Developmental Psychology - Week 7

1/33

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Executive Functions and Theory of Mind

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

34 Terms

Executive Functions

A series of processes that are needed for just about every aspect of life. Executive function allows us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully.

Examples of executive functions

cognitive flexibility, working memory, inhibition, attention and planning.

Cognitive flexibility

The ability to switch between thinking about two different concepts/multiple concepts simultaneously

Working Memory

Working memory is a type of short-term memory that stores information temporarily during the completion of cognitive tasks, such as comprehension, problem solving, reasoning, and learning.

Inhibition

It is the ability to control your actions, feelings, and thoughts. As children grow up, they are more able to control these.

Attention

refers to the ability to focus on certain things while ignoring distractions, as children grow they become more able to focus and shift their attention to other things.

Planning

The ability to think ahead, set goals, and organize steps to achieve them. It's about figuring out what needs to be done and how to do it efficiently. As children grow, their planning skills improve, helping them make better decisions, solve problems, and manage tasks.

Attention in infants

They gradually become more efficient at managing their attention: Newborns require 3-4 minutes to habituate and recover to novel stimuli. 4-5 month infants need as little as 5 to 10 seconds to process complex visual stimulus (Colombo et al., 2011).

Sustained attention increases: Their attraction to novelty stimulus reduces. They can sustain attention to reach their goals. For example, stacking blocks.

Memory in infants

Operant conditioning and habituation techniques

Recognition vs recalling

By 2-6 months: they remember how to activate a mobile (by kicking) for 1-2 days after training. Memory capacity increases as they grow, retaining information.

Categorisation in infants

In the first few months, infants can categorize stimuli based on shapes, size, and other physical properties (Wasserman & Rovee-Collier,2011)

By 6 months, they can categorize based on two correlated features such as shape and colour of the alphabet (Bhatt et al., 2014) and an array of categories including food, furniture, animals, etc. Perceptual (attention to features) and knowledge (concepts) expand.

They can also categorize the emotional and social world: by distinguishing people based on their voices, gender and emotional expression.

How do you measure executive functions in early childhood?

Executive functions develop further: Prefrontal cortex becomes more effective, Neural networks become more integrated.

Inhibition and flexible shifting

Preschoolers steadily gain their ability to inhibit impulses and keeping their mind on a goal.

Day-night task: 3 to 4-year-olds make many errors. 6 to 7 years old, find the task easier as they can resist the pull of attention to competing information (Diamon, 2004; Montgomery & Koeltzow, 2010)

Flexible shifting

This is shifting focus of attention depending on task demands

Children are asked to sort pictures in the face of conflicting information: Categorise based on colour, then switch the rule to categorise based on shapes irrespective of colour. It was found that children above the age of 4 successfully switch rules (Zelazo, 2006).

Flexible shifting improves in middle childhood. It is associated with inhibition as children need to inhibit the old rule in order to attend to the new rule (Kirkham, Cruess & Diamond 2003, Zelazo et al., 2013)

Planning

Thinking about a sequence before acting on them

Miniature zoo task, Scenario: Molly can only walk through the path once, and she wants to take a picture of the kangaroo. Question to the child: “What locker can you leave the camera in so that Molly can take a photo of the kangaroo?”

By the age of 5, children can effectively plan. They can postpone action in favour of mapping out a sequence of future moves, evaluating the consequences of each and adjusting them to their plan to fit the task requirements.

Working memory

Greater working memory enables them to hold and manipulate information (for instance, changing rules, inhibiting competing information), thus improving their performance and completing complex tasks.

Executive functions in middle childhood

It goes through marked improvement: Myelination of neural fibers increases, and the interconnectivity between brain areas strengthens. The prefrontal cortex also becomes more effective, and neural networks become more integrated.

Children are able to handle increasingly difficult tasks that require the integration of working memory, inhibition, strategic thinking, etc.

Inhibition and flexible shifting

Rule-use tasks: Performance improves between 6 and 10 years old and continues throughout adolescence (Gomez-Perrez and Otrosky-Solis, 2006; Tabibi and Pfeffer, 2007; Vakil et al., 2009)

Gain steadily in the complexity of rules they can keep in mind, as well as speed and accuracy in shifting between rules.

Attention also becomes more controlled.

Theory of mind

Having an understanding of other people as people who have desires, beliefs, and their own interpretations of the world (Smith et al., 2003)

The understanding that your values and goals may be different from others.

Why is theory of mind important?

Forms the foundation of social cognition - understanding that values and goals can be different from your own.

Daily use with adults and children to interpret body language, facial expressions, tone of voice, and making assumptions about others’ thoughts and feelings. For instance, understanding sarcasm, humor, and empathy relies on being able to read and interpret mental states that aren’t explicitly communicated.

ToM begins to develop as early as 18 months, in which the child has already started to engage in social referencing - for instance, looking to their caregiver’s reaction to gauge how they should feel in a new or uncertain situation.

At around 4, children are able to understand that people are able to hold false beliefs/ misunderstandings, which is a significant development in ToM.

Perception of others

Understanding that others’ behavior based on their beliefs about the world is vital if we are trying to make sense of what people say and how they behave.

We want to understand beliefs as it will help us to predict behaviour, explain behaviour, and manipulate it.

Measuring ToM - false belief tasks + results

Wimmer and Perner (1983) reported a study which tested the theory of mind abilities of preschool children with Maxie and the chocolate bar.

The test centered on the ability to understand when someone else had a false belief about something.

This was argued to be the most effective test of ‘mind reading’ ability.

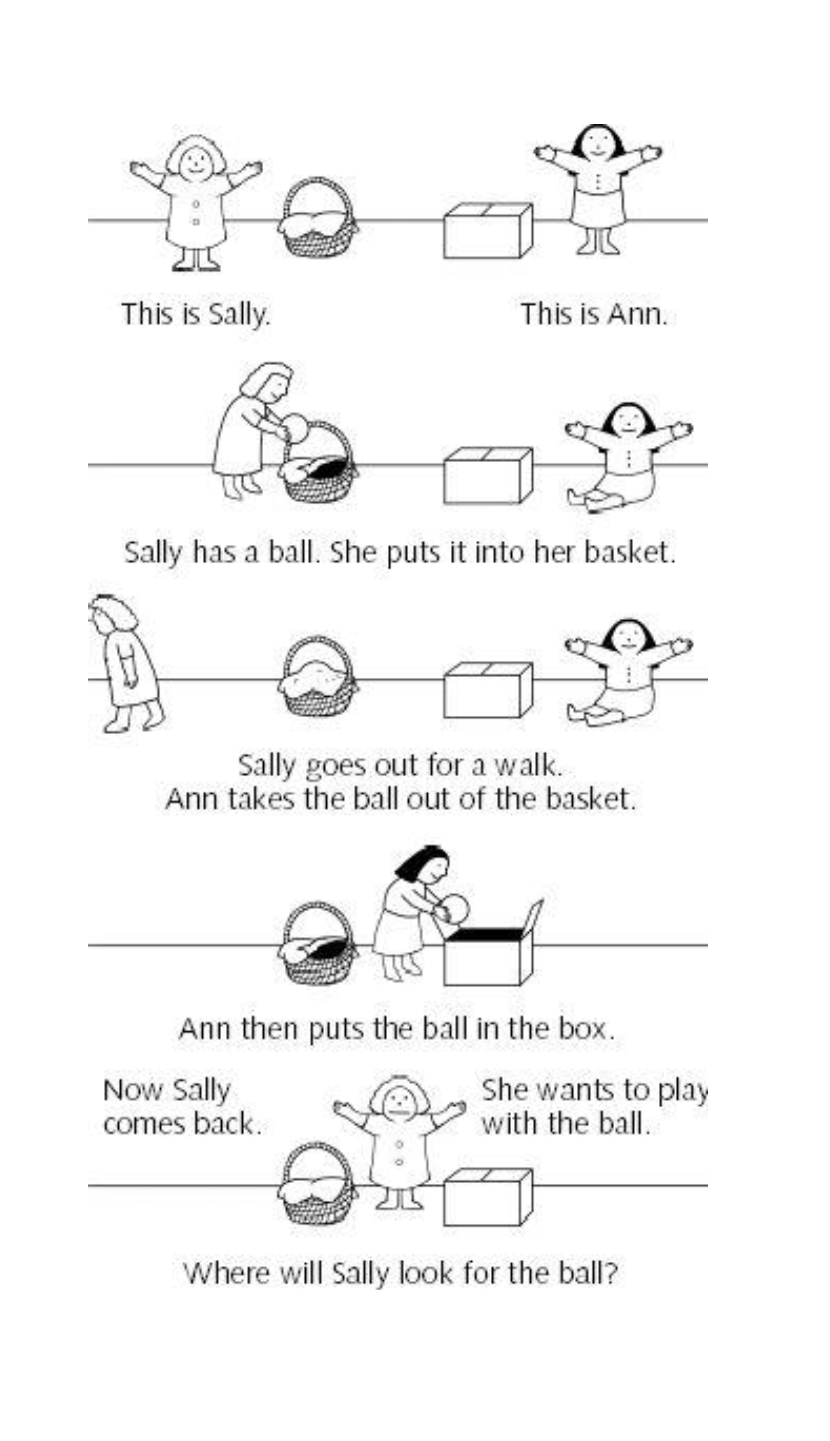

Others include the Sally-Anne task and the Smarties test.

Most children aged 5 and 4 pass the test, whereas 3 year old children typically fail (70%). This suggests a radical conceptual shift around the 4th birthday. Children can mentally represent the thoughts and beliefs of others.

Maxie and the Chocolate bar

First, Maxi puts some chocolate in the green cupboard, then leaves. Meanwhile, the children saw Maxi’s mother transfer the chocolate into the blue cupboard. Children were then asked to predict where Maxi would look for the chocolate when he returned to the room.

Sally-Anne task

Smarties test

3-year-olds fail (say pencils), but children over 4 years old successfully complete the task (say smarties).

Problems with the theory of mind tasks

Gradual change - there is evidence which suggests that children that are younger than 4 may be able to understand false belief but it depends on the demand of the task. Additionally, the tasks are only able to be passed or to be failed - meaning there is no scope for a performance that falls somewhere in between.

Factors that affect performance - language and wording of the question: 3-year-olds may interpret the question differently in comparison to 4-year-olds. For instance, “where will Maxi look eventually in order to get his chocolate?” or “What did you think was inside after we opened the lid?”

Language complexity - Siegal and Beattie (1991) modified Wimmer and Perner’s question by asking “Where will Maxi look first of all for his chocolate?” More 3 year olds passed and they concluded that some children’s errors stemmed from difficulty with the question.”

Other perspectives - De Villers suggests that the age at which false-belief tasks are passed correlates with language ability.

The false-belief task may underestimate preschoolers' social understanding by requiring specific language or cognitive skills that may not reflect their social capability accurately.

The three-way relationship between the task itself, what it is intended to measure (Theory of Mind), and other related skills, like language and social cognition, adds complexity. This questions whether false-belief tasks measure ToM directly or are influenced by other developmental skills

Problems with executive function (e.g., inhibition, working memory) may interfere with a child’s performance on false-belief tasks. If a child struggles with impulse control or remembering details, this could impact their ability to respond correctly, potentially confounding the results.

Salience of reality, Mitchell and Lacohee (1991)

Children were presented with pictures of

different items including Smarties. They were asked to select a picture of what they thought was inside and post it into a posting box. Following the opening of the tube and the discovery of pencils, children were asked when they posted their pictures and what they thought was inside.

This way, many three-year-olds gave the correct answer. Thus the key message is that when the false belief is explicitly stated or depicted in some way, children’s performance improves. They had found it easier to report their prior beliefs.

Implicit understanding of belief

Clements and Perner studied young children’s implicit understanding of belief, which is their unconscious, non-verbal grasp of others' beliefs, which they might not yet be able to express verbally.

The procedure followed: They showed the children a typical false belief task, then followed either the implicit or explicit prompt. For the implicit measure, eye movements of the were filmed, …

Verbal ability and theory of mind

Happé (1995) found that the performance of theory of mind was related to verbal ability. Language allows us to exchange our information about our mental states with others.

It was found that typically developing children with a verbal ability of 4 years old, were proposed to show a 50% probability of passing the first-order false belief task. However, this was not obtained with children with ASD until they acquire a verbal mental age of 9 years old and abobe.

Is language associated with ToM?

Language ability and false belief are strongly related (Milligan et al., 2007). Early language predicted later false beliefs (Milligan et al., 2007). Supported by studies done on children who are deaf (eg. Peterson & Siegal 1999; Russell et al., 1998).

Autism and how it relates to ToM

Social atypicality - social interactions, relationships, reading, and producing social cues.

Language problems - some may lack functional language, neologizing, and symbolic play.

Stereotypical and repetitive behaviour.

Defective ToM, described as “mind-blindness” implies difficulty in understanding or predicting others' thoughts and emotions. Simon Baron-Cohen (1995) and Leslie (1987) suggested the concept of mindblindness, that autistic individuals may struggle with tasks requiring ToM, such as understanding false beliefs or deception.

However, some researchers suggest that ToM difficulties are not a result of a deficit but rather a reflection of a different processing style. Frith and Happé (1994) proposed that the Weak Central Coherence theory, which means individuals with autism are unable to think holistically and focus on details instead. This can explain why autistic individuals may struggle with understanding social cues, which often require integrating multiple signals (e.g., facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language).

Executive dysfunction difficulties such as planning, flexible thinking, and inhibiting impulsive responses—contribute to the social and cognitive differences seen in autism. The Windows Task (Russell et al., 1991): This task involves showing children two boxes, one with a treat and one without. The participant is instructed to point to the empty box if they want to receive the treat. Many autistic individuals struggle with this task, as it requires inhibiting the instinct to point to the desired box. Failures on this task highlight executive dysfunction, particularly in the area of inhibition.

Do Children with Autism Lack an Understanding

of Others’ Minds?

Baron and Cohen et al. (1985) compared children with ASD, children with Down syndrome and typically developing children. The results showed that 80% of typically developing 4-year-old children and ones with Down syndrome with the mental age of 4 passed a false belief task, but only 20% of those with ASD. (Sally-Anne task)

Perner et al. (1989) also tested the ASD children with the Smarties task with similar results. Children with ASD also have difficulty with other tasks that require an appreciation of another’s Theory of Mind.

Тheory of Mind and emotions

Heerey, Keltner, and Capps (2003) assessed emotion recognition and the theory of mind in children with ASD, with 15 participants aged 8-15. The control children (without ASD), were shown to have a significantly better ability to recognize self-conscious emotions (embarrassment, pride, guilt, and shame). These emotions are more complex and require understanding social expectations and an awareness of how one's behavior appears to others. Children with ASD having a challenge in recognizing these emotions, aligns with the broader challenges in ToM, thus this study supports the idea that a deficit in ToM and social cognition can contribute to the difficulties that children with ASD have when navigating social situations and understanding socially nuanced emotions.

Theory of mind and empathy

Demurie, De Corel, and Roeyers (2011) found that 13 adolescent participants with ASD were significantly worse at the ToM task with “Reading the mind through the eyes.” It was also worse on an empathy accuracy task compared to the control of typically developing adolescents and those with ADHD.

An ‘absent self’

As proposed by Frith and Happé, this hypothesis suggests that children with ASD may experience difficulties with self-awareness. While they may have a basic sense of self-awareness (such as recognising themselves as distinct from others), they often have a reduced ability of high-order self-awareness—seeing themselves in a nuanced, social, or introspective light.

Lombardo et al. (2010), conducted a study using fMRI and explored neural self-representation in individuals with ASD. Participants made reflective (thoughts, feelings) and physical judgments about themselves and a familiar public figure (the British Queen). In typically developing individuals, self-judgments activated the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) more than judgments about others, showing distinct self-referential processing. However, ASD participants showed no such differential activation, suggesting they may process self-related information similarly to how they process information about others. This supports the absent-self hypothesis, indicating reduced social and emotional self-representation in ASD.