Ch 12 - Food and Water Safety and Food Technology

1/4

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

5 Terms

Intro

Consumers in the United States enjoy food supplies ranking among the safest in the

world. They are also among the most abundant and the most pleasing. Along with

this abundance comes a consumer responsibility to distinguish between choices leading to food safety and those that pose a hazard.

As human populations grow and food supplies become more global, new food-safety

challenges arise that require new processes, new technologies, and greater cooperation

to solve. Food safety is therefore a moving target. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the major agency charged with ensuring that the U.S. food supply is safe,

wholesome, sanitary, and properly labeled. It focuses much effort on these areas of concern:

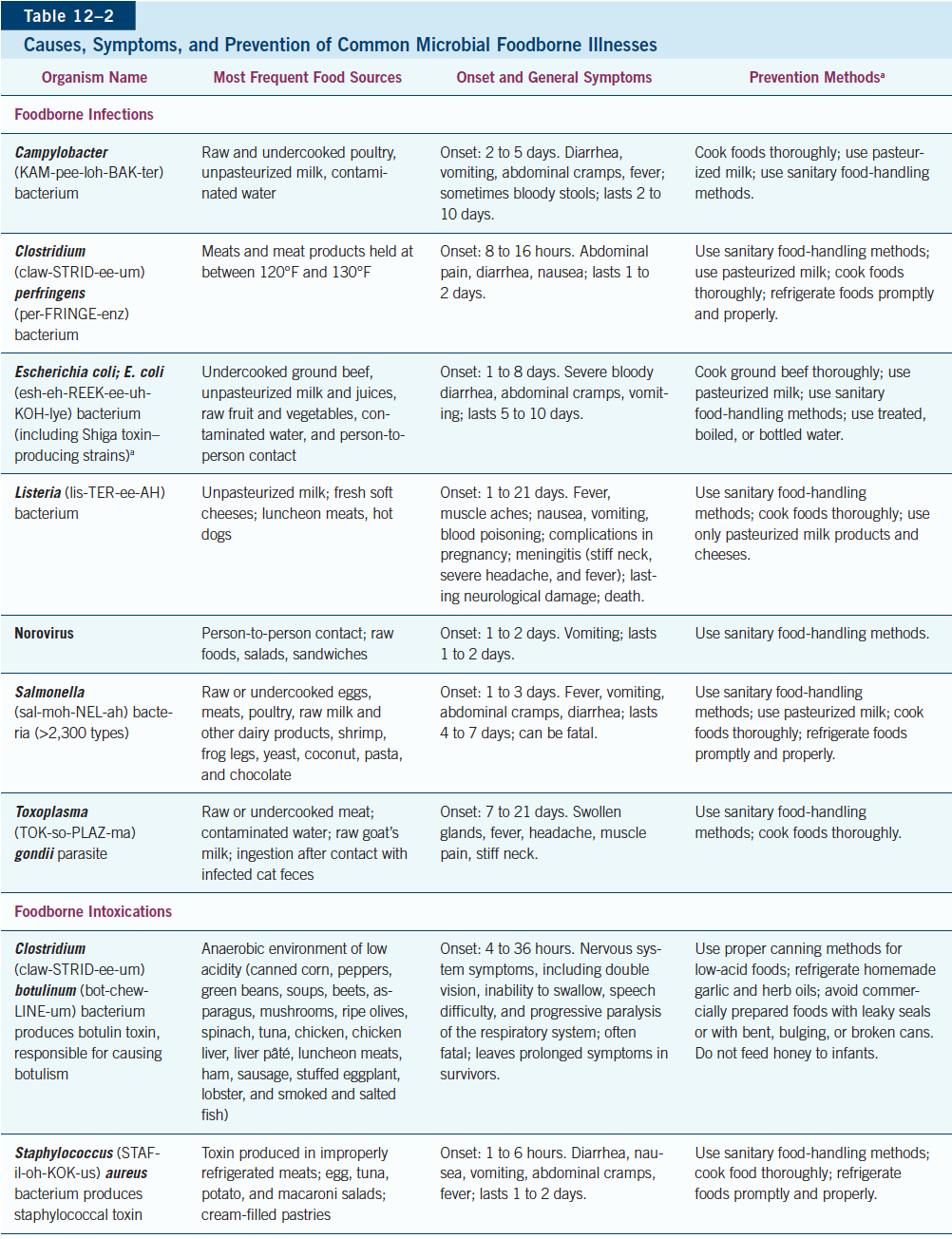

1. Microbial foodborne illness. Each year, 48 million Americans (one in every six)

becomes ill, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die from foodborne illnesses.

2. Natural toxins in foods. These constitute a hazard mostly when people consume

large quantities of single foods either by choice (fad diets) or by necessity (poverty).

3. Residues in food.

a. Environmental and other contaminants (other than pesticides). Household

and industrial chemicals are increasing yearly in number and

concentration, and their impacts are hard to foresee and to forestall.

b. Pesticide residues. A subclass of environmental contaminants, these

are listed separately because they are applied intentionally to foods

and, in theory, can be controlled.

c. Animal drugs. These include hormones and antibiotics that increase

growth or milk production and combat diseases in food animals.

4. Nutrients in foods. These require close attention as more and more highly

processed and artificially constituted foods appear on the market.

5. Intentional approved food additives. These are of less concern because so

much is known about them that they pose little risk to consumers.

6. Genetically engineered foods. Such foods are listed last because they undergo rigorous

scrutiny before going to market.

Within its powers, the FDA is vigilant in overseeing the food supply at home and abroad

to safeguard the health of U.S. consumers. When foodborne illness occurs, the FDA

acts quickly to identify and resolve the cause.

Despite the best efforts of the FDA and others, foodborne illnesses are extraordinarily

likely to occur and the burden of illness is increasing. It seems that as one organism

comes under control, others emerge to take its place. Achieving the ultimate goal—

fewer total foodborne illnesses—requires ever-increasing vigilance on the part of regulators,

food industries, and consumers.

Microbes and Food Safety

Some people brush off the threat from foodborne illnesses as less likely and less serious

than the threat of flu, but they are misinformed. Foodborne illnesses, caused by

disease-causing microbes (pathogens), pose real threats to health and life, and some

increasingly do not respond to standard antibiotic drug therapy. Even normally mild

foodborne illnesses can be lethal for a person who is ill or malnourished; has a compromised

immune system; lives in an institution; has liver or stomach illnesses; or is

pregnant, very old, or very young.

If digestive tract disturbances are the major or only symptoms of your next bout of

what some people dismiss as a “stomach bug,” chances are that what you really have

is a foodborne illness. By learning something about these illnesses and taking a few

preventive steps, you can maximize your chances of staying well. Understanding the

nature of the microbes responsible is the first step toward defeating them.

How Do Microbes in Food Cause Illness in the Body?

Microorganisms can cause foodborne illness either by infection or by intoxication.

Infectious agents, such as Salmonella bacteria or hepatitis viruses, infect the tissues

of the human body and multiply there, causing illness. Some bacteria produce

enterotoxins or neurotoxins, poisonous chemicals that they release as they multiply.

These toxins are absorbed into the tissues and cause various kinds of harm, ranging

from mild stomach pain and headache to paralysis and death.

The most common cause of food intoxication is the Staphylococcus aureus bacterium,

but the most infamous is undoubtedly Clostridium botulinum, an organism that produces

a toxin so deadly that an amount as tiny as a single grain of salt can kill several people

within an hour. Clostridium botulinum grows in anaerobic conditions such as those

found in improperly canned (especially home-canned) low-acid foods, home-fermented

foods such as tofu, and homemade garlic or herb-infused oils stored at room temperature.

Botulism quickly paralyzes muscles, making seeing, speaking, swallowing, and

breathing difficult and demands immediate medical attention.

The botulinum toxin and a few others are heat sensitive and can be destroyed by

boiling, but this is not recommended because poisoning could occur if even a trace of

the toxin remained intact. Other toxins, such as that from Staphylococcus aureus, are

heat-resistant and so remain hazardous even after the food is cooked.

Each year in the United States, tens of millions of people suffer mild to lifethreatening foodborne illnesses, despite efforts of governmental agencies to prevent them.

Pregnant women, infants, toddlers, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems are most vulnerable to harm from foodborne illnesses.

Foodborne illnesses arise from microbial infections or bacterial toxins.

Food Safety from Farm to Plate

A safe food supply depends on safe food practices on the farm or at sea; in processing

plants; during transportation; and in supermarkets, institutions, and restaurants. Equally critical in the chain of food safety, however, is the final handling

of food by people who purchase it and consume it at home. Tens of millions of people

needlessly suffer preventable foodborne illnesses each year because they make their

own mistakes in purchasing, storing, or preparing their food.

How Outbreaks Occur

Commercially prepared food is usually safe, but an outbreak

of illness from this source often makes the headlines because outbreaks can affect many

people at once. Dairy farmers, for example, rely on pasteurization, a process that

heats milk to kill most pathogens, thereby making the milk safe to consume. When a

major dairy develops a flaw in its pasteurization system, hundreds of cases of illness can occur as a result.

Other types of farming require other safeguards. Growing food usually involves soil,

and soil contains abundant bacterial colonies that can contaminate food. Animal waste

deposited onto soil may introduce pathogens. Additionally, farm workers and other food

handlers who are ill can easily pass pathogens to consumers through the routine handling

of fruit, vegetables, or grains during and after harvest, a particular concern with

regard to foods consumed raw, such as lettuce or cucumbers.

Attention on E. coli

Several strains of the E. coli bacterium produce a particularly

dangerous protein known as Shiga toxin, a cause of severe disease. The most notorious

strain, E. coli O157:H7, caused a widespread outbreak in 2021 when consumers across

five states ate contaminated produce, but outbreaks can also arise from other strains of

Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC).* Outbreaks of severe or fatal STEC illnesses focus

national attention on two important issues: first, that raw foods routinely contain live

pathogens and, second, that strict industry controls are essential to make foods safe.

In most cases, STEC disease involves bloody diarrhea, severe intestinal cramps, and

dehydration starting a few days after eating tainted meat, raw milk, or contaminated

fresh raw produce. In the worst cases, hemolytic-uremic syndrome causes a dangerous

failure of the kidneys and organ systems that very young, very old, or otherwise

vulnerable people may not survive. Antibiotics and self-prescribed antidiarrheal medicines

can make the condition worse because they increase absorption and retention of

the toxin. Severe cases require hospitalization.

FDA Food Safety Modernization Act

The FDA Food Safety Modernization

Act (FSMA) aims to lower stubbornly high rates of foodborne illnesses in an increasingly

complex food system. It fosters technologies that enhance microbe traceability to help uncover sources of contamination and speed FDA’s response to an outbreak.

Another important goal is to establish a food safety culture in which safeguarding the

nation’s food supply is everyone’s concern.

Food Industry Controls

Inspections of U.S. meat-processing plants, performed

every day by USDA inspectors, help to ensure that these facilities meet government

standards. Other food facilities are inspected less often, but FSMA regulations require

that all producers of food sold in the United States must employ a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan to help prevent foodborne illnesses at their

source. Each slaughterhouse, producer, packer, distributor, and transporter of susceptible

foods must identify “critical control points” in its procedures that pose a risk of

food contamination or bacterial growth. Once a control point is identified, the food producer must devise and

implement verifiable ways to eliminate or minimize the risk.

The HACCP system is a proven method of controlling microbial contamination, and

its effectiveness is evident: Salmonella contamination of U.S. poultry, eggs, ground beef,

and pork has been greatly reduced, and E. coli infection from meats has dropped dramatically

since HACCP plans were implemented in these industries.

Grocery Safety for Consumers

Canned and packaged foods sold in grocery

stores are generally safe, but accidents do happen, and foods can become contaminated.

FDA scientists track outbreaks of illnesses due to large-scale contamination

and trace both likely production sources and distribution paths to prevent or minimize

consumer exposure. When food contamination is suspected, batch numbering

facilitates the food’s recall through public announcements in the media and other means.

You can help protect yourself, too. Shop at stores that look and smell clean.

Check the freshness dates printed on many food packages, and choose the freshest

ones. “Sell by” and other dates do not reflect a food’s safety, however

(baby formula is the exception: its dates are legally defined). Instead, they indicate

the time of the food’s best quality, and are intended to help retailers manage their

inventories. For consumers, applying these dates too strictly can lead to unnecessary food waste.

If a can or package is bulging, leaking, ragged, soiled, or punctured, don’t buy it—

turn it in to the store manager. A badly dented can or a mangled package is useless in

protecting food from microorganisms, insects, or other spoilage. Many jars have safety

“buttons” on the lid, designed to pop up once the jar is opened; make sure that they

have not “popped.” Frozen foods should be solidly frozen, and those in chest-type freezer

cases should be stored below the frost line. Check fresh eggs and reject cracked ones.

Finally, shop for frozen and refrigerated foods and fresh meats last, just before leaving the store.

Farm-to-plate food safety requires that farmers, processors, transporters, retailers, and consumers use effective food safety methods to prevent foodborne illnesses.

Bacteria multiply quickly when conditions are favorable to them.

FSMA is a law enacted to protect the U.S. food and pet food supplies.

Consumers should carefully inspect foods before purchasing them.

Safe Food Practices for Individuals

Staying mindful of food safety can prevent much misery from intestinal illnesses. Be aware that food can provide ideal conditions for bacteria to multiply and to produce toxins. Bacteria, particularly pathogens, require these three conditions to thrive:

Nutrients

Moisture

Warmth, 40°F to 140°F (4°C to 60°C)*

To defeat bacteria, you must prevent them from contaminating food or deprive them of one of these conditions.

Any food with an “off” appearance or odor should be thrown away, of course, and

not even tasted. However, you cannot rely on your senses of smell, taste, and sight to

warn you because most hazards are not detectable by odor, taste, or appearance. As the

old saying goes, “When in doubt, throw it out.”

Keep Clean

Keeping your hands and surfaces clean requires using freshly washed

utensils and new or disinfected towels and washing your hands properly, not just rinsing

them, particularly before and after handling raw foods. Normal, healthy skin is

covered with bacteria, some of which may cause foodborne illness when deposited on

moist, nutrient-rich food and allowed to multiply. Remember

to use a nail brush to clean under your fingernails when washing your hands and tend to routine nail care—artificial nails, long nails, chipped polish, and even a hangnail harbor more bacteria than do natural, clean, short, healthy nails.

For routine cleansing, washing your hands with ordinary soap and water is effective.

Using an alcohol-based hand-sanitizing gel can also provide killing power against

many bacteria and most viruses. Following up a good washing with a sanitizer may provide

an extra measure of protection when someone in the house is ill or when preparing

food for an infant, an elderly person, or someone with a compromised immune system.

If you are ill or have open cuts or sores, stay away from food preparation.

Microbes love to nestle down in small, damp spaces, such as the inner cells of kitchen

sponges or the pores between the fibers of wooden cutting boards. To reduce their

numbers on sponges, surfaces, and utensils, you have four choices, each with benefits and drawbacks:

1. Poison the microbes with highly toxic chemicals such as bleach (one teaspoon

per quart of water). Chlorine kills most organisms. However, chlorine is toxic to

handle, it can ruin clothing, and when washed down household drains into the

water supply, it forms chemicals harmful to people and wildlife.

2. Kill the microbes with heat. Soapy water heated to 140°F kills most harmful organisms

and washes away most others. This method takes effort, though, because

the water must be truly scalding hot, well beyond the temperature of the tap.

3. Use an automatic dishwasher to combine both methods. It washes in water hotter

than hands can tolerate, and most dishwasher detergents contain chlorine.

4. Use a microwave oven to kill microbes on sponges. Place the soaking wet sponge

in a microwave oven, and heat it a minute or two until it is steaming hot (times

vary). Cautions: handle hot sponges with tongs to avoid scalding your hands,

and heat only wet sponges in the microwave oven; dry sponges can catch on fire.

The third and fourth options—washing in a dishwasher and microwaving—kill

virtually all bacteria trapped in sponges, while soaking in a bleach solution misses more

than 10%. Whatever the method, the effect is temporary and bacteria quickly

return. The best action may be to replace kitchen sponges at least weekly, even if they

don’t appear worn. Even better, skip the sponges and use a stack of kitchen dish cloths

that can be tossed in the laundry daily.

Keep Separate

Raw foods, especially meats, eggs, and seafood, are likely to contain

illness-causing bacteria. To prevent bacteria from spreading, keep the raw foods

and their juices away from ready-to-eat foods. (This is called cross-contamination of

foods.) For example, if you take burgers out to the grill on a plate, wash that plate in hot,

soapy water before using it to retrieve the cooked burgers. If you use a cutting board to

cut raw meat, wash the board, the knife, and your hands thoroughly with soap before

handling other foods—and particularly before making a salad or other foods that are

eaten raw. Many cooks keep a separate cutting board just for raw meats.

Cook

Cook foods long enough to reach a safe internal temperature. The USDA

urges consumers to use a food thermometer to test the temperatures of cooked foods

and not to rely on appearance. Place the probe of a food thermometer in the thickest

part of the food, away from bone and gristle, and wash the probe between readings

to prevent transferring bacteria from the uncooked food to the finished product.

After cooking, hot foods must be held at 140°F or higher until served. A temperature

of 140°F on a thermometer feels hot, not just warm. Even well-cooked foods, if handled

improperly prior to serving, can cause illness. Delicious-looking meatballs on a buffet

may harbor bacteria unless they have been kept steaming hot. After the meal, cooked

foods should be refrigerated immediately or within two hours at the maximum (one

hour if room temperature approaches 90°F, or 32°C). If food has been left out longer than this, throw it out.

Chill

Chilling and keeping cold food cold starts when you leave the grocery store. If

you are running errands, make the grocery store your last shop so that perishable items

do not stay in the car too long. (If ice cream begins to melt, it has been too long.) An ice

chest or insulated bag can help keep foods cold during transit. Upon arrival home, load

foods into the refrigerator or freezer immediately. Foods older than this

should be discarded, not consumed.

To ensure safety, thaw frozen meats or poultry in the refrigerator, not at room temperature.

Marinate meats in the refrigerator, too. To thaw a food more quickly, submerge

it in cold (not hot or warm) water in waterproof packaging or use a microwave

to thaw food just before cooking it. Many foods such as individually packaged chicken

breasts, fish fillets, steaks, and prepared meals, can simply be cooked from the frozen

state—just increase the cooking time and use a thermometer to ensure that the food reaches a safe internal temperature.

Chill prepared or cooked foods in shallow containers, not in deep ones. A shallow

container allows quick chilling throughout; deeper containers take too many hours to

chill through to the center, allowing bacteria time to grow.

Cold meats and mixed salads make a convenient buffet, but keep perishable items

safe by placing their containers on ice during serving. This applies to all perishable

foods, including custards, cream pies, and whipped-cream or cream-cheese treats.

Even pumpkin pie, because it contains milk and eggs, should be kept cold.

Foodborne illnesses are common, but the great majority of cases can be prevented.

To protect themselves, consumers should remember these four practices: clean, separate, cook, chill.

Which Foods Are Most Likely to Cause Illness?

Some foods are more likely to harbor illness-causing microbes than others. Foods that

are high in moisture and nutrients and those that are chopped or ground are especially

favorable hosts. Bacteria reproduce rapidly in many protein foods when given the chance.

Pathogens also lodge on produce, it is a threat to take seriously.

Protein Foods

Protein-rich foods require special handling. When produced on an industrial scale, protein

foods are often mingled together, such as in tanks of raw milk, vats of raw eggs, or

masses of ground meats or poultry. Mingling causes problems when a pathogen from a

single source contaminates the whole batch.

Packages of raw meats, for example, bear labels to instruct consumers on meat safety. Meats in the grocery cooler very often contain bacteria

and provide a moist, nutritious environment perfect for microbial growth. Therefore,

people who prepare meat should follow these basic meat-safety rules:

Cook all meat and poultry to the suggested temperatures.

Never defrost meat or poultry at room temperature or in warm water. The

warmed outside layer of raw meat fosters bacterial growth.

Don’t cook large, thick, dense, raw meats or meatloaf in the microwave.

Microwaves leave cool spots that can harbor microbes. Reminder: never prepare

foods that will be eaten raw, such as lettuce or tomatoes, with the same utensils or

on the same cutting board as was used to prepare raw meats, such as hamburgers.

In addition, the FDA warns against washing raw poultry or meat before cooking it to prevent

spattering bacteria-containing droplets onto kitchen surfaces or other foods in the

area. Finally, always remember to wash your hands thoroughly after handling raw meat.

Unrelated to sanitation, a prion disease of cattle and wild game such as deer and elk,

bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), causes a rare but fatal brain disorder

in human beings who consume meat from afflicted animals. U.S. beef industry regulations minimize the risk of contracting BSE from eating beef.

Ground Meats

In addition to the mingling problem mentioned earlier, ground

meat or poultry is handled more than meats left whole, and grinding exposes much

more surface area for bacteria to land on. Experts advise cooking these foods to the

well-done stage. Use a thermometer to test the internal temperature of poultry and

meats, even hamburgers, before declaring them done. Don’t trust appearance alone:

burgers often turn brown and appear cooked before their internal temperature is high

enough to kill harmful bacteria. Figure 12–8 (p. 444) reviews hamburger safety.

Stuffed Poultry

A stuffed turkey or chicken raises special concerns because bacteria

from the bird’s cavity can contaminate the stuffing. During cooking, the center of

the stuffing can stay cool long enough for bacteria to multiply. For safe stuffed poultry,

follow the Fight Bac core principles—clean, separate, cook, and chill. In addition:

Cook any raw meat, poultry, or shellfish before adding it to stuffing.

Mix wet and dry ingredients right before stuffing into the cavity and stuff loosely;

cook immediately afterward in a preheated oven set no lower than 325°F (use an

oven thermometer to make sure).

Use a meat thermometer to test the center of the stuffing. It should reach 165°F.

To repeat: test the stuffing. Even if the poultry meat itself has reached the safe temperature

165°F, the center of the stuffing may be cool enough to harbor live bacteria. Better

yet, bake the stuffing separately.

Raw and Undercooked Eggs

Eating undercooked eggs at home accounts for a

small but significant portion of U.S. Salmonella infections. Bacteria from the intestinal

tracts of hens often contaminate eggs as they are laid, and some bacteria may enter the

eggs themselves. All commercially available eggs are washed and sanitized before packing,

and some are pasteurized in the shell to make them safer. The FDA requires measures

to control Salmonella and other bacteria on major egg-producing poultry farms.

For consumers, egg cartons bear reminders to keep eggs refrigerated,

cook eggs until their yolks are firm, and cook eggcontaining

foods thoroughly before eating them.

What about tempting foods like homemade ice cream, hollandaise

sauce, unbaked cake batter, or raw cookie dough that

contain raw or undercooked eggs? Healthy adults can enjoy

them if they are made safer by using pasteurized eggs or liquid

egg products instead of regular eggs. However, even these

products, because they are made from raw eggs, may contain

a few live bacteria that survived pasteurization, making them

unsafe for pregnant women, the elderly, young children, or

people with weakened immunity.

Seafood

Properly cooked fish and other seafood sold in the

United States are safe from microbial threats. However, even

the freshest, most appealing, raw or partly cooked seafood can

harbor pathogenic viruses; parasites, such as worms and flukes;

and bacteria that cause illnesses ranging from stomach cramps

to severe, life-threatening conditions.

The dangers posed by seafood are increasing. As burgeoning

human populations along the world’s shorelines release

more contaminants into lakes, rivers, and oceans, the seafood

living there becomes less safe to consume. Viruses that cause human diseases have

been detected in some 90 percent of the waters off the U.S. coast and easily contaminate

filter feeders such as clams and oysters. Government agencies monitor commercial fishing

areas and close unsafe waters to harvesters, but illegal harvesting is common.

As for sushi or “seared” partially raw fish, even a master chef cannot detect microbial

dangers that may lurk within. The marketing term “sushi grade,” often applied to seafood

to imply wholesomeness, means only that the fish was frozen to below zero temperatures

for long enough to kill off adult parasitic worms. Freezing does not make raw fish entirely

safe to eat. Only cooking can kill all worm eggs, bacteria, and other microorganisms. Safe

sushi is made from properly acidified rice (the vinegar reduces pH and thereby retards

bacterial growth), cooked seafood, seaweed, vegetables, avocados, and other safe delicacies,

and then is held at cold temperatures until it is consumed. Experts unanimously

agree that today’s high levels of microbial contamination make eating raw or lightly

cooked seafood too risky, even for healthy adults.

Raw Milk Products

Unpasteurized raw milk and raw milk products (often sold

as “health food”) cause the majority of dairy-related illness outbreaks. The bacterial

counts of raw milk are unpredictable and even organic raw milk from a trusted dairy

can cause severe illness. Drinking raw milk presents a real risk with no advantages—

the nutrients in pasteurized milk and raw milk are identical.

Even in pasteurized milk, a few bacteria may survive, so milk must be refrigerated to

hold bacterial growth to a minimum. Shelf-stable milk, often sold in boxes, is sterilized by

an ultra-high temperature treatment and so needs no refrigeration until it is opened.

Raw meats and poultry pose special microbial threats and so require special handling.

Consuming raw eggs, milk, or seafood is risky.

Raw Produce

The Dietary Guidelines urge people to eat enough fruit and vegetables, but if consumers

eat these foods raw, they must take steps to avoid foodborne illnesses. Foods such

as lettuce, salad spinach, tomatoes, melons, berries, herbs, and scallions grow close to

the ground, making them vulnerable to bacterial contamination from the soil, animal

waste runoff, and manure fertilizers. Contamination often arises when growers and

producers make sanitation mistakes. For this reason, the FSMA law described earlier

includes a Produce Safety Rule, which regulates growing and working conditions on

farms, and requires safety plans from both U.S. and international produce suppliers.

Washing produce at home to remove dirt and debris is important, too. However, washing may not entirely remove certain

bacterial strains. These strains—E. coli, among others—exude a sticky, protective

coating that glues microbes to each other and to food surfaces, forming a biofilm

that can survive home rinsing or even industrial washing. Somewhat more effective is

vigorous scrubbing with a vegetable brush to dislodge bacteria; rinsing with vinegar,

which may help cut through biofilm; and removing and discarding the outer leaves

from heads of leafy vegetables, such as cabbage and lettuce, before washing. Vinegar

doesn’t sterilize foods, but it can reduce bacterial populations, and is safe to consume.

Unpasteurized Juices

Unpasteurized or raw juices and ciders pose a special problem.

Juice producers mingle fruit from many different trees and orchards, and any bacteria

introduced into a batch of juice can multiply rapidly in the sugary fluid. Labels of

unpasteurized juices must carry the warning. Especially

infants, children, the elderly, and people with weakened immune systems should never be

given raw or unpasteurized juice products. Refrigerated pasteurized juices, reconstituted

frozen juices, and shelf-stable juices in boxes, cans, or pouches are generally safe.

Sprouts

Sprouts (alfalfa, clover, radish, and others) grow in the same warm, moist,

nutrient-rich conditions that microbes need to thrive. A few bacteria or spores on sprout

seeds can quickly bloom into widespread contamination of the sprouts; both commercial

and homegrown raw sprouts pose this risk. Sprouts are often eaten raw, but the only sure way to make sprouts safe is to cook them. The elderly, young children, pregnant

women, and those with weakened immunity are particularly vulnerable.

Produce causes many foodborne illnesses each year.

Proper washing and refrigeration can reduce risks.

Cooking ensures that sprouts are safe to eat.

Other Foods

Careful handling can reduce microbial threats from other foods, too.

Imported Foods

Today, over half of the fresh fruits, a third of the fresh vegetables,

and 94% of the fish and seafood consumed in the United States are imported

from other countries. This poses an enormous food-safety

challenge—the methods and standards of many thousands of food producers in far-away

countries vary substantially. Cooked, frozen, irradiated, or canned imported foods and

foods from developed areas with effective food-safety policies are generally safe. Concerns

arise, however, about fresh produce, fish, shrimp, and other susceptible foods that originate

in areas where food-safety practices are lax and contagious diseases are endemic.

To greatly reduce these risks, the FDA’s new FSMA rules now require verification

that imported foods have been produced and handled in keeping with U.S. food safety standards. In addition, to help U.S. consumers distinguish between

imported and domestic foods, regulators require certain foods, including fish

and shellfish, perishable items other than beef or pork, and some nuts to bear a

country of origin label specifying where they were produced.

Honey

Honey can contain dormant spores of Clostridium botulinum that, when eaten,

can germinate and begin to grow and produce their deadly botulinum toxin within the

human body. Mature, healthy adults have their own internal defenses against this

threat, but infants under one year of age should never be fed honey.

Picnics and Lunch Bags

Picnics can be fun, and packed lunches are a convenience,

but to keep them safe, do the following:

Choose foods that are safe without refrigeration, such as whole fruit and vegetables,

breads and crackers, shelf-stable foods, and canned spreads, fish and

seafood, and cheeses to open and use on the spot.

Chill lunch bag foods and pack them in a thermal lunch bag with several reusable ice

packs. Food at room temperature in a paper bag may be unsafe to eat by lunchtime.

Choose well-aged cheeses, such as cheddar and Swiss; skip fresh cheeses, such as

cottage cheese and Mexican queso fresco. Aged cheese does well without chilling

for an hour or two; for longer times, carry it on ice in a cooler or thermal lunch bag.

A handy tip: freeze beverages, such as juice boxes or pouches, to replace ice packs in a

thermal bag. As the beverages thaw in the hours before lunch, they keep the foods cold.

Note that individual servings of cheese or cold cuts prepackaged with crackers

and promoted as lunch foods keep well, but they are high in saturated fat and

sodium, and they cost triple the price of the foods purchased separately. Additionally,

their excessive packaging adds to the nation’s waste disposal burden.

Mayonnaise, despite its reputation for easy spoilage, is itself somewhat spoilageresistant

because of its acidity. Mayonnaise mixed with chopped ingredients in pasta,

meat, or vegetable salads, however, spoils readily. The chopped ingredients have extensive

surface areas for bacteria to invade, and cutting boards, hands, and kitchen utensils

used in preparation often harbor bacteria. For safe chopped raw foods, start with

clean chilled ingredients, and then chill the finished product in shallow containers;

keep it chilled before and during serving; and promptly refrigerate any remainder.

Take-Out Foods and Leftovers

Many people rely on take-out foods—rotisserie

chicken, pizza, Chinese dishes, and the like—for parties, picnics, or weeknight suppers.

When buying these foods, food-safety rules apply: hot foods should be steaming hot,

and cold foods should be thoroughly chilled.

Leftovers of all kinds make a convenient later lunch or dinner. However, microbes

on serving utensils and in the air can quickly contaminate freshly cooked foods; for

safety, refrigerate them promptly and reheat them to steaming hot (165°F) before eating.

Discard any portion held at room temperature for longer than 2 hours from the

time it was served at the table until you place it in your refrigerator. Follow the 2, 2, and

4 rules of leftover safety: within 2 hours of cooking, refrigerate the food in clean, shallow

containers about 2 inches deep, and use it up within 4 days or toss it out. Exceptions:

stuffing and gravy must be used within 2 days, and if room temperature reaches

90°F, all cooked foods must be chilled after 1 hour of exposure. Remember to use shallow

containers, not deep ones, for quick chilling.

Consumers bear a responsibility for food safety, and an essential step is to cultivate

awareness that foodborne illness is likely. They must discard old misconceptions that

put them at risk and adopt an attitude of self-defense to prevent illness.

Many foods are imported, and the FDA is working to improve their safety.

Honey should never be fed to infants.

Lunch bags, picnics, and leftovers require safe handling.

Concepts / Terms

Safety

the practical certainty that injury will not result from the use of a product or substance.

Hazard

a state of danger; referring to any circumstance in which harm is possible under normal conditions of use.

Foodborne Illness

illness transmitted to human beings through food or water; caused by an infectious agent (foodborne infection) or a poisonous substance arising from microbial toxins, poisonous chemicals, or other harmful substances (food intoxication). Also commonly called food poisoning.

Intoxication

a state of physical harm caused by a toxin; poisoning.

Botulism

an often fatal foodborne illness caused by the botulinum toxin, a toxin produced by the Clostridium botulinum bacterium, which grows without oxygen in nonacidic canned foods.

Outbreak

two or more cases of a disease arising from an identical organism acquired from a common food source within a limited time frame. Government agencies track and investigate outbreaks of foodborne illnesses, but tens of millions of individual cases go unreported each year.

Pasteurization

the treatment of milk, juices, or eggs with heat sufficient to kill certain pathogenic (disease-causing) microbes commonly transmitted through these foods; not a sterilization process. Pasteurized products retain bacteria that cause spoilage.

HACCP plan (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point)

a systematic plan to identify and correct potential microbial hazards in the manufacturing, distribution, and commercial use of food products. HACCP may be pronounced “HASS-ip.”