Chapter 6 - Coding with streams

1/42

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

43 Terms

Buffering vs Streaming - How buffering works with data

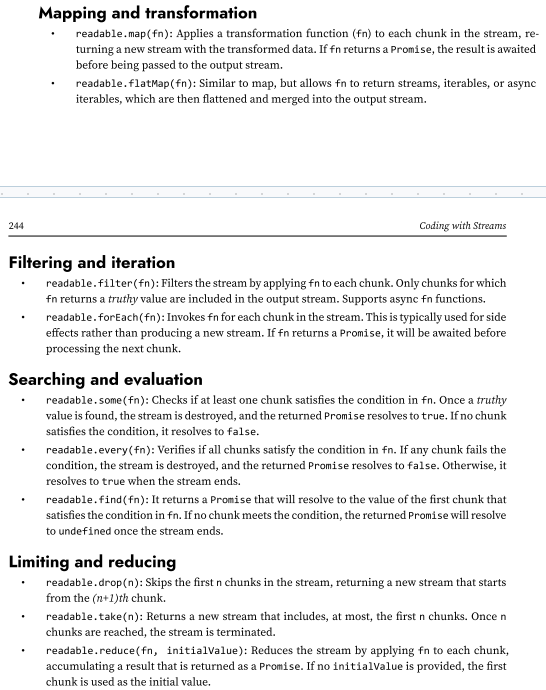

Almost all the asynchronous APIs that we've seen so far in this book work using buffer mode. For an input operation, buffer mode causes all the data coming from a resource to be collected into a buffer until the operation is completed; it is then passed back to the caller as one single blob of data.

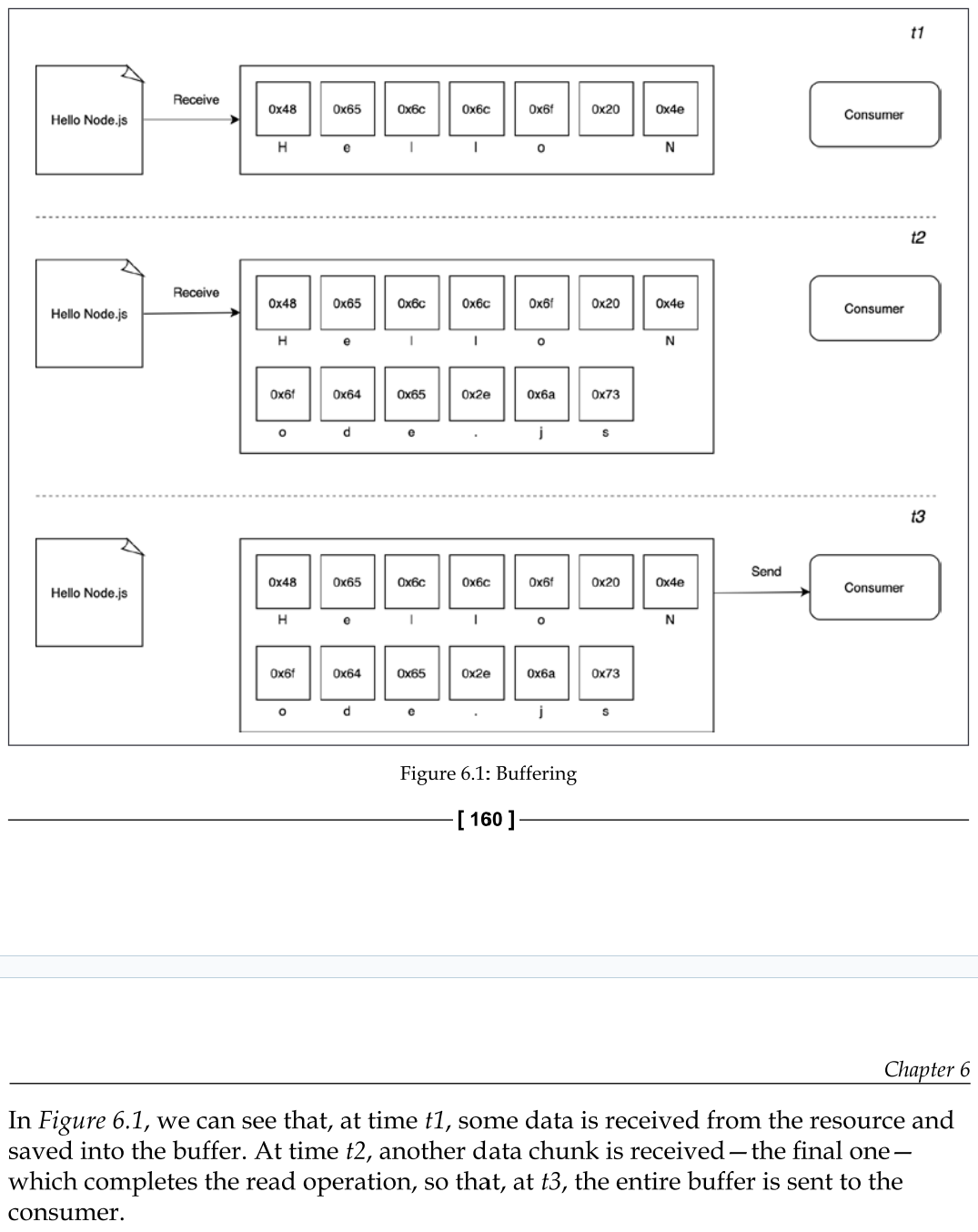

Buffering vs Streaming - How Streaming works with data

streams allow us to process the data as soon as it arrives from the resource.

what are the differences between these two approaches? Purely from an efficiency perspective, streams can be more efficient in terms of both space (memory usage) and time (computation clock time).

Node.js streams have another important advantage: composability.

Spatial efficiency (Difference between streams and buffers)

first of all, streams allow us to do things that would not be possible by buffering data and processing it all at once. For example, consider the case in which we have to read a very big file, let's say, in the order of hundreds of megabytes or even gigabytes. Clearly, using an API that returns a big buffer when the file is completely read is not a good idea. Imagine reading a few of these big files concurrently; our application would easily run out of memory. Besides that, buffers in V8 are limited in size. You cannot allocate more than a few gigabytes of data, so we may hit a wall way before running out of physical memory.

Example - Gzipping using a buffered API

Exampe - Gzipping using streams

Time efficiency (how buffers and streams differ at time efficiency)

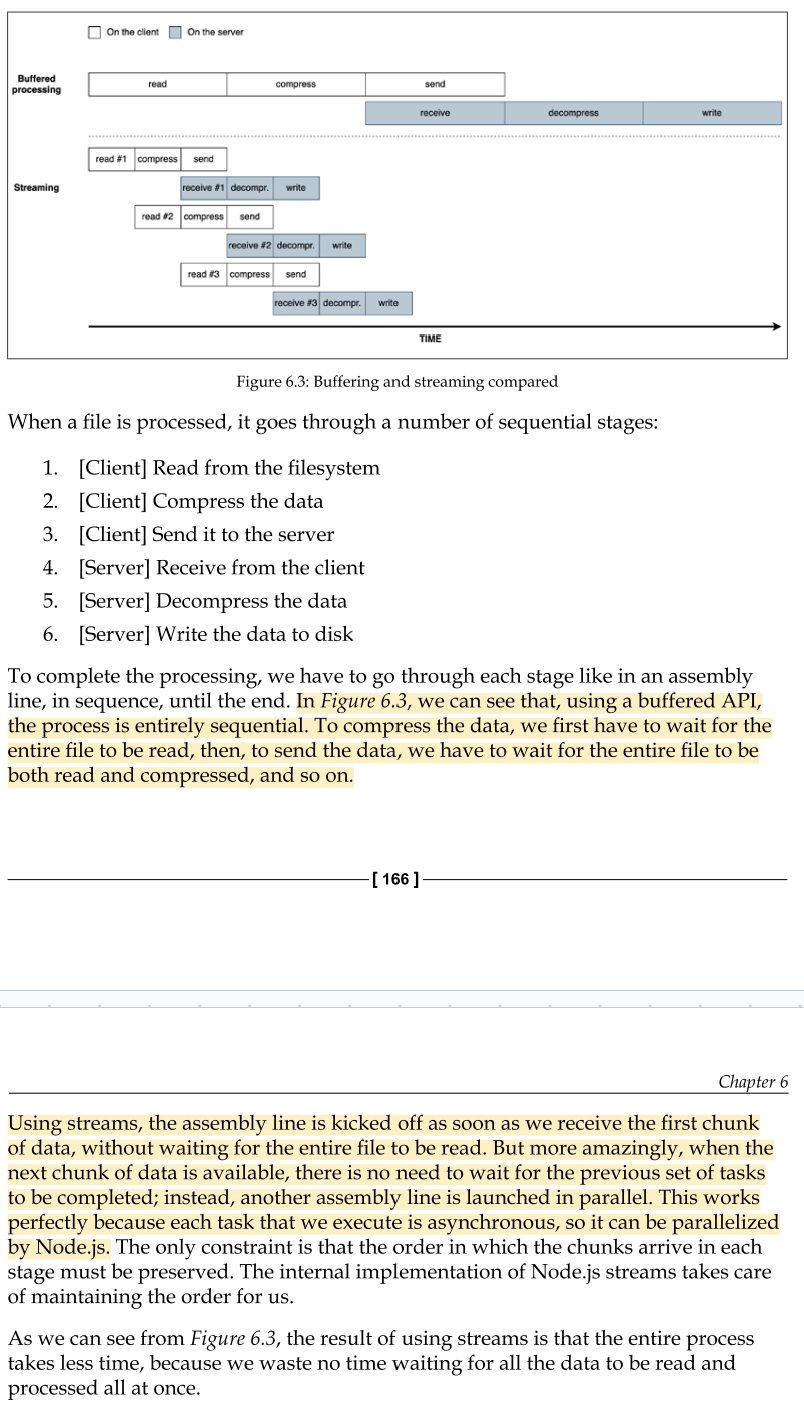

Let's now consider the case of an application that compresses a file and uploads it to a remote HTTP server, which, in turn, decompresses it and saves it on the filesystem:

If the client component of our application was implemented using a buffered API, the upload would start only when the entire file had been read and compressed. On the other hand, the decompression would start on the server only when all the data had been received.

A better solution to achieve the same result involves the use of streams. On the client machine, streams allow us to compress and send the data chunks as soon as they are read from the filesystem, whereas on the server, they allow us to decompress every chunk as soon as it is received from the remote peer. (check img)

(for better detailed example: 193-196)

Composability with Pipes

the pipe() method, which allows us to connect the different processing units, each being responsible for one single functionality.

In perfect Node.js style. This is possible because streams have a uniform interface, and they can understand each other in terms of API.

The only prerequisite is that the next stream in the pipeline has to support the data type produced by the previous stream, which can be either binary, text, or even objects.

(for an example in depth: 196-199)

Anatomy of streams

Every stream in Node.js is an implementation of one of the four base abstract classes available in the stream core module:

Readable

Writable

Duplex

Transform

Each stream class is also an instance of EventEmitter. Streams, in fact, can produce several types of event, such as end when a Readable stream has finished reading, finish when a Writable stream has completed writing, or error when something goes wrong.

Operating modes

One reason why streams are so flexible is the fact that they can handle not just binary data, but almost any JavaScript value. In fact, they support two operating modes:

Binary mode: To stream data in the form of chunks, such as buffers or strings.

Object mode: To stream data as a sequence of discrete objects (allowing us to use almost any JavaScript value).

These two operating modes allow us to use streams not just for I/O, but also as a tool to elegantly compose processing units in a functional fashion.

Readable streams

A Readable stream represents a source of data. In Node.js, it's implemented using the Readable abstract class, which is available in the stream module.

There are two approaches to receive the data from a Readable stream: non-flowing (or paused) and flowing.

Readable - The non-flowing mode

The non-flowing or paused mode is the default pattern for reading from a Readable stream. It involves attaching a listener to the stream for the readable event, which signals the availability of new data to read.

Then, in a loop, we read the data continuously until the internal buffer is emptied. This can be done using the read() method, which synchronously reads from the internal buffer and returns a Buffer object representing the chunk of data.

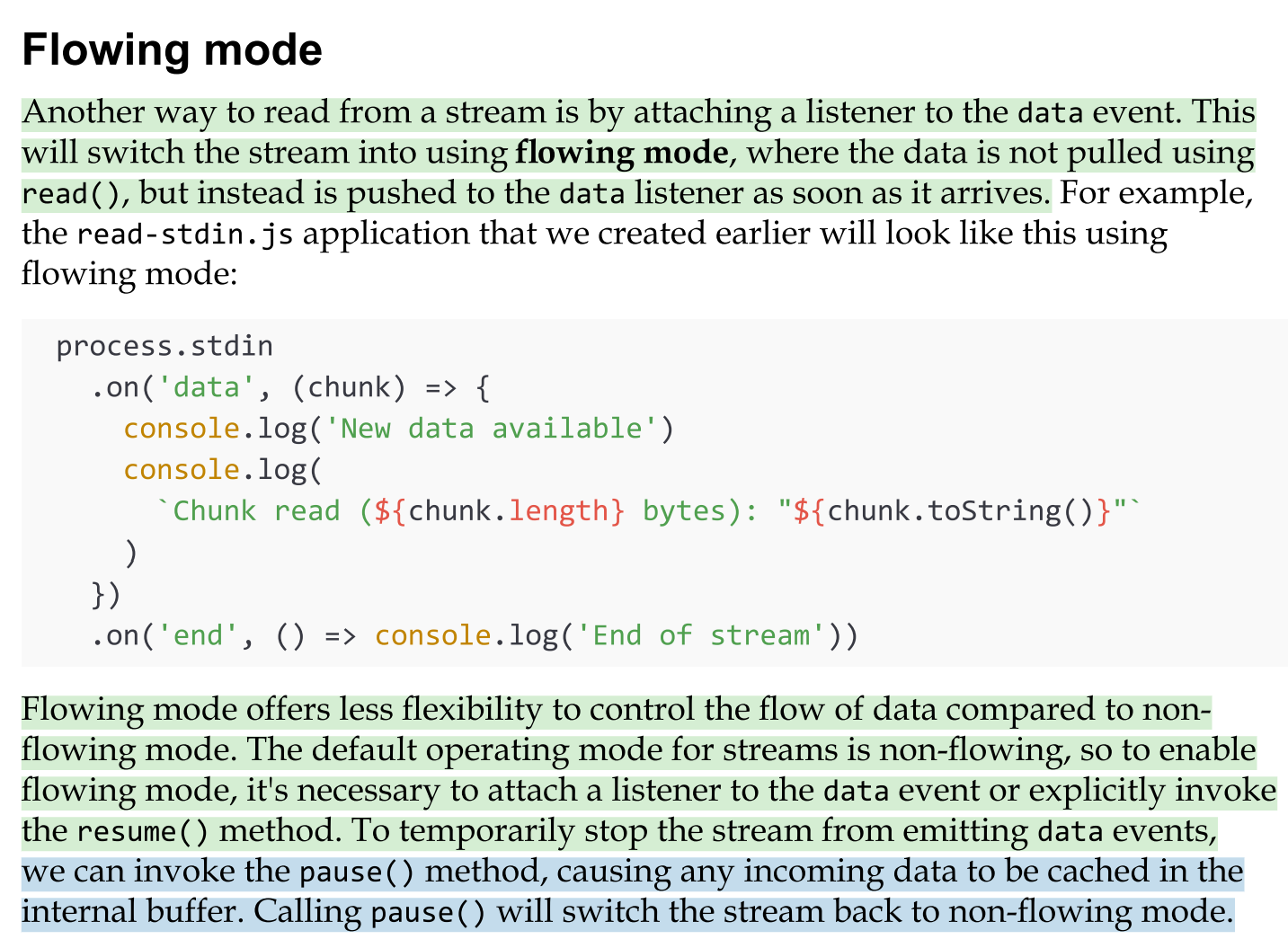

Readable - Flowing mode

Another way to read from a stream is by attaching a listener to the data event. This will switch the stream into using flowing mode, where the data is not pulled using read(), but instead is pushed to the data listener as soon as it arrives.

Flowing mode offers less flexibility to control the flow of data compared to non- flowing mode. The default operating mode for streams is non-flowing, so to enable flowing mode, it's necessary to attach a listener to the data event or explicitly invoke the resume() method. To temporarily stop the stream from emitting data events,

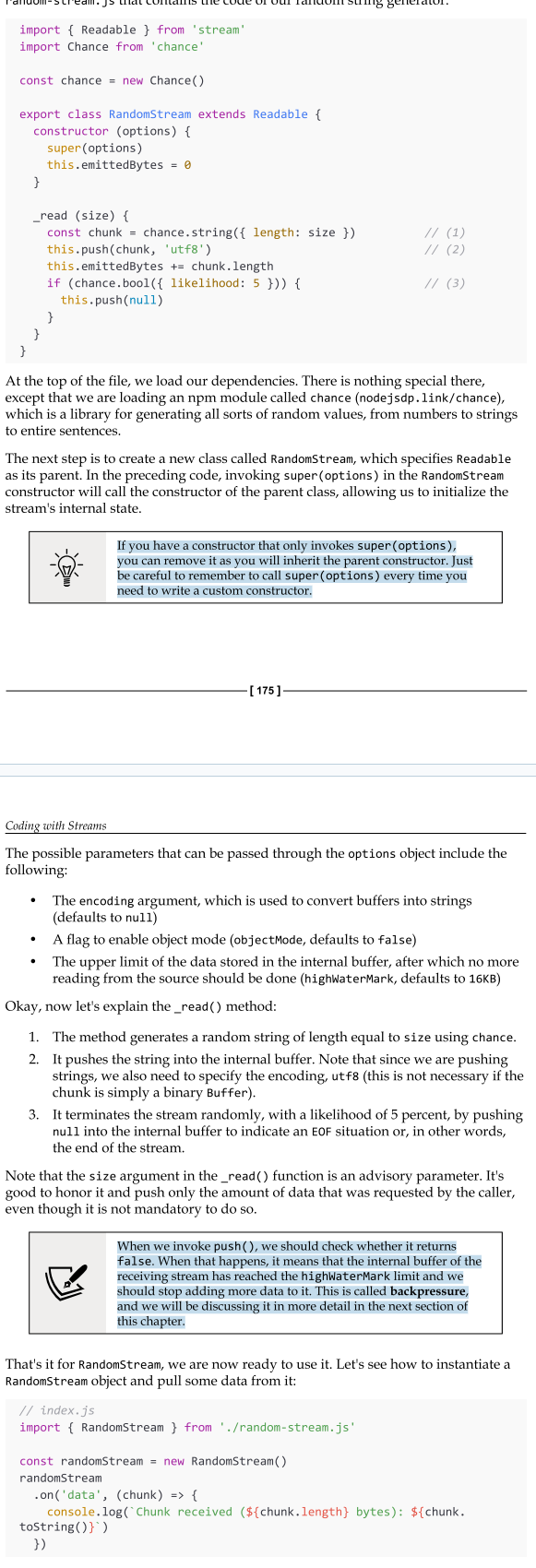

Implementing Readable streams

Now that we know how to read from a stream, the next step is to learn how to implement a new custom Readable stream. To do this, it's necessary to create a new class by inheriting the prototype Readable from the stream module. The concrete stream must provide an implementation of the _read() method.

Please note that read() is a method called by the stream consumers, while _read() is a method to be implemented by a stream subclass and should never be called directly. The underscore usually indicates that the method is not public and should not be called directly.

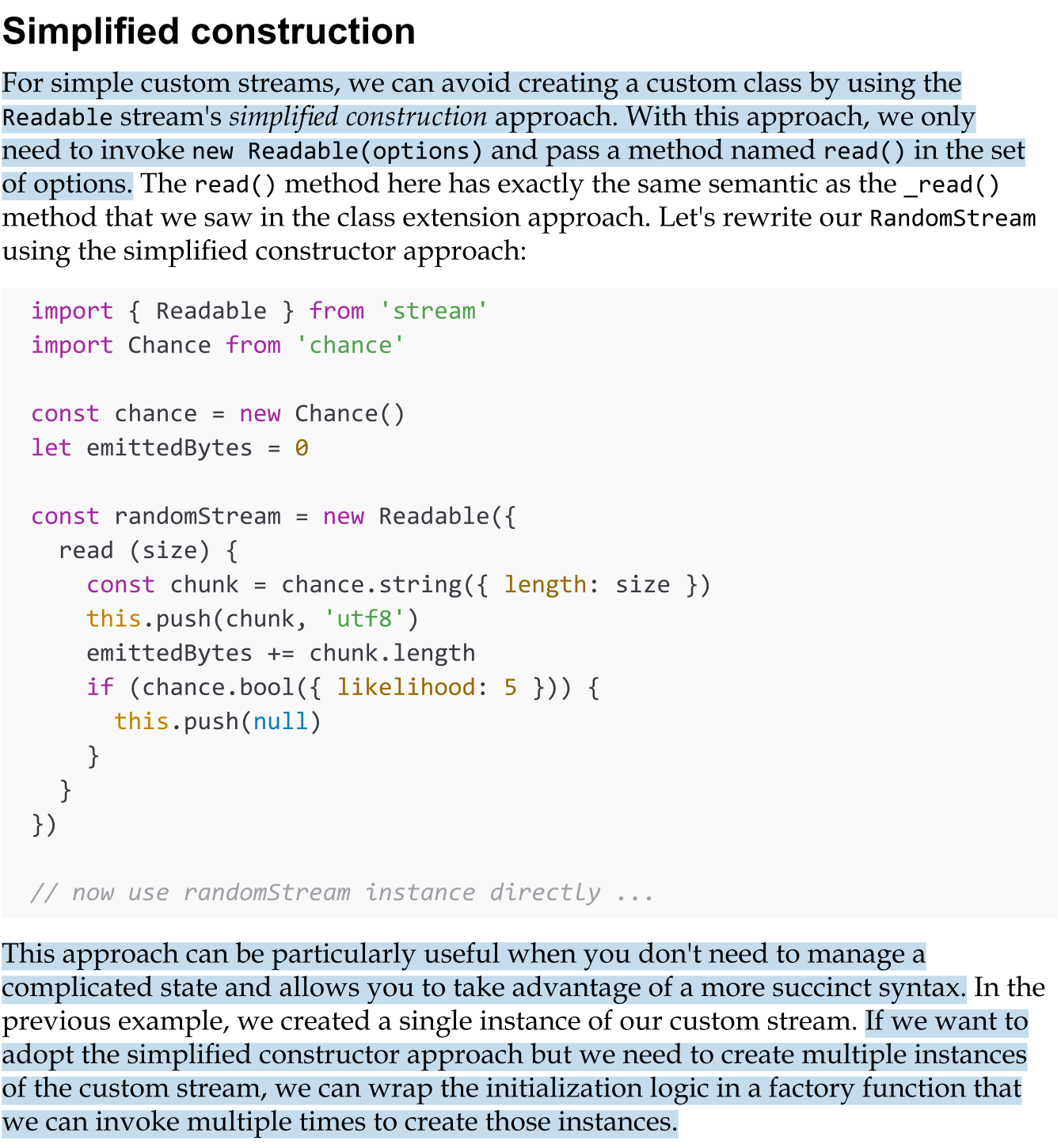

Simplified construction (of creating a custom readable stream)

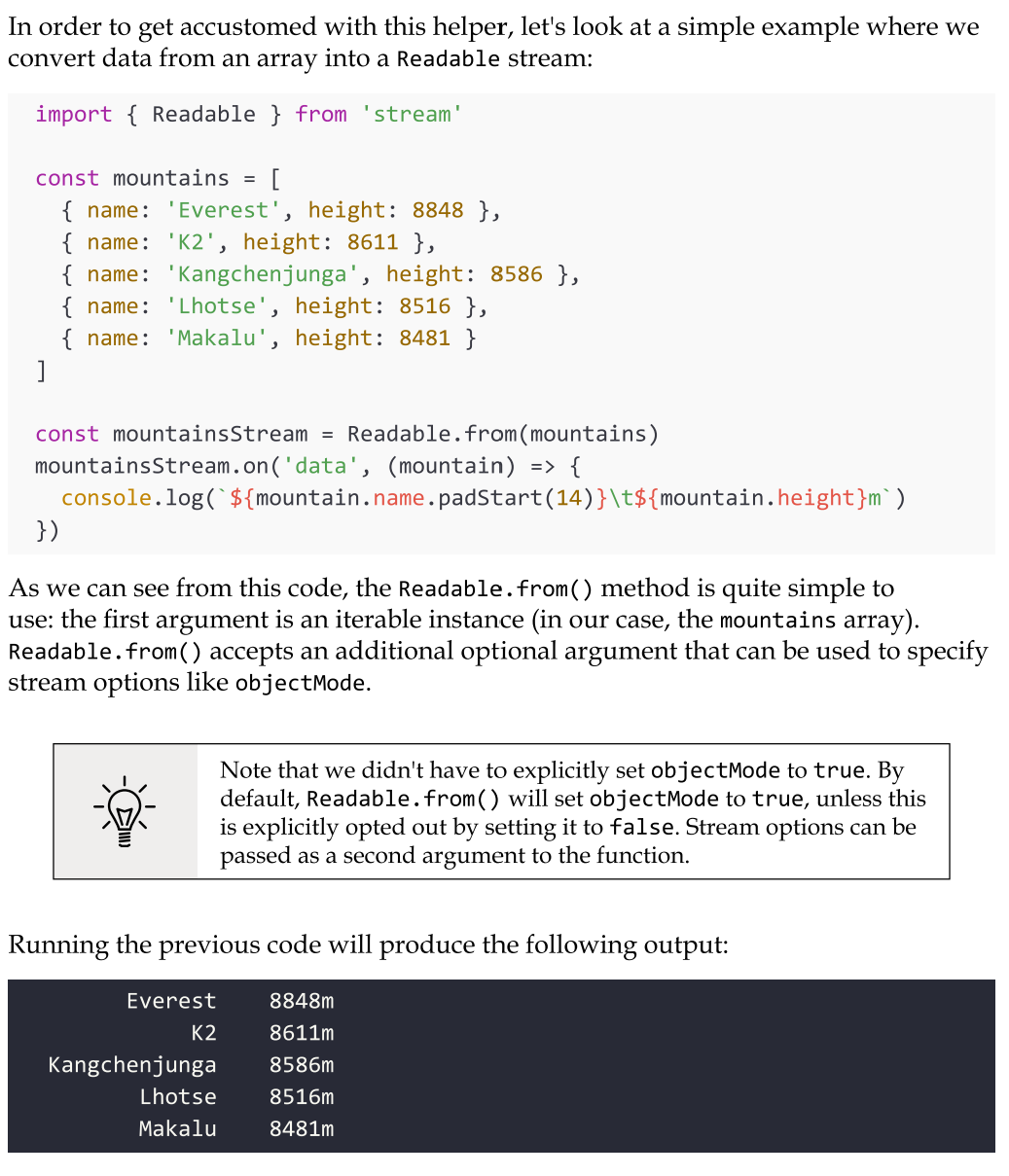

Readable streams from iterables

You can easily create Readable stream instances from arrays or other iterable objects (that is, generators, iterators, and async iterators) using the Readable.from() helper.

Try not to instantiate large arrays in memory. Imagine if, in the previous example, we wanted to list all the mountains in the world. There are about 1 million mountains, so if we were to load all of them in an array upfront, we would allocate a quite significant amount of memory. Even if we then consume the data in the array through a Readable stream, all the data has already been preloaded, so we are effectively voiding the memory efficiency of streams. It's always preferable to load and consume the data in chunks, and you could do so by using native streams such as fs.createReadStream, by building a custom stream, or by using Readable.from with lazy iterables such as generators, iterators, or async iterators.

Writable streams

A Writable stream represents a data destination. Imagine, for instance, a file on the filesystem, a database table, a socket, the standard output, or the standard error interface. In Node.js, these kinds of abstractions can be implemented using the Writable abstract class, which is available in the stream module

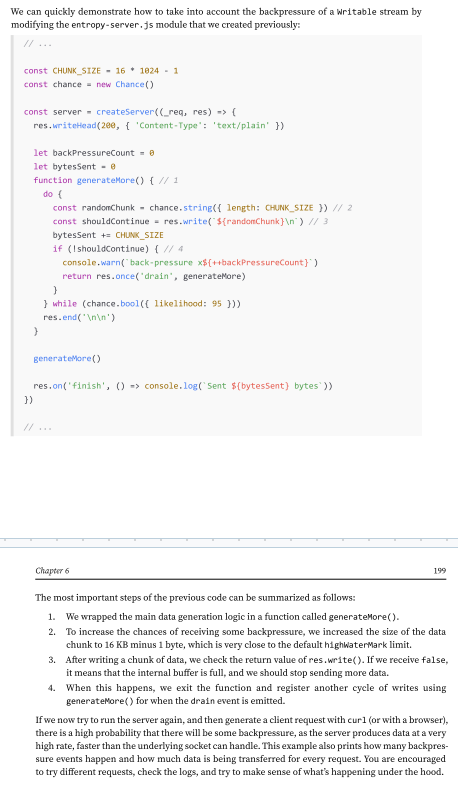

Backpreassure

Node.js data streams, like liquids in a piping system, can suffer from bottlenecks when data is written faster than the stream can handle. To manage this, incoming data is buffered in memory.

However, without feedback from the stream to the writer, the buffer could keep growing, potentially leading to excessive memory usage.

Node.js streams are designed to maintain steady and predictable memory usage, even during large data transfers. Writable streams include a built-in signaling mechanism to alert the application when the internal buffer has accumulated too much data.

This signal indicates that it’s better to pause and wait for the buffered data to be flushed to the stream’s destination before sending more data. The writable. write() method returns false once the buffer size exceeds the highWaterMark limit.

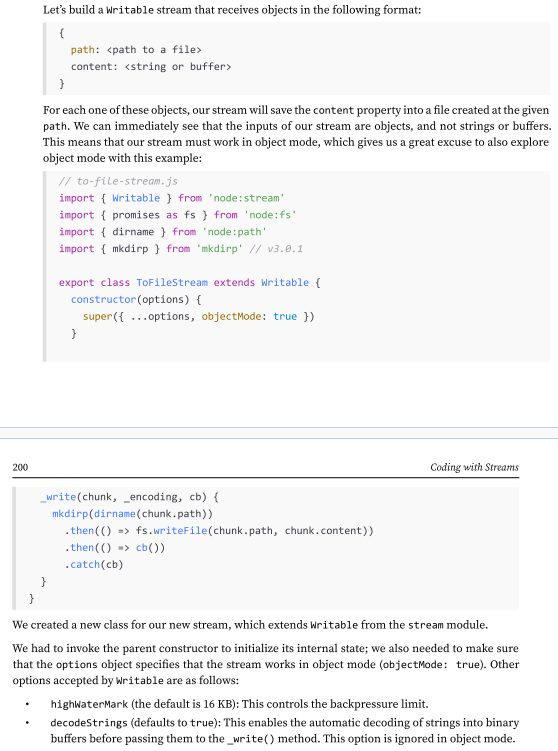

Implementing Writable streams

We can implement a new Writable stream by inheriting the class Writable and providing an implementation for the _write() method. Let’s try to do it immediately while discussing the details along the way.

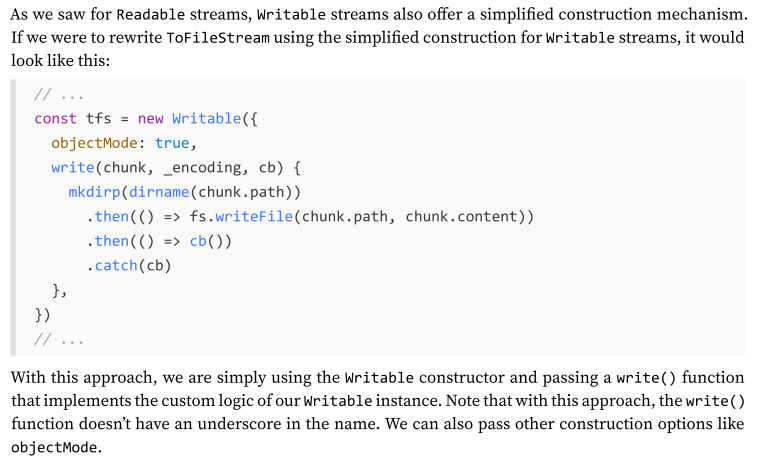

Simplified construction (of creating a custom writable stream)

As we saw for Readable streams, Writable streams also offer a simplified construction mechanism. If we were to rewrite ToFileStream using the simplified construction for Writable streams, it would look like this:

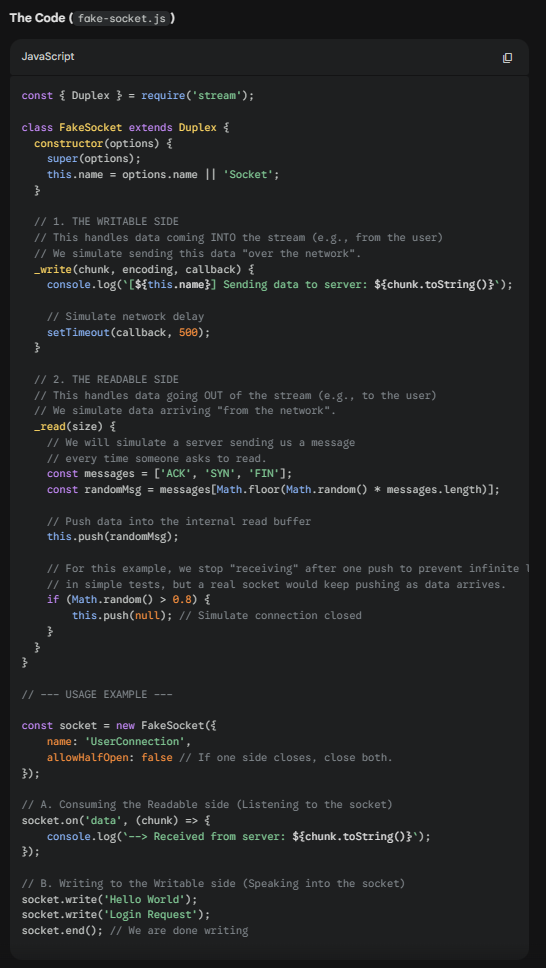

What is Duplex Streams

A Duplex stream is a stream that is both Readable and Writable. It is useful when we want to describe an entity that is both a data source and a data destination, such as network sockets, for example.

Duplex streams inherit the methods of both stream.Readable and stream.Writable, so this is nothing new to us. This means that we can read() or write() data, or listen for both readable and drain events.

To create a custom Duplex stream, we have to provide an implementation for both _read() and _write(). The options object passed to the Duplex() constructor is internally forwarded to both the Readable and Writable constructors.

what is a transform steams

Transform streams are a special kind of Duplex stream that are specifically designed to handle data transformations.

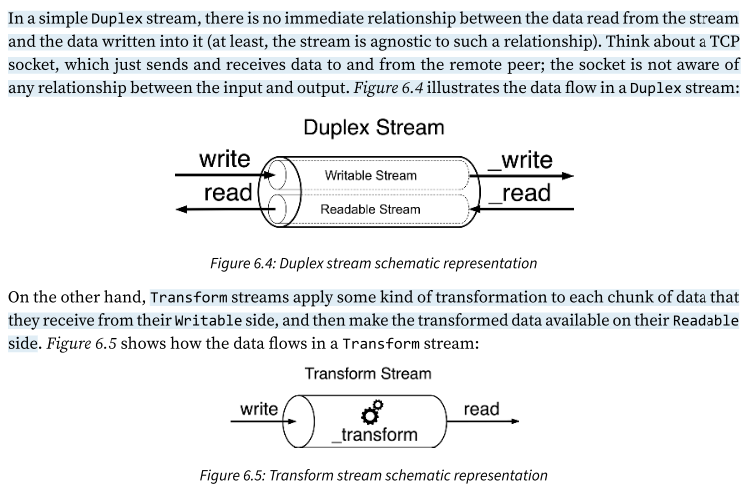

In a simple Duplex stream, there is no immediate relationship between the data read from the stream and the data written into it (at least, the stream is agnostic to such a relationship). Think about a TCP socket, which just sends and receives data to and from the remote peer; the socket is not aware of any relationship between the input and output. Figure 6.4 illustrates the data flow in a Duplex stream:

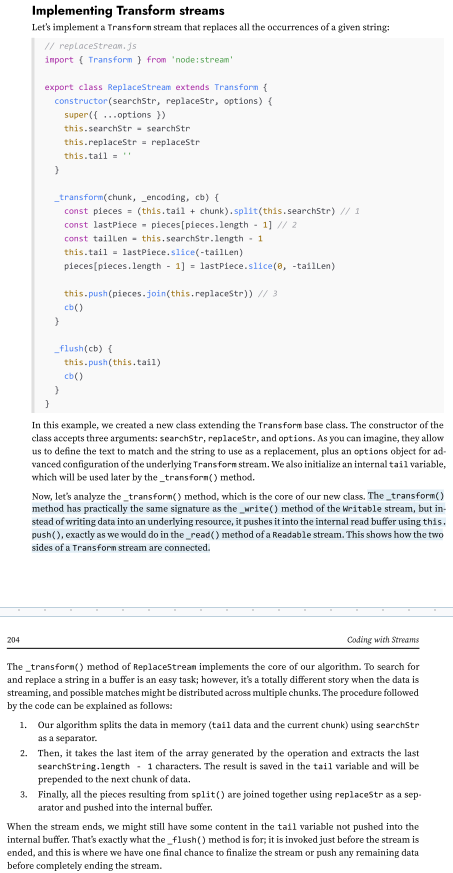

On the other hand, Transform streams apply some kind of transformation to each chunk of data that they receive from their Writable side, and then make the transformed data available on their Readable side. Figure 6.5

From a user perspective, the programmatic interface of a Transform stream is exactly like that of a Duplex stream. However, when we want to implement a new Duplex stream, we have to provide both the read() and write() methods, while for implementing a new Transform stream, we have to fill in another pair of methods: transform() and flush().

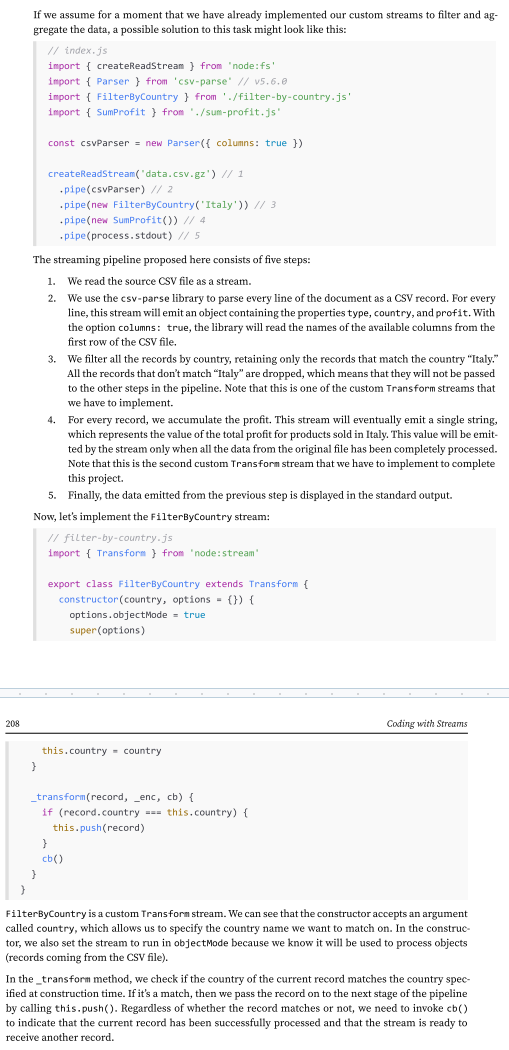

Implementing Transform streams

Streams process data in chunks, and these chunks don’t always align with the boundaries of the target search string. For example, if the string we are trying to match is split across two chunks, the split() operation on a chunk alone won’t detect it, potentially leaving part of the match unnoticed. The tail variable ensures that the last portion of a chunk—potentially part of a match—is preserved and concatenated with the next chunk.

In Transform streams, it’s not uncommon for the logic to involve buffering data from multiple chunks before there’s enough information to perform the transformation.

(139-242)

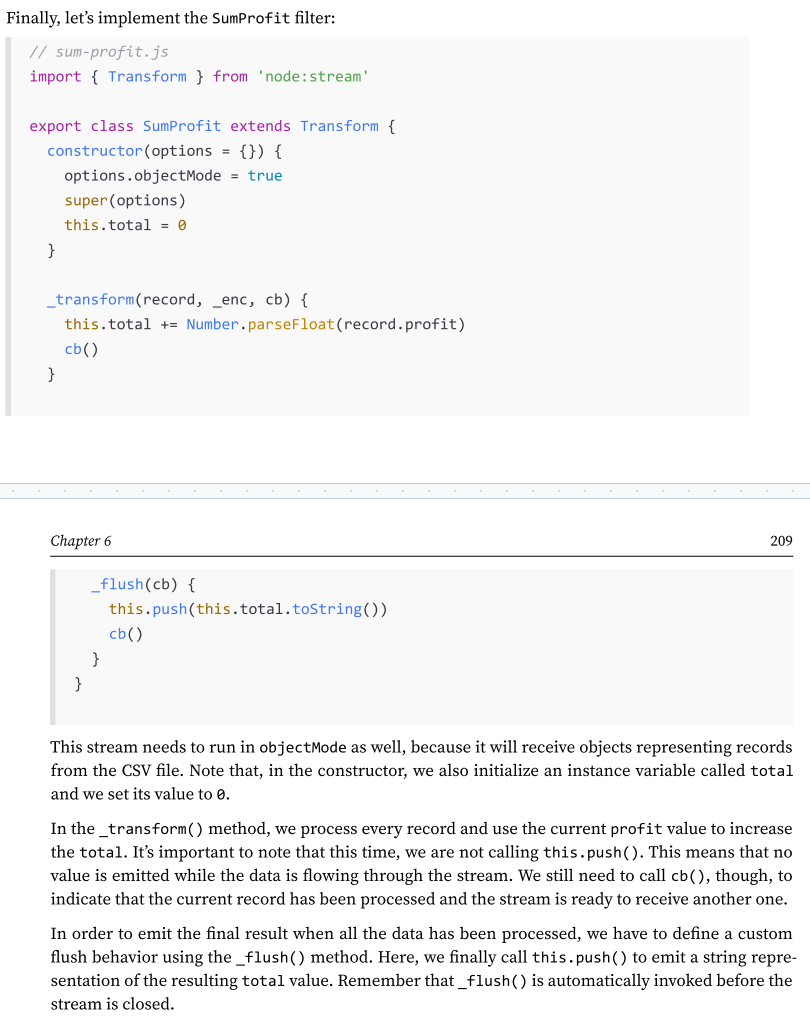

Filtering and aggregating data with Transform streams

As we discussed earlier, Transform streams are a great tool for building data transformation pipelines. But Transform streams aren’t limited to those examples. They’re often used for tasks like filtering and aggregating data.

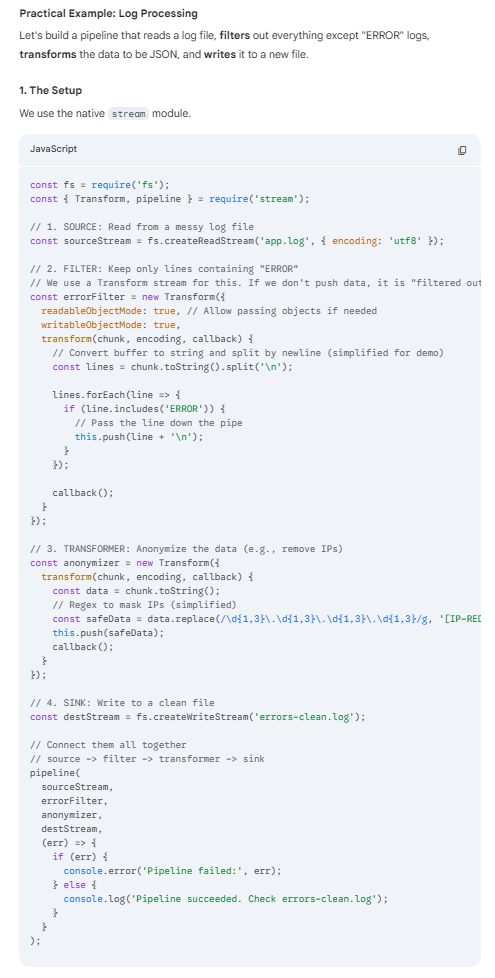

To make this more concrete, imagine a Fortune 500 company asks us to analyze a large file containing all their sales data for 2024. The file, data.csv, is a sales report in CSV format, and they want us to calculate the total profit for sales made in Italy.

Let’s use Node.js streams. Streams are well suited for this kind of task because they can process large datasets incrementally, without loading everything into memory.

Pattern: transform filter

Invoke this.push() in a conditional way to allow only some data to reach the next stage of the pipeline.

The Transformer Filter pattern (often called the Pipes and Filters pattern) is a software architectural pattern used to process streams of data. It breaks down complex processing tasks into a series of separate, independent steps.

In Node.js, this is most commonly and natively implemented using Streams.

The Core Concept

Imagine an assembly line. Raw material comes in, passes through several stations where it is modified or inspected, and a finished product comes out.

Source: The origin of the data (e.g., reading a file, an HTTP request).

Filter/Transformer: A component that receives data, performs a single operation (modifies it, filters it, or enriches it), and passes it to the next step.

Sink: The final destination (e.g., writing to a file, sending a response, saving to a DB).

Why use it in Node.js?

Memory Efficiency: You don't load the entire dataset into memory. You process it chunk by chunk.

Decoupling: Each filter does one thing well. You can easily add, remove, or reorder filters without breaking the whole system.

Backpressure: Node.js streams automatically handle "backpressure"—if the writing step is slow, the reading step automatically slows down so memory doesn't overflow.

Pattern: Streaming aggregation

Use _transform() to process the data and accumulate the partial result, then call this.push() only in the _flush() method to emit the result when all the data has been processed.

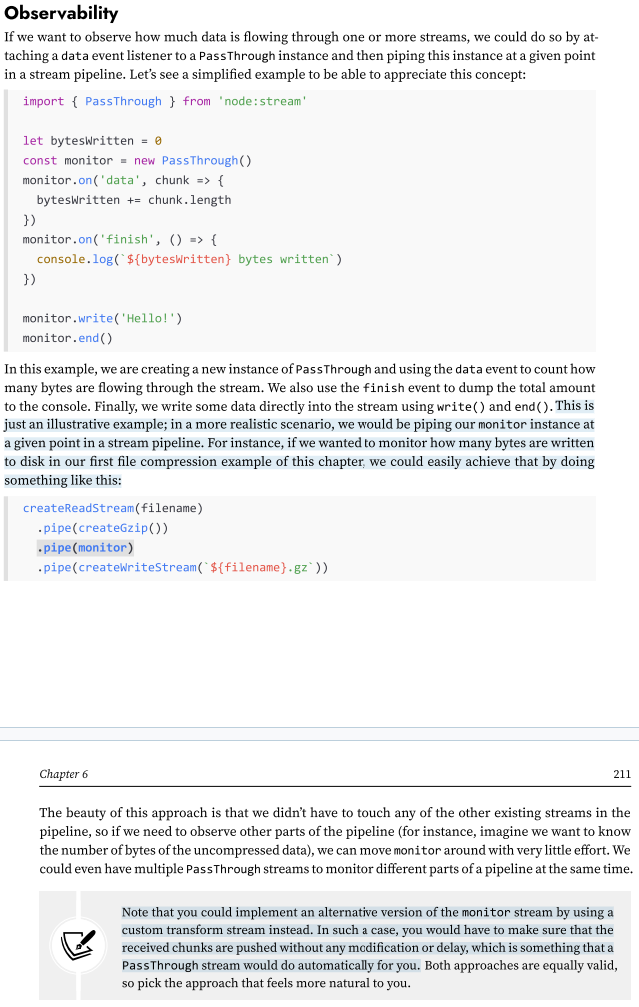

what is PassThrough streams?

There is a fifth type of stream that is worth mentioning: PassThrough. This type of stream is a special type of Transform stream that outputs every data chunk without applying any transformation.PassThrough is possibly the most underrated type of stream, but there are several circumstances in which it can be a very valuable tool in our toolbelt. For instance, PassThrough streams can be useful for observability or to implement late piping and lazy stream patterns.

Observability - How to observe how much data is flowing through one or more streams?

Note that you could implement an alternative version of the monitor stream by using a custom transform stream instead. In such a case, you would have to make sure that the received chunks are pushed without any modification or delay, which is something that a PassThrough stream would do automatically for you. Both approaches are equally valid, so pick the approach that feels more natural to you.

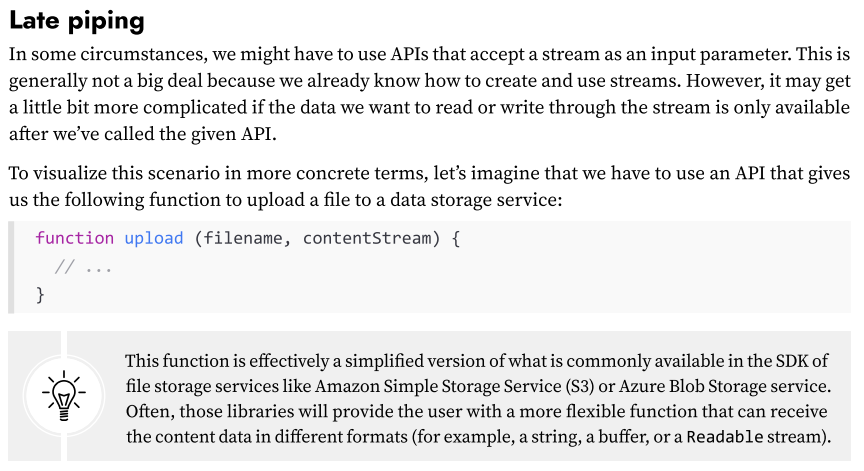

Pattern: Late piping

Definition: A pattern used when an API requires a stream input immediately, but the data source or necessary transformations (e.g., compression) are not yet ready or need to happen asynchronously.

(148-250)

Lazy streams

In more generic terms, creating a stream instance might initialize expensive operations straight away (for example, open a file or a socket, initialize a connection to a database, and so on), even before we start to use such a stream. This might not be desirable if you are creating a large number of stream instances for later consumption.

In these cases, you might want to delay the expensive initialization until you need to consume data from the stream.

Connecting streams using pipes - What does pipe() do for us under the hood?

Very intuitively, the pipe() method takes the data that is emitted from the readable stream and pumps it into the provided writable stream.

Also, the writable stream is ended automatically when the readable stream emits an end event (unless we specify {end: false} as options).

The pipe() method returns the writable stream passed in the first argument, allowing us to create chained invocations if such a stream is also Readable (such as a Duplex or Transform stream).

Piping two streams together - Suction

Piping two streams together will create suction, which allows the data to flow automatically to the writable stream, so there is no need to call read() or write(),

but most importantly, there is no need to control the backpressure anymore, because it’s automatically taken care of.

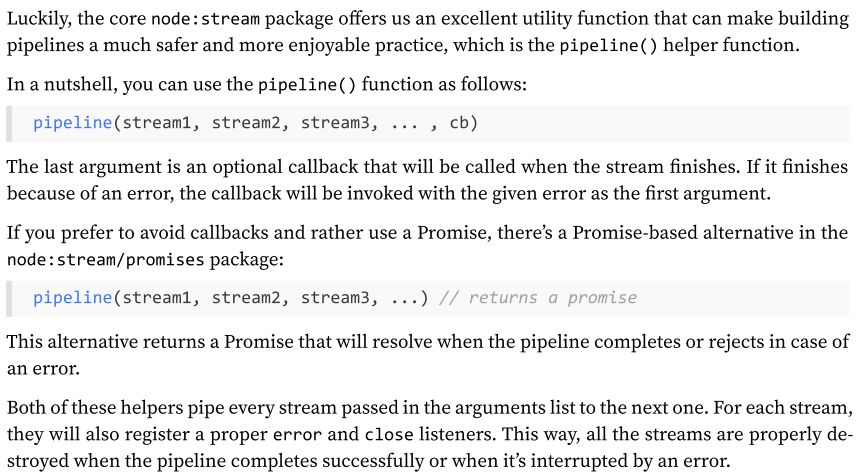

Pipe and error handling with pipeline()

Handling errors manually in a pipeline is not just cumbersome, but also error-prone—something we should avoid if we can!

Luckily, the core node:stream package offers us an excellent utility function that can make building pipelines a much safer and more enjoyable practice, which is the pipeline() helper function.

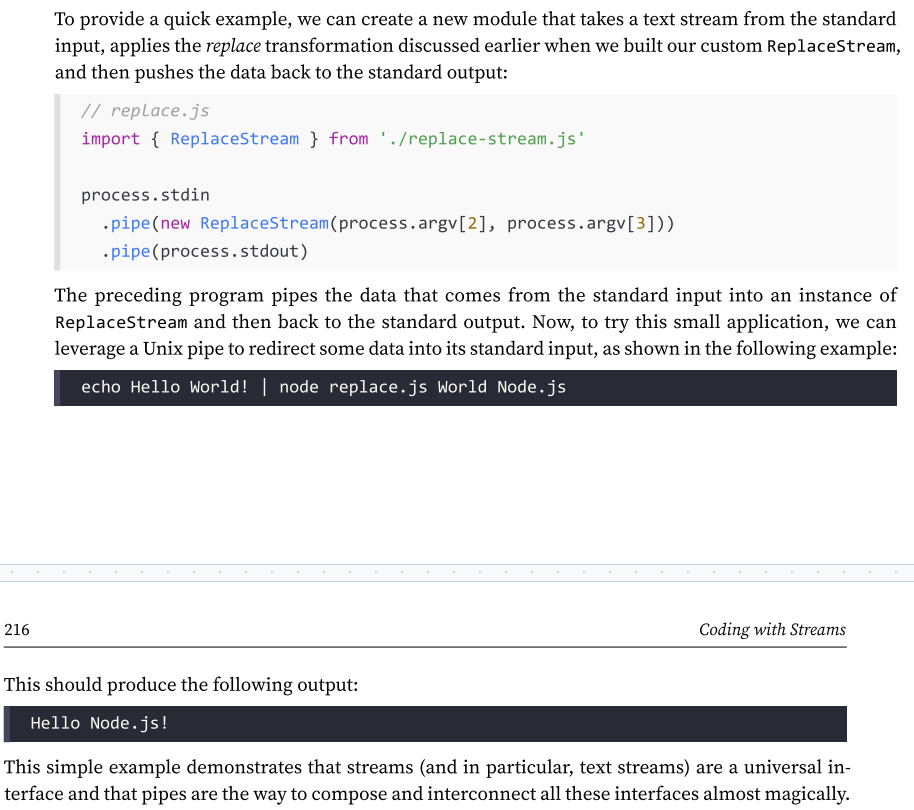

Asynchronous control flow patterns with streams

Going through the examples that we have presented so far, it should be clear that streams can be useful not only to handle I/O, but also as an elegant programming pattern that can be used to process any kind of data. But the advantages do not end at its simple appearance; streams can also be leveraged to turn “asynchronous control flow” into “flow control,” as we will see in this section.

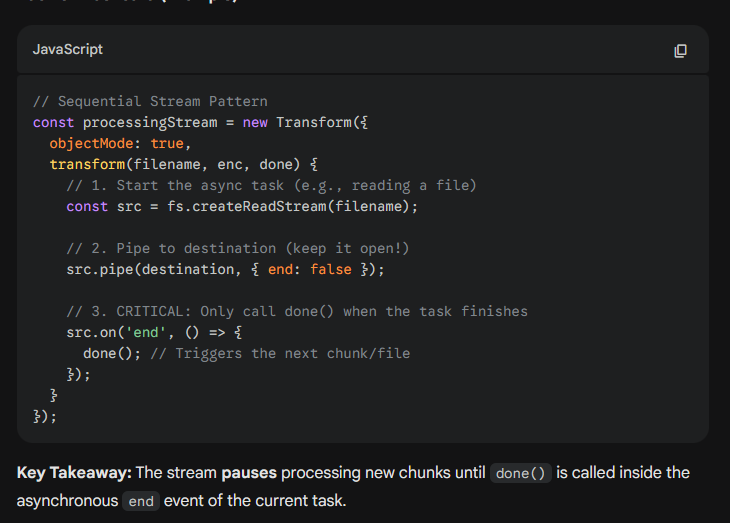

What’s Sequential Execution with Streams (or sometimes Stream-based Sequential Iteration).?

It is a specific Control Flow Pattern used in Node.js to replace traditional loops (like for...of with await) or utility libraries (like async.eachSeries).

Why it's a "Pattern": Instead of using a loop to manage the order of operations, you use the stream's internal buffer and callback mechanism to force tasks to line up single-file. The stream itself becomes the "queue" manager.

By default, streams will handle data in sequence. For example, the _transform() function of a Transform stream will never be invoked with the next chunk of data until the previous invocation completes by calling callback().

This is an important property of streams, crucial for processing each chunk in the right order, but it can also be exploited to turn streams into an elegant alternative to the traditional control flow patterns.

Unordered concurrent execution - Implementing an unordered concurrent stream

The Problem: Default sequential processing creates a bottleneck when handling slow asynchronous operations (underutilizes Node.js concurrency).

The Solution: Process multiple chunks in parallel instead of waiting for the previous one to complete.

Constraint: Only use this when order does not matter.

Best For: Object streams (e.g., processing independent database records).

Avoid For: Binary streams or any task where data chunks are related (e.g., file concatenation).

(Must read an example: 258-264)

Ordered concurrent execution

When processing data with concurrent streams, the order of output chunks may become shuffled. In cases where preserving the original order is essential, you can still process chunks concurrently as long as you reorder the results before emitting them.

The key is to separate concurrent internal processing (which can happen in any order) from ordered output emission (which may need to match the input sequence). This is typically achieved by buffering processed chunks and releasing them in the correct order.

Instead of implementing this logic manually, we recommend using the existing npm package parallel-transform, which handles this reordering for you.

Piping patterns

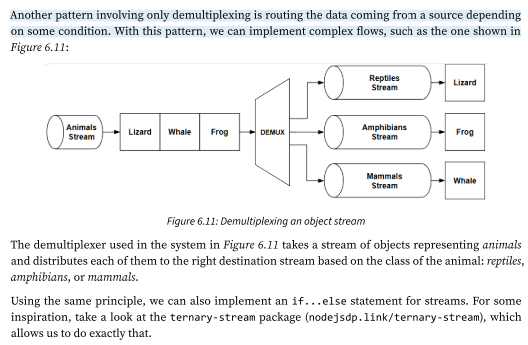

As in real-life plumbing, Node.js streams can also be piped together by following different patterns.

We can, in fact, merge the flow of two different streams into one, split the flow of one stream into two or more pipes, or redirect the flow based on a condition. In this section, we are going to explore the most important plumbing patterns that can be applied to Node.js streams.

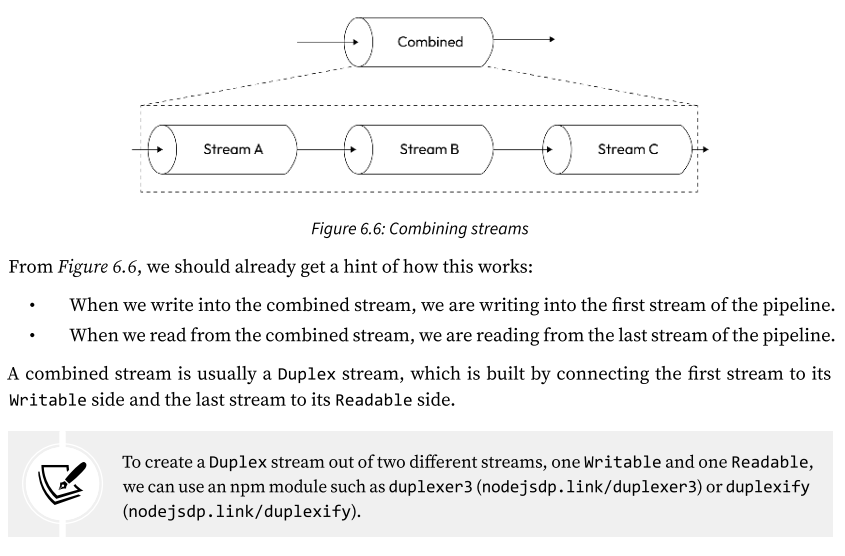

Pattern: Combining streams

what if we want to modularize and reuse an entire pipeline? What if we want to combine multiple streams so that they look like one from the outside (check Img):

A combined stream is usually a Duplex stream, which is built by connecting the first stream to its Writable side and the last stream to its Readable side.

Another important characteristic of a combined stream is that it must capture and propagate all the errors that are emitted from any stream inside the pipeline.

(for an exmaple: 268-270)

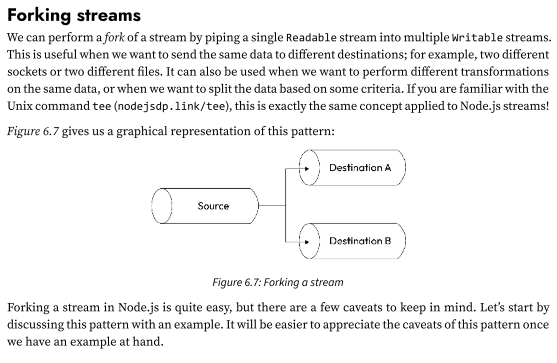

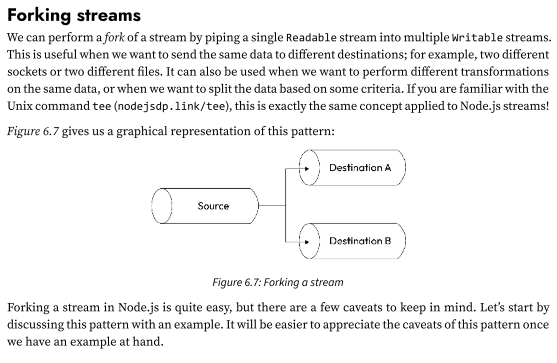

Pattern: Forking streams

We can perform a fork of a stream by piping a single Readable stream into multiple Writable streams.

This is useful when we want to send the same data to different destinations; for example, two different sockets or two different files. It can also be used when we want to perform different transformations on the same data, or when we want to split the data based on some criteria. If you are familiar with the Unix command tee (nodejsdp.link/tee), this is exactly the same concept applied to Node.js streams!

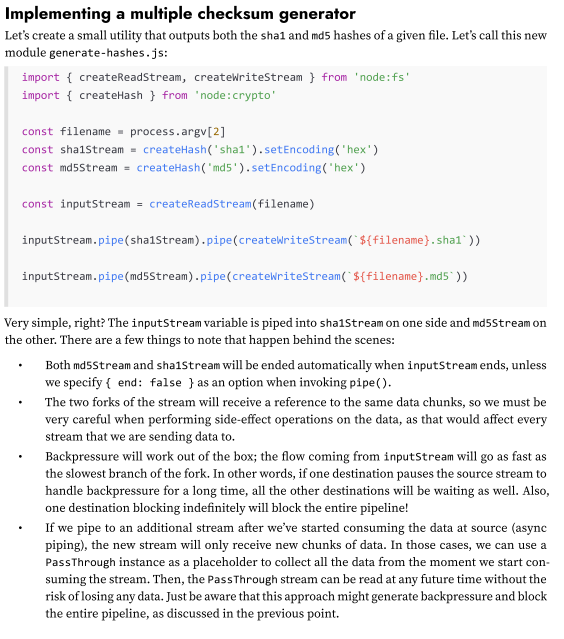

Pattern: Merging Streams

Merging is the opposite operation to forking and involves piping a set of Readable streams into a single Writable stream.

(for an implementation example: 272-274)

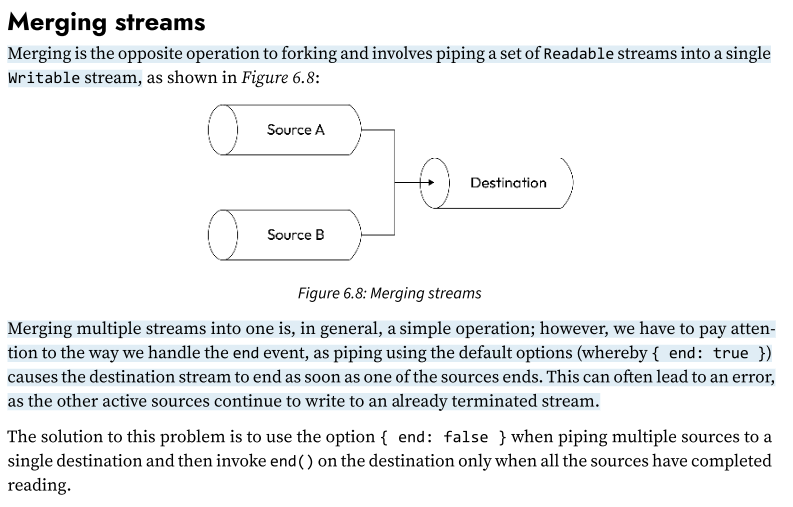

Pattern: Multiplexing and demultiplexing of merged streams (a binary/text stream)

There is a particular variation of the merge stream pattern in which we don’t really want to just join multiple streams together, but instead, use a shared channel to deliver the data of a set of streams.

This is a conceptually different operation because the source streams remain logically separated inside the shared channel, which allows us to split the stream again once the data reaches the other end of the shared channel.

The operation of combining multiple streams (in this case, also known as channels) to allow transmission over a single stream is called multiplexing,

while the opposite operation, namely reconstructing the original streams from the data received from a shared stream, is called demultiplexing.

The devices that perform these operations are called multiplexer (or mux) and demultiplexer (or demux), respectively.

(For an example: 175-279)

Pattern: Multiplexing and demultiplexing of merged streams (object streams.)

The example that we have just shown demonstrates how to multiplex and demultiplex a binary/text stream, but it’s worth mentioning that the same rules apply to object streams.

The biggest difference is that when using objects, we already have a way to transmit the data using atomic messages (the objects), so multiplexing would be as easy as setting a channelID property in each object. Demultiplexing would simply involve reading the channelID property and routing each object toward the right destination stream.

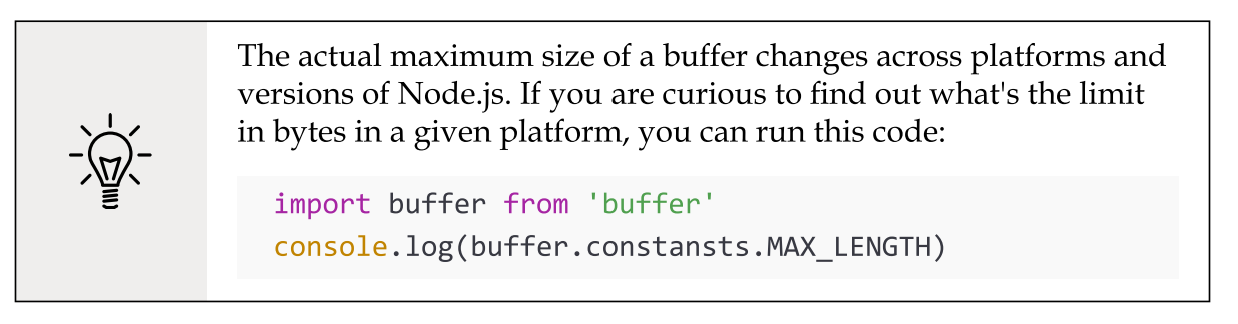

Readable stream utilities

In this chapter, we’ve explored how Node.js streams work, how to create custom streams, and how to compose them into efficient, elegant data processing pipelines.

some utilities provided by the node:stream module that simplify working with Readable streams. These utilities are designed to streamline data processing in a streaming fashion and bring a functional programming flavor to stream operations.

In the Stream module we have, Mapping, transformation, filtering, iteration, searching, evaluation, limiting and reducing utilities