photography

1/32

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

33 Terms

Define and analyze “synthetic”

Then (1850s):

“Synthetic” meant a combination or blend of real photographs.

Photographers like Gustave Le Gray combined multiple negatives to make one image.

It was still based on real, light-captured photos.

Now (AI Era):

“Synthetic” means computer-generated or data-made images.

Created by AI or algorithms, not by a camera or light.

Represents a “post-optical” world — built from data instead of reality.

Ethical Note:

AI images use massive energy and water, raising environmental and ethical concerns.

In Short:

“Synthetic” used to mean combining real images — now it means making fake ones with data.

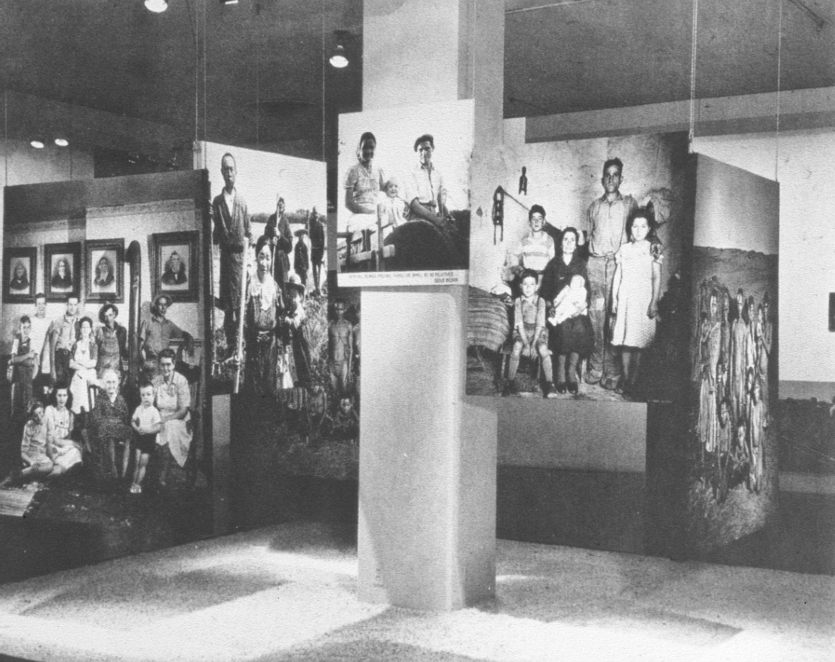

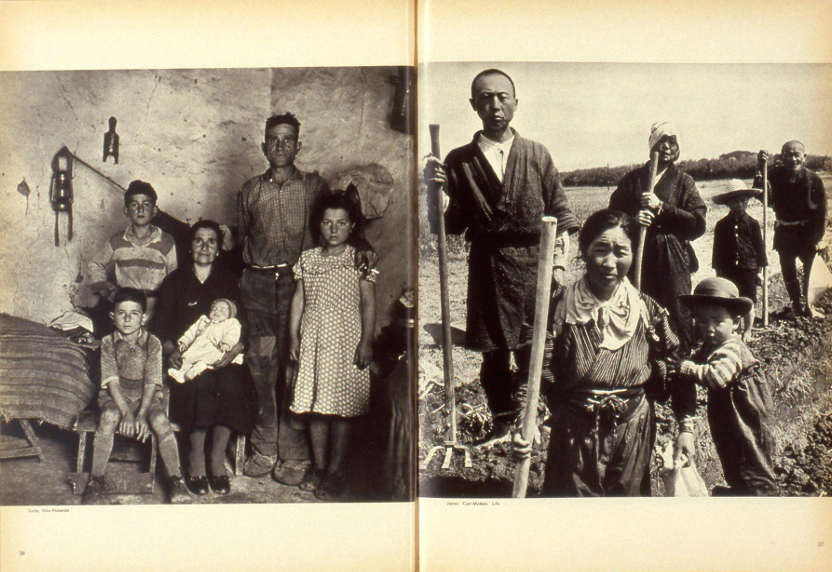

What was The Family of Man exhibition, what was it trying to achieve, and why was it criticized?

The Project (What It Was):

A huge photo exhibition curated by Edward Steichen, funded by the U.S. government during the Cold War.

Included over 500 photos from magazines like Life, showing all stages of human life — birth to death — as a story of “universal humanity.”

Traveled worldwide and was seen by millions, promoting the idea that photography was a “universal language.”

Purpose (Goals and Intentions):

Designed to promote democracy and American values during the Cold War.

Photography is a universal language and promotes the idea of a shared human experience.

Presented people around the world as connected and the same — showing “the oneness of mankind.”

The exhibition layout encouraged viewers to walk freely, symbolizing democratic freedom and equality.

Major Criticisms:

Erased real history and politics — made life look the same for everyone, ignoring inequality.

Showed Western people as modern and powerful, but non-Western people as poor or primitive.

Simplified complex issues into feel-good emotions and avoided showing conflict or struggle.

Turned photography into propaganda — beautiful, but politically naïve.

In short:

The Family of Man turned photography into Cold War propaganda for “universal humanity.”

It promoted democracy through visual design but erased difference, history, and inequality — making it both a landmark and a deeply flawed project.

Although flawed, it became one of the most influential and widely seen exhibitions in history.

Post-War Aesthetic Shifts (Cheat Card)

1. After WWII – The Change in Art:

The Holocaust and atomic bomb made artists rethink human ethics and technology.

The Cold War caused fear of nuclear destruction.

Art shifted from showing beauty or the divine to reflecting human responsibility and survival.

2. Rejecting the Sublime:

Old landscape photographers like Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams showed nature as perfect, spiritual, and pure.

After the war, this ideal view felt fake — the world was now defined by machines, cities, and destruction, not untouched nature.

3. Focus on Human Impact:

The New Topographics (1975) marked the move toward showing human-made landscapes — suburbs, highways, factories.

These images looked neutral and detached, showing how people changed the land.

Robert Frank’s The Americans continued this by focusing on modern life, cars, diners, and alienation, not beautiful nature.

4. New Artistic Strategies:

Rejecting perfection: Blur, tilt, and grain replaced sharp focus — showing emotion, movement, and uncertainty.

Concept over beauty: The idea became more important than aesthetics.

Appropriation: Artists reused ads and media images to question originality and truth.

Colour photography: Once seen as commercial, artists like William Eggleston used it to make ordinary life feel artistic.

In Short:

After WWII, photographers stopped glorifying nature and focused on human influence, imperfection, and reality — turning photography into a tool for critique and reflection, not just beauty.

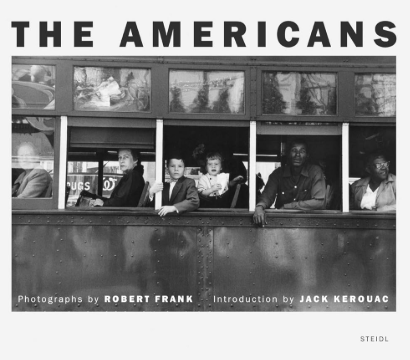

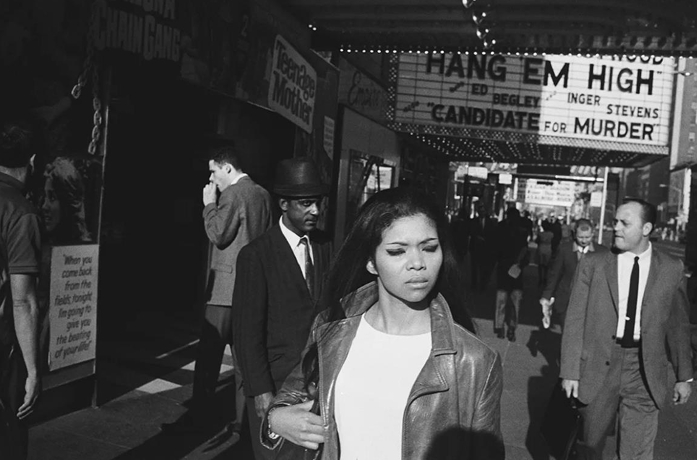

Robert Frank — The Americans

Context:

Frank’s photos capture real, everyday life in postwar America

His style uses blur, grain, and tilted framing to make the images feel alive and spontaneous.

Instead of perfect composition, he focused on emotion, movement, and imperfection.

“Poor technique”

His photos often show people looking away, through windows or mirrors, creating a feeling of distance and voyeurism.

The sequencing of images and repetition of flags, cars, diners, and parades create a rhythm that feels like a visual road trip across America.

Themes:

Frank’s work shows alienation, loneliness, and division in postwar America.

He focused on people often left out of mainstream representation — showing class, race, and gender inequalities.

His photos reveal the contrast between American ideals and lived reality, exposing both pride and emptiness beneath the surface of everyday life.

Frank used black and white to express “hope and despair,” turning the road itself into a symbol of freedom and disconnection.

Why It’s Relevant:

The Americans rejects the idealized optimism of The Family of Man and instead shows a fractured, uncertain nation.

Frank’s emotional, imperfect style broke away from traditional photography and inspired artists to value honesty and feeling over technical perfection.

His project became a new way to see America — not as united, but divided, complex, and deeply human.

In short:

Frank’s America is fragmented — a land of beauty and loneliness, where race, class, and technology quietly define belonging.

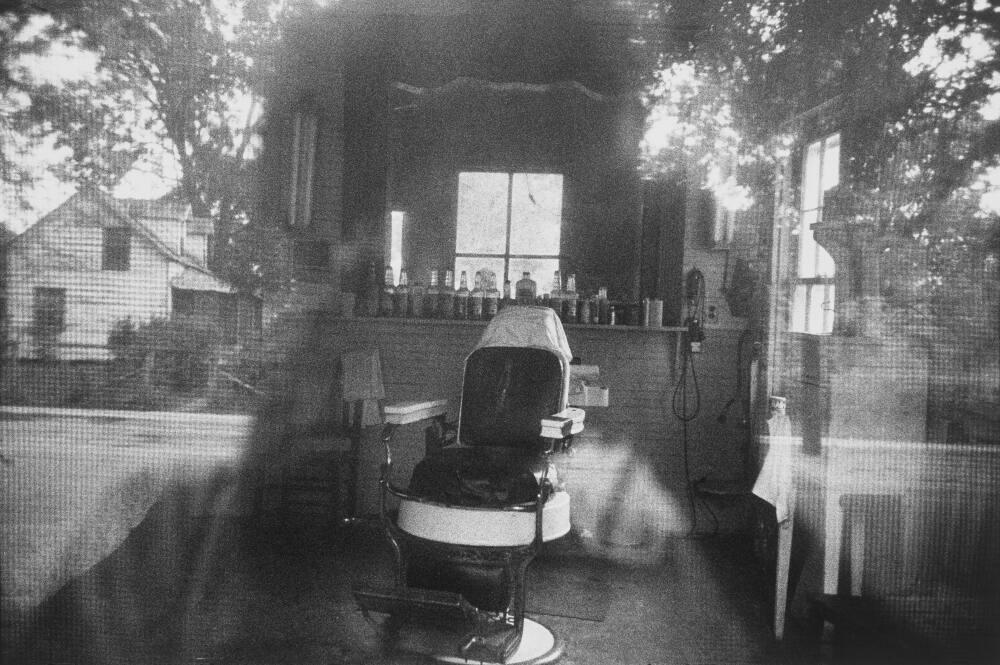

Robert Frank, Barber shop through screen door – McClellanville, South Carolina, 1955.

Visual Analysis:

Frank photographs a quiet, empty barbershop from outside, shooting through a mesh screen door.

The screen softens the image and creates a barrier between the viewer and the interior, making the space feel distant and unreachable.

The empty barber chair is centered, surrounded by bottles and mirrors — traces of human presence without any people.

Natural light from the window creates contrast between the bright outside and the dim interior, emphasizing emptiness and stillness.

This layering of reflections makes the viewer aware of their own act of looking — we’re not simply observing a place, we’re looking through something, like Frank himself observing America from a distance.

The mood is quiet, haunting, and lonely. The absence of people suggests loss, isolation, and disconnection — even ordinary spaces meant for social interaction (like a barber shop) feel empty or abandoned.

Conceptual Meaning:

This image captures Frank’s recurring themes of isolation, alienation, and distance.

It reflects his position as a foreign observer looking into American life.

The photo also comments on photography itself — showing that every image is filtered, partial, and mediated.

The screen door reminds us that photography is not neutral; it always involves perspective, framing, and limitation.

Why It’s Important:

This photograph is a perfect example of Frank’s shift away from idealized, “beautiful” American images.

Instead of showing optimism or community, it captures silence, absence, and emotional distance — making it both poetic and unsettling.

It also represents Frank’s break from traditional documentary photography: his focus on atmosphere, imperfection, and feeling over technical clarity.

In Short:

Frank uses the empty barber chair, the screen door, and the ghostly reflections to show how isolation and distance define modern American life. The photo becomes a metaphor for being on the outside looking in — both socially and emotionally — and for how photography itself always filters what we see.

La Jetee Question 1:

Why do you think Marker chose to use still images for this “film”?

Why emphasize photography in a medium devoted to movement?

Why do you think Marker chose to use still images for this “film”?

Marker used still images to show how memory works as frozen moments, not continuous motion.

Each photograph represents how memories are fragmented, static, and incomplete, like flashes from the past.

The story centers on a man haunted by one childhood memory — a single image of a woman on a jetty.

That one frozen image becomes his emotional anchor and symbol of how we relive the past.

The stills reflect how memory preserves moments but can’t bring them back to life.

In short:

Marker used still images to mirror how memory works — fragmented, frozen, and incomplete. We don’t remember life as continuous motion but as a series of mental photographs.

Why emphasize photography in a medium devoted to movement?

Marker emphasized photography to remind viewers that film is built from still images, and to explore time, emotion, and mortality.

By freezing motion, he forces us to confront how fragile life and time really are.

The film’s stillness contrasts with the idea of cinema as constant movement — it stops time instead of showing it flow.

The one moment of motion — when the woman blinks — feels deeply human and emotional, symbolizing life breaking through stillness.

Photography becomes a metaphor for how we hold onto moments that are already gone.

In short:

The stillness emphasizes the theme of time and memory, making the film feel dreamlike and reflective. The single moment of movement — when the woman blinks — becomes deeply emotional because it briefly breaks the stillness, symbolizing life within time’s still frame.

La Jetee Question 2:

What symbolic meaning can you imagine for setting the film underground?

Literal Setting:

The story takes place in underground tunnels after a nuclear war destroyed the surface of the Earth.

Survivors live below ground because the surface is uninhabitable — they are cut off from space, light, and freedom.

Symbolism:

Imprisonment & Despair:

The underground represents humanity’s entrapment — people are trapped physically and emotionally after the war.

It mirrors feelings of trauma, loss, and isolation, like being buried alive in memory.

Time as Escape:

Since they can’t move across space, they turn to time for survival.

Time travel becomes a way to search for hope — the only freedom left is through memory and imagination.

Psychological Meaning:

The tunnels act like the subconscious mind — dark, hidden, and full of fragments from the past.

It reflects the postwar condition: humanity scarred by its own destruction but still searching for light.

Hope in Darkness:

Even in this confinement, the time-travel experiments show that memory and imagination might still save what’s left of humanity.

In short:

The underground symbolizes imprisonment, trauma, and exile after war.

With the world above destroyed, people must turn inward — into time, memory, and imagination — to find hope and survival.

La Jetee Question 3:

What meaning do you take from the scene in the natural history museum, when the man and the woman contemplate stuffed and suspended birds?

Context:

This scene happens once the man can travel freely into the past.

He and the woman walk through a museum filled with stuffed birds — “eternal animals” that look alive but are frozen in time.

1. Symbolism of the Museum:

The museum represents a space outside of time — life preserved but unmoving, just like the film’s still images.

It’s like the man’s memory — a place where moments are stored and kept alive only through remembrance.

The setting mirrors the film’s frozen structure — everything appears alive, yet nothing truly moves.

The museum, a space of preservation, mirrors the mind — a collection of still, eternal moments. Like photography, it captures what’s gone, allowing love and time to survive only as images.

2. The Stuffed Birds — Life, Death, and Memory:

The birds symbolize life held in suspension — beautiful but dead, like a photograph of a memory.

They connect directly to the film’s themes: time, loss, and the illusion of permanence.

Just like memories, the birds seem real but can never live again — they are frozen proof of what once was.

3. The Relationship Within Time:

The man and woman’s love exists outside time — it’s pure but temporary.

Their connection is like the birds — preserved, perfect, but already lost.

She accepts his mysterious appearances as normal, showing how their love exists in a timeless dream state.

In short:

The museum scene symbolizes timelessness, memory, and frozen love.

The stuffed birds reflect both the film’s still images and the man’s memories — life paused between past and present, love and death.

La Jetee Question 4:

Memory is central to this film. And photography is often considered to be a kind of external memory, an attempt to hold on to something that no longer exists. Can you identify ways in which La Jetée explores the relation between memory and photography?

Main Idea:

In La Jetée, memory and photography are the same thing — both try to hold onto what no longer exists.

The film uses still images to show how the past survives only as frozen fragments, just like photographs.

1. Photography as Memory

The film is made completely from still photographs, which resemble memory fragments rather than continuous experience.

These stills mimic the way memory functions—frozen, selective, and fragmented, rather than smooth and continuous like film.

The narrator’s memories are shown through these fixed images, showing how we remember key “snapshots” from the past rather than whole scenes.

2. The Still Image as a Mix of Time

The photos in La Jetée blend past, present, and future, showing that memory isn’t something we just “find again” — it’s something we recreate.

The main idea — a man haunted by an image from his childhood that turns out to be the moment of his death — shows how memory shapes who we are.

Just like a photograph, one frozen moment can define how we understand our entire past.

3. Photography as External or Artificial Memory

The narrative shows how memories are reconstructed and can be manipulated, just like photographic images.

The story also shows that memories can be rebuilt or changed, just like photos can be edited.

By showing a future world that uses memory (through still images) to travel through time, Marker suggests that remembering the past is always uncertain and imperfect.

In short:

La Jetée uses still photographs to blur the line between memory and photography.

Each image is a frozen trace of time, holding loss and repetition.

Marker shows that memory, like photography, both records and recreates — it helps us witness what’s gone, but can never fully bring it back.

What are Gillian Rose’s four primary sites of analysis?

The Site of Production

Where and how the image is created.

The Site of the Image Itself

What’s inside the image and how it looks.

The Site(s) of Circulation

How the image travels and is shared.

The Site of Audiencing

How people see, react to, and interpret the image.

How can one of Gillian Rose’s sites of visual analysis help interpret Robert Doisneau’s Un Regard Oblique (1948)

Main Idea:

The Site of Audiencing looks at how viewers see and react to an image.

In this photo, our attention is drawn to acts of looking — who is looking, at what, and how we feel about it.

Visual Focus:

A man secretly glances at a painting of a nude woman in a shop window.

His partner appears unaware or unimpressed, while the photographer secretly captures the moment from inside the shop.

The image becomes a study of voyeurism, gender, and social behavior — who gets to look and who is looked at.

Interpretation (Site of Audiencing):

As viewers, we become aware of our own gaze — we’re also “looking” at the man who is looking.

The photo makes us think about how images control attention and how looking can be gendered or taboo.

It also reveals how photography turns people into objects of spectacle, much like the art in the window.

In Short:

Using the Site of Audiencing helps us see how Un Regard Oblique plays with the act of looking. The man stares secretly at the nude painting while his partner looks away, revealing the male gaze. As viewers, we also feel like voyeurs — aware of our own act of looking. This reaction shows how meaning depends on the audience’s emotional and moral response.

Explain Semiotics

Definition:

Semiotics is the study of signs — how words, images, and objects carry meaning in a culture.

It explains how we create and understand meaning through shared social codes and conventions.

Main Ideas:

Meaning isn’t natural — it’s learned through culture.

We understand things (like red = stop) because of shared cultural rules.

Semiotics helps us decode signs and understand how they work in communication, art, or media.

A signifier is the form something takes — like a word, sound, or image.

A signified is the idea or concept that comes to mind when you see or hear it.

Together, they make a sign, which is how meaning is created.

Example:

A red light doesn’t naturally mean “stop,” but in our culture, we’ve agreed it does.

That shared agreement gives the sign meaning.

In Short:

Semiotics is the study of signs and how we create meaning through them. It looks at how we interpret things — like images, words, or symbols — based on shared cultural understanding.

For example, the color red doesn’t naturally mean “stop,” but we’ve learned to associate it with that meaning through culture.

A signifier is the form a sign takes — like a word, color, or image — and the signified is the idea or concept it represents. Together, they form a sign, which gains meaning through social and cultural context.

Explain early examples of Pop Art. What is Pop Art, and why is it significant?

Main Idea:

Pop Art used everyday media and mass culture (ads, magazines, TV) to turn consumer imagery into art.

It questioned originality and blurred the line between high art and popular culture.

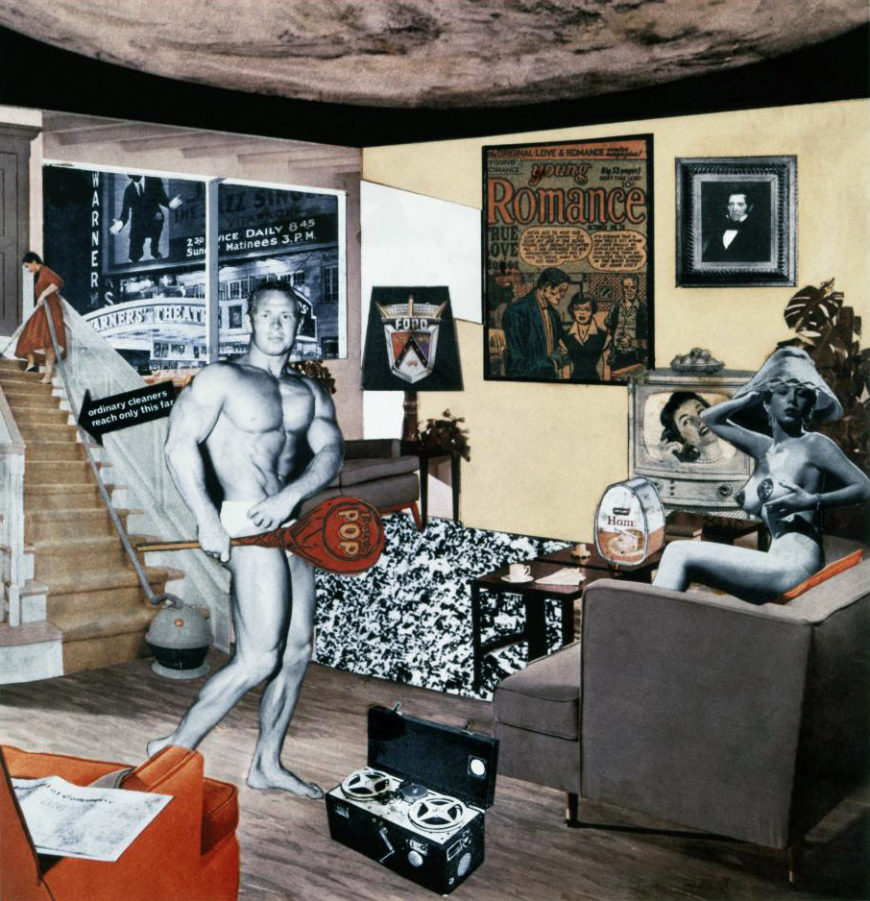

Example: Richard Hamilton

Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956)

Early Pop Art collage made from magazine cutouts.

Combined advertising, celebrity, and domestic life into one image.

Represented consumer culture, desire, and media overload.

Defined Pop as: popular, mass-produced, cheap, young, witty, glamorous, big business.

Why It Works Conceptually:

Used appropriation — borrowed and repeated existing media images.

Undermined ideas of authenticity and originality.

Reflected how modern life was built from mass media and consumption.

Example: Martha Rosler

House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72; 2004–08)

Collaged war images (Vietnam, later Iraq) with magazine interiors.

Made the “living-room war” literal — violence shown inside ideal homes.

Critiqued media control, gender roles, and American comfort during wartime.

Why It’s Important:

Used Pop and Conceptual Art strategies (collage, appropriation) to make a political statement.

Showed how consumerism hides global suffering.

Example: Richard Prince — Untitled (Cowboy), 1989

Re-photographed a Marlboro ad, removing text.

Exposed how advertising constructs masculinity and identity.

Showed that even ads can be artifacts of culture, not “truth.”

In Short:

Pop Art turned mass media and consumer culture into art.

It’s significant because it:

Challenged originality and authorship.

Critiqued consumerism, media, and politics.

Blurred the line between everyday life and fine art.

Carleton E. Watkins — Half Dome, Yosemite, California (c. 1870)

Visual Analysis:

Watkins presents a monumental view of Half Dome, framed by trees and a reflective river that leads the viewer’s eye into the distance.

The image is perfectly balanced — every element contributes to a sense of harmony, clarity, and order.

The sharp focus, smooth tonal range, and crisp detail give the landscape a timeless, almost sacred quality.

The absence of any human presence heightens the illusion of untouched wilderness, suggesting nature as eternal and pure.

Light softly illuminates the mountain peak, giving it a divine, transcendent aura — as if blessed or chosen.

Conceptual Meaning:

Embodies the 19th-century concept of the Sublime, where nature inspires both awe and fear through its scale and grandeur.

Reflects a spiritual vision of nature — nature as a moral and restorative force in contrast to the chaos of modern life.

Reinforces the myth of uninhabited wilderness, erasing Indigenous presence and aligning with Manifest Destiny, the belief that expansion into the West was divinely justified.

This “empty” landscape implies possession and control — transforming land into an image of American progress and national identity.

Photography becomes not just an art form but a tool of empire, using beauty to justify colonization and settlement.

Why It’s Relevant:

Marks a turning point where photography began shaping national ideology and environmental imagination.

Establishes how images of “pure” landscapes can carry political power — connecting beauty with ownership.

Watkins’s landscapes helped promote the creation of national parks, but they also contributed to the displacement of Indigenous communities.

Later movements, like the New Topographics (1970s), rejected this idealized vision, exposing how human activity and industry had transformed the “natural” world.

Keywords:

Sublime • Manifest Destiny • Imperial gaze • Untouched wilderness • National identity • Moral landscape • Romanticism

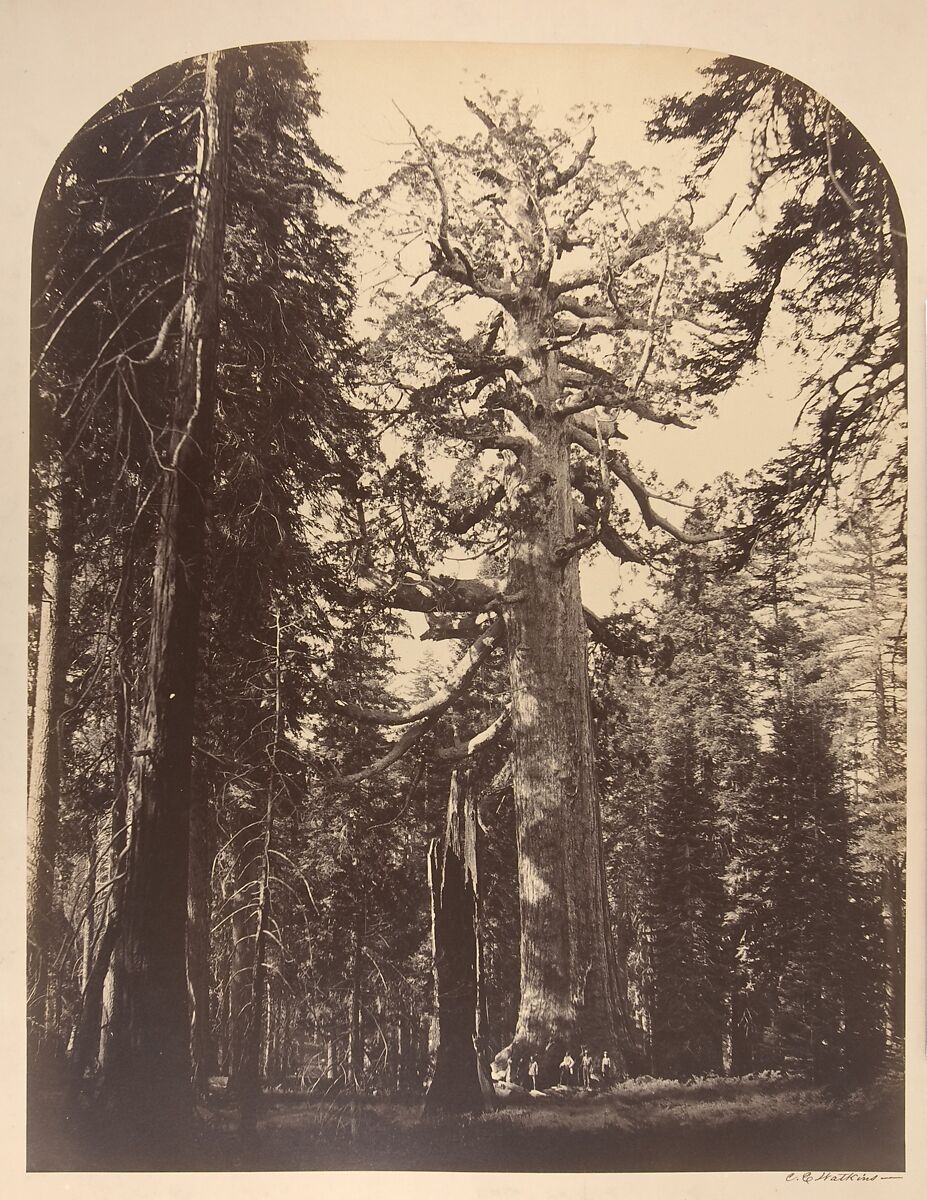

Carleton E. Watkins — The Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove (1861)

Visual Analysis:

Watkins captures the massive sequoia from a low angle, letting it dominate the entire frame.

Tiny human figures at the base emphasize its overwhelming scale and power.

The sharp detail and long exposure enhance the texture of the bark, the play of light and shadow, and the vertical grandeur of the forest.

The image feels cathedral-like, as if nature itself were a temple — silent, sacred, and monumental.

The composition leads the viewer’s eye upward, inspiring awe and reverence.

Conceptual Meaning:

Embodies the 19th-century Sublime — nature as both majestic and spiritual, larger than human comprehension.

The tree becomes a symbol of endurance, national pride, and divine order, reflecting the belief that nature revealed God’s power.

Reinforces the ideology of Manifest Destiny — portraying the land as “Edenic” and uninhabited, erasing Indigenous presence.

Watkins’s images helped inspire preservation movements (like Yosemite’s protection) but also carried colonial undertones — framing land as something to be possessed and admired by settlers.

Why It’s Relevant:

Establishes photography as both an artistic and political tool — shaping how Americans viewed land and nature.

Represents the moral and aesthetic roots of American landscape photography — blending environmental wonder with national propaganda.

In Short:

Watkins’ "The Grizzly Giant" (1861) captures a monumental redwood from a low angle, emphasizing its immense scale and intricate detail. The photo embodies the 19th-century Sublime — nature as majestic, pure, and godlike. Yet, this “empty wilderness” erased Indigenous presence and reinforced Manifest Destiny, framing the land as untouched and available for conquest. It’s relevant because it shows how early photography turned nature into a symbol of national identity and ownership.

Carleton E. Watkins — Cape Horn near Celilo (1867)

Visual Analysis:

A railroad curves through the Columbia River Gorge

The composition unites mechanical geometry with natural beauty.

The strong diagonals draw the viewer’s eye into the distance.

Conceptual Meaning:

This image suggests a harmonious merging of nature with technological progress.

It serves as “a visual metaphor for manifest destiny”

Why It’s Relevant:

Bridges romanticism and modernity — showing how early photography naturalized industrial colonization.

Keywords: Industrial sublime, expansion, progress, harmony, colonization, modernity.

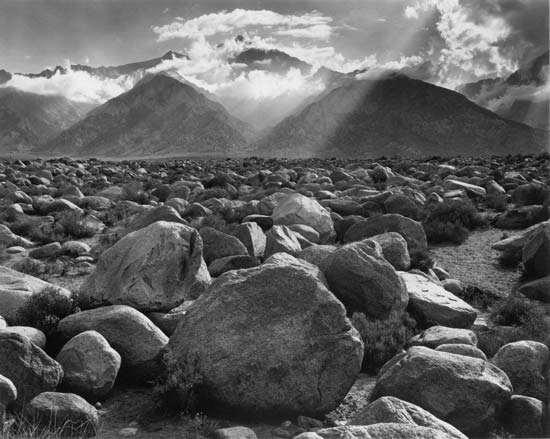

Ansel Adams — Mount Williamson: Clearing Storm (1944)

Visual Analysis:

Large boulders fill the foreground, leading toward misty, sunlit mountains in the distance.

Adams uses sharp focus and dramatic lighting — bright clouds break through a dark storm, creating a balance between chaos and calm.

Every rock feels monumental, showing order within nature’s power.

Conceptual Meaning:

Made during World War II, the image symbolizes strength, endurance, and renewal after destruction.

Adams believed nature was pure and moral, a spiritual escape from the violence of modern life.

He presents the land as timeless and sacred — a moral landscape untouched by politics or human pain.

The photo reflects a postwar hope that beauty and nature could restore faith in humanity.

Why It’s Relevant:

Represents the height of spiritual and idealized landscape photography, continuing the 19th-century Sublime tradition of Watkins.

Later photographers rejected this approach for being too apolitical — ignoring war, inequality, and industrial reality.

Marks the shift between romantic nature worship and the more critical photography that followed.

In Short:

Adams turns the mountain into a symbol of faith and resilience — nature as the moral center of a broken world. It’s beautiful and inspiring, but also shows the limits of seeing nature as separate from human struggle.

Anonymous (U.S. Dept. of Defense) — VIP Observers Watching Atomic Explosion (1951)

Visual Analysis:

A row of seated VIPs watch a nuclear explosion from the comfort of lounge chairs.

The calm, orderly foreground contrasts with the destructive power in the distance.

Their relaxed posture and matching goggles create an eerie mix of leisure and catastrophe.

Conceptual Meaning:

Shows the technological sublime — awe at human invention mixed with fear of its power.

Reveals Cold War detachment — how people became spectators of destruction.

Suggests complicity: these elites watch violence as spectacle, not tragedy.

Why It’s Relevant:

Marks the shift from natural to technological sublime — machines replace nature as the new source of wonder and terror.

Symbolizes how postwar culture normalized surveillance, control, and distant violence.

Later conceptual artists reacted against this moral numbness and spectacle-based media.

Keywords:

Technological sublime • Spectatorship • Cold War fear • Complicity • Moral detachment

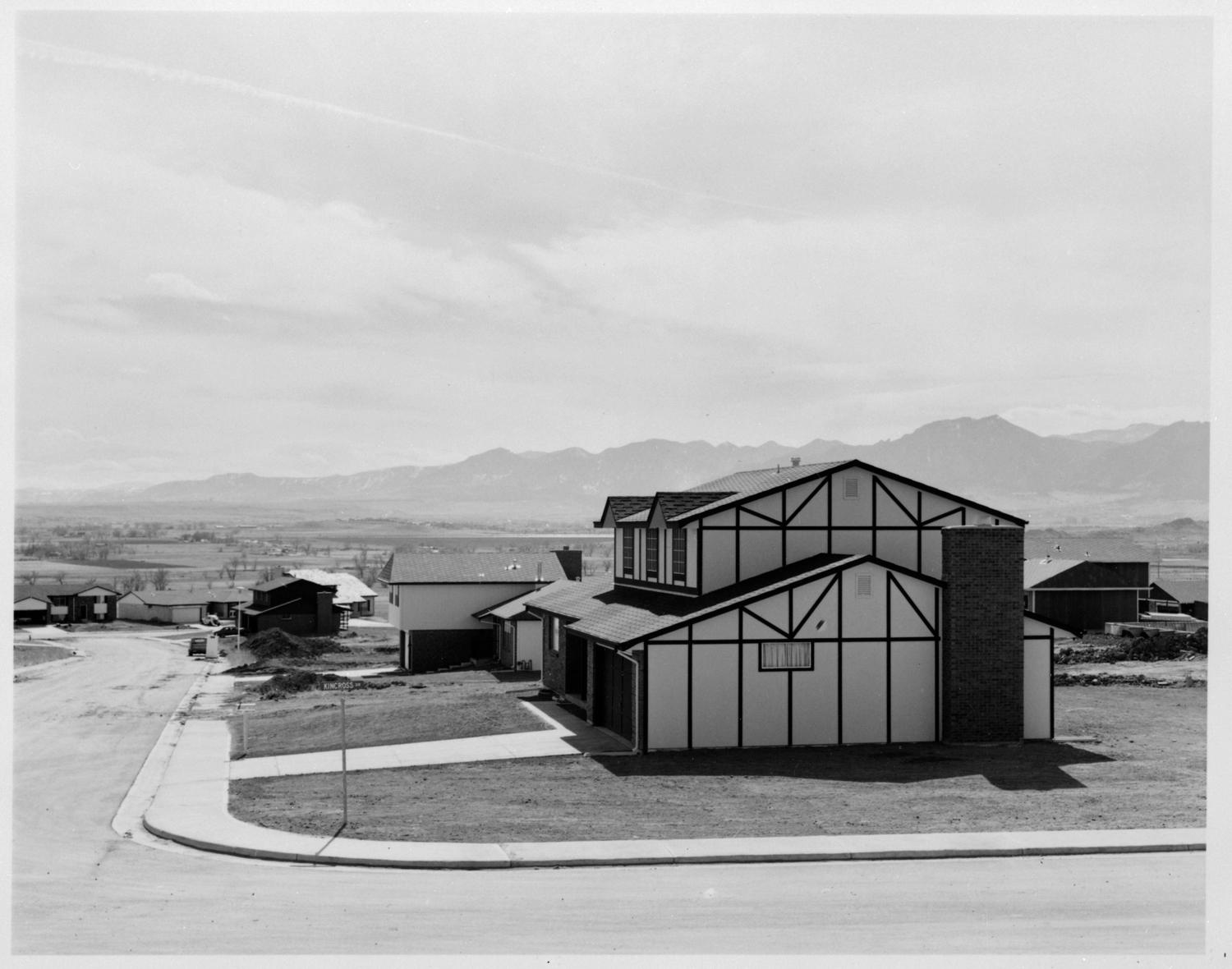

Robert Adams — Tract House, Boulder County, Colorado (1973)

Visual Analysis:

Shows rows of identical suburban houses under flat, dull light.

No people, no drama — just quiet repetition and stillness.

Conceptual Meaning:

Captures the “man-made landscape” — how suburbs replaced nature.

Finds beauty in the ordinary and asks viewers to noquiet damage humans cause to the environment.

Why It’s Relevant:

Changed how photographers saw landscapes — not as beautiful scenes, but as honest records of human impact.

A key image from the New Topographics movement that focused on truth over beauty.

Keywords: New Topographics, neutrality, banality, suburbanization, human impact, ethics of seeing.

John Schott — Untitled (Route 66 Motels) (1973)

Visual Analysis:

A plain photo of a roadside motel with neon signs, empty parking lots, and no people.

The image feels calm, flat, and emotionless, with clear light and simple composition.

Conceptual Meaning:

Shows how humans shape the landscape — motels, roads, and signs replace nature.

Reflects American travel, consumerism, and decline along Route 66.

The neutral, distant style invites viewers to notice quiet traces of human life and the passage of time.

Why It’s Relevant:

Part of the New Topographics movement — photographers who showed everyday, built environments instead of idealized nature.

Marks the shift from romantic landscapes to critical observation of modern America.

In Short:

Schott’s photo turns an ordinary motel into a quiet study of how people change the land — simple, emotionless, and deeply reflective of postwar America.

Robert Frank, Trolley, New Orleans, 1955

Visual Analysis:

Frank photographs a streetcar filled with passengers, each framed separately in rectangular windows.

The composition immediately shows racial segregation — white passengers sit in the front, Black passengers in the back.

The metal bars and window frames create visual barriers, making each person appear isolated, boxed into their own space.

The reflections on the glass and the shadows across the trolley add layers of distance and complexity, as if we’re looking through multiple screens.

The passengers’ faces are serious, still, and disconnected, with no visible interaction.

The contrast of light and dark — bright faces in front, darker tones in the back — mirrors the racial and social divide of 1950s America.

Conceptual Meaning:

This image reveals America’s divisions through everyday life.

The windows act as both a literal and symbolic barrier, showing how segregation is not only legal but emotional — people share space but remain separated by race, class, and circumstance.

Frank’s framing turns the trolley into a metaphor for society: everyone moves in the same direction but in different worlds.

The photograph’s stillness makes the separation feel ordinary and systemic, exposing how normalized inequality had become.

In Short:

Trolley, New Orleans (1955) visualizes America divided — each window a frame of isolation, every face separated by invisible and visible barriers.

Through repetition and structure, Frank transforms an ordinary street scene into a portrait of a fractured democracy, revealing that America’s symbols of progress (cars, flags, movement) often conceal its deepest inequalities.

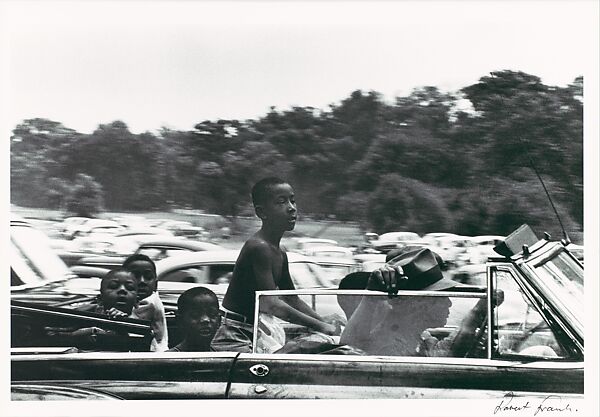

Robert Frank — Belle Isle, Detroit (1955)

Visual Analysis:

Frank captures a group of Black children in a convertible car, surrounded by a crowded parking lot under the summer sun.

The boy at the center, shirtless and standing tall, becomes the photo’s main focus — his expression mixes curiosity and awareness, as if caught between innocence and experience.

The car moves slightly out of frame, giving the image a feeling of motion and impermanence.

The photograph’s loose framing and blur make it feel spontaneous and alive, as if capturing a fleeting moment of freedom and observation.

Conceptual Meaning:

Frank explores race, class, and identity in postwar America.

Although the children appear joyful and carefree, the image also carries a quiet tension — a sense of being looked at and being looked through.

This ties to Frank’s recurring theme of “looking and being looked at”, questioning who gets seen in America and how.

The photo suggests a moment of voyeurism and humanity, showing the beauty and fragility of everyday life within a divided country.

It reveals how small, ordinary scenes can reflect larger social realities about inclusion and exclusion.

Links to Gillian Rose’s site of the image itself — the photograph draws attention to its own construction and mediation.

Symbolizes the emerging modern condition: everyone is both watcher and watched.

In Short:

Frank turns an ordinary day at the park into a powerful image of observation and presence. The photo reflects both freedom and distance, showing how everyday life can still carry the weight of social division and visibility. Spontaneous framing and motion reflect postwar America’s restlessness and racial tension

The New York Times “100,000 Faces” Project and the Image as Witness

The New York Times “100,000 Faces” Project was created to mark the number of people in the United States who had died from COVID-19.

Each victim was represented by a small, individual portrait — forming one massive mosaic of faces that, together, visualized the scale of loss.

The project’s impact lies in how it transforms an abstract statistic into something deeply human.

However, it also raises complex questions about consent, representation, and how personal images are used in mass memorials.

The quote “An image can work as a witness to the world” means it shows proof of something that happened. It helps us see and remember real events that we might not have experienced ourselves. However, images also reflect bias and framing, so while they can reveal truth, they can also shape or limit how that truth is understood.

This applies directly here: each face bears witness to a life lived and lost, creating a collective testimony of grief and memory.

The project turns photography into evidence — not of violence or crime, but of human absence and societal failure to protect life.

Ethically, it challenges us to look, to acknowledge each person, rather than letting numbers erase individuality.

While it risks overwhelming viewers or reducing tragedy to spectacle, it largely succeeds in its goal — reminding the world that behind every number is a face, and behind every face, a story.

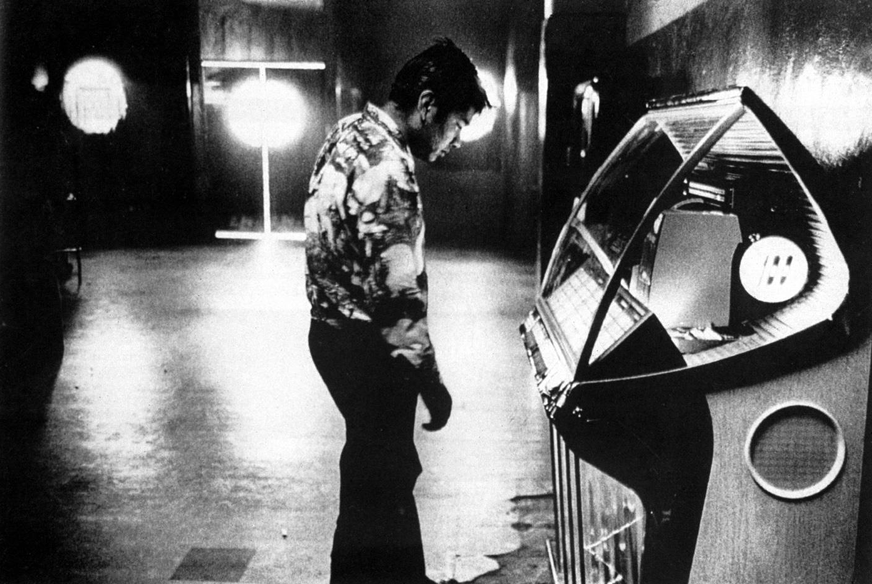

Robert Frank, Bar, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1955

Visual Analysis:

Frank captures a dimly lit bar interior where figures sit alone and disconnected, surrounded by reflections, mirrors, and neon lights.

The image feels fragmented and moody, with blurred edges and a tilted composition that give it a sense of movement and instability.

The lighting is low, creating deep shadows that suggest both intimacy and emptiness.

The bar — a symbol of leisure and escape — becomes a space of isolation and detachment.

The reflections and glass surfaces distort the scene, making it hard to tell what’s real or imagined, emphasizing Frank’s theme of alienation beneath American glamour.

In Short:

Frank turns a typical American bar into a portrait of loneliness and disconnection. His use of blur, shadow, and reflection transforms a social space into a quiet study of emotional isolation in postwar America.

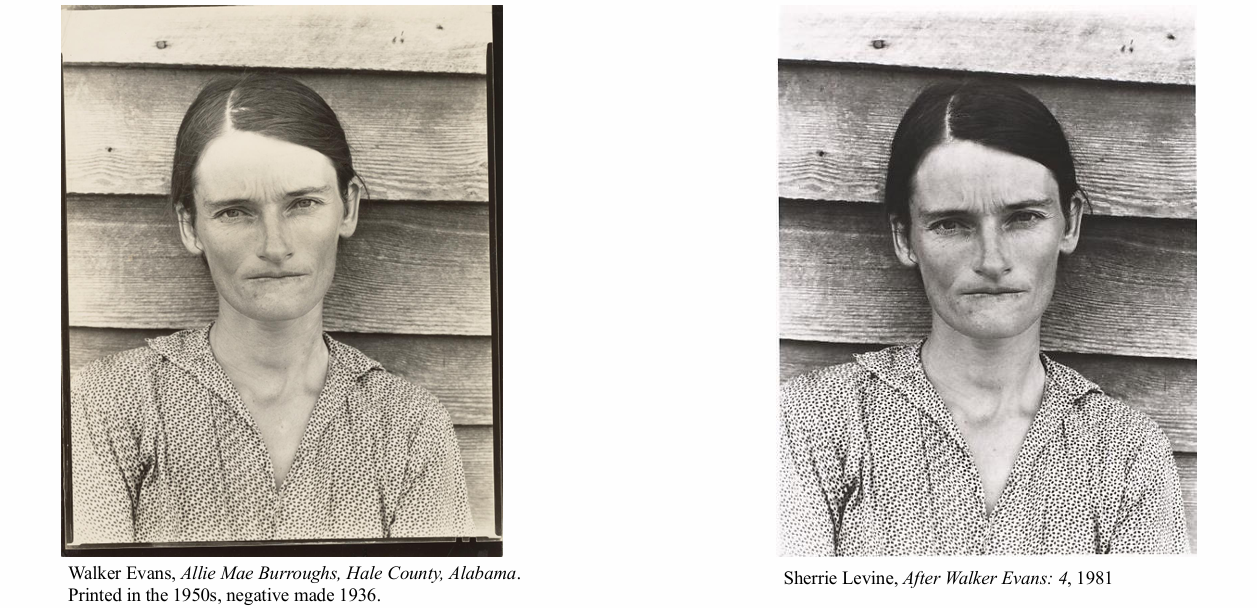

Theme: Appropriation & Referentiality

Definition: Borrowing or reusing existing images to question originality, authorship, and meaning.

Examples:

Sherrie Levine — After Walker Evans (1981)

Re-photographed Evans’ Allie Mae Burroughs to ask, what makes an image “original”?

→ Critiques how photography copies reality and challenges ideas of authorship.

Richard Prince — Untitled (Cowboy) (1989)

Re-photographed a Marlboro ad to expose how media sells masculinity and identity.

→ Turns ads into fine art, showing how culture reuses images.

Why It’s Impactful:

It makes viewers question who owns images and how media shapes what we see.

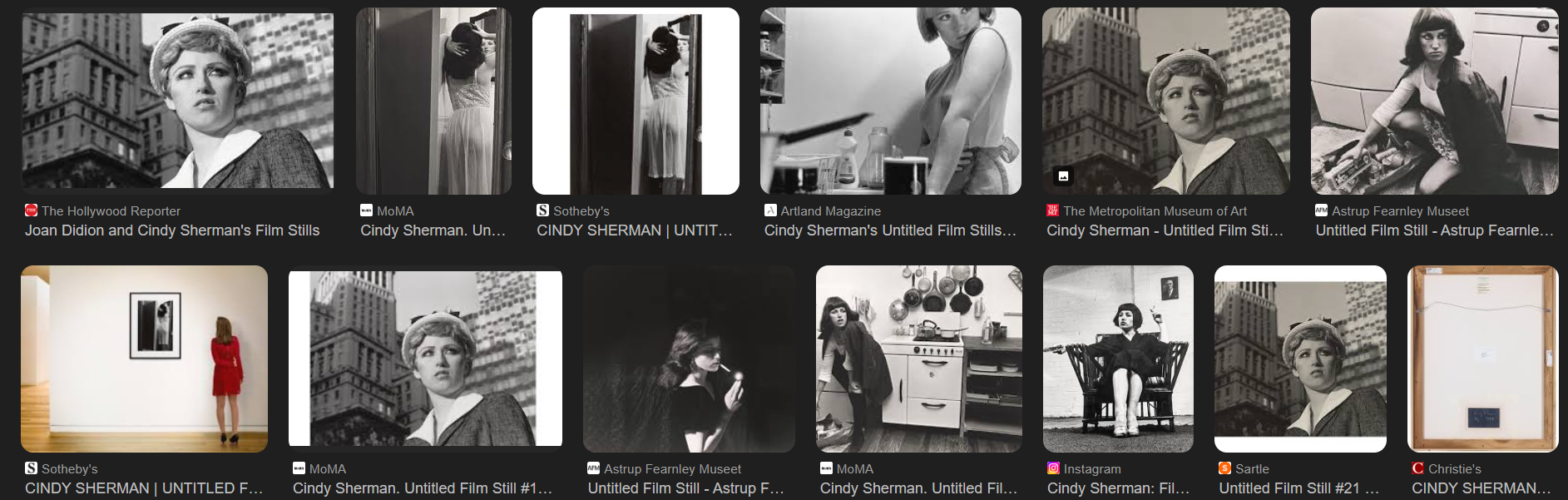

Theme: Representation & Self-Representation

Definition: Using photography to explore how identity (especially gender) is shown or performed.

Examples:

Cindy Sherman — Untitled Film Stills (1978–81)

Photographs herself as female stereotypes — the housewife, starlet, or “girl next door.”

→ Critiques how women are portrayed in media and film.

Lucas Samaras — Photo-Transformation (1973)

Manipulates Polaroids of himself to explore shifting identity and the performance of self.

Why It’s Impactful:

Shows that identity is constructed, not natural — and photography can reveal or distort it.

Theme: Voyeurism, Surveillance, & The Gaze

Definition:

Explores the power dynamics of looking — who gets to look, who is being looked at, and how images shape control, desire, and vulnerability.

Photography here becomes a way to question privacy, consent, and power in visual culture.

Key Ideas:

The act of looking is never neutral — it can reveal dominance, curiosity, or care.

Examines the tension between seeing and being seen, often exposing uncomfortable truths about surveillance and control.

Links to the male gaze and feminist theory — how women or subjects are objectified through images.

Artists blur the line between observation and intrusion, asking: When does looking become watching?

Uses the camera as both a tool of curiosity and a symbol of power.

Examples:

📸 Sophie Calle — Suite Vénitienne (1980s)

Secretly followed a man through Venice, photographing him like a detective.

Blends voyeurism, obsession, and narrative, turning her gaze into an art performance.

Raises ethical questions: Who controls the story — the watcher or the watched?

🏙 Shizuka Yokomizo — Strangers (1998–2000)

Left letters for random people asking them to stand by their windows while she photographed them from the street.

Creates a strange mix of distance and intimacy, control and consent.

The strangers are aware of being watched — turning surveillance into collaboration.

Why It’s Impactful:

Reveals how photography can expose power and vulnerability in everyday life.

Turns private moments into public images, making us question ethics, intimacy, and visibility.

Challenges the viewer to think about their own gaze — how we look at others and what that means.

Transforms surveillance from something passive into an active, shared experience.

In Short:

This theme shows that looking is never innocent — it’s about power, curiosity, and control.

Artists use voyeurism and surveillance to make us aware of how we see and how we’re seen.

Theme: Performance, Communication, & Collaboration

Definition:

When photography captures or becomes part of a performance, interaction, or collaboration between the artist and others.

The photograph is not just a record — it’s evidence of an action, a moment of communication, or a shared experience.

Key Ideas:

Focuses on the body, gesture, and presence — how people express identity or emotion through action.

Turns everyday interactions (care, conversation, protest, play) into meaningful artistic acts.

The camera becomes a tool for connection instead of just observation.

Blurs roles — the artist, subject, and viewer all participate in creating meaning.

Often explores themes of communication, intimacy, vulnerability, and community.

Examples:

🫓 Tatsumi Orimoto — Bread Man Series (1990s–2000s)

Performed in public with bread tied to his face, later included his mother in Art Mama.

Called it “communication art” — focused on care, aging, and human relationships.

His photos document acts of love and connection rather than static art objects.

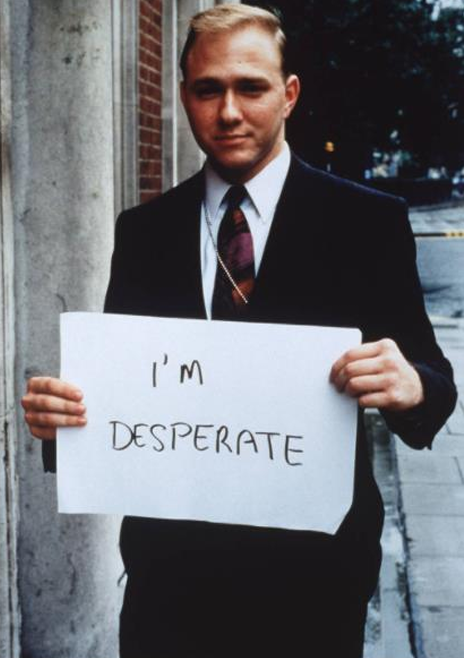

🪧 Gillian Wearing — Signs That Say What You Want Them To Say (1992–93)

Collaborated with strangers holding handwritten signs revealing their private thoughts.

Explores honesty, vulnerability, and self-expression in public.

Breaks the wall between photographer and subject — both share power in creating meaning.

Why It’s Impactful:

Expands photography from documentation to social interaction.

Challenges traditional roles of artist and viewer — art becomes participatory.

Encourages empathy and reflection by revealing the humanity behind each performance.

Transforms everyday life into art, showing that communication itself can be creative and political.

In Short:

This theme shows how photography can be an act of performance and connection — turning real human encounters into art that speaks about care, identity, and shared experience.

Theme: Public vs. Private Tension

Definition: Examining how we present ourselves publicly vs. who we are privately.

Examples:

Gillian Wearing — Signs Series

Exposes how external appearance hides inner truth — “I’m desperate,” “I have been certified as mildly insane.”

→ Uses collaboration and text to reveal hidden emotions and social pressure.

Ken Lum — Melly Shum Hates Her Job (1990)

Combines portraits and text to critique modern work life and how people interact with public images.

Why It’s Impactful:

Shows how photography reveals or hides personal identity — connects to social vulnerability and exposure.

Theme: Questions about originality

Definition: Challenging the idea of a “unique” artwork and the rules of what photography should look like.

Examples:

The Pictures Generation (Levine, Sherman, Prince, Kruger)

Used appropriation and mass media images to blur originality.Garry Winogrand — The Animals (1963)

Played with spontaneous framing and repetition — not traditional beauty but tension and chaos.

Why It’s Impactful:

These projects broke modernist traditions and made photography about ideas instead of perfect composition.

Theme: Playing With / Disrupting Conventions

Definition:

Artists intentionally break traditional photographic rules — like focus, composition, and subject matter — to challenge what counts as a “good” photograph and how meaning is made.

Examples:

📸 Garry Winogrand — The Animals & Women Are Beautiful

Used spontaneous, tilted shots, often without asking permission.

Emphasized chance, movement, and chaos rather than careful framing.

His photos feel alive, awkward, and real — disrupting expectations of how photography “should look.”

📸 Cindy Sherman — Untitled Film Stills

Mimicked cinematic stereotypes but used herself as the model, breaking norms of authorship and representation.

Blurs the line between fiction and reality — acting as both subject and director.

Why It’s Impactful:

Turns photography into a critical tool, not just a recording device.

Challenges ideas of truth, beauty, and control in art.

Opens the door for photography to explore concepts, emotions, and identity rather than perfect technique

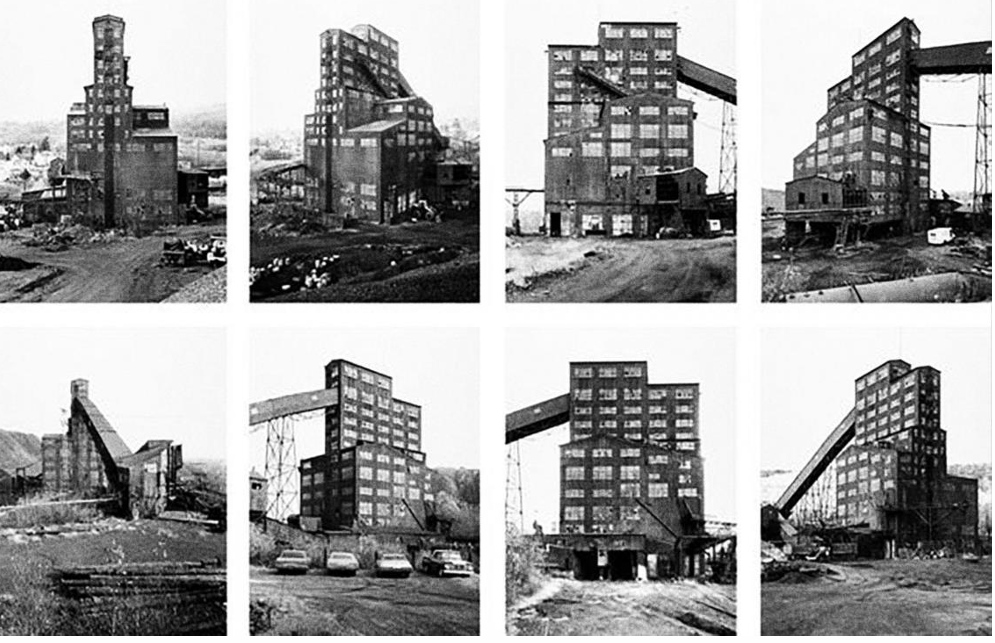

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Preparation Plant, Harry E. Colliery Coal Breaker, Wiles Barre,Pennsylvania, USA, 1974

Visual Analysis:

Grid of black-and-white photos showing the same industrial building from different angles.

Neutral light, no people, and consistent framing create a systematic, objective look.

The structure appears both functional and sculptural — like an industrial monument.

Conceptual Meaning:

The Bechers treated factories and mining sites as “anonymous sculptures”, revealing beauty in industrial form.

Their repetitive, typological approach removes emotion and focuses on classification and structure.

Reflects postwar interest in objectivity and documentation — influenced by conceptual art and minimalism.

Suggests how industry shaped landscapes and communities, even as these buildings became obsolete.

In Short:

The Bechers turn decaying industrial sites into precise visual studies — transforming everyday factories into quiet works of art and memory.

How does semiotics help us analyze images or cultural signs in visual culture?

Semiotics is the study of signs and symbols and how they create meaning.

In visual culture, it helps us break down how images communicate ideas.

Every image is like a collection of signs, where each element like colors, objects, even the way people are arranged, acts as a "signifier" that points to a certain "signified," which is the concept or idea behind it.

It helps you understand that images aren’t just pretty pictures; they’re actually conveying cultural meanings.

For example, if you see a photo of a red rose, the rose is a signifier and it might signify love or romance in our culture.

By using semiotics, you’re basically decoding how cultural meanings are built into images and how we interpret them.