Coherence II - Explaining Sense: Propositions, Themes, and Discourse Relations

1/15

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Vocabulary flashcards covering key terms from the notes on propositions, themes, and discourse relations in coherence and text structure.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

16 Terms

Proposition

The meaning of a simple affirmative sentence; the minimal unit of meaning; the core of a clause (predicate plus arguments).

Propositional Analysis

a list of minimal meaning units showing which ones are directly related.

Our stony soil provides excellent drainage.

PROVIDE (SOIL Subject DRAINAGE Object)

If you were to enumerate the various uses of paper, you would find the list almost without end.

1 (CONDITION, 2); 2 (ENUMERATE, 3); 3 (USES, PAPER); 4 (VARIOUS, 3); 5 (FIND, 6); 6 (WITHOUT END, 3); 7 (ALMOST, 6)

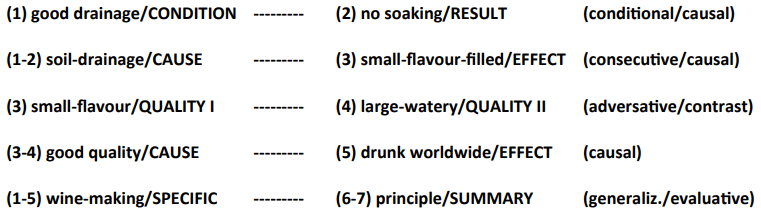

Propositional Relations – (Discourse Relations) : definition + 2 types

The semantic–pragmatic connections between sentences. They act as the “cement” between propositions, holding the text together. These relations can be explicit (with connectors) or implicit, and they shape the overall text structure.

Additive relations: coordinated structures relating to one another through addition, contrast, disjunction etc.

Gold is a precious metal. It is prized for two important characteristics. (addition)

Causal relations: subordinated structures expressing more specific logical relations, e.g. reason, consequence, condition etc.

Our stony soil provides excellent drainage. There is never too much water around for the vines to soak up. (consequence)

TYPES OF CAUSAL RELATIONS(Propositional Relations – (Discourse Relations))

REASON: cause for action;( because,since0

MEANS: instrument to achieve a goal; (by/with)

CONSEQUENCE: result of an action;(so,therefore)

PURPOSE: aim of an action;(in order to, for the sake of)

CONCESSION: cause without logical consequence(if,unless)

Rhetorical Relations: definition + 6 types

Relations speakers or writers use with the intention of changing the opinion, position, or behavior of readers or listeners.

① EVIDENCE: Air pollution got worse in the city. Trees are covered in fine dust.

② JUSTIFICATION: I ate up all the cake. No one seemed to want any more.

③ CONCLUSION: The bike is gone. He must already have left.

④ CONTRAST: This beer here has lots of fizz. The stuff yesterday was smoother and didn’t sparkle that much.

⑤ MOTIVATION: You like being ahead of the news? Order a copy our magazine.

⑥ SOLUTION: The chocolate was dry and crunchy. The new recipe will greatly improve smoothness and creaminess.

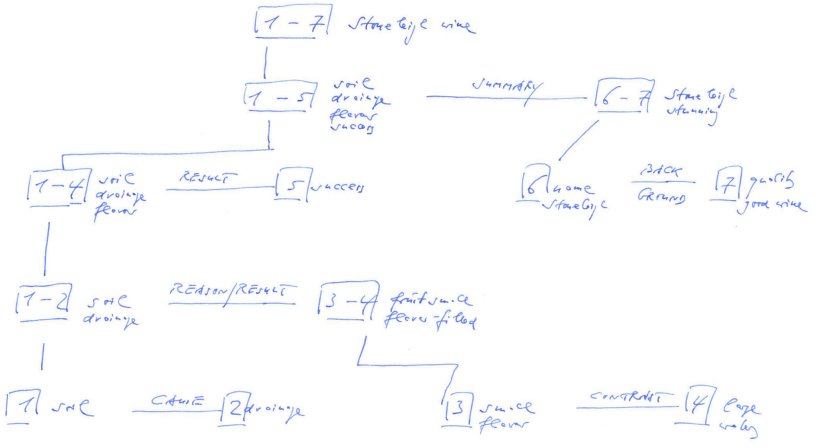

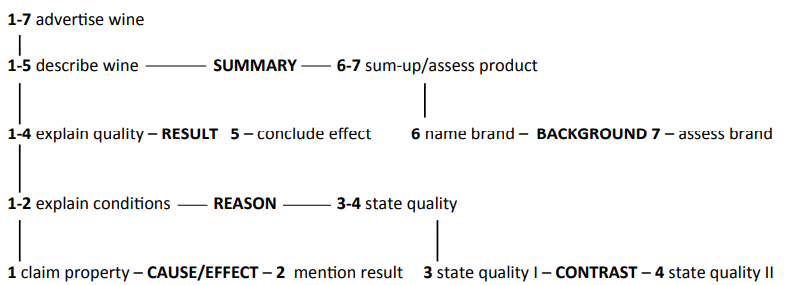

Rhetorical Structure Theory(Texts as Relations)

RST explains how sentences in a text are connected by meaning, with some being main ideas and others supporting them.

A theory that models text structure through rhetorical relations. It divides texts into spans (units), each with a nucleus (essential part) and satellite (supporting part), showing how clauses and sentences connect to form discourse.

EXAMPLE

(1) Gold never needs to be polished and will remain beautiful forever. (NUCLEUS)

(2) For example, a Macedonian coin remains as untarnished today as the day it was made 25 centuries ago. (SATELLITE)

SPAN: 1 Nucleus---------evidence---------2 Satellite

>> Rhetorical Relation: EVIDENCE

Texts as Sequences of Propositions

are organized structures where each proposition contributes to the overall meaning and coherence of the text.

Think of a text like a chain of small statements (propositions).

Example:

"It is raining."

"The ground is wet."

"People are carrying umbrellas."

Texts as Discourse Relations

Here we don’t just see the sentences as separate, but we look at how they are connected.

Example:

"It is raining because the clouds are heavy." (cause–effect relation)

"It is raining. Therefore, people carry umbrellas." (reason–consequence relation)

The text is a network of meanings where sentences are linked by relations like cause, contrast, explanation, elaboration, etc.

Texts as Hierarchical Relations of Spans

how sentences and ideas group into bigger chunks (paragraphs, sections, whole text).

Here we see text like a tree: small ideas group together into bigger ideas.

Example:

Paragraph 1 (about the rain)

Sentence 1: "It is raining."

Sentence 2: "The ground is wet."

Paragraph 2 (about people)

Sentence 3: "People are carrying umbrellas."

Sentence 4: "Children are wearing raincoats."

So, text is not just a flat line of sentences, but an organized structure with main ideas and supporting ideas.

Information Structure in Sentences

THEME AND RHEME – THE ORGANIZATION OF PROPOSITIONS

Theme: old/known/given info; indicates the ‘aboutness’ of a discourse (basis)

Rheme: new/unknown/novel info; makes a statement about the theme (nucleus)

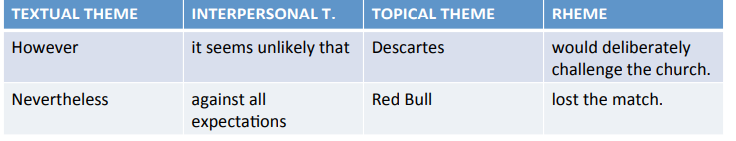

Theme types 3

Topical: the given/known information relating to the discourse topic

Interpersonal: a statement revealing an attitude/evaluation of the entire proposition (i.e. topical theme + rheme)

Textual: utterance elements that link a proposition to the surrounding discourse (co-‐text)

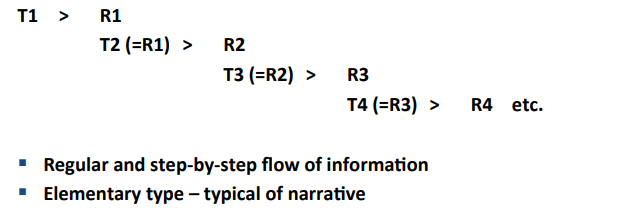

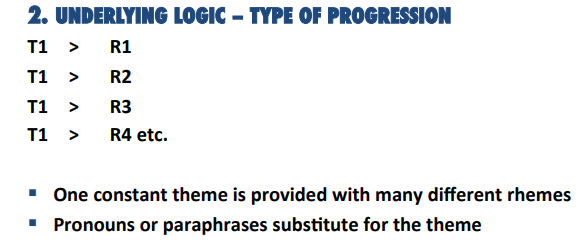

Thematic Progression: definition + 4 types

The typical sequence of Theme (what the sentence is about) and Rheme (what is said about it) in a text. This pattern shapes how the content is organized.

“The dog (Theme) is barking (Rheme)” → “The barking (Theme) annoys the neighbors (Rheme)

1. SIMPLE LINEAR PROGRESSION: rheme of preceding sentence becomes theme of following sentence

2. PROGRESSION WITH A CONTINUOUS THEME: one and the same theme is treated in many subsequent sentences

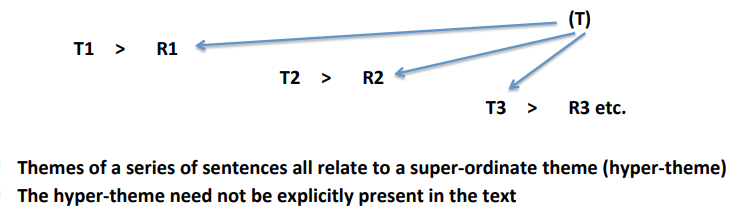

3. PROGRESSION WITH A DERIVED THEME: many consecutive sentences deal with a theme that is not explicitly mentioned (hyper-‐theme)

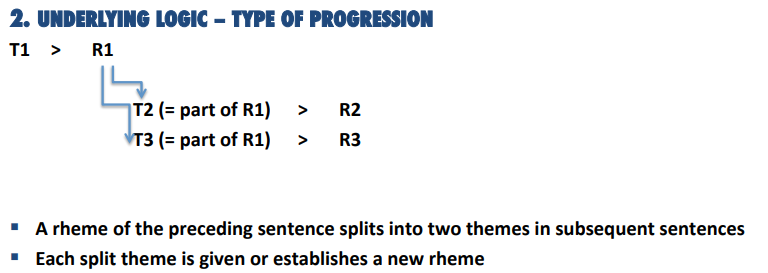

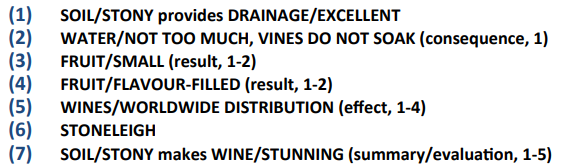

4. PROGRESSION WITH A SPLIT RHEME: a preceding rheme splits into two or more themes

Simple Linear Progression(Thematic Progression)

rheme of preceding sentence becomes theme of following sentence

(1) Larry was playing in the garden.

(2) The garden was just by the roadside.

(3) On the road many cars thundered by.

(4) Cars frightened Larry because of their loud noise.

(5) The roar from the traffic would always make Larry sad and angry.

Progression with a Continuous Theme(Thematic Progression)

one and the same theme is treated in many subsequent sentences

(1) Melbourne is a great city.

(2) It offers a wonderful mix:

(3) it’s cosmopolitan and vibrant, with fantastic parks and walks for pedestrians, cycle paths, good public transport, great restaurants and unbeatable sporting facilities.

(4). It is self-‐contained and compact in a way that Sydney is not – and less up itself.

Progression with a Derived Theme(Thematic Progression)

many consecutive sentences deal with a theme that is not explicitly mentioned (hyper-‐theme)

(1) First the radiator in the car went bad.

(2) Then the starter went out.

(3) Next it was a flat tire.

(4). Then the breaks wouldn’t work well.

(5) After they were fixed the transmission went out.

(6) It had been clear to me for a while that the car had to go.

Progression with a Split Rheme (Thematic Progression)

a preceding rheme splits into two or more themes

(1) Gold, a precious metal, is prized for two important characteristics.

(2) First of all, gold has a lustrous beauty that is resistant to corrosion.

(6) Another important characteristic of gold is its usefulness to industry and science.