Biochemistry Chapter 12 Review

1/66

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

67 Terms

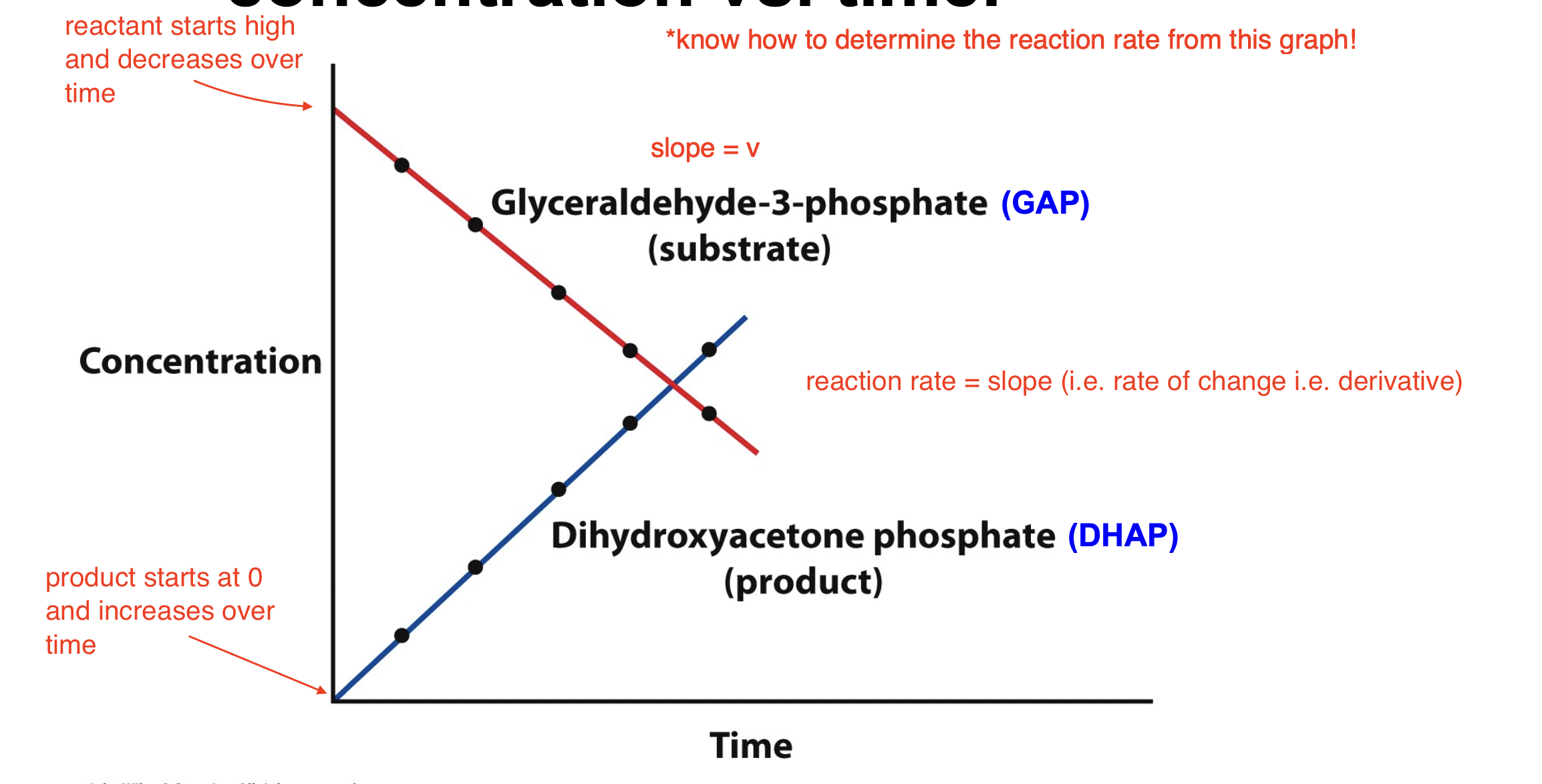

Enzyme kinetics is the study of ________________. The reaction rate (___________), measures the ______________ and can be described in two ways:

?

?

These equations relate ___________ to _________________.

rates of reactions catalyzed by enzymes; velocity v; speed of the reaction

Disappearance of substrate, A

Appearance of product, P

velocity; concentration of reactants and products

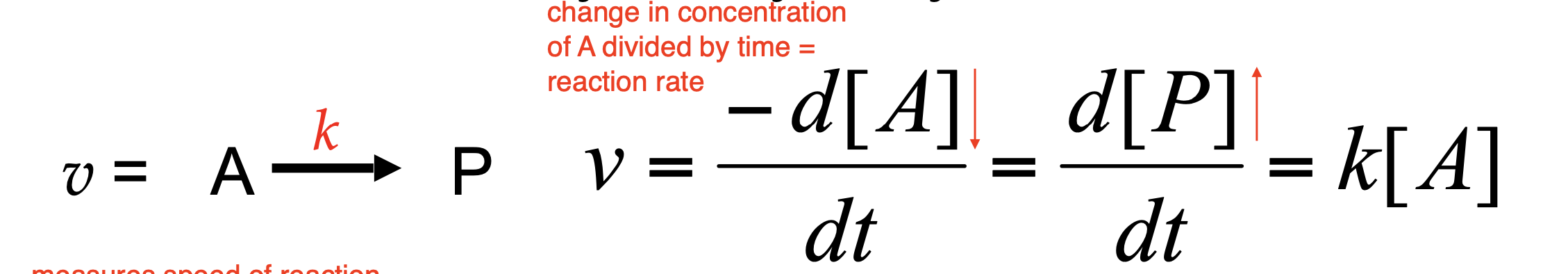

Explain the reaction catalyzed by triose phosphate isomerase

GAP is the reactant and DHAP is the product, isomerase is the enzyme

As [GAP] decreases, the [DHAP] increases

![<ul><li><p>GAP is the reactant and DHAP is the product, isomerase is the enzyme</p></li><li><p>As [GAP] decreases, the [DHAP] increases</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/ee3a1218-caae-4d1a-9c02-a21a72d74357.png)

How can a reaction rate be graphed?

Reaction velocity can be thought of as concentration vs. time

reactant starts high and decreases over time

product starts at 0 and increases over time

reaction rate = slope (i.e. rate of change i.e. derivative)

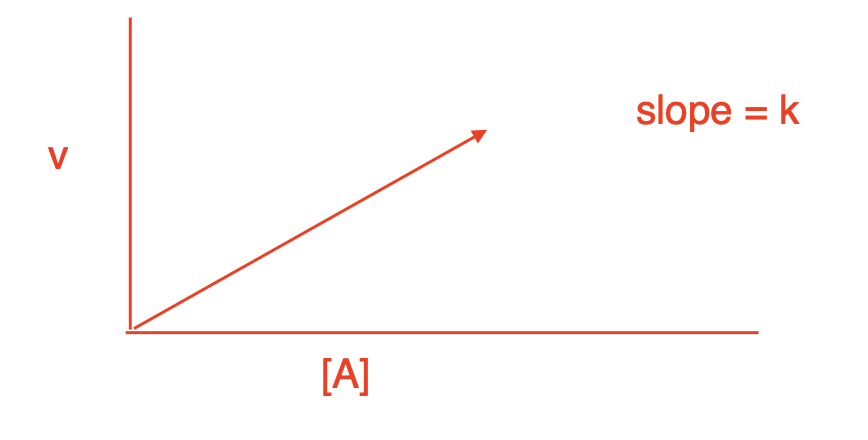

Rate equations describe _____________. A unimolecular reaction is ___________ and has a velocity (rate) that is ________________. The equation is ____________, where k is a ________________. Unimolecular reactions have a concentration vs. time graph that shows a ______________.

chemical process; first order; dependent on the concentration of only one substrate; v = k[A]; rate constant with unit of sec-1; linear relationship

![<p>chemical process; first order; dependent on the concentration of only one substrate; v = k[A]; rate constant with unit of sec<sup>-1</sup>; linear relationship</p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/e7886a26-2a40-4c63-b7af-de46653473d8.png)

A bimolecular (second order) reaction has a velocity (rate) that is ______________. The reaction equation is _______________, where k has units of __________.

dependent on two substrate concentrations; v = k[A][B]; M-1*sec-1

![<p>dependent on two substrate concentrations; v = k[A][B]; M<sup>-1</sup>*sec<sup>-1</sup></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/5e5d1305-efeb-4741-9f68-50c9c2052180.png)

What is the rate constant?

a proportionality factor that determines the speed of a chemical reaction

relates the reaction rate to the concentration(s) of the reactant(s) in a given rate equation

specific to a given reaction and depends on temperature

Explain Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

describes behavior of enzymatic reaction system

the first subreaction is forming the ES complex, which is a reversible reaction with a rate constant k1 (reverse reaction is k-1 or also called k3)

the second reaction is the creation of the product and the release of the enzyme from the ES complex, this is the rate limiting step and has a rate constant k2

since the rate of the reaction is essentially dependent on the concentration of the ES complex, we can rewrite the equation for the rate as v = k2[ES]

![<p>describes behavior of enzymatic reaction system</p><ul><li><p>the first subreaction is forming the ES complex, which is a reversible reaction with a rate constant k1 (reverse reaction is k-1 or also called k3)</p></li><li><p>the second reaction is the creation of the product and the release of the enzyme from the ES complex, this is the rate limiting step and has a rate constant k2</p></li><li><p>since the rate of the reaction is essentially dependent on the concentration of the ES complex, we can rewrite the equation for the rate as v = k2[ES]</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/de1071b3-9d27-4e24-a1a3-254d6b725362.png)

What assumptions do we need to make for the Michaelis-Menten equation to be true?

1) we have to assume the k2 subreaction is irreverseable (once product is produced it cannot go back to form substrate)

2) we have to assume there is only one type of substrate (multisubstrate reactions would not work) —> no 2nd order reactions!

3) assume steady state equilibrium

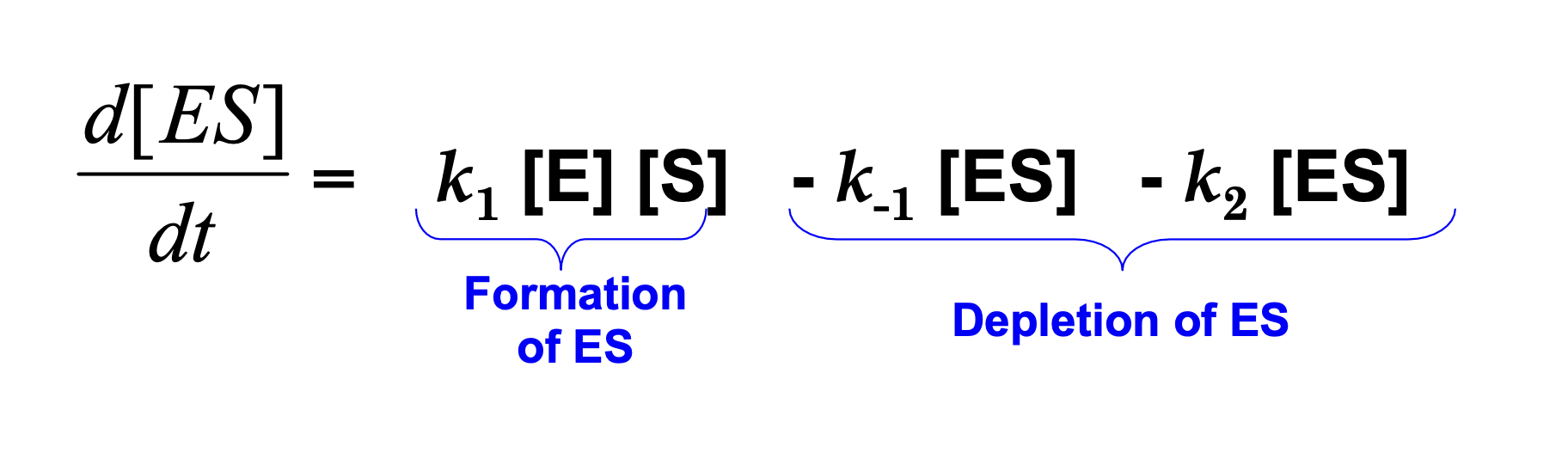

How else can we interpret d[ES]/dt?

What does “assume steady state equilibrium” mean?

For most of the duration of the reaction, [ES] remains steady as substrate is converted to product.

This means that the rate of formation of ES is equal to the rate of breakdown of ES. Recall:

k1[ES] = k-1[ES] - k2[ES]

so, this means that d[ES]/dt = 0

Under the physiologically common condition that substrate is in great excess over enzyme [S] >> [E]. With the exception of the initial and final stages of the reaction. Hence, the rate of synthesis of ES must equal its rate of consumption over most of the course of the reaction and [ES] can be treated as having a constant value.

![<p>For most of the duration of the reaction, [ES] remains steady as substrate is converted to product.</p><p>This means that the rate of formation of ES is equal to the rate of breakdown of ES. Recall:</p><p>k1[ES] = k<sub>-1</sub>[ES] - k2[ES]</p><p>so, this means that d[ES]/dt = 0</p><p>Under the physiologically common condition that substrate is in great excess over enzyme [S] >> [E]. With the exception of the initial and final stages of the reaction. Hence, the rate of synthesis of ES must equal its rate of consumption over most of the course of the reaction and [ES] can be treated as having a constant value.</p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/9c8c7428-4a53-4848-9cb5-0f182d350a99.png)

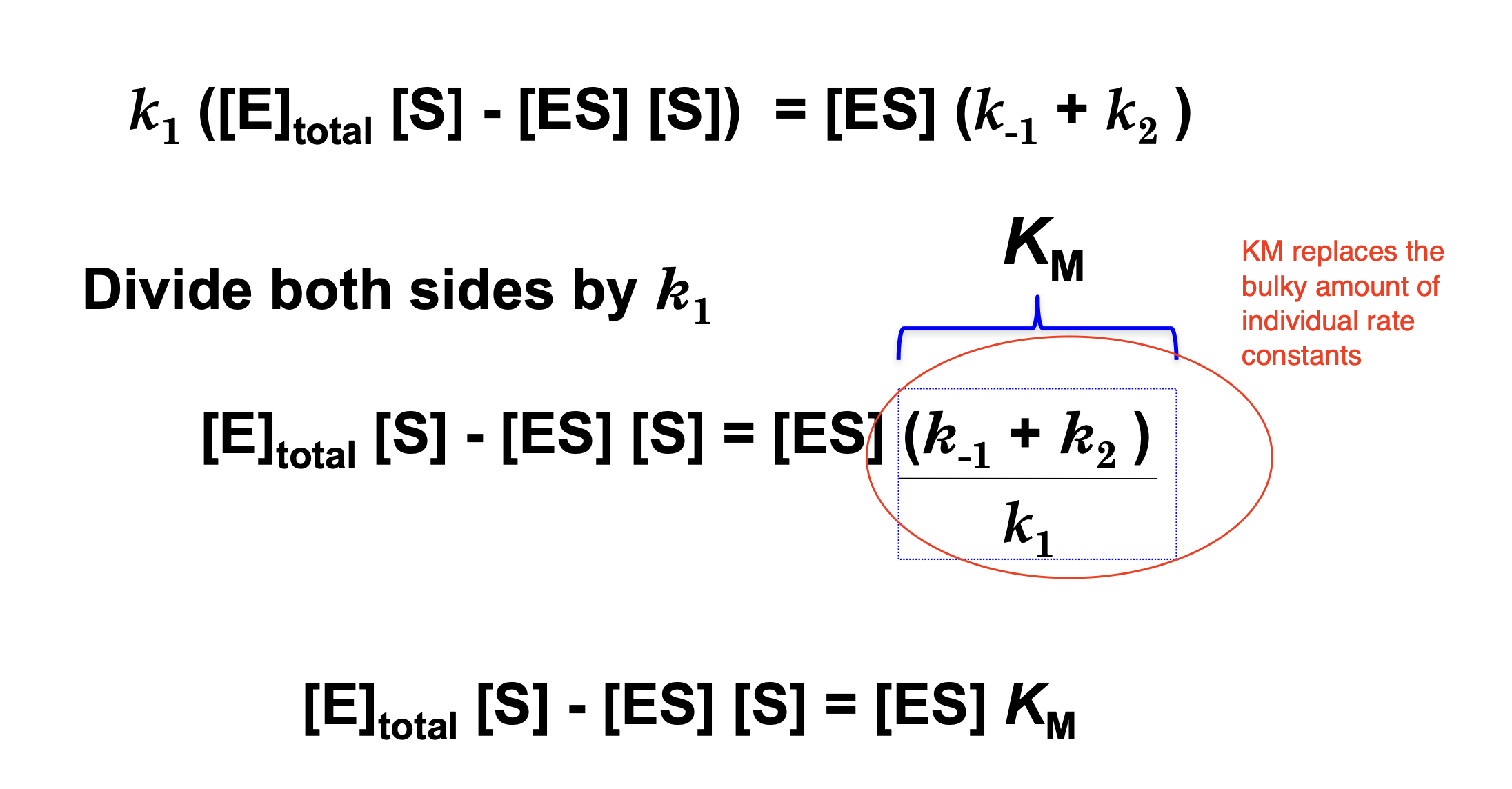

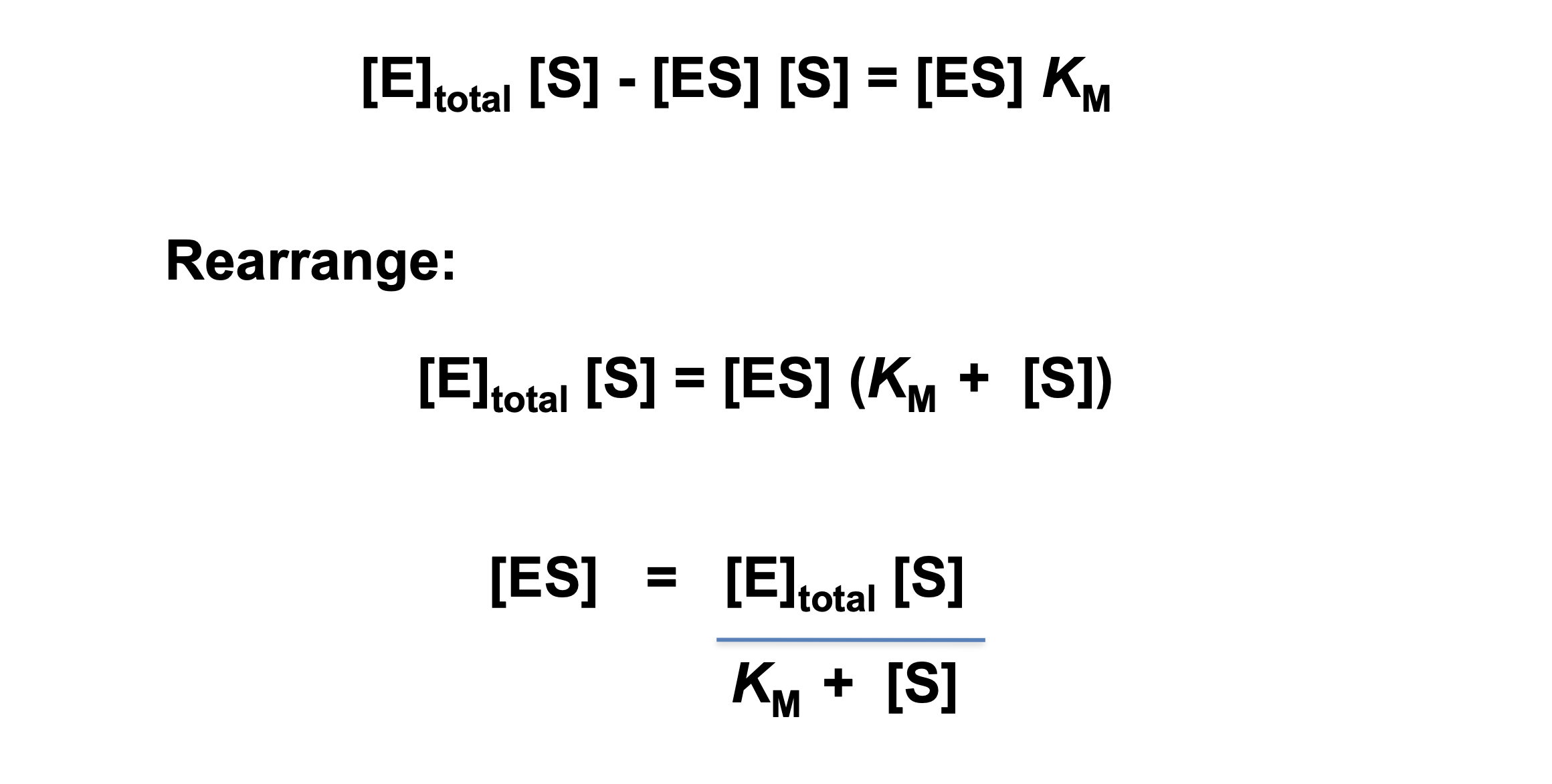

Derivation of the Michaelis-Menten Equation

Derivation of the Michaelis-Menten Equation

Derivation of the Michaelis-Menten Equation

Derivation of the Michaelis-Menten Equation

The rate-determining step in Michaelis-Menten kinetics is the breakdown of the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) into product (P):

ES —> E + P (recall rate constant is k2)

The rate of product formation is proportional to the amount of ES present:

v = k2[ES]

The fastest possible reaction rate occurs when all enzyme molecules are bound to substrate. In other words, at saturation:

[ES] = [E]total

Substituting this into the rate equation:

vmax = [E]total

The maximum velocity (Vmax) depends on the total amount of enzyme available and the rate at which each ES complex turns into product (k2, also called kcat). This means if every enzyme molecule is working at full capacity, the reaction proceeds at its maximum possible speed.

![<p><span>The </span><strong>rate-determining step</strong><span> in Michaelis-Menten kinetics is the breakdown of the </span><strong>enzyme-substrate complex (ES) </strong><span>into </span><strong>product (P):</strong></p><p>ES —> E + P (recall rate constant is k2)</p><p><span>The rate of product formation is proportional to the amount of </span><strong>ES</strong><span> present:</span></p><p><span>v = k2[ES]</span></p><p><span>The </span>fastest possible reaction rate<span> occurs when </span>all enzyme molecules are bound to substrate<span>. In other words, at </span>saturation<span>:</span></p><p><span>[ES] = [E]<sub>total</sub></span></p><p><span>Substituting this into the rate equation:</span></p><p>v<sub>max</sub> = [E]<sub>total</sub></p><p><span>The maximum velocity (Vmax) depends on the total amount of enzyme available and the rate at which each </span>ES complex <span>turns into product (k2, also called </span>kcat<span>). This means </span>if every enzyme molecule is working at full capacity, the reaction proceeds at its maximum possible speed<span>.</span></p><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/33b1f44b-7111-4ac1-bd0e-30bbf6803050.png)

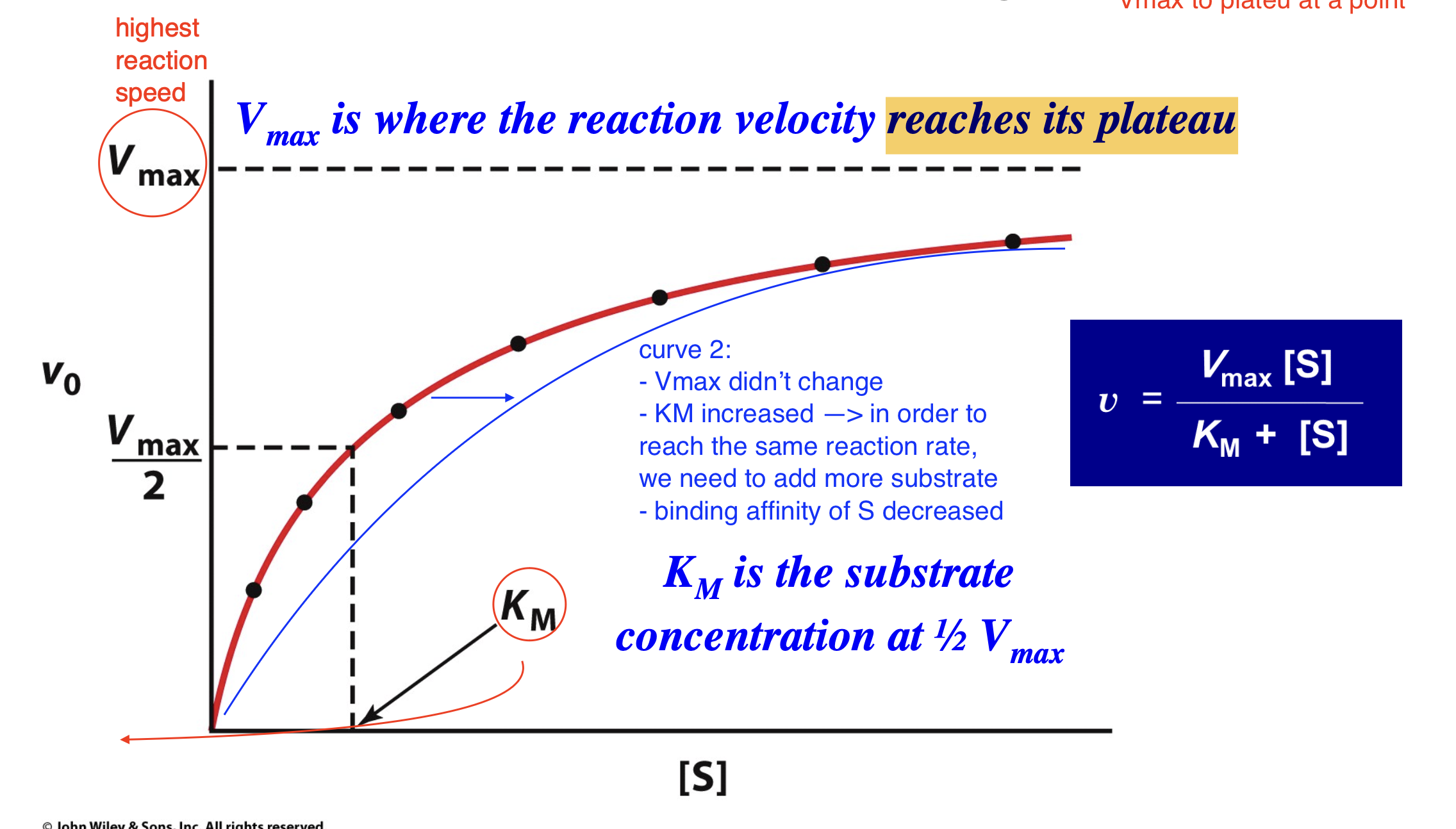

What happens when [S] = KM?

At the substrate concentration at which [S] = KM, v = ½ Vmax so that KM is the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half-maximal.

![<p>At the substrate concentration at which [S] = <em>K</em><span style="font-size: 16px; font-family: Arial"><sub>M</sub>,</span> v = ½ V<span style="font-size: 16px; font-family: Arial"><sub>max</sub></span> so that <em>K</em><span style="font-size: 16px; font-family: Arial"><sub>M</sub></span> is the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half-maximal.</p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/1b129966-8d82-4673-8ac8-239e01595124.png)

What is the shape of the Michaelis-Menten graph?

hyperbolic

Explain the shape of the Michaelis-Menten graph i.e. why it is not linear

if we start to increase the amount of substrate into the tube, how will the initial velocity change? It won’t keep increasing, eventually all the enzymes will be saturated and no more substrates will be able to react. Think of enzymes like a limited number of machines, after you fill all of them it doesn’t matter how many more substrates you add, the production rate will stay the same bc there are no more machines

but… if we add more enzymes the reaction rate can increase again!

What is a limitation of the Michaelis-Menten equation?

it is very hard to accurately measure Vmax bc the actual curve will never reach the asymptote, this means we also cannot accurately measure KM

…however, we can do some math to find Vmax and KM more accurately

What happens if the Michaelis-Menten curve is shifted to the right?

still starts at 0 and plateaus at the same height (same Vmax)

KM has increased —> in order to reach the same reaction rate, we need to add more substrate

binding affinity of S decreased

Define KM

KM is the [S] where v (reaction rate) is equal to 1/2 of Vmax

tells us binding affinity of substrate —> higher KM, lower binding affinity (we need more substrate to saturate the same amount of enzymes)

Compare the Michaelis-Menten curve to the graph on slide 5, what causes this difference?

slide 5 graph assumes there is an unlimited amount of enzymes —> this would suggest a linear relationship because as substrate increases rate will simply increase too

the Michaelis-Menten curve represents a real world system, because enzymes are going to be limited, this causes Vmax to plateu at a point

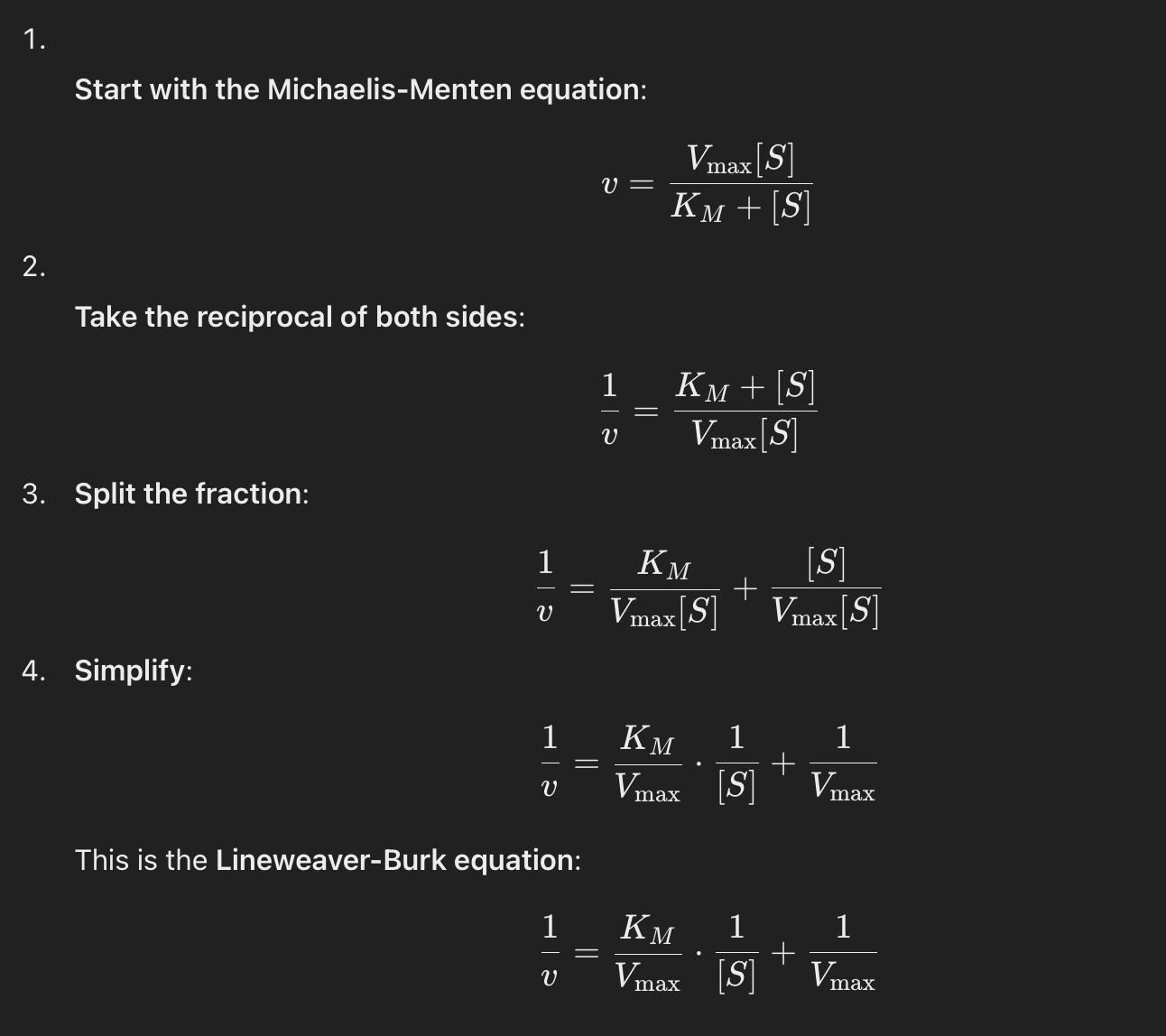

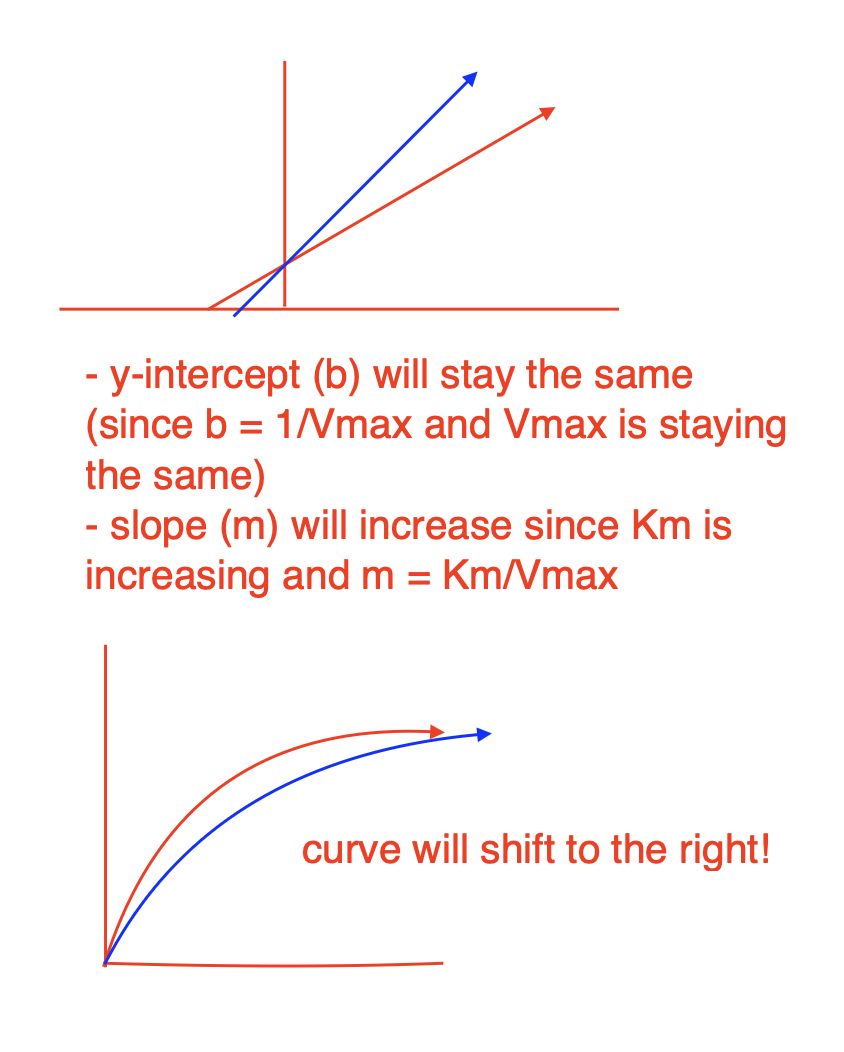

Explain how to convert Michaelis-Menten equation to Lineweaver-Burk equation

The Lineweaver-Burk plot linearizes Michaelis- Menten kinetics data. This modification allows us to find Vmax and KM more accurately!

y = mx+b —> linear relationship

Lineweaver-Burk Plot

1/Vmax —> y-intercept

-1/KM —> x-intercept

slope = KM/Vmax

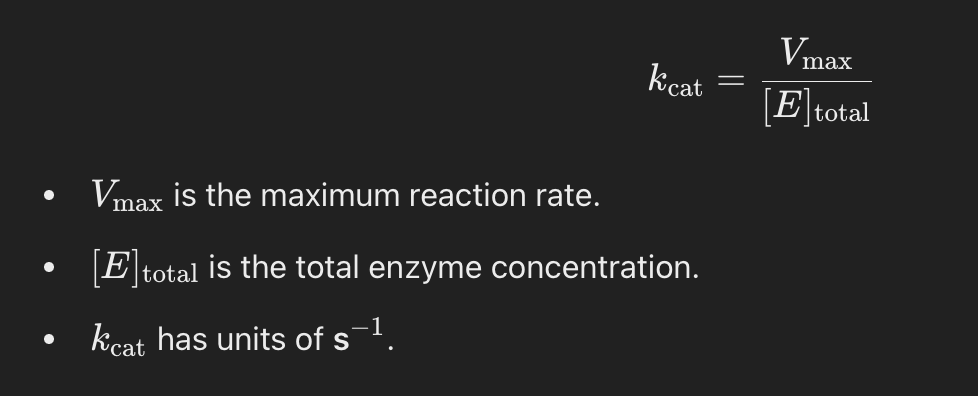

Explain how the magnitude of KM varies with the identity of the enzyme and the substrate

Enzymes evolved for high efficiency (e.g., carbonic anhydrase) often have low KM because they need to function efficiently at low substrate concentrations.

Less specific or regulatory enzymes (e.g., glucokinase) may have higher KM to allow flexibility in response to substrate levels.

Enzymes prefer their natural substrates, so their KM is typically lowest for the preferred substrate.

Substrates with weaker interactions require higher concentrations to reach half Vmax, leading to higher KM.

Also:

Enzyme Mutations: Changes in active site structure can increase or decrease KM.

pH and Temperature: Affect enzyme-substrate interactions and can alter KM.

Presence of Cofactors/Inhibitors: Competitive inhibitors increase apparent KM.

Allosteric Regulation: Enzymes with allosteric sites may show variable KM depending on activators or inhibitors.

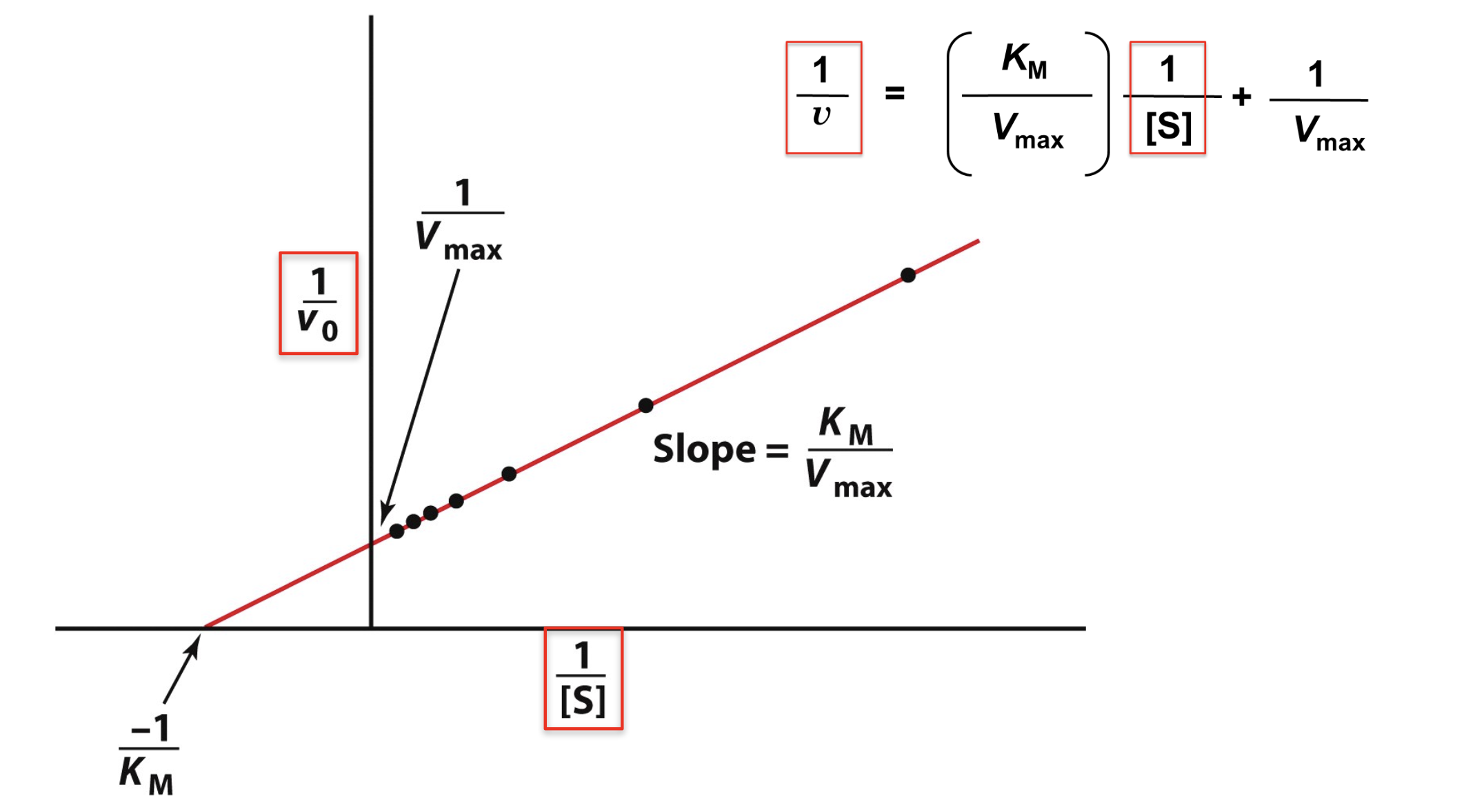

What is kcat?

The catalytic constant, or turnover number (kcat), represents the number of substrate molecules converted into product per second per enzyme molecule when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate.

A higher kcat means the enzyme can process more substrate molecules per second.

What is catalytic efficiency?

kcat/KM is called the catalytic efficiency and measures how efficiently an enzyme converts substrate into product under physiological conditions (where substrate is not saturating).

If KM is low → enzyme binds substrate tightly.

If kcat is high → enzyme processes substrate quickly.

The best enzymes have high kcat and low KM → meaning they are both fast and efficient at binding substrate.

Explain the diffusion limit

Some enzymes are so efficient that their reaction rate is only limited by how fast substrate molecules can diffuse into the active site!

Enzymes in this range catalyze a reaction almost every time they encounter a substrate molecule.

108 - 109 M-1s-1 is the diffusion limit

Not all enzymes fit the Michaelis-Menten model, why is this?

Some enzymes have multiple substrates

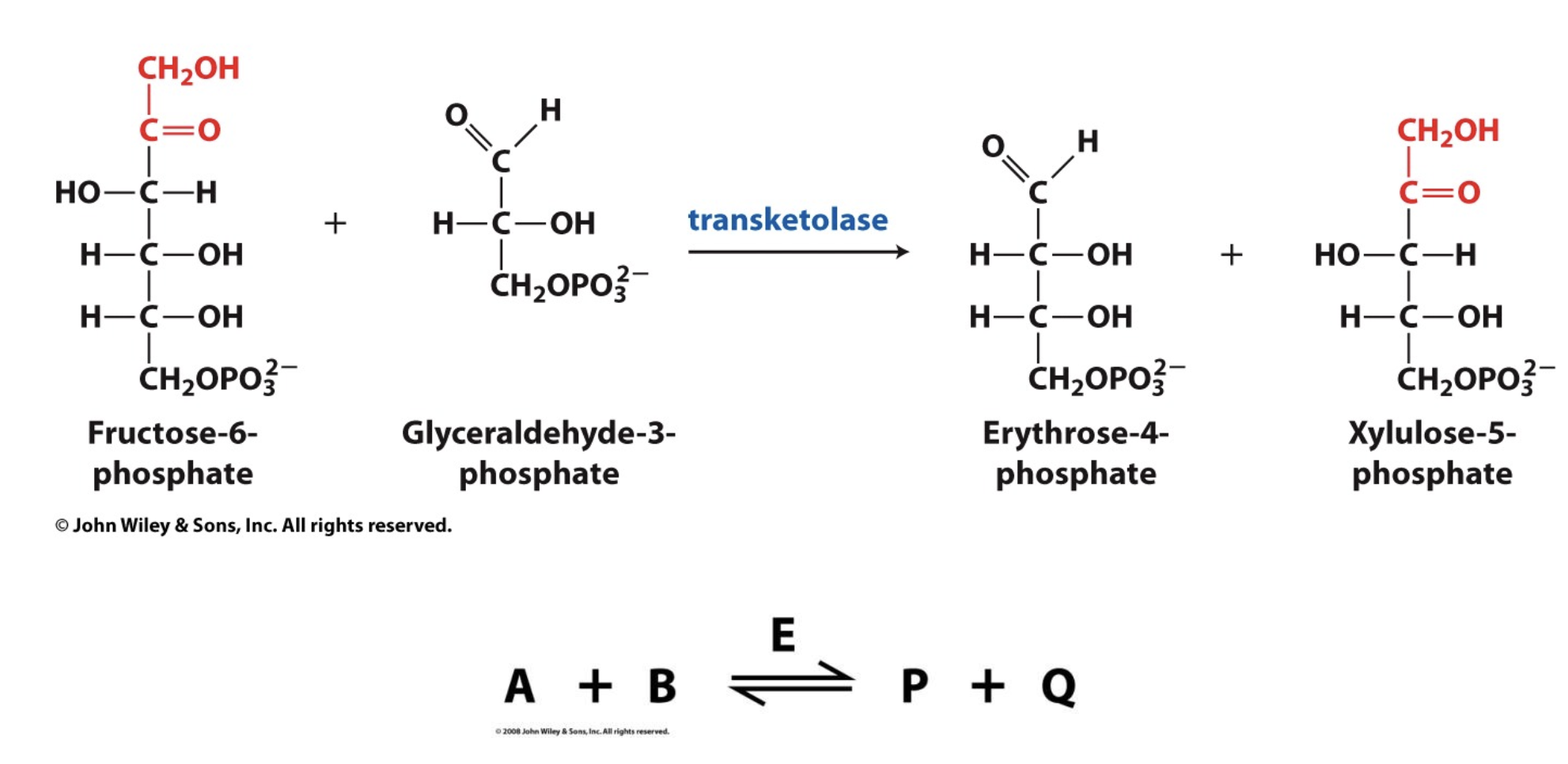

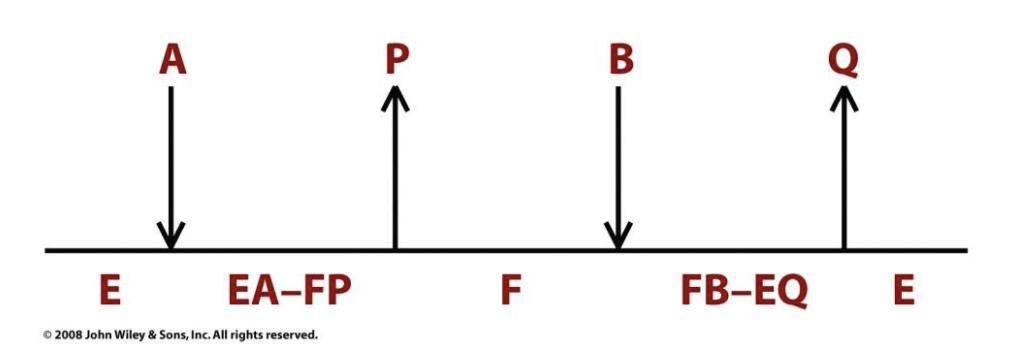

Bisubstrate Reaction Mechanisms

Bisubstrate reactions involve two substrates and typically result in two products. These are common in metabolism and enzyme catalysis, such as kinase reactions (which transfer phosphate groups) and oxidoreductase reactions (which involve electron transfer).

There are two main classes of bisubstrate reaction mechanisms:

Sequential (Single-Displacement) Mechanism

Ping-Pong (Double-Displacement) Mechanism

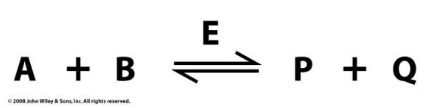

Sequential Reactions

All substrates must combine with the enzyme before a reaction can occur and products be released.

Two types:

ordered sequential

random sequential

*Enzyme forms a ternary complex (E·S1·S2) with both substrates before catalysis

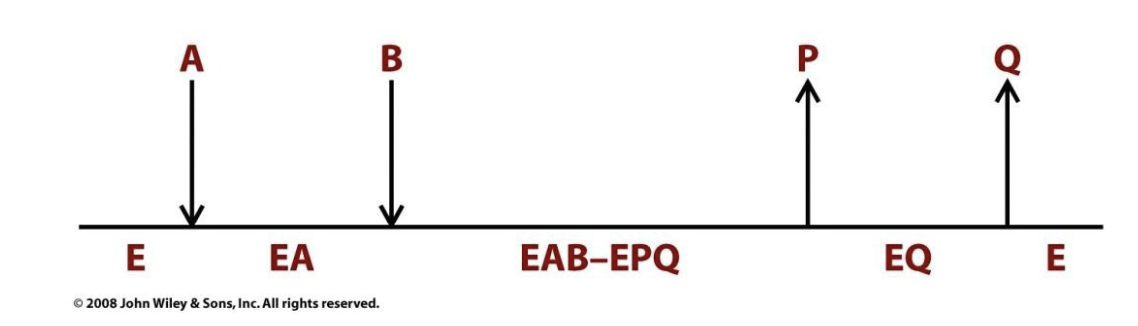

Ordered Sequential

One substrate must bind first, then the second substrate binds.

After catalysis, the first product is released, then the second product.

Example: Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

NADH binds first, then pyruvate → catalysis occurs → lactate is released, then NAD⁺ leaves.

Many NAD+ and NADP+ requiring dehydrogenases follow an ordered bisubstrate mechanism.

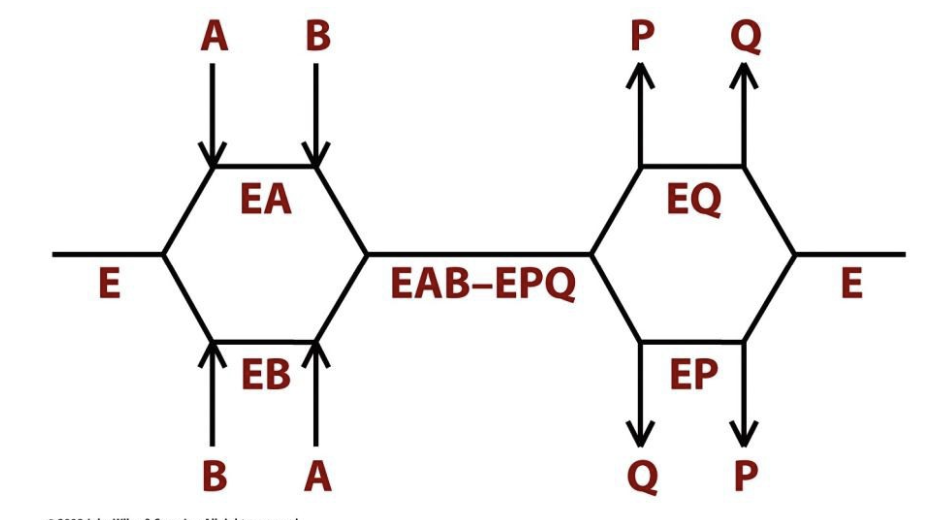

Random Sequential

Substrates can bind in any order, and products can be released in any order.

Example: Creatine kinase

ATP and creatine can bind in any order → reaction → ADP and phosphocreatine can leave in any order.

Some dehydrogenases and kinases operate through Random bisubstrate mechanisms.

Ping Pong Reactions

Group-transfer reactions in which one or more products are released before all substrates have been added.

One substrate binds, undergoes reaction, and releases the first product.

The enzyme is modified in the process.

The second substrate binds, reacts with the modified enzyme, and the second product is released.

In Ping Pong reactions, the substrates A and B do not encounter one another on the surface of the enzyme.

Many enzymes, including trypsin, transaminases, and some flavoenzymes, react with Ping Pong mechanisms.

Example: Aspartate Aminotransferase

Aspartate binds, donates an amino group to the enzyme, and oxaloacetate leaves.

The enzyme is now modified.

α-Ketoglutarate binds, accepts the amino group, and glutamate is released.

*No ternary complex is formed—substrates interact one at a time with an enzyme intermediate in between.

Many substances alter the activity of an enzyme by ___________ and/or ___________. Substances that reduce an enzyme's activity in this way are known as _____________. A large part of the _____________ consists of ___________.

combining with it in a way that influences the binding of substrate; its turnover number; inhibitors; modern pharmaceutical arsenal; enzyme inhibitors

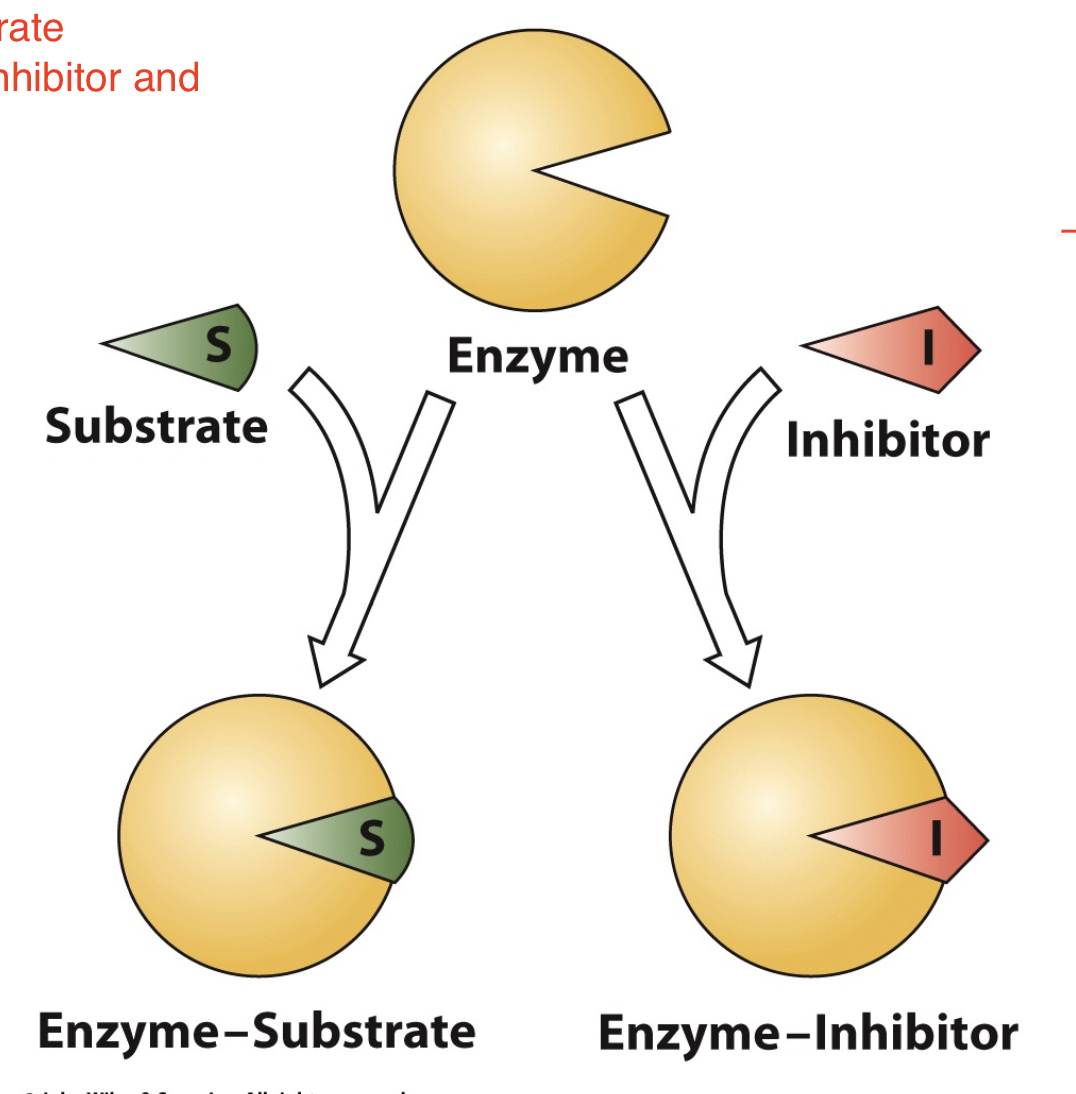

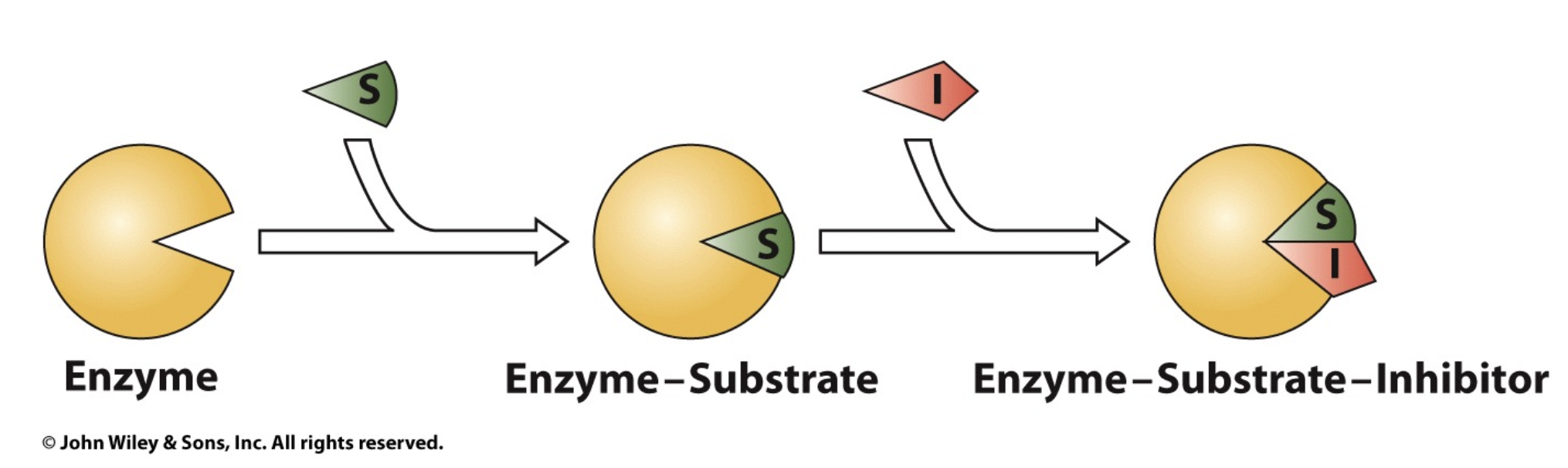

Competitive Inhibition

A substance that competes directly with a normal substrate for an enzyme's substrate-binding site is known as a competitive inhibitor. Such an inhibitor usually resembles the substrate.

similar in structure to substrate —> inhibitor can enter active site and thus “compete” with substrate

some machines will be blocked by the inhibitor and thus the reaction cannot take place

The target for competitive inhibitors is…

the free enzyme!

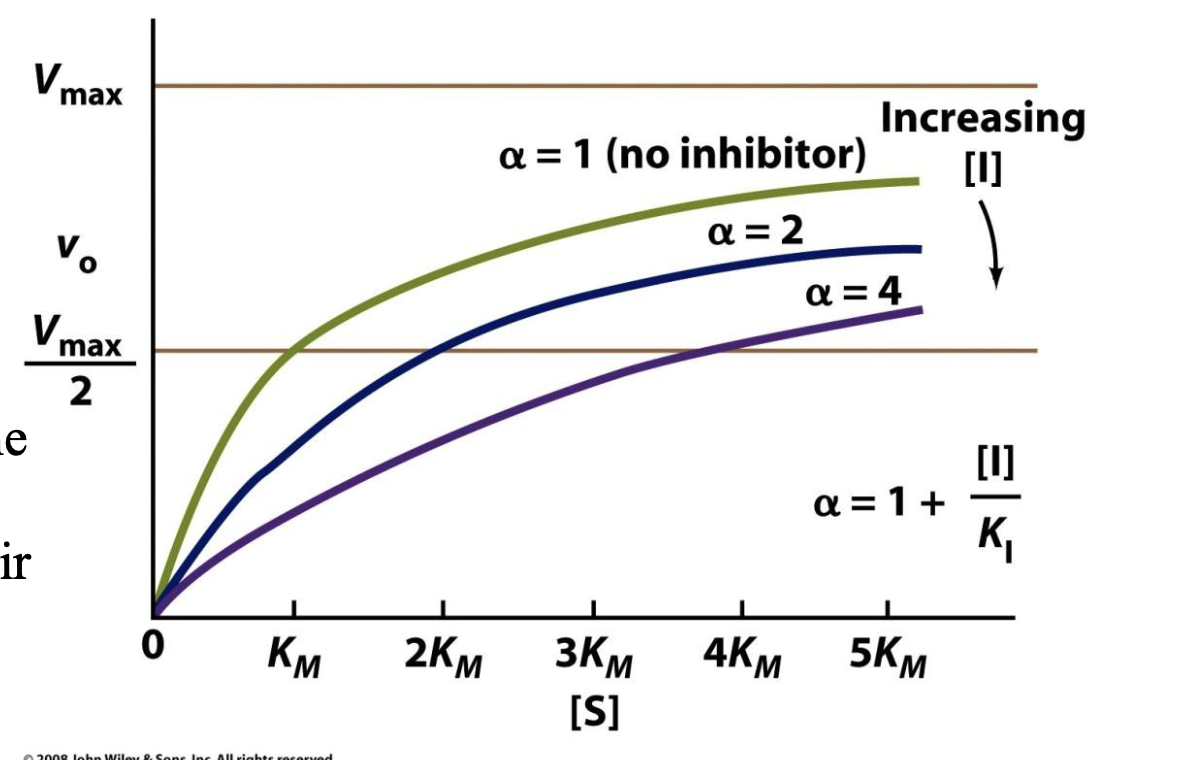

How does Vmax and KM change for competitive inhibition?

Vmax won’t change bc if we introduce more and more substrate eventually the substrate will outcompete the inhibitor

Km will increase, Km is the substrate as which v = 1/2 Vmax, we need more substrate to approach 1/2 Vmax

General reaction scheme competitive inhibition

A competitive inhibitor reduces the conc of free enzyme available for substrate binding. The presence of I makes [S] appear to be less than it really is (makes KM appear to be larger than it really is). However, increasing [S] can overwhelm a competitive inhibitor. As [S] approaches infinity, vo approaches Vmax for any concentration of inhibitor.

![<p>A competitive inhibitor reduces the conc of free enzyme available for substrate binding. The presence of I makes [S] appear to be less than it really is (makes K<span style="font-size: 12px; font-family: "Times New Roman"">M </span>appear to be larger than it really is). However, increasing [S] can overwhelm a competitive inhibitor. As [S] approaches infinity, v<span style="font-size: 12px; font-family: "Times New Roman"">o </span>approaches V<span style="font-size: 12px; font-family: "Times New Roman"">max </span>for any concentration of inhibitor.</p><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/2a0fdb25-0f33-4a2f-bba8-59001d191968.png)

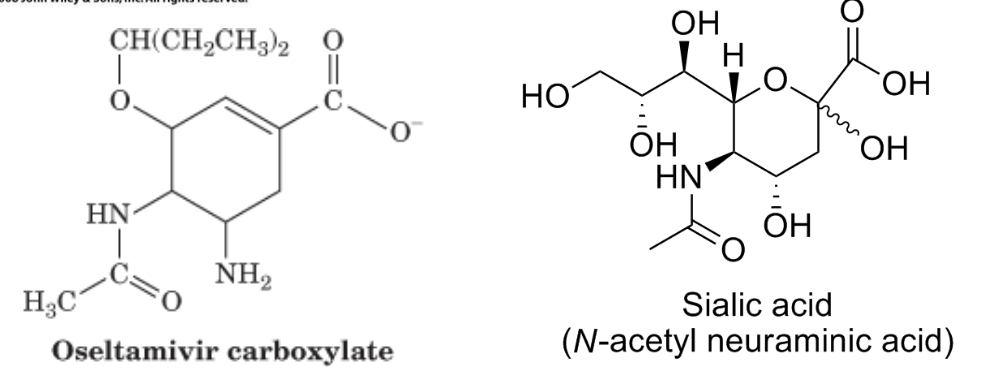

Tamiflu and competitive inhibition

Tamiflu significantly limits the production of the flu virus as a competitive inhibitor of influenza neuraminidase when is hydrolyzed to oseltamivir carboxylate in the liver. Neuraminidase hydrolyzes sialic acids of membrane glycoproteins to help the viral particles escape from the host cell surface.

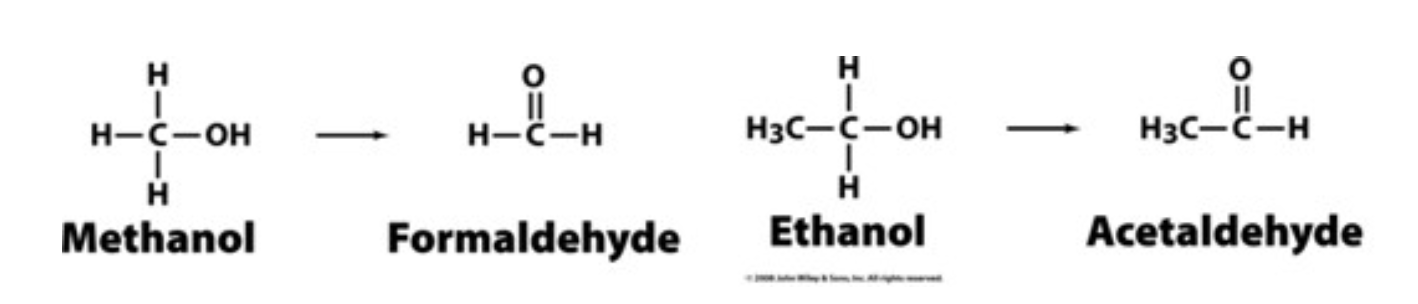

Methanol and competitive inhibition

Competitive inhibition is the principle behind the use of ethanol to treat methanol poisoning. Methanol itself is only mildly toxic. However, the liver enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase converts methanol to the highly toxic formaldehyde, only small amounts of which cause blindness and death. Ethanol competes with methanol for binding to the active site of liver alcohol dehydrogenase, thereby slowing the production of formaldehyde from methanol. Ethanol is converted to the readily metabolized acetaldehyde. A large portion of the methanol will be harmlessly excreted from the body in the urine before it can be converted to formaldehyde.

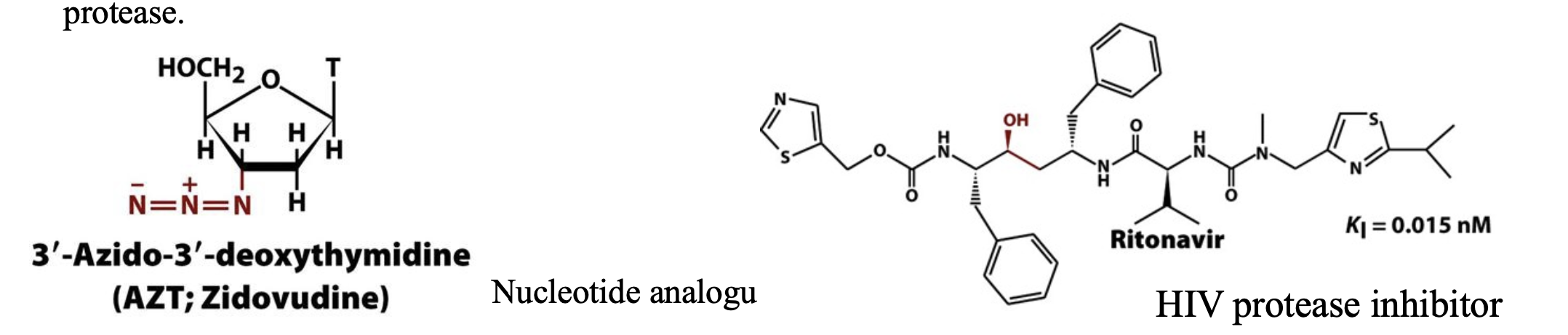

HIV and competitive inhibition

In the first steps of infection, HIV attaches to a target cell and injects its genetic RNA material. The viral RNA is transcribed into DNA by a viral enzyme called reverse transcriptase to produce more viral RNA and proteins for packaging it into new viral particles. Most of the viral proteins are synthesized as parts of larger polypeptide precursors known as polyproteins. Consequently , proteolytic processing by the virally encoded HIV protease to release these viral proteins is necessary for viral reproduction. In the absence of an effective vaccine for HIV, efforts to prevent and treat AIDS have led to the development of compounds that inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase and HIV protease.

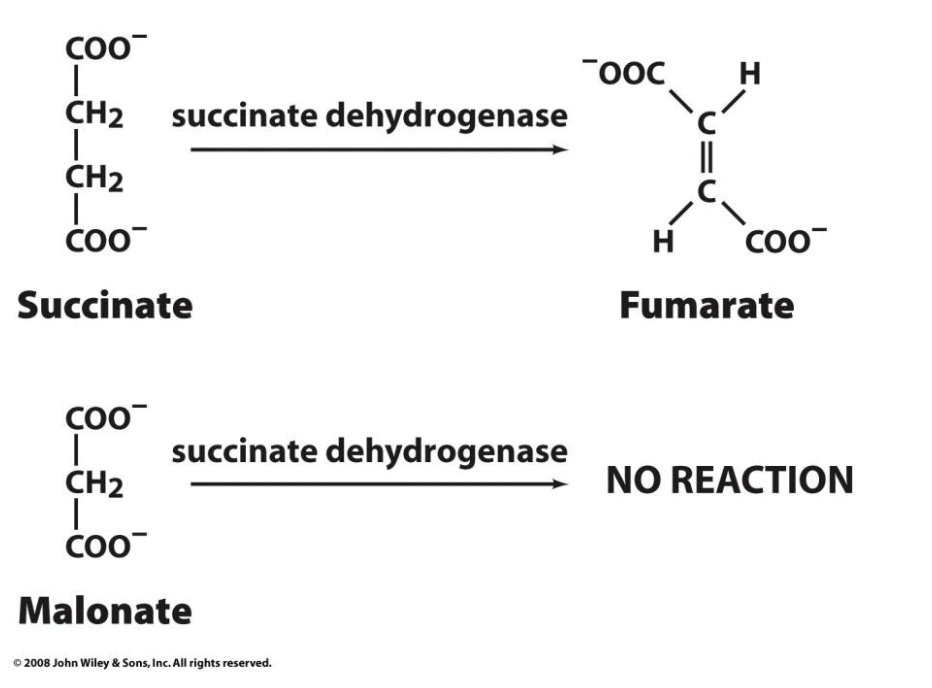

Succinate dehydrogenase and competitive inhibition

Succinate dehydrogenase, a citric acid cycle enzyme that converts succinate to fumarate, is competitively inhibited by malonate. Malonate is then a competitive inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase.

Explain product inhibition

Product inhibition occurs when the product of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction binds to the enzyme and prevents further catalysis.

Since the product is structurally similar to the substrate, it can bind to the active site or an allosteric site, interfering with enzyme function.

This is a common regulatory mechanism in metabolic pathways to prevent overproduction of a product.

Example:

Hexokinase (an enzyme that phosphorylates glucose) is inhibited by glucose-6-phosphate, the product of the reaction.

When too much glucose-6-phosphate accumulates, it binds to hexokinase and slows down further glucose phosphorylation.

Explain transition state analogs

Transition state analogs are molecules that mimic the high-energy transition state of a substrate during an enzymatic reaction.

Because enzymes are evolved to bind most tightly to the transition state, these analogs often act as potent inhibitors.

Unlike normal substrate analogs (which resemble the starting material), transition state analogs bind more strongly to the enzyme and block catalysis.

Example:

Penicillin is a transition state analog that inhibits bacterial transpeptidase, an enzyme needed for bacterial cell wall synthesis.

It mimics the transition state of the normal substrate, binding irreversibly and stopping bacterial growth.

How Are Product Inhibition & Transition State Analog Inhibition Related?

Both rely on the principle of structural similarity to the enzyme’s natural substrate or intermediate.

Products inhibit enzymes because they resemble the original substrate and can still fit into the active site.

Transition state analogs are even more effective because they mimic the most tightly bound intermediate in the reaction, making them some of the strongest inhibitors known.

competitive inhibitor Michaelis-Menten plot (with vs. without)

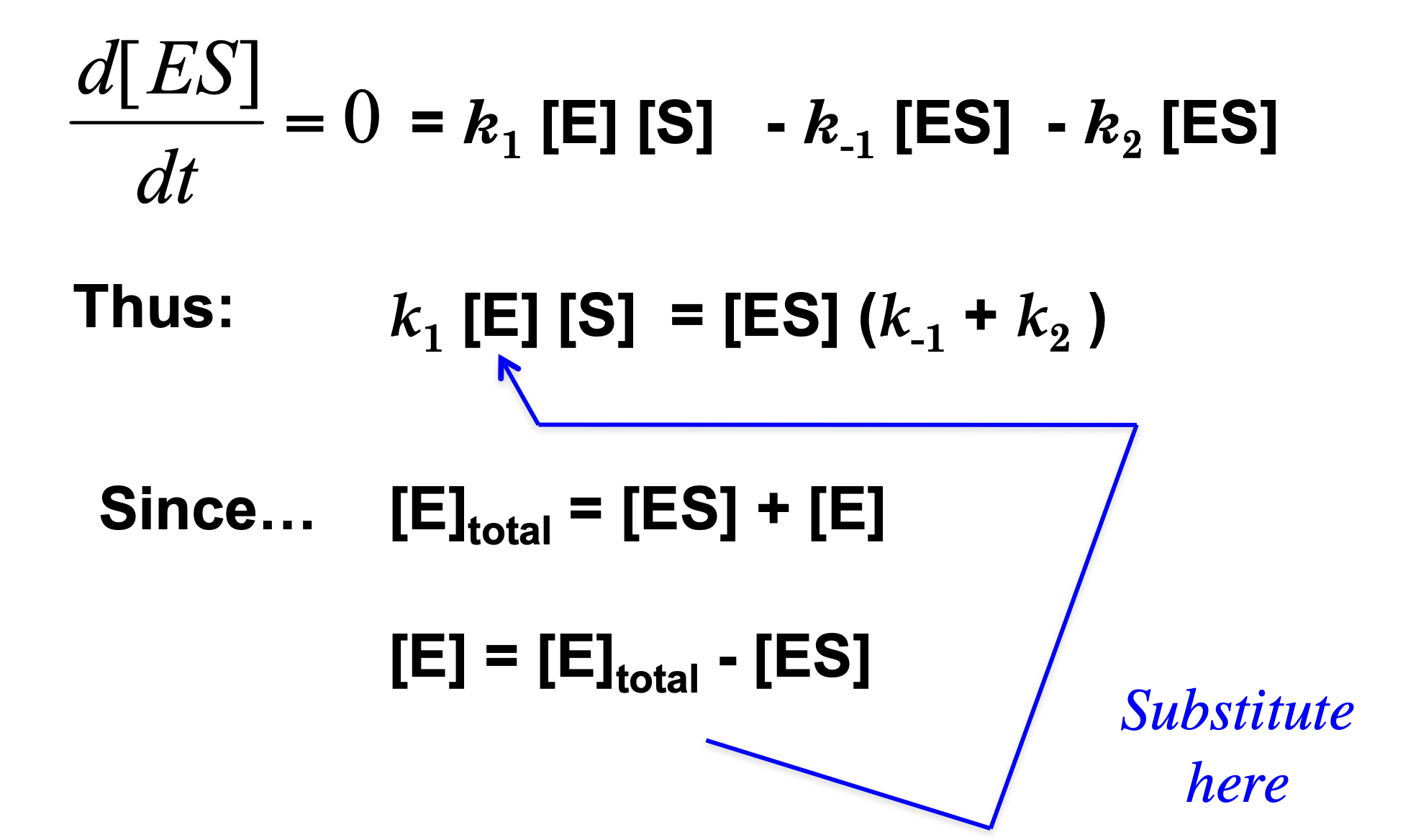

Explain how KI values tell us about competitive inhibitors

1. What is KI?

KI (the inhibition constant) measures how strongly an inhibitor binds to an enzyme.

A lower KI value means stronger binding (i.e., the inhibitor is more effective).

α is the coefficient telling us by what factor KM increases during competitive inhibition, and we can define α with:

α = 1 + [I]/KI

2. Why Compare KI Values of Different Inhibitors?

Different inhibitors have different chemical structures.

If one inhibitor has a much lower KI than another, it suggests a better fit in the active site, meaning its structure more closely resembles the enzyme’s preferred binding shape.

By analyzing KI values across inhibitors, researchers can map out which molecular features are important for binding.

3. How Does This Reveal Active Site Properties & Catalysis?

If an enzyme binds some inhibitors more tightly than others, this suggests certain chemical interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) are critical in substrate binding.

This can reveal details about how the enzyme catalyzes its reaction, since substrate binding is the first step in catalysis.

Scientists can design better drugs (enzyme inhibitors) by studying which structures bind best.

![<p><span>1. What is KI?</span></p><ul><li><p>KI (the inhibition constant) measures how strongly an inhibitor binds to an enzyme.</p></li><li><p>A lower KI value means stronger binding (i.e., the inhibitor is more effective).</p></li><li><p>α is the coefficient telling us by what factor KM increases during competitive inhibition, and we can define α with:</p></li></ul><p>α = 1 + [I]/KI</p><p></p><p><span>2. Why Compare KI Values of Different Inhibitors?</span></p><ul><li><p>Different inhibitors have different chemical structures.</p></li><li><p>If one inhibitor has a much lower KI than another, it suggests a better fit in the active site, meaning its structure more closely resembles the enzyme’s preferred binding shape.</p></li><li><p>By analyzing KI values across inhibitors, researchers can map out which molecular features are important for binding.</p></li></ul><p></p><p><span>3. How Does This Reveal Active Site Properties & Catalysis?</span></p><ul><li><p>If an enzyme binds some inhibitors more tightly than others, this suggests certain chemical interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) are critical in substrate binding.</p></li><li><p>This can reveal details about how the enzyme catalyzes its reaction, since substrate binding is the first step in catalysis.</p></li><li><p>Scientists can design better drugs (enzyme inhibitors) by studying which structures bind best.</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/17858585-c968-4c78-af24-a3f5435dac4f.png)

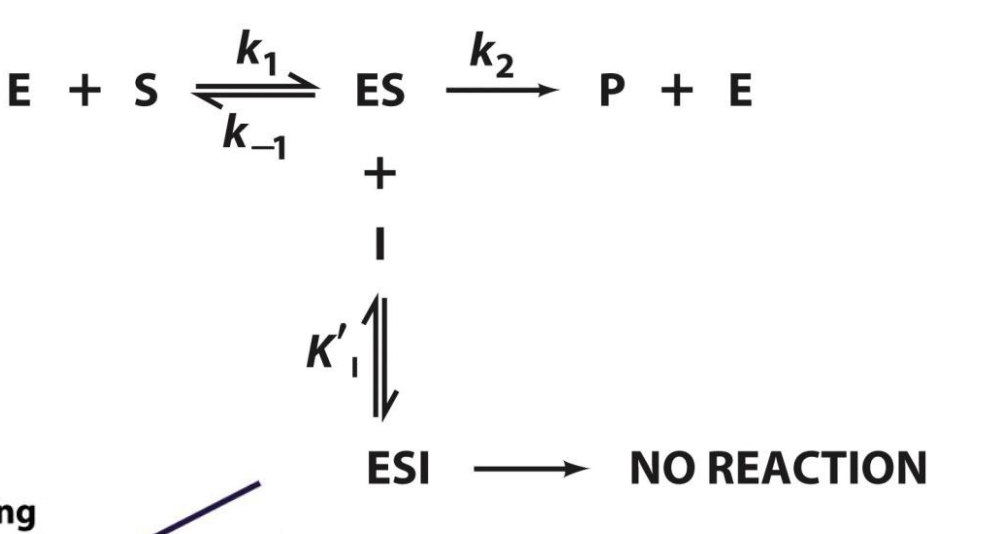

Uncompetitive Inhibition

Inhibitor can insert itself into ES complex and cause enzyme to have conformational change, and this will destroy the shape of the active site and thus slow the rate of the reaction

does not compete with substrate! works WITH substrate

uncompetitive inhibitors bind to the ES complex

How does Vmax and KM change for uncompetitive inhibition?

both Vmax and Km will reduce the same factor

The inhibitor locks the enzyme in the ES complex, preventing product formation.

This removes some enzyme from being catalytically active, effectively reducing the total amount of available enzyme.

Since Vmax = kcat[E]total and the total active enzyme is reduced, Vmax decreases.

Normally, KM is the substrate concentration at which the reaction reaches half of Vmax.

In uncompetitive inhibition, the inhibitor removes some of the ES complex, shifting the equilibrium toward more ES formation (by Le Chatelier’s principle).

This makes it seem like the enzyme has a higher affinity for the substrate, effectively lowering KM.

slope (m) will not change since Km/Vmax ratio is the same

y-intercept (b) increases since Vmax is reducing and b = 1/Vmax

![<ul><li><p>both Vmax and Km will reduce the same factor</p><ul><li><p>The inhibitor locks the enzyme in the ES complex, preventing product formation.</p></li><li><p>This removes some enzyme from being catalytically active, effectively reducing the total amount of available enzyme.</p></li><li><p>Since Vmax = k<sub>cat</sub>[E]<sub>total </sub><span>and the total active enzyme is reduced, </span>Vmax decreases<span>.</span></p></li><li><p>Normally, KM is the substrate concentration at which the reaction reaches half of Vmax.</p></li><li><p>In uncompetitive inhibition, the inhibitor removes some of the ES complex, shifting the equilibrium toward more ES formation (by Le Chatelier’s principle).</p></li><li><p>This makes it seem like the enzyme has a higher affinity for the substrate, effectively lowering KM.</p></li></ul></li><li><p>slope (m) will not change since Km/Vmax ratio is the same</p></li><li><p>y-intercept (b) increases since Vmax is reducing and b = 1/Vmax</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/172b0500-96b7-4554-a579-6ffb01613520.png)

General reaction scheme for uncompetitive inhibition

The binding of uncompetitive inhibitor, which need not resemble substrate, presumably distorts the active site, thereby rendering the enzyme catalytically inactive.

Explain how KI values tell us about uncompetitive inhibitors

K’I represents the affinity of the uncompetitive inhibitor for the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) and is given by:

K’I = [ES][I]/[ESI]

a lower K’I value means that the inhibitor binds more tightly to the ES complex

a higher K’I value means that the inhibitor binds less tightly to the ES complex

α’ is the coefficient telling us by what factor KM and Vmax change during uncompetitive inhibition, and we can define α’ with

α’ = 1 + [I]/K’I

When K’I is low, this causes α’ to be high

The apparent K’M = KM/α’, and the apparent V’max = Vmax/α’, so if α’ is high, both K’M and V’max will decrease by the same rate, thus causing the slow to remain the same

since the y-intercept (b) = 1/V’max, and V’max is decreasing as α’ increases, this causes the y-intercept to increase

![<p></p><p>K’I represents the affinity of the uncompetitive inhibitor for the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) and is given by:</p><p>K’<sub>I </sub>= [ES][I]/[ESI]</p><ul><li><p>a lower K’<sub>I </sub>value means that the inhibitor binds <strong>more tightly</strong> to the ES complex</p></li><li><p>a higher K’<sub>I </sub>value means that the inhibitor binds <strong>less tightly</strong> to the ES complex</p></li><li><p>α’ is the coefficient telling us by what factor KM and Vmax change during uncompetitive inhibition, and we can define α’ with</p></li></ul><p>α’ = 1 + [I]/K’<sub>I</sub></p><ul><li><p>When K’I is low, this causes α’ to be high</p></li><li><p>The apparent K’M = KM/α’, and the apparent V’max = Vmax/α’, so if α’ is high, both K’M and V’max will decrease by the same rate, thus causing the slow to remain the same</p></li><li><p>since the y-intercept (b) = 1/V’max, and V’max is decreasing as α’ increases, this causes the y-intercept to increase</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/8e21eb05-c630-4b83-a302-a5f179fe0613.png)

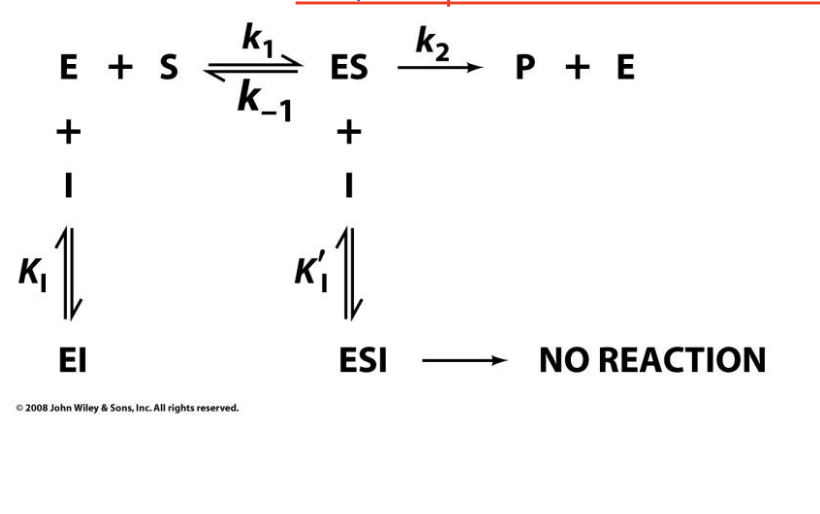

Mixed Inhibition

The inhibitor binds both to the free enzyme (EE) and the enzyme-substrate complex (ESES), but with different affinities.

KM increases or decreases, depending on whether the inhibitor favors E or ES.

Vmax decreases.

Slope increases.

X-intercept shifts (depends on inhibitor preference for E vs. ES).

Y-intercept increases.

Lines intersect but not at the x- or y-intercept.

Explain how Vmax and KM are affected in Mixed Inhibition

Recall how KI and K’I are calculated:

KI = [E][I]/[EI]

K’I = [ES][I]/[ESI]

KI tells us the rate at which the inhibitor binds to the free enzyme

K’I tells us the rate at which the inhibitor binds to the ES complex

From this, we can find α and α’

α = 1 + [I]/KI

α’ = 1 + [I]/K’I

Recall K’M is the apparent Michaelis constant in the presence of an inhibitor, which is given by:

K’M = KM*α/α’

So K’M is directly proportional to α but indirectly proportional to α’ —> dependent on BOTH

If the inhibitor has a greater affinity for free E (lower KI), then α > α’ and K’M will be high

If the inhibitor has a greater affinity for ES complex (lower K’I), then α’ > α and K’M will be low

This means that K’M can increase or decrease depending on the reaction!

Recall V’max is the apparent maximum rate of the reaction in the presence of an inhibitor, which is given by:

V’max = Vmax/α

Note that Vmax is ONLY dependent on α

If α is high, then V’max will be low

Recall y-int = α’/V’max, so if V’max is low then the y-int will be high, also as [I] increases α’ will increase too, causing the y-int to increase as well —> this is why the y-int is ALWAYS increasing!

Slope

Defined as K’M/V’max

Since K’M = K’M*α/α’ and V’max = Vmax/α, we can do some math and redefine slope as αKM/Vmax

If α is high (α > α’), the inhibitor prefers the free E and the slope will increase

If α is low (α’ > α), the inhibitor prefers the ES complex and the slope will decrease

What Happens to the Intersection Point?

If slope increases, lines intersect left of the y-axis.

If slope decreases, lines intersect right of the y-axis.

If slope remains constant, lines intersect at the x-axis.

![<p>Recall how KI and K’I are calculated:</p><p>KI = [E][I]/[EI]</p><p>K’I = [ES][I]/[ESI]</p><ul><li><p>KI tells us the rate at which the inhibitor binds to the free enzyme</p></li><li><p>K’I tells us the rate at which the inhibitor binds to the ES complex</p></li></ul><p>From this, we can find <span>α and α’</span></p><p><span>α = 1 + [I]/KI</span></p><p><span>α’ = 1 + [I]/K’I</span></p><p><span>Recall K’M is the apparent Michaelis constant in the presence of an inhibitor, which is given by:</span></p><p><span>K’M = KM*</span>α/α’</p><ul><li><p>So K’M is directly proportional to α but indirectly proportional to α’ —> dependent on BOTH</p></li><li><p>If the inhibitor has a greater affinity for free E (lower KI), then α > α’ and K’M will be high</p></li><li><p>If the inhibitor has a greater affinity for ES complex (lower K’I), then α’ > α and K’M will be low</p></li><li><p>This means that K’M can increase or decrease depending on the reaction!</p></li></ul><p>Recall V’max is the apparent maximum rate of the reaction in the presence of an inhibitor, which is given by:</p><p>V’max = Vmax/α</p><ul><li><p>Note that Vmax is ONLY dependent on α</p></li><li><p>If α is high, then V’max will be low</p></li><li><p>Recall y-int = α’/V’max, so if V’max is low then the y-int will be high, also as [I] increases α’ will increase too, causing the y-int to increase as well —> this is why the y-int is ALWAYS increasing!</p></li></ul><p>Slope</p><ul><li><p>Defined as K’M/V’max </p></li><li><p>Since K’M = K’M*α/α’ and V’max = Vmax/α, we can do some math and redefine slope as αKM/Vmax</p></li><li><p>If α is high (α > α’), the inhibitor prefers the free E and the slope will increase</p></li><li><p>If α is low (α’ > α), the inhibitor prefers the ES complex and the slope will decrease </p></li></ul><p>What Happens to the Intersection Point?</p><ul><li><p>If <strong>slope increases</strong>, lines intersect left of the y-axis.</p></li><li><p>If <strong>slope decreases</strong>, lines intersect right of the y-axis.</p></li><li><p>If <strong>slope remains constant</strong>, lines intersect at the x-axis.</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/1ecbc454-a1ae-4852-9ebb-74d5bea41e79.png)

Pure Noncompetitive Inhibition

If the enzyme and enzyme–substrate complex bind I with equal affinity, then only Vmax is affected. As with uncompetitive inhibition, substrate binding does not reverse the effects of mixed inhibition. The kinetics of an enzyme inactivator (an irreversible inhibitor) resembles that of a pure noncompetitive inhibitor.

α = α’

What happens to Vmax and KM in Noncompetitive Inhibition?

Since K’M is defined by KM*α/α’, K’M = KM and will not change

V’max is only dependent on α —> V’max = Vmax/α, so V’max will decrease regardless

Since slope is αKM/Vmax = K’M/V’max, slope will always increase even with K’M being constant as V’max is always going to decrease

The y-intercept will still change due to the decrease in Vmax, but the x-intercept will remain the same.

In mixed and uncompetitive inhibition, the inhibitor binds to either the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) or the free enzyme (E), reducing the enzyme's ability to catalyze the reaction at a given concentration of substrate.

x-intercept = α’/αKM, and since α = α’, x-int won’t change

Mixed Inhibition targets…

both free E and ES complex!

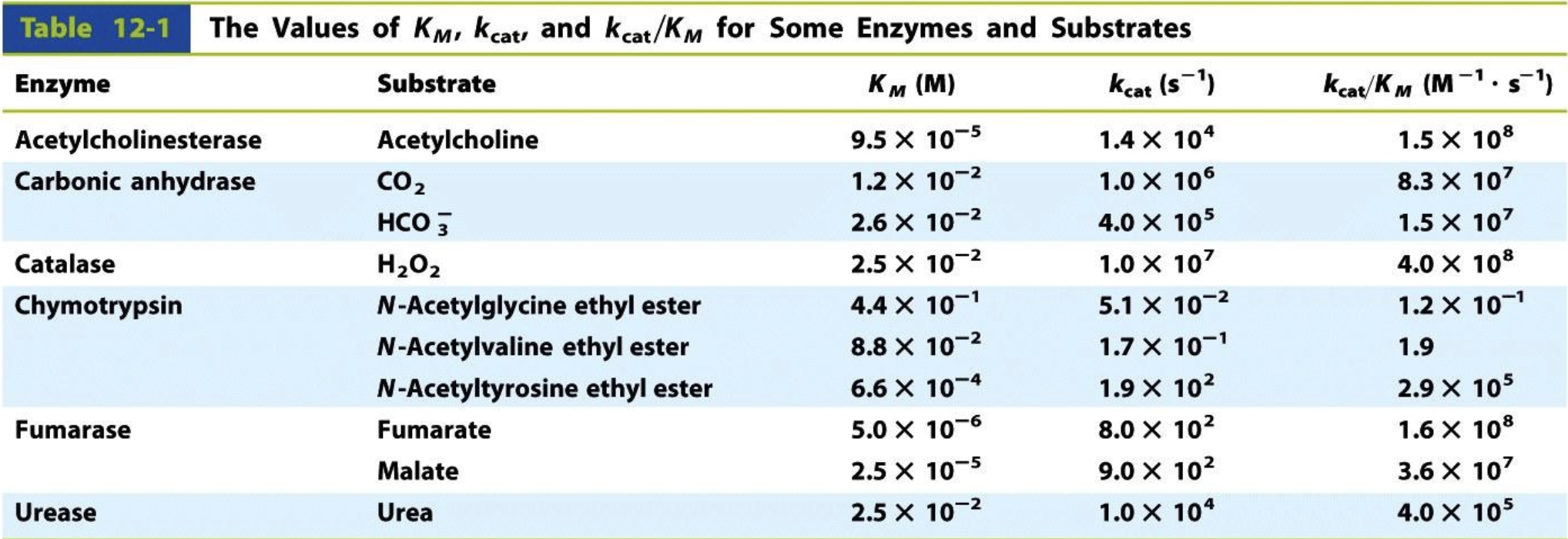

Enzyme Inhibitor Effects Summary

How can we control enzyme reactions?

1.Control of enzyme availability. The amount of a given enzyme in a cell depends on both its rate of synthesis and its rate of degradation. Each of these rates is directly controlled by the cell and is subject to dramatic changes over time spans of minutes (in bacteria) to hours (in higher organisms).

control amount of enzymes (more enzymes = higher reaction rate & vice/versa)

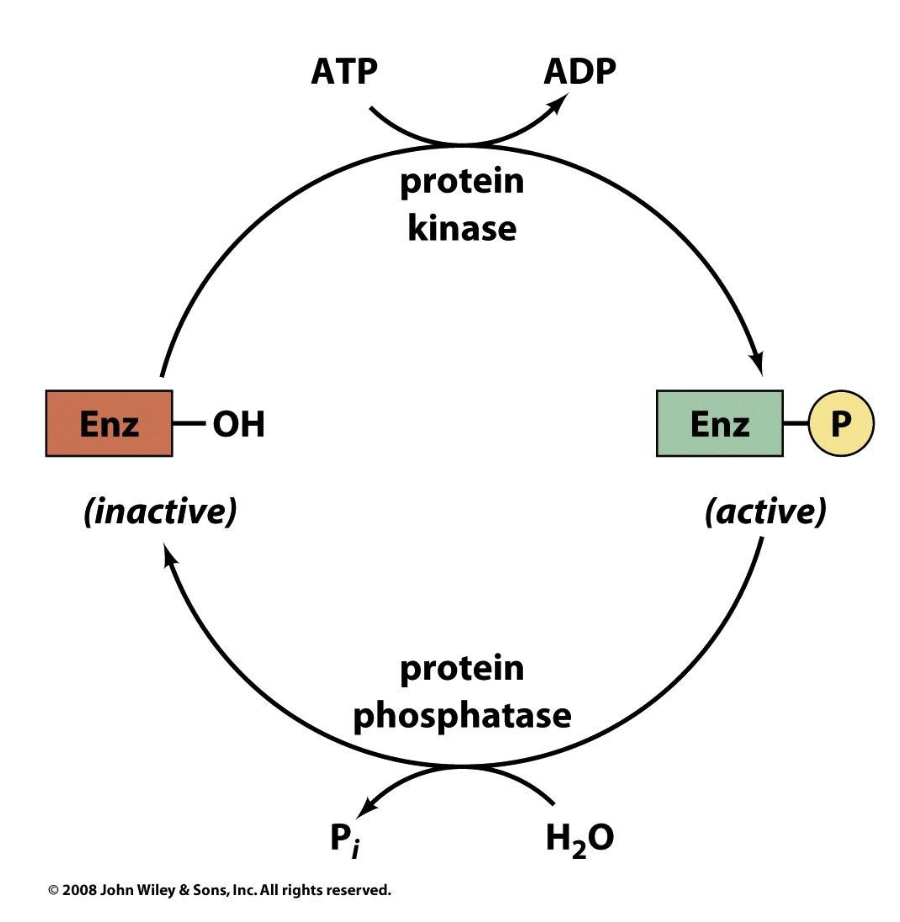

2.Control of enzyme activity. An enzyme's catalytic activity can be directly controlled through structural alterations that influence the enzyme's substrate-binding affinity or turnover number. Allosteric mechanisms can cause large changes in enzymatic activity. The activities of many enzymes are similarly controlled by covalent modification, usually phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of specific Ser, Thr, or T yr residues.

control activity of enzymes (i.e. use inhibitors or enhancers to change what the enzymes do) —> much easier!

What are the two mechanisms to control enzyme activity?

1) allosteric control

2) covalent modification

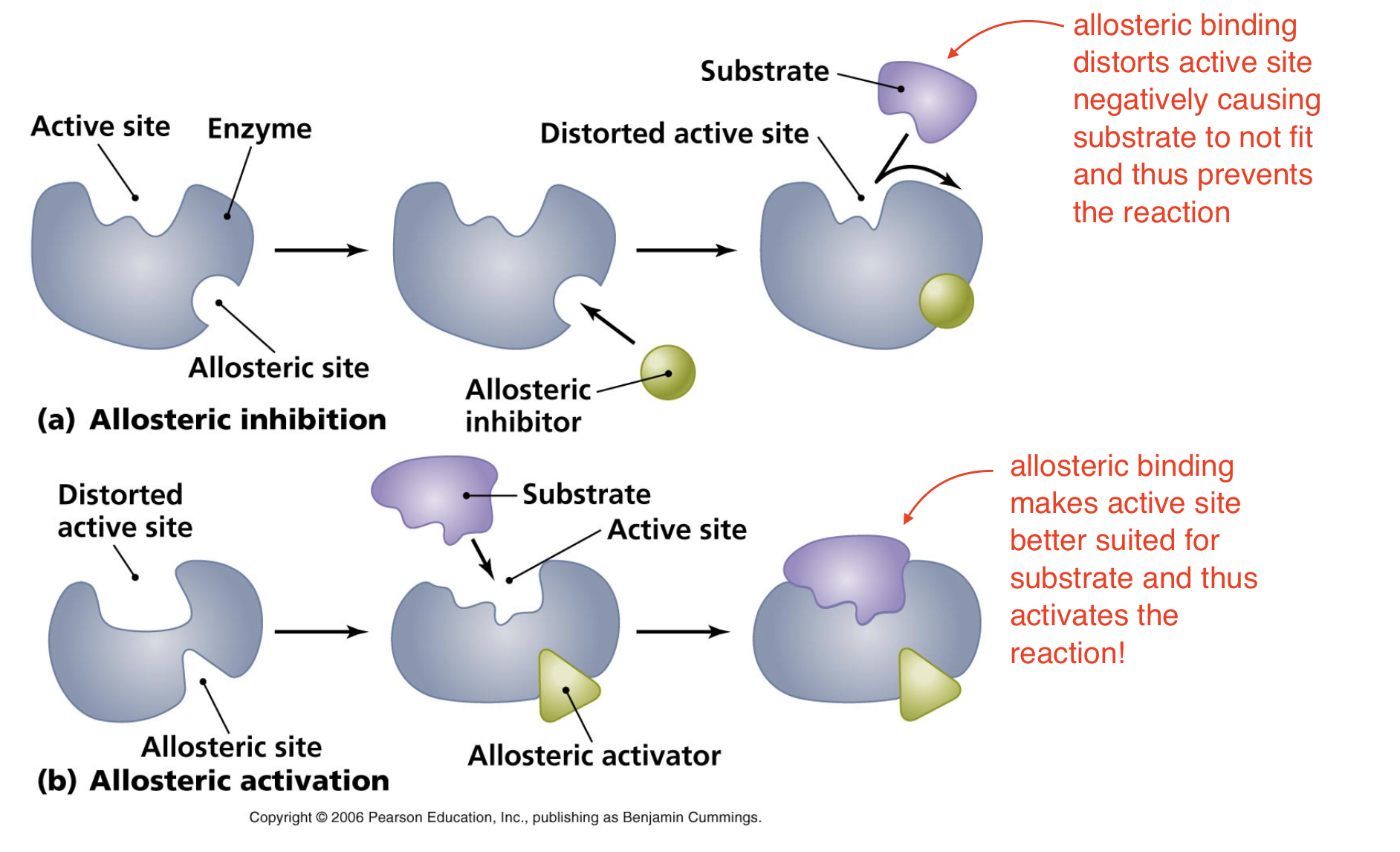

Allosteric Control

Allosteric molecule binds to an allosteric site (site other than active site), this changes conformation of enzyme (remember protein function relies on structure so if we change the structure we distort the function). This can either deactivate or activate the enzyme!

Allosteric Inhibition vs. Activation

Inhibition —> allosteric binding distorts active site negatively causing substrate to not fit and thus prevents the reaction

Activation —> allosteric binding makes active site better suited for substrate and thus activates the reaction!

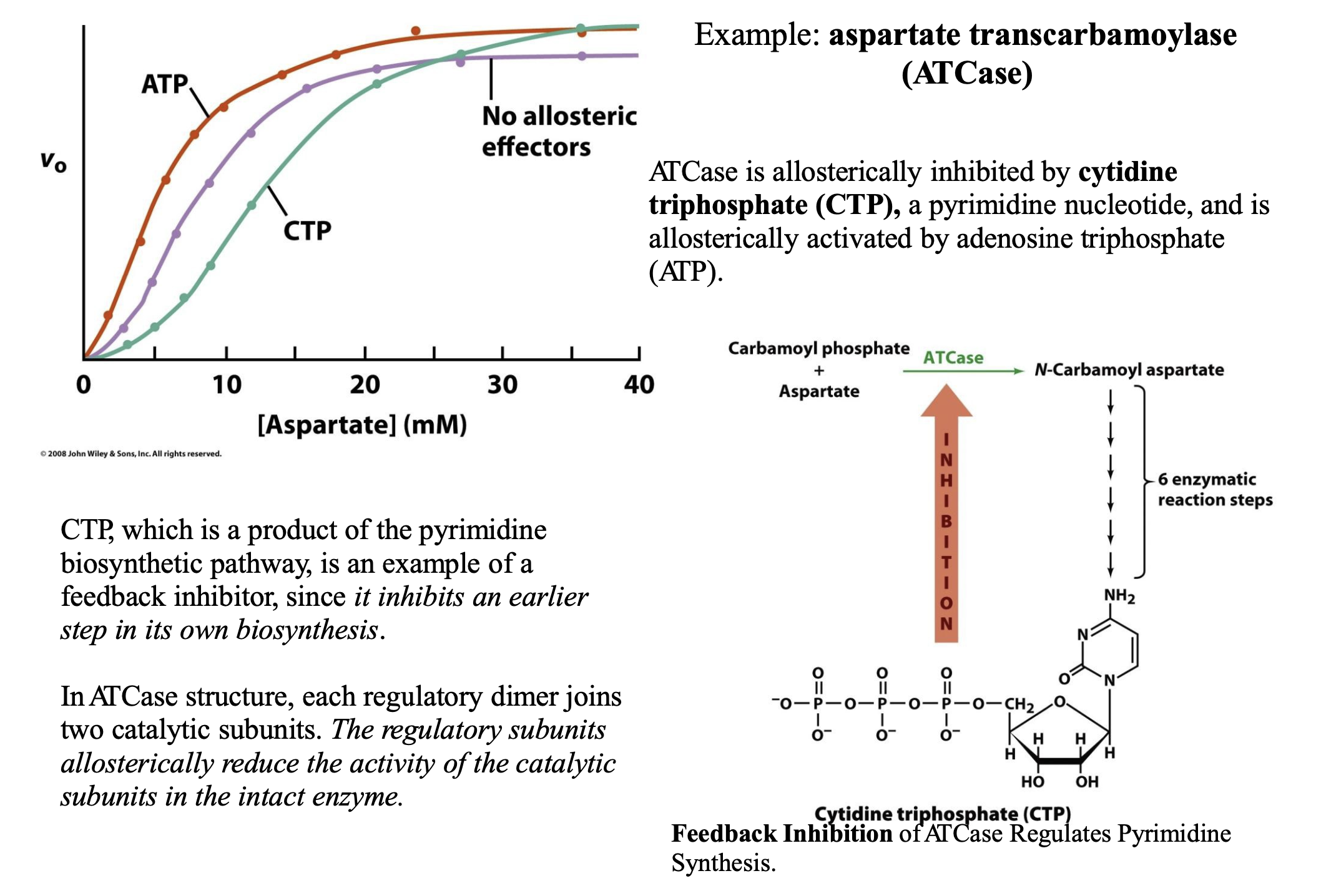

Give an example of Allosteric Control

ATCase is allosterically inhibited by cytidine triphosphate (CTP), a pyrimidine nucleotide, and is allosterically activated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP). CTP, which is a product of the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway, is an example of a feedback inhibitor, since it inhibits an earlier step in its own biosynthesis. In ATCase structure, each regulatory dimer joins two catalytic subunits. The regulatory subunits allosterically reduce the activity of the catalytic subunits in the intact enzyme.

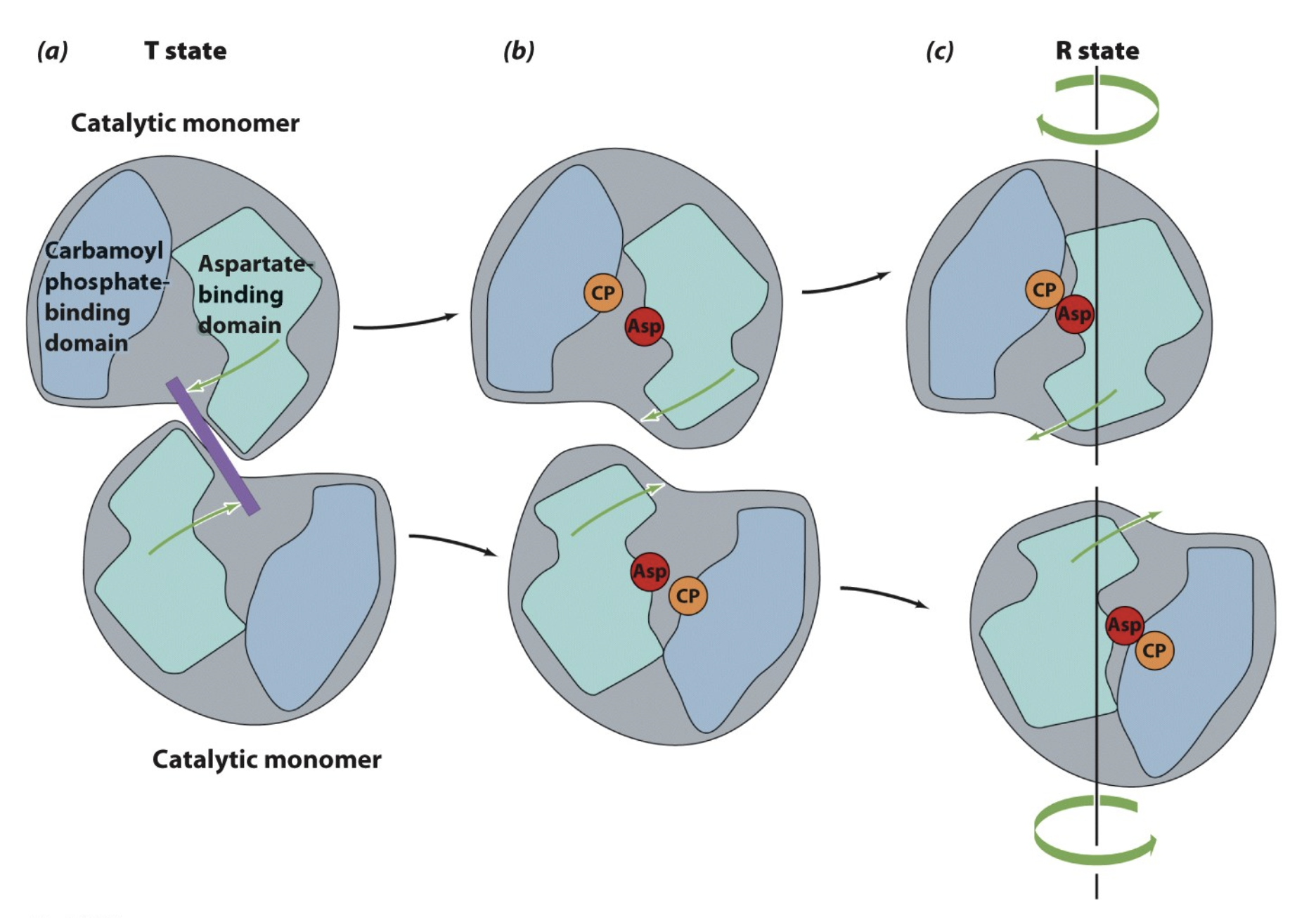

ATCase: Conformational Changes

Control by Covalent Modification

The most common covalent modification is reversible phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (the attachment and removal of a phosphoryl group) of the hydroxyl group of a Ser, Thr, or Tyr residue.

we can add a functional group to the enzyme (most commonly is phosphorylation) —> bulky functional group changes enzyme confirmation and either increases or decreases enzyme activity

works through covalent bonds and thus is called “control by covalent modification”

Example of Control by Covalent Modification

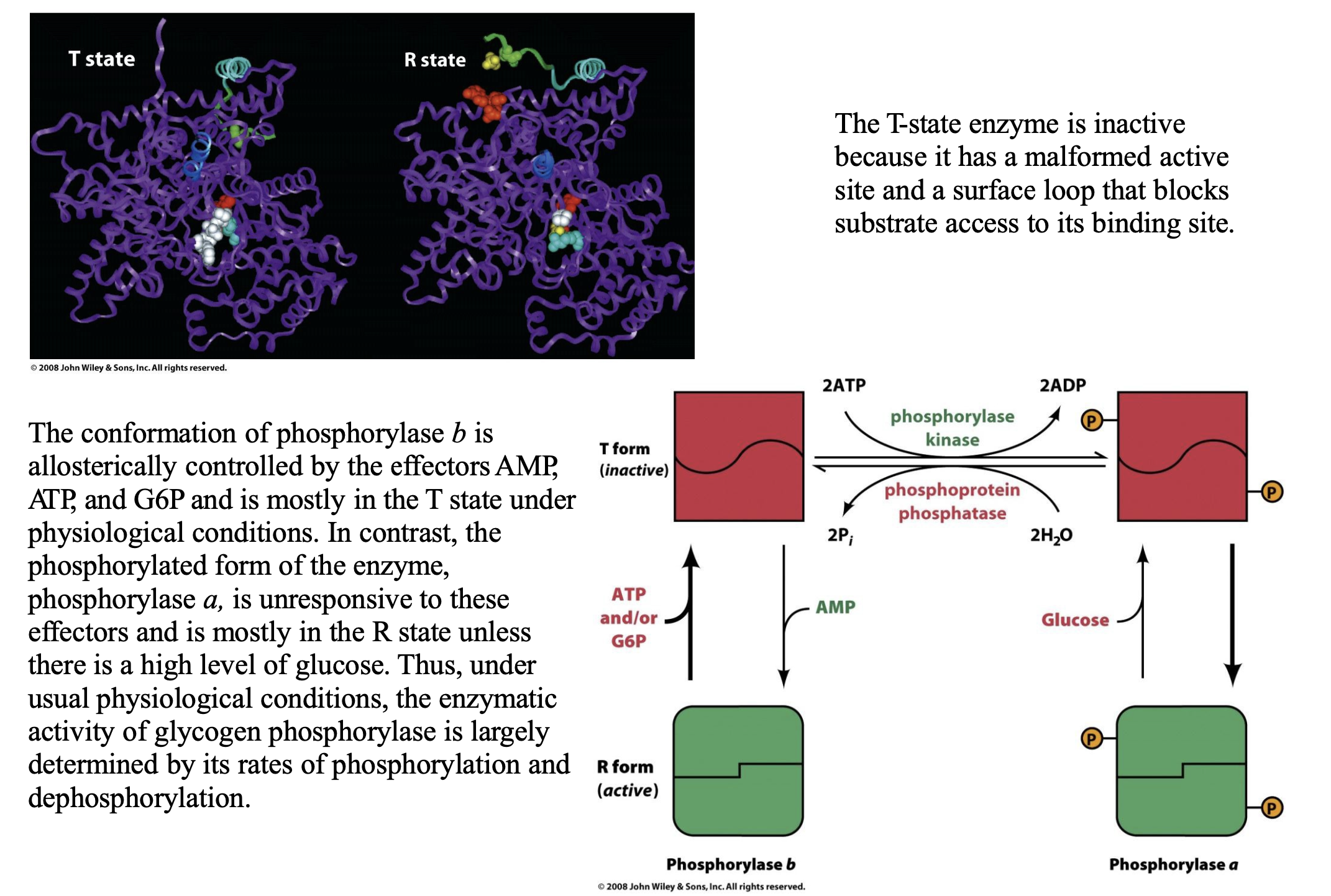

Glycogen phosphorylase which catalyzes the phosphorolysis (bond cleavage by the substitution of a phosphate group) of glycogen to yield glucose-1-phosphate (G1P). This is the rate-controlling step in the metabolic pathway of glycogen breakdown, an important supplier of fuel for metabolic activities. Mammals express three isozymes (catalytically and structurally similar but genetically distinct enzymes from the same organism; also called isoforms) of glycogen phosphorylase, those from muscle, brain, and liver. Muscle glycogen phosphorylase is regulated both by allosteric interactions and by phosphorylation/ dephosphorylation. The phosphorylated form of the enzyme, phosphorylase a, has a phosphoryl group esterified to its Ser 14. The dephospho form is called phosphorylase b.

Explain the conformational change that takes place in glycogen phosphorylase

Glycogen phosphorylase exists in two structural conformations that control its activity:

T (Tense) State = Inactive

The active site is malformed (not properly structured to bind glycogen).

A surface loop blocks the substrate binding site, preventing glycogen breakdown.

This is the default state of phosphorylase b (unphosphorylated form).

R (Relaxed) State = Active

The enzyme undergoes a structural shift, making the active site fully functional.

The substrate binding site is open, allowing glycogen breakdown.

This is the preferred state of phosphorylase a (phosphorylated form).

Phosphorylation of Ser 14: How It Affects Conformation

When Ser 14 is phosphorylated, phosphorylase undergoes a T → R transition.

This phosphorylation acts similarly to allosteric control, shifting the enzyme toward its active (R) state.

The phosphorylated enzyme, phosphorylase a, is mostly in the R state and is not regulated by allosteric effectors like AMP, ATP, and G6P.

Only high glucose levels can shift phosphorylase a back toward the T state, reducing glycogen breakdown when energy is abundant.

Regulation of Phosphorylase b by Allosteric Effectors

Phosphorylase b (unphosphorylated) is mostly in the T state under physiological conditions.

It is regulated allosterically by:

AMP → Activates by promoting T → R transition (signals low energy, so glycogen breakdown is needed).

ATP & G6P → Inhibit by stabilizing the T state (signals high energy, so glycogen breakdown is not needed).

In contrast, phosphorylase a (phosphorylated form) ignores these allosteric effectors, meaning it remains mostly active regardless of AMP/ATP levels.

A drug candidate that exhibits a desired effect is called a _________. A good one _____________ with a dissociation constant (for an enzyme, an _________) of _________. Such a _________ is necessary to _____________ and to ensure that ______________.

Even ________ to a drug candidate can result in ____________________. Thus, substitution of ___________________ at various places on a _________ may _____________. For most drugs used today, ______________ related compounds were typically synthesized and tested. Structure-based drug design (also called ___________) uses the ___________ with a _________ to ______________.

The bioavailability of a drug (i.e. the ________________) depends on both ________________. The most effective drugs are usually a ___________, they are _______________. In addition, their pK values are usually in the range ________ to permit them to ________________ and to __________________.

P450 enzyme _______________ by converting them into a _______________, which aids in their ____________. Drug-drug interactions are often mediated by ______________. For example …

lead compound; binds to its target protein; inhibition constant; less than 1 µM; high affinity; minimize a drug's less specific binding to other macromolecules in the body; that only low doses of the drug need be taken.

minor modifications; major changes in its pharmacological properties; methyl, chloro, hydroxyl, or benzyl groups; lead compound; improve its action; 5000 to 10,000; rational drug design; structure of a receptor or enzyme in complex; drug candidate; guide the development of more efficacious compounds.

the extent to which it reaches its site of action; the dose given and its pharmacokinetics; compromise; neither too lipophilic nor too hydrophilic; 6 to 8; cross cell membranes in their unionized form; bind to their target protein in their ionized form.

detoxify xenobiotics; more water-soluble form; excretion by the kidneys; cytochromes P450

For example, if drug A is metabolized by or otherwise inhibits a P450 isozyme that metabolizes drug B, then coadministering drugs A and B will cause the bioavailability of drug B to increase above the value it would have had if it alone had been administered.