VETM3470 - Anesthesia and Pharmacology - Term Test #4

1/269

Earn XP

Description and Tags

From Antonia Degroot set via quizlet (doesn't include anticonvulsants)

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

270 Terms

What % of the adult body weight is fluid?

60%

Two types of fluids in the body

1. Intracellular fluid - inside the cells - 40% of body weight

2. Extracellular fluids - outside the cells - 20% of body weight

Both fluids are separated by the cell membrane. Cells create and maintain the difference between intra and extra cellular fluid.

Characteristics of intracellular fluid (ICF)

- 2/3 of body's water (40% of body weight)

- Primarily a solution of potassium, organic anions and proteins

- ICF is not homogenous

- pH is close to 7

Characteristics of extracellular fluid (ECF)

- 1/3 of the body's water (20% of body weight)

- Primarily NaCl and NaHCO3 (bicarb)

- ECF is divided into three sub compartments

- pH is 7.4-7.45

What are the three sub compartments of ECF

Interstitial fluid:

- Surrounds the cells, but doesn't circulate

- About 3/4 of the ECF

Plasma:

- Circulates as the extracellular component of blood

- About 1/4 of the ECF

Transcellular fluid:

- Is a set of fluids that are outcome of the normal compartments (CSF, digestive juices, etc.)

Dog blood and plasma volume

Blood volume: 80 ml/kg (8% of body weight)

Plasma volume: 49 ml/kg

Cat blood volume

50-70 ml/kg (5-7% of body weight)

Horse blood volume

100 ml/kg (10% of body weight)

Ruminant blood volume

60 ml/kg (6% of body weight)

Pig blood volume

65-75 ml/kg (6.5-7.5% of body weight)

In blood, how much is plasma and how much is packed cell volume (PCV)

Plasma: 55-65%

PCV: 35-45%

How much blood would 20 kg dog have?

20 kg x 80 ml/kg = 1600 ml

What kind of equilibrium are the fluid compartments of the body in

Osmotic equilibrium, water moves freely

Therefore the osmolarity of ICF = ECF = plasma

Osmolarity =

ratio of solute/volume

What is the value of normal osmolarity in the body

290 +/- 10 mOsm/liter

What is oncotic pressure

The pressure exerted specifically by protein molecules in a compartment

What two oncotic pressures are competing with each other

Oncotic pressure of the plasma and oncotic pressure of the interstitial fluid/space

What are some maintenance solutions we use

1. Plasmalyte-56, normosol M

2. NaCl 0.45% + KCl

3. Replacement + KCl

What are maintenance solutions used for?

To maintain volume and electrolyte composition, when dealing with:

A. Sensible losses (urine) 1-2 ml/kg/hr

B. Insensible loses (breathing, feces, sweating) 1 ml/kg/hr

Together, A + B should be about 2-4 ml/kg/hour

What can you NOT use a maintenance solution for?

Replacement solution

What are some replacement solutions that we use?

1. Lactated ringer solution

2. Plasmalyte-A

3. Plasmalyte 148

4. Normosol-R

5. NaCl 0.9% +/- KCl

What are replacement solutions used for?

To replace volume without altering the electrolyte composition of plasma, this includes accounting for: maintenance requirements + blood/fluid loss

5-10 ml/kg/hr

Properties of crystalloids

- Isotonic and polyionic

- No oncotic pressure

- 20-30% of it will remain in the vascular space after 1-2 hours (example if you give 1 L, 200-300 ml should remain in the vascular space)

- Large volumes can cause excessive extravasation

Replacement rate of crystalloids

5-10 ml/kg/hr

If you want to replace blood loss using crystalloids, how much do you need to give?

Since 20-30% of it will remain in the vascular space after 1-2 hours, you must use three times the amount of crystalloids than blood you lost

Example: You lost 5 ml of blood, give 15 ml of crystalloids (5x3)

To what extent can blood loss be effectively treated with crystalloids

10% of blood loss or less (higher volumes would require too much fluid)

What volume of crystalloids do you have to give a 20 kg dog with 10% blood loss

8% blood volume in dogs means they have

80 ml/kg x 20 kg = 1600 ml of blood

10% blood loss means they have lost 0.10 x 1600 = 160 ml of blood

Effective replacement using crystalloids would be 3x what was lost = 480 ml of crystalloids

At what rate can you give crystalloids during shock?

60 ml/kg/hr

Crystalloid solutions we use in practice

Hypertonic saline, 5-7.5% solutions

Characteristics of hypertonic saline use

- Volume expansion lasts less than 60 minutes

- Small volume (2-6 ml/kg)

- Give at: 1-2 ml/kg/min, therefore volume can be injected in 1-6 minutes

What are colloids?

- Solutions containing large molecules that are trapped and stay within blood vessels

- They provide oncotic support

- As they stay in the vessel, smaller volumes are required for IV volume expansion (compared to crystalloids where 2/3 leak out of the IV space)

Two types of colloids we use in practice

1. Synthetic (dextran, starches)

2. Natural (plasma, blood)

Characteristics of colloid use

- Isotonic, volume expanders

- Large molecules

- 1.5-2 times oncotic pressure of blood for synthetic colloids

- Remain in the vascular compartment for 6-16 hours

- Rule of 1:1 replacement

- Give at: 5-10 ml/kg/hour (and do not exceed 30 ml/kg/day or clotting will be affected)

When do we give blood (versus a synthetic colloid) in dogs and cats?

Dogs: If the PCV is < 20-25%

Cats: If the PCV is < 15-30%

(normal PCV should be at least 35%)

How do you calculate how much blood to give a patient

ml blood = [(desired PCV - recipient PCV)/donor PCV] x 80 x body weight

OR

10-20 ml/kg of whole blood

When do you give plasma (versus a synthetic colloid)?

If total protein (TP) is < 3.5-4.0 g/dl

How do you calculate how much plasma to give a patient

ml of plasma = [(desired TP - recipient TP)/donor TP] x 60 x body weight

How much blood or plasma do you give when replacing fluid loss in a patient?

Rule of 1:1 replacement (aka give as much as they lost)

What is the rate at which we give blood or plasma

5-10 ml/kg/hr or as fast as needed

What is dehydration % based on?

Based on total body weight

When is an animal in shock due to dehydration

12% dehydration (means they have lost 12% of their total body weight)

How much fluid do you give to a dehydrated animal

volume (ml) = % dehydrated x body weight x 1000

If a 20 kg dog is 10% dehydrated, how many ml of fluid do they require?

= 0.10 x 20 x 1000

= 2000 ml

constant

How long does it take to replenish fluids in a dehydrated animal

To move fluid from ISF to ICF it takes several hours, may require up to 12-24 hours

Signs of dehydration on CBC include

Elevated TP and PCV

What will TP and PCV be like with blood loss

Low

- However, the PCV and TP may not change until the body retains fluids through the kidney and then they will lower

Administering crystalloids in the presence of blood loss will do what to PCV and TP?

Acutely lower it

If a 500 kg horse is 8% dehydrated, how much fluid have they lost? If they are not eating or drinking, how much fluids per hour do you need to give them to correct for dehydration and maintain them? Assume you are giving fluids over 12 hours.

Fluid lost due to dehydration:

= 0.08 x 500 kg x 1000 = 40 L

Plan to administer over 12 hours (40 L/12 hours = 3.3 L/hr)

constant

If not drinking or eating, add:

- 2 ml/kg/hr for maintenance

= 2 ml x 500 kg = 1 L/hr

THEREFORE, give 3.3 L/hr + 1 L/hr = 4.3 L/hr

What will giving fluids at shock rate do?

It will replace volume more or less equivalent to the patient's blood volume

What does the traditional approach to acid base balance look at?

Henderson Hasselbach equation, which estimates pH and base/excess deficits. It defines the magnitude of change but not the cause.

What is the acid base hydrolysis reaction

CO2 + H2O <-> H2CO3 <-> HCO3- + H+

What are the volatile and non volatile acids in the body?

Volatile: H2CO3 (carbonic acid) - ventilation

Non volatile: inorganic acid, organic acid, lactic acid, ketoacid - kidney, liver

Normal pH in the body

7.4

Normal PaCO2

40 mmHg

Normal HCO3- levels

22-26 mEq/L

Normal solubility of CO2

0.03

What is the definition of a base excess/deficit? How do you calculate the deficit?

- Any difference that exists from the normal value for bicarbonate

- Reflects non volatile acid changes (metabolic)

- Normal bicarb level is 24 mEq/L

- Deviation x 1.2 is how you calculate the deficit

If the bicarb level is 17 mEq/L, what is the acid base deficit (ABE)?

ABE is calculated by 1.2 x deviation of HCO3- from 24 (normal)

17-24 = -7

= 1.2 x 7

= -8.4 ABE

What is the definition of a buffer?

A substance that prevents extreme changes in the free concentration of H+ within a solution

Examples of biological buffers

- Hemoglobin

- NaHCO3

- Phosphate

- Protein

What is the Bohr effect? Where does it occur?

- Hemoglobin's oxygen binding affinity is inversely related both to acidity and to the concentration of carbon dioxide.

- It refers to the shift in the oxygen dissociation curve caused by changes in the concentration of carbon dioxide or the pH of the environment

- Since carbon dioxide reacts with water to form carbonic acid, an increase in CO2 results in a decrease in blood pH, resulting in hemoglobin proteins releasing their load of oxygen

- This occurs at the tissues

What is the chloride shift?

- A process which occurs during the circulation of oxygen and carbon dioxide through the blood

- The carbon dioxide is taken up by the RBCs and the enzyme carbonic anhydrase converts the CO2 to H2CO3, which breaks to give bicarbonate ion and hydrogen ion

- There is an exchange of bicarbonate and the chloride ions through the membrane of the red blood cells

- The chloride ions move inside and the bicarbonate is moving outside the red blood cells in the plasma

- This is the phenomenon which occurs to maintain the pH of the blood

What is the haldane effect? Where does it occur?

- Oxygenation of blood in the lungs displaces carbon dioxide from hemoglobin, increasing the removal of carbon dioxide

- Consequently, oxygenated blood has a reduced affinity for carbon dioxide. Thus, the Haldane effect describes the ability of hemoglobin to carry increased amounts of carbon dioxide in the deoxygenated state as opposed to the oxygenated state

- A high concentration of CO2 facilitates dissociation of oxyhemoglobin

- It occurs in the lungs

Where is CO2 found in the body? What is the break down of where its found?

1. Dissolved and H2CO3: 7%

2. HCO3-: 80%

3. CarbaminoHb: 13%

Acids versus bases handling of H+

Acids donate H+ to solutions

Bases remove H+ from solutions

What is electroneutrality?

- Establishes that there needs to be the same amount of cations and anions

- There are anions that are not routinely measured (unmeasured anions). They are phosphate, sulphate, organic acids (lactic acid), ketoacids +/- proteins

- Therefore, there is a deficit of anions in the gamblegram

What is a gamblegram?

A graphical representation of the concentration of plasma cations (mainly Na+ and K+) and plasma anions (mainly Cl-, HCO3- and A-)

What is the difference between acute and chronic alkalosis or acidosis?

Acute = uncompensated

Chronic = compensated

there is also somewhere in the middle, which is partly compensated

Reasons for metabolic acidosis?

- Acids from tissue metabolism (unmeasured anions like ketoacids, organic acids or lactic acid)

- Hyperchloremia

- A combination of both

What is metabolic acidosis? What is it related to?

When there is a low pH, it is related to low bicarb because the bicarb is being used to buffer H+ ions

When looking at blood gas values to determine if it is metabolic alkalosis or acidosis, what should you be looking at?

Look at ABE, it is not affected by CO2 values

If ABE is normal, what does this mean?

It is not a strictly metabolic problem

What is the normal ABE range?

0 to 4

A positive ABE means?

Alkalosis

A negative ABE mens?

Acidosis

For respiratory problems what does changes in the PaCO2 signify?

- Acidosis will result in increased PaCO2 (PaCO2 > 40 mmHg)

- Alkalosis will result in decreased PaCO2 (PaCO2 < 40 mmHg)

How do you determine if there is a mixed alkalosis or acidosis?

1. Calculate expected value of CO2 with provided formula, and compare to the actual value of CO2 from the blood gas

2. Determine if there is an ABE outside of normal

For respiratory acidosis, for every 10 mmHg increase in CO2, how much does bicarb increase?

1.3 units

If CO2 is 19 mmHg above normal, how much higher is HCO3-?

1.9 x 1.3 = 2.5 units

For respiratory alkalosis, for every 10 mmHg increase in CO2, how much does bicarb decrease?

2-3 units

If CO2 is 8 mmHg below normal, how much lower is HCO3-?

0.8 x 2 = 1.6

0.8 x 3 = 2.4

Therefore, 1.6-2.4 different than normal

What are the three independent variables in the quantitative acid base approach?

1. PaCO2

2. Strong ion difference (SID)

3. Weak acids (proteins in the blood)

Together, these determine the blood's pH

What is the normal strong ion difference? How is it calculated?

(Na+ + K+) - Cl- = 44

Therefore, metabolic acidosis < 44 and metabolic alkalosis is > 44

What are the properties of strong ions?

- They are dissociated (ex. NaCl -> Na+ + Cl-)

- Concentrations are not affected by other ions

What is the anion gap? How is it calculated?

(Na+ + K+) - (Cl- + HCO3-) = 20

Therefore, metabolic acidosis > 20, metabolic alkalosis < 20

What affects the anion gap?

Proteins

Proteins act as weak acids, therefore:

Hyperproteinemia = metabolic acidosis

Hypoproteinemia = metabolic alkalosis

What are two weak ions/buffers in the body?

Proteins and hemoglobins, they are only partially dissociated

How is the strong ion gap (SIG) calculated?

SIG = AG - (total proteins x 0.25)

This calculation allows us to determine the unmeasured anions

What is shock?

- Inadequate oxygen delivery to the tissues - a condition of severe hemodynamic and metabolic dysfunction characterized by reduced tissue perfusion, impaired oxygen delivery and inadequate cellular energy production

- It is NOT a disease

- It is a syndrome associated with many disease conditions

Clinical signs associated with shock

- Reduced level of mentation

- Hypothermia and cool extremities

- Tachycardia for most animals, but bradycardia for cats

- Increased respiratory rate and effort

- Poor peripheral pulses

- Decreased blood pressure

- Pale mucos membranes

- Prolonged CRT

- Decreased urine production

- Decrease GI blood flow/GI ulceration

What is included in the physiological response to shock?

Increased sympathetic output (epinephrine and norepinephrine released from adrenal glands), which results in increased heart rate, cardiac contractility and vasoconstriction else where in the body (which allows heart flow to be maintained to heart and brain but can result in ischemia to less vital tissues)

Three endocrine responses in shock, and their time frame?

1. Epinephrine and norepinephrine

- Released from adrenal glands and vasomotor endplates

- Immediate response

2. Antidiuretic hormone

- Released from the pituitary

- To conserve water

- Response within minutes

3. Rein-angiotensin-aldoesterone (RAAS) system

- At the level of the kidneys

- Stimulated to conserve Na+ and water

- Response within hours

Three stages of shock

1. Early compensatory shock

- Physiological responses maintain blood pressure

2. Early decompensatory shock (classic shock)

- Associated with clinical signs of shock

3. Decompensatory/terminal shock

- Irreversible shock

Describe early compensatory shock

- Appropriate cardiovascular compensation occurring

- Clinical signs include: tachycardia (to maintain O2 delivery to the body), normal or elevated BP, normal to increased pulses, hyperemic mm, CRT < 1 sec

- Easily missed, animal essentially appears normal

- Result of baroreceptor mediated released of catecholamines

- Successful increase in cardiac output

- Heart rate is KEY

- Good response noted to volume replacement, good outcome

Describe early decompensatory shock

- The second stage of shock

- Compensatory mechanisms are tiring

- Redistribution of blood flow occurs: decreased blood flow to kidneys, gut, skin and muscles

- Clinical signs include: tachycardia, tachypnea, poor peripheral pulses, hypotension, prolonged CRT, pale mm, hypothermia and depressed mentation

- Prognosis is fair to good with immediate intervention

Describe late decompensatory shock

- Terminal shock

- Compensatory mechanisms are exhausted

- Clinical signs include: slow heart rate (relative), pale cyanotic mm, absent CRT, weak/absent pulses, severe hypotension, hypothermia, mentally unresponsive/coma, no urine output

- Generally irreversible - not responsive to aggressive fluid resuscitation

- Damage has overwhelmed the body's natural protective mechanisms (multiple organ dysfunction/failure)

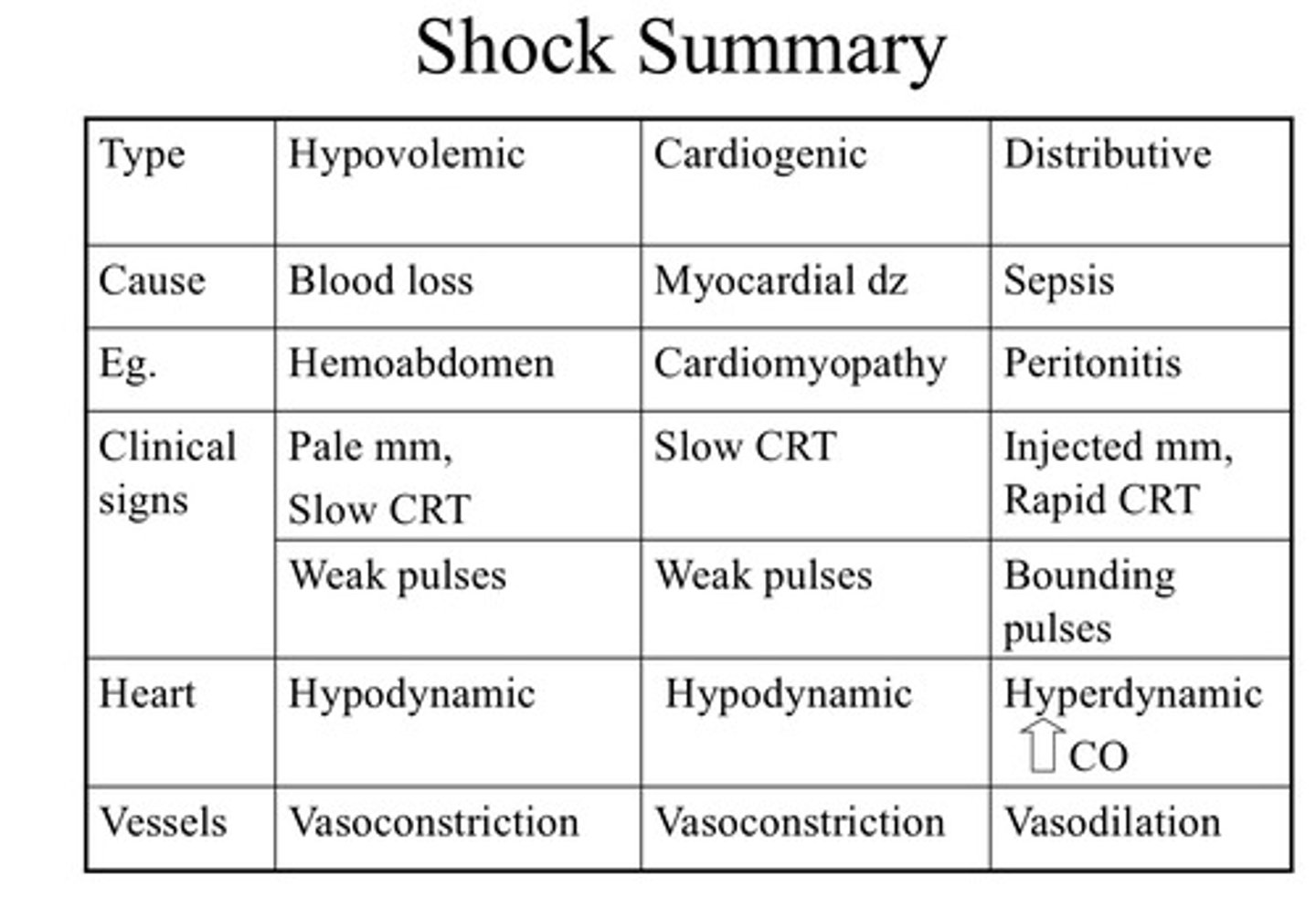

Four broad reasons/classifications for shock

1. Hypovolemic - hemorrhage or severe dehydration

2. Obstructive - GDV, blood clot

3. Distributive (vasodilatory or hyper dynamic)

4. Cardiogenic - inadequate ventricular pump function and inadequate delivery of oxygenated blood to vital organs

*patient can have more than 1 shock at a time*

Describe hypovolemic shock

- Profound decrease in intravascular (blood) volume

- Loss of > 30-40% of circulating blood volume OR 10-15% dehydration (this compromises IV space)

- This results in inadequate blood volume to deliver to vital organs and hypoperfusion

What does the body do in response to hypovolemic shock in phase 1

Interstitial fluid shifts

- Within 1 hour

- Body will attempt to restore intravascular volume and organ perfusion

- Fluid shift will dilute packed cell volume (PCV) and total solids (TS)

- Splenic contracture can occur in dogs and horses, resulting in release of sequestered RBCs (this will boost PCV but not TS)

What does the body do in response to hypovolemic shock in phase 2

Water retention

- Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) system

- This promotes Na+ and H2O retention in the kidneys

- PCV will continue to drop (within 8 hours you'll have a 36-50% decrease in PCV, and in 24 hours a 70% drop)

- Administration of crystalloids or colloids will cause more rapid decrease in PCV and TS