Waterfowl Ecology: Exam 2

1/26

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

27 Terms

Why waterfowl are important ecologically, environmentally, economic, and culturally?

Ecologically

Forage at rates that can affect trophic relationships

Move plants and animals in their feathers, on their feet, and in their guts

Environmentally

Biomonitors of environmental quality & change

Disease vectors and sampling units

Habitats are important for a diversity of plants and animals which includes people

Economically

Hunting, duck stamps, bird watchers

Culturally:

Cave drawings

Domestication

Cultural symbols

Regions with the most critically endangered animals, Islands and why?

Endemism → small, isolated populations with no backup elsewhere.

Introduced predators (rats, mongooses, pigs, cats) to which island species have no defenses.

Habitat loss on small landmasses hits harder.

Diseases (avian malaria in Hawaii).

Low reproductive rates common in island species.

Limited dispersal → can’t recolonize easily.

Waterfowl and life-history strategies

Migration: dabblers often short–mid distance; Arctic nesters are long-distance; sea ducks migrate late and long.

Survival: varies with body size (large ducks and geese survive better).

Foraging:

Dabblers → surface feeding, seeds/inverts.

Divers → fish/inverts from depth.

Sea ducks → mollusks/crustaceans.

Geese → grazing herbivores.

Nesting:

Ground nesters (most ducks).

Cavity nesters (wood duck, goldeneye, bufflehead).

Overwater nesters (ruddy duck, redhead, canvasback).

Pairing:

Seasonal monogamy (most dabblers).

Multi-year pair bonds (swans, geese).

Early vs. late pair formation (divers later; dabblers earlier).

Important waterfowl habitats

Prairie Pothole Region (PPR) → primary breeding area for North American ducks.

Mississippi Alluvial Valley (MAV) → major wintering area.

Arctic / subarctic → breeding grounds for geese, sea ducks, many divers.

Gulf Coast → wintering.

Atlantic Coast / Chesapeake Bay → wintering.

Great Lakes → staging + some breeding for divers.

Nutrient needs by season

Winter:

Carbohydrates for thermoregulation, maintaining body heat, preventing starvation.

Spring migration & pre-breeding:

Protein for muscle rebuilding + follicle development.

Calcium for eggshell formation.

Lipids (fat) for migration energy.

Breeding/incubation:

Females use stored fat (especially capital breeders).

High-energy foods needed for long incubation fasts in some species.

Capital/endogenous vs. income/exogenous strategies

Capital (endogenous) strategy

Birds store nutrients before breeding and use internal reserves to produce eggs and maintain incubation.

Species: common eider, northern pintail (partially), many Arctic nesters.

Used when: early breeding, limited local resources, short seasons.

Income (exogenous) strategy

Birds rely on nutrients acquired at the breeding site to produce eggs.

Species: mallard, gadwall, most temperate dabbles.

Used when: food is abundant on breeding grounds.

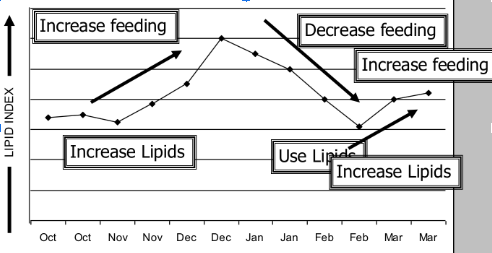

General Lipid Pattern Through the Annual Cycle (Oct–Apr)

History of waterfowl research

Late 1800s–early 1900s: Severe overharvest and market hunting pressure on ducks and geese prompted early conservation concern and the need for population data.

1900s–1910s (Lacey Act 1900, MBTA 1918): Federal protection laws (Lacey Act, Weeks–McLean, Migratory Bird Treaty Act) shifted birds from “market resource” to protected migratory wildlife, setting the stage for regulated seasons and research-based management.

1920s (Missouri v. Holland, 1920): Supreme Court confirmed federal authority over migratory birds, allowing nationwide research and regulation rather than a patchwork of state rules.

1930s (Dust Bowl era): Massive declines in waterfowl led to key funding and survey tools—Duck Stamp Act (1934), early international duck censuses (1935), and Pittman–Robertson (1937)—to pay for habitat and science.

Post-WWII 1940s–1950s: Cheap planes and pilots after WWII enabled standardized aerial breeding-population and habitat surveys (BPOP/WBPHS), forming the core long-term data set for waterfowl trends.

1947–1960s (Flyways & banding): The Flyway system was created (1947) and structured banding/recovery data were used to map migration routes, estimate survival/harvest, and tie specific populations to specific regulations.

1960s–1990s (harvest & hunter data): Parts Collection Surveys, wingbees, and later the HIP program (fully implemented 1999) provided large-scale, standardized data on species/age/sex composition, hunter success, and total harvest.

Mid-1990s–present (Adaptive Harvest Management): Adaptive Harvest Management (started 1995) and later multi-stock models formally linked BPOP, banding, HIP, and habitat data into a structured, model-based system to set seasons and learn about population responses over time.

Timing of pairing + primary aim of winter

Energy-rich habitat = Early pairing

Energy-poor habitat = Later pairing

Pairing occurs on wintering areas and during spring migration because it provides benefit to females (fitness benefit)

SURVIVAL

How we evaluate body condition through the year

We track body condition by repeatedly capturing waterfowl through the annual cycle (winter → migration → breeding → molt), measuring mass, structural size, and nutrient reserves, and then comparing these across seasons and populations

Environmental conditions + body size and timing of pairing

Individuals in better condition pair earlier. Paired individuals gain from shared resource knowledge and are ‘dominant’. Food shortages + increased energetic costs =less time for courtship and pair maintenance

Big ducks = big fuel tanks → early pairing

Small ducks = small fuel tanks → must spend more time feeding → later pairing

Sex ratios in waterfowl and why

Females die more often due to nesting/predation risk.

Females invest more energy, lowering survival.

Males survive winter better because of larger body size and less reproductive burden.

Leads to more males than females

Precocial or altricial? What does that mean for male behavior?

Waterfowl are precocial:

Hatch with open eyes, down feathers, mobility, feeding ability.

Very little parental feeding.

Effect on male behavior:

Males are not needed for chick rearing → pair bonds are seasonal and males leave after mating.

Leads to:

Male competition for mates

Sexual dimorphism (bright males, dull females)

Forced copulation in some species (unfortunate but ecologically relevant)

When and what resources are limiting

Waterfowl are precocial meaning ducks are fully feathered with eyes open and walking after hatch

Males aren’t needed after mating

why the behavioral dominance hypothesis doesn’t apply to waterfowl

The behavioral dominance hypothesis posits that female birds move farther south to avoid dominance by and competition with the larger males that can tolerate harsh winter conditions better than smaller females

This is counter intuitive in ducks, because early pairing male ducks must follow their females south in the autumn,while later pairing ducks do not.

Why small, ephemeral wetlands are critical

Seasonal/temporary wetlands provide:

Rich invertebrate boom → essential protein for females during pre-breeding.

Brood-rearing habitat → shallow, warm, predator-diluted, high productivity.

Spring migration foraging → extremely high nutrient availability.

Pair isolation habitat → spreads out pairs and reduces harassment.

Refueling sites before nesting.

These wetlands are disproportionately important even though they’re small.

Why waterfowl lay large eggs

They need:

Large yolks for precocial chicks (who must walk and feed immediately).

Large eggs require huge protein and lipid demand → explains the reliance on:

Capital breeding in some species

High-protein spring foraging

High need for calcium (snails, grit, water chemistry)

Large eggs = more developed hatchlings = higher survival.

patterns of nutrient acquisition (capital vs income)

Capital Breeders dabbling. Geese and swans. ENDOgenous

Rely on stored fat and protein

Protect high-quality migration and winter habitats

Income Breeders diving. EXOgenous

Rely mostly on food they eat on grounds, especially invertebrates

Protect small, seasonal wetlands rich in invertebrates

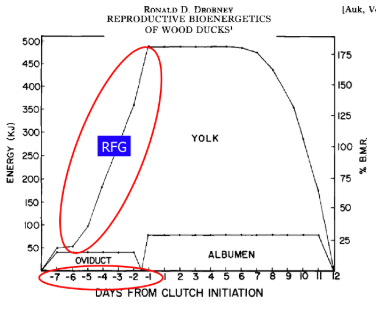

Rapid Follicle Growth (RFG) and energetic pattern of females

RFG

Most cost of egg production is cost of producing yolk, which contains the energy needed by the developing embryo

To cope with this demand, waterfowl do not deposit yolk simultaneously in all the developing follicles

Instead, yolk is deposited in a lesser number of follicles and done so over a period of days

Rapid periods of RF= adaptation to exploit seasonal habitats and avoid predation risk

By late incubation, however, females had lost 42% of original body mass, 89% of lipids, 35% of protein. Some Lipids NEAR ZERO AFTER incubation

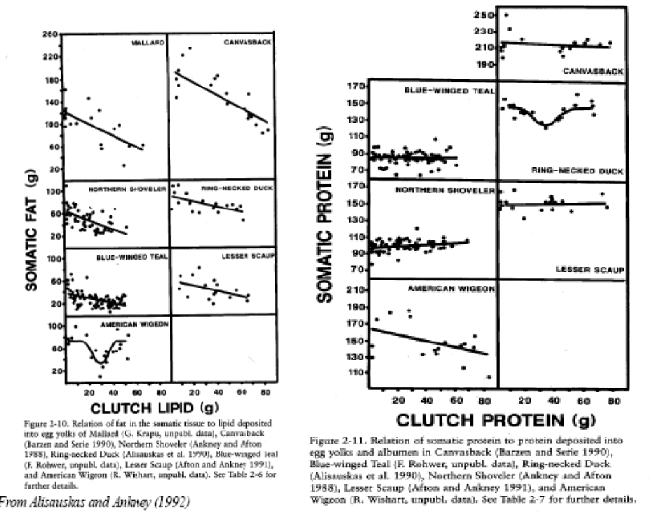

Explain these graphs

Somatic fat & Clutch lipid

How much stored fat a female uses to make her eggs

As she lays eggs, her fat reserves go down on the graph.

Somatic protein & Clutch protein

Whether the female has to break down her own muscles/tissues to finish making her eggs

If the line goes down, it means she is using her own body protein to complete the clutch. (Endogenous/Capital)

Line goes straight = Exogenous/Income

Protein is much more variable bc of differences in food habits

What to say on an exam

These graphs show the relationship between somatic reserves (fat or protein) and the nutrients deposited into eggs. Species with strong negative slopes lose body tissue as clutch nutrients increase, indicating capital breeding, where stored reserves fuel egg formation. Species with flat slopes rely on income breeding, acquiring nutrients directly from the environment during laying. The variation among species reflects differences in migration timing, breeding latitude, and food availability, which has major implications for habitat management.

Drivers of breeding-period philopatry & nest failure in waterfowl

Greater investment in reproduction

Females return to their natal or previously successful breeding sites because they invest heavily in reproduction and benefit from reusing familiar, safe habitat

Farming practices likely represent the greatest threat to duck nesting habitat

Native grassland → Cropland

Drivers of duckling mortality & timing

greatest loss of ducklings is in the first 2-3 weeks when ducklings are small and thus susceptible to the widest array of predators as well as hypothermia

Data streams used in Adaptive Harvest Management (AHM)

Population monitoring & Hunting data

Two primary components in the matrix for mid-continent Mallard AHM season setting

Population size

# Canadian Ponds

How Atlantic Flyway AHM differs from other flyways

The Atlantic Flyway does not base its duck seasons on Mid-Continent mallards like the other flyways do.

Instead, it uses a different model that looks at multiple duck species that are actually important and abundant in the East.

Types of uncertainty in AHM & mid-continent Mallard models

mid-continent Mallard AHM population models.

AHM

Harvest

Harvestable surplus

MCM AHM

Enviro variation: Cant predict conditions of environment

Partial controllability: We cant guarantee regulations will be followed 100%

Partial observability: We cant observe population dynamics constantly

Structural uncertainty: We arent sure how population dynamics work