17. Intracellular Messengers- Part 2: The Role of Calcium in Muscle Contraction

1/16

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

17 Terms

Focus of this lecture?

Linking muscle cell action potential → actual contraction

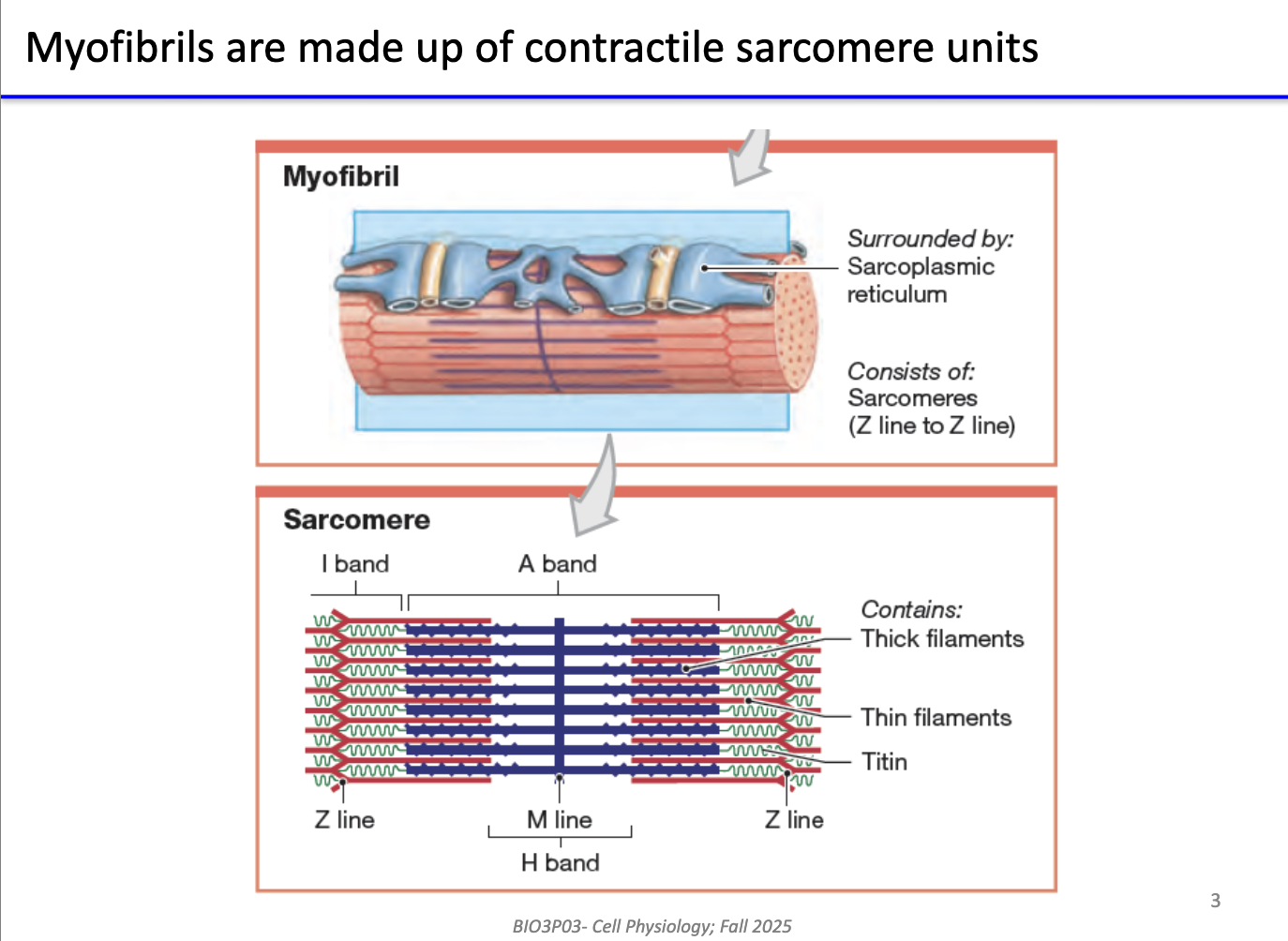

What are myofibrils made of, and how is contraction organized in skeletal muscle?

Myofibrils = bundles of sarcomeres (contractile units).

Sarcomere structure:

Thick filaments: myosin (heavy chains)

Thin filaments: actin

Mechanism of contraction:

Myosin heads “walk” along actin → pull Z-lines closer → sarcomere shortens.

Multiple sarcomeres in parallel → large-scale muscle contraction.

Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR):

Specialized ER surrounding sarcomeres.

Stores and regulates Ca²⁺ for contraction.

Mechanisms of Ca²⁺ release apply to skeletal, cardiac, smooth muscle, and even non-muscle cells with ER.

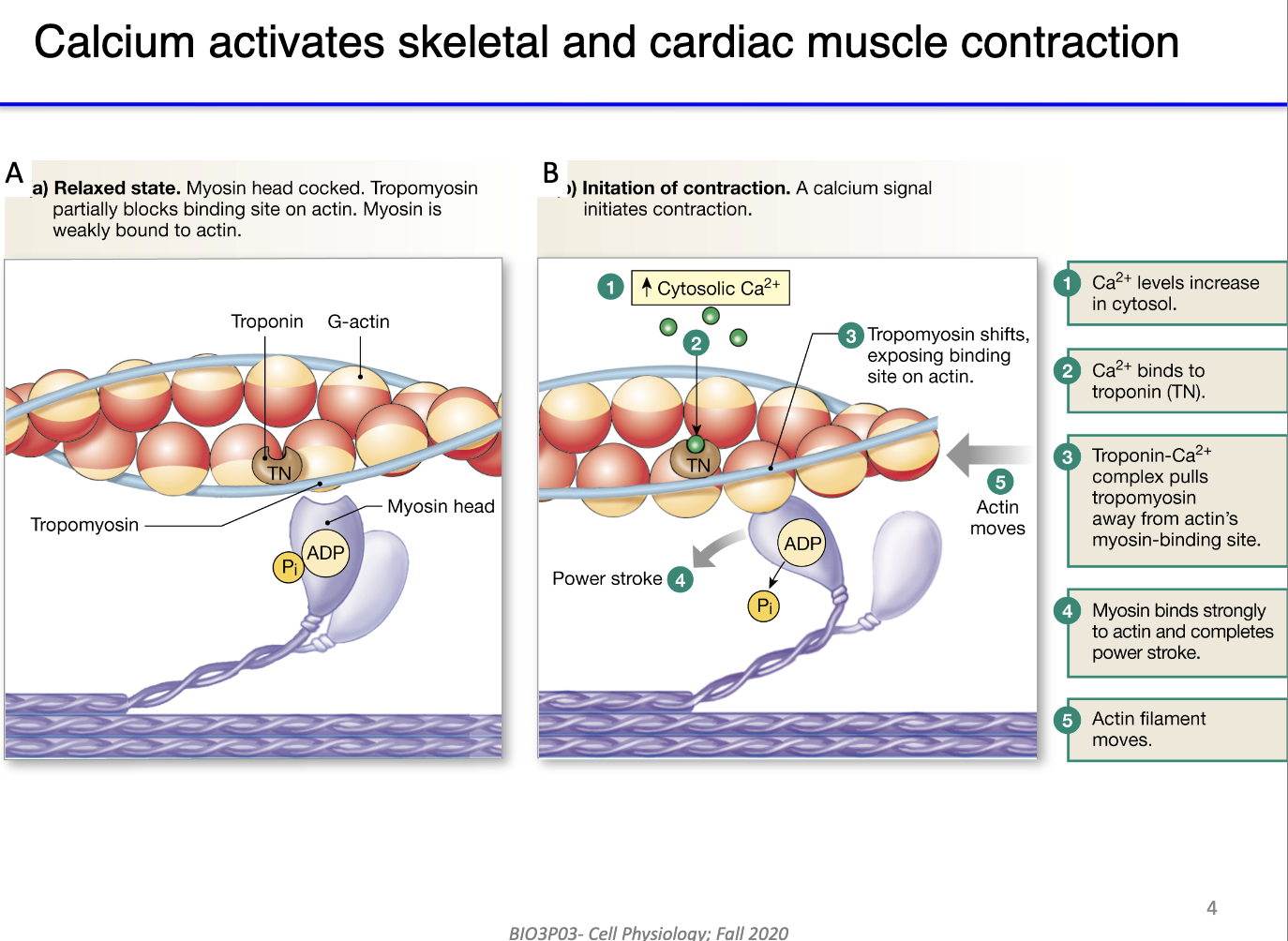

How does calcium regulate actin-myosin interaction in skeletal muscle contraction?

Resting state:

Myosin heads bound to ADP + Pi; tropomyosin blocks actin binding sites.

Role of Ca²⁺:

Calcium released into cytosol binds troponin (Ca²⁺-binding protein) in actin filament.

Troponin undergoes conformational change → moves tropomyosin off actin binding sites.

Result:

Myosin heads bind actin → ATP hydrolysis → power stroke → sarcomere shortens.

Link: This mechanism connects cytosolic calcium increase to functional muscle contraction.

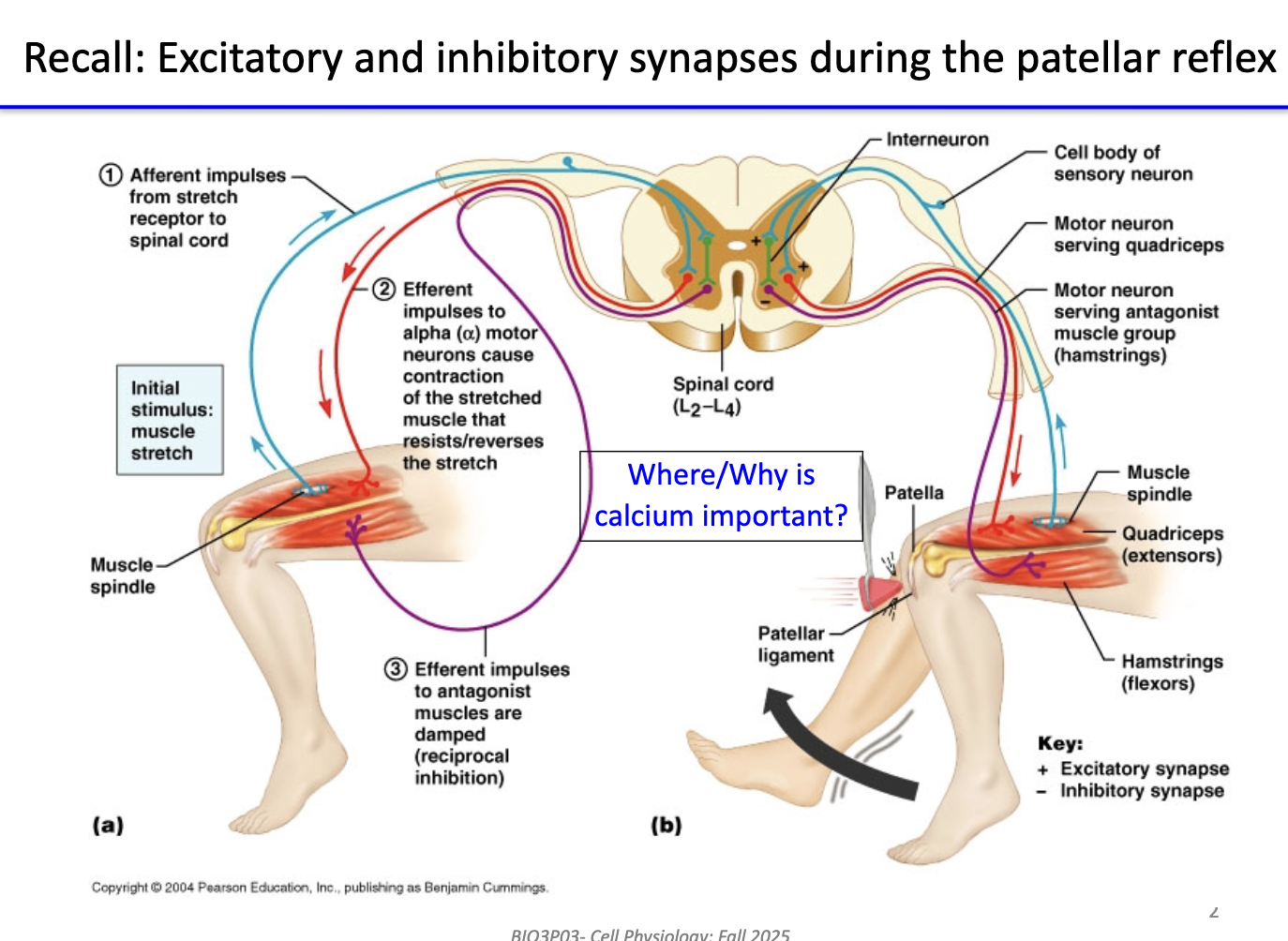

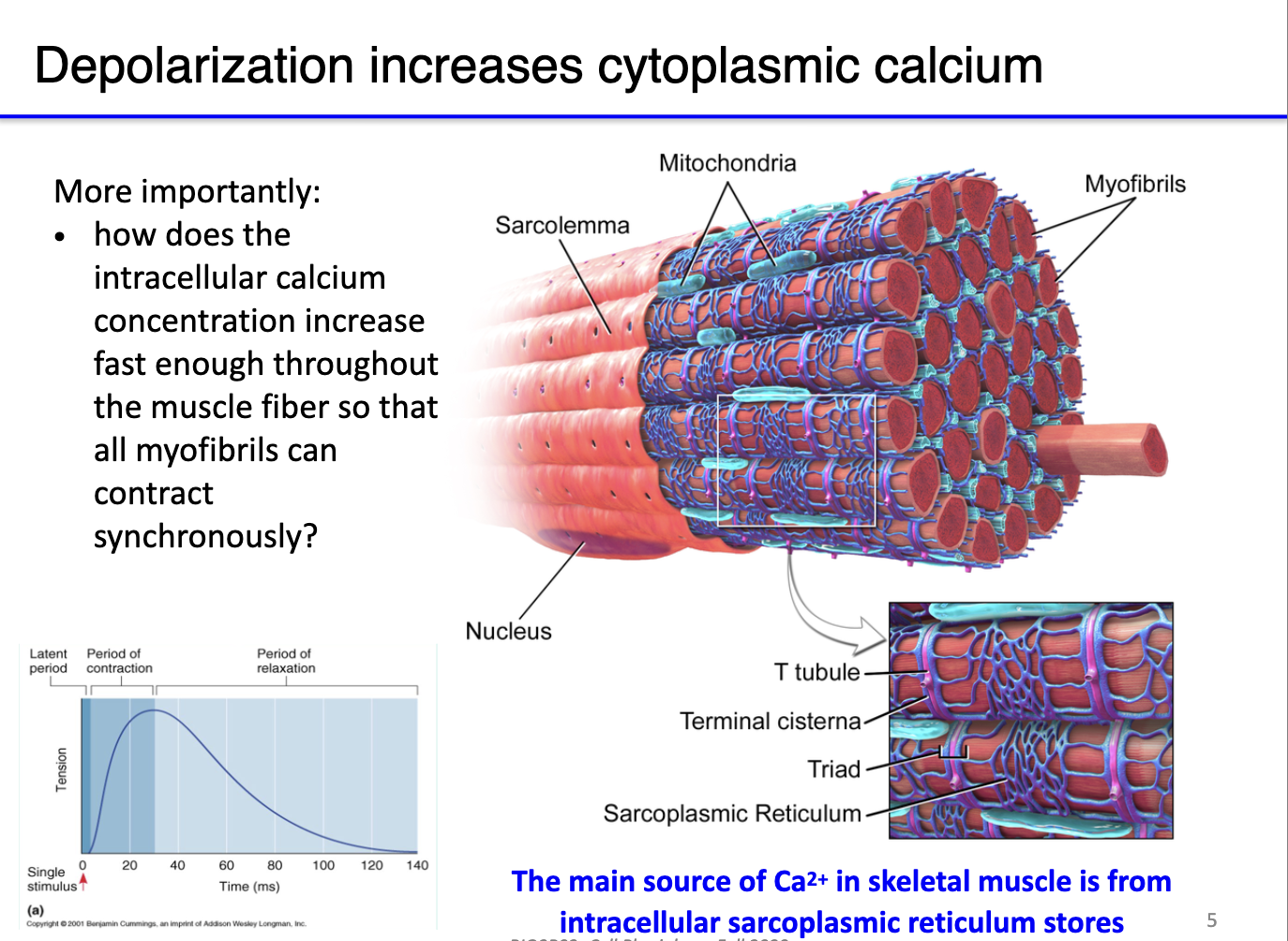

How do muscle action potentials increase cytoplasmic calcium and why is this important for contraction?

Depolarization: Muscle action potentials rapidly increase cytosolic Ca²⁺.

Sarcolemma & organelles:

Sarcolemma (cell membrane), mitochondria (ATP supply), and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) store Ca²⁺.

SR network wraps around sarcomeres to ensure uniform Ca²⁺ release.

Function:

Ca²⁺ binds troponin, moves tropomyosin → exposes actin for myosin binding.

ATP from mitochondria needed for myosin power stroke.

Without ATP → myosin binds actin but cannot contract → rigor mortis.

Key point: Efficient Ca²⁺ release and ATP availability are critical for synchronized muscle contraction.

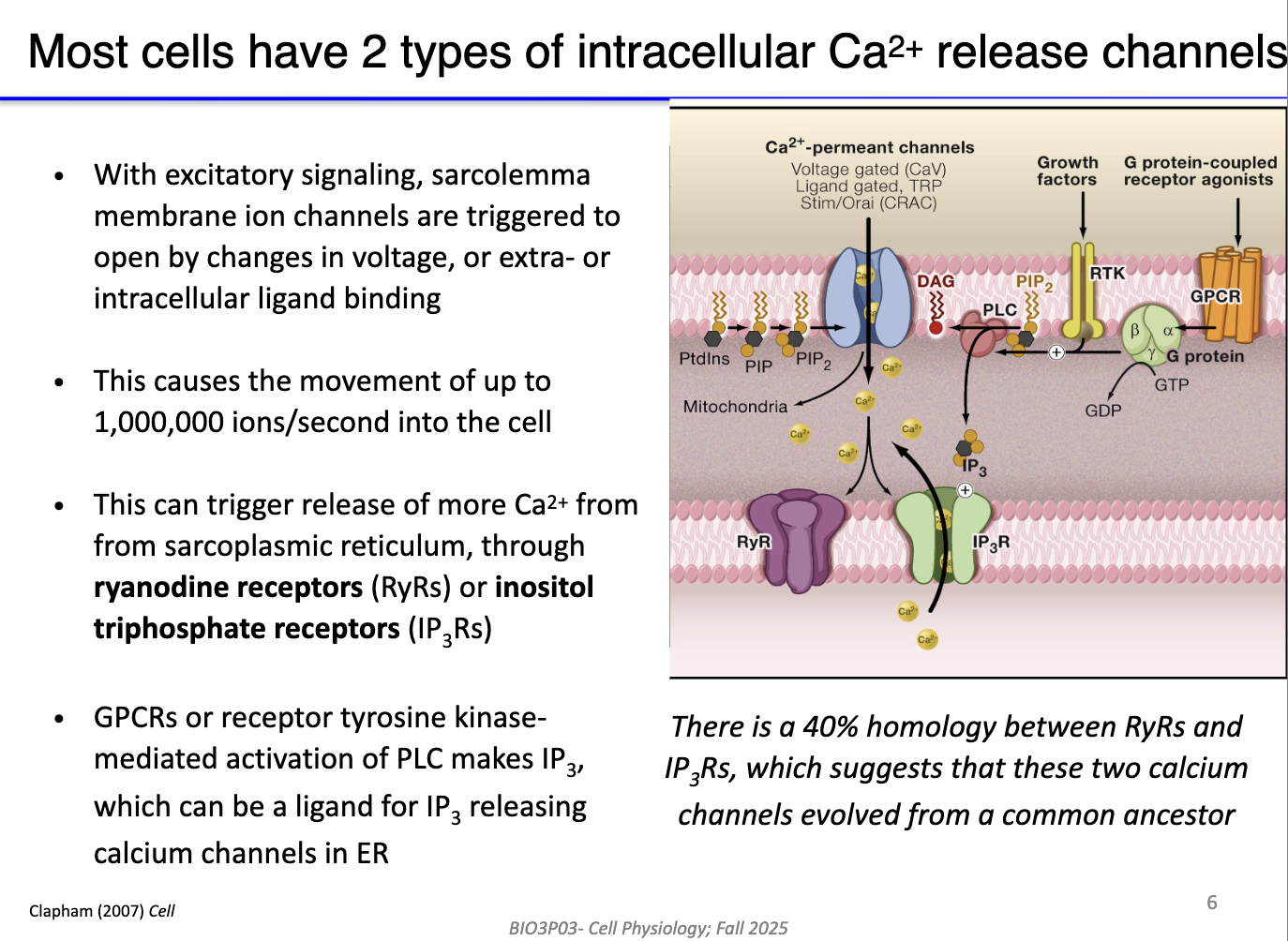

What are the main intracellular calcium release channels and how are they regulated in muscle and non-muscle cells?

Two main types of Ca²⁺ release channels:

Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) – primarily in sarcoplasmic reticulum (muscle cells).

IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) – found in SR (muscle) and ER (non-muscle cells).

Activation mechanisms:

RyRs: triggered by voltage changes or Ca²⁺-induced Ca²⁺ release (CICR).

IP3Rs: activated by IP3, produced via Gq protein → PLC → PIP2 → DAG + IP3.

Calcium flow: IP3 can diffuse through cytosol to bind IP3Rs; DAG remains membrane-bound.

Outcome: Opening of these channels rapidly increases cytosolic Ca²⁺ for contraction or signaling.

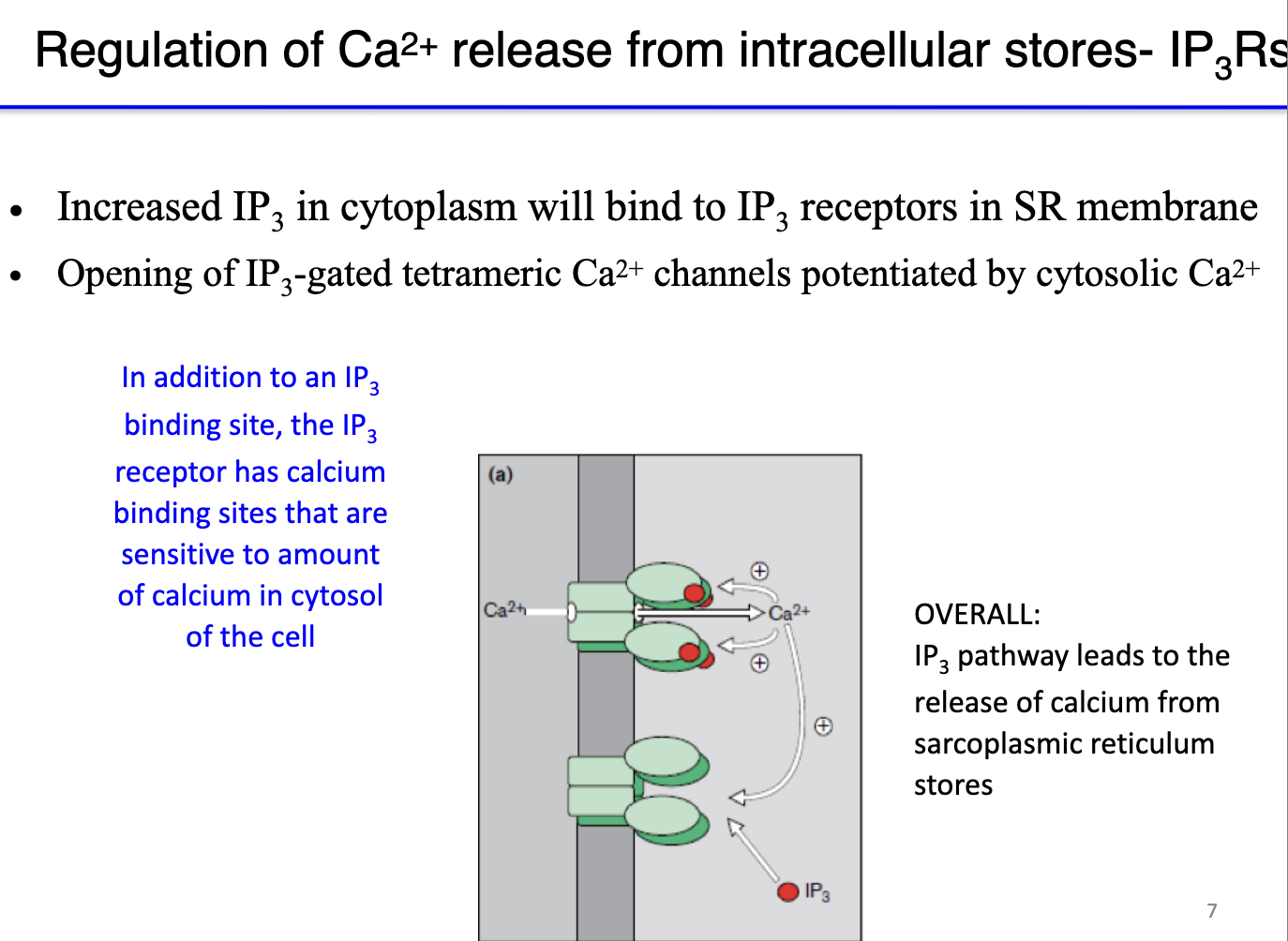

How do IP3 receptors mediate calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and what role does calcium itself play in this process?

IP3 receptor (IP3R): a ligand-gated calcium channel (ionotropic) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Activation: IP3 binds to the receptor → opens channel → releases Ca²⁺ into cytosol.

Positive feedback: low cytosolic Ca²⁺ enhances IP3R opening when IP3 binds → amplifies calcium release.

Negative feedback: high cytosolic Ca²⁺ inhibits IP3R to prevent excessive Ca²⁺ release.

Calcium binding sites: 4 sites on IP3R; calcium modulates receptor sensitivity.

Functional effect: presence of Ca²⁺ increases receptor sensitivity to IP3 (Ca²⁺ binds to receptor but doesn’t open it) → less IP3 needed for channel opening → allows rapid, regulated Ca²⁺ signaling.

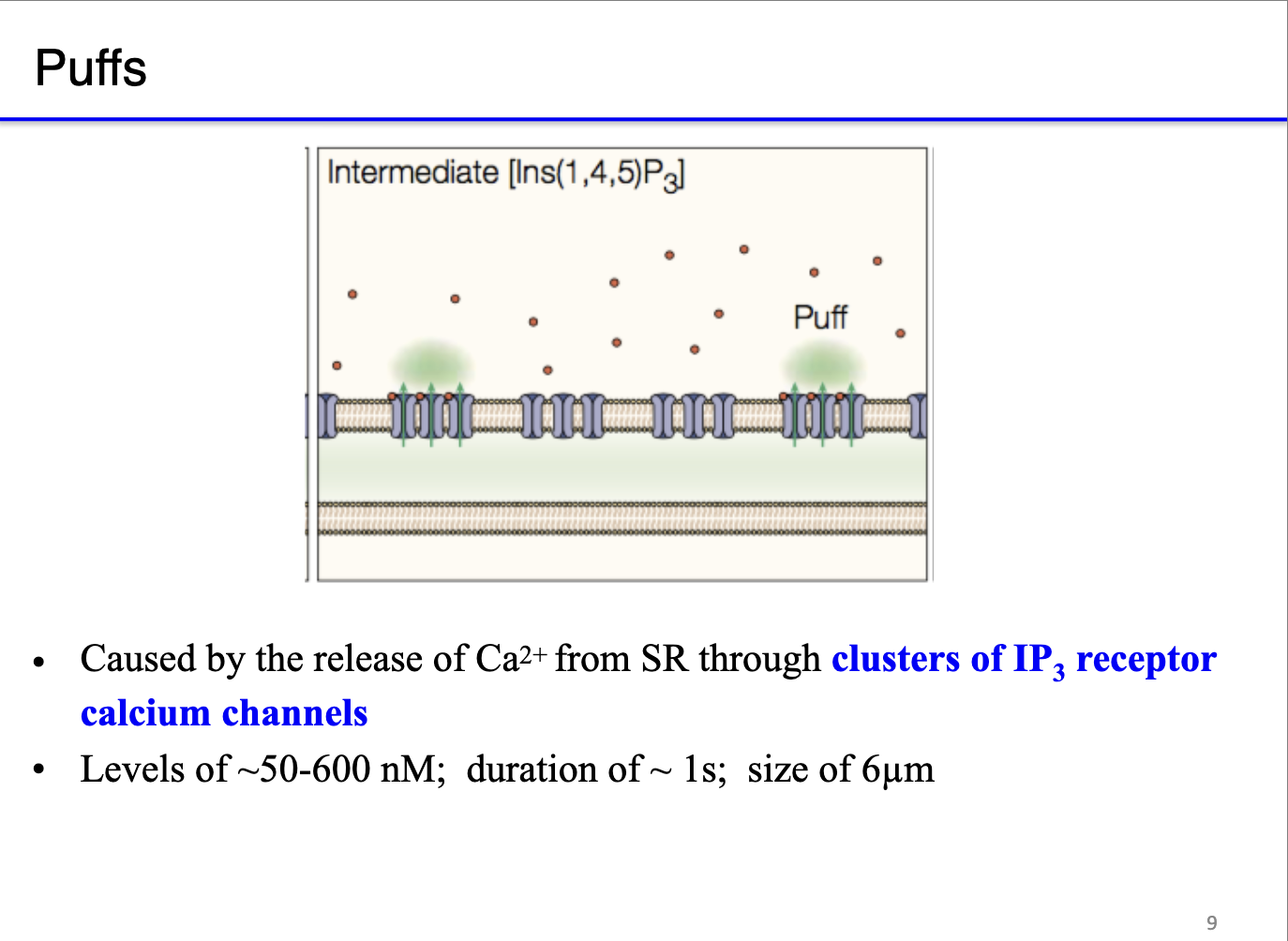

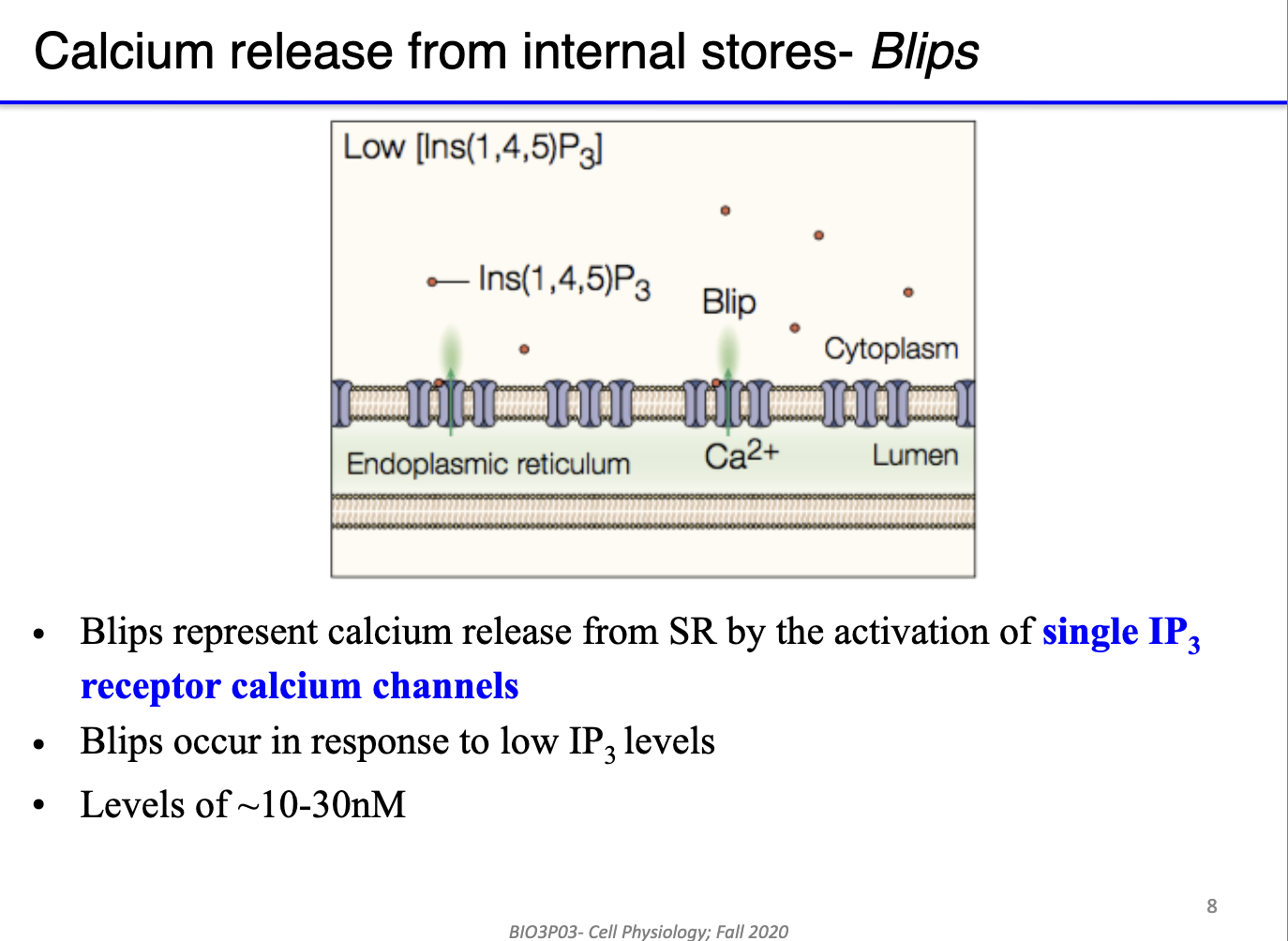

What are the hierarchical levels of calcium release from internal stores, and how do they depend on IP3 concentration?

Internal calcium stores: sarcoplasmic reticulum (muscle) or endoplasmic reticulum (non-muscle).

Blips:

Calcium release from single IP3 receptor channels.

Triggered by low IP3 levels (~10–30 nM).

Represents minimal, localized Ca²⁺ signaling.

Puffs:

Calcium release from clusters of neighboring IP3 receptors.

Triggered by higher or more sustained IP3 levels (~50–600 nM); duration of ~ 1s; size of 6μm

Produces larger, localized Ca²⁺ signals across the ER/SR.

Functional significance: hierarchical release allows graded, spatially controlled calcium signaling.

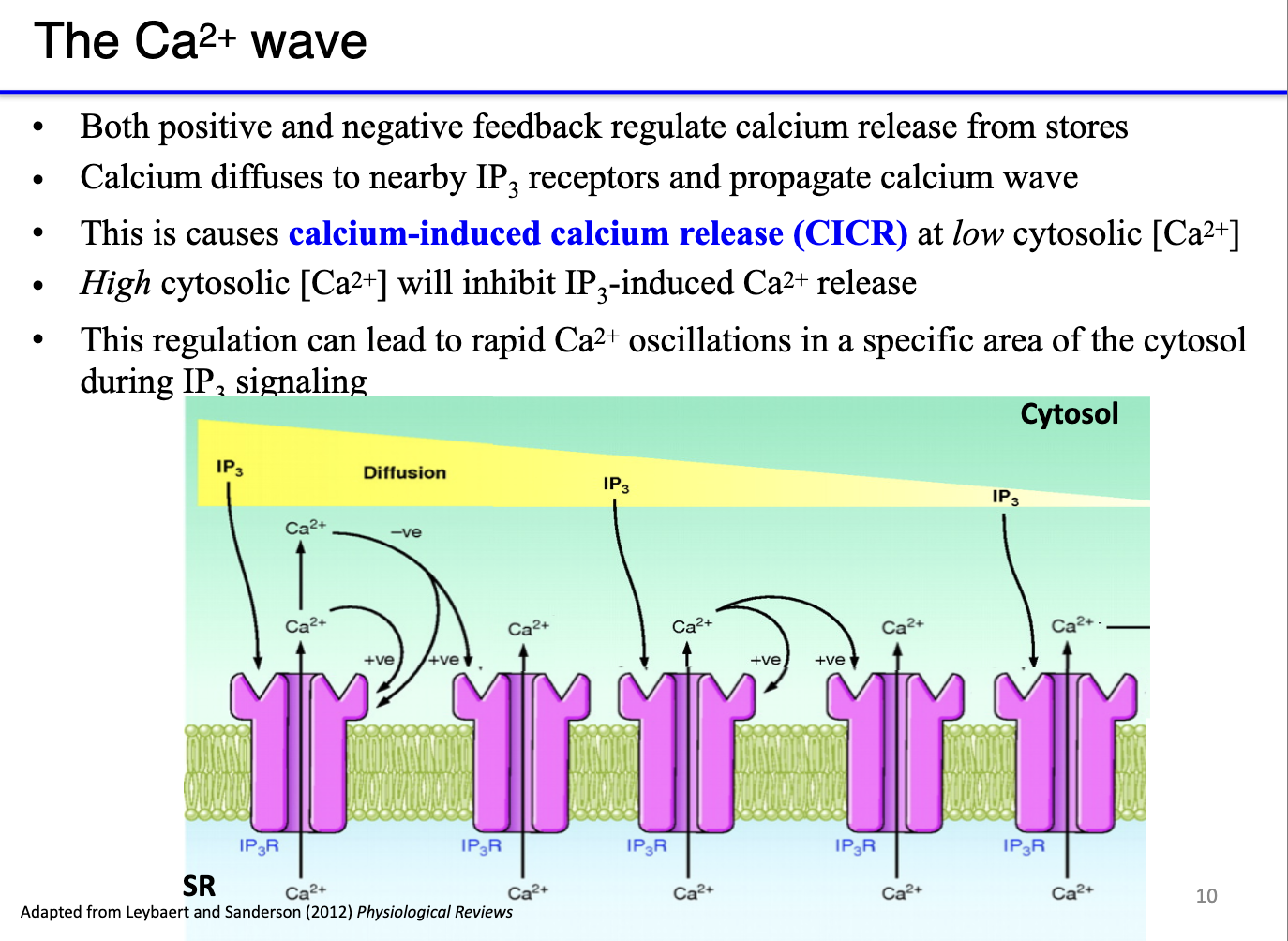

How do calcium waves form from IP3 receptor activation, and what is the role of positive and negative feedback?

Calcium-induced calcium release (CICR):

Low cytosolic Ca²⁺ → potentiates IP3 receptors (or ryanodine receptors), increasing calcium release.

High cytosolic Ca²⁺ → inhibits further release to prevent overactivation.

Mechanism of a calcium wave:

Local calcium release (puff) raises cytosolic Ca²⁺.

High Ca²⁺ at the release site negatively feeds back to inactivate those receptors.

Low Ca²⁺ at the periphery positively potentiates neighboring receptors, making them more sensitive to IP3.

Sequential activation propagates a wave of calcium release across the SR/ER.

Functional significance: ensures synchronized, directional contraction rather than random, patchy activation.

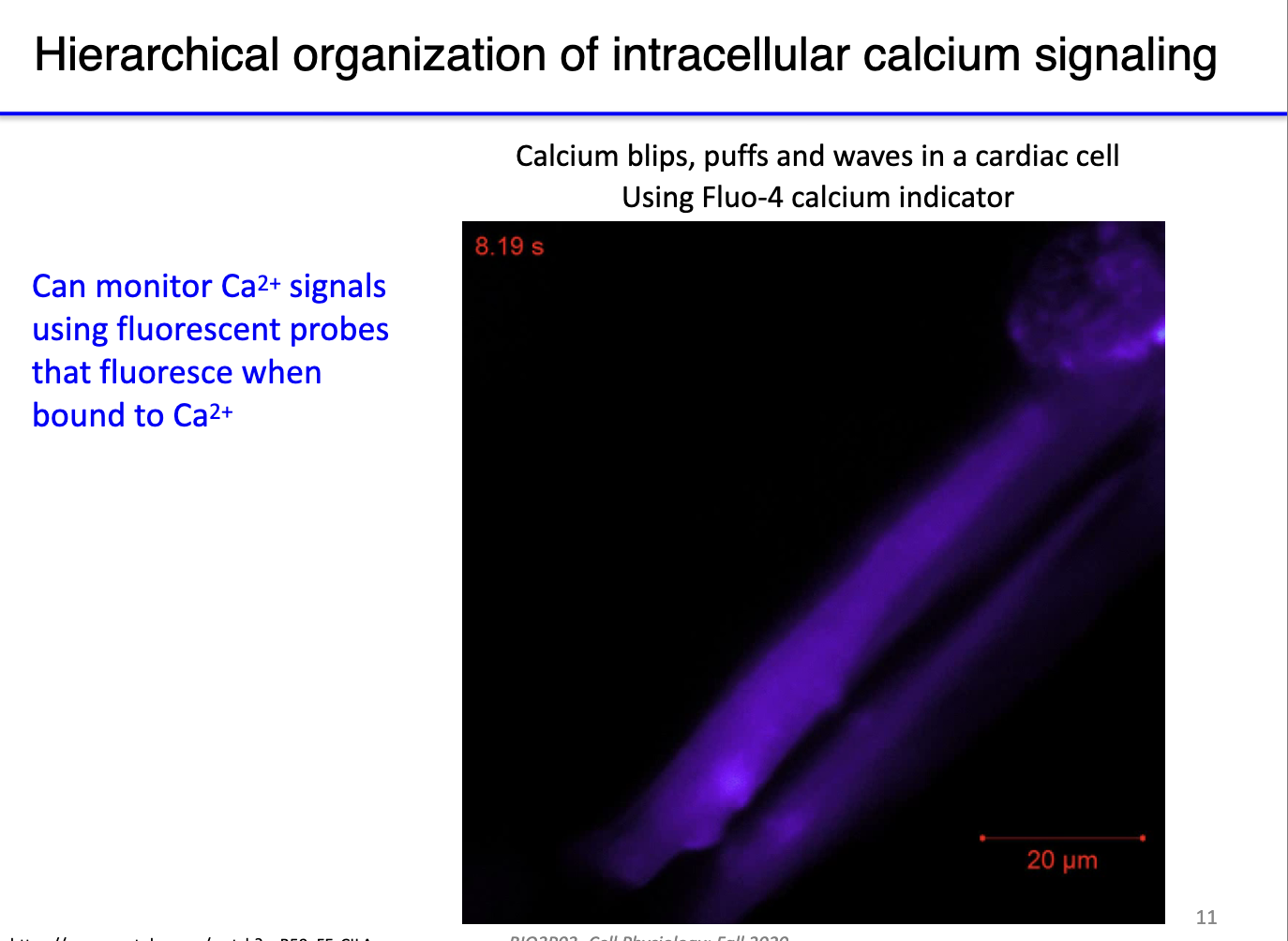

How is intracellular Ca²⁺ signaling observed?

Visualization:

Use fluorescent Ca²⁺ probes that fluoresce when bound to free cytosolic calcium.

Blips: tiny, local calcium releases (initial “lightning”).

Puffs: larger, clustered releases from multiple IP3 receptors.

Waves: coordinated propagation of calcium across the cell.

Functional significance:

In muscle cells, waves allow sequential, coordinated contraction along the length of the fiber.

Ensures efficient and organized contraction rather than random or patchy activation of sarcomeres.

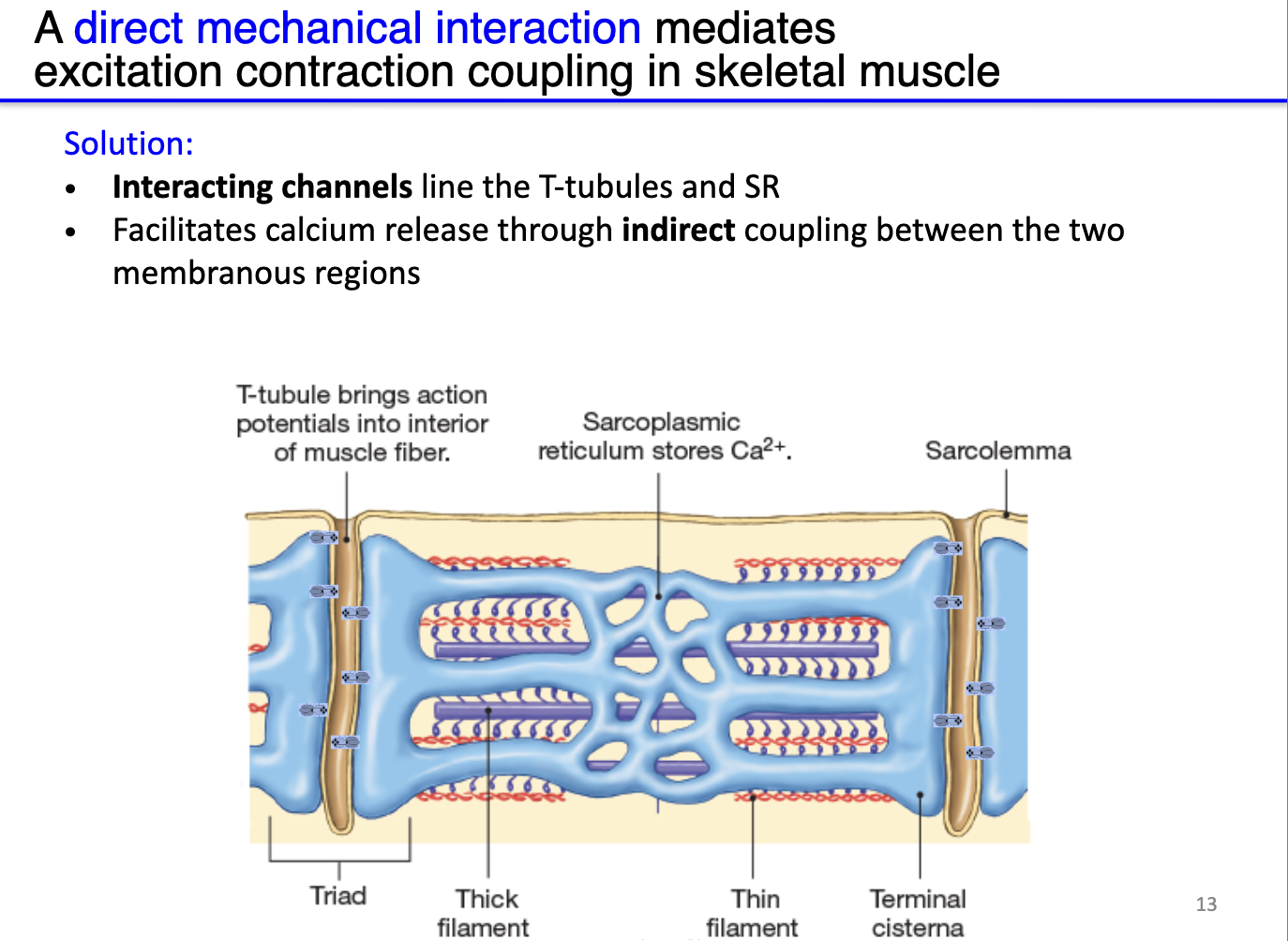

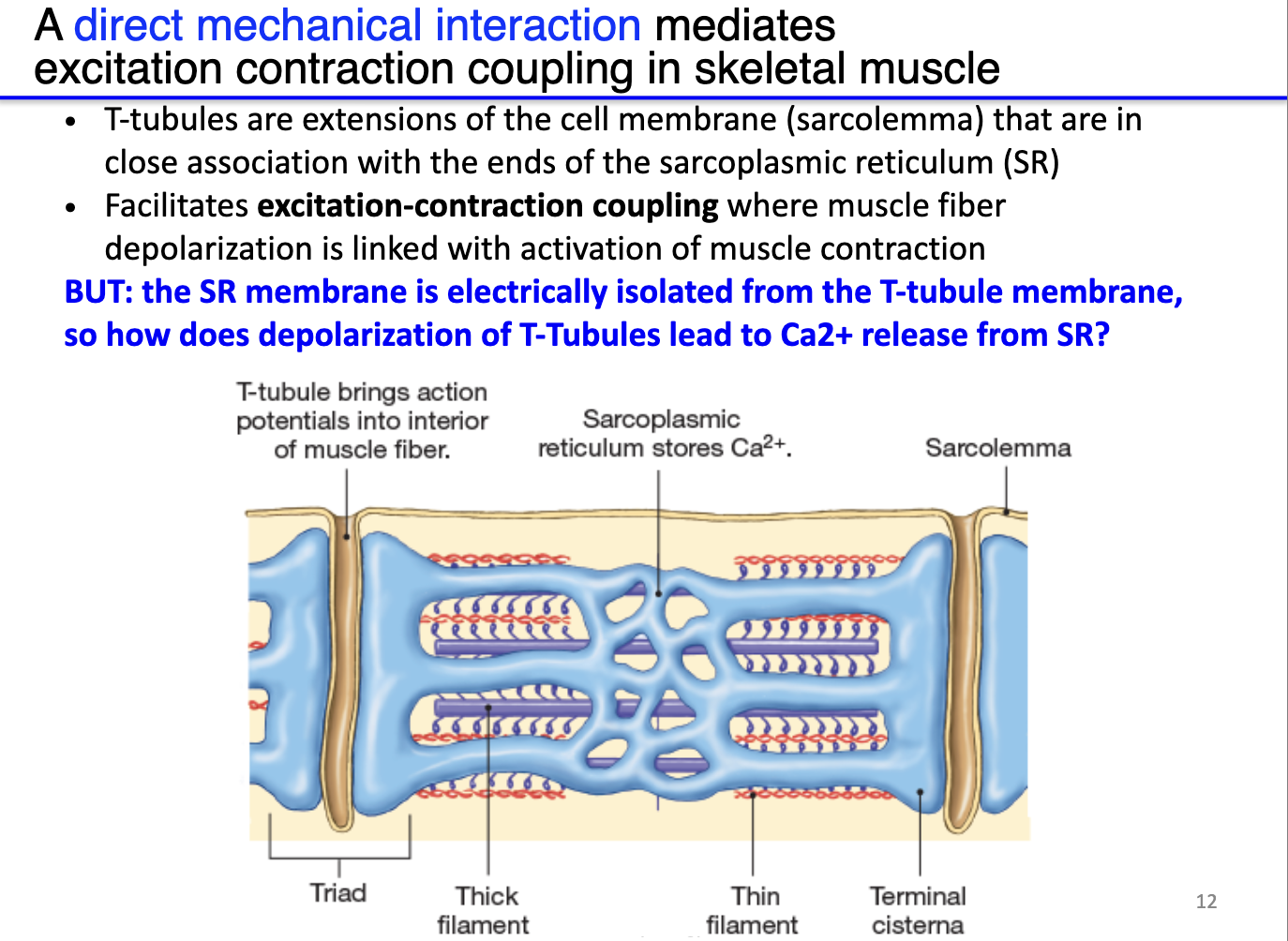

How does the structure of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and T-tubules facilitate calcium release in skeletal muscle?

Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR): stores very high concentrations of Ca²⁺, positioned near sarcomeres.

T-tubules: deep invaginations of the sarcolemma that transmit surface action potentials deep into the muscle fiber.

Triad: each T-tubule flanked by two terminal cisternae of SR, forming a structural unit for efficient Ca²⁺ signaling.

Electrical isolation: SR membrane is not directly depolarized by the T-tubule AP.

Solution – indirect coupling: physically interacting channels between T-tubules (DHPR) and SR (RyR) translate membrane depolarization into Ca²⁺ release from SR.

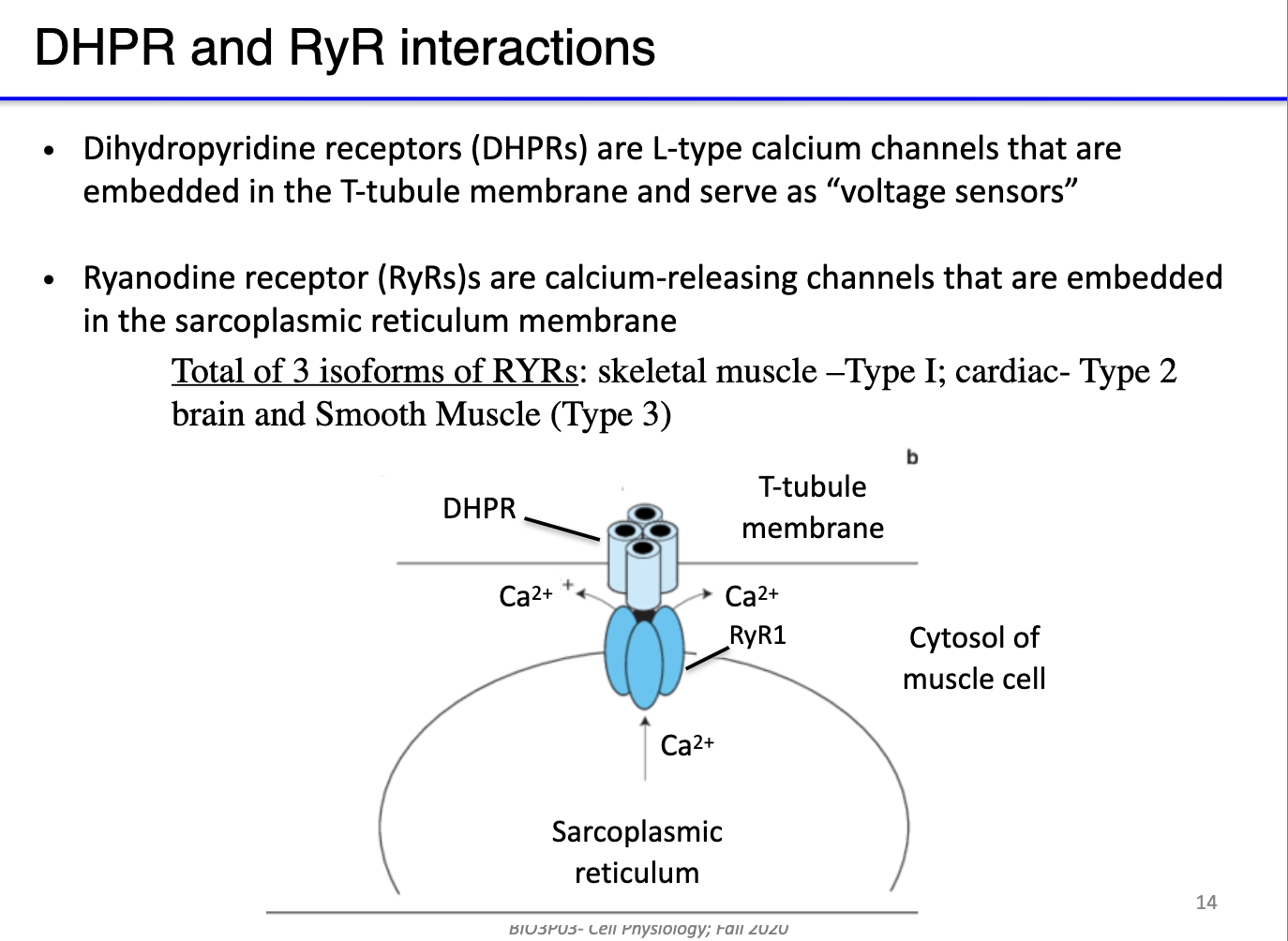

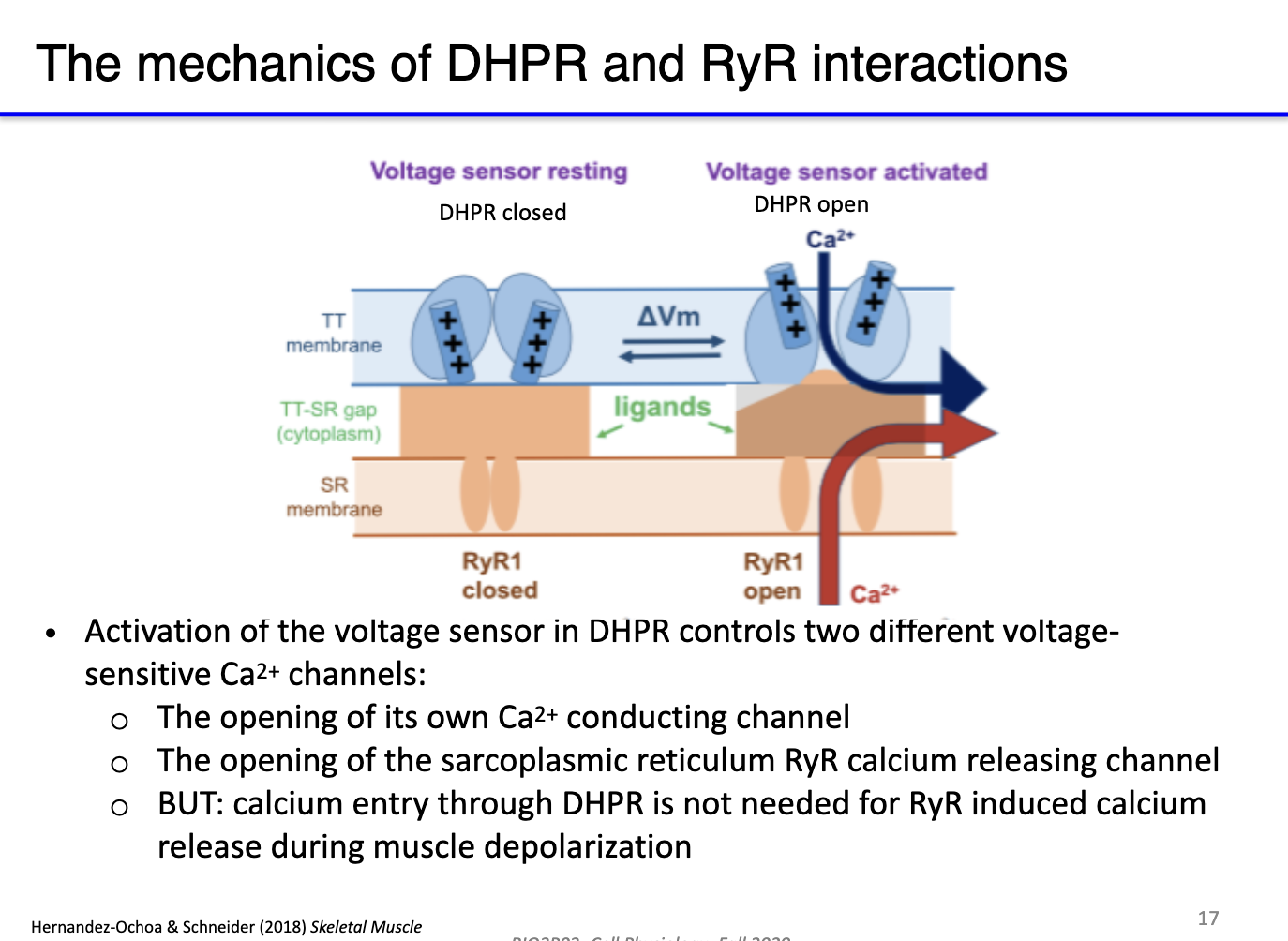

What are DHPR channels, and how do they interact with RyR in skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling?

DHPR (dihydropyridine receptors): L-type voltage-gated calcium channels located in T-tubules; act as voltage sensors.

RyR (ryanodine receptors): calcium-release channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR).

Indirect coupling: At rest, DHPR physically blocks RyR; T-tubule depolarization triggers conformational change in DHPR, opening RyR → Ca²⁺ release from SR.

Isoforms and evolution: Different RyR isoforms exist in skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle; some species (e.g., billfish) evolve RyR to create specialized functions (e.g., heater muscles) instead of contraction.

Key concept: This system links action potentials in the membrane to SR calcium release without direct electrical propagation.

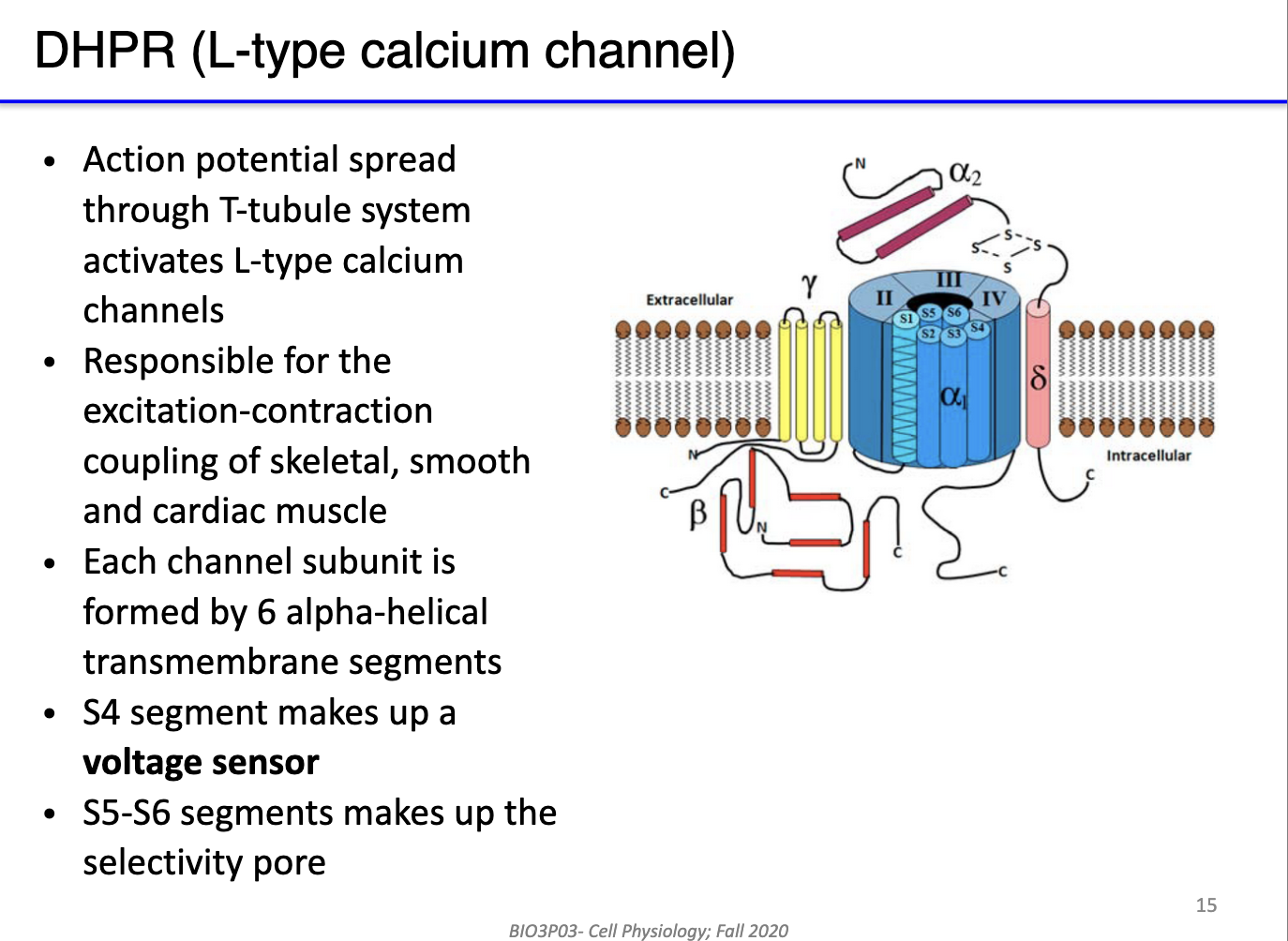

What are the key structural and functional features of DHPR (L-type) calcium channels in skeletal muscle?

Type: L-type (long-lasting) voltage-gated calcium channels in T-tubules of skeletal muscle.

Function: Serve as voltage sensors for excitation-contraction coupling; detect action potential depolarization.

Voltage sensor: Segment S4 responds to membrane potential changes.

Selectivity pore: Segments S5–S6 form the Ca²⁺-selective channel.

Role in muscle: Rapid opening upon depolarization → triggers RyR opening in SR → Ca²⁺ release → contraction.

Significance: Enables high-frequency excitation-contraction-relaxation cycles in skeletal muscle.

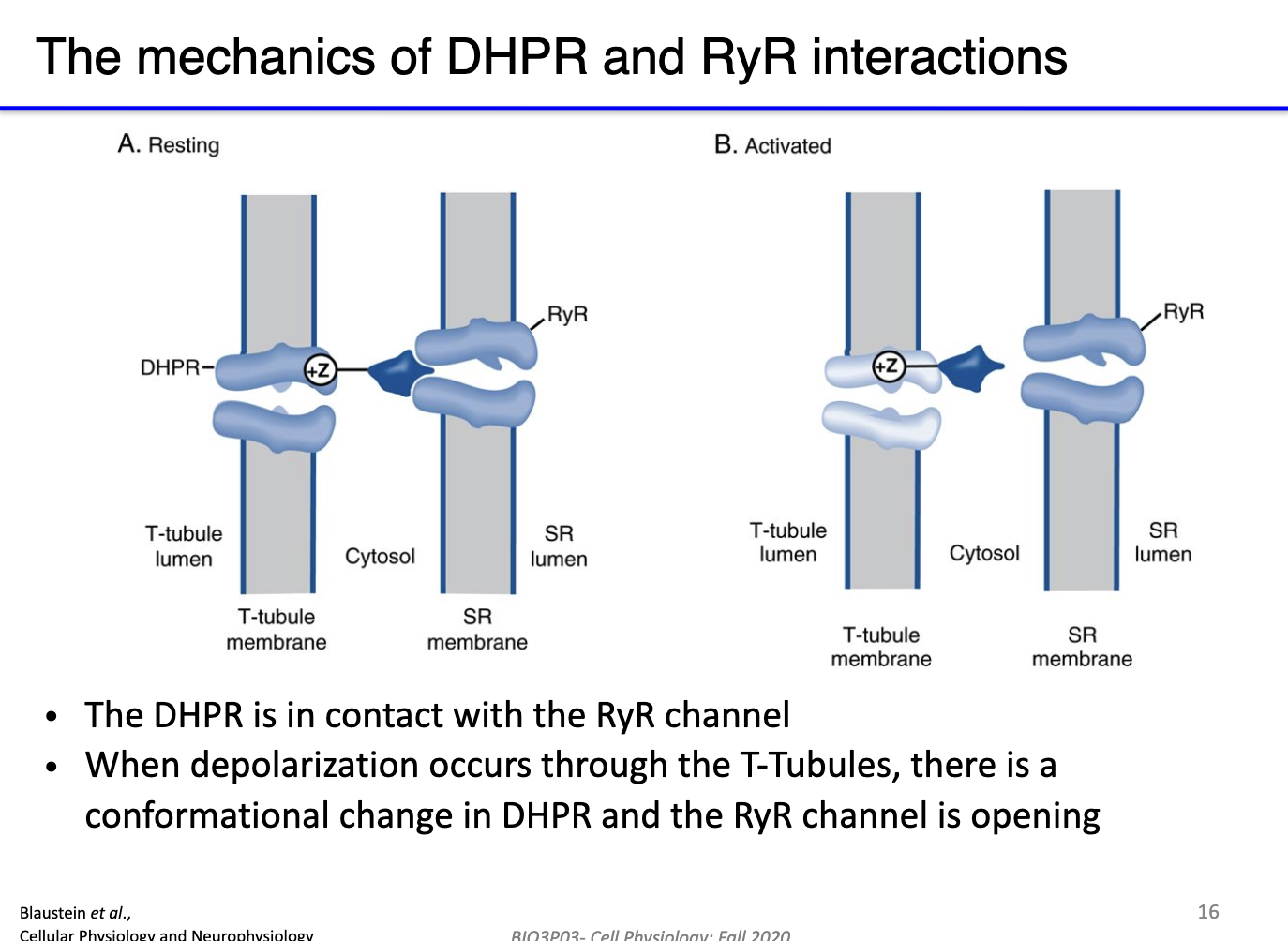

How do DHPR and ryanodine receptors work together to mediate calcium release during skeletal muscle depolarization?

Resting state: DHPR (L-type Ca²⁺ channel) has a long cytoplasmic extension that physically blocks RyR, preventing Ca²⁺ leak from SR.

Depolarization: AP travels down T-tubules → activates DHPR voltage sensor (S4 segment).

DHPR response:

Opens its own small Ca²⁺ channel → minor Ca²⁺ influx from extracellular space.

Mechanically unblocks RyR → Ca²⁺ released from SR.

Calcium-induced calcium release (CICR): Incoming Ca²⁺ further activates RyR → amplifies Ca²⁺ release.

Result: Rapid, large increase in cytosolic Ca²⁺ (mostly from SR) → triggers muscle contraction.

Why is sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium more critical than extracellular calcium for skeletal muscle contraction?

Calcium sources comparison:

SR Ca²⁺ release: Major contributor to cytosolic Ca²⁺, drives muscle contraction efficiently.

Extracellular Ca²⁺ via DHPR: Small contribution, insufficient alone to trigger full contraction.

Experimental insight: Blocking extracellular Ca²⁺ (DHPR) still allows full contraction via SR; blocking SR Ca²⁺ prevents effective contraction even with extracellular Ca²⁺.

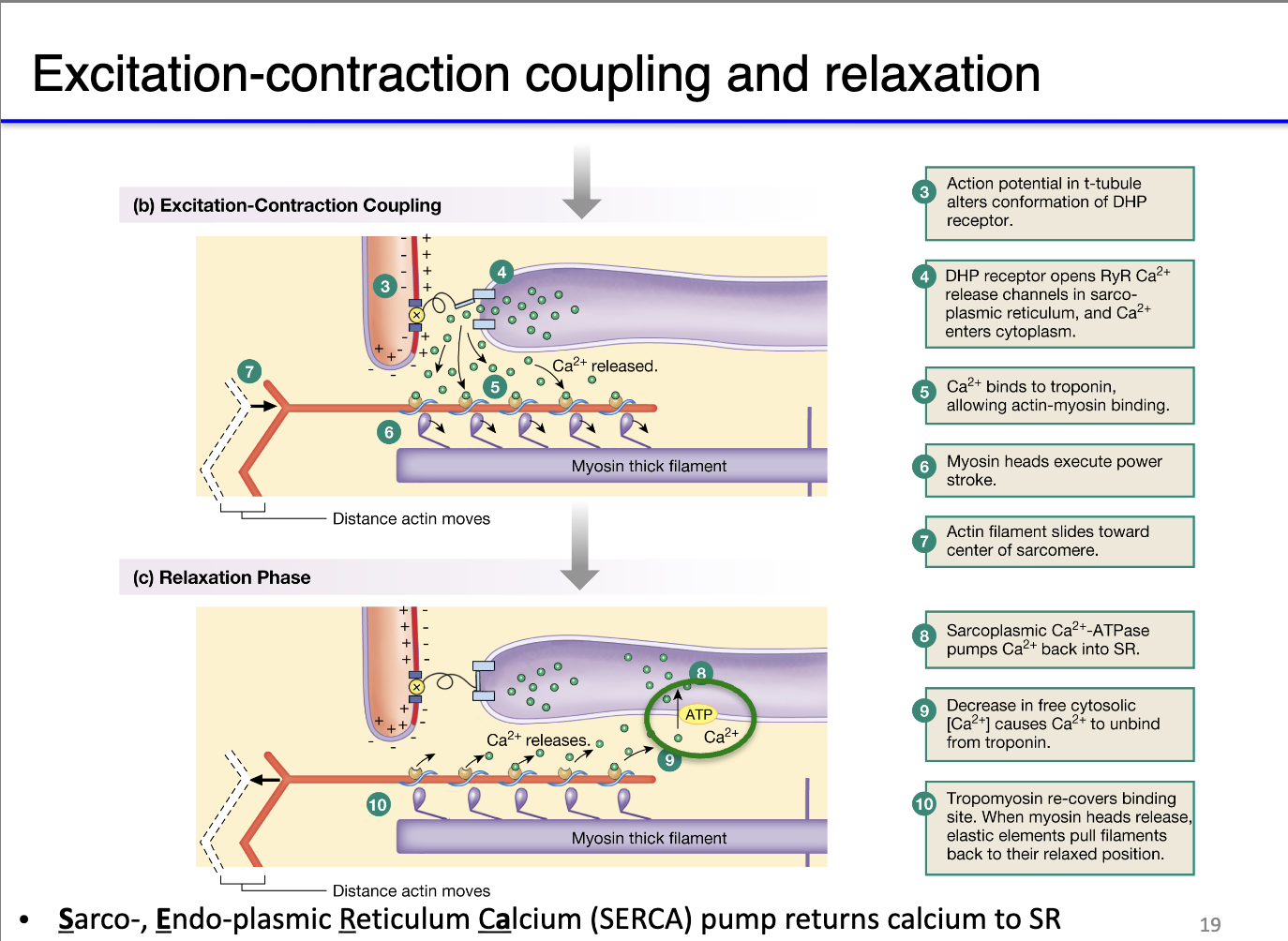

How does an action potential in a motor neuron trigger skeletal muscle contraction?

Neuron depolarization: AP reaches presynaptic terminal → opens voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels → Ca²⁺ influx.

Neurotransmitter release: Calcium signals vesicles to release acetylcholine (ACh) into the synaptic cleft.

Muscle endplate activation: ACh binds nicotinic ionotropic receptors → Na⁺ influx → endplate potential → triggers voltage-gated Na⁺ channels at periphery of end plate.

Intracellular Ca²⁺ signaling:

Small Ca²⁺ release via IP3 receptors from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) potentiates neighboring IP3 receptors and opens RyR.

AP propagates down T-tubules → DHPR (voltage-gated L-type Ca²⁺ channel) opens → mechanically unblocks RyR → large Ca²⁺ release from SR.

Muscle contraction machinery:

Cytosolic Ca²⁺ binds troponin → shifts tropomyosin → exposes myosin-binding sites on actin.

Myosin heads hydrolyze ATP → perform power stroke → sarcomere shortens → muscle contraction.

How does muscle relaxation occur after contraction, and why is rapid calcium reuptake important?

Muscle relaxation requirement: After contraction, cytosolic Ca²⁺ must be removed so tropomyosin can block myosin-binding sites → sarcomeres relax.

SERCA pumps:

Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPases (SERCA) actively transport Ca²⁺ back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

This process consumes significant ATP, making relaxation energy-intensive.

Rhythmic contractions: Rapid Ca²⁺ clearance enables quick sequential contraction-relaxation cycles, crucial for high-performance muscles and rhythmic activities.

Evolutionary/functional examples:

Billfish “heater” muscle: Leaky ryanodine receptors cause futile Ca²⁺ cycling → SERCA works harder → ATP consumption generates heat.

Athletic skeletal muscle: Efficient SERCA function allows fast, repeated contractions → supports endurance and high-speed movements.

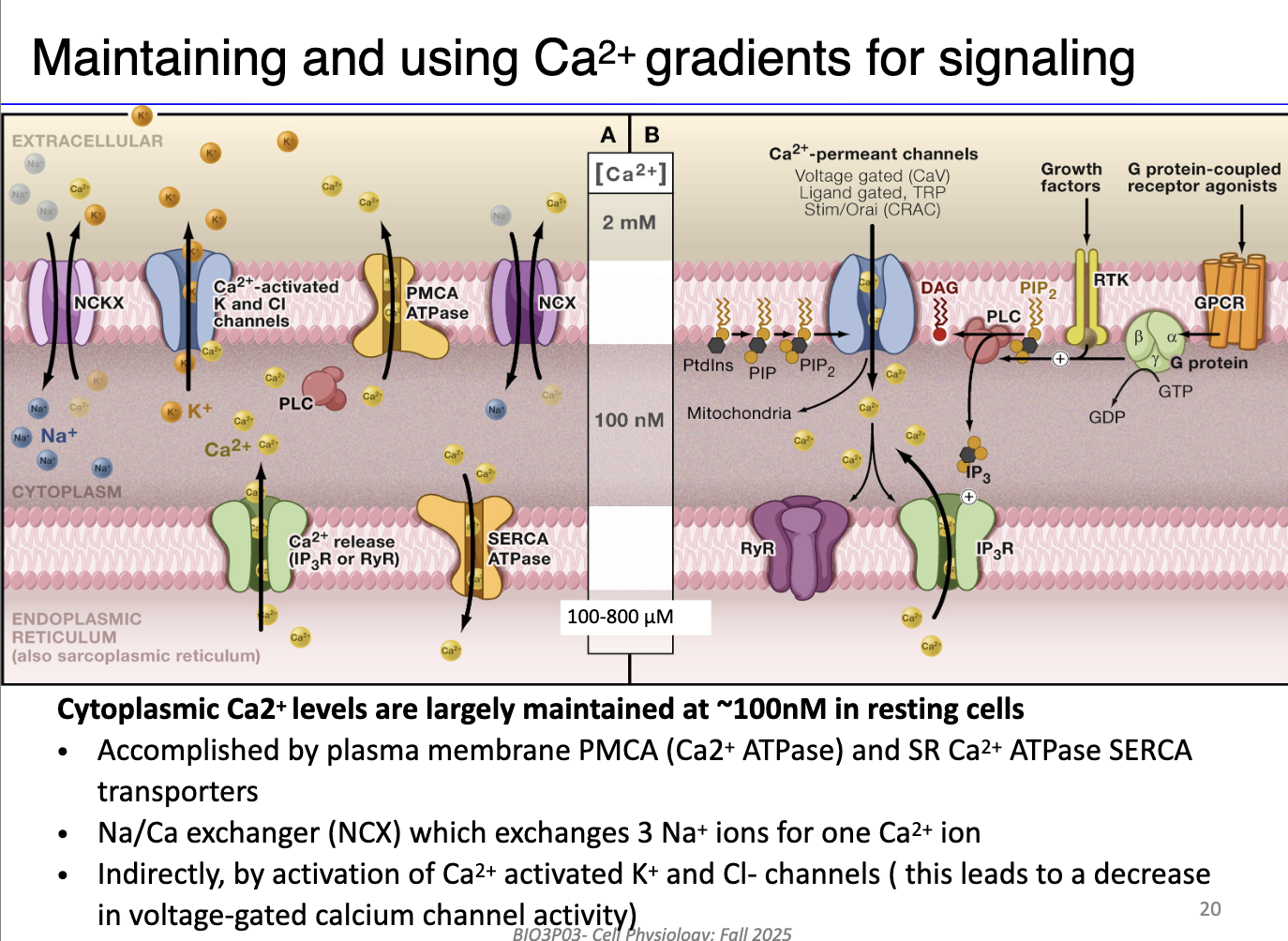

What are the main mechanisms cells use to maintain calcium homeostasis and promote muscle relaxation?

SR / ER mechanisms:

SERCA pumps: Actively transport Ca²⁺ from cytosol back into SR/ER using ATP.

IP3 receptors & ryanodine receptors: Release Ca²⁺ from SR/ER in response to signaling; regulated by positive/negative feedback.

Plasma membrane mechanisms:

PMCA (Plasma Membrane Ca²⁺ ATPase): Pumps Ca²⁺ out of the cell using ATP.

Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger (NCX): Secondary active transport; moves 1 Ca²⁺ out for 3 Na⁺ in, using Na⁺ gradient.

Ca²⁺-activated K⁺ and Cl⁻ channels: Indirectly influence Ca²⁺ homeostasis by restoring membrane potential after action potentials (not on the midterm!)

Integration with signaling pathways:

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) can activate voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels and prime IP3/ryanodine receptors for coordinated Ca²⁺ release.