Potential exam questions

1/37

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

38 Terms

Effects of trade blocs on various stakeholders which you will answer in the first lesson back after HT.

💥 VERSION 1: Consumers and Producers (classic route)

### Introduction

A trade bloc is a group of countries that agree to reduce or eliminate barriers to trade between members (e.g. EU, ASEAN, NAFTA). This can take forms such as a free trade area, customs union, or single market. The effects of trade blocs depend on the nature of integration and the competitiveness of industries.

---

### Effect 1: Consumers benefit from lower prices and greater choice

When tariffs are removed between member countries, imports from within the trade bloc become cheaper as artificial price barriers are eliminated. This leads to an increase in import competition in domestic markets, placing downward pressure on prices for consumers.

As firms face greater competition, countries are incentivised to specialise in the production of goods and services in which they have a comparative advantage. Resources are therefore reallocated towards their most efficient uses, improving allocative efficiency across the economy and increasing overall productive potential.

Furthermore, the removal of tariffs encourages increased intra-bloc trade, expanding market size for firms operating within the trade agreement. This allows firms to produce at a larger scale, benefiting from economies of scale such as spreading fixed costs over higher output. As average costs fall, firms are able to lower prices further, reinforcing the initial reduction in prices caused by increased competition.

Overall, the removal of tariffs leads to lower prices, greater efficiency, and improved consumer welfare within member countries.

Application (AO2) – add to secure top-band marks

In a large trade bloc such as the European Union, car manufacturers can sell to multiple countries tariff-free, increasing output and reducing average costs.

UK consumers importing food products from EU countries previously faced tariffs post-Brexit; removal would lower import prices and increase choice.

Firms in smaller member states gain access to larger markets, allowing them to grow beyond domestic demand constraints.

Increased competition reduces monopoly power of domestic firms, limiting their ability to raise prices.

* Diagram: tariff removal – domestic price falls from Pw+t to Pw, imports rise.

Stakeholder impact:

* Consumers gain from lower prices and wider choice.

* Firms importing raw materials benefit from cheaper inputs.

Chain of reasoning 1: Benefits depend on the extent of competition

The extent to which consumers benefit from tariff removal depends on the level of competition within the market. While increased imports should, in theory, place downward pressure on prices, this outcome is not guaranteed if firms operate in oligopolistic markets.

If a small number of large firms dominate the market, they may engage in tacit collusion, choosing to keep prices artificially high rather than competing aggressively. As a result, reductions in costs from cheaper imports or economies of scale may be retained as higher profits rather than passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices.

Consequently, the expected gains in consumer welfare and allocative efficiency may be limited, meaning the overall benefits of tariff removal are reduced when competition is weak.

Chain of reasoning 2: Short-run structural unemployment

In the short run, the removal of tariffs can lead to structural unemployment as domestic firms that are relatively inefficient face increased competition from cheaper foreign imports.

As these firms lose market share, they may be forced to downsize or exit the market entirely, leading to job losses. Workers made redundant may possess industry-specific skills that are not easily transferable to expanding sectors within the economy.

As a result, there is a time lag before labour can retrain and relocate, meaning unemployment rises in the short run. This can increase government spending on welfare benefits and reduce tax revenues, partially offsetting the long-term efficiency gains from tariff removal.

---

### Effect 2: Domestic producers benefit from larger markets and investment

When countries join a trade bloc, they create a larger integrated market with reduced or zero tariffs for member states. This makes the bloc more attractive to foreign firms seeking to gain tariff-free access to multiple countries, resulting in an increase in foreign direct investment (FDI).

For example, Toyota invested in the UK after it joined the EU, allowing the firm to access the wider EU market without tariffs.

FDI brings capital, technology, and management expertise into the host country, improving productive capacity.

With increased investment and access to a larger market, domestic producers can expand output, enabling them to exploit economies of scale. Larger production runs reduce average costs per unit, improving cost efficiency and potentially allowing firms to lower prices for consumers. Higher productivity also increases national competitiveness in global markets.

Access to a larger consumer base within the trade bloc encourages firms to invest in innovation and research & development (R&D). Firms are more willing to develop new products or improve processes when they can sell to more consumers, expecting higher returns on their investment. This drives dynamic efficiency, leading to higher-quality goods, more variety, and long-term economic growth within the member countries.

Overall, trade blocs stimulate investment, efficiency, innovation, and consumer welfare by creating larger, integrated markets and improving incentives for firms to expand and innovate.

Application (AO2)

EU: Toyota and Nissan building factories in the UK for tariff-free EU access.

ASEAN: Companies from outside Asia investing in Vietnam to export across the ASEAN market.

USMCA: Foreign car manufacturers locating plants in Mexico to benefit from tariff-free access to the US and Canadian markets.

Innovation example: Pharmaceutical firms in the EU invest heavily in R&D due to access to a large, affluent market.

Stakeholder impact:

* Domestic firms gain scale and efficiency.

* Workers benefit from higher employment and skills.

#### Evaluation:

* Inefficient firms may struggle with increased competition, leading to job losses.

FDI may be *footloose** – can relocate if bloc membership changes (e.g. post-Brexit relocations).

Benefits depend on *type of industry** – high-tech sectors benefit more than agriculture.

May cause *income inequality** if gains accrue to capital owners rather than workers.

---

### Judgement:

Overall, trade blocs tend to benefit consumers and competitive producers in the long run due to increased efficiency and lower prices. However, short-term adjustment costs and trade diversion can harm certain domestic industries and non-member countries. The magnitude depends on the bloc’s depth of integration and the country’s competitiveness.

---

# 💥 VERSION 2: Governments and Firms

### Intro

Trade blocs are forms of regional economic integration that promote trade and investment among member states through reduced trade barriers. The impact varies across stakeholders such as firms, governments, and consumers.

---

### Effect 1: Governments benefit from economic growth and employment

Increased trade boosts *aggregate demand (AD = C + I + G + (X-M))**, raising output and employment.

* Greater tax revenues from income and corporation tax as output rises.

Encourages *policy coordination** (e.g. EU environmental or labour standards).

#### Evaluation:

* If trade diversion occurs, inefficient production may rise, reducing world welfare.

Governments *lose tariff revenue** from imports within the bloc.

* Dependence on bloc trade partners can make economies vulnerable to shocks.

---

### Effect 2: Firms benefit from reduced barriers and larger markets

* Common standards and removal of non-tariff barriers reduce compliance costs.

Access to wider markets encourages *mergers and acquisitions**, innovation, and dynamic efficiency.

* Firms can source inputs more cheaply from bloc members → improved competitiveness globally.

#### Evaluation:

* Increased competition may reduce profit margins for small domestic firms.

* Large multinational firms may dominate, leading to market concentration and potential exploitation.

Long-run gains depend on how well firms *adapt and innovate**.

---

### Conclusion:

Firms and governments usually gain in the long term through higher trade volumes and productivity, but short-run adjustment costs and loss of sovereignty can reduce benefits.

---

# 💥 VERSION 3: Developed vs Developing Member Effects

### Effect 1: Developing members benefit from investment and technology transfer

* FDI flows to lower-cost members seeking production efficiency → technology diffusion, employment growth.

* Improves infrastructure and skills (e.g. Eastern Europe after EU accession).

Evaluation:

* FDI may be exploitative or concentrated in capital-intensive sectors.

* Unequal bargaining power → core-periphery dynamic within bloc.

---

### Effect 2: Developed members benefit from export expansion

* Access to emerging markets → demand for advanced goods/services rises.

* Improves trade balance and GDP growth.

Evaluation:

* May worsen income inequality if benefits accrue to high-skilled workers or firms.

* Structural shifts can harm traditional sectors.

---

# 💥 VERSION 4: Diagram-Focused (for strong analytical marks)

Use:

* Trade creation and trade diversion diagram

* Tariff removal diagram

KAA:

* Show welfare gain (consumer surplus rise) for trade creation.

* Explain loss from trade diversion if efficient non-member replaced by less efficient member.

* Discuss efficiency vs allocative outcomes.

Evaluation:

Net welfare effect depends on whether *trade creation > trade diversion**.

Depends on *size of bloc**, elasticities of demand, initial protection levels.

---

# ✅ Possible Stakeholders to Mention

* Consumers: prices, variety, welfare.

* Domestic firms: competition, economies of scale, market access.

* Workers: employment, wages, job security.

* Governments: revenue, growth, policy autonomy.

* Non-member countries: diversion, exclusion effects.

---

# ✅ Example Judgement Sentences

* “In the short run, domestic industries may contract, but in the long run, dynamic efficiency gains dominate.”

* “The net benefit of a trade bloc depends largely on whether trade creation outweighs trade diversion.”

* “Stakeholders in competitive sectors tend to gain, while those in protected or inefficient industries may lose.”

---

Would you like me to make a model 15-mark essay (exact full answer in exam style) from the best version above, hitting band 5 (A)* criteria?

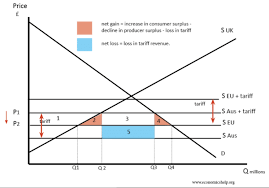

Trade bloc graph

2⃣ Before the trade bloc (with tariff)

The UK imposes a tariff on imports from both the EU and Australia.

The world price (without tariffs) from Australia is P₂ (cheapest).

But because of the tariff, imports from both countries cost P₁.

Therefore, the UK buys at P₁, and imports come from the EU (because maybe Australia faces a higher tariff or is outside the bloc).

At this point:

Domestic suppliers produce Q₁.

Domestic consumers demand Q₄.

Imports = (Q₄ – Q₁).

3⃣ After joining the trade bloc (tariff removed for EU)

Now, as part of the EU trade bloc, the UK removes the tariff on EU goods, but keeps it on Australia (non-member).

The price in the UK falls from P₁ → P₂.

Imports now come only from the EU, at P₂.

4⃣ Labelled areas (1–5)

Area | What it represents | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

1 | Loss of producer surplus | Domestic UK producers lose this area because the price falls from P₁ → P₂ and they now produce less (Q₁ → Q₂). |

2 + 4 | Gain in consumer surplus | Consumers gain from lower prices and greater consumption (price falls to P₂ and demand rises to Q₄). |

3 + 5 | Tariff revenue loss / Net welfare effect | The government used to receive tariff revenue when the price was P₁, shown by area 3 + 5. After joining the bloc, tariff revenue disappears because EU goods are tariff-free. |

3 | Net gain from trade creation | This area represents efficiency gains — imports now come from a more efficient EU producer instead of inefficient domestic production. It’s a welfare gain. |

5 | Net welfare loss from trade diversion | This area shows the loss from switching imports from a more efficient non-member (Australia, lower price) to a less efficient member (EU). It’s a welfare loss because of trade diversion. |

5⃣ Summarised interpretation

Concept | What happens | Welfare effect |

|---|---|---|

Consumer surplus | Increases by (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5) | ✅ Gain |

Producer surplus | Falls by 1 | ❌ Loss |

Government revenue | Falls by (3 + 5) | ❌ Loss |

Net welfare effect | (3 – 5) | ✅ if trade creation (3) > ❌ trade diversion (5) |

6⃣ In words:

The UK gains from cheaper imports from the EU (trade creation) — area 3.

But it loses because imports are diverted away from a more efficient supplier (Australia) — area 5.

The net welfare effect depends on whether area 3 > area 5.

✅ Key terms recap:

Trade creation: When joining a trade bloc causes imports to shift from high-cost domestic production → lower-cost member production (efficiency gain).

Trade diversion: When imports shift from a lower-cost non-member → higher-cost member (efficiency loss).

Analyse the main causes of globalisation.

Introduction

Globalisation refers to the increasing integration and interdependence of economies worldwide, through the growing flows of goods, services, capital, labour, and ideas across borders. Over recent decades, globalisation has accelerated due to a combination of technological, political, and economic factors that have reduced the barriers to international interaction. This essay will analyse the main causes — focusing on technological advancement and trade liberalisation — and will evaluate the extent to which each has been crucial in driving globalisation.

(AO1 = clear definition, AO2 = application, AO3 = line of argument)

Paragraph 1 — containerism

Containerisation has been a major driver of globalisation by revolutionising the way goods are transported internationally. Standardised shipping containers drastically reduce the time, cost, and risk associated with moving products by sea. Lower transport costs allow firms to source inputs from multiple countries, establishing global supply chains and maximising cost efficiency.

Lower shipping costs → cheaper imports and exports

By reducing the per-unit cost of transport, containerisation allows firms to import raw materials and intermediate goods at lower prices.

Example: Clothing brands like H&M import fabrics from Asia and assemble garments in low-cost countries, selling globally at competitive prices.

Reduction in logistical complexity → expansion of global supply chains

Containers simplify handling, reduce damage and theft, and enable standardisation of ports and logistics systems.

This makes it feasible for firms to fragment production across borders, exploiting the comparative advantage of different countries.

Example: Apple sources chips from Taiwan, assembles iPhones in China, and sells worldwide—logistics are possible because containers standardise and secure transport.

Economies of scale in shipping → further cost reductions

Containerisation allows the use of mega-ships that carry thousands of containers, lowering average transport costs per unit.

Lower shipping costs can be reinvested into production or passed on to consumers as lower prices, encouraging higher international trade volumes.

Application: The rise of ultra-large container vessels in ports like Rotterdam and Singapore has increased the volume of goods moved globally.

Faster and more reliable transport → market expansion

Reduced shipping times make it viable to trade perishable goods or high-value electronics globally.

This allows firms to enter new international markets and respond to consumer demand efficiently.

Example: European supermarkets import fresh fruit year-round from South America due to reliable container shipping.

Lower risk → increased foreign direct investment (FDI)

Safer, more predictable shipping reduces risk for multinational firms investing in production abroad.

FDI rises as companies confidently set up production in countries where labour or resources are cheaper, boosting global economic integration.

Example: Toyota invested in the UK to access the EU market, knowing containerised transport could reliably move cars and parts.

Stimulates global supply chain innovation → dynamic efficiency

Firms invest in better inventory management, just-in-time production, and advanced tracking systems because containerisation ensures predictable delivery schedules.

This promotes productivity gains, cost efficiency, and innovation, which further embeds globalisation into production networks.

Example: Amazon’s global logistics network relies heavily on containerised shipping to enable rapid delivery and global expansion of e-commerce.

Eval:

Evaluation / Limitations of containerisation as a driver of globalisation

Uneven benefits across countries

While containerisation benefits countries with major ports and strong infrastructure, landlocked or poorly connected countries may gain little, limiting globalisation’s reach.

Example: Many African nations rely on overland transport and see higher costs, so containerisation mainly boosts trade for countries like China, Germany, or the Netherlands.

Environmental costs

Increased container shipping contributes to CO₂ emissions, marine pollution, and congestion in ports.

Environmental regulations or carbon taxes could increase transport costs, partially offsetting the cost reductions containerisation offers.

Dependency on global supply chains

Firms become highly dependent on long-distance transport, which can be disrupted by strikes, pandemics, or geopolitical tensions.

Example: The Suez Canal blockage in 2021 delayed container ships globally, showing how over-reliance can disrupt trade flows.

Not a sufficient driver alone

Containerisation reduces costs, but other factors are also required for globalisation: free trade agreements, ICT for coordination, and FDI incentives.

Without complementary policies, the potential gains from containerisation may not materialise fully.

Diminishing returns for very small firms

Small producers may struggle to benefit from containerisation because they cannot fill containers or negotiate bulk shipping rates, limiting their ability to globalise.

Large multinationals capture most of the advantages, potentially increasing global inequality.

Short-term vs long-term effects

While containerisation lowers transport costs and boosts trade, initial infrastructure investment is very high (ports, cranes, IT systems), which may limit short-term accessibility.

2nd Chain of reasoning (digital technology):

Advances in information and communication technology (ICT), particularly the internet, have allowed for instant communication across borders.

This enables outsourcing and offshoring of services (e.g. call centres in India for UK firms).

It has also accelerated financial globalisation, as capital can move electronically across borders at near-zero cost.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ Shift of the PPF outwards for the world economy: technological progress increases productive capacity globally, allowing more trade and interdependence.

(Label axes as goods X and Y, show PPF shifting outward.)

Evaluation (limitations):

However, not all countries have benefited equally — the digital divide limits poorer nations’ ability to engage in global trade.

Furthermore, technological progress can reduce the need for physical trade in some cases (e.g. 3D printing or nearshoring), potentially slowing future globalisation.

Paragraph 2 — Trade liberalisation and policy decisions

1st Chain of reasoning (lower trade barriers):

Governments and international organisations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) have encouraged the removal of tariffs, quotas, and subsidies, promoting free trade.

For example, the creation of trade blocs like the EU or ASEAN has enhanced intra-regional trade.

Lower barriers reduce the cost of exporting and importing, encouraging multinational enterprises (MNEs) to operate globally.

2nd Chain of reasoning (FDI and deregulation):

Alongside trade liberalisation, many countries have liberalised capital markets and deregulated industries, allowing foreign direct investment (FDI).

FDI spreads technology, management expertise, and capital across borders — key features of globalisation.

For example, China’s “Open Door” policy (1978 onwards) attracted Western MNEs like Volkswagen and Apple, integrating China into the global economy.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ AD/AS model: an increase in exports and FDI shifts AD to the right, boosting growth — illustrating how openness promotes global interconnectedness.

Evaluation (limitations):

However, trade liberalisation can be reversed during protectionist periods — e.g. US tariffs on Chinese goods during the trade war.

Additionally, liberalisation may increase globalisation unevenly, benefiting capital-rich nations and multinational firms more than local producers or poorer economies.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, while multiple factors have contributed to globalisation, technological progress has arguably been the fundamental driver, as it underpins the feasibility and speed of trade, communication, and capital flows. Trade liberalisation and FDI have built upon this technological foundation, but without transport and communication innovation, the scale of integration seen today would be impossible. Nevertheless, future globalisation may depend more on policy stability and digital inclusion than on physical technology, as nations re-evaluate global supply chain risks post-COVID.

Application Summary (AO2 examples):

Apple’s global supply chain (US–China–Taiwan)

China’s Open Door Policy (1978) attracting FDI

Trade blocs: EU, ASEAN

WTO membership increases trade participation

Digital divide between Sub-Saharan Africa and OECD nations

Discuss the role of multinational corporations (MNCs) in promoting globalisation.

Introduction

A multinational corporation (MNC) is a firm that owns or controls production or services in more than one country. MNCs play a central role in driving globalisation — the process of increasing economic integration between countries — by spreading capital, technology, labour, and ideas across borders. Through investment, trade, and global value chains, MNCs have become the main mechanism by which economies become interlinked. This essay will analyse how MNCs promote globalisation through foreign direct investment (FDI) and technology and cultural diffusion, while evaluating the extent of their role relative to other drivers such as governments and technology.

(AO1 definition, AO2 context, AO3 argument preview)

Paragraph 1 — FDI and the integration of global production

1st Chain of reasoning (FDI expansion):

MNCs expand globally by investing directly in foreign countries — known as foreign direct investment (FDI).

FDI connects economies as MNCs set up subsidiaries, factories, and supply chains abroad, integrating capital and labour markets.

This leads to the creation of global value chains, where production occurs across multiple nations (e.g. design in the US, manufacturing in China, assembly in Vietnam).

For example, Apple’s global supply chain links the US, China, and Taiwan, demonstrating how MNCs physically and financially tie economies together.

2nd Chain of reasoning (Trade and specialisation):

MNCs promote international trade as they import intermediate goods and export final products, increasing cross-border flows of goods and services.

This encourages specialisation according to comparative advantage — nations produce goods where they have lower opportunity cost.

Consequently, global trade as a share of GDP has risen dramatically since the rise of MNCs in the late 20th century.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ World PPF shifting outward — MNCs’ investment and efficiency raise global productive potential and enable higher output combinations.

Evaluation:

However, the benefits may be unevenly distributed: MNCs often locate where costs are lowest, exploiting cheap labour and weak regulation.

In addition, profits are frequently repatriated to the home country, limiting the net gain for host nations.

Thus, while MNCs foster global integration, they may reinforce inequality and dependency patterns (neo-colonial argument).

Paragraph 2 — Technology transfer and cultural diffusion

1st Chain of reasoning (Technology and knowledge spillovers):

MNCs bring advanced technology and management expertise to host nations.

Local firms can learn through demonstration effects and labour mobility, raising productivity and competitiveness.

This process spreads innovation internationally — a key element of globalisation.

For example, Toyota’s operations in the UK diffused lean production methods, influencing domestic car manufacturing practices.

2nd Chain of reasoning (Cultural and consumer globalisation):

MNCs spread global brands such as McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and Netflix, standardising consumer tastes across nations.

This promotes cultural globalisation, linking societies through shared consumption patterns and media.

Global advertising and digital marketing integrate societies beyond trade and finance, strengthening cross-border interdependence.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ AD/AS model: inward FDI shifts AD (via investment spending) and LRAS (via productivity gains), illustrating how MNCs integrate economies.

Evaluation:

However, cultural globalisation can lead to homogenisation, eroding local traditions and diversity.

Moreover, technology transfer is not automatic — MNCs may keep core innovations in the parent country to maintain competitive advantage, limiting global diffusion.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, MNCs are the primary vehicle of globalisation, linking nations through FDI, trade, technology, and culture. Their operations create global supply chains and drive both economic and cultural integration. However, their influence depends heavily on government policies, technological infrastructure, and institutional quality in host countries. Without regulation and equitable policies, MNCs can entrench dependency rather than mutual integration. Therefore, while MNCs promote globalisation, they do not act alone — they function within a wider framework of liberalised trade and advancing technology that makes globalisation possible.

Application (AO2 examples)

Apple – global supply chain, technological integration

Toyota UK – technology transfer and FDI

McDonald’s / Netflix / Coca-Cola – cultural globalisation

China’s Open Door Policy (1978) – attracted MNCs, driving export-led growth

Bangladesh’s garment industry – employment through MNC contracts but with low wages

Repatriation of profits – limits benefits for host nations (e.g. Shell in Nigeria)

Evaluate the impact of globalisation on economic growth in developing countries.

Introduction

Globalisation refers to the increasing economic integration between countries through trade, capital, labour, and information flows. For developing countries, globalisation can be a key driver of economic growth—defined as the increase in real GDP over time—by expanding markets, attracting investment, and promoting efficiency. However, its impact is not uniform, as benefits can be offset by structural weaknesses, inequality, and external vulnerability. This essay will analyse how globalisation promotes growth in developing countries through trade and FDI, before evaluating limitations such as income inequality, dependence, and volatility.

Paragraph 1 — Globalisation promotes growth through trade and specialisation

1st Chain of reasoning (comparative advantage & export-led growth):

Globalisation enables developing countries to specialise in goods where they have a comparative advantage, such as labour-intensive manufacturing or primary goods.

By exporting to global markets, they achieve export-led growth, increasing aggregate demand (AD) and GDP.

For example, Vietnam has leveraged low-cost labour to become a major exporter of textiles and electronics, achieving average GDP growth above 6% annually.

Increased export earnings fund infrastructure, health, and education, fostering long-term development.

2nd Chain of reasoning (economies of scale and competition):

Open trade exposes domestic firms to international competition, encouraging efficiency and innovation.

Larger export markets allow firms to achieve economies of scale, lowering average costs and raising output.

This improves allocative and productive efficiency, stimulating long-run growth (LRAS shifts right).

Diagram:

→ AD/AS diagram — Globalisation increases AD (via exports) and LRAS (via productivity gains), leading to higher real GDP and potential growth.

Evaluation (limitations):

However, heavy reliance on a narrow export base can make developing economies vulnerable to global demand shocks (e.g., falling commodity prices).

Some may experience Dutch disease, where growth in export sectors crowds out others, stunting diversification (e.g., oil economies like Nigeria).

Paragraph 2 — Globalisation promotes growth through FDI and technology transfer

1st Chain of reasoning (FDI inflows):

MNCs establish operations in developing countries, bringing foreign direct investment (FDI) that injects capital and creates employment.

FDI can raise productivity and stimulate industrialisation — e.g., China’s Open Door Policy (1978) attracted MNCs such as Volkswagen and Apple, transforming it into a global manufacturing hub.

This increases the productive capacity of the economy, shifting LRAS rightwards.

2nd Chain of reasoning (Technology and human capital spillovers):

Globalisation spreads technology and management expertise, improving local production methods.

Workers gain skills and training, leading to higher human capital and long-term sustainable growth.

For instance, India’s IT sector developed through global outsourcing, boosting GDP and service exports.

Evaluation (limitations):

However, MNCs may repatriate profits to home countries, limiting local multiplier effects.

FDI can be concentrated in low-wage, low-value-added sectors, leading to limited technological spillovers.

Furthermore, weak governance and corruption may prevent developing nations from retaining the benefits of FDI.

Paragraph 3 (optional for 25-mark excellence) — Potential negative impacts on growth

1st Chain of reasoning (inequality and dependency):

Globalisation can widen income inequality within developing nations as skilled workers benefit more than unskilled ones.

Rising inequality can hinder long-term growth by reducing aggregate demand and limiting investment in human capital.

2nd Chain of reasoning (environmental degradation):

Increased industrial activity driven by MNCs can cause pollution and resource depletion, undermining sustainable growth.

For instance, lax environmental regulations in Bangladesh’s garment industry have caused long-term costs that reduce welfare and future growth potential.

Evaluation:

Yet, sustainable FDI and regulatory frameworks (e.g., green industrial policies) can ensure growth remains inclusive and environmentally sound.

Judgement / Conclusion

Overall, globalisation has been a powerful catalyst for economic growth in many developing economies, particularly those that have adopted export-oriented and market-friendly policies (e.g. China, Vietnam, India). However, its success depends on domestic institutions, infrastructure, and governance. Countries that fail to manage FDI, diversify exports, or invest in education often see limited benefits or even harmful dependence.

Therefore, the impact of globalisation on growth in developing countries is conditional — it promotes rapid growth when complemented by sound policy and inclusive development strategies, but can exacerbate vulnerability and inequality when mismanaged.

Application (AO2 examples)

China (1978–present) — FDI-driven manufacturing boom

Vietnam — export-led growth model

India — service-sector and IT globalisation

Bangladesh — textile exports, but low wages and poor conditions

Nigeria — oil dependence and limited diversification

Discuss the impact of globalisation on income inequality.

Introduction

Globalisation refers to the increasing interconnectedness of economies worldwide through trade, investment, migration, and technology transfer. It can affect income inequality both between countries (global inequality) and within countries (domestic inequality). While globalisation has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty, especially in emerging economies, it has also created winners and losers, contributing to widening gaps within nations. This essay will analyse both the reduction of global inequality and the widening of domestic inequality, before reaching a balanced conclusion.

(AO1 definition + AO2 context + AO3 line of argument)

Paragraph 1 — Globalisation reduces inequality between countries

1st Chain of reasoning (FDI and growth in developing economies):

Globalisation promotes foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to developing economies.

FDI brings capital, technology, and skills, increasing productivity and employment.

This drives economic growth and raises average incomes, narrowing the income gap between rich and poor nations.

For example, China’s integration into the global economy through export-led growth lifted around 800 million people out of poverty, reducing global inequality.

2nd Chain of reasoning (Access to global markets):

Developing nations can access larger export markets, specialising according to comparative advantage.

This allows them to move up the value chain, improving national income per capita.

For instance, Vietnam’s textile and electronics exports have significantly raised GDP and living standards.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ World Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) — globalisation shifts the world PPF outwards as resources are allocated more efficiently through trade and specialisation.

(Label X and Y as different goods; show outward shift of PPF.)

Evaluation (limitations):

However, the benefits may be concentrated in specific sectors or regions, leaving rural or informal workers behind.

Moreover, countries without infrastructure or human capital to attract FDI — e.g. many in Sub-Saharan Africa — may be excluded, perpetuating inequality between global regions.

Paragraph 2 — Globalisation increases inequality within countries

1st Chain of reasoning (Skilled vs unskilled wage gap):

In advanced and emerging economies, globalisation increases demand for skilled labour (to operate technology, manage MNEs) while reducing demand for low-skilled labour exposed to global competition.

This widens the wage differential between high- and low-skilled workers.

For example, in the UK and US, real wages for manufacturing workers have stagnated, while returns to education and capital have risen.

2nd Chain of reasoning (Capital mobility and profit concentration):

Globalisation allows multinational firms to locate production where costs are lowest and repatriate profits.

This boosts the income and wealth of shareholders and executives in developed nations but reduces bargaining power for domestic workers.

Consequently, income from capital rises faster than income from labour, increasing within-country inequality (Piketty’s theory).

Diagram (appropriate):

→ Lorenz curve / Gini coefficient — globalisation can make the curve more bowed (higher Gini), showing rising inequality within nations.

Evaluation (limitations):

However, government intervention (e.g. progressive taxation, education spending, minimum wage laws) can mitigate inequality.

Also, access to cheaper imported goods increases real purchasing power for low-income consumers, partially offsetting income inequality.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, globalisation’s overall impact on inequality is ambiguous and context-dependent. It has clearly narrowed global inequality by enabling the rapid growth of emerging economies such as China and India, yet it has also widened income gaps within many advanced and developing nations due to skill-biased technological change and capital mobility. The extent of inequality therefore depends on domestic policies — such as education, redistribution, and labour market regulation — which determine how the gains from globalisation are shared. Without inclusive policies, globalisation risks entrenching inequality even as it raises global prosperity.

Application Summary (AO2 examples)

China’s export-led growth → reduced poverty, narrowed global inequality

Vietnam → rapid GDP growth from trade integration

UK and US manufacturing decline → skill-based inequality

Sub-Saharan Africa → limited FDI → persistent poverty

Evaluate whether globalisation has reduced poverty in developing economies.

Introduction

Globalisation refers to the increasing economic integration between countries through trade, capital, labour, and information flows. For developing countries, globalisation can be a key driver of economic growth—defined as the increase in real GDP over time—by expanding markets, attracting investment, and promoting efficiency. However, its impact is not uniform, as benefits can be offset by structural weaknesses, inequality, and external vulnerability. This essay will analyse how globalisation promotes growth in developing countries through trade and FDI, before evaluating limitations such as income inequality, dependence, and volatility.

Paragraph 1 — Globalisation promotes growth through trade and specialisation

1st Chain of reasoning (comparative advantage & export-led growth):

Globalisation enables developing countries to specialise in goods where they have a comparative advantage, such as labour-intensive manufacturing or primary goods.

By exporting to global markets, they achieve export-led growth, increasing aggregate demand (AD) and GDP.

For example, Vietnam has leveraged low-cost labour to become a major exporter of textiles and electronics, achieving average GDP growth above 6% annually.

Increased export earnings fund infrastructure, health, and education, fostering long-term development.

2nd Chain of reasoning (economies of scale and competition):

Open trade exposes domestic firms to international competition, encouraging efficiency and innovation.

Larger export markets allow firms to achieve economies of scale, lowering average costs and raising output.

This improves allocative and productive efficiency, stimulating long-run growth (LRAS shifts right).

Diagram:

→ AD/AS diagram — Globalisation increases AD (via exports) and LRAS (via productivity gains), leading to higher real GDP and potential growth.

Evaluation (limitations):

However, heavy reliance on a narrow export base can make developing economies vulnerable to global demand shocks (e.g., falling commodity prices).

Some may experience Dutch disease, where growth in export sectors crowds out others, stunting diversification (e.g., oil economies like Nigeria).

Paragraph 2 — Globalisation promotes growth through FDI and technology transfer

1st Chain of reasoning (FDI inflows):

MNCs establish operations in developing countries, bringing foreign direct investment (FDI) that injects capital and creates employment.

FDI can raise productivity and stimulate industrialisation — e.g., China’s Open Door Policy (1978) attracted MNCs such as Volkswagen and Apple, transforming it into a global manufacturing hub.

This increases the productive capacity of the economy, shifting LRAS rightwards.

2nd Chain of reasoning (Technology and human capital spillovers):

Globalisation spreads technology and management expertise, improving local production methods.

Workers gain skills and training, leading to higher human capital and long-term sustainable growth.

For instance, India’s IT sector developed through global outsourcing, boosting GDP and service exports.

Evaluation (limitations):

However, MNCs may repatriate profits to home countries, limiting local multiplier effects.

FDI can be concentrated in low-wage, low-value-added sectors, leading to limited technological spillovers.

Furthermore, weak governance and corruption may prevent developing nations from retaining the benefits of FDI.

Paragraph 3 (optional for 25-mark excellence) — Potential negative impacts on growth

1st Chain of reasoning (inequality and dependency):

Globalisation can widen income inequality within developing nations as skilled workers benefit more than unskilled ones.

Rising inequality can hinder long-term growth by reducing aggregate demand and limiting investment in human capital.

2nd Chain of reasoning (environmental degradation):

Increased industrial activity driven by MNCs can cause pollution and resource depletion, undermining sustainable growth.

For instance, lax environmental regulations in Bangladesh’s garment industry have caused long-term costs that reduce welfare and future growth potential.

Evaluation:

Yet, sustainable FDI and regulatory frameworks (e.g., green industrial policies) can ensure growth remains inclusive and environmentally sound.

Judgement / Conclusion

Overall, globalisation has been a powerful catalyst for economic growth in many developing economies, particularly those that have adopted export-oriented and market-friendly policies (e.g. China, Vietnam, India). However, its success depends on domestic institutions, infrastructure, and governance. Countries that fail to manage FDI, diversify exports, or invest in education often see limited benefits or even harmful dependence.

Therefore, the impact of globalisation on growth in developing countries is conditional — it promotes rapid growth when complemented by sound policy and inclusive development strategies, but can exacerbate vulnerability and inequality when mismanaged.

Application (AO2 examples)

China (1978–present) — FDI-driven manufacturing boom

Vietnam — export-led growth model

India — service-sector and IT globalisation

Bangladesh — textile exports, but low wages and poor conditions

Nigeria — oil dependence and limited diversification

Sub-Saharan Africa — limited infrastructure restricts global integration

Assess the view that globalisation leads to economic convergence between countries.

Introduction

Economic convergence refers to the process by which poorer countries’ incomes grow faster than richer countries’, narrowing the gap in GDP per capita over time. Globalisation — the increasing integration of economies through trade, capital, labour, and technology flows — is often seen as a mechanism driving this convergence by spreading ideas, investment, and productivity. However, convergence is not automatic: institutional weaknesses, uneven access to technology, and global inequalities can produce divergence instead. This essay will assess the extent to which globalisation fosters convergence, using both empirical evidence and theoretical reasoning.

(AO1 = definitions; AO2 = context; AO3 = argument outline)

Paragraph 1 — Globalisation promotes convergence through trade and FDI

1st Chain of reasoning (trade and comparative advantage):

Globalisation enables developing countries to specialise in industries where they have a comparative advantage, expanding exports.

This raises income and productivity, allowing catch-up growth with developed economies.

For example, Vietnam’s export-led industrialisation (in electronics and textiles) has rapidly raised per capita income, narrowing the gap with advanced economies.

As trade integrates economies, technology and capital spread across borders, fostering convergence.

2nd Chain of reasoning (FDI and technology transfer):

Globalisation encourages FDI from multinational corporations (MNCs) seeking low-cost production locations.

This brings technology, management know-how, and skills to developing nations, boosting total factor productivity.

For instance, China’s FDI-led industrial growth post-1978 saw rapid GDP per capita growth of ~10% annually, converging towards OECD levels.

According to neoclassical growth theory, capital mobility allows poorer countries (with lower capital-to-labour ratios) to enjoy higher marginal returns, accelerating growth and convergence.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ Solow growth model diagram: show poorer country (low capital per worker) catching up to richer country’s steady-state income due to capital inflows and technology diffusion.

Evaluation:

However, convergence assumes efficient institutions and absorptive capacity.

Many developing countries lack human capital and infrastructure to absorb technology effectively.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, despite openness, growth has lagged due to weak governance, corruption, and poor infrastructure — causing divergence rather than convergence.

Paragraph 2 — Globalisation can cause divergence through unequal benefits

1st Chain of reasoning (skill-biased globalisation):

Globalisation often benefits skilled workers and capital owners more than low-skilled labour, increasing within-country inequality.

Developing nations may remain locked into low value-added production (e.g., raw materials, simple manufacturing) while rich nations dominate high-tech sectors.

This “unequal integration” slows relative income growth, reinforcing divergence.

For example, Bangladesh’s garment sector generates growth but at low wages and limited technology transfer, preventing real convergence with advanced economies.

2nd Chain of reasoning (terms of trade and dependency):

Globalisation can worsen terms of trade for primary-goods exporters as global prices fluctuate, reducing income stability.

This fosters dependency on developed economies for technology and demand, limiting self-sustaining growth.

Dependency theory argues that MNCs extract surplus from poorer countries, reinforcing divergence.

Diagram (optional alternative):

→ Lorenz curve or world income distribution: shows persistent global income gaps despite rising global trade and FDI.

Evaluation:

Nonetheless, globalisation’s impact depends on policy frameworks: countries like South Korea and Singapore used openness alongside education and industrial policy to achieve convergence.

Hence, divergence is not inevitable — it reflects how globalisation is managed, not globalisation itself.

Judgement / Conclusion

Overall, globalisation has the potential to promote economic convergence, but this depends on whether developing countries possess the institutions, education, and infrastructure to absorb technology and compete globally. Evidence suggests conditional convergence: countries that integrate effectively and implement sound policies (e.g., East Asia) converge rapidly, whereas those with structural weaknesses (e.g., many Sub-Saharan nations) diverge. Therefore, globalisation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for convergence — it provides the opportunities, but national policies determine whether those opportunities are realised.

Application (AO2 examples)

China (1978–present) — convergence via FDI and export-led growth

Vietnam — rapid GDP growth and global integration

South Korea & Singapore — policy-driven convergence with high-income nations

Bangladesh — export growth but limited technological upgrading

Sub-Saharan Africa — persistent divergence despite openness

World Bank data — global inequality between countries has narrowed, but within-country inequality has risen

To what extent does globalisation benefit producers more than consumers?

Introduction

Globalisation is the process of increasing economic integration across countries through trade, investment, technology, and labour mobility. Producers and consumers are affected differently: producers may benefit from access to larger markets and cheaper inputs, while consumers can benefit from lower prices and greater variety of goods. This essay will analyse the impacts on both groups, evaluating whether the gains are evenly distributed or whether one group benefits more. Evidence from global trade, multinational corporations (MNCs), and digital markets will be applied.

(AO1 = definition, AO2 = context, AO3 = argument outline)

Paragraph 1 — Benefits to producers

1st Chain of reasoning (larger markets and economies of scale):

Globalisation allows producers to sell goods internationally, expanding their market beyond domestic borders.

Larger markets enable economies of scale, reducing average costs and increasing profit margins.

For example, Apple sells products worldwide, maximising returns from R&D investment and lowering per-unit costs.

2nd Chain of reasoning (FDI and technology transfer):

Producers benefit from foreign direct investment (FDI), which brings capital, technology, and management expertise.

MNCs establish operations in developing countries, enhancing productivity and access to global supply chains.

Toyota in the UK improved manufacturing efficiency and domestic suppliers’ capabilities, increasing producer surplus.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ SRAS/AD or supply-demand diagram: lower production costs (shift SRAS right) increase producer surplus and output.

Evaluation:

However, global competition can also pressure domestic producers to reduce costs or close inefficient firms.

Not all producers gain equally — small firms may lack resources to compete internationally, benefiting mainly large firms.

Paragraph 2 — Benefits to consumers

1st Chain of reasoning (lower prices and variety):

Trade liberalisation and global supply chains reduce production costs, allowing firms to sell goods more cheaply.

Consumers benefit from lower prices, more choice, and higher quality products.

For example, imports of electronics and clothing from Asia have significantly reduced prices in the UK and US.

2nd Chain of reasoning (innovation and quality improvements):

Global competition encourages firms to innovate, benefiting consumers through better products and services.

Access to global digital services (e.g., Netflix, Spotify) gives consumers worldwide unprecedented content and choice.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ Supply and demand: globalisation shifts supply curve right (lower costs), increasing consumer surplus and reducing equilibrium price.

Evaluation:

However, consumers may face non-price costs, such as environmental damage or exploitation in production (e.g., fast fashion).

Some gains are concentrated in wealthier consumer groups; poorer consumers may not access certain products or services.

Paragraph 3 — Comparative assessment (extent of benefit)

Producers often capture direct financial gains through profits, economies of scale, and global expansion.

Consumers benefit indirectly through lower prices and product variety, but gains can be diffuse and spread thinly across populations.

Some studies suggest producer surplus may grow faster than consumer surplus in developing countries due to limited purchasing power and global supply chains extracting surplus.

Policy interventions (e.g., competition law, trade tariffs) can shift the balance, increasing consumer benefits or protecting domestic producers.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, globalisation benefits both producers and consumers, but the extent varies by context. Large firms and MNCs tend to capture more concentrated and tangible benefits (profits, market expansion, technology gains), while consumers benefit through lower prices and greater choice, which is more dispersed. Overall, globalisation may slightly favour producers, particularly in economies open to FDI and export-led growth, but well-functioning markets, competition, and regulatory frameworks can ensure that consumer gains are significant and sustainable.

Application (AO2 examples)

Apple and Samsung — global sales, economies of scale, profit growth

Toyota UK — FDI and productivity gains for producers

UK clothing imports from Bangladesh/China — cheaper consumer goods

Netflix, Spotify — consumer access to global content

Fast fashion — producer gains, but consumer welfare mixed with ethical concerns

Evaluate the impact of globalisation on the environment.

Introduction

Globalisation refers to the growing integration of economies worldwide through trade, capital flows, migration, and the spread of technology. This process has profound environmental implications, both positive and negative. On one hand, globalisation can increase pollution, resource depletion, and carbon emissions through higher production and transportation. On the other hand, it can promote the spread of green technology, international environmental standards, and global cooperation. This essay will analyse these impacts and assess the overall effect of globalisation on environmental sustainability.

(AO1 definition + AO2 context + AO3 line of argument)

Paragraph 1 — Negative environmental impacts

1st Chain of reasoning (increased production and resource use):

Globalisation encourages export-led growth, industrialisation, and mass production to supply global markets.

This leads to higher consumption of natural resources (water, minerals, fossil fuels) and higher levels of pollution.

For example, China’s rapid industrialisation to meet global demand increased CO₂ emissions, making it the world’s largest emitter.

2nd Chain of reasoning (transport and carbon emissions):

Increased global trade requires long-distance transport of goods via ships, planes, and trucks.

This contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

For instance, shipping 90% of global trade produces around 3% of global CO₂ emissions annually.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ Negative externality diagram: Supply curve shifts left due to environmental costs not reflected in market prices; social cost exceeds private cost, leading to overproduction and environmental degradation.

Evaluation:

However, not all globalisation-driven production harms the environment equally — some sectors are more resource-intensive than others.

Environmental damage can be mitigated by regulations, carbon pricing, or cleaner technologies.

Paragraph 2 — Positive environmental impacts

1st Chain of reasoning (technology and knowledge transfer):

Globalisation facilitates the spread of green technology and knowledge across countries.

MNCs and trade networks can introduce renewable energy technologies, efficient production processes, and environmental standards to developing countries.

For example, solar panel technology from Germany has been adopted in India and China, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

2nd Chain of reasoning (international cooperation and regulation):

Globalisation allows countries to coordinate international environmental agreements to tackle issues like climate change.

Examples include the Paris Agreement (2015) and WTO environmental standards, which are more enforceable due to economic interdependence.

This encourages firms and governments to internalise environmental costs and reduce pollution.

Diagram (optional):

→ Pigouvian tax / market correction: introducing environmental regulation shifts supply curve left to account for external costs, reducing overproduction.

Evaluation:

However, international agreements are voluntary and often unevenly enforced, so benefits can be limited.

Technology transfer often depends on profit incentives rather than environmental necessity, so adoption may be slow in poorer nations.

Paragraph 3 — Balancing positive and negative impacts

The net effect of globalisation on the environment is ambiguous.

While global trade and industrialisation can increase pollution, globalisation also spreads cleaner technologies, best practices, and awareness, potentially mitigating environmental damage.

Policy frameworks, corporate social responsibility, and consumer preferences play a key role in determining the balance.

Sustainable development depends on linking economic growth with environmental protection — globalisation can facilitate this but does not guarantee it.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, globalisation has a mixed impact on the environment. Its expansion of production, transport, and consumption has increased environmental pressures in terms of emissions, resource depletion, and pollution. However, it has also enabled international cooperation, technology transfer, and the adoption of environmental standards, which can mitigate these negative effects. The overall impact depends heavily on government policies, global agreements, and corporate practices. Therefore, globalisation can be compatible with environmental sustainability, but only if accompanied by strong regulations and incentives for green growth.

Application (AO2 examples)

China’s industrialisation → high CO₂ emissions

Global shipping industry → 3% of global emissions

Solar technology transfer → Germany to India/China

Paris Agreement 2015 → international coordination

Fast fashion industry → pollution, overconsumption, but increasing regulation (e.g., Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety)

Carbon pricing and green taxes → internalising externalities

To what extent is globalisation a force for good?

Introduction

Globalisation is the increasing integration and interdependence of economies and societies worldwide, through trade, investment, technology, and the movement of labour and information. It has the potential to deliver economic growth, poverty reduction, technological progress, and cultural exchange. However, it also poses challenges, including inequality, environmental degradation, and cultural homogenisation. This essay will analyse the extent to which globalisation is beneficial, considering its economic, social, and environmental impacts, and will evaluate the conditions under which it can be considered a force for good.

(AO1 = definition; AO2 = context; AO3 = line of argument)

Paragraph 1 — Economic benefits of globalisation

1st Chain of reasoning (trade and growth):

Globalisation enables countries to specialise according to comparative advantage and access larger markets.

Export-led growth increases GDP, employment, and income.

Example: China and Vietnam experienced rapid economic growth and poverty reduction through integration into global trade networks.

2nd Chain of reasoning (FDI and technology transfer):

Multinational corporations bring capital, skills, and technology to host countries.

Knowledge and technology spillovers improve productivity and innovation.

Example: India’s IT sector developed through outsourcing contracts from Western countries, creating jobs and raising living standards.

Diagram (optional):

→ AD/AS model: export-led growth and FDI increase AD and LRAS, raising output and income.

Evaluation:

Benefits are uneven; some countries or sectors gain more than others.

Small domestic firms may be outcompeted, and low-skilled workers in developed countries may lose out.

Paragraph 2 — Social and cultural benefits

1st Chain of reasoning (poverty reduction and living standards):

Rising economic growth allows investment in health, education, and infrastructure, improving quality of life.

Example: Global integration lifted 800 million Chinese citizens out of extreme poverty since 1980.

2nd Chain of reasoning (cultural exchange and connectivity):

Globalisation promotes cultural exchange, knowledge sharing, and international collaboration.

Example: global access to information, digital services, and entertainment such as Netflix and online education.

Evaluation:

However, globalisation can homogenise cultures, eroding local traditions.

Benefits may be concentrated among urban populations, leaving rural or marginalised groups behind.

Paragraph 3 — Environmental and ethical concerns

1st Chain of reasoning (environmental costs):

Increased production, transportation, and consumption raise carbon emissions, resource depletion, and pollution.

Example: China’s industrialisation and global shipping contribute to high CO₂ emissions.

2nd Chain of reasoning (inequality and exploitation):

Globalisation can increase inequality within and between countries.

Labour exploitation in low-cost manufacturing sectors, e.g., Bangladesh garment factories, highlights ethical concerns.

Diagram (optional):

→ Negative externality: social costs exceed private costs, showing environmental and social harm.

Evaluation:

Yet globalisation also spreads green technologies, global environmental standards, and CSR practices, mitigating harm.

Example: adoption of solar technology and international climate agreements.

Judgement / Conclusion

Globalisation can be considered a force for good, but its benefits are conditional. Economically, it drives growth, innovation, and poverty reduction; socially, it fosters knowledge sharing and global connectivity. However, without strong institutions, regulation, and policy frameworks, globalisation can exacerbate inequality, environmental degradation, and cultural homogenisation. Overall, globalisation is potentially beneficial, but its “goodness” depends on how it is managed, regulated, and distributed.

Application (AO2 examples)

China and Vietnam — export-led growth, poverty reduction

India IT sector — technology transfer and employment

Bangladesh garment industry — economic growth but ethical concerns

Netflix, Spotify — global access to digital content

Global environmental agreements — Paris Agreement, solar technology adoption

Multinational corporations — FDI and knowledge transfer

Analyse how comparative advantage leads to gains from trade.

Introduction

Comparative advantage occurs when a country can produce a good or service at a lower opportunity cost than another country. According to the theory of comparative advantage, even if one country is less efficient in producing all goods, it can still benefit from trade by specialising in goods where it has the lowest opportunity cost. This specialisation allows countries to produce and consume beyond their domestic production possibility frontier (PPF), creating gains from trade for all trading partners. This essay will analyse the mechanism through which comparative advantage generates trade gains, supported by diagrams and real-world examples.

(AO1 = definition, AO2 = context, AO3 = outline of argument)

Paragraph 1 — Specialisation and efficiency

1st Chain of reasoning (specialisation according to opportunity cost):

By identifying comparative advantage, countries specialise in goods they produce most efficiently relative to others, minimising opportunity costs.

Specialisation allows resources to be allocated more efficiently, raising total global output.

Example: Brazil specialises in coffee production, while the US specialises in wheat production. Each produces more efficiently than attempting self-sufficiency.

2nd Chain of reasoning (trading allows consumption beyond PPF):

Once countries specialise, they can trade surpluses for goods they produce less efficiently.

This enables both countries to consume combinations of goods beyond their own PPF, representing a gain from trade.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ PPF and gains from trade diagram:

Draw two countries’ PPFs; show production points with specialisation and trade allowing consumption beyond PPF.

Evaluation:

Gains depend on the terms of trade — if terms are too unfavourable, one country may gain very little.

Specialisation can create dependency on other countries, increasing vulnerability to external shocks.

Paragraph 2 — Dynamic gains and efficiency improvements

1st Chain of reasoning (economies of scale and lower costs):

Specialisation allows firms and countries to produce larger quantities of fewer goods, achieving economies of scale.

Lower average costs increase output efficiency and consumer welfare through lower prices.

Example: Japanese car manufacturers specialise in cars for export markets, achieving scale and lower unit costs.

2nd Chain of reasoning (technological and knowledge transfer):

International trade encourages innovation and adoption of new technologies, as countries compete and exchange goods.

Access to new technologies can improve production efficiency, creating further gains from trade over time.

Example: South Korea imported machinery and technology, improving domestic production capacity in electronics.

Diagram (optional):

→ Supply curve or LRAS shift: trade and specialisation shift LRAS outward, showing potential output gains.

Evaluation:

Comparative advantage assumes perfect mobility of factors within countries and no transport costs, which may not hold in reality.

Gains are often unevenly distributed between producers and consumers, and some sectors may lose out due to competition.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, comparative advantage generates gains from trade by allowing countries to specialise efficiently and exchange goods, increasing total global output and enabling consumption beyond domestic limits. Dynamic effects such as economies of scale and technology transfer amplify these gains. However, the benefits depend on terms of trade, infrastructure, and factor mobility, and some groups within countries may experience losses. Overall, comparative advantage provides a powerful theoretical basis for understanding the mutual benefits of trade, while recognising real-world limitations.

Application (AO2 examples)

Brazil — coffee; US — wheat

Japan — car exports achieving economies of scale

South Korea — technology transfer through trade in electronics

China — low-cost manufacturing for global markets

EU trade integration — countries specialise according to comparative advantage

Evaluate whether countries always benefit from specialising according to comparative advantage.

Introduction

Comparative advantage occurs when a country can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another. According to trade theory, specialisation in goods where a country has comparative advantage allows for efficient allocation of resources, higher total output, and the potential for gains from trade. However, whether countries always benefit from such specialisation is contested, as outcomes depend on terms of trade, factor mobility, external shocks, and distributional effects. This essay will analyse the benefits of specialisation and evaluate the circumstances under which it may not lead to net gains.

(AO1 = definition, AO2 = context, AO3 = outline of evaluation)

Paragraph 1 — Benefits of specialisation according to comparative advantage

1st Chain of reasoning (efficient resource allocation and output gains):

By specialising in goods where opportunity cost is lowest, countries use scarce resources more efficiently.

Total world output rises, and countries can trade surpluses for other goods, consuming beyond their PPF.

Example: Brazil (coffee) and US (wheat) can produce more collectively than if both attempted self-sufficiency.

2nd Chain of reasoning (economies of scale and productivity gains):

Specialisation allows firms to produce larger quantities of fewer goods, reducing average costs via economies of scale.

This increases competitiveness and can stimulate investment and innovation.

Example: Japanese car industry specialises in exports, achieving lower unit costs and higher productivity.

Diagram (appropriate):

→ PPF diagram: show production beyond PPF via specialisation and trade.

Evaluation:

Gains from specialisation depend on favourable terms of trade. If global prices are unfavourable, a country may gain very little or even lose relative to domestic production.

Assumes factor mobility: if labour or capital cannot move efficiently, some sectors may experience unemployment or underutilisation.

Paragraph 2 — Circumstances where specialisation may not benefit countries

1st Chain of reasoning (vulnerability to external shocks):

Specialisation may increase dependency on a narrow range of exports.

Price volatility in global markets (e.g., oil, commodities) can cause economic instability.

Example: Nigeria’s reliance on oil exports means fluctuations in oil prices significantly affect GDP and government revenue.

2nd Chain of reasoning (dynamic comparative advantage and structural change):

Comparative advantage may change over time as technology and global demand evolve.

Locking into low-value, primary-product specialisation can trap countries in low-income positions (dependency theory).

Example: Bangladesh’s garment industry provides employment but limits opportunities to move up the value chain.

Evaluation:

Specialisation can increase inequality, as urban export sectors gain while rural or informal sectors may stagnate.

Environmental costs may arise if countries focus on resource-intensive or polluting industries, reducing sustainable welfare.

Paragraph 3 — Mitigating factors and policy considerations

Governments can moderate risks through industrial policy, diversification, and education, ensuring that specialisation is dynamic rather than static.

Specialisation need not be total; partial specialisation allows countries to benefit from comparative advantage while reducing vulnerability.

Example: South Korea gradually shifted from textiles to electronics, evolving its comparative advantage.

Judgement / Conclusion

Countries often benefit from specialising according to comparative advantage, as it allows for efficient resource allocation, higher output, and trade gains. However, specialisation does not automatically guarantee net benefits. Gains depend on terms of trade, factor mobility, market volatility, and the ability to adapt to changing conditions. Therefore, while comparative advantage provides a strong theoretical rationale for trade, countries benefit conditionally — specialisation is advantageous when paired with diversification strategies, investment in human capital, and effective economic policies.

Application (AO2 examples)

Brazil and US — traditional example of comparative advantage in coffee and wheat

Japan — automotive export specialisation, economies of scale

Nigeria — dependence on oil exposes vulnerability to external shocks

Bangladesh — garment exports, low-value specialisation

South Korea — dynamic specialisation moving up the value chain

Discuss the impact of changing terms of trade on a country’s economy.

Introduction

Terms of trade (TOT) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices. A rise in TOT (export prices increase relative to import prices) allows a country to buy more imports for a given quantity of exports, while a fall in TOT reduces purchasing power. Changes in TOT can have significant effects on a country’s national income, economic growth, inflation, and balance of payments. This essay will analyse how improvements or deterioration in TOT impact an economy, using diagrams, examples, and evaluation to assess overall effects.

(AO1 definition, AO2 context, AO3 argument outline)

Paragraph 1 — Positive impacts of improving terms of trade

1st Chain of reasoning (higher real income and consumption):

An improvement in TOT means a country can purchase more imports for the same quantity of exports, increasing real national income.

This allows higher consumption and investment, potentially raising GDP and living standards.

Example: OPEC countries in the 1970s experienced rising oil prices (TOT improvement), boosting national income and government spending.

2nd Chain of reasoning (improved current account and fiscal position):

Higher export prices relative to imports improve the trade balance, leading to a surplus in the current account.

Governments may collect higher tax revenues from export industries, funding public services and infrastructure.

Example: Australia’s mining boom in the 2000s improved TOT through high commodity prices, benefiting exports and government budgets.

Diagram:

→ Terms of trade diagram / PPF / AD-AS: improved TOT shifts AD right, raising output and income.

Evaluation:

The extent of the benefit depends on export concentration — countries reliant on a few commodities gain more, but diversification reduces vulnerability.

TOT gains may be temporary if global prices fluctuate.

Paragraph 2 — Negative impacts of deteriorating terms of trade

1st Chain of reasoning (reduced real income and welfare loss):

A fall in TOT means a country must export more goods to purchase the same quantity of imports, reducing real income.

This lowers consumption, investment, and government revenue, potentially slowing economic growth.

Example: Sub-Saharan African countries reliant on primary commodities suffered during commodity price declines in the 1980s and 2010s.

2nd Chain of reasoning (inflationary pressures and balance of payments problems):

Deteriorating TOT can increase import costs, contributing to imported inflation.

A fall in TOT may worsen the current account, causing depreciation pressure on the currency, raising import costs further.

Example: Nigeria experienced deteriorating TOT with falling oil prices in 2014–2015, leading to inflation and currency pressure.

Diagram (optional):

→ Terms of trade deterioration: real income loss can be illustrated by a downward shift of the consumption possibilities frontier.

Evaluation:

Some countries may hedge against TOT fluctuations via diversification, stabilisation funds, or flexible exchange rates.

Short-term TOT shocks may be offset if long-term growth depends on technological progress or FDI inflows.

Paragraph 3 — Distributional and structural considerations

Changes in TOT affect different sectors differently: export industries gain while import-competing sectors may face higher costs.

Commodity-dependent developing countries are more vulnerable, whereas diversified economies can absorb fluctuations.

Policy responses, such as stabilisation funds, hedging, or trade diversification, influence the net impact.

Judgement / Conclusion

In conclusion, changing terms of trade have significant implications for a country’s economy, affecting real income, consumption, investment, inflation, and the balance of payments. An improvement in TOT generally raises welfare and national income, while a deterioration reduces purchasing power and may cause inflation or current account deficits. The overall impact depends on factors such as export composition, policy responses, diversification, and global market conditions. Therefore, while TOT changes can be powerful economic forces, their net effect is conditional on country-specific structures and policies.

Application (AO2 examples)

OPEC oil price rises (1970s) — TOT improvement, higher income

Australia mining boom (2000s) — TOT improvement through commodity exports

Nigeria oil price fall (2014–2015) — TOT deterioration, inflation, currency pressure

Sub-Saharan Africa commodity dependency — TOT deterioration impacts

Policy examples — sovereign wealth funds, export diversification, hedging strategies

Evaluate the economic effects of trade liberalisation.

Introduction

Trade liberalisation refers to the removal or reduction of barriers to trade, such as tariffs, quotas, and subsidies, allowing goods, services, and capital to flow more freely between countries. It aims to increase economic efficiency, expand markets, and stimulate growth. While it can benefit consumers and producers, it also has distributional and structural impacts that may disadvantage certain sectors or countries. This essay will analyse both the positive and negative economic effects of trade liberalisation and evaluate the overall impact.

(AO1 = definition, AO2 = context, AO3 = outline of argument)

Paragraph 1 — Positive economic effects