Midterm Baroque

1/190

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

191 Terms

Protestant Reformation, iconoclasm

The Protestant Reformation was a religious movement in the 16th century that rejected certain practices of the Catholic Church, leading to the emergence of various Protestant denominations. Iconoclasm during this period involved the destruction of religious images and icons, reflecting a belief that such items were contrary to true worship. (Netherlands-iconclasts)

Counter Reformation (Catholic Reformation)

A movement within the Catholic Church initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation aimed at reforming church practices, reaffirming core doctrines, and combating the spread of Protestantism through the establishment of the Jesuits and the Council of Trent.

Clarity of subject

Accuracy of narrative

stimulation to piety

Council of Trent

A pivotal ecumenical council of the Catholic Church held from 1545 to 1563 that addressed issues of church reform, reaffirmed Catholic doctrine in opposition to Protestant beliefs, and established key practices to guide the faith.

Gabriele Paleotti, Discourse on Images, 1582: docere, delectare, movere

A significant text by Gabriele Paleotti that discusses the role of religious images in art, emphasizing their purposes to teach (docere), delight (delectare), and move the viewer emotionally (movere) towards faith.

Mannerism

An artistic style that emerged in the late Renaissance, characterized by elongated forms, exaggerated poses, and a complex composition. Mannerism often expresses tension and instability, diverging from the balanced and harmonious ideals of earlier Renaissance art. Much inspired by Michelangelo in paintings and sculpture

complex

esoteric

erudite

Academia degli Incamminati, 1582

An art academy established in Bologna, focused on the study and practice of art, promoting a return to the principles of classical art and a systematic approach to painting. It aimed to refine the skill of artists and elevate the status of painting as a profession.

Agostino (on appropriation) from Raphael a feminine grace of line, from Michelangelo a muscular force from Titian strong colors and from Correggio gentle colors

Study of Reclining Boy

Annibale Carracci

ca. 1580

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque (Italy, late 16th century)

Original Location: Likely a preparatory study for a larger fresco or painting, possibly for a church, palace, or academic training

Current Location: Various collections (exact location uncertain, possibly in a museum or private collection)

Patron: No specific patron; likely part of Carracci’s studies for future commissions

Material/Media/Medium: Red chalk on paper

Technique: Naturalistic rendering using careful contour drawing and shading to create volume and depth

CONTENT (What can you see?)

A young boy is reclining, his body twisted slightly as he rests.

The pose is relaxed but detailed, with attention to anatomy, musculature, and proportions.

The boy’s limbs are positioned naturally, reflecting movement and weight.

The study is unfinished in some areas, suggesting it was an exercise in capturing the human form.

FORM (Finer details, Elements of Art & Principles of Design)

Line: Soft, precise lines define the form with fluidity and confidence.

Shape & Proportion: The body is carefully rendered with naturalistic proportions.

Value (Light & Shadow): Shading with red chalk creates depth and volume.

Composition: Balanced with an emphasis on anatomical accuracy.

Texture: The chalk medium allows for smooth transitions between light and shadow, creating a lifelike quality.

CONTEXT (Why was this piece created?)

During the late 16th century, the Carracci family was pioneering a shift away from the artificial mannerism of the time, favoring more naturalistic representations.

Italy was experiencing a religious transformation due to the Counter-Reformation, leading to a greater emphasis on clarity and realism in art.

Carracci was training artists in the Accademia degli Incamminati (Academy of the Progressives), where life studies were crucial for artistic development.

FUNCTION (Purpose of the artwork?)

Likely a preparatory study for a larger painting or fresco.

Served as a training exercise to refine Carracci’s ability to depict the human figure naturally.

Possibly used as a teaching aid for students at the Accademia degli Incamminati.

STYLE (Why does this fit into a particular movement or artist's style?)

Characteristic of Carracci’s emphasis on naturalism, rejecting the exaggerated poses of Mannerism.

The use of red chalk aligns with Renaissance and Baroque academic drawing practices.

The dynamic, lifelike pose suggests a shift towards the Baroque style’s focus on movement and emotional depth.

MEANING (What does this artwork represent?)

Reflects the growing interest in human anatomy and realism during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Represents the transition in art from the idealized, stylized figures of Mannerism to the more grounded and naturalistic depictions of the Baroque.

Demonstrates Carracci’s belief in direct observation as a means of achieving artistic excellence.

Butcher’s Shop

Annibale Carracci

ca. 1580

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque (Italy, late 16th century)

Original Location: Likely created for a domestic or tavern setting, possibly commissioned by a wealthy patron interested in genre scenes.

Current Location: Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford (one version) / Kimbell Art Museum, Texas (another version).

Patron: Uncertain, but possibly commissioned by a merchant or noble interested in contemporary life scenes.

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Bold, expressive brushwork with strong use of chiaroscuro (light and shadow) to enhance realism.

CONTENT (What can you see?)

A detailed and lively depiction of a butcher’s shop filled with meat, workers, and customers.

Several figures are actively engaged in butchering, preparing, and selling meat.

Realistic, sometimes grim details of hanging carcasses, slabs of meat, and butchered animals.

Some figures appear to be portraits, possibly of the Carracci family or local workers.

FORM (Finer details, Elements of Art & Principles of Design)

Line: Strong, dynamic lines lead the viewer’s eye through the composition.

Shape & Proportion: Figures are realistically proportioned, with a focus on anatomical accuracy.

Color: Earthy tones dominate, creating a naturalistic, unidealized representation of daily life.

Value (Light & Shadow): Dramatic contrasts between light and dark add depth and focus to the composition.

Composition: Arranged to capture movement and realism, with overlapping forms creating depth.

Texture: Thick, expressive brushstrokes enhance the rough, tactile nature of the scene.

CONTEXT (Why was this piece created?)

Part of the rise of genre painting, which depicted everyday life rather than religious or mythological subjects.

Created during the Counter-Reformation, a time when art was shifting towards more relatable, human-centered themes.

The Carracci family sought to revive naturalism in art, moving away from the exaggerated Mannerist style.

Could also be a subtle social commentary on class, labor, and the contrast between wealth and manual labor.

FUNCTION (Purpose of the artwork?)

Possibly a decorative piece for a wealthy patron who appreciated scenes of daily life.

May have served as a study of realism, challenging artistic conventions by elevating an ordinary scene into high art.

Could reflect a broader humanist interest in everyday activities and working-class figures.

STYLE (Why does this fit into a particular movement or artist's style?)

Fits within Carracci’s movement towards naturalism, which laid the groundwork for the Baroque period.

Breaks from the idealized, mannered style of the late Renaissance, instead focusing on realism and ordinary people.

Anticipates the Caravaggesque use of stark light contrasts and intense realism.

MEANING (What does this artwork represent?)

Highlights the everyday realities of labor and commerce, a theme rarely depicted in high art at the time.

Could reflect changing attitudes towards work and social class, emphasizing dignity in manual labor.

May serve as a commentary on excess and consumption, contrasting wealth and hardship.

Demonstrates Carracci’s belief that even the most mundane scenes could be elevated through artistic mastery.

Genre scene

A type of painting representing everyday life and ordinary activities, often depicting common people and their environments, developed prominently during the Baroque period.

Crucifixion

Annibale Carracci

ca. 1583

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque (Italy, late 16th century)

Original Location: Likely intended for a church altar

Current Location: Santa Maria della Carità, Bologna

Patron: Commissioned for religious devotion, possibly by a church or religious order

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Rich color palette, chiaroscuro, and dramatic composition to enhance emotional impact

CONTENT (What can you see?)

Christ crucified on the cross, surrounded by mourners and possibly angels.

Expressive faces and gestures convey deep sorrow and reverence.

A dramatic sky, emphasizing the moment’s intensity.

FORM (Elements of Art & Principles of Design)

Composition: Strong vertical emphasis on Christ’s body; figures arranged to create depth.

Light & Shadow: Chiaroscuro heightens the sense of divine presence and suffering.

Color: Earthy tones with deep reds and blues enhancing the emotional gravity.

Texture: Smooth rendering of skin, contrasted with rough wooden cross.

CONTEXT (Why was this piece created?)

Part of the Counter-Reformation’s push for emotionally compelling religious imagery.

Reflects Carracci’s shift from Mannerism toward naturalism and deep human emotion.

FUNCTION (Purpose?)

Created for religious devotion and meditation.

Designed to evoke empathy and spiritual reflection in viewers.

STYLE (Why does this fit into a movement?)

Blends Renaissance idealism with early Baroque drama.

Emphasizes naturalism, strong emotion, and dynamic composition, hallmarks of Carracci’s style.

MEANING (What does this represent?)

A powerful expression of Christian sacrifice, redemption, and divine suffering.

Demonstrates Carracci’s ability to convey human emotion in religious art.

Conversion of St. Paul

Ludovico Carracci

1587-89

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque

Original Location: Likely commissioned for a church setting

Current Location: Pinacoteca di Bologna, Italy

Patron: Unknown, but likely commissioned by a religious institution

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Dramatic lighting, diagonal composition, strong sense of movement

CONTENT (What can you see?)

St. Paul falling from his horse as he experiences a divine vision.

A bright celestial light shining down, illuminating his face.

Soldiers and companions reacting in shock and confusion.

FORM (Elements of Art & Principles of Design)

Composition: Diagonal movement, creating dynamism.

Light & Shadow: Tenebrism (strong contrast between light and dark) enhances drama.

Perspective: Figures positioned at different depths create spatial realism.

Color: Rich earth tones contrast with celestial light.

CONTEXT (Why was this piece created?)

Catholic Church promoted dramatic, emotional religious art during the Counter-Reformation.

Aligns with the Carracci Academy’s emphasis on naturalism and movement.

FUNCTION (Purpose?)

Designed to inspire faith and awe in viewers.

Used as an altarpiece to engage worshippers with the dramatic story of Paul’s conversion.

STYLE (Why does this fit into a movement?)

Early Baroque elements with dramatic movement, emotion, and chiaroscuro.

Demonstrates Ludovico Carracci’s more expressive, theatrical approach to religious scenes.

MEANING (What does this represent?)

Symbolizes spiritual transformation and divine intervention.

Highlights the power of faith to change lives.

Pietà with Virgin and Saints

Annibale Carracci

1585

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque

Original Location: Commissioned for religious devotion, likely for a church.

Current Location: Capodimonte Museum, Naples

Patron: Possibly commissioned by a church or private donor for an altar.

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Soft modeling of figures, delicate use of light, and emotional depth

CONTENT (What can you see?)

The Virgin Mary mourning over Christ’s lifeless body.

Surrounding saints displaying grief and reverence.

A sorrowful yet composed atmosphere, with figures deeply immersed in contemplation.

FORM (Elements of Art & Principles of Design)

Composition: Triangular arrangement creates stability and harmony.

Light & Shadow: Subtle chiaroscuro to enhance form and emotion.

Color: Muted palette with soft blues and earth tones emphasizing grief.

Texture: Smooth blending of tones for a realistic, yet softened effect.

CONTEXT (Why was this piece created?)

Created during the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation, which emphasized religious art that evoked emotion and devotion.

Reflects Carracci’s move toward a more naturalistic, emotionally engaging style.

FUNCTION (Purpose?)

Made for religious reflection, likely as an altarpiece.

Designed to inspire empathy and spiritual contemplation.

STYLE (Why does this fit into a movement?)

Blends Renaissance balance with early Baroque emotion.

Less rigid than Mannerist works, showing Carracci’s commitment to realism and natural human expression.

MEANING (What does this represent?)

A meditation on grief, sacrifice, and salvation.

Represents the growing desire for religious art to be deeply personal and engaging.

altarpiece

Work of art that decorates the space above and behind the altar in a Christian church Painting, relief, and sculpture in the round have all been used in altarpieces, either alone or in combination. These artworks usually depict holy personages, saints, and biblical subjects.

eclecticism

The practice of drawing inspiration and elements rom various styles and periods, rather than adhering to a single, unified aesthetic.

sfumato

(Italian for smoked off or blurred) is a technique that creates soft, imperceptible transitions between colors and tones, often blurring edges and contours to achieve a realistic or atmospheric effect

Bargellini Madonna

Ludovico Carracci

1587

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque

Original Location: Commissioned for the Bargellini family, possibly for a church or chapel in Bologna.

Current Location: Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna

Patron: Bargellini family

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Soft, expressive brushwork with dramatic lighting

CONTENT (What can you see?)

The Virgin Mary seated with the Christ Child, surrounded by saints and angels.

A warm, intimate composition with an emphasis on emotional connection.

FORM (Elements of Art & Principles of Design)

Composition: Balanced yet dynamic, with diagonal lines adding movement.

Light & Shadow: Chiaroscuro used to create depth and highlight figures.

Color: Rich, warm tones enhance the divine atmosphere.

CONTEXT (Why was this piece created?)

Reflects Counter-Reformation ideals of accessibility and emotional engagement in religious art.

FUNCTION (Purpose?)

Created for religious devotion, intended to inspire faith and contemplation.

STYLE & MEANING

Early Baroque in its emphasis on naturalism and emotional intensity.

Highlights the Carracci family’s commitment to revitalizing religious art.

Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine

Agostino Carracci

1582

engraving after Veronese

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance

Original Location: Reproduced after Veronese’s painting, intended for broader distribution.

Current Location: Various collections (prints widely distributed).

Patron: Likely a commission to spread Veronese’s imagery.

Material/Media/Medium: Engraving

Technique: Fine linework, hatching, and cross-hatching for shading.

CONTENT

St. Catherine receiving a wedding ring from the Christ Child in a divine vision.

Figures arranged elegantly, with classical drapery and idealized forms.

FORM

Line: Precise, clean engraving lines replicate Veronese’s brushstrokes.

Composition: Symmetrical and harmonious.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Reproductions allowed Veronese’s art to reach a wider audience.

Served as a devotional image for those who could not access the original painting.

STYLE & MEANING

Demonstrates Agostino’s skill in translating painterly effects into print.

Reinforces the period’s focus on religious mysticism and divine visions

Madonna with St. Matthew

Annibale Carracci

1588

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque

Original Location: Likely commissioned for a church in Bologna.

Current Location: Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

Patron: Unknown

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Blends classical composition with naturalistic figures.

CONTENT

The Virgin Mary presenting Christ to St. Matthew.

Warm interaction between the figures, emphasizing a human connection.

FORM

Composition: Pyramid structure with rhythmic movement.

Color: Muted, harmonious tones that enhance the sacred mood.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Reflects Counter-Reformation efforts to make religious imagery more accessible.

STYLE & MEANING

Marks Annibale’s transition from Renaissance balance to Baroque drama.

Highlights the role of saints as intermediaries between humans and the divine.

Madonna degli Scalzi

Ludovico Carracci

ca.1590

Period/Movement: Late Renaissance / Early Baroque

Original Location: Church of the Scalzi, Bologna

Current Location: Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna

Patron: Religious commission

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

CONTENT

The Virgin and Christ Child surrounded by angels and saints.

Strong emotional engagement between figures.

FORM

Composition: Dramatic arrangement, with strong vertical emphasis.

Color: Rich, warm tones with deep shadows enhancing contrast.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Created to enhance devotion and spiritual contemplation.

STYLE & MEANING

Represents Ludovico’s softer, more expressive approach compared to Annibale.

Emphasizes Baroque dynamism and emotional resonance

Resurrection of Christ

Annibale Carracci

1593

Period/Movement: Early Baroque

Original Location: Commissioned for a church in Bologna.

Current Location: Louvre Museum, Paris

Patron: Religious commission

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

CONTENT

Christ triumphantly rising from the tomb, surrounded by amazed soldiers.

Dynamic movement with Christ as the focal point.

FORM

Composition: Dramatic upward movement enhances divine ascension.

Light & Shadow: Bright divine light contrasts with dark surroundings.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Counter-Reformation emphasis on victory over death and faith in Christ.

STYLE & MEANING

Annibale blends Michelangelo’s muscular figures with Baroque drama.

Symbolizes Christian hope and divine power.

Story of the Founding of Rome

Ludovico Carracci

detail of Romulus and Remus

ca.1590

Palazzo Magnani, Bologna

Period/Movement: Early Baroque

Original Location: Palazzo Magnani, Bologna

Current Location: Palazzo Magnani, Bologna

Patron: Magnani family

Material/Media/Medium: Fresco

CONTENT

Depicts the myth of Romulus and Remus, raised by the she-wolf.

Features dynamic poses and expressive figures.

FORM

Composition: Balanced yet full of movement.

Color: Earthy tones enhance realism.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Created to celebrate Bologna’s connection to Roman heritage.

STYLE & MEANING

A fusion of mythological grandeur with early Baroque naturalism.

Highlights Rome’s legendary origins and Ludovico’s storytelling ability.

Lorenzo Magnani

Known for restoring family status of senators subject reflects elevation justified by millennia of distinguished ancestry (all 3 Carracci participated)

herms

A type of sculpture typically a square pillar topped with a bust or head, often representing Hermes or Mercury and frequently featuring male genitalia. They served as protective images boundary markers, and later, decorative elements.

Hercules at the Crossroads

Annibale Carracci

1597

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Commissioned for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, Rome

Current Location: Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

Patron: Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Classical composition with strong naturalism

CONTENT

Hercules stands at a crossroads, choosing between the path of Virtue (austere, challenging) and the path of Vice (pleasure, ease).

FORM

Composition: Balanced yet dynamic, with diagonal lines adding movement.

Color: Warm tones for Vice, cooler tones for Virtue.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Reflects Neoplatonic ideals and moral allegory common in the Renaissance and Baroque.

Serves as a philosophical lesson about moral choices.

STYLE & MEANING

Blends Renaissance classicism with Baroque energy.

Influenced by Michelangelo's muscular figures.

Program

Subjects related to heroic struggle as model for young cardinal. The catholic Church’s intentional use of art as a tool to reinspire faith and counter the Protestant Reformation aiming to create dramatic and emotional works that would appeal to the senses and inspire devotion.

Classicism

A style that blends the grandeur and drama of the Baroque period with the clarity, order and principles of Classical art, emphasizing expression and dynamic movement while adhering to classical principles of symmetry, proportion, and harmony.

Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

A noted patron, commissioned Annibale Carracci to fresco the ceiling of the Palazzo Farnese’s gallery depicting The Loves of the Gods and establishing the qudro riportati technique.

Galleria of the Palazzo Farnese (Farnese Gallery)

Annibale Carracci

1597-1601

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Current Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Material/Media/Medium: Fresco

Technique: Quadratura (illusionistic ceiling painting)

CONTENT

A grand ceiling fresco celebrating love, mythology, and classical themes, inspired by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel.

Includes narrative panels framed with painted architecture.

FORM

Illusionistic perspective: Creates depth through trompe-l'œil.

Color: Vibrant, dynamic contrasts emphasizing movement.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Commissioned to glorify the Farnese family and its connection to classical antiquity.

STYLE & MEANING

Marks the birth of Baroque ceiling painting.

Inspired by Raphael and Michelangelo but with a more dynamic, theatrical composition.

Idea della Bellezza

the idea of beauty or the concept of beauty

Ovid, Metamorphoses

A collection of mythological tales about transformations, served as a rich source of inspiration for Baroque artists, who drew upon its themes of change, desire and the relationship between mortals and gods.

Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne

Annibale Carracci

1597-1601

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Current Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Material/Media/Medium: Fresco

CONTENT

Bacchus, the god of wine, leads a procession celebrating his love for Ariadne, with satyrs, nymphs, and mythological figures.

FORM

Dynamic movement in twisting figures.

Color: Rich, warm palette creating a sense of celebration.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Highlights themes of love, transformation, and divine union, fitting aristocratic tastes.

STYLE & MEANING

Inspired by ancient Roman frescoes and Titian’s Venetian colorism.

Amor Vincit Omnia

Latin phrase meaning love conquers all said Roman poet Virgil

quadro riportato

Describes a painted ceiling design that mimics the appearance of framed easel paintings hung overhead.

bacchanal

Depicts wild, drunken revelry honoring Bacchus (Roman god of wine) or Dionysus (Greek god of wine, fertility and ecstasy) often featuring revelers, satyrs and Bacchus himself in an idyllic landscape.

Jupiter and Juno

Annibale Carracci

1597-1601

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Current Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Material/Media/Medium: Fresco

CONTENT

Depicts Jupiter and Juno’s divine relationship, with Juno reproaching Jupiter.

FORM

Expressive gestures convey emotion.

Rich colors highlight divine presence.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Represents themes of power and marriage, appealing to elite patrons.

STYLE & MEANING

Merges Renaissance idealism with Baroque drama.

Hyper-classical

Something that is beyond or excessively classical, often implying a heightened or exaggerated adherence to classical standards or principles.

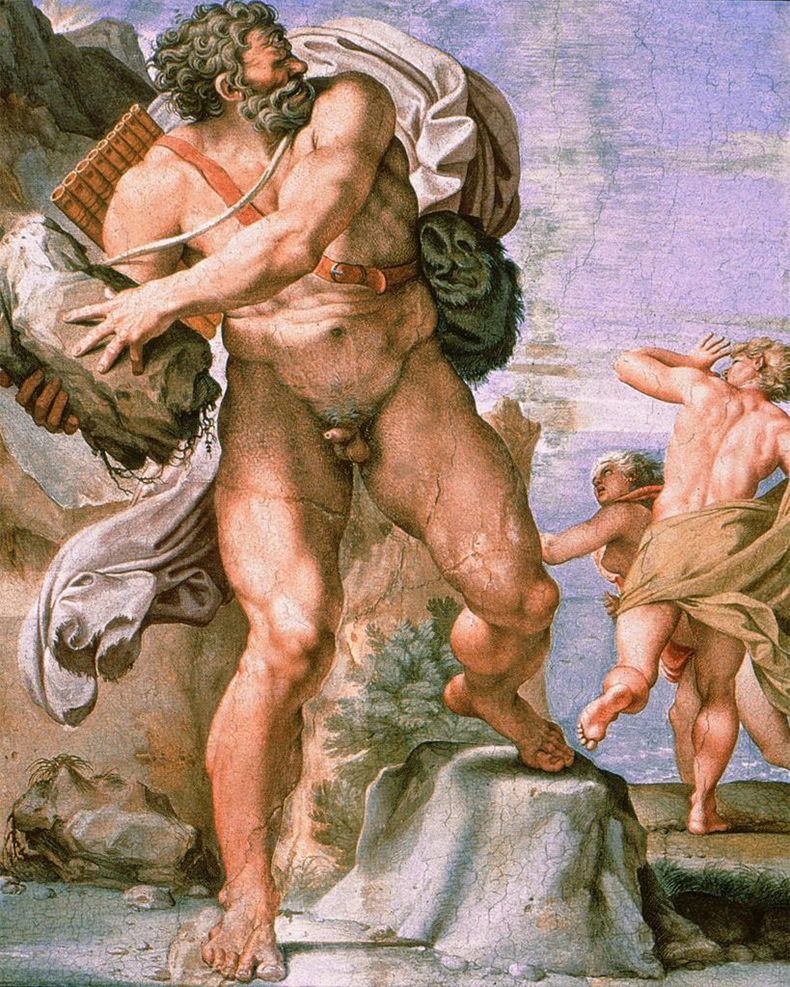

Polyphemus Innamorato

Annibale Crracci

1597-1601

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Current Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Material/Media/Medium: Fresco

CONTENT

Polyphemus Innamorato: Shows Polyphemus serenading Galatea, in a tender scene.

Polyphemus Furioso: The jealous giant hurls a rock at Acis, turning him into a river.

FORM

Innamorato is soft, dreamy, while Furioso is violent and chaotic.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Contrasts love’s gentle side and its destructive force.

STYLE & MEANING

A dramatic example of Baroque storytelling through contrast.

Homer, Odyssey

Explores the themes of homecoming identity and the human struggle against adversity and its depiction in baroque art often emphasizes the dramatic and emotional journeys of Odysseus with artist using powerful imagery and grand compositions to capture the epic’s grandeur.

Polyphemus Furioso

Annibale Carracci

1597-1601

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Current Location: Palazzo Farnese, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Material/Media/Medium: Fresco

CONTENT

Polyphemus Innamorato: Shows Polyphemus serenading Galatea, in a tender scene.

Polyphemus Furioso: The jealous giant hurls a rock at Acis, turning him into a river.

FORM

Innamorato is soft, dreamy, while Furioso is violent and chaotic.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Contrasts love’s gentle side and its destructive force.

STYLE & MEANING

A dramatic example of Baroque storytelling through contrast.

Assumption of the Virgin

Annibale Carracci

1599

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Church of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

Current Location: Same location

Patron: Religious commission

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

CONTENT

The Virgin rises to heaven, surrounded by angels and apostles below.

FORM

Upward movement leads viewer’s gaze toward divine ascension.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Reflects Counter-Reformation focus on Marian devotion.

STYLE & MEANING

Blends Raphael’s harmony with Baroque dynamism.

Tiberio Cerasi

Was an Italian patron of the arts, best known for commissioning two famous Baroque paintings for his chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome: The Crucifixion of Saint Peter by Caravaggio and The Conversion of Saint Paul by Caravaggio. He also commissioned an altarpiece, The Assumption of the Virgin, by Annibale Carracci.

Cerasi's commissions are significant in Baroque art because they embody the movement’s dramatic intensity, emotional realism, and dynamic compositions. The Baroque period (late 16th–18th centuries) was marked by theatricality, strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and a sense of movement, all of which are seen in Caravaggio’s works.

Pieta

Annibale Carracci

ca. 1599-1600

Period/Movement: Baroque

Original Location: Unknown (likely commissioned for private devotion or a church)

Current Location: Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

Patron: Unknown (possibly a religious commission)

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Highly naturalistic rendering, dramatic use of chiaroscuro

CONTENT

Depicts the Virgin Mary mourning over the lifeless body of Christ.

Christ’s body rests on a white shroud, held by Mary and an angel.

John the Evangelist and another angel stand in sorrow.

The background is dark, emphasizing the emotional weight of the scene.

FORM

Composition: Pyramid-like arrangement, drawing attention to Christ.

Color: Cool, subdued tones heighten the tragic mood.

Lighting: Strong contrasts (chiaroscuro) create depth and highlight the figures’ suffering.

Brushwork: Smooth and refined, enhancing the realism of the figures.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Created during the Counter-Reformation, a period when religious art aimed to evoke deep spiritual emotion.

The theme of Christ’s sacrifice and Mary’s sorrow was central to Catholic devotion.

STYLE & MEANING

Reflects Raphael’s influence in composition but with the dramatic emotional intensity of the Baroque.

Inspired later Baroque artists like Guido Reni and Caravaggio.

The work emphasizes human suffering and divine redemption, inviting contemplation.

Paragone

Refers to the debates and discussions about he relative merits and capabilities of different art forms, particularly painting and sculpture and to a lesser extant architecture in context to the Renaissance and Baroque art.

Classical landscape

Refers to landscapes inspired by idealized, harmonious and timeless beauty of classical antiquity.

The Flight into Egypt

Annibale Carracci

1603-04

Period/Movement: Baroque (Early Baroque Classicism)

Original Location: Commissioned for the Aldobrandini Chapel, Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome

Current Location: Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Balanced composition, atmospheric perspective, classical landscape painting

CONTENT

Depicts the Holy Family (Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus) journeying through a vast landscape as they flee King Herod’s persecution.

The figures are small, blending harmoniously with the surrounding nature.

A serene, idealized countryside stretches in the background, bathed in soft, golden light.

FORM

Composition: Carefully structured, with trees framing the scene and leading the eye toward the vanishing point.

Color: Soft, natural hues create a tranquil atmosphere.

Lighting: Gentle and diffused, enhancing the idyllic feel.

Perspective: Atmospheric perspective adds depth, making the distant landscape appear hazy.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Reflects the Baroque interest in landscapes as spiritual settings, influenced by classical ideals.

The work was meant to inspire devotion while also serving as an example of elevated landscape painting.

Part of a series of paintings for the Aldobrandini Chapel, emphasizing divine intervention and protection.

STYLE & MEANING

Marks the beginning of the idealized classical landscape tradition, influencing artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

Unlike the more dramatic, intense Baroque works, Carracci’s landscape is calm and structured, emphasizing divine harmony rather than theatrical emotion.

Highlights the connection between the divine and the natural world, a theme that would become central in Baroque landscape painting.

Contado

Refers to the rural area or countryside surrounding a city often under the city’s control

Simone Peterzano

1584-1588 Caravaggio trained under Simone Peterzano “pupil of Titian”

Basket of Fruit

Caravaggio

1597

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism)

Original Location: Unknown

Current Location: Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Patron: Cardinal Federico Borromeo

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, extreme realism, still life

CONTENT

A meticulously painted basket of fruit sits on a ledge against a neutral background.

The fruit is not idealized—some pieces show signs of decay, with withered leaves and blemishes.

Includes grapes, apples, pears, figs, and quinces, detailed with lifelike textures and imperfections.

FORM

Composition: Simple yet striking—a single focal point emphasizing the fruit.

Color: Warm, natural tones; contrast between light and shadow (chiaroscuro).

Lighting: Strong directional light from the left highlights textures.

Perspective: The basket appears slightly unstable, as if about to fall forward, engaging the viewer.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

One of the earliest independent still life paintings in Western art.

Painted during the Counter-Reformation, aligning with the Catholic Church’s emphasis on realism and moral reflection.

Possible memento mori (reminder of mortality)—the decaying fruit suggests the impermanence of life.

STYLE & MEANING

Shows Caravaggio’s signature naturalism, rejecting idealized beauty in favor of gritty realism.

An innovative take on still life, influencing later Baroque artists like Zurbarán and Velázquez.

Symbolic interpretation: Could represent Christian themes of life’s fragility, the fall of man, and redemption.

alla prima

A painting technique where wet paint is applied to wet paint often in a single sitting resulting in a direct, expressive and spontaneous style.

vanitas

A genre of art particularly still-life painting that uses symbolic objects to represent the transience of life, the futility of earthly pleasures and the inevitability of death, prompting reflection on mortality.

Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte

Collect artist and specialized in genre scenes: half-length figures with table in foreground and blank background.

Cardsharps

Caravaggio

ca. 1594

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism)

Original Location: Unknown

Current Location: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Patron: Possibly Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, dramatic realism, psychological tension

CONTENT

Depicts a young, naive nobleman engaged in a game of cards, unaware that he is being cheated.

Two dishonest cardsharps (one older and one younger) conspire against him.

The older cheat signals the younger one, who pulls out a hidden card from his belt.

The boy's elegant clothing contrasts with the rough attire of the swindlers, emphasizing social differences.

FORM

Composition: Asymmetrical and dynamic, leading the viewer’s eye through the deceitful interaction.

Color: Warm and natural tones, with subtle contrasts highlighting the figures.

Lighting: Strong chiaroscuro, creating depth and tension.

Perspective: Tight framing, drawing the viewer into the scene.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

One of Caravaggio’s early genre paintings, bringing realism and psychological drama to everyday life.

The Counter-Reformation favored moralistic themes, warning against deception and vice.

Possibly an allegory of innocence vs. corruption, showing the dangers of the world.

STYLE & MEANING

Marks Caravaggio’s break from traditional Renaissance idealism, favoring raw, emotional realism.

Influenced later Baroque artists, especially in the use of dramatic lighting and narrative storytelling.

Shows Caravaggio’s fascination with human behavior, foreshadowing his later religious works.

Bacchus

Caravaggio

1595-96

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism)

Original Location: Likely commissioned for Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte’s collection

Current Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Patron: Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, detailed naturalism, Venetian color influences

CONTENT

Depicts Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, in a sensual and humanized manner.

He is reclining on a couch, wearing a loose, draped toga, with a crown of grape leaves on his head.

Holds a shallow glass of wine, seemingly offering it to the viewer.

A bowl of ripe fruit, some decaying, sits in the foreground—perhaps an allusion to the transience of pleasure and life.

His slightly flushed cheeks and suggestive expression hint at intoxication and indulgence.

FORM

Composition: Simple, focused on Bacchus, with a strong triangular structure.

Color: Warm, natural tones; rich reds, browns, and golden hues add to the sense of physicality.

Lighting: Strong chiaroscuro creates depth, making Bacchus almost emerge from the dark background.

Perspective: The tilted wine glass and gaze directly engage the viewer, inviting participation.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Caravaggio’s work was created during the Counter-Reformation, yet Bacchus is secular, not religious—showing the influence of classical themes in elite circles.

The erotic and inviting nature of Bacchus may have been meant to entertain and provoke.

The inclusion of overripe fruit suggests the fleeting nature of youth and pleasure (a subtle memento mori).

Reflects Caravaggio’s mastery of naturalism, moving away from the traditional idealized depictions of gods.

STYLE & MEANING

Unlike classical or Renaissance depictions of Bacchus, Caravaggio presents him as a real, human figure, not an idealized deity.

His use of realism and psychological depth makes the painting feel intimate and modern.

Influences later Baroque artists, especially in the way it blends sensuality and naturalism.

castrato

A male singer who underwent castration before puberty to preserve their high, soprano or alto-like voice.

The Lute Player

Caravaggio

ca. 1596

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism)

Original Location: Commissioned for Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte’s private collection

Current Locations:

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (Version 1)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Version 2)

Badminton House, Gloucestershire (Possibly a third version)

Patron: Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, detailed naturalism, Venetian color influence

CONTENT

A young musician, dressed in fine clothing, plays a lute, looking downward in concentration.

The still life arrangement includes a violin, sheet music, and a delicate glass vase with flowers—objects that emphasize themes of music, love, and fleeting beauty.

The boy’s soft facial features and sensuous expression suggest androgyny, a common theme in Caravaggio’s early works.

Some versions of the painting include a Latin inscription on the sheet music, possibly referencing a romantic or melancholic theme.

FORM

Composition: Carefully arranged objects create a harmonious balance, guiding the viewer’s eye through the scene.

Color: Warm, natural tones; the rich fabrics and textures contrast with the delicate transparency of the glass vase.

Lighting: Caravaggio’s signature chiaroscuro creates depth, making the figure and objects emerge from the background.

Perspective: The tilted lute and violin on the table create a sense of depth and immersion, inviting the viewer into the scene.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Likely intended for elite entertainment and appreciation, as music was a central theme in aristocratic culture.

Music was associated with intellectual refinement and the pleasures of the senses, fitting Del Monte’s interests in music and science.

The fragile beauty of the flowers and musical moment may suggest the ephemeral nature of life and love (memento mori theme).

STYLE & MEANING

Caravaggio's hyper-realism and psychological depth separate this from earlier Renaissance depictions of musicians.

Venetian color influence (especially from Giorgione) is evident in the soft lighting and warm palette.

A major work demonstrating Caravaggio’s ability to blend still life, portraiture, and narrative into a single composition.

The Magdalene

Caravaggio

1596-7

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism)

Original Location: Commissioned for an unknown patron, possibly a private devotional piece

Current Location: Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome

Patron: Unknown

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, detailed naturalism, emotional realism

CONTENT

Depicts Mary Magdalene, seated on a low stool, dressed in rich yet simple clothing, with her head bowed in sorrow.

Jewelry scattered on the floor symbolizes her renunciation of her past as a courtesan.

Unlike traditional depictions, there are no extravagant religious symbols—the emphasis is on human emotion and introspection.

The background is dark and empty, drawing attention to her figure and the moment of reflection.

FORM

Composition: Simple and intimate, focusing on Magdalene’s internal transformation.

Color: Warm, earthy tones; the contrast between the golden light and deep shadows enhances realism.

Lighting: Dramatic chiaroscuro emphasizes her downcast face and emotional state.

Perspective: The slightly tilted angle of the jewelry on the floor subtly leads the viewer’s eye toward her hands and contemplative pose.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Created during the Counter-Reformation, when the Catholic Church promoted personal repentance and spiritual transformation.

Depicting Mary Magdalene as an ordinary woman, rather than an idealized saint, aligns with Caravaggio’s naturalism and emotional depth.

Encourages devotional reflection, allowing viewers to relate to her as a sinner seeking redemption.

STYLE & MEANING

Caravaggio’s innovative realism breaks away from previous idealized, decorative representations of saints.

The absence of extravagant religious symbols shifts the focus to inner spirituality rather than external grandeur.

The contrast between worldly luxury (jewelry) and spiritual contemplation reinforces themes of repentance and redemption.

A highly influential work, inspiring later Baroque depictions of saints with psychological depth and realism.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Caravaggio

1596-97

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism)

Original Location: Likely commissioned for a private patron, possibly for Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte

Current Location: Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

Patron: Possibly Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, atmospheric naturalism, Venetian-inspired color

CONTENT

The painting illustrates a quiet moment during the Holy Family’s journey to Egypt.

Mary is asleep, cradling the infant Jesus in her lap, suggesting maternal warmth and exhaustion.

Joseph is holding sheet music for an angel, who is playing the violin, creating a mood of divine harmony and rest.

A donkey stands in the background, reinforcing the idea of travel and exile.

FORM

Composition: Diagonal arrangement of figures, creating a gentle, flowing movement.

Color: Warm, earthy tones with soft natural light reminiscent of Venetian painting.

Lighting: Gentle chiaroscuro, emphasizing the divine presence of the angel while maintaining realism.

Perspective: Carefully structured to draw attention to the angel and the Holy Family, blending religious and natural elements.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Aligns with Counter-Reformation ideals, encouraging a humanized, intimate connection with sacred figures.

The inclusion of music as divine communication reflects the contemporary belief in harmony as a symbol of celestial order.

Unusual depiction of the Flight into Egypt, emphasizing rest and tenderness rather than hardship.

Possibly meant for private devotional use, promoting contemplation of faith, family, and divine guidance.

STYLE & MEANING

Breaks from traditional religious iconography, favoring a realistic, human portrayal of the Holy Family.

Soft, naturalistic figures contrast with more dramatic Baroque religious imagery.

Demonstrates Caravaggio’s early interest in light, shadow, and emotional depth, foreshadowing his later masterpieces.

Influences later Baroque depictions of religious scenes, emphasizing intimate moments over grandiose storytelling.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

Caravaggio

ca. 1598

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Likely commissioned for a private patron

Current Location: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome

Patron: Unknown

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, intense realism

CONTENT

The biblical story of Judith, a Jewish widow, decapitating the Assyrian general Holofernes to save her people.

Judith, dressed in elegant clothes, grasps Holofernes’ hair while using his own sword to cut through his neck.

Holofernes' face is contorted in pain and horror, with blood spurting from his wound.

An elderly servant, Abra, assists Judith, watching intently.

The background is dark, heightening the dramatic intensity of the moment.

FORM

Composition: Triangular arrangement of figures, focusing on Judith’s poised strength and Holofernes’ struggle.

Color: Stark contrast between Judith’s pale skin, the dark background, and the deep red of the blood.

Lighting: Dramatic tenebrism—harsh light on Judith and Holofernes against a nearly black background.

Perspective: Close-up view, making the scene intimate and shocking.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Aligns with Counter-Reformation ideals, emphasizing divine justice and heroic female virtue.

The story of Judith as a symbol of triumph over tyranny was widely used in religious and political contexts.

Highly theatrical and emotional, engaging the viewer in the violence and psychological tension.

Influences later Baroque artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, who painted multiple versions of Judith’s story.

STYLE & MEANING

Extreme realism, seen in Holofernes’ pained expression and the gory detail of the execution.

Judith’s detached yet determined gaze contrasts with traditional Renaissance depictions, which showed her as either seductive or purely virtuous.

Reflects Caravaggio’s signature style of emotional immediacy and unidealized figures, making the biblical scene shockingly real.

Establishes Caravaggio’s reputation for bold, intense storytelling, setting the stage for his later dramatic works.

Matteo Contarelli

Commissioned Caravaggio to paint three paintings for the Contarelli Chapel in the Church of San Luigi del Francesi in Rome depicting scenes from the life of Saint Matthew: The Calling of Saint Matthew, The Inspiration of Saint Matthew and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew.

The Martyrdom of St. Matthew

Caravaggio

1599-1600

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Current Location: Still in its original location, Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Matteo Contarelli

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dynamic composition

CONTENT

Depicts the moment of St. Matthew’s martyrdom, when he is attacked by a soldier inside a church.

Matthew, in white robes, is on the ground, reaching out in fear and surprise.

A ruthless executioner, partially nude, prepares to deliver the fatal blow.

Witnesses react with shock and horror, creating a sense of chaos.

An angel above extends a palm branch, symbolizing martyrdom and divine reward.

Caravaggio includes a self-portrait in the background, observing the event.

FORM

Composition: Diagonal lines create a sense of movement and urgency.

Color: Stark contrasts between light and shadow intensify the drama.

Lighting: Extreme tenebrism, highlighting Matthew and the executioner while plunging much of the scene into darkness.

Perspective: The foreshortened figures pull the viewer into the violent, emotional moment.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Commissioned as part of Caravaggio’s series for the Contarelli Chapel, celebrating St. Matthew’s life.

Reflects Counter-Reformation ideals, emphasizing martyrdom, divine grace, and human suffering.

The intense realism and dramatic energy break from Mannerist traditions, making the event feel immediate and real.

Encouraged emotional engagement and religious devotion in viewers.

STYLE & MEANING

Revolutionary use of realistic, unidealized figures in a sacred narrative.

Psychological intensity, as seen in Matthew’s desperate reach and the executioner’s determination.

Contrast between earthly violence and divine presence (angel) reinforces themes of sacrifice and salvation.

One of Caravaggio’s first major public commissions, cementing his status as a leading Baroque artist.

tenebroso

from Italian meaning dark, gloomy, mysterious, describes a style of painting characterized by extreme contrasts of light and dark where darkness dominates and a spotlight effect is used to highlight key elements.

The Calling of St. Matthew

Caravaggio

1599-1600

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Current Location: Still in its original location, Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Matteo Contarelli

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dynamic composition

CONTENT

Depicts the biblical moment when Jesus calls Matthew, a tax collector, to follow him.

Jesus, cloaked in shadow, extends his hand, pointing at Matthew, mirroring Michelangelo’s gesture in the Creation of Adam.

Matthew, seated at a table with other tax collectors, looks up in surprise and uncertainty, his hand pointing at himself as if to say, "Me?"

The figures wear contemporary clothing, making the sacred event feel immediate and real.

A strong diagonal beam of light symbolizes divine intervention.

FORM

Composition: Divides the scene into two groups—Jesus and Peter on the right, Matthew and the tax collectors on the left.

Color: Earthy tones with dramatic contrasts between light and shadow.

Lighting: Extreme tenebrism, with the light functioning as both a natural and spiritual force.

Perspective: The diagonal light leads the viewer’s eye toward Matthew, emphasizing the moment of spiritual awakening.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Part of Caravaggio’s St. Matthew cycle for the Contarelli Chapel, showcasing his innovative approach to religious art.

Reflects Counter-Reformation ideals, making biblical stories relatable and emotionally engaging.

The setting in a tavern-like environment places the sacred event within a recognizable, everyday scene, appealing to common worshippers.

Encourages viewers to see themselves in Matthew’s position, questioning their own call to faith.

STYLE & MEANING

Revolutionary use of contemporary settings and clothing in biblical scenes.

Gesture and light replace traditional iconography, making the divine subtle yet powerful.

The ambiguous identity of Matthew (is he the bearded man or the young man counting money?) encourages multiple interpretations.

A landmark painting in Baroque art, influencing later depictions of religious conversion and divine intervention.

Inspiration of St. Matthew (1st version)

Caravaggio

1602 (destroyed)

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Originally intended for the Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Current Location: Destroyed

Patron: Cardinal Matteo Contarelli

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dynamic realism

CONTENT

The painting portrayed St. Matthew being inspired by the angel to write his gospel.

St. Matthew, seated, is shown in the act of writing, with a furrowed brow, indicating concentration.

An angel is shown hovering above, holding a quill and guiding Matthew’s hand as he writes.

St. Matthew’s posture is informal, emphasizing the human aspect of divine inspiration.

The light emanates from the angel, casting shadows that highlight the intimate nature of the interaction.

FORM

Composition: St. Matthew is placed to the left, with the angel positioned above and to the right, creating a strong diagonal interaction.

Color: Subdued tones, with rich browns and soft golds focusing on the figures.

Lighting: Intense tenebrism, highlighting the figures with strong contrasts between light and shadow to evoke divine presence.

Perspective: The angel’s interaction with Matthew creates a sense of spiritual engagement, but grounded in the earthly realm through their everyday expressions and clothing.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Commissioned for the Contarelli Chapel, along with The Calling of St. Matthew and The Martyrdom of St. Matthew.

A key work in Caravaggio’s innovative approach to sacred subjects, emphasizing realism and psychological depth.

Unfortunately, this first version was destroyed, possibly due to disagreements with the patron, as it was rejected by the church.

It likely showed a more earthy, intense scene of divine inspiration, in line with Caravaggio’s typical style of depicting biblical figures in contemporary settings.

STYLE & MEANING

The rejection of this version likely reflects the church’s reluctance to embrace Caravaggio’s gritty realism, which might have been deemed too human or informal for a sacred space.

Caravaggio’s interest in psychological depth would have been evident here, portraying St. Matthew’s internal process of divine inspiration rather than a traditional, idealized depiction.

The light and shadows would have been used to symbolize divine illumination or the presence of the Holy Spirit.

The focus on the ordinary in portraying a holy figure connects to the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on personal connection to the divine.

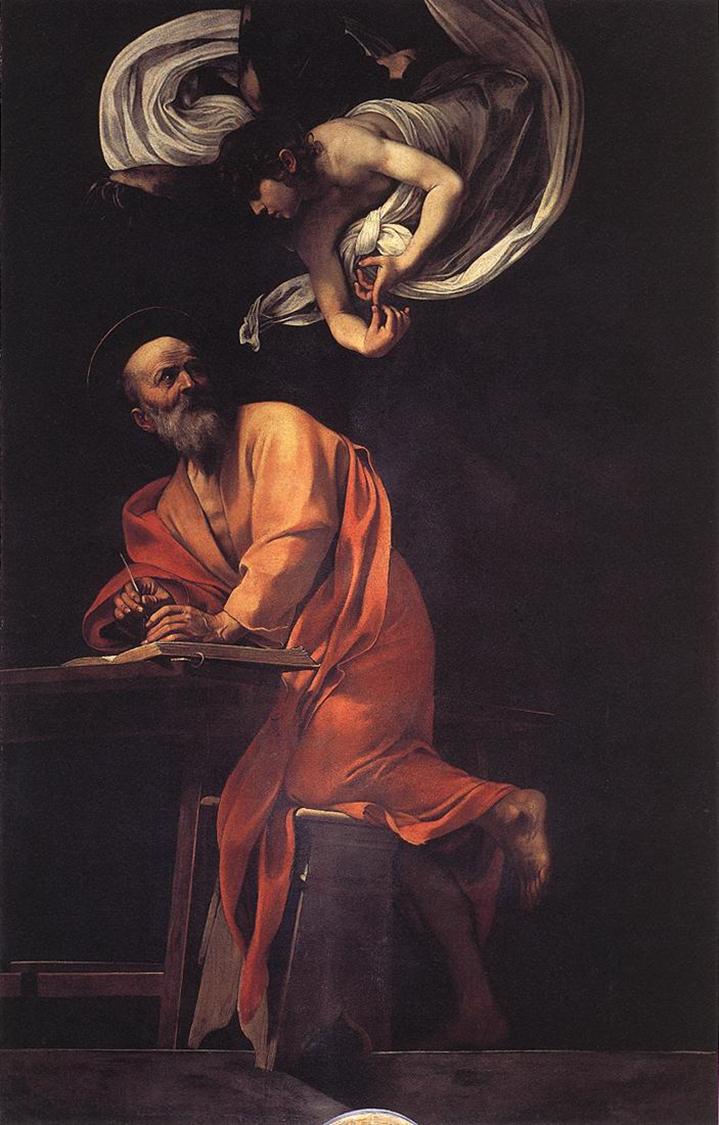

Inspiration of St. Matthew (2nd version)

Caravaggio

1602

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Current Location: Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Matteo Contarelli

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dynamic realism

CONTENT

The painting depicts St. Matthew, now in a more formal position, inspired by an angel as he writes his Gospel.

St. Matthew is seated at a desk, writing with pen and paper, and looks upward with an expression of awe and contemplation.

The angel, appearing in the upper right corner, holds a quill, inspiring St. Matthew through its divine influence.

Light from the angel illuminates Matthew, emphasizing the moment of divine revelation and inspiration.

FORM

Composition: The angel is positioned above Matthew, creating a strong diagonal line between them, emphasizing the spiritual connection.

Color: Earthy tones dominate the painting, with light accents highlighting Matthew’s face and the quill held by the angel.

Lighting: Use of tenebrism to create a sharp contrast between the illuminated figures and the surrounding darkness, reinforcing the spiritual presence of the angel.

Perspective: The figures are framed to draw the viewer’s eye toward the interaction between St. Matthew and the angel, reinforcing the moment of divine inspiration.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

This second version was created after the first version was rejected by the church. The revised version was accepted and became part of the Contarelli Chapel series.

Caravaggio’s dramatic, realistic style was controversial, as it strayed from traditional religious depictions by emphasizing the human emotions and realities of the holy figures.

The second version of the painting adheres more closely to the expectations of the Church, focusing on the sanctity of the moment rather than the more informal, gritty realism seen in the first.

STYLE & MEANING

This version is more conventional in its approach, aligning with the church’s preference for reverence in religious subjects.

The more serene and contemplative expression of St. Matthew in this version contrasts with the more earthly, emotional portrayal in the first version.

The use of light to highlight the angel’s influence underscores the idea of divine guidance, which was important in the Counter-Reformation as the Church sought to inspire a personal connection to the divine.

The transition in style between the two versions reflects Caravaggio’s ability to adapt his bold naturalism to different contexts while maintaining his emphasis on emotional depth.

decorum

The appropriate behavior, speech and conduct expected in a given situation. Latin meaning seemly or fitting.

TIberio Cerasi

An Italian nobleman and the founder of the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. Was a treasurer to Clement VIII. He became prominent in the early 16th century, serving as a papal chamberlain under Pope Gregory XIII. Cerasi is known for his patronage of the arts, commissioning works from famous artists like Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci for the chapel he established in the church, which played a significant role in the Baroque artistic movement.

Martyrdom of St. Paul

Caravaggio

1600

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

Current Location: Vatican Museums, Vatican City

Patron: Commissioned by Cardinal Tiberio Cerasi

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dynamic realism

CONTENT

Depicts the martyrdom of St. Peter, who is crucified upside down on a wooden cross.

The scene is set in a dark, chaotic environment, with St. Peter’s figure dramatically illuminated from the right, emphasizing his suffering and devotion.

Soldiers are depicted as unconcerned and brutal, reinforcing the violence of the moment.

The background is almost entirely dark, with the light focused on St. Peter, symbolizing his divine strength despite his earthly suffering.

One of the soldiers appears to grab hold of the cross, while another assists in raising it, creating a sense of imminent violence.

FORM

Composition: The composition creates a sense of movement, with diagonal lines forming from the cross and the figures’ postures, enhancing the drama of the scene.

Color: Deep, earthy tones, with dramatic highlights on St. Peter and his tormentors.

Lighting: Strong tenebrism illuminates only the figures in the foreground, creating a stark contrast between light and shadow. The use of light on St. Peter’s face emphasizes his strength and holiness in the face of martyrdom.

Perspective: The forceful diagonals create a sense of movement and urgency, drawing the viewer into the brutal scene of martyrdom.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

This painting was commissioned for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, as part of a larger series depicting the martyrdoms of St. Peter and St. Paul.

The intensity of the scene was meant to inspire devotion and reverence among the viewers, showcasing the strength of faith and ultimate sacrifice.

The use of tenebrism highlights the psychological and physical suffering of St. Peter, making it more relatable to the viewer and emphasizing the human cost of martyrdom.

This painting reflects the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on personal engagement with faith, making the sacred events feel immediate and real.

STYLE & MEANING

The dramatic realism and psychological depth Caravaggio employed marked a departure from earlier, more idealized depictions of martyrdom.

The focus on human suffering, combined with the intimate lighting, conveys the real emotional weight of the scene, making it more accessible to the viewer.

The upside-down crucifixion highlights St. Peter’s humility and his willingness to suffer for his faith, reinforcing his sanctity.

The contrast between light and dark reflects the spiritual battle between good and evil, with the divine light highlighting St. Peter’s faith even in the face of death.

The painting is a powerful expression of the sacrifice of saints, marking a significant shift in Baroque religious art by emphasizing raw emotion and realism.

The Conversion of St. Paul (1st version)

Caravaggio

1600

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Commissioned for the Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

Current Location: Destroyed

Patron: Cardinal Tiberio Cerasi

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dramatic realism

CONTENT

The scene depicts the moment of St. Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus, where Paul is struck by a divine light and falls off his horse.

St. Paul, blinded by the light, lies on the ground while his horse rears up in fear.

The light from the heavens symbolically illuminates Paul, emphasizing the divine nature of the event.

A figure (possibly a companion) appears to help Paul, drawing attention to the dramatic physicality of the moment.

The scene is depicted with intense realism, capturing the vulnerability and human emotion in the midst of divine intervention.

FORM

Composition: The action is framed with strong diagonals, as St. Paul’s body is placed at a dramatic angle on the ground, drawing the viewer’s eye to the central divine light.

Color: Rich, earthy tones dominate the scene, with vivid contrasts of light emphasizing the event’s spiritual and emotional intensity.

Lighting: Tenebrism is used to create stark contrasts between light and shadow, with the bright light representing divine intervention, and the surrounding darkness suggesting the moment of spiritual blindness and awakening.

Perspective: The strong contrast between light and dark intensifies the psychological drama, focusing attention on Paul’s physical and spiritual transformation.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

This work was part of the Cerasi Chapel cycle in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, alongside The Martyrdom of St. Peter and The Crucifixion of St. Peter.

The Conversion of St. Paul was a significant event in Christian history, and Caravaggio’s depiction focuses on the sudden and overwhelming nature of the divine experience.

The rejection of the first version of this painting led to the creation of a second version, which is now in the Odescalchi Balbi Collection, where Caravaggio adjusted his approach to better fit the church’s expectations.

STYLE & MEANING

Realism and Emotional Depth: Caravaggio emphasizes the human side of St. Paul’s conversion, with a focus on physicality and emotion, in contrast to more idealized depictions.

The strong contrasts between light and dark highlight the divine presence and suggest the inner spiritual battle Paul experiences.

The vulnerability of Paul’s figure as he lies on the ground symbolizes his spiritual awakening and humbling experience before God.

The first version of the painting was rejected, possibly because of the earthiness of the depiction, as Caravaggio’s works often elicited controversy for their bold naturalism and emphasis on raw, unvarnished emotion.

The work is significant because it represents the personal nature of religious experience in Baroque art, emphasizing the individual's encounter with the divine.

The Conversion of St. Paul

Caravaggio

1601

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome (Cerasi Chapel)

Current Location: Odescalchi-Balbi Collection, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Tiberio Cerasi

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism, dramatic realism

CONTENT

The scene depicts the moment of Saint Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus, where he is struck by a divine light, causing him to fall from his horse.

Saint Paul is shown lying on the ground, looking upward in awe, his eyes wide open but still blinded by the light.

The light from above appears almost divine and overwhelming, symbolizing the presence of God.

A companion or servant is depicted in the background, holding the reins of Paul’s horse as the animal rears in fear.

The strong physicality of the moment, with Paul’s intense fall and the chaos surrounding the horse, emphasizes the dramatic and overwhelming nature of the conversion.

FORM

Composition: The painting is framed with strong diagonals, emphasizing the dynamics of the fall and the divine light. The diagonal line created by the horse’s raised front leg leads the viewer’s eye to Paul’s figure.

Color: Caravaggio uses rich dark tones in the background, with the bright light focused on Paul, creating a stark contrast between the divine illumination and the darkness.

Lighting: Tenebrism is a key technique here, with the light from above creating a sharp contrast between Saint Paul’s illuminated face and the dark background, heightening the emotional intensity of the conversion.

Perspective: The perspective is dramatic, with the viewer's focus placed directly on Saint Paul’s vulnerable and awe-struck face, with the powerful light from above enhancing his divine encounter.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Commissioned for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo alongside The Martyrdom of St. Peter, this painting was intended to be part of a visual narrative that honored the apostles and their martyrdoms.

The work was created during the Counter-Reformation, a period where the Catholic Church emphasized a personal, emotional connection to the divine.

The dramatic realism and intense emotional focus reflect the Church’s desire to connect with the viewer’s spiritual experience and evoke strong devotional feelings.

STYLE & MEANING

Realism and Emotion: Caravaggio’s depiction of Saint Paul’s conversion is marked by raw emotional depth, emphasizing the human experience of a divine encounter.

Psychological Impact: The blinding light and physical vulnerability of Paul symbolize his moment of spiritual transformation. This realistic portrayal of the sacred event brings it closer to the viewer, making it more immediate and relatable.

Tenebrism: The use of light and dark is critical in symbolizing the spiritual transition from darkness (sin) to light (grace). The overpowering divine light contrasts sharply with the surrounding darkness, symbolizing the divine intervention in Paul’s life.

Symbolism of Humility: Saint Paul’s physical position on the ground, falling from his horse, emphasizes his humility and vulnerability, even as the light of God is reaching him, a common theme in Baroque religious art.

Historical Impact: The painting is an iconic Baroque work that combines dramatic storytelling with deep emotional resonance, marking the transition of religious art into a more personal, relatable experience for the viewer.

Supper at Emmaus

Caravaggio

1601-2

the older one on the right raising his hands in surprise.

The food on the table, including a dish of fish and bread, adds a realistic touch, grounding the divine moment in a familiar, everyday setting.

FORM

Composition: The composition is balanced, with Christ at the center, surrounded by the disciples, creating a moment of dramatic interaction. The spatial arrangement draws the viewer's attention directly to Christ’s hand and blessing.

Color: Earthy tones dominate the scene, with vivid highlights on Christ’s face and hands, creating a focal point that draws the eye. The darker background emphasizes the divine light surrounding Christ and his act of blessing.

Lighting: Caravaggio uses strong tenebrism, with light focused on Christ and the disciples, while the background remains shrouded in darkness, heightening the mystical and divine nature of the revelation.

Perspective: The low angle perspective draws the viewer into the scene, creating a sense of intimacy and immediacy. The figures are portrayed in a realistic manner, with clear attention to physical detail, which makes the miraculous event feel more immediate and relatable.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Commissioned by Cardinal Francesco del Monte for the San Luigi dei Francesi church in Rome, Supper at Emmaus was created as part of a series for the church, alongside Caravaggio’s Calling of St. Matthew and Martyrdom of St. Matthew.

The painting was created during the Counter-Reformation, a time when the Catholic Church emphasized art that engaged the viewer emotionally and brought religious themes into personal, relatable terms.

The use of realism in depicting a sacred event was part of Caravaggio’s innovative approach to religious art, creating a connection between the divine and the everyday.

STYLE & MEANING

Realism and Intimacy: Caravaggio’s use of realistic figures and everyday objects in a holy scene creates a sense of intimacy and personal engagement with the viewer, making the divine revelation feel tangible and immediate.

Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism: The dramatic light and shadow emphasize the moment of revelation, with the light on Christ’s face and hand symbolizing his divine nature. The dark background contrasts with the brightness of the central figures, symbolizing the contrast between the earthly and the divine.

Symbolism: The bread and fish represent the Eucharist, symbolizing Christ’s body and his sacrificial death, while the disciples’ surprise and recognition suggest the divine mystery of the resurrection.

Historical Significance: Caravaggio’s work is noted for its psychological realism and emotional intensity, moving away from idealized religious figures to show more relatable human reactions. This was a break from the past and aligned with the Counter-Reformation’s focus on spiritual engagement through personal and immediate experiences.

Amor vincit omnia (Love Conquers All)

Caravaggio

1602-3

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Commissioned by the Cardinal del Monte for a private collection in Rome

Current Location: Palazzo Barberini, Rome

Patron: Cardinal Francesco del Monte

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, tenebrism

CONTENT

The painting depicts Cupid (Amor), the Roman god of love, as a young, semi-nude figure holding a bow and arrows while stepping on a collection of symbolic objects that represent various forms of human achievement, including a musical instrument, military helmet, weapons, and art supplies.

Cupid’s gesture of triumph suggests that love overpowers all worldly accomplishments and forces.

Cupid’s blindfolded eyes emphasize the irrational and unpredictable nature of love that can conquer everything, regardless of reason or power.

The background is intentionally dark, emphasizing the light on Cupid, which aligns with Caravaggio’s characteristic use of tenebrism to focus attention on the subject.

FORM

Composition: The figure of Cupid is placed centrally, creating a strong sense of verticality. His stance and positioning emphasize the idea of dominance and victory over the objects beneath him.

Color: The palette is dominated by earthy tones and rich reds, with light illuminating Cupid and the objects beneath him, accentuating the contrast with the dark background.

Lighting: Caravaggio’s characteristic use of tenebrism creates a stark contrast between light and dark, highlighting the symbolic figure of Cupid and imbuing the work with a sense of divine authority.

Perspective: The perspective in the composition creates a dynamic interaction between the viewer and the objects under Cupid’s feet, symbolizing the dominance of love over all earthly pursuits.

CONTEXT & FUNCTION

Amor Vincit Omnia was commissioned for Cardinal del Monte, a patron known for his interest in the cult of love and its metaphorical power.

The painting was created at a time when Caravaggio was at the height of his fame, known for his ability to turn classical subjects into emotional, realistic depictions of human figures and allegories.

The painting is seen as a playful and provocative depiction of love’s triumph over worldly power and reason, reflecting the philosophical and intellectual currents of the time, which often engaged with classical mythology and human emotions.

It was likely intended for private enjoyment rather than a public commission, showcasing Caravaggio’s ability to infuse allegorical subjects with emotional and psychological depth.

STYLE & MEANING

Symbolism of Triumph: Cupid’s pose and symbolic objects beneath his feet suggest that love overcomes all human institutions, including power, art, and reason. This reflects the Renaissance and Baroque interest in human emotion as a dominant force.

Naturalism and Realism: Caravaggio’s depiction of Cupid as a youthful, realistic figure rather than an idealized representation emphasizes the humanity of the allegory, making it more relatable and emotionally impactful.

Psychological Depth: Cupid’s blindfold highlights the irrational nature of love, while the dark background accentuates the dramatic light on Cupid, elevating the figure to a position of divine authority.

Rejection of Conventional Ideals: By portraying a classical figure like Cupid in such a realistic, almost vulnerable manner, Caravaggio rejected the idealized, ethereal depictions of mythological subjects common at the time, instead infusing the painting with emotional intensity.

Historical Significance: The painting embodies the Baroque principles of drama, emotion, and intensity. It also plays with the theme of the unpredictable and uncontrollable nature of love, which was a recurring theme in both Renaissance and Baroque art.

Marchese Giustiniani

An influential Italian nobleman known for his extensive contributions to the arts and culture during the Renaissance period. He played a significant role in the patronage of various artists and philosophers, thus promoting the cultural enrichment of his time. The Giustiniani family was notable not only for their wealth but also for their political influence. The Marchese established several institutions and collections that advanced the appreciation of art and scholarship. His support helped artists flourish, and his legacy includes the fostering of artistic talent that contributed to the development of Baroque and Renaissance art.

Death of the Virgin

Caravaggio

ca. 1601-02

Period/Movement: Baroque (Naturalism, Tenebrism)

Original Location: Originally commissioned for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Current Location: The painting was rejected by the church, and it is now in the Louvre Museum, Paris

Patron: The commission was likely from the Cardinal del Monte

Material/Media/Medium: Oil on canvas

Technique: Chiaroscuro, Tenebrism, Realism

CONTENT

The painting depicts the moment of the Virgin Mary's death, with her body lying in a state of repose, surrounded by grieving apostles and other figures.

Mary is depicted with an earthly, real appearance, in contrast to the idealized representations often seen in religious art. Her face is pale and lifeless, and her hands rest quietly on her chest, emphasizing the reality of death rather than the divine.

The apostles and figures gathered around her bed show deep emotional response, with some in anguish, while others appear to hold vigil, which emphasizes the human sorrow at the passing of the Virgin.

The emotional realism and the physicality of the figures underline the human aspect of the sacred event—a departure from idealized portrayals of the death of holy figures.

FORM

Composition: The central positioning of Mary’s body draws attention to her physical absence of life, while the surrounding figures convey an emotional response. The figures are arranged in a balanced manner around Mary, which emphasizes both human grief and the divine.