Signal Transduction

1/5

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

6 Terms

Describe in molecular terms the cAMP cascade resulting when a given hormone binds to the beta- adrenergic receptor, including all regulatory steps of this cascade.

Explain how caffeine stimulates cAMP levels in target cells.

Explain how Bordetella pertussis and Vibrio cholarae toxins affect the action of G proteins.

Explain the mechanism of action of insulin, insulin-like hormones and growth factors.

Describe in molecular terms the cAMP cascade resulting when a given hormone binds to the beta- adrenergic receptor, including all regulatory steps of this cascade.

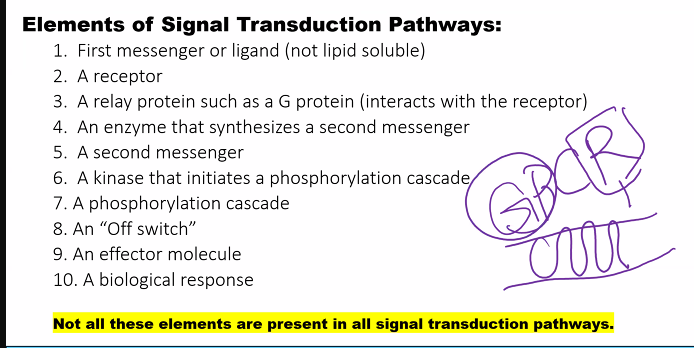

The cAMP cascade initiated by a hormone (like adrenaline) binding to the β-adrenergic receptor is a classic example of signal transduction and amplification. Here is a detailed description of the process in molecular terms, including all key regulatory steps.

Overview

The core pathway is a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) cascade: Hormone → Receptor → G-protein → Adenylate Cyclase → cAMP → Protein Kinase A → Phosphorylation of Target Proteins → Cellular Response.

Step-by-Step Molecular Description1. Initial Signal: Hormone-Receptor Binding

Molecule: A hormone (e.g., adrenaline/epinephrine) circulates in the bloodstream.

Receptor: It binds specifically to the extracellular ligand-binding pocket of the β-adrenergic receptor on the target cell's plasma membrane.

Conformational Change: Hormone binding induces a significant conformational change in the receptor's intracellular domains. This activated receptor can now interact with the G-protein.

2. First Amplification & Activation: G-protein Cycle

The receptor now activates a heterotrimeric G-protein (Gₛ, where 's' stands for 'stimulatory').

Inactive State: In its resting, GDP-bound state, Gₛ is a trimer (αₛ, β, and γ subunits) with GDP bound to the α-subunit. It is associated with the receptor.

Activation:

The activated receptor acts as a Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor (GEF). It interacts with Gₛ, inducing a conformational change in the α-subunit.

This change causes the α-subunit to release GDP and bind GTP (which is much more abundant in the cytosol).

Dissociation:

GTP binding causes another conformational change, leading to the dissociation of the G-protein.

The αₛ-GTP subunit separates from the βγ dimer.

Action: The αₛ-GTP subunit diffuses along the membrane and binds to and activates its effector enzyme, Adenylate Cyclase.

Regulatory Step: The α-subunit has intrinsic GTPase activity. It will eventually hydrolyze the bound GTP to GDP, turning itself off. This provides a built-in timer for this step.

3. Second Amplification: cAMP Production

Enzyme: Adenylate Cyclase (AC) is an integral membrane protein. Its active site faces the cytoplasm.

Activation: Binding of αₛ-GTP stimulates the catalytic activity of AC.

Reaction: Activated AC converts intracellular ATP into the second messenger, cyclic AMP (cAMP).

Amplification: A single hormone-bound receptor can activate many Gₛ proteins, and each active AC enzyme can produce a large number of cAMP molecules. This is a major point of signal amplification.

4. Third Amplification: Protein Kinase A (PKA) Activation

Target: cAMP exerts its effects primarily by activating Protein Kinase A (PKA). PKA is a tetrameric enzyme consisting of two regulatory (R) subunits and two catalytic (C) subunits (R₂C₂).

Activation Mechanism:

In the inactive state, the R subunits bind to and inhibit the C subunits.

cAMP binds to the R subunits. Each R subunit has two cAMP-binding sites.

Binding of four cAMP molecules (two per R subunit) causes a conformational change, weakening the interaction between R and C.

This causes the dissociation of the complex, releasing the two active catalytic subunits.

The active C subunits are now free to phosphorylate specific serine or threonine residues on target proteins.

5. Physiological Response: Phosphorylation of Effector Proteins

The free catalytic subunits of PKA phosphorylate numerous downstream target proteins, altering their activity. Key examples include:

Metabolism (e.g., in muscle/liver): PKA phosphorylates and activates phosphorylase kinase, which in turn activates glycogen phosphorylase to break down glycogen for energy. Simultaneously, PKA phosphorylates and inhibits glycogen synthase, halting glycogen synthesis. This dual action maximizes glucose availability.

Gene Transcription (e.g., in the nucleus): PKA can enter the nucleus and phosphorylate the transcription factor CREB (cAMP Response Element-Binding protein). Phosphorylated CREB binds to cAMP response elements (CREs) in DNA, promoting the transcription of specific genes.

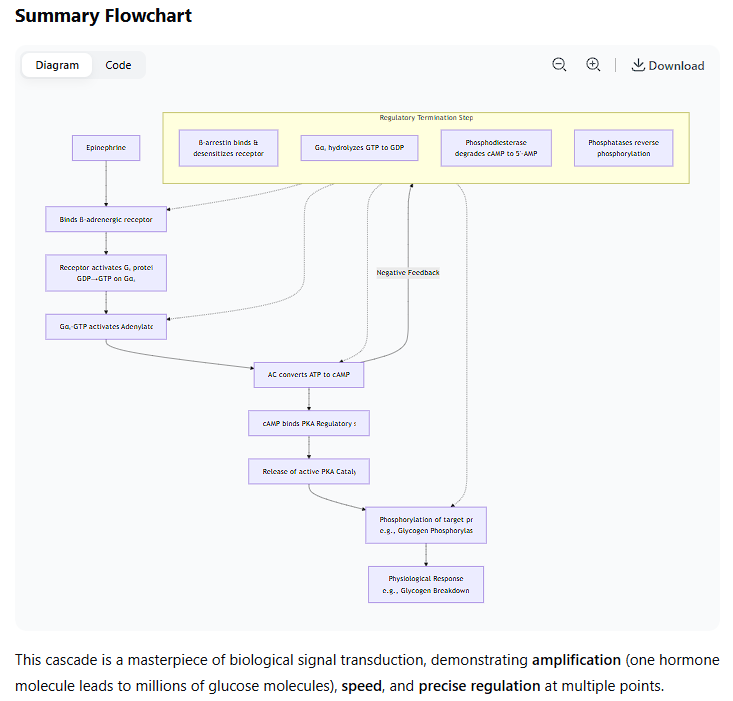

Critical Regulatory Steps (Termination of the Signal)

The system must be turned off to prevent overstimulation. This occurs at every level:

Receptor Desensitization:

Unbinding: The hormone concentration drops, and it dissociates from the receptor, which returns to its inactive state.

Phosphorylation: The activated receptor can be phosphorylated by specific kinases (e.g., G-protein-coupled Receptor Kinases, GRKs). This promotes the binding of β-arrestin protein, which sterically hinders further G-protein coupling and promotes receptor internalization.

G-protein Inactivation:

The intrinsic GTPase activity of the αₛ-subunit hydrolyzes GTP to GDP. This is the primary off-switch.

Regulatory Proteins: RGS proteins (Regulators of G-protein Signaling) can bind to αₛ, dramatically accelerating its GTPase activity, ensuring a rapid shut-off.

cAMP Degradation:

The enzyme phosphodiesterase (PDE) continuously hydrolyzes cAMP to 5'-AMP, which is inactive. This is a crucial and rapid mechanism for shutting down the signal. (Drugs like caffeine are non-specific PDE inhibitors).

PKA Inactivation:

As cAMP levels fall due to PDE activity, it dissociates from the R subunits of PKA.

The free R and C subunits reassociate, reforming the inactive R₂C₂ tetramer.

Dephosphorylation of Targets:

Protein Phosphatases enzymatically remove phosphate groups from the proteins that were phosphorylated by PKA, reversing the physiological effects.

Summary Flowchart

The entire process, with its regulatory steps, can be visualized as the following cascade:

This cascade demonstrates a highly efficient and tightly regulated system for translating an external hormonal signal into a rapid and powerful intracellular metabolic and genetic response.

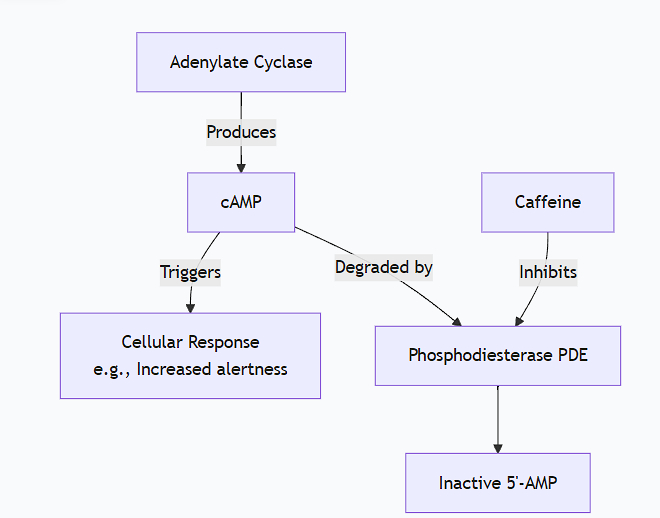

Explain how caffeine stimulates cAMP levels in target cells.

This is an excellent example of how a common molecule can interact with a fundamental signaling pathway.

Caffeine stimulates cAMP levels in target cells not by activating its production, but by inhibiting its degradation.

The key mechanism is the inhibition of phosphodiesterases (PDEs).

Here is a detailed, step-by-step explanation:

1. The Normal Role of Phosphodiesterases (PDEs)

In the cAMP signaling cascade (like the β-adrenergic pathway just described), the second messenger cAMP is synthesized by Adenylate Cyclase. To terminate the signal, the cell must break down cAMP. This is the job of phosphodiesterases (PDEs).

Enzyme: Phosphodiesterase (PDE)

Reaction: PDE hydrolyzes the 3'-phosphoester bond in cAMP, converting it into 5'-AMP, which is biologically inactive.

Function: PDEs are the primary "off-switch" for cAMP signaling, ensuring the cellular response is transient and proportionate to the stimulus.

2. Caffeine's Molecular Action: Competitive Inhibition

Structure Similarity: Caffeine, a methylxanthine, has a molecular structure that closely resembles adenosine, a core component of cAMP (which is cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate).

Binding: Because of this structural similarity, caffeine can enter the active site of the phosphodiesterase enzyme.

Inhibition: By binding to the active site, caffeine competes with cAMP for access. It acts as a competitive inhibitor. When caffeine is bound, the natural substrate (cAMP) cannot enter the active site and be hydrolyzed.

3. The Net Result: Accumulation of cAMP

With PDE activity blocked or reduced:

The rate of cAMP synthesis (by Adenylate Cyclase, which may have some basal activity or be stimulated by other signals) remains the same.

The rate of cAMP degradation is dramatically slowed.

This imbalance causes cAMP to accumulate to higher-than-normal levels within the cell.

4. Enhanced and Prolonged Signal

The elevated cAMP levels lead to:

Increased activation of Protein Kinase A (PKA).

Enhanced phosphorylation of PKA's target proteins.

In cells where cAMP signaling leads to excitatory effects, this results in the classic effects of caffeine:

In neurons: Promotes alertness and reduces drowsiness (partly by enhancing the effects of other stimulating neurotransmitters).

In fat cells (adipocytes): Enhances lipolysis (fat breakdown).

In heart muscle: Can contribute to a slight increase in heart rate (though caffeine has other complex effects on calcium and adenosine receptors that also influence this).

Important Nuance: Interaction with Adenosine Receptors

While PDE inhibition is a primary mechanism, especially at moderate caffeine doses, it's important to note that caffeine has a second major action:

Antagonism of Adenosine Receptors: Adenosine is a neuromodulator that promotes sleep and relaxation. It acts through its own GPCRs (A₁ and A₂ₐ), which typically inhibit neuronal activity.

Caffeine, again due to its structural similarity to adenosine, blocks these receptors, preventing adenosine from exerting its calming effects.

Synergy: This adenosine receptor blockade works in synergy with PDE inhibition. By blocking the inhibitory adenosine receptors, caffeine indirectly creates a neuronal environment that is more susceptible to excitation by other neurotransmitters, whose signals are then amplified by the elevated cAMP levels.

Summary

Mechanism | Molecular Target | Effect on Target | Net Result on cAMP |

|---|---|---|---|

Primary | Phosphodiesterase (PDE) | Inhibits its enzymatic activity | Increases levels by preventing its breakdown. |

Secondary | Adenosine Receptors (A₁/A₂ₐ) | Antagonizes (blocks) them | Creates a cellular state where the effects of elevated cAMP are more pronounced. |

In conclusion, caffeine stimulates cAMP levels primarily by inhibiting phosphodiesterases, the enzymes responsible for its degradation. This leads to an accumulation of cAMP, which amplifies and prolongs the signal in all pathways that use this ubiquitous second messenger.

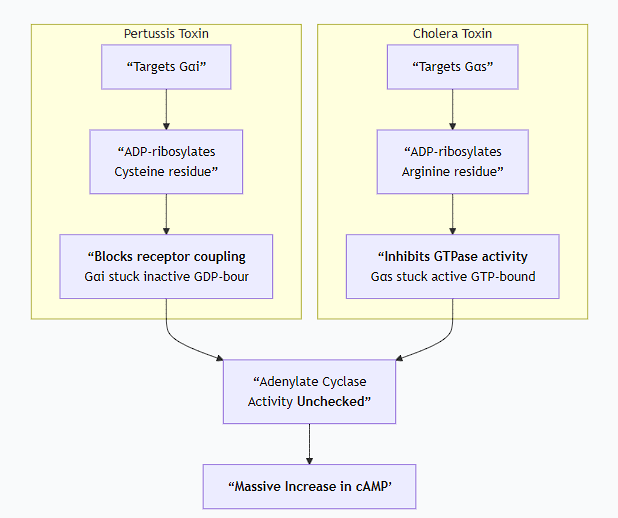

Explain how Bordetella pertussis and Vibrio cholarae toxins affect the action of G proteins.

This is a classic topic in medical biochemistry and microbiology, as these bacterial toxins are powerful tools that hijack G-protein signaling, but in diametrically opposite ways.

Both Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough) and Vibrio cholerae (cholera) produce toxins that target G-proteins. Their mechanisms are masterclasses in bacterial sabotage of host cell signaling.

Core Concept: The G-protein Cycle Recap

To understand the toxins, recall the normal G-protein cycle:

Inactive State: Gα is bound to GDP and complexed with Gβγ.

Activation: A stimulated GPCR acts as a GEF (Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factor), causing Gα to release GDP and bind GTP.

Signaling: Gα-GTP dissociates from Gβγ; both can regulate effector proteins.

Termination: Gα hydrolyzes GTP to GDP via its intrinsic GTPase activity. This is the critical off-switch. Gα-GDP then re-associates with Gβγ.

These bacterial toxins disrupt this cycle by chemically modifying the Gα subunit, either disabling or locking it in its active state.

1. Pertussis Toxin (PTX) - "The Disabler"

Source: Bordetella pertussis

Overall Effect: Inhibits Gᵢ (G-inhibitory) proteins. This leads to uncontrolled INCREASES in cAMP levels.

Molecular Mechanism:

Target: The toxin specifically targets the α-subunit of the Gᵢ family of G-proteins. (Gᵢ normally inhibits Adenylate Cyclase).

Action: ADP-ribosylation.

The A (active) subunit of pertussis toxin acts as an enzyme.

It catalyzes the transfer of an ADP-ribose group from the cellular cofactor NAD⁺ to a specific cysteine residue near the C-terminus of the Gαᵢ subunit.

Consequence: Uncoupling from the Receptor.

The ADP-ribosylation of Gαᵢ does not affect its intrinsic GTPase activity.

Instead, it blocks the interaction between Gαᵢ and the activated GPCR.

The receptor can no longer act as a GEF. It cannot instruct Gαᵢ to exchange GDP for GTP.

Cellular Outcome:

Gαᵢ remains locked in its inactive, GDP-bound state.

It cannot dissociate from Gβγ and thus cannot inhibit Adenylate Cyclase.

Since the "brake" (Gᵢ) is disabled, Adenylate Cyclase remains active, leading to uncontrolled production of cAMP.

Excess cAMP disrupts normal cell signaling, causing fluid secretion and other effects that contribute to the pathology of whooping cough.

In short: Pertussis toxin locks Gᵢ in the "OFF" (GDP-bound) state, preventing it from inhibiting Adenylate Cyclase, which runs unchecked.

2. Cholera Toxin (CTX) - "The Activator"

Source: Vibrio cholerae

Overall Effect: Activates Gₛ (G-stimulatory) proteins. This leads to uncontrolled INCREASES in cAMP levels.

Molecular Mechanism:

Target: The toxin specifically targets the α-subunit of the Gₛ family of G-proteins. (Gₛ normally stimulates Adenylate Cyclase).

Action: ADP-ribosylation.

The A subunit of cholera toxin acts as an enzyme.

It catalyzes the transfer of an ADP-ribose group from NAD⁺ to a specific arginine residue within the GTPase active site of the Gαₛ subunit.

Consequence: Inhibition of GTPase Activity.

The bulky ADP-ribose group sterically hinders the GTPase active site.

This abolishes the intrinsic GTPase activity of Gαₛ.

Gαₛ can bind GTP and become activated, but it cannot hydrolyze GTP back to GDP.

Cellular Outcome:

Gαₛ becomes permanently locked in its active, GTP-bound state.

It continuously stimulates Adenylate Cyclase.

This results in a massive and prolonged overproduction of cAMP in intestinal epithelial cells.

High cAMP levels cause a dramatic efflux of ions (Cl⁻, Na⁺) and water into the intestinal lumen, leading to the profuse, watery diarrhea characteristic of cholera.

In short: Cholera toxin locks Gₛ in the "ON" (GTP-bound) state, causing it to permanently stimulate Adenylate Cyclase.

Comparison and Contrast

The following chart summarizes the key differences and similar outcomes of these two toxins:

Summary Table

Feature | Pertussis Toxin | Cholera Toxin |

|---|---|---|

Bacterium | Bordetella pertussis | Vibrio cholerae |

Target G-protein | Gᵢ (Inhibitory) | Gₛ (Stimulatory) |

Type of Modification | ADP-ribosylation | ADP-ribosylation |

Amino Acid Modified | Cysteine | Arginine |

Biochemical Effect | Uncouples Gᵢ from receptor; prevents activation. | Inhibits GTPase activity; prevents inactivation. |

State of G-protein | Locked OFF (GDP-bound) | Locked ON (GTP-bound) |

Final Outcome on cAMP | Dramatic INCREASE (by removing inhibition) | Dramatic INCREASE (by causing constant stimulation) |

Primary Physiological Effect | Whooping cough (disrupted immune cell signaling) | Profuse, watery diarrhea (disrupted ion transport) |

Explain the mechanism of action of insulin, insulin-like hormones and growth factors.

The mechanism of action for insulin, insulin-like hormones, and growth factors represents a fundamental paradigm in cell signaling: activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs).

While they have distinct physiological roles, their molecular mechanisms share a common core pathway with critical variations.

Overarching Principle: Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) Signaling

All these ligands work by binding to and activating specific receptors on the cell surface that have intrinsic enzyme activity in their cytoplasmic domains. This activity is tyrosine kinase activity—the ability to transfer a phosphate group from ATP onto tyrosine residues of proteins.

1. Insulin and Insulin-like Growth Factors (IGFs)

Insulin (metabolism) and IGFs (growth/survival) act through very similar Type II RTK pathways.

Step-by-Step Mechanism:

1. Ligand Binding and Receptor Conformational Change:

The insulin receptor (IR) and IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) exist as dimers (two halves) even without the ligand.

Insulin binds to the extracellular α-subunits of the receptor.

2. Receptor Autophosphorylation and Full Activation:

Ligand binding induces a major conformational change that brings the intracellular β-subunits (which contain the kinase domains) into close proximity.

This allows each kinase to phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the other subunit—a process called trans-autophosphorylation.

This phosphorylation serves two purposes:

It unlocks the kinase domain, fully activating its enzymatic activity.

It creates phosphotyrosine docking sites for downstream signaling proteins.

3. Docking of Adaptor Proteins:

Key adaptor proteins, most importantly IRS (Insulin Receptor Substrate) proteins, are recruited to the phosphorylated docking sites on the receptor.

4. Phosphorylation of IRS:

The activated receptor kinase then phosphorylates multiple tyrosine residues on the IRS protein.

5. Activation of Downstream Pathways:

The phosphorylated IRS acts as a central signaling hub, recruiting and activating various effector proteins that contain SH2 domains, leading to two major signaling branches:

The PI3-Kinase/Akt (PKB) Pathway (Primary for Metabolic Effects):

The lipid kinase PI3-Kinase binds to phosphorylated IRS.

PI3-Kinase phosphorylates the membrane lipid PIP₂ to generate PIP₃.

PIP₃ acts as a docking site for proteins like Akt (PKB) and PDK1.

PDK1 phosphorylates and activates Akt.

Active Akt is the central metabolic regulator:

GLUT4 Translocation: Promotes the movement of glucose transporters (GLUT4) to the cell membrane → increased glucose uptake.

Glycogen Synthesis: Activates glycogen synthase.

Protein Synthesis: Activates mTORC1.

Lipid Synthesis: Regulates key enzymes.

Anti-apoptosis: Inhibits pro-apoptotic factors.

The Ras/MAPK Pathway (Primary for Growth Effects):

The adaptor protein Grb2 binds to phosphorylated IRS, which recruits SOS.

SOS activates the small G-protein Ras.

Ras initiates the MAP Kinase cascade (Raf → MEK → ERK).

ERK translocates to the nucleus and phosphorylates transcription factors (e.g., Elk-1), promoting gene expression for cell growth and proliferation.

Key Difference between Insulin and IGFs: While the mechanism is identical, the context and outcome differ. Insulin signaling is geared toward acute metabolic control (glucose disposal, storage), while IGF signaling is geared toward long-term growth and survival. This is due to different receptor types, tissue expression, and connections to other regulatory systems.

2. Other Growth Factors (e.g., EGF, PDGF, FGF)

Growth factors like Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) use a slightly different flavor of the RTK mechanism, classified as Type I.

Step-by-Step Mechanism:

1. Ligand-Induced Receptor Dimerization:

For many growth factor receptors (like EGFR), the receptors are monomers in the absence of ligand.

The ligand itself is bivalent and acts as a bridge, inducing the dimerization of two receptor monomers.

2. Trans-autophosphorylation:

Dimerization brings the kinase domains together, leading to trans-autophosphorylation on tyrosine residues in their cytoplasmic tails, just like the insulin receptor.

3. Direct Docking and Signaling:

The main difference from the insulin pathway is that adaptor proteins like IRS are typically not involved.

Instead, downstream signaling proteins (e.g., Grb2, PI3K, PLCγ) bind directly to the specific phosphotyrosine docking sites on the activated receptor.

4. Activation of Downstream Pathways:

The same core pathways are activated:

Grb2/SOS → Ras → MAPK Pathway: Strongly promotes cell proliferation and differentiation.

PI3-Kinase → Akt Pathway: Promotes cell survival and growth.

PLCγ Pathway: Some growth factor receptors also activate Phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), which cleaves PIP₂ to generate IP₃ (triggering Ca²⁺ release) and DAG (activating PKC).

Summary and Comparison

Feature | Insulin / IGFs | EGF, PDGF, FGF, etc. |

|---|---|---|

Receptor State | Pre-formed dimer | Ligand-induced dimerization/multimerization |

Key Adaptor Protein | IRS proteins are essential hubs | Typically no IRS; effectors bind directly to receptor |

Primary Signaling | Strong PI3-K/Akt (metabolism) & MAPK (growth) | Strong MAPK (proliferation) & PI3-K/Akt (survival) |

Main Physiological Role | Metabolic Homeostasis (Insulin), Growth (IGF) | Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, Migration |

Regulatory Step: Termination of the Signal

The signal is tightly controlled to prevent continuous growth or metabolic activity:

Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases (PTPs): Remove phosphate groups from the receptor and signaling proteins.

Receptor Internalization: The ligand-receptor complex is endocytosed and can be degraded or recycled.

Negative Feedback: Akt and ERK can phosphorylate IRS and other upstream components, desensitizing the pathway.