roman art

1/130

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

131 Terms

Hellenization of Rome

process by which Greek culture, ideas, art, and practices influenced and were adopted by Roman society, especially during the late Republic and early Empire. This wasn’t a single event, but a centuries-long cultural transformation

have to consider the hellenization of rome also with

an etruscan lens

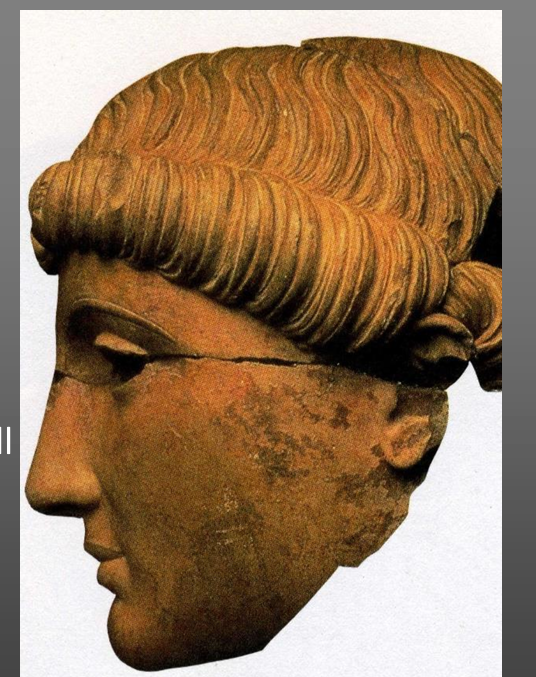

Apollo of Veii, Rome, National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia

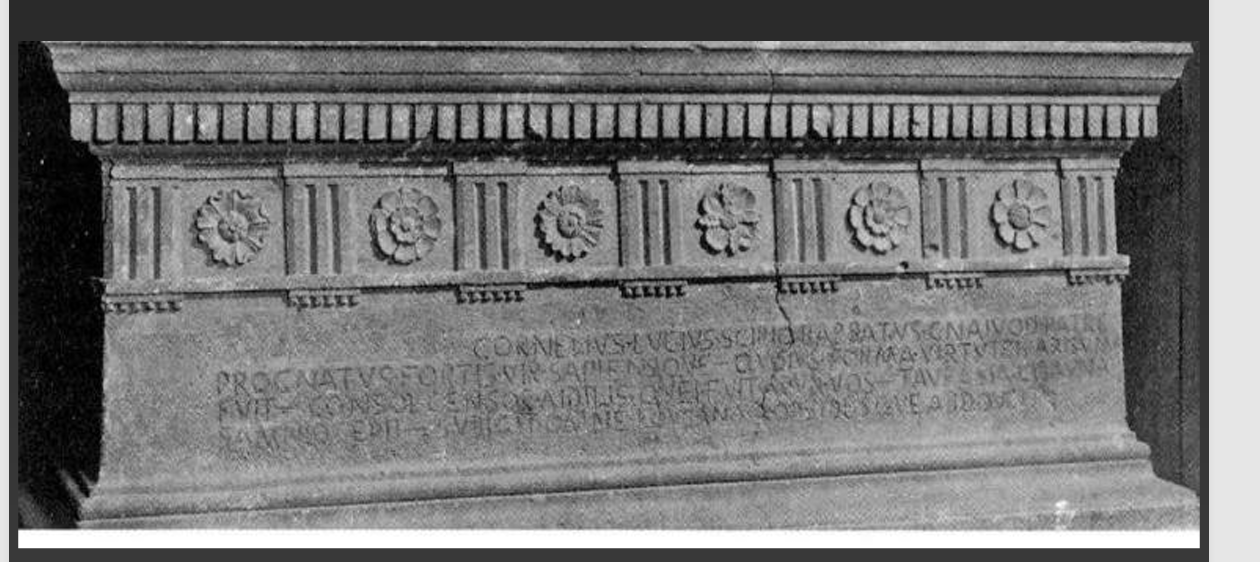

Sarcophagus of L. Scipio Barbatus, from the tomb of the Scipios, 270 BC, Città del Vaticano, Vatican Museums

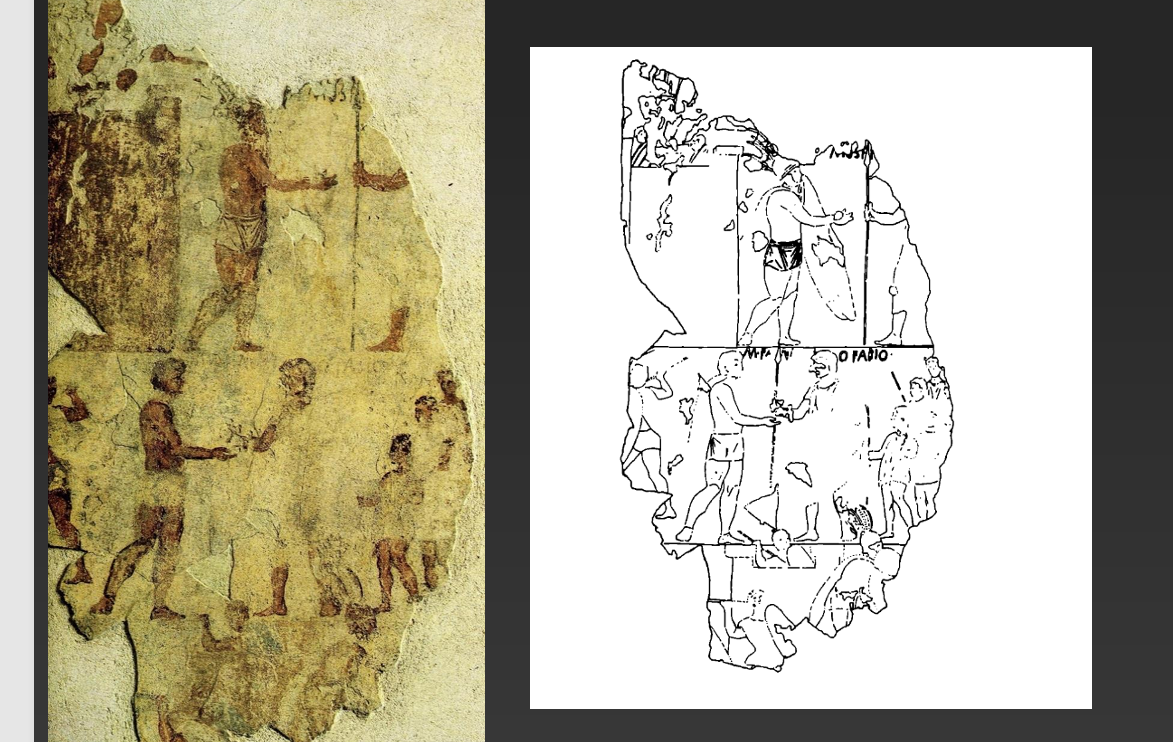

Mural painting from a tomb on the Esquiline, scenes from the Samnite wars and graphic reconstructio

Tomb of the Esquiline

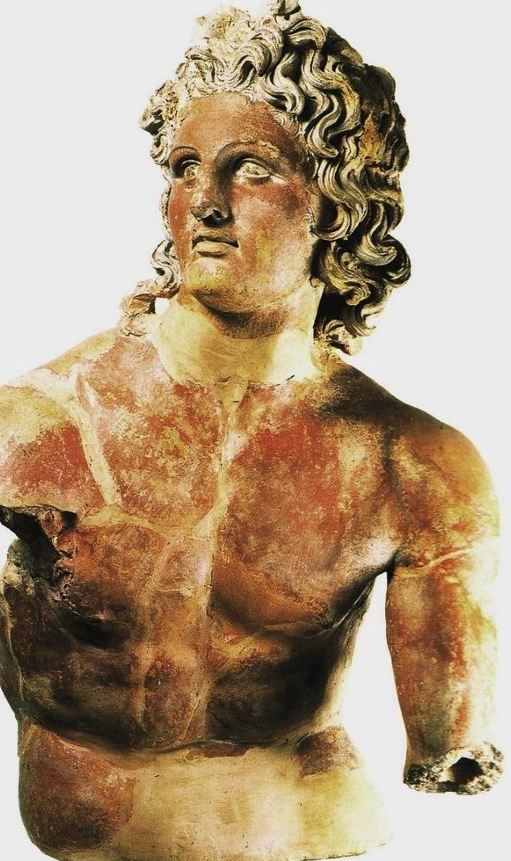

Statue of Apollo from the pediment of the temple of Scasato I, Falerii Veteres, today Civita Castellana, Rome, National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia

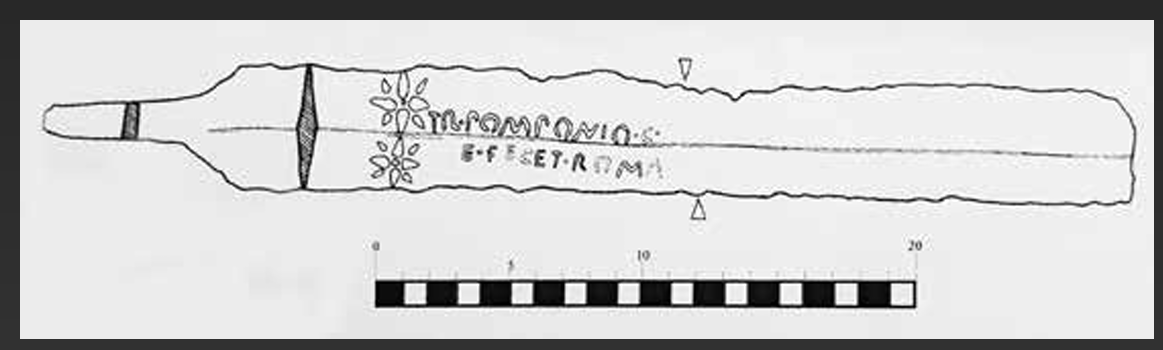

Celtic-type iron sword ageminated and inscribed Tr(ebios) Pomponio(s) C(ai) [f(ilios)] / [m]e fecet Roma[i] From San Vittore in Lazio, late IV-early III B.C.

slides talking about the relation between

etururia and rome — make sure to know key ideas communicated from the two

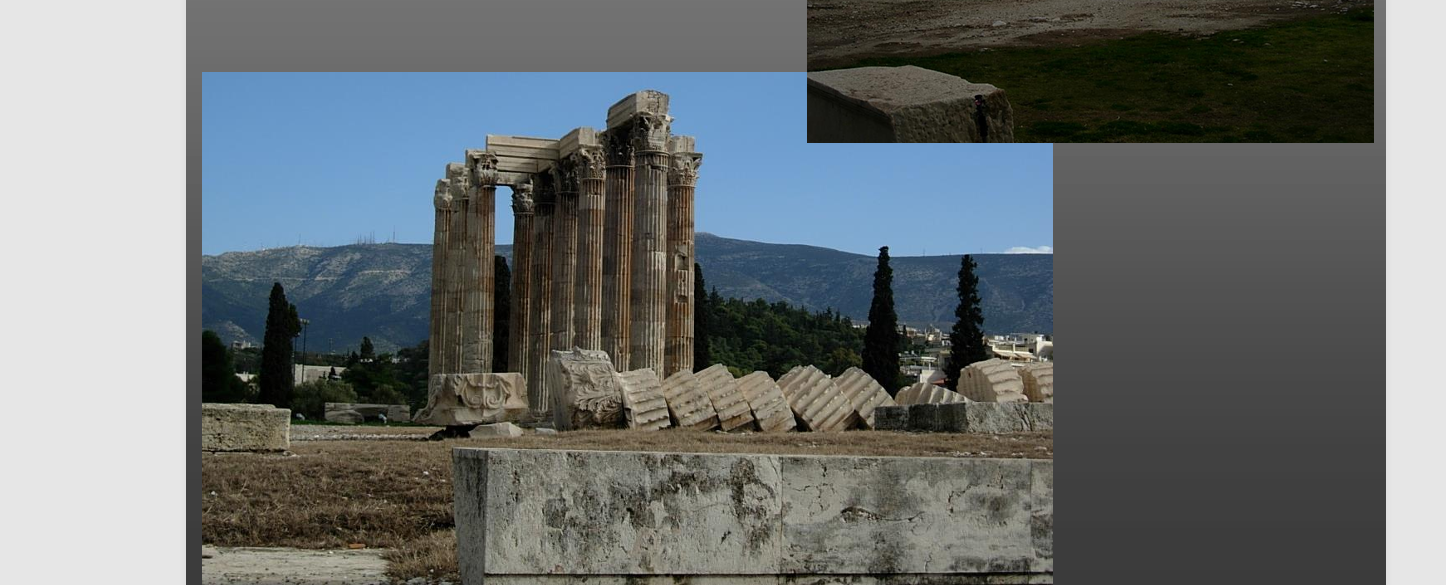

An example of mobility between Rome and Greece: the Roman Cossutius designer for Antiochus IV, king of Syria (175-164 BC) of the works at the Olympieion in Athen

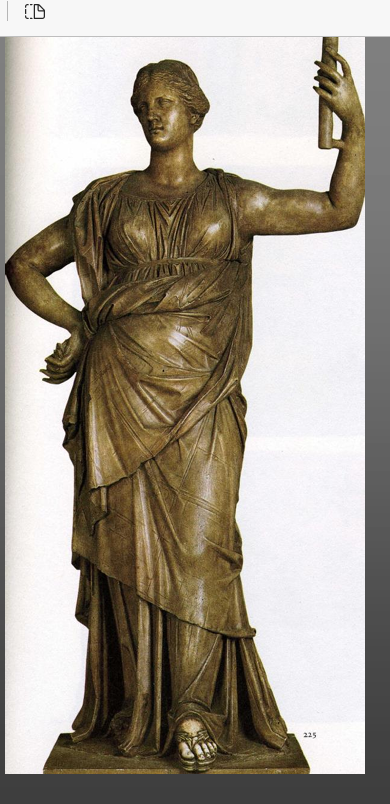

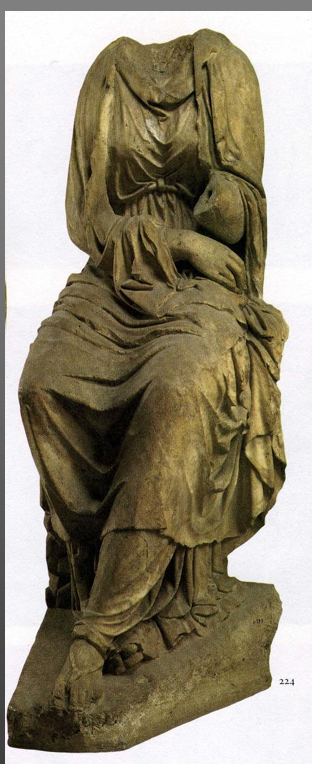

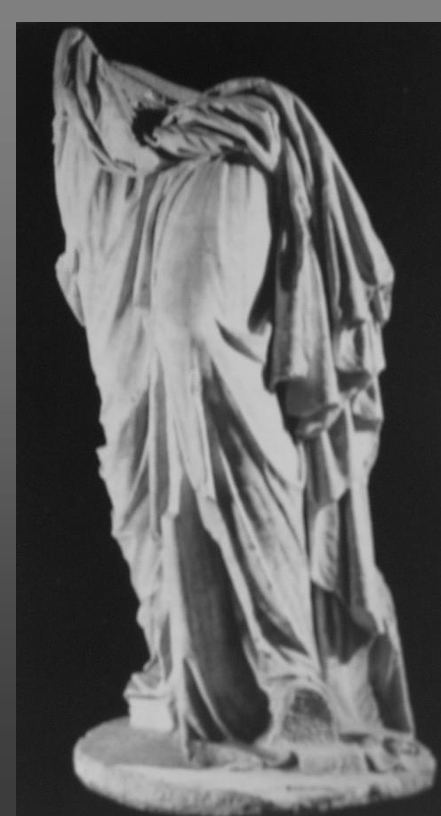

Statue of Melpomene, Paris, Musée du Louvre, from Rome, probably from the theater by Pompeius

Greek and Roman statues may share some similarities, but they also have distinct attributes that set them apart

Greek statues focused on idealized forms, divine subjects, and harmonious proportions, while Roman statues aimed for realism, individuality, and a broader range of subjects. The materials, techniques, poses, and drapery used in their creation further highlight these differences.

you should read this like 10 times over: Greek Statues vs. Roman Statues - What's the Difference? | This vs. That

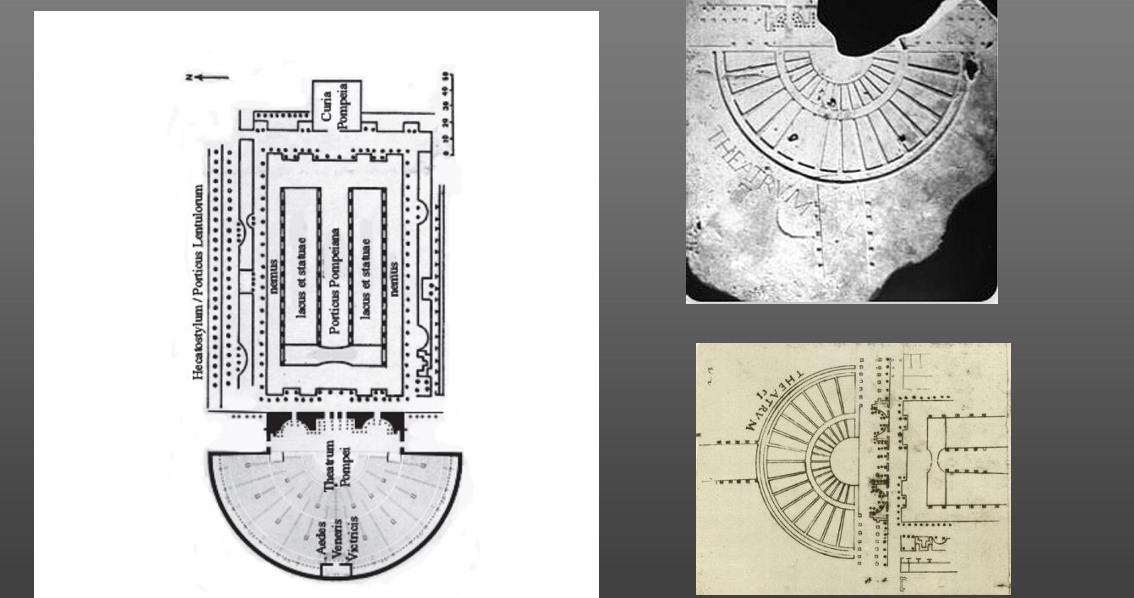

Pompeius Theatre Complex, reconstructive design; Forma Urbis, also drawn in the Codex Vatican Latin 2439

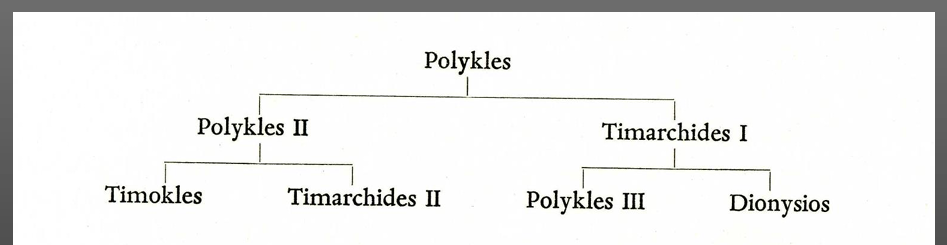

Greek sculptors whose works are attested in Rome

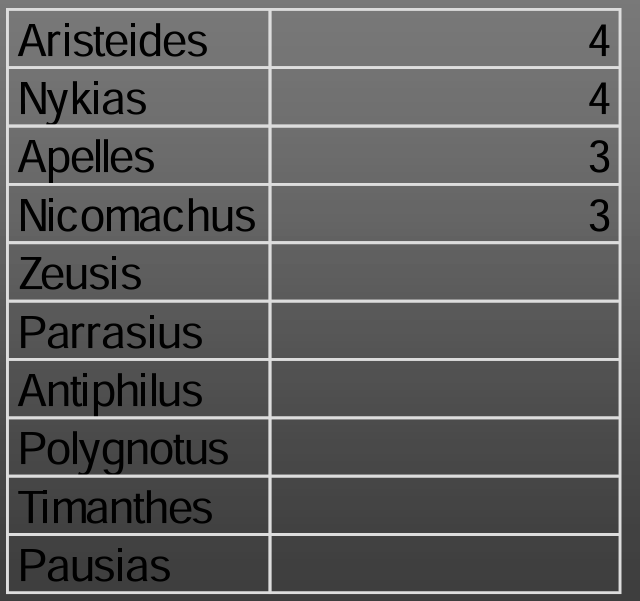

Greek painters whose works are attested in Rome

Attic School

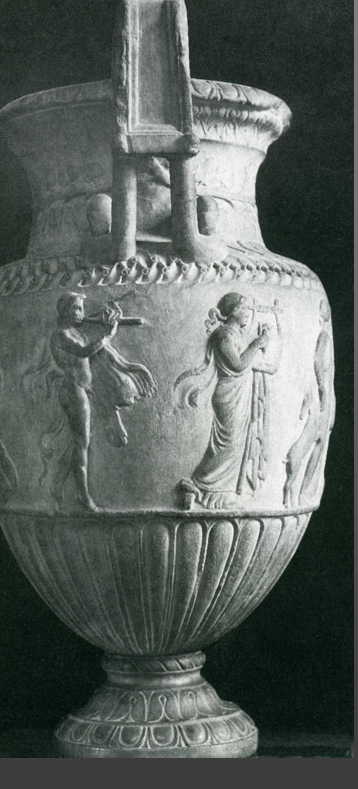

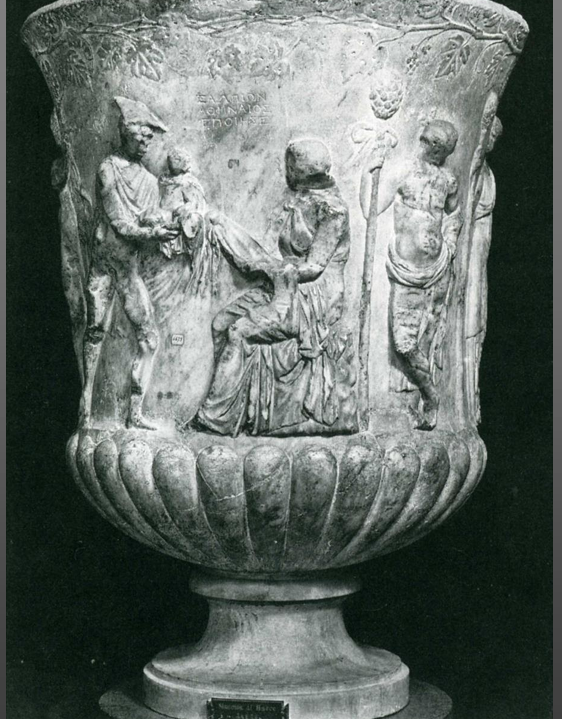

Rhytón of Pontios, Rome, Capitoline Museums — ATTIC SCHOOL

Crater signed by Salpion, Naples, National Museum — ATTIC SCHOOL

Crater signed by Sosibios, Paris, Musée du Louvre

crazy article about the differences between schools

Classical Archaeology - Fifth Period: Schools of Athens, Sicyon, Rhodes, Pergamus; New Attic School; Arcesilaus

Iuno Cesi, Rome, Capitolin Museums — ASIAN SCHOOL

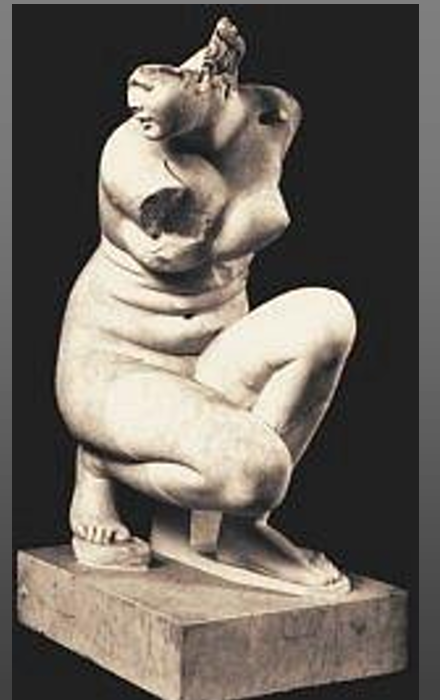

Aphrodite of Doidalsas, copy (Villa Adriana a Tivoli). Rome, National Roman Museum, Palazzo Massimo. The original was exhibited in the Porticus Octaviae —asian school

Statue of Muse, Rome, theater area of Pompey, Rome, Capitoline Museums, Centrale Montemartini -RHODES SCHOOL

«Principe ellenistico», Rome, National Roman Museum, Palazzo Massimo '—”ELCLECTIC”

Terracotta pediment from Via San Gregorio, Rome, Capitoline Museums—ECCLECTIC

Domus Tiberiana, terracotta head, perhaps eco of Arkesilaos, Rome, Antiquarium of the Palatine Hill —ECCLECTIC

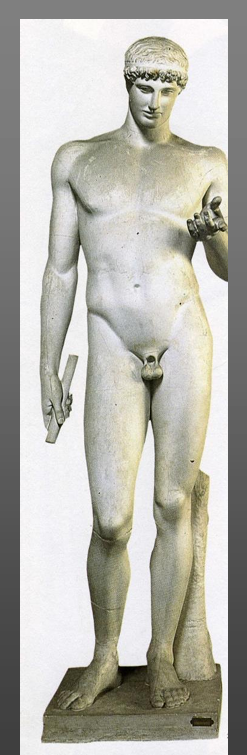

Athlete of Stephanos, student of Pasiteles, Rome, Villa Albani — ECCLECTIC

Statue signed by Kleomenes, Piacenza, Musei Civici — ECCLETIC

roman people made up all kinds of stories to

justify the location of rome

romans in the beginning were situated right between greeks and etruscans which

blurred the lines and encourage exchange between the different cultures

A new perspective in assessing the nature and legitimacy of Roman art and architecture is the view that art made in or used on the Italian peninsula (including the large category of objects created by Etruscan and Greek artists for Roman patrons) counts

basically as Roman-Italian. In a different way of telling A. Kuttner writes: “The corpus of republican art motifs from myth and religion, even when shared with a wider (Greek) world, needs to be reviewed always in Reno Metapontum Thurii Tarentum Croton Locri local sociological contexts and in the light of the accumulated visual environment that conditioned patrons and viewers” (Kuttner 2004, 303; Welch 2010.

An important aspect of Roman-Etruscan inter actions relates to the century before the formation of the Republic in 509 bce when Rome was led by

a series of kings or tyrants of Etruscan and local origin– a regal tradition that admits a century or more of monar chical rule, but not necessarily a fully established Etruscan hegemony

things we should never minimize

our self-worth

the influence of Etruscan culture over Rome, nor define it in bland notions of superiority, but see the Romans and Etruscans as parallel and intertwined societies developing within the same cultural koine

Domestic architecture in the first millennium bce immortalized by

Romulus’ legendary hut was firmly anchored in the real Iron Age settlements of central Italy.

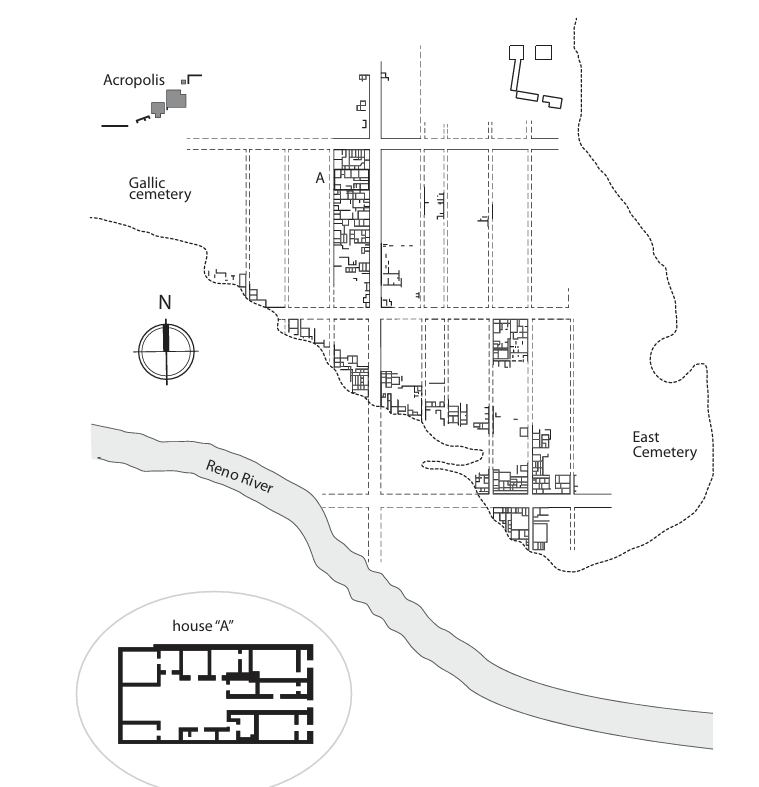

figure 1.5 Plan of Marzabotto; rendered by Güzden Varinliog ˘lu.

The interest in order and axiality may indicate growing (when referring to architecture in early rome)

Hellenic influence: Greek-inspired cities filled with Greek-inspired houses.

LINES ARE BLURRED BETWEEN GREEK AND ROMAN — NEVER

ISOLATE

Etruscan tombs of the seventh and sixth centuries dis play houselike arrangements and vestibular spaces that can be viewed as

proto-atriums

The formative role of Etruscan and central Italian traditions in the creation of the textbook

Roman temple with its deep pronaos, high podium, and frontal approach, needs no special pleading.

By the seventh century bce, evidence of sophisti cated city-making emerged:

in Etruria in central Italy, and in the southern portions of the peninsula and Sicily where Greek settlements were so numerous that the region became known as Magna Graecia (“Greater Greece”).

Greeks surveyed rectangular grids as seen at

Megara Hyblaea (c. 728 bce), Metapontum (c. 690 bce), Locri (c. 680 bce), and Poseidonia (Paestum, c. 600 bce; see Figure 1.29) in southern Italy, and at Selinus (c. 628 bce), and Agri gento (c. 580 bce) in Sicily

Etruscan Increased contact with Greek cities reverberated

in their architectural productions. Etrus can necropoli began to display aligned, uniform facades and rectangular, ashlar stonework (Cerveteri), as well as grid layouts (Orvieto). Around 600 bce, they applied a grid to a colony at Capua near Naples, oriented to the cardinal points (Figure 1.4).

Early Romans held Etrus can religious practices in

especially high regard, admir ing their ability to define ritual spaces for divination and purification.

early romans relied on

the disciplina etrusca, texts articulating the proper methods for founding cities, measuring space, dividing time and other undertakings.

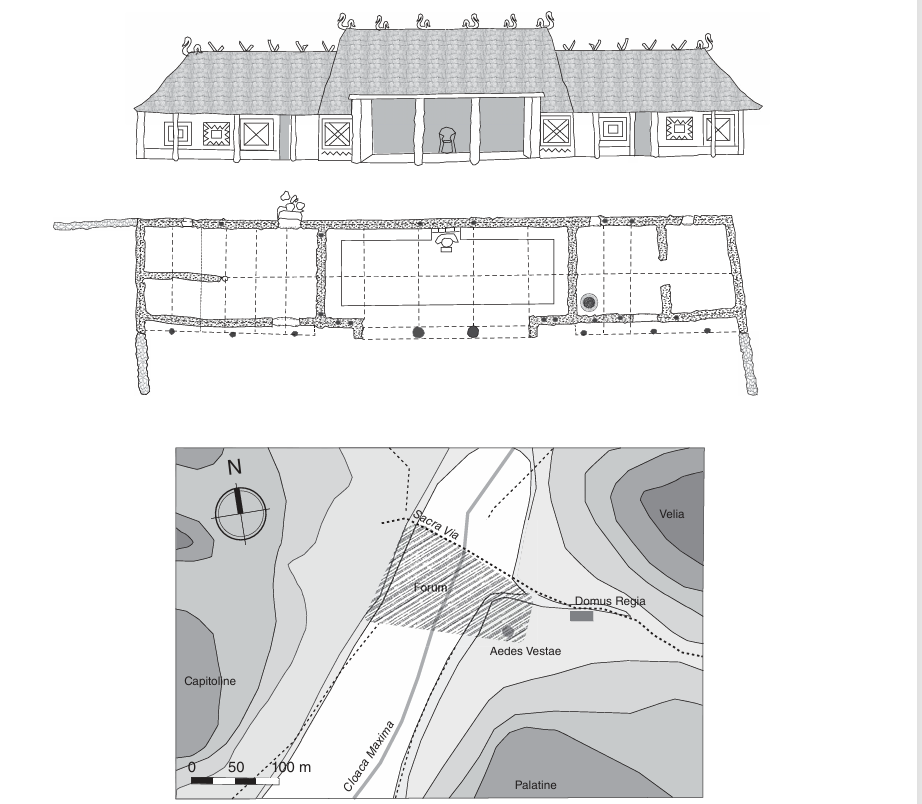

Site plan and reconstruction of Domus Regia façade, Rome; Allegedly, a king ruled the young city, and chose to reside in the Domus Regia (“Royal House”) in the central Forum (Figure 1.7). Grand aristocratic houses clustered nearby at the base of the Palatine hill. In later centuries Roman writers fabricated rich histories for the early city, identifying its founder as Romulus, the son of the war god Mars and a remote descendant of Aeneas, mythical survivor of the Trojan War

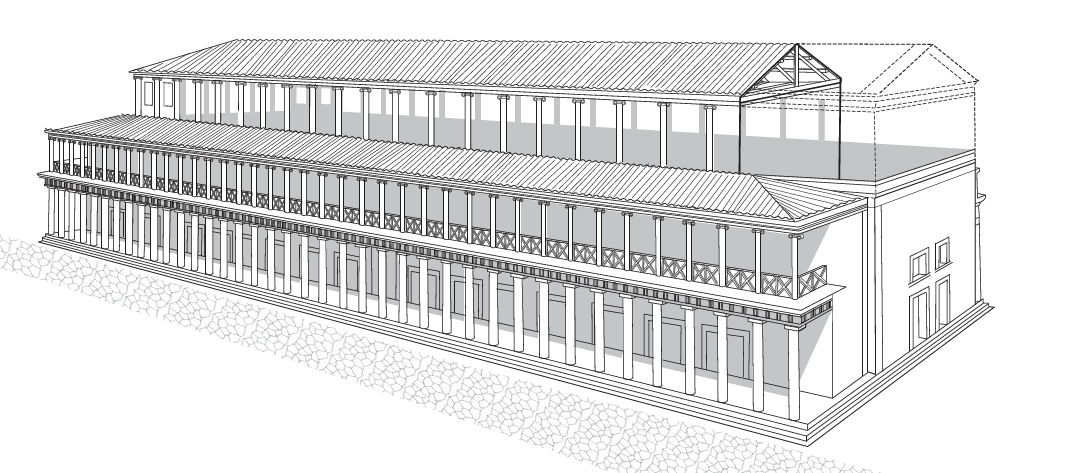

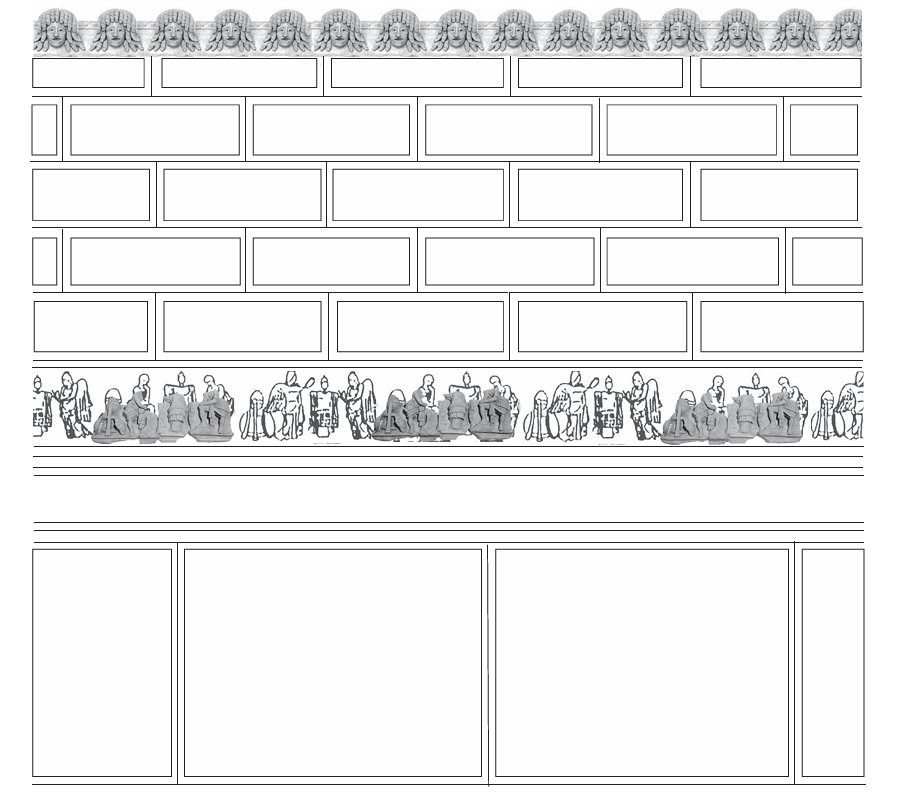

Reconstruction perspective of Basilica Fulvia/Aemilia, Forum Romanum, Rome; rendered by Diane Favro (after John Burge). have detected a development originating from local, central Italian models toward more “sophisticated” Greek-inspired ones, this process was never simple and linear; architectural inspiration comes from many different sources as architecture is a complex art involving exigencies of materials, structure as well as aesthetics. Materials bore meaning.

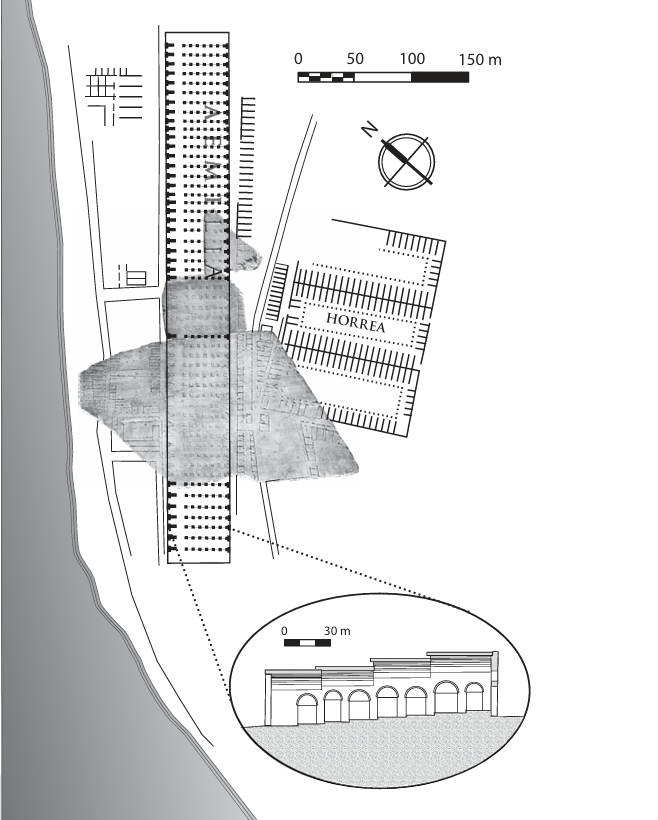

Reconstruction of Porticus Aemilia showing fragments of Forma Urbis Romae marble map of Rome; rendered by Diane Favro. One structure exploiting concrete, the so-called Porticus Aemilia, a textbook favorite, deserves special consideration. Livy informs us that in 193 bce, the aediles L. Aemilius Lepidus and L. Aemilius Paullus initiated a large market hall along the Tiber known as the Porticus Aemilia. Within two decades the censors of 174 bce rebuilt this structure creating a gigantic, half-a-kilo meter long (487 x 60 m) hall built entirely in opus caementicium (Livy 35.10.12 and 41.27.8). The building is divided into fifty vaulted rows separated by partition walls pierced by wide arches; the back side is solid except for doors and windows above, while the front facing the river some 80 meters away was originally fully open (Figure 1.13). — BASICALLY SHOW THAT CONCRETE WENT CRAY

Though rarely visible, over time concrete trans formed the cityscape — Concrete construction was essential for the massive arcaded building traditionally known as the Tabularium, or the records office, erected by the consul of 78 bce Q. Lutatis Catulus, and perhaps designed by the architect Lucius Cornelius (Figures 1.14, 1.15, and Plate 2). — General view of the Forum Romanum, Rome, looking west toward the Tabularium, which forms a backdrop for the Temple of Saturn (left), the Column of Phocas (center), the Rostra (behind the tree) and a sliver of the Arch of Septimius Severus (right); Photo by Fikret Yegül.

Interior vaulting of Tabularium gallery facing the Forum, Rome;

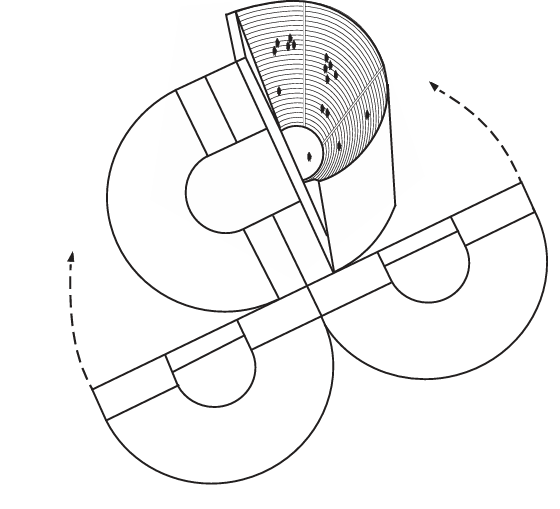

Reconstruction diagram of the rotating theater of Scribonius Curio, Rome; rendered by Diane Favro — Though temporary, these works became ever more grandiose and complex as patrons competed for atten tion. In 52 bce, C. Scribonius Curio held performances for his father’s funeral in two wooden theaters that ingeniously rotated to form an amphitheater (Pliny HN, 36.116–120) (Figure 1.16).

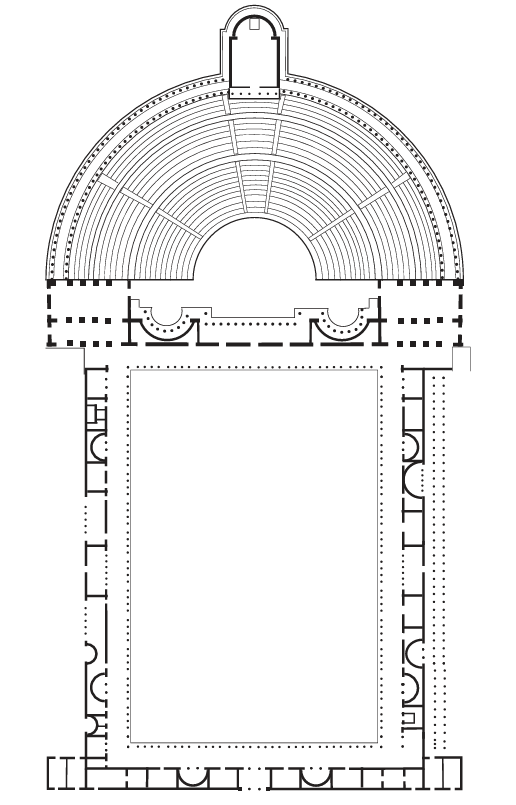

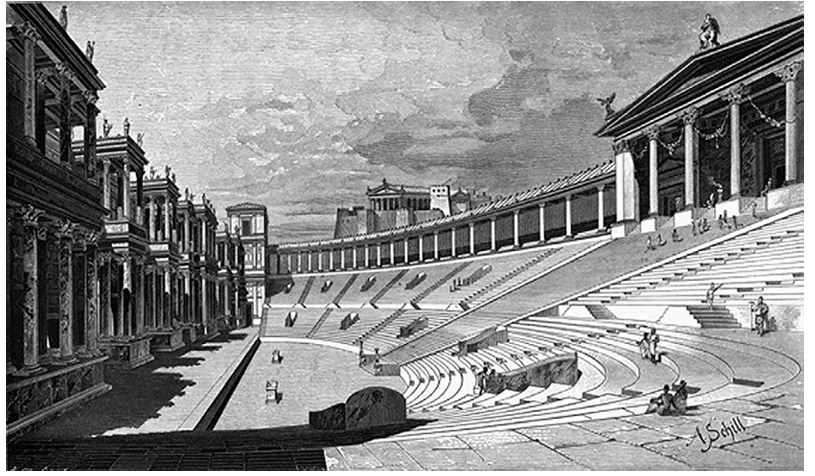

1.17 Plan of Theater of Pompey, Rome; rendered by Diane Favro (after Senseney) — n 55 bce, the general Pompey constructed a permanent, free-standing stone theater in the Campus Martius near his own house, replete with a porticoed enclosure embellished with landscaping and art. However, he took the precaution of placing a temple to Venus Victrix at the top of the freestanding curved seating (cavea) (Figures 1.17 and 1.18). Known from examples outside Rome (Tivoli, Palestrina, Pietrabbondante), such a configuration allegedly justified a stone theater by presenting the seats as “stairs” up to the shrine, a conceit abandoned after the success of Pompey’s large theater. It also overtly demonstrates the incorporation of religion and cult into secular life and architecture.

Sophisticated constructions in wood also trans f igured the city, though

their physical remains are few. Especially notable were the bridges that replaced early ferries crossing the Tiber River allowing city residents access to both the less desir able settlements on the west banks and the hinter land beyond

many roman theaters were made of

WOOD!!!

Reconstruction engraving of Theater of Pompey with Temple of Venus Victrix, Rome; Schill (1908).

Tomb of Eurysaces in front (outside) of the Porta Maggiore, Rome; Vergilius Eurysaces proudly celebrated his profession as baker with an unusual tomb at the junction of two highways entering the city from the southeast through the Porta Maggiore (Figure 1.19; see later). The tall trapezoidal structure of concrete faced with travertine is decorated with an inscription identifying his occupation for the literate and long narrative reliefs depicting the produc tion of bread for those unable to read.

Since burials were not allowed within the pomerium, another concentration of structures promoting individ uals and families occurred on the

well-traveled highways leading in to Rome. Every Roman of means sought eternal recognition — hence weird bread tomb

The pomerium was a

sacred boundary around the city of Rome and cities controlled by Rome. It was a strip of land located both outside and inside the city walls, and marked Rome's borders. In legal terms, Rome existed only within its pomerium; everything beyond it was simply territory belonging to Rome.

Walls and gate of Falerii Novi , Beyond providing protection and clear boundaries, city walls conveyed strength and projected dignity. When the Romans relocated all the occupants of Falerii Novi after a revolt in 241 bce, they provided the new city of their defeated foes with attractive and strong, stone walls and arched gates as markers of civic identity — WALLS WERE THE THING! as they expanded in the fourth century bce, the Romans’ first response was to create “a wall.” so usa core lmfao

how was the dominion of the roman empire

from class idek rome as capital and the

punic wars

sardinia and corsica

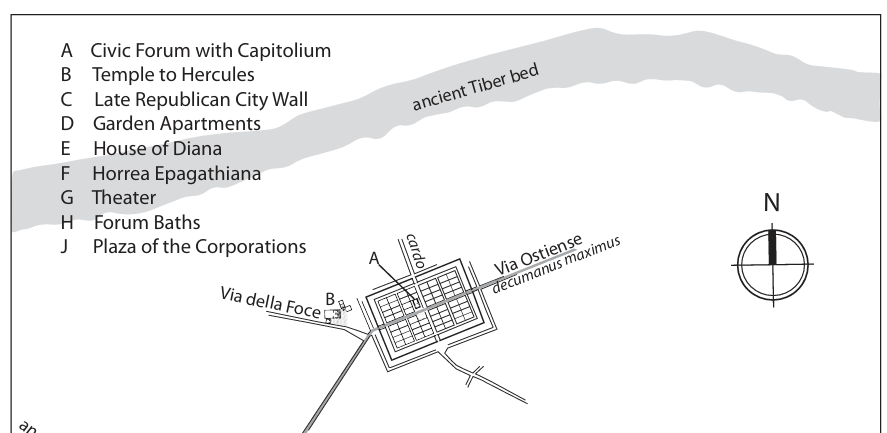

OSTIA

Rome created an early gridded castrum close to home to protect access to the sea and the coastal salt beds near the mouth (ostium in Latin) of the Tiber River. Known today as Ostia Antica, the camp stood a mere 25 kilo meters from Rome, on flat land easily reached by river barges and a highway, the Via Ostiensis, which ran through the center of the new plan (Figure 1.23, top).

Ostia Castrum, 2 century

Onehundredandfortykilometersnorthofthecapital city, theRomansestablishedtheLatincolonyofCosa in 273 bce, possibly on land confiscated from the Etruscans

Cosa

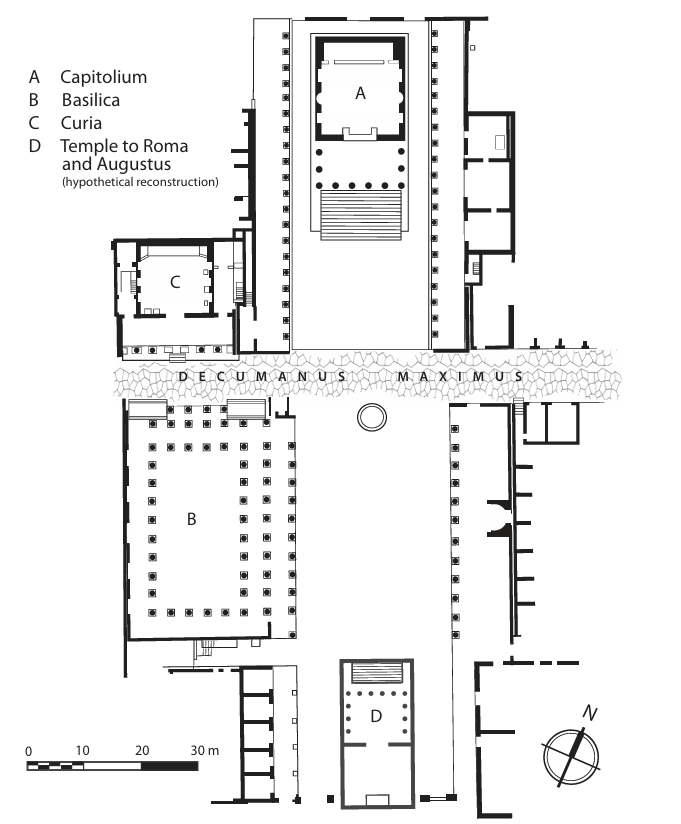

Cosa a dominant position in Roman architecture. With its circuit walls and gates, blocks of houses, early bath, and small forum accommodating a basilica, comitium, curia, temples and arch– all dom inated by a sacred hill or citadel (the Arx) with Italic style temples– Cosa is a textbook example of a modest, but well thought-out Roman town.

Detail of interior wall decoration with terracotta reliefs, Domus 2 at Fregellae; rendered by Diane Favro

Fregellae stands as a

model of amore advancedand prosperous inlandLatin colony directly on theVia Latina, circa 95 kilometers sout

archaic Pompeii was

“still a settlement with wide open, undeveloped spaces with occasional wooden structures and some soft lava masonry buildings”

There were two monumental exceptions to this bucolic pic ture of archaic Pompeii:

he Temple of Apollo, a large peripheral temple of the Greek type next to the market place (later forum); and the Doric temple (c. 530 bce) located southeast of the settlement on a separate high, narrow terrace, which was later called the Triangular Forum, really a sanctuary (Figure 1.36)

SAMNITE PERIOD

The next long stage in Pompeii’s urban history roughly covering the period from the fourth through the second centuries bce is also one that stamped the city with a distinct architectural color and character. But, oddly, it is also the most vague, with open questions about the chronology, development, and interpretation of its architecture. Traditionally referred to as the Samnite Period, (and vaguely paralleled by wars between the Republic and the Samnite tribes for the control of central Italy; see earlier), it is represented by important but incremental changes in the shaping of the city and its public image, rather than by distinct architectural advances propelled by grand notions of Greek city planning.

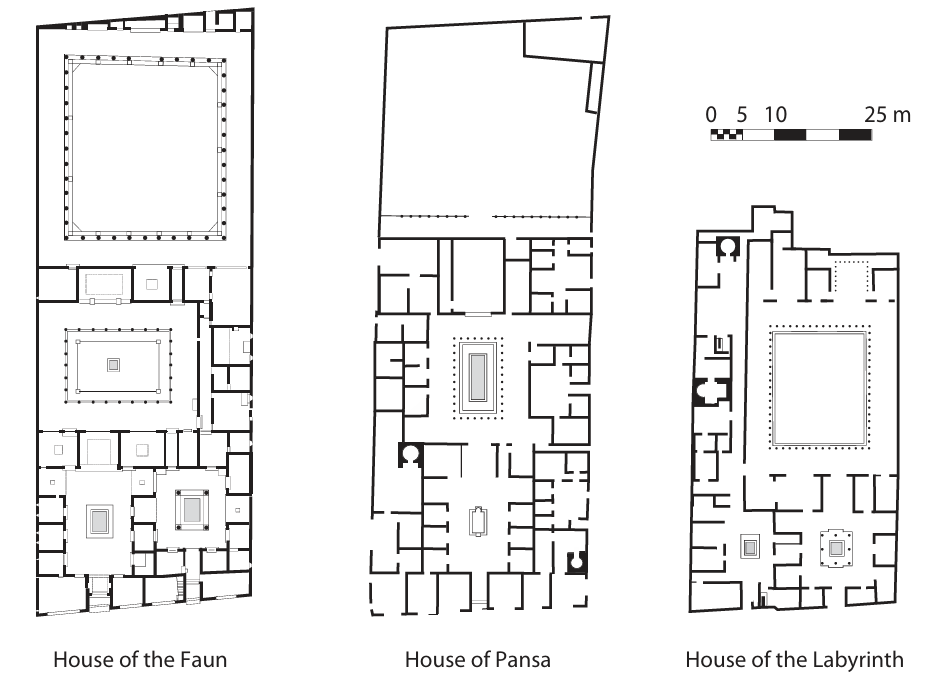

f igure 1.39 Plans of the House of the Faun (VI.12); House of Pansa (VI.6.1); House of the Labyrinth at Pompeii (VI.11.10); rendered by Diane Favro

pompeii samnite period: Some of the largest andwealthiest residences, such as

House of the Faun and theHouse of Pansa, are located in the new, regularly laid out neighborhoodnorthof the“oldsettlement”(south west quadrant).These large tufa houseswith their lofty atriums in the old, austereTuscan style and strongaxial layoutsduly impress (Figure 1.39).The sobereleganceoftheirstreetfacades, imposingdoor ways, lightenedbyfinely-cut,discreetornamentation bearwitness toPompeii’sdeeproots inits indigen ousSamnite/Oscanpast

THE SULLAN COLONY

The size, design, and details of Pompeii’s basilica reveal aprovincial senseof classicismand formalism appropriateforthepremieradministrativeandjudicial buildingofanewlyminted“Roman”city, whichwas probably anxious to take its official duties with self conscious seriousness.

POMPEIAN BATHS

Pompeii stands at the source and crossroads of another quintessentially Roman recreational (and hygienic) institution– the public baths, or balneae.

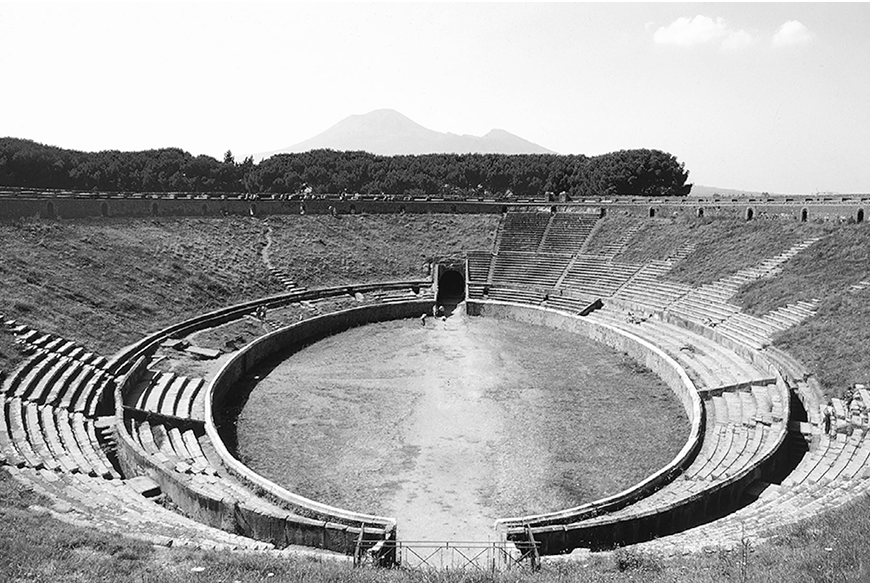

Exterior view of the amphitheater with stairs, Pompei

General view of interior of the amphitheater, Pompeii, with Vesuvius in the distance

AUGUSTAN AND JULIO-CLAUDIAN POMPEII

In one sense, the Augustan architectural and urbanistic achievements in Pompeii were a natural continuation of the work started during the Sullan period; both shared the same goals and served the same physical and symbolic needs of the new colony. In another sense, they brought fresh vision and impetus in expanding the ideas and projects that underscored the ideologies of the empire.

go back and do like all pompeiian structures

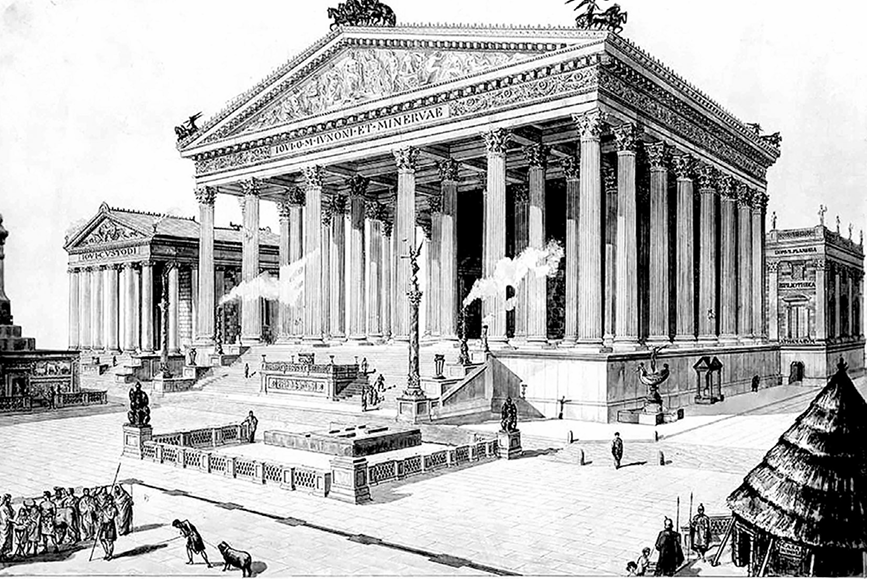

THE TEMPLE OF JUPITER CAPITOLINUS

Dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno, and Minerva, the traditional triad of deities who protected the Roman state, the temple stood at the end point of the long triumphal procession in which victorious generals or emperors sacrificed and dedicated the spoils of their campaigns. In addition to these triumphs, the temple was the starting and ending point for many religious processions, celebrations, and games, as well as military campaigns.

Historical reconstruction of the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, Rome, by G. Gatteschi (1909); American Academy in Rome– Photographic Archive (Gatteschi collection 4). — the exterior appearance of the original Capitoline Temple– its tall podium, frontal steps, deep porch, very widely spaced columns, and broad profile– resulted in an image distinctly different from the Greek (or classical) standards of temple architec ture. These features came to symbolize Italic or Tuscan characteristics and were seen as based on local traditions and qualities in the eyes of Republican leaders who sought to preserve the old manners and customs as moral imperatives.

the Capitoline Temple was a monument and was monumental, not just for

its large size and dramatic setting that enhanced the size but also for its symbolic meaning for Romans as the abode of the immortal gods who protected and legitim ized their state, empowered its leaders and citizens, and projected this grandeur and sanctity into the future. We also can see that the Capitoline Temple began its life as an Etruscan building, but as an icon it became quintes sentially Roman.

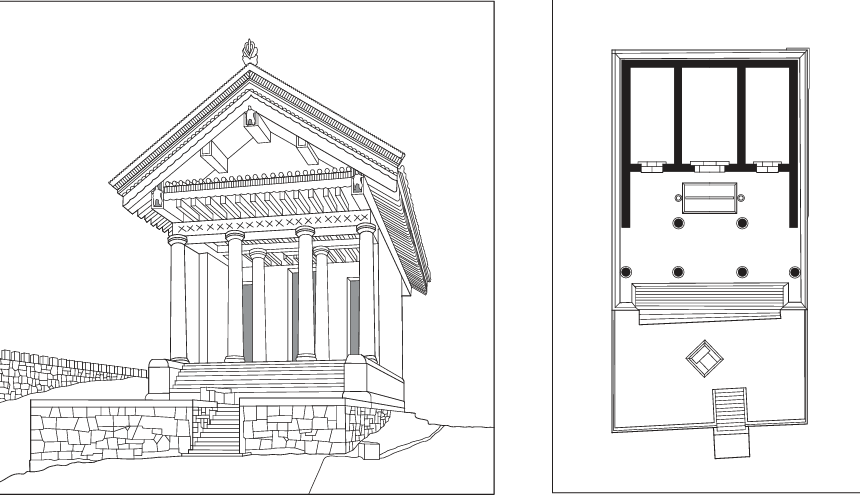

CAPITOLIUM OF COSA

gives us a good idea of a fairly conserva tive mid-second-century bce Italic temple outside Rome, exhibiting the traditional arrangement and pro portions recommended by Vitruvius 150 years later.

Reconstruction perspective and plan of the Capitoline Temple on the Arx at Cosa

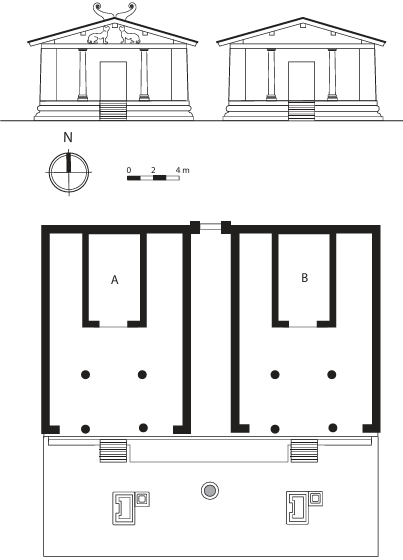

THE TEMPLES OF THE AREA SACRA OF ST. OMOBONO

Situated in busy market places, many of these temples and the cults that they represented were not associated with arcane and distant religious liturgies but with the everyday life, hopes, aspirations, and prejudices of ordin ary Romans. — Dedicated to the nurturing and protecting deities of Mater Matuta (east) and Fortuna (west), these large temples (cellas 20 29 meters [70 100 RF]) were built in cappellac cio and pepperino tufas from local sources. Although following the basic Etrusco-Roman configuration, their plans are unusual in having long side walls (like extended alae) framing the single cellas with two columns in antis

Plan and elevation of the Republican temples in the St. Omobono sacred area (Mater Matuta, left; Fortuna, right), Rome; rendered by Diane Favro (after Stamper)

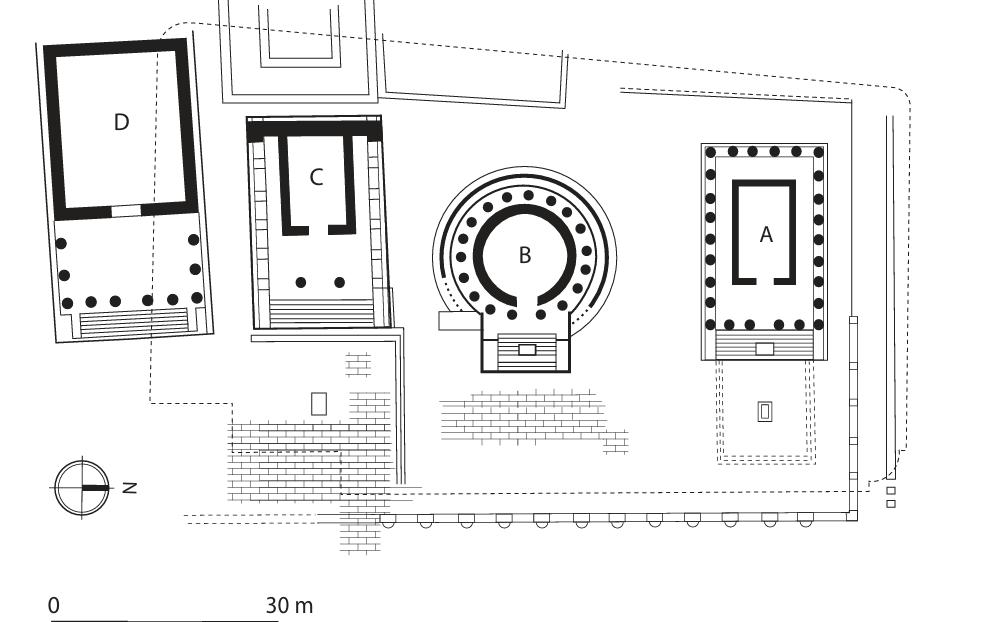

LARGO ARGENTINA TEMPLES AND THE TEMPLE OF JUPITER STATOR

group of four small Republican temples in the Largo di Torre Argentina (aka Largo Argentina), a sacred precinct in the southern CampusMartius. Neatly aligned in a row facing an open area to the east, all of these temples show distinct Italic characteristics: high podiums, deep porches, and frontal approaches with steps — This arrangement, fairly common among Republican temples, is the Tuscan type described by Vitruvius as ambulatio sine postico (“a portico without a rear portion,” 3.2.3). One well-known example is the original phase of the temple of Jupiter Stator (in a colonnaded enclosure known as the Porticus Metelli, but later the Porticus Octaviae) founded in 146 bce, and reported to be the f irst temple in Rome to be built entirely of marble (Figure 2.9).

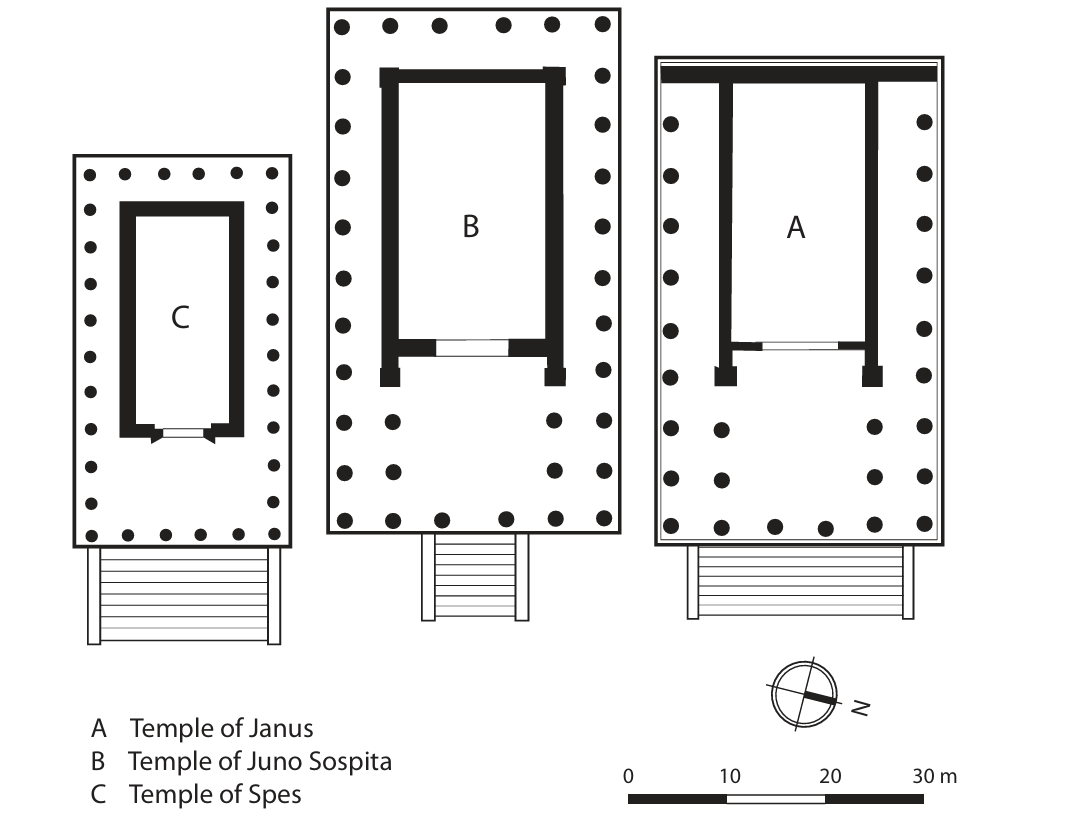

THE TEMPLES OF THE FORUM HOLITARIUM

The three temples of Forum Holitorium, nominally Rome’s vegetable market, were located on the flat land immediately east of the Theater of Marcellus — Their restored plan with very tight spacing and pre cise front alignment is striking (Figure 2.10). The historyof this area sacra dates to the early or mid third century bce.

General view of the temples in the Sacred Precinct of Largo Argentina, Rome, looking south; — All three temples display late Republican characteristics with Tuscan plans and varying degrees of Greek influence. —Across from the three temples the east side of the sacred precinct was defined by what appears to be a “late republican-era market arcade” of engaged Tuscan columns alternating with arches, “a motif that prefigured the Colosseum and related to the (façade of the) ‘Tabularium’”

FORUM BOARIUM TEMPLES IN ROME AND THE TEMPLE OF VESTA AT TIVOLI

Plan of the Sacred Precinct of Largo Argentina,Rome (TemplesA,B,C,andD);renderedbyDianeFavro(afterTorelli).

0 Planof theTemples of Janus, JunoSospita, andSpes at the ForumHolitorium, Rome; renderedbyRuiXiong (afterStamper)

THE HELLENIZATION OF ROMAN TEMPLES

Hellenistic influences on the Tuscan temple were manifested mainly by the acceptance of the classical orders and classical proportions: Greek columns, capitals, and ornament in stone instead of the low and strongly projecting wooden gables displaying archaizing ornament in terracotta. The tall, vertical proportions of these classically inspired temples set them apart from their old-fashioned counterparts perceived to be Tuscan

hellenization and republican conservatism

though these temples were being rebuilt the italic features were still proudly displayed

Even in the choice and application of the classical orders there were moments of indecision and awk wardness.

Tempio della Pace or Italic temple, circa 100 bce, in the forum of Paestum (Posedonia, an ancient Greek colony) is instructive in its

creative unorthodoxy — The temple’s south-facing single cella rises on a high podium, alae with lateral columns, a tetrastyle porch and frontal steps follow the Tuscan model that would not have been unfamiliar to Vitruvius (Figure 2.19; see Figure 1.30), though being conservative, he might have approved neither of the complex and scenic arrange ment of the frontal steps with multiple landings incorporating the temple altar, nor the complexity introduced in the creative use of the orders. The upper structure of the Paestum temple displays a combin ation of a Doric entablature with unusual capitals, which mix Corinthian leafage below with Ionic inspired volutes flanking sculptured heads above. The juxtaposition of an Italic plan with Hellenic ornament may reflect the hybrid tastes of a Greek colony turned into a Roman municipium. As in Pompeii, such cavalier experimentation with the classical orders– with very unclassical results– may be refreshing, and affirms the amount of freedom that was available to the Hellen ized Republican architect. It also shows, of course, that this freedom could result in ambiguous choices.

The temple architecture of the Republic did not develop along a simple straight line from Etruscan to Greek; rather

it followed a widely available variety of models and motifs developed from native central Italian, Etruscan, and Greek sources. It moved forth, looked back, took an unexpected leap forward, and sometimes, etc

While the influence of Greek and Hellenistic sources (and Hellenized Italic solutions) may be said to dominate toward the end of the Republic, the

overall architectural culture of Rome and Italy encouraged broadly based borrowing and blending of motifs.

A codified and canonical acceptance of classicism, Roman style, did not occur until

the early days of the Imperial era.

Among the most remarkable architectural achievements of the late Republic one could isolate three D sanctuaries in Latium constructed within less than a century (c. 120–50 bce)

TEMPLE OFJUPITER ANXUR, TERRACINA

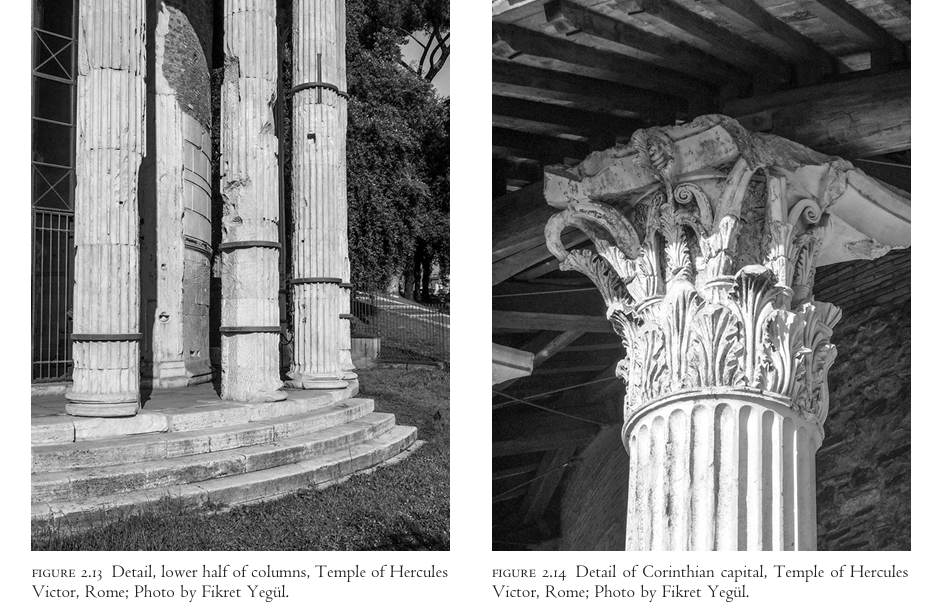

TEMPLE OF HERCULES VICTOR, TIVOLI

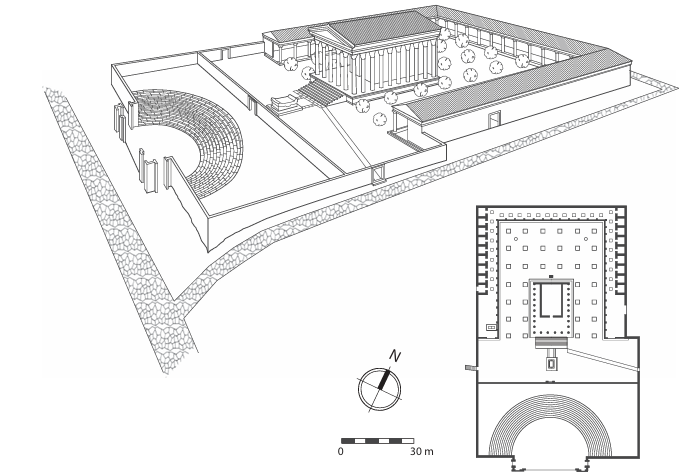

SANCTUARY OF FORTUNA AT PRAENESTE PALESTRINa — In all of these three sanctuaries– Terracina, Tibur, Praeneste– design was determined by the disciplined, purposeful human movement through space

Restored perspective and plan of the Sanctuary of Juno at Gabii; rendered by Diane Favro

most striking temple amphitheater design

SANCTUARY OF FORTUNA AT PRAENESTE PALESTRINA

why is the SANCTUARY OF FORTUNA AT PRAENESTE PALESTRINA impressive?

i have no idea but i guess it uses a lot of vantage points and drama and complements the surrounding area — “The unknown architect-genius who planned Palestrina probably knew the Greek sanctuary at Kos; he was certainly intouchwiththemainmovementofmindin his age. But the final impression of this dynamic, utterly functional, axially symmetric complex is not Greek but Roman,”