BI441 - Aflatoxin Essay

1/8

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

9 Terms

Structures

-

-

Aflatoxin intro

Aflatoxins are a group of highly toxic and carcinogenic secondary metabolites produced mainly by the fungi Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus.

They belong to the polyketide class of fungal metabolites and are synthesised by polyketide synthase enzymes using acetyl‑CoA and malonyl‑CoA as their primary building blocks.

Chemically, aflatoxins are small, non‑peptidic, highly oxygenated aromatic compounds that are stable in the environment and capable of persisting in food and feed.

Their stability and common presence in crops like peanuts, maize, and tree nuts make them a serious global health risk, especially in warm regions with poor food storage.

Aflatoxin types

Aflatoxins are a group of toxic secondary metabolites primarily produced by the filamentous molds Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus.

Chemically, aflatoxins are classified as polyketides, meaning they are synthesized by multi-domain enzymes called polyketide synthases (PKSs) that condense short-chain carboxylic acids like acetate and malonate.

These toxins were famously discovered in the 1960s following "Turkey X disease," an outbreak that killed thousands of birds who had consumed contaminated peanut feed.

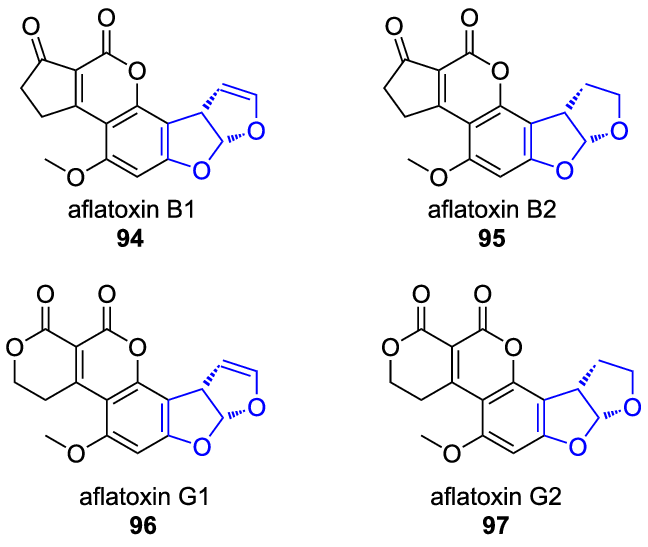

There are four primary types of aflatoxins found in nature: B1, B2, G1, and G2.

These designations are based on whether the molecules exhibit blue (B) or green (G) fluorescence under ultraviolet light and their mobility during thin-layer chromatography.

Among these, Aflatoxin B1 is recognized as one of the most potent naturally occurring carcinogens ever identified.

Aflatoxin toxicity

Aflatoxins become toxic after they are metabolized in the liver.

Cytochrome P-450 enzymes convert them into a highly reactive compound called aflatoxin-2,3-epoxide.

This epoxide is highly mutagenic.

It binds to guanine in DNA, forming bulky DNA adducts that cause permanent genetic mutations.

These mutations can lead to acute aflatoxicosis, with severe liver damage, jaundice, bleeding, and possible fatal liver failure.

These DNA lesions are especially dangerous because they cause specific mutations in tumour suppressor genes, especially p53, strongly linking long-term aflatoxin exposure to liver cancer.

This risk is even higher in people who also have hepatitis B infection.

In addition to their toxicity, aflatoxins inhibit protein synthesis, disrupt normal cellular metabolism and suppress immune function, compounding liver injury.

Aflatoxin B1 is the most potent and best studied.

Other aflatoxins work in similar ways but are less harmful: G1 and G2 form epoxide intermediates less efficiently, which makes them less carcinogenic, and B2 is less reactive but can still cause toxicity with long-term exposure.

Overall, all aflatoxins are significant hazards to human and animal health.

Amanitin intro

α‑Amanitin is one of the most significant mycotoxins known, and it represents a classic example of how fungal secondary metabolites can disrupt essential cellular processes.

It is produced by the deadly mushroom Amanita phalloides, commonly known as the death cap, and is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide.

Understanding the molecular nature of α‑amanitin and its mechanism of action provides insight into how a single fungal metabolite can cause rapid failure of vital organs.

Amanitin structure

Chemically, α‑amanitin is a large ribosomally synthesised cyclic peptide.

It belongs to a small group of fungal toxins known as ribosomal peptide secondary metabolites, which are produced as precursor peptides and then extensively modified.

α‑Amanitin is a cyclic octapeptide, meaning it contains eight amino acids arranged in a closed ring.

Several of these amino acids are unusual or modified, and the peptide also contains D‑amino acid residues, which are rare in biological systems.

These structural features give α‑amanitin a rigid, highly stable conformation.

The molecule’s internal loop structure is essential for its biological activity, allowing it to bind with exceptional specificity to its cellular target.

Unlike many fungal toxins, α‑amanitin is not a polyketide or a non‑ribosomal peptide.

Its biosynthetic origin is entirely distinct, reflecting the diversity of fungal secondary metabolism.

Amanitin toxicity

α-Amanitin is deadly because it binds tightly to RNA polymerase II, stopping mRNA production and preventing cells from making essential proteins.

When transcription stops, the cell quickly fails.

Without mRNA, enzymes are no longer made, metabolism shuts down, and energy runs out. Structural proteins cannot be replaced, so cell membranes weaken and rupture.

Regulatory proteins are also missing, disrupting cell division and stress responses.

Together, these failures lead to cell death by necrosis or apoptosis.

Cells that are very metabolically active are affected first.

The liver is the main target because hepatocytes are heavily involved in detoxification and protein production.

The kidneys are affected next because they filter the toxin and depend on constant protein synthesis.

Amanitin poisoning usually begins hours after ingestion, followed by severe stomach pain, liver and kidney failure, multiple organ failure, and often death within two to seven days.

Compare

Comparing aflatoxins and alpha-amanitin reveals both similarities and differences in their chemical nature and mechanisms of toxicity.

Chemically, aflatoxins are small, polyketide-derived molecules, whereas alpha-amanitin is a larger, cyclic peptide synthesized ribosomally.

Both are secondary metabolites produced by fungi and are highly stable in nature, ensuring their persistence in the environment and in contaminated food.

Mechanistically, aflatoxins exert toxicity through metabolic activation to reactive epoxides that damage DNA and proteins and induce oxidative stress, leading to mutagenesis and carcinogenesis.

In contrast, alpha-amanitin operates by a highly specific mechanism, binding to RNA polymerase II and halting mRNA transcription, causing a rapid cessation of protein synthesis and cellular apoptosis.

While aflatoxins primarily cause chronic liver damage and cancer over prolonged exposure, alpha-amanitin induces acute, life-threatening organ failure shortly after ingestion.

Both mycotoxins underscore the diverse strategies fungi employ to produce biologically active molecules, but they differ fundamentally in their chemical composition, cellular targets, and the temporal progression of their toxic effects.