The Chemical Senses

1/15

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

16 Terms

Where does taste detection primarily occur?

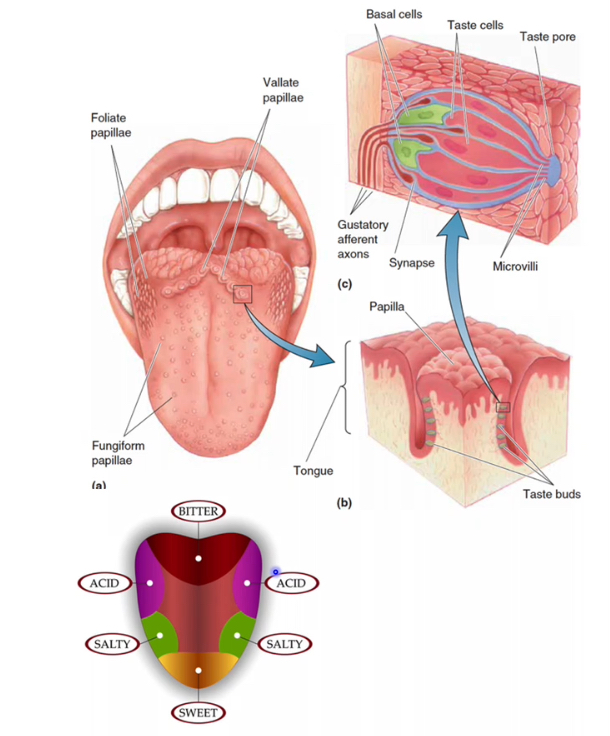

Taste reception is driven by specialised epithelial cells (taste receptor cells) that transduce chemical stimuli into neural signals. These cells are organised into taste buds, which sit within papillae on the tongue and in a few other regions of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Tongue: papillae

Papillae are surface specialisations that increase area and house taste buds.

Folate (ridge-shaped) papillae

Found on the posterolateral edges of the tongue.

Contain many taste buds in their grooves.

Vallate (pimple-shaped) papillae

Large papillae arranged in a V at the back of the tongue.

Contain a high density of taste buds and contribute strongly to taste.

Fungiform (mushroom-shaped) papillae

Scattered mainly over the anterior tongue.

Each contains a small number of taste buds.

Taste buds

Taste buds are clusters of cells embedded within papillae epithelium.

They contain taste receptor cells, which detect dissolved tastants.

Basal cells act as precursors, replacing taste receptor cells regularly.

Gustatory afferent axons synapse with taste receptor cells to carry signals to the brain.

Tastants enter through the taste pore and interact with microvilli on receptor cells.

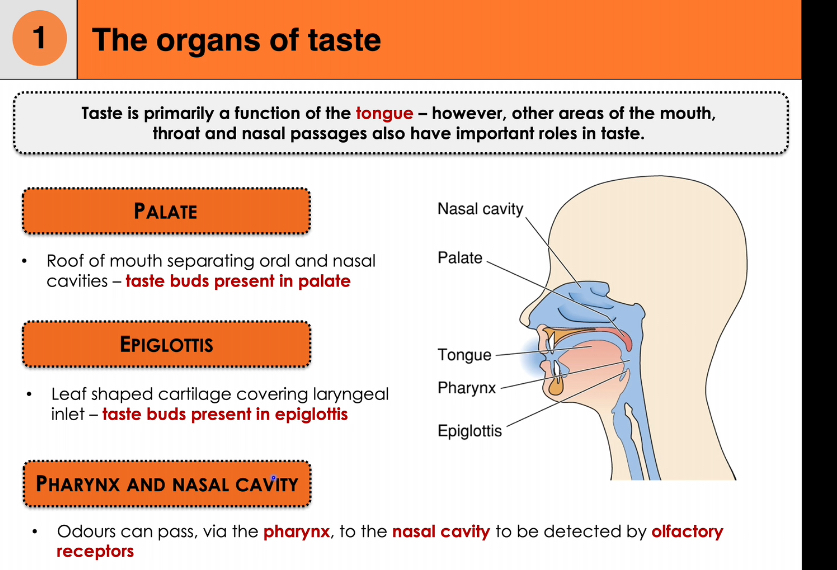

Organs of taste beyond the tongue

Taste is mainly a tongue function, but other regions contribute.

Palate

Forms the roof of the mouth.

Contains taste buds that add to overall taste perception.

Epiglottis

Leaf-shaped cartilage at the laryngeal inlet.

Contains taste buds, especially important for detecting potentially harmful substances during swallowing.

Pharynx and nasal cavity (flavour integration)

Odours from food travel from the pharynx into the nasal cavity during chewing and swallowing.

Olfactory receptors detect these odours.

The brain integrates taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) to produce flavour.

Chemical tastants activate taste receptor cells in taste buds.

Taste buds are mainly located in tongue papillae but are also present in the palate and epiglottis.

Signals travel via gustatory afferent nerves to the brain.

Flavour perception results from combined input from taste receptors and olfactory receptors.

5 basic tastes + How do we perceive flavour?

Sweet

Salt

Sour

Bitter

Umami

We perceive these flavours by:

Smell

Touch- texture and temp

How do taste receptor cells send information to the brain?

Tastants change the membrane potential of the taste cell, causing depolarisation → neurotransmitter release → activation of gustatory afferent axons.

Taste transduction

The 5 different tastes are transduced via different mechanisms

Saltiness and sourness- ion channel mechanisms

Bitterness,Sweetness and Umami- GPCR via T1 and T2 taste receptor

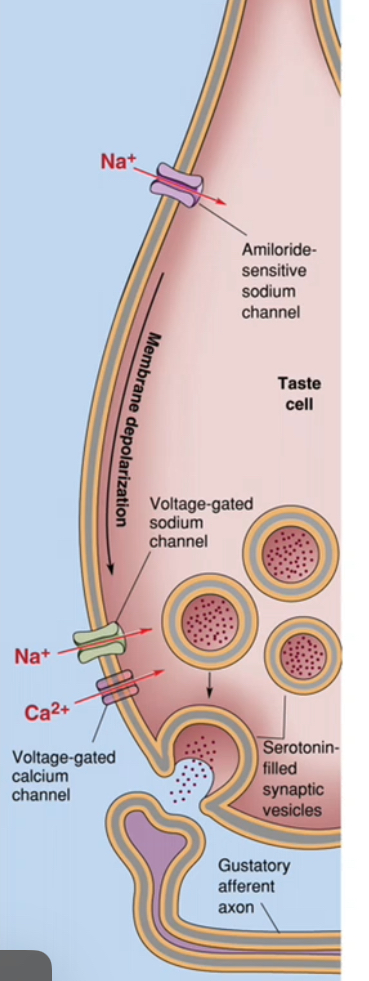

Taste transduction: Saltiness(MaCl)

Na⁺ enters the taste receptor cell directly through Na⁺-selective channels.

This direct ion influx depolarises the taste cell without second messengers.

Step-by-step transduction of saltiness

Table salt (NaCl) dissolves in saliva, providing Na⁺.

Na⁺ moves down its concentration gradient into the taste receptor cell.

Entry occurs through amiloride-sensitive Na⁺ channels (ENaC).

These channels are not voltage-gated and are usually open, allowing detection of low salt concentrations.

Na⁺ influx makes the membrane potential less negative.

The taste cell depolarises.

Electrical to chemical signal conversion

Depolarisation opens voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels at the base of the taste cell.

Ca²⁺ enters the taste receptor cell.

Increased intracellular Ca²⁺ triggers vesicular neurotransmitter release (e.g. serotonin).

Neurotransmitter is released from the taste cell, not the nerve.

Activation of the gustatory afferent

Neurotransmitter binds receptors on the gustatory afferent neuron.

The afferent neuron depolarises.

An action potential is generated in the afferent axon.

This signal is transmitted to the brainstem as “salty” taste.

Why this is an ion channel mechanism

The tastant ion (Na⁺) itself enters the cell.

No GPCRs or second messengers are required.

The response is fast and concentration-dependent.

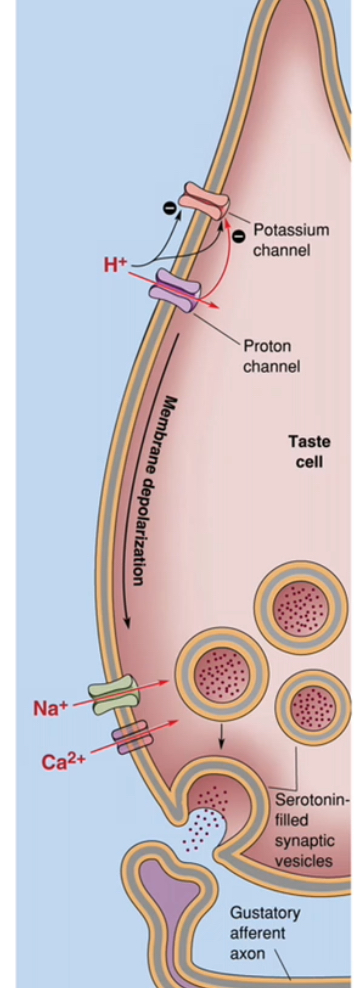

Taste transduction: Sourness

Protons (H⁺) from acids increase positive charge inside the taste receptor cell and reduce K⁺ efflux, causing membrane depolarisation.

How H⁺ produces depolarisation

Acidic foods release H⁺ in saliva.

H⁺ affects sour-sensitive taste cells in two main ways:

H⁺ enters through proton-permeable channels, adding positive charge.

H⁺ blocks K⁺-selective channels, preventing K⁺ from leaving the cell.

Reduced K⁺ efflux means the cell cannot maintain a negative resting potential.

Net effect is depolarisation of the taste cell membrane.

Electrical to chemical signal conversion

Depolarisation opens voltage-gated Na⁺ channels, amplifying the depolarisation.

Depolarisation also opens voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels at the base of the taste cell.

Ca²⁺ enters the taste receptor cell.

Neurotransmitter release and nerve activation

Increased intracellular Ca²⁺ triggers vesicular release of neurotransmitter (commonly serotonin).

Neurotransmitter is released from the taste receptor cell, not the nerve.

The gustatory afferent neuron is activated.

The afferent neuron generates an action potential that travels to the brainstem.

Why sour taste uses an ion channel mechanism

The tastant (H⁺) directly alters ion flow across the membrane.

No GPCRs or second messengers are required.

This makes sour taste rapid and intensity-dependent.

Taste Receptor Proteins: T1Rs and T2Rs

T1R and T2R receptor families, which are Gq-coupled GPCRs.

Bitter, sweet, and umami tastes are detected when G-protein–coupled taste receptors (GPCRs) on taste receptor cells bind specific chemicals.

These receptors function as dimers, and ligand binding activates an intracellular G-protein pathway rather than directly opening ion channels.

The receptor families involved

Two related GPCR families are used:

T1Rs → sweet and umami

T2Rs → bitter

Both receptor families are Gα-coupled, meaning activation triggers second-messenger signalling inside the taste cell.

Bitter taste detection (T2Rs)

Bitter compounds are detected by ~25 different T2R receptors.

Each T2R can respond to multiple bitter substances.

This broad receptor set explains why humans can detect many chemically different bitter (often toxic) molecules.

Sweet taste detection (T1Rs)

Sweet taste is detected by one receptor complex.

This receptor is a heterodimer made of:

T1R2 + T1R3

Different sweet molecules bind to different sites on the same receptor complex.

Umami taste detection (T1Rs)

Umami taste is also detected by one receptor complex.

This receptor is a heterodimer made of:

T1R1 + T1R3

It primarily detects amino acids such as glutamate.

Key unifying idea

Taste quality is determined by which receptor dimer is activated, not by the identity of the neuron.

Bitter uses many receptors (many T2Rs).

Sweet and umami each use one specific T1R heterodimer.

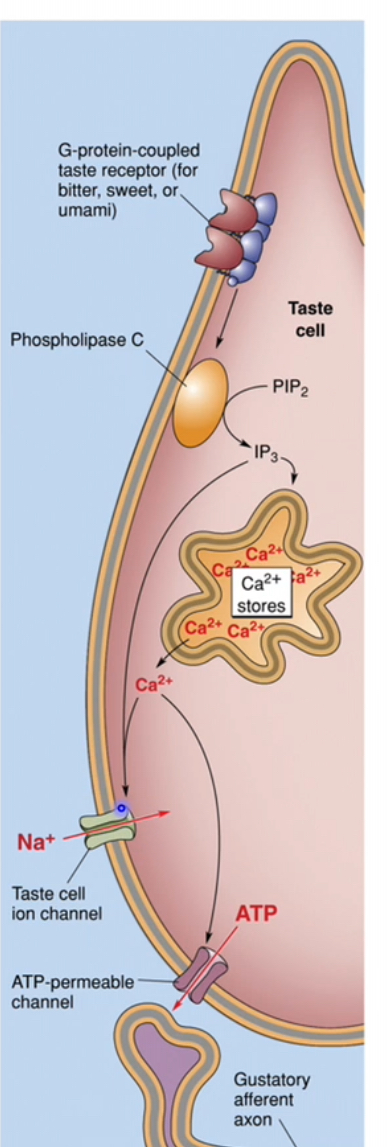

Taste transduction: Bitterness

Bitter molecules bind to T2R receptors on the taste receptor cell membrane

T2Rs are G-protein–coupled receptors linked to Gq

Receptor activation switches on the associated G protein

Intracellular signalling cascade

Activated Gq stimulates phospholipase C (PLC)

PLC breaks down membrane PIP₂ into IP₃ (and DAG, though IP₃ is the key player here)

Calcium release and ion channel effects

IP₃ binds to receptors on intracellular Ca²⁺ stores

Ca²⁺ is released into the cytoplasm

Increased Ca²⁺ also activates a Ca²⁺-dependent Na⁺ channel

Na⁺ entry further increases membrane depolarisation

Taste cell depolarisation

Combined effects of:

Ca²⁺ release

Na⁺ influx

Cause strong depolarisation of the taste receptor cell

Neurotransmitter release and nerve activation

Depolarisation triggers ATP release from the taste cell

ATP acts as the neurotransmitter

Gustatory afferent fibres are activated

The signal is transmitted to the brain as bitter taste

Taste transduction: Sweetness

Sweet molecules bind to the sweet taste receptor, a heterodimer of T1R2 + T1R3

This receptor is a G-protein–coupled receptor on the taste receptor cell membrane

Receptor activation stimulates a Gq-like G protein (e.g. gustducin variants)

This activates phospholipase C (PLC) inside the cell

The exact same cascade as bitterness and Umami occurs. The only difference is the receptors.

Why don’t we confuse bitter, umami or sweet tastes if they have the exact same pathway?

Taste receptor cells express either bitter or sweet or umami receptors- not both

Bitter, umami and sweet taste cells connect to different gustatory afferent axons

Central gustatory pathways

Taste cells → gustatory afferent axons → gustatory nucleus (medulla) → ventral posterior medial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus → gustatory cortex.

Taste receptor cells in taste buds detect chemical tastants

• These cells release ATP onto primary sensory neurons (gustatory afferents)

• The sensory neurons carry the signal into the CNS

Cranial nerves carrying taste

• Anterior 2/3 of tongue

• Carried by CN VII (facial nerve – chorda tympani)

• Posterior 1/3 of tongue

• Carried by CN IX (glossopharyngeal nerve)

• Epiglottis and lower pharynx

• Carried by CN X (vagus nerve)

Brainstem relay (first central synapse)

• All gustatory afferents enter the medulla

• They synapse in the gustatory nucleus (nucleus of the solitary tract)

• This is where taste information from all regions is first integrated

Thalamic relay

• Second-order neurons project from the medulla to the ventral posteromedial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus

• The thalamus acts as a sensory relay and filter

Cortical processing

• Third-order neurons project from the VPM to the gustatory cortex

• Gustatory cortex is located mainly in the insula and frontal operculum

• Conscious perception and discrimination of taste occurs here

Overall flow (simplified)

• Taste cell → gustatory afferent

• Cranial nerves VII / IX / X

• Gustatory nucleus (medulla)

• VPM nucleus (thalamus)

• Gustatory cortex

Bitter, sweet, and umami (Type II taste cells)

• Use GPCRs (T2Rs for bitter, T1Rs for sweet/umami)

• Intracellular signalling → Ca²⁺ rise → depolarisation

• ATP is released from the taste cell (via ATP-permeable channels)

• ATP directly activates gustatory afferent fibres

• No classical synapse, no vesicular neurotransmitter release

Salty and sour (Type I & Type III taste cells)

• Use ion channels, not GPCR cascades

• Tastant directly changes membrane potential

• These cells form conventional synapses with afferent neurons

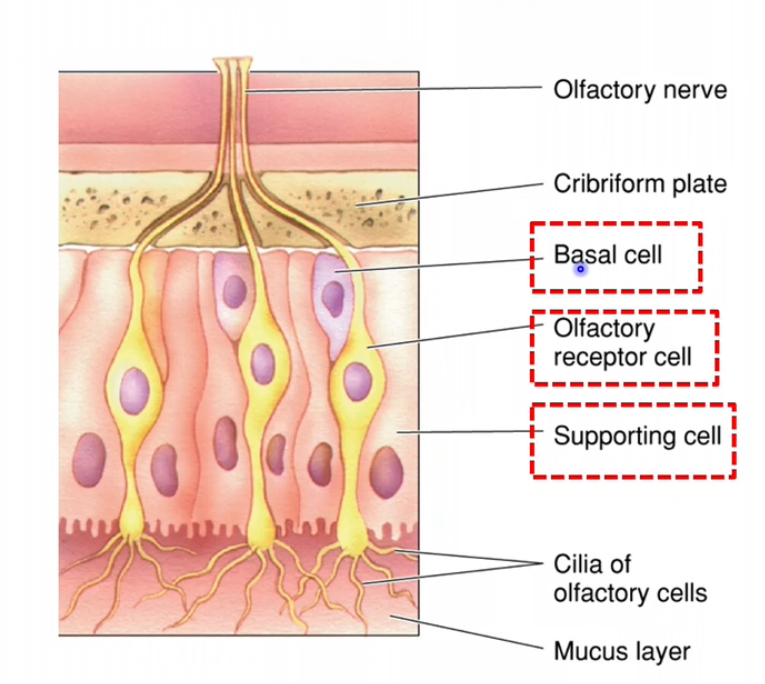

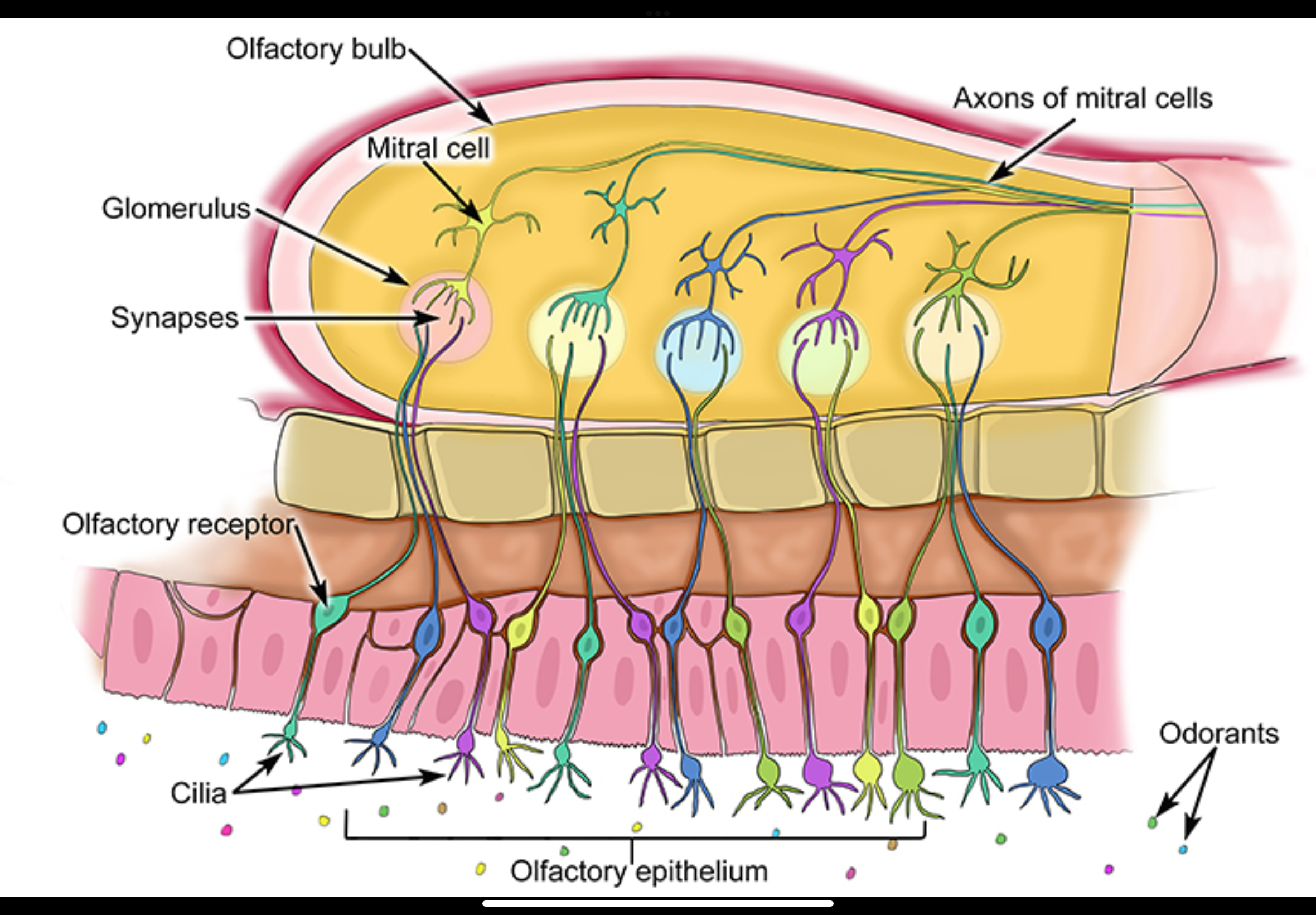

The olefactory epithelium

Olfactory epithelium – 3 main cell types

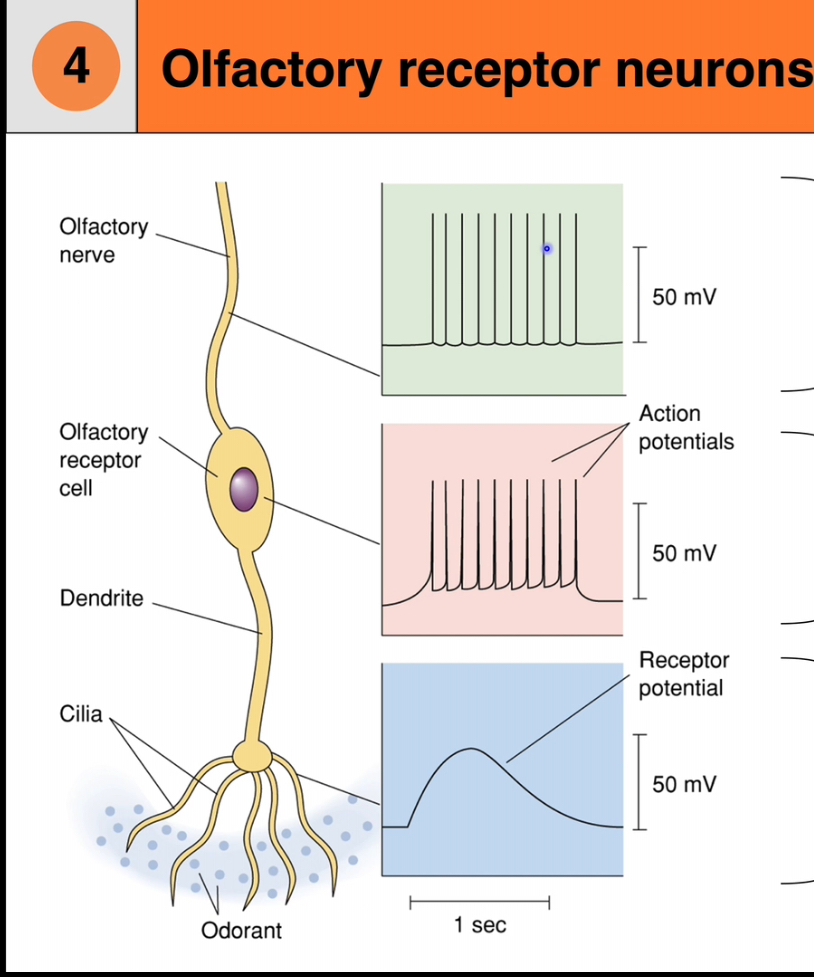

1. Olfactory receptor cells

• These are true neurons, unlike taste receptor cells

• They are the site of transduction for smell

Have cilia where odorants bind

• Axons from these neurons pass through the cribriform plate to the olfactory bulb

Each cell has:

• A dendrite ending in a knob

• Cilia extending into the mucus layer

• Odorant molecules bind to receptors on the cilia and initiate electrical signals

2. Supporting (sustentacular) cells

• Provide structural and metabolic support to olfactory receptor neurons

• Produce mucus

• Odorants must dissolve in mucus before binding receptors

• Help maintain the correct chemical environment for transduction

3. Basal cells

• Act as stem cells

• Continuously divide and differentiate into new olfactory receptor neurons

• Allow the olfactory epithelium to regenerate throughout life

• This regeneration is unusual for neurons and is a key feature of the olfactory system

Pheromones

Smell as a mode of communication (pheromones)

Pheromones are chemical signals detected via the olfactory system

They are used for communication between individuals of the same species

Roles of pheromones in animals

Regulate reproductive behaviours

Used for territory marking

Signal aggression or submission

Coordinate social and survival behaviours

Pheromones in humans

Humans can detect many body-related odours

However, the functional importance of pheromones in humans is unclear

Evidence for strong, behaviour-driving pheromone responses (as seen in other mammals) is limited and debated

Key contrast to remember

Animals: pheromones = clear behavioural signals

Humans: olfaction influences perception and emotion, but pheromone-driven behaviour is not well established

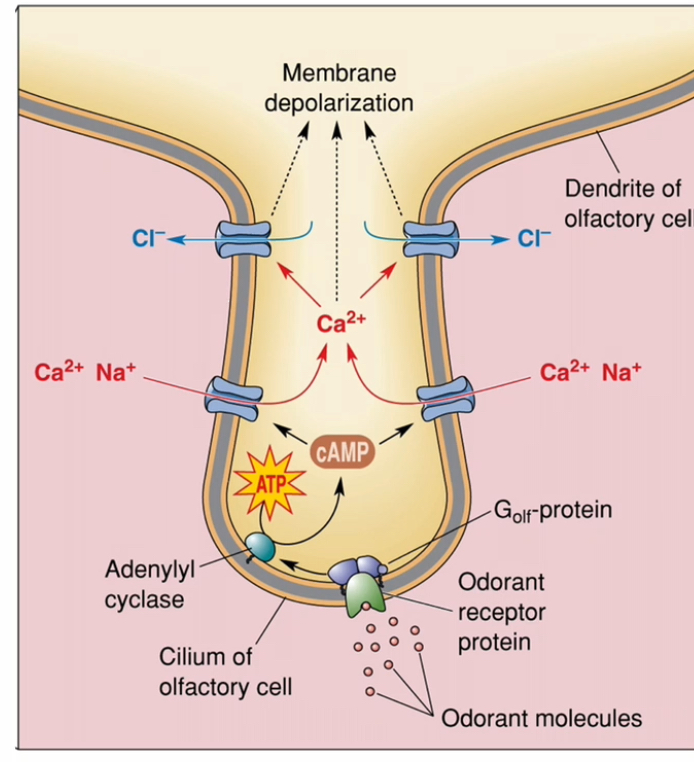

Transduction: Olefactory

Odorant receptor GPCRs located on the olfactory cilia.

Golf (G-olfactory).

Odorant binding

Odorant molecules dissolve in mucus

They bind to odorant receptor proteins on the cilia of olfactory receptor neurons

G-protein activation

Receptor activation switches on the olfactory G-protein Golf

This starts the intracellular signalling cascade

Second messenger production

Adenylyl cyclase is activated

cAMP levels increase inside the cell

Ion channel opening

cAMP opens cation channels

Na⁺ and Ca²⁺ enter the cell

Signal amplification

Incoming Ca²⁺ opens Ca²⁺-activated Cl⁻ channels

Cl⁻ leaves the cell (high Cl⁻ inside olfactory neurons)

This greatly boosts depolarisation

Neuronal response

The membrane depolarises

If threshold is reached, an action potential is generated

The signal travels to the brain as smel

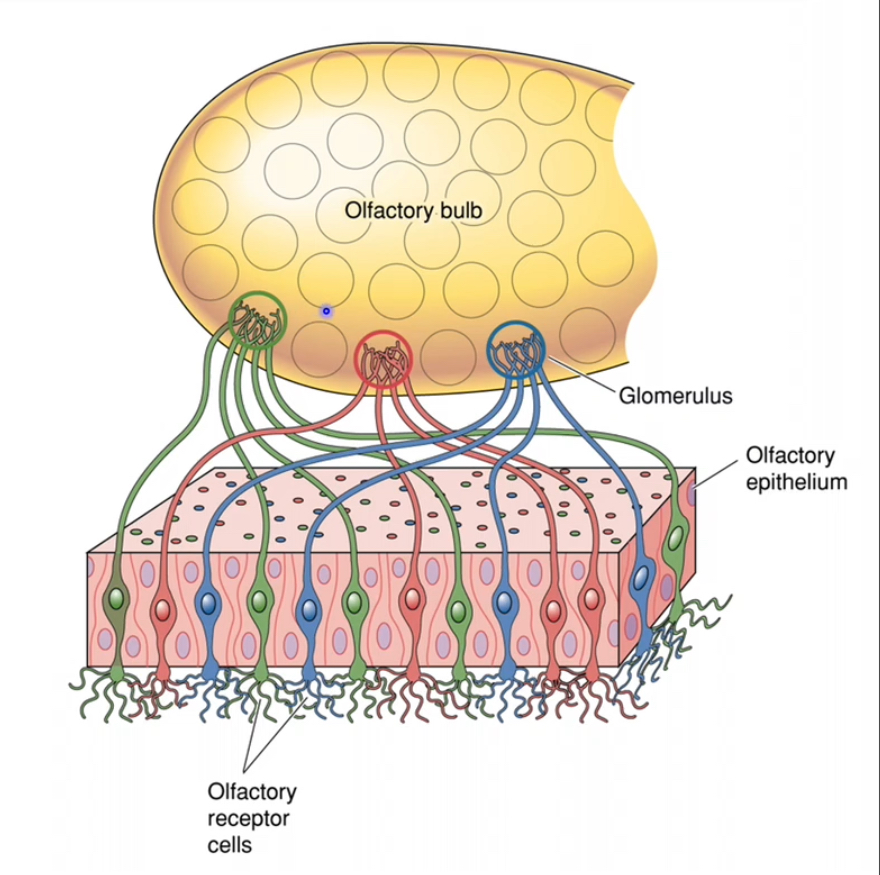

Where do olfactory receptor neuron axons project?

To the olfactory bulb, where they synapse in specific structures called glomeruli.

Odorants activate olfactory receptor neurons in the olfactory epithelium

• These neurons generate action potentials

• Their axons pass directly into the olfactory bulb

Convergence in the olfactory bulb

• Olfactory receptor neurons that express the same receptor type all project to the same glomerulus

• Each glomerulus therefore represents one receptor identity

• This creates a spatial “map” of odor information

Synaptic relay

• In the glomeruli, olfactory receptor neuron axons synapse onto:

• Mitral cells

• Tufted cells

• Glutamate is released at these synapses

Transmission to higher brain areas

• Mitral and tufted cell axons carry the signal out of the olfactory bulb

• Information is sent directly to higher brain regions

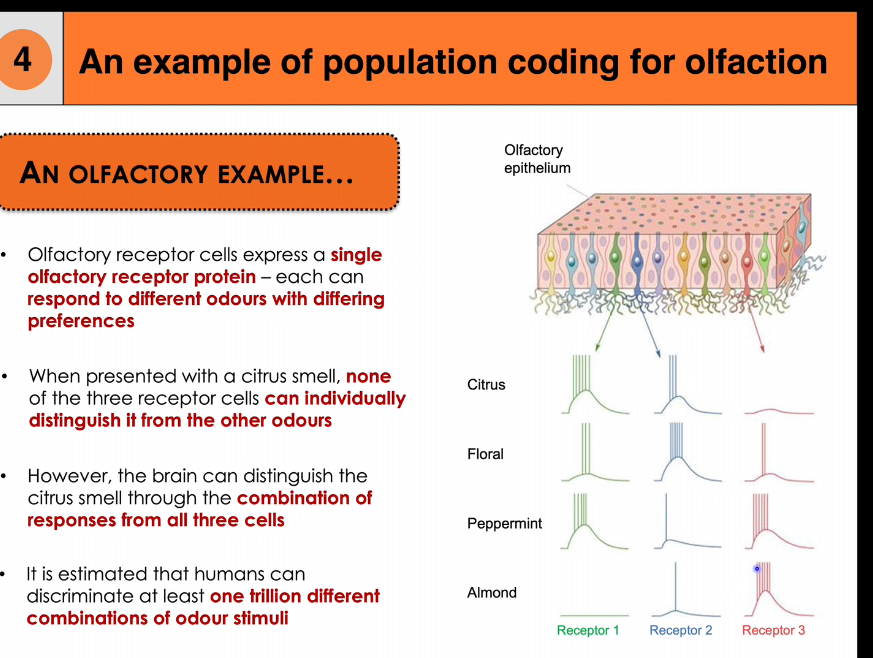

Population coding for gustation and olfactory

Population coding means the brain identifies a stimulus by the pattern of activity across many neurons, not one neuron alone

Population coding in olfaction

Each olfactory receptor neuron expresses one receptor type

Each receptor responds to many odours, but with different strengths

A single receptor cannot identify an odour on its own

Each smell produces a unique combination of responses across many receptors

The brain recognises the smell from this overall pattern

Example (from the diagram)

Citrus, floral, peppermint, and almond each:

Activate Receptor 1, 2, and 3

But in different relative amounts

That difference in pattern = different smell

Population coding in gustation

Taste receptor cells may express one receptor

But downstream neurons respond more broadly

Taste identity depends on combined activity across many neurons

Why this works

Broad tuning + combinations = huge capacity

Allows discrimination of very large numbers of smells and tastes

Smells and tastes are coded by patterns across neuron populations, not single “labelled-line” neurons.

Why can humans discriminate at least one trillion odours?

Because each odour activates a unique combination of receptor types, creating a large number of distinguishable activation patterns through population coding.