Sleep Across the Lifespan

1/43

Earn XP

Description and Tags

childhood, adolescence, adulthood and sex differences

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

44 Terms

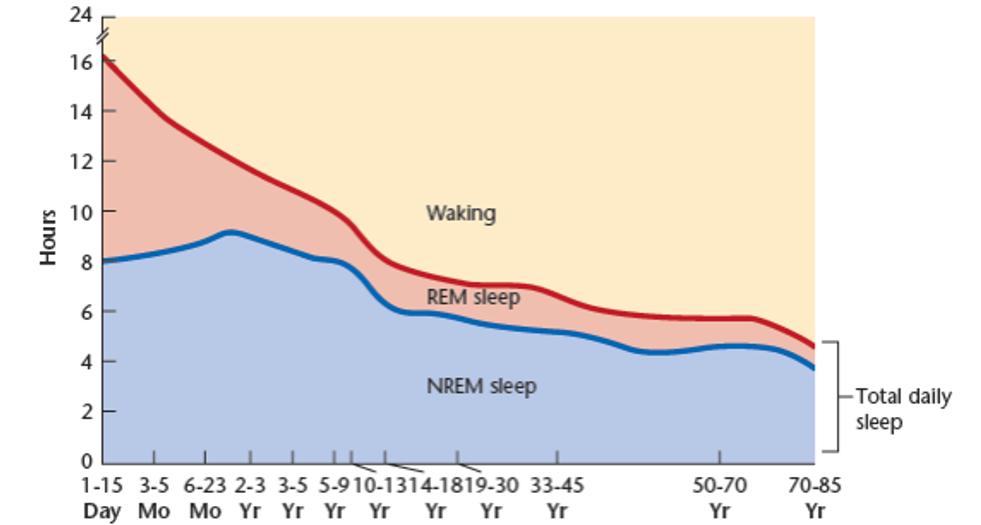

How does the amount of sleep change over the lifespan?

Sleep overall decreases with age

REM is very high when very young (below 2 years)

REM makes a sharp decline until 10-13 years where it declines more slowly

NREM stays more stable but increases slightly around 23 months until 10ish years old, where it makes a gradual decline

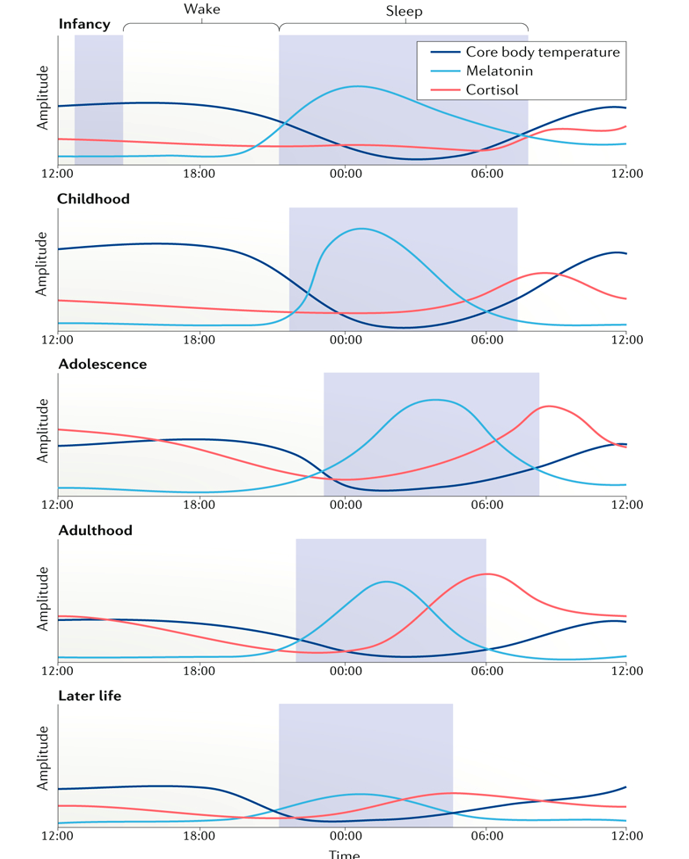

What are the changes in circadian rhythm observed throughout life?

chronotype shifts later in adolescence & earlier in later life (accompanied by shifting of timing of melatonin release)

cortisol highest in amplitude in adolescence and adulthood and gets earlier as we age

melatonin amplitude highest in childhood

all values (body temp, cortisol & melatonin) at their lowest amplitude in later life

body temp becomes more stable throughout the day as you age

What happens in prenatal early entrainment?

Since the foetus cannot recieve light/external cues, they (somewhat) entrain their circadian rhythm using signals from their mother (info through placenta or moveement) e.g. melatonin/cortisol release, temp changes.

How can external cues help entrainment for premature infants in the NICU?

(Olgun et al. 2024):

Compared to those in constant bright-light or dim-light conditions in NICU

Regular light–dark schedules support the maturation of sleep–wake and melatonin rhythms earlier

Also had greater and more rapid weight gain, shorter hospital stays, feed orally sooner, spent fewer days on ventilator assistance, cried less & more active in the daytime

How is infant sleep different?

Infant sleep does not fit the polysomnographic criteria of other ages (NREM, REM sleep), thus, sleep researchers use a different nomenclature

^ 3 types - Quiet Sleep (QS), Active Sleep (AS) and Indeterminate Sleep (IS)

Sleep 16-18h of sleep each day, most of which is spent in Active Sleep (AS)

Alternate between sleep and wakefulness throughout the 24h period – polyphasic sleep

QS and AS alternate in ~ 60min cycle

Newborns often go right into AS

What is Quiet Sleep (QS) for infants like?

Similar to Short Wave Sleep in adults with absence of body movements

What is Active Sleep (AS) like for infants?

Irregular brain waves, body movements and occasional vocalizations (similar to REM)

What is Indeterminate Sleep (IS) like for infants?

The sleep between QS and AS

What is sleep like in infancy?

Strong homeostatic drive for sleep thus, frequent naps throughout the day

Gradually begin to spend more time awake during the day and more time asleep at night

At ~3m infant sleep begins to consolidate and to resemble sleep in later life (AS begins to resemble REM sleep and QS begins to resemble more NREM sleep).

By 12m of age babies nap on average twice daily and as they get older they have shorter naps

What is sleep like in childhood?

Sleep is fairly consistent from weekdays to weekends

At ~ 2 years old, REM sleep drops to adult levels

Homeostatic sleep pressure in children is still very high

Specifically what are the stages of sleep like for toddlers and preschoolers?

They move quickly into deep sleep (stage 3)

They often ‘skip’ the first REM episode and go back to NREMs, mainly SWS, and then have a REM bout

Gradually fewer awakenings

It is difficult to wake children from NREM sleep (early part of the night vs early morning)

Pros and Cons of Longitudinal Sleep studies

Pros:

Data over time with the same ppts - accurately measuring changes

Cons:

Very expensive

Hard to recruit ppts for that length of time

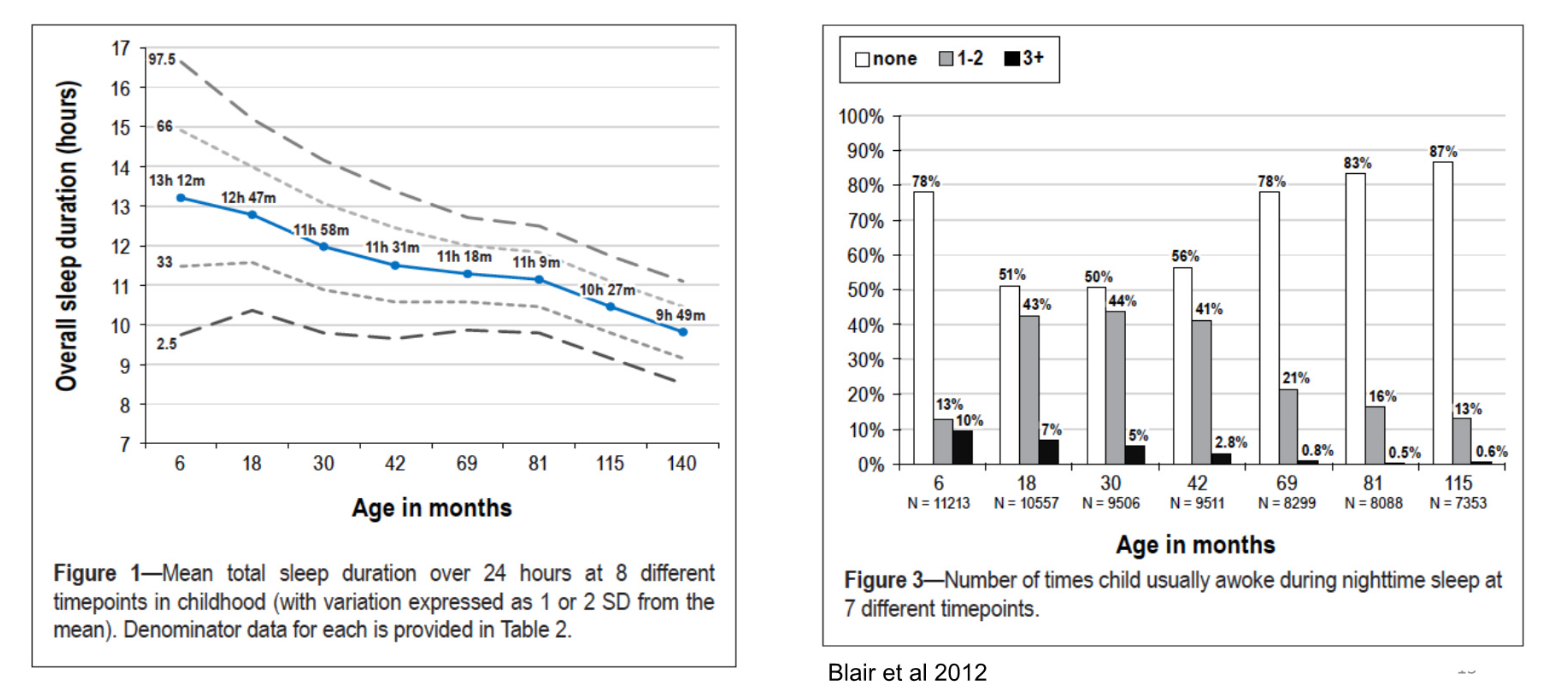

What was the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)? What did they find?

Fraser et al. 2012 (& Blair et al. (2012) - extra analyses?):

Followed up ~7 thousand children born in 1991-1992 until they were about 11 years old

Children sleep more when they are young

Massive variability, especially in younger children

Way less awakenings as they get older

Found that girls slept ~5-10 mins more than boys because of later wake-up time

Comparison to another study:

Children in the ALSPAC slept about 1 hour less in infancy and childhood compared to another cohort of children studied in Zurich born in 1974 -1978 and 1978-1993 and slept half an hour more in later childhood

What are the recommended Sleep Durations for Children and Teens

Infants (4-12m) - 12-16h

Children (1-2y) - 11-14h

Children (3-5y) -10-13h

Children (6-12y) - 9-12h

Adolescents (13-18y) - 8-10h

Are there gender differences in sleep (in infancy?)

Yes, boys lag behind girls in CNS development - sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is more frequent in boys (1.5x) - laying children on their back can help with this

By 6 months, girls have more organized sleep patterns, which suggests earlier entrainment (also evidenced by the circadian pattern in core temperature)

Boys on average:

have shorter sleep bouts (5-10min on average) and earlier awakenings than girls

spend less time in quiet sleep (more active sleepers), wake up more frequently, and have lower sleep efficiency

Does insomnia vary by gender and age in children?

Yes - Calhoun et al (2014):

looked at insomnia in 700 children (5-12 year old) using PSG and parental reports

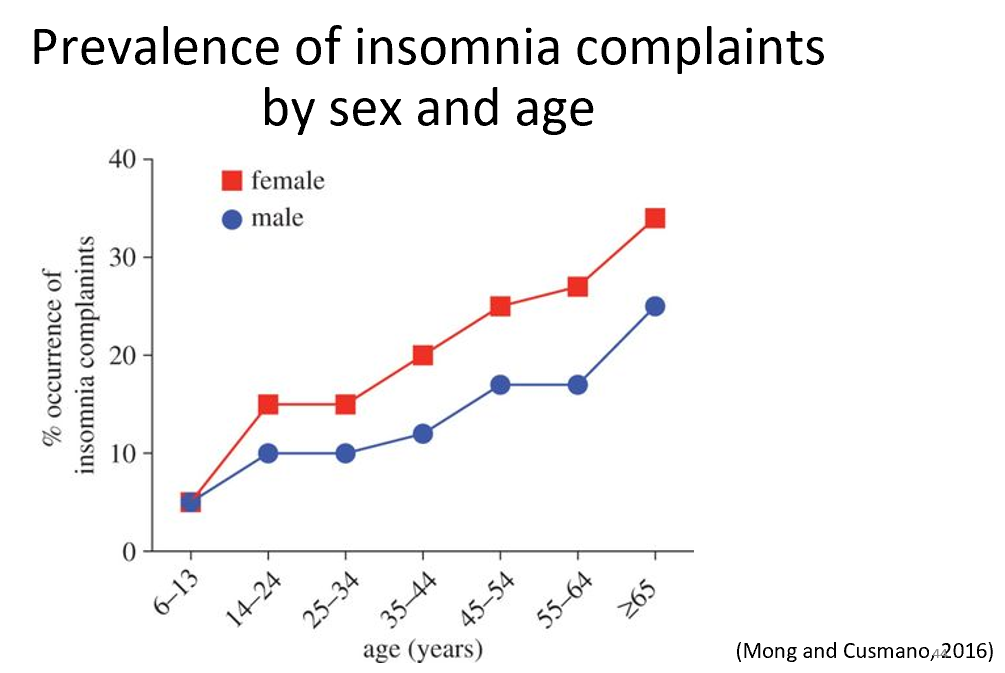

insomnia prevalence similar until ages 11-12 where female ppts had significantly higher levels

Is sleep important for children’s mental health and emotional state?

Yes - Gruber et al 2012:

Randomized control trial with blind teacher ratings on Emotional Lability, Restless-Impulsive Behaviour and daytime sleepiness (Conners' Global Index)

Measured sleep in 34 children aged 7-11y for 5 days by actigraphy (Baseline) and then assigned them to either 1h more or 1h less time in bed for a week

When sleep was extended (~27min per night) there was detectable improvement in emotional lability and restless-impulsive behaviour scores of children in school and a significant reduction in reported daytime sleepiness

When sleep was restricted (~54min per night) there was detectable deterioration on these measures.

What does research day about depression and sleep/active hours (in adolescent boys)?

Merikanto et al (2017):

small sample of depressed non-medicated adolescent boys vs. healthy controls

Recorded rest-activity cycles for 25 days using actigraphy

Found blunted circadian rhythms in the depressed group compared to controls

Depressed boys had lower activity levels and lower circadian amplitudes compared to healthy controls

Their most active hours were the hours spent in school, whereas the non-depressed boys were also active in the evenings and during weekends (perhaps more hobbies or social events)

What does research say about sleep, behavioural issues and cognitive performance in children?

(Astill et al 2012):

Involved analysis of data from ~36,000 healthy school-children 5-12 years old

Sleep duration was positively correlated with cognitive performance

evident in executive functioning

in complex tasks involving several cognitive domains

it was also positively correlated with school performance

Short sleep duration was associated with behavioural problems, both internalizing and externalizing

What are activational effects and how can these impact sleep?

influences of hormones like testosterone and estrogen on the brain and body during puberty - ‘activation’ of structures that were organised during prenatal development (sexual differentiation)

results in changes in behaviour

changes in ovarian steroid secretion in women coincide with sleep complaints

How does sleep change during puberty?

homeostatic sleep pressure slows so that adolescents can delay sleep for longer - go to bed later (Carskadon et al. 1997)

circadian phase becomes more delayed which leads to more wakefulness in the evenings and later bedtime, which can be an hour at the onset of puberty

SWS begins to decline

What gender differences in sleep appear during puberty?

SWS begins to decline - this decline in girls occurs around 1.2 years earlier compared to boys.

sleep complaints begin to arise, with girls reporting more difficulties than boys

girls have longer sleep onset latency and greater rates of insomnia, which persist across the lifespan

insomnia symptoms are correlated with behavioural and mental health issues in boys and girls

What historical changes are happening with adolescent’s sleep?

national surveys in the US, only 7% sleep 8-9.5h per night

between 12-18 years of age, the probability of getting at least 7h or sleep each night drops by about half (7 hours of sleep is 2h less than the recommended 9 hours of sleep)

‘monitoring the future’ survey (1991-2012) with more than 270,000 high-school students found a major decrease in sleep over the past few years, with the greatest shift observed in 15-year olds

also found across countries - Matricciani et al. (2013)

coined as the ‘great sleep recession’ (Keyes et al 2015, Journal Pediatrics)

What has been found over time between sleep and mental health in young people?

Fuligni & Galvan (2022):

Getting less sleep is associated with worsening mental-health, such as increases in feelings of sadness and hopelessness (Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System)

What may be factors keeping young people awake?

Electronic screens and light exposure

Social media (anxiety, other concerns)

Homework

Work/Study

Caffeine

Energy drinks

Substance use

All investigated in the literature

What has been found about the parental role in adolescent’s bedtimes?

In early years, bedtime routine is sacred - bedtimes are usually set by parents in childhood but less so in adolescence

US study found less than 1-in-5 have a parent-set bedtime at age 10 and this drops to less than 1-in-20 at age 13 (Carskadon, 1990)

A shift in parental involvement from enforcing bedtime to becoming the alarm

Greater difference between weekdays and weekends (lesser sleep hygeine!! - extra literature)

What about digital devices and sleep?

Pervasive use of screen-based media may be responsible for reduced sleep in children and adolescents (Le Bourgeois et al 2017-Pediatrics)

devices are often (75%) found in the bedroom (a significant predictor of reduced bedtime) and 60% of adolescents report using the device 1h before bedtime

What factors are at play in the use of digital devices?

A systematic literature review between 1999-2014 on screen use and sleep found that screen use was negatively impacting sleep by delaying sleep time - therefore reducing sleep (Hale and Guan, 2015)

Digital use may interfere with sleep on multiple levels:

delayed bedtime (time displacement)

light exposure

psychological stimulation (social media)

Does the type of device matter?

Yes, smartphones and computers are more interfering than TV watching, however, many studies focus on digital use as a whole and have found it to be detrimental (around the world).

What else has been found about digital use that could relate to sleep?

UK - children (8-18y olds) are spending 4.45h per day on electronic devices and indicated an increase in digital use in the last few years 2010-2015 as well as an increase in alone-together time (Mullan 2018)

Computer use during leisure has increased from 2001-2016, (large sample) a part of a sedentary lifestyle in both adults and adolescents (Yang, et al, 2019, JAMA)

How does digital use relate to physical activity?

Study launched in Denmark (Pedersen et al. 2022):

88% of adults report using the internet daily whereas school children (24% of boys and 19% of girls) spend at least 4 hours per day using digital devices (Folkesundhed, 2019)

45 families as experimental group and 44 families as control group

Baseline data and then for 2 weeks they had no smartphones and only be allowed screen time 3 hours per week or less

Found a substantial increase in children’s physical activity (which therefore may increase sleep)

How do early school start times affect teens?

NSF survey in 2006 found that 28% of high school students reported falling asleep in class at least once a week

US Air Force – first semester freshmen randomly assigned to different schedules:

randomly assigned to take a class before 8am = significantly worse academic performance in their first hour class compared to those with the first hour assigned at or after 8am

In addition, performance throughout the day was reduced

(circadian shift means later start times are better)

How can later start times benefit teens?

later school start times are consistently associated with fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety

improved general mental health and reduced psychologically relevant behaviour problems such as emotional problems and hyperactivity/inattention

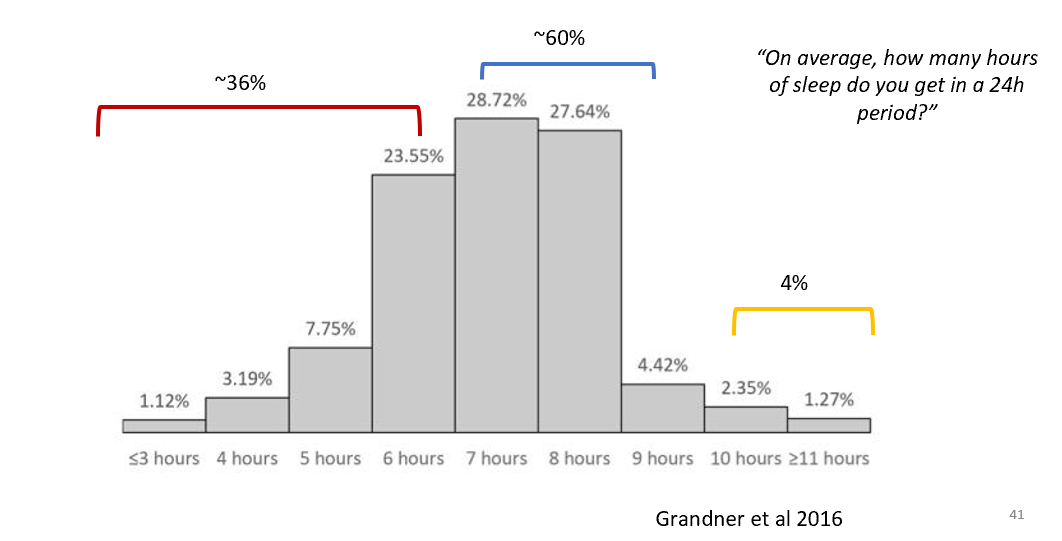

How much sleep are adults getting?

environmental factors contributing to insufficient sleep

many adults do not get the recommended 7-9 hours of sleep

gradual reduction of sleep per decade of our lives with a tendency towards lighter sleep which plateaued at the age of 60 years

only about half of adults get enough sleep

^Grandner et al. 2016

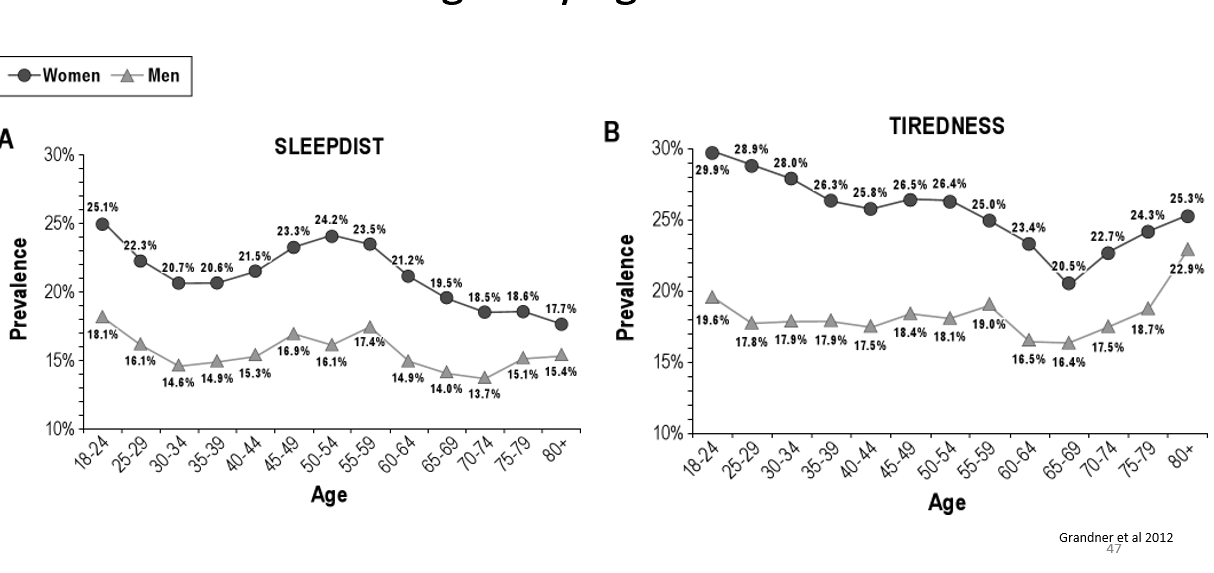

What are the key gender differences in sleep for adults?

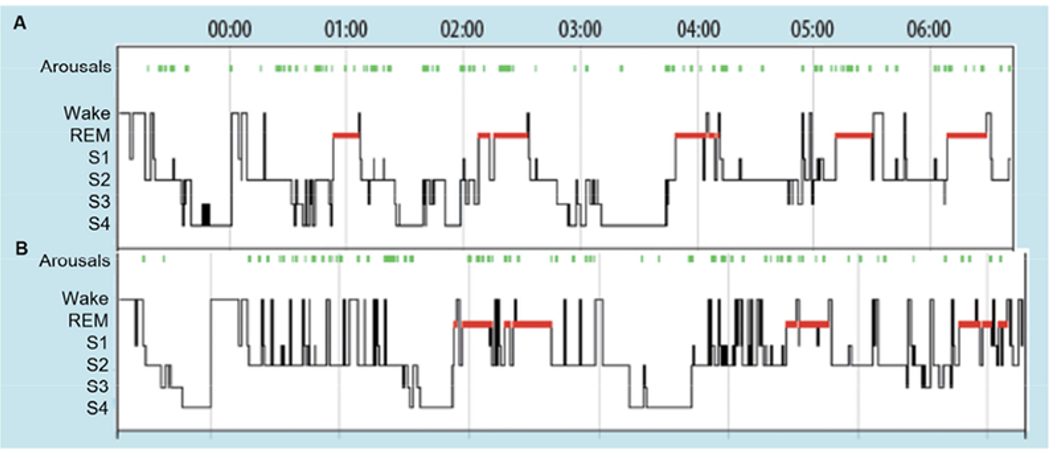

consistent finding = women have better PSG-defined sleep quality than men

women have significantly longer total sleep time and less total wake time, a shorter sleep onset latency and better sleep efficiency compared to men

portable PSG measures also find that men have lighter sleep compared to women - they have more arousals and lower sleep efficiency

SWS activity is greater in women across ages and greater in recovery sleep

however, in subjective measures of sleep, women report insufficient sleep and more sleep-associated disruptions compared to men - paradox

Circadian rhythm differences between genders

women tend to go to bed earlier and wake up earlier compared to men

on average, women have earlier circadian rhythm timings such as temperature and melatonin

mechanisms are still not known

What is the difference in insomnia between the genders?

women have a 40% greater risk for insomnia compared to men

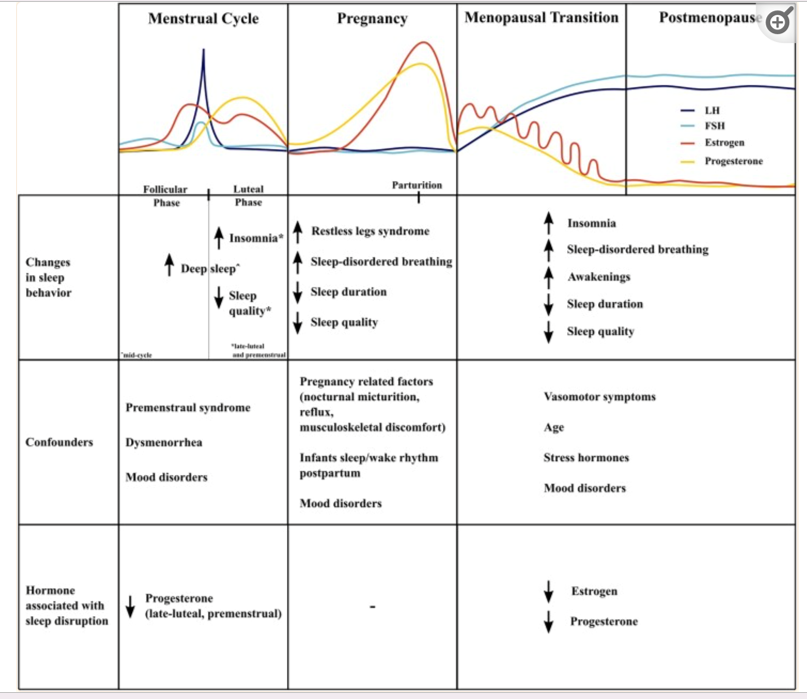

Are there differences in women across their reproductive age?

Yes - there are differences between menstruation, pregnancy, menopause and post menopause (Haufe and Leeners, 2023)

Sleep disturbances increase when there are fluctuations in ovarian hormones, as in puberty, menstrual cycle (Baker et al 2007), pregnancy and menopause (Moline et al 2004)

What happens to levels of sleep distrubance and fatigue across lifetime and across genders?

Grandner et al 2012:

women overall more fatigue and more sleep disturbacnes over whole adulthood

menopause seems to create rise in sleep disturbance

What can change in sleep during menopause?

increased sleep disruption, mainly sleep awakenings

menopause is fluctuations and eventual decline in oestrogens

Lampio et al 2017 - the only longitudinal study of sleep and menopause at baseline and 6 years later with 60 women participants (47-52years of age)

(pre-menopause at the top of graph)

What disturbances can occur in older age that affect sleep?

changes in medical conditions, medications, changes in social engagement and lifestyle, living environment etc. may change sleep

may be more sedentary, less active and socially active which may impact sleep homeostasis and circadian regulation

life events such as loss of loved ones, moving into care homes, can be stressful

What happens to sleep in the elderly?

typically more fragmented sleep but major individual differences - 44% of elderly adults complain about their sleep at least a few nights per week (American National Sleep Foundation)

changes become intense and more noticeable in the elderly

longer sleep onset latency and more night-time awakenings

circadian rhythms advance, causing early evening sleepiness and early morning awakenings

sleep at night may decrease, but total sleep in 24h period may not (due to napping)

more opportunities to nap

What do measures of sleep tell us about old age differences?

measures of daytime sleepiness suggest that the elderly are sleepier during the day

in surveys, older adults report less satisfying sleep compared to when they were younger

there is a (on average) reduction in the depth and quality of sleep, with decreased sleep duration and increased nocturnal awakenings (Dijk and Duffy, 1999)

more likely to be awoken by auditory stimuli which is in agreement with changes in sleep depth

What can rodent studies tell us about sleep in old age?

deterioration of rhythmicity (e.g. amplitude of times sleep hormones) as a result of a decline of the integrity of the SCN

transplantation studies have revealed that young SCN grafts lead to improvement of the activity rhythm & amplitude of aged mice

(Hurd and Ralph, 1998): suggests that age-related phenotype is caused primarily by deterioration in the function of the SCN

with advancing age melatonin production decreases which may also contribute to changes in sleep patterns

emerging evidence suggests that sleep disruptions and complaints precede the emergence of dementia and related disorders (Pase et al, 2017)