Pathology Test 1

1/121

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

122 Terms

What are the 6 Key Steps of disease progression:

Etiology, pathogenesis, morphology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, prognosis.

What is Etiology? include etiologic agents and factors.

Etiology is the identification of factors provoking a particular disease.

- Etiologic agents: specific agent which causes a disease, such as bacteria or viruses.

- One etiologic agent can cause one disease.

- Several etiologic agents can cause one disease.

- One etiologic agent can cause multiple diseases.

- Etiologic factors: contribute to the causing of disease, or influence the disease course, such as age or genetics.

What is Pathogenesis? include an example of what this can look like

- Pathogenesis is the development of the evolution of a disease, including the infection of and damage to the bodies cells which will lead to different symptoms.

- For example, infection via a bacterium can include:

1. Invasion of the host body

2. Proliferation

3. Spreading

4. Infecting and damaging the body’s cells.

5. Triggering an immune response.

What is Morphology?

Morphology is the effect of the disease on the bodies cells and tissues. This could include cell death, inflammation, abnormal cell growth or necrosis.

What is Pathophysiology?

Pathophysiology is the effect of the disease on normal physiological functioning of the body, includes functional impairments of bodily systems resulting from structural damage.

This could include organ damage, biochemical imbalances, or bodily system malfunctioning.

What are clinical manifestations? also what is the difference between signs and symptoms, and what is required in a diagnosis.

- The presentation of disease in a patient.

- Symptoms: the patient’s perception of a change in bodily function. They are difficult to measure and require asking appropriate questions. May include headache, nausea, or fatigue.

- Signs: physical manifestations of a disease which could be measured. This could include pulse rate, breathing rate or wheezing.

- Diagnosis: requires a medical history, physical examination, and/or diagnostic procedures to identify a disease, disorder, or condition.

What is prognosis?

- The likely course or outcome resulting from a disease.

- This could include likelihood of recovery, likelihood of reoccurrence, treatment influence or mortality risks.

What is the difference between incidence and prevalence?

Incidence: The number of newly diagnosed cases of a disease.

Prevalence: the total number of cases of a disease existing in a population, both new and old, allowing determination of a person’s likelihood of having the disease.

What is the difference between morbidity and mortality?

Morbidity: refers to the condition of suffering from a disease or illness. Several co-morbidities can have had by a person.

Mortality: another term for death.

What is an idiopathic disease?

a disease of unknown origin

What is epidemiology?

the study of incidence, distribution, and control of disease in a population.

What is cellular stress, and what are some causes?

- Defined as any change or stimulus which disrupts cellular homeostasis.

- Causes of cellular stress can include:

-Physical agents like temperature

-Chemical agents like pH

-Microorganisms like bacteria

-Hypoxia - lack of oxygen to the tissues

-Free radicals – molecules with unpaired electrons in outer shell. Can enter key molecules in cell membranes or nucleic acids and cause damage.

What does the cell do in response to stress and why?

Make cellular adaptations in order to maintain homeostasis.

What are the 5 key types of adaptations made by the cell in response to stress?

Atrophy: Reductions in cell size undergone by cells if they are underused or undersupplied.

Hypertrophy: Increases in cell size undergone by cells if they are utilised more.

Hyperplasia: Increases in cell numbers, but only in cells which are able to multiply.

Metaplasia: Changes in cell type based on the demands placed upon a cell.

- Transitional epithelium can become stratified squamous in bladder due to bladder stones.

Dysplasia: Changes in cells and cellular arrangements to become abnormal and irregular.

- It is pre-cancerous or pre-neoplastic.

When do reversible cell injuries occur and the two key ones?

They occur when cells are placed under stress, and adaptations no longer allow the maintenance of homeostasis.

Cellular swelling: water accumulation in the cell due to inadequate ATP leading to malfunctioning of the sodium potassium pump, causing excess sodium into the cell, and attracting water by osmosis. This could occur due to blood blockages, preventing oxygen and nutrient access, is reversed by normal pump functioning.

Cellular accumulation: the accumulation of substances inside the cells (such as fat inside the liver) due to that substance being found in too high concentrations. This can be reversed often with lifestyle changes.

When do irreversible cell injuries occur and what are the three key types?

They occur when the stress placed on a cell causes an irreversible injury, which leads to cell death.

Necrosis: the death of a cell due to a pathological condition. Leads to cell enlargement and loss of membrane integrity, causing leaking of cell contents, triggering an inflammatory response.

Infarction: cell death caused by a lack of oxygen, either anoxia (complete lack), or hypoxia (reduced). This is caused by thrombosis (blood clot), embolism (foreign object) or atherosclerosis (plaque), all of which block the bloodstream.

Apoptosis: programmed cell death when a cell reaches the end of its lifecycle. The cell shrinks and nuclear fragmentation occurs. Apoptopic bodies bud off and phagocytosis occurs, meaning the cell is engulfed.

What are the 6 types of necrosis?

Coagulative: occurs due to reduced blood supply, such as an embolism, where cell and organ shape are preserved, but internal contents are damaged.

Liquefactive: digestion of dead cells by neutrophils releasing lysosomal enzymes to form a viscous mass containing dead cells, debris and water. A cavity remains once fluid is drained, meaning tissue shape is not preserved.

Caseous: caused by fungal infections, where the infected area is surrounded by WBCs, causing dead tissue to become soft, white and crumbly. Tuberculosis.

Fat: the death of fat cells due to enzymes or trauma. death of fat cells can release lipase, causing further death, where free fat then binds to calcium (saponification).

Fibroid: blood vessel walls become damaged, causing fibrin and proteins to deposit on the wall, causing vessel to lose elasticity and become thicker.

Gangrenous: organ or tissue death. it occurs due to ischema (lack of blood supply) and commonly occurs in peripheral regions.

What are neoplasms and how are they formed?

An abnormal growth unresponsive to normal control mechanisms.

Proto-oncogenes (normal genes) become mutated to form oncogenes, which are cancer-causing.

Name 3 factors which can cause cancer

UV radiation, carcinogens, cigarette smoke,

What are the two types of tumours

Benign: non-cancerous masses which do not spread to other parts of the body.

Malignant: cancerous masses characterised by uncontrolled growth and the ability to spread.

How are benign and malignant neoplasms named?

Benign: Suffix ‘-oma’. Some exceptions include lymphoma and melanoma which are malignant.

Malignant: Suffix ‘-carcinoma’ (epithelium) or ‘-sarcoma’ (connective tissue)

What are the anatomical differences between benign and malignant tumours?

Benign:

Smooth and round with a symmetrical shape and a uniform cut surface.

Encompassed in a capsule.

Slow growing with no metastases.

No necrosis or haemorrhage.

Closely resemble normal cells.

Malignant:

Stellate, irregular shape with a non-uniform cut surface.

No defined capsule.

Rapid growth with lymphatic or vascular invasion.

Necrosis or haemorrhage can occur.

Dont resemble normal cells.

Describe the rapid growth of cancer cells

Tumour cells divide more rapidly than other cells. Tumor cells secrete their own growth factor, meaning that the more cells there are the more rapidly they divide. The continual division of tumour cells increases growth rate.

Describe the process of epithelial malignancy

The nucleus darkens (dysplasia)

Fully malignant cells develop, but the basement membrane remains in tact (carcinoma in situ)

Malignant cells invade the basement membrane, but no lymphatic or vascular invasion occurs (early invasive carcinoma)

The invasion of blood vessels or lymphatics with metastasis can then occur.

Describe what well vs poorly differentiated cancer cells indicate.

Well Differentiated: generally resemble normal cells with slight abnormalities, and generally grow and spread slower.

Poorly Differentiated: show little structural resemblance to normal cells, and generally grow and spread more aggressively

Describe 4 key abnormalities of cancer cells

Proliferate even when space is not available.

Make and respond to own growth factors (removed from feedback control).

Lose normal adhesion for easy metastasis

Can closely resemble normal cells to avoid immune system

Describe 4 structural characteristics of cancer cells

Large, variably shaped nuclei

many cells in disorganised arrangements

Vary in shape and size

Loss normal cellular features

What is metastasis? what stage is metastatic cancer?

The invasion of cancer cells at different locations, occurring when cancer cells spread to a different part of the body from where they started via clumps of malignant cells which have broken off into the interstitial fluid.

- Metastatic cancer is considered stage 4.

Describe the process of metastasis

tumour cells invade capillaries.

They are carried by platelets in the bloodstream.

They invade a new tissue.

Divide and replicate in the new tissue.

Capillaries supply the new tissue via release of tumor-angio-genesis factors.

What are common sites of metastasis

Brain, liver, lung, adrenals, bone.

What are the key symptoms of cancer?

Cancer symptoms year depending on the location and extent of the tumour, but can include:

Pain

Cachexia: weight loss

Bone marrow suppression

Anaemia

Leucopoenia: low white blood cells

What are the key symptoms during cancer treatment?

Hair loss

Sloughing of mucosal membrane

Opportunistic infections

How are tumours graded, and what are the three gradings.

Tumours are graded based on histological characterisation, using cell size and appearance to determine degree of anaplasia, losing differentiated characteristics to become primitive.

Grade I - well differentiated

Grade II - moderately differentiated

Grade III - poorly differentiated

What does tumour staging describe, and describe the three categories.

Describes the location and pattern of spread of a tumour within the host.

Tumor size - 0 (no tumour) to 3 (large tumour)

Lymph node involvement - 0 (no nodal involvement) to 2 (invasion of fixed nodes)

Metastasis - 0 (none), 1 (metastasis occurred), X (suspected metastasis)

Describe the terms antigen, antibody and autoantibody.

Antigen: a molecule which can be recognised as non-self by the immune system to trigger an immune response.

Antibody: a protein which binds to antigens to recognise, neutralise, and destroy.

Autoantibody: an antibody which mistakenly targets the bodies own proteins.

Describe the differences of basophils and mast cells.

Basophil: a white blood cell found in the blood which releases histamine in an immune response.

Mast Cell: a white blood cell found in the tissues which releases histamine in an immune response.

Describe the difference between monocytes and macrophages

Monocyte: a circulating white blood cell which enters tissues to develop into a macrophage.

Macrophage: a large phagocytic cell which engulfs pathogens and cell debris.

Describe the function of T and B lymphocytes, and plasma cells.

T Lymphocyte: white blood cells in adaptive immunity which carry out an immune response.

B Lymphocyte: white blood cells which produce antibodies and become plasma cells.

Plasma Cell: activated B cells which secrete large amounts of specific antibodies.

Describe the difference between antigen presenting cells and cytotoxic cells.

Antigen presenting Cell: process and display antigens in order to activate T cells.

Cytotoxic Cell: kill virus infected or cancerous cells.

What is hypersensitivity?

Excessive or inappropriate activation of the immune system due to exposure to exogenous and endogenous antigens, causing inflammation and tissue damage.

Describe the difference between Exogenous and Endogenous antigens

Exogenous antigens: a foreign substance which enters the body.

Endogenous antigens: produced inside cells via metabolism or in response to infection.

What is autoimmune disease and some examples

- When a person’s own immune system produces an inappropriate response against own cells, tissues, or organs.

- Examples include; rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis.

State and describe the four classes of hypersensitivity

Type I – Immediate

- IgE antibodies are inappropriately produced.

- Leads to anaphalaxis, allergies or asthma.

Type II – Cytotoxic

- IgM or IgG antibodies attack own cells or tissues.

- Leads to autoimmune disease or incompatible blood transfusions.

Type III – Immune Complex

- Large antigen-antibody complexes are circulating with IgM or IgG antibodies.

- This leads to tissue inflammation and damage.

- Leads to systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Type IV – Cellular (Delayed)

- Instigated by T-lymphocytes.

- Leads to contact dermatitis or tuberculosis.

What is anaphylaxis and describe the process

- A severe type I reaction which is systemic and can lead to widespread vasodilation and oedema, which can lead to anaphylactic shock.

1. The initial foreign antigen is exposed to B lymphocytes.

2. The stimulates B lymphocytes (plasma cells) produce specific IgE antibodies.

3. IgE antibodies attach to and sensitize mast cells (and basophils), known as antigen neutralisation.

4. A subsequent antigen exposure occurs.

5. Antigens react with sensitised mast cells and basophils by binding to antibodies on the cell membrane, causing degranulation.

6. Chemicals like histamine in mast cells are released, causing:

-Bronchiole constriction

-Blood vessel vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, decreasing blood volume and blood pressure.

7. This leads to shortness of breath and wheezing, as well as low blood pressure and tissue welling.

8. These factors can lead to shock, where the heart does not have enough blood to supply oxygen to bodies tissues.

Describe the symptoms of anaphylaxis

- Allergy symptoms can appear mild or moderate, but progress quickly.

- The most dangerous allergic reactions involve the respiratory and cardiovascular systems.

- Other common signs and symptoms include:

-Hives or body redness.

-Swelling of the face, lips, and eyes.

-Vomiting or abdominal pain.

-Mouth tingling

What is treatment for anaphylaxis

- Allergic reactions require immediate action.

- An intramuscular adrenaline (epinephrine) injection is given using an adrenaline autoinjector.

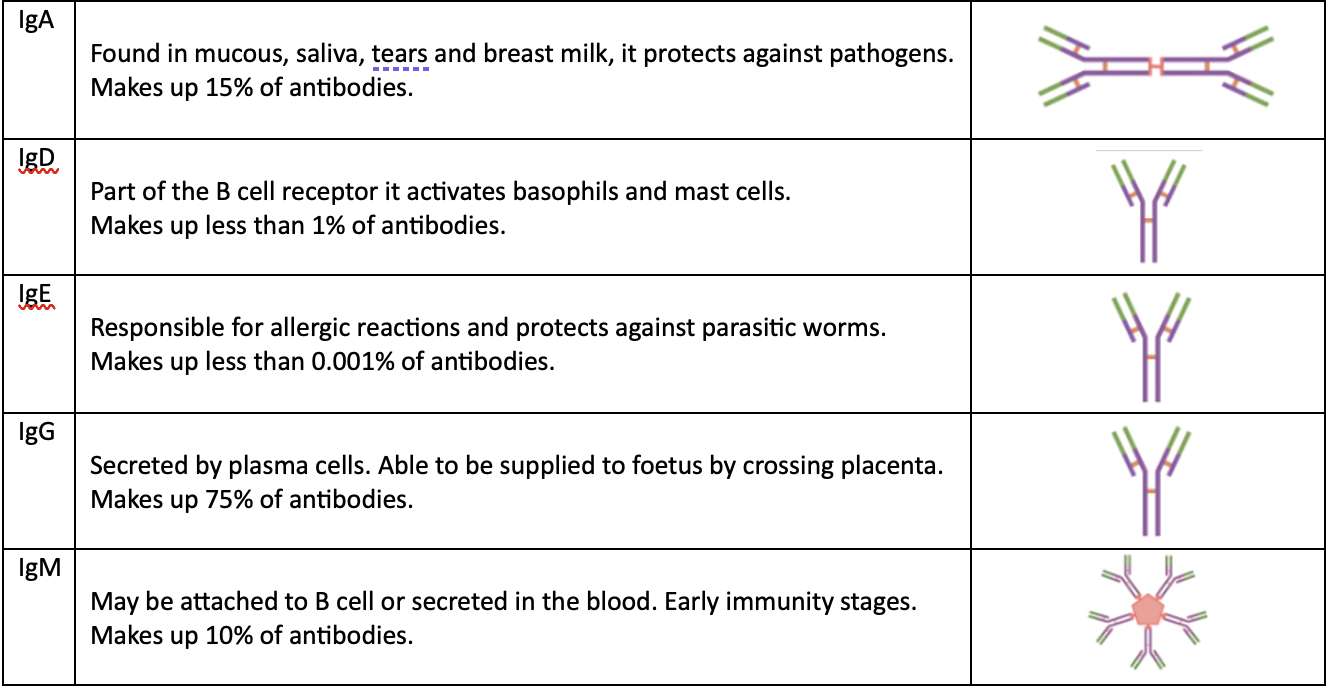

What are the 5 classifications of antibodies

What is the structure of an antibody.

Antibodies contain a light and heavy chain, with an antigen binding site on the end.

What are infectious agents, and some examples.

Microogranisms which can cause disease by invading the body.

They include viruses, bacteria, unicellular parasites (protozoa), multicellular paracites or fungi.

What are bacteria, their structure, and mode of replication

- Unicellular organisms.

- Their structure includes:

-A rigid cell wall made of peptidoglycan.

-No organised intracellular organelles.

-A single DNA chromosome.

-Cell surface structures to allow host attachment and motility.

- They reproduce via mitosis, simple cell division.

What are the 3 formats of classifying bacteria, and the classifications for each?

- Classification by shape:

- Cocci: rounded

- Bacilli: rod-shaped

- Spirochetes: tightly spiralled

- Classification by oxygen requirements:

- Anaerobic: oxygen is toxic

- Aerobic: require oxygen to survive and replicate

- Classification by gram staining:

-Purple-staining: contain more peptidoglycan in bacterial walls.

-Pink-staining: contain less (10%) peptidoglycan in bacterial walls.

What are viruses and their structure

- A non-living collection of molecules.

- They are smaller than bacteria and require living hosts to survive.

- They contain no organised cell structure.

- There are both RNA and DNA viruses.

- They can be either single-stranded or double-stranded.

How do viruses enter cells

1. Penetration of the host cell via endocytosis or fusion with the cell membrane.

2. Insertion of genome into host cell genome (as RNA or DNA) providing instructions to make virus copies.

3. The host cell sheds viral replicants which infect other cells.

4. The host cell dies, and the virus is released by budding off.

What are fungi

- Free living eukaryotes with a nucleus and organelles within the membrane.

- Can be unicellular (mould) or multicellular (mushrooms)

- Few can produce disease in humans.

- Most infections are incidental, self-limiting infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue.

- Infections are only life-threatening in ill or immunosuppressed patients.

What are parasites and the two classifications

- Include protozoa, arthropods, and helminths.

- They are a major problem in developing countries with poor hygiene.

- In Australia, most cases come from travel.

- They infect and cause disease in animals, from where they can be transmitted in humans.

- They are shed in infected animal faeces as cysts or pores, which are ingested by humans in contaminated food or water.

- They can also be carried by arthropod vectors, or transmitted by close contact.

Two types: protozoa and multicellular parasites.

What is infection and infectious disease?

Infection: when pathogenic microorganisms can invade a host, attach, and multiply within the tissues.

Infectious Disease: when a host organ sustains injury or pathologic damage in response to an infection.

Describe the beneficial microorganisms in the human body?

Normal Flora

- Microorganisms which establish permanent residence in or on the body without causing disease.

- They acquire nutritional needs and shelter from the host.

- They are found on the skin or mucous membranes of the body’s openings.

- Blood, lymph, spinal fluid, and most organs do not contain any organisms.

- Bacteria in the bowel extract nutrients from the host and secrete essential vitamin by-products of metabolism, like vitamin K and B.

- They can stimulate anybody production, maintain the bodies pH, and prevent pathogenic entry by occupying space.

- If a course of antibiotics kills normal flora pH can be altered, and fungi can flourish, causing thrush.

What are opportunistic infections

- Opportunists: pathogens capable of producing disease when the health or immunity of the host is weakened by illness or medical therapy.

- This occurs commonly with HIV/AIDS

What are 6 sources of infection?

- Endogenous: internal sources such as the body’s own natural flora.

- Exogenous: external or environmental sources such as water or food.

- Nosocomial: a hospital inquired infection.

- Other humans: diseases can be spread between people.

- Animals: diseases can be transmitted from animals to humans, as in rabies.

What are 5 methods of infectious spread within the body

-Local spread

-Lymphatic spread

-Haematogenous spread (bloodstream)

-Tissue fluid spread

-Neural spread

What are the three lines of defence in the body

First Line of Defence

- Consists of epithelial barriers, including the skin and mucous membranes.

- They physically prevent the entry of pathogens into the body.

Second Line of Defence

- A non-specific or innate response.

- Consists of WBCs, tissues, and organs which work together to protect the body.

- They are responsible for inflammation, as the actions can cause tissue damage.

Third Line of Defence

- A specific or adaptive response.

- Consists of B and T lymphocytes.

- It differentiates between microorganisms and reponds accordingly.

- It can produce a heightened response upon re-exposure.

What are the key functions of inflammation?

-Limiting the extent and severity of the damage.

-Eliminating and neutralising the damaging agent.

-Initiating repair of an injury.

What is acute inflammation

- The response to short-term injury which lasts a few hours to days.

What are the cells involved in acute inflammation

- The cells involved are granulocytes responsible for innate immunity:

- Neutrophils responsible for phagocytosis

- Basophils responsible for histamine release to attract inflammatory cells.

- Eosinophils involved in allergic reactions and response to parasitic invasion.

What are the two phases of acute inflammation:

-The vascular phase where histamine causes vasodilation.

-The cellular phase where endothelial cells contract, allowing neutrophils and plasma to pass to the injury site.

-Together, these phases cause the formation of inflammatory exudate, which causes tissue edema.

What are the local signs and systemic manifestations of acute inflammation:

- Local signs include:

-Redness due to vasodilation.

-Swelling due to increased capillary permeability.

-Heat due to vasodilation.

-Pain due to swelling placing pressure on nerve endings, and bradykinin and prostaglandins sensitizing nerves.

-Loss of function due to swelling and pain.

- Systemic manifestations

-Fever

-Increased white blood cells

-Tachycardia

What is inflammatory exudate and the 4 types

- Inflammatory exudate is any fluid filtering from the circulatory system into lesions or areas of inflammation.

- There are four types of inflammatory exudate:

-Serous: contains fluid but little proteins, such as a blister.

-Purulent: contains pus, with many neutrophils, such as an abscess.

-Fibrinous: contains fibrin, the protein which forms fibrous mesh in blood clotting, such as pericardial injury.

-Haemorrhagic: RBC leakage due to severe tissue injury and vessel damage.

What are the possible outcomes of acute inflammation

-Resolution: damage is neutralised, and dead cells regrow.

-Abscess: local accumulation of oedema, necrotic debris, and pus.

-Scarring: tissue damage leads to scar tissue formation.

-Chronic inflammation: the persistent damaging agent leads to continued inflammation.

What is chronic inflammation

- The response to long-term injury which lasts weeks to years.

- Continuous injury, inflammation, and repair occur simultaneously.

What are some physiological factors occurring in chronic inflammation

- Angiogenesis occurs, the formation of new blood vessels.

- Fibrosis (scarring) also occurs.

What are the cells involved in chronic inflammation

- The cells involved are agranulocytes, involved in adaptive immunity:

- Monocytes responsible for phagocytosis, as well as being antigen presenting cells.

- Lymphocytes including B and T cells, which are specific immune cells.

What are 3 potential causes of chronic inflammation?

- Persistent infection such as mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Autoimmune Disease such as rheumatoid arthritis.

- Persistent exposure to damaging agents, such as cigarette smoking.

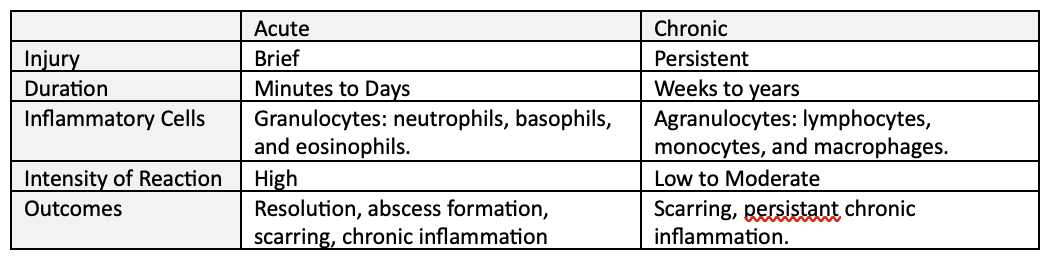

What are the differences of acute and chronic inflammation (injury, duration, cells, intensity, outcomes)

Describe the repair of three cells types from inflammation:

Labile Cells: Continuously Dividing

- Complete regeneration is possible, quick, and easy due to the short lifespan of cells.

- New cells are formed from continuously reproducing stem cells.

- Eg. Epithelial cells lining the skin.

Stable Cells: Some Division

- Complete regeneration of these cells is possible when triggered by stress or injury.

- Eg. Parenchymal cells of the kidneys.

Permanent Cells: No Division

- These cells are highly differentiated and are unable to regenerate as they have left the cell cycle.

- Injury results in scarring, as healing occurs via repair.

- Eg. Neurons

What are some factors affecting healing?

- Age

- Nutrition

- Blood Supply

- Infection

- Immune status

- Wound separation

- Concurrent diseases and treatments.

when does healing by first intention occur, and describe the process

- Occurs in narrow wounds with closely positioned edges.

1. A narrow incision is made.

2. Mitotic cell division occurs, fibroblasts make new connective tissue and new capillaries form via angioneogenesis. - While healing the tissue is called granulation tissue

3. Scar tissue is formed.

when does healing by second intention occur, and describe the process

- Occurs in broad wounds with widely separated edges.

1. A deep, wide injury occurs, causing necrosis of the epidermis and dermis.

2. Inflammation occurs with haemorrhaging.

3. Mitotic cell division occurs, with fibroblasts making new connective tissue, and new capillaries form via angioneogenesis occurs. The tissue while healing is called granulation tissue.

4. A wide scar forms containing collagen fibres.

What are the two categories of haematological disorders

- Anaemia: decreased haemoglobin concentrations in the blood.

- Leukemia: uncontrolled proliferation of leukocytes.

What is the structure of red blood cells

- Has a concave shape

- The peripheral portion is thicker.

- The central portion is thinner.

- This shape helps to increases its surface area.

- It also contains haemoglobin molecules.

What is the structure of haemoglobin

Haemoglobin is made of 4 heme groups bound to the protein globin.

- The protein globin contains 4 polypeptide chains.

- Heme groups contain iron and carry oxygen throughout the body.

What is anaemia and the two causes?

- Characterised by decreased haemoglobin concentrations in the bloodstream.

- This can either be due to:

-Decreased number of whole red blood cells.

-Decreased concentrations of haemoglobin in red blood cells.

What are the three key effects of anaemia on the body?

-Hypoxia: deficiencies in the amount of oxygen reaching the tissues.

-Hypoxaemia: abnormally low oxygen concentrations in the blood.

-Cyanosis: bluish skin tone due to poor blood circulation or oxygenation.

What are 3 key factors affecting blood volume and RBC concentration

- Production failure: production relies on erythropoietin release by kidneys, nutritional intake of iron, B12, and folic acid, and functioning of the bone marrow.

- Haemolysis: the destruction of red blood cells.

- Haemorrhage: loss of blood volume

What are the general signs and symptoms of anaemia and their causes?

- Due to decreased haemoglobin (Hb) levels: pallor of skin, conjunctivae, mucous membranes and nail beds.

- Due to decreased oxygen and tissue hypoxia: fatigue, weakness, headache, dizziness, or shortness of breath.

- Due to compensatory mechanisms to increase oxygen delivery:

-Tachycardia or palpations: increased heart rate

-Tachypnoea: increased breathing rate

-Bone pain: increased red blood cell production in the bone marrow.

What is haematocrit and what is it used for

- Haematocrit is used for the diagnosis of anaemia.

- It refers to the percentage of blood made up by red blood cells.

- It is measured as a blood sample is centrifuged to separate red blood cells, from which the portion of red blood cells in the blood can be measured.

- 47 – 52% of blood made up by red blood cells is normal.

- A lower red blood cell concentration indicates anaemia.

- A higher red blood cell concentration indicates polycythaemia.

What are the 5 types of anaemia

Iron deficiency anaemia

B12 or folate deficiency anaemia

Aplastic anaemia

Post-Haemorrhagic anaemia

Haemolytic anamia

What is iron deficiency Anaemia

- Caused by decreased iron intake, excessive blood loss, and/or increased iron demands.

- These factors mean there is less iron available to produce haemoglobin, reducing the capacity of the bloodstream to transport oxygen to the body’s tissues.

What are the steps of the iron cycle

1. Dietary iron is consumed through the diet.

2. Iron is absorbed and transported into the plasma.

3. In plasma, transferrin binds to iron and transports it.

4. Excess iron is transported to the liver and stored as ferritin.

5. Iron can be released from the liver when required.

6. Iron is used for the formation of red blood cells in the bone.

7. After 120 days, red blood cells are destroyed in the spleen, and iron can be released from haemoglobin in order to be recycled.

How does low iron impact red blood cell formation?

- Low iron means that haemoglobin synthesis will be inhibited, due to iron being a key component of haemoglobin.

- This leads to the production of smaller, haemoglobin poor erythrocytes.

What is the impact on cells in iron deficiency anaemia

Blood cells become smaller (microcytic) and paler (hypochromic) due to reduced haemoglobin concentrations.

What is vitamin B12 / folate anaemia

- Vitamin B12 and folic acid are require for the maturation of red blood cells.

- A deficiency in these nutrients can lead to macrocytic, large or megaloblastic red blood cells, as well as a low count of red blood cells.

- Pernicious anaemia is caused by a deficiency in vitamin B12 or folic acid.

Describe the absorption of vitamin B12 in the diet

1. Vitamin B12 is absorbed through the diet.

2. Intrinsic Factor is secreted by parietal cells in the stomach.

3. Vitamin B12 binds to intrinsic factor in the stomach.

4. This allows it to be absorbed across epithelium in the ileum.

5. B12 can then be utilised by the bodies systems.

What effect does B12 and folate deficiencies have on blood cell production?

- Folate and vitamin B12 are required for DNA synthesis in red blood cells.

- Deficiencies in these vitamins will hence lead to delays in nuclear maturation and division.

- This causes the cell to become immature, and larger as it remains in the growth phase rather then replicating.

What effect does B12 and folate deficiency have on cells

There are fewer red blood cells, and the present red blood cells are larger.

What is aplastic anaemia

- Characterised by the failure of haematopoietic stem cells.

- This leads to decreased numbers of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- The red blood cells are normocytic (same size) and normochromic (same haemoglobin and colour).

- Causes can include radiation, chemotherapy, drugs, viruses, and autoimmune disease.

What is post-haemorrhagic anaemia?

- Decreased number of red blood cells caused by severe acute blood loss.

- The remaining cells are normocrytic and normochromic.

- It can also be caused by chronic blood loss, which will eventually lead to iron deficiency anaemia.

- This is because the loss of blood will reduce the amount of recycled iron available for use, causing cells to become microcytic and hypochromic.

What is haemolytic anaemia + state the two types

- Characterised by chronic increased destruction of red blood cells, leading to shortened lifespan of red blood cells.

- Blood cells can be destroyed prematurely in the spleen or in blood vessels.

- This leads to increased reticulocyte (immature red blood cell) count, and can cause splenomegaly.

Sickle cell anaemia + thalassemia

What is sickle cell anaemia

- A disorder where red blood cells become stiff, and sickle shaped.

- This means they don’t carry oxygen efficiently and become stuck in blood vessels.

- This causes them to be destroyed, mostly in the spleen but also in blood vessels.

What is thalassemia

- Characterised by defective α- or β- globin chains in haemoglobin.

- This leads to the unstable production of red blood cells, meaning mnay precursors die, and surviving cells are destroyed due to abnormalities.

- Minor: mild to moderate symptoms. Major: severe symptoms.

What are the 3 kinds of blood cancers

Leukaemia: The uncontrolled proliferation of leukocytes beginning in the blood and bone marrow.

Lymphoma: Malignant neoplasms of lymphocytes which begin in the lymph nodes and other tissues.

Multiple Myeloma: A malignant neoplasm of plasma cells which starts with plasma cells in the bone marrow.