Industrial revolution

1/39

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

40 Terms

Domestic system

The system where people worked in their homes or small workshop rather than in factories

People involved in the domestic system

It involved the whole family: grandparents, parents and children. The goods that were made included shoes, socks, buttons, lace, hats, gloves, nails, chains and clay pots. One of the most popular goods made in peoples homes was woolen cloth. This high quality material became famous around the world and, as the population increased, was in great demand in Britain too.

From sheep to shop

In the domestic system a clothier (cloth merchant) for example, bought wool from farmers who had sheared their sheep. The clothier then took the wool to villagers in their houses. The family could work the hours they wanted, as long as they finished the cloth on time. The clothier would them collect the cloth, pay the family, ad take the cloth to a different house to be dyed and made ready for sale

Money-mad merchants

Many cloth merchants made a fortune from the cloth trade. Their profits made were larger by clever inventors who built brilliant machines to speed up the cloth making process. For example in 1773 the Flying Shuttle helped wavers make cloth much more quickly. In 1764 the Spinning Jenny made the production of thread quicker. If more cloth could be made quickly them more cloth could be sold which meant more profits

Flying shuttle

It allowed one weaver (instead of two) to weave much faster by automatically passing the shuttle (which carries the weft yarn) across the loom.

Impact on production:

Doubled the speed of weaving cloth.

Increased the amount of fabric that could be made in less time.

Led to a higher demand for thread because fabric was being woven so quickly.

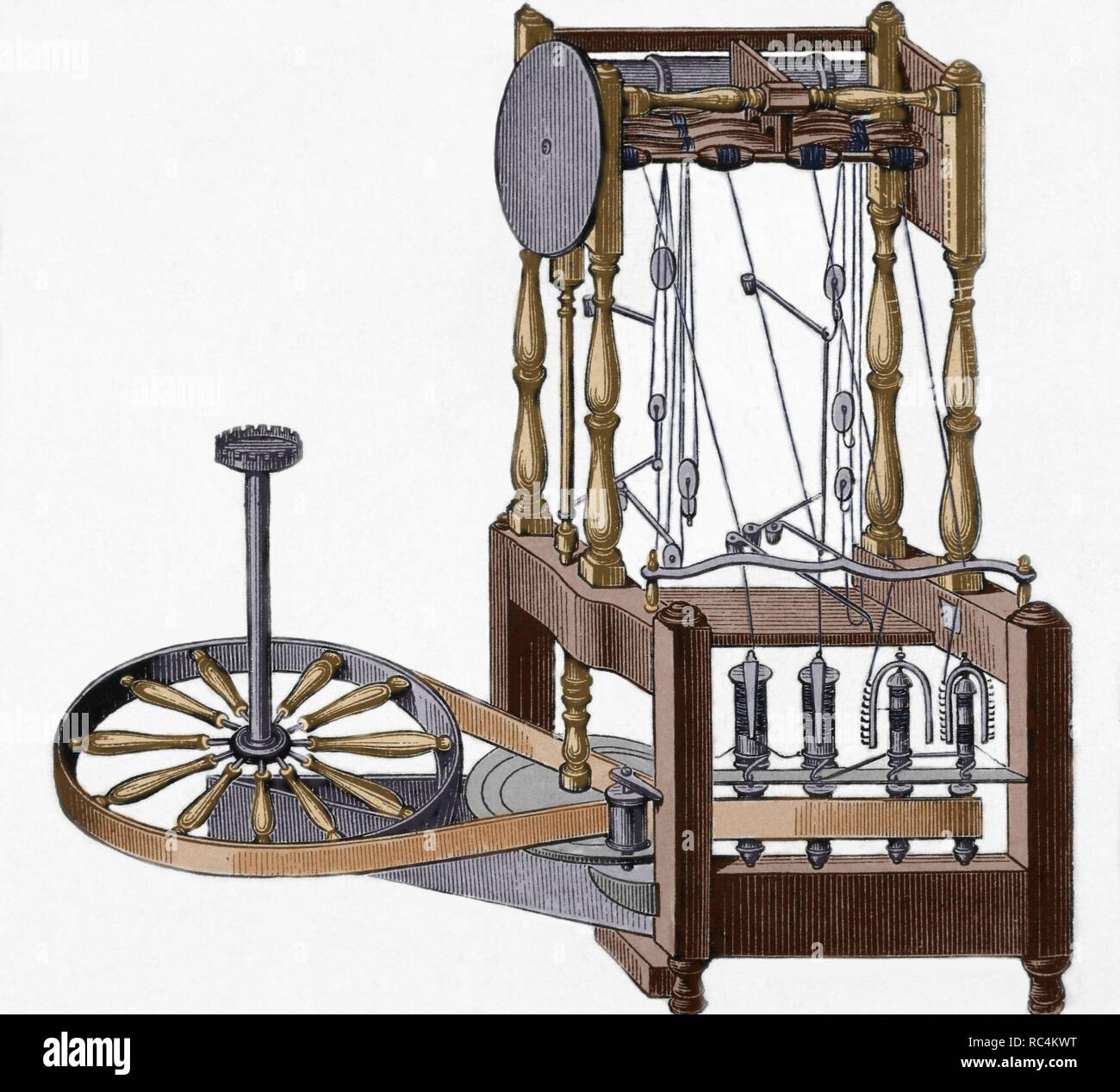

Spinning Jenny

1764.It allowed a single worker to spin multiple spools of thread at once (originally 8, later many more).

Impact on production:

-Massively increased the amount of yarn/thread that could be spun.Helped keep up with the demand for thread caused by faster weaving machines like the flying shuttle.

Made thread cheaper and more available, speeding up clothes production.

The first factory

The man responsible for for ending the domestic system was a former wig maker called Richard Arkwright. In 1769, he invented a machine called the spinning frame. It could produce good strong thread very quickly. But it was so big it couldn’t fit in peoples homes, also the moving parts were so heavy that it couldn’t be operated by hand and had to be powered by a waterwheel. Arkwright solution was to put his huge spinning machines in specially created buildings known as factories or mills. His factory opened in 1771 at Cromford in Derbyshire.

The death of the domestic system

As more factories were built, millions of people left their villages and went to work in them. Factories guaranteed year-round work and a steady wage. Workers rented homes near to factories that the owners had built.

Spinning frame

1769. The spinning frame used rollers to spin stronger, finer,and more consistent thread automatically. How it worked: It was powered by water wheels (instead of by hand), which made it much faster and more efficient than earlier spinning machines like the spinning jenny.

Impact

This thread was better for making warp yarns (the threads that run lengthwise in fabric), which meant stronger and more durable cloth. Because it was powered by water, it could run all day, leading to mass production of thread and fabric. The spinning frame was too big for homes, so it was set up in large buildings (factories) near rivers. This helped begin the factory system.

Spinning Mule

1779. What it did:The spinning mule combined features of the spinning jenny and the spinning frame to produce high-quality, strong, and fine thread. How it worked:

It moved back and forth like a mule (hence the name), drawing out and spinning fibres with great precision.

How did factories create towns

The new factories pulled people into towns from the countryside with the promise of regular work for all the family and good wages. Factory owners built houses for their workers to rent and people began to set up shops and inns so the workers could buy food and drinks. Soon roads were being built, along with churches, schools and places of entertainment. These places needed shopworkers, teachers and nurses, for example - as well as the builders, carpenters and laborers to help build them. And all of these people needed more houses. Before long, places that were once tiny villages had grown into large towns - and small towns became huge overcrowded cities.

Owners want more

By 1800, factories were producing all sorts of items and making their owners rich. But factory owners faced a problem. They wanted their machines to run all the time. Most of their early factories used water as an energy source to drive the machines. This power was created by a huge waterwheel that was turned by the fast flow of a nearby river

Change to steam

Water wasn’t reliable enough. So factory owners turned to a new form of power steam engines. These had first been used to pump water out of underground mines but they were slow and kept breaking down. But, in 1768 a Scottish inventor named James watt met a businessman called Mathew Bolton at a science club called the Lunar Society in Birmingham. Together they developed a new steam engine that Watt had been working on. Together they developed a new kind of gear system that turned a wheel just as a river would.

Factory fever

Now factories could be built anywhere. By 1871, only 3% of factories were still using water wheels. Steam powered factories started to appear all over Britain. By 1850, Britains factories produced two thirds of the world’s cotton cloth - even though cotton didn’t grow in Britain. Nearly half of the world’s hardware (tools, pots, pans) also came from Britain. Industry had become mechanized and Britain was now known as the workshop of the world.

Child labour

Poor children didn’t go to school, so they would work with their parents. Orphans were sent to work by local authorities. They were known as pauper apprentices and were given food, clothing and a bed in an apprentice house. In return they had to work very hard for factory owners

Reasons for child labour

Cheap labour: employers preferred them for lower wages

Small size: They were useful in tight spaces (mines)

Family needs: Parents sent kids to work due to financial struggles

Industry demands: High demand for labour

Few regulations: Lack of laws protecting exploitation of children

Were all factories the same

Some employers believed that happy workers were good workers, so they tried to provide decent living and working conditions for their workers. Robert Owen for example, built good quality houses, schools, shops and pars for his workers on New Lanark, Scotland. He also reduced working hours. Elsewhere factory owners built good quality villages for their workers. But these villages and town were exceptions and the vast majority of factories and the towns that surrounded them were dangerous and healthy places to live and work.

Time for change

In the 1800s many people thought that the government shouldn’t interfere with the way factories were run. They believed that it was up to owners to decide how to run them, and that introducing laws to improvements could harm profits. They also argued that reducing working hours for women and children might cause money problems for the family. However a growing number of people were very concerned about working conditions, especially for children. Reformers like Lord Shaftesbury, Richard Oastler, John Fielden and Micheal Sadler began to campaign for laws to protect mine workers. Some were motivated by their religious beliefs, while others might work harder if they were treated better.

Reformer

A person who campaigns for change

Change is coming

After reading reports, Parliament accepted that it had a duty to look after the more vulnerable people in society. From 1833 new laws made changes to the working lives of women and children. Men, it was believed that they could look after themselves. Some factory owners hated the change they felt politicians had no right to interfere. But new laws kept being passed and, gradually began to protect more and more workers. Inspectors were appointed to enforce the laws and by 1900 factories and mines had become safer and bearable.

1833 Factory Act

No children under nine to work in factories

Two hours of school per day

Nine hours of work per day for children aged 9-13

Factory inspectors appointed

1842 mines act

No women or children under ten to work under a mine

Many inspectors appointed

1844 Factory act

No women to work more than 12 hours per day

Machines to be made safer

1842 Ten hour act

Maximum 10 hour day for all women and workers under 18

1871 trade union act

Trade unions made legal. Workers were all doing the same job - like railway workers were dockers for example, were allowed to join together (form a union) to negotiate with their employers for improvements to pay and working conditions. As a last resort all union members could go on strike

1878 factory and workshops act

No children under ten could. Work

No women could work more than 60 hours a week

Laws on safety, ventilation and mealtimes

1895 factory act

children under 13 to work a maximum of 30 hours per week

What is coal

Coal is a hard, black rock that is burried underground. Specialist workers, called mines, get coal out of the ground from mines. Once it’s lit it burns for a long time. In the late 1700s coal was very cheap and used to cook an heat houses. As population increased more coal was needed, and it began to be used to power steam engines in factories. It was also used in the making of bricks, pottery, glass, beer, sugar, soap and iron

Black gold

By the 1800s coal was also required to power steam trains and shops. The need for more coal meant more money for mine owners. So they were making so much money from their coal they began to call it ‘black gold.’

Iron

Iron had been produced in Britain since roman times but in the 1700s it began to be used in all areas of life. Army’s used them for canons, navy ‘iron clad shops, and the new factories were held with iron beams and used iron machines that were powered by iron steam engines. Iron was used to make tools, trains and railway tracks, fireplace gates, iron stoves and iron pans

Making of iron

Iron ore is dug from underground

It’s melted together with limestone and charcoal in a furnace. The iron gets so hot it melts and pours out of the bottom of the surface

Red-hot liquid iron is poured into cases shaped like pots, pipes, cannons, beams etc. Cast iron is strong but it contains air bubbles that can make it brittle.

When cast iron is reheated and hammered the pockets of air are removed it becomes wrought iron. This is purer and stronger and can be bent to make chains, tools, furniture, railway tracks and so on.

Darby family

Abraham Darby I- In 1709 he discovered a way of using coal to make iron. First he heated it to remove the sulphur this makes something called coke. Cast iron made with coke is way better quality then made with coal.

Abraham Darby II- he improved the process invented by his father, removing even more impurities and allowing wrought iron to be made from coke fired coal

Abraham Darby III- He decided to show the possibilities of the use of iron by building a magnificent iron bridge. He made the ironworks at Coalbrookdale famous throughout the world

Why were transport improvements needed

A fast reliable transport system was vital for business and industry from the mid 1700s. Coal had to be taken from mines to factories and towns, cotton had to be moved from ports to factories and finished goods had to be moved to markets, postal service was needed too. Many industries under sea - or river based transport, especially when heavy goods like iron or coal- but dozens of towns were miles away from the nearest river. In the 1700s and 1800s a series of developments and inventions completely changed Britains transport system

Time for turnpikes

In the early 1700s Britains roads were in a terrible state and businesses were suffering. The government decided to divide the main road network into sections, and each section was rented out to a group of business people called the Turnpike Trusts promised to improve and maintain their section of road. In return the trusts were allowed ti charge a toll to everyone who used their section of road. Much of the cash was used to improve the roads and specialist engineers went on to create the finest roads Britain had ever seen. By 1830 there were nearly 1000 turnpike trust improving over 32,000 km of roads.

Canal Mania

The turnpike trusts had given Britain some excellent roads - but they were still too bumpy for fragile goods like pottery and too slow for heavy goods like coal and iron ore. So a new type of transport was developed canals. These were long, narrow, man made channels of still water, which were ideal for moving heavy and fragile goods, so they soon caught on. By 1830 64000Km of canals had been built.

Train travel

When steam engines first appeared in the 1700s, inventors soon worked out ways to make them turn into wheels. A Cornishman called Richard Trevithick built the first ever railway locomotive. In 1804 to win a bet his engine pulled 10 tons of iron and 70 passengers for 14.5km in Merthyr Tydfil, South wales. After this there was a flurry of activity as engineers created lots of different locomotives. By 1900 there were over 32000km of train track that carried millions of passengers every year

James Watt

Born in Greenock, Scotland in 1736, and worked as an instrument maker at the university of Glasgow

In 1764, Watt repaired an old stea, engine. They were mainly used in mines to pump water but were slow and kept on breaking down. He greatly improved the engine making it faster and more reliable. It used less coal too.

In 1781, he designed a new steam engine that could turn a wheel. Now steam power could be used to drive machinery

By 1800 Watt and his business partner Matthew Boulton’s factory in Birmingham was producing some of the world’s finest steam engines. These steam engines helped develop Britains industry so it became a world power

George Stephenson

Born in Wylam, Nothumberland in 1781, his first job at 14 was working at the local mine with his father

In 1841 he designed the first locomotive the Blücher

In 1815 he produced a safety lamp for miners, which could be used safely for areas where methane gas had collected

In 1821 he was given the job of designing the Stockton and Darlington Railway. It opened in 1825 and used his locomotives

He designed and made locomotives for the first city-to-city line - Liverpool to Manchester which opened in 1830.

Micheal Faraday

Born in Newington in 1719

He worked in a bookshop where he became fascinated by science

He was most interested in electricity and magnetism and in 1831 he discovered how to generate electricity

His generator worked on the same basic principle that electric power stations work on today