exam 2 notes

1/161

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

162 Terms

causes and clinical signs for oropharyngeal diseases

causes

dental disease

trauma

foreign bodies

infection

ulcerative diseases

congenital anomalies

neoplasia

signs

reluctance / refusal to eat

abnormal chewing movements

retention of feed “quidding”

protrusion and or swelling of the tongue

drooling and or excessive salivation (ptyalism)*

mandibular / maxillary swelling or drainage

halitosis

examination for oropharyngeal diseases

observation: body condition, drooling, swelling of face or jaw, tongue protrusion, quid’s (feed balls) on ground

give some feed and observe mastication

oral examination

facilitated by sedation

irrigation of the mouth

manual / visual exam

thorough examination requires full mouth speculum and an effective light source, headlamp; mirror

ancillary diagnostics

radiography, CT/MRI, oral endoscopy*

Trauma to oropharyngeal diseases

lips, muzzle, cheek and tongue lacerations

superficial lacerations of lips, muzzle, and cheeks heal well by 2nd intention

primary closure for lacerations breaching oral mucosa

clean, local anesthetic, debride, 2-layer closure, no suture exposed at mucosa

these typically heal nicely due to ample blood supply

large tongue lacerations heal well when sutured; can amputate if needed

to level of frenulum if necessary with little problem

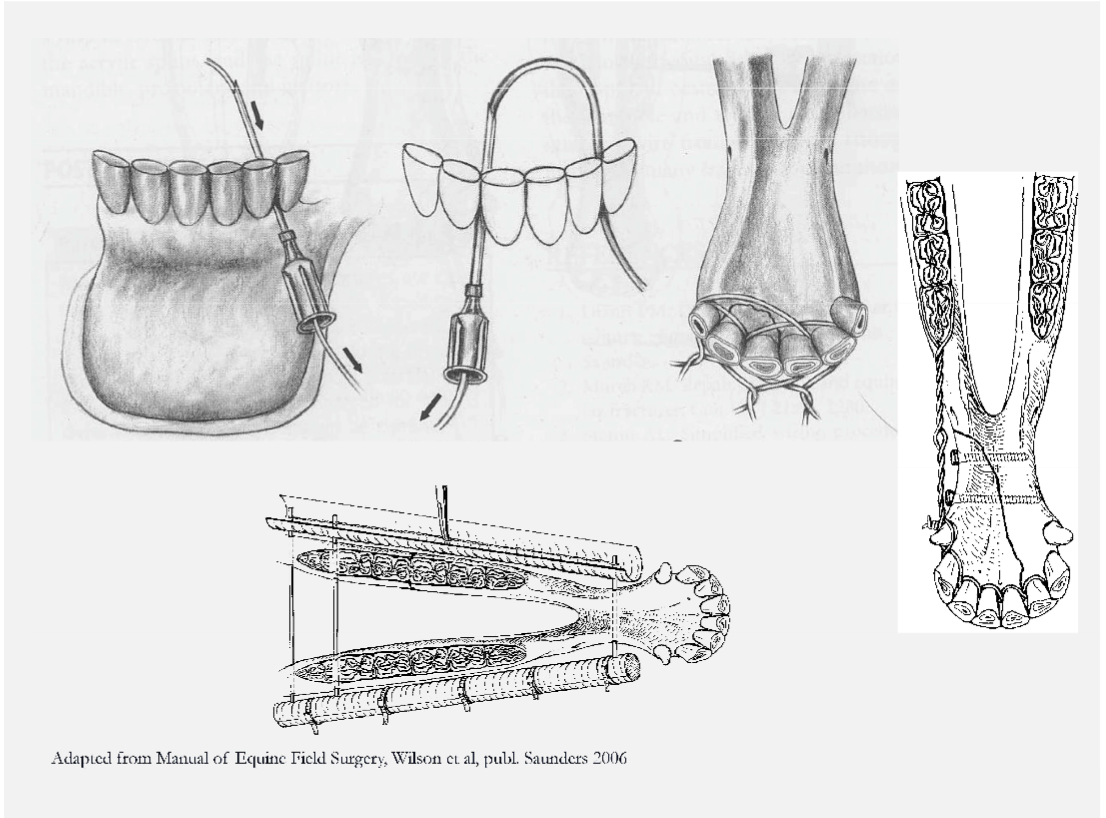

trauma fractures of the mandible and rostral maxilla

kicks, collisions, cribbing, bite injuries, more

can result in fractures of teeth, incisor bone / premaxilla, mandible

fracture configurations range from bone fragments to complex bilateral fractures

signs are drooling, lack of feed intake, mal-alignment and or instability, crepitus, soft tissue swelling, malodorous with time

generally can be managed / repaired with good results

some mandibular fractures are simple bone fragments

may present as sequestrum with draining tract

surgical removal and curettage

minimally displaced unilateral fractures of mandibular bars

managed conservatively with soft feeds, oral rinses, time

instability, malocclusion and bilateral fractures need stabilized

intraoral wiring for loose incisors, fractures of incisive bone / premaxilla and rostral mandible

wiring, bone screws and plates and external fixation for more complex and or caudal fractures

Oropharyngeal foreign bodies

grass awns, splinters, and wires

may locate in lingual, sublingual, intermandibular tissues, buccal recesses, hard palate, soft palate, pharynx

results and signs can include

stomatitis, glossitis, cellulitis, abscess

salivation, halitosis, eating difficulties, feed refusal

careful oral exam using speculum, light source, palpation; radiogrpahy and endoscopy

removal followed by systemic antibiotics if indicated, NSAID, repeated oral lavage

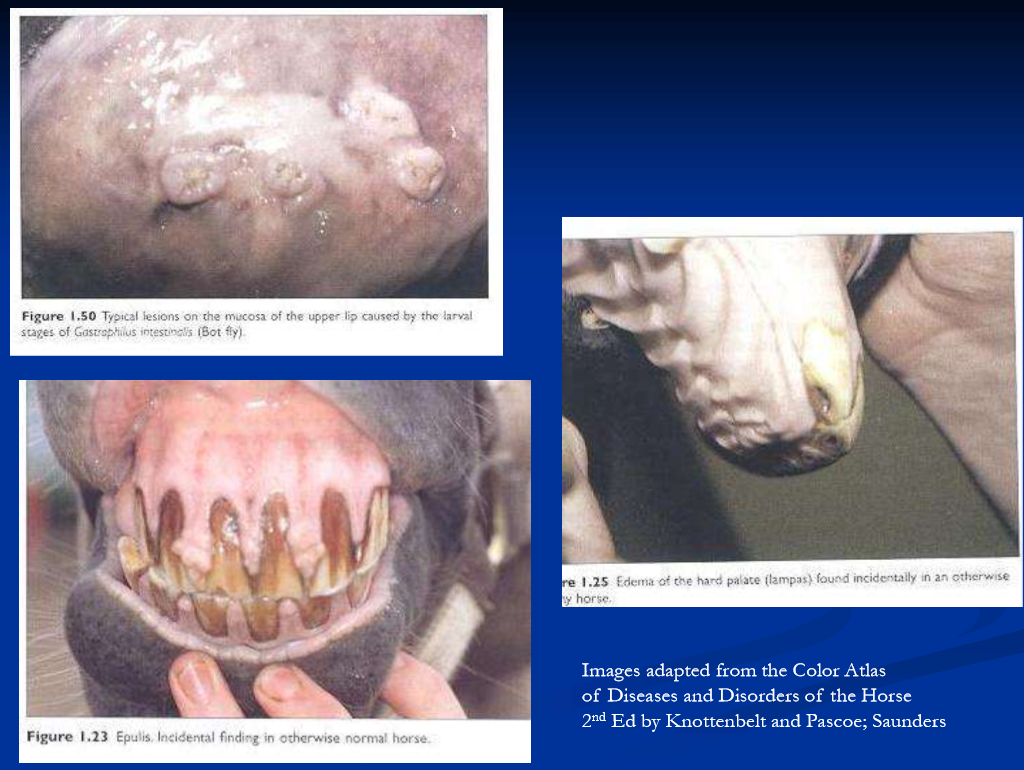

other causes of stomatitis / glossitis

dental points cause tongue / check lacerations; common

parasite larvae: Habronema, Gasterophilus, Helicocephalobus,

Gastrophilus larvae cause stomatitis characterized by ptyalism; all may cause labial / oral granulomas

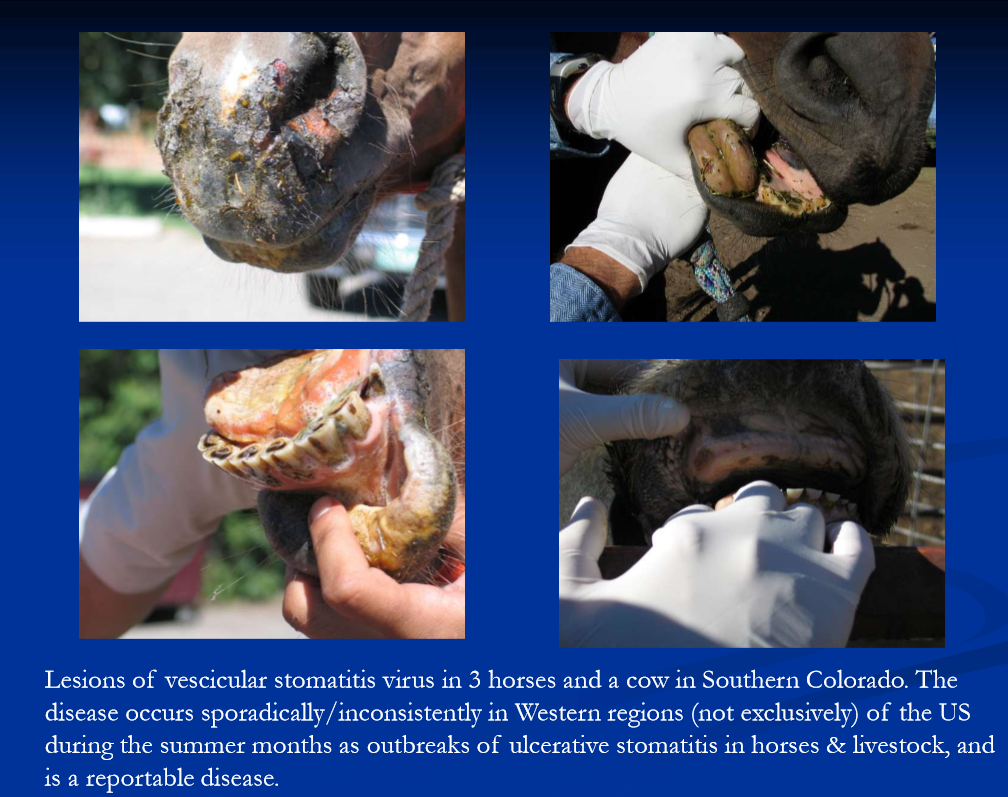

oral ulcers: blister beetles, vesicular stomatitis virus, NSAID toxicity, caustic ingestion, uremia

epulis: gingival hyperplasia associated with chronic irritation example erupting permanent teeth / caps

lampus: benign swelling of hard palate caudal to incisors; eruption of permanent incisors or idiopathic

manage inflammatory / ulcerative / infectious with oral rinses / lavage, NSAIDs, systemic antibiotics if indicated

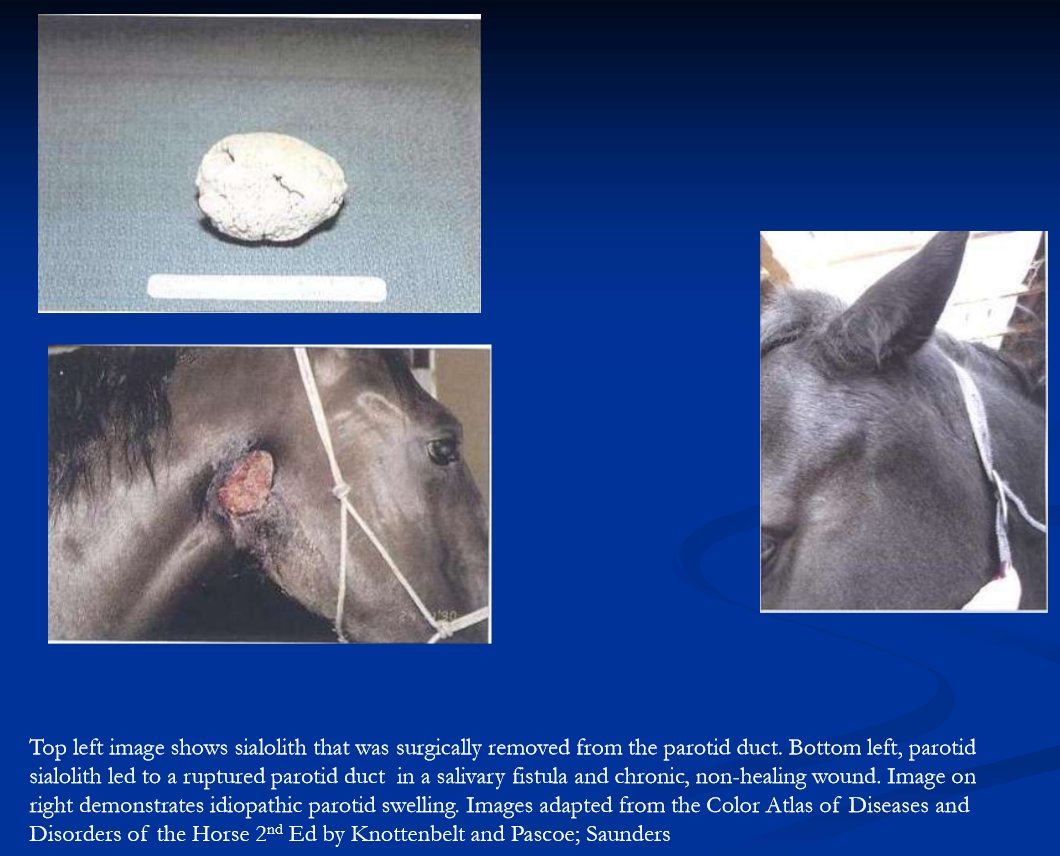

salivary gland disease

Sialoliths: may lead to duct rupture, fistula; sx removal

trauma/lacerations of parotid gland and or duct

lacerated gland, duct/branches may result in salivary fistula

repair severed/lacerated parotid duct if possible

can be corrected with dissection and repair

gland can be destroyed chemically if needed

obstruction of sublingual ducts mucoseal; marsupialize

slaframine toxicity common in some areas

Red clover infected with Rhizoctonia legumencola

Herd outbreaks of ptyalism

remove from source

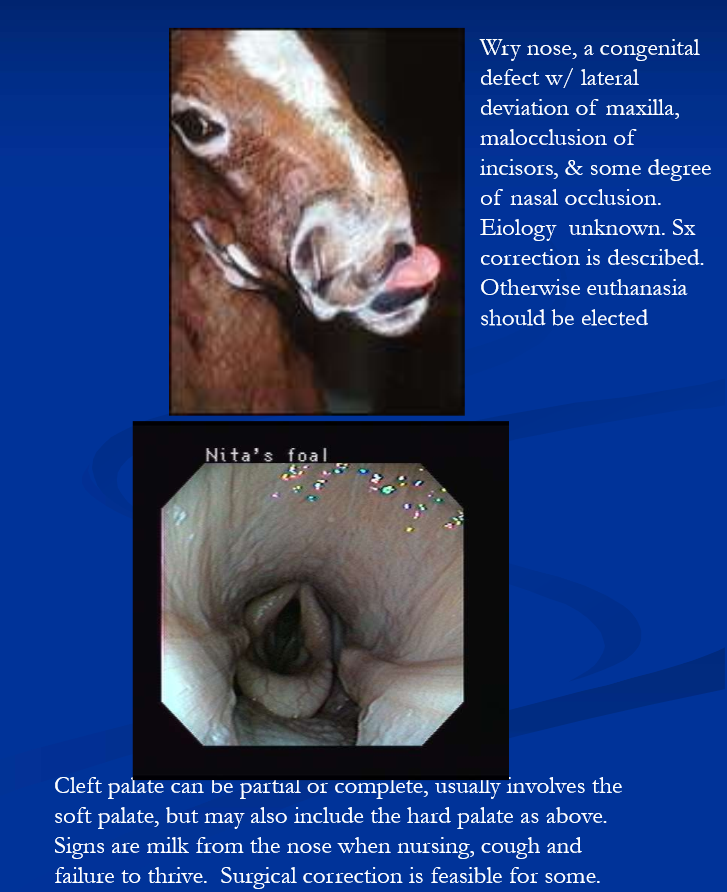

congenital oropharyngeal defects

Cleft palate, tongue, mandible

wry nose

dental anomalies (more later)

parrot mouth (overbite)

sow mouth (underbite)

shear mouth

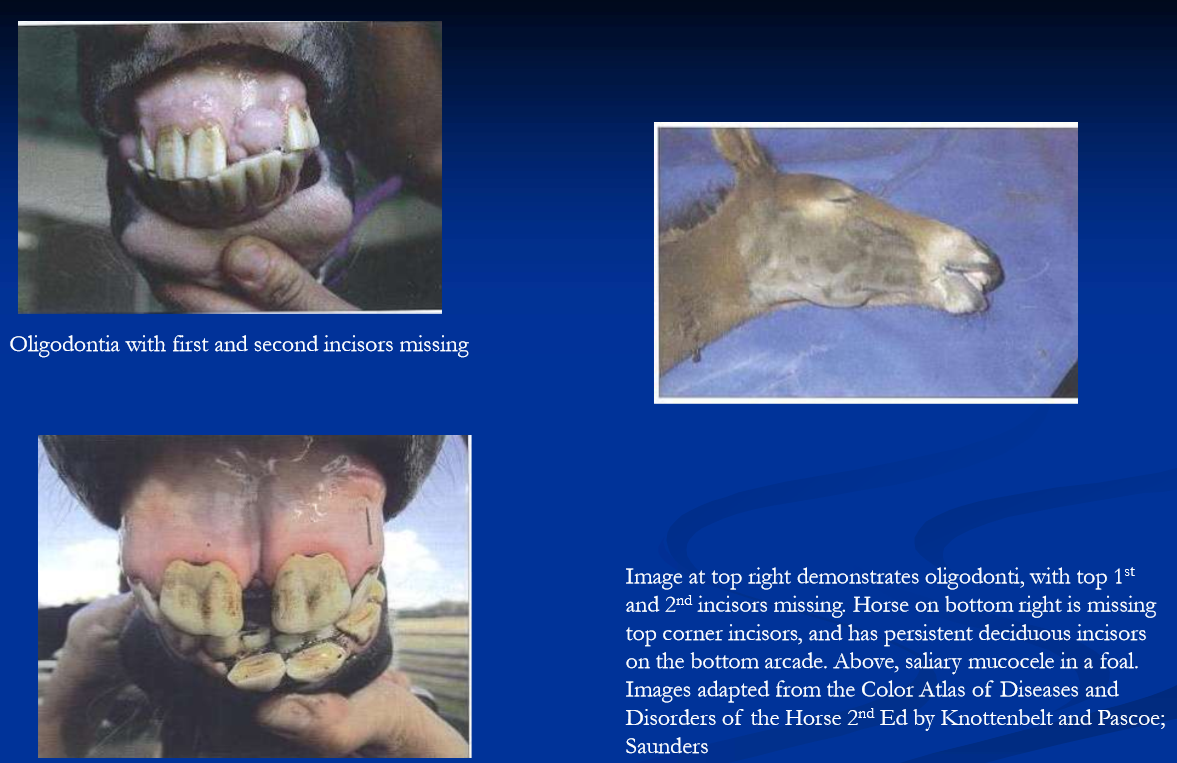

oligodontia

supernumerary teeth

dentigerous cysts

developmental anomalies of teeth

Oligodontia, supernumerary teeth, crowding of teeth

parrot mouth: maxillary prognathism (or inferior brachygnathism); maxilla protrudes beyond mandible

severe overbite is a

major unsoundness

possibly heritable

corrective orthodontics sometimes performed

sow mouth; mandibular prognathism (or superior brachygnathism)

lower jaw extends beyond maxilla; “underbite”

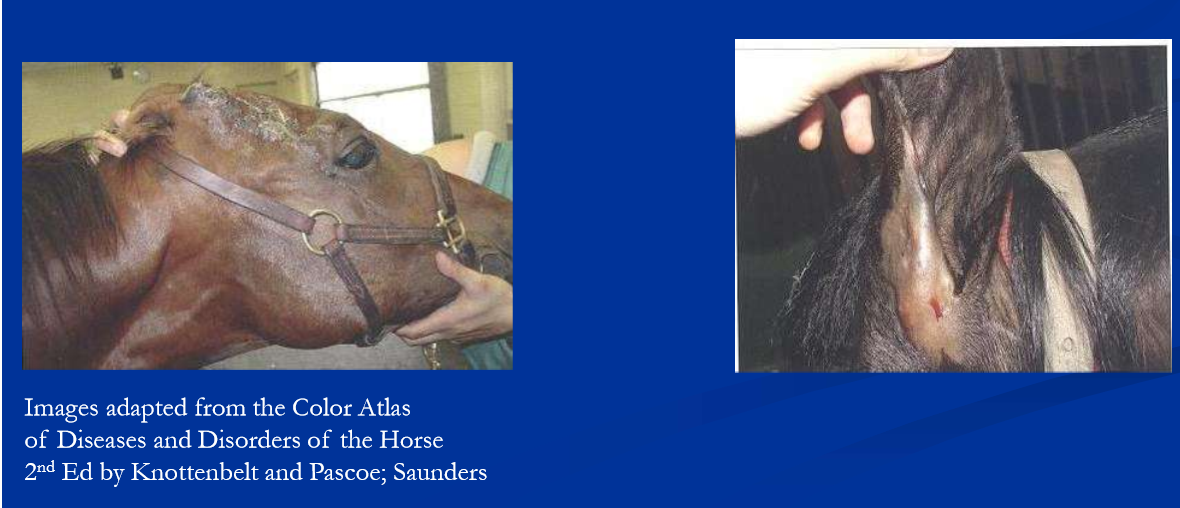

dentigerous cysts

developmental anomaly; cystic structures in soft tissue over maxilla or mandible, often containing fragments of teeth

often found at base of ear and are presented as draining tract

Oropharyngeal neoplasia

melanoma at commissures

squamous cell carcinoma

less common

bone tumors: benign types are ossifying fibroma, osteoma; osteosarcoma is rare but majority occur in the head

ossifying fibroma in foals/yearlings; usually mandibular; resection via hemi-mandibulectomy; radiation also

primary dental tumors: odontoma, ameloblastoma

tx and px depends on location and histological diagnosis

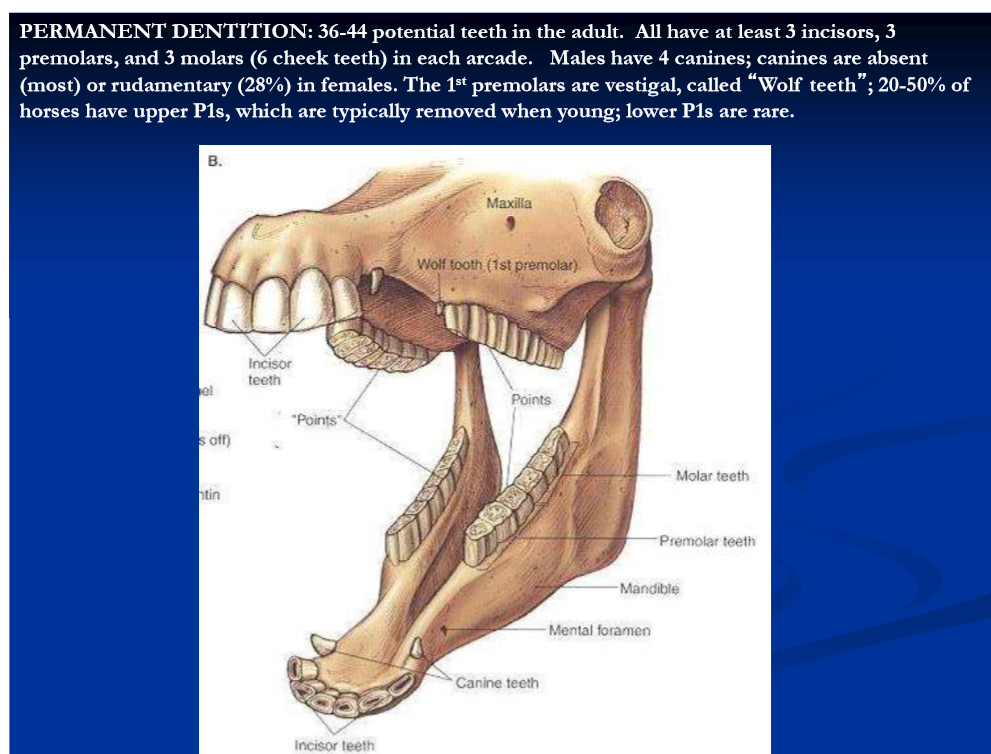

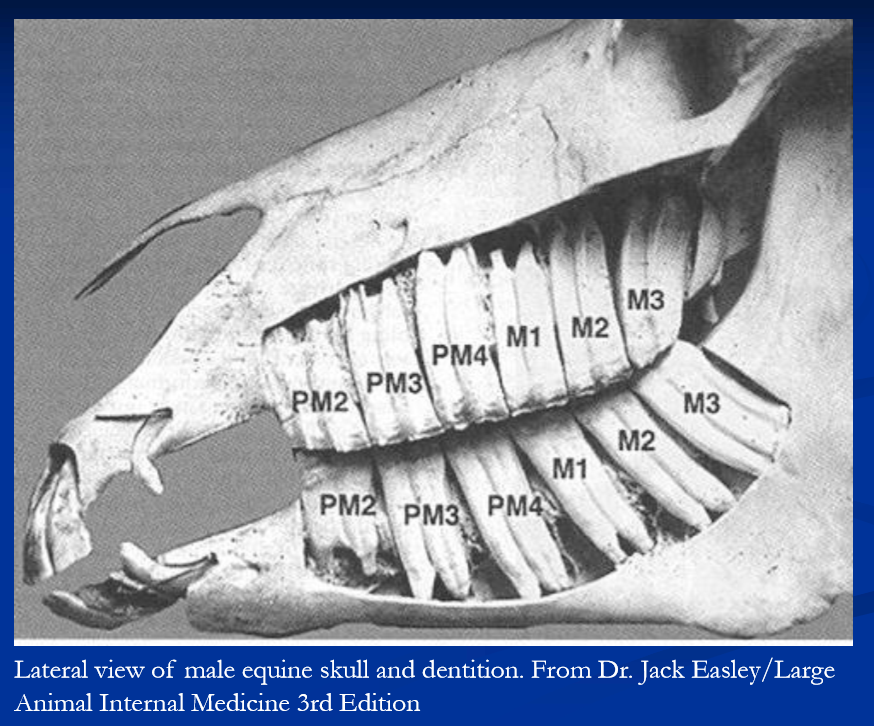

form and function of equine teeth

Hypsodont teeth

long crown, short roots, enamel extends below gum line

incisors grasp, tear and pull the grass

cheek teeth are made for grinding the grass

growth of crown continues until 6-9yr

wear occurs at rate of 2-3mm / yr

reserve crown in alveolar bone erupts continually throughout adult life in response to wear, thus maintaining occlusion

length of reserve crown decreases gradually with this process; aged horse become “smooth mouthed”

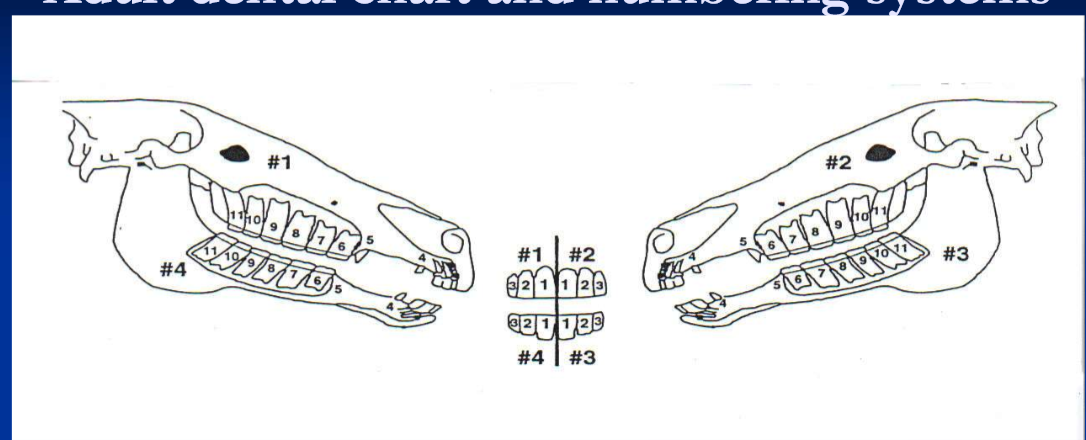

adult dental chart and numbering systems

anatomic: I1-3, C1, P1-4, M1-3

Triadan: quadrants 1-4; upper right = 1, upper left = 2, lower left = 3 and lower right = 4; teeth numbered 1 to 11 in each quadrant.

for example 1st upper right incisor is 101, last lower left molar is 311

for deciduous teeth the quadrants are 5-8

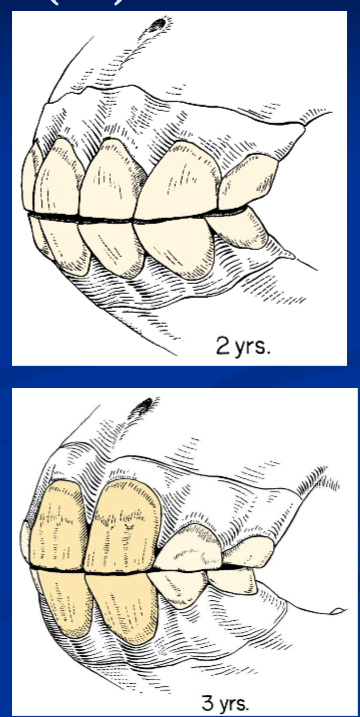

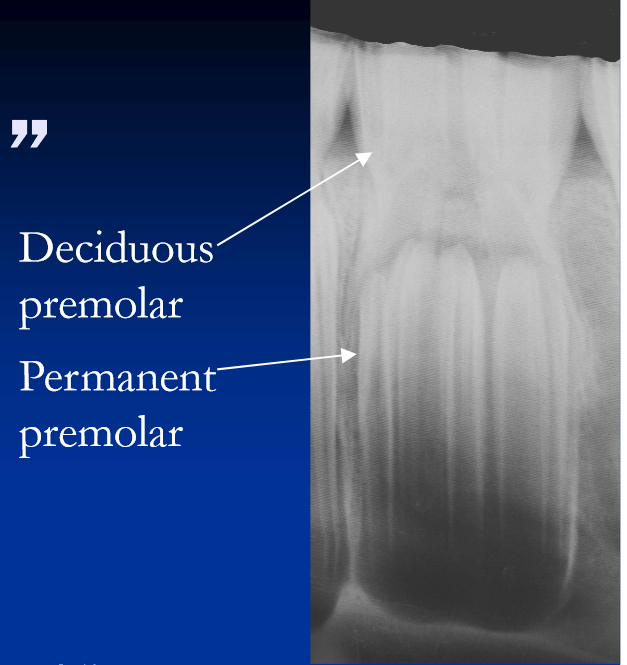

deciduous teeth

24 in total

the deciduous teeth are incisors and premolars; there are no deciduous molars

at 6 months there are 3 deciduous incisors and 3 premolars in each arcade; 4×6 = 24 teeth total (excluding any wolf teeth)

deciduous teeth are white with narrow neck

eruption times for permanent teeth

permanent incisors (I1-3) erupt at 2.5, 3.5, 4.5 years

eruption times useful in aging young horses

canine (C1) at 4 to 5 years (all males, some females)

premolars: 2.5, 3 and 4 years for P2-4

(wolf teeth (P1) at 5-6 months when present)

molars (M1-3) at 1,2 and 3.5 to 4 years

clinical signs of dental disease

weight loss

biting problems

reluctance to eat

retention of hay in the cheeks

quidding

tilting head when chewing

halitosis (bad breath)

bloody saliva

facial/mandibular swellings

drainage from maxilla or mandible

malodorous, unilateral purulent nasal discharge

routine dental care

exam at birth: occlusion, congenital defects

exam 1-2x yearly as part of routine prevention

depending on age, diet, pre-existing problems

“floating” to remove points and hooks on cheek teeth

wolf teeth: usually removed at 1-2 yrs of age

dental caps: deciduous teeth being shed as permanent erupts; remove if/when retained, especially premolars

upper and lower P2s sometimes contoured for “bit seat”

canine teeth: file down if sharp

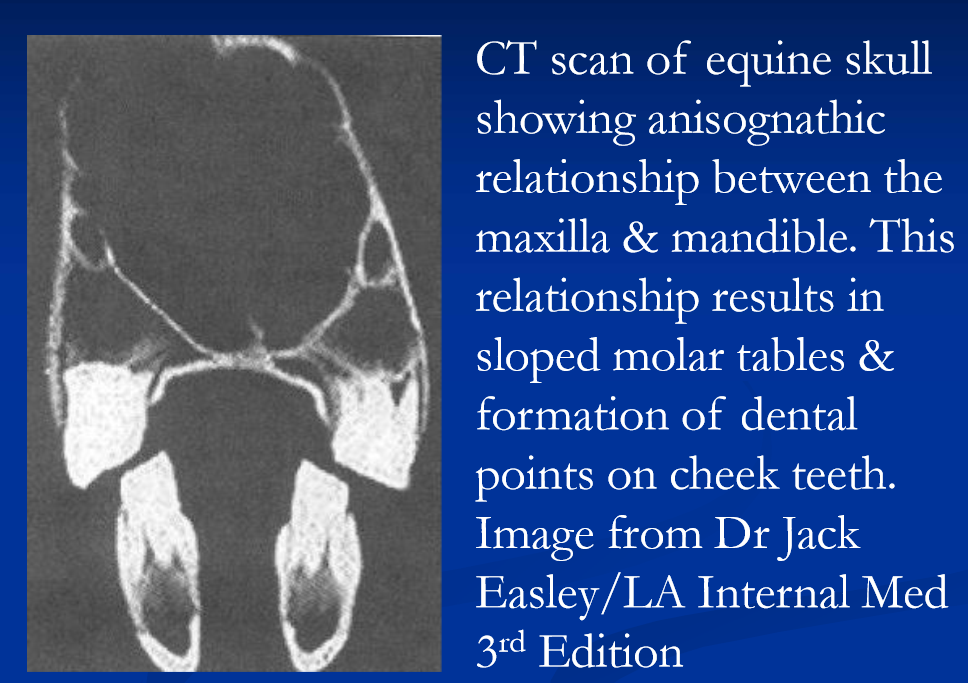

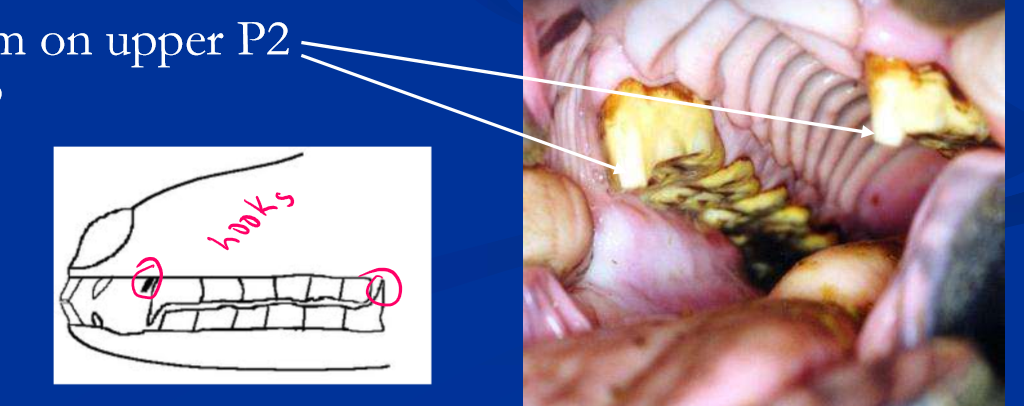

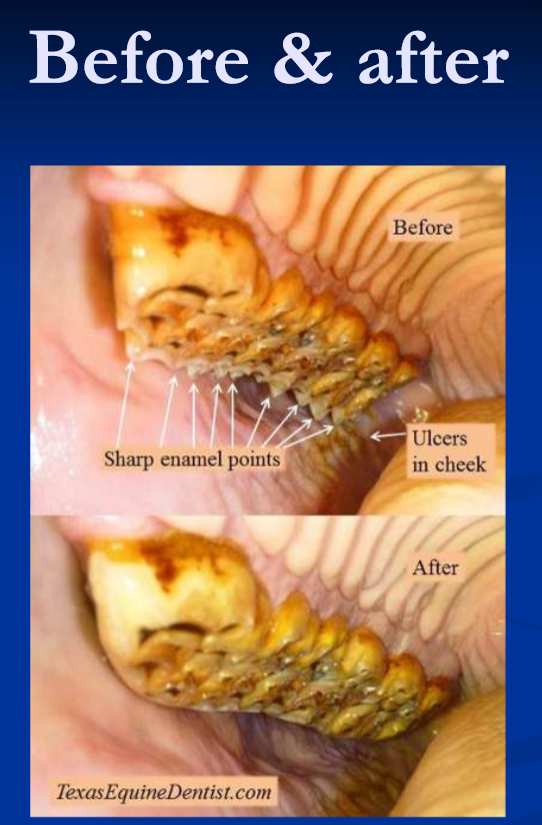

points and hooks

horses have prominent anisognathism; bottom jaw is narrow compared to upper

mastication results in sloped arcades of cheek teeth

sharp enamel “points” form on outside uppers and inside lowers; lacerations / ulcers on tongue and cheeks

“hooks” form on upper P2 and lower M3

floating teeth: rasping / filling to remove points and hooks

as needed in young horses with deciduous and erupting cheek teeth

once annually for pastured horses

2x/yr for stabled horses

as needed for horses with malocclusions, missing teeth

hand floats or power instruments; careful with power float thermal injection

Incisor abnormalities

retained deciduous incisors may lead to caudal displacement of permanent teeth

extraction of deciduous tooth indicated

trauma to incisors

remove loosened deciduous incisors to protect permanent tooth bud

if permanent incisor, stabilization should be attempted

mandibular and maxillary fractures can displace or destroy tooth buds of permanent teeth

fractures: many are non-problematic but

may involve associated boney structures, requiring fracture stabilization

pulp infection may occur can be managed with endodontics (vital pulpotomy / “root canal”); otherwise may require extraction

extraction of incisors

involves chemical restraint local anesthesia, incision of gingiva directly over root, loosen periodontal ligament, complete extraction of root

need to keep opposing tooth reduced over time

mal-alignment of incisor teeth

smile, frown, and tilt contours are associated with cheek teeth abnormalities

addressing malocclusion of cheek teeth is the key; rasping to change incisor contour is questionable

steps are overgrowth of individual incisors from absence or displacement of opposing tooth; regular rasping to keep level

canine teeth

Blind (un-erupted) canine teeth

may cause mucosal irritation/ulceration and biting problems in 4-6yr old males/geldings, occasional female

incision over the un-erupted end encourages eruption

elongated or sharp canine teeth

may cause bit problems

sharp canines enhance bite injuries

can be filed or cut

very rarely a canine tooth requires extraction

due to fracture below the gum line and death of the tooth

canine extraction is difficult such that removal of a healthy canine should be avoided; bone flap approach

wolf teeth

vestigial 1st premolar

may cause bit problems if loose or sharp

routinely extracted at 1-2yrs; loosen with periosteal elevator, extract with forceps

“Blind” wolf teeth may cause subgingival enlargement and bit problems; remove surgically if needed

Premolar “caps”

Deciduous premolars being shed as permanents erupt

these are usually shed naturally; however

permanent P3 and P4 erupt at 3 and 4 years and are prone to crowding with retention/delayed shedding of caps

erupt between permanent P2 and M1 which are already in place

retained premolar caps

may cause a localized gingivitis

often cause painless bony swelling around alveolus (“eruption pseudocyst”)

these usually resolve with shedding / removal

remove caps if they are truly retained

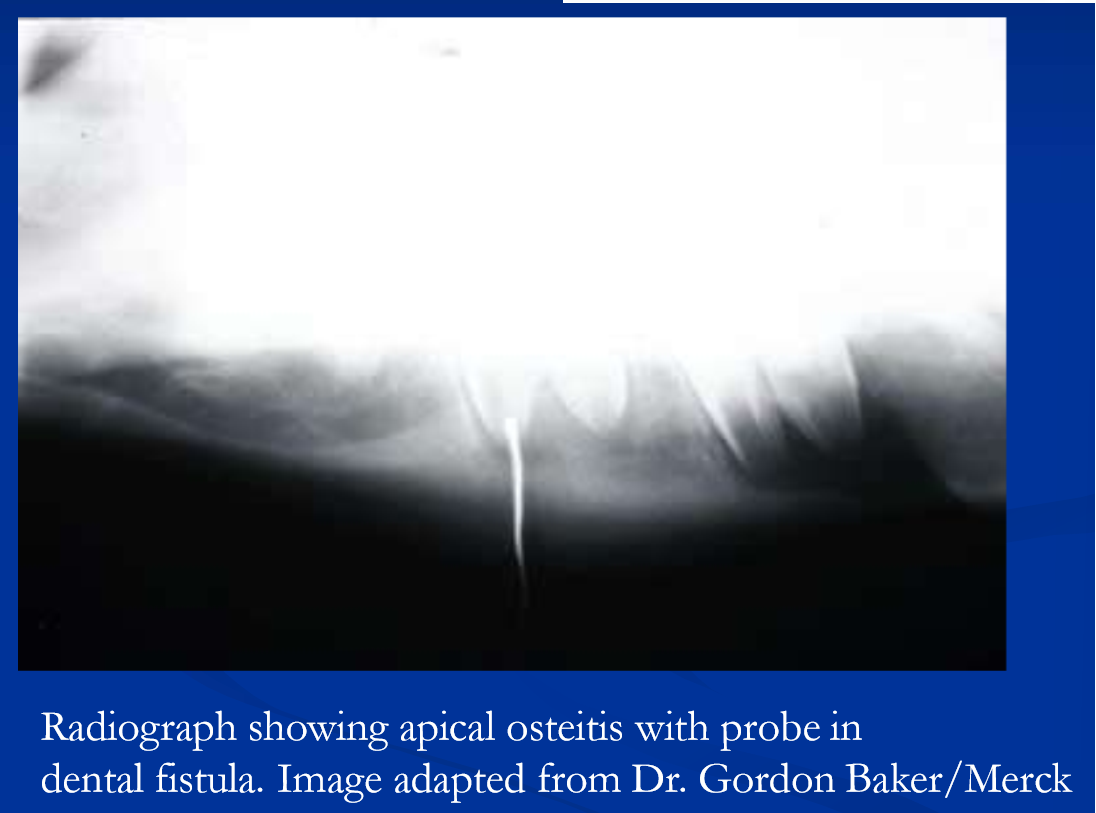

retained premolar caps and apical osteitis

persistently retained caps at P3/P4 can lead to impaction and or displacement of permanent P3/P4

with impaction there is expansion within the alveolus, lysis of supporting bone, and painful bony swelling around apex

with progression the apex and surrounding alveolar bone can become infected (apical osteitis) and eventually the pulp

management of retained caps and apical osteitis

remove retained cap(s)

± oral antibiotics based on presence / absence of painful bony swelling for example sulfas and metronidazole

advanced infection leads to draining tract (mandible) or sinusitis (maxilla) and requires more aggressive intervention

curettage of draining mandibular tracts

sinus irrigation with maxillary sinusitis

systemic antibiotics, often long term

root end resections and apical seal are options

extraction needed if fails to resolve

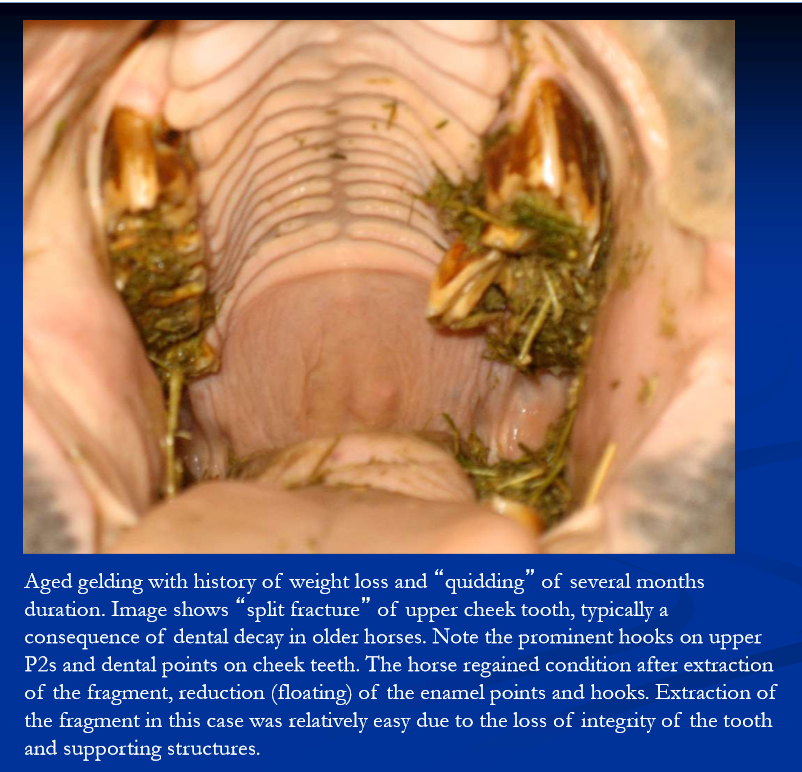

Dental decay / caries

occurs most commonly at the occlusal surfaces of the caudal upper cheek teeth within the infundibula

superficial decay at the surface of these teeth is common / typical generally non-problematic

horses with unusually deep infundibula are prone to more extensive caries that can weaken tooth, promote infection of pulp cavity

larger / persistent caries and infection

weakens the tooth, predisposes to splitting / cracking

infection may extend to root (apices)

endodontic techniques can be employed to seal caries

advanced dz requires extraction of tooth / fragments

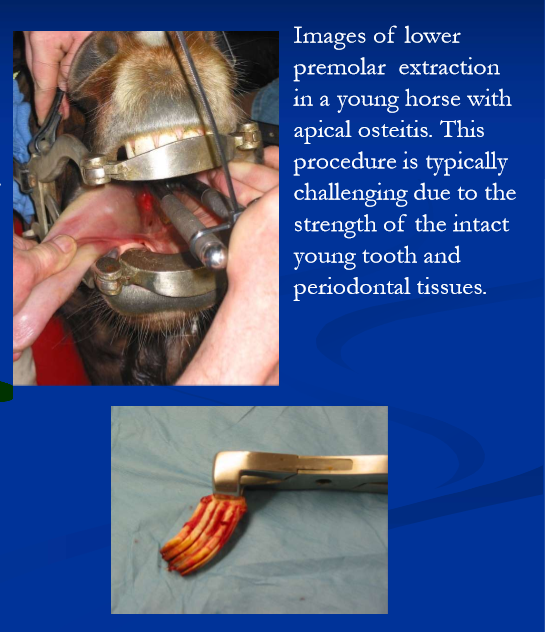

Extraction of cheek teeth

indications include infection, fracture, loose tooth, malposition, dental tumors

extraction can be challenging depending on age of horse, and nature extent and location of disease

intraoral extraction preferred; sinus trephination or sinus flap with repulsion, and lateral buccotomy, are more challenging and prone to complications

Malocclusions of the cheek teeth

wave mouth:

older horses, usually at P4-M1; manage with regular floating

step mouth:

“overgrowth” of cheek tooth because opposing tooth is absent; manage with cutting and or frequent rasping

shear mouth:

excessive angle of the upper and lower occlusal surfaces; related to narrow mandible; causes “tilt” profile of incisors

creates razor sharp teeth causing lacerations of tongue and cheeks; frequent floating of cheek teeth

smooth mouth

extreme wear of crown surfaces in older horses; pelleted feeds and removal of points

Periodontal disease

generally the result of malocclusions

missing teeth, mispositioned teeth, wave mouth, shear mouth, step mouth, large hooks

result in diastema, spaces between teeth that trap feed

progressive inflammation of the gingivae results in

resorption of alveolar bone, degeneration of periodontal membrane, pocket formation and loosening of the tooth

chronically there is tooth decay and tooth loss; also can lead to osteomyelitis of supporting bone

prevention: regular exams / dentistry to maintain normal occlusion

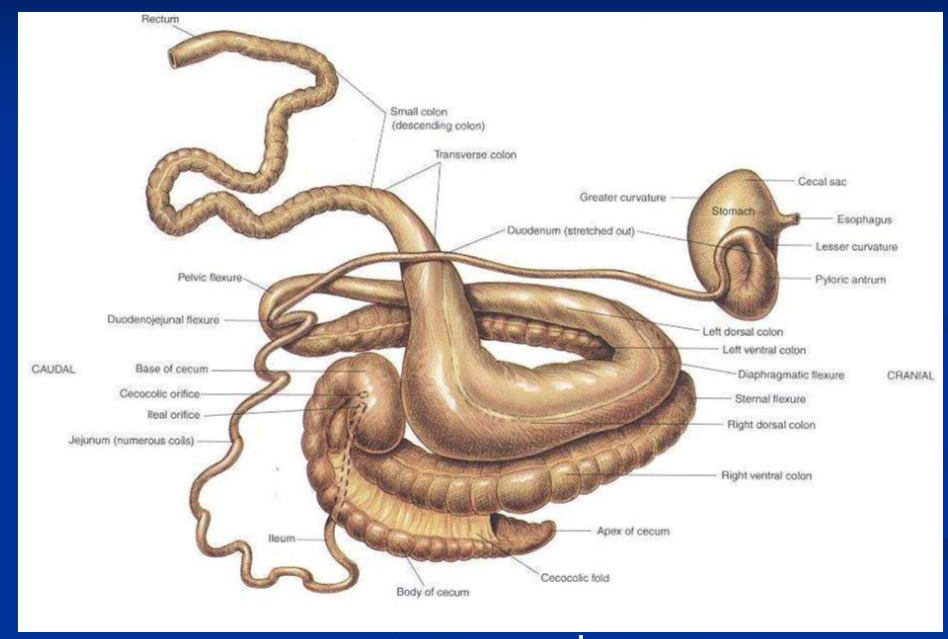

colic in horses

colic = abdominal pain

common but non-specific clinical signs in horses

multiple etiologies and severity

gastrointestinal: many conditions, stomach to rectum

non-GI: peritoneum, liver, urinary and repro tracts

“false colic” signs misinterpreted as abdominal pain, example rhabdomyolysis

accurate diagnosis requires

knowledge of GI structure and function

understanding of pathophysiology of intestinal diseases

systematic approach to examination

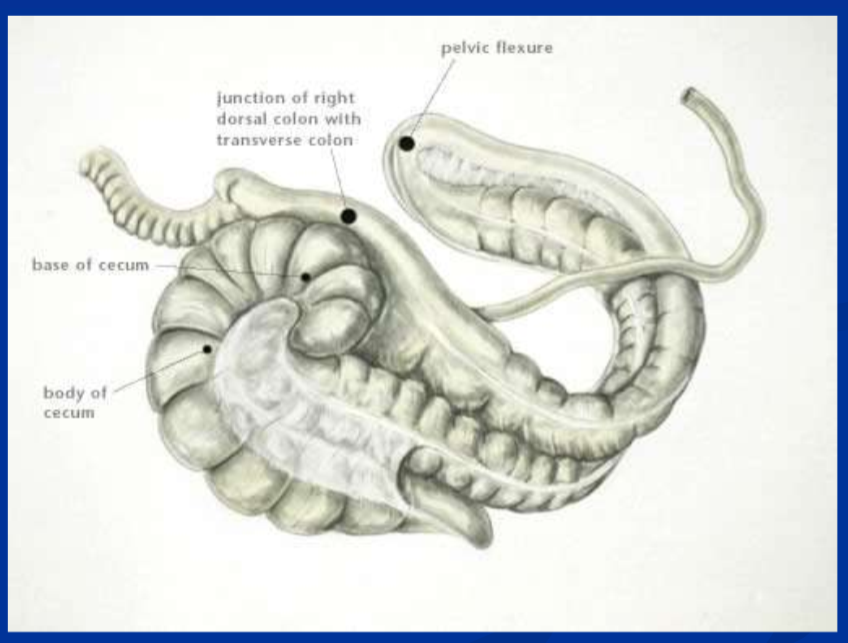

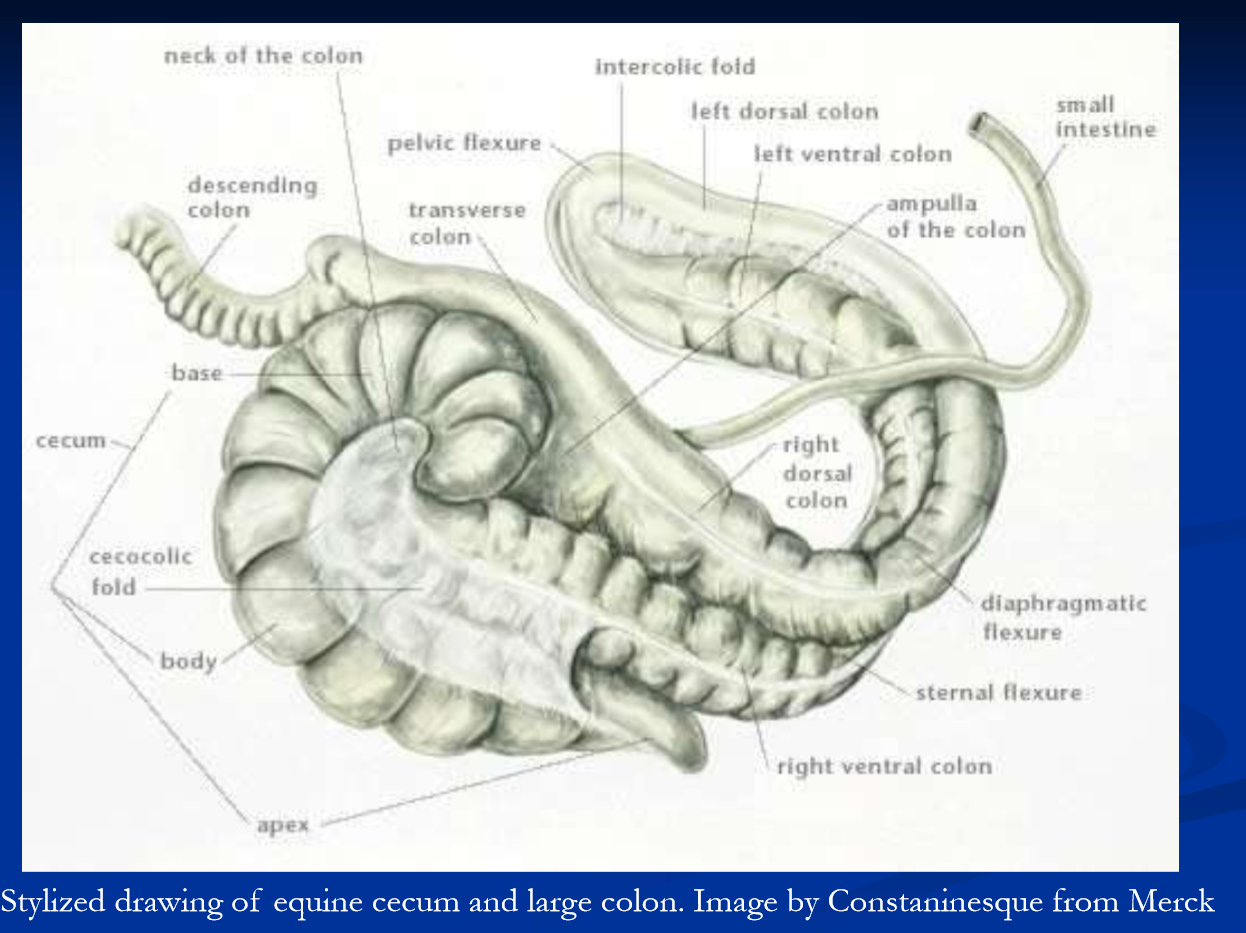

anatomic and physiologic predispositions to GI disease

the stomach is predisposed to gastric dilatation and rupture because the cardia is “one-way valve”

the small intestine is prone to incarceration and strangulating obstructions

large intestines:

important in water balance and nutrition, prone to acute inflammation leading to large fluid loses and PLE

prone to luminal obstruction, displacement, strangulation, and infarction

small colon: prone to intraluminal obstruction, vascular injury

motility patterns, natural openings and blood supply play roles in predispositions to obstruction and ischemic injuries

Mechanisms of intestinal pain

Distension / stretching of intestinal wall

gas, fluid or ingesta; pain receptors in wall

stretching / tension of the mesentery

ischemia

incarceration, strangulation

vascular spasm / thromboembolism / infarction

acute inflammation

intestinal mucosa / wall: enteritis (SI), typhylocolitis (LI)

serosa: peritonitis

mechanisms of intestinal injury: obstruction

anatomical obstructions

simple obstruction

intra-luminal blockage and non-strangulating displacements

causes intestinal distention, tension on mesentery

strangulating obstruction

simultaneous occlusion of the intestine and blood supply

ischemia is usually acute, severe and rapidly progressive, with loss of bowel integrity and progression to devitalization, perforation

torsion, volvulus and incarceration / strangulating entrapment

mechanisms of intestinal injury; inflammation

acute inflammation of the SI causes

Ileus (functional obstruction) fluid accumulation, SI distention, enterogastric reflux, gastric distension, abdominal pain, endotoxemia

acute inflammation of the LI is common and causes

Ileus, fluid leakage and or secretion into lumen, diarrhea and fluid loss, PLE, abdominal pain, endotoxemia

chronic inflammation of SI and or LI causes

malabsorption/ maldigestion, weight loss, sometimes hypoproteinemia

chronic, low volume diarrhea with LI

mechanisms of intestinal injury: non-strangulating ischemia and infarction

classic cause is verminous arteritis associated with S. vulgaris larvae in cranial mesenteric artery and branches

larval activity causes ischemia via arterial spasm, stenosis, and or thromboembolism

results in recurrent transient ischemia and pain or

infarction bowel injury, necrosis secondary peritonitis / perforation

pathophysiology of intestinal disease: cardiovascular compromise

persistent and or progressive intestinal injury and abdominal pain result in circulatory shock due to:

Hypovolemia*

cessation of fluid intake

increase in insensible losses

fluid loss into intestinal lumen

strangulation obstruction

endotoxemia: cardiovascular effects of endotoxin*

depression of myocardial fx, loss of peripheral vascular tone/control (capillaries) => distributive shock

prominent with acute inflammatory or ischemic conditions

Primary (intestinal) endotoxemia

endotoxin is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) component of the outer cell membrane of gram-negative bacteria

LPS is released into the intestinal milieu during normal reproduction and death of G-negative enteric bacteria

in healthy animals, small amounts of endotoxin cross the GI mucosal barrier and enter the portal circulation

scavenged and eliminated by Kupfer cells in the hepatic sinusoids

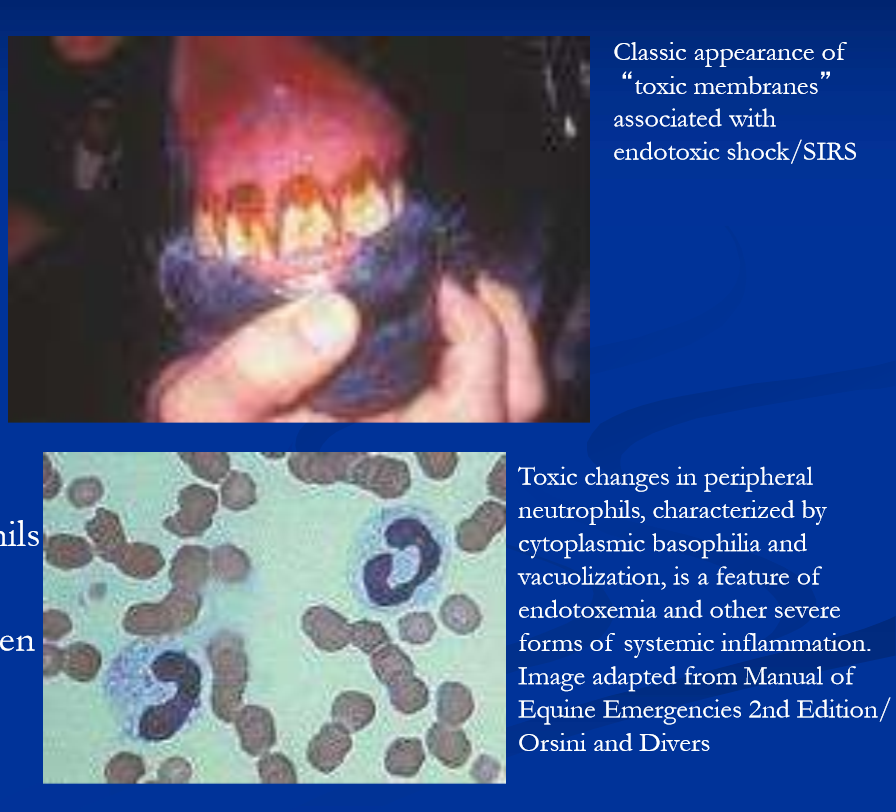

Endotoxemia

Excess amounts of endotoxin in the systemic circulation (endotoxemia) occur via:

gram negative infection (G-neg sepsis)

primary / intestinal endotoxemia*

absorption of excess endotoxin and other bacterial products across damaged GI mucosal barrier, into portal circulation and or peritoneum

occurs especially when there is inflamed or injured bowel

primary / intestinal endotoxemia is common in horses

GI dzs leading to inflammation and or injury are common

horses are highly sensitive to the pathophysiologic effects of endotoxin

endotoxin interacts with mononuclear phagocytes and endothelial cells causing

widespread activation of the arachidonic acid cascade, massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, loss of vasomotor control and activation of the clotting cascade

results in a systemic inflammatory response syndrome

characterized by hypotension, poor tissue perfusion, lactic acidosis and coagulopathy

the terminal events are circulatory failure and DIC

primary (intestinal) endotoxemia

simple GI stasis increases the amount of endotoxin absorbed across the GI mucosa

GI distention, ischemia and or inflammation lead to

breakdown of the intestinal mucosa, resulting in

absorption of excess endotoxin across the bowel wall into the portal circulation

also enter peritoneal cavity when bowel wall is injured, taken up in circulation

Clinical manifestations of endotoxemia

depression

fever

abdominal pain

tachycardia

increased CRT, weak pulses

“toxic “ membranes

hemoconcentration

neutropenia

left shift

toxic change in neutrophils

thrombocytopenia

consumption of fibrinogen

increased clotting times

clinical signs of abdominal pain

restlessness

curling the upper lip

stretching

looking at flank

pawing the ground

kicking at abdomen

crouching

dog sitting

lying down

rolling

tachycardia and tachypnea

sweating

fasciculations

Diagnosis for colic you need to do

thorough examination including

consideration of age, sex and breed

current and past medical history and preventive care

physical exam aimed at determining

the affected segment the intestinal tract

stomach, SI, LI, small colon or extra - intestinal

the nature and severity of the disease process

simple obstruction, strangulating obstruction, inflammation

cardiovascular status of the horse

Age, sex and breed predispositions with colic

Newborn foals

meconium impaction

enterocolitis

uroperitoneum

weanlings / yearlings

gastric ulcers

ascarid impaction

umbilical hernia

SI intussusception

foreign body

adult horses in general

spasmodic

flatulent

gastric ulcers

impaction of large intestine

large colon displacement / volvulus

SI strangulations

typhlocolitis

verminous arteritis

brood mares

parturition, uterine torsion, large colon displacement, large colon torsion / volvulus

stallions

inguinal hernia (common), testicular torsion (rare)

older horses, esp obese

strangulating pedunculated lipoma

miniature horses especially youngsters

large and small colon impaction with sand, dirt, hair and foreign material (bedding)

history for colic

history of current episode

duration, severity and progression of current signs

events surrounding the current episode

appetite, fecal production, water intake/access

response to treatment

prior history and management

use, housing / environment, diet and water source

preventive health care: teeth, parasite control / deworming

changes in management / environment

previous colic or other medical problems

drug history-examples NSAIDs, antibiotics

examination for colic

physical examination aimed at assessment of general condition, severity of pain, GI and cardiovascular status

nasogastric intubation

gastric dilatation and reflux are generally indicative of primary gastritis or SI obstruction

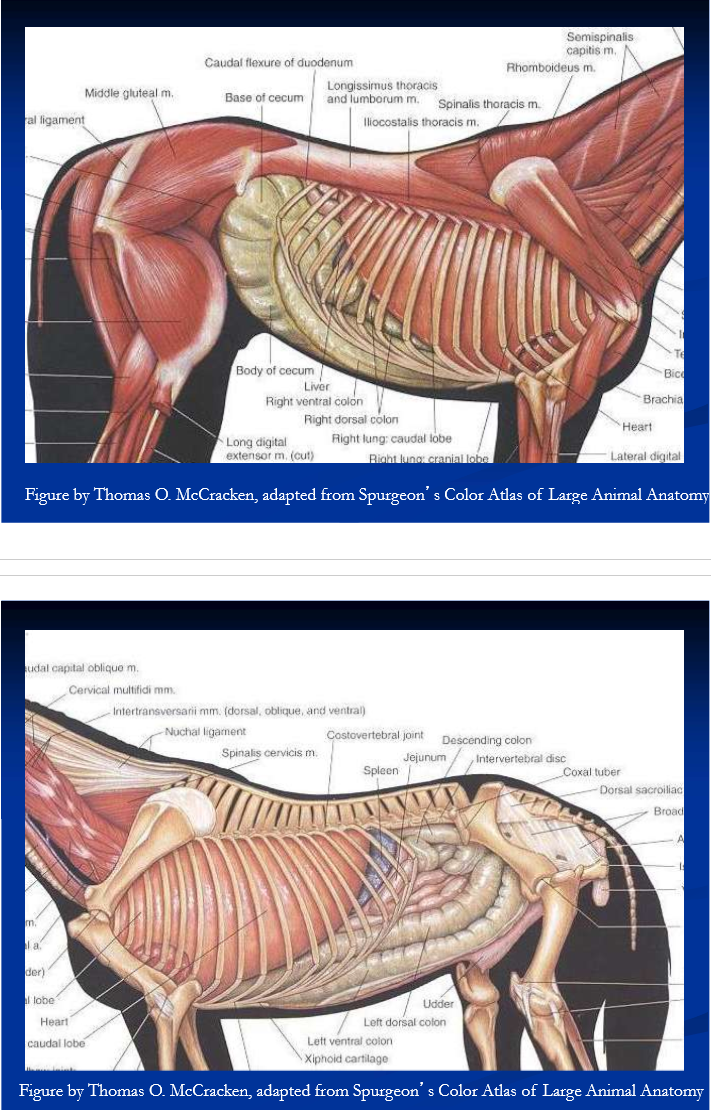

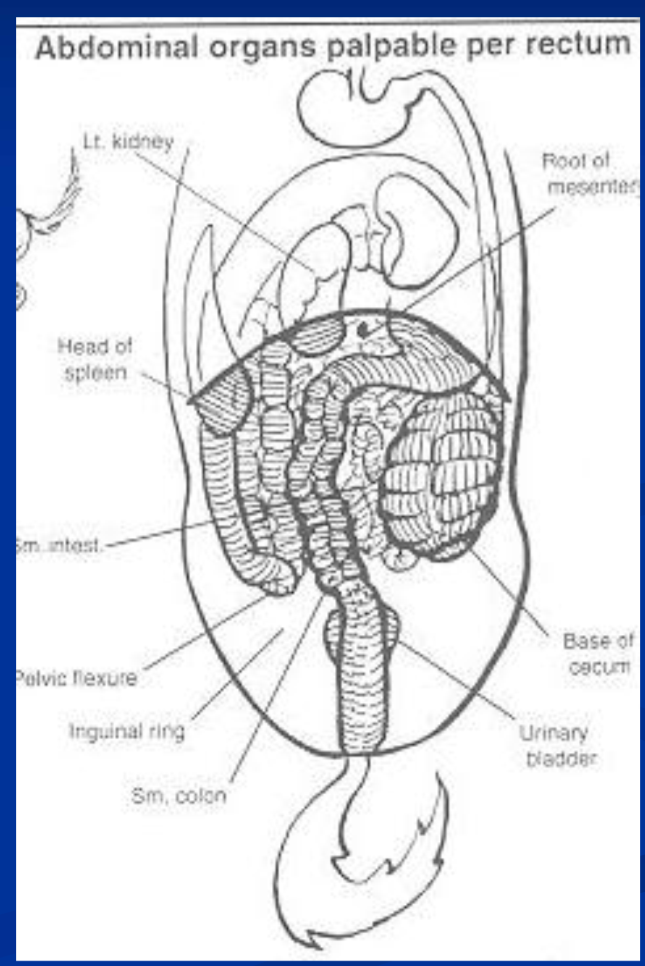

abdominal palpation per rectum can detect anatomical abnormalities

abdominal ultrasound to visualize abdominal structures

abdominal paracentesis can detect bowel compromise and or peritonitis (belly tap)

abdominal palpation per rectum

may differentiate between medical and surgical conditions

use a systematic approach

landmarks / normally palpable structures are the aorta, cranial mesenteric artery, cecal base and ventral cecal band, pelvic flexure, spleen, and left kidney, urinary bladder, inguinal rings in stallions and geldings, ovaries and uterus in mares, peritoneal surfaces

abnormalities seen with colic

dry or absent fecal balls in rectum / small colon

fecal masses of LI, cecum, or small colon

bowel distention; large versus small intestine

tight mesenteric bands

displacement of the spleen

large colon displacements and strangulations

abnormal peritoneal surfaces

abdominal masses

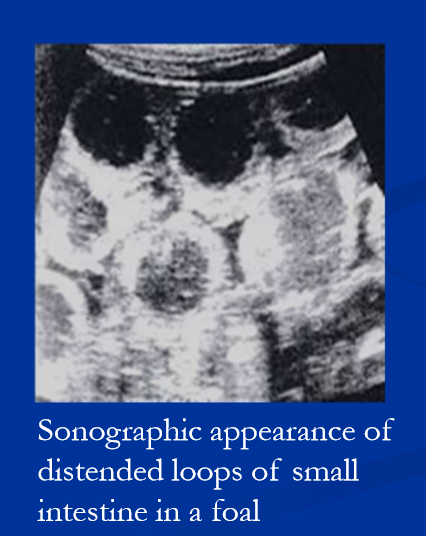

abdominal ultrasound

may differentiate between medical and surgical conditions

trans-abdominal and trans-rectal

detectable abnormalities include

small or large intestinal distention

changes in wall thickness

large colon displacements

sand accumulation in the large colon

small intestinal intussusceptions

inguinal hernia

enterocolitis

right dorsal ulcerative colitis

peritonitis, abdominal hemorrhage

clinical pathology with colic

PCV and total solids help assess hydration / circulatory status; reflect protein losing enteropathy if present

WBC will indicate stress, inflammation, infection and or endotoxemia, aiding diagnosis

biochemical profile, electrolytes, blood gases, and lactate

provides assessment of circulatory status, guides fluid therapy

evaluation of organ function

peritoneal fluid analysis* to assess intestinal integrity; also reflective of extra-intestinal disease

peritoneal fluid analysis for assessment of bowel integrity / intestinal compromise

normal peritoneal fluid is light yellow and clear, WBC <5000/ul, protein <2.5g/dl

generally remains WNL with simple LI obstructions

vascular comprise (prolonged distention, incarceration, strangulation) leads to progressive changes

serosanguinous color (RBCs)

increases in WBC and protein (turbidity)

toxic changes in neutrophils as bowel wall becomes compromised (leakage of endotoxin)

dark fluid as bowel becomes necrotic, degenerate neutrophils

brown or green color, bacteria and plant material when bowel ruptures

principles of intervention with colic

relief from pain

analgesics: xylazine / butorphanol, flunixin; detomidine

gastric decompression, cecal trocharization

cardiovascular stabilization

volume expansion with IV fluids

counteract effects of endotoxin

fluids, flunixin, plasma, polymyxin B

ultimate goal: establish patent, functional intestine

fluids, laxatives and cathartics

surgical intervention (laparotomy)

Indications for surgical exploration with colics

Clinical signs and progression are monitored over time

duration, severity and progression of pain, response to analgesics, rectal examination findings, naso-gastric intubation, peritoneal fluid analysis, and cardiovascular status

surgical intervention is indicated with

progressive, severe and or unrelenting pain

obvious surgical lesion detected on rectal exam or US

progressive changes in abdominal fluid

progressive cardiovascular deterioration

unsatisfactory response to medical management

pre-surgical and anesthetic considerations

stabilize CV status prior to induction

horse is compromised, anesthesia causes further hypotension

volume expansion / perfusion

peri-operative antibiotics, anti-inflammatories

penicillin-gentamicin, flunixin

consider renal perfusion/function when giving these drugs

NG tube in place

Xylazine-ketamine-GG / diazepam induction, maintained on gas; goals are to maintain BP and limit time under anesthesia, myopathies are the primary risk

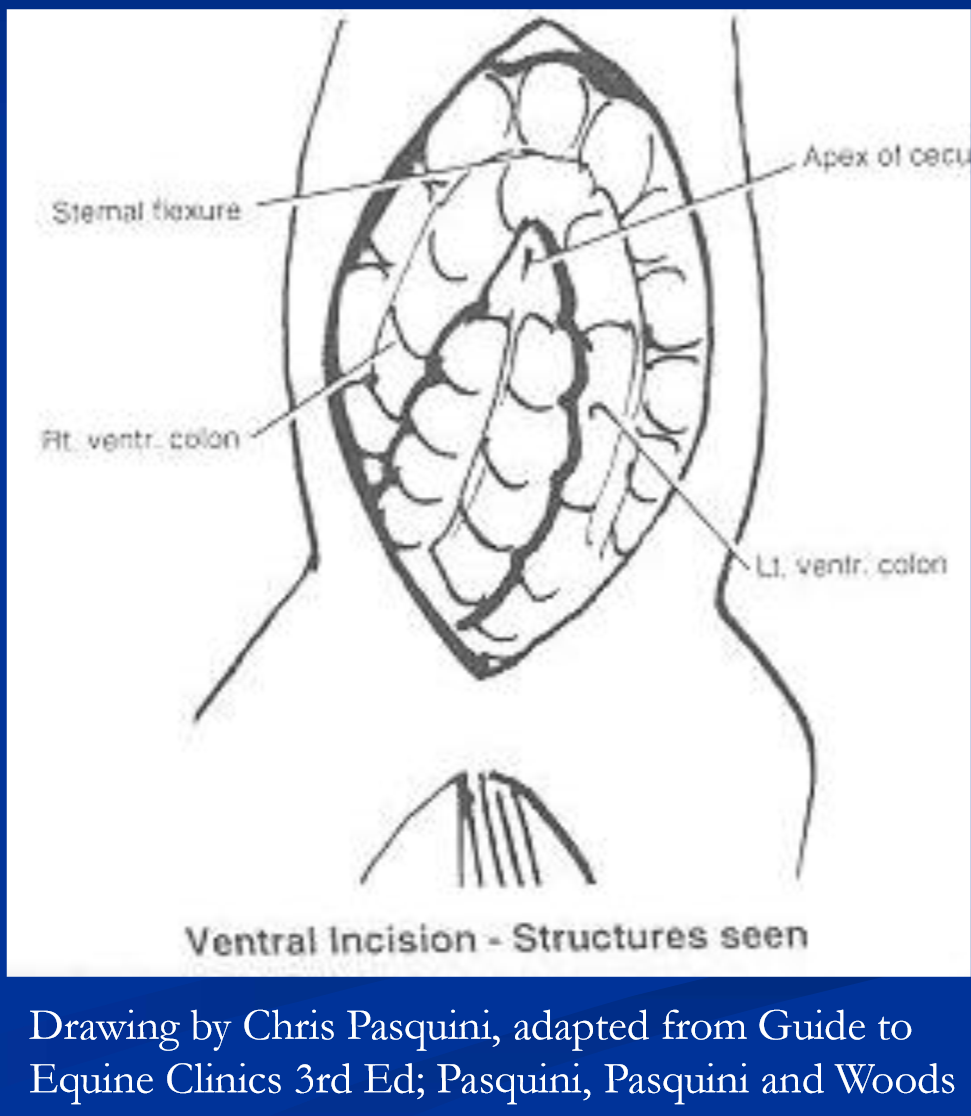

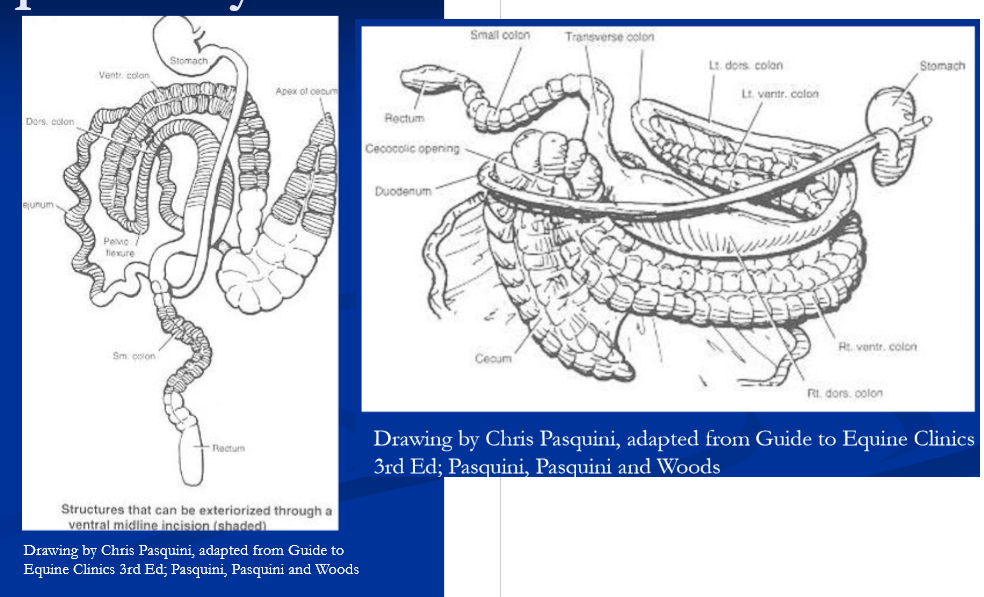

Exploratory laparotomy

ventral midline incision, xyphoid to umbilicus

initial inspection: apex of cecum should be on ventral midline, surrounded by ventral colon / sternal flexure

look for discolored peritoneal fluid, fibrin on serosal surfaces, ingesta free in peritoneum

decompress any distended intestine

problem may be evident on initial inspection

explore further by sweeping hand over viscera in all quadrants

looking for distended loops of bowel, tight mesenteric bands, firm ingesta/fecal masses intra-abdominal masses

detailed exploration

feel root of mesentery and connections of cecum and colon for volvulus

LI: check position by starting at cecum → ventral colon → pelvic flexure; nephrosplenic space

run SI, palpate liver, right kidney, epiploic foramen

exteriorize the colon and examine

palpate / examine small and transverse colons

decompression of distended SI and

resection-anastomosis if needed

pelvic flexure enterotomy to evacuate colon

close abdominal wall with #2 absorbable (vicryl) methods vary; suture / staple skin; belly bandage

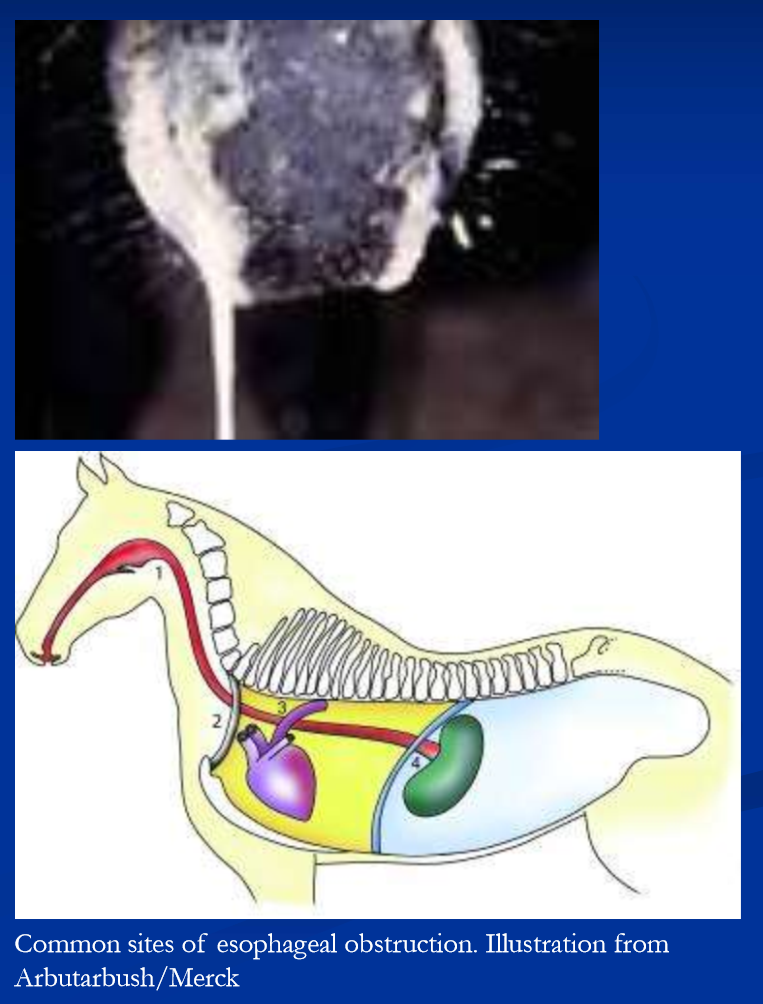

esophageal obstruction

primary obstruction = intraluminal obstruction with feed or foreign body

feed obstruction is the common form, referred to as “choke” or “simple choke”

causes / associations/ predispositions for simple choke are

dental problems

course hay

grain, pellets or beet pulp eaten greedily

physical exhaustion (feeding immediately after a workout)

any cause of generalized weakness (example botulism)

pharyngeal dysfunction

previous choke

additional causes of esophageal obstruction include

stricture

diverticulum

intramural masses example tumor (SCC), abscess/granuloma

extramural mass; cervical and mediastinal abscess, granuloma, or tumor

peri-esophageal scar tissue

functional obstruction: motility disorder and or mega-esophagus

primary obstruction with feed (simple choke)

signs: are saliva and or feed from nose after being fed, anxious expression, extended neck, gagging, retching, coughing

high cervical, thoracic inlet, heart base, cardia are common sites

site of obstruction identified by passing NG tube or endoscope

also can palpate cervical obstruction

endoscopy*, ultrasound, radiology to visualize

management of simple choke

goals are to resolve the obstruction, manage complications, determine and eliminate the cause

remove feed and water to avoid aspiration

mild choke may resolve spontaneously

sedation can relieve anxiety and promote relaxation to encourage spontaneous resolutions; ex xylazine / acepromazine

however, prolonged obstruction (>4-6 hrs) increases the risk of esophageal damage, perforation and aspiration

manual reduction via esophageal lavage is generally indicated (dont let the sun set on a choke)

lavage via stomach tube and warm water

requires a-traumatic approach and patience

sedate to relax horse and drop head to avoid aspiration*

with tube placed proximal to obstruction repeatedly administer and drain small volumes of water to break up feed

can massage bolus if in cervical esophagus

special double lumen tubes are available

can place cuffed naso-trahceal tube to avoid aspiration

*do not forcibly push the obstruction aborad

refractory / more severe impactions may require

irrigation under general anesthesia or

esophagostomy

after relieving obstruction endoscopic exam to evaluate the degree of mucosal/esophageal injury is ideal

for uncomplicated choke (minimal mucosal injury)

complete feed restriction for 24-48hours* (provide water

*esophageal motility is temporarily compromised subsequent to choke, predisposing to re-obstruction

re-feed with slurry initially for up to 7 days gradually return to normal diet depending on initial damage/progress

complications of simple choke

acute complications include

mucosal injury / ulceration (esophagitis)

perforation (these dont do well depending on location)

aspiration pneumonia

dehydration and electrolyte depletion with prolonged chocke

manage with fluids, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, surgery as needed

chronic complications are stricture, diverticulum, megaesophagus, recurrent obstruction

prevention

proper dental care; alternative diets for aged / poor dentition

dont feed horses immediately after workout

avoid competition for feed

Esophagostomy

employed rarely for cervical obstructions

refractory esophageal feed obstruction

foreign body retrieval

performed standing or under general anesthesia

place NG tube prior

longitudinal esophagotomy over or below obstruction

primary closure if esophageal tissue is healthy

otherwise, delayed closer / second intention, feed esophagostmy (stomach tube in place

antibiotic treatment indicated / necessary

can be employed for healing of esophageal injury, or perforation from choke or foreign body

also provides a means of enteral feeding in case of oropharyngeal disease that preclude oral intake

esophagostomy placed below damaged site

NG tube placed though esophagotomy site and sutured in place 2nd intention healing upon removal may fail to heal from fistula

esophageal perforation

result of long-standing obstruction with feed, intra-luminal foreign body, NG tube, external penetration

acute cervical perforation is potentially repairable if attended quickly and drainage established

diagnosis aided by endoscopy, US, radiographs, contrast

primary closure if possible

otherwise, must heal by 2nd intention, guarded prognosis; place esophagostomy tube below for feeding

intrathoracic perforation is fatal

severe, acute septic mediastinitis

Esophageal strictures

usually the result of acute obstruction

also external trauma, reflux esophagitis, congenital

signs are recurrent obstruction

diagnosis with endoscopy, contrast radiography

bougienage techniques, endoscopic and other

surgical techniques include

esophagomyotomy, partial or complete resection - anastomosis and patch grafting

prevention is

diligent management of primary obstruction thorough post-obstruction evaluation and prolonged feeding of low-bulk diet when indicated

Esophageal diverticulum

pulsion diverticulum

protrusion of mucosa and submucosa thru defect in the muscular wall, generally result of simple choke; has narrow neck / flask-like shape; fills with feed and leads to obstruction; diverticulectomy for correction

traction diverticulum

consequences of scar tissue from perforation or other cervical injury, or esophagotomy / ostomy

contraction of scar tissue and traction on esophageal wall

leads to localized shallow diverticulum with wide neck

signs are intermittent, usually transient obstruction

generally causes minimal difficulty cna live with it

Esophageal motility disorders

Megaesophagus is usually an acquired condition

prolonged obstruction (choke) may lead to permanent hypomotility and megaesophagus

can be a consequence of stricture or diverticulum

Idiopathic megaesophagus in Freisian horses

maybe as complication of neurological dz, example dysautonomia (grass sickness)

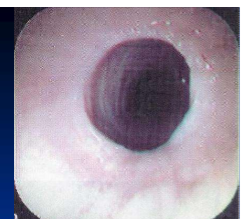

dilated, hypomotile esophagus on endoscopy

treatment options limited; elevate forequarters when feeding identify and treat any primary disease

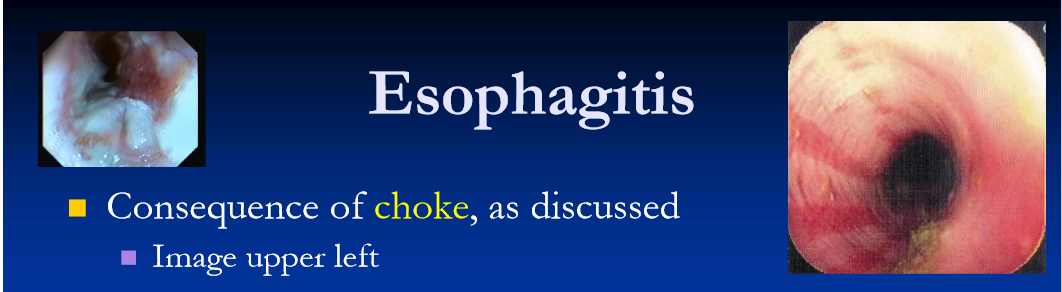

Esophagitis

Consequence of choke,

reflux esophagitis

chemical injury from reflux or gastric acid/bile salts, affecting lower esophagus

complication of gastro-duodenal ulceration in foals (mostly) causing pyloric stenosis and gastric outflow obstruction

other causes of RE are SI obstruction causing entero-gastric reflux, gastritis and or gastric dilatation of any origin esophageal and gastric motility disorders incompetence of lower esophageal sphincter

chemical injury from drugs (ex PBZ), toxicants, toxins (ex cantharidin)

other esophageal conditions

Neoplasia

squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

occurs in association with stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus and stomach; esophageal SSC may present as choke

congenital abnormalities

rare

idiopathic megaesophagus in Friesians

persistent right aortic arch vascular ring anomaly (stricture)

4th bronchial arch defect

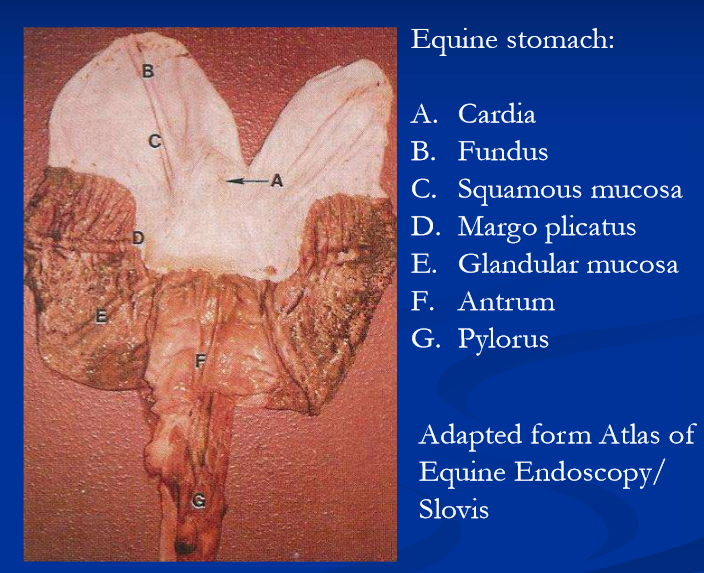

Disorders of the stomach

gastric ulceration

gastric dilation

grain overload

gastric impaction

gastric rupture

neoplasia

Equine gastric ulcer syndrome

common condition and cause of poor performance and or ill-thrift across domestic equine populations

occurs in all ages, sexes, breeds and classes

performance horses are at highest risk

prevalence varies (11% go 90%)

etiopathogenesis is incompletely understood

multifactorial including confinement, feeding practices, NSAIDs and a variety of physiological and social stressors

clearly intensive management practices associated with training and performance are major contributors

clinical signs in adult horses for gastric ulcers

in adult horses, signs are vague and non-specific, and most cases go unrecognized; common complaints are

reluctance / refusal to work*

anxious demeanor “grouchy”

aversion to cinch, touching flank

diminished appetite

sometimes loss of condition

some (minority) show abdominal pain, typically as recurrent bouts of mild-moderate, intermittent colic

EGUS may be the most common cause of recurrent colic in adult horses

equine gastric ulcers syndrome in foals

very common and believed associated with illness, physiologic and or psychic stress in early life

common in neonates and suckling foals with diarrhea

lack of maternal interaction in neonatal period/ early life due to illness or death of dam, or illness of foal

stress of weaning psychosocial stress and disease

NSAIDs foals appear more sensitive to toxic effects

glandular and pyloric disease may be more common in foals vs adults

as with adults, most cases are subclinical

in clinically evident cases, signs and complications tend to be more pronounced / severe compared to adults

poor appetite / suckling behavior

abdominal pain*

colic after suckling

recumbence rolling up on back

abdominal pain can be marked and or persistent

Bruxism and ptyalism suggest advanced disease and many indicate ulcerative duodenitis

Diagnosis for equine gastric ulcers

clinical diagnosis response to treatment

condition is common, especially in athletes, stressed adn or sick horses, and horses on NSAIDs

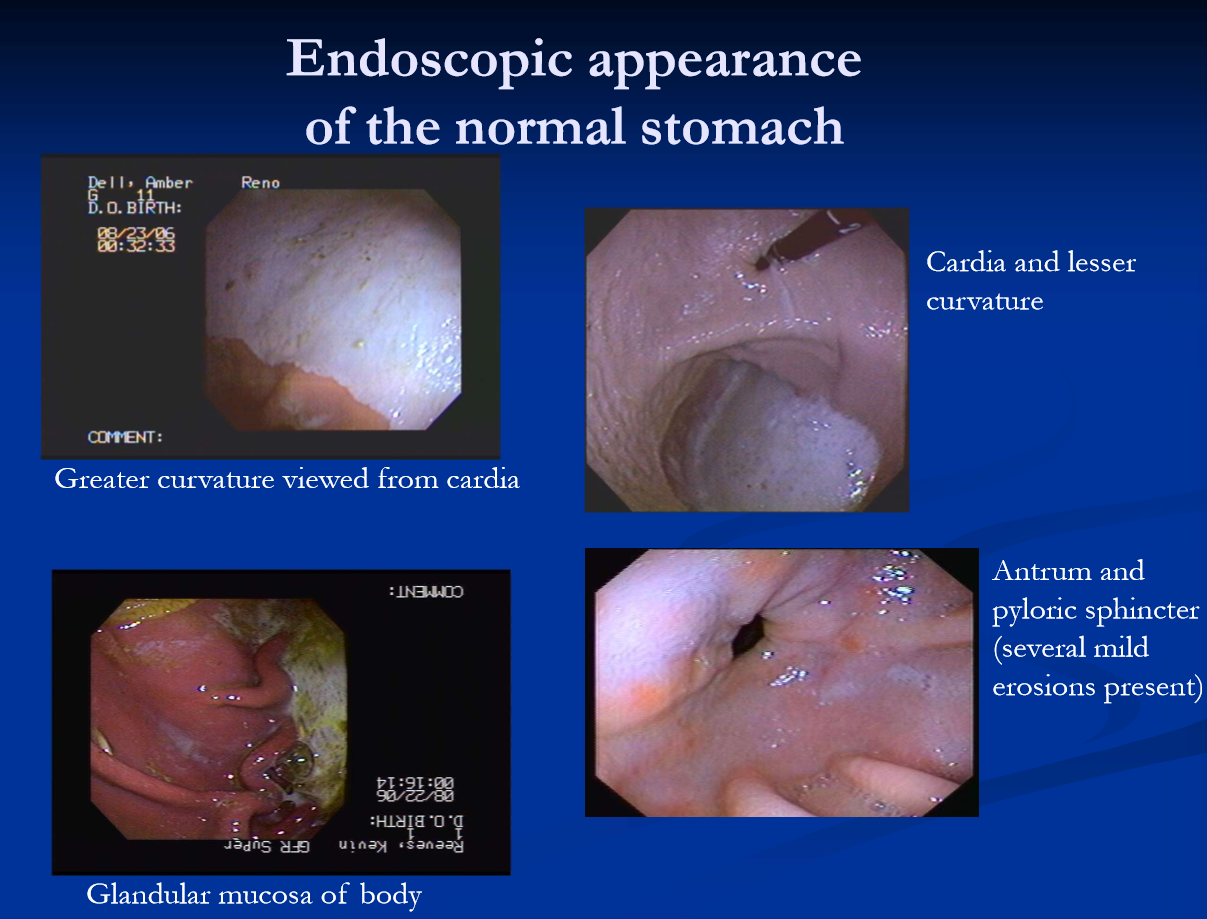

endoscopic examination of the stomach is definitive (and ideal)

requires 2.5-3m scope

graded based on severity

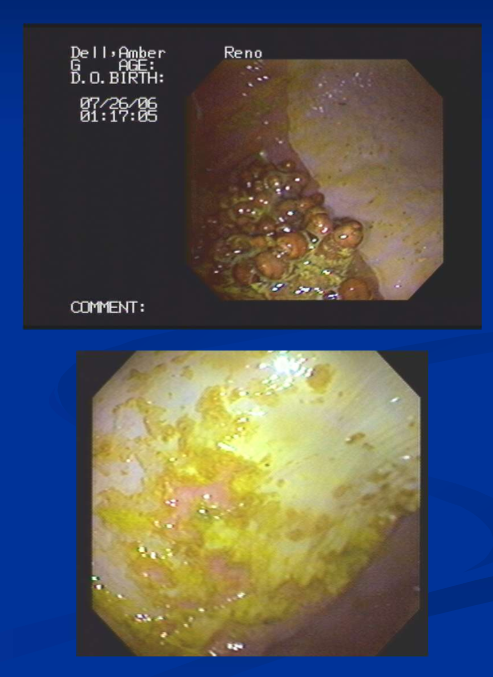

endoscopic appearance of gastric erosion and ulceration

top: mild hyperkeratosis of squamous mucosa adjacent to margo plicatus, indicating mild erosive disease (gastrophilus larvae are observed on the adjacent glandular mucosa)

below: extensive erosion of squamous mucosa with sloughing of epithelium

top: severe diffuse squamous ulceration involving lesser curvature

below: thickened, hyperkeratotic appearance of deep, focal squamous ulcers in the chronic phase

general principles of management of gastric ulcers

management changes****

take athlete out of work when possible

reduce confinement / increase turnout

change diet: free choice hay/pasture, stop grain

for non-athletes ID and eliminate stressors, illness

stop any NSAID use

pharmacologic suppression of gastric acidity

anti-ulcer drugs (acid suppressive therapy)

horses with clinical squamous ulceration uncomplicated by glandular disease

proton pump inhibitor omeprazole (Gastroguard, Boehringer-ingelheium)

4mg/kg q 24hrs for 28 days

recheck gastroscopy at 28 days

H2 receptor antagonists (ranitidine preferred, currently unavailable*)

off label use in US common

oral tablets

recheck gastroscopy at 4-6 weeks

H2 agonists work well and are inexpensive

off label pantoprazole and famotidine protocols also exist

injectable formulations very useful in managing EGUS in foals

horses with glandular disease

Omeprazole (gastroguard)

sucralfate 12mg/kg orally q12h

treat for 4 weeks, recheck gastroscopy

frequently need continued treatment and treatment failures are common after 8 wks consider alterantives

alternatives are injectable omeprazole and misoprostol these are off label usages

in refractory cases, management changes are critical including various means of enrichment to address psychosocial aspects

management of foals with EGUS, gastroduodenitis

foals with clinical signs (colic) often have extensive disease, including glandular ulceration adn or duodenitis; gastroscopy

treat any primary dz, identify adn eliminate physiologic and social stressors, eliminate any NSAID use

treat aggressively with anti-ulcer drugs, including injectable IV pantoprazole and oral sucralfate

with suspected duodenitis / gastric outflow obstruction, motility modifiers ex bethanicol, metaclopramide

some require pyloric bypass surgery to relieve outflow obstruction; gastroenterostomy; guarded prognosis

note: incidence and clincal consequences of ulcerative duodenitis in adults is not well documented

preventive use of ulcer drugs

intermittent use in performance horses

stressful events such as weaning, shipping

sick, hospitalized horses

maybe horses on NSAIDs

Gastric dilatation

primary gastric dilation: risk/ complication of carbohydrate overload “grain overload)

ingestion of excess amounts of highly fermentable feed

grain, extruded feeds, rich alfalfa, lush pasture

results in excessive gas production, gastritis and fluid production

Secondary gastric dilation: result of small intestinal obstruction

leads to enterogastric reflux

likely the most common cause of gastric dilation

in either case the risk is gastric rupture (fatal)

horses have small stomach relative to body size (8-10L) perhaps 20 liters when maximally distended

no mechanism for regurgitation / vomiting (lower esophageal sphincter is normally one way valve)

gastric dilatation clinical signs and diagnosis

signs are abdominal pain, NG reflux, caudally displaced spleen, gastric dilatation, distended SI with secondary

Dx/evaluation: nasogastric intubation, rectal exam, ultrasound

primary gastric dilatation / CHO overload may present with history of exposure, acute and progressive abdominal pain, gastric rupture or enterocolitis

horses with secondary gastric dilatation have distended small intestine and other signs of SI dz depending on cause/type

management of gastric dilation

gastric decompression via nasogastric tube

dilation secondary to SI obstruction recurs until SI problem is resolved

leave tube in place and work up case

grain overload (carbohydrate overload)

horses gains access to the grain bin

corn, barley, oats, sweet feed, commercial pellets

also rich alfalfa and lush pasture

may present as acute gastritis and gastric dilation

characterized by acute progressive abdominal pain and gastric reflux; gastric rupture is a major risk and fatal

severe cases evolve into a syndrome of enterocolitis, often severe with lactic acidosis, endotoxemia and laminitis

management of known or suspected grain overload

assess the situation critically / carefully in order to determine the level of exposure

pass NG tube to assess stomach contents / gastric pressure; attempt gastric lavage

with no clinical signs (colic/GD), treat as follows:

mineral oil under gravity flow

NPO for 24 hours; monitor closely for 72 hrs

if colic, reflux and or toxemia are present, decompress adn plan for intensive care

Gastric impaction

uncommon, poorly defined, fair to poor prognosis

defined as dehydrated mass of ingesta retained beyond 16 hours of abstinence

possible predispositions

poor dentition

course roughage (oat hay, straw), beet pulp, bran

possible sequelae to gastritis / grain overload

persimmon seed phytobezoars are a known specific cause

gastric squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Fresians appear predisposed via inherent motility issue

usually vague signs of poor appetite, maybe mild, intermittent colic; rarely acute abdominal crisis

gastric impaction: diagnosis and management

abdominal ultrasound: large radius of stomach curvature and splenic displacement; gastroscopy

medical tx for impacted feed is oral hydration with crystalloid solutions

oral infusion of carbonated beverage for persimmons

may be dx-ed at exploratory laparotomy; transmural hydration and massage of mass followed by medical tx

prognosis for idiopathic impaction with gastric enlargement is guarded risk of recurrence rupture

gastric rupture

terminal event of acute gastric dilation or gastric impaction

other possible causes and predispositions not clearly defined; perhaps mural disease ex stomach worms, gastric SCC

rupture results in acute septic peritonitis, rapid development of endotoxic shock and death

typically presented in severe endotoxic shock with history of abdominal pain or found dead

diagnosis on ultrasound, abdominocentesis, necropsy

euthanasia

Gastric neoplasia

squamous cell carcinoma is the most common form of gastric and esophageal neoplasia in horses

generally teen-aged and older

arises from the squamous epithelium of stomach / esophagus

may become transmural and invade adjacent organs

weight loss and or chronic colic; choke with esophageal

Dx: gastroscopy/biopsy, maybe peritoneal fluid analysis

poor prognosis

small intestinal obstruction

in general SI obstruction causes gas and or fluid distention of the SI, enterogastric reflux, gastric distension, and abdominal pain.

causes: adynamic ileus, intraluminal obstructions, incarcerations, intussusceptions, adhesions, and various strangulation obstructions

strangulating obstruction leads rapidly to bowel compromise, peritonitis, and CV compromise; prompt sx intervention is needed

further most simple SI obstructions eventually lead to bowl injury and usually require surgical intervention

signs of obstruction:

abdominal pain

nasogastric reflux

SI obstruction

adynamic ileus

inhibition of propulsive bowel activity results in functional obstruction

causes are:

post-operative complication of laparotomy, especially for SI dz

enteritis

peritonitis

neonatal weakness / hypoxemia syndromes

managed with treatment of any primary disease, decompression via NG tube, ± motility drugs

*without a specific diagnosis / functional cause, signs of SI obstruction should prompt exploratory laparotomy

simple intraluminal obstructions of the small intestine

ascarid impaction

jejunal obstruction in weanling aged foals

often precipitated by deworming foal with heavy burden

medical tx early is possible; guarded px for surgical dz

ileal impaction

coastal (Bermuda) hay and tapeworms are risk factors

gradual progression (hours) of SI distention and colic

generally a surgical condition, although medical management is possible with early diagnosis/intervention

foreign bodies

baling twine, plastic bags, more; surgical in most cases

SI incarcerations

epiploic foramen entrapment; cribbing is a risk factor

mesenteric rents: SI becomes incarcerated via teras in mesentery or gastrosplenic ligament becomes fluid filled and engorged prone to volvulus

inguinal entrapment in stallions (inguinal hernia): post breeding or heavy exercise; some breed predispositions

umbilical and inguinal hernias in foals, body wall defects, diaphragmatic hernia

these are surgical conditions presenting as gradually progressive (hours) SI distention and abdominal pain

SI intussusceptions and adhesions

Intussusceptions

jejunum, jeunual-ileal, ileo-ileal, ileo-cecal

perhaps more common in young

perhaps associated with hypermotility/enteritis

tapeworms may be associated with ileocecal intussusception

surgical and may require resection-anastomosis

intestinal adhesions

complication of laparotomy, esp SI obstruction / resection

any cause of peritonitis

localized or focal bowel injury ex infarction / parasites

post-surgical adhesions present later with colic / distended SI

surgical intervention; px depends on location and extent

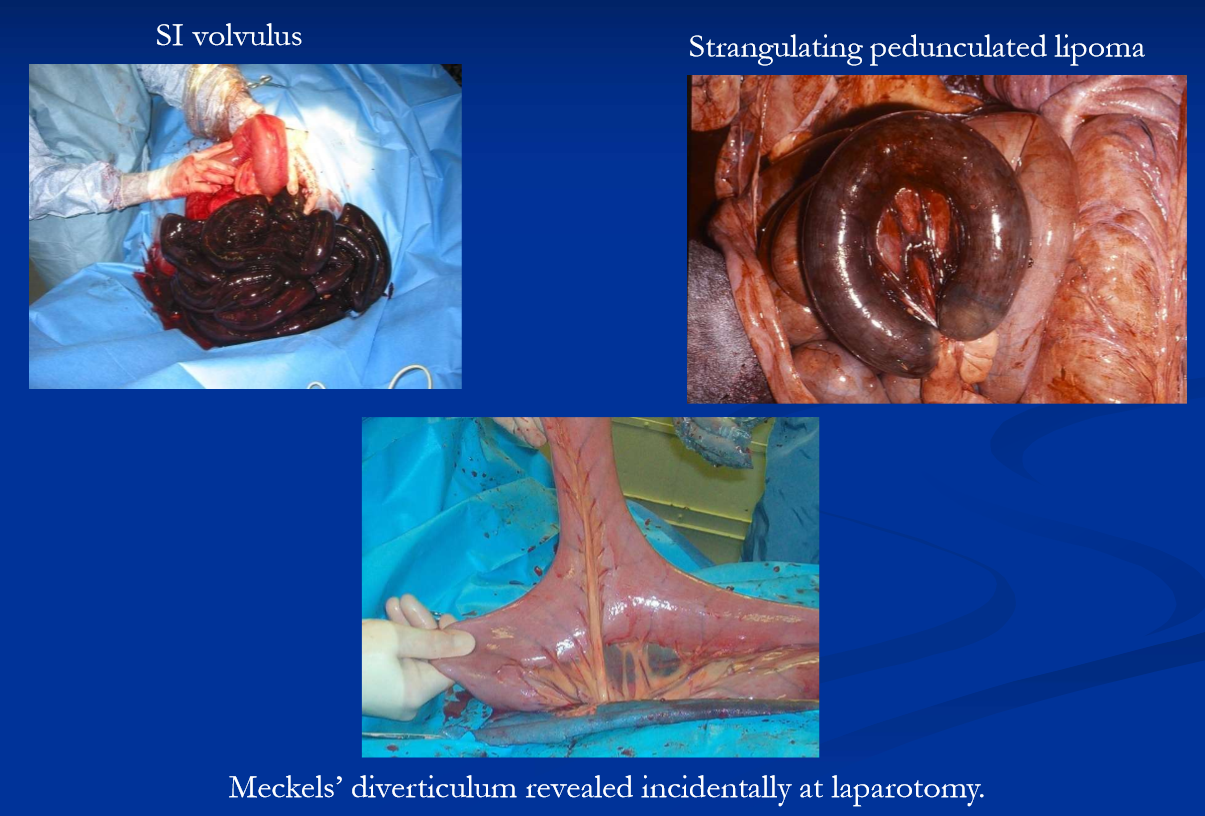

Strangulating small intestinal obstructions

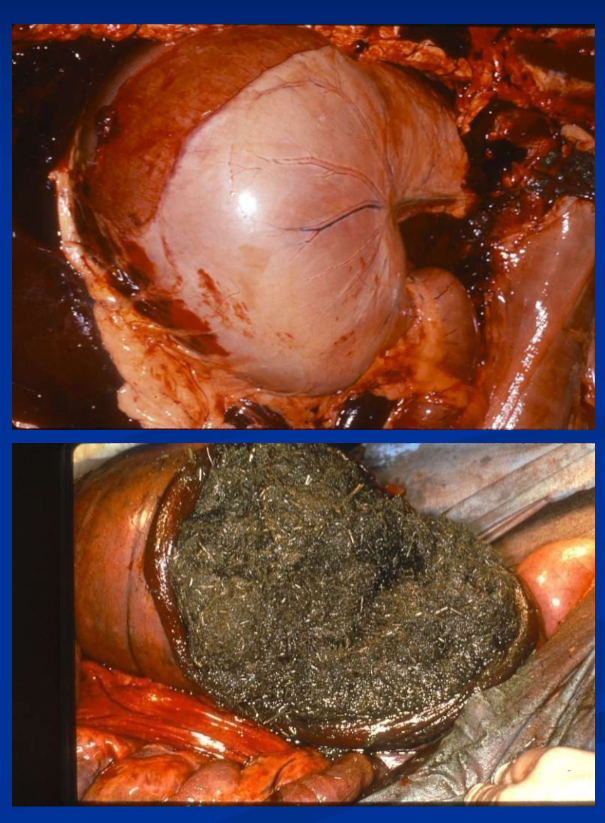

strangulating pedunculated mesenteric lipoma

mature horses, especially older overweight mares

small intestinal volvulus; all ages, unknown etiology

strangulation / torsion / volvulus associated with Meckels diverticulum

these present as acute, persistent and progressive abdominal pain and require prompt surgical intervention

obstructive conditions of the large intestine

large colon and cecal impactions

sand accumulation

ureterolithiasis

LC displacement

large colon volvulus

intussusception

obstructive disease of the large intestine cause abdominal pain and include simple (intraluminal) obstruction, nonstrangulating displacements and strangulating obstructions (torsion, volvulus, intussusception). most intraluminal obstructions with course or dry ingesta (impactions) are treated medically. severe or persistent impactions, large accumulations of sand, enterolithiasis, most non-strangulating displacements and torsion/ volvulus require surgical correction

impactions of the large intestine

accumulation of firm desiccated ingesta in the lumen of the LC or cecum, resulting in physical obstruction

water restriction*, stall confinement, poor dentition, course roughage, sand, NSAIDs, and stress are predispositions

can occur as a complication of any disease that causes reduced fluid intake or fluid loss

LC impactions are most common, and initially arise at sites in where luminal diameter narrows, ie pelvic flexure and or transverse colon

impacted ingesta and gas accumulate orad to these sties, leading to gas distention of large intestine and thus pain

cecal impactions are less common; some may involve motility disorder

Large colon impaction

usually there is intermittent, mild to moderate abdominal pain and abdominal distention

mass of firm ingesta palpable when left colon involved

generally these horses remain physiologically stable and are managed medically

advanced cases may become complicated showing persistent / progressive pain and cardiovascular deterioration and may require surgical intervention

most can be managed medically

restrict feed and provide water

control pain

oral and IV fluids

laxatives and cathartics

mineral oil, DSS, psyllium, MgSO4 / NaSO4

surgery indicated with progressive pain and or failure of medical treatment (not typical)

evacuation of colon through pelvic flexure enterotomy

good prognosis in general; sx cases more complicated

cecal impaction

firm ingesta filling cecum

risk factors / predispositions as with LC impaction but

some are associated with orthopedic sx, prolonged hospitalization and NSAID use and

some may involve a primary motility disorder

diagnosis by abdominal palpation per rectum

medical tx if early; aggressive fluids and laxatives

surgery sooner rather than later; spontaneous perforation with minimal premonitory signs can occur

typhylotomy and evacuation

true motility disorder is considered a progressive condition that will culminate in cecal rupture without surgery; cecal bypass via ileocolostomy

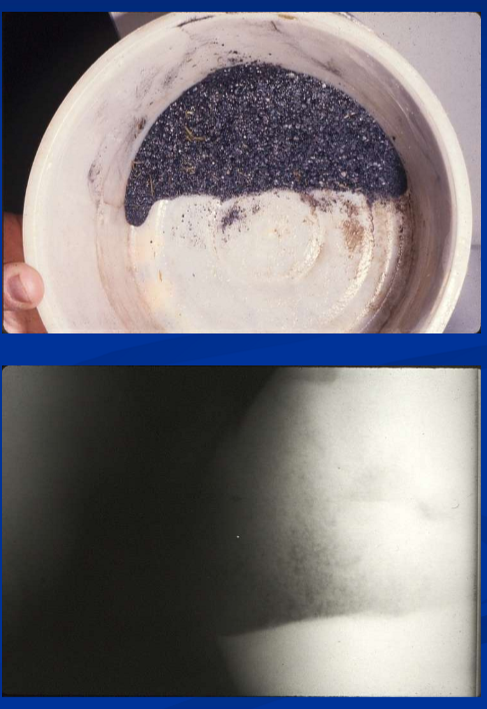

sand accumulation

sandy environments, bare pastures, feeding hay on the ground are predispositions to sand accumulation in LI

sand irritates the colonic mucosa

sometimes resulting in intermittent diarrhea (sand colopathy)

tends to accumulate in the RDC, resulting in

abdominal pain from tension on mesentery, large colon impaction and or obstruction of transverse colon

also predisposes to displacement, torsion / volvulus

diagnosis by

history of exposure, characteristic sounds on auscultation, detection of excessive sand in feces, abdominal ultrasound / radiography, and inadvertent enterocoentesis

medical tx: psyllium (sandrid pellet) hydromucilloid

400g/500kg in feed or via NG

protocol depends on amount of sand, clinical signs (colic or not)

IV fluids and analgesics as necessary

may require celiotomy; large sand accumulations, obstruction at transverse colon, failure of medical management; evacuation of sand via PF enterotomy

prevention: husbandry-avoid feeding on the ground; intermittent feeding of psyllium

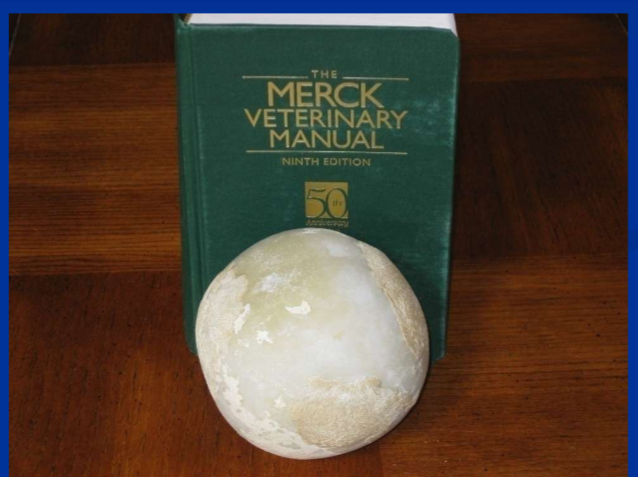

Enterolithiasis

Mg-ammonium phosphate stones in large colon

regional; CA, AZ, IN and FL

associated with alfalfa hay, high mineral and pH in colon

can be single or multiple and quite large

chronic colic and or acute abdominal crisis by wedging in transverse colon / small colon

dx with abdominal x-ray, maybe US, or exploratory sx

surgical removal required

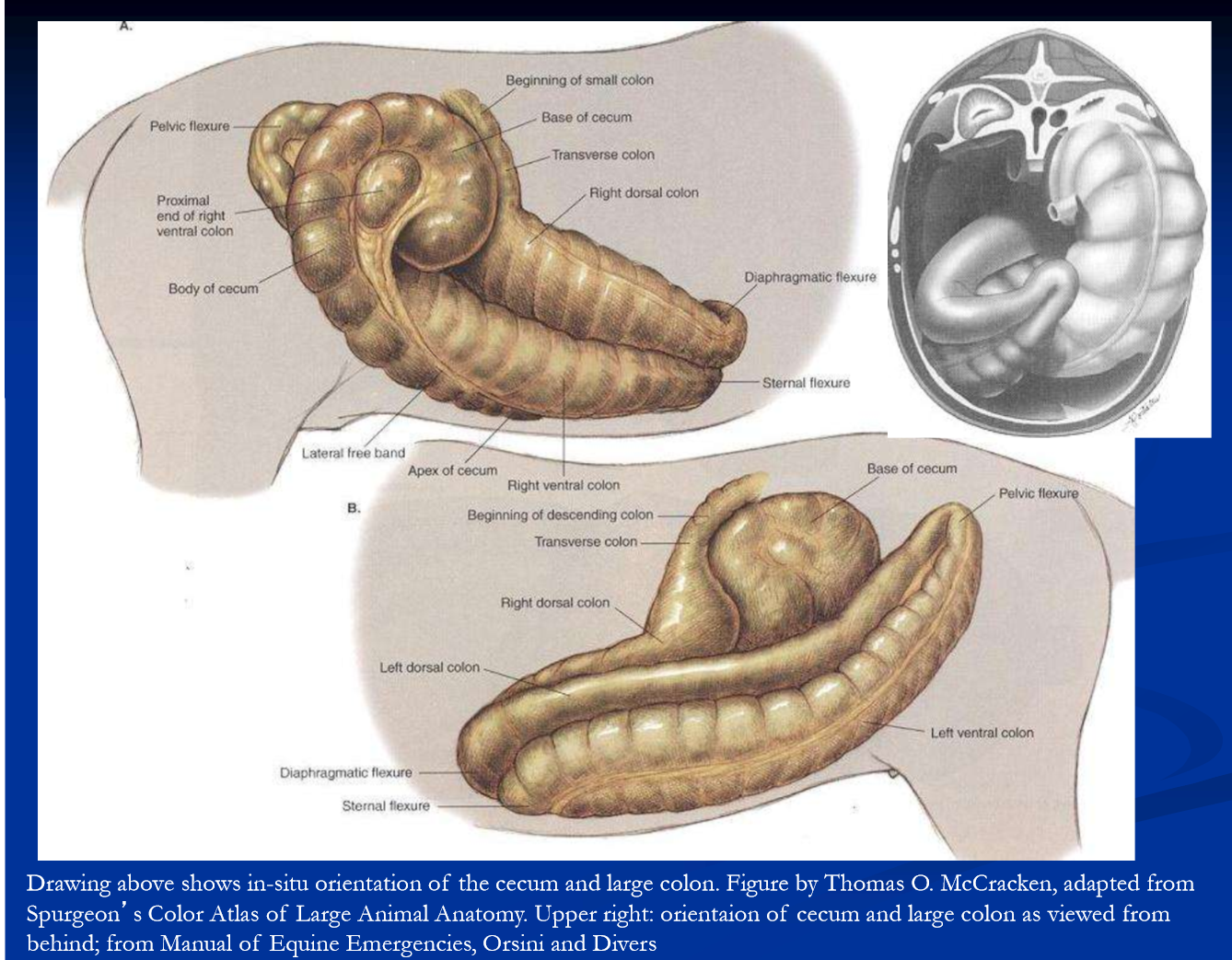

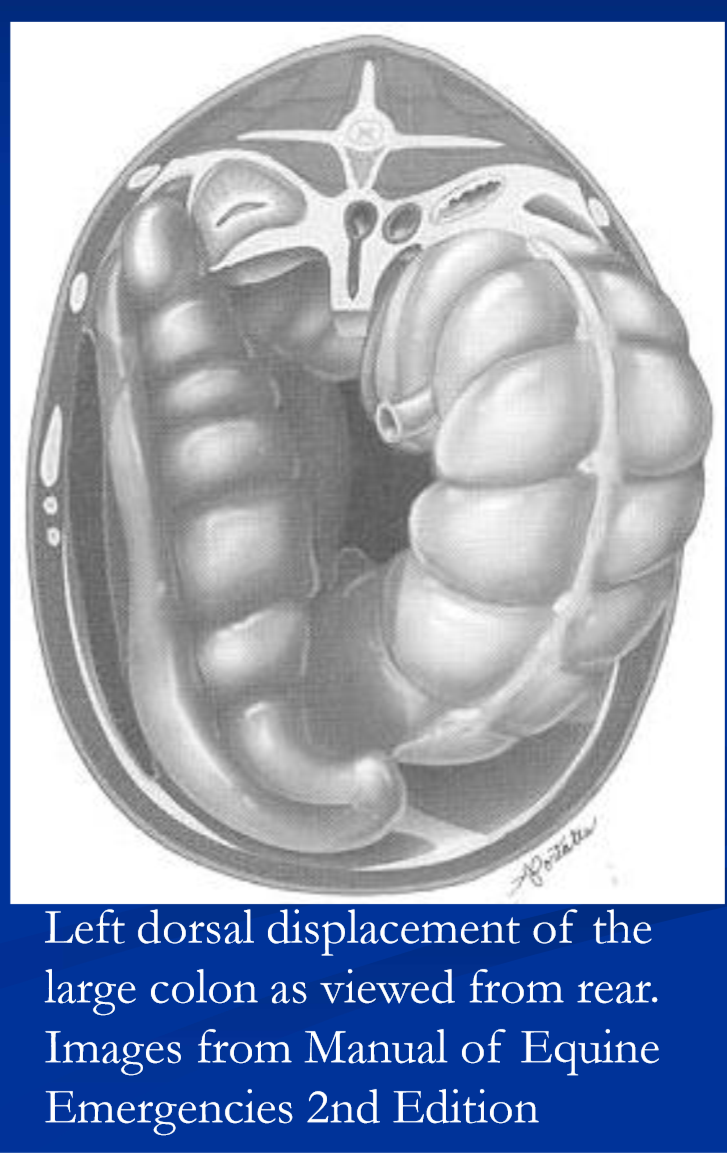

Large colon displacements, torsion, and volvulus

because most of the large colon is not directly attached to the body wall the left colon can move freely within the abdominal cavity (the floating colon)

predisposes the colon to several forms of entrapment, displacement, torsion and volvulus

primary affects adult horses; post-parturient mares particularly prone

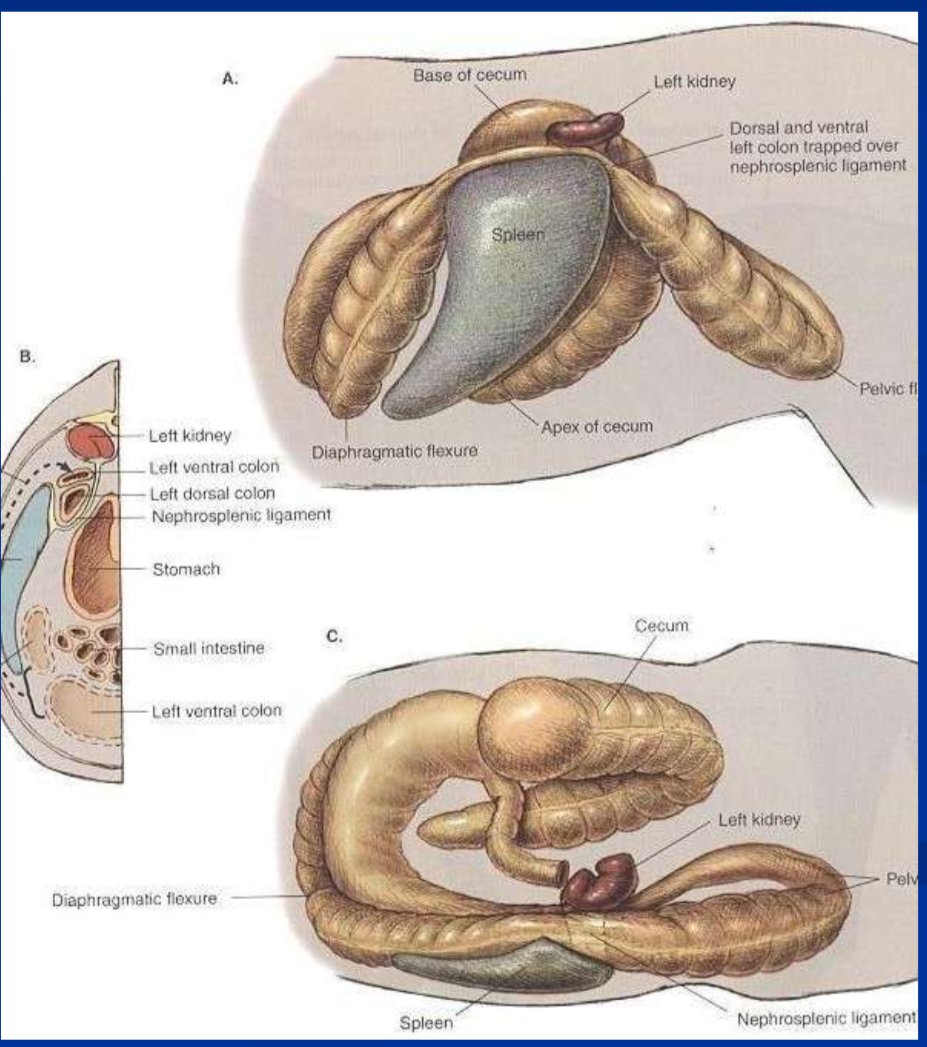

left dorsal displacement of the large colon

“nephrosplenic entrapment

non-strangulating displacement in which the left colon becomes incarcerated within the nephrosplenic space

lodged between the base of the spleen, left kidney, and neophrosplenic ligament

intermittent mild-moderate pain, depending on stage

dx by rectal exam, US

some resolve spontaneously

med txs: 1) controlled vigorous exercise 2) IV phenylpehirne or 3) anesthetize and roll

surgical correction via laparotomy often best option

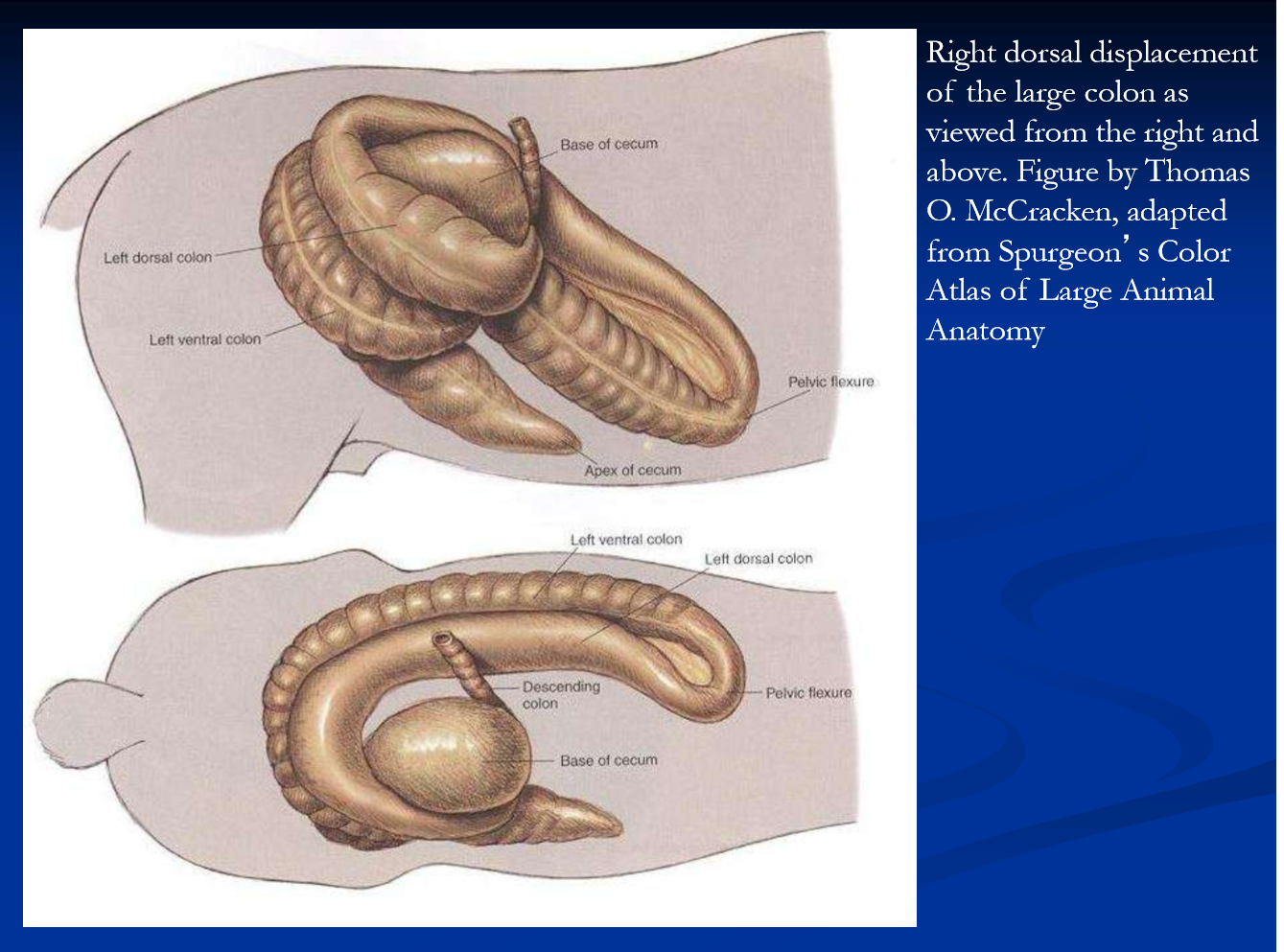

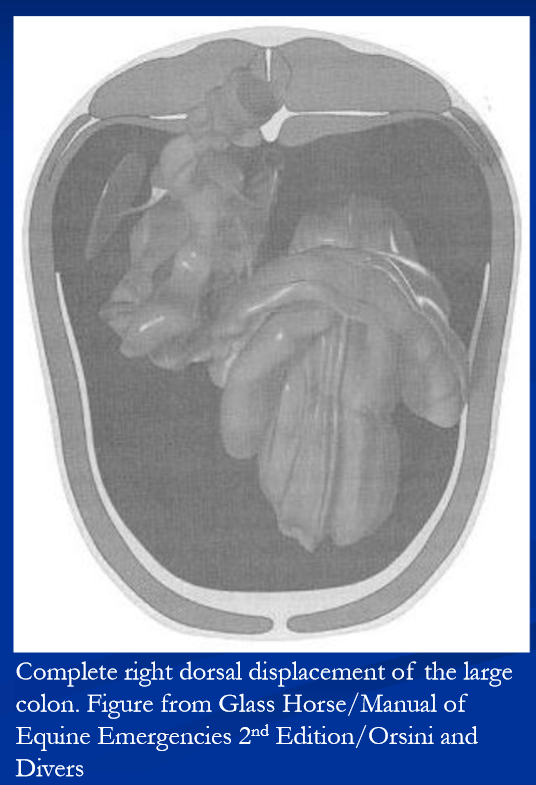

Right dorsal displacement of the large colon

the figure shows a complete right dorsal displacement of the LC

the large colon is displaced between the cecum and right body wall and wrapped around the back of the cecum, running transversally across the caudal aspect from right to left with the pelvic flexure directed forward

partial or incomplete displacements are often found at laparotomy

may possibly progress to torsion and or volvulus

a non-strangulating displacement resulting in progressive signs of pain and abdominal distention

pain varies depending on the position of the colon and degree of gas distention

over time, distention progresses, the levels of pain and cardiovascular compromise increase, and the colon is vulnerable to volvulus

dx: pain, distention, lack of fecal production, abnormal rectal exam; often the colon can be clearly felt passing across the caudal-dorsal aspect of cecum; ultrasound

surgical correction is required; generally good prognosis