topic 9 - prosocial behaviour

1/30

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

31 Terms

prosocial, helping and altruistic behaviour

three key dimensions

intentionality (Batson & Powell, 2003)

prosocial behaviour encompasses actions intended to benefit others

most definitions emphasise that both prosocial and altruistic behaviours reflect positive social actions aimed at promoting the welfare of others

multiple definitions emphasise the intentional nature of prosocial behaviour

costs and benefits (Schroeder & Graziano, 2015)

any action that benefits others

what matter is positive impact - intended or not

altruism - actions incurring cost to actor while benefitting recipient - altruistic behaviour inherently costly

social context

actions valued by society

societal approval

can include actions that do not benefit others but are socially approved

motives in prosocial behaviour

egoistic motives

underlying motivation might be self-serving outcome can still benefit community

social recognition gained may encourage further prosocial behaviour

cycle of positive impact

empathetic motives

when experiencing compassion we are more inclined to engage in acts of kindness

deeply rooted in wanting to alleviate suffering of others and promoting well-being

lead to genuine connections - community support and cohesion

moral values

principal forms of prosocial behaviour

actions guided by commitment of what one thinks is right regardless of personal gain

moral compass not only inspires own actions but can also motivate others to follow suit - ripple effect of positive change

evolutionary perspective on PB

the role of intention

largely irrelevant in evolutionary definitions of altruism - focus on general biological principles

reputation and social dynamics

altruistic behaviours can enhance reputation within social group - increased reproductive success

individuals more likely to engage in PB when they feel/think they are observed

psychological motivations

fitness costs

altruism - actions that benefits others at the cost of oneself

long term evolutionary implications for reproduction and survival

kin selection (Hamilton, 1964)

does not incur costs in the same way altruistic behaviours might be perceived

genetic advantages of aiding relatives - investment in genetic legacy

evolutionary pressures shape actions that appear altruistic but are rooted in genetic self-interest

for many species cooperative actions arise from instinct rather than conscious choice - untypically classified as prosocial in human sense

humans naturally predisposed to help others - need for connection and cooperation

relationships = community and support

increases likelihood of PB

reciprocal helping - norm of reciprocity

encourages individuals to assist one another

enhances trust and collaboration

investing in reciprocal relationships = boost chances of receiving help in return → supportive network

biological basis of helping

identical twins show higher correlation (r = .62) in prosocial behaviour compared to fraternal twins (r = .40) - highlighting genetic influences

how much altruism is inherited vs. learned - identical environment between twins

infant preferences (Hamlin et al., 2007, 2010)

even infants as young as three months prefer helpful over hurtful individuals

preference indicates that foundations of morality may be somewhat innate rather than product of socialisation

toddler altruism (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006)

children as young as two distinguish between accidental and intentional actions in helping

ability to asses intentions reveals sophisticated level of moral reasoning - remarkable for a young age

toddlers are active participants in moral development

altruism may be part of our natural development

learning to be prosocial

parenting practices

positive parenting predicts greater prosocial tendencies, independent of genetic factors (Knafo & Plomin, 2006)

interactions between parents and children can influence inclination to help others

nurturing environments → more likely to develop empathy

learning theory: development of prosocial behaviour in three stages:

helping for self-gain (instrumental rewards)

help others gain something for themselves

helping for social rewards (approval)

begin to understand value of social approval

motivated by desire of social reward

being helpful can lead to positive feedback from others

social context of helping

helping due to internalised values (moral principles)

internalised values and moral principles

help others because they believe it is the right thing to do

helping becomes intrinsic part of identity

interactions + experiences teach us to be altruistic

role of media

engaging with prosocial content increases PB over time

increase mediated by empathy

ability to understand and respond to the emotional state of others

implications - media acts as a "teacher" influencing personality traits and behaviours over time

potential to cultivate empathy and cooperative behaviour

can leverage social media in educational developmental contexts to promote positive social interactions and foster more empathetic societies

social exchange theory - Thibault and Kelley

helping decisions based on cost-benefit analyses

people make decisions by weighing up costs against anticipated reward

nature of altruism - truly selfless or driven by underlying self-interest

willingness to help can fluctuate depending on relative importance of costs and rewards in different contexts/situations

Good Samaritans study

findings:

ill victims helped more frequently (95%) and faster than drunk victims (50%)

higher costs - disgust/potential harm

slight preference for same-race helping, especially for drunk victims

subtle biases

no diffusion of responsibility observed - larger groups facilitated faster help

heightened emotional arousal

delayed help increased bystander discomfort and area exits

passengers more likely to leave critical area during drunk trials or if help was delayed

comments reflected discomfort and rationalising inaction - social dynamics

cost-reward model proposed

bystanders assess cost against rewards when deciding whether to intervene

emotional arousal caused by witnessing an emergency drove behaviour - responses aimed at diminishing the discomfort

complexity of real-life interactions

empathy-altruism hypothesis

key components: empathic concerns and altruistic motivation

feel a deep urge to help someone in distress even when it might cost us something

feelings of empathic concern can illicit genuine altruistic motivations

goal - alleviate suffering rather than achieve self-serving gains

concern focused on welfare on others rather than own distress

prompts us to act in other’s best interests

altruistic motivation - helping behaviour driven by genuine desire to improve well-being of person in need

prioritises need of others above any personal gain

social and emotional triggers of helping pt.1

similarity and prejudice

racial biases affect helping behaviour, especially in high-emergency situations

emergency severity and bias

increased urgency leads to slower response times and reduced help for Black victims, highlighting the impact of aversive racism and arousal-cost-reward models

participants placed in staged emergencies - measured quantity and speed of help to black vs. white victims

findings - as level of emergency increased the speed and quality of help offered by white participants to black victims decreased relative to their help for white victims

white helpers experienced high levels of aversion - directly correlated with slower response times

the more urgent the situation the more pronounced the bias became

white participants often interpreted emergencies involving black victims as less severe - felt less responsible to help

consistent across multiple studies

rationalizing discrimination

helpers are less likely to assist Black victims when they can justify non-helping with non-racial factors, especially in demanding or high-risk situations

more pronounced in higher emergency situations

when ability to control prejudiced responses is inhibited biases can emerge

social and emotional triggers of helping pt.2

empathy gap (Bohns and Flynn, 2015; Arceneaux, 2017)

occurs when people underestimate the pain and suffering of others - reduced empathetic responses

often arises from misunderstanding or misinterpretation of perspectives which can prevent effective cooperation and reduce helping behaviour

especially pronounced when victims seem distant or difference to us

perceived group differences can exacerbate these empathy gaps especially towards out-group members

causal attributions (Betancourt, 1990)

when someone believes an individual is personally responsible for their suffering it can lower feelings of empathy and the likelihood of helping

our beliefs about the causes of suffering can directly influence willingness to help

attribution biases can further hinder empathy - framed suffering as self-inflicted

especially when observer maintains an objective stance rather than an empathetic perspective

emotions (Stocks et al., 2009)

guilt can increase likelihood of helping

communal orientation fosters prosocial tendencies - prioritise need of community and relationship

gratitude (Wilhelm & Bekkers, 2006)

when recipients express gratitude it encourages repeat of helping behaviour

positive feedback loop

strengthens social bonds

priming PB

specific cues and contexts can enhance our inclination to engage in altruistic actions

prosocial behaviour and positive affect reinforce each other (Aknin et al., 2018; Snippe et al., 2018)

positive feedback loop - good mood boost willingness to help others k

priming mortality increase charitable giving (Jonas et al., 2002)

contribute to something larger than themselves - positive legacy

religious values complicate our understanding of prosocial behaviour - religious beliefs can inspire acts of kindness they also influence who we help and why

in-group bias (Saroglou et al., 2005) favouring in-group members

more inclined to help those within their faith community

limit scope of PB

preferential treatment rather than universal commitment to helping

methodological issues

self-reports suggest religious individuals as more prosocial

behavioural and experimental methods give a more nuanced and complex picture → main effects attributed to religious processes can be explained by general psychological factors

contextual factors (e.g. Stavrova & Siegers, 2014)

social reinforcement of religiosity can influence the relationship between religion and PB

2014 study - in countries with low social enforcement religious individuals were more likely to engage in PB

societal context can either enhance or inhibit expression of PB among religious and non-religious individuals

why do people fail to help

diffusion of responsibility hypothesis

presence of multiple bystanders diffuses individual responsibility → when more people are present each person feels less compelled to step in assuming someone else will

inaction also explained by emotional conflict - wanting to help vs. fear of making a mistake

can paralyse decision making in critical moments

presence not characteristics of other bystanders affects response

psychological barriers to others

key studies

Darley and Latané - simulated seizure

Darley and Latané - white smoke

Darley and Batson - religious talking giving

evidence for bystander effect

the bystander effect is strongest in ambiguous or low-danger situations

uncertain about necessity of intervention - diffusion of responsibility

uncertainty translates to inaction → people look to others for how to respond

in high-danger situations, bystanders are more likely to act, as the need for help becomes clearer

immediate bystanders are more likely to act decisively

clear threat distinguished = heightened sense of urgency → can override inhibiting effects typically associated with presence of others

certain factors can mitigate bystander effect

presence of a perpetrator/expectation of physical danger can lead to increased helping behaviour - bystanders may view each other as potential allies → collective responsibility

transform dynamics of situation

implicit bystander effect

Garcia et al. (2002) - demonstrated that merely thinking about being in a group reduced personal accountability and can influence help and behaviours in unrelated tasks

merely imagining presence of others can lead to decreased helping behaviour even when those imagined others cannot assist - activates diffusion of responsibility

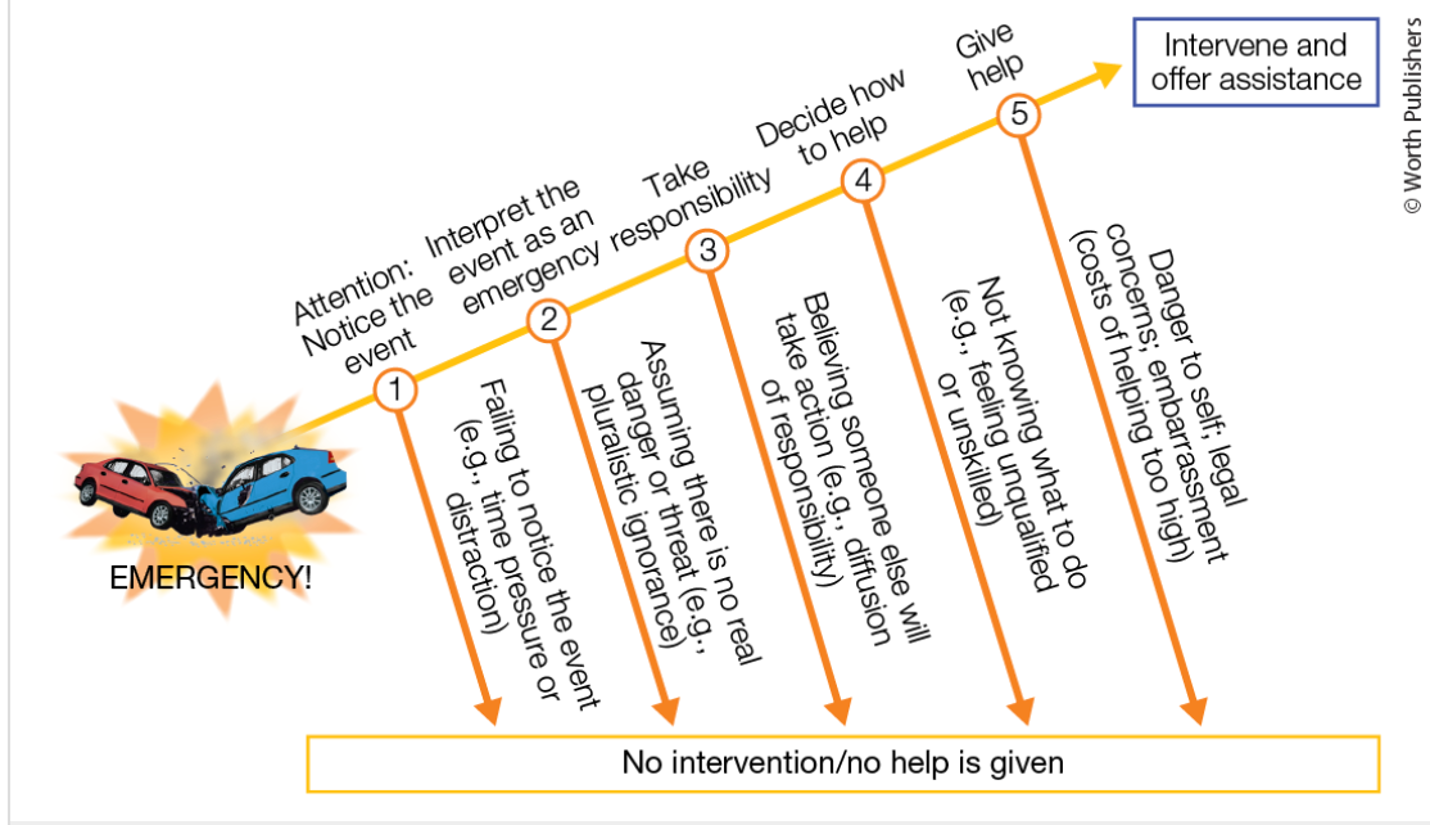

bystander intervention model

social cues can often influence ambiguity of a situation

eg. reactions of others

need to recognise that inaction of others may be because of uncertainty rather than accurate judgment of the situation

high risk situations often reduce intervention unless danger is severe and unambiguous

helping is not an automatic response - must navigate each step

barriers at any stage can prevent intervention

by understanding steps we can develop better strategies to encourage prosocial behaviour and ensure that more people get the help they need

altruistic personality

rationale - while many people engaged in helping behaviours these actions are not always consistent across personalities or situations

sought to clarify whether individual traits indicative of altruistic personality reliably predicted helping behaviour

explore personality-situation interactions to influence helping behaviours

address conflicting findings - altruism in easy to escape scenarios vs. egoistic motivations in hard to escape

altruistic personality is context dependent

dispositional traits and situational characteristics jointly influencing prosocial behaviour

complex interplay between personality and environment

role of agreeableness

agreeableness - empathy, cooperativeness, compassion

thought to underpin individual propensity to engage in altruistic acts

represents broader dispositional framework - may predispose individuals for certain social responses across different situations

agreeableness predicts helping through link to empathic concern which drives motivation for pro-social behaviour

role of intrinsic motivation

the internal drive to engage in activities for their own sake rather than for some external reward pressure

rooted in personal satisfaction, fulfilment and alignment with one’s values and interests

encourages people to help out of genuine concern

intrinsically motivated prosocial behaviour linked with greater wellbeing and deeper connection with those assisted

cycle of positive reinforcement

intrinsic motivation

autonomous motivation for helping enhances well-being for both helpers and recipients by satisfying basic psychological need

self-determination theory

autonomous motivation - genuine care or alignment with values

helpers who act based on intrinsic motivations experience greater vitality, self-esteem and positive affect

recipients perceive help as authentic

stronger and authentic relationship

moral identity centrality drives intrinsic helping behaviours, influenced by situational cues that activate or suppress moral self-concept

intrinsic reasons for helping are deeply-tied to self-concept

strong moral identity - motivated to act in prosocial ways - align with core identity

those with intrinsic motivations for helping are less susceptible to situational factors eg. financial incentives

intrinsic helping behaviour are sustained when resonating with individual sense of moral self

self-giving, donating items symbolic of personal essence, increases perceived generosity of helpers and commitment to causes

donating item of personal significance - stronger sense of connection to act - integrating into self-concept

seen as more valuable

durable connection between helper and cause

increases likelihood of sustained engagement over time

political orientation

religiosity moderates the relationship between political orientation and empathy, showing that empathy differences between liberals and conservatives diminish with higher religiosity

liberals and conservatives rely on different moral foundations (individualizing vs. binding) in making moral judgments, influencing their prosocial behaviours and social policies

liberal more focused on issues of harm and fairness - empathy and justice

conservative value more purity, loyalty and authority - group cohesion and societal order

moral framing (individualizing vs. binding) can shift environmental attitudes and behaviours, with conservatives responding more positively to binding moral frames in pro-environmental messages

conservatives respond more to pro-environmental messages framed in binding moral messages

liberals maintained pro-environmental attitudes regardless of frame

role of gender

self-perceptions vs. behaviours

women report higher empathy and agreeableness, but men often exhibit more helping behaviour in risky, chivalrous, or public contexts (Eagly & Crowley, 1986)

reflects societal expectations

biological influences

women’s "tend-and-befriend" hormonal responses drive affiliative and caregiving prosociality (Taylor, 2006)

behavioural patterns by type

women excel in altruistic, emotional, and compliant behaviours, while men lead in public helping; minimal gender differences in anonymous prosociality (Xiao et al., 2019)

dire prosocial behaviour tend to favour women - overlap with emotional involvement

men encouraged to engage in PB in ways that align with traditional masculine values while women are socialised to be more nurturing and caring

may vary by cultural contexts - smaller gaps in more egalitarian societies

bystander intervention recap

five-step decision model (Latané & Darley, 1970):

notice the event – awareness of the situation

interpret as an emergency – determining if help is needed

assume responsibility – personal accountability for intervention

decide how to help – choosing a course of action

take action – implementing the decision to intervene

key concepts:

diffusion of responsibility: more bystanders reduce individual accountability

ambiguity and pluralistic ignorance: uncertainty leads to reliance on others’ reactions

cost-benefit analysis: potential risks and rewards of intervening

implicit bystander effect (Garcia et al., 2002): thinking about being in a group can reduce personal accountability, even without others being physically present

classic studies:

smoke-filled room experiment (Latané & Darley, 1968)

seizure study (Darley & Latané, 1968)

key contributions

what hinders responsibility and intervention of bystanders

the more people are present the more responsibility is diffused and intervention delayed

relying on other’s reaction in an emergency due to uncertainty

features of online spaces

anonymity: online interactions often allow users to remain anonymous or use pseudonyms

relevance: reduces personal accountability, influencing whether bystanders choose to intervene

asynchronicity: online communication can occur at different times (asynchronous), allowing users to respond at their convenience

relevance: this feature can lead to delays in intervention, as bystanders may feel less urgency to act when they are not witnessing an event in real-time - may reduce urgency of event

group dynamics: online platforms often host large groups of users, creating a collective environment

relevance: the presence of multiple bystanders can lead to the diffusion of responsibility (assume someone else will take action)

cost-benefit interpretation - ambiguity, if no one else responds to a situation you would consider an emergency how justified are you in intervening?

visibility and permanence: Online content can be easily shared, reshared, and archived, making actions and comments visible to a wide audience

relevance: amplifies the impact of bystander actions or inactions, as responses can be scrutinised by others, affecting their willingness to intervene

empowerment when intervening

inaction due avoid trolling/harassment

emotional distance: online interactions can create a sense of detachment from the emotional realities of others

relevance: this emotional distance may lead to a lack of empathy, influencing bystanders' decisions to intervene or support victims

challenges for BI online

notice the event – awareness of the situation

content overload can desensitise users to harmful behaviour

interpret as an emergency – assessing help need

lack of emotional cues = ambiguity in severity assessment

harmful actions often misinterpreted as typical online interactions

harassment/trolling has become extremely common

assume responsibility – personal accountability

anonymity and large group dynamics diffuse responsibility

bystanders often expect others to intervene, reducing personal action

decide how to help – choosing an action

options: reporting, supporting victims, or confronting perpetrators

impact is not as powerful or immediate as a real-life situation

challenge: fear of backlash or platform norms can hinder decisions

take action – implementing the decision

empowerment and platform culture impact intervention likelihood

fear of negative consequences often deters action

bullying

form of interpersonal aggression with three distinct traits (Olweus, 1993)

power imbalance in favour of perpetrators

repetitive nature

direct intention to cause harm or distress

bullying can be physical, verbal, and/or relational

cyber-bullying is on the rise with shared and distinct features highlighted...

anonymity shifts power dynamics

CB repeated via ongoing viewing - visibility and permanence

victims know that content is being viewed over and over

CB can continue outside of school setting/time

department of education (2016): 40% of young people were bullied in the last 12 months

teacher intervention in traditional and cyber bullying

traditional bullying: higher likelihood of teacher intervention compared to cyberbullying

affective empathy: greater empathy increases chances of noticing, interpreting, and acting on bullying

perceived seriousness: teachers viewing bullying as serious are more likely to respond

cyberbullying challenges: teachers feel unprepared, resulting in lower intervention rates

adolescent judgments about bystander intervention online

gender & grade: females and younger students find cyberbullying less acceptable and are more likely to intervene

empathy: higher empathy levels lead to a greater likelihood of active intervention

family dynamics: positive family management and secure attachments correlate with lower acceptability and higher intervention intentions

racial discrimination: experiences of discrimination from teachers linked to higher acceptability of cyberbullying and lower intervention intentions

challenges in responding to SV

diverse forms of sexual violence

partner, acquaintance, stranger SV

sexual violence settings (private v public)

myths about sexual violence

victim blaming

doubt and disbelief

exonerate perpetrators

stereotypes about victims

misconstruction of consent

real rape stereotypes

gendered assumptions

knowing when but also how to intervene

applying bystander model to SV cases

bystander intervention approach:

engages community members to intervene in potential sexual violence situations

focuses on empowering bystanders to act before, during, and after incidents

continuum of bystander opportunities:

reactive situations: interventions during or after an assault

proactive situations: actions taken to prevent sexual violence before it occurs

risk levels: classifies situations as high-risk (imminent danger) or low-risk (subtle behaviors supporting a culture of violence)

importance of education