7. The Time Inconsistency Problem and the Barro-Gordon Model

1/20

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

21 Terms

Earliest Central Banks

The earliest central bank was founded when the Riksdag (Swedish Government) founded the Riksen Standers Bank, later renamed to Sveriges Riksbank in 1668

The Bank of England emerged in 1694

Bank of England’s initial purpose

Purchase government debt (lend money to fund wars in France)

Finances were in such a bad state initially that the rate on bonds was 8%

Eventually it developed into the bank for other banks

Recap of development

Commodity money has problems, whilst paper money solves coincidence of want

Various banks develop simultaneously, and the government needs to borrow money

A central bank is formed to lend to the government; because the Central Bank has links with the state and is trusted, people prefer CB notes, meaning other notes eventually decline

Central Banks control money and have a link to fiscal policy

Key points about central banks

Solved the problem of banks having different notes (frequently as receipts for gold or silver)

Many CB’s are introduced to raise fiscal revenue (money for government spending)

CB becomes a lender of last result, can be used for bailouts to prevent runs

The only institution allowed to print money

The Kydland-Prescott Model

If a policymaker can act with discretion (without consequences) then there is an incentive for them to renege on promises

Their actions would be time-inconsistent; their actions under discretion misalign with their promises

The Barro-Gordon Model

Developed a model of policy-making under rational expectations, where the policymaker is emphasised as not the government

Allows for a comparison of outcomes under discretion and under commitment

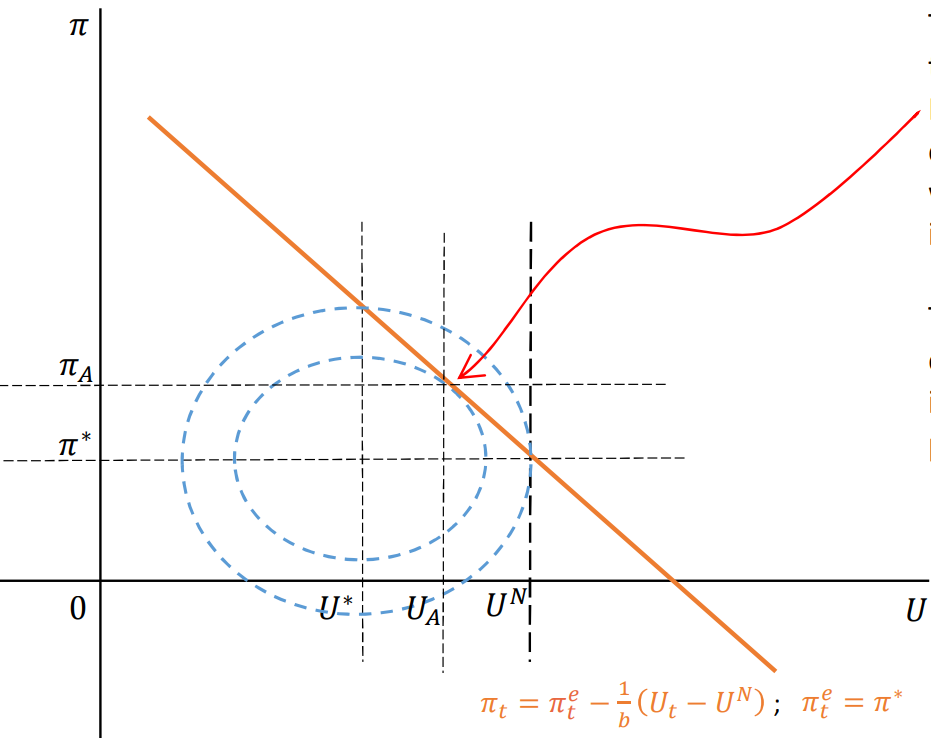

Loss function: Lt = (Ut - U*)2 + a (⊓t - ⊓*)2, Inverted Phillips Curve: Ut = UN - b (⊓t - ⊓te)

Policymaker choose ⊓t, U* < UN such that the government desires unemployment below the natural rate

⊓t is effectively the policy makers tool

The Barro-Gordon Loss Function

Lt = (Ut - U*)2 + a (⊓t - ⊓*)2

U* is unemployment target, ⊓* is the inflation weight, a is the weight on inflation deviations from target relative to unemployment deviations from target

Because the function is quadratic, being above or below target are equally bad

Loss is minimised at (U*, ⊓*), where Lt = 0

The Barro-Gordon Phillips Curve

Ut = UN - b (⊓t - ⊓te), normal Phillips Curve is ⊓t = ⊓te - 1/b (Ut - UN)

Ut is unemployment at time t, UN is the natural rate of unemployment

If actual inflation exceeds expectations, unemployment will be lower than the natural rate

If real wages are influenced by inflation, then inflation above target means real wages fall because the nominal amount is too low

-b is the sensitivity of unemployment to real wage changes

-1/b is the sensitivity of inflation to the unemployment gap

Downwards sloping linear function, with unemployment on x and inflation on y

Characteristics which can affect inflation expectations

Naivety: Public wage-setters believe inflation will be what the government tells them

Anchored: People might be insensitive to data

Rational: Forward looking model of the world which is correct

Naive solution

Public believe inflation will be what the government says, so ⊓e = ⊓t = ⊓*

The aim is to minimise the loss function with respect to the constraint of the inverted Phillips curve given ⊓te = ⊓*

We substitute the Phillips Curve into the loss curve and minimise with respect to ⊓t, then setting = 0 and rearranging to get an answer in terms of ⊓t; this answer will be > ⊓*

By substituting the expression for ⊓t into the loss function, one can attain a value of Ut

The government has an incentive to set an inflation rate greater than ⊓te so that they can get an unemployment rate below the natural level

Loss in the naive solution

L > 0 and L = 0 is unachievable if UN > U*

There is incentive to renege on the promise once expectations have been set

The government could achieve ⊓*, but only by setting Ut > U*, where Ut = UN meaning that (UN, ⊓*) is not the welfare-maximising choice

They could achieve U*, but only by allowing ⊓t = ⊓b > ⊓*, thus (U*, ⊓b) is not the welfare-maximising choice either

The solution to the minimising expenditure problem represents the best outcome the government can achieve with a foolish and naive electorate (UA, ⊓A)

This is time-inconsistent because the actual inflation rate is not the same as the one the government promised; this can only be maintained if the public can be convinced that ⊓te = ⊓*

Rational Expectations Outline

⊓te = Et-1⊓t

Et-1 just means that expectations are formed using available information at time t-1

The public (wage-setters, private sector) assume their expectations before ⊓t is realised and before the policy choice ⊓t is made

They are also assumed to have a correct model of the economy

Rational Expectations derivation

Minimise the Loss function subject to the inverted Phillips curve given ⊓te = ⊓t

Substitute the Phillips Curve into the Loss function and differentiate wrt ⊓t, then set = 0

Rearrange to get an expression in terms of ⊓t which is greater than ⊓*

Rational Expectations Solution

Graphically, the solution is understood as a ‘time-consistent equilibrium’, where expectations = the inflation level

The time-consistent solution has higher inflation and unemployment than both the optimum and naive equilibrium points

This is because the rational wage-setters aren’t fooled by the policymaker; they understand the incentive to raise inflation surprisingly, and so they adjust their expectations accordingly

An equilibrium is at (⊓c, UN)

Loss in the rational expectations equilibrium

Because inflation is above optimum, loss will be strictly positive

Despite inflation being above target, there is no compensated gain in lower unemployment because inflation expectations are equal to the actual inflation level

If ⊓t = ⊓e, this naturally implies that unemployment is at the natural rate

There is an inflation bias in the time-consistent equilibrium, which is the difference between actual inflation and optimum inflation (⊓e - ⊓* = b/a (UN - U*))

Anchored Expectations outline

Can be treated in a similar way to naive expectations, but they do move eventually, if people start to realise they’re being fooled

This consists in a movement to more rational expectations

Beliefs are anchored when agents hold inflation expectations in line with the CB’s target rate

Imperfectly anchored expectations

If beliefs are perfectly anchored, they are insensitive to any incoming data, like the naive case

Partially anchored expectations are slightly responsive to changes in information which influences expectations, leading to slight shifts in the inverted Phillips Curve

What is stabilisation policy?

Monetary/fiscal policy aimed to counteract shocks which affect the real economy

The role of anchored expectations in reducing stabilisation policy costs

If expectations aren’t anchored, a shock will shift the Phillips curve by the ‘amount’ of the shock

If expectations are anchored during the shock, unemployment doesn’t need to rise to bring it back down; it will rise and fall itself

If partially anchored, unemployment levels would rise, but less than if they were completely unanchored

Disinflation (stabilisation) policy is less costly when expectations are anchored

Assumptions about policymakers

In the Barro-Gordon model, they assume the policymaker is trying to reach a level of inflation below the natural rate; governments might want to do this to make it look like the economy is doing well before elections

In stabilisation policy, generally policymakers are conceived of as trying to reach the natural rate of unemployment and optimal inflation (Barro-Gordon is (Ut > UN, ⊓a) compared to stabilisation policy’s target of (UN, ⊓*)

What is the time-inconsistency problem?

It concerns the sub-optimal outcomes which can occur if there is incentive at a later point in time to renege on promises made at an earlier point in time

The example is of a policymaker who sets an inflation target and then surprises people with higher inflation for their own ends