mod 3 / ch. 20 quattrocento period of renaissance art

0.0(0)

Card Sorting

1/87

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Study Analytics

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

88 Terms

1

New cards

15th Century Italian Art

next you will learn about the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance. More specifically, we will study the developments in naturalism and perspective. You will be introduced to artists such as Donatello, Ghiberti, and Brunelleschi.

\

15th century Italian Art is the art of the 1400s also known in Italian as Quattrocento. The Renaissance is defined as the rebirth of antiquity. Some art historians think of this period more so as a reinterpretation of antiquity in which humanism impacts philosophical thought and the arts. As opposed to the Middle Ages, where artists worked in guilds, in the Renaissance we see the rise of the individual artist. The age is also marked by new leisure and the rise of wealth among families such as the Medici. The Medici were great patrons of the arts and serve to highlight the importance of the context of the work of art as reflecting the history, culture, and society in which it was made, and its purpose.

\

15th century Italian Art is the art of the 1400s also known in Italian as Quattrocento. The Renaissance is defined as the rebirth of antiquity. Some art historians think of this period more so as a reinterpretation of antiquity in which humanism impacts philosophical thought and the arts. As opposed to the Middle Ages, where artists worked in guilds, in the Renaissance we see the rise of the individual artist. The age is also marked by new leisure and the rise of wealth among families such as the Medici. The Medici were great patrons of the arts and serve to highlight the importance of the context of the work of art as reflecting the history, culture, and society in which it was made, and its purpose.

2

New cards

\

terms

terms

**atmospheric perspective** - Atmospheric, or aerial, perspective creates the illusion of distance by the greater diminution of color intensity, the shift in color toward an almost neutral blue, and the blurring of contours as the intended distance between eye and object increases.

**continuous narrative** - Narrative that presents different events in time within the same work of art.

**contrapposto** - The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counter positioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called "weight shift" because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other.

**Humanism** - In the Renaissance, an emphasis on education and on expanding knowledge (especially of classical antiquity), the exploration of individual potential and a desire to excel, and a commitment to civic responsibility and moral duty.

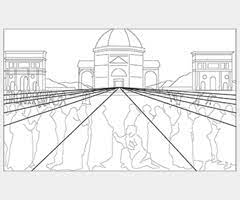

**l****inear perspective** - A method of presenting an illusion of the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. In linear perspective, the most common type, all parallel lines or surface edges converge on one, two, or three vanishing points located with reference to the eye level of the viewer (the horizon line of the picture), and associated objects are rendered smaller the farther from the viewer they are intended to seem.

**niche** - An ornamental recess in a wall or the like, usually semicircular in plan and arched, as for a statue or other decorative object.

**predella** - The narrow ledge on which an *altarpiece* rests on an altar.

**quatrefoil** - A shape or plan in which the parts assume the form of a cloverleaf.

**Renaissance** - French, "rebirth." The term used to describe the history, culture, and art of 14th through the 16th century Western Europe during which artists consciously revived the classical style.

**schiacciato** - squashed relief, very low relief practiced by ^^Donatello.^^

**continuous narrative** - Narrative that presents different events in time within the same work of art.

**contrapposto** - The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counter positioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called "weight shift" because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other.

**Humanism** - In the Renaissance, an emphasis on education and on expanding knowledge (especially of classical antiquity), the exploration of individual potential and a desire to excel, and a commitment to civic responsibility and moral duty.

**l****inear perspective** - A method of presenting an illusion of the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. In linear perspective, the most common type, all parallel lines or surface edges converge on one, two, or three vanishing points located with reference to the eye level of the viewer (the horizon line of the picture), and associated objects are rendered smaller the farther from the viewer they are intended to seem.

**niche** - An ornamental recess in a wall or the like, usually semicircular in plan and arched, as for a statue or other decorative object.

**predella** - The narrow ledge on which an *altarpiece* rests on an altar.

**quatrefoil** - A shape or plan in which the parts assume the form of a cloverleaf.

**Renaissance** - French, "rebirth." The term used to describe the history, culture, and art of 14th through the 16th century Western Europe during which artists consciously revived the classical style.

**schiacciato** - squashed relief, very low relief practiced by ^^Donatello.^^

3

New cards

Important Historical Events and People:

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

* ^^**Giangaleazzo Viscont**^^i of Milan in 1401 surrounded Florence with his troops and died mysteriously in 1402. This relates to the commission of Ghiberti's first set of doors.

* Arte de la Calimala (Wool merchant's guild) has panel competition for East doors later moved to North of baptistery.

* King Ladislaus of Naples threatened to overrun Florence around 1409 and dies in 1414. In 1406 there is a dictum set in place for the completion of the sculptures of Or San Michele.

* Patrons Pietro & Felice Brancacci payed for the Brancacci Chapel. The subject is found in the Gospel of Matthew and relates to the tax collection in Caperneum. There was also a local tax, catasto, or perhaps a church taxation during the Renaissance that can relate to the rare art historical subject.

* Other Patrons: ^^**Palla Strozzi, The Medici, Lenzi**^^

* Arte de la Calimala (Wool merchant's guild) has panel competition for East doors later moved to North of baptistery.

* King Ladislaus of Naples threatened to overrun Florence around 1409 and dies in 1414. In 1406 there is a dictum set in place for the completion of the sculptures of Or San Michele.

* Patrons Pietro & Felice Brancacci payed for the Brancacci Chapel. The subject is found in the Gospel of Matthew and relates to the tax collection in Caperneum. There was also a local tax, catasto, or perhaps a church taxation during the Renaissance that can relate to the rare art historical subject.

* Other Patrons: ^^**Palla Strozzi, The Medici, Lenzi**^^

4

New cards

Masaccio and Brunelleschi

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

**Linear Perspective:**

Masaccio and Brunelleschi are seen as innovators in their respective fields of a painting and architecture. Their works reached new heights with the fine tuning and exploration of linear perspective. Filippo Brunelleschi, who lost the competition for the baptistery doors against Lorenzo Ghiberti, is credited with the invention of linear perspective.

Masaccio's innovations in fresco painting include linear and atmospheric perspective as well as improvements in the lifelike quality of figures and their modeling with the use of shadows. This can be seen in the Brancacci Chapel and Holy Trinity frescoes. Brunelleschi was able to span the 140 foot opening of the Florence Cathedral by constructing a double shelled dome with 8 exterior ribs.

Masaccio and Brunelleschi are seen as innovators in their respective fields of a painting and architecture. Their works reached new heights with the fine tuning and exploration of linear perspective. Filippo Brunelleschi, who lost the competition for the baptistery doors against Lorenzo Ghiberti, is credited with the invention of linear perspective.

Masaccio's innovations in fresco painting include linear and atmospheric perspective as well as improvements in the lifelike quality of figures and their modeling with the use of shadows. This can be seen in the Brancacci Chapel and Holy Trinity frescoes. Brunelleschi was able to span the 140 foot opening of the Florence Cathedral by constructing a double shelled dome with 8 exterior ribs.

5

New cards

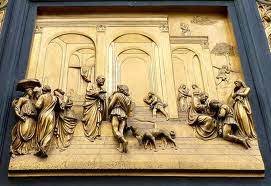

The Gates of Paradise

**The Competition**:

A competition was held by the city's guild of wool merchants to find an artist for the east portal of the Baptistry of San Giovanni for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. The event highlights the importance of the individual artist, the rise of patronage as civic responsibility and promotional tool, and advancements in perspective all the while commemorating the spirit of competition in the Renaissance.

**The Subject:**

The subject of the competition panel was the Sacrifice of Isaac, an Old Testament subject from the Book of Genesis in which Abraham is ordered by God to sacrifice his son Isaac. An angel intervenes to stop him just as he is about plunge the knife into Isaac's throat. This theme of self- sacrifice has been connected to Giangaleazzo Visconti's attempted invasion of Florence in which city officials called upon the people to defend themselves from Milanese forces.

**The Winner**:

The competition panels that you will be comparing and contrasting show the predetermined subject of the sacrifice of Isaac in a quatrefoil form. The two panels from the finalists, Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti, survive out of a total seven semifinalists that were considered. Ghiberti won the competition and his completed doors where moved to the north portal of the baptistery. His second set of doors are known as the "Gates of Paradise" because among many legends they face an area known as Paradise between the baptistery and the cathedral.

**The Gates:**

In the "Gates of Paradise" the quatrefoil form is abandoned in favor of the square that allows for the better use of perspective. The door has ten panels with subjects from the Old Testament. The panels are read from left to right, top to bottom, and demonstrate linear perspective with in each panel and overall as seen from a standing position in front of the doors. The doors also include a portrait of Ghiberti who was proud of his accomplishment.

A competition was held by the city's guild of wool merchants to find an artist for the east portal of the Baptistry of San Giovanni for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. The event highlights the importance of the individual artist, the rise of patronage as civic responsibility and promotional tool, and advancements in perspective all the while commemorating the spirit of competition in the Renaissance.

**The Subject:**

The subject of the competition panel was the Sacrifice of Isaac, an Old Testament subject from the Book of Genesis in which Abraham is ordered by God to sacrifice his son Isaac. An angel intervenes to stop him just as he is about plunge the knife into Isaac's throat. This theme of self- sacrifice has been connected to Giangaleazzo Visconti's attempted invasion of Florence in which city officials called upon the people to defend themselves from Milanese forces.

**The Winner**:

The competition panels that you will be comparing and contrasting show the predetermined subject of the sacrifice of Isaac in a quatrefoil form. The two panels from the finalists, Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti, survive out of a total seven semifinalists that were considered. Ghiberti won the competition and his completed doors where moved to the north portal of the baptistery. His second set of doors are known as the "Gates of Paradise" because among many legends they face an area known as Paradise between the baptistery and the cathedral.

**The Gates:**

In the "Gates of Paradise" the quatrefoil form is abandoned in favor of the square that allows for the better use of perspective. The door has ten panels with subjects from the Old Testament. The panels are read from left to right, top to bottom, and demonstrate linear perspective with in each panel and overall as seen from a standing position in front of the doors. The doors also include a portrait of Ghiberti who was proud of his accomplishment.

6

New cards

Or San Michele

**Patronage:**

* __This building illustrates clearly the connection between patronage and the work of art.__

* It also serves as a good visual summary of the major sculptors working during the **quattrocento.**

* %%**Or San Michele**%% was __**multi-functional building**____, it housed a miracle working image of the Madonna created by Orcanga, it was a granary, and meeting place for the guilds. As a meeting place for the guilds it also allowed for the exterior display of sculptures in niches that functioned much like a modern-day billboard.__

* These images advertised the guilds, their patron saints, and the products they produced.

* __This building illustrates clearly the connection between patronage and the work of art.__

* It also serves as a good visual summary of the major sculptors working during the **quattrocento.**

* %%**Or San Michele**%% was __**multi-functional building**____, it housed a miracle working image of the Madonna created by Orcanga, it was a granary, and meeting place for the guilds. As a meeting place for the guilds it also allowed for the exterior display of sculptures in niches that functioned much like a modern-day billboard.__

* These images advertised the guilds, their patron saints, and the products they produced.

7

New cards

Donatello's David

Case Study:

This work is the first full sized nude figure since antiquity. The subject of David is important because the Old Testament hero that defeated Goliath was seen as a symbol of the Florentine Republic. The work does not have a secure patron nor date but is believed to have been made for the wedding of Piero de' Medici. Its' complicated iconography has been long debated by art historians and is referred to as homoerotic. The introspective figure is shown in a contrapposto stance wearing a petasus (shepherd's hat), and greaves while carrying a sword and a rock.

This work is the first full sized nude figure since antiquity. The subject of David is important because the Old Testament hero that defeated Goliath was seen as a symbol of the Florentine Republic. The work does not have a secure patron nor date but is believed to have been made for the wedding of Piero de' Medici. Its' complicated iconography has been long debated by art historians and is referred to as homoerotic. The introspective figure is shown in a contrapposto stance wearing a petasus (shepherd's hat), and greaves while carrying a sword and a rock.

8

New cards

Doumo in florence (1420-36)

built by brunelleschi who is said to have invented perspective in the renaissance

9

New cards

Ghiberti

won the competition for the east baptistry doors in 1401-2

10

New cards

Nanni di Banco (c. 1385–1421)

In about 1409, Nanni di Banco (c. 1385–1421), son of a sculptor in the Florence Cathedral workshop, was commissioned by the stonecarver and woodworkers’ guild (to which he himself belonged) to produce THE FOUR CROWNED MARTYRS (FIG. 20–12)

11

New cards

lenzi family

commissioned masaccio to paint the holy trinity fresco in 1428

12

New cards

Who cast the bronze "David" dated to 1420-50s patronized by the Medici?

Donatello

13

New cards

Lorenzo Ghiberti

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* **Born**: Lorenzo di Bartolo; 1378 \n Florence, Republic of Florence

* **Died:** 1 December 1455 (aged 73–74) \n Florence, Republic of Florence

* **Nationality:** Italian

* **Known for**: __Sculpture__

* **Notable work:** Gates of Paradise, Florence Baptistery

* **Movement:** Early Renaissance

* **Died:** 1 December 1455 (aged 73–74) \n Florence, Republic of Florence

* **Nationality:** Italian

* **Known for**: __Sculpture__

* **Notable work:** Gates of Paradise, Florence Baptistery

* **Movement:** Early Renaissance

14

New cards

Four Crowned Martyrs (Nanni di Banco)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* **Artist:** Nanni di Banco

Four Crowned Martyrs is a sculptural group by Nanni di Banco. It forms part of a cycle of fourteen sculptures commissioned by the guilds of Florence for external niches of Orsanmichele, each sculpture showing that guild's patron saint.

\

Four Crowned Martyrs is a sculptural group by Nanni di Banco. It forms part of a cycle of fourteen sculptures commissioned by the guilds of Florence for external niches of Orsanmichele, each sculpture showing that guild's patron saint.

\

15

New cards

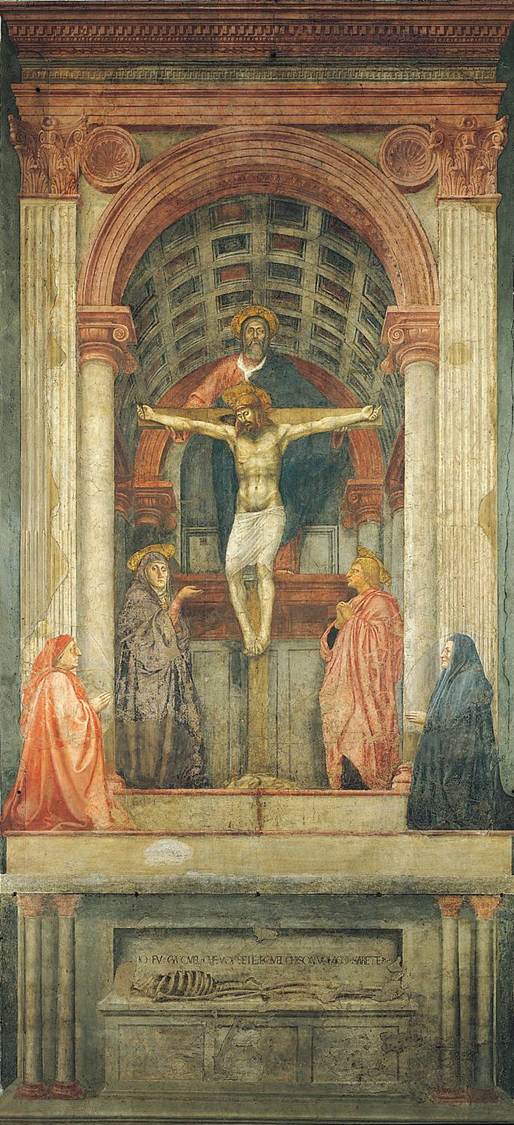

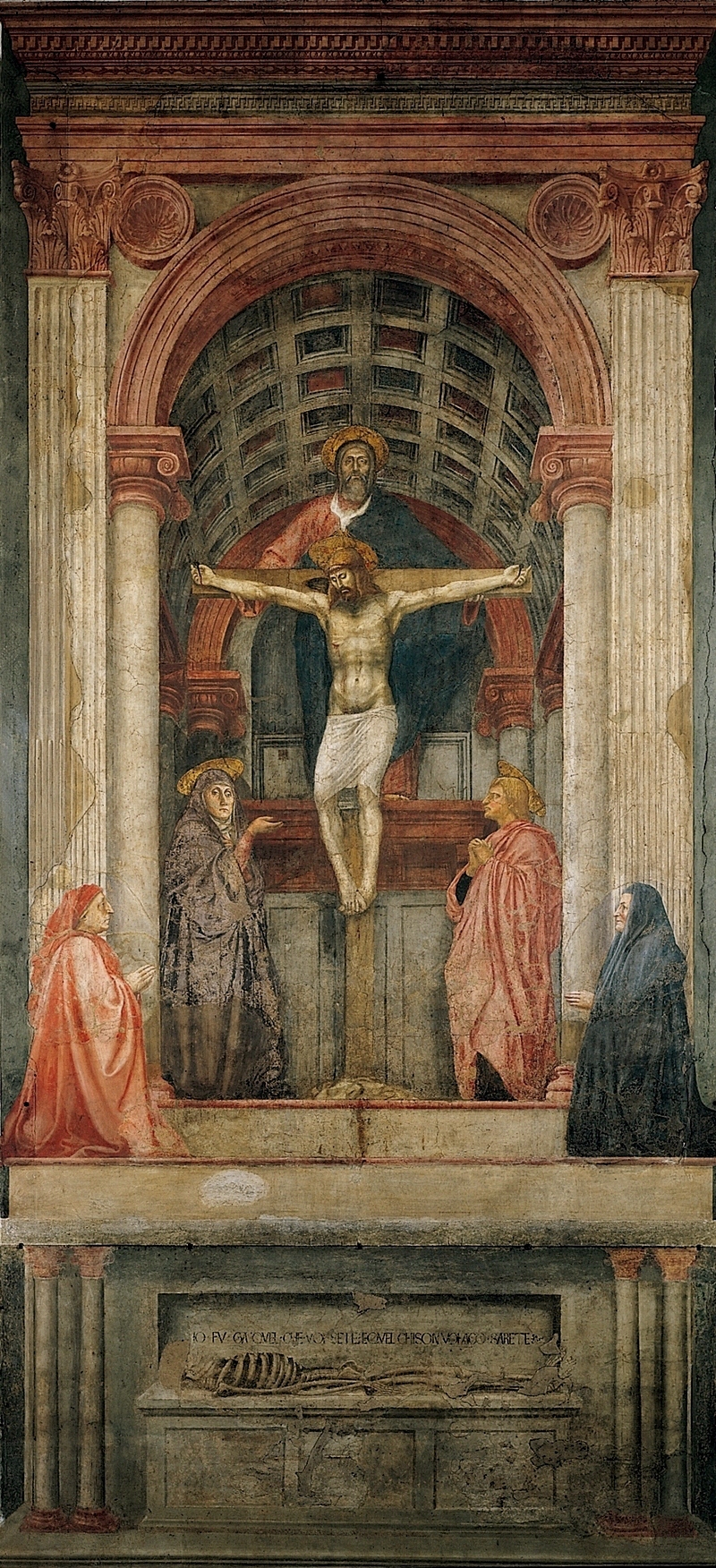

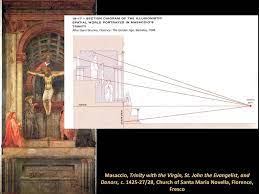

Holy Trinity (Masaccio)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* **Artist:** Masaccio

* **Year:** c.1426-1428

* **Type:** fresco

* **Dimensions**: 667 cm × 317 cm (263 in × 125 in)

* **Location:** Santa Maria Novella, Florence

* **Year:** c.1426-1428

* **Type:** fresco

* **Dimensions**: 667 cm × 317 cm (263 in × 125 in)

* **Location:** Santa Maria Novella, Florence

16

New cards

Florence Cathedral

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* **Architect(s)**: Arnolfo di Cambio, Filippo Brunelleschi, Emilio De Fabris

* **Architectural type:** Church

* **Style**: Gothic, Romanesque, \n Renaissance

* **Groundbreaking:** 9 September 1296

* **Completed:** 1436

* **Architectural type:** Church

* **Style**: Gothic, Romanesque, \n Renaissance

* **Groundbreaking:** 9 September 1296

* **Completed:** 1436

17

New cards

*David* (Donatello)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* **Artist:** Donatello

* **Period:** Early North Renaissance

\

David is the title of two statues of the biblical hero David by the Italian Early Renaissance sculptor Donatello. They consist of an early work in marble of a clothed figure, and a far more famous bronze figure that is nude except for helmet and boots, and dates to the 1440s or later.

* **Period:** Early North Renaissance

\

David is the title of two statues of the biblical hero David by the Italian Early Renaissance sculptor Donatello. They consist of an early work in marble of a clothed figure, and a far more famous bronze figure that is nude except for helmet and boots, and dates to the 1440s or later.

18

New cards

*The Birth of Venus*

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(FLORENTINE ART IN 2ND HALF OF 15TH CENTURY)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(FLORENTINE ART IN 2ND HALF OF 15TH CENTURY)**==

* **Artist:** Sandro Botticelli

* **Dimensions:** 5′ 8″ x 9′ 2″

* **Location:** Uffizi Gallery

* **Created:** 1485–1486

* **Genre:** History painting

* **Subject:** Venus

* **Periods:** Renaissance, Italian Renaissance, Florentine painting, Early renaissance

\

The Birth of Venus is a painting by the Italian artist Sandro Botticelli, probably executed in the mid 1480s. It depicts the goddess Venus arriving at the shore after her birth, when she had emerged from the sea fully-grown. The painting is in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

* **Dimensions:** 5′ 8″ x 9′ 2″

* **Location:** Uffizi Gallery

* **Created:** 1485–1486

* **Genre:** History painting

* **Subject:** Venus

* **Periods:** Renaissance, Italian Renaissance, Florentine painting, Early renaissance

\

The Birth of Venus is a painting by the Italian artist Sandro Botticelli, probably executed in the mid 1480s. It depicts the goddess Venus arriving at the shore after her birth, when she had emerged from the sea fully-grown. The painting is in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

19

New cards

renaissance art in the fifteenth-century italy

This ferocious but bloodless battle seems to take place in a dream, but it depicts a historical event (FIG. 20–1). Under an elegantly fluttering banner, the Florentine general Niccolò da Tolentino leads his men against the Sienese at the Battle of San Romano, which took place on June 1, 1432. The battle rages across a shallow stage defined by the debris of warfare arranged in a neat pattern on a pink ground and backed by blooming hedges. In the center foreground, Niccolò holds up a baton of command, the sign of his authority. His bold gesture—together with his white horse and crimson-and-gold damask hat—ensures that he dominates the scene. His knights charge into the fray, and when they fall, like the soldier at the lower left, they join the many broken lances on the ground—all in conformity with the new mathematical depiction of receding space called linear perspective, posed to align with implied lines that converge at a single point on the horizon. An eccentric Florentine painter nicknamed Paolo Uccello (“Paul Bird”) created the panel painting (SEE FIG. 20–24) from which the detail in FIGURE 20–1 is taken. It is one of three related panels—now separated, hanging in major museums in Florence, London, and Paris—commissioned by Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni (1404–1479), who led the Florentine governing Council of Ten during the war against Lucca and Siena. Uccello’s remarkable accuracy when depicting armor from the 1430s, heraldic banners, and even fashionable fabrics and crests surely would have appealed to Lionardo’s civic pride. The hedges of oranges, roses, and pomegranates—all ancient fertility symbols—suggest that Lionardo might have commissioned the paintings at the time of his wedding in 1438. Lionardo and his wife, Maddalena, had six sons, two of whom inherited the paintings. According to a later complaint brought by Damiano, one of the heirs, Lorenzo de’ Medici, the powerful de facto ruler of Florence, “forcibly removed” the paintings from Damiano’s house. They were never returned, and Uccello’s masterpieces are recorded in a 1492 inventory as hanging in the Medici palace. Perhaps Lorenzo, who was called “the Magnificent,” saw Uccello’s heroic pageant as a trophy more worthy of a Medici merchant prince. Princely patronage was certainly a major factor in the genesis of the Italian Renaissance as it developed in Florence during the early years of the fifteenth century

20

New cards

Humanism and the Italian Renaissance

__***What are the cultural and historical backgrounds of Italian Renaissance art and architecture?***__

By the end of the Middle Ages, the most important Italian cultural centers lay north of Rome in the cities of Florence, Milan, and Venice, and in the smaller court cities of Mantua, Ferrara, and Urbino. Political power and artistic patronage were both dominated by wealthy families: the Medici in Florence, the Montefeltro in Urbino, the Gonzaga in Mantua, the Visconti and Sforza in Milan, and the Este in Ferrara (MAP 20–1). Cities grew in wealth and independence as people migrated from the countryside in unprecedented numbers. Like in northern Europe, commerce became increasingly important. Money conferred status, and a shrewd business or political leader could become very powerful. The period saw the rise of mercenary armies led by entrepreneurial (and sometimes brilliant) military commanders called condottieri, who owed allegiance only to those who paid them well; their employer might be a city-state, a lord, or even the pope. Some condottieri, like Niccolò da Tolentino (SEE FIG. 20–1), became rich and famous. Others, like Federico da Montefeltro (SEE FIG. 20–39), were lords or dukes themselves, with territories of their own in need of protection. Patronage of the arts was an important public activity with political overtones. As one Florentine merchant, Giovanni Rucellai, succinctly noted, he supported the arts “because they serve the glory of God, the honour of the city, and the commemoration of myself” (cited in Baxandall, p. 2). The term Renaissance (French for “rebirth”) was only applied to this period by later historians. However, its origins lie in the thought of Petrarch and other fourteenth-century Italian writers, who emphasized the power and potential of human beings for great individual accomplishment. These Italian humanists also looked back at the thousand years extending from the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire to their own day and determined that the achievements of the Classical world were followed by what they perceived as a period of decline—a “middle” or “dark” age. They proudly saw their own era as a third age characterized by a revival or rebirth (“renaissance”), when humanity began to emerge from what they erroneously saw as intellectual and cultural stagnation to appreciate once more the achievement of the ancients and the value of rational, scientific investigation. They looked to the accomplishments of the Classical past for inspiration and instruction, and in Italy this centered on the heritage of ancient Rome. They sought the physical and literary records of the ancient world—assembling libraries, collecting sculpture and fragments of architecture, and beginning archaeological investigations. Their aim was to live a rich, noble, and productive life—usually within the framework of Christianity, but always adhering to a school of philosophy as a moral basis. Artists, like the humanists, turned to Classical antiquity for inspiration, emulating ancient Roman sculpture and architecture even as they continued to fulfill commissions for predominantly Christian subjects and buildings. But a number of home furnishings from the secular world, such as birth trays and marriage chests, have survived, richly painted with allegorical and mythological themes. Patrons began to collect art for their personal enjoyment. Like Flemish artists, Italian painters and sculptors increasingly focused their attention on rendering the illusion of physical reality. They did so in a more analytical way than the northerners. Rather than seeking to describe the visual appearance of nature through luminosity and detailed textural differentiation, Italian artists aimed at achieving lifelike but idealized weighty figures set in a space organized through strict adherence to linear perspective, a mathematical system that gave the illusion of a measured and continuously receding space (see “Renaissance Perspective” on page 623).

By the end of the Middle Ages, the most important Italian cultural centers lay north of Rome in the cities of Florence, Milan, and Venice, and in the smaller court cities of Mantua, Ferrara, and Urbino. Political power and artistic patronage were both dominated by wealthy families: the Medici in Florence, the Montefeltro in Urbino, the Gonzaga in Mantua, the Visconti and Sforza in Milan, and the Este in Ferrara (MAP 20–1). Cities grew in wealth and independence as people migrated from the countryside in unprecedented numbers. Like in northern Europe, commerce became increasingly important. Money conferred status, and a shrewd business or political leader could become very powerful. The period saw the rise of mercenary armies led by entrepreneurial (and sometimes brilliant) military commanders called condottieri, who owed allegiance only to those who paid them well; their employer might be a city-state, a lord, or even the pope. Some condottieri, like Niccolò da Tolentino (SEE FIG. 20–1), became rich and famous. Others, like Federico da Montefeltro (SEE FIG. 20–39), were lords or dukes themselves, with territories of their own in need of protection. Patronage of the arts was an important public activity with political overtones. As one Florentine merchant, Giovanni Rucellai, succinctly noted, he supported the arts “because they serve the glory of God, the honour of the city, and the commemoration of myself” (cited in Baxandall, p. 2). The term Renaissance (French for “rebirth”) was only applied to this period by later historians. However, its origins lie in the thought of Petrarch and other fourteenth-century Italian writers, who emphasized the power and potential of human beings for great individual accomplishment. These Italian humanists also looked back at the thousand years extending from the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire to their own day and determined that the achievements of the Classical world were followed by what they perceived as a period of decline—a “middle” or “dark” age. They proudly saw their own era as a third age characterized by a revival or rebirth (“renaissance”), when humanity began to emerge from what they erroneously saw as intellectual and cultural stagnation to appreciate once more the achievement of the ancients and the value of rational, scientific investigation. They looked to the accomplishments of the Classical past for inspiration and instruction, and in Italy this centered on the heritage of ancient Rome. They sought the physical and literary records of the ancient world—assembling libraries, collecting sculpture and fragments of architecture, and beginning archaeological investigations. Their aim was to live a rich, noble, and productive life—usually within the framework of Christianity, but always adhering to a school of philosophy as a moral basis. Artists, like the humanists, turned to Classical antiquity for inspiration, emulating ancient Roman sculpture and architecture even as they continued to fulfill commissions for predominantly Christian subjects and buildings. But a number of home furnishings from the secular world, such as birth trays and marriage chests, have survived, richly painted with allegorical and mythological themes. Patrons began to collect art for their personal enjoyment. Like Flemish artists, Italian painters and sculptors increasingly focused their attention on rendering the illusion of physical reality. They did so in a more analytical way than the northerners. Rather than seeking to describe the visual appearance of nature through luminosity and detailed textural differentiation, Italian artists aimed at achieving lifelike but idealized weighty figures set in a space organized through strict adherence to linear perspective, a mathematical system that gave the illusion of a measured and continuously receding space (see “Renaissance Perspective” on page 623).

21

New cards

The Early Renaissance in Florence

__***What characterizes the early development of Italian Renaissance architecture, sculpture, and painting in Florence?***__

In taking Uccello’s battle painting (SEE FIG. 20–1), Lorenzo de’ Medici was asserting the role his family had come to expect to play in Florence. The fifteenth century witnessed the rise of the Medici from among the most successful of anewly rich middle class (primarily merchants and bankers) to the city’s virtual rulers. Unlike the hereditary aristocracy, the Medici emerged from obscure roots to make their fortune in banking; from their money came their power. The competitive Florentine atmosphere that had fostered mercantile success and civic pride also cultivated competition in the arts and encouraged an interest in ancient literary texts. This has led many to consider Florence the cradle of the Italian Renaissance. Under Cosimo the Elder (1389–1464), the Medici became leaders in intellectual and artistic patronage. They sponsored philosophers and other scholars who wanted to study the Classics, especially the works of Plato and his followers, the Neoplatonists. Neoplatonism distinguished between the spiritual (the ideal or Idea) and the physical (Matter) and encouraged artists to represent ideal figures. But it was writers, philosophers, and musicians—and not artists—who dominated the Medici Neoplatonic circle. Architects, sculptors, and painters learned their craft in apprenticeships and were therefore considered manual laborers. Nevertheless, interest in the ancient world rapidly spread from the Medici circle to visual artists, who gradually began to see themselves as more than laborers. Florentine society soon recognized their best works as achievements of a very high order. Although the Medici were the de facto rulers, Florence was considered a republic. The Council of Ten (headed for a time by Salimbeni, who commissioned Uccello’s Battle of San Romano) was a kind of constitutional oligarchy where wealthy men formed the government. At the same time, the various guilds wielded tremendous power; guild membership was a prerequisite for holding government office. Consequently, artists could look to the Church and the state—the state including both the city government and the guilds—as well as private individuals for patronage. All these patrons expected the artists to reaffirm and glorify their achievements with works that were not only beautiful but intellectually powerful.

In taking Uccello’s battle painting (SEE FIG. 20–1), Lorenzo de’ Medici was asserting the role his family had come to expect to play in Florence. The fifteenth century witnessed the rise of the Medici from among the most successful of anewly rich middle class (primarily merchants and bankers) to the city’s virtual rulers. Unlike the hereditary aristocracy, the Medici emerged from obscure roots to make their fortune in banking; from their money came their power. The competitive Florentine atmosphere that had fostered mercantile success and civic pride also cultivated competition in the arts and encouraged an interest in ancient literary texts. This has led many to consider Florence the cradle of the Italian Renaissance. Under Cosimo the Elder (1389–1464), the Medici became leaders in intellectual and artistic patronage. They sponsored philosophers and other scholars who wanted to study the Classics, especially the works of Plato and his followers, the Neoplatonists. Neoplatonism distinguished between the spiritual (the ideal or Idea) and the physical (Matter) and encouraged artists to represent ideal figures. But it was writers, philosophers, and musicians—and not artists—who dominated the Medici Neoplatonic circle. Architects, sculptors, and painters learned their craft in apprenticeships and were therefore considered manual laborers. Nevertheless, interest in the ancient world rapidly spread from the Medici circle to visual artists, who gradually began to see themselves as more than laborers. Florentine society soon recognized their best works as achievements of a very high order. Although the Medici were the de facto rulers, Florence was considered a republic. The Council of Ten (headed for a time by Salimbeni, who commissioned Uccello’s Battle of San Romano) was a kind of constitutional oligarchy where wealthy men formed the government. At the same time, the various guilds wielded tremendous power; guild membership was a prerequisite for holding government office. Consequently, artists could look to the Church and the state—the state including both the city government and the guilds—as well as private individuals for patronage. All these patrons expected the artists to reaffirm and glorify their achievements with works that were not only beautiful but intellectually powerful.

22

New cards

The Competition Reliefs

In 1401, the building supervisors of the baptistery of Florence Cathedral decided to commission a new pair of bronze doors, funded by the powerful wool merchants’ guild. Instead of choosing a well-established sculptor with a strong reputation, a competition was announced for the commission. This prestigious project would be awarded to the artist who demonstrated the greatest talent in executing a trial piece: a bronze relief representing Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis 22:1–13) composed within the same Gothic quatrefoil framework used in Andrea Pisano’s first set of bronze doors for the baptistery, made in the 1330s (SEE FIG. 18–3). Two competition panels have survived, those submitted by the presumed finalists—Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti, both young artists in their early twenties (FIGS. 20–2, 20–3). Brunelleschi’s composition is rugged and explosive, marked by raw dramatic intensity. At the right, Abraham lunges forward, grabbing his son by the neck, while the angel swoops to stop him just as the knife is about to strike. Isaac’s awkward pose embodies his fear and struggle. Ghiberti’s version is quite different, suave and graceful rather than powerful and dramatic. Poses are controlled and choreographed; the harmonious pairing of son and father contrasts sharply with the wrenching struggle in Brunelleschi’s rendering. And Ghiberti’s Isaac is not a stretched, scrawny youth, but a fully idealized Classical figure exuding calm composure. Brunelleschi’s biographer, Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, claimed that the competition ended in a tie, and that when the committee decided to split the commission between the two young artists, Brunelleschi withdrew. It is possible, however, that the cloth merchants actually chose Ghiberti to make the doors. They might have preferred the elegance of his figural composition. Perhaps they liked the prominence of gracefully arranged swags of cloth, reminders of the source of their patronage and prosperity. But they also could have been swayed by the technical superiority of Ghiberti’s relief. Unlike Brunelleschi, Ghiberti cast background and figures mostly as a single piece, making his bronze stronger, lighter, and less expensive to produce. The finished doors—installed in the baptistery in 1424—were so successful that Ghiberti was commissioned to create another set (SEE FIG. 20–16), his most famous work, hailed by Michelangelo as the “Gates of Paradise.” Brunelleschi would refocus his career on buildings rather than bronzes, becoming one of the most important architects of the Italian Renaissance (SEE FIGS. 20–4, 20–6).

23

New cards

SACRIFICE OF ISAAC (BRUNELLESCHI)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Filippo Brunelleschi

* 1401–1402.

* Bronze with gilding,

* 21 × 171⁄2″ (53 × 44 cm) inside molding.

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

* **The Competition Relief**

* 1401–1402.

* Bronze with gilding,

* 21 × 171⁄2″ (53 × 44 cm) inside molding.

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

* **The Competition Relief**

24

New cards

SACRIFICE OF ISAAC (GHIBERTI)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Lorenzo Ghiberti

* 1401–1402.

* Bronze with gilding,

* 21 × 171⁄2″ (53 × 44 cm) inside molding.

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

* **The Competition Relief**

* 1401–1402.

* Bronze with gilding,

* 21 × 171⁄2″ (53 × 44 cm) inside molding.

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

* **The Competition Relief**

25

New cards

Filippo Brunelleschi, Architect

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

The defining civic project of the early years of the fifteenth century was the completion of Florence Cathedral with a magnificent dome over the high altar. The construction of the cathedral had begun in the late thirteenth century and had continued intermittently during the fourteenth. As early as 1367, builders had envisioned a very tall dome to span the huge interior space of the crossing, but they lacked the engineering know-how to construct it. When interest in completing the cathedral revived around 1407, the technical solution was proposed by the young sculptor-turned-architect Filippo Brunelleschi.

26

New cards

FLORENCE CATHEDRAL / DOME OF FLORENCE CATHEDRAL (SANTA MARIA DEL FIORE)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Filippo Brunelleschi

* 1420–1436; lantern completed 1471.

\

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377– 1446) achieved what many had considered impossible: He solved the problem of the dome of Florence Cathedral. Brunelleschi had originally trained as a goldsmith. To further his education, he traveled to Rome to study ancient Roman sculpture and architecture, and it was on his return to Florence that he tackled the dome. After the completion of a tall octagonal drum in 1412, Brunelleschi designed the dome itself in 1417, and it was built between 1420 and 1436 (FIGS. 20–4, 20–5). A revolutionary feat of engineering, the dome is a double shell of masonry 138 feet across. The octagonal outer shell is supported on 8 large and 16 lighter ribs. Instead of using a costly and even dangerous scaffold and centering, Brunelleschi devised a system in which temporary wooden supports were cantilevered out from the drum. He moved these supports up as building progressed. As the dome was built up course by course, each portion of the structure reinforced the next one. Vertical marble ribs interlocked with horizontal sandstone rings, connected and reinforced with iron rods and oak beams. The inner and outer shells were linked internally by a system of arches. When completed, this self-buttressed unit required no external support to keep it standing. An oculus (round opening) in the center of the dome was topped with a lantern designed in 1436. After Brunelleschi’s death, this crowning structure, made up of Roman architectural forms, was completed by another Florentine architect, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo (1396–1472). The final touch—a gilt-bronze ball by Andrea del Verrocchio—was added in 1468–1471 (but replaced in 1602 with a smaller one). Other commissions came quickly after the cathedral dome project established Brunelleschi’s fame. From about 1418 until his death in 1446, Brunelleschi was involved in a series of influential projects. Between 1419 and 1423, he built the elegant Capponi Chapel in the church of Santa Felicità (SEE FIG. 21–37). In 1419, he also designed a foundling hospital for the city.

* 1420–1436; lantern completed 1471.

\

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377– 1446) achieved what many had considered impossible: He solved the problem of the dome of Florence Cathedral. Brunelleschi had originally trained as a goldsmith. To further his education, he traveled to Rome to study ancient Roman sculpture and architecture, and it was on his return to Florence that he tackled the dome. After the completion of a tall octagonal drum in 1412, Brunelleschi designed the dome itself in 1417, and it was built between 1420 and 1436 (FIGS. 20–4, 20–5). A revolutionary feat of engineering, the dome is a double shell of masonry 138 feet across. The octagonal outer shell is supported on 8 large and 16 lighter ribs. Instead of using a costly and even dangerous scaffold and centering, Brunelleschi devised a system in which temporary wooden supports were cantilevered out from the drum. He moved these supports up as building progressed. As the dome was built up course by course, each portion of the structure reinforced the next one. Vertical marble ribs interlocked with horizontal sandstone rings, connected and reinforced with iron rods and oak beams. The inner and outer shells were linked internally by a system of arches. When completed, this self-buttressed unit required no external support to keep it standing. An oculus (round opening) in the center of the dome was topped with a lantern designed in 1436. After Brunelleschi’s death, this crowning structure, made up of Roman architectural forms, was completed by another Florentine architect, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo (1396–1472). The final touch—a gilt-bronze ball by Andrea del Verrocchio—was added in 1468–1471 (but replaced in 1602 with a smaller one). Other commissions came quickly after the cathedral dome project established Brunelleschi’s fame. From about 1418 until his death in 1446, Brunelleschi was involved in a series of influential projects. Between 1419 and 1423, he built the elegant Capponi Chapel in the church of Santa Felicità (SEE FIG. 21–37). In 1419, he also designed a foundling hospital for the city.

27

New cards

SCHEMATIC DRAWING OF FLORENCE CATHEDRAL

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* The separate, central-plan building in front of the façade is the baptistery.

* Adjacent to the façade is a tall tower designed by Giotto in 1334.

* Adjacent to the façade is a tall tower designed by Giotto in 1334.

28

New cards

THE FOUNDLING HOSPITAL / OSPEDALE DEGLI INNOCENTI (FOUNDLING HOSPITAL)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Filippo Brunelleschi

* FLORENCE

* Designed 1419; begun under Brunelleschi’s direct supervision 1421–1427; construction continued into the 1440s.

\

In 1419, the guild of silk manufacturers and goldsmiths (Arte della Seta) in Florence undertook a significant public service: It established a large public orphanage and commissioned Filippo Brunelleschi to build it near the church of the Santissima Annunziata (Most Holy Annunciation), which housed a miracle-working painting of the Annunciation, making it a popular pilgrimage site. Completed in 1444, the Foundling Hospital—OSPEDALE DEGLI INNOCENTI—was unprecedented in terms of scale and design (FIG. 20–6). Brunelleschi created a building that paid homage to traditional forms while introducing features that we associate with the Italian Renaissance style. Traditionally, a charitable foundation’s building had a portico open to the street to provide shelter, and Brunelleschi built an arcade of striking lightness and elegance, using smooth round columns and richly carved capitals—his own interpretation of the Classical Corinthian order. Although we might initially assume that the sources for this arcade lay in the Roman architecture of Classical antiquity, columns were not actually used in antiquity to support free-standing arcades, only to support straight architraves. In fact, it was local Romanesque architecture that was the source for Brunelleschi’s design. It is the details of capitals and moldings that bring an air of the antique to this influential building. The underlying mathematical basis for Brunelleschi’s design—traced to the same Pythagorean proportional systems that were believed to create musical harmony—creates a distinct sense of harmony in this graceful arcade. Each bay encloses a cube of space defined by the 10-braccia (20–foot) height of the columns and the diameter of the arches. Domical vaults, half as high again as the columns, cover the cubes. The bays at the end of the arcade are slightly larger than the rest, creating a subtle frame for the composition. Brunelleschi defined the perfect squares and semicircles of his building with pietra serena, a gray Tuscan sandstone, against plain white walls. His training as a goldsmith and sculptor served him well as he led his artisans to carve crisp, elegantly detailed capitals and moldings for the covered gallery.

* FLORENCE

* Designed 1419; begun under Brunelleschi’s direct supervision 1421–1427; construction continued into the 1440s.

\

In 1419, the guild of silk manufacturers and goldsmiths (Arte della Seta) in Florence undertook a significant public service: It established a large public orphanage and commissioned Filippo Brunelleschi to build it near the church of the Santissima Annunziata (Most Holy Annunciation), which housed a miracle-working painting of the Annunciation, making it a popular pilgrimage site. Completed in 1444, the Foundling Hospital—OSPEDALE DEGLI INNOCENTI—was unprecedented in terms of scale and design (FIG. 20–6). Brunelleschi created a building that paid homage to traditional forms while introducing features that we associate with the Italian Renaissance style. Traditionally, a charitable foundation’s building had a portico open to the street to provide shelter, and Brunelleschi built an arcade of striking lightness and elegance, using smooth round columns and richly carved capitals—his own interpretation of the Classical Corinthian order. Although we might initially assume that the sources for this arcade lay in the Roman architecture of Classical antiquity, columns were not actually used in antiquity to support free-standing arcades, only to support straight architraves. In fact, it was local Romanesque architecture that was the source for Brunelleschi’s design. It is the details of capitals and moldings that bring an air of the antique to this influential building. The underlying mathematical basis for Brunelleschi’s design—traced to the same Pythagorean proportional systems that were believed to create musical harmony—creates a distinct sense of harmony in this graceful arcade. Each bay encloses a cube of space defined by the 10-braccia (20–foot) height of the columns and the diameter of the arches. Domical vaults, half as high again as the columns, cover the cubes. The bays at the end of the arcade are slightly larger than the rest, creating a subtle frame for the composition. Brunelleschi defined the perfect squares and semicircles of his building with pietra serena, a gray Tuscan sandstone, against plain white walls. His training as a goldsmith and sculptor served him well as he led his artisans to carve crisp, elegantly detailed capitals and moldings for the covered gallery.

29

New cards

INFANT IN SWADDLING CLOTHES (ONE OF THE HOLY INNOCENTS MASSACRED BY HEROD) Ospedale degli Innocenti (Foundling Hospital)

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Andrea della Robbia,

* Florence.

* c. 1487.

* Glazed terra cotta.

\

A later addition to the building seems especially suitable: About 1487, Andrea della Robbia, who had inherited the family ceramics firm and its secret glazing formulas from his uncle Luca, created for the spandrels between the arches glazed terra-cotta medallions (FIG. 20–7) that signified the building’s function. Molds were used in the ceramic workshop to facilitate the production of the series of similar babies in swaddling clothes, one of which was placed at the center of each medallion. The terra-cotta forms were covered with a tin glaze to make the sculptures both weatherproof and decorative, and the baby-blue ceramic backgrounds—a signature color for the della Robbia family workshop—makes the babies seem to float as celestial apparitions. This is not altogether inappropriate. Although they clearly refer to the foundlings (innocenti) cared for in the hospital, they are also meant to evoke the innocent baby boys martyred by King Herod in his attempt to rid his realm of the potential rival the Magi had journeyed to venerate (Matthew 2:16). Andrea della Robbia’s ceramic babies—which remain among the most beloved images of the city of Florence— seem to lay claim to the human side of Renaissance humanism, reminding viewers that the city’s wealthiest guild cared for the most helpless members of society. Perhaps the Foundling Hospital spoke to fifteenth-century Florentines’ increased sense of social responsibility. Or perhaps, by so publicly demonstrating social concerns, the wealthy guild that sponsored the hospital solicited the support of the lower classes in the cut-throat power politics of the day.

* Florence.

* c. 1487.

* Glazed terra cotta.

\

A later addition to the building seems especially suitable: About 1487, Andrea della Robbia, who had inherited the family ceramics firm and its secret glazing formulas from his uncle Luca, created for the spandrels between the arches glazed terra-cotta medallions (FIG. 20–7) that signified the building’s function. Molds were used in the ceramic workshop to facilitate the production of the series of similar babies in swaddling clothes, one of which was placed at the center of each medallion. The terra-cotta forms were covered with a tin glaze to make the sculptures both weatherproof and decorative, and the baby-blue ceramic backgrounds—a signature color for the della Robbia family workshop—makes the babies seem to float as celestial apparitions. This is not altogether inappropriate. Although they clearly refer to the foundlings (innocenti) cared for in the hospital, they are also meant to evoke the innocent baby boys martyred by King Herod in his attempt to rid his realm of the potential rival the Magi had journeyed to venerate (Matthew 2:16). Andrea della Robbia’s ceramic babies—which remain among the most beloved images of the city of Florence— seem to lay claim to the human side of Renaissance humanism, reminding viewers that the city’s wealthiest guild cared for the most helpless members of society. Perhaps the Foundling Hospital spoke to fifteenth-century Florentines’ increased sense of social responsibility. Or perhaps, by so publicly demonstrating social concerns, the wealthy guild that sponsored the hospital solicited the support of the lower classes in the cut-throat power politics of the day.

30

New cards

SAN LORENZO / INTERIOR OF CHURCH OF SAN LORENZO, FLORENCE

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Filippo Brunelleschi (continued by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo)

* c. 1421–1428; nave (designed 1434?) 1442–1470.

\

For the Medicis’ parish church of San Lorenzo, Brunelleschi designed and built a centrally planned sacristy (a room where ritual attire and vessels are kept) from 1421 to 1428 and also conceived plans for a new church. The church has a basilican plan with a long nave flanked by side aisles that open into shallow lateral chapels (FIG. 20–8). A short transept and square crossing lead to a square sanctuary flanked by additional chapels opening off the transept. Brunelleschi based his mathematically regular plan on a square module—a basic unit of measure that could be multiplied or divided and applied to every element of the design, creating a series of clear, harmonious spaces. Architectural details, all in a Classical style, were carved in the dark gray pietra serena, that became synonymous with Brunelleschi’s interiors. Below the plain clerestory with its unobtrusive openings, the arches of the nave arcade are carried on tall, slender Corinthian columns made even taller by the insertion of an impost block between the column capital and the springing of the round arches—one of Brunelleschi’s favorite details. Flattened architectural moldings in pietra serena repeat the arcade in the outer walls of the side aisles, and each bay is covered by its own shallow domical vault. Brunelleschi’s rational approach, clear sense of order, and innovative incorporation of Classical motifs inspired later Renaissance architects, many of whom learned from his work firsthand by completing his unfinished projects.

* c. 1421–1428; nave (designed 1434?) 1442–1470.

\

For the Medicis’ parish church of San Lorenzo, Brunelleschi designed and built a centrally planned sacristy (a room where ritual attire and vessels are kept) from 1421 to 1428 and also conceived plans for a new church. The church has a basilican plan with a long nave flanked by side aisles that open into shallow lateral chapels (FIG. 20–8). A short transept and square crossing lead to a square sanctuary flanked by additional chapels opening off the transept. Brunelleschi based his mathematically regular plan on a square module—a basic unit of measure that could be multiplied or divided and applied to every element of the design, creating a series of clear, harmonious spaces. Architectural details, all in a Classical style, were carved in the dark gray pietra serena, that became synonymous with Brunelleschi’s interiors. Below the plain clerestory with its unobtrusive openings, the arches of the nave arcade are carried on tall, slender Corinthian columns made even taller by the insertion of an impost block between the column capital and the springing of the round arches—one of Brunelleschi’s favorite details. Flattened architectural moldings in pietra serena repeat the arcade in the outer walls of the side aisles, and each bay is covered by its own shallow domical vault. Brunelleschi’s rational approach, clear sense of order, and innovative incorporation of Classical motifs inspired later Renaissance architects, many of whom learned from his work firsthand by completing his unfinished projects.

31

New cards

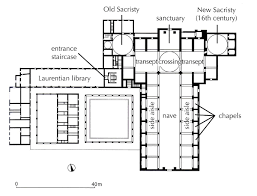

PLAN OF CHURCH OF SAN LORENZO, FLORENCE

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Filippo Brunelleschi (continued by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo)

* c. 1421–1428; nave (designed 1434?) 1442–1470

* c. 1421–1428; nave (designed 1434?) 1442–1470

32

New cards

THE MEDICI PALACE / FAÇADE, PALAZZO MEDICI-RICCARDI, FLORENCE

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Attributed to Michelozzo di Bartolomeo

* Begun 1446 (the view shown here includes a two-bay extension constructed during the 18th century)

\

* For the palace site, Cosimo de’ Medici the Elder chose the Via de’ Gori at the corner of the Via Larga, the widest city street at that time. Despite his practical reasons for constructing a large residence and the fact that he chose simplicity and austerity over grandeur in the exterior design, his detractors commented and gossiped. As one exaggerated, “\[Cosimo\] has begun a palace which throws even the Colosseum at Rome into the shade.”

\

Brunelleschi may have been involved in designing the nearby Medici Palace (now known as the PALAZZO MEDICI-RICCARDI) in 1446. According to Giorgio Vasari, the sixteenth-century artist and theorist who wrote the first modern history of art, Cosimo de’ Medici the Elder rejected Brunelleschi’s model for the palazzo as too grand (any large house was called a palazzo—“palace”). Many now attribute the design of the building to Michelozzo. The austere exterior (FIG. 20–9) was in keeping with the Florentine political climate and religious attitudes, both imbued with the Franciscan ideals of poverty and charity. Like many other European cities, Florence had sumptuary laws that forbade ostentatious displays of wealth—but they were often ignored. For example, private homes were supposed to be limited to a dozen rooms, but Cosimo acquired and demolished 20 small houses to provide the site for his new residence. His house was more than a dwelling place; it was his place of business, his company headquarters. The palazzo symbolized the family and established its place in the Florentine social hierarchy. Huge in scale—each story is more than 20 feet high— the building is marked by harmonious proportions and elegant, Classically inspired details. On one side, the ground floor originally opened through large, round arches onto the street, creating in effect a loggia that provided space for the family business. These arches were walled up in the sixteenth century and given windows designed by Michelangelo. The large, rusticated stone blocks—that is, blocks with their outer faces left rough—facing the lower story clearly set it off from the upper two levels. In fact, all three stories are distinguished by stone surfaces that vary from sculptural at the ground level to almost smooth dressed stone on the third floor. The builders followed the time-honored tradition of placing rooms around a central courtyard. Unlike the plan of the house of Jacques Coeur (SEE FIG. 19–24A), however, the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi courtyard is square in plan with rooms arranged symmetrically (FIG. 20–10). Round arches on slender columns form a continuous arcade under an enclosed second story. Disks bearing the Medici arms top each arch in a frieze decorated with swags in sgraffito work (decoration produced by scratching through a darker layer of plaster or glaze). Such classicizing elements, inspired by the study of Roman ruins, gave the great house an aura of dignity and stability that enhanced the status of its owners. The Medici Palace inaugurated a new fashion for monumentality and regularity in residential Florentine architecture.

* Begun 1446 (the view shown here includes a two-bay extension constructed during the 18th century)

\

* For the palace site, Cosimo de’ Medici the Elder chose the Via de’ Gori at the corner of the Via Larga, the widest city street at that time. Despite his practical reasons for constructing a large residence and the fact that he chose simplicity and austerity over grandeur in the exterior design, his detractors commented and gossiped. As one exaggerated, “\[Cosimo\] has begun a palace which throws even the Colosseum at Rome into the shade.”

\

Brunelleschi may have been involved in designing the nearby Medici Palace (now known as the PALAZZO MEDICI-RICCARDI) in 1446. According to Giorgio Vasari, the sixteenth-century artist and theorist who wrote the first modern history of art, Cosimo de’ Medici the Elder rejected Brunelleschi’s model for the palazzo as too grand (any large house was called a palazzo—“palace”). Many now attribute the design of the building to Michelozzo. The austere exterior (FIG. 20–9) was in keeping with the Florentine political climate and religious attitudes, both imbued with the Franciscan ideals of poverty and charity. Like many other European cities, Florence had sumptuary laws that forbade ostentatious displays of wealth—but they were often ignored. For example, private homes were supposed to be limited to a dozen rooms, but Cosimo acquired and demolished 20 small houses to provide the site for his new residence. His house was more than a dwelling place; it was his place of business, his company headquarters. The palazzo symbolized the family and established its place in the Florentine social hierarchy. Huge in scale—each story is more than 20 feet high— the building is marked by harmonious proportions and elegant, Classically inspired details. On one side, the ground floor originally opened through large, round arches onto the street, creating in effect a loggia that provided space for the family business. These arches were walled up in the sixteenth century and given windows designed by Michelangelo. The large, rusticated stone blocks—that is, blocks with their outer faces left rough—facing the lower story clearly set it off from the upper two levels. In fact, all three stories are distinguished by stone surfaces that vary from sculptural at the ground level to almost smooth dressed stone on the third floor. The builders followed the time-honored tradition of placing rooms around a central courtyard. Unlike the plan of the house of Jacques Coeur (SEE FIG. 19–24A), however, the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi courtyard is square in plan with rooms arranged symmetrically (FIG. 20–10). Round arches on slender columns form a continuous arcade under an enclosed second story. Disks bearing the Medici arms top each arch in a frieze decorated with swags in sgraffito work (decoration produced by scratching through a darker layer of plaster or glaze). Such classicizing elements, inspired by the study of Roman ruins, gave the great house an aura of dignity and stability that enhanced the status of its owners. The Medici Palace inaugurated a new fashion for monumentality and regularity in residential Florentine architecture.

33

New cards

COURTYARD WITH SGRAFFITO DECORATION, PALAZZO MEDICI-RICCARDI

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* FLORENCE

* Begun 1446.

* Begun 1446.

34

New cards

Sculpture

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

The new architectural language inspired by ancient Classical forms was accompanied by a similar impulse in sculpture. By 1400, Florence had enjoyed internal stability and economic prosperity for over two decades. However, until 1428, the city and its independence were challenged by two great anti-republican powers: the duchy of Milan and the kingdom of Naples. In an atmosphere of wealth and civic patriotism, Florentines turned to commissions that would express their self-esteem and magnify the importance of their city. A new attitude toward realism, space, and the Classical past set the stage for more than a century of creativity. Sculptors led the way.

35

New cards

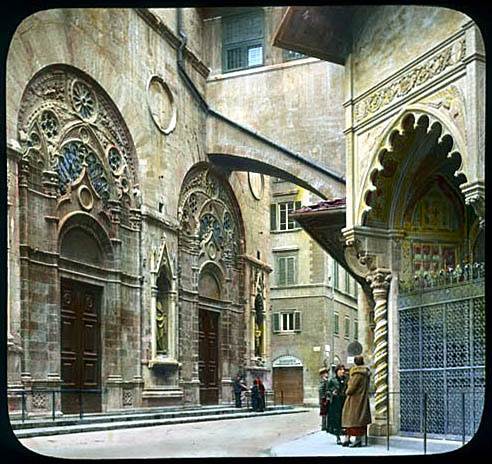

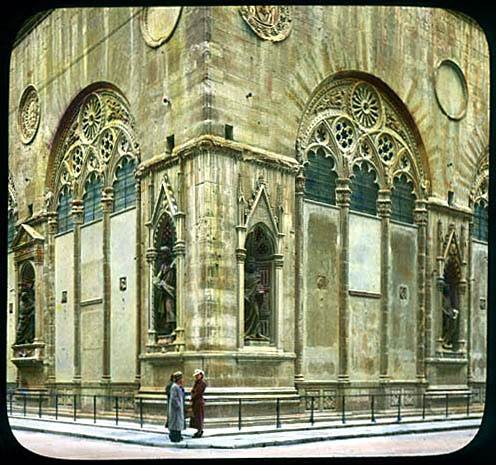

ORSANMICHELE / EXTERIOR VIEW OF ORSANMICHELE SHOWING SCULPTURE IN NICHES

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Florence.

* Begun 1337.

\

* At street level, Orsanmichele was constructed originally as an open loggia (similar to the Loggia dei Lanzi in FIG. 18–2); in 1380 the spaces under the arches were filled in. In this view of the southeast corner, appearing on the receding wall to the left is first (in the foreground on the corner pier) Donatello’s St. George, then, Nanni di Banco’s Four Crowned Martyrs. However, the sculptures seen in this photograph are modern replicas; the originals have been removed to museums for safekeeping.

\

In 1339, 14 of Florence’s most powerful guilds had been commissioned to fill the ground-floor niches that decorated the exterior of ORSANMICHELE—a newly completed loggia that served as a grain market— with sculpted images of their patron saints (FIG. 20–11). By 1400, only three had fulfilled this assignment. In the new climate of republicanism and civic pride, the government pressured the guilds to fill their niches. This directive resulted in a dazzling display of sculpture produced by the most impressive local practitioners, including Nanni di Banco, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Donatello, each of whom took responsibility for filling three niches.

* Begun 1337.

\

* At street level, Orsanmichele was constructed originally as an open loggia (similar to the Loggia dei Lanzi in FIG. 18–2); in 1380 the spaces under the arches were filled in. In this view of the southeast corner, appearing on the receding wall to the left is first (in the foreground on the corner pier) Donatello’s St. George, then, Nanni di Banco’s Four Crowned Martyrs. However, the sculptures seen in this photograph are modern replicas; the originals have been removed to museums for safekeeping.

\

In 1339, 14 of Florence’s most powerful guilds had been commissioned to fill the ground-floor niches that decorated the exterior of ORSANMICHELE—a newly completed loggia that served as a grain market— with sculpted images of their patron saints (FIG. 20–11). By 1400, only three had fulfilled this assignment. In the new climate of republicanism and civic pride, the government pressured the guilds to fill their niches. This directive resulted in a dazzling display of sculpture produced by the most impressive local practitioners, including Nanni di Banco, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Donatello, each of whom took responsibility for filling three niches.

36

New cards

DONATELLO

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

Donatello (Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, c. 1386/1387–1466) also received three commissions for the niches at Orsanmichele during the first quarter of the century. Like Nanni a member of the guild of stonecarvers and woodworkers, he worked in both media, as well as in bronze. During a long and productive career, he developed into one of the most influential and distinguished figures in the history of Italian sculpture, approaching each commission as if it were the opportunity for a new experiment.

37

New cards

THE FOUR CROWNED MARTYRS

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Nanni di Banco

* c. 1409–1417.

* Marble,

* height of figures 6′ (1.83 m).

* Photographed in situ before removal of the figures to the Museo di Orsanmichele, Florence

\

In about 1409, Nanni di Banco (c. 1385–1421), son of a sculptor in the Florence Cathedral workshop, was commissioned by the stonecarver and woodworkers’ guild (to which he himself belonged) to produce THE FOUR CROWNED MARTYRS (FIG. 20–12). According to tradition, these third- or fourth-century Christian martyrs were sculptors executed for refusing to make an image of a pagan Roman god for Emperor Diocletian. Although the architectural setting is Gothic in style, Nanni’s figures—with their solid bodies, heavy yet form-revealing togas, noble hair and beards, and portraitlike features— reveal his interest in ancient Roman sculpture, particularly portraiture (SEE FIG. 6–15). They testify to this sculptor’s role in the Florentine revival of interest in antiquity. The saints convey a new spatial relationship to the building and to the viewer. They stand in a semicircle, with feet and drapery protruding beyond the floor of the niche and into the viewer’s space. The saints appear to be four individuals interacting within their own world, but a world that opens to engage with passing pedestrians (SEE FIG. 20–11). The relief panel below the niche shows the four sculptors at work, embodied with a similar solid vigor. Nanni deeply undercut both figures and objects to cast shadows that enhance the illusion of three-dimensionality.

* c. 1409–1417.

* Marble,

* height of figures 6′ (1.83 m).

* Photographed in situ before removal of the figures to the Museo di Orsanmichele, Florence

\

In about 1409, Nanni di Banco (c. 1385–1421), son of a sculptor in the Florence Cathedral workshop, was commissioned by the stonecarver and woodworkers’ guild (to which he himself belonged) to produce THE FOUR CROWNED MARTYRS (FIG. 20–12). According to tradition, these third- or fourth-century Christian martyrs were sculptors executed for refusing to make an image of a pagan Roman god for Emperor Diocletian. Although the architectural setting is Gothic in style, Nanni’s figures—with their solid bodies, heavy yet form-revealing togas, noble hair and beards, and portraitlike features— reveal his interest in ancient Roman sculpture, particularly portraiture (SEE FIG. 6–15). They testify to this sculptor’s role in the Florentine revival of interest in antiquity. The saints convey a new spatial relationship to the building and to the viewer. They stand in a semicircle, with feet and drapery protruding beyond the floor of the niche and into the viewer’s space. The saints appear to be four individuals interacting within their own world, but a world that opens to engage with passing pedestrians (SEE FIG. 20–11). The relief panel below the niche shows the four sculptors at work, embodied with a similar solid vigor. Nanni deeply undercut both figures and objects to cast shadows that enhance the illusion of three-dimensionality.

38

New cards

ST. GEORGE

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Donatello

* Formerly in Orsanmichele, Florence.

* 1417–1420.

* Marble,

* height 6′5″ (1.95 m).

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

\

One of Florence’s lesser guilds—the armorers and sword-makers—called on Donatello to carve a majestic and self-assured ST. GEORGE for their niche (FIG. 20–13). As originally conceived, the saint would have been a standing advertisement for their trade, carrying a metal sword in his right hand and probably wearing a metal helmet and sporting a scabbard, all now lost. The figure has remarkable presence, even without his accessories. St. George stands in solid defiance, legs braced to support his armor-heavy torso. He seems to stare out into our world, perhaps sizing up his most famous adversary—a dragon that was holding a princess captive—lurking in the space behind us. With his wrinkled brow and determined expression, he is alert and focused, if perhaps also slightly worried. This complex psychological characterization of the warrior-saint particularly impressed Donatello’s contemporaries, not least among them his potential patrons. For the base of the niche, Donatello carved a remarkable shallow relief showing St. George slaying the dragon and saving the princess, a well-known part of his story. The contours of the foreground figures are slightly undercut to emphasize their mass, while the landscape and architecture are in progressively lower relief until they are barely incised rather than carved, an ingenious emulation of the painter’s technique of atmospheric perspective. This is also a pioneering example of linear perspective (see “Renaissance Perspective” on page 623), in which the orthogonals converge on the figure of the saint himself. Donatello used this timely representational system not only to simulate spatial recession, but also to provide narrative focus. Donatello’s long career as a sculptor in a broad variety of media established him as one of the most successful and admired sculptors of the Italian Renaissance. He excelled in part because of his attentive exploration of human emotions and expression, as well as his ability to solve the technical problems posed by various media—from lost-wax casting in bronze and carved marble to polychromed wood.

* Formerly in Orsanmichele, Florence.

* 1417–1420.

* Marble,

* height 6′5″ (1.95 m).

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

\

One of Florence’s lesser guilds—the armorers and sword-makers—called on Donatello to carve a majestic and self-assured ST. GEORGE for their niche (FIG. 20–13). As originally conceived, the saint would have been a standing advertisement for their trade, carrying a metal sword in his right hand and probably wearing a metal helmet and sporting a scabbard, all now lost. The figure has remarkable presence, even without his accessories. St. George stands in solid defiance, legs braced to support his armor-heavy torso. He seems to stare out into our world, perhaps sizing up his most famous adversary—a dragon that was holding a princess captive—lurking in the space behind us. With his wrinkled brow and determined expression, he is alert and focused, if perhaps also slightly worried. This complex psychological characterization of the warrior-saint particularly impressed Donatello’s contemporaries, not least among them his potential patrons. For the base of the niche, Donatello carved a remarkable shallow relief showing St. George slaying the dragon and saving the princess, a well-known part of his story. The contours of the foreground figures are slightly undercut to emphasize their mass, while the landscape and architecture are in progressively lower relief until they are barely incised rather than carved, an ingenious emulation of the painter’s technique of atmospheric perspective. This is also a pioneering example of linear perspective (see “Renaissance Perspective” on page 623), in which the orthogonals converge on the figure of the saint himself. Donatello used this timely representational system not only to simulate spatial recession, but also to provide narrative focus. Donatello’s long career as a sculptor in a broad variety of media established him as one of the most successful and admired sculptors of the Italian Renaissance. He excelled in part because of his attentive exploration of human emotions and expression, as well as his ability to solve the technical problems posed by various media—from lost-wax casting in bronze and carved marble to polychromed wood.

39

New cards

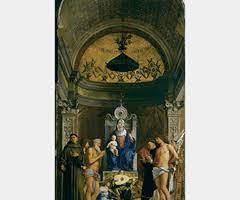

Donatello DAVID

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

%%**(FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY)**%%

==**(EARLY RENNAISSANCE IN FLORENCE)**==

* Donatello

* c. 1446–1460 (?).

* Bronze,

* height 5′21⁄4″ (1.58 m).

* Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

\

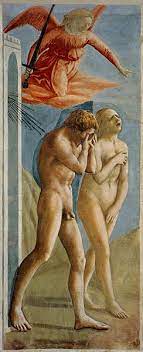

* This sculpture is first recorded as being in the courtyard of the Medici Palace in 1469, where it stood on a base inscribed with these lines: The victor is whoever defends the fatherland. All-powerful God crushes the angry enemy. Behold, a boy overcomes the great tyrant. Conquer, O citizens!

\