IBC exam

1/117

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

118 Terms

Berry & Zhou Reading: An institutional approach to cross-national distance

key focus: a new institutional and multidimensional approach to measuring cross-national distance

9 proposed dimensions of cross-national distance:

economic: GDP per capita, inflation, trade openness

financial: credit access, stock market development

political: democracy level, policy stability, WTO membership

administrative: colonial ties, legal system, language

cultural: adapted from WVS to replicate Hofstede’s dimensions

demographic: age structure, life expectancy birth rate

knowledge: patent output, scientific publication rates

global connectedness: tourism inflow/outflow

geographic: physical distance

Haxhi reading: institutional perspective on corporate governance

CG: structure of rights and responsibilities among stakeholders in a firm

core concerns:

monitoring executives and boards

protecting minority shareholders

corporate disclosure and transparency

employee and stakeholder participation in decisions

formal vs informal institutions in CG

formal institutions: laws, listing rules, compliance codes

informal institutions: business culture, networks, social norms

hard law vs soft law (CG)

hard law: mandatory, state enforced, one-size-fits-all

soft law: voluntary, self regulatory, flexible

→ governed by comply or explain principle (firms must disclose deviations, not necessarily comply)

comparative models of CG: two types

shareholder oriented (Anglo-American)

dispersed ownership, strong investor protection, flexible labour market

CEO power is high, markets play key monitoring role

stakeholder oriented (continental Europe)

concentrated ownership, weaker minority rights, broader stakeholder goals

includes employees, creditors, and state as key actors

3 European stakeholder CG models

state capitalist hybrid (France, Belgium): strong capital markets, confrontational labour relationsh, active state

consensus stakeholder model (Germany, Netherlands): coopoerative labour-management, dual boards, less state interference

mixed market economies (Eastern and Southern Europe): weak enforcement, low market capitalization, civil law influence

International Business

the pursuit of value creation by public and private organizations in foreign countries

includes both foreign firms entering a country and domestic firms expanding their operations abroad

motives for internationalizing

growth (new markets)

resource seeking (natural or human resources)

risk reduction (diversified portfolio)

efficiency (cost advantages through operations)

strategic assets (technology, talent, brand)

Liability of Foreignness

when foreign firms face disadvantages in host countries. Arises from:

spatial distance: travel, coordination costs

cultural unfamiliarity: learning curve, local adaptation

legitimacy issues: seen as outsiders

home-country constraints: limits on what MNEs can do aborad

MNEs cope with distance via

developing internal capabilities (FSAs)

isomorphism: mimicing local firms to gain legitimacy

CAGE framework (Ghemawat)

4 dimensions of distance:

cultural: values, religion, language, social norms

administrative: legal and political systems

geographic: physical distance, time zones

economic: income levels, development, labour costs

OLI model/Eclectic Paradigm (Dunning)

3 sources of advantage:

Ownership (O): inque firm assets (tech, brand skills)

Location (L): host country benefits (resources, demand)

Internalization (I): benefits of controlling operations rather than outsourcing

Uppsala Model

firms expand gradually as they gain experience

early steps: export to nearby countries

later steps: set up sales subsidiaries and production facilities

Institution-Based View (IBV) (Peng)

\emphasizes the role of institutions in shaping firm behavior and performance. It suggests that organizations operate within a framework of formal (laws, contracts, regulations) and informal norms (social expectations, corruption, trust) that affect their strategies

Williamson: New Institutional Economics

focuses on how institutions reduce transaction costs and shape organizational behaviour

core assumption: humans are boundedly rational and opportunistic

4 level of social analysis (williamson model)

L1: Embeddedness (informal institutions)

L2: institutional environment (formal rules of the game)

L3: governance (contracting and organizational forms)

L4: resource allocation and employment (neoclassical economics)

the 4-level model helps explain:

why cultures and legal systems differ across countries

how firms must adapt governance depending on institutional environments

L1: Embeddedness (informal institutions)

customs, traditions, norms

evolve very slowly

not easily altered through policy

most relevant to cultural context and long-term path dependency

L2: institutional environment (formal rules of the game)

laws, constitutions, and property rights

set by the state, influenced by history, politics, culture

change is infrequent but faster than L1

L4: resource allocation and employment (neoclassical economics)

prices, output, incentives

occurs continuously (daily or weekly)

assumes that institutional frameworks are fixed

traditional economics focuses only here, but NIE emphasizes that L1-3 shape L4 outcomes

L3: governance (contracting and organizational forms)

firms choose governance structures to minimize transaction costs

highly sensitive to asset specificity, uncertainty, and frequency of transactions

change is relatively quick

North Reading: Institutions

institutions are humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction

include: formal rules (constitutions, laws, contracts) and informal norms (traditions, customs, codes of conducts

key assumptions:

economic actors have bounded rationality

information is costly to obtain

there is uncertainty in human interaction

path dependency

current choices are shaped by historical trajectories

institutions evolve through (2)

path dependency

incremental change

institutions vs organization

institutions = the rules

organizations = the players

poor institutional frameworks lead to

high transaction costs

weak property rights

limited investment and innovation

NBS systems are shaped by

how the state, financial system, and labour market operate

how authority and trust are distributed

how coordination between firms and institutions is structured

3 structuring dimensions of business systems (NBS)

the nature of the firm: owernship, internal labour markets, degree of decentralization

market organization: degree of competition

coordination and control systems: role of trust, hiearchy, relationships

6 types of business systems (NBS)

fragmented systems

coordinated industrial districts

compartmentalized systems

collaborative systems

highly coordinated systems

state organized systems

fragmented systems (NBS)

firms operate independently with minimal institutional coordination

labour markets are flexible and short term

institutions offer little support for innovation

example: Southern Italy, Mexico

coordinated industrial districts (NBS)

dense inter-firm networks in specific regions

SMEs are embedded in local ecosystems with vocational training

examples: Northern Italy, Catalonia

compartmentalized systems (NBS)

segmented institutions with limited cross-sector coordination

firms are often large, diversified conglomerates

labour and education are poorly integrated with business needs

examples: UK, US, Canada

collaborative business systems (NBS)

strong cooperation between firms, labour, state, education

stable employment and high investment in human capital

examples: Germany, Netherlands

Highly coordinated systems (NBS)

strong integration between institutions: education, labour, business

long-term planning and consensus-based governance

firms emphasize competence building and systemic innovation

examples: Japan (post WWII), Switzerland

state organized systems (NBS)

state controls industrial policy, directs innovation efforts

firms may be state owned or tightly regulated

competition is limited, innovation is top-down

examples: postwar france, south Korea (modern)

5 types of innovation strategies (NBS)

dependent

craft-based responsive

generic

complex, risky

transformative

dependent innovation (NBS)

firms rely heavily on foreign firms for tech/design

internal capacity is weak, often just assembly

common in fragmented systems

craft based responsive innovation (NBS)

rooted in local know-how and artisan skills

highly adaptive, incremental, tailored to niche markets

common in coordinated industrial districts

generic innovation (NBS)

standardized, efficiency-focused innovation

easily scaled across markets

typical in compartmentalized and state-organized systems

complex, risky innovation (NBS)

high-tech, long term innovation

high uncertainty and investment

strongest in collaborative and highly coordinated systems

transformative innovation (NBS)

disruptive innovation that creates or redefines industries

requires long-term capital, stable institutions, and a bold vision

found in highly coordinated and collaborative business systems

tacit vs codified knowledge

tacit: hard to transfer, requires context, often tied to skills and experience

codified: transferable, documented, accessible to outsiders

knowledge variety (cognitive vs organizational)

cognitive complexity: how many fields of science/tech are combined

orgnaizational complexity: how many institutions contribute to, and store knowledge

North definition: Institutions

“humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interactions.”

These include:

Formal institutions: laws, property rights, constitutions, regulations

Informal institutions: traditions, customs, norms, social conventions

institutional theory assumptions

bounded rationality: decision makers operate under constraints (limited time, info, cognition)

self-interest: actors aim to maximize outcomes but may act in self-interest

→ institutions help align incentives and reduce transaction costs

institutional weakness

when rules are ambiguous, inconsistent, and unenforced → leads to unpredictability and higher risk

agency theory and institutional context

principle-agent problems are central to corporate governance

owners (principles) want returns

managers (agents) may pursue self-interest

institutions reduce agency problems via:

legal protections

formal governance mechanisms

transparency and oversight

institutional variation across countries

institutional weakness: when rules are ambigous, inconsistent, or unenforced

rule based vs relationship based systems

rule based: transparent, legalistic, stable for outsiders

relationship based: opague, informal, harder to navigate

varieties of capitalism (NBS)

state involvement

financial system

skill development

authority and trust

political risk in IB

political risk = threat to business from political events or instability

types of political risk:

ownership: expropriation, nationalization, corruption

transfer: sanctions, embargoes

operational: security issues, regulatory interference

how to mitigate political risk

international strategies:

legal tools, risk insurance

diversify FDI locations, build strategic alliance

local strategies:

partner with locals, engage stakeholders, maintain low porfile

contribute visibly to local economy to build goodwill

the dutch case/VOC

Netherlands’ business system is shaped by:

water management (canals)

trade (Dutch East India Company)

Calvinist values (thrift, sobriety, responsibility)

governance: coalition based, consensus building

social traits: low power distance, high individualism

economic structure: small firm dominance, export driven economy

Dutch corporate governance

weak market for corporate control → hostile takeovers rare

strong anti-takeover protections: priority shares, certificates

limited cross-shareholding and bank ownership

concentrated shareholding remains common

governance focused more on stability, coordination, and stakeholder interests than market discipline

Hofstede: levels of culture

national level: deep values acquired early in life, hard to change

organizational level: based more on practices, can be learned or unlearned

individual level: shaped by both national and organizational influence

culture

the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes members of one group from another

6 cultural dimensions: Hofstede

power distance

uncertainty avoidance

individualism vs collectivism

masculinity vs femininity

long term vs short term orientation

indulgence vs restraint

power distance (Hofstede)

degree of acceptance of unequal power and authority

high PDI: centralized structures, obedience, status hierarchy

low PDI: consultation, equality, flatter organizations

implications: affects management stryle, employee relations, decision making

uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede)

comfort with ambiguity, unpredictability, and risk

high UAI: preference for rules, structure, risk aversion

low UAI: flexibility, informal norms, innovation tolerance

implications: influence contract design, planning legal protections

individualism vs collectivism (Hofstede)

relationship between individual and group

individualistic cultures: autonomy, self interest, personal achievement

collectivist cultures: group loyalty, harmony, consensus

implications: affects HR practices, incentives

masculinity vs femininity (Hofstede)

distribution of emotional gender roles

masculine cultures: competition, assertiveness, material success

feminine cultures: care, modesty, quality of life

implications: influences negotiation style, workplace dynamics, leadership expectations

long term vs short term orientation (Hofstede)

time horizon of values and decision making

long term: thrift, perserverance, future-oriented planning

short term: tradition, face-saving, immediate results

implication: influences investment behaviour, product cycles, customer relationships

indulgence vs restraint (Hofstede)

extent to which desires and impulses are freely expressed

indulgent: leisure, optimism, freedom

restrained: duty, control, pessimism

implications: marketing, motivation systems, consumer culture

core takeaways for week 3: cultural distance

hofstede dimensions provide a structured, quantifiable way to compare cultures

support Kogut & Singh’s CD Index: cultural distance calculated from dimension differences

model is foundational for CAGE framework (Ghemawat) → cultural component

helps IB firms decide:

how much to adapt vs. standardize across cultures

whether to enter via JV, acquisition, or greenfield

how to manage cross-cultural teams, incentives, and conflictS

Reading: Hofstede, Schwarts, or managerial perceptions?

key cultural frameworks compared

Hofstede’s dimensions (4 used here): power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism, masculinity

Schwartz’s dimensions: conservatism vs autonomy, hierarchy vs egalitarianism, mastery vs harmony

managerial perceptions → captured via direct Likert-scale survey responses on perceived cultural difference

key findings:

all five CD measures positively related to likelihood of greenfield investment

greater CD: higher tendency to choose GF over acquisition

Hofstede and Schwartz had similar explanatory power

most influential dimensions:

hofstede: power distance, individualism

schwartz: conservatism, hierarchy, egalitarian commitment

Dikova & Van Witteloostuijn: Cross-border acquisition abandonment and completion

higher formal institutional distance (esp. procedural complexity) → lower probability of completion and longer deal duration

cultural distance in power distance and uncertainty avoidance → reduces completion likelihood

experience with prior CBAs increases resilience to institutional distance

especially effective against formal barriers like regulatory hurdles

experience has a moderating effect, but doesn’t eliminate delays entirely

effect of institutional and cultural differences on Mergers and Axquisition

institutional and cultural distance can:

reduce likelihood of deal completion

increase the time between announcement and closing

two types of institutional distance matter:

formal: legal procedures, investor protections

informal: power distance, uncertainty avoidance

higher instituional distance:

integration more difficult

post-merger performance may suffer

firms are more likely to prefer GF over acquisiton

Scott institutional frameworks: 3 pillars

regulative (rules)

normative (values)

cognitive (beliefs)

iceberg model of culture

surface level (visible): behaviours, symbols, customs

deep level (invisible): values, assumptions, beliefs

most cultural influence operates below awareness

criticism: hofstede’s model

pros:

clear dimensions, widely used

strong empirical base

cons:

based on 1 company, 1 industry

dimensions may be outdated or too broad

overlooks within-country cultural diversity

assumes cultural stability (ignores change over time)

GLOBE project

aims to link leadership effectiveness to cultural values → finding: leadership preferences are contextual

9 dimensions

power distance

Uncertainty Avoidance

Institutional & In-Group Collectivism

Humane Orientation

Assertiveness

Gender Egalitarianism

Future Orientation

Performance Orientation

Shenkar’s criticism of cultueral distance

critiques CD as overly simplistic and flaws

7 hidden illusions/assumptions:

symmetry: assumes A → B = B → A

stability: assumes cultures don’t change

linearity: assumes impact of CD is always linear

causality: assumes CD directly causes business outcomes

discordance: assumes all dimensions matter equally

corporate homogeneity: ignores firm-level cultural variation

spatial homogeneity: assumes countries are culturally unform

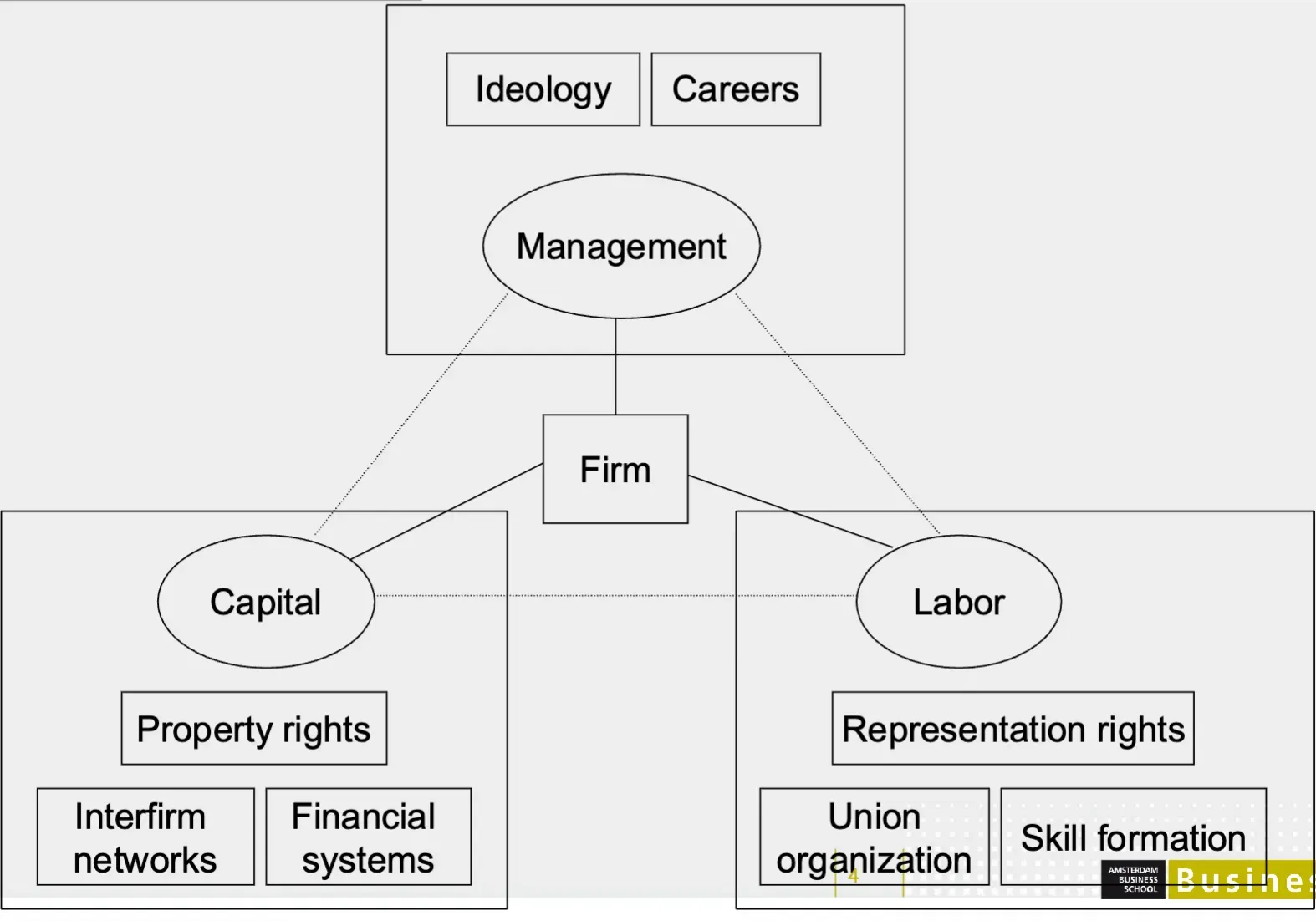

Aguilera and Jackson: crossnational diversity of corporate governance

model that puts corporate governance into three key stakeholder groups: capital, labour, management

→ diversity in CG stems from national institutional configuartions that shape how these actors interact

Capital: dimensions and institutional influences (A&J model)

dimensions that define capital:

financial vs strategic interests: financial = focus on returns, strategic = control

liquidity vs commitment: liquid capital exists easily, committed capital is locked in

equity vs debt control: equity = shareholder governance, debt = creditor oversight

institutions that influence capital:

property rights

financial systems

interfirm networks

labour: dimensions and institutional influences (A&J model)

dimensions that define labour

internal participation vs external control

internal: involvment in decision making

external: reliance on strikes, bargaining, protests

firm specific vs portable skills

specific = investment in the firm, higher stake

portable = exit easier, less incentive for participation

institutions shaping labour:

representation rgihts (weak (US) = external control, strong (Germany) = internal participation)

union organization (class unions = external control (US, UK), enterprise unions = internal participation (Japan)

skill formation systems (firm based or corporatist (Germany, Japan) - firm specific skills, internal voice, market or state based (US) = portable skills, internal voice)

management: dimensions and influences (A&J model)

dimensions:

autonomous vs. committed

→ autonomous = mobility across firms, external job markets

→ committed = long-term careers in one firm, internal promotion

financial vs. functional orientation

→ financial = focus on shareholder value, finance metrics

→ functional = technical competence, production, operations

institutional influences:

managerial ideology

→ US: generalist, finance-driven, hierarchical (autonomous + financial)

→ Germany: technical, pluralist, consensus-based (committed + functional)

career patterns

→ open markets (US): external hiring, high pay dispersion, performance incentives

→ closed markets (Japan): internal promotion, job security, collective management

stakeholder interaction types (A&J model)

class conflict

insider-outsider conflict

accountability conflict

Haxhi & Aguilera: Institutional configuration approach to cross-national diversity in corporate governance

explains why corporate governance (CG) codes vary across countries

rejects single-variable explanations (e.g., legal origin or stakeholder/shareholder dichotomies)

proposes an institutional configurational framework based on three institutional domains:

→ Capital, Management–Labour, and the State

investigates how these domains interact to shape:

code voluntarism

diversity of issuers

institutionalization (how embedded codes become in national practice)

institutional domains and their roles (H&A paper)

Capital domain

refers to the structure and fluidity of financial markets

includes: size of capital markets, property rights protection (minority shareholder protections)

Management–Labour domain

captures labor-management relations and authority structures

includes: degree of cooperation or conflict, strength of managerial dominance

State domain

degree of legal intervention or regulatory activism

includes: legal tradition (Civil Law vs. Common Law), permissiveness vs. interventionism

Code domain

soft law approach

features of governance codes (3) (H&A paper)

voluntarism: codes are typically nonbinding

diversity of issuers: many different types of actors are involved in making codes

institutionalization: extent to which codes are embedded, accepted, and revised over time

mechanisms of CG (H&A paper)

Institutional complementarity

→ interactions between institutional domains can reinforce or balance each other

→ e.g., permissive state + strong capital + cooperative labor = pluralistic governance norms

Equifinality

→ different combinations of institutional domains can lead to similar outcomes

→ e.g., both Belgium (Civil Law) and USA (Common Law) reach high code institutionalization through different routes

4 governance types (H&A)

P1: market driven

P2: stakeholder oriented consensus

P3: state centred

P4: inconsistent/mixed market

P1: market driven (H&A)

State | Capital | Management–Labour | Code Voluntarism | Issuer Diversity | Institutionalization | Examples |

Permissive state(minimal interference) | Fluid capital markets (dispersed ownership, investor pressure) | Weak labor coordination (limited voice) | High | High | High | UK, USA |

P2: stakeholder oriented consensus (H&A)

State | Capital | Management–Labour | Code Voluntarism | Issuer Diversity | Institutionalization | Examples |

Permissive state (enabling, not enforcing) | Smaller capital markets (bank- or family-based) | Coordinated labor (collective bargaining, trust-based systems) | High | Medium | High | Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark |

P3: state-centred (H&A)

State | Capital | Management–Labour | Code Voluntarism | Issuer Diversity | Institutionalization | Examples |

Interventionist state (strong regulatory role) | Concentrated capital (state or elite control) | Fragmented/conflictual labor (limited inclusion) | Low | Low | Medium–High | France, Belgium |

P4: inconsistent/mixed market (H&A)

State | Capital | Management–Labour | Code Voluntarism | Issuer Diversity | Institutionalization | Examples |

Interventionist civil law state | weak capital markets (low protection, low capital) | Fragmented labor (low institutional strength, class conflict, state dependency) | Low | Low | Low | Greece, Italy, Portugal |

oversocialization and danger in institutional theory (A&J)

Oversocialization = relying too heavily on abstract, generalized social rules while ignoring variation and agency

A&J argue for actor-centered institutionalism, emphasizing:

→ Stakeholder identity and preferences

→ How actors engage with institutions and co-create governance practices

Governance should be seen as the outcome of structured but negotiable relationships

diversity levels explained

result of:

institutional environment

industry characteristics

organization factors

actor coalitions

approaches to enhancing diversity (pros and cons)

self-regulation/voluntary codes (CGCs)

pros: flexible, less resistance

cons: often symbolicindustry standards/best practices (esg ratings)

pros: peer benchmarking, can work well in high public visibility

cons: uneven uptake across firms and sectors, no guaranteed processquotas (Norway 40%)

pros: rapid change in numbers, signals commitment

cons: provokes backlash, risks focusing on compliance over inclusionlegal requirements (California state bill 826)

pros: strong enforcement, creates legal accountability

cons: can be challenged as unconstitutional, less flexible

california case

SB-826 required public companies headquartered in California to have women on their boards

Initially led to rapid increases in female board representation

But faced legal challenges → declared unconstitutional in 2022 (equal protection clause)

Highlighted the tension between legal activism and business autonomy

Reinforced the importance of combining policy tools (law + soft power + investor pressure) for lasting impact

what is CG

ensuring that those who provide capital (owners) can secure returns and monitor control

agency problem (Jensen & Meckling)

when principals (owners) hire agents (managers) to make decisions

agents may pursue personal interest over firm value

governance mechanisms are needed to align interest and reduce agency cost

mechanisms of governance

informal: trust, norms, reputation

formal:

regulation (laws, codes)

ownership structures (blockholders, activism)

boards (structure, committees)

incentives (pay, bonuses, stock options)

external pressures (auditors, analysts, media)

key CG actors

owners: individuals, banks, governments, etcx

managers: training, mobility, executive compensation (a governance mechanism that seeks to align managers’ and owners’ interests through salary, bonuses, and especially long-term incentive compensation contingent on performance such as stock options)

boards: dual leadership, committees

employees, unions stakeholders

country level actors: legal systems, capital markets, product/labour markets

ownership patterns (CG)

Anglo-American (US, UK): dispersed ownership

Continental Europe (Germany, Spain, Italy): concentrated ownership

business groups, cross-shareholdings, golden shares

OECD 2020: significant variation in ownership concentration by market and by company

Netherlands: 121% market cap/GDP

US: 212%, Switzerland: 257%, Sweden: 194%

emerging markets: BRICs often show high concentration, political ties, and informal controls

boards of directors variation

vary in:

size

independence (insiders vs. outsiders)

composition: one-tier (US, UK) vs. two-tier (Germany, NL)

committees: audit, compensation, nomination

dual leadership: separation of CEO and chair roles

codetermination (employee representation in Germany’s supervisory boards)

market vs network oriented systems

market-oriented:

capital market discipline, M&A activity, faster restructuring

risks: short-termism, hostile takeovers, underinvestment

network-oriented:

strong ties, trust-based control, long-term perspective

risks: excessive protection, undervaluation, limited innovation

comparative CG models

shareholder-oriented (Anglo-American)

control via markets, liquid stock exchanges, independent boards

emphasis on transparency and shareholder value

strengths: capital allocation, innovation funding, profit focus

weaknesses: short-termism, hostile takeovers, inequality

stakeholder-oriented (Rhineland, Germanic/Scandinavian)

control via consensus, banks, dual boards, employee voice

strengths: internal monitoring, long-term investment, trust

weaknesses: entrenchment, inefficiencies, non-liquid markets

CG in BRIC (brazil, russia, india, china)

stakeholder view of the firm

firms operate within a web of stakeholders:

internal: owners, boards, management, employees

external: governments, creditors, NGOs, regulators, customers

systems interact with labor, capital, and product markets