Chemistry - All Schemes

1/102

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

103 Terms

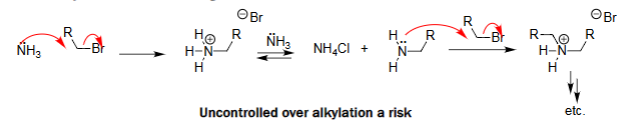

Direct Alkylation of Amines (R-Br)

Nucleophilic attack of NH₃ (or amine) on alkyl halide.

Yields ammonium salt intermediate.

Risk of over-alkylation → mixture of 1°, 2°, 3°, and quaternary ammonium salts.

Hard to control selectivity.

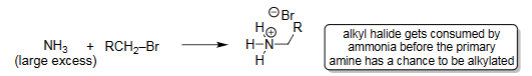

Alkylation Using Excess Ammonia (excess NH3)

Large excess NH₃ ensures it reacts before newly formed amines.

Minimizes over-alkylation.

Favors formation of primary amine.

Alkyl halide is essentially “quenched” by NH₃ first.

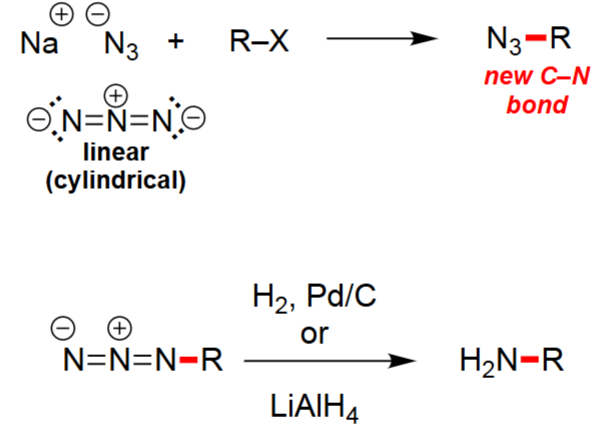

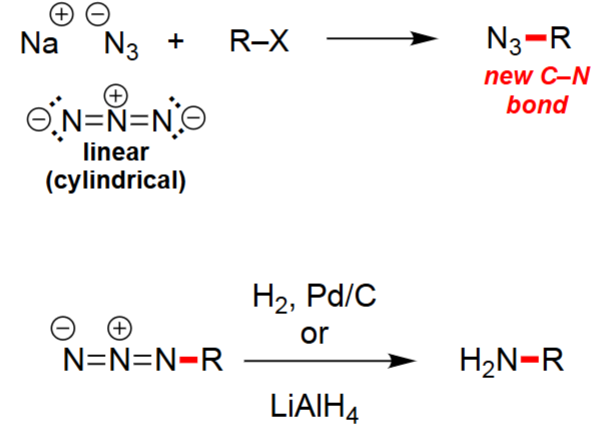

Azide Substitution (1. R–X, 2. H2,Pd/C)

Azide ion (N₃⁻) performs SN2 substitution on primary alkyl halides.

Forms an alkyl azide (R–N₃) with a new C–N bond.

Azide is linear and a strong nucleophile; good for avoiding elimination.

Useful as a synthetic equivalent of NH₂⁻ (but safer).

Azide Reduction to Amine (1. H₂/Pd–C or 2. LiAlH₄)

Converts R–N₃ → R–NH₂ via reduction.

H₂/Pd–C gives catalytic hydrogenation.

LiAlH₄ gives hydride reduction in anhydrous conditions.

No rearrangement occurs; preserves carbon skeleton.

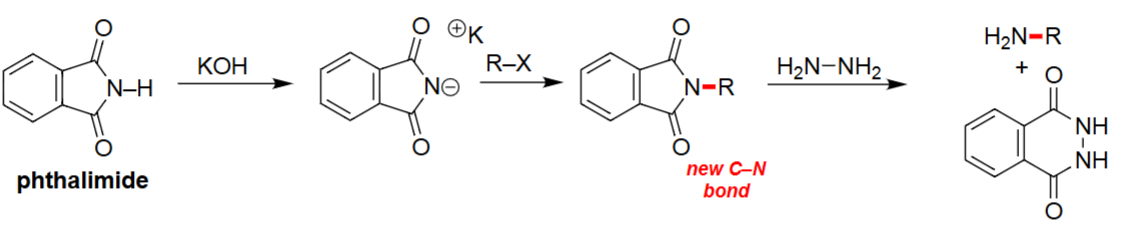

Gabriel Synthesis (1. KOH, 2. R–X, 3. H₂N–NH₂)

KOH deprotonates phthalimide to generate the nucleophilic imide anion.

The imide anion performs an SN2 attack on the alkyl halide, forming a new C–N bond.

Hydrazine cleaves the N–R bond, releasing the primary amine.

Produces primary amines without risk of over-alkylation.

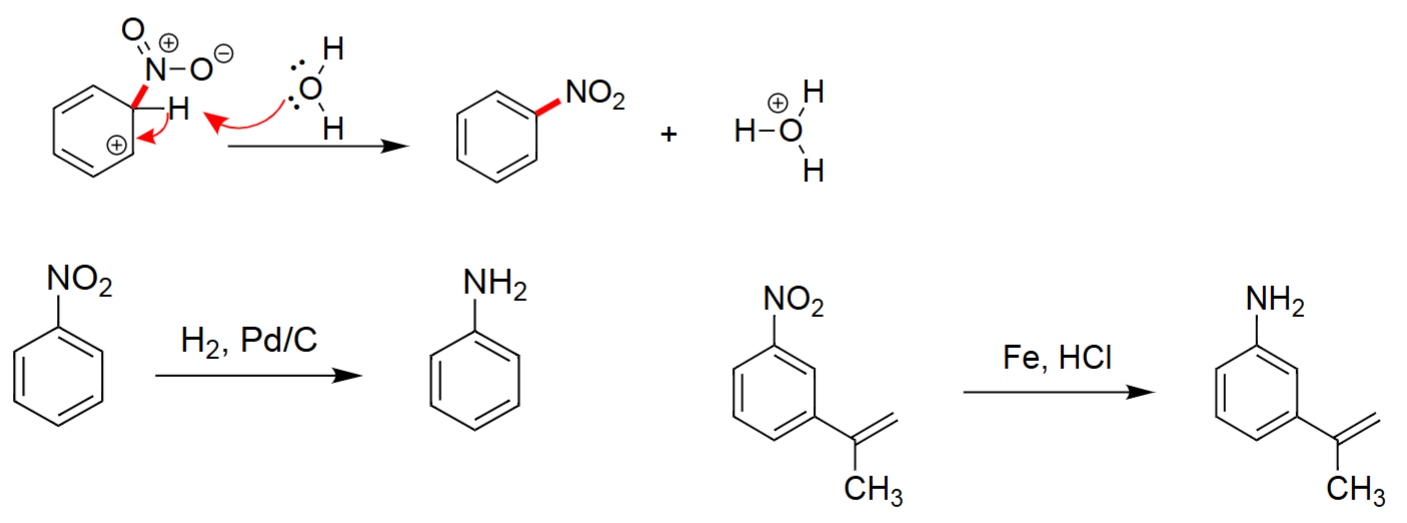

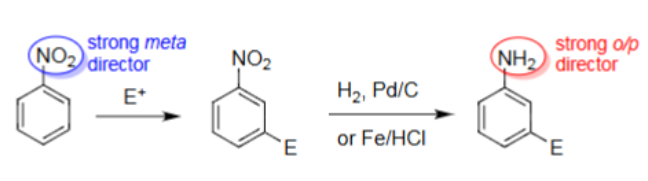

Deprotonation & Rearomatization (1. Base, 2. H₂/Pd–C or Fe/HCl)

Base removes a proton, restoring aromaticity and forming the nitro-substituted benzene.

The nitro group can then be reduced to an aniline using H₂, Pd/C.

Alternatively, Fe, HCl performs chemoselective reduction of the nitro group.

Produces primary aryl amines from nitroarenes.

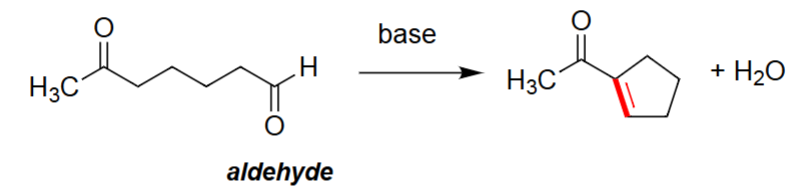

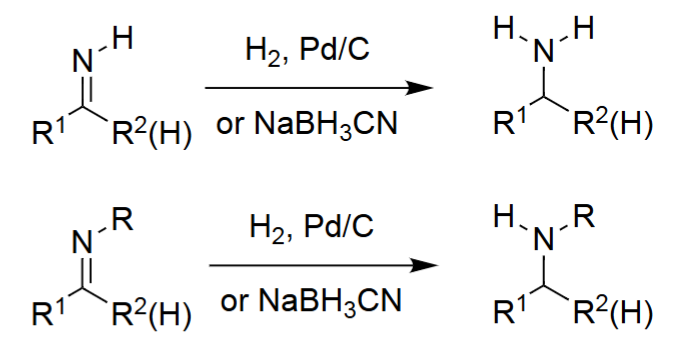

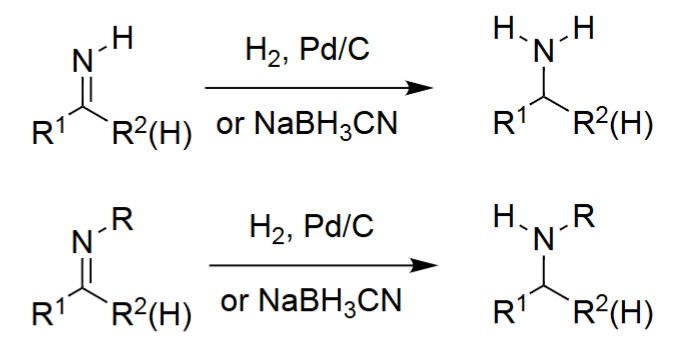

Reductive Amination → Amines (H2, Pd/C)

The aldehyde or ketone reacts with ammonia to form an imine intermediate.

A reducing agent (often NaBH₃CN) reduces the imine to a primary amine.

Works for both aldehydes and ketones.

Reductive Amination to Secondary Amines (1. RNH₂, 2. RA)

A primary amine reacts with the carbonyl to form an imine or iminium ion.

Reduction converts this intermediate into a secondary amine.

Allows controlled formation of N-monoalkylated products.

Produces R¹R²CH–NHR.

Reductive Amination to Tertiary Amines (1. R₂NH, 2. RA)

A secondary amine condenses with the carbonyl to form an iminium ion.

A reducing agent converts it into a tertiary amine.

Useful for synthesizing fully substituted amine centers.

Produces R¹R²CH–NR₂.

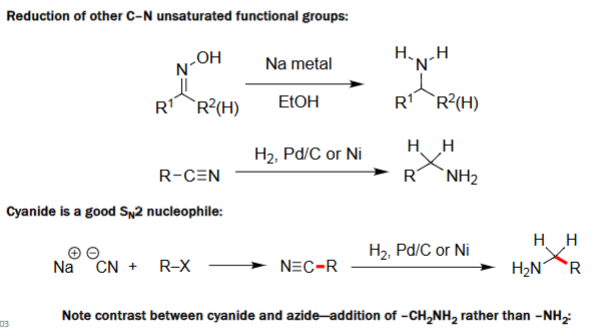

Reduction of C–N (1. Na/EtOH, 2. H₂/Pd–C or Ni)

Oximes (R¹R²C=NOH) are reduced by Na metal in EtOH to form primary or secondary amines.

Nitriles (R–C≡N) are reduced by H₂ with Pd/C or Ni to give primary amines (R–CH₂NH₂).

These reductions saturate the C–N multiple bond to yield the amine.

Useful for converting oximes or nitriles into corresponding amines.

Nucleophilic Cyanide Substitution (1. R-X, 2. H₂/Pd–C or Ni)

Cyanide (CN⁻) performs an SN2 attack on alkyl halides (R–X), forming nitriles (R–C≡N).

The nitrile is then reduced to a primary amine, adding a new –CH₂NH₂ unit.

This method extends the carbon chain by one carbon.

Unlike azide, cyanide introduces –CH₂NH₂, not –NH₂ directly.

Reduction of Amides (1. LiAlH₄, 2. H₂O)

LiAlH₄ reduces amides all the way to amines, breaking the C–O bond completely.

The carbonyl carbon becomes the carbon attached to the resulting amine (no loss of carbon).

Works for primary, secondary, and tertiary amides.

Final aqueous workup (H₂O) releases the amine from the aluminum complex.

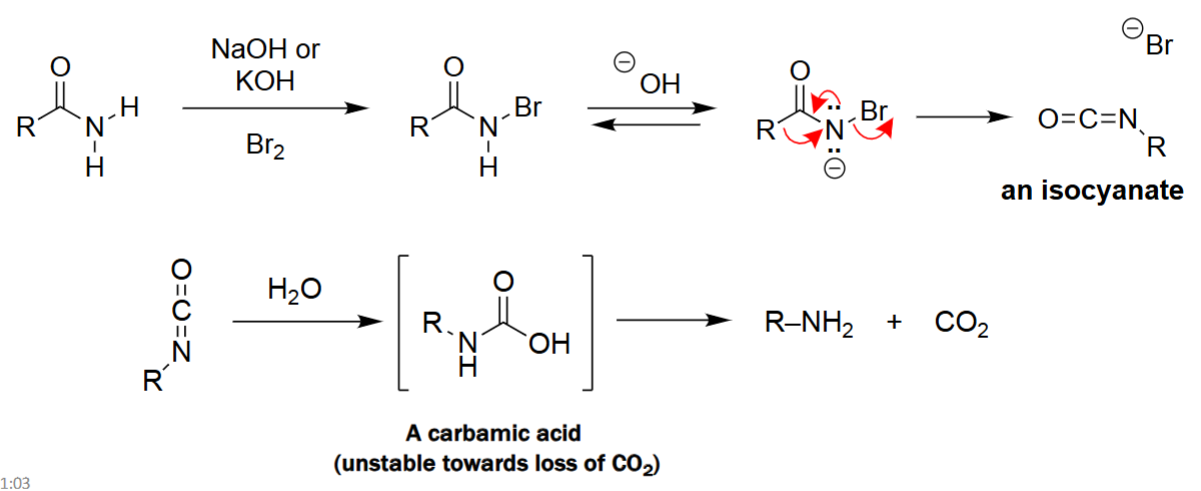

Hofmann Rearrangement (1. Br₂, 2. NaOH or KOH, H₂O)

A primary amide reacts with Br₂ and base to form an N-bromoamide intermediate.

Rearrangement occurs (migration of R- group) to generate an isocyanate.

The isocyanate is hydrolyzed to a carbamic acid, which is unstable.

Carbamic acid spontaneously loses CO₂, yielding a primary amine with one fewer carbon.

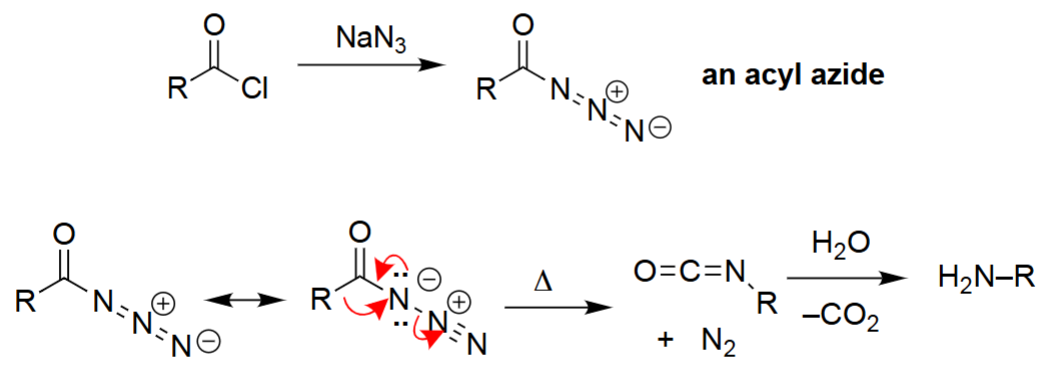

Curtius Rearrangement (1. NaN₃, 2. Δ, 3. H₂O)

An acyl chloride reacts with NaN₃ to form an acyl azide.

Upon heating (Δ), the acyl azide undergoes rearrangement, releasing N₂ gas.

Rearrangement produces an isocyanate intermediate.

Hydrolysis of the isocyanate yields a primary amine with one fewer carbon (plus CO₂).

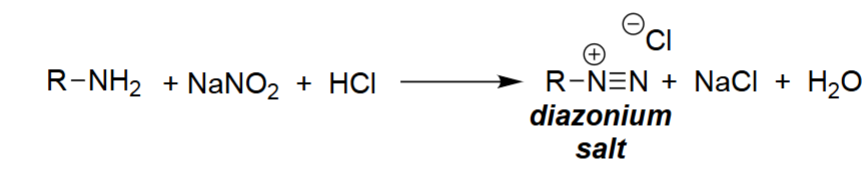

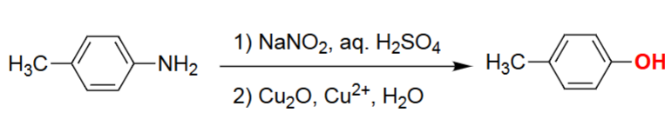

Diazotization of Primary Amines (NaNO₂, HCl)

NaNO₂ and HCl react to form nitrous acid (HONO).

HONO is converted under acidic conditions into the nitrosyl cation (NO⁺).

The amine attacks NO⁺, forming N-nitrosamine intermediates.

Further protonation and dehydration produce the diazonium salt (R–N≡N⁺ Cl⁻).

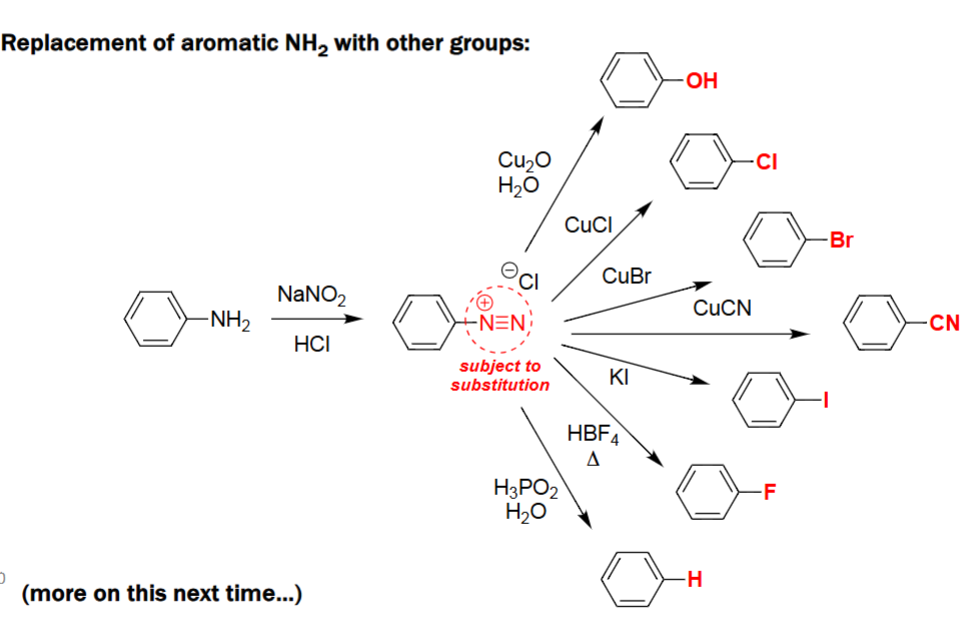

Aromatic Diazonium Substitution

Aniline (Ar–NH₂) is converted to the diazonium salt (Ar–N₂⁺ Cl⁻) using NaNO₂/HCl.

The diazonium group acts as a versatile leaving group for substitution.

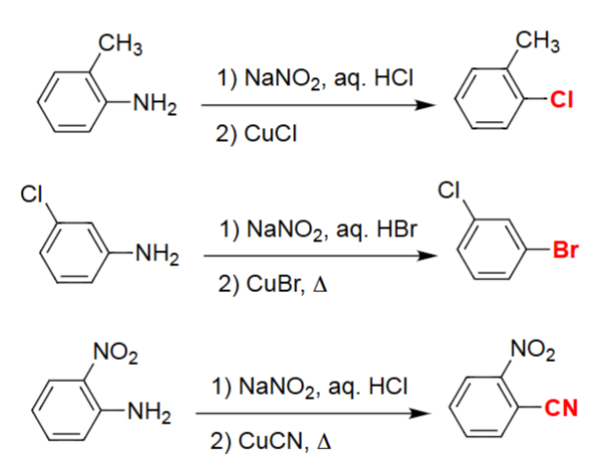

Sandmeyer Reactions (Ar–NH₂ → Ar–X using Cu(I) salts)

An aromatic amine is first converted to its diazonium salt with NaNO₂ and aqueous HX.

Cu(I) salts (CuCl, CuBr, CuCN) promote substitution of the diazonium group.

The reaction installs Cl, Br, or CN onto the aromatic ring depending on the Cu(I) reagent.

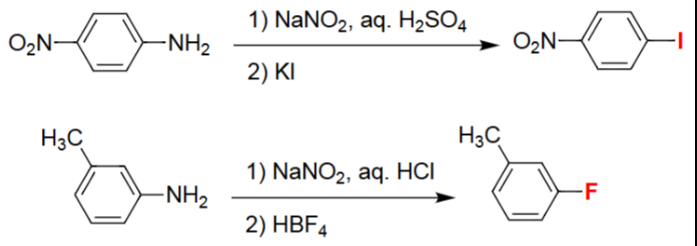

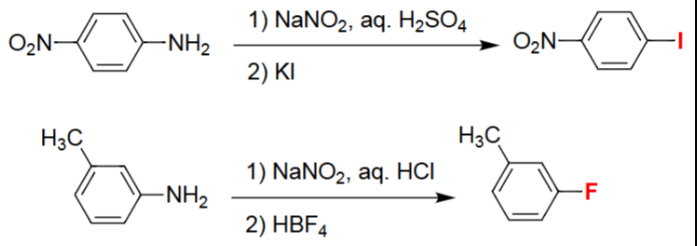

Aryl Diazonium → Aryl Iodide (1. NaNO₂/H₂SO₄, 2. KI)

Aniline is converted into the aryl diazonium salt under acidic nitrosation conditions.

Iodide from KI acts as a nucleophile toward the diazonium intermediate.

The –N₂⁺ group is displaced by I⁻, releasing N₂ gas.

Produces an aryl iodide with all substituents retained.

Aryl Diazonium → Aryl Fluoride (1. NaNO₂/HCl, 2. HBF₄)

Aniline is first transformed into its diazonium chloride via NaNO₂/HCl.

Treatment with HBF₄ yields the tetrafluoroborate diazonium salt.

Thermal decomposition releases N₂ and BF₃, inserting fluoride onto the ring.

Final product is an aryl fluoride preserving original substituents.

Diazonium Salts - Phenol (1. NaNO₂/H₂SO₄, 2. Cu₂O, Cu²⁺, H₂O)

The aniline is converted to a diazonium salt under acidic nitrosation conditions.

Copper(I/II) oxides in water promote substitution of the diazonium group.

The –N₂⁺ group is displaced by OH, releasing N₂ gas.

Final product is a phenol retaining all original aromatic substituents.

Diazo Coupling (NaNO₂ / HCl)

Convert aniline to a diazonium salt using nitrous acid.

Diazonium ion acts as a strong electrophile toward activated aromatic rings.

Rings with EDGs undergo rapid electrophilic aromatic substitution.

Produces brightly colored azo compounds (Ar–N=N–Ar) due to extended conjugation.

Making Tosylates (TsCl / pyridine)

Alcohols react with tosyl chloride (TsCl) in pyridine.

Forms tosylates (ROTs), which convert a poor leaving group (–OH) into an excellent one (–OTs).

Reaction occurs via nucleophilic attack of the alcohol oxygen on sulfur.

Pyridine neutralizes HCl formed during the process.

Making Sulfonamides (ArSO₂Cl + amine)

Amines react with sulfonyl chlorides (ArSO₂Cl) to make sulfonamides.

Nitrogen acts as the nucleophile and attacks sulfur.

Reaction proceeds similarly to tosylate formation (nucleophilic substitution at S).

Produces stable sulfonamides (R–NH–SO₂–Ar).

Sulfonamide Alkylation (1. Strong base, 2. R′–X, 3. H₃O⁺)

Strong base (NaNH₂ or NaH) deprotonates the sulfonamide N–H.

The nitrogen anion attacks an alkyl halide (R′–X) via SN2 to give an N-alkyl sulfonamide.

Acidic workup cleaves the sulfonyl protecting group.

Final product: a secondary amine (R–NHR′).

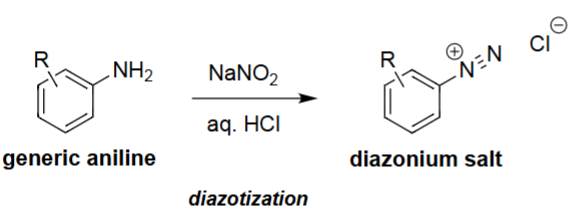

Jones Oxidation (Na₂Cr₂O₇)

Strong oxidation of aldehydes → carboxylic acids.

Strong oxidation of 1° alcohols → carboxylic acids.

2° alcohols → ketones.

Cannot stop at aldehyde; pushes fully to acid.

Acetone is solvent.

NaBH₄ Reduction (NaBH₄, EtOH)

Reduces aldehydes & ketones → alcohols.

Does not reduce esters, amides, or carboxylic acids.

Safe with protic solvents (EtOH, MeOH).

Selective for carbonyls in complex molecules.

KMnO4 Oxidation (KMnO₄, heat)

Strong oxidation: aldehydes/1° alcohols → acids.

2° alcohols → ketones.

Cleaves alkenes → carbonyls or acids.

Very aggressive, over-oxidation common.

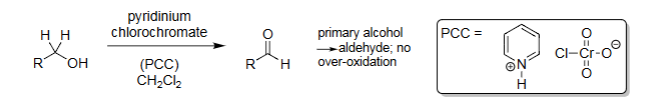

PCC Oxidation (PCC with solvent CH₂Cl₂)

1° alcohols → aldehydes (no over-oxidation).

2° alcohols → ketones.

Works under anhydrous conditions.

Milder than Jones/KMnO₄.

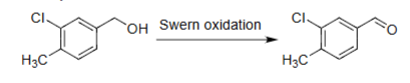

Swern Oxidation (DMSO, (COCl)₂, Et₃N)

1° alcohols → aldehydes.

2° alcohols → ketones.

No heavy metals.

Cold (–78°C) required.

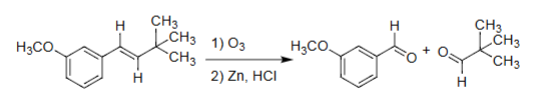

Ozonolysis (O₃ → Zn/HCl or DMS)

Cleaves alkenes → two carbonyls.

Reductive workup → aldehydes/ketones.

Oxidative workup → acids/ketones.

Exact cleavage of double bond.

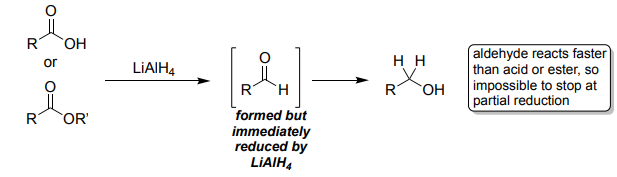

LiAlH₄ Reduction (1. LiAlH₄ 2. H₃O⁺)

Reduces aldehydes → 1° alcohols.

Reduces ketones → 2° alcohols.

Reduces esters/acids/amides → alcohols/amines.

Must be quenched carefully with water after reaction.

Grignard (1. R–MgBr 2. H₃O⁺)

Nucleophilic R⁻ attack on carbonyl carbon.

Aldehydes → 2° alcohols (add one R).

Ketones → 3° alcohols (add one R).

Adds C–C bonds (key carbon chain-building reaction).

Tollens Oxidation (Ag₂O, OH⁻ → H₃O⁺)

Selective aldehyde oxidation → carboxylate → acid.

Leaves alcohols/ketones unchanged.

Produces silver mirror.

Mild & chemoselective.

Wittig Reaction (Ph₃P=CH₂)

Converts carbonyl C=O → C=C.

Aldehydes → terminal alkenes with =CH₂.

Replaces oxygen entirely.

Good for stereoselective alkene formation; opposite of ozonolysis.

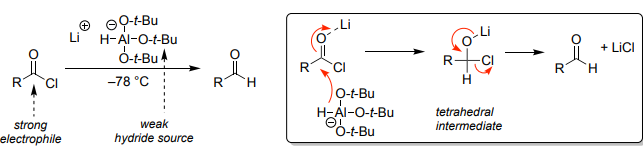

Weak Hydride Reduction (LTBA) (Li(t-BuO)₃, cold)

Selective reduction of acid chlorides → aldehydes.

Stops before alcohol stage.

Requires cold conditions (–78°C).

More selective than LiAlH₄.

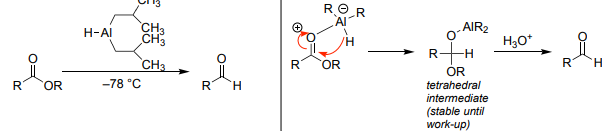

DIBAL-H Reduction (DIBAL-H → H₃O⁺)

Esters → aldehydes (controlled low temp).

Excess/warm → alcohols.

Nitriles → aldehydes (via imine).

Temperature-sensitive.

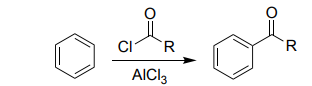

Friedel–Crafts Acylation (RCOCl, AlCl₃)

Benzene → aryl ketone.

No rearrangements.

Product deactivates the ring.

Clean one-substitution reaction.

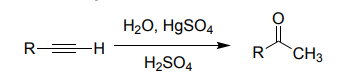

Alkyne Hydration (HgSO₄, H₂SO₄, H₂O)

Terminal alkyne → methyl ketone (Markovnikov).

Proceeds via enol → keto.

Needs Hg²⁺ catalyst.

Internal alkynes → ketones.

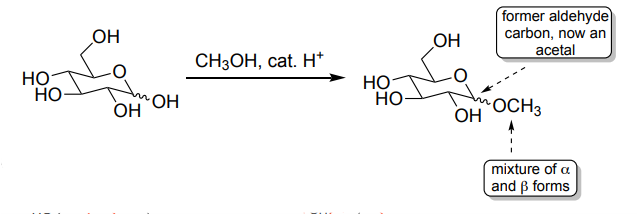

General Acetal Formation (2 ROH, H⁺)

Carbonyl → acetal (protected form).

Hemiacetal intermediate.

Stable in base.

Deprotected with aqueous acid.

Cyclic Acetal Formation (with diol) (HOCH₂CH₂OH, cat. H⁺)

Carbonyl + diol → 5-membered cyclic acetal.

Excellent protecting group.

Stable in base, removable in acid.

Driven by intramolecular ring closure.

Hydrazone Formation (PhNHNH₂, pH 4–5)

Carbonyl → C=N–NHPh (hydrazone).

Dehydration product from hydrazine/hydrazide reacting with an aldehyde or ketone.

Formed via condensation (loss of H₂O).

Product = hydrazone: Carbonyl oxygen replaced by =N–NHPh (or =N–NH₂ for hydrazine).

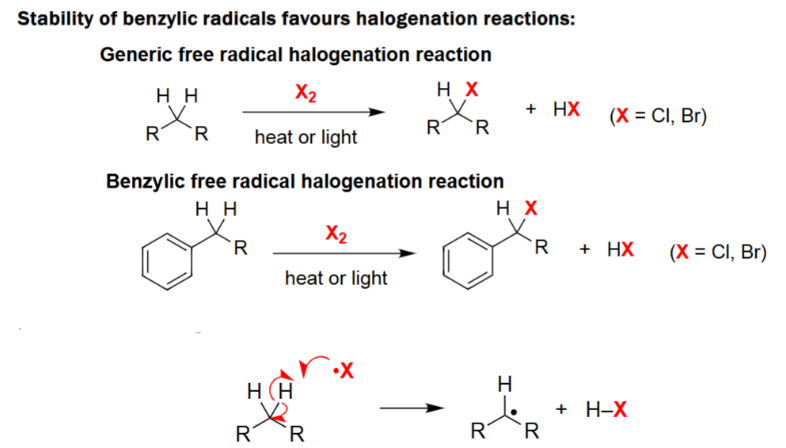

Benzylic Halogenation Radicalization

Generic free radical halogenation reaction.

Reacts with a halogen (X2) along heat or light.

Proceeds via hydrogen abstraction to form a free radical.

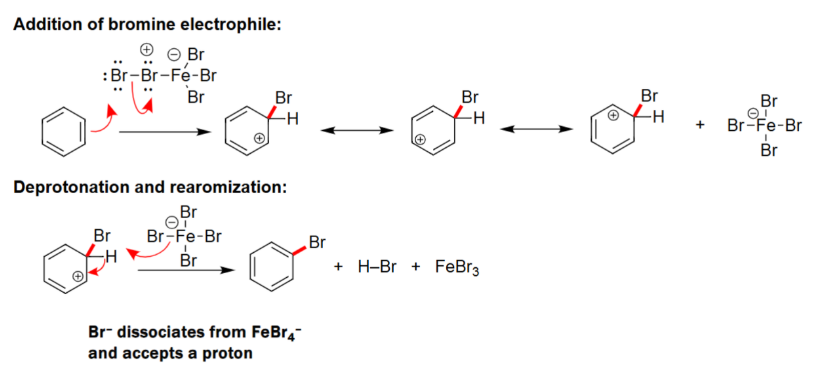

EAS Halogenation

To create a strong electrophile either AlCl3 or FeBr3 is needed.

Carbocation intermediate is formed.

Formulates a benzene ring with a halogen attached.

EAS Nitration

Acid (i.e. H2SO4) reacts with HNO3 to form a unstable electrophile.

Benzene reacts with the electrophile.

Adds NO2 to the benzene.

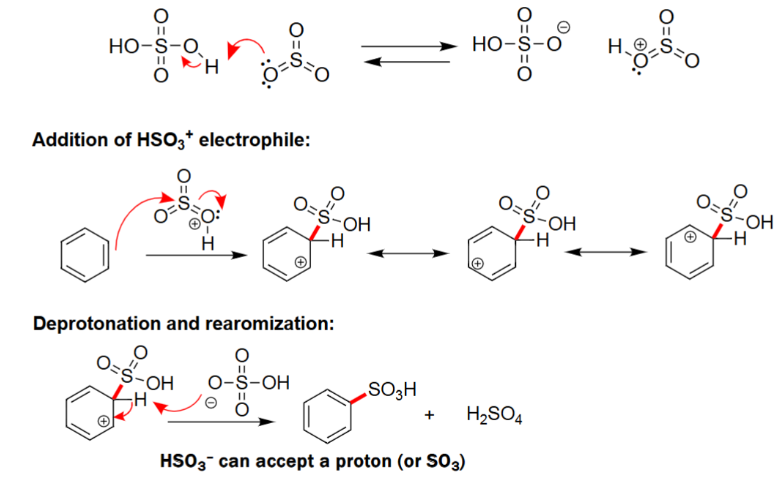

EAS Sulfonation

Forms its conjugate base and acid as byproducts.

Benzene reacts with unstable electrophile.

Forms a benzene with a HSO3 group attached.

Needs acid and heat to react.

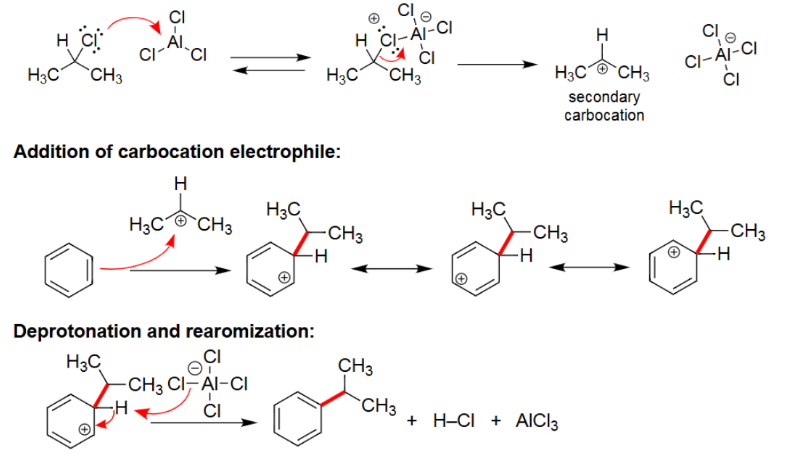

EAS Alkylation

Reacts with AlCl3/FeCl3.

Alkyl group is attached.

Carbocation rearrangement can occur.

EAS Acylation

Reacts with AlCl3/FeCl3.

Adds carbonyl group to benzene; forms a ketone.

No carbocation rearrangement.

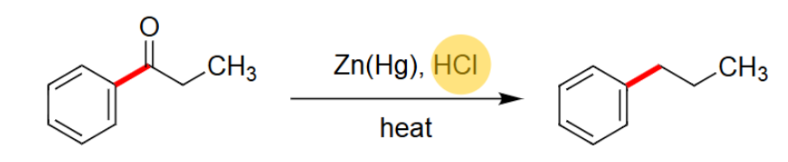

Clemmensen Reduction

Reacts using Zn(Hg) and HCl.

Needs heat.

Uses acidic conditions.

Takes off the =O.

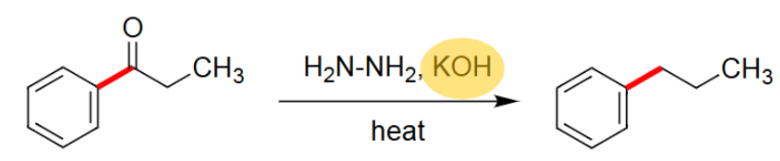

Wolff-Kishner (H2N-NH2, KOH, heat)

Reacts using several reagents.

Uses basic conditions.

Takes off the =O.

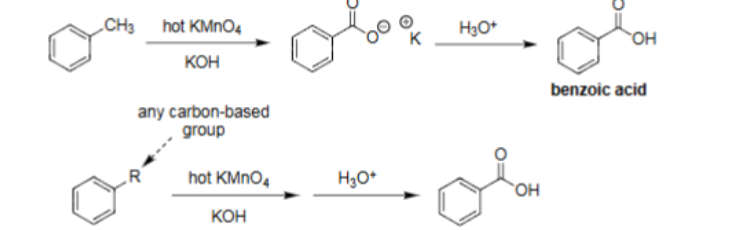

Oxidative Degradation (1. Hot KMnO4, KOH 2. H3O+)

Hot KMnO4 with KOH for first reaction, then H3O+ for second reaction.

Leads to benzoic acid formation.

Nitro → Aniline (Fe/HCl)

Conversion of NO2 to NH2 (nitro to aniline).

However, other substituents on the benzene can react.

Fe, HCl can ensure no other reactions occur other than NO2 → NH2.

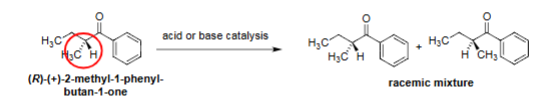

Racemization (acid/base catalysis)

Acid/base removes α-H → enolate/enol forms.

α-Carbon next to carbonyl.

Reprotonation gives loss of stereochemistry.

Produces racemic mixture from chiral ketone.

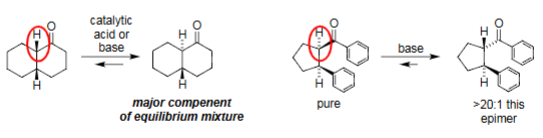

Epimerization (catalytic acid/base)

Acid/base catalysis forms enolate at α-C.

Reprotonation flips configuration → epimer formed.

Cyclic Ketones.

Equilibrium favors the more stable chair conformer.

Base can drive formation of a specific epimer (>20:1).

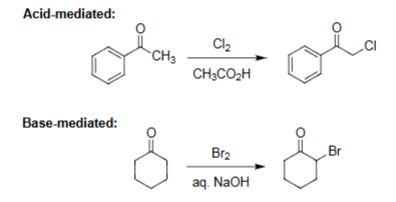

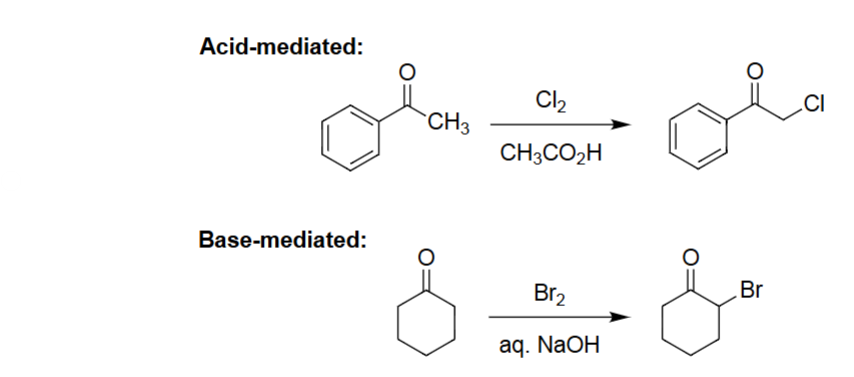

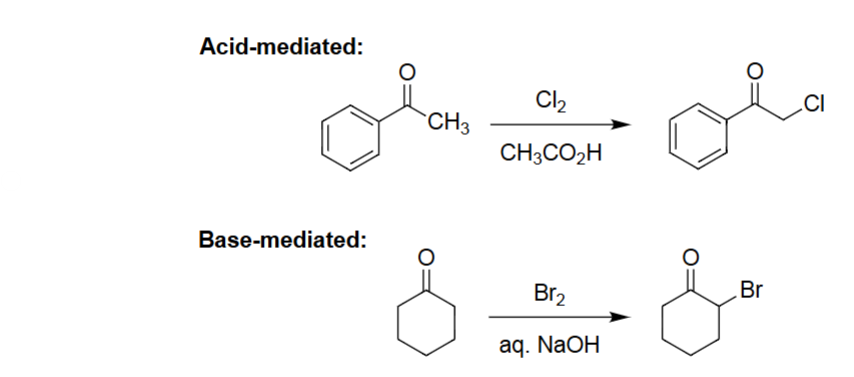

Acid-Mediated Halogenation (Cl2, CH3CO2H)

Enol formation occurs under acidic conditions.

Enol reacts with Cl₂ to install chlorine at the α-carbon.

Reaction is monochlorination (no over-halogenation).

Works for aryl and alkyl ketones, giving α-chloro ketones.

Base-Mediated Halogenation (Br2, NaOH)

Enolate forms rapidly under strong base, making α-substitution very fast.

Poly-halogenation at the α-carbon (unlike acid) → haloform.

Single bromination.

Produces an α-bromoketone under strongly basic, irreversible conditions.

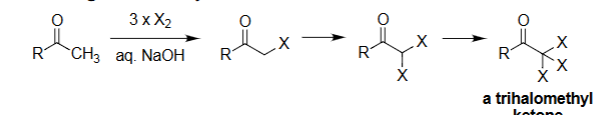

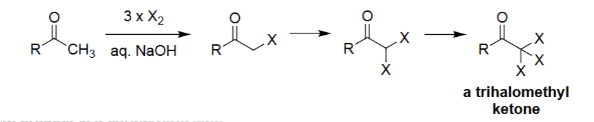

Haloform Reaction (X₂, NaOH)

Converts a methyl ketone (R–CO–CH₃) into a carboxylate salt.

Requires three successive α-halogenations under basic conditions.

The trihalomethyl group (–CX₃) is cleaved to form haloform (CHX₃).

Produces R–COO⁻ Na⁺ + CHX₃ (chloroform, bromoform, or iodoform).

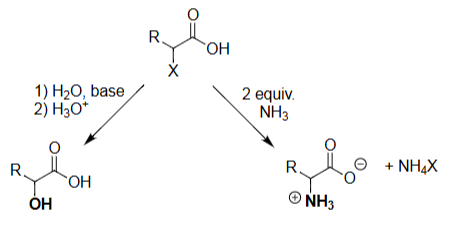

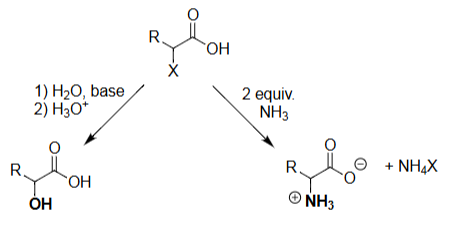

Hell-Volhard-Zelenksy Reaction (X₂, P → PX₃)

Converts R–COOH into α-haloacids (R–CO–CHX–OH).

X₂ + P generates PX₃, activating the α-position.

Halogenation occurs at the α-carbon next to the carbonyl.

Workup with H₂O yields the α-halo carboxylic acid.

HVZ Halide Displacement (H₂O, Base → H₃O⁺)

Performs SN2 substitution at the α-carbon.

Water acts as the nucleophile under basic conditions.

Forms an α-hydroxy acid after acid workup.

Overall: R–CHX–COOH → R–CHOH–COOH.

HVZ Amination (NH₃, 2 equiv)

Ammonia performs SN2 attack at the α-carbon.

Requires excess NH₃ to drive substitution.

Produces the α-amino acid (as NH₃⁺ product).

Halide leaves as NH₄X.

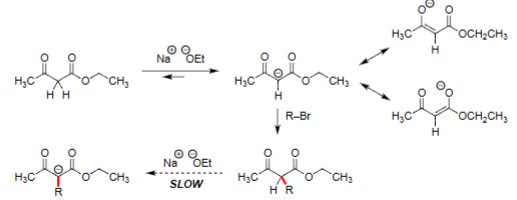

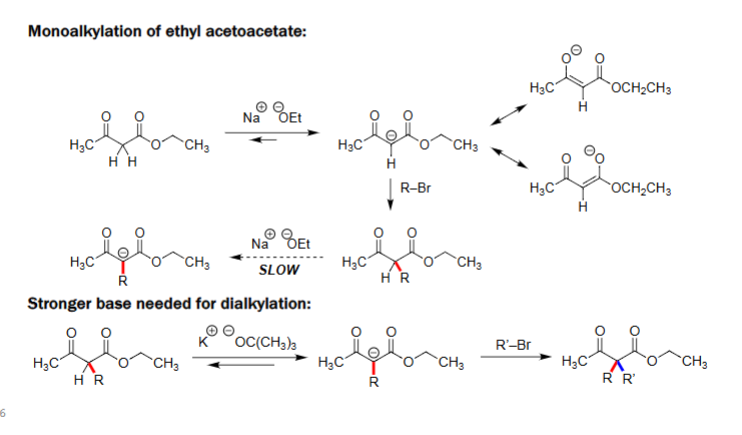

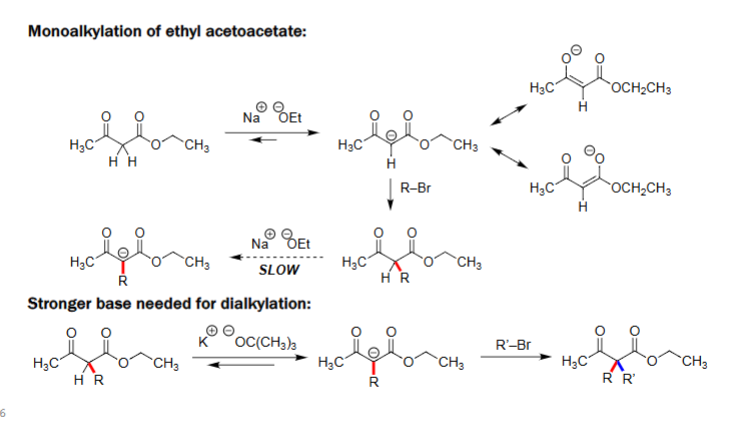

Alkylation of β-Dicarbonyl Enolates (NaOEt and/or LDA / R–Br)

NaOEt generates the stabilized enolate of ethyl acetoacetate for monoalkylation.

Enolate attacks primary alkyl halides (R–Br) via SN2, giving α-alkylacetoacetates.

A stronger base (e.g., LDA or KOtBu) is needed to fully deprotonate the second α-H for dialkylation.

Second alkylation gives α,α-dialkylated β-keto esters (R and R′ introduced).

Michael Addition [soft nucleophile + α,β-unsaturated carbonyl]

Conjugate 1,4-addition to an alkene activated by an electron-withdrawing group (EWG).

Nucleophile attacks the β-carbon, forming a stabilized enolate.

Enolate is then protonated to give the final Michael adduct.

Works best with soft nucleophiles (enolates, amines, thiolates).

Enamine Alkylation [R³–X]

The enamine reacts with the alkyl halide first at nitrogen (N-alkylation, reversible).

The system equilibrates back to the enamine, which then performs C-alkylation at the α-carbon (irreversible).

Forms a C-alkylated iminium intermediate.

Hydrolysis yields the final α-alkylated carbonyl and regenerates the amine.

Enamine Acylation [R³COCl]

Initial N-acylation is reversible.

Reaction proceeds to C-acylation (irreversible).

Net result: α-acylated product after hydrolysis.

Forms an enammonium byproduct.

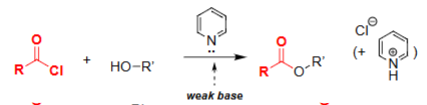

Ester Formation w/ Acyl Chloride (Pyridine)

Acts as a weak, non-nucleophilic base.

Neutralizes HCl formed during esterification.

Prevents protonation of the alcohol nucleophile.

Helps drive formation of the ester product.

Amide Formation w/ Acyl Chloride (Pyridine)

Serves as the nucleophile that attacks the acid chloride.

Requires ≥2 equivalents: one to react, one to neutralize HCl.

Prevents protonation of the attacking amine.

Drives formation of the amide product.

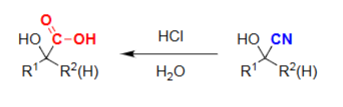

Nitrile Hydrolysis (HCl, H2O)

Cyanohydrin becomes a carboxylic acid.

All nitriles can be made from SN2 geometry.

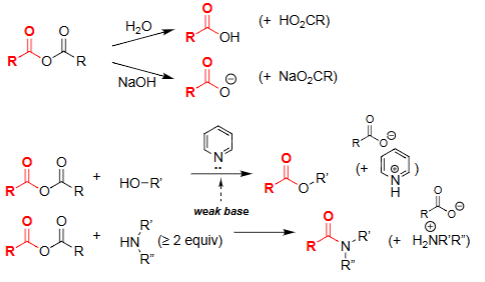

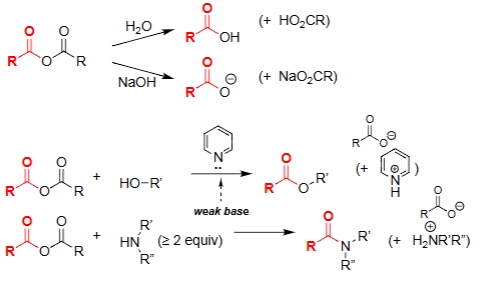

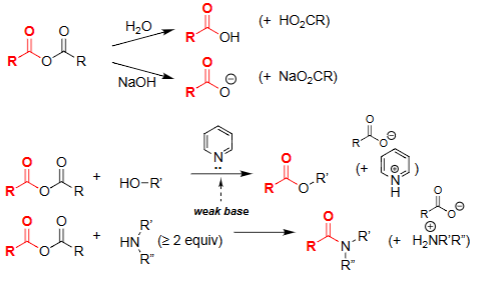

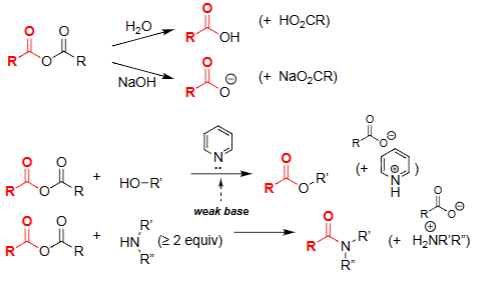

Hydrolysis of Acid Anhydride (H₂O)

Water attacks one carbonyl of the anhydride.

Produces a carboxylic acid and a carboxylate.

Reaction is driven by relief of anhydride strain.

No base required, but reaction generates an acidic product.

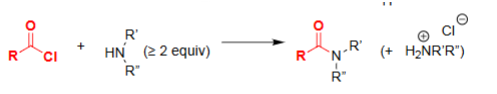

Amine–Anhydride Reaction [Anhydride + ≥2 eq Amine]

Amine attacks one carbonyl of the anhydride, forming a tetrahedral intermediate.

Collapse of the intermediate gives the amide and a carboxylate (or protonated acid if weak base present).

Extra equivalent of amine neutralizes the acid formed during the reaction.

Alcoholysis of Anhydride (ROH, pyridine)

Alcohol attacks one carbonyl of the anhydride.

Forms an ester + carboxylate.

Pyridine acts as weak base to neutralize acid formed.

Selective way to make esters from anhydrides.

Aminolysis of Anhydride (R₂NH ≥ 2 equiv)

Amine attacks the anhydride to form an amide + carboxylate.

Requires excess amine to neutralize the acid formed.

Very fast due to strong nucleophilicity of amines.

Common method to make amides from anhydrides.

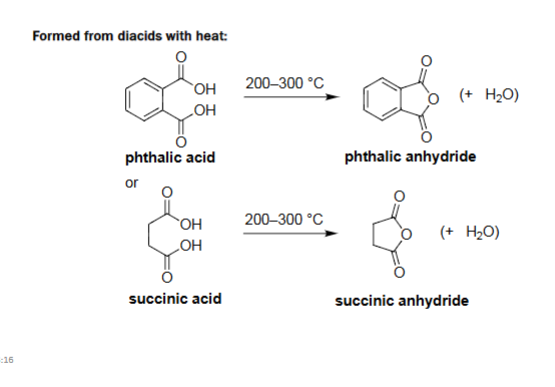

Intramolecular Anhydride Formation (Heat, 200–300 °C)

Diacids with appropriately spaced COOH groups dehydrate when heated.

Forms a cyclic anhydride + water.

Favored when a 5- or 6-membered ring can form (stable ring size).

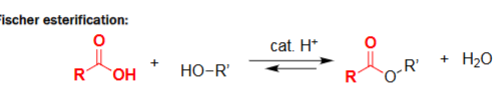

Fischer Esterification (ROH, cat. H+)

Formation of an ester from a carboxylic acid and an alcohol.

Acid catalyst drives nucleophilic attack and dehydration.

Reaction is reversible and reaches an equilibrium.

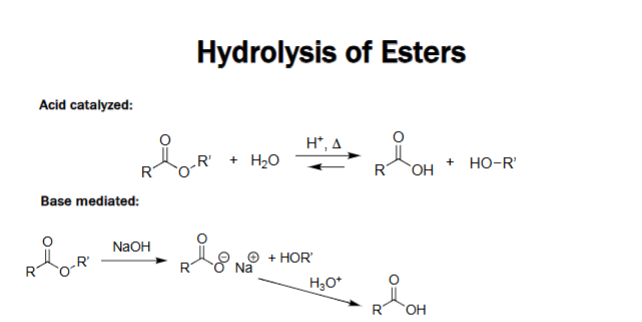

Acid-Catalyzed Ester Hydrolysis [H⁺, Δ]

Ester + H₂O ⇌ Carboxylic acid + Alcohol.

Requires acid catalyst and heat.

Reversible reaction.

Proceeds through protonation and water attack.

Base-Mediated Ester Hydrolysis (Saponification) [NaOH]

Ester + NaOH → Carboxylate salt + Alcohol.

Irreversible due to carboxylate formation.

No acid catalyst required.

Acid workup gives the free carboxylic acid.

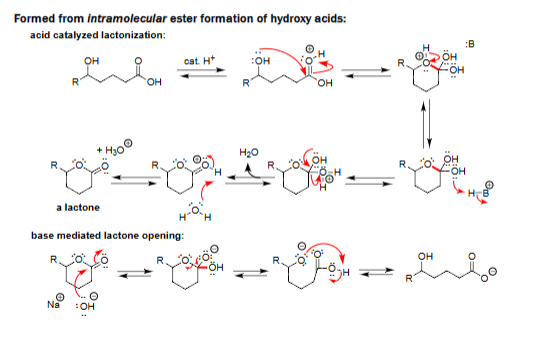

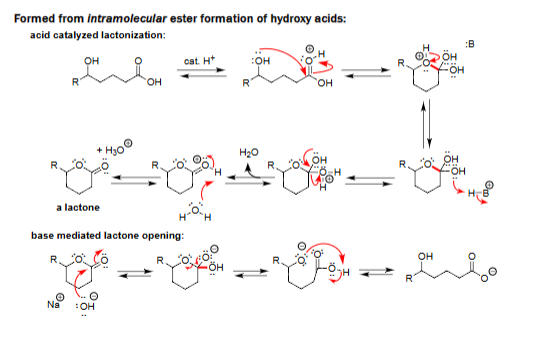

Acid-Catalyzed Lactonization [cat. H⁺]

Forms a cyclic ester (lactone) from a hydroxy acid via intramolecular attack.

Requires acid catalysis.

Water is lost in the ring-closing step.

Produces a stable lactone in equilibrium.

Base-Mediated Lactone Opening [NaOH]

Hydroxide opens the lactone to give a hydroxy-carboxylate.

Reaction is driven by formation of the carboxylate salt.

Ring is irreversibly cleaved under basic conditions.

Final protonation gives the hydroxy acid if desired.

Amide Formation from Esters [Amine]

Ester reacts with an amine to form an amide.

Alcohol (ROH) is released as the leaving group.

Works with primary or secondary amines.

Net substitution at the carbonyl.

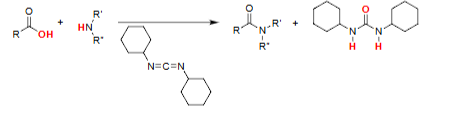

Amide Formation from Acids [DCC]

Carboxylic acid and amine combine to form an amide.

Carbodiimide (e.g., DCC) activates the acid for coupling.

Enables direct amide formation from unreactive carboxylic acids.

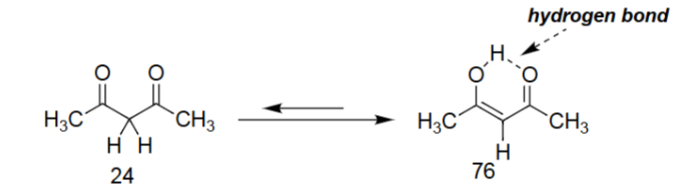

Keto–Enol Tautomerism [cat. acid or base]

Enol content increases when an adjacent C=O stabilizes it (intramolecular H-bonding).

Enol is stabilized further through resonance.

Keto and enol forms interconvert reversibly.

Ratio depends on structural stabilization shown in the scheme.

Tautomerization and Racemization [cat. acid or base]

Enolate/enol formation removes the chiral center’s configuration.

Re-protonation can occur from either face, forming enantiomers.

Regeneration of the keto form yields a 50:50 racemic mixture.

Enolate Quenching with D₂O [acid or base]

Enolate treated with D₂O gives deuterium incorporation at the α-position.

Works under catalytic acid or base conditions.

Replaces α-H atoms with D atoms.

Reaction occurs because D₂O serves as the proton (deuteron) source.

α-Halogenation (Acid-Mediated) [Cl₂, CH₃CO₂H]

Ketone undergoes selective α-chlorination.

Acid conditions favor monohalogenation.

Chlorine substitutes one α-H.

Product is an α-chloro ketone.

α-Halogenation (Base-Mediated) [Br₂, aq. NaOH]

Ketone is converted to an enolate under base.

Enolate reacts with Br₂ to install α-Br.

Reaction proceeds efficiently under aqueous base.

Gives an α-bromo ketone.

Haloform Reaction [X₂, aq. NaOH]

Methyl ketones undergo exhaustive α-halogenation to form a trihalomethyl ketone.

Base promotes cleavage to give a carboxylate salt.

The trihalomethyl group departs as a haloform (CHX₃).

Produces chloroform, bromoform, or iodoform depending on X.

Hell–Volhard–Zelinsky (HVZ Reaction) [X₂, P; H₂O]

Converts carboxylic acids into α-haloacids (X = Cl or Br).

X₂ and phosphorus generate PX₃ in situ to activate the acid.

First forms an α,α-dihalogenated intermediate.

Hydrolysis yields the α-halo carboxylic acid.

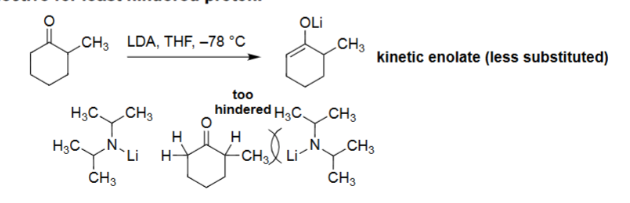

Enolate Formation with LDA (LDA, THF, cold)

Formed by deprotonation of diisopropylamine with n-BuLi (pKa ~ 38).

Very strong base but non-nucleophilic due to steric hindrance.

Removes the least hindered α-proton, giving the kinetic enolate.

Low temperature (–78 °C, THF) reinforces fast, selective deprotonation.

Monoalkylation of Ethyl Acetoacetate (1. NaOEt, 2. R-X)

Ethyl acetoacetate is deprotonated at the α-carbon by sodium ethoxide (NaOEt).

The resulting enolate reacts with an alkyl halide (R–Br) to form the monoalkylated product.

Enolate formation is reversible, so the reaction is slower and can give mixtures.

Dialkylation Requires a Stronger Base

After monoalkylation, the α-hydrogen becomes much less acidic (less stable)

NaOEt is too weak to deprotonate the product.

A strong, non-nucleophilic base such as potassium tert-butoxide (KOtBu) is required.

This strong base forms a second enolate, which then reacts with another alkyl halide (R′–Br) to give the dialkylated product.

Amide → Carboxylic Acid (H₃O⁺, Heat)

Protonate carbonyl to increase electrophilicity.

Water attacks to form tetrahedral intermediate.

–NH₂ becomes –NH₃⁺ and leaves.

Carbonyl reforms, giving the carboxylic acid.

Dehydration of Primary Amides to Nitriles (P₄O₁₀ or acetic anhydride)

Converts primary amides (R-CONH₂) into nitriles (R-C≡N).

Reaction requires heat (Δ).

By-products: H₃PO₄ (from P₄O₁₀) or CH₃CO₂H (from Ac₂O).

Catalytic Hydrogenation (H₂, Pd/C)

Replaces the halogen with a hydrogen (X → H).

Catalytic hydrogenation breaks the C–X bond.

Works best for benzyl, allyl, and primary alkyl halides.

Produces a fully reduced alkane as the final product.

The Iodoform Reaction (I₂ / OH⁻)

Oxidizes methyl ketones (or secondary alcohols that become them).

Forms a carboxylate by cleaving the C–CH₃ bond.

Produces CHI₃ (iodoform) as a yellow precipitate.

Diagnostic test: only works if the carbonyl has a –CO–CH₃ group.

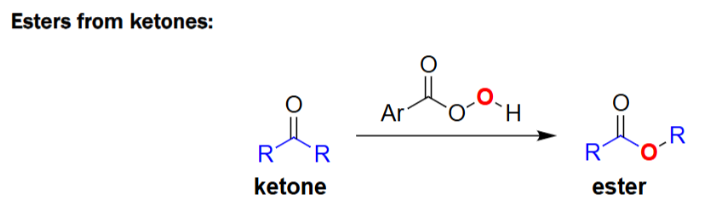

Baeyer–Villiger Oxidation (peroxyacid, e.g., mCPBA)

Converts ketones → esters by inserting an oxygen next to the carbonyl.

Uses a peracid (ArCO₃H) as the oxidizing reagent.

Migrating group (R) shifts onto the peroxide oxygen during reaction.

Follows migratory aptitude: tertiary > secondary > phenyl > primary > methyl.

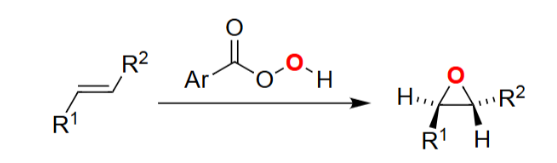

Alkene Epoxidation (peroxyacid, e.g., mCPBA)

Converts alkenes → epoxides in one step.

Reaction is concerted, preserving stereochemistry.

Forms a three-membered cyclic ether.

Occurs via oxygen transfer from the peracid to the C=C bond.

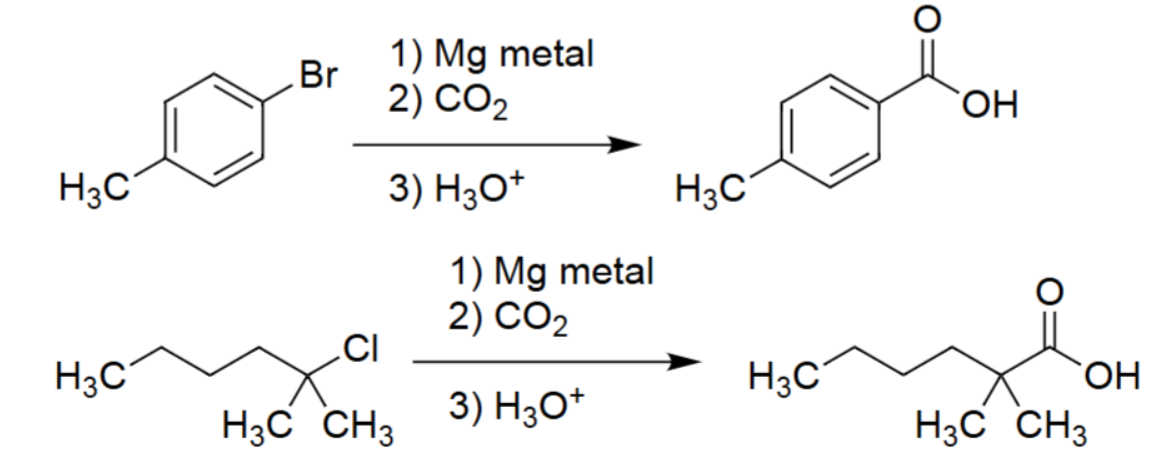

Grignard Carboxylation (Mg metal → Grignard; CO₂; H₃O⁺)

Converts alkyl or aryl halides → carboxylic acids.

Mg inserts into C–X bond forming RMgX (Grignard reagent).

Grignard attacks CO₂, forming a carboxylate.

Acid workup protonates to give the carboxylic acid.

Retro-Aldol Reaction [Base (⁻OH or :B)]

Base deprotonates the β-hydroxy group, forming an alkoxide.

Alkoxide collapses, breaking the C–C bond between α- and β-carbons.

Electrons flow to regenerate the carbonyl on the α-carbon.

Produces the original enolate + carbonyl starting materials (reaction is reversible).

Retro-Aldol with Ketones + Dehydration [NaOH, Δ]

Ketone forms β-hydroxy ketone (aldol) in equilibrium.

Retro-aldol favored for ketones unless dehydration occurs.

Heat drives E1cB dehydration of aldol → α,β-unsaturated ketone.

Removing H₂O pushes equilibrium toward product formation.

Aldol Condensation [Base + Heat (Δ)]

β-hydroxy carbonyl undergoes base-promoted dehydration

Base removes α-H → forms enolate that pushes out OH⁻

C=O reforms as C–O bond collapses, eliminating water

Product is an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl; conjugation drives reaction to completion

Crossed Aldol Reaction [weak base (RO⁻ or HO⁻)]

Weak bases form multiple enolates, giving no selectivity.

Each enolate can attack the other carbonyl, producing multiple aldol additions.

Alkoxide intermediates are protonated → β-hydroxy carbonyls.

Final outcome: a mixture of crossed aldol products.

Intramolecular Aldol Condensation [base, heat]

Enolate forms and attacks an intramolecular carbonyl, creating a ring.

5- and 6-membered rings form fastest (lowest strain + favorable geometry).

Larger rings (7+) form slowly due to entropic and geometric penalties.

Ketone electrophiles react more slowly than aldehydes → affects which ring forms.