N2NN3 - Care Scenario: Living with Chronic Pain (Back Pain, Fibromyalgia, Juvenile Arthritis)

1/106

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

107 Terms

RNAO - Best practice guideline: Pain: Prevention, assessment and management (pp. 10-11, 64, 80-87)

Recommendations & Good Practice Statements

Screening & Assessment:

- It is good practice for all health providers to conduct initial and ongoing screening and assessment for pain with people in their care. Pain assessment includes a comprehensive, evidence-based assessment using a person- and family-centred care approach

Management:

- It is good practice to provide an integrative approach to pain prevention, assessment and management. An integrative approach (i.e. non-pharmacological and/or pharmacological strategies) includes individualized, person- and family-centred care

Interprofessional Practice:

- It is good practice for health service organizations and health systems to implement an interprofessional practice approach to pain prevention, assessment and management

Recommendation Question #1: Should organizational or health system implementation of a specialized interprofessional pain care team be recommended or not?

- The expert panel suggests that health service organizations provide access to a specialized interprofessional pain care team for the prevention, assessment and management of pain for people experiencing acute or chronic pain

- It is good practice for academic institutions to provide comprehensive education for students entering health professions on pain prevention, assessment and management

Recommendation Question #2: Should interactive education on pain prevention, assessment and management strategies for students entering health professions be recommended or not?

- The expert panel suggests that academic institutions implement interactive education for all students entering health professions on pain prevention, assessment and management

- It is good practice for health service organizations to provide interprofessional and discipline-specific education for all health providers on comprehensive pain prevention, assessment and management

Recommendation Question #3: Should interactive education on pain prevention, assessment and management for health providers be recommended or not?

- The expert panel suggests that health service organizations implement opportunities for interactive education for all health providers on pain prevention, assessment and management

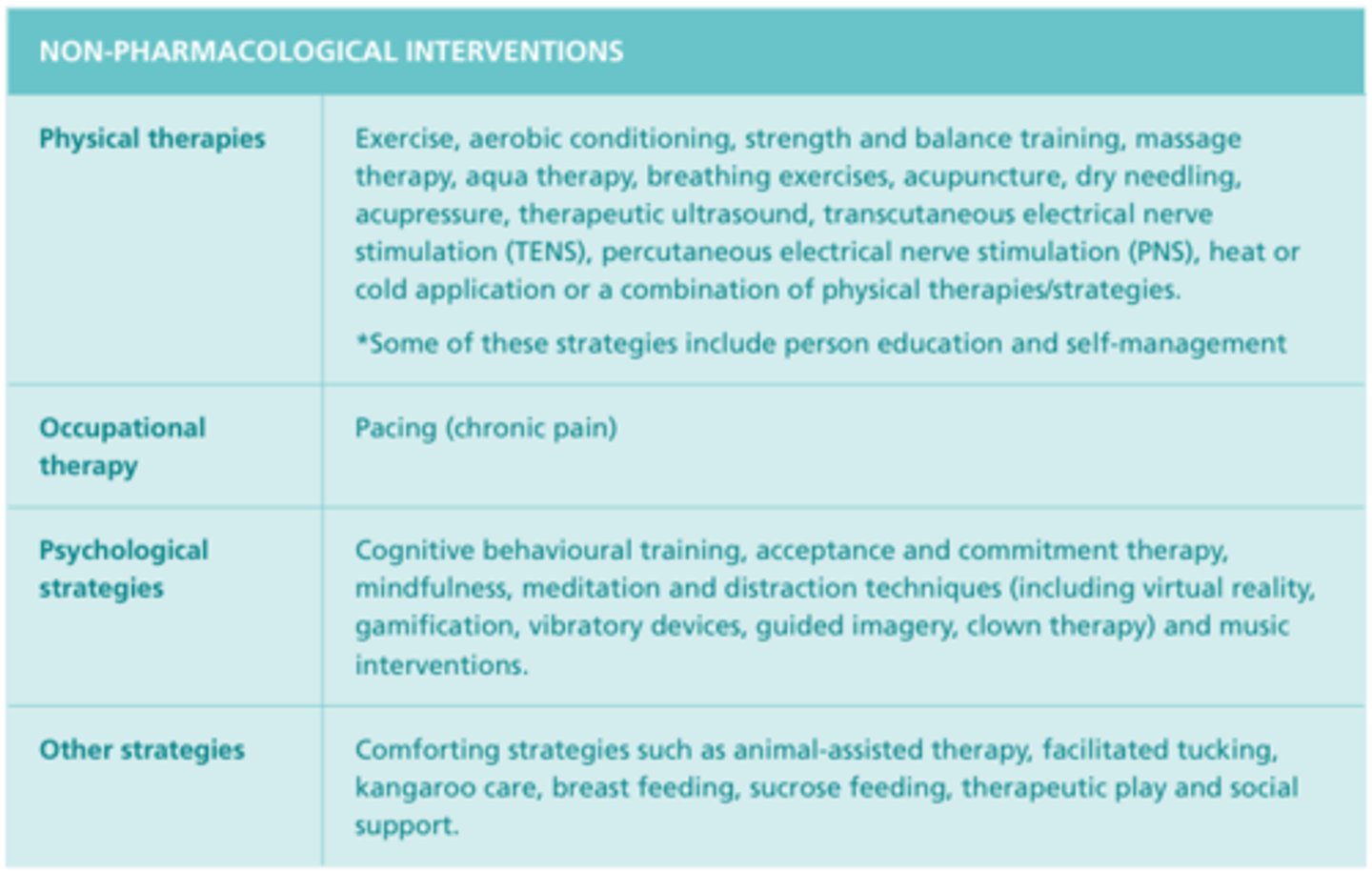

Non-Pharmalogical Interventions for Pain

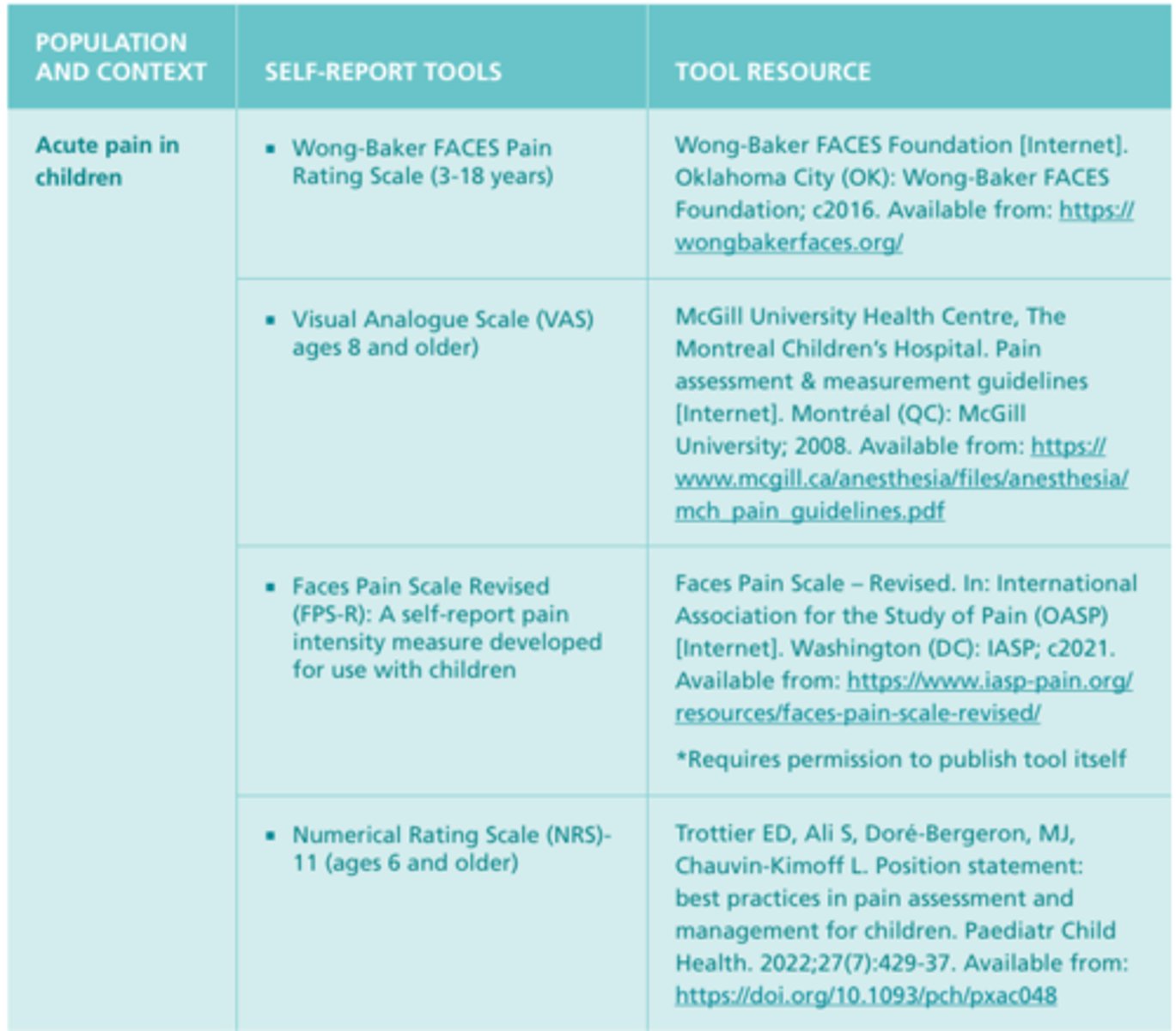

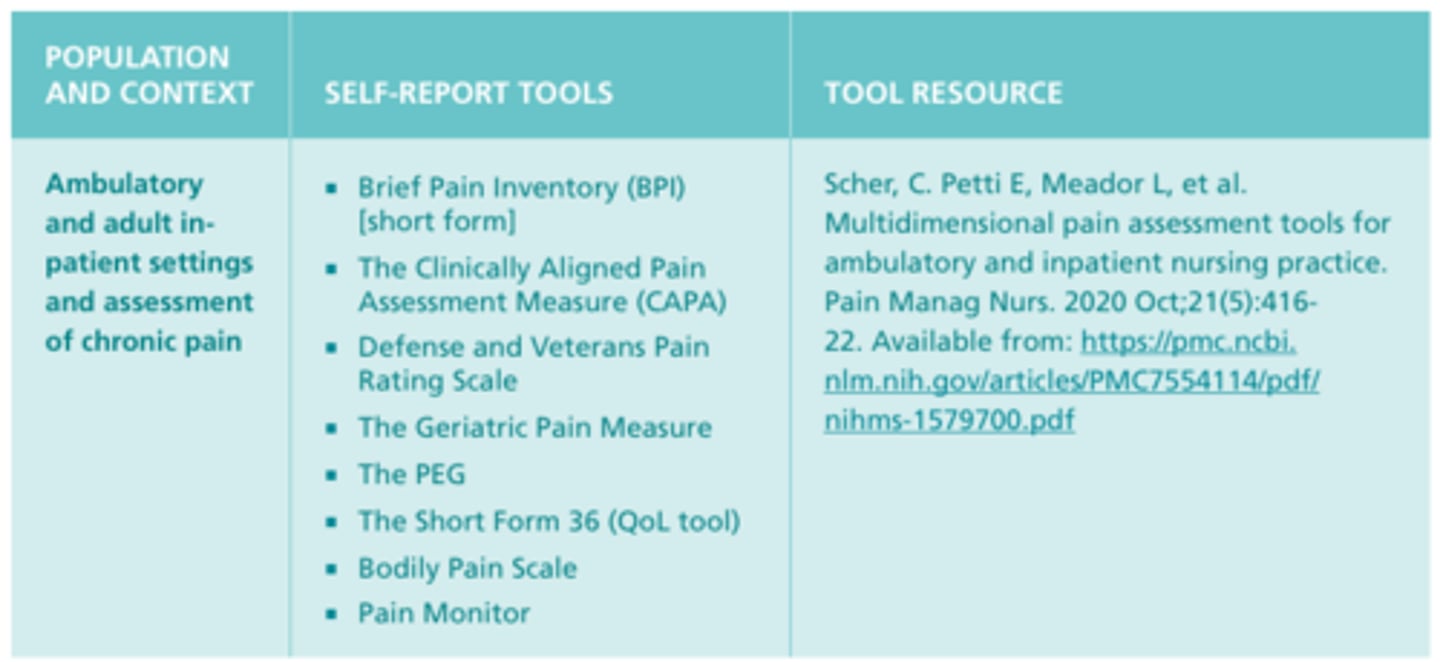

Self-Report Pain Scales or Tools #1

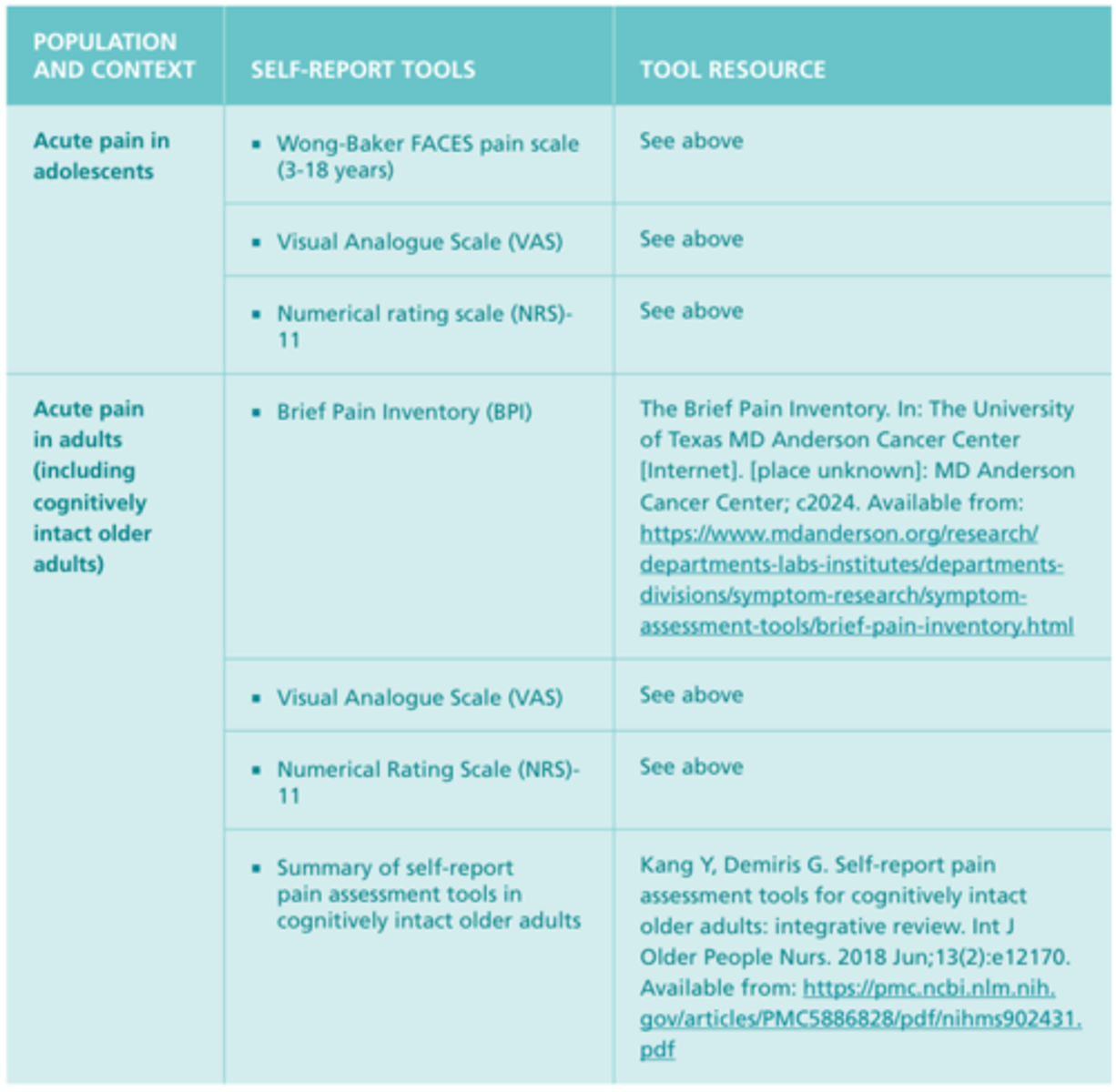

Self-Report Pain Scales or Tools #2

Self-Report Pain Scales or Tools #3

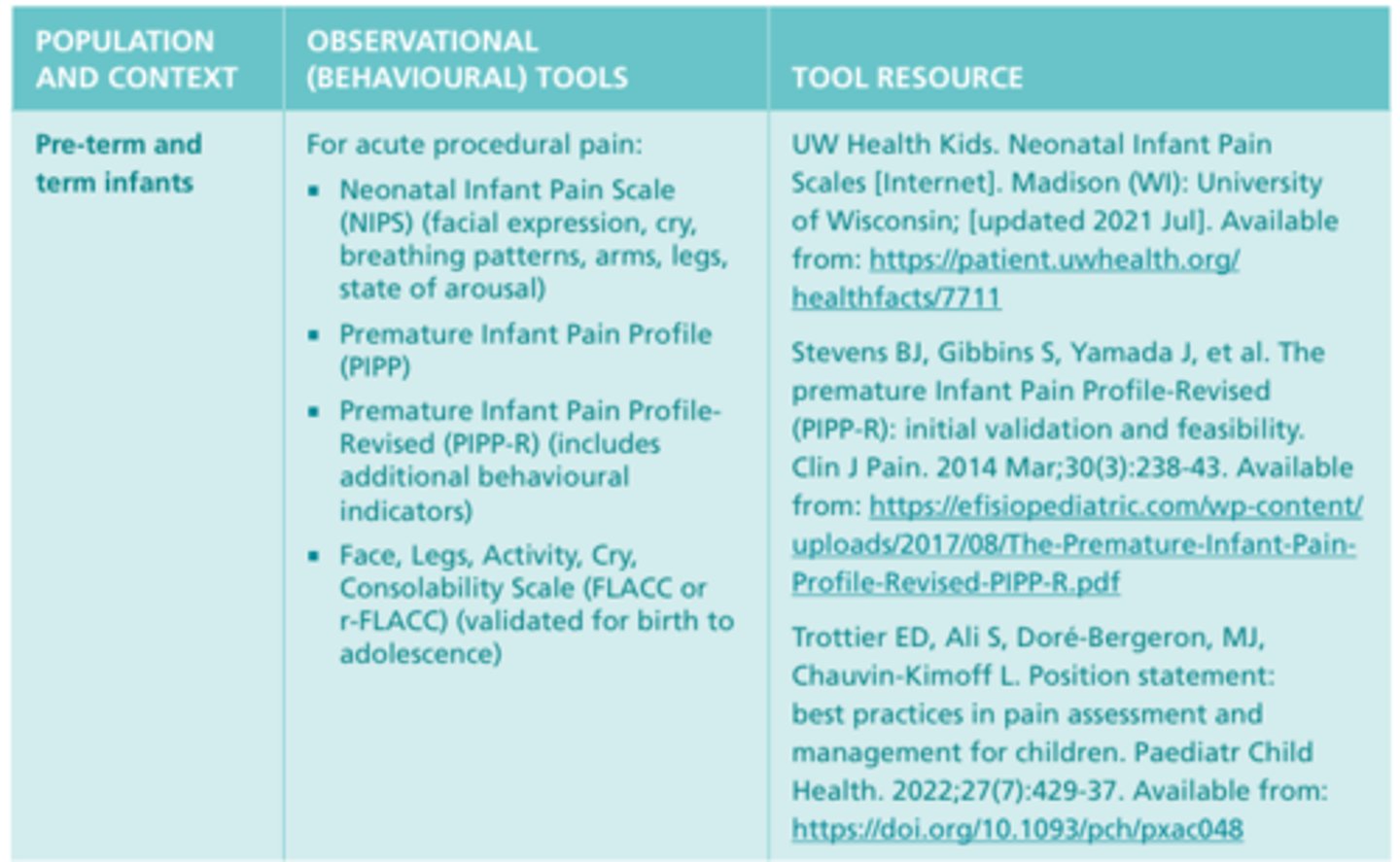

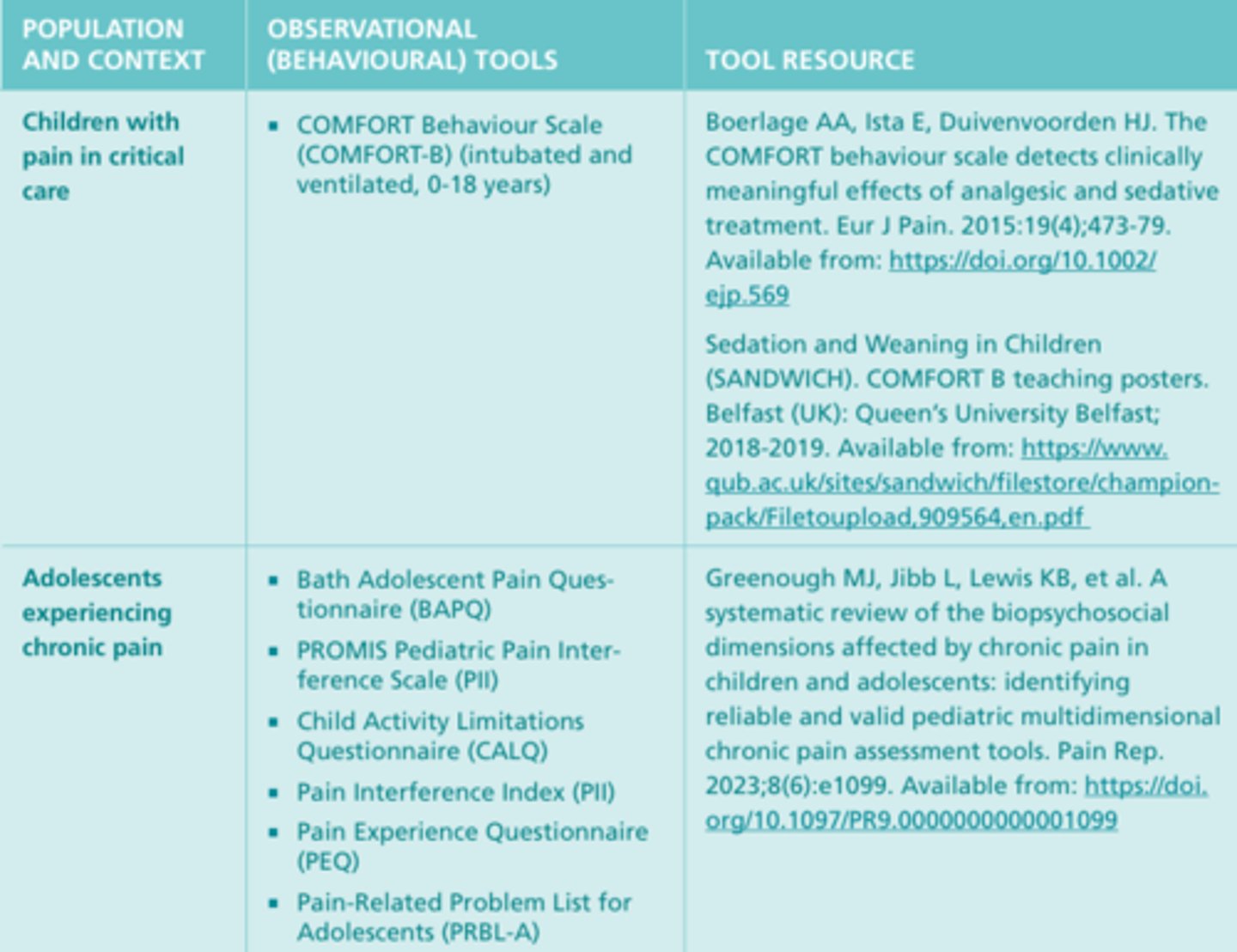

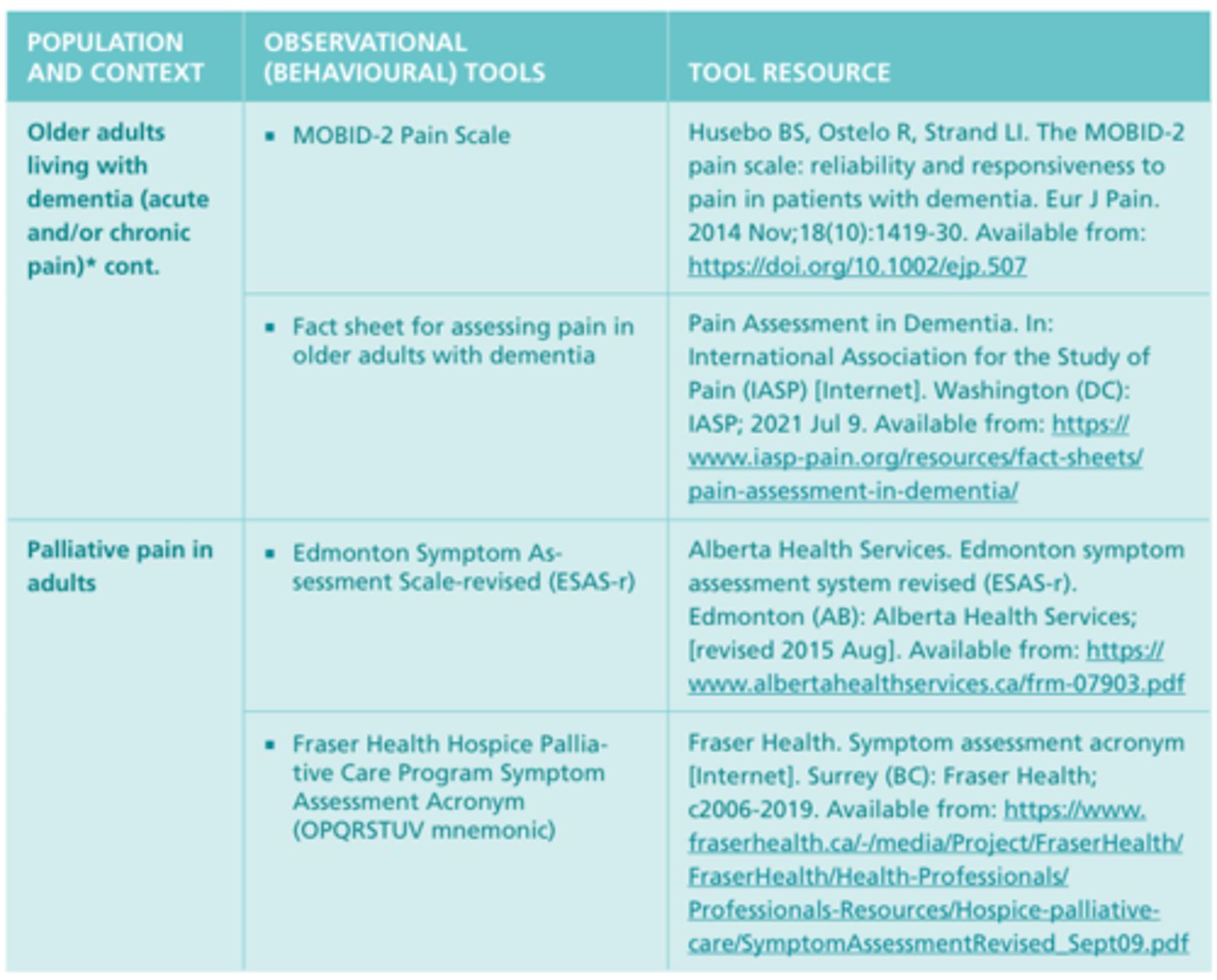

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #1

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #2

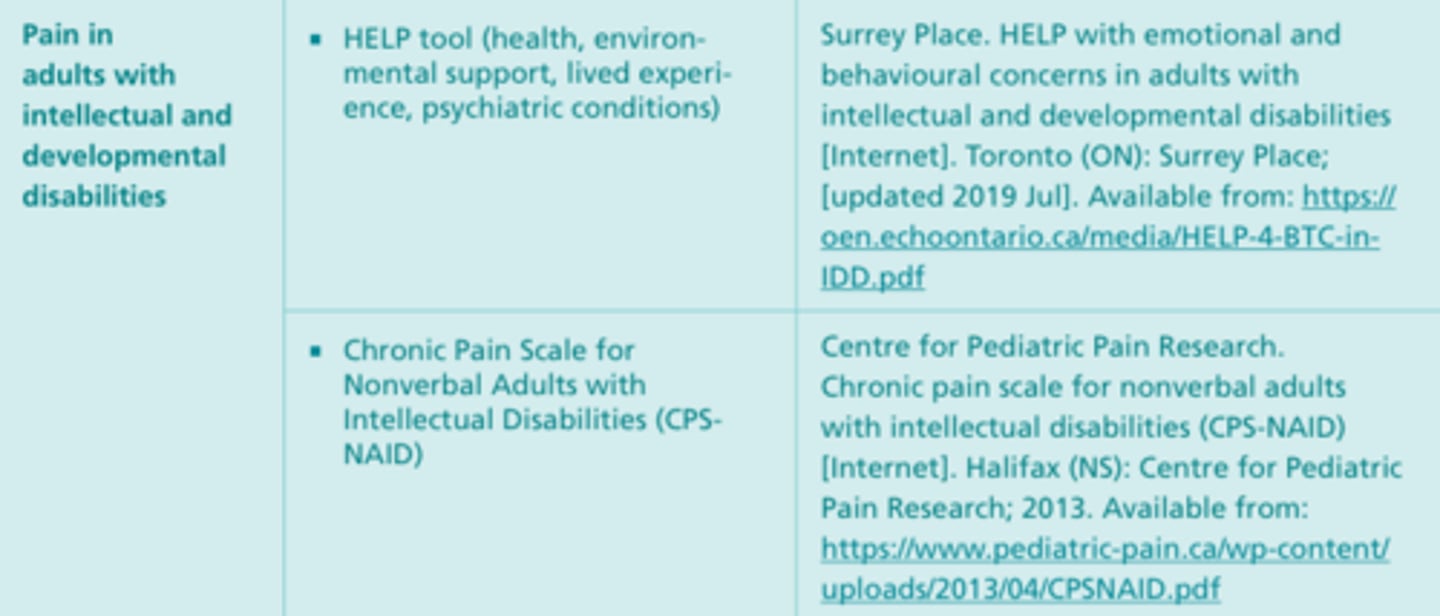

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #3

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #4

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #5

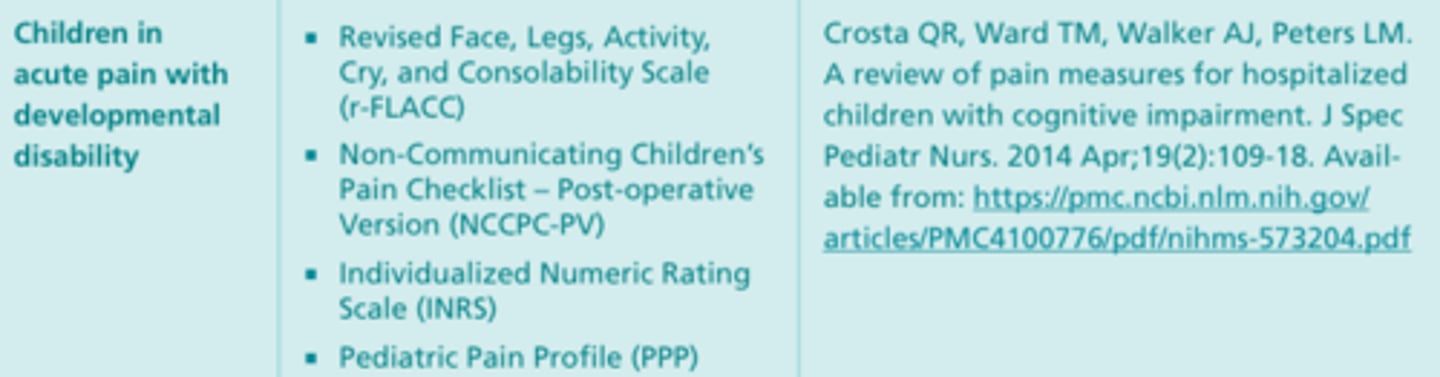

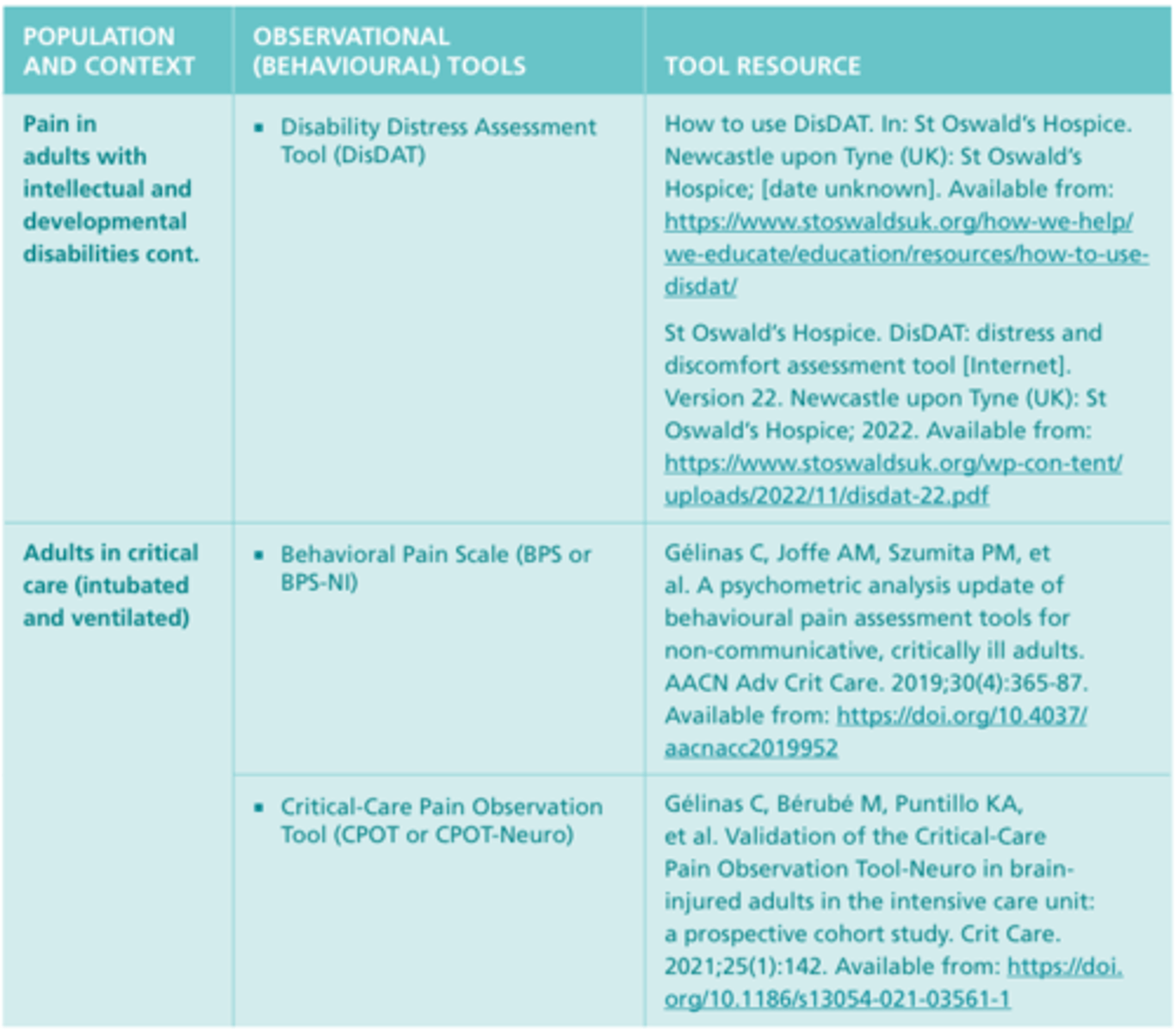

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #6

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #7

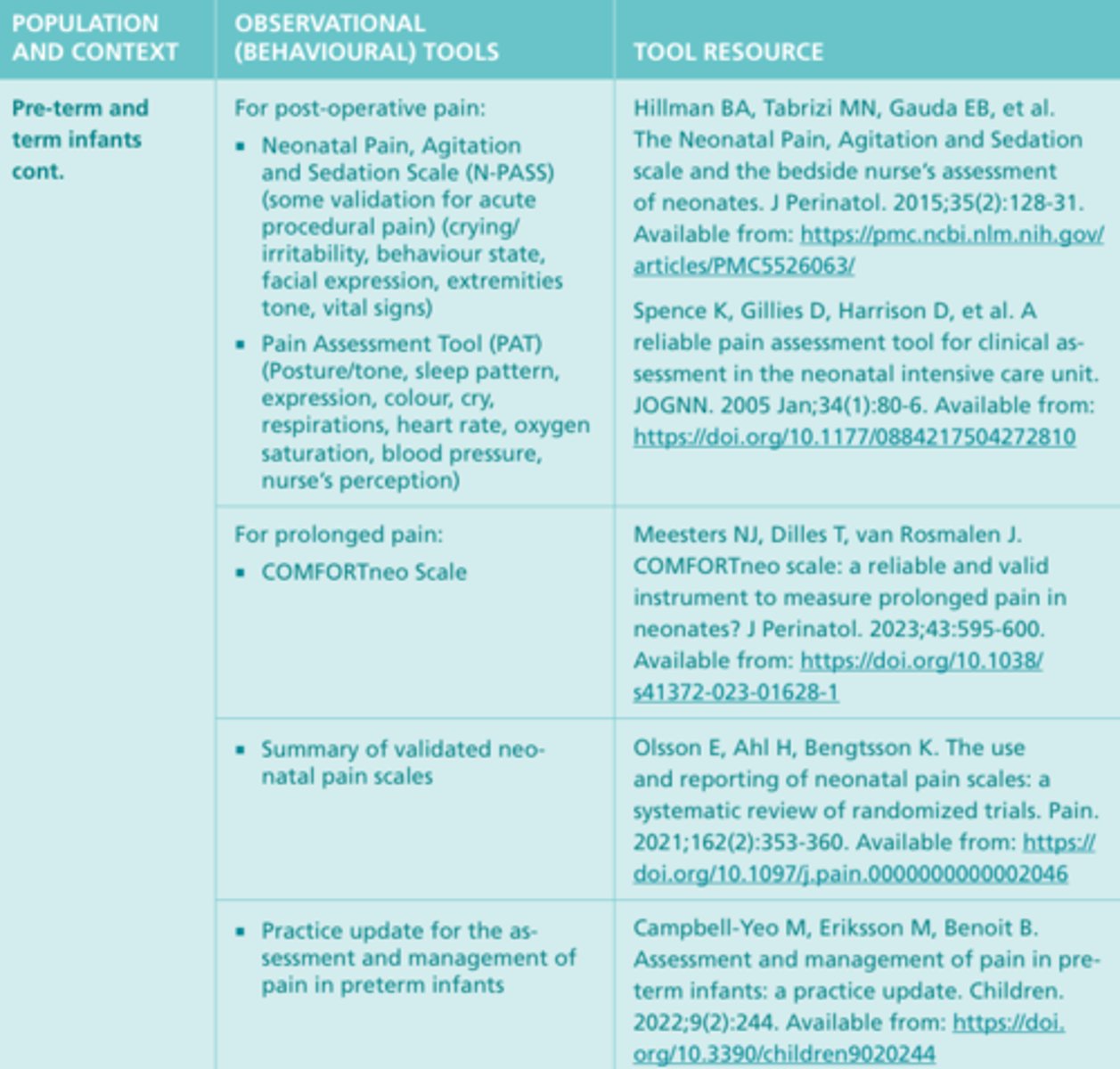

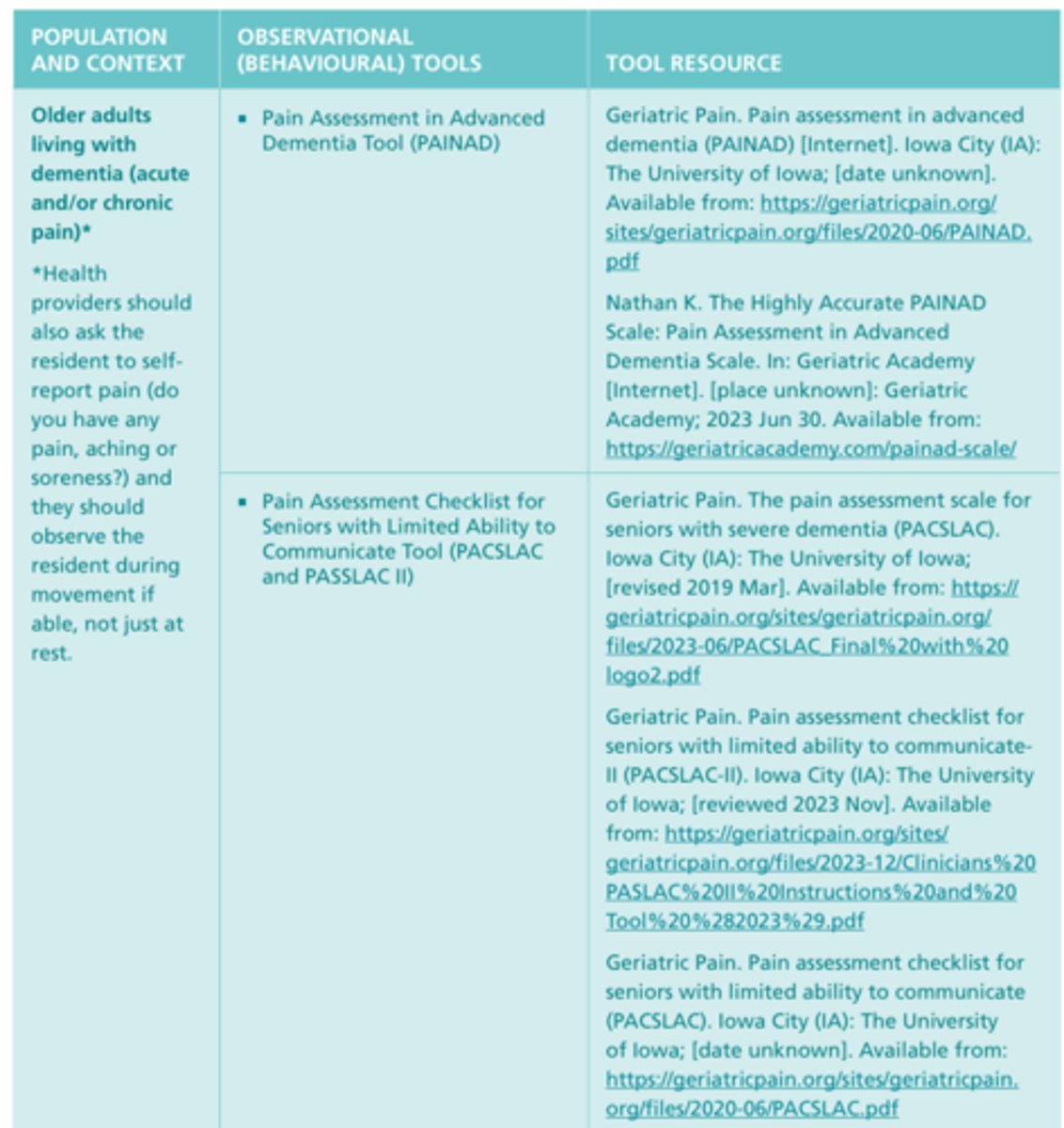

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #8

*With above

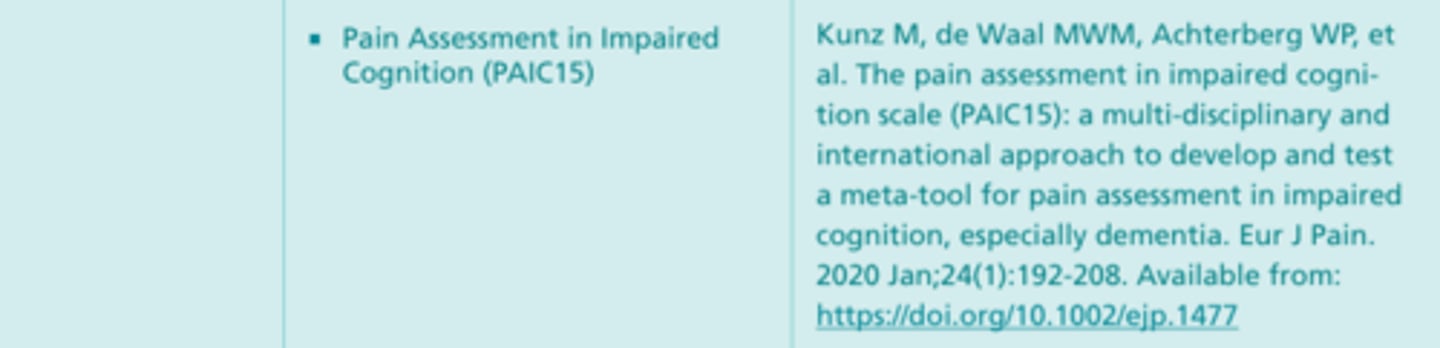

Observational (Behavioral) Tools #9

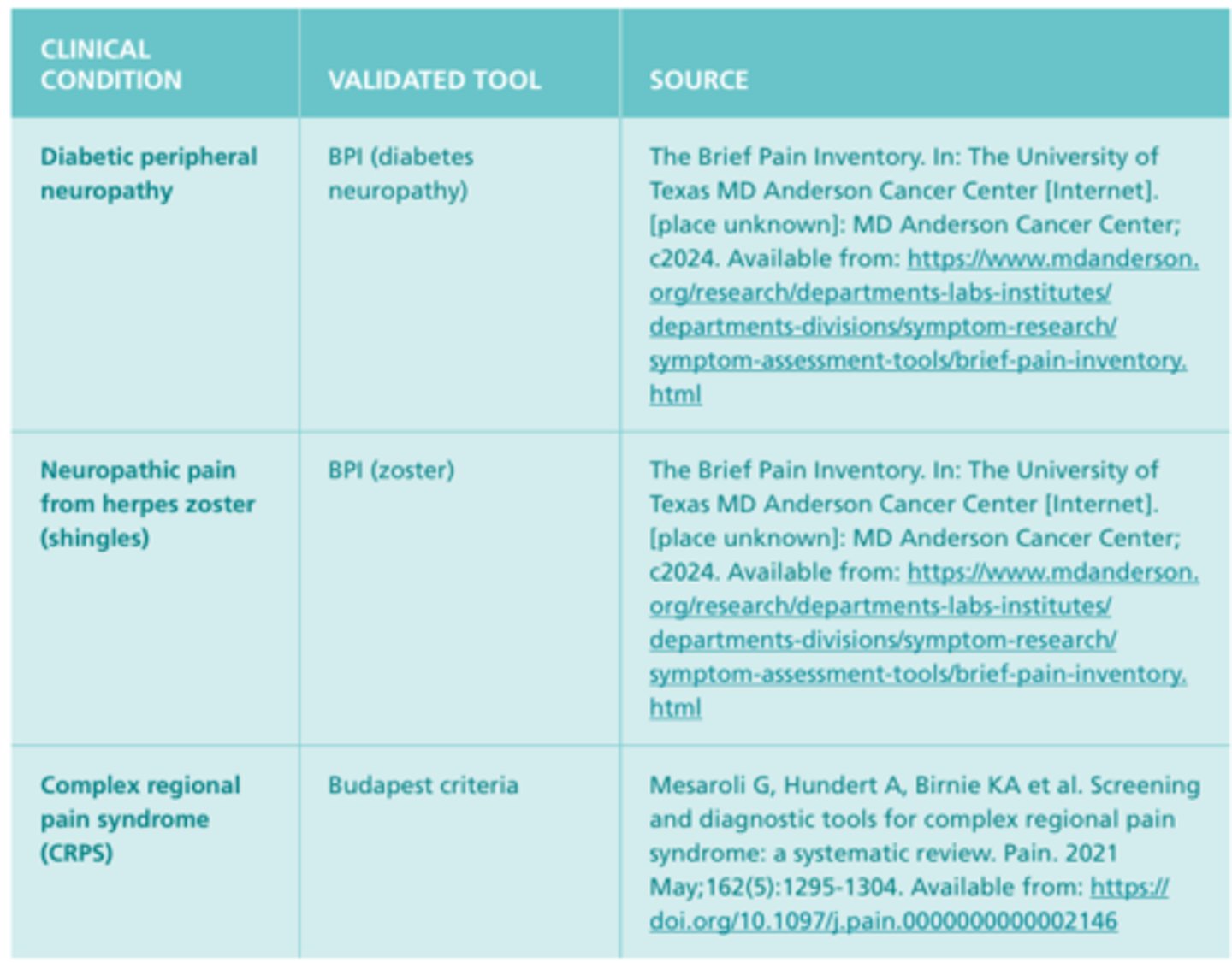

Additional Pain Tools

Med-Surg Textbook - Assessment & management of Clinical Problems (pp. 141-160)

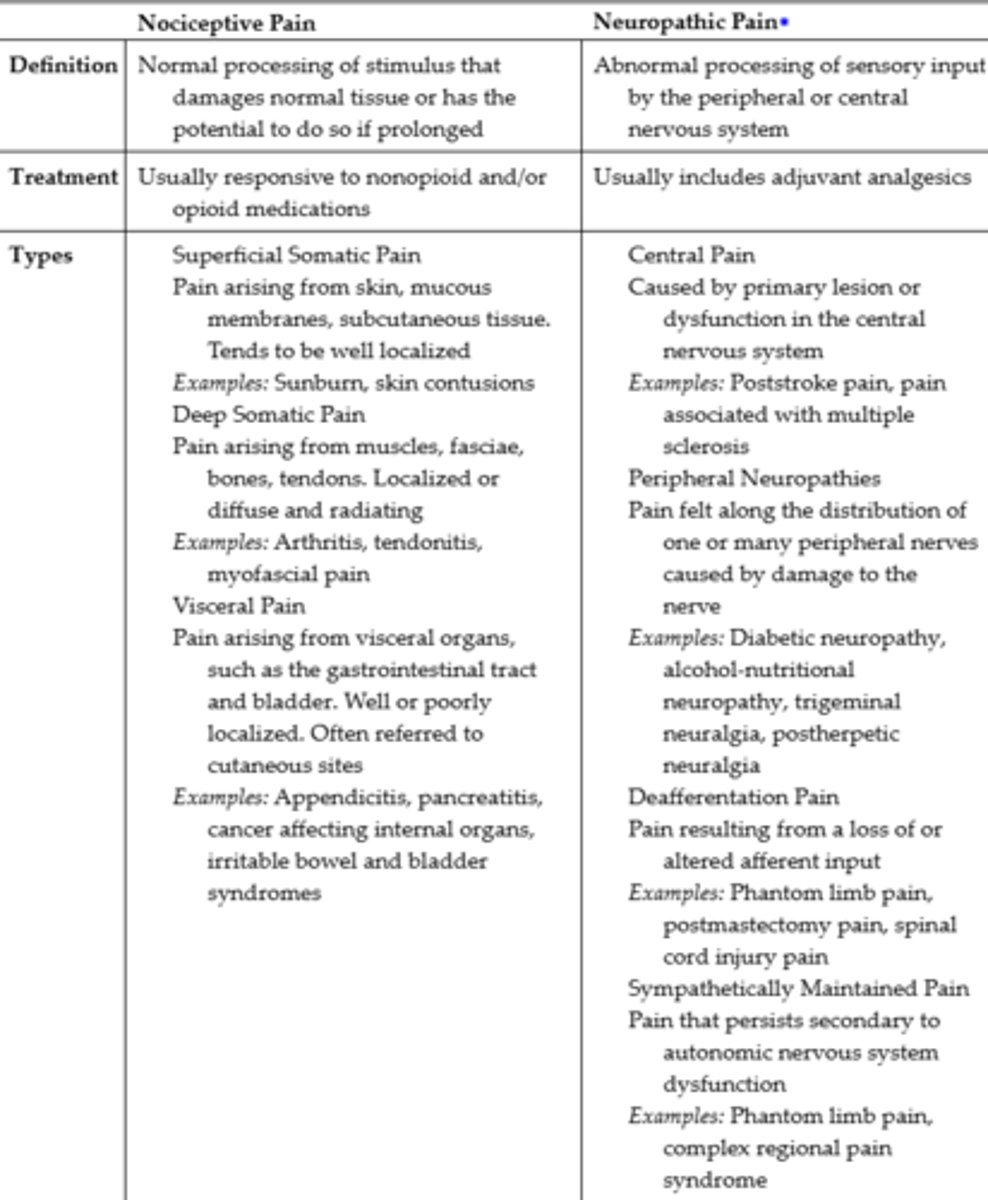

Nociceptive vs. Neuropathic Pain

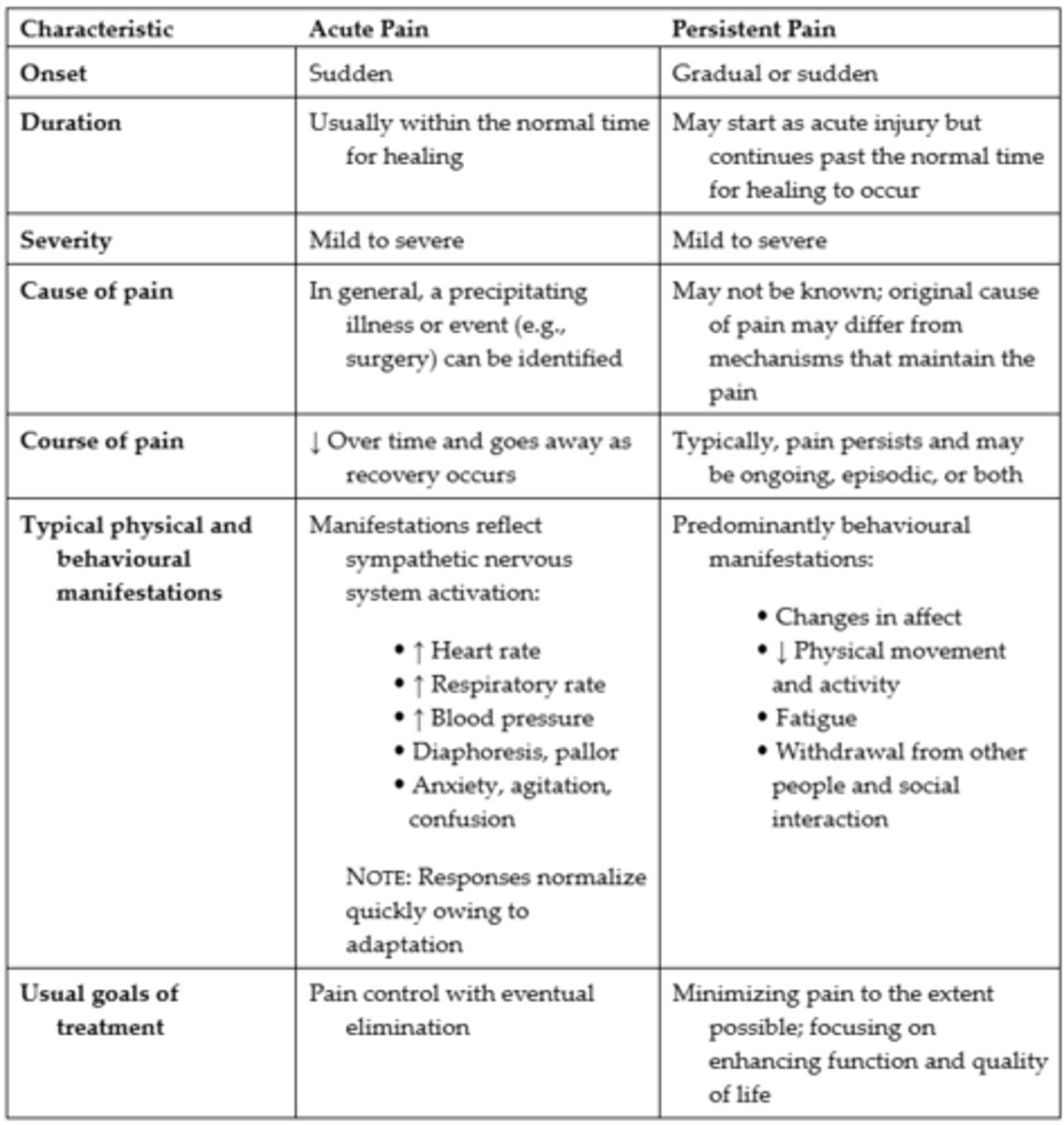

Acute vs. Persistent Pain

Sociocultural Dimension of Pain

- Factors such as demographic features (ex. age, sex, education, socioeconomic status), support systems, social roles, past pain experiences, and cultural aspects that contribute to the pain experience

Pain

- Pain is generally classified as nociceptive, neuropathic, or both, according to the underlying pathological process

Nociceptive Pain

- Caused by damage to somatic or visceral tissue

- Somatic pain: Characterized as aching or throbbing that is well localized, arises from bone, joint, muscle, skin, or connective tissue

- Visceral pain: Which may result from stimuli such as tumour involvement or obstruction, arises from internal organs such as the intestines and the bladder

- Nociceptive pain is usually responsive to both nonopioid and opioid medications

Neuropathic Pain

- Caused by damage to nerve cells or changes in the CNS

- Typically described as burning, shooting, stabbing, or electrical in nature, neuropathic pain can be sudden, intense, short-lived, or lingering

- Difficult to treat, and management includes opioids, antiseizure medications, and antidepressants

- Neuropathic pain can be either central or peripheral in origin

- Common causes of neuropathic pain include trauma, inflammation, metabolic diseases (ex. diabetes), alcoholism, nervous system infections (ex. herpes zoster, human immunodeficiency virus), tumors, toxins, and neurological diseases (ex. multiple sclerosis)

- Often controlled by opioid analgesics alone

Acute Pain

- Acute pain and persistent pain have different causes, courses, manifestations, and treatment

- Examples of acute pain include postoperative pain, labour pain, pain from trauma (ex. lacerations, fractures, sprains) and infection (ex. dysuria), and angina

- For acute pain, treatment includes analgesics for symptom control treatment of the underlying cause (ex. splinting for a fracture, antibiotic therapy for an infection)

- Normally, acute pain diminishes over time as healing occurs

Chronic Pain

- Chronic pain or persistent pain continues beyond the normal time expected for healing, often longer than 3 months

- Although acute pain functions as a signal, warning the person of potential or actual tissue damage, chronic pain does not appear to have an adaptive role

- Chronic pain can be disabling and often is accompanied by anxiety and depression

Cancer Pain

- Often is considered separately because its cause can be determined, its course differs from that of nonmalignant pain (cancer pain often worsens with documented disease progression), and the use of opioids in its treatment is more widely accepted than in the treatment of noncancer pain

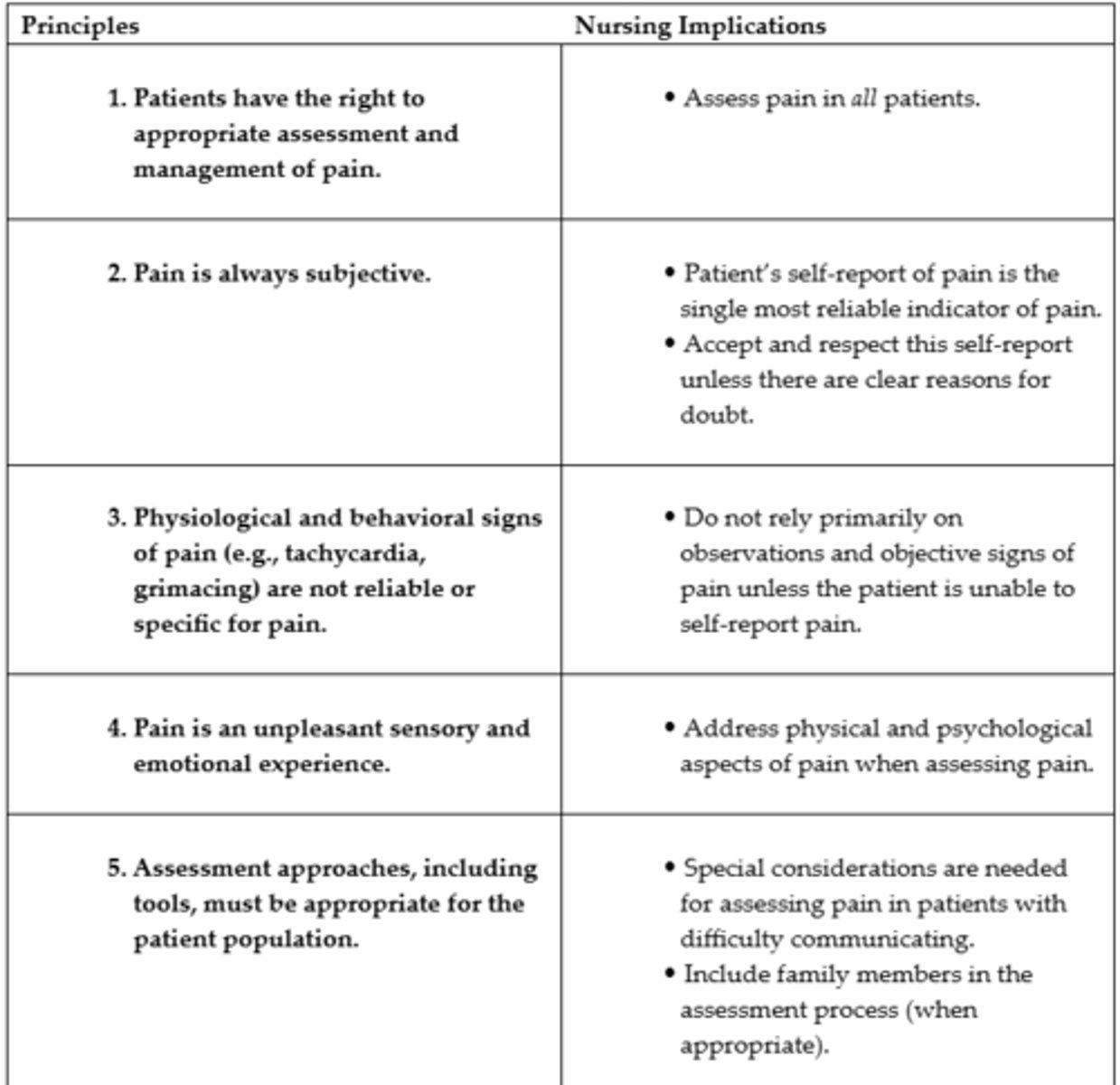

Goals of Pain Assessment

- To describe the patient's sensory, affective, behavioural, and sociocultural pain experience for the purpose of implementing pain management techniques

- To identify the patient's goal for therapy and resources and strategies for effective self-management

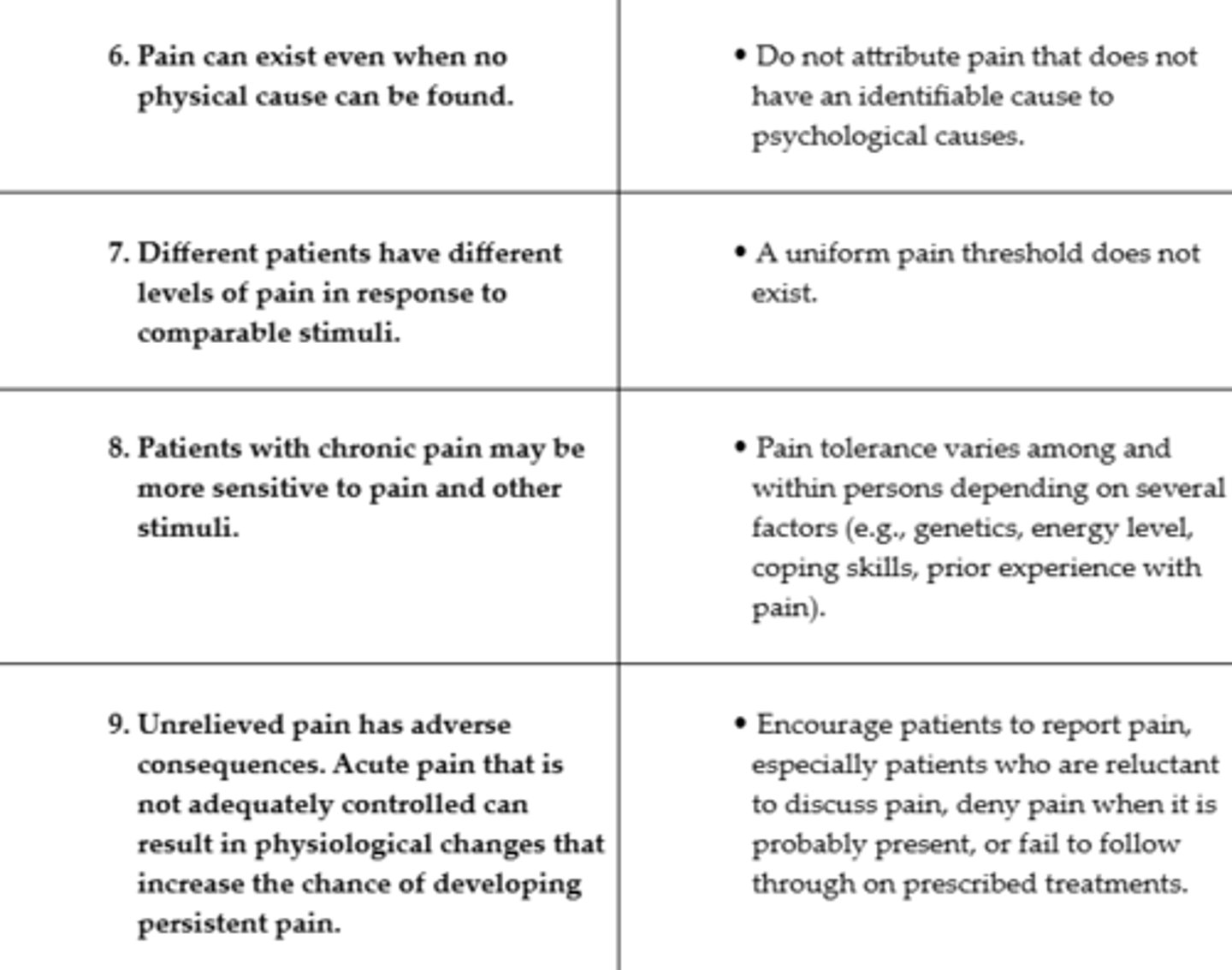

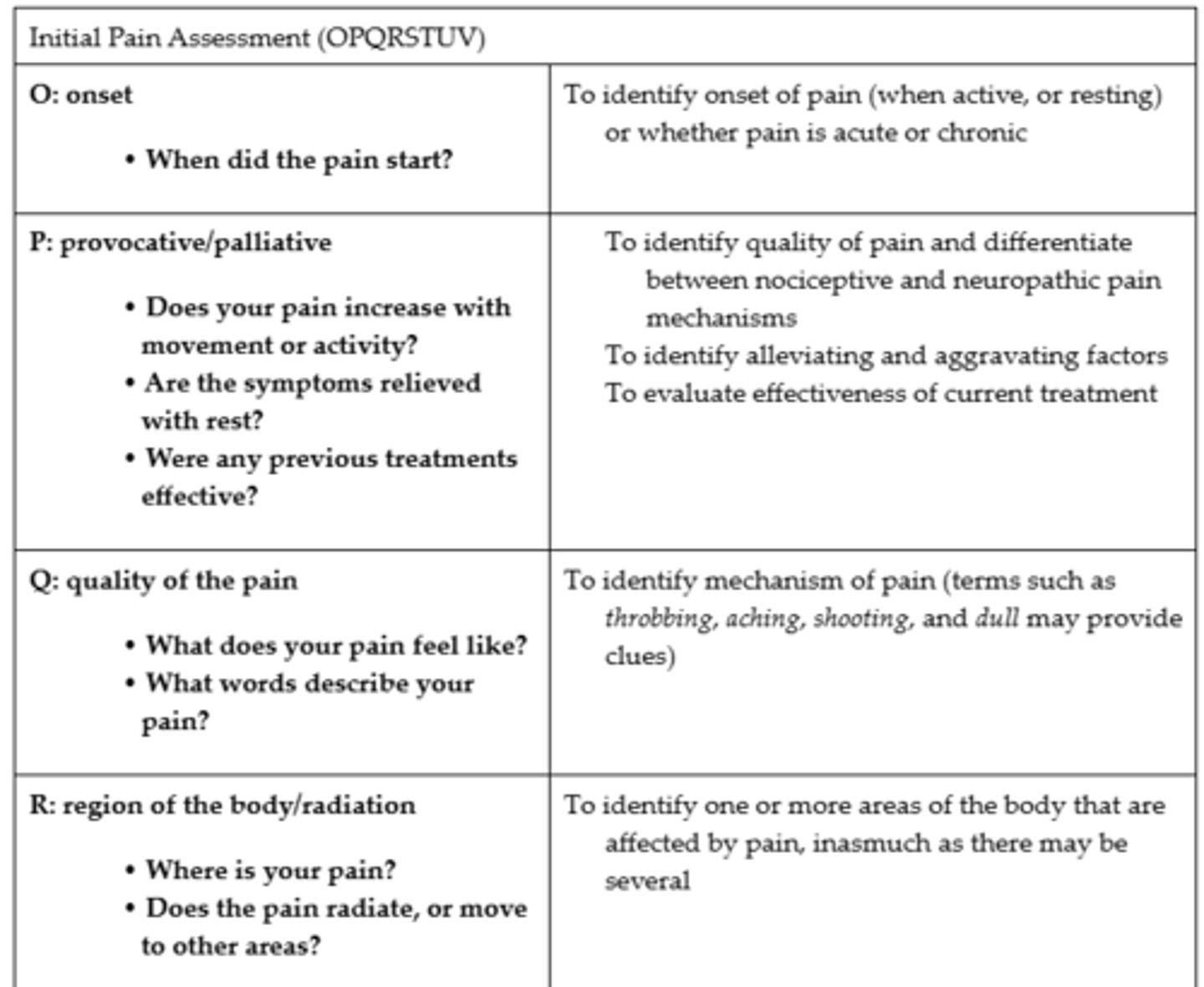

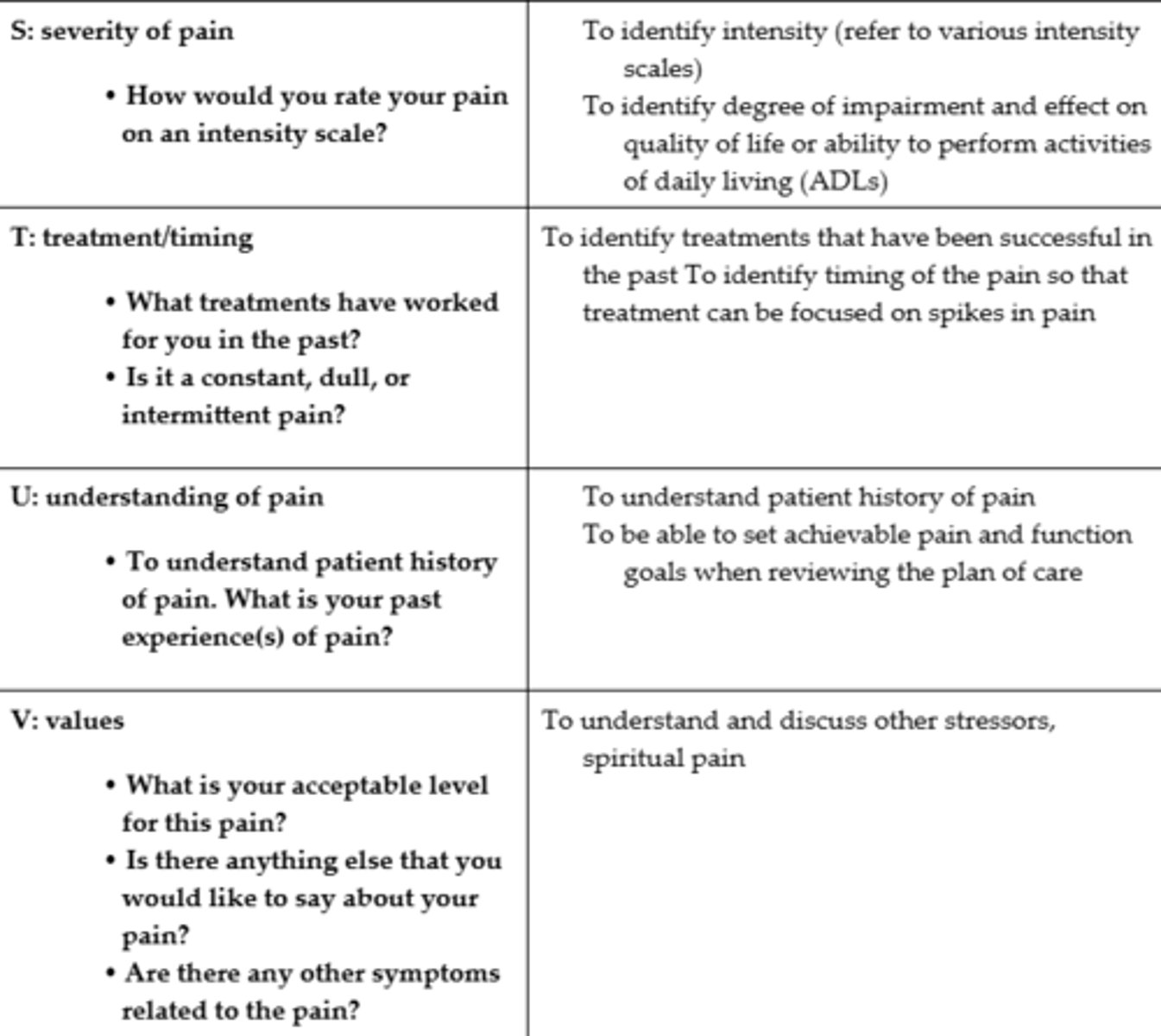

Initial Pain Assessment (OPQRSTUV)

- Onset, provocative/palliative, quality of the pain, region of the body/radiation, severity of pain, treatment/timing, understanding of pain, and values

Principles of Pain Assessment #1

Principles of Pain Assessment #2

Initial Pain Assessment #1

Initial Pain Assessment #2

Pattern of Pain

Pain onset (when it starts) and duration (how long it lasts) are components of the pain pattern

- Acute pain typically increases during wound care, ambulation, coughing, and deep breathing

- A patient may have constant, round-the-clock pain or discrete periods of intermittent pain. Breakthrough pain is moderate to severe pain that occurs despite treatment (usually rapid in onset and brief)

- Episodic, procedural, or incident pain is a transient increase in pain that is caused by a specific activity or event that precipitates the pain (ex. dressing changes, movement, eating, position changes, and certain procedures such as catheterization)

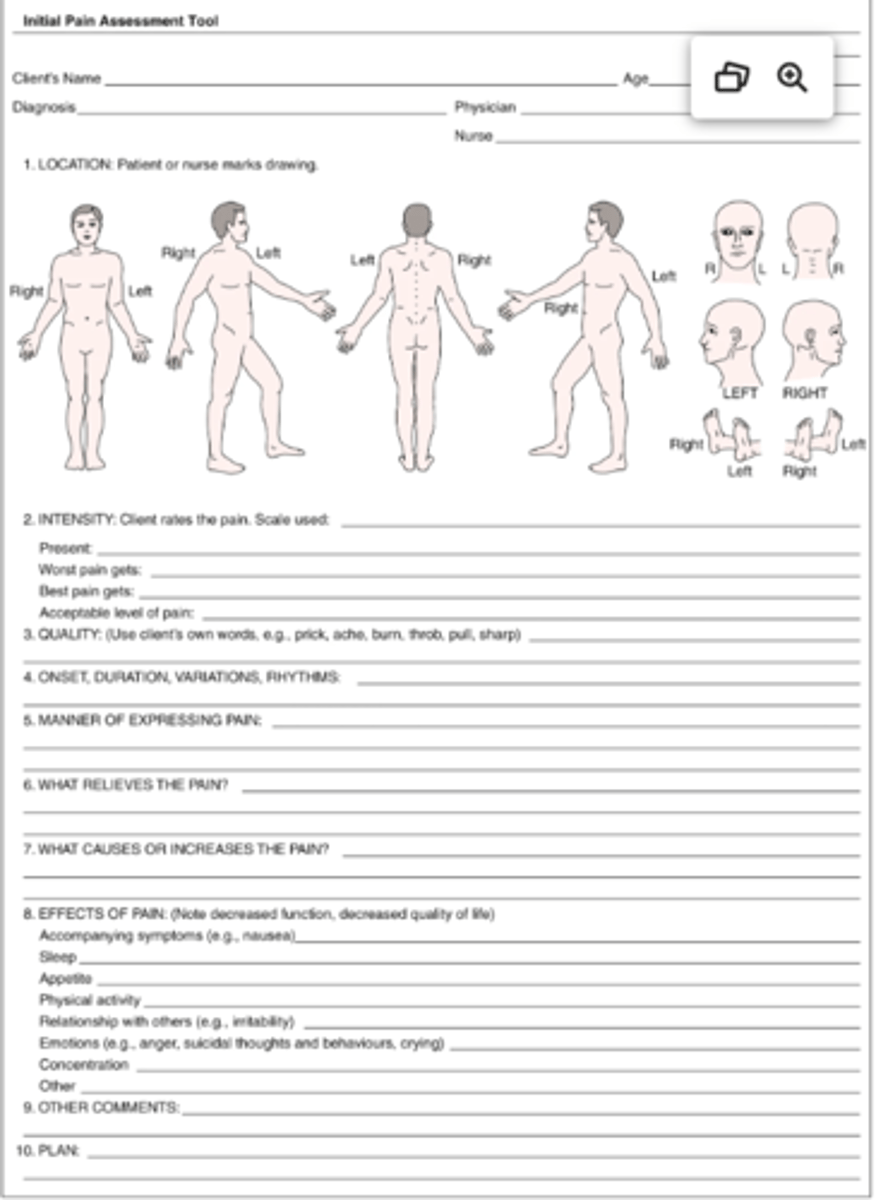

Area of Pain

- The area or location of pain assists in identifying possible causes of the pain and in determining treatment

- Some patients may be able to specify one or more precise locations of their pain, whereas others may describe very general areas or comment that they "hurt all over"

- Ex. Sciatica is pain that originates from compression or damage to the sciatic nerve or its roots within the spinal cord (the pain is projected along the course of the peripheral nerve, causing painful shooting sensations down the back of the thigh and the inside of the leg)

- Information about the location of pain is elicited by asking the patient to (a) describe the site or sites of pain, (b) point to painful areas on the body, or (c) mark painful areas on a body diagram

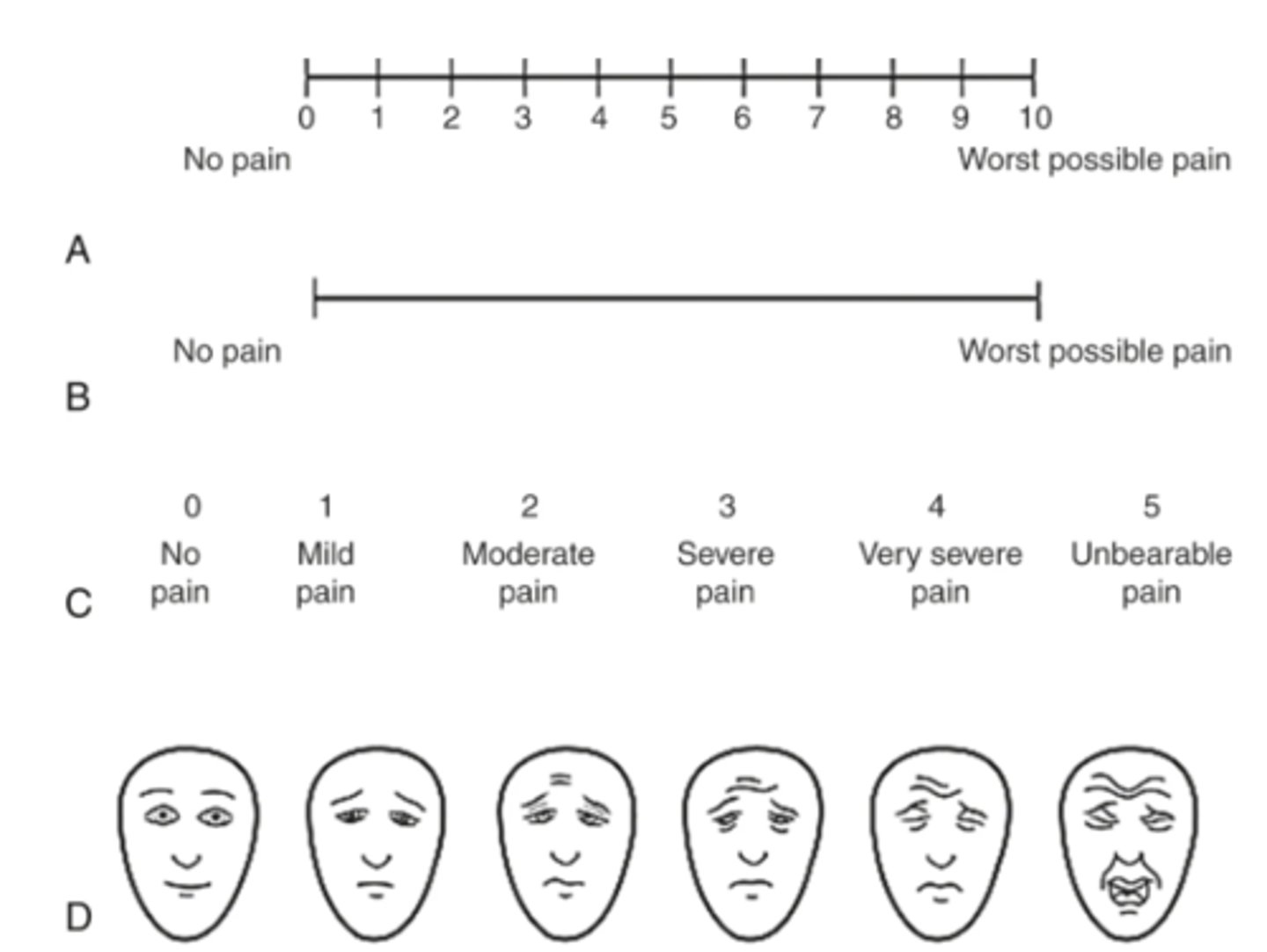

Pain Scales

- Useful in helping the patient communicate the intensity of pain and in guiding treatment

- Scales must be adjusted to age and level of cognitive development. Numerical scales (ex. 0="no pain" and 10="the worst pain"), verbal descriptor scales (ex. none, a little [1-3], moderate [4-6], and severe [7-10]), or visual analogue scales (a 10-cm line with one end labelled "no pain" and the other end labelled "worst possible pain") can be used by most adults to rate the intensity of their pain

- For patients who are unable to respond to other pain intensity scales, a series of faces ranging from "smiling" to "crying" can be used

Initial Pain Assessment Tool

Pain Intensity Scale

Subjective Nature of Pain

- The subjective nature of pain refers to the self-reported quality or characteristics of the pain

- Many commonly used words to describe the nature of pain are included in the McGill Pain Questionnaire

- Two major strengths of the MPQ are that (1) it provides a comprehensive assessment of the nature of pain problems in a short time frame (5 to 10 minutes), and (2) it includes subsets of verbal pain descriptors associated with both nociceptive and neuropathic pain

Patients Meaning of Pain

- For clinical assessment purposes, key areas of inquiry with patients about the meaning of pain and related beliefs should include effective pain control in relation to current intervention strategies, pain-related disability, value placed on comfort and solace from other people, and the effect of emotions on the experience of pain

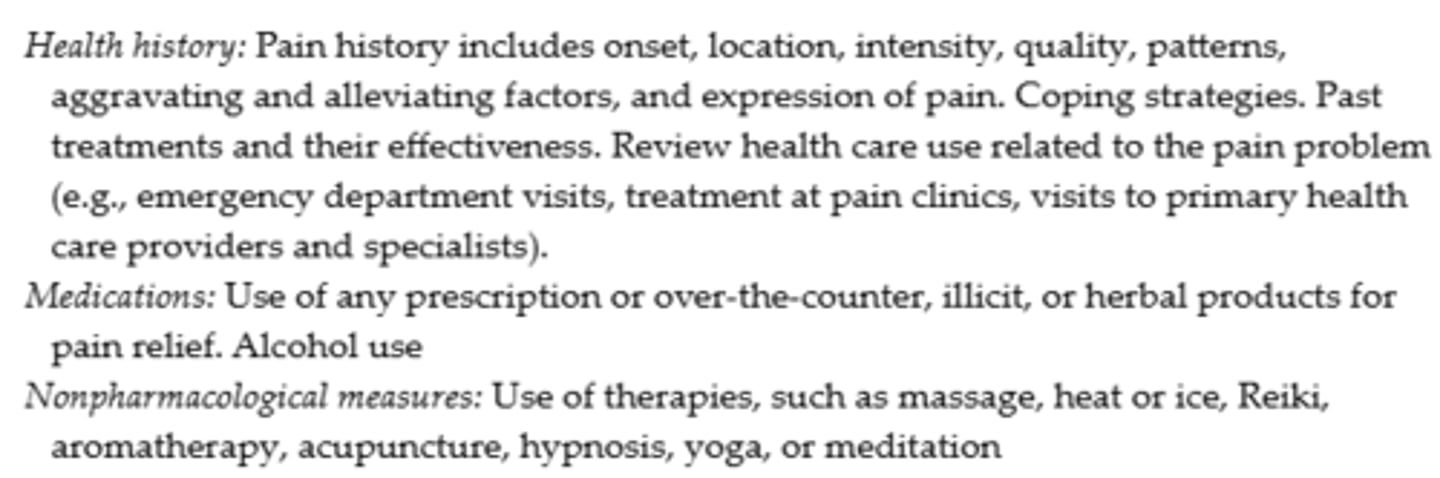

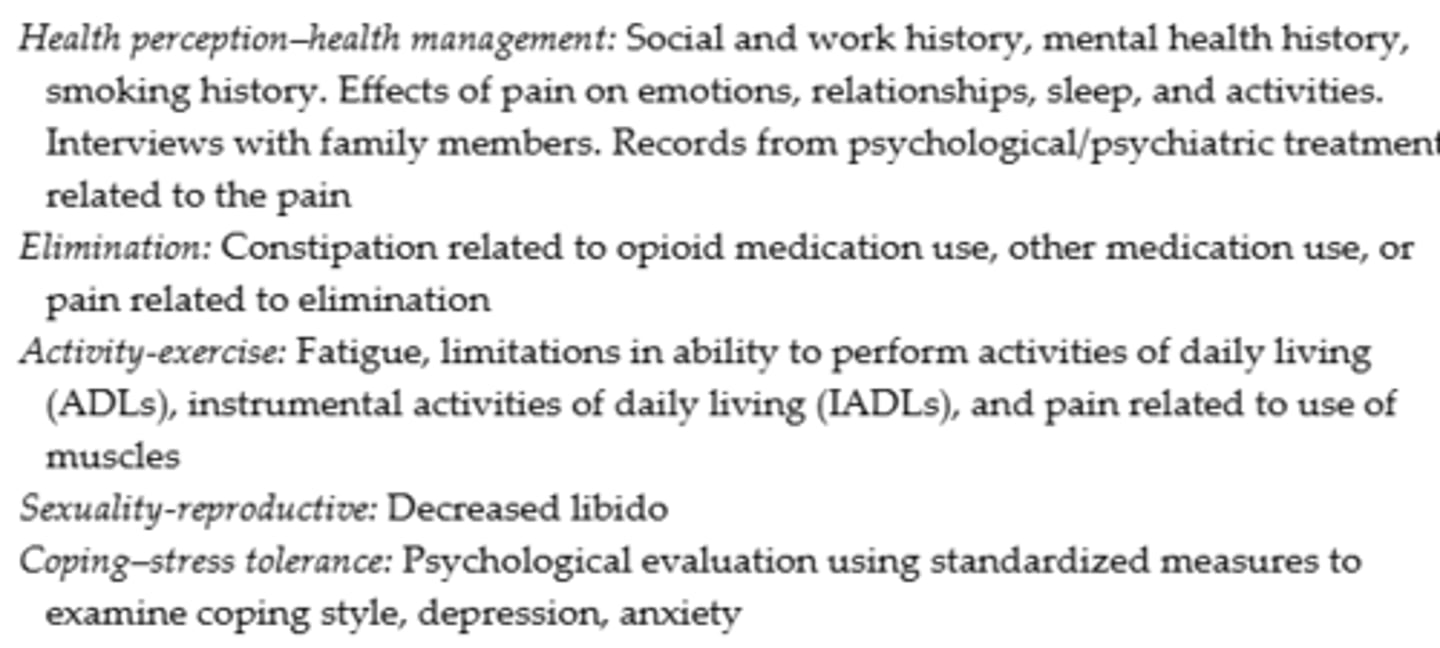

Subjective Data - Nursing Assessment: Pain

Functional Health Patterns - Nursing Assessment: Pain

Objective Data - Nursing Assessment: Pain

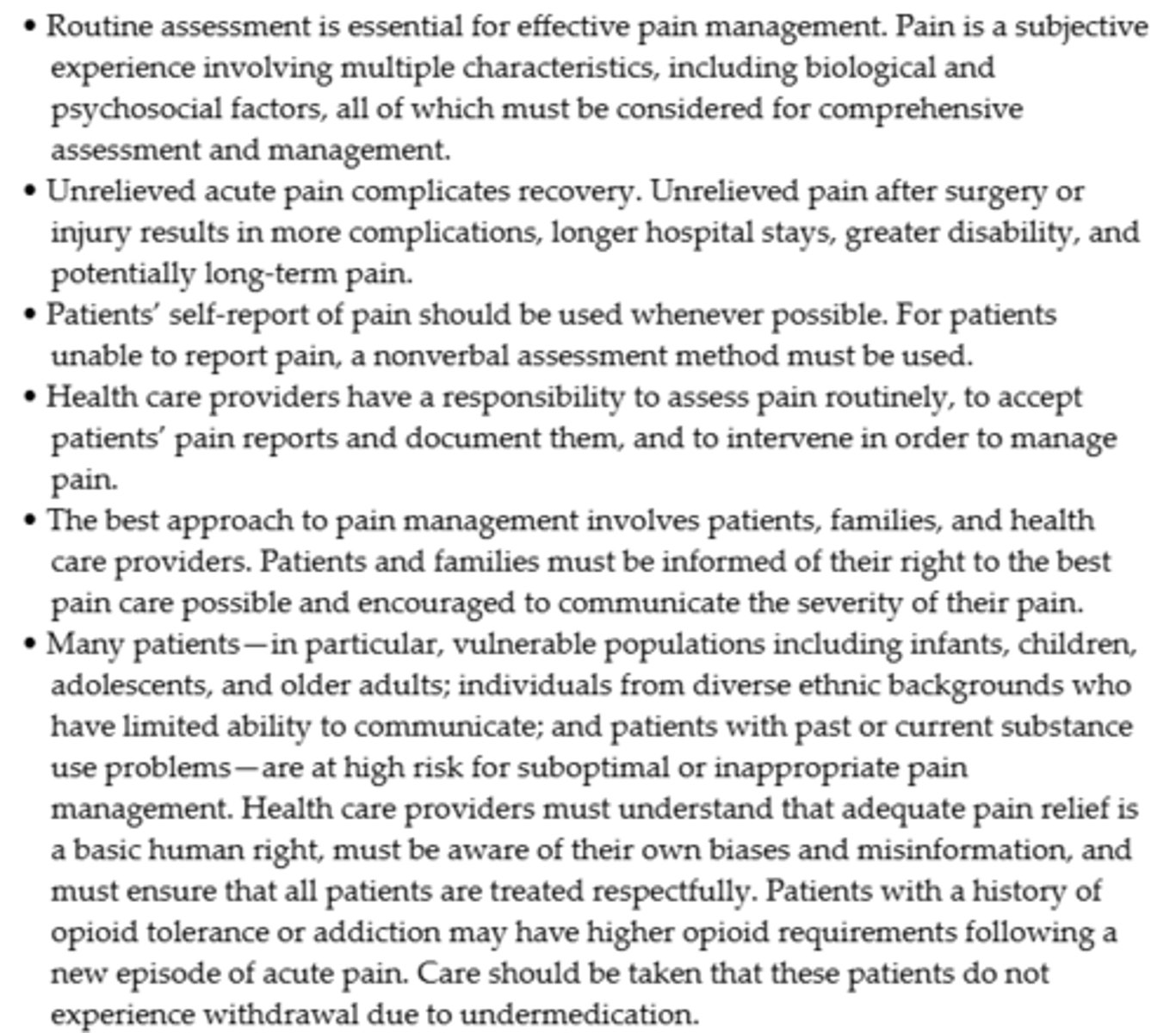

Pain Assessment & Management - Best Practice Guidelines #1

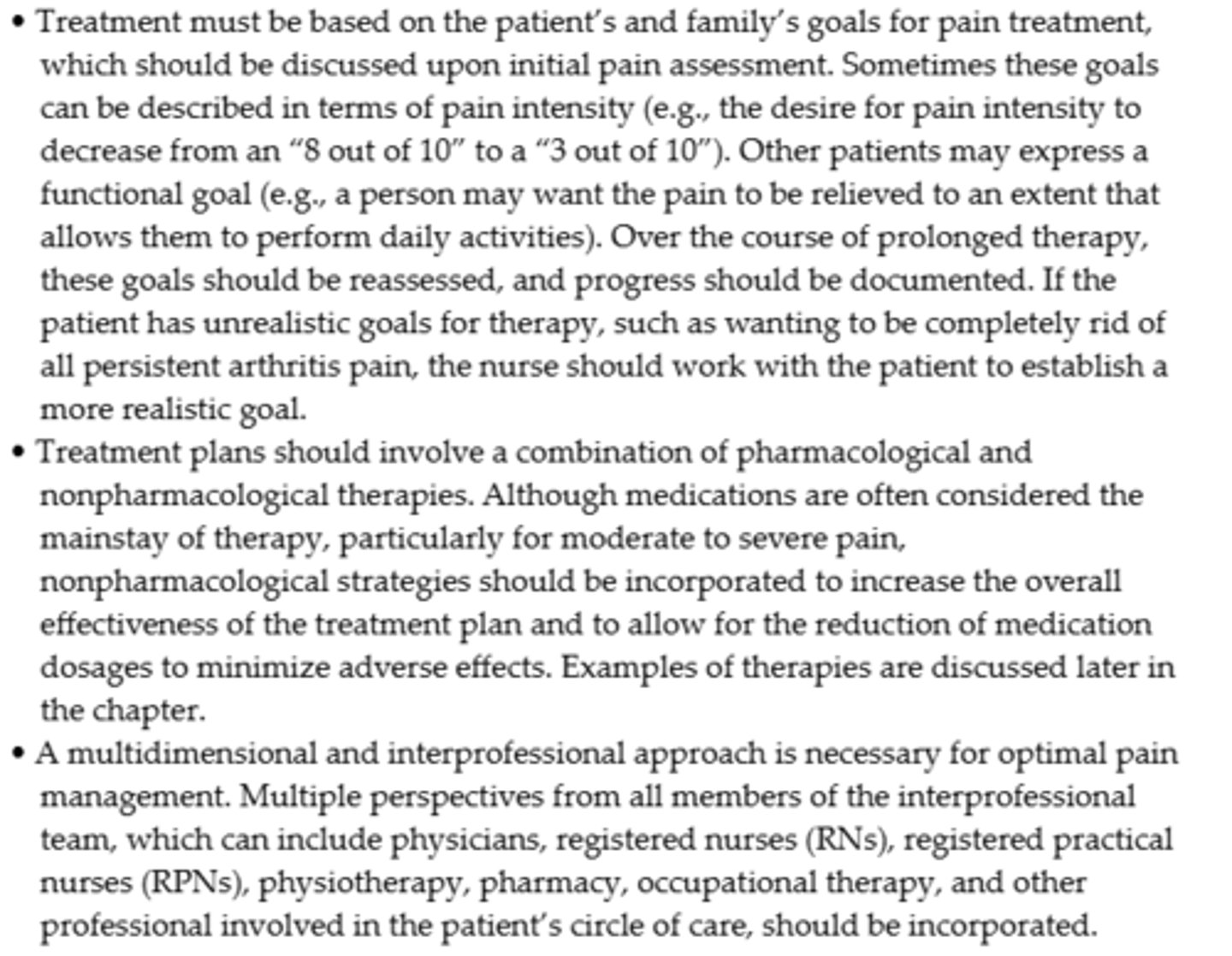

Pain Assessment & Management - Best Practice Guidelines #2

Pain Assessment & Management - Best Practice Guidelines #3

Managing Adverse Effects of Opioids

- These include calculating equianalgesic doses, scheduling analgesic doses, titrating opioids, and selecting from the prescribed analgesic medications

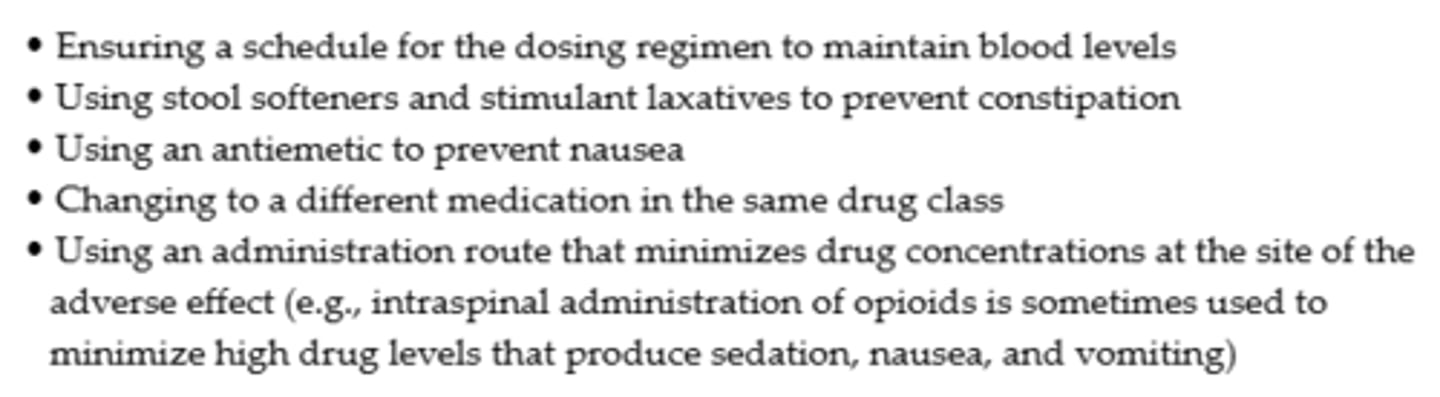

Equianalgesic Dose

- A dose of one analgesic that produces pain-relieving effects equivalent to those of another analgesic

- The concept of equivalence is important when substituting one analgesic for another in the event that a particular medication is ineffective or causes intolerable adverse effects and when the administration route of opioids is changed (ex. from parenteral to oral)

Scheduling Analgesics

- Appropriate analgesic scheduling should focus on prevention or ongoing control of pain rather than on providing analgesics only after the patient's pain has become moderate to severe

- A patient should receive medication before procedures and activities that are expected to produce pain

- Fast-acting medications should be used for incident or breakthrough pain, whereas long-acting analgesics are more effective for constant pain

Analgesic Titration

- Dosage adjustment that is based on assessment of the adequacy of analgesic effect versus the adverse effects produced

- The amount of analgesic needed to manage pain varies widely, and titration is an important strategy in addressing this variability

- An analgesic dosage can be titrated upward or downward, depending on the situation

Common Equianalgesic Doses

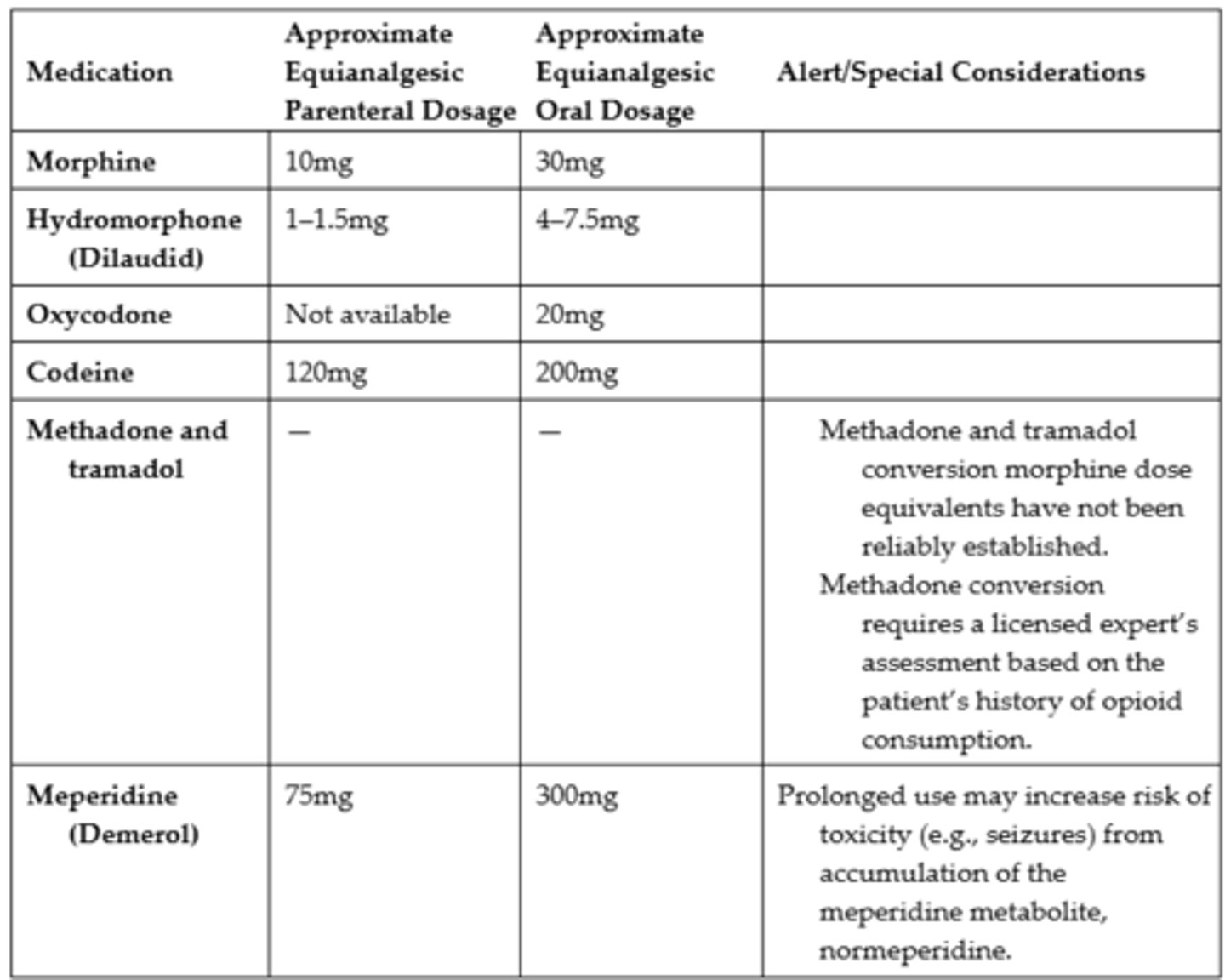

Analgesic 3-Step Ladder Approach

- Step 1 medications are used for mild pain

- Step 2 for mild to moderate pain

- Step 3 for moderate to severe pain

*If pain persists or increases, medications from the next higher step are introduced to control the pain

*The steps are not meant to be sequential if someone has moderate to severe pain: for this person, the analgesics given would be the stronger analgesics listed in steps 2 and 3

Mild Pain

- 1 to 3 on a scale of 0 to 10

- Nonopioid analgesics (Aspirin and other salicylates, other NSAIDs, and acetaminophen) may be used

Characteristics of Nonopioid Analgesics

- Their analgesic properties have a ceiling effect, that is, increasing the dose beyond an upper limit provides no greater analgesia

- They do not produce tolerance or physical dependence

- Many are available without a prescription

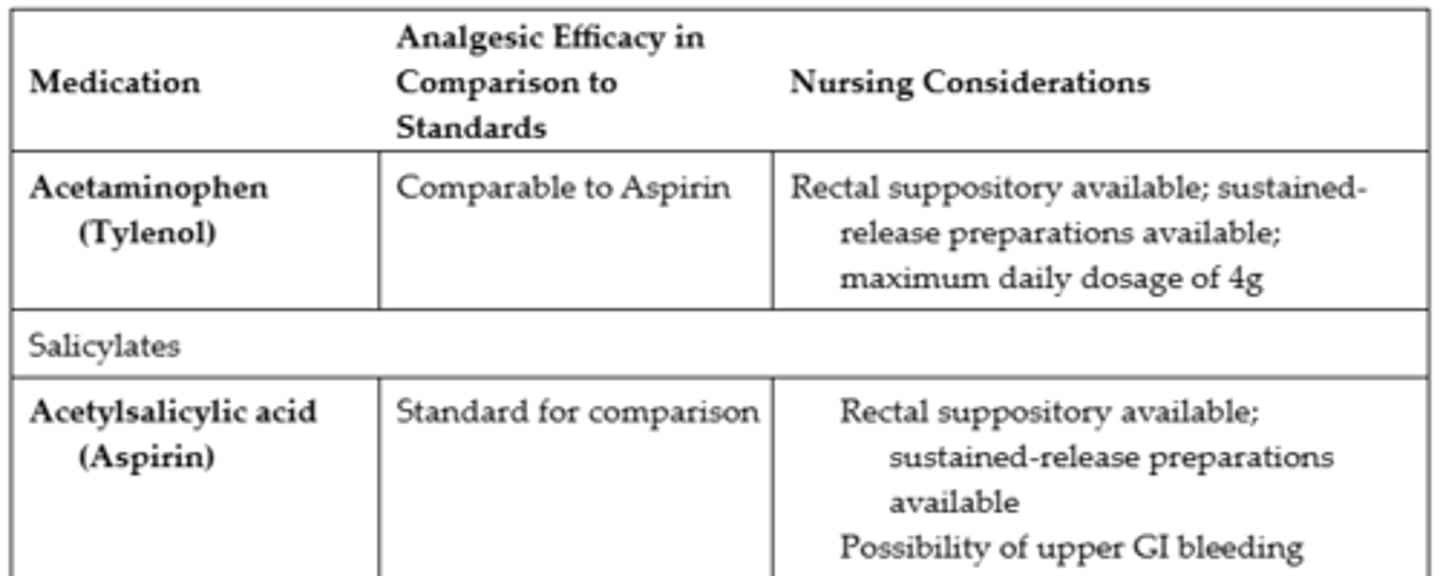

Comparison of Select Nonopioid Analgesics #1

Comparison of Select Nonopioid Analgesics #2

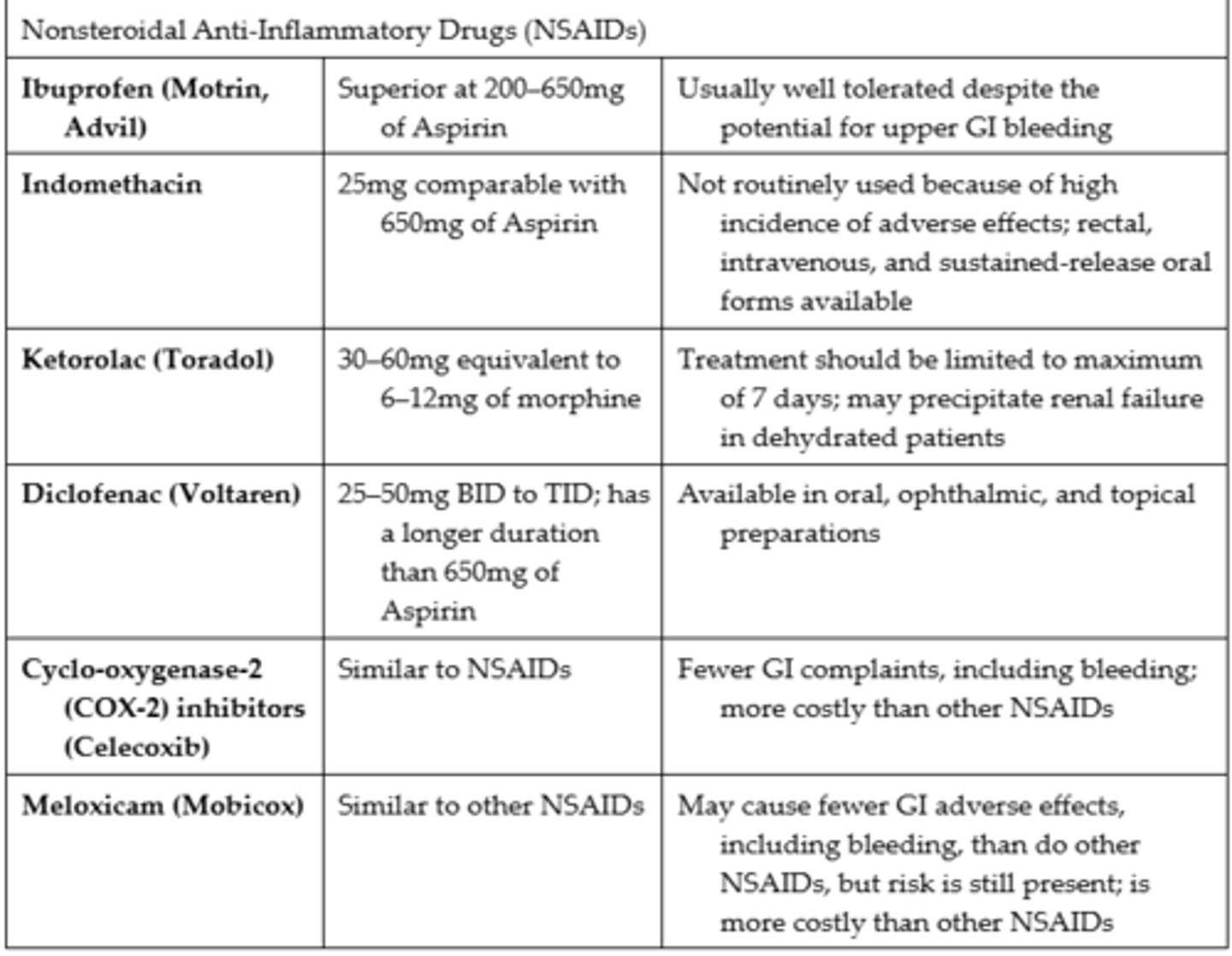

Arachidonic Acid Oxidization

Mild to Moderate Pain

- When pain is moderate in intensity (4 to 6 on a scale of 0 to 10) or mild but persistent despite nonopioid therapy, step 2 medications are indicated

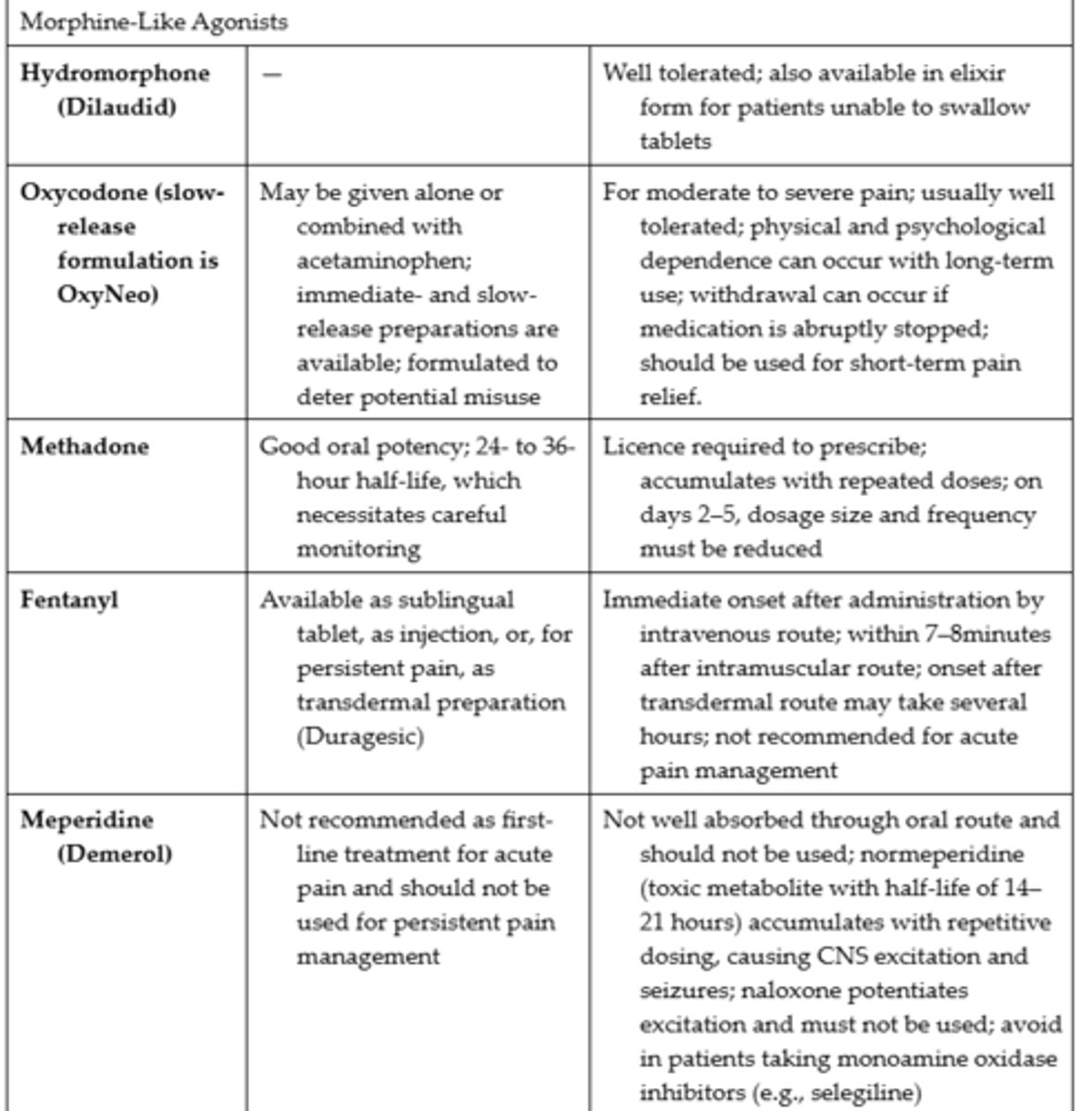

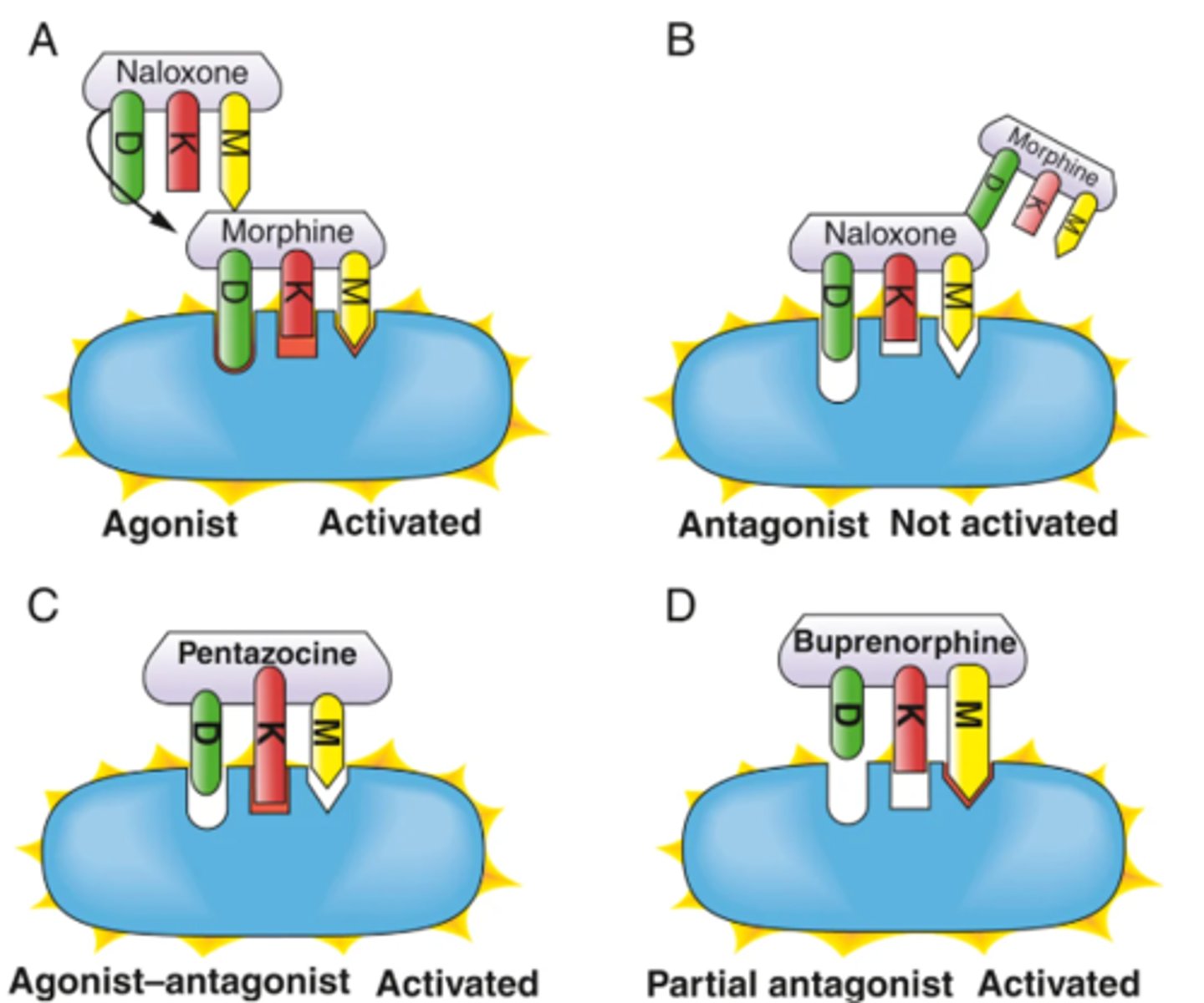

- Opioids include many medications that produce their effects by binding to receptors (found in the CNS - mu, kappa, delta)

- Opioid agonists (ex. morphine) bind to the receptors and cause analgesia

- Antagonists and mixed opioids (ex. naloxone) bind to the receptors but do not produce analgesia

- Prescriptions for commonly used opioids are often for products combining an opioid with a nonopioid analgesic to limit the opioid dose

Opioid Analgesic Ceiling

- A dosage at which no additional analgesia is produced regardless of further dosage increases

- Can precipitate withdrawal in a patient who is physically dependent on agonist medications

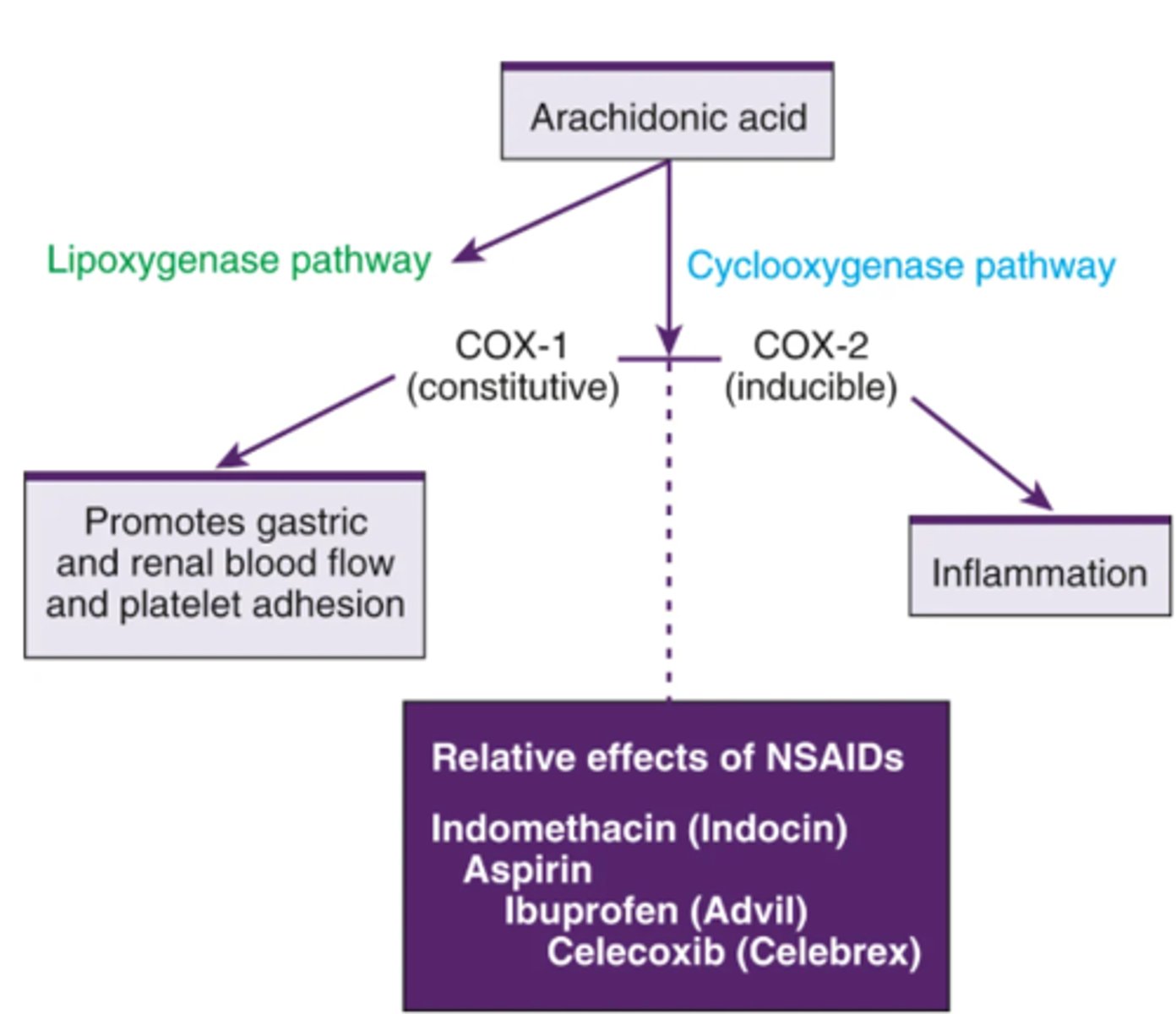

Opioid Analgesics Commonly Used for Mild to Moderate Pain

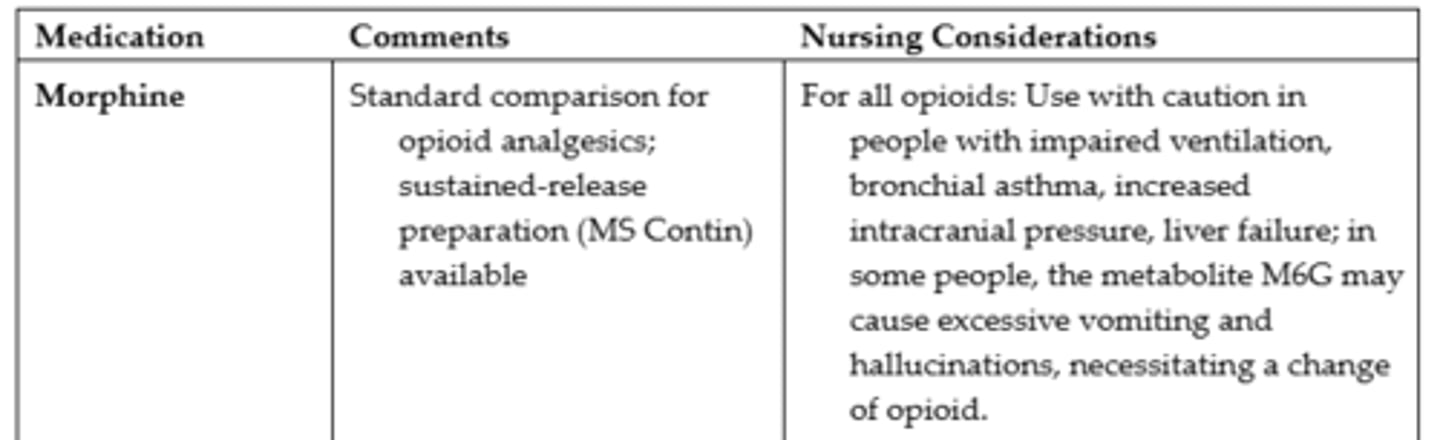

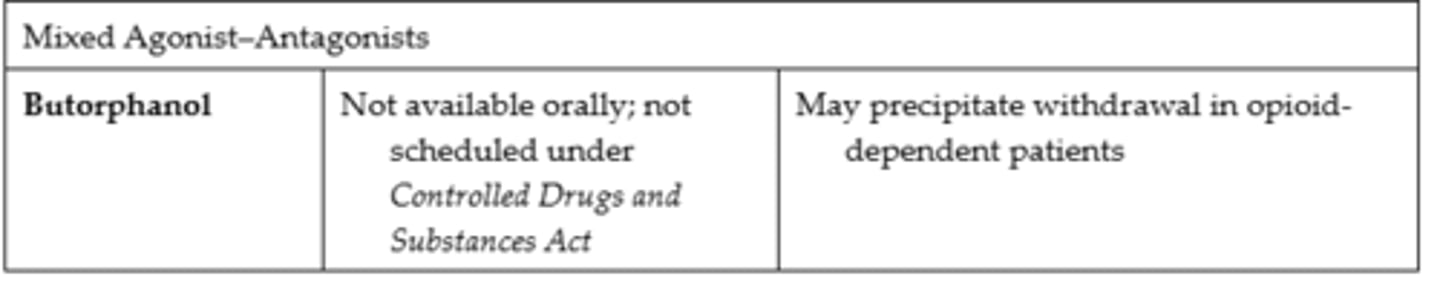

Opioids Commonly Used for Severe Pain #1

Opioids Commonly Used for Severe Pain #2

Opioids Commonly Used for Severe Pain #3

Moderate to Severe Pain

- Step 3 medications are recommended for moderate to severe pain (4 to 10 on a scale of 0 to 10) or when step 2 medications do not produce effective pain relief

- Most commonly used step 3 analgesics are mu-receptor agonists, although these medications also bind with the other receptors

- These medications are effective for moderate to severe pain because they are potent, have no analgesic ceiling, and can be delivered via many routes of administration

Opioid Receptor Subtypes

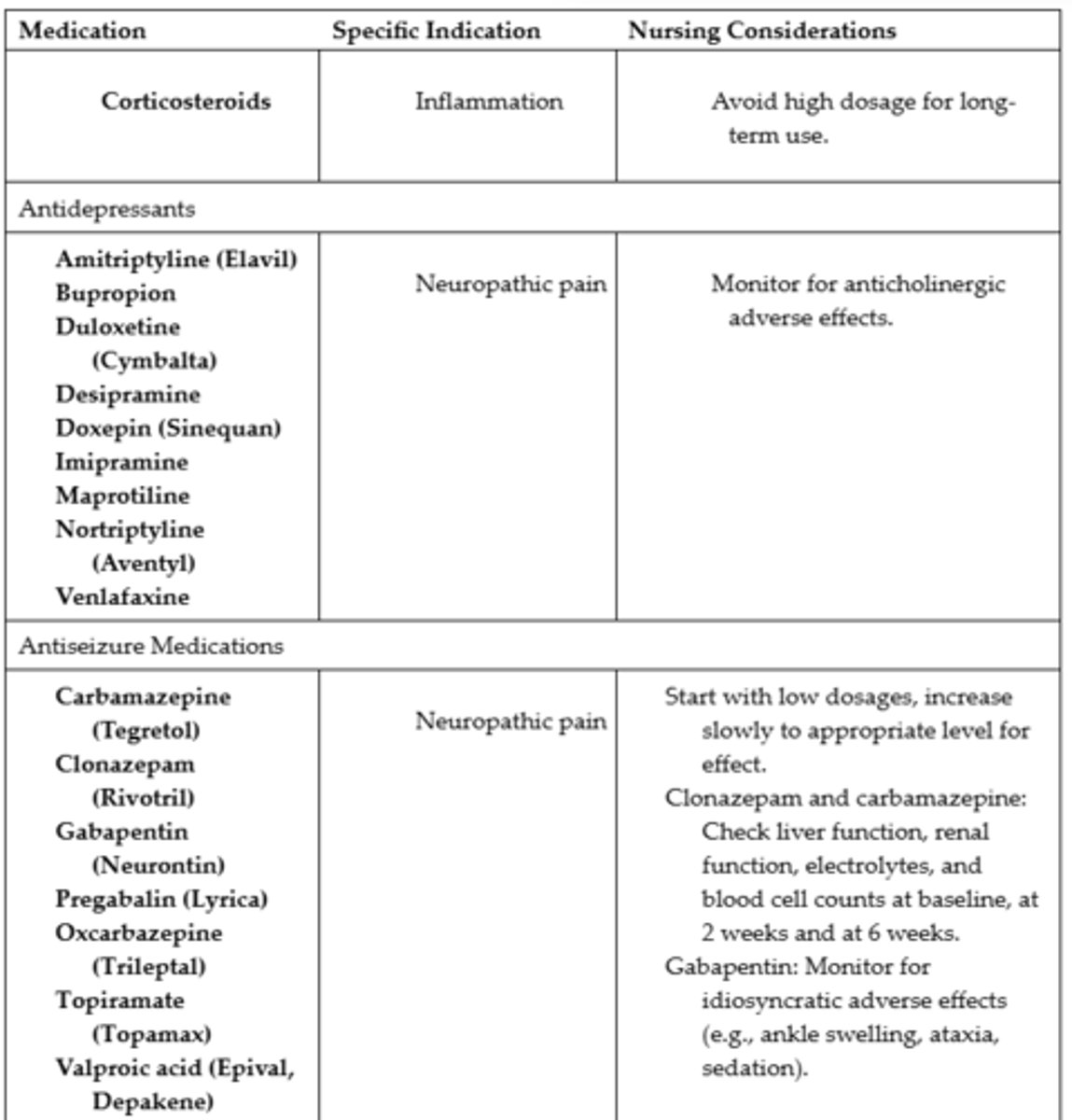

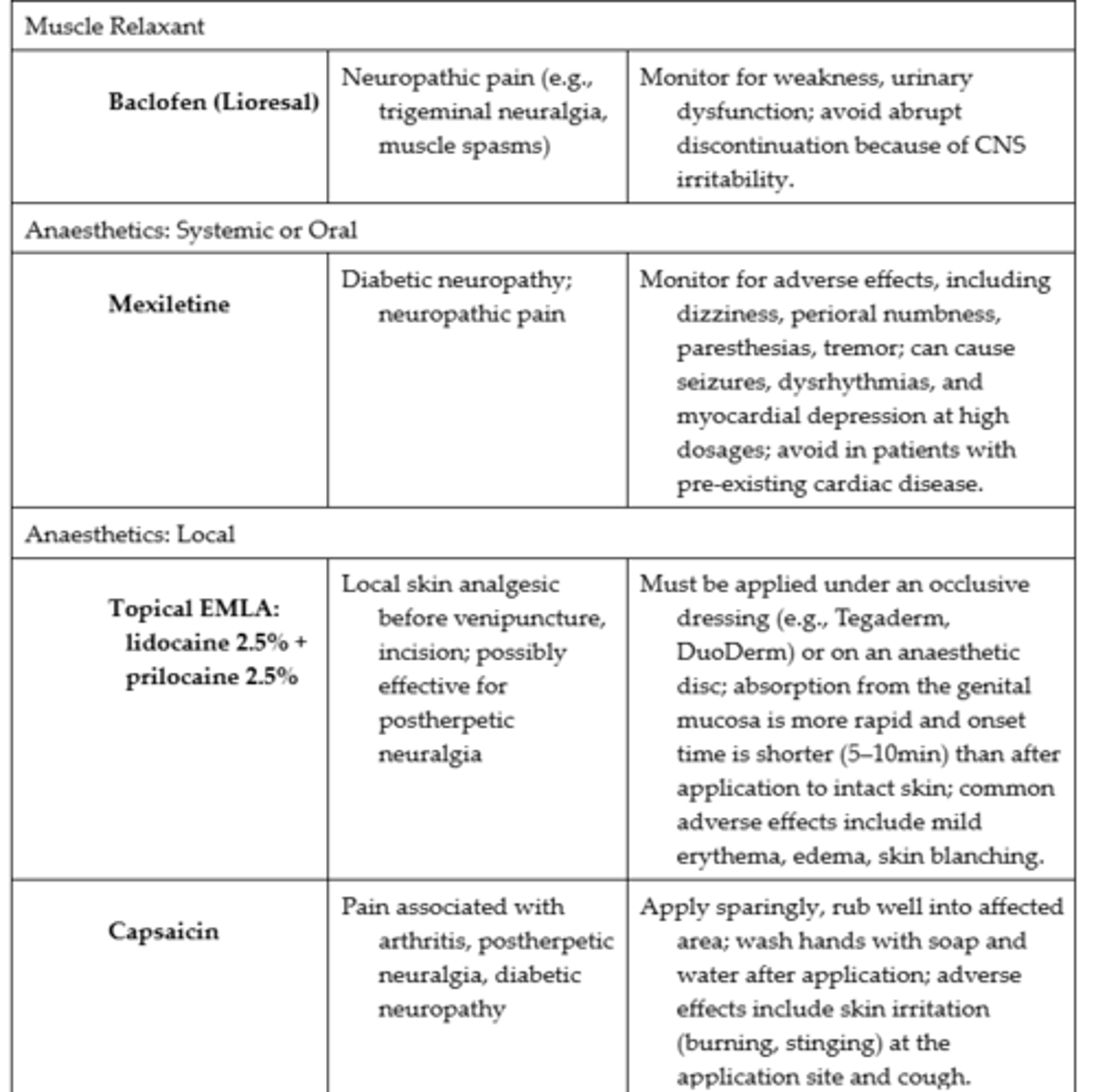

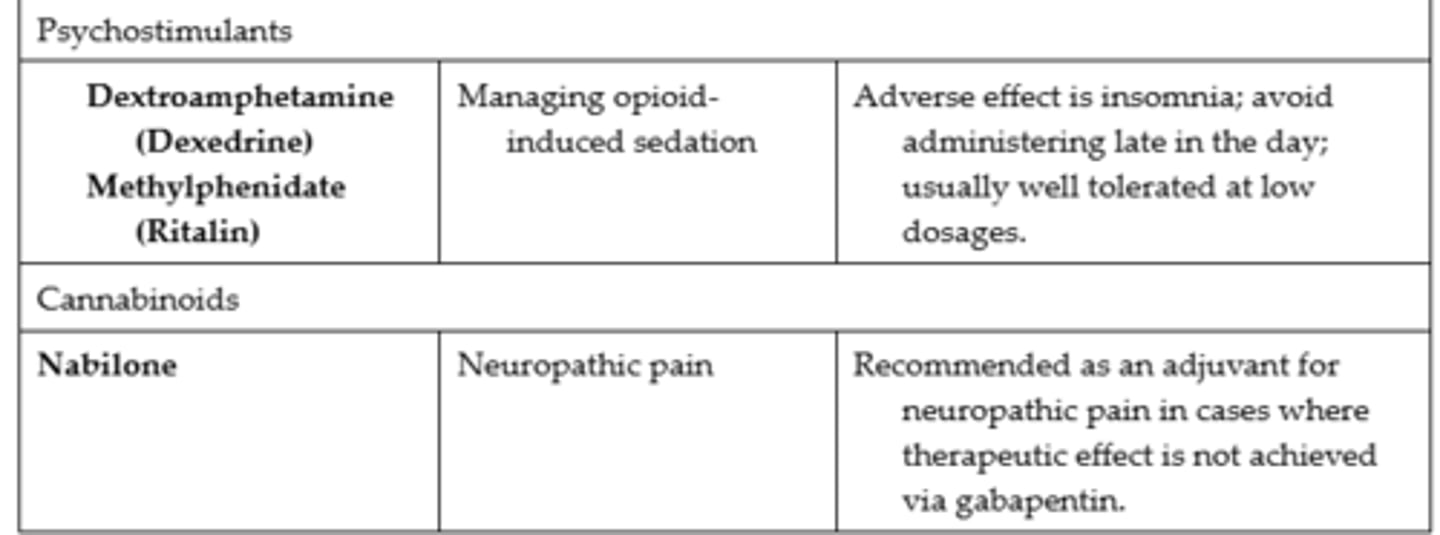

Adjuvant Medications Used for Pain #1

Adjuvant Medications Used for Pain #2

Adjuvant Medications Used for Pain #3

Problems with Opioids

- Opioids may cause respiratory depression.

- If respirations are 12 or fewer breaths per minute, withhold medication and contact the health care provider.

- Transdermal fentanyl should not be used for management of acute pain

- Constipation is the most common opioid adverse effect

- Nausea often is a problem in opioid-naive patients

- Afraid of sedation effects

- Itching may occur with opioids, most frequently when they are administered via intraspinal routes

Adjuvant Analgesic Therapy

- Medications used in conjunction with opioid and nonopioid analgesics

- Adjuvants are sometimes referred to as coanalgesics

- They include medications that enhance pain therapy through one of three mechanisms: (a) enhancing the effects of opioids and nonopioids, (b) possessing analgesic properties of their own, or (c) counteracting the adverse effects of other analgesics

Commonly Used Pharmacological & Nonpharmacological Analgesic Therapies

Ketamine

- Ketamine has traditionally been used as an anaesthetic agent because of its dissociative and amnesic effects

- However, ketamine at lower doses displays analgesic effects with opioid-sparing capabilities

- Ketamine works by inhibiting pain signals to the brain and producing desired analgesic effects

- Adverse effects of ketamine include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and hallucinations

Administration Route Benefits for Opioids

- This flexibility allows the health care provider to (a) target a particular anatomical source of the pain, (b) achieve therapeutic blood levels rapidly when necessary, (c) avoid certain adverse effects through localized administration, and (d) provide analgesia when patients are unable to swallow

Sustained-Release or Extended-Release Preparation

- These medications should not be crushed, broken, dissolved, or chewed. They are to be swallowed whole

- If all the medicine is released into a person at once, serious adverse effects can occur, including death from overdose

Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) - Demand Analgesia

- An infusion system that allows the patient to self-administer a dose of opioid through a pump when needed: The patient pushes a button to receive a bolus infusion of an analgesic within preprogrammed intervals

- PCA is used widely for the management of acute pain, including postoperative pain and cancer pain

- Often, the patient also receives an additional continuous basal infusion (known as PCA plus basal) at a preset dose and rate

- The addition of a continuous basal infusion to a PCA regimen improves nighttime pain relief and promotes better sleep postoperatively

- Common opioids used in PCA administration method include morphine, fentanyl, and hydromorphone (Dilaudid)

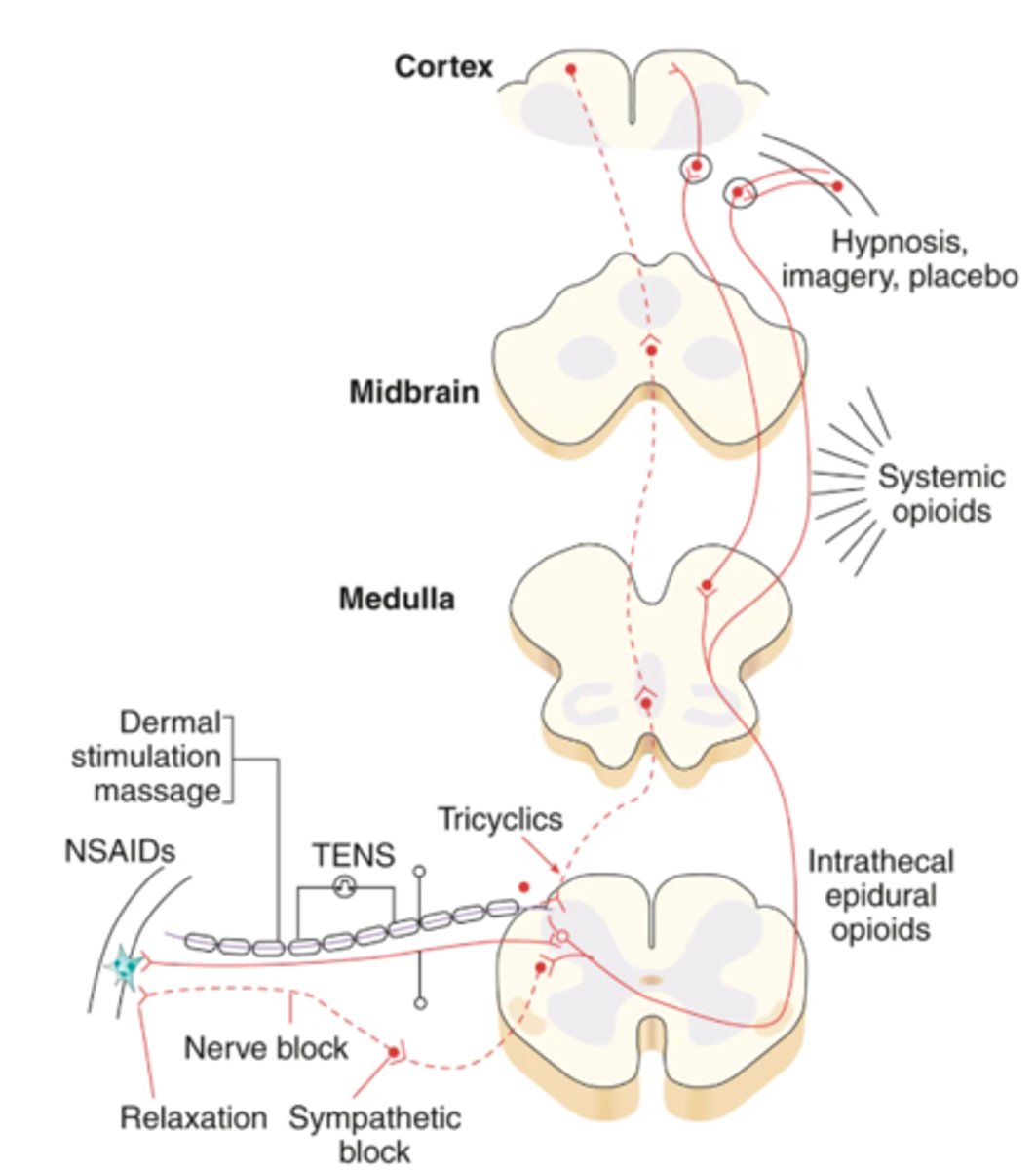

Nerve Blocks

- Nerve blocks are used to reduce pain by temporarily or permanently interrupting transmission of nociceptive input

- This is achieved with local anaesthetics or neurolytic drugs (ex. alcohol, phenol)

- Neural blockade with local anaesthetics is sometimes used for perioperative pain

- Nerve blocks have been a successful pain management technique for more localized persistent pain states, such as peripheral vascular disease, trigeminal neuralgia, causalgia, and some cancer pain

Therapeutic Nerve Blocks

- Nerve blocks generally involve one-time or continuous infusion of local anaesthetics into a particular area to produce pain relief

- Such relief is also referred to as regional anaesthesia

- Nerve blocks interrupt all afferent and efferent transmission to the area and thus are not specific to nociceptive pathways

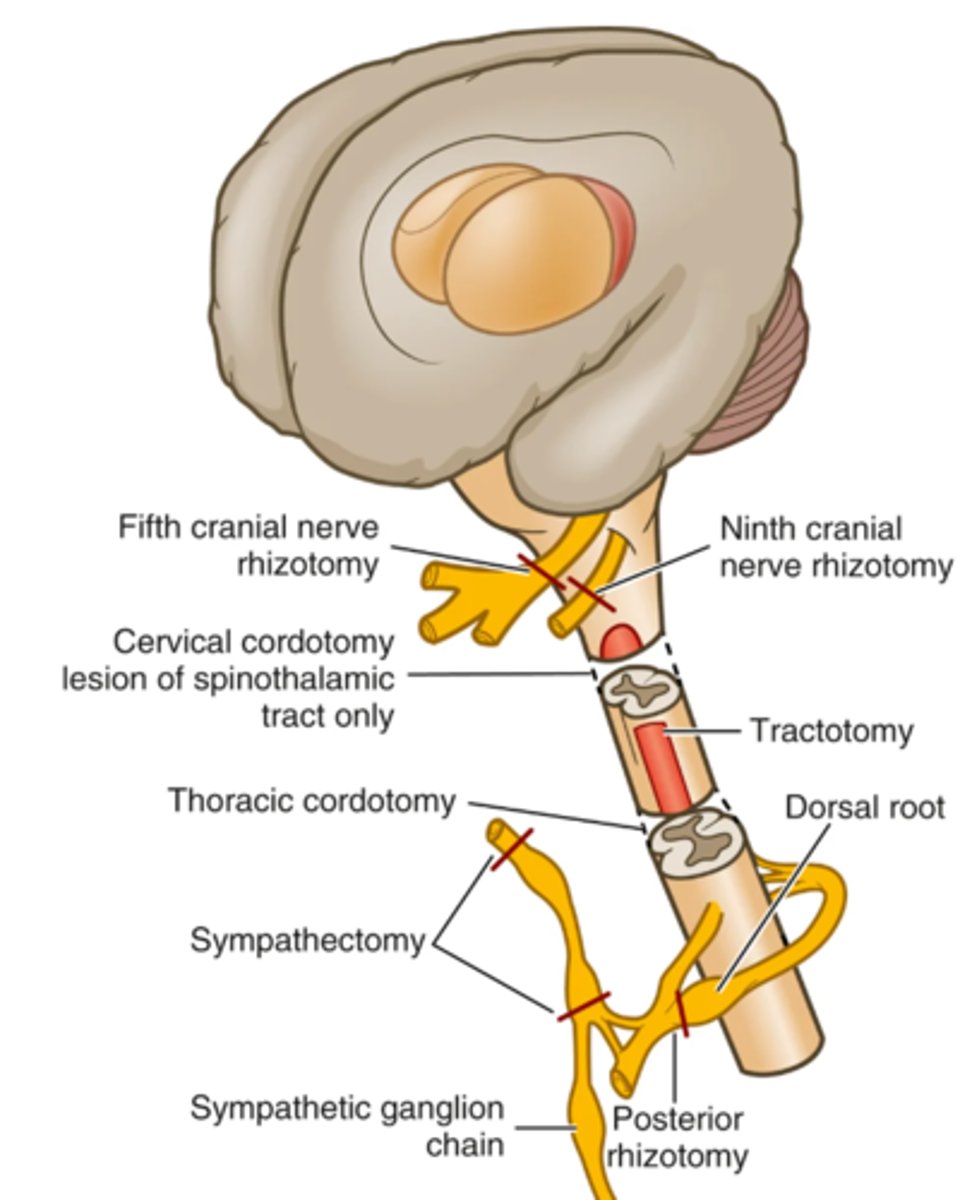

Neuroablative Interventions

- Performed for severe pain that is unresponsive to all other therapies

- Neuroablative techniques destroy nerves, thereby interrupting pain transmission

- Destruction is accomplished by surgical resection or thermocoagulation, including radiofrequency coagulation

- Neuroablative interventions that destroy the sensory division of a peripheral or spinal nerve are classified as neurectomies, rhizotomies, and sympathectomies

Neuroaugmentation

- Involves electrical stimulation of the brain and the spinal cord

- Spinal cord stimulation is performed much more often than deep brain stimulation

- Technological advances have enabled the use of multiple leads and multiple electrode terminals so as to stimulate large areasS

Sites for Neurosurgical Procedures for Pain Relief

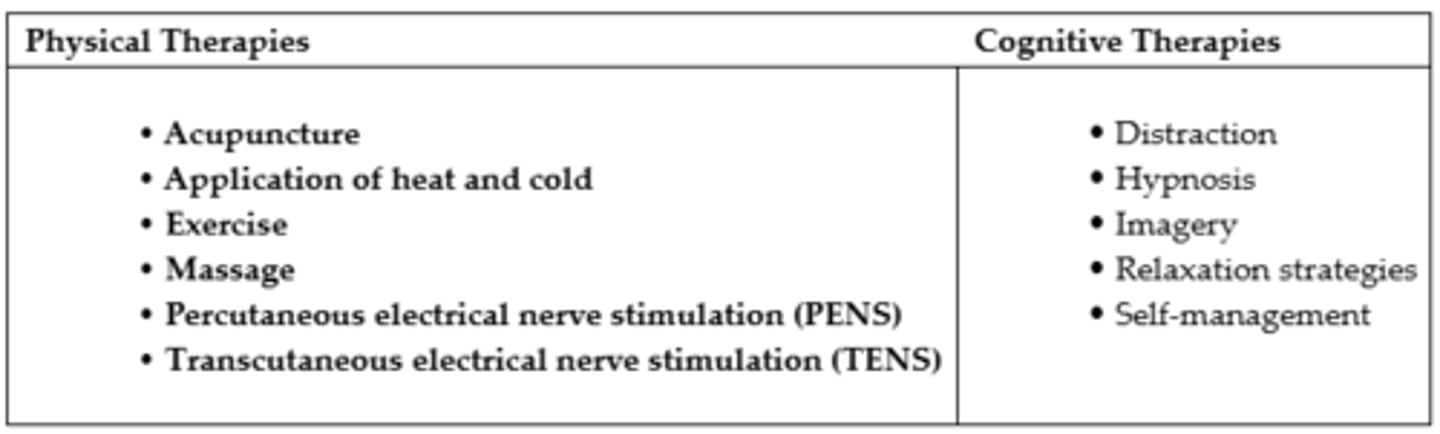

Nonpharmacological Therapies for Pain

Physical Pain Relief Strategies

Massage:

- Examples include moving the hands or fingers over the skin slowly or briskly with long strokes or in circles (superficial massage) or applying firm pressure to the skin to maintain contact while massaging the underlying tissues (deep massage)

- Specific massage techniques include acupressure and trigger-point massage

Exercise:

- Many patients become physically deconditioned as a result of their pain, which in turn can exacerbate pain

- Exercise acts through many mechanisms to relieve pain: It enhances circulation and cardiovascular fitness, reduces edema, increases muscle strength and flexibility, and enhances physical and psychosocial functioning

Turning & Repositioning:

- Health care providers should turn and position patients frequently, every 2 hours, to promote circulation and comfort

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS):

- An electric current is delivered through electrodes applied to the skin surface over the painful region, at trigger points, or over a peripheral nerve

- TENS may be used for acute pain, including postoperative pain, visceral pain, and pain associated with physical trauma

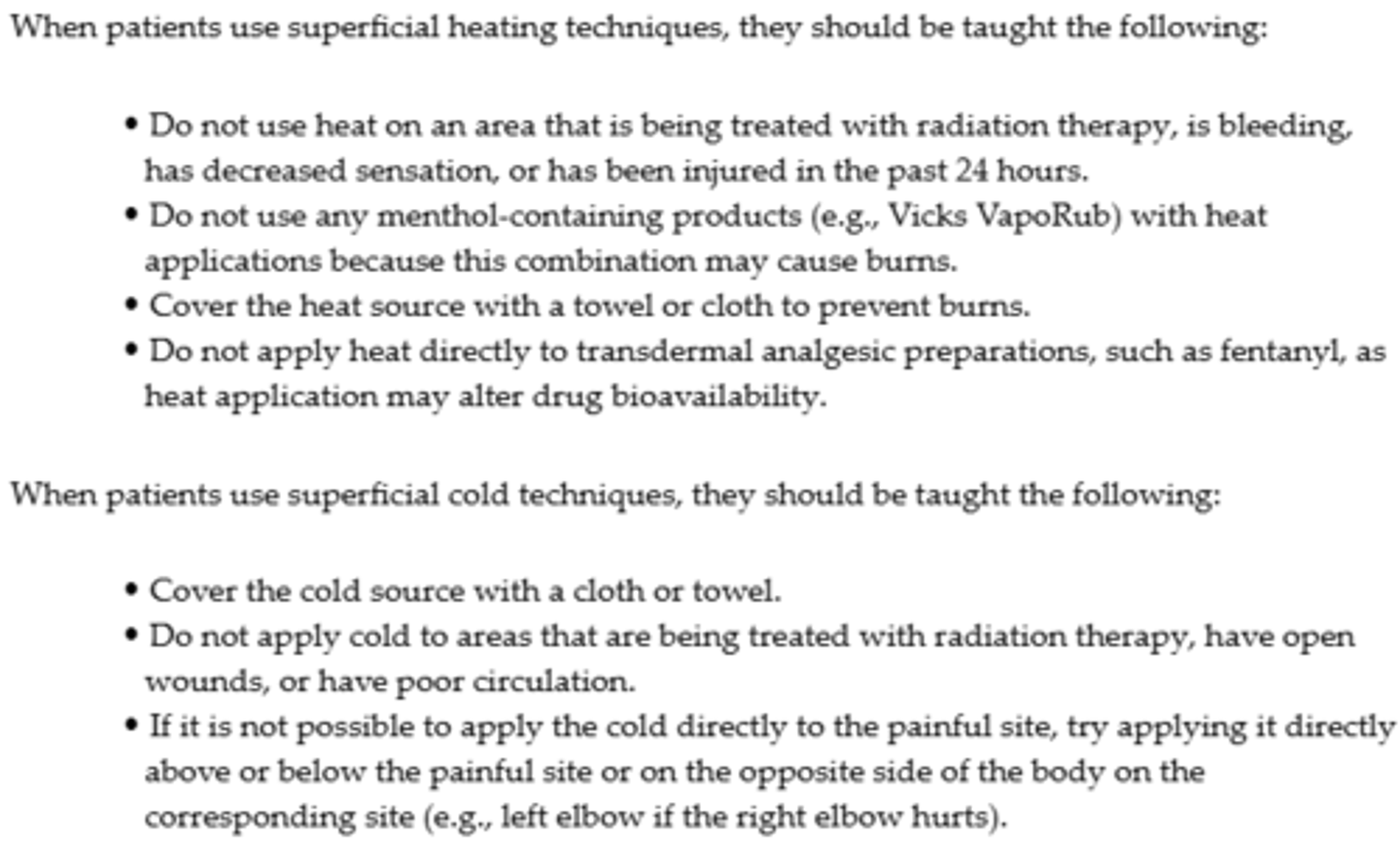

Heat Therapy:

- The premise is that applying heat to skin will increase blood flow and reduce pain-related neurotransmitter activity

- Superficial heat can be applied through an electric heating pad (dry or moist), a hot pack, hot moist compresses, or a hot water bottle

- For exposure to large areas of the body, patients can immerse themselves in a hot bath, shower, or whirlpool

Application of Cold:

- Cold therapy competes for nerve transmission and reduces sensation, effects that can be especially helpful for pain that resembles a burning sensation

Patient & Caregiver Teaching Guide Application of Heat & Cold

Cognitive Techniques

Distraction:

- The redirection of attention on something other than the pain is a simple but powerful strategy to relieve pain

- Distraction-induced analgesia involves introducing competition for attention between a highly salient sensation (pain) and some other information-processing activity

Relaxation Strategies:

- Relaxation strategies are used to reduce stress, decrease acute anxiety, distract from pain, alleviate muscle tension, combat fatigue, facilitate sleep, and enhance the effectiveness of other pain relief measures

- Elicitation of the relaxation response requires a quiet environment, a comfortable position, and a mental device as a focus of concentration (ex. a word, a sound, or the breath)

Self-Management:

- Through structured rehearsal of various cognitive and behavioural self-management techniques (ex. energy conservation, pacing, sleep promotion, relaxation, communication skills, safe exercise), patients and family members learn to set realistic weekly goals that are directed at increasing overall functional capacity and emotional well-being

- Strong evidence supports the effectiveness of self-management training for (a) improving participants’ perceived self-efficacy or ability to achieve selected goals, (b) reducing pain, and (c) improving perceived quality of life

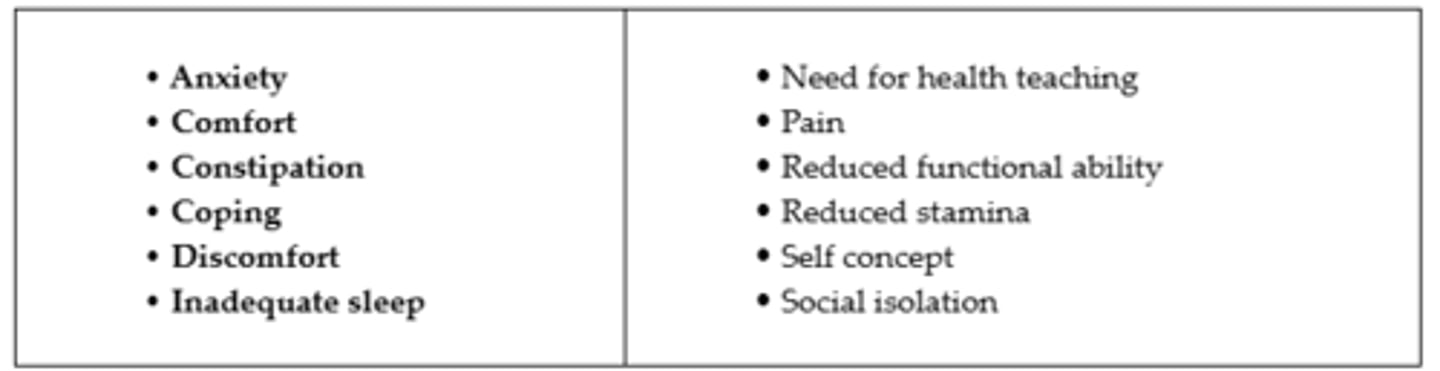

Pain-Related Nursing Diagnosis

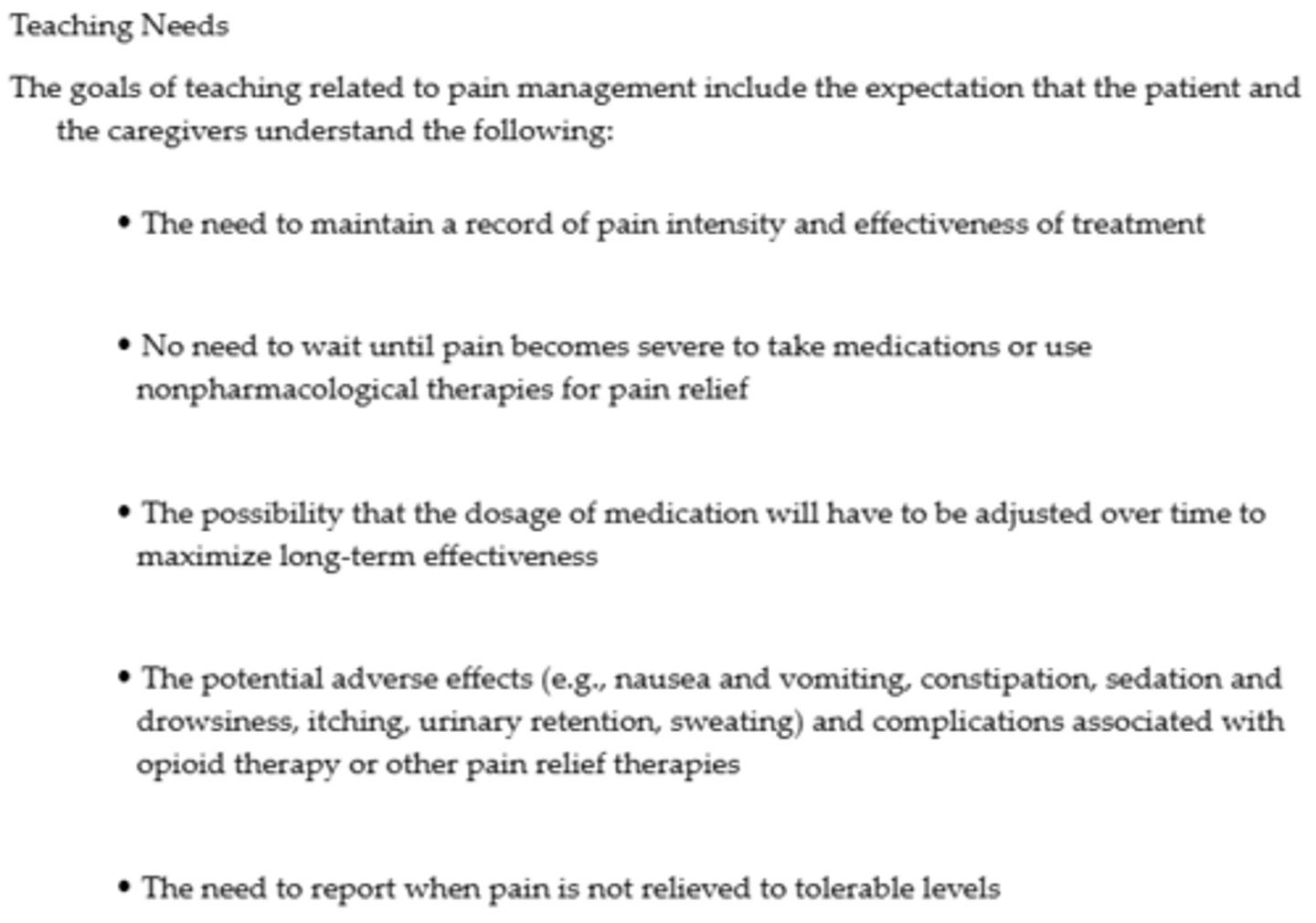

Teaching Guide for Pain Management

Tolerance

- Occurs with chronic exposure to a variety of drugs

- In the case of opioids, tolerance to analgesia is characterized by the need for an increased opioid dose to maintain the same degree of analgesia

- Although the development of tolerance to adverse effects (except constipation) is more predictable, the incidence of clinically significant analgesic opioid tolerance in patients with chronic pain is unknown, since dosage needs may increase as the disease (ex. cancer) progresses

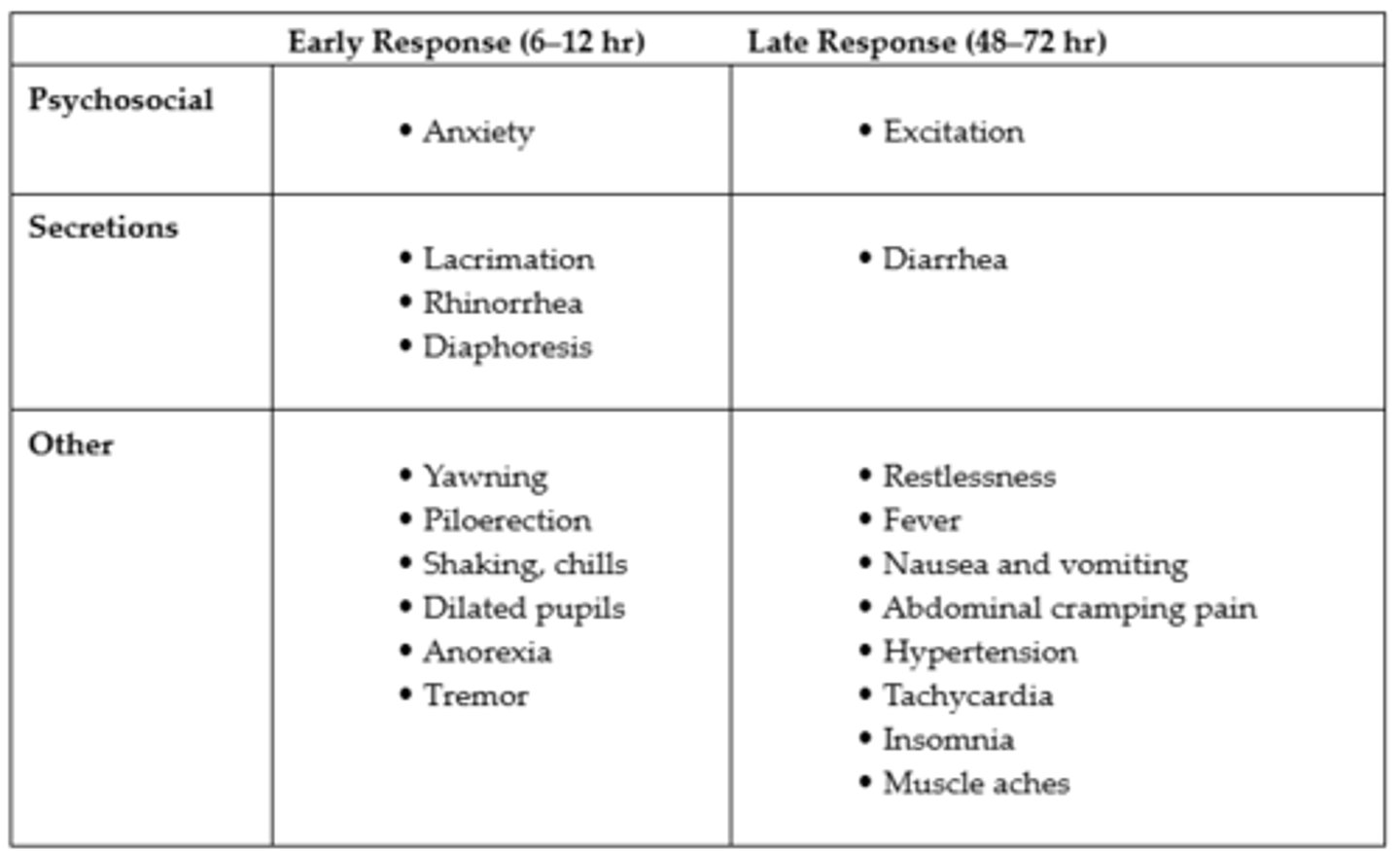

Manifestations of Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome

*Approaches to managing tolerance are (a) to increase the dosage of the analgesic, (b) to substitute another medication in the same class (e.g., changing from morphine to oxycodone), or (c) to add a medication from a different drug class that will augment pain relief without increasing adverse effects

Physical Dependence

- An expected physiological response to ongoing exposure to pharmacological agents

- It is manifested by a withdrawal syndrome when the drug is abruptly decreased

- When opioids are no longer needed to provide pain relief, a tapering schedule should be used in conjunction with careful monitoring

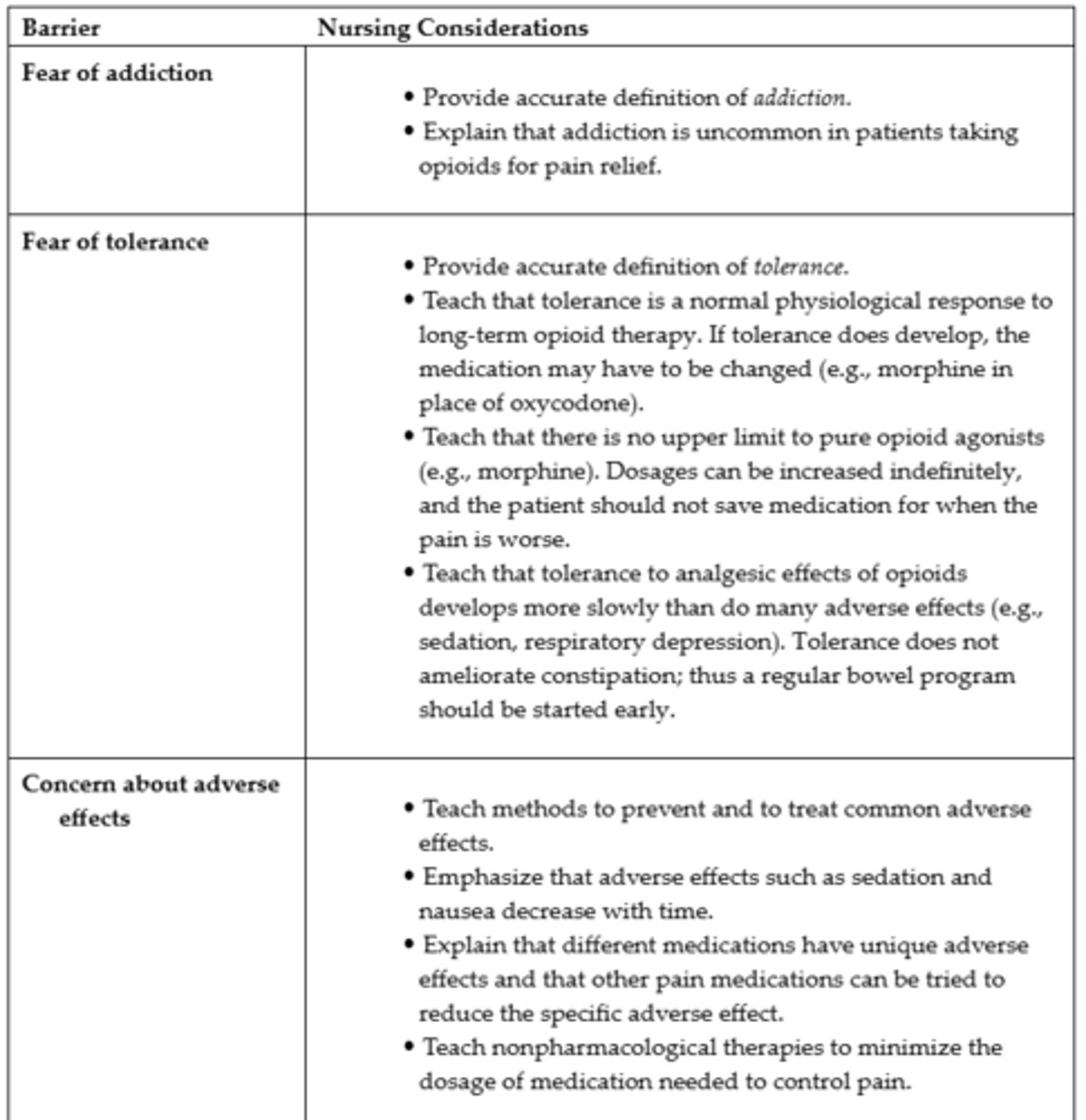

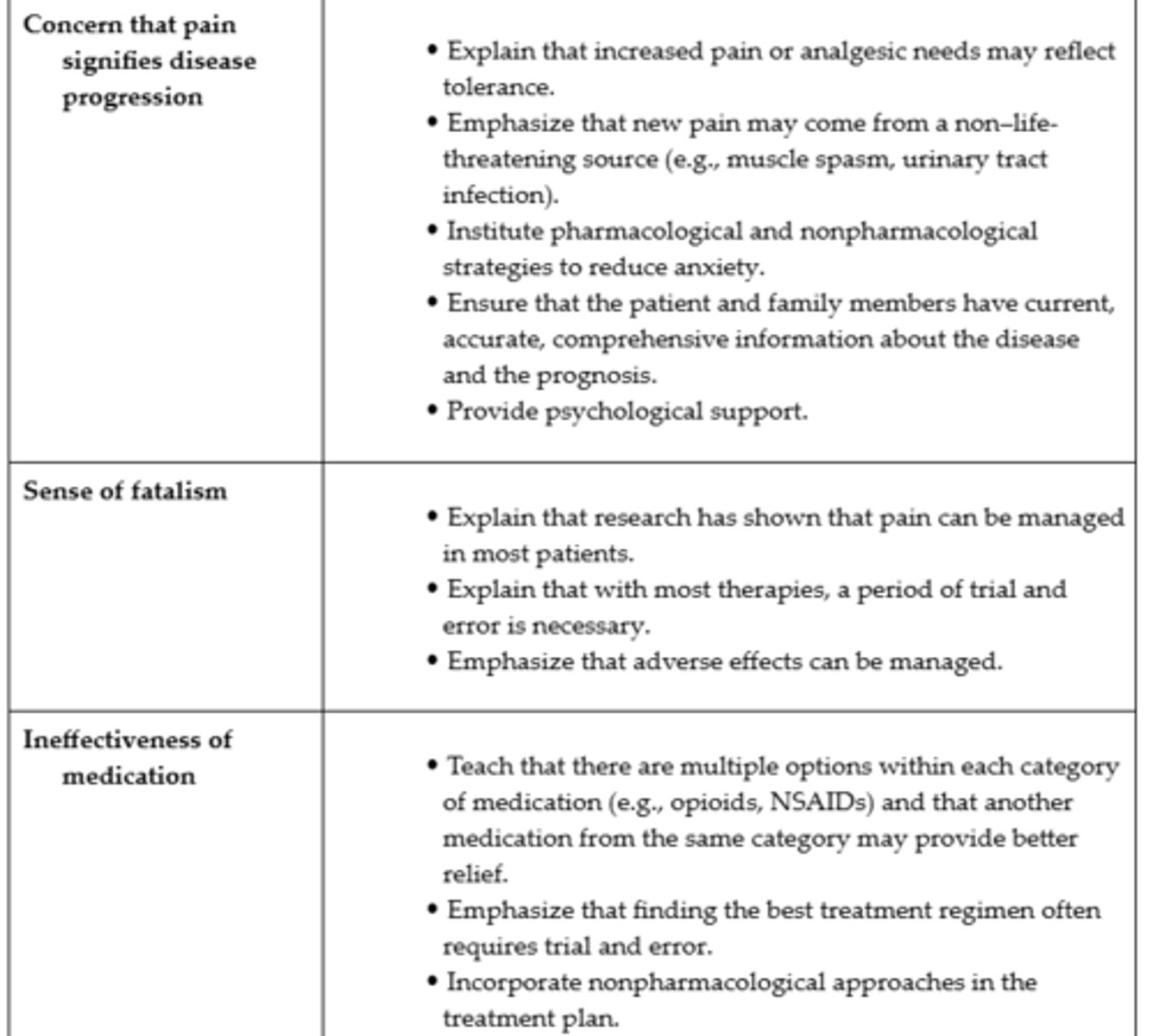

Teaching Guide Reducing Patient-Related Barriers to Pain Management #1

Teaching Guide Reducing Patient-Related Barriers to Pain Management #2

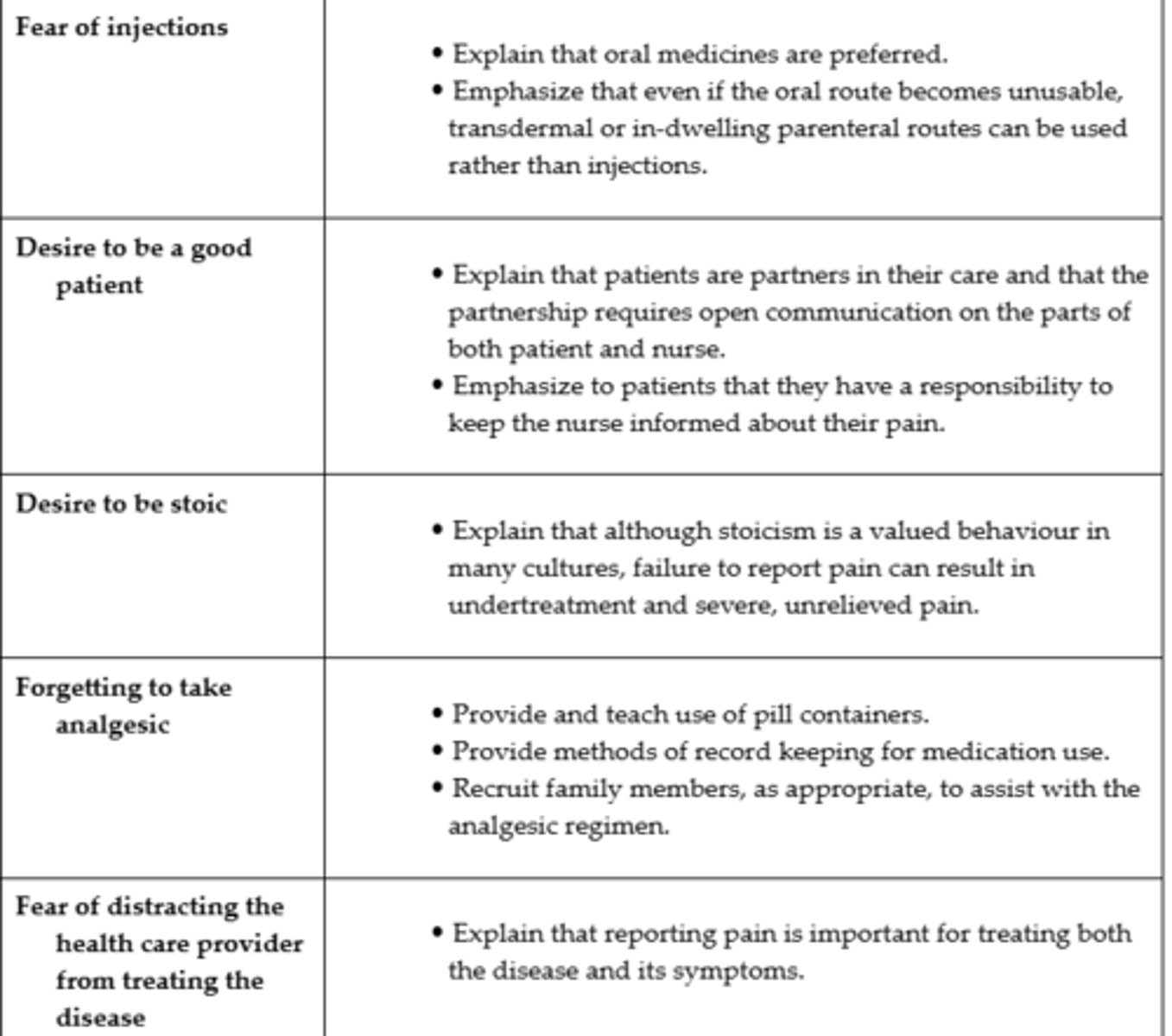

Teaching Guide Reducing Patient-Related Barriers to Pain Management #3

Rule of Double Effect

- That if an unwanted consequence (ex. hastened death) occurs as a result of an action taken to achieve a moral good (ex. pain relief), the action is justified according to ethical theory

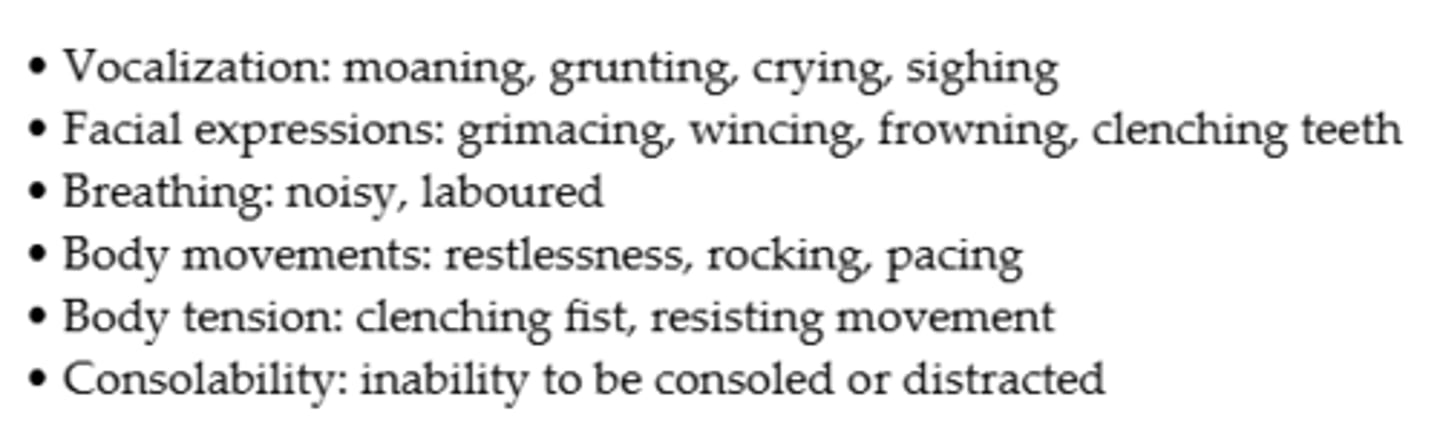

Assessment of Pain in Cognitively Impaired Older Patients

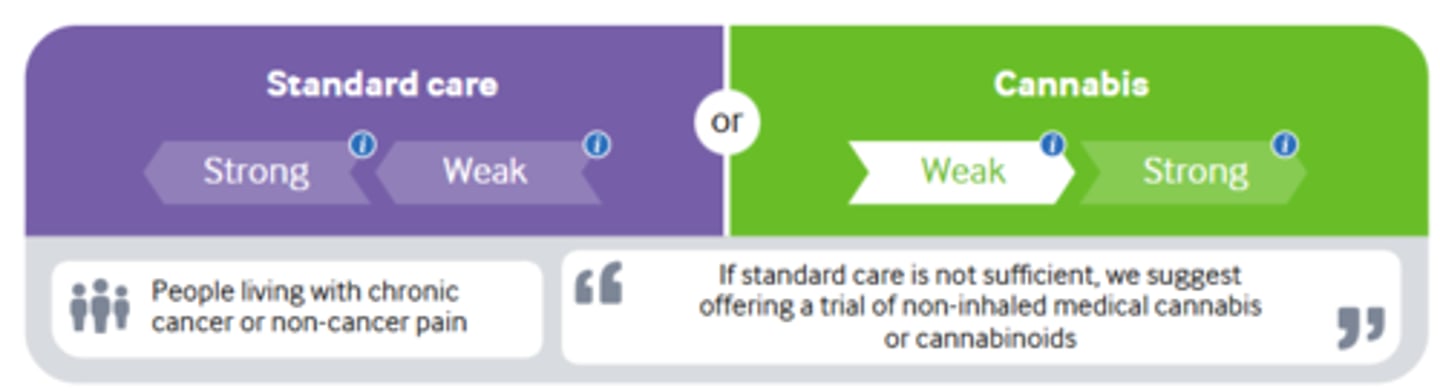

BMJ - Medical Cannabis or Cannabinoids for Chronic Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

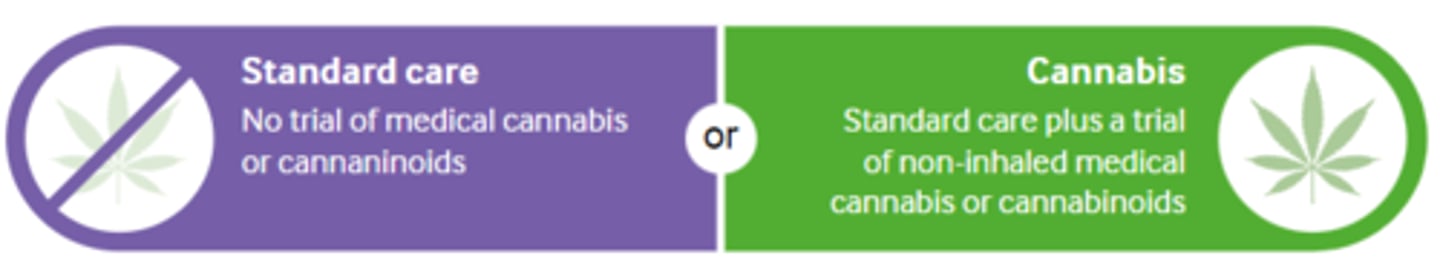

Intervention of Cannabis

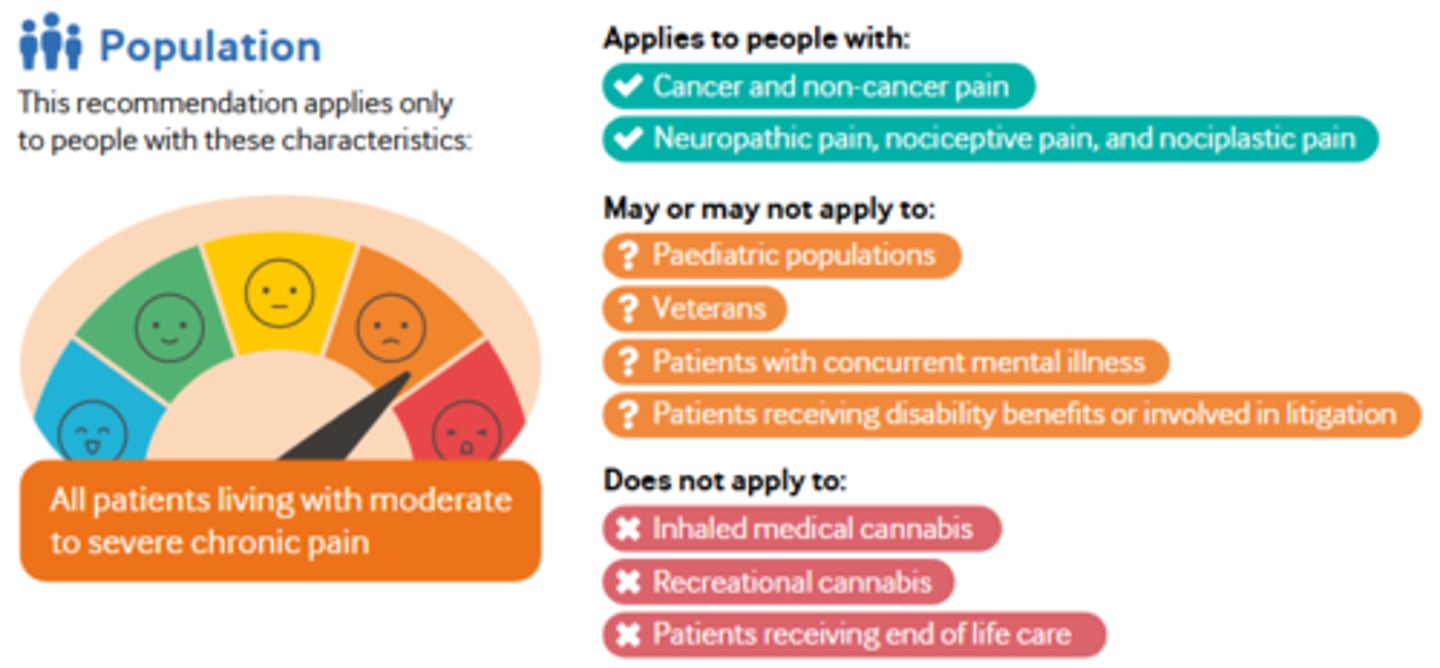

Population for Cannabis Intervention

Recommendations for Cannabis Intervention

Standard Care:

- Weak = Most people would likely want the intervention to the left. Benefits would outweigh harms for the majority, but not for everyone

- Strong = All or nearly all informed people would likely want the intervention to the left. Benefits would outweigh harms for almost everyone

Cannabis:

- Weak = Most people would likely want the intervention to the right. Benefits would outweigh harms for the majority, but not for everyone

- Strong = All or nearly all informed people would likely want the intervention to the right. Benefits would outweigh harms for almost everyone