Ch 27: Development & Heredity

1/34

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

35 Terms

What are the phases of the prenatal period? Approximately how long is a "full term" pregnancy?

The prenatal period is divided into three main stages:

Pre-embryonic Period (Weeks 1-2):

Begins with fertilization, forming a zygote.

The zygote undergoes mitotic divisions to become a blastocyst, which implants in the uterus.

Embryonic Period (Weeks 3-8):

The conceptus is now called an embryo.

This stage involves the formation of rudimentary organ systems.

Fetal Period (Weeks 9-38):

The embryo is now referred to as a fetus.

The fetus grows and its organ systems mature to function independently at birth.

Full Term Pregnancy

A "full term" pregnancy typically lasts about 40 weeks or 280 days, starting from the mother's last menstrual period.

What does the term "conceptus" mean? How is this term different than "fetus"?

Conceptus: The term "conceptus" refers to the developing offspring from the moment of fertilization until birth. It encompasses all stages of prenatal development, including the pre-embryonic, embryonic, and fetal periods. During the pre-embryonic period, the conceptus is a blastocyst, and during the embryonic period, it is referred to as an embryo [1][3].

Fetus: The term "fetus" specifically refers to the stage of development from week 9 until birth. During this fetal period, the conceptus grows larger and its organ systems develop to function independently from the mother. The transition from embryo to fetus marks the beginning of this stage [1][2].

Key Differences:

Stage of Development: "Conceptus" is a broader term that includes all stages, while "fetus" is specific to the later stage of development.

Developmental Changes: The fetus undergoes significant growth and organ development, preparing for life outside the womb.

What must happen to a sperm cell before it is able to begin the process of fertilization?

Before a sperm cell can begin the process of fertilization, it must undergo several key changes and processes:

Capacitation: This is a series of functional changes that make the sperm fully motile and modify its plasma membrane so it can fuse with the secondary oocyte's plasma membrane. Capacitation occurs as components of the seminal fluid and fluids in the female reproductive tract weaken the sperm's plasma membrane.

Acrosomal Reaction: The sperm must release enzymes from the acrosome, a membrane-enclosed sac on the head of the sperm. These enzymes help the sperm penetrate the layers surrounding the secondary oocyte, such as the corona radiata and the zona pellucida.

Binding to the Oocyte: Once the sperm penetrates these layers, it binds to the plasma membrane of the secondary oocyte. This binding triggers changes that prevent other sperm from entering.

What "zones" surrounding an egg cell must a sperm cell go through before being able to fuse with the egg cell?

Before a sperm cell can fuse with an egg cell, it must pass through two main "zones" surrounding the egg:

Corona Radiata: This is the outermost layer, consisting of granulosa cells that surround the secondary oocyte. The sperm must penetrate this layer using a combination of its movements and enzymes like hyaluronidase, which are released during the acrosomal reaction.

Zona Pellucida: Located just beneath the corona radiata, this is a glycoprotein layer that contains sperm-binding receptors. When a sperm binds to these receptors, it triggers the acrosomal reaction, releasing enzymes that help digest a path through the zona pellucida.

Once the sperm successfully penetrates these layers, it can bind to the plasma membrane of the secondary oocyte, leading to fertilization. This process ensures that only one sperm fertilizes the egg, preventing polyspermy, which would be fatal to the zygote.

What is the acrosomal reaction? What is the cortical reaction?

Acrosomal Reaction

The acrosomal reaction is a crucial step in fertilization. It involves the release of enzymes from the acrosome, a membrane-enclosed sac at the head of the sperm. These enzymes, including hyaluronidase and acrosin, help the sperm penetrate the protective layers surrounding the secondary oocyte, such as the corona radiata and zona pellucida. This reaction is triggered when the sperm binds to receptors in the zona pellucida, allowing calcium ions to enter the sperm, which initiates the release of acrosomal enzymes. Multiple sperm are needed to release enough enzymes to penetrate these layers, highlighting the importance of a sufficient sperm count for successful fertilization.

Cortical Reaction

The cortical reaction occurs after a sperm successfully enters the secondary oocyte. This reaction involves the release of enzymes from cortical granules within the oocyte, which destroy sperm-binding receptors on the oocyte's surface. This process prevents additional sperm from entering, thus avoiding polyspermy, which would result in a triploid zygote and is fatal. The cortical reaction ensures that only one sperm fertilizes the oocyte, allowing normal development to proceed.

What is polyspermy, and how is it prevented during fertilization? Why is it so important that polyspermy is prevented?

Polyspermy and Its Prevention

Polyspermy occurs when more than one sperm fertilizes an egg, leading to a triploid zygote with three sets of chromosomes, which is fatal. To prevent polyspermy, the cortical reaction is triggered upon sperm entry. This reaction involves the release of enzymes from cortical granules in the oocyte, destroying sperm-binding receptors and preventing additional sperm from entering.

Importance of Preventing Polyspermy

Preventing polyspermy is crucial because a triploid zygote cannot develop properly, resulting in the failure of embryonic development. Ensuring only one sperm fertilizes the egg maintains the correct diploid chromosome number, essential for viable offspring.

What happens to the nuclei of the sperm and egg cells during fertilization?

Fertilization Process:

During fertilization, the nuclei of the sperm and egg cells undergo several transformations to form a zygote. Here's a simplified breakdown of the process:

Sperm Entry: The sperm nucleus enters the cytoplasm of the secondary oocyte, swelling to form the male pronucleus.

Completion of Meiosis II: The secondary oocyte completes meiosis II, transforming into an ovum. Its nucleus swells to form the female pronucleus.

Formation of Spindle: A spindle forms between the male and female pronuclei, allowing the chromosomes from both pronuclei to intermix.

These steps ensure the correct number of chromosomes in the zygote, which is crucial for the development of a new individual.

Approximately how long post-ovulation is an egg cell able to be fertilized?

After ovulation, a secondary oocyte is viable and can be fertilized for approximately 24 hours. This is a critical time window for fertilization to occur. If sperm are present in the female reproductive tract during this period, fertilization is more likely to happen. It's important to note that sperm can survive in the female reproductive tract for up to 5 days, which means that intercourse occurring a few days before ovulation can also lead to fertilization. This is why the most fertile period is considered to be from 2 days before ovulation to 1 day after. Understanding this timing can be crucial for planning or preventing pregnancy.

What is the result of fertilization? Is this one cell or two? Haploid or diploid?

Fertilization results in the formation of a single cell called a zygote. This zygote is diploid, meaning it contains a full set of chromosomes—46 in humans, which is twice the number found in haploid gametes (sperm and egg cells). During fertilization, the haploid sperm and haploid egg combine their genetic material, resulting in a diploid zygote. This zygote will then undergo a series of mitotic divisions, starting with the cleavage process, to eventually form a multicellular organism. So, to answer your question, the result of fertilization is one diploid cell, not two.

When does the egg cell complete meiosis?

The egg cell, or secondary oocyte, completes meiosis during fertilization. This process involves several steps:

Sperm Entry: When a sperm cell enters the secondary oocyte, it triggers the completion of meiosis II. This is a crucial step because the secondary oocyte has paused in meiosis II until fertilization occurs.

Formation of Pronuclei: Upon sperm entry, the sperm nucleus swells to form the male pronucleus. Simultaneously, the secondary oocyte completes meiosis II, forming the female pronucleus. This marks the transformation of the secondary oocyte into an ovum.

Chromosomal Mixing: A spindle forms between the male and female pronuclei, allowing the chromosomes to intermingle, leading to the formation of a diploid zygote.

What are the stages of the pre-embryonic period of human development? What is the process of cleavage, and when does this occur?

Stages of the Pre-Embryonic Period

The pre-embryonic period lasts for the first two weeks after fertilization. It begins with the fertilization of the secondary oocyte by a sperm cell, forming a diploid zygote. The zygote undergoes cleavage, a series of rapid mitotic divisions, producing smaller cells called blastomeres. By day 3, the conceptus becomes a morula, and by day 4, it forms a blastocyst, which implants into the uterine endometrium by days 4-7.

Cleavage Process

Cleavage occurs approximately 30 hours after fertilization. It involves rapid mitotic divisions that increase cell number without growth, resulting in progressively smaller cells. By day 2, the zygote reaches the 4-cell stage, and by day 3, it becomes a 16-cell morula.

Where does a growing conceptus implant in the uterus? About how many days post-fertilization does this occur?

The growing conceptus, known as a blastocyst at this stage, implants into the endometrium of the uterus. This process of implantation typically occurs approximately 4 to 7 days after fertilization. During implantation, the blastocyst attaches to the stratum functionalis layer of the endometrium. The trophoblast, which is the outer layer of the blastocyst, plays a crucial role by secreting enzymes that help it invade the endometrial lining, allowing the blastocyst to embed itself securely. This is a critical step in establishing a successful pregnancy, as it allows the developing embryo to receive nutrients and oxygen from the mother.

What happens to the embryo during implantation? What happens to the uterine llning?

Embryo Implantation Process

Days 4–7: The blastocyst attaches to the uterine lining, specifically the stratum functionalis. The trophoblast differentiates into two layers: syncytiotrophoblast and cytotrophoblast. The syncytiotrophoblast begins to digest the uterine wall, facilitating deeper implantation.

Day 8: The inner cell mass of the blastocyst differentiates into the hypoblast and epiblast, forming the foundation for future embryonic development.

Day 12: The syncytiotrophoblast reaches maternal blood vessels, creating lacunae filled with maternal blood. This supports nutrient exchange.

Day 16: The blastocyst is fully implanted and covered by uterine tissue. Three germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—form, setting the stage for organ development.

Uterine Lining Changes

The syncytiotrophoblast secretes human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), maintaining the corpus luteum to continue estrogen and progesterone secretion. This prevents menstruation and supports the uterine lining's growth and development.

What signaling maintains the uterine lining if implantation is successful? What releases this signal?

The signaling that maintains the uterine lining after successful implantation is primarily due to the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). This hormone is secreted by the syncytiotrophoblast, which is part of the developing blastocyst.

hCG plays a crucial role by maintaining the corpus luteum, which in turn continues to secrete estrogens and progesterone. These hormones are essential for sustaining the uterine lining, preventing menstruation, and supporting the early stages of pregnancy. As the pregnancy progresses, the placenta eventually takes over the production of estrogens and progesterone, but hCG is vital in the initial stages to ensure the uterine environment remains conducive to the developing embryo. This process prevents the breakdown of the uterine lining and supports the continued growth and development of the embryo.

What are the extraembryonic membranes? What is the function of each?

Extraembryonic Membranes

The extraembryonic membranes are crucial structures that support the developing embryo. They include the yolk sac, amnion, allantois, and chorion, each with specific functions:

Yolk Sac: This is the first membrane to develop and contributes to forming the digestive tract. It is also the source of the first blood cells, blood vessels, and germ cells, which are precursors to gametes.

Amnion and Amniotic Cavity: The amnion surrounds the embryo and produces amniotic fluid. This fluid protects the embryo from trauma, maintains a constant temperature, allows muscle development, and prevents adhesion of body parts during growth.

Allantois: It forms the base for the umbilical cord, linking the embryo to the placenta, and eventually becomes part of the urinary bladder.

Chorion: This outermost membrane encloses all other membranes and forms the chorionic villi, which are integral to placenta formation.

What is gastrulation? What are the three primary germ layers?

Gastrulation is a crucial process in embryonic development that occurs during the third week. It involves the transformation of the bilaminar embryonic disc into a trilaminar disc, forming three primary germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. This process begins with the formation of the primitive streak on the epiblast's surface, where cells migrate inward through a process called ingression.

Three Primary Germ Layers:

Ectoderm: Forms the outermost layer, giving rise to the epidermis, nervous system, and sense organs.

Mesoderm: Develops into skeletal structures, muscles, and most organs, excluding epithelial linings.

Endoderm: Becomes the linings and glands of the digestive and respiratory tracts, along with several endocrine glands.

By the end of week 3, these layers are established, setting the foundation for organogenesis.

What is the placenta? What functions occur here?

Placenta Overview

The placenta is a temporary organ that forms during pregnancy, connecting the mother and fetus. It develops from both fetal and maternal tissues, with the fetal portion formed by chorionic villi and the maternal portion by the decidua basalis.

Functions of the Placenta

Exchange of Substances: The placenta facilitates the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and wastes between maternal and fetal blood. Oxygen and nutrients diffuse from maternal blood into fetal blood, while wastes move from fetal blood to maternal blood.

Hormone Production: It produces hormones essential for maintaining pregnancy.

Barrier Function: The placental barrier prevents direct mixing of maternal and fetal blood, protecting against potential blood type incompatibilities.

What does the placental barrier consist of? What substances can cross this barrier? Which cannot?

The placental barrier is a complex structure that separates maternal and fetal blood. It consists of several layers:

Maternal and Fetal Basal Laminae: These are thin layers of extracellular matrix.

Fetal Connective Tissue: Provides structural support.

Cytotrophoblast and Syncytiotrophoblast: These are layers of cells that facilitate exchange and protect the fetus.

Substances That Can Cross the Placental Barrier

Oxygen and Nutrients: These diffuse from maternal blood to fetal blood.

Wastes: These move from fetal blood to maternal blood for excretion.

Certain Drugs and Hormones: Some medications and hormones can cross, affecting fetal development.

Substances That Cannot Cross

Blood Cells: Maternal and fetal blood cells do not mix, preventing blood type incompatibilities.

Large Molecules: Proteins and certain pathogens are typically too large to pass through.

The placental barrier acts as a selective filter, allowing essential exchanges while protecting the fetus from potential harm.

What does the term organogenesis refer to? When during development does this process take place?

Organogenesis is the process during which the three primary germ layers of an embryo—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—differentiate into organs and organ systems. This crucial phase of development begins after the embryo undergoes cephalocaudal and transverse folding, typically starting around the third week of development and continuing through the eighth week. By the end of this period, the embryo will have recognizable organ systems, although not all organs will be functional yet.

Development Timeline

Week 3 to Week 8: The embryonic period, where organogenesis occurs. The embryo starts as a small structure and grows to about 25 mm by the end of week 8, with rudimentary organ systems in place.

What is the umbilical cord? Is the blood flowing through the umbilical arteries oxygen-rich or oxygen-poor? What about the umbilical vein?

The umbilical cord is a vital structure that connects the fetus to the placenta, facilitating the exchange of nutrients, gases, and waste between the mother and the developing fetus. It contains two umbilical arteries and one umbilical vein.

Umbilical Arteries: These arteries carry deoxygenated blood away from the fetal heart to the placenta. This might seem counterintuitive since arteries typically carry oxygenated blood, but the key function of arteries is to transport blood away from the heart, regardless of its oxygen content.

Umbilical Vein: In contrast, the umbilical vein carries oxygen-rich blood from the placenta back to the fetal heart. This is one of the exceptions where a vein carries oxygenated blood, as veins are generally defined by their role in carrying blood toward the heart.

What are three ways that fetal circulation is different than that of a typical adult human? What is the functional reason for these differences?

Fetal circulation differs from adult circulation in several key ways due to the unique needs of the developing fetus. Here are three major differences:

Ductus Venosus: In fetal circulation, the ductus venosus allows blood from the umbilical vein to bypass the liver and flow directly into the inferior vena cava. This is because the fetal liver is not fully functional, and the maternal liver performs most of the filtering and storage functions.

Foramen Ovale: This is an opening between the right and left atria of the heart. It allows blood to bypass the non-functional fetal lungs by moving directly from the right atrium to the left atrium, facilitating systemic circulation.

Ductus Arteriosus: This shunt connects the pulmonary trunk to the aorta, allowing blood to bypass the lungs and flow directly into the systemic circulation.

These adaptations ensure that oxygen-rich blood from the placenta is efficiently distributed to the fetal body, as the lungs are not yet used for gas exchange before birth. After birth, these shunts close, and the circulatory system transitions to the adult pattern.**

What are some physiological changes that occur during pregnancy?

Pregnancy involves numerous physiological changes across various organ systems to support the developing fetus and prepare the mother's body for childbirth and lactation.

Hormonal Changes: Hormones like aldosterone increase blood volume, while parathyroid hormone maintains high calcium levels for fetal development. Prolactin stimulates milk production, and oxytocin aids uterine contractions and milk release.

Reproductive System: The uterus enlarges significantly, extending from the pelvic cavity to the xiphoid process. This growth is due to myometrium hypertrophy, placental growth, and amniotic fluid accumulation.

Digestive System: Elevated hormones can cause morning sickness and constipation due to slowed peristalsis.

Urinary System: Increased metabolic waste from the fetus raises the glomerular filtration rate, leading to frequent urination.

Integumentary System: Changes include increased pigmentation and stretch marks due to rapid uterine enlargement.

Cardiovascular System: Blood volume and cardiac output rise to support the placenta, potentially causing varicose veins and edema.

What hormones are involved in the positive feedback loop that stimulates uterine contractions during pregnancy? What is the function each in this feedback loop?

Oxytocin: This hormone is secreted by both the fetal and maternal hypothalamus. It plays a crucial role in stimulating uterine contractions. As the contractions occur, they push the baby's head against the cervix, causing it to stretch. This stretching triggers the release of more oxytocin, further intensifying the contractions.

Prostaglandins: These are produced by the placenta in response to oxytocin. Prostaglandins help dilate the cervix and, along with oxytocin, increase the strength and frequency of uterine contractions.

Estrogens: High levels of estrogens, stimulated by fetal cortisol, increase the number of oxytocin receptors on the uterus, making it more responsive to oxytocin.

This positive feedback loop continues to amplify until childbirth is complete, ensuring effective labor and delivery.

What are the three stages of labor? What occurs in each stage?

Dilation Stage: This is the longest stage, lasting 8–24 hours for first-time mothers and 4–12 hours for those who have given birth before. It begins with labor onset and ends when the cervix is fully dilated to 10 cm. Contractions start in the upper uterus and move downward, becoming stronger as labor progresses. The amnion ruptures, releasing amniotic fluid, known as "water breaking."

Expulsion Stage: This stage lasts from full dilation to the delivery of the newborn, typically 30 minutes to 1 hour. Strong contractions occur, and the mother may push to aid delivery. Crowning occurs when the fetus's head distends the vagina. The umbilical cord is clamped and cut after delivery.

Placental Stage: Following the baby's delivery, the placenta and fetal membranes are expelled from the uterus.

What conceptus position is most conducive for a vaginal childbirth?

The most conducive position for a vaginal childbirth is the vertex or head-first presentation. In this position, the fetus' head is aligned to press against the cervix, aiding in its thinning and dilation. This alignment facilitates the progression through the birth canal during labor, making it the preferred position for a smooth vaginal delivery.

During the dilation stage, the cervix dilates to about 10 cm, allowing the fetus to move into the lesser pelvis. The expulsion stage follows, where strong contractions help push the fetus through the birth canal. If the fetus is in a breech position (buttocks-first), complications can arise, such as the umbilical cord wrapping around the fetus, often necessitating a cesarean section for safe delivery.

What hormones are involved in the milk "letdown" reflex? What is the function of each in this feedback loop?

Oxytocin: This hormone is produced by the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary gland. When an infant suckles at the nipple, it triggers the release of oxytocin. Oxytocin then binds to myoepithelial cells in the mammary glands, causing them to contract and eject milk. This process is known as the milk letdown reflex. The more the infant suckles, the more oxytocin is released, creating a positive feedback loop that continues until the infant stops suckling.

Prolactin: This hormone is produced by the anterior pituitary gland. It is also stimulated by infant suckling. Prolactin's primary role is to stimulate the mammary glands to produce more milk, ensuring a continuous supply as long as the infant continues to nurse.

Together, these hormones ensure that milk is both produced and ejected efficiently during breastfeeding.

What is a gene? What is an allele?

A gene is a segment of DNA that codes for a specific protein, essentially serving as a blueprint for tissues and organs. Genes are found on chromosomes, and each person has a unique set of genes that determine various traits.

An allele is a variant form of a gene. While genes are located at the same position (locus) on homologous chromosomes, alleles can differ slightly in their nucleotide sequences. This variation leads to different traits, such as eye color. For example, one allele might code for brown eyes, while another codes for blue eyes.

Alleles can be dominant or recessive. Dominant alleles mask the expression of recessive ones. For instance, freckles are coded by a dominant allele (F), while the absence of freckles is coded by a recessive allele (f). Individuals with FF or Ff genotypes will have freckles, while those with ff will not.

What is a genotype? What does it mean to have a homozygous genotype? What about a heterozygous genotype?

A genotype refers to the genetic makeup of an individual, specifically the combination of alleles inherited from both parents. Alleles are different versions of a gene found at the same locus on homologous chromosomes.

Homozygous Genotype

Definition: When an individual has two identical alleles for a particular gene, they are homozygous for that trait. For example, having two alleles for blue eyes.

Types: Homozygous dominant (e.g., FF for freckles) and homozygous recessive (e.g., ff for no freckles).

Heterozygous Genotype

Definition: When an individual has two different alleles for a gene, they are heterozygous. For instance, one allele for blue eyes and another for brown eyes.

Expression: The dominant allele masks the recessive one, so the phenotype reflects the dominant trait.

Genotype vs. Phenotype

Genotype: The genetic makeup (e.g., FF, Ff, ff).

Phenotype: The physical expression of the genotype (e.g., presence or absence of freckles).

How is a phenotype different than a genotype? How is a phenotype related to a genotype?

Genotype: This is the genetic makeup of an individual, consisting of the alleles inherited from both parents. It represents the specific genetic information carried by an organism, such as the alleles for eye color (e.g., BB, Bb, or bb).

Phenotype: This is the observable physical or physiological trait of an organism, which results from the expression of the genotype. For example, the phenotype could be blue eyes or brown eyes, depending on the genotype.

Relationship Between Genotype and Phenotype

The phenotype is the physical manifestation of the genotype. For instance, if the genotype for freckles is either FF or Ff, the phenotype will be the presence of freckles because the dominant allele (F) is expressed.

The genotype determines the potential traits, but the phenotype is what you actually observe. Environmental factors can also influence the phenotype, meaning that the same genotype can result in different phenotypes under different conditions.

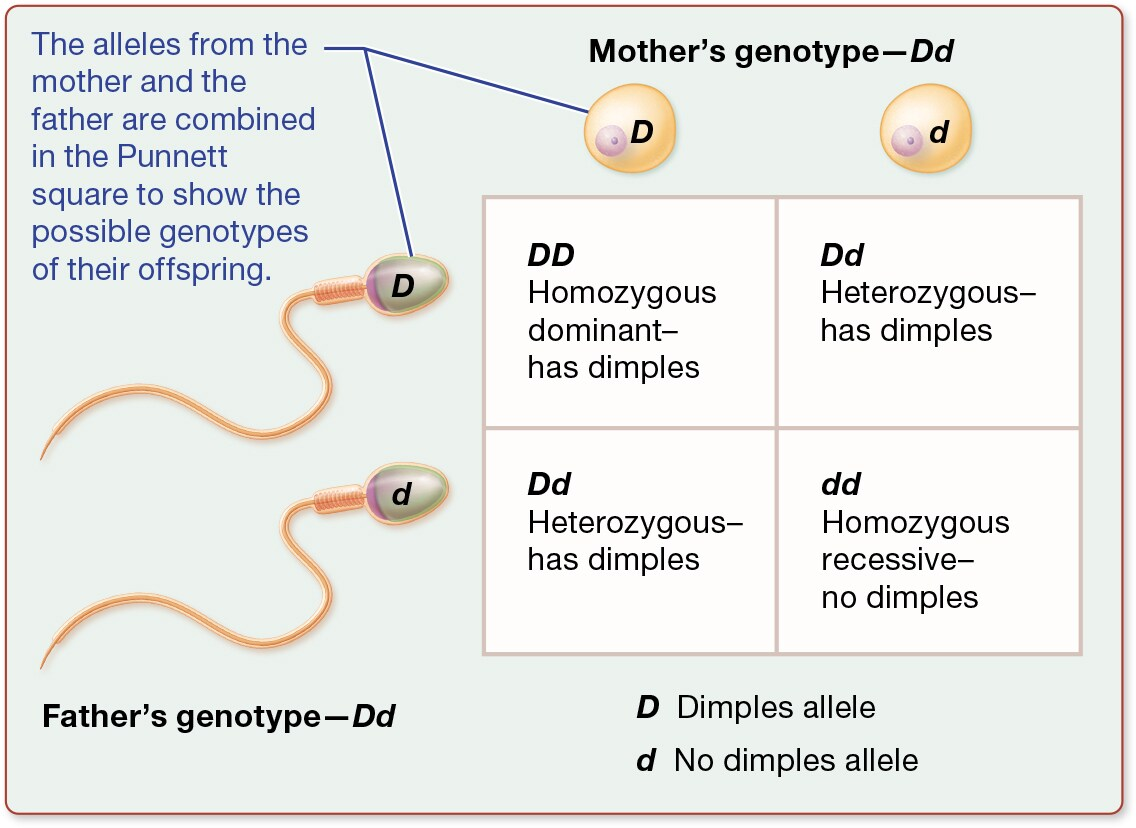

What is a Punnett square? What two biological processes does it model, and how does it model these?

Punnett Square Overview: A Punnett square is a diagram used in genetics to predict the genotypes of offspring from a particular cross or breeding experiment. It is named after Reginald C. Punnett, who devised the approach.

Biological Processes Modeled:

Meiosis: This is the process of cell division that results in gametes (sperm and eggs), each carrying half the genetic information of the parent. The Punnett square models how alleles segregate during meiosis.

Fertilization: This process involves the fusion of gametes to form a new organism. The Punnett square shows how alleles from each parent combine during fertilization.

Modeling with Punnett Square:

Setup: The alleles from one parent are listed across the top, and the alleles from the other parent are listed down the side.

Combination: Each box within the square represents a possible genotype for the offspring, formed by combining one allele from each parent.

This tool helps visualize the probability of inheriting particular traits, making it a fundamental concept in understanding genetic inheritance.

What does it mean for one allele to be completely dominate over the other? How is this typically notated?

Complete Dominance of Alleles

When one allele is completely dominant over another, it means that the dominant allele can mask or suppress the expression of the recessive allele in the phenotype. This occurs even if the individual has only one copy of the dominant allele. For example, if the allele for freckles (F) is dominant over the allele for no freckles (f), individuals with genotypes FF or Ff will have freckles, while only those with ff will not.

Notation

Alleles are typically represented by letters: capital letters for dominant alleles and lowercase letters for recessive alleles. For instance, in the case of dimples, 'D' represents the dominant allele for dimples, and 'd' represents the recessive allele for no dimples. The Punnett square below illustrates how these alleles combine:

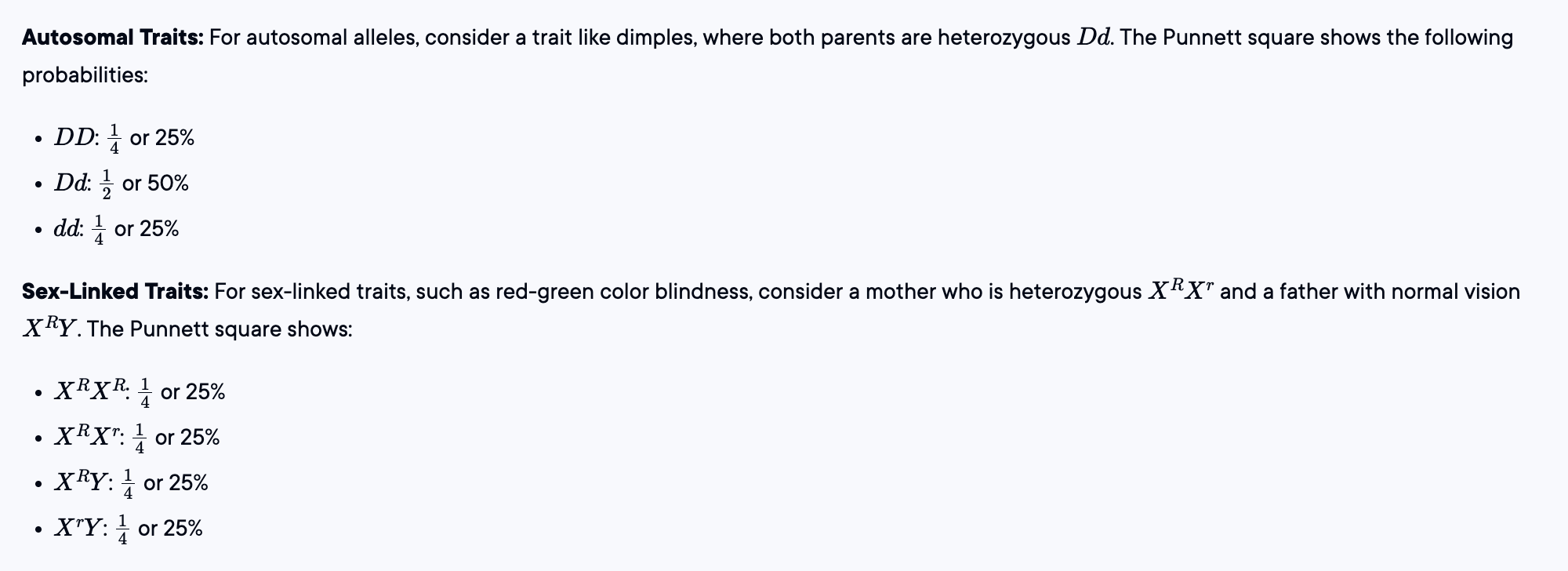

What considerations need to be taken when working with sex-linked traits? How is allelic notation typically handled in this case?

When working with sex-linked traits, it's important to consider that these traits are associated with genes located on the sex chromosomes, X and Y. Since males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY), and females have two X chromosomes (XX), the inheritance patterns differ between the sexes. For example, a recessive trait on the X chromosome can be expressed in males even if they have only one copy of the allele, because they lack a second X chromosome that could carry a dominant allele to mask it.

Allelic Notation for Sex-Linked Traits:

X-Linked Traits: Alleles are typically denoted with superscripts on the X chromosome. For example, Xᴿ represents a normal vision allele, while Xʳ represents a color blindness allele. A male with normal vision would be XᴿY, while a color-blind male would be XʳY.

Y-Linked Traits: These are less common and are typically notated simply as Y, since there is no corresponding allele on the X chromosome.

Could you determine the probability of an offspring of a given genotype and/or phenotype given the genotypes of the two parents of the offspring for autosomal alleles? What about sex-linked traits?

If a couple has a 25% probability of producing an offspring with a given trait, does this mean if they have four children, one of them will definitely have the trait?

A 25% probability of an offspring having a particular trait does not guarantee that one out of four children will have that trait. Probability is a measure of likelihood, not certainty. Each child is an independent event, meaning the probability remains 25% for each child, regardless of the outcomes of previous children.

Think of it like flipping a coin. Even though there's a 50% chance of landing on heads, flipping the coin four times doesn't ensure you'll get exactly two heads. Similarly, with a 25% probability, it's possible to have zero, one, two, three, or even four children with the trait.

In genetics, each child's genotype is determined independently, so while probabilities can guide expectations, they don't predict exact outcomes for a small number of offspring.

What is a polygenic trait? Are most traits polygenic?

Polygenic Traits

A polygenic trait is one that is influenced by the combined effects of two or more genes. This type of inheritance is known as polygenic inheritance. Examples of polygenic traits include height, skin color, and eye color. These traits do not follow the simple Mendelian inheritance patterns, where a single gene determines a trait. Instead, multiple genes contribute to the phenotype, resulting in a wide range of possible outcomes.

Are Most Traits Polygenic?

Yes, most traits are polygenic. This means that they are controlled by multiple genes rather than a single gene. For instance, height is influenced by several genes, each contributing to the overall height of an individual. The interaction of these genes can produce a variety of phenotypes, which is why there is such a wide range of heights among people.

Example of Polygenic Inheritance

In the case of height, one gene might have alleles that determine whether an individual is tall, medium, or short, while another gene might have alleles that affect height reduction. The combination of these alleles from both parents results in a variety of possible heights for their offspring.