relying on immediate sensory input.

Neuroimaging techniques (e.g., fMRI) were used to monitor brain activity during these tasks.

Results:

The study found activation in specific brain networks during tasks involving the manipulation of information in the absence of external sensory input.

This supports the idea that conscious awareness facilitates "offline" cognitive processing.

Conclusion:

Conscious processing enables flexible and adaptive behavior by allowing individuals to work with non-perceptible information.

Sergent proposed that this ability may have offered evolutionary advantages, compensating for the slower nature of conscious processing compared to automatic unconscious responses.