Aggregate Supply, Macroeconomic Equilibrium & Assumptions

1/25

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

26 Terms

Aggregate supply (AS)

the total amount of output of goods and services that firms within an economy are willing and able to supply at a given time and at an overall price level.

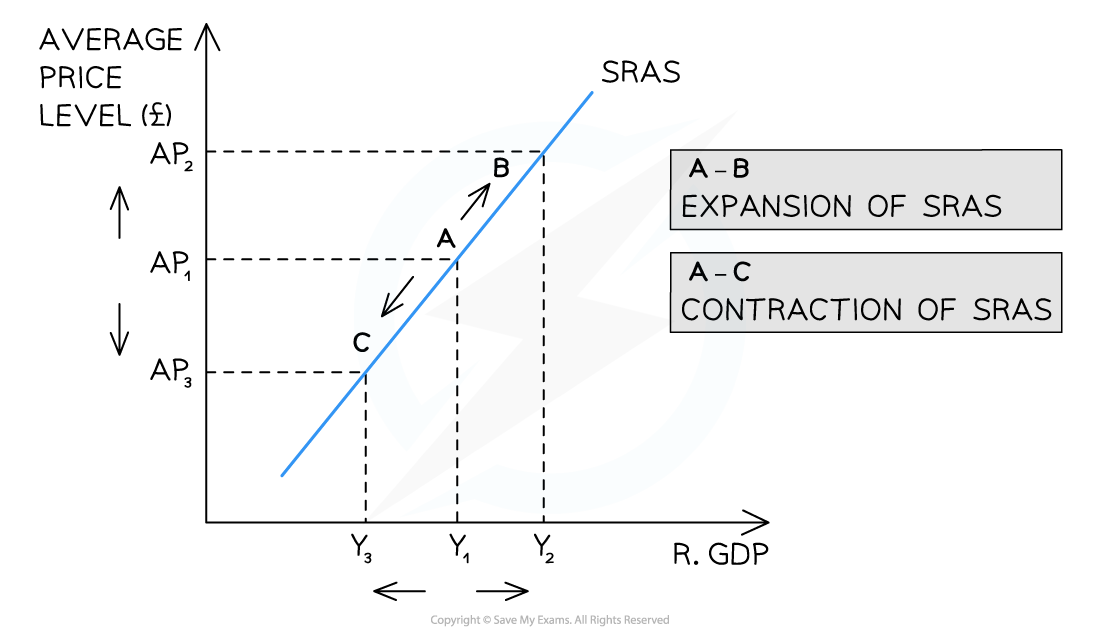

Short run aggregate supply curve (SRAS)

shows the total planned national output at difference price levels, ceteris paribus.

short run in macroeconomics

the period of lime when all resource prices (wages and prices of all other factors of production) are constant

long run in macroeconomics

the period of time when all resource prices (wages and prices of all other factors of production) change to match changes in the price level (resource prices and the price level increase or decrease together).

Why is the SRAS upwards sloping?

because higher prices attract more firms in the economy to raise their output level. In the short run, it is assumed that capital if fixed, so firms can only alter variables of production, such as labour in order to increase output. The SRAS is therefore relatively price elastic in the short run as firms can increase output by getting employees to work overtime.

Determinants of SRAS

Costs of factors of production: Costs of production are the expenses that firms face in producing goods and services.

Labour costs

Raw material costs

Exchange rate

Interest rates

Bureaucracy and administration

Indirect Taxes: government levies or charges on expenditure, rather than on income. They add onto the costs of production for a supplier, even if the supplier can pass on some of the tax to the consumer in the form of higher prices for goods and services. They reduce the profitability of firms, so they tend to reduce aggregate supply.

Shifts of the SRAS curve

changes in non-price factors that affect aggregate supply will shift SRAS curve to the left or right.

shifts are caused by changes in commodity prices, nominal wages, productivity, and future expectations about inflation.

The two alternative view of aggregate supply

Monetarist/new classical view of the LRAS

Keynesian view of the AS

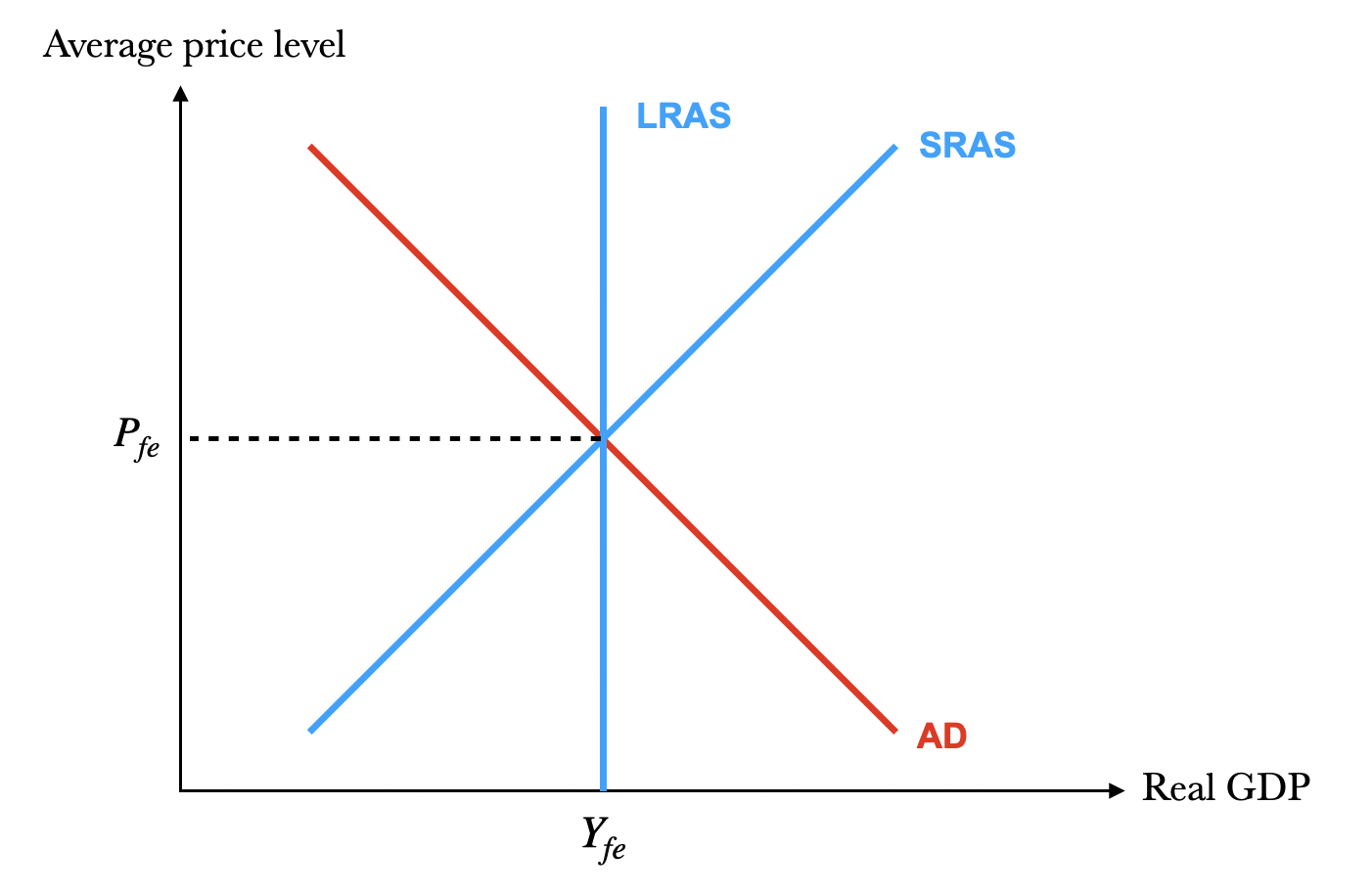

Long run aggregate supply curve (LRAS)

a curve that shows the relationship between price level and real GDP that would be supplied if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible

LRAS: Monetarist model

the maximum level of real GDP at the full employment level of national output. It shows that aggregate supply is independent of the price level, that is, LRAS is perfectly price inelastic.

the economy cannot produce beyond the productive capacity of a particular GDP. Therefore, the long-run equilibrium exists as this maximum productive capacity.

Any attempt to increase aggregate demand beyond the maximum productive capacity will only be inflationary, with the general price level increasing.

The price level does not affect the LRAS. It is dependent on non-price variables like the state of technology, or the quantity and quality of F.O.P

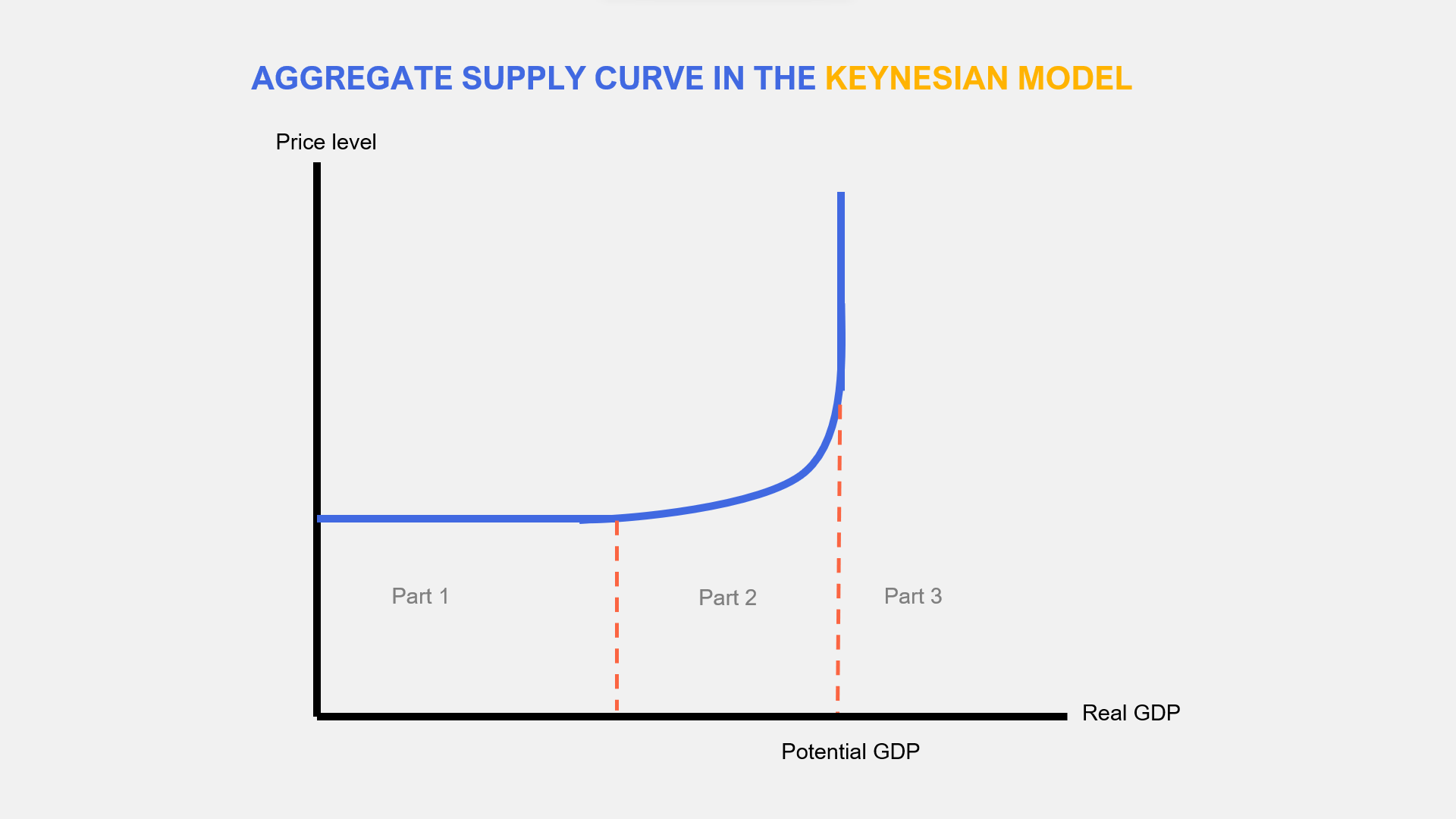

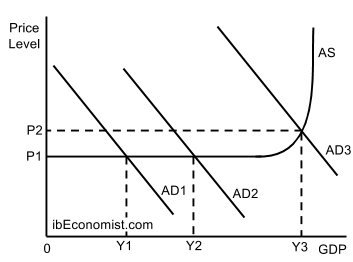

LRAS: Keynesian model

Keynesians believe that the AS curve has three distinct sections

They believe that the economy can be below the full employment level, even in the long run.

Section 1: aggregate supply is perfectly price elastic (horizontal) as there is plenty of spare capacity (unemployed resources) in the economy. Any increase in aggregate demand has no direct impact on the general price level.

Section 2: aggregate supply is relatively price elastic (upwards sloping) as there is pressure on scarce resources as the economy grows. As with the law of supply, an increase in the general price level will incentivize firms to supply more output.

Section 3: aggregate supply is perfectly price inelastic (vertical) as there is no longer any spare capacity in the economy, that is, all factor resources are fully employed. Any increase in aggregate demand beyond the full employment level of output is simply inflationary.

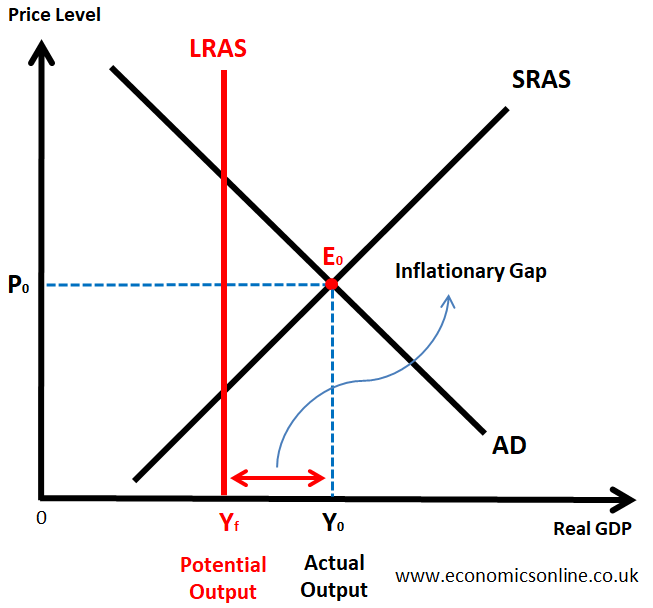

inflationary gap

exists in actual national output exceeds the full employment level of output. This means that the economy operates beyond the full employment level of national output due to the excess levels of aggregate demand for the consumption of goods and services.

It is called an inflationary gap, because the actual GDP exceeds potential GDP so the higher levels of expenditure throughout the economy increases the general price level over time.

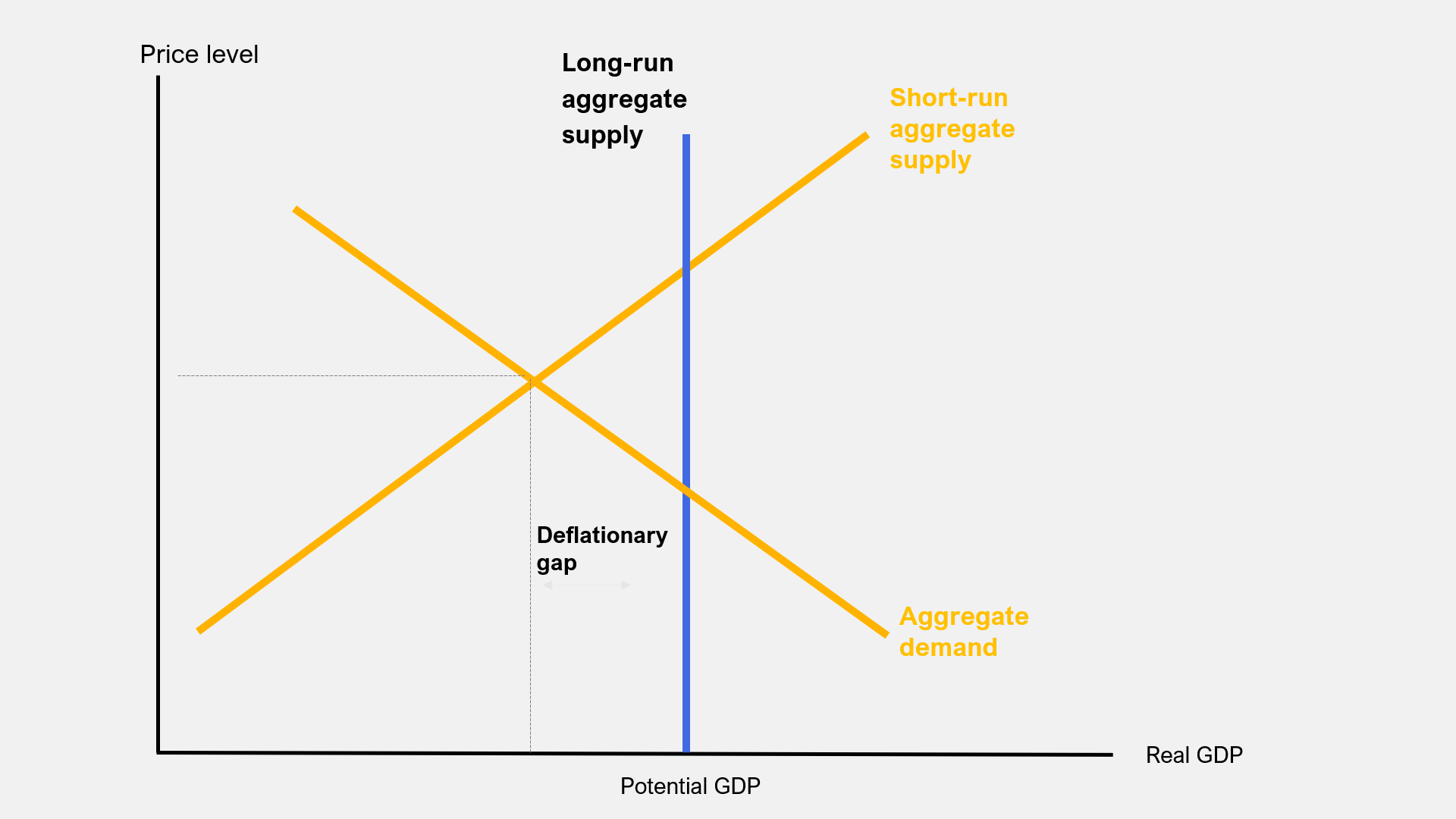

deflationary gap (recessionary gap/negative output gap)

exists when the real national output equilibrium is below the full employment level of output. Hence, actual economic growth is below the average trend rate of growth.

caused by lower levels of aggregate demand (AD) due to any combination of a fall in:

consumer spending caused by lower household or higher interest rates

investment spending due to lower business confidence or a financial crisis

net export earnings due to a global recession

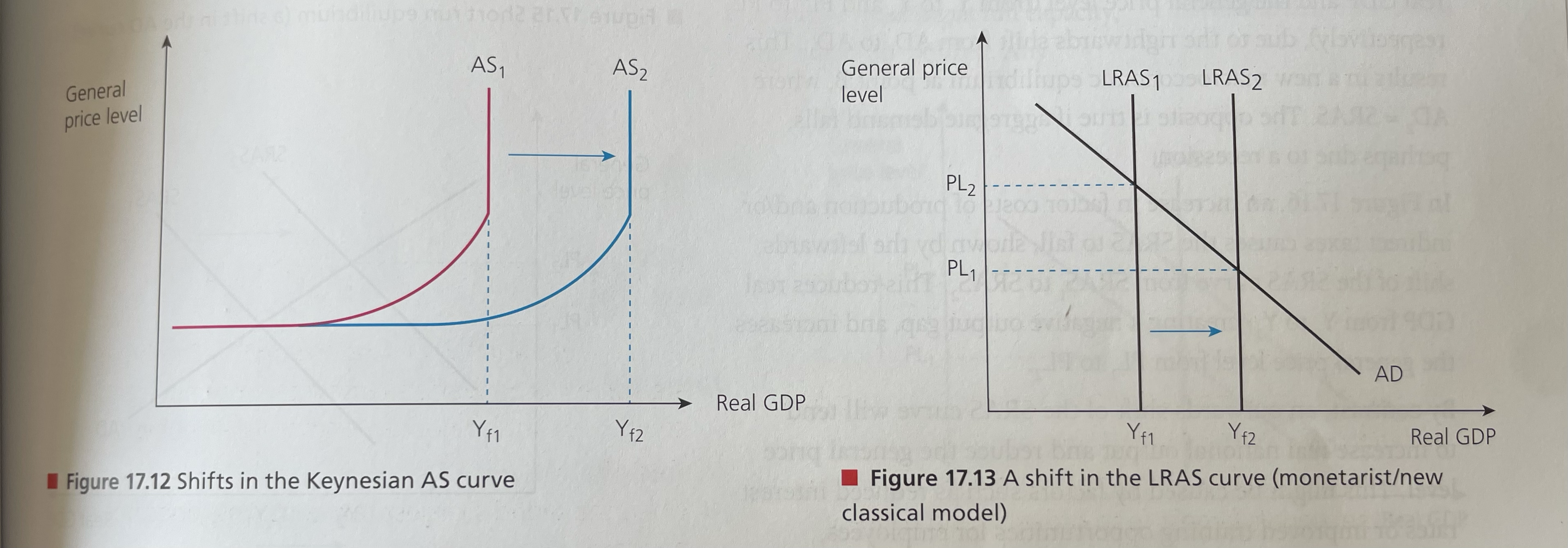

Shifts of the LRAS

changes in the economy’s quality or quantity of factors of production

Improvements in technology

Increases in efficiency (making best use of scarce resources, preventing wastage)

Changes in institutions (such as its legal and financial systems)

Shifts of the LRAS: Keynesian vs Monetarist model

A favourable change in the productive capacity of an economy can shif the AS curve outwards to the right due to the economy’s increased potential output.

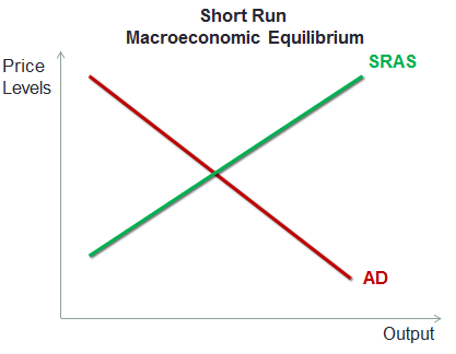

Short run macroeconomic equilibrium

occurs when the SRAS is equal to aggregate demand. (AD = AS)

therefore, any change in AD and/or SRAS will change the macroeconomic equilibrium position

Equilibrium in the monetarist/new classical model

long-run equilibrium occurs at the full employment level of output.

Automatic adjustments through the forces of AD and AS restore the economy to full employment equilibrium in the long run.

They assume wages and prices are flexible enough to maintain full employment in the long run.

They assume that the LRAS curve is vertical at the full employment level of output, where when those who are willing and able to work have a job, therefore the economy is working at full capacity. Any attempts to increase AD beyond the full employment level will be inflationary, only increasing the price level.

Equilibrium in the Keynesian model

Keynesians do not believe that the economy can always maintain equilibrium at the full employment level of output, but that there can be a persistence of recessionary gaps, that is, the macroeconomic equilibrium level of output might not equal the full employment level of output in the long-term.

The full employment level of output

exists at the point where unemployment is at it’s natural rate, so that everyone who is willing and able to work is in employment.

Assumptions and implications of the Keynesian model

wage inflexibility, which can cause persistent recessionary gaps and prevent the economy from reaching macroeconomic equilibrium (wages are ‘sticky’ downwards)

The implication of this is that there needs to be government intervention to restore long-run macroeconomic equilibrium through the use of loose monetary policy and or/expansionary fiscal policy

Assumptions and implications of the Monetarist model

assumes natural unemployment persists in the long run

Long run equilibrium occurs at full employment of real national output.

Any fall in real national output below the macroeconomic equilibrium is assumed to be only temporary, as the economic would return to equilibrium at its own accord

if the economy is below full employment, wages should fall and labour flexibility will clear the economy of any unemployment.

prefer supply-side policies to shift the LRAS curve outwards to achieve economic growth in the long run

Does full employment mean there is no employment in the economy?

no, as there will always be some unemployment that naturally exists, because:

a certain number of people are in-between jobs (frictional unemployment)

redundancies are caused by cyclical factors in the year (seasonal unemployment)

there is skills mismatch in certain industries (structural unemployment)

natural rate of unemployment

the level of unemployment at the full employment equilibrium of national output, comprising seasonal, frictional and structural unemployment.

Why did Kaynes argue that wages are ‘sticky downwards’ (inflexible?)

workers get used to a certain wage rate or income so are inflexible in accepting nominal pay cuts, especially when backed up by their trade union and industrial action to upload employee rights

existing employment contracts can prevent wages and salaries from falling below the agreed (contracted) level

some firms may prefer to cut employment rather than wages because pay cuts can reduce worker morale and labour productivity

it is not legally possible to cut wages below the national minimum wage, even during a major economic downturn.

Did the Keynesians believe that macroeconomy is able to self-correct

they did not, especially from deep recessions. Without government intervention, the economy can remain stuck in a deflationary gap because of mass unemployment in the economy. The decline in aggregate demand is often due to interconnected reasons beyond the country of households and firms in the private sector.

What did Kaynes even mean by ‘sticky downwards?’

he used it to describe a situation in which a variable (such as wages) is resistant to change, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the market forces of demand and supply in the labour market.

Wages being sticky downwards means that wages can move up with ease, which labour unions are assumed to resist any attempt to have the wages of their members being reduced, even if this is in the best interest of the workforce in the long run. The result is inflationary without any corresponding increase in output, so Keynesians assume this can leave the economy in a prolonged recessionary gap.