Lecture 5: Personality and Psychopathology

1/20

Earn XP

Description and Tags

MBB2

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

21 Terms

Personality & Clinical Psychology

Both focus on individual differences

Both see critical role for assessment

Mental health issues occur in context of personality.

Some maladaptive forms of personality are thought of as disorder

Personality and Mental Health Issues

Three ways personality relates to mental health issues and disorder:

Vulnerability

Personality disorder

Other personality-related disorder

Vulnerability

People differ in susceptibility to mental health issues and disorders

Genes

Environmental stress

Personality

Rarely does one factor work alone

Genetic effects operate via personality

Genetic effects require environmental contribution

Environmental effects require genetic vulnerability

Diathesis-stress models

Most mental disorders involve the combined action of a personality vulnerability (‘diathesis’) and environmental stress.

From this ‘Diathesis-Stress’ perspective:

No disorder without diathesis

No expression of diathesis without stress

Both diathesis & stress vary by degrees

Level of stress required to trigger disorder depends on degree of diathesis

Diathesis-stress models

Stress may come in different forms

Traumatic experiences

Major life changes (including positive)

Accumulation of ‘hassles’

Some diatheses may require specific types of stressor

e.g., relationship- or achievement-related

Specific diatheses: depression

Dependency (interpersonal sensitivity)

Susceptibility to interpersonal stressors

Autonomy (personal achievement)

Susceptibility to achievement stressors Self-criticism

Pessimistic attributional style

Internal = low self-esteem

Stable = hopelessness

Global = helplessness

Specific diatheses: schizophrenia

Schizotypy

Social anhedonia

Physical anhedonia

Perceptual aberration

Magical thinking

This diathesis may be typological

Non-schizotypes may be at zero risk of schizophrenia (a subject of ongoing debate in the literature).

Schizotypy survey example items

Social anhedonia

“When someone else is depressed it brings me down also” (reverse scored)

Physical anhedonia

“One food tastes as good as another to me”

Perceptual aberration

“I have felt as though my head or limbs were somehow not my own”

Magical thinking

“If reincarnation were true, it would explain some unusual experiences I have had”

Additional example diatheses

Anorexia nervosa

Perfectionism

Bipolar disorder

Hypomanic temperament

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Thought-action fusion

Panic disorder

Anxiety sensitivity

Illustrative items

Perfectionism

“If I do not set the highest standards for myself I am likely to end up a second-rate person”

Hypomanic temperament

“I am frequently so hyper that my friends kiddingly ask me what drug I’m taking”

Thought-action fusion

“Having a bad thought is almost as sinful to me as a bad action”

Anxiety sensitivity

“It scares me when I feel faint”

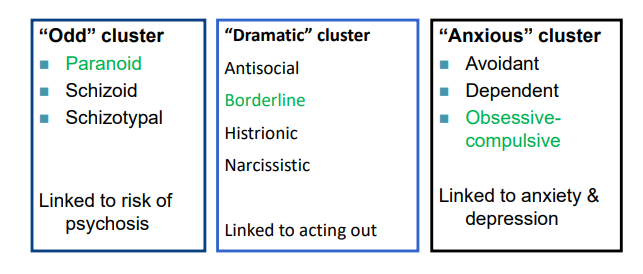

Personality disorders

Some personality attributes can be extreme, inflexible & maladaptive

These can be diagnosed as ‘personality disorders’

10 disorders currently recognized, e.g. …

Cluster A Example: Paranoid Personality Disorder

A pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others such that their motives are interpreted as malevolent, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by four (or more) of the following:

Suspects, without sufficient basis, that others are exploiting, harming, or deceiving him or her.

Is preoccupied with unjustified doubts about the loyalty or trustworthiness of friends or associates.

Is reluctant to confide in others because of unwarranted fear that the information will be used maliciously against him or her.

Reads hidden demeaning or threatening meanings into benign remarks or events.

Persistently bears grudges (i.e., is unforgiving of insults, injuries, or slights).

Perceives attacks on his or her character or reputation that are not apparent to others and is quick to react angrily or to counterattack.

Has recurrent suspicions, without justification, regarding fidelity of spouse or sexual partner

Cluster B Example: Narcissistic Personality Disorder

A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

Has a grandiose sense of self-importance (e.g., exaggerates achievements and talents, expects to be recognized as superior without commensurate achievements).

Is preoccupied with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love.

Believes that he or she is “special” and unique and can only be understood by, or should associate with, other special or high-status people (or institutions).

Requires excessive admiration.

Has a sense of entitlement (i.e., unreasonable expectations of especially favorable treatment or automatic compliance with his or her expectations).

Is interpersonally exploitative (i.e., takes advantage of others to achieve his or her own ends).

Lacks empathy: is unwilling to recognize or identify with the feelings and needs of others.

Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of him or her.

Shows arrogant, haughty behaviors or attitudes

Cluster C Example: Avoidant Personality Disorder

A pervasive pattern of social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy, and hypersensitivity to negative evaluation, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by four (or more) of the following:

Avoids occupational activities that involve significant interpersonal contact because of fears of criticism, disapproval, or rejection.

Is unwilling to get involved with people unless certain of being liked.

Shows restraint within intimate relationships because of the fear of being shamed or ridiculed.

Is preoccupied with being criticized or rejected in social situations.

Is inhibited in new interpersonal situations because of feelings of inadequacy.

Views self as socially inept, personally unappealing, or inferior to others.

Is unusually reluctant to take personal risks or to engage in any new activities because they may prove embarrassing

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Controversial diagnosis (Previously Multiple Personality Disorder, now ‘Dissociative Identity Disorder’: DID)

≥ 2 distinct personalities that switch

1 host personality

1 or more ‘alters’

Alters may differ in many ways

Dissociative Identity Disorder: DSM-5-TR

Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states, which may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession. The disruption in identity involves marked discontinuity in sense of self and sense of agency, accompanied by related alterations in affect, behavior, consciousness, memory, perception, cognition, and/or sensory-motor functioning. These signs and symptoms may be observed by others or reported by the individual.

Recurrent gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and/or traumatic events that are inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.

The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

The disturbance is not a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural or religious practice.

Note: In children, the symptoms are not better explained by imaginary playmates or other fantasy play.

The symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts or chaotic behavior during alcohol intoxication) or another medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures).

Dissociative Experiences Scale (sample items)

Amnesia

Some people have the experience of finding themselves in a place and having no idea how they got there.

Some people have the experience of finding new things among their belongings that they do not remember buying.

Depersonalization/derealization

Some people sometimes have the experience of feeling as though they are standing next to themselves or watching themselves do something as if they were looking at another person.

Some people sometimes have the experience of feeling that other people, objects, and the world around them are not real.

Absorption

Some people find that they sometimes sit staring off into space, thinking of nothing, and are not aware of the passage of time.

Some people sometimes find that they become so involved in a fantasy or daydream that it feels as though it were really happening to them

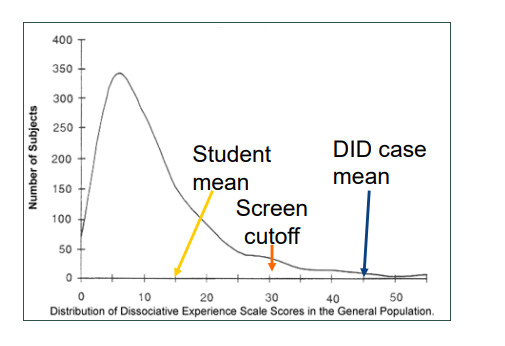

Distribution of DES scores

-

Dominant theory: (“traumatic”)

People with DID usually report suffering extreme trauma

They also tend to score high on ‘suggestibility’ (to hypnosis)

‘Dissociation’ as auto-hypnotic defence in which consciousness is ‘split’ during traumatic stress •

Dissociation = ‘internal avoidance’ or compartmentalization.

Patients become rehearsed and skilled in this defence & construct alter personalities to deal with complexities and threats of life experience

Another theory (“sociocognitive”)

The disorder may not be a naturally occurring splitting or fragmentation of the personality.

It may instead be caused by therapists and culture.

Therapists (poorly skilled) inadvertently may use leading questions in suggestible, unstable people may create apparently distinct personalities: iatrogenic.

Culture sanctions this manner of expression of psychological distress through creative mass media and news.

Treatment implications involve ignoring post-traumatic symptomatology.

A Controversial Diagnosis: DID Myths

Myth 1 – DID is a fad

Historical and contemporary evidence shows DID has been documented for centuries and formally recognised in the DSM since 1980. Research output and diagnostic reliability remain strong, with DID identifiable across multiple cultures and settings.

Myth 2 – DID is mainly diagnosed in North America by a few overdiagnosing experts

Epidemiological studies and treatment outcomes demonstrate DID is found worldwide, diagnosed by clinicians of varying expertise. Far from being overdiagnosed, DID is often missed — patients typically spend years in the mental health system before correct diagnosis.

Myth 3 – DID is rare

Prevalence studies using rigorous methods find DID in about 1–1.5% of the general population and higher rates in clinical and trauma-exposed samples. Cross-cultural research, including in countries where DID is not well known, further disproves rarity.

Myth 4 – DID is iatrogenic, not trauma-based

Large-scale meta-analyses support the trauma model, showing strong correlations between childhood abuse and dissociation. Evidence from cultures unfamiliar with DID and from historical records of patients’ early dissociation undermines the iatrogenic/fantasy model.

Myth 5 – DID is the same as Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

While symptoms overlap and comorbidity is common, structured interviews, clinical features, and neurobiological studies distinguish the two. DID is marked by amnesia and identity alteration not seen in BPD; treatment approaches differ substantially.

Myth 6 – DID treatment is harmful

Treatment following expert consensus guidelines — typically a three-phase trauma-focused psychotherapy — leads to improvements in symptoms, functioning, and reduced hospitalisation. No peer-reviewed evidence supports claims of harm; instead, untreated DID remains chronic.