FMT-102-01: Introduction to Film Studies Final Study Guide

1/95

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

96 Terms

continuity editing

A system of cutting to maintain continuous and clear narrative action. Continuity editing relies on matching screen direction, position, and temporal relations from shot to shot. For specific techniques of continuity editing, see axis of action, crosscutting, cut-in, establishing shot, eyeline match, match on action, reestablishing shot, screen direction, shot/reverse shot.

crosscutting

Editing that alternates shots of two or more lines of action occurring in different places, usually simultaneously.

diegetic sound

Any voice, musical passage, or sound effect presented as originating from a source within the film's world. See also nondiegetic sound.

dialogue overlap

In editing a scene, arranging the cut so that a bit of dialogue coming from shot A is heard under a shot that shows another character or another element in the scene.

Framing

The use of the edges of the film frame to select and to

compose what will be visible onscreen.

deep space

An arrangement of mise-en-scene elements so that there is a considerable distance between the plane closest to the camera and the one farthest away. Any or all of these planes may be in focus.

deep focus

-A use of the camera lens and lighting that keeps objects in both close and distant planes in sharp focus.

-"Deep focus is a photographic and cinematographic technique using a large depth of field, meaning everything or almost everything is in focus."

shallow space

Staging the action in relatively few planes of depth; the opposite of deep space.

story

In a narrative film, all the events that we see and hear, plus all those that we infer or assume to have occurred, arranged in their presumed causal relations, chronological order, duration, frequency, and spatial locations; opposed to plot, which is the film's actual presentation of events in the story. See also duration, ellipsis, frequency, order, space, viewing time.

nondiegetic sound

Sound, such as mood music or a narrator's commentary, represented as coming from a source outside the space of the narrative.

nonsimultaneous sound

Diegetic sound that comes from a source in time either earlier or later than the images it accompanies.

nondiegetic insert

A shot or series of shots cut into a sequence, showing objects that are represented as being outside the world of the narrative.

point-of-view shot (POV shot)

A shot taken with the camera placed approximately where the character's eyes would be, showing what the character would see; usually cut in before or after a shot of the character looking.

jump cut

An elliptical cut that appears to be an interruption of a single shot. Either the figures seem to change instantly against a constant background, or the background changes instantly while the figures remain constant.

narration

The process through which the plot conveys or withholds story information. The narration can be more or less restricted to character knowledge and more or less deep in presenting characters' perceptions and thoughts.

tracking shot

A mobile framing that travels through space forward, backward, or laterally.

shot/reverse shot

Two or more shots edited together that alternate characters, typically in a conversation situation. In continuity editing, characters in one framing usually look left; in the other framing, right. Over-the-shoulder framings are common in shot/reverse-shot editing.

long shot

A framing in which the scale of the object shown is small; a standing human figure would appear nearly the height of the screen.

long take

A shot that continues for an unusually lengthy time before the transition to the next shot.

plot

In a narrative film, all the events that are directly presented to us, including their causal relations, chronological order, duration, frequency, and spatial locations; opposed to story, which is the viewer's imaginary construction of all the events in the narrative. See also duration, ellipsis, flashback, flashforward, frequency, order, viewing time.

sound bridge

(1) At the beginning of one scene, the sound from the previous scene carries over briefly before the sound from the new scene begins. (2) At the end of one scene, the sound from the next scene is heard, leading into that scene.

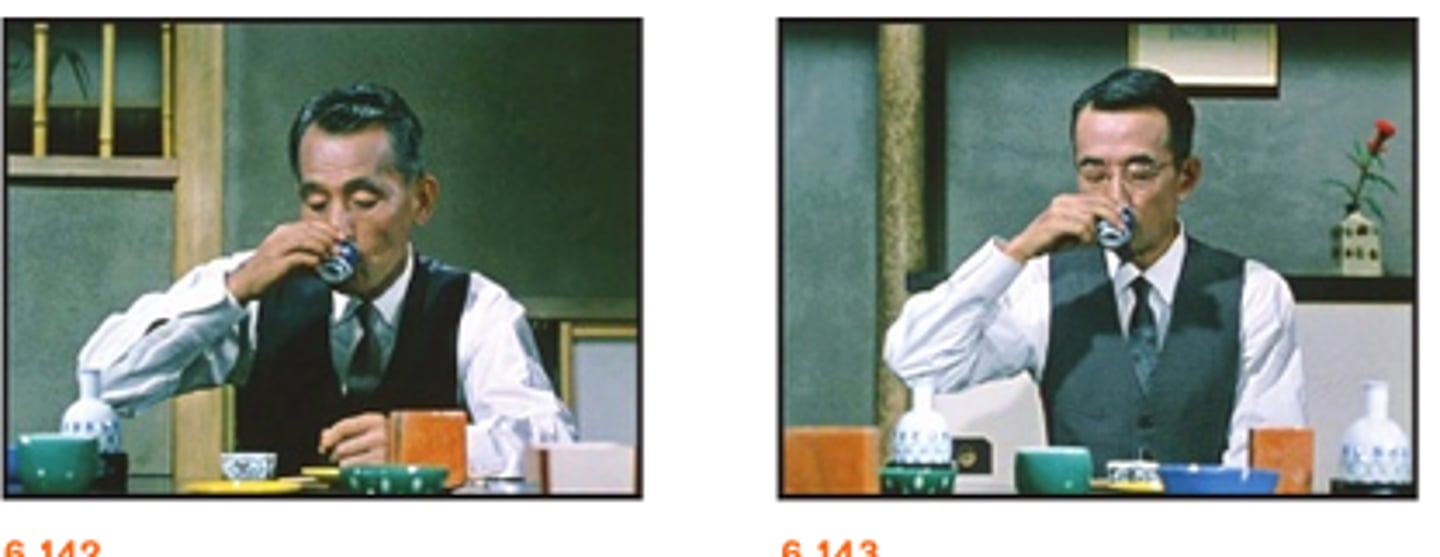

match on action

A continuity cut that splices two different views of the same action together at the same moment in the movement, making it seem to continue uninterrupted.

elliptical editing

shot transitions that omit parts of an event, causing an ellipsis in plot duration.

establishing shot

A shot, usually involving a distant framing, that shows the spatial relations among the important figures, objects, and setting in a scene.

motif

An element in a film that is repeated in a significant way.

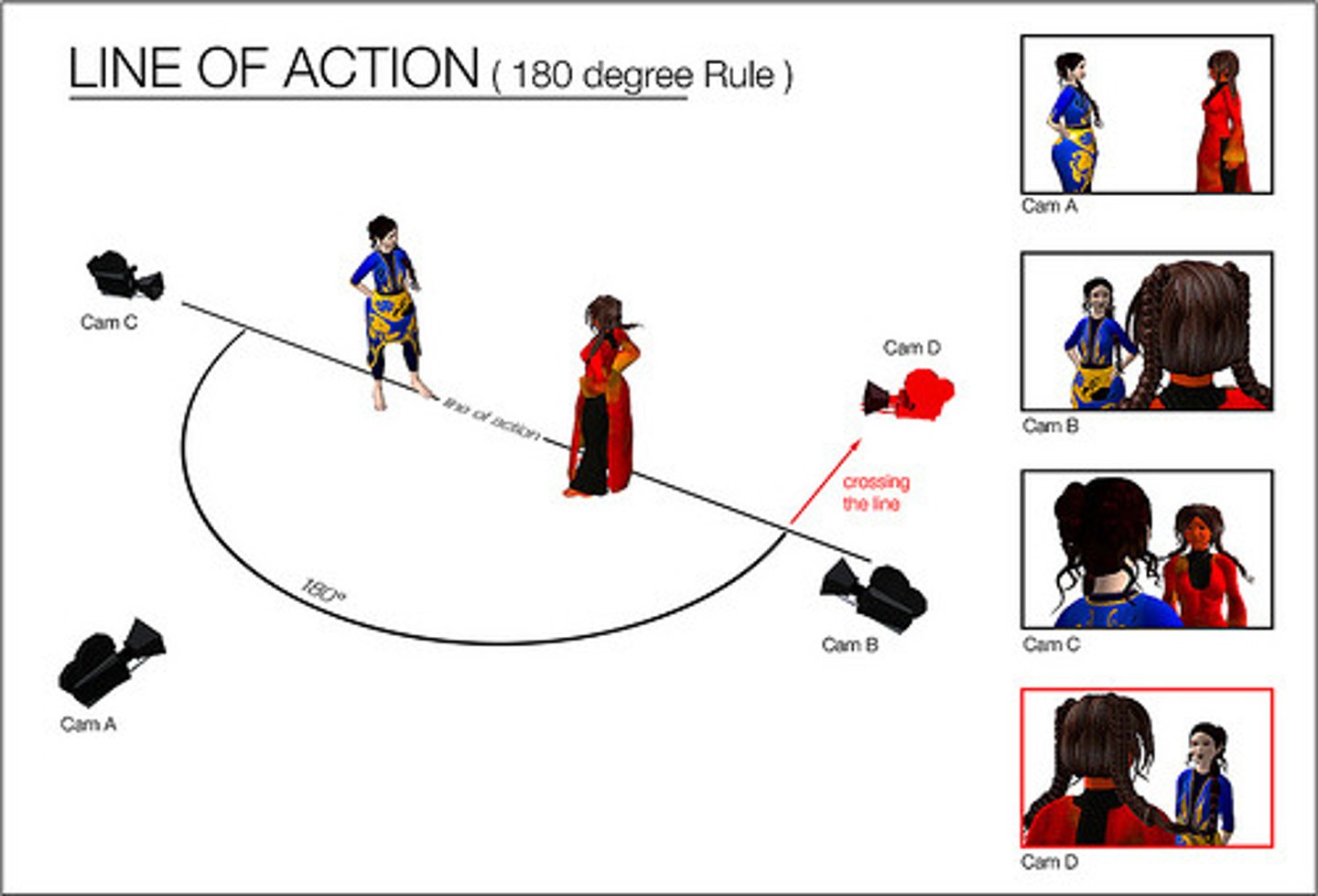

180° system

The continuity approach to editing dictates that the camera should stay on one side of the action to ensure consistent left-right spatial relations between elements from shot to shot. The 180° line is the same as the axis of action. See also continuity editing, screen direction.

eyeline match

A cut obeying the axis of action principle, in which the first shot shows a person looking off in one direction and the second shows a nearby space containing what he or she sees. If the person looks left, the following shot should imply that the looker is offscreen right.

racking focus

Shifting the area of sharp focus from one plane to another during a shot; the effect on the screen is called rack-focus.

reframing

Short panning or tilting movements to adjust for the figures' movements, keeping them onscreen or centered.

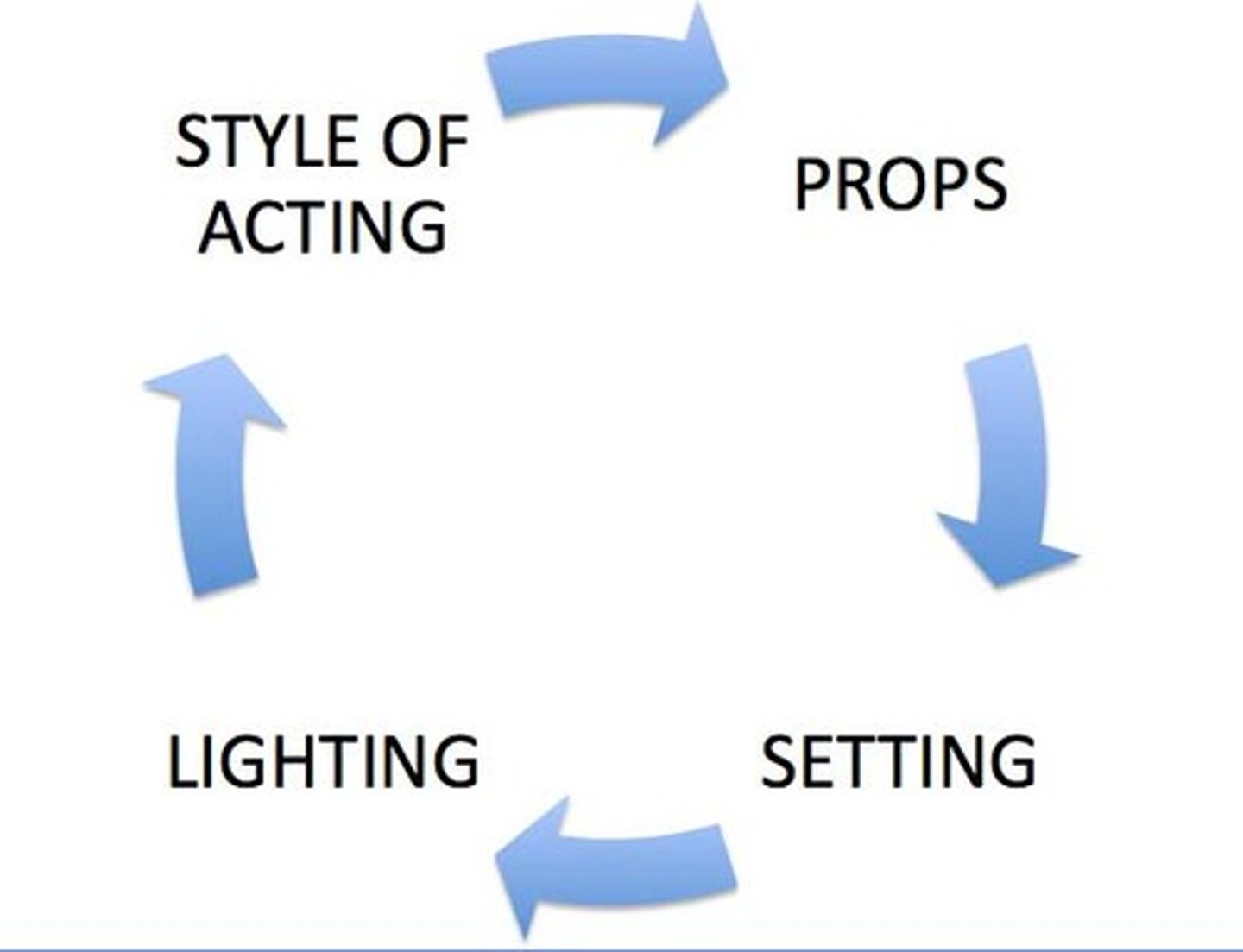

mise-en-scene

All of the elements placed in front of the camera to be photographed: the settings and props, lighting, costumes and makeup, and figure behavior.

Referential meaning

allusion to particular items of knowledge outside the film that the viewer is expected to recognize.

Explicit meaning

significance presented overtly, usually in language and often near the film's beginning or end.

Implicit meaning

significance left tacit, for the viewer to discover upon analysis or reflection.

Symptomatic meaning

significance that the film divulges, often against its will, by virtue of its historical or social context.

details about referential meaning

Refers to concrete, real-world elements that give the film its grounding in reality.

- Example from The Wizard of Oz: Dorothy is taken from a Kansas farm during the Depression to the mythical land of Oz. This draws on real-world references such as the Great Depression and the Midwestern climate.

- A viewer must recognize these references (e.g., Depression-era America) to fully understand the film's meaning.

- The setting (Kansas) plays a key role in contrasting with Oz's fantastical environment. If Dorothy were from a more affluent place like Beverly Hills, the contrast with Oz wouldn't be as stark.

details about explicit meaning

- Clear and direct themes or messages presented in the film.

- Example from The Wizard of Oz: Dorothy learns the importance of home

and family, epitomized by the line "There's no place like home."

- Explicit meanings interact with the film's form (context, timing, and

delivery), like the powerful impact of Dorothy's line in a close-up at the

film's end.

- The film's overall form emphasizes the contrast between Oz (magical but

risky) and Kansas (safe but mundane), which gives weight to the explicit

meaning about the value of home.

details about Implicit Meaning

- Abstract themes or ideas that are not directly stated but suggested through the film's content.

- Example from The Wizard of Oz: The film can be interpreted as symbolizing the transition from childhood to adulthood. Dorothy's desire to escape is an expression of adolescence, but her return home shows her acceptance of adult responsibilities.

- Implicit meanings are open to interpretation and can vary from viewer to viewer.

- Filmmakers may leave implicit meanings up to interpretation, but some might guide viewers toward specific subtexts (e.g., Forrest Gump being about grieving).

- Broad themes (like adolescence, courage, or love) are useful, but they don't fully capture the film's specific experience.

details about symptomatic meaning

Refers to meanings that reflect societal values, ideologies, or cultural

beliefs, often shaped by the time and place in which the film was made.

- Example from The Wizard of Oz: The film's focus on the importance of

home reflects American societal values during the 1930s, particularly

during economic crises.

- Symptomatic meanings point to larger cultural ideologies, like views on

family, adolescence, or societal values during the Great Depression.

- These meanings are often tied to the social context of the time, and

different cultures may have different interpretations of themes like home

or adolescence.

- Films can reveal ideological meanings through their form (e.g., narrative

and style), and critics can analyze these for cultural insights.

Motifs

any significant repeated element that contributes to the overall form; An element in a film that is repeated in a significant way.

Ex: object, a color, a place, a person, a sound, or even a character trait. -Motifs→ often reappear at climaxes or highly emotional moments.-A lighting scheme or camera position can become a motif.-motifs→ fairly exact repetitions

-Parallels cue us to compare two or more distinct elements by highlighting some similarity. -motifs→ can help create parallels among characters and situations.

Story Duration

The entire time span of events in the narrative.

Plot Duration

The time span of events selected by the plot to present.

Screen Duration

The actual time spent watching the film (e.g., 20 minutes, 2 hours, or more).

Objective vs. Subjective Narration

○ Objective: External actions/behavior, no insight into characters' internal states.

○ Subjective: Inner thoughts, feelings, or perceptions of characters.

○ Example: Voice-over monologues or point-of-view shots to express subjective

narration.

Omniscient narration and restricted narration

Omniscient Narration:

○ Suited for films dealing with large-scale events and multiple perspectives (e.g.,

historical films).

○ Strengthens themes by providing a comprehensive view.

● Restricted Narration:

○ Common in mystery and detective genres where withholding information

enhances suspense and engagement.

viewers reactions for restricted vs. omniscient narration

● Omniscient narration offers a comprehensive view, shaping the film's themes and broadening the emotional impact.

● Restricted narration builds suspense by keeping viewers aligned with the protagonist's knowledge and discoveries.

Classical Hollywood Cinema

Definition:

● Tradition since the 1920s, shaped Hollywood and global cinema.

● Focus on clear narrative, individual characters, and psychological causes.

● Examples: The Road Warrior (Australian), Super Size Me (documentary).

Core Features:

● Protagonist's Goal: Central character has a clear goal (e.g., Dorothy's homecoming).

● Opposition: Conflict from an opposing character or force (e.g., Dorothy vs. the Wicked

Witch).

● Character Change: Protagonist grows or alters attitude/values (e.g., Max in The Road

Warrior).

● Cause and Effect: Psychological motivations drive actions, clear cause-effect narrative.

Plot Structure:

● Goal & Conflict: Central conflict develops from protagonist's goal and opposition.

● Blocking Element: Antagonistic force obstructs goal, driving conflict (e.g., Dorothy vs.

the Witch).

● Time Management: Non-essential time skipped; key moments highlighted (e.g., omitted

walking scenes in The Wizard of Oz).

● Deadlines & Appointments: Plot structured around meeting deadlines, creating

urgency (e.g., The Wizard of Oz). Narrative Techniques:

● Objective Narration: Most of the time, the narrative presents an external reality.

● Unrestricted Narration: Information shown that protagonist doesn't know to build

suspense (e.g., The Road Warrior).

Classical Hollywood Cinema continued

● Mystery Genre Restriction: Mystery films may restrict character knowledge for

dramatic effect (e.g., The Big Sleep). Closure:

● Strong Closure: Clear resolution of all conflicts, mysteries, and character fates.

● Final Resolution: Outcome of conflict and character arcs resolved (e.g., Dorothy

returning home). Exceptions:

● Some filmmakers break conventions (e.g., Godard, Dreyer).

● Unmotivated Material: Includes elements not serving the narrative directly (e.g.,

political monologues in Godard's films).

● Subjective Narration: Films may blur the line between objective/subjective (e.g., Last

Year at Marienbad). Broader Context:

● Classical Hollywood is one of many narrative styles in film.

● Understanding different forms enriches cinematic appreciation.

Final Thought:

● Classical storytelling is just one model; other narrative forms offer varied approaches to structure, time, and character.

Story vs. Plot

Story vs. Plot

● Story: The chronological sequence of events in the narrative.

● Plot: The presentation of these events to the audience, which can include non-linear

timelines, flashbacks, and other creative techniques.

● Diegesis: The total world of the story action, including both depicted and inferred

events.

Restricted Narration

(The Big Sleep):

○ Focuses on one character's experiences and reveals information gradually.

○ Example: We only know what Philip Marlowe knows, which maintains the

mystery.

-(limited knowledge)

Restricted Narration (The Big Sleep):

○ Focuses on one character's experiences and reveals information gradually.

○ Example: We only know what Philip Marlowe knows, which maintains the mystery.

○ Common in mystery and detective genres where withholding information

enhances suspense and engagement.

● Restricted narration builds suspense by keeping viewers aligned with the protagonist's knowledge and discoveries.

Unrestricted vs. Restricted Narration

● Not absolute categories, but exist on a continuum.

● Filmmakers can choose to broaden the range of knowledge without reaching the full

omniscient level (like The Birth of a Nation).

Motif examples

rosebud(Citizen Kane), the Swimming pool in La Cienaga(The Swamp), the beach in Moonlight, the Yellow Brick Road in Wizard of Oz

Mis-en-scene

-All of the elements placed in front of the camera to be photographed: the settings and props, lighting, costumes and makeup, and figure behavior.

-A French term meaning "putting into the scene," it refers to everything that appears in the frame of a film or theater production, shaping the audience's experience.Was first applied to the practice of directing plays.

Components of Mise-en-Scène:

Setting: The environment or location where the action takes place, including props, furniture, architecture, and nature.

Lighting: The use of light to set mood, highlight characters, or create visual contrast. It influences how the audience perceives characters and scenes.

Costume and Makeup: The clothing, hair, and makeup that reveal characters' personalities, status, and roles in the story.

Staging and Blocking: The arrangement and movement of actors in the scene, including placement and interaction.

Performance: The actor's delivery of lines, gestures, and expressions, influencing the emotional tone of the scene.

Components of Mise-en-Scene

"Mise-en-scene offers the filmmaker four general areas of choice and control: setting, costumes and makeup, lighting, and staging (which includes acting and movement in the shot)".

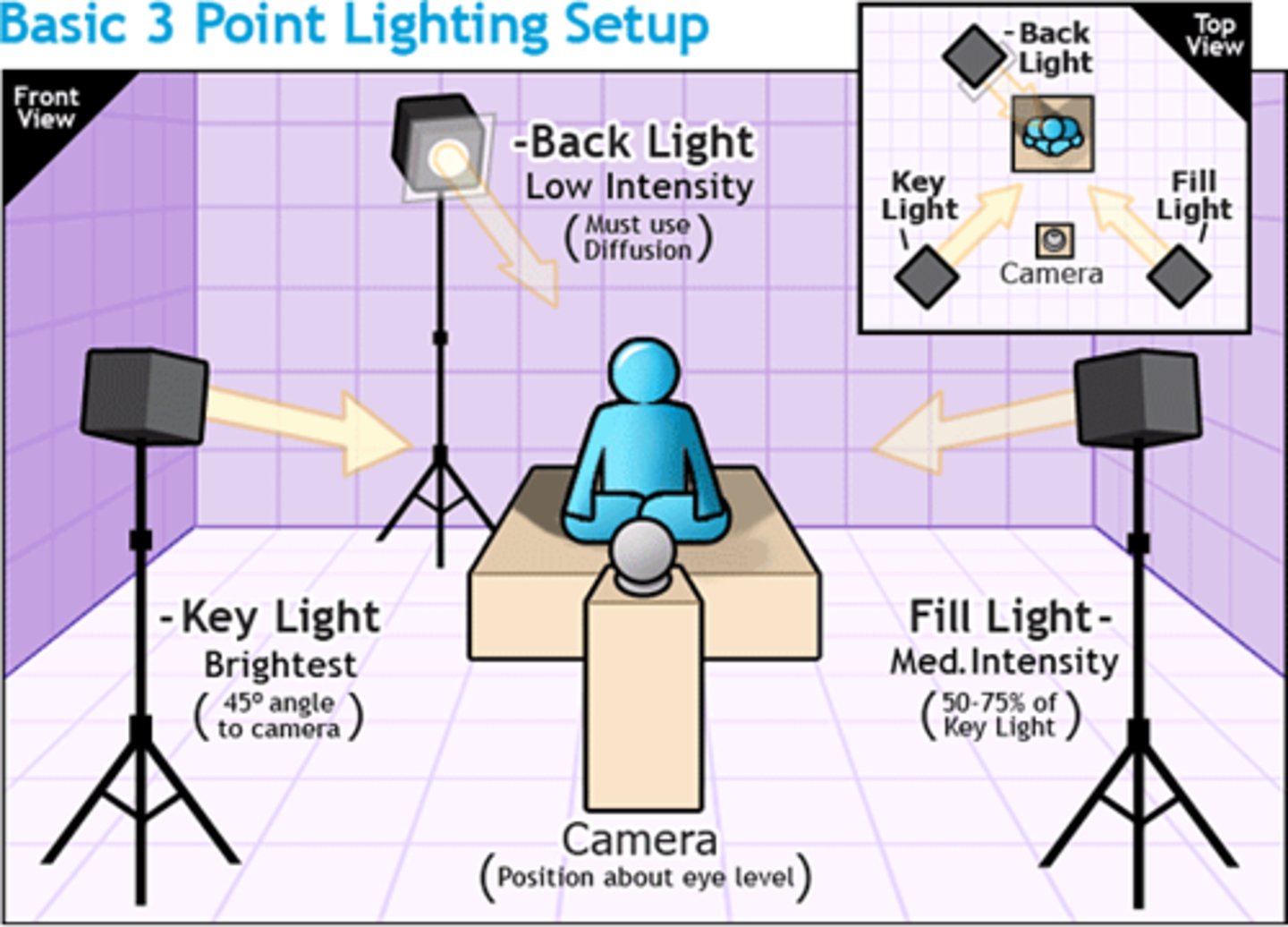

three-point lighting

A common arrangement using three directions of light on a scene: from behind the subjects (backlighting), from one bright source (key light), and from a less bright source balancing the key light (fill light).

Backlighting

Illumination cast onto the figures in the scene from the side opposite the camera, usually creating a thin outline of highlighting on those figures.

fill light

Illumination from a source less bright than the key light, used to soften deep shadows in a scene. See also three-point lighting.

key light

In the three-point lighting system, the brightest illumination coming into the scene. See also backlighting, fill light, three-point lighting.

POV cutting

POV cutting and altered states of perception (e.g., dizziness, drunkenness) were depicted using camera movements, slow motion, or distorted shots.

-For example, in Coeur fidèle (1923), a superimposition shows the bartender's emotional state by overlaying waterfront imagery

art cinema

-ambiguous/ unclear character motivation

-psychological complexity(relationships)-versimilitude

-discontinuity style

open ended (no narrative closure)

-rejects causality-meandering narrative

-no clear climax/resolution

-margins

-production/distribution

-Director/ author becomes visible

-sense of director writing the script; director's identity; work with someone in particular( specific cinematographer/ editor)

-sometimes directors do actively participate in the editing

-Editing--> tend to be more women in a masculine, male-dominated industry

- Element of intertextuality

-auteur

-"Director as an author"

axis of action

axis of action In the continuity editing system, the imaginary line that passes through the main actors or the principal movement. The axis of action defines the spatial relations of all the elements of the scene as being to the right or left. The camera is not supposed to cross the axis at a cut and thus reverse those spatial relations. The axis of action is also called the 180° line. See also 180° system, screen direction.

Classical Hollywood Cinema

- invisible editing; continuity editing/style

-causality

3-act structure

-clear narrative development; clear character development

-character-driven motivation--> archetypal

(clear motivation)

-versimilitude

generic app...

-compositional unity

30 degree rule

- " if an editor cuts to the same character or object in another shot, the second shot must be positioned at least 30 degrees away from the first camera setup. If the camera moves less than 30 degrees, the cut between shots can look like a JUMP CUT or a mistake."

- "To avoid jarring discontinuity editing or a jump cut the two different shots must be taken from at least 30-degrees apart."

- "The 30-degree rule is a basic film editing guideline that states the camera should move at least 30 degrees relative to the subject between successive shots of the same subject."

180 degree rule

-"The 180 degree rule is a filmmaking guideline for spatial relations between two characters on screen. The 180 rule sets an imaginary axis, or eye line, between two characters or between a character and an object. By keeping the camera on one side of this imaginary axis, the characters maintain the same left/right relationship to each other, keeping the space of the scene orderly and easy to follow."

- "The rule states that the camera should be kept on one side of an imaginary axis between two characters, so that the first character is always frame right of the second character."

art film elements from Cleo 5 to 7

- nudity in model scene

- narrative discontinuity

- fiance character completely disappears, third act has none of characters we've previously seen

- not much narrative arc or character development

- Cleo seems a little less concerned with her appearance by the end but still self-centered

- by a female filmmaker, felt very feminine in its perspective, men aren't the most relevant characters

- external beauty, men's attention, cab driver

- authorship - director clearly focused on women's issues, New Wave film style is distinguished from more commercial films, stylistic elements

- emphasis on Paris setting, lots of movement, chaos in Paris

-Cleo's monologue: talking about her feelings

-cinematography: stair scene

-low-budget becoming artistic! nonactors

-realism: real view of traveling around Paris-open ending

-unclear motivation: why is Cleo wandering around?

shallow focus

"Shallow focus is a cinematographic technique incorporating a small depth of field. In shallow focus one layer of the image is in focus while the rest is out of focus. Shallow focus is typically used to emphasize detail."

offscreen sound

A form of sound, either diegetic or nondiegetic, that derives from a source we do not see. When diegetic, it consists of sound effects, music, or vocals that emanate from the world of the story. When nondiegetic, it takes the form of a musical score or narration by someone who is not a character in the story.

sounds that are part of the film's diegetic world (meaning they are sounds that the characters in the film could potentially hear) but are not visible on screen. It's a sound that originates from outside the frame of the shot but is within the story space.

Aspects of Cinematography

lighting, shot size, camera focus, shot composition, camera placement, camera movements, color, framing. camera distance, camera angle, depth of field

set design

-how you put together the space the film is being set.

- convey the information about the space/setting/movie

-mise en scene(subcategory: setting)

range/ depth of knowledge

-how much of the story we know

-knowledge/access to the story plot

-restricted narration limits the range of narration/ knowledge and information that we are provided.

depth of knowledge

- how well we know the. characters, how well we understand their motivation.

-have more depth of knowledge about the protagonist.

-how well we understand the characters' thoughts and feelings.

restricted narration

citizen Kane-rosebud

narration restricts what rosebud means

becomes unrestricted at the last minute when the audience ends up knowing more than the characters.

unrestricted narration

audience knows more than the characters; I Tonya for example

offscreen sound

-whatever caused the sound is not shown on the screen; sound is out of the screen.

- helps you construct sound and narrative space beyond the frame.

-sonic flashback, horror movie, conversation, etc.

-increases suspense and fear.

expressionistic mise-en-scene

-internal feelings

-express the internal stuff

-general mood and feelings of the scene

-The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

“the use of exaggerated and distorted visual elements in a film, such as set design, lighting, and costumes, to reflect a character's inner emotions or the psychological atmosphere of a scene.”

classical Hollywood cinema

citizen Kane, rear window

perceptual subjectivity

rear window; POV-shots- some mental subjectivity

- perceive what the characters perceive

- see and hear what the characters hear or see.

mental subjectivity

deeper knowledge of the characters' thoughts and feelings

POV cutting

-claim the perspective of the POV shot

-showing you which characters look at different shots

-makes the POV of the character very clear.

Documentary notes

Key issues in documentary filmmaking (The ‘D’ Word)

“The documentary response is one in which the image is perceived as signifying what it appears to record; a documentary film is one which seeks, by whatever means, to elicit this response; and the documentary movement is the history of the strategies which have been adopted to this end’ (Vaughan 1999: 58).”

Documentary makers as storytellers not journalists; needing to account for the authentic story

Roger and Me, Moore; scrutinized for lack of chronology

Profiting off of people; not compensating

Types of documentary (definitions, examples)

Docudrama

Not necessarily having valid documentation; based on documentation

Differing proportions of dramatisation and verifiable documentary

Mockumentaries

Fake documentaries

Invention of subjectivity

I, Tonya as an example

Social, historical, political documentaries

Personal or subjective documentaries

Similar to autobiographies

“Nichols identifies ‘six modes of representation that function something like sub-genres of the documentary film genre itself: poetic, expository, participatory, observational, reflexive, performative’”

Poetic; prioritizes visual aspects

Expository; motive is to teach the audience

Participatory; participant observation, audience involvement (anthropological)

Observational; trying to capture something without interference from a filmmaker

Reflexive; focuses on filmmaking, rather than a subject

Performative; focuses on the filmmakers experiences, emotions, etc., as the focus of the narrative

Narrative as what sets documentary aside from raw footage

The Thin Blue Line Discussion

Similar to I, Tonya–interviews, followed by actor’s portrayal of the accounts

Recreation of events

Close-up shots

Insert shots (text, papers)

Proved to turn around the case via the documentary

More documentary notes

Definition of Documentary:

It is a record of a fiction dreamed up by a real person, living in actual times, and bound up, like you and me, in a socio-political context.

Connection between Documentary and Narrative:

There is always a process of narrative construction. In a documentary, there is a process of telling a story through editing.

Key Issues in Documentary Filmmaking (The ‘D’ Word)

Monetizing the exploitation of the subjects

Need to compensate others.

The major issue is the subjectivity of truth and trying to ensure that what the filmmakers are doing is showing the truth with fairness and accuracy:

“it is the director’s responsibility to ensure fairness and accuracy … The director must not deliberately mislead the viewers’ (Winston 2000: 116). ‘Mendacious documentarists’, concurs Winston (ibid.: 157), ‘should be vigorously exposed and denounced in the marketplace of ideas.’ There is a distinction here, a moral line, drawn between the acceptable rhetorical and interventionist practices of Michael Moore, and the ‘artless’ construction of sensationalist artifice (as exemplified, albeit with extraordinary legal implications, in the currently unfolding Souza case): the creation of false history by passing off dramaturgy as actuality.”

Forcing the director to follow a strict code of ethics when creating a film about people.

This article suggests allowing the audience to see the editing and film-making process at work to know about what the truth can be.

By allowing an audience to watch a documentary, a non fiction story here. It makes the audience have their own opinions and create perceptions on a film that may or may not be true based on what the director is showing us.

“We have also seen how non-fiction enters into a negotiation around factuality, and into a ‘contract’ of sorts with its spectators, whose subjective, culturally dependent expectations and receptive preconceptions shape these discourses according to particularities of time and place.”

Types of Documentary (definitions, examples) :

Early examples: documentaries were referred to as “actualities” in the 1890s to 1900s, with films that focused on exotic and remarkable locations called “scenics,” and films that focused on (and sometimes recreated) historical or current events called “topicals”

Example of a scenic: Rough Sea at Dover (1896); example of a topical: President McKinley’s Funeral Cortege at Buffalo, New York (1901)

Docudrama: denoting or adding dramatisation to verifiable documentaries

Examples: Cathy Come Home (1966), Death of a President (2006)

Period dramas: which utilise specific epochs or historical events as a narrative backcloth. In these cases, very sizeable liberties are taken, and very large speculations made, for the sake of dramatic emphasis around classical story arcs ex: Nixon (Oliver Stone 1995)

Poetic:

includes films such as Joris Ivens’s impressionistic Rain (1929); Flaherty’s Man of Aran (1934); Basil Wright’s Song of Ceylon (1934); Olympia, by Leni Riefenstahl (1938),

Expository:

addresses the spectator directly, maintains an impression of objectivity, assumes logical and fixed notions of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, and imparts a didactic lesson on a particular subject

Clear narrative voice often presents facts over fiction.

John Grierson’s aegis, most wildlife documentaries and films on historical events.

Participatory:

The filmmaker actively engages within the story that he or she is trying to create

he or she becomes visibly or audibly involved in some way, and acknowledges that involvement’s impact on the subject in front of the often ‘first-person’ (or, seen to be affected by and part of events) camera

Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1960)

Observational:

Captures events and people in a natural setting with minimal interference from the filmmaker

candid’ filming – unobtrusive recording, as if a ‘fly on the wall’, using hand-held, mostly sync-sound camera units.

Popular in 1960s America.

In no way should observational films be mistaken for more ‘objective’ or ‘truthful’ records than other types of documentary.

Reflexive and performative:

Acknowledge and call attention to the processes at work– chiefly the shooting, editing and compilation, but also possibly issues such as funding behind a film’s construction

They bring to the forefront the mechanics and/or intellectual methods of production and flaunt these as integral to a film’s epistemic honesty and hence effectiveness entering into a dialogue about film and a film’s working

Ex: The Man with the Movie Camera (Vertov, 1929

more documentary notes

Key issues in documentary filmmaking (The 'D' word)

documentary = 'non-fiction'

shooting, editing, and compilation, but also possibly issues such as funding

need agreement/evidence between the audience and the filmmaker that the film is 'real'

Represents real life, but through the eyes of filmmaker

thoughts: creativity comes from how filmmaker palce, construct, related those 'reality'

'does not have an absolute ethical and moral obligation to strive, where reasonably possible, for complete fairness and objectivity'

it's still a movie, there're elements which movie has

Types of Documentary (definitions, examples)

social documentary

My Octopus Teacher (docudrama??)

docudrama // mocumentary

propaganda films

ex. newsreels, political docu, prasing nazis in w.w II

cinéma vérité / direct cinema

filming objectively as possible

historical documentary

personal documentary

A Healthy Baby Girl

observational

first-person

world-view

The Thin Blue Line

The story of an innocent man who got in a jail

documentary helps proving the man's innocence

documentary investigation

symbolizing the 'thin line' between the law and life / 'blue' for the cops

pointing out the law/police system

documentary notes again

Key Issues in Documentary Filmmaking (The ‘D’ Word)

“Reality” can be manipulated very easily - not making them as reliable

The film maker can significantly modify the behaviors and manners of the people that they are documenting (Nanook, and Moana (1926)

There can be an element of being “performative”

Documentaries are influenced by who is funding them (bias)

Moral questions: How much distortion or creativity is permissible?

How to balance between historical record and art…

Cinema-verite (a style of filmmaking)

Hybrid of a documentary and drama

United 93

Cathy Came Home (1966)

Death of a President (2006)

The way we look at, react to, and anticipate a film, crucially, has a bearing on how ‘real’ we perceive it to be → e.g. nobody really viewed Titanic as a documentary

Documentary does not have an absolute ethical and moral obligation to strive, where reasonably possible, for complete fairness and objectivity

‘United 93’ - this documentary severs as an example on how it is a retelling of the story but it is only a reconstruction

‘Touching The Void’ - Evidence documentary with original people that were involved

ideological concerns and corporate pressure – should ideally maintain an aloof position outside the sphere of partial political or social activism3

Types of Documentary (definitions, examples)

indexical link to heavily contrived actions and scripted exchanges that once took place in front of the camera

Present varying degrees of fidelity to our own experiences

products of the human psyche and its real-life sources

Present a certain “relationship to history which exceeds the analogical status of its fictional counterpart”

Reflexive documentaries (Driving Me Crazy, 1988)- acknowledge and call attention to the processes at work – chiefly the shooting, editing and compilation, but also possibly issues such as funding – behind a film’s construction

The Social Documentary- examines and present both familiar and unfamiliar peoples and cultures as social activities, emphasizes one or both of the following goals: authenticity in representing how people live and interact, and discovery in representing unknown environments and cultures

The Political Documentary- aimed to investigate and to celebrate the political activities of people as they appear within the struggles of small and large social spheres, sometimes labeled propaganda films but not always

The Historical Documentary- concentrates largely on recovering and representing events or figures in history

Conventional documentary histories assume the facts and realities of a past history can be more or less recovered and accurately represented

Reflexive documentary histories adopt a dual point of view: alongside the work to describe an event is the awareness that film or other discourses and materials will never be able to fully retrieve the reality of that lost history

Ethnographic Cinema- typically about cultural revelations, aimed at presenting specific peoples, rituals, or communities that may have been marginalized by or invisible to the mainstream culture

Anthropological Films- explore different global cultures and peoples, both living and extinct, generally aim to reveal cultures and peoples authentically, without imposing the filmmaker’s interpretations, but in fact they are often implicitly shaped by the perspectives of their makers

Cinéma Vérité- insists on filming real objects, people, and events in a confrontational way, so that the reality of the subject continually acknowledges the reality of the camera recording it, draws particular attention to the subjective perspective of the camera’s rhetorical position

Direct Cinema- the American version of cinéma vérité, more observational and less confrontational than the French practice

Docudrama: documentary + drama, or “dramatized documentary”

Based on historical documents, but not constituting an empirically valid document in and of itself

Personal Documentaries- films that look more like autobiographies or diaries

Documentary Reenactments- use documentary techniques in order to present a reenactment or theatrical staging of presumably true or real events

Mockumentaries- take a much more humorous approach to the question of truth and fact by using a documentary style and structure to present and stage fictional (sometimes ludicrous) realities

We should perhaps take documentary to mean a ‘mode’ of filmmaking, as opposed to a style or genre:

‘a mode of response founded upon the acknowledgement that every photograph is a portrait signed by its sitter.

Stated at its simplest: the documentary response is one in which the image is perceived as signifying what it appears to record; a documentary film is one which seeks, by whatever means, to elicit this response; and the documentary movement is the history of the strategies which have been adopted to this end’ (Vaughan 1999: 58)

The means of a documentary story’s telling will usually have a link to the story’s source, whether via the direct witness testimony of those involved (either the filmmaker, the subjects, or both), or by direct capturing through the lens

Narrative, or the way a story of any kind is told – including its ordering, embellishing and hence its plotting – is structurally important to many documentaries, as it is important in our everyday lives

The Thin Blue Line

While there were interviews with the actual people involved, there were also recreations of events with actors- we don’t fully know what happened but we see the way the filmmaker understands the events

A certain perspective is largely being shown/focused on → creates bias

Certain people involved do not get a voice in the film (Ex: the female cop is never interviewed)

Parts of old movies are used at times (not to depict the incident they are mainly focusing on in the documentary, but it still diverts from reality slightly)

genre film

Definitions: Schatz Reading

Film Genre: “a sort of ‘contract’ between filmmakers and audience” (691)

“A specific grammar system or rules of expression and construction and the individual genre films as a manifestation of these rules” (693)

The grouping

Genres are organized according to processes and rules- can be identified by its rules, components, and function

Genre Film: “an actual event that honors such a contract” (691)

The actual films

Rules: Reinforced expectations that develop after repeatedly experiencing the same types of “perceptual processes” while watching a film (691)

Quality: The “social and aesthetic value” of a film (694)

“Material economy of the studios translates into narrative economy for filmmakers and viewers”

Genre of determinate space: “represents the cultural realm in which fundamental values are in a state of sustained conflict” (698)

The area is entered by a hero who acts on it and then leaves

Genre of indeterminate space: “generally involve a doubled (and thus dynamic) hero in the guise of a romantic couple who inhabit a ‘civilized’ setting” (698)

a doubled hero in the guise of a romantic couple who inhabit a “civilized” setting, relies less on space and more on a value system

Definitions: Hayward Reading

Genre

Genre has to do with institutional discourse and genres can evolve depending on how economic/technological/social/etc views have changed

There’s not a clear generic definition because many genres change and many genre films either have aspects of other genres within them, don’t have all aspects of a certain genre, or view a genre from a different perspective than usual

genres also produce sub-genres, so again clarity is proscribed

There are a set of codes and conventions for each genre but they are not necessarily all followed with every genre film

Capitalism and audience preference can change a genre

“Film genre, therefore, is not as conservative a concept as might at first appear: it can switch, change, be imbricated (an overlapping of genres), subverted”

“genres are therefore motivated by history and society even though they are not simple reflectors of society”

Genres could also be identified by stars. When a star appears on the screen with a repetitive similar image, memories and expectations would be evoked.

Audience, as well as director, are fully aware of genre

The cinema machinery or apparatus regulates the different orders of subjectivity including that of the spectator

Industry can control ‘the effects that its products produce’

Genre Major Characteristics: Schatz Reading

Fundamental structural components (691)

Plot

Character

Setting

Thematics

Style

Film Genre as a static and dynamic system (691)

Static system: Reuses “familiar formulas” to navigate and “reexamine” cultural conflicts

“Rules, components, and function” (692)

Dynamic system: Is constantly evolving to keep up with “changes in cultural attitudes, new influential genre films, the economics of the industry,” etc.

“Individual members which comprise the species” (692)

Film genres have a formula but that formula can change and evolve based on cultural change

Characteristics shared by all films and genres (694)

Can be examined through fundamental narrative components: plot, setting, and character (695)

Recognizing dramatic conflicts that “we associate with specific patterns of action and character relationships” (695)

Attempt to resolve some sort of threat to the social order (697)

Characteristics shared by all films within a genre (694)

Generic character as a “physical embodiment of an attitude, a style, a worldview, of a predetermined and essentially unchanging cultural posture” (696)

Plot structure of a genre film (699):

Establishment

Animation

Intensification

Resolution

Characteristics that set one genre film apart from the rest of its genre (694)

Genres of determinate and indeterminate space

Determinate space: entered by a hero, who acts upon it, and finally leaves (698)

Values of social integration

Indeterminate space: depend less on heavily coded place than on a highl conventionalized value system

Values of social order

Plot structure

Resolution

“The most significant feature of any generic narrative”

“In most Hollywood genre films, plot development is effectively displaced by setting and character”

Plot structure of a genre film:

Establishment of the community and conflict

Animation of the conflict through the actions and attitudes of the characters

Intensification of the conflict by conventional situations and confrontations until the conflict reaches crisis proportions

Resolution of the crisis

Genre films establish a sense of continuity between our cultural past and present and attempt to eliminate the distinctions between them

“Philosophical or ideological conflicts are translated into emotional terms and are resolved accordingly”

Schatz Quotes

“Grammar in language is absolute and static, especially unchanged by the range and abuses of everyday language. In the cinema, however, individual genre films seem ot have the capacity to affect the genre – an utterance has the potential to change the grammar that governs it.”

“A genre, then, represents a range of expression for filmmakers and a range of experience for viewers” (695, original emphasis).

“To figure out a film’s quality (social and aesthetic value) we need to see it in relation to the systems that inform it”

“Nevertheless, each genre has a static nucleus that manifests its thematic oppositions or recurring cultural conflicts that manifests its thematic oppositions or recurring cultural conflicts” (700)

“Genre films not only project an idealized cultural self-image, but they project it into a realm of historical timelessness” (702).

Hayward Quotes

Genre “refers to the role of specific institutional discourses that feed into and form generic structures. In other words, genre must be seen also as part of a tripartite process of production, marketing (including distribution and exhibition) and consumption.”

Genres are not static but evolve with time → they’re “both conservative and innovative insofar as they respond to expectations that are industry- and audience-based”

We should “be aware of the dangers of reductionism inherent in an ideological approach to genre”

“a film is rarely generically pure, which is not surprising if we consider film’s heritage which is derivative of other forms of entertainment”

“genre serves as a barometer of the social and cultural concerns of cinema-going audiences”

“Genres also act as vehicles for stars. But stars, too, act as vehicles for genres.”

Genre produces “constructs of sexuality, which are based around images of the active male versus the passive female, independence versus entrapment (i.e. marriage and family)”

“Genres have codes and conventions with which the audience is as familiar as the director (if not more so)”

“genre can be identified by the iconography and conventions operating within it”

“But genre is also a shifting and slippery term so it is never fixed and, either through economic and historical exigencies, or through intentional parodic practice, is in a constant process of change.”

Social motives behind making a genre: There are needs that a film needs to fulfill, motivated by history and society, even if they do not directly reflect society

genre notes continued

Genres are not unchanging and evolve along with social/political trends

Genres reflect the current beliefs/sentiments of the time period when they are released (after 9/11 the epic genre rose to popularity)

They confirm and exacerbate political anxieties (Cold War films)

Genres are tied to commercial marketing and were originally used to advertise films

All must fulfill needs whether that be socially (Western/Gangster films) or politically (Cold War/ WW1 & 2 films)

Western movie cowboys evolved from agents for law and order into a violent or rebellious character regardless of film or painting they were used to promote American national identity

They help categorize, distinguish, categories for awards. Genres also encourage filmmakers to produce films within particular genres

Individual films can influence a genre, while viewers can change the genre once it is released to the public

Film genre encourage audiences' expectations: audience look forward to certain points within a genre and if the films doesn't show those points, it'll disappoint the audience.

Final Genre notes

“A film genre can be examined in terms of its fundamental structural components: plot, character, setting, thematics, style,”

Using analogies to explain film genres

Focusing on verbal communication as an analogy

Using analogy to express difference of film genre and genre film

“We might think of the film genre as a specific grammar or system of rules of expression and construction and the individual genre films as a manifestation of these rules”

Film genre as a broad category; genre film as films within the category

Individual films can impact their film genre

Difference in language, everyday usage of grammar does not change grammar

Aspects work towards a film genre

Certain settings, characters, etc.

Expectations for viewers in the film genre

Especially expecting a resolution

What leads people to come back?

Hayward

Film genre as product of time and culture

Not only reflection of content but of the audience

“Ideologically inflected”

Genre as a definable group; a film may not always be defined as such

“Principal genres”

Narrative film, avant-garde film, documentary

Sub-genres as film genres

Films can “fail” when they don’t meet the expectations of a film genre

Dangers of the genre

Genre can become inverted: can lead to disappointment, irony, comedic effect, etc.,

Emphasizing genre as not fixed, always changing.

narrative form

A type of filmic organization in which the parts relate to one another through a series of causally related events taking place in time and space.

Principles of Narrative Form

-film shapes our expectations by summoning up curiosity, suspense, surprise, and other emotional qualities.

-Spectators approach narrative films with certain expectations, whether they're familiar with the story (e.g., a book adaptation or sequel) or not.

-Common expectations: characters, interrelated actions, a series of connected incidents, and resolution of conflicts.

-Spectators are actively engaged in the process of making sense of the film, recalling information, and anticipating what happens next.

Narrative Structure (Cause and Effect, Time, and Space)

● A narrative is a sequence of events connected by cause and effect, occurring in time and space.

● Events need to be linked causally and spatially to be understood as a narrative (e.g., a man’s fight with his boss leads to his sleeplessness, which causes him to break a mirror, and the phone call resolves the situation).

Role of Causality, Time, and Space

● Narratives are shaped by how events are causally connected and how they unfold over time and in specific locations.

● Example: The fight causes sleeplessness, which leads to breaking the mirror, and the phone call resolves the issue the next day.

Graphic and Rhythmic Editing

● Abstract and Associational Form:

○ Some films focus on the graphic and rhythmic aspects of editing, rather than

narrative continuity. In these films, shots are connected based on visual or

rhythmic qualities, independent of the story’s time and space.

○ Stan Brakhage: An experimental filmmaker, Brakhage used graphic qualities

(light, texture, and shape) to link shots in films like Anticipation of the Night and

Scenes from Under Childhood.

○ Bruce Conner: Films like Cosmic Ray and A Movie mix newsreel footage, old

film clips, and black frames, relying on movement, direction, and speed rather

than narrative.

● Emphasis on Rhythm:

○ Some non narrative films prioritize editing rhythm over the visual content of the shots. For example, single-frame films, where each shot lasts just one frame, focus entirely on rhythm.

○ Famous examples include Peter Kubelka’s Schwechater and Robert Breer’s Fist Fight, where editing rhythm is the primary concern.

○ Ballet Mécanique (discussed in Chapter 10) is another example, where editing rhythm is synchronized with abstract graphic

Graphic and Rhythmic Editing in Narrative Films

● Busby Berkeley’s Dance Numbers:

○ In films like 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade, Gold Diggers of

1935, and Dames, Busby Berkeley used editing to highlight complex choreography and geometric patterns, occasionally halting the narrative for these abstract dance sequences.

● Montage Sequences:

○ These types of sequences can also be found in narrative films. For example, in

Maytime, rapid editing and superimpositions summarize an opera singer’s triumphs. In Citizen Kane, a similar montage is used, but it ironically portrays failure.

○ In Spider-Man, CGI and dissolves are used to link shots in a montage sequence, showing Peter Parker's process of designing his superhero costume.

Thin Blue Line

The Thin Blue Line (1988) – Directed by Errol Morris

A groundbreaking documentary that investigates the wrongful conviction of Randall Dale Adams for the murder of a Dallas police officer.

Uses reenactments, stylized cinematography, and multiple perspectives to question the notion of objective truth.

Ultimately played a role in exonerating Adams, showing how documentary storytelling can impact real-world justice.

1. Objectivity of the Legal SystemKey Arguments:

The legal system is often assumed to be objective, but Morris exposes its flaws.

Law enforcement and prosecutors construct narratives to serve their own interests rather than uncover absolute truth.

The reliance on eyewitness testimony—which can be flawed or manipulated—plays a crucial role in wrongful convictions.

The film critiques confirmation bias: authorities settled on Adams as the suspect early on and ignored contradictory evidence.

Evidence from the Film:

Testimonies in the film reveal contradictions and shifting stories from witnesses.

The police relied on the testimony of David Harris, a juvenile delinquent whose credibility was questionable.

Morris presents evidence showing that Adams was wrongly convicted due to misleading testimony and prosecutorial bias.

2. Questioning Objectivity in Documentary FilmmakingKey Arguments:

Traditional documentaries aim to present "objective" reality, but Morris actively constructs a narrative.

He guides the audience toward a conclusion rather than simply presenting raw facts.

Uses techniques more common in fiction filmmaking—like non-linear storytelling, cinematic visuals, and dramatic reenactments.

Evidence from the Film:

The film lacks a conventional omniscient narrator, relying instead on interviews and cinematic storytelling.

Morris’s editing choices shape how viewers interpret the case, making the audience reconsider their assumptions.

The reenactments visualize alternative versions of events, showing how different perspectives shape "truth."

3. Different Points of View & Larger Questions in DocumentaryKey Arguments:

Morris highlights conflicting perspectives, showing how individuals remember and recount events differently.

Raises deeper questions: Can a documentary ever present an absolute truth, or is truth always subjective?

Challenges the idea that documentary filmmaking is about passively recording reality—instead, it actively constructs meaning.

Evidence from the Film:

Different witnesses offer contradictory versions of the crime, demonstrating how reality is shaped by perception and bias.

Morris’s interview structure allows subjects to reveal their biases and unreliability, rather than presenting a single authoritative viewpoint.

The documentary asks: Is truth created rather than simply discovered?

4. Who is Narrating the Story?Key Arguments:

Traditional documentaries often have a voiceover narrator, guiding the audience toward an interpretation.

The Thin Blue Line lacks a conventional narrator, instead relying on interviews, music, and reenactments to tell its story.

The filmmaker himself (Morris) acts as an invisible guide—his choices shape how we understand the film’s events.

Evidence from the Film:

Morris frames the film as an investigation, leading viewers through the clues like a detective story.

The absence of a conventional narrator forces audiences to piece together the truth themselves.

The soundtrack (by Philip Glass) adds emotional weight to the narrative, shaping how viewers feel about different moments.

5. Objectivity of MemoryKey Arguments:

Memory is inherently subjective—witnesses remember things differently based on their personal biases and experiences.

The documentary shows how eyewitness testimony, often relied upon in legal cases, is unreliable.

Morris’s use of conflicting testimonies demonstrates how perception alters recollection.

Evidence from the Film:

Witnesses contradict one another, showing how personal narratives evolve over time.

The reenactments highlight variations in how the crime was remembered.

Raises the question: Can memory ever be truly objective, or is it always filtered through individual experience?

6. Re-enactment – A Space in Documentary or Just Realism?Key Arguments:

Morris revolutionized documentary filmmaking by incorporating dramatized reenactments, which were rare at the time.

Raises the question: Are reenactments a legitimate tool for truth-telling, or do they blur the line between fiction and nonfiction?

The stylized cinematography and slow-motion shots create a film noir aesthetic, making the documentary feel more like a crime thriller.

Evidence from the Film:

The film doesn’t simply show reenactments—it replays them in different variations, emphasizing subjectivity.

The visual style of the reenactments (dramatic lighting, slow-motion) enhances emotion and tension.

This challenges traditional realism in documentary—does adding cinematic elements distort truth or reveal deeper insights?

Final Thoughts & Exam Tips

Morris uses narrative construction, conflicting testimonies, reenactments, and stylized storytelling to critique objectivity in both documentary filmmaking and the legal system.

The film ultimately demonstrates how reality is shaped by perspective, rather than being an absolute, fixed truth.

"The Thin Blue Line challenges traditional notions of objectivity, both in documentary filmmaking and the legal system, by illustrating how truth is constructed through narrative, perspective, and memory.

causality in narrative form

1. Definition of Causality in Narratives

Causality refers to the cause-and-effect relationships that drive a story forward. It answers the question: Why does this happen? Every event in a well-structured narrative is either a direct result of a previous event or a catalyst for future events. This logic helps create coherence, emotional engagement, and dramatic tension.

2. Types of Causality in Narrative Structure

Linear Causality: Events occur in a straightforward sequence—cause leads to effect in chronological order. This is the most traditional form found in classical storytelling.

Nonlinear Causality: The timeline may be fragmented, but cause-and-effect relationships still exist. Some narratives present events out of order, requiring the audience to piece together causation (e.g., films like Mementoor Inception).

Psychological Causality: Characters' emotions, motivations, and internal conflicts drive their actions. Instead of external forces dictating events, personal choices shape the plot.

Symbolic or Thematic Causality: In more abstract narratives, causality is suggested rather than explicitly shown. Events may be connected thematically rather than through direct cause-and-effect.

3. Causality in Film

Editing & Montage: Filmmakers manipulate causality through editing, juxtaposing images to imply connections. Soviet montage theory uses rapid cuts to create meaning beyond direct cause-and-effect relationships.

Sound & Visual Cues: In film, audio cues or visual framing can reinforce causal links. For example, a thunderclap following a character’s decision might signal impending doom.

Foreshadowing & Flashbacks: Techniques like foreshadowing set up future causal events, while flashbacks reveal hidden causes behind present actions.

4. Causality & Genre

Mystery & Thriller: Cause-and-effect is crucial in mystery narratives, where clues lead to discoveries and resolutions.

Fantasy & Science Fiction: These genres often explore alternative causal structures, such as time loops, paradoxes, or fate-driven events.

Surrealism & Experimental Narratives: Some films and stories disrupt causality intentionally.

Graphic/ Rhythmic/ Spatial/ temporal editing

1. Graphic Editing

Graphic editing focuses on visual continuity or contrast between shots. It considers elements like color, shape, composition, and movement.

Example: Psycho (1960) – The famous shower scene uses graphic matches between Marion’s eye and the shower drain, reinforcing the horror and tragedy of the moment.

2. Rhythmic Editing

Rhythmic editing controls the pacing of a scene by adjusting the duration of shots. Faster cuts create tension, while slower cuts allow reflection.

Example: Whiplash (2014) – The drumming sequences use rapid cuts to match the intensity of the music, heightening the emotional impact.

3. Spatial Editing

Spatial editing establishes relationships between different locations or perspectives, often using techniques like cross-cutting or the Kuleshov effect.

Example: The French Connection (1971) – The car chase scene masterfully uses spatial editing to maintain clarity and tension, showing multiple perspectives.

4. Temporal Editing

Temporal editing manipulates time within a film, using techniques like flashbacks, ellipses, or parallel timelines.

Example: Memento (2000) – The film’s fragmented timeline forces viewers to piece together events, making temporal editing a central storytelling device

discontinuity editing examples

I Tonya, Chungking express