W5 Internality Public Goods

1/40

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Internalities and Public Goods

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

41 Terms

What is an internality?

When an individual does not fully internalize the effect of their actions on their own welfare—i.e., they make mistakes.

How are internalities similar to externalities?

Both involve misalignment between private and social welfare; internalities are “self-imposed externalities.”

What does the demand curve represent in presence of internalities? What about the supply curve?

Demand curve captures perceived PMB, but could be different from true PMB if “consumption internality”

Supply curve captures perceived PMC, but could be different from true PMC if “production internality”

What is the 'Average Marginal Internality'?

The difference between perceived and true PMB.

What are common behavioural biases leading to internalities?

Procrastination / self-control issues

Myopia (short-sightedness)

Overconfidence

Heuristics (mental shortcuts or simple rules people use to make decisions or solve problems quickly and efficiently)

Misunderstanding probabilities or compound interest

What are the 3 steps in correcting internalities?

Is there an internality? - some behaviours may be rational, so government intervention equals paternalism.

If mistakes come from lack of information:

Provide better information (learning) and let people choose (e.g., food labelling).

If learning cost or mistake cost is high, regulate product directly (e.g., medical drugs).

Otherwise, use price or quantity policies as with externalities:

If marginal “damage” is steep → quantity restrictions best.

If marginal “damage” is flat → price policies best.

Why is it important to understand the reason behind an internality, and how does it affect policy choice?

If people undervalue future consequences but still respond to prices, taxes (like sin taxes on smoking, alcohol, sugary drinks) can help correct behaviour.

If people switch between a rational self and an irrational self, sin taxes (tax on smoking etc) may be ineffective. The optimal policy then is to restrict access for the irrational self, e.g., delaying gun purchases or restricting late-night alcohol sales.

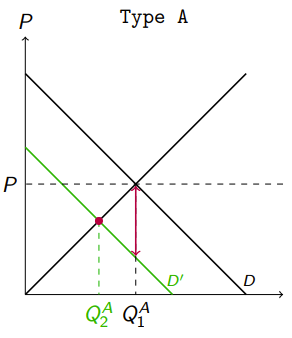

Why is it important to consider heterogeneity among people when designing policies like sin taxes or quantity restrictions?

Because some people may be making mistakes while others are not.

Ideally, only those making mistakes should have their behaviour changed to maximize social efficiency.

Uniform policies like sin taxes can increase total surplus but may unfairly hurt rational consumers.

More targeted measures (e.g., banning cigarette sales to minors, restricting alcohol sales at night) can better discriminate between groups and minimise harm to rational buyers.

What does a consumption internality look like?

What did Madrian & Shea (2001) find? What are the implications of this?

Automatic enrolment into retirement plans significantly boosts participation and leads to clustering at default rates.

Implication: Default rules (nudges) can correct for self-control/internality problems better than incentives alone.

What is a public good?

A good that is non-rival (one’s use doesn’t diminish another’s) and non-excludable (can't prevent use).

Whats the key issue with public goods?

Private markets will under-provide public goods

Positive externalities (so underprovided) from paying for the public good since its non rival and one person’s use doesn’t reduce someone else’s

Also free rider problem (everyone benefits even if they don’t pay) as public goods are non-excludable

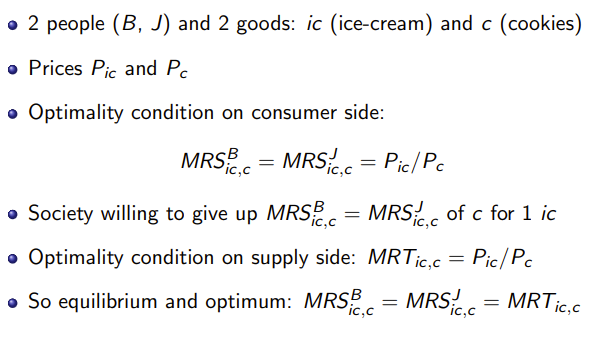

What is the optimal provision of private goods?

Essentially MRS=price ratio for consumers and MRT=price ratio for firms and then MRS=MRT

How do we find the social demand curve?

Horizontal summation - add up quantity at each price and sum horizontally

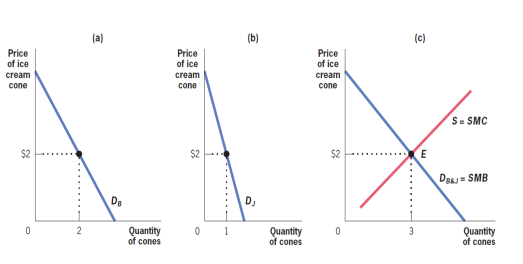

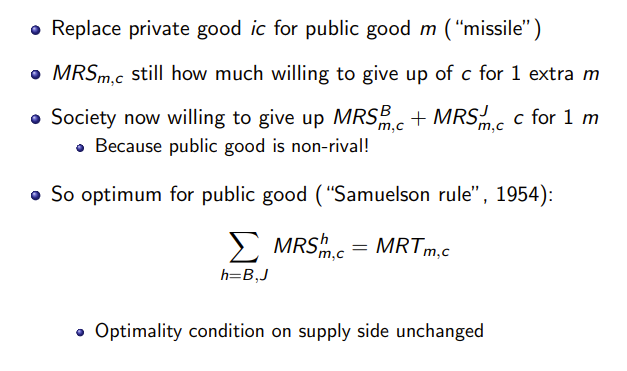

What is the optimal provision of public goods?

Public good is non-rival, so society's willingness to pay is sum of individuals' valuations

What is the Samuelson rule?

Sum of MRS = MRT is optimum for public good

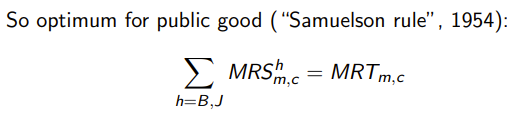

What is the difference in finding the social demand curve in the public and private goods market?

Public goods - vertical summation (p changes) - in pic

Private goods - horizontal summation (q changes)

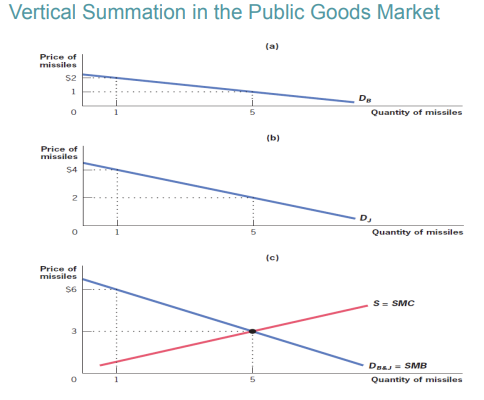

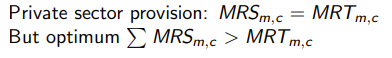

How do we show under provision of public good in terms of MRS and MRT?

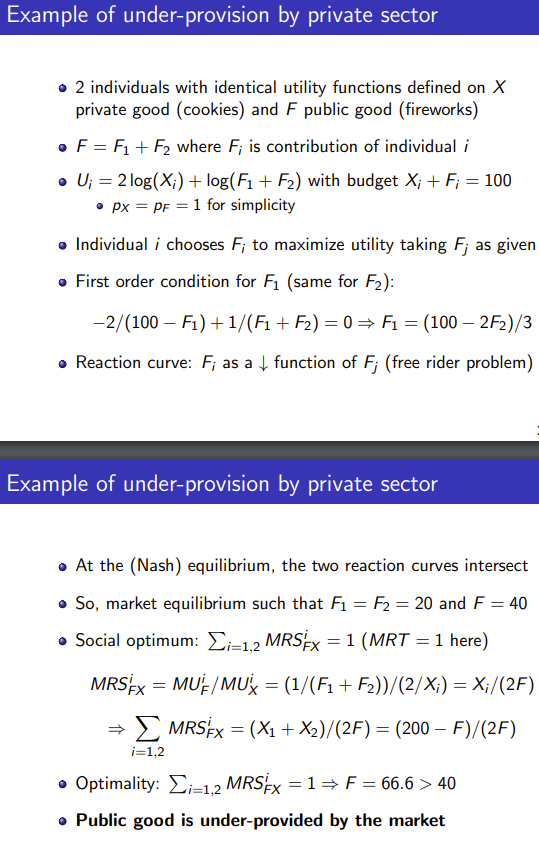

How do we show under provision of public goods mathematically?

Individuals maximise Fi (their contribution towards the public good)

This gives us a FOC that is downward sloping and negatively related to the other person’s contribution (i.e. if they contribute more, you contribute less)

Each person tries to benefit from the other's contribution without paying more themselves which leads to under provision

The reaction curves intersect at equilibrium and give the sum of MRS=MRT where MRT=1 in this case

Rearranging for F at the optimality point gives us F=66.6 which is less than the private provision so it is underprovided

What are factors mitigating the free rider problem?

Some individuals care more about the public good than others (they will contribute regardless of other people’s contribution)

Some individuals are altruistic (value the well-being to others so they consider the benefits to others when contributing - they internalise the externality)

Some individuals derive utility from their own contribution level itself, not just total amount of public good (basically get satisfaction by just contributing)

What does the paper by Marwell and Ames (1981) look at? What do they find?

They investigated a laboratory experiment (called public good game) with 5 players and 10 rounds and each round, each person allocates 10 tokens between private use (keep token and get £1) or public good (give token and everyone gets £0.50 so total to everyone £2.50).

Nash equilibrium is keep all tokens and contribute nothing (selfish)

Social optimum is to contribute all tokens

Results: people contribute around 50% to the public good BUT contributions tend to fall as game repeated. People are willing to cooperate but get upset and retaliate if others take advantage of them

What tools can the government use to overcome the free-rider problem?

Same as positive externalities:

Price policies - subsidise private contributions (e.g. charitable donations)

Quantity policies - government could provide public goods directly or mandate their provision but this risks crowding out private contributions (reduces contributions)

What does the example of Business Improvement Districts show?

How we can have Coasian solutions with some help from the government:

Local businesses agree collectively to fund services (e.g., extra street cleaning, safety patrols).

Requires a majority vote, and once passed, a levy (tax) is imposed on all businesses.

This prevents free-riding by making contributions mandatory.

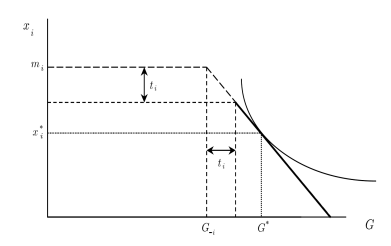

How do we show complete crowding out when there are forced contributions (like a lump sum tax)?

What are the factors reducing crowding out of private contributions?

Forced contributions will start to have an effect when private contributions drop to 0 (no more crowding-out possible)!

Crowding-out smaller when individuals derive some utility from contributing

What are the two sources of empirical evidence on crowding out of private contributions

Laboratory experiments

Empirical evidence from real world

What do laboratory experiments show about crowding out of private contributions?

They show some crowd-out, but less than 1-to-1.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using laboratory experiments as evidence on crowding out of private contributions?

Advantage: better control of the context

Disadvantages: low stakes, fail to capture some motives for giving (warm glow, prestige, social pressure to contribute)

What is the empirical evidence from the real world on crowding out of private contributions?

Evidence from charity giving - a form of private provision to public goods

65% of UK population contributed to charity in 2018 (high compared to European standards)

What does the paper by Andreoni and Payne (2003) look at?

They investigate whether government funding/grants "crowds out" private donations, and how much of this effect happens through reduced fundraising efforts by charities.

The crowding out can happen through two channels: willingness to donate + fundraising

Why are charities described as “active” agents and donors/individuals as “passive” in the context of fundraising?

Because a reduction in government support leads charities to reduce fundraising, which then lowers donations. Donors/individuals typically respond to solicitation rather than acting independently.

What was the key finding of Andreoni and Payne (2003) on government grants and private donations?

A $1 increase in government grants led to a $0.56 decrease in private contributions, with 70% of that reduction due to less fundraising by charities.

What is reverse crowd-out in public good provision?

When increased private contributions lead to a reduction in government/public provision.

How does reverse crowd-out apply to foreign aid?

When a foreign government gives targeted aid to a country, the receiving government might reduce their own contributions or reallocate funds elsewhere

What are the 2 challenges in implementing the Samuelson Rule for public goods?

Measuring individual preferences (MRS) is difficult due to externalities and strategic behaviour.

Samuelson rule must be adjusted for distortionary taxation (if government cannot fund public good by lump-sum tax)

What are the three main problems in measuring preferences for public goods?

Preference revelation – People may lie about their valuation to avoid paying more.

Preference knowledge – People may not know how much they value the good.

Preference aggregation – It's hard to combine millions of individual preferences into a social decision.

What is the Condorcet Paradox in majority voting?

Majority voting may lead to inconsistent group preferences, where preferences cycle and there's no clear winner.

What are the two main limitations with majority voting?

Condorcet Paradox - Majority voting may not produce consistent aggregation of preferences (general problem with aggregation as in Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem)

Majority voting will not capture intensity of preferences, only the number of people supporting an option

What does Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem state?

No voting system can perfectly aggregate individual preferences into a consistent social preference without violating some fairness criteria.

How are peaked preferences important for the context of majority voting?

When everyone has single-peaked preferences, majority voting works well. If non-single peaked, it doesn’t work as well and Condorcet cycles can occur as well as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

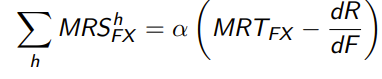

What is the equation which shows how the Samuelson rule is adjusted for distortionary taxation?

α > 1 if public good funded with distortionary taxation

dR/dF : Fiscal externality – how changing the public good F affects government revenue.

If spending on F increases tax revenue (e.g., if public goods complement taxed goods like labour), then dR/dF > 0 - less distortion, more efficient provision.

If spending on F decreases tax revenue, then dR/dF < 0 then you must provide more net benefit to justify public goods