Operating Systems Midterm 1

1/38

Earn XP

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

39 Terms

Process

abstraction to virtualize CPU

uses time-sharing in OS to switch between processes

Limited Direct Execution

uses system calls to run access devices from user mode

context-switch using interrupts for multi-tasking

Metrics/Policies: TAT (turnaround time)

completion_time - arrival_time

FIFO: first come first served

SJF: shortest job first

STCF: shortest completion time first

Metrics/Policies: response time

first_run_time - arrival time

RR: round robin with time slice

minimizes response time but could increase turnaround

The best scheduling algorithm for maximizing response time is Shortest Job Completion First STCF. T/F?

False

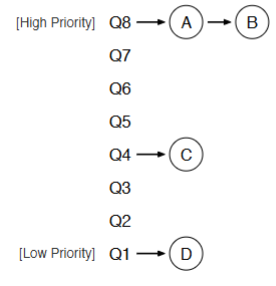

Multi-Level Feedback Queue

If priority(A) > Priority(B), A runs

If priority(A) == Priority(B), A & B run in RR

Processes start at top priority.

If job uses whole slice, demote process. If not, stay at level.

Mechanism (CPU)

process abstraction

system call for protection

context switch to time-share

Policy (CPU)

Metrics (TAT, repsonse time)

Balance using MLFQ

scheduling

How to build a pipe for interprocess communication?

int a[2]; pipe(a);

What does a system call do?

It allows a user process to access certain elements otherwise restricted in user mode.

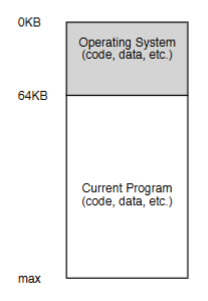

Uniprogramming

one process runs at a time

Multiprogramming

the ability of keeping a high number of processes in memory ready to be scheduled in the CPU

Multiprogramming Goals

Transparency: process is unaware of sharing

Protection: cannot corrupt OS or other process memory

Efficiency: do not waste memory or slow down processes

Sharing: enable sharing between cooperating processes

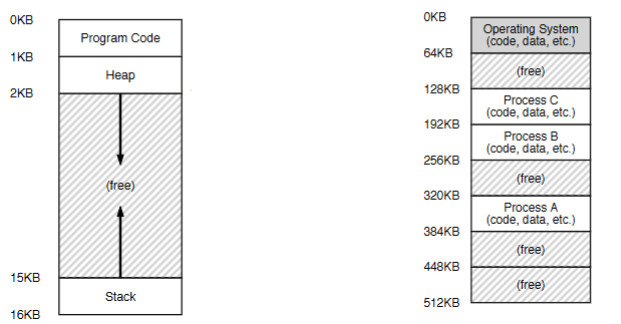

Address Space

Static: Code and some global variables

Code: where instructions live

Dynamic: Stack and Heap

Stack: contains local variables, arguments to routines, return values, etc.

Heap: containts malloc’d data dynamic data structures (it grows downward)

Find the location for these variables: x, main, y, z, *z. Possible locations: static data/code, stack, heap.

int x;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

int y;

int* z = malloc(sizeof(int));

}x = static data/code

main = code

y = stack

z = stack

*z = heap

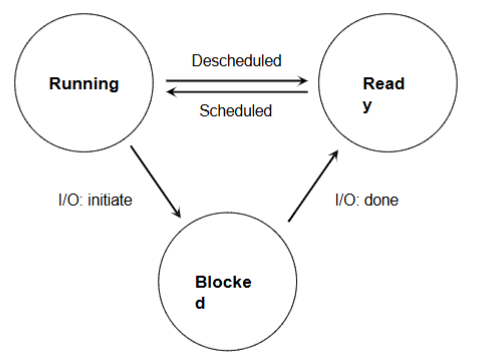

A process may transition to the Ready state by which of the following actions?

a. completion of an I/O event

b. awaiting its turn on the CPU

c. newly-admitted process

d. all of the above

d. all of the above

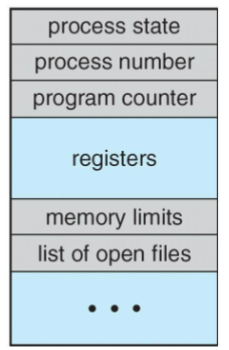

Process Control Block

includes information on the process’s state (running, waiting, etc.)

BeOS keeps track of a small amount of information about each running process in a data structure called the “process list”. However, to keep the amount of information in the process list small, Binus reduced the number of states a process could be in. Specifically, in BeOS, there are only two states a process can be in: RUNNING and BLOCKED. What process state found in most OSes was removed from BeOS?

READY

To keep scheduling simple in BeOS, Binus chose the FIFO policy (first in, first out) to decide which process to run. Which one of the following statements about FIFO scheduling is true?

-a It reduces average turnaround time

- b It reduces average response time

- c It suffers from the “convoy” problem

- d It is a preemptive scheduling policy

- e It is different from the FCFS policy

c. It suffers from the “convoy” problem. A single long job can make jobs behind it queue up and thus have worse response/turnaround times.

Assuming the BeOS FIFO scheduling approach, calculate the turnaround time for job B, assuming the following: job A arrives at time T=0, and needs to perform 10 seconds of compute; job B arrives at time T=5, and needs to perform 20 seconds of compute; job C arrives at time T=10, and needs to perform 5 seconds of compute. The jobs perform no I/O.

B arrives for T = 5, but A still runs for 5 more seconds. Thus, B starts running at T = 10. B then runs for 20 seconds. So, B’s TAT is 30 - 5 = 25.

The DOS scheduler is based on a random policy. Specifically, every 10 milliseconds (ms), a timer interrupt goes off, and DOS picks a random process to run. This approach is most similar to which following policy?

Round Robin

With the DOS random scheduling policy, assume you have two jobs enter the system at the same time, each of which needs to run for 30 milliseconds. Assume again a 10 ms timer interrupt. What is the best case average response time for these two jobs?

The best case for response time would be job A runs immediately (response time: 0), and then, at the first tick (10 ms later), job B runs (response time: 10). Thus, average is 5.

With the DOS random scheduling policy, assume you have two jobs enter the system at the same time, each of which needs to run for 30 milliseconds. Assume again a 10 ms timer interrupt. What is the worst case average turnaround time for these two jobs?

The worst turnaround occurs when each job runs for as long as possible. Thus, ABABAB, with each little chunk being 10 ms. The turnaround for A is 50 and B is 60, with average 55.

DOS uses the MLFQ (multi-level feedback queue) scheduler. However, it changes some rules. The biggest change: new processes are added to a random queue (not the topmost one). What is the biggest effect this will have?

Sometimes, short-running jobs won’t get serviced quickly, thus decreasing interactivity.

Minux uses kernel mode, user mode, and a new mode called “supervisor” mode. When a user program runs in “supervisor” mode, it is still restricted (like user mode), but can do the following: change the length of the timer interrupt interval, including turning it off. Overall, would you say that supervisor mode (choose one):

- a Helps ensure streamlined round-robin scheduling

- b Ensures more efficient, application-aware timing interrupts

- c Better integrates scheduling and virtual memory mechanisms

- d Limits the OS’s ability to retain control of the machine if user code runs in supervisor mode

- e None of the above

d. Limits the OS’s ability to retain control of the machine if user code runs in supervisor mode

The Minux scheduler uses a new scheduler called “highest process ID (PID) first” (i.e., the job with the highest PID always runs, and to completion). Assume job PID=1 arrives at time T=0, with length 10; PID=2 arrives at T=2, length=6; PID=3 arrives at T=4, with length 4. What is the average response time of this approach in this example?

RT for PID=1: 0 - 0 = 0

RT for PID=2: 8 - 2 =6

RT for PID=3: 4 - 4 = 0

Average RT = 2

ZOS uses a new type of scheduler called a proportional-share scheduler. This scheduler makes sure each process gets a certain amount of CPU time, based on how many “tickets” it has. For example, if process A has 2 tickets, and process B has 1, A should get twice as much CPU time as B. Note that a process cannot change how many tickets it has, and all jobs only use the CPU (there is no I/O in this example). Which of the following traces (which each show which job was scheduled at each quantum over time) does not show the behavior of a proportional-share scheduler?

- a AABAABAABAABAA

- b ABABABABABAB

- c AAAAAAAAAABBBBB

- d ABBBABBBABBBABBB

- e None of the above (they all could be traces from a proportional share scheduler)

e. None of the above

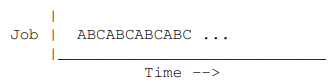

The picture here shows the scheduling of two processes: A, B, and C over time. Let’s look at it. (McFlub now draws this on the board). “As you can clearly see, this is the behavior of a lottery scheduler, rotating between A, B, and C randomly. And you can trust the results: I traced this behavior on a lottery scheduler I built late last night.” Is McFlub correct?

Probably not a lottery scheduler, could be a very rare random behavior

“Shortest Time to Completion First is a great policy, if you care about response time. But today we’re going to worry about turnaround time. Let’s compute the turnaround times for STCF for these three jobs, which arrive at about the same time: Job A (which needs to run for 10 time units), Job B (needs 20), and Job C (needs 30). Let’s assume this happens when the jobs are run: ABBCCC The Turnaround for A is thus 0, 10 for B, and 20 for C. Thus, average turnaround for STCF is 10, which is great. See, I told you.” Is McFlub correct?

No, STCF is good for turnaround not response time. TAT for A, B, and C, are 10, 30, and 60, with average of 33.3.

“The Multi-level Feedback Queue has an intricate set of rules, used to build up a scheduler that achieves many different goals. It starts with a set of queues, ordered from highest to lowest priority. And then it adds rules for moving jobs among the queues. Let’s look at the rules, and see if they make sense:

- If Priority(A) > Priority(B), A runs (B doesn’t).

- If Priority(A) == Priority(B), A and B run in round-robin style.

- When a job enters the system, it is assigned a random priority and put in the queue corresponding to that priority.

- Once a job uses up its time allotment at a given level (regardless of how many times it has given up the CPU), its priority is reduced (i.e., it moves down one queue).

Is McFlub correct?

The third rule is wrong. Jobs enter at top priority not random.

A program’s main function is as follows:

int main(int arc, char *argv[]){

char *str = argv[1];

while(1)

printf("%s", str);

return 0;

}Two processes, both running instances of this program, are currently running (you can assume nothing else of relevance is, except perhaps the shell itself). The programs were invoked as follows, assuming a “parallel command” as per project 2a (the wish shell): wish> main a && main b. Below are possible (or impossible?) screen captures of some of the output from the beginning of the run of the programs. Which of the following are possible?

1. abababab ...

2. aaaaaaaa ...

3. bbbbbbbb ...

4. aaaabbbb ...

5. bbbbaaaa ...

When two processes run in parallel, their outputs can be arbitrarily interleaved. Thus, any mix of ’a’ and ’b’ is possible.

1. abababab ... A. Possible

2. aaaaaaaa ... A. Possible

3. bbbbbbbb ... A. Possible

4. aaaabbbb ... A. Possible

5. bbbbaaaa ... A. Possible

Here is source code for another program called increment.c:

int value = 0;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

while(1) {

printf("%d", value);

value++:

}

return 0;

}While increment.c is running, another program, reset.c, is run once as a separate process. Here is the source code of reset.c:

int value = 0;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

value = 0;

return 0;

}Which of the following are possible outputs of the increment process?

6. 012345678 ...

7. 012301234 ...

8. 012345670123 ...

9. 01234567891011 ...

10. 123456789 …

6. 012345678 ... A. Possible

7. 012301234 ... B. Not Possible (value is reset, but how?)

8. 012345670123 ... B. Not Possible (value is reset, but how?)

9. 01234567891011 ... A. Possible (value not reset; it’s just “9 10 11” squished together)

10. 123456789 … B. Not Possible (increment starts at 0)

Processes exist in a number of different states. We’ve focused upon a few (Running, Ready, and Blocked) but real systems have slightly more. For example, xv6 also has an Embryo state (used when the process is being created), and a Zombie state (used when the process has exited but its parent hasn’t yet called wait() on it). Assuming you start observing the states of a given process at some point in time (not necessarily from its creation, but perhaps including that), which process states could you possibly observe? Note: once you start observing the process, you will see ALL states it is in, until you stop sampling.

16. Running, Running, Running, Ready, Running, Running, Running, Ready

17. Embryo, Ready, Ready, Ready, Ready, Ready

18. Running, Running, Blocked, Blocked, Blocked, Running

19. Running, Running, Blocked, Blocked, Blocked, Ready, Running

20. Embryo, Running, Blocked, Running, Zombie, Running

16. Running, Running, Running, Ready, Running, Running, Running, Ready A. Possible (process has been running, then gets descheduled, then runs again and is descheduled again).

17. Embryo, Ready, Ready, Ready, Ready, Ready A. Possible (process is created and waits to run).

18. Running, Running, Blocked, Blocked, Blocked, Running B. Not Possible (process must be READY before it runs again).

19. Running, Running, Blocked, Blocked, Blocked, Ready, Running A. Possible (process runs, then blocks on I/O, then unblocks [becomes READY]), then runs).

20. Embryo, Running, Blocked, Running, Zombie, Running B. Not Possible (no state ever beyond Zombie).

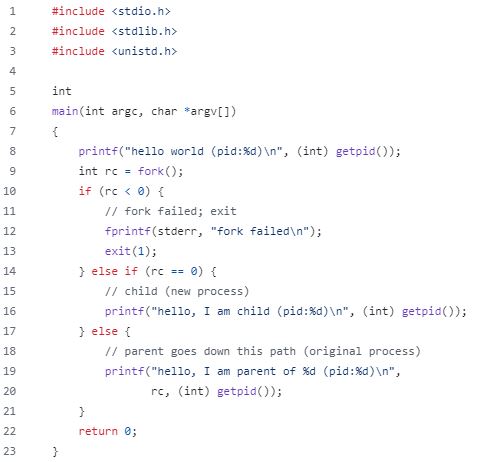

The following code is shown to you:

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

printf("a");

fork();

printf("b");

return 0;

}Assuming fork() succeeds and printf() prints its outputs immediately (no buffering occurs), what are possible outputs of this program?

Assuming fork() might fail (by returning an error code and not creating a new process) and printf() prints its outputs immediately (no buffering occurs), what are possible outputs of the same program as above?

21. ab

22. abb

23. bab

24. bba

25. a

fork() creates a new process (when it works, as it does here) which is a copy of the existing process. In this case, because printf() takes place immediately, ’a’ prints in the child, and then each the parent and child print ’b’. Thus, ’abb’ is the output.

ab, abb

Assume the program /bin/true, when it runs, never prints anything and just returns 0 in all cases.

int main(int arc, char *argv[]){

int rc = fork();

if (rc == 0) {

char *my_argv[] = { "/bin/true", NULL };

execv(my_argv[0], my_argv);

printf("1");

} else if (rc > 0) {

wait(NULL);

printf("2");

} else {

printf("3");

}

return 0;

}Assuming all system calls succeed and printf() prints its outputs immediately (no buffering occurs), what outputs are possible?

Assuming any of the system calls above might fail (by not doing what is expected, and returning an error code), what outputs are possible?

The common case is that the child

(rc==0)case exec’s/bin/true; it will thus never print 1. Theparent

(rc>0)prints 2 after waiting for the child to complete.If the fork() succeeds but the execv() fails, the child will return from execv(), the child will print ’1’. Thus, ’12’ is possible (the ’2’ only prints after the ’1’ because of the wait() - note that ’21’ is possible here if the wait() fails. If fork() fails

(rc<0), just ’3’ is printed. Any output with ’2’ and ’3’ is not possible (such as 123 or 23), because that means the fork() must have succeeded and failed at the same time.

Assume, for the following jobs, a FIFO scheduler and only one CPU. Each job has a “required” runtime, which means the job needs that many time units on the CPU to complete.

Job A arrives at time=0, required runtime=X time units

Job B arrives at time=5, required runtime=Y time units

Job C arrives at time=10, required runtime=Z time units

Assuming an average turnaround time between 10 and 20 time units (inclusive), which of the following run times for A, B, and C are possible?

41. A=10, B=10, C=10

42. A=20, B=20, C=20

43. A=5, B=10, C=15

44. A=20, B=30, C=40

45. A=30, B=1, C=1

41. A=10, B=10, C=10 A: 10-0=10, B: 20-5=15; C: 30-10=20. Avg: 15 A. Possible

42. A=20, B=20, C=20 A: 20-0=20; B: 40-5=35; C: 60-10=50; Avg: 35 B. Not Possible

43. A=5, B=10, C=15 A: 5-0=5; B: 15-5=10; C: 30-10=20; Avg: 11.67 A. Possible

44. A=20, B=30, C=40 A: 20-0=20; B: 50-5=45; C: 90-10=80; Avg: 48.33 B. Not Possible

45. A=30, B=1, C=1 A: 30-0=30; B=31-5=26; C=32-10=22; Avg: 26 B. Not Possible

Assume the following schedule for a set of three jobs, A, B, and C:

A runs first (for 10 time units) but is not yet done

B runs next (for 10 time units) but is not yet done

C runs next (for 10 time units) and runs to completion

A runs to completion (for 10 time units)

B runs to completion (for 5 time units)

Which scheduling disciplines could allow this schedule to occur?

46. FIFO

47. Round Robin

48. STCF (Shortest Time to Completion First)

49. Multi-level Feedback Queue

50. Lottery Scheduling

46. FIFO B. Not Possible, FIFO would run to completion, the schedule above does not

47. Round Robin A. Possible, Switch jobs in RR order every 10 time units.

48. STCF (Shortest Time to Completion First) B. Not Possible, A is run to completion before B, which is shorter.

49. Multi-level Feedback Queue A. Possible, Can act like RR. Could have stayed on same queue, or switch queues.

50. Lottery Scheduling A. Possible, With lottery (random), anything is possible.

The Multi-level Feedback Queue (MLFQ) is a fancy scheduler that does lots of things. Which of the following things could you possibly say (correctly!) about the MLFQ approach?

51. MLFQ learns things about running jobs

52. MLFQ starves long running jobs

53. MLFQ uses different length time slices for jobs

54. MLFQ uses round robin

55. MLFQ forgets what it has learned about running jobs sometimes

All possible besides 52. MLFQ starves long running jobs. By bumping priority on occasion, MLFQ avoids starvation.

Given the following piece of code, what will be the value returned to the variable rc after executing the fork() instruction for the parent: ___, and for the child: _____ processes? Assume the process ID of the parent is: 25.

rc = 26 (parent), rc=0 (child)