Chapter 9 - Cognitive Development

1/44

Earn XP

Description and Tags

+ lecture 7

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

45 Terms

genetic epistemology

study of formation (genesis) of knowledge and how we know what we know (epistemology).

influenced Piaget

Piaget bases for his theory

Piaget helped Alfred Binet develop standardised IQ tests for children. He became interested in the incorrect answers that children provided to test questions, and discovered two very important findings:

Piaget noted that children of the same age made similar errors.

He found that these errors differed from those of older and younger children.

→ everything that we know and understand is filtered through our current frame of reference, we construct new understandings of the world based on what we already know.

A child has his its own logic; does not talk nonsense

A child is a young scientist, makes mini-theories, constructs knowledge.

Hence, Piaget’s approach is often labelled as a constructivist approach as it depicts children as constructing their own knowledge.

schemes

Piaget proposed that the basic unit of understanding was a scheme.

scheme = a cognitive structure that forms the basis of organising actions and mental representations so that we can understand and act upon the environment.

Coherent, fixed series of actions; can be applied to multiple situations and objects

Are necessary for the child to understand and predict what happens

Have internal consistency and are organized in a structure - For example: action patterns, reasoning rules, or strategies

Schemes make up our frames of reference through which we filter new information.

Everything we know starts with the schemes we are born with. Three of the basic schemes we are born with are reflexive actions that can be performed on objects: sucking, looking and grasping.

As children grow older they begin to use schemes based on internal mental representations rather than using schemes based on physical activity. Piaget called these mental schemes operations.

organisation and adaptation

In order to explain how children modify their schemes Piaget proposed two innate processes: organisation and adaptation.

Organisation = the predisposition to group particular observations into coherent knowledge, and it occurs both within and across stages of development.

e.g. initially young infants have separate looking, grasping and sucking schemes. Over time these schemes become organised into a more complex multisensory cognitive system that allows the infant to look at an object, pick it up and suck it. This organisation enables the child to learn about the nature of these objects (e.g. their shape, texture and taste).

However, in order to adapt to environmental demands we also need to incorporate new ideas.

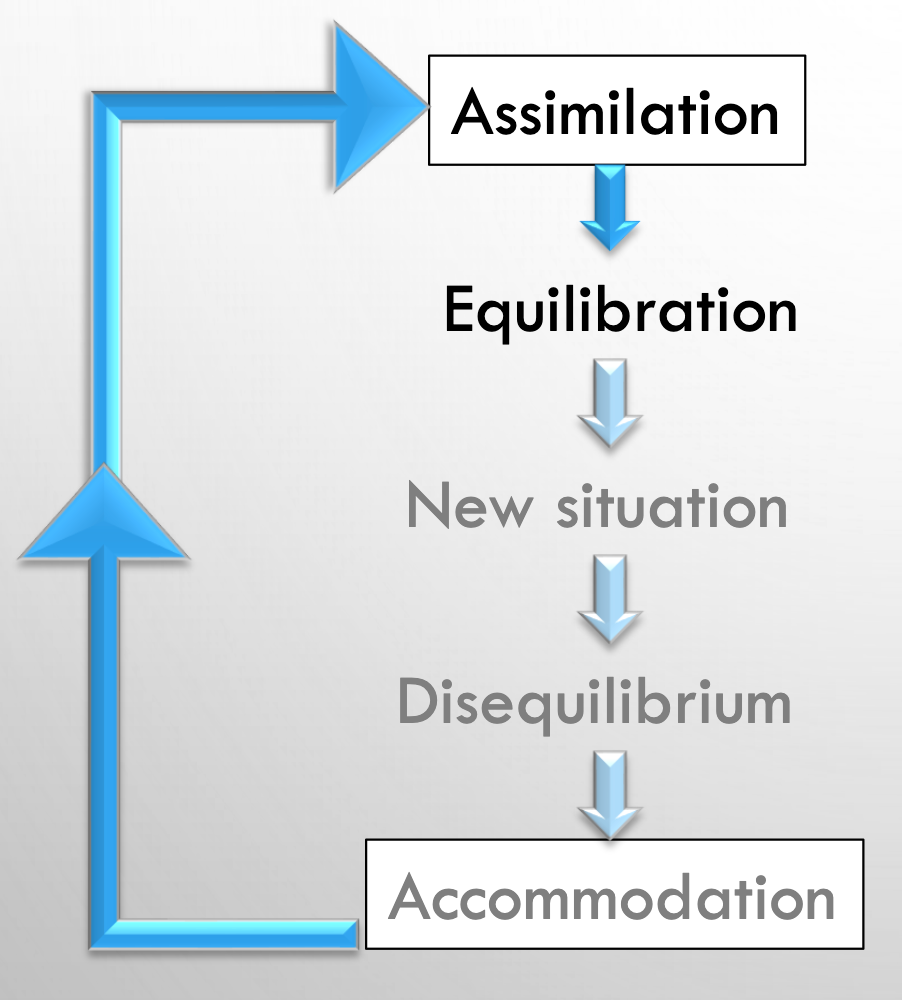

Piaget believed that adaptation is composed of two processes, called assimilation and accommodation.

When faced with a new experience, infants/children try to assimilate this new information by incorporating the information into their existing schemes.

assimilation allows us to generalise and apply what we know to many individual instances, although it may distort reality and not adapt to it.

However, if the information is incongruent, the child needs to adjust their existing concept or generate a new scheme (accommodation).

stage shifting

equilibration = a state in which children’s schemes are in balance and are undisturbed by conflict

According to Piaget we are, by nature, constantly motivated to be able to fully assimilate and accommodate to objects and situations in our environment; to reach a state of cognitive equilibrium.

At times, however, so many new levels of understanding converge that we reach a major reorganisation in the structure of our thinking.

Piaget called these shifts to new levels of thinking stages.

Stages aren’t simply quantitative additions to a child’s knowledge and skills; rather they are defined as qualitative shifts in a child’s way of thinking (abruptness assumption).

Although Piaget provided typical ages for the four main stages and various substages, the ages at which they are achieved will vary from one child to another.

However, the order of progressing through stages is invariant, with each stage based on development in the previous stage.

Piaget believed his stages were universal in two senses:

First, he thought all people would develop through the same sequences of stages.

Second, he thought that for any given stage children would be in that stage for all of their thinking and problem-solving strategies, whether in mathematical understanding, problem-solving skills, social skills or other areas (concurrence assumption), although he recognised that there were transitional periods as children moved from one stage to the next, higher stage.

Stage shift:

Qualitative new structure of thinking

Concurrence assumption → Simultaneously in different domains:

Abruptness assumption → Sudden, discontinuous shifts

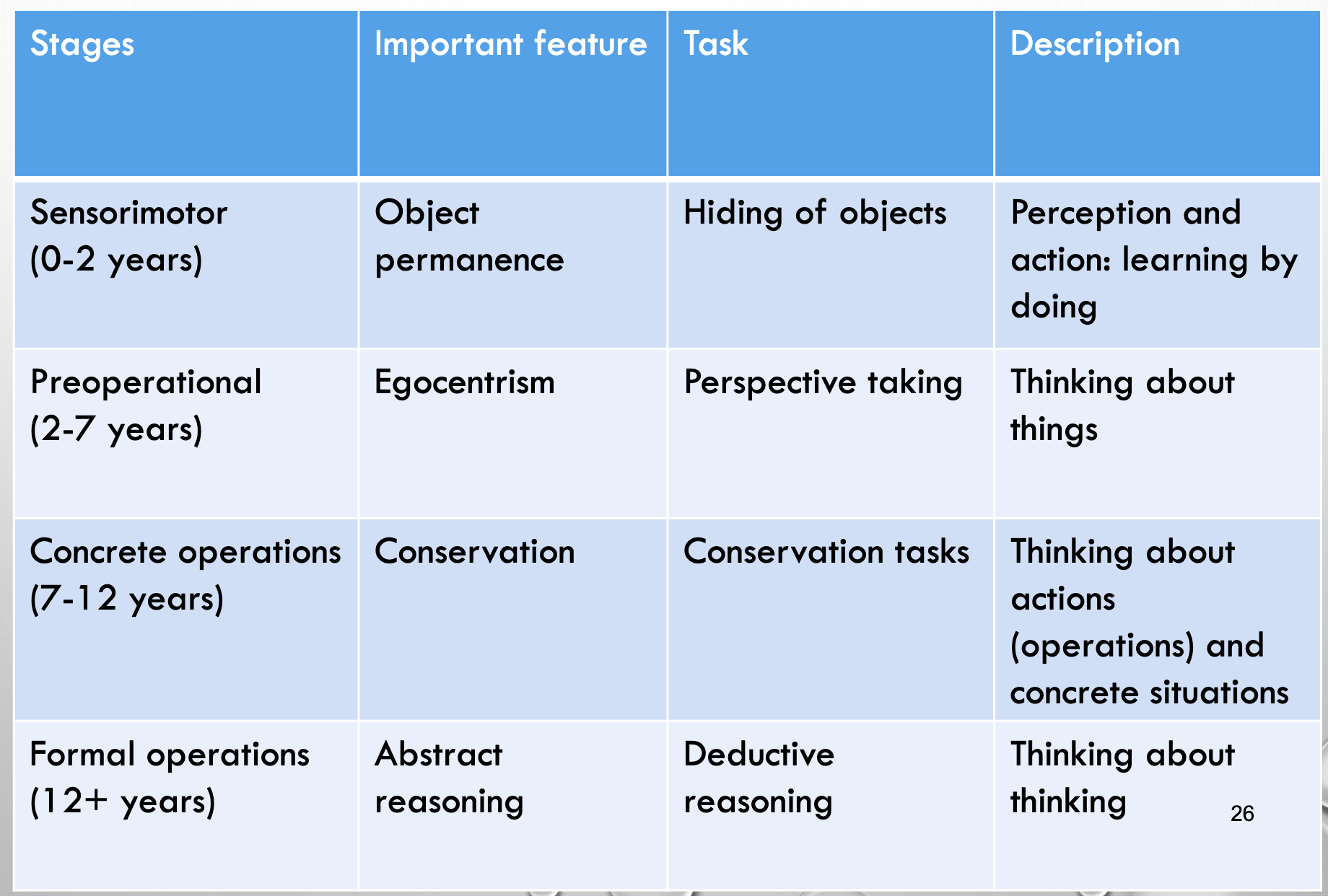

sensorimotor stage (<2yo)

= all that infants know is derived from information that comes in through the senses and motoric actions

Children explore the environment in a more and more advanced way:

The reflexive schemes substage, covers the period from birth to one month of age. During this substage infants use their innate reflexes (e.g. sucking, grasping) to explore their world.

The primary circular reactions (1–4 months), there is a shift in the infant’s voluntary control of behaviour. The infant starts to show a degree of coordination between the senses and their motor behaviour through the primary circular reactions.

The term primary is used because such repetitive behaviours are focused almost exclusively around the infant’s body and not the external world, while the term circular refers to the fact that the behaviour is repetitive.

The secondary circular reactions, which lasts from 4 to 10 months, there is a shift in the infant’s voluntary control of behaviour as they become more aware of the external world. Infants now direct their behaviour to reaching and grasping objects (behaviours become secondary). Although the actions are still circular as the infant engages in repetitive behaviour, the infant has begun to intentionally act on his environment.

Coordination of secondary schemes, which lasts from 10 to 12 months, the infant begins to deliberately combine schemes to achieve specific goals (goal-directed behaviours). Infants in this substage solve object permanence tasks in which the infant has to co-ordinate two schemes (e.g. lifting a cover and grasping an object).

The tertiary circular reactions. The child has now begun to walk and begins to search for novelty. As children consolidate their understanding of causal relations between events, they begin to systematically experiment with varying the means to test the end results.

The beginning of thought, (18-24 months) children become able to form enduring mental representations. This capacity is clearly demonstrated in toddlers’ ability to engage in deferred imitation (the capacity to imitate another person’s behaviour some time after the behaviour was observed). Enduring mental representations also mean that children no longer have to go through the trial and error method; rather they can mentally experiment by performing the actions in their minds. Further evidence for symbol use is shown in toddlers’ ability to engage in simple pretend play.

Children get a more advanced understanding of object permanence → formation of mental representations

A not B error

Piaget: Incomplete object permanence

Mental representation present, but response perseveration?

But error also occurs with only watching (no reaching)

Mental representation, but limited memory?Yes, longer waiting time makes task more difficult.

But error also occurs with hiding in transparent b-location

Mental representation, but no link with action?Based on current evidence, this is the most likely explanation.

preoperational stage (2-7yo)

What the child is able to do: language, pretend play, deferred imitation (because of mental representations)

How does the child think?

Egocentrism (no perspective taking, theory of mind)

Seeing is believing (e.g., believe in Santa Claus)

Animism (objects have properties of life)

Centration: focus on one aspect, exclusion of others (no understanding of conservation)

This stage subdivides into the symbolic function substage (2–4 years) and the intuitive substage (4–7 years).

the symbolic function substage (2-4yo)

children acquire the ability to mentally represent an object that is not physically present (symbolic thought)

Evidence of symbolic function can be seen in pretend play.

Early on the child requires a high level of similarity between external prop and referent in order to symbolise the referent (children younger than 2 years will pretend to drink from a cup but refuse to pretend that a cup is a hat)

over time, children can use external props that are dissimilar to the referent

Eventually, children can just imagine the referent and event.

Other examples of children engaging in symbolic thought can be seen in their use of language and their production of drawings.

At 16 months of age the average child comprehends over 150 words but in their early language they are restricted to producing one word at a time, and between 18 and 24 months their productions are typically restricted to two-word utterances.

However, from around 2 years this word-length restriction becomes lifted and children learn an impressive nine words a day on average.

Likewise, research shows that children understand the symbolic nature of drawings.

egocentrism

Egocentrism = the tendency to perceive the world solely from one’s own point of view.

Thus, children often assume that other people will perceive and think about the world in the same way they do.

the three mountains task: The child is asked to walk around the model and view it from different perspectives. The child is then seated on one side of the table and the experimenter places the doll in different locations around the model. At each location the child is asked to draw or choose, from a set of different views of the model, the view the doll would be able to see.

Piaget found that rather than picking the view that the doll could see, they often picked the view they themselves could see (children could not correctly identify the doll’s view from the different viewpoints until 9 or 10 yo).

This inability to take into account that another person can view the world differently can also be seen in young children’s assumption that if they know something other people will too.

criticisms:

using familiar objects (e.g. trees and houses), and asking children to rotate a small model of the display, rather than select from a set of pictures, children as young as 3 or 4 years of age were able to identify the correct perspective for others.

14-month-olds appear to engage in what is called rational imitation: when infants observed an adult turning on a light with their head, even though the adult’s hands were free, the infants copied the behaviour after a week’s delay: that is, they assumed that because the adult’s hands were free they had a reason for turning the light on with their head.

However, if the adult turned on the light with their head and their hands were tied, the infants then used their hands to turn on the light.

→ 14-month-olds can infer others’ intentions and perspectives (also found in chimpanzees).

18-month-olds can sympathise with a stranger who is in a hurtful situation but showing no emotion (affective perspective taking).

In addition, a host of research under the theory of mind topic has shown that by 4 or 5 years of age, if not earlier, children understand that other people’s mental states may differ from their own.

animism

Another limitation of preoperational thought is animistic thinking – the belief that inanimate objects have lifelike qualities (such as thoughts, feelings, wishes) and are capable of independent action.

egocentric thinking prevents them from accommodating → cannot adjust their schemes to accommodate the real-world state of affairs.

Many researchers now think that Piaget overestimated young children’s animistic beliefs.

criticism: Piaget used objects with which the children had little direct experience and relied on verbal justifications, and have also criticised the wording of the interviews, which may have confused the children.

For familiar objects, 6–12-month-olds can sort pictures of objects into categories and can distinguish between animate and inanimate objects.

By the age of 2.5 years, children attribute wishes and likes to people and animals but hardly ever to objects.

Overall, the developmental data contradict Piaget’s account and suggest that the animate–inanimate distinction emerges early in infancy, and may even be innate.

intuitive thought substage (4-7 yo)

The intuitive thought substage is characterised by a shift in children’s reasoning. Children begin to classify, order and quantify in a more systematic manner.

Piaget called this substage intuitive because although a child can carry out such mental operations they remain largely unaware of the underlying principles and what they know ( largely based on perception and intuition, rather than rational thinking).

→ when preoperational children are asked to arrange 10 sticks in order of length (a seriation task), some children sort the short sticks into a pile and the longer ones into another pile, while others arrange one or two sticks according to length but are unable to correctly order all 10 sticks.

Researchers have challenged Piaget’s account that children’s successful solutions to seriation tasks are based on underlying changes to mental operations that develop during the next major stage of development (the concrete operations stage).

Some researchers have suggested that the difficulty the preoperational child faces in verbal inference tests results from a lack of memory capacity. When researchers have employed procedures to ensure that children remember the information that they are given then young children can grasp transitive inference.

transitive inference

= the ability to seriate mentally between entities that can be organised into an ordinal series.

if A>B and B>C, then we can infer A>C.

Bryant & Trabasso (1971) conducted an experiment that showed that 4-year-old children could make transitive inferences as long as they were trained to remember the premises.

Hence, researchers have argued that children’s failure during the preoperational stage resulted from their failure to remember all of the relevant information rather than not possessing the necessary logic needed to make the correct inference.

hierarchical classification tasks

The limitation of relying on the preoperational logic of young children is clearly illustrated in their performance on class inclusion tasks (involve part–whole relations in which one superordinate set of objects can be divided into two or more mutually exclusive subordinate sets).

Typically, one of the subordinate sets contains more members than the other.

when a preoperational child is presented with a bunch of seven roses and two tulips they can easily state that there are more roses than tulips.

when asked if there are more roses than flowers they typically state that there are more roses.

Piaget proposed that children have difficulty in focusing on a part of the set (e.g. roses) and, simultaneously, on the whole set (e.g. fl owers). This idea is similar to Piaget’s account of young children’s failure to conserve.

More recently, researchers using simpler questions have found that children as young as 4 years of age were able to solve part–whole relations problems.

There is plenty of evidence that young children have formed a variety of global categories based on common natural kind, function and behaviour.

These findings challenge Piaget’s proposal that young children’s thinking is governed by the way things appear. Rather, Gopnik and Nazzi suggest that preoperational children are able to draw inferences about category membership based on non- observable characteristics.

Children’s skill at categorising objects across the pre-school years is supported by gains in general knowledge and a rapid expansion in vocabulary. As children discover more about their world they form many basic-level categories and by 2–3 years of age children can categorise an object according to a superordinate category.

Blewitt found that by the age of 2 children were able to include the same object into both a basic-level and a superordinate-level category. Hence, whilst young children’s categorical knowledge is not as rich as that of older children, the capacity to classify in a hierarchal manner is present in early childhood.

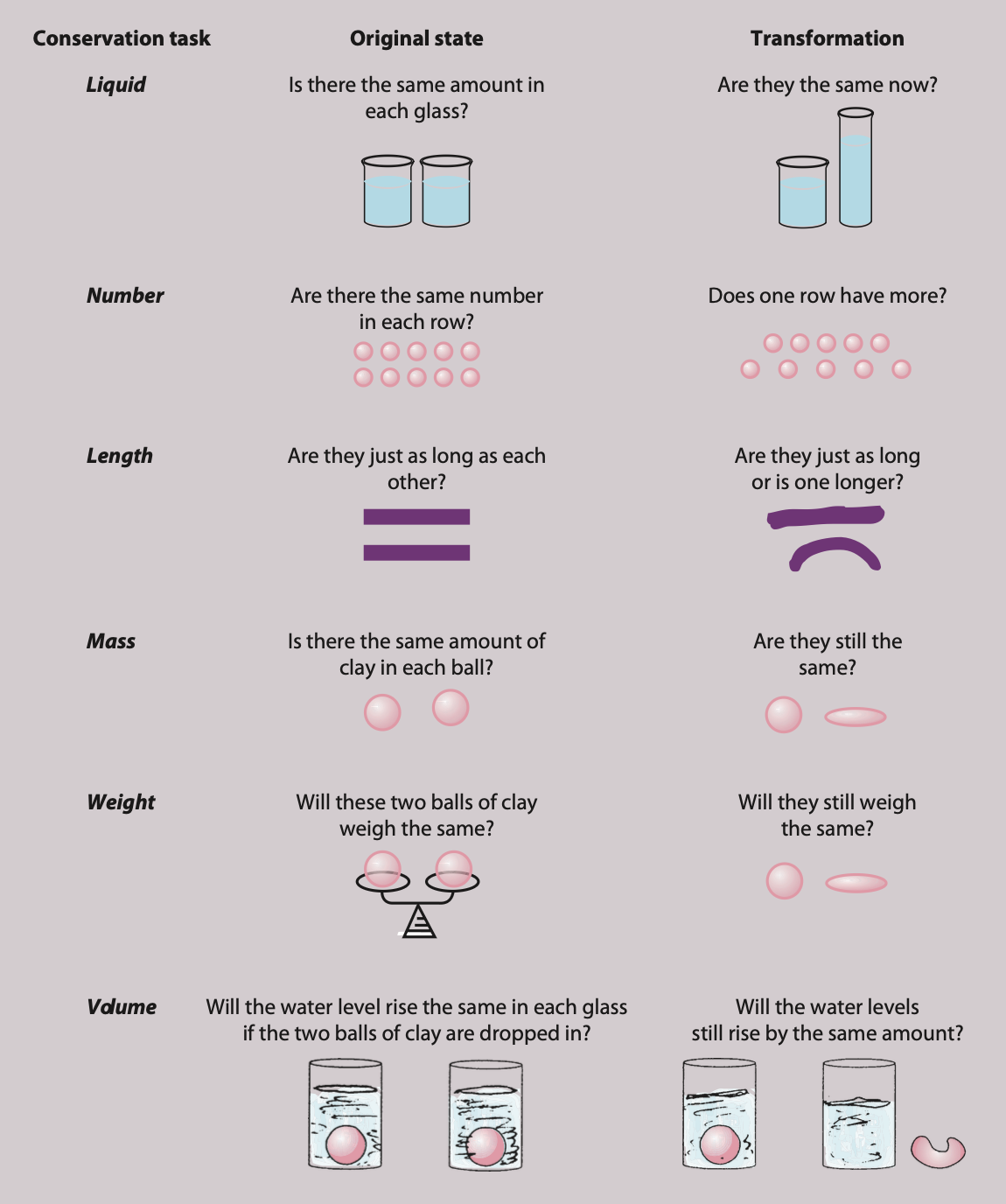

conservation tasks

Children who are able to conserve must recognise that certain characteristics of an object remain the same even when their appearance changes (a piece of clay rolled into a ball then rolled out to look like a sausage is still the same object and contains the same amount of clay as before). Although its superficial appearance has changed, its quantity has not.

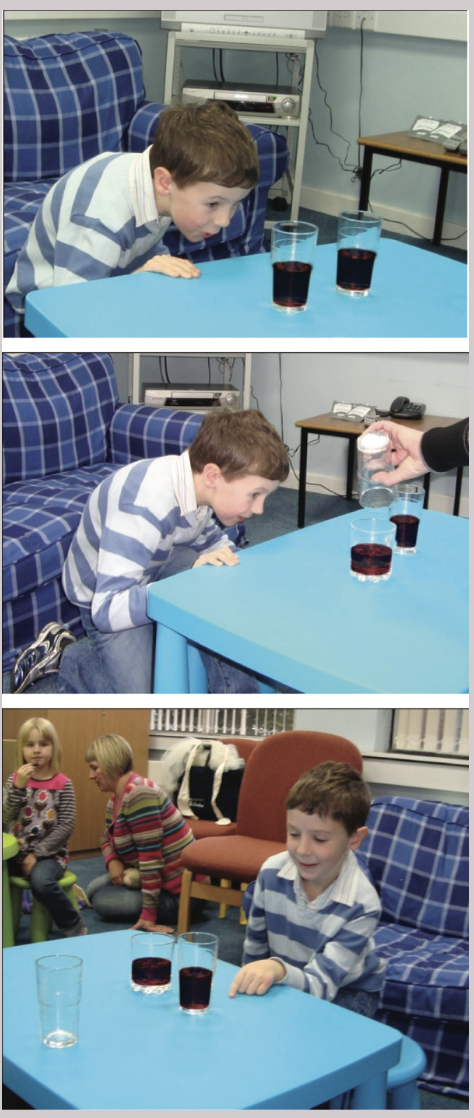

A frequently cited conservation task involves pouring the same amount of liquid into two identical drinking glasses . Once the child has agreed that both glasses contain the same amount of liquid, the water from one glass is poured into a shorter, wider glass. Children are then asked whether there is the same amount of liquid in both glasses or whether one has more liquid. Below the ages of 6 or 7 children often reply that the taller glass contains more liquid. In other words they lack the knowledge that the volume of water is conserved.

In a conservation of number task the child might be shown two rows of counters or sweets/candies, with each laid out in one-to-one correspondence. The child is then asked whether there is the same number in each row; all children will say ‘yes’. The experimenter then makes one of the rows of counters longer by increasing the distance between each counter. The child is again asked whether there is the same number in each row. Even though no counters have been added or taken away, the non-conserving child often says there are more counters/sweets in the longer row.

In a typical conservation of mass task, a child may be shown two balls of modelling clay, and agrees that there is the same amount of clay in each ball. While the child watches, one of the balls of clay is rolled out and becomes longer. The child is then asked if there is still the same amount and a non-conserving child will typically say that there is more in the piece of clay that is cylindrical in shape.

limitations in preoperational conservation tasks

Piaget proposed that the preoperational child’s inability to conserve is characterised by three main limitations:

the child being unable to engage in decentration: cannot focus on two attributes (i.e. height and width), at the same time. Rather, the child engages in centration – the tendency to focus on one attribute (e.g. height) at a time → judges that the taller glass contains more liquid.

the child’s inability to understand reversibility: cannot mentally reverse the action of pouring the liquid from the short glass back into the tall glass, → work out that the volume of liquid has not changed.

the child’s tendency to focus on the end state rather than the means. Rather than focusing on the experimenter’s action of pouring the liquid from one glass to another (the means), the child focuses on the end state in which the level of liquid in the tall glass is now higher than the liquid level in the shorter glass.

horizontal dècalage

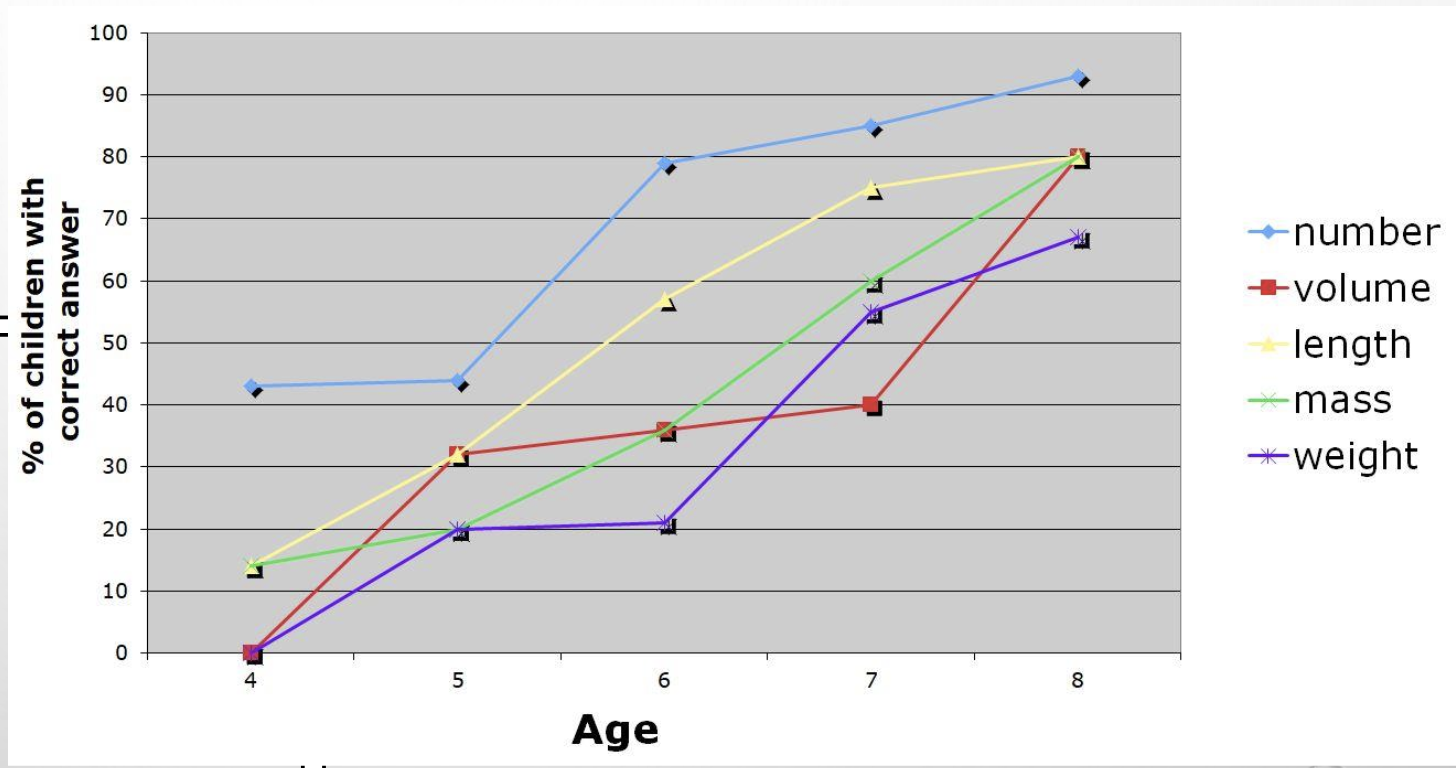

It is important to note that the age at which children attain conservation varies across culture, and depends on the substances and concept they are asked to conserve.

Generally, in Western societies, children acquire the ability to conserve number at around age 6, followed by the ability to conserve liquid, length and mass between the ages of 6 and 7. However, children are not able to conserve weight and volume until aged 9, and after age 11, respectively.

Whilst Piaget acknowledged that these ages were approximations, he argued that the order in which children acquire these concepts remains constant for all children from all cultures, because knowledge of the simpler concept is essential in order for the child to attain the more abstract concept.

Piaget proposed that the age differences found on different types of conservation task reflected a phenomenon called horizontal décalage (age differences in solving problems which appear to require the same cognitive processes).

vertical dècalage

In fact, there is even a type of conservation of weight that can be found in infants. If infants are offered rods that differ in their length then, with practice, they will display differential preparation for their expected weights, expecting the longer rods to weigh more. If the rods are then switched so that their weights are changed then the infant’s arms will rise, or fall, if the rod is lighter or heavier than expected.

Mounoud and Bower found that if 18-month-old infants saw a transformation to a longer rod, by folding it in two so that it was much shorter, they expected it to weigh the same as when it was longer.

This appears to be a sensorimotor form of conservation of weight, and within Piagetian terminology this is an example of a vertical décalage, which is where what the child understands at one level or stage (in this case at the level of action) must be reconstructed at a later age on a different level of understanding (e.g. the level of verbal thought).

appearance-reality tasks

Piaget believed that young children tend to focus exclusively on the perceptual features of objects. This tendency would make it very difficult for these children to pass appearance–reality tasks in which appearance and reality diverge.

A study by Rheta DeVries (1969) investigated children’s ability to distinguish appearance from reality by allowing children to play with a cat called ‘Maynard’. After the children had played with the cat for a short period of time, the experimenters covered the front half of the cat with a screen and surreptitiously strapped a realistic mask of a ferocious dog onto the cat’s head.

Three-year-olds’ answers revealed that they tended to focus solely on the cat’s appearance rather than the reality (Maynard was still really a cat!) by saying that the cat had become a ferocious dog.

Whilst the 4- and 5-year-olds did not believe that the cat could transform into a dog they did not always answer the test questions correctly.

It was not until age 6 that children answered all of the test questions correctly, by saying that it was really a cat but it looked like a dog.

John Flavell and colleagues reported similar findings in an appearance–reality task in which they presented children with objects that appeared to be one thing but were in reality another (e.g. a sponge that looked like a rock). After physically exploring the object, children were asked ‘What does that look like?’ and ‘What is it really?’

Four- and five-year-olds respond in an adult manner (i.e. the object looks like a rock but really is a sponge).

The majority of 3-year-olds fail to differentiate between the object’s appearance and reality. They typically make two kinds of error:

a phenomenism error (i.e. saying that the object looks like a sponge and really is a sponge); phenomenism = knowledge that is limited to appearances

an intellectual realism error (i.e. stating that the object looks like a rock and really is a rock); realism = believing that things are as they appear and not what they might be

Flavell and colleagues account for these findings by suggesting that 3-year-olds are not proficient at dual encoding, that is, the ability to represent an object in more than one way at the same time.

However, in a task in which children have to understand that a model room is a symbolic representation of the full-size room, three-year-old children were able to succeed, giving strong evidence for the ability to have dual representations in early childhood.

In Flavell’s task, only 29% of the 3-year-olds passed the standard task, whereas 79% of the 3-year-olds passed the same task, but when the goal was to trick someone else.

→ 3-year-olds are capable of forming dual representations of objects.

Other researchers have suggested that young children’s failure on these tasks may, in part, result from a difficulty in formulating the appearance–reality distinction into words (children perform better in the non-verbal task).

concrete operations stage (7-12yo)

Conservation is fully understood

Seriation (putting items in a logical order)

Transitive inference (if a>b and b>c, then a>c)

Class-inclusion (“are there more roses or more flowers?”)

During this stage children develop a new set of strategies called concrete operations (although children’s thought is more logical and flexible, their reasoning is tied to concrete situations).

They have attained the processes of decentration, compensation and reversibility and, thus, can solve conservation problems.

To illustrate, children not only begin to pass liquid conservation tasks but are aware that a change in one aspect (e.g. height) is compensated by a change in another aspect (e.g. width).

Moreover, children often state that if the water is poured back into the original glass then the liquid in both glasses will be the same height (reversibility).

This understanding of reversibility underlies many of the gains reported during this stage of development. Subsequent research has confirmed that children appear to

acquire conservation of number, liquid, mass, length, weight and volume in that order, which is the order Piaget proposed.

They can also seriate mentally, an ability named transitive inference if they see the subjects, but if the same problem is presented verbally, in an abstract form, the child encounters difficulty in solving the problem.

→ the concrete operational child can seriate mentally, it appears that the objects necessary for problem solution need to be physically present.

Between the ages of 7 and 10, children gain in their ability to classify objects and begin to pass Piaget’s class inclusion problem. They can attend to relations between a general and two specific categories at the same time

Other research has also shown that children’s performance on tasks may be influenced by the context of the task, especially culture and schooling.

formal operations stage (12+)

Capacity for abstract scientific thought

Manipulating ideas in your head without seeing concrete objects

Ability to theorize about impossible events and items

Mathematical calculations

Think creatively

Example : Third eye problem

Piaget overview

criticism of Piaget

CONCEPTS TOO VAGUE

Many researchers argue that the basic processes (e.g. assimilation, accommodation and equilibrium) are vague and tend to describe, rather than explain how change occurs.

Still discussion about interpretation of the theory

Piaget often misjudged the ages at which children show evidence for understanding a particular concept. This may have resulted from the fact that he often failed to distinguish between competence and performance (there are many factors (e.g. memory capacity, context) other than understanding a concept that may be required to solve a task. - children failed tasks not because they lacked competence but rather because they failed to demonstrate it on tasks due to performance demands.

Piaget did not pay enough attention to the role of culture and social interaction in shaping cognitive development. The effect of schooling suggests that Piaget’s assumption that children’s learning is driven primarily by constructing their own knowledge by acting on the environment is too narrow. It is rather that teachers and adults guide children’s learning by helping them focus on important issues.

Hard to falsify - he always had an answer to counter-evidence (comparable to Freud)

Recent research has raised serious questions regarding the universality of Piaget’s stages. In Piaget’s conception, once a person has consolidated the skills and understanding of a particular stage, that person will be functioning cognitively in that stage regardless of the particular problem or domain of knowledge. However, many researchers propose that a child might use concrete-operational thinking on one task and use preoperational thinking on another.

Researchers have also investigated the universality of Piaget’s stages by conducting cross-cultural research: both Egyptian and Saudi Arabian Bedouin children progress through the same order of stages. However, cultural factors influence children’s progression through Piaget’s stages.

DO STAGES REALLY EXIST?

How to operationalize/measure a stage?

No mechanism for emergence of qualitatively new knowledge (learning paradox)

INCONSISTENT FINDINGS

a. Water-level task: 30% of adults fail. Most 9-year-olds should be able to perform correctly, according to Piaget.

b. At what ages can people perform specific tasks?

Infants can do more than Piaget thought and adults less:

Very young infants have an implict understanding of object permanence and deferred imitation;

Many adults do not perform well on formal operational tasks

child to understand and predict what happens

• Have internal consistency and are organized in a structure

• For example: action patterns, reasoning rules, or strategies

c. Décalages: similar changes in development at different ages

- Vertical décalage: understanding of a task increases over time

- Horizontal décalage: a specific principle is applied to different tasks at different times.

PROBLEMS WITH METHODS:

Piaget’s measurement methods:

Small sample sizes

Observations in case studies

Clinical interviews; Advantage: children give answer + argumentation; Disadvantage: shyness, adult = authority

Piaget’s criteria are very strict (correct argumentation)

Explicit knowledge

In infant research the criteria are less strict (significantly longer looking time above chance level is sufficient)

Implicit knowledge

When using the same criteria for all age groups, you may find very different results.

effects on current education and teaching

Learning by exploring and understanding (see Vygotsky as well)

Inquiry-based education (discovery learning)

• Experiments in science lessons

• Interactive exhibitions in museums

• Digital workbook in first year

• “Readiness”: is the child ready for the next step in development?

neo-piagetians: Robbie Case

“Piagetian”: stagewise development

“Piagetian”: children form new conceptual structures

Different: focus on social and individual experience

Different: focus on development of executive functions, such as working memory and processing speed, explaining horizontal décalage

Case adopted an information processing perspective to cognitive development in that he attributes changes within each stage and across stages to working memory.

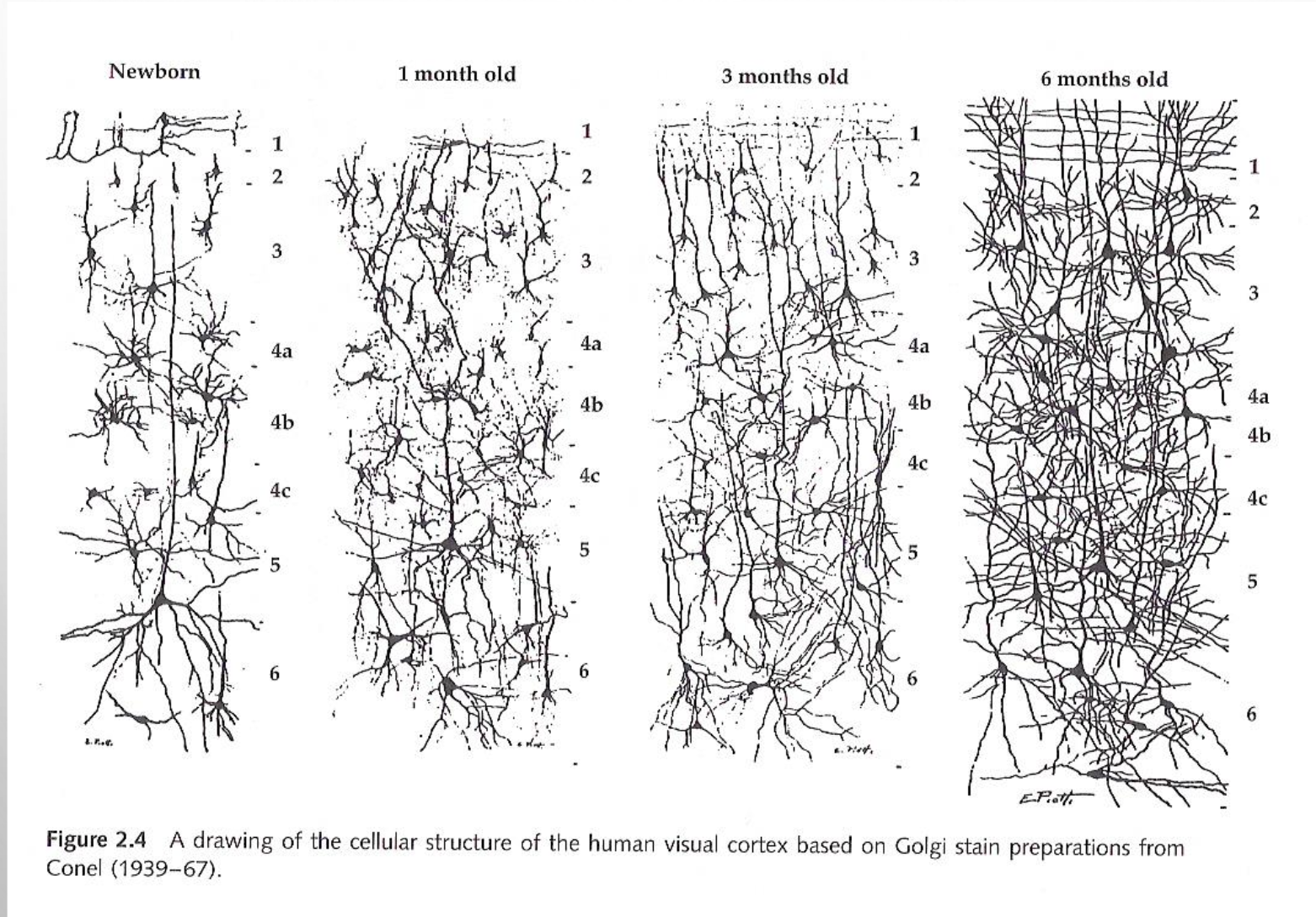

Case attributed increases in working memory capacity to three factors: brain development, automatisation and the formation of central conceptual structures.

brain development: as children get older neurological changes within the brain result in increased working memory capacity. → they are able to attend to more operations in working memory at the same time.

However, at a given age there is a biological limit on how many operations can be stored in working memory.

automatisation: as children get older they become more practised with Piagetian operations, and by repeatedly practising certain operations, their processing of these operations becomes more automatic. This increased efficiency in processing operations or schemes means that there are fewer demands on working memory, and free working memory capacity can be used for combining schemes and generating new schemes.

the formation of central conceptual structures: increased processing efficiency, combined with increased free working memory capacity, allows children to generate central conceptual structures – semantic networks of concepts which represent children’s knowledge in a particular cognitive domain (e.g. number, space). Case argues that when children form a new conceptual structure they move to the next stage of development.

Compared to Piaget, Case’s theory provides a far more satisfactory account of horizontal décalage. Simply, conservation tasks vary in their processing demands, with those tasks which require more working memory capacity being acquired later. The development of central conceptual structures, however, is not only affected by biological maturation, but also through social and individual experience. Hence, a child who is particularly interested in reading but not drawing will display more advanced conceptual structures in reading.

neo-piagetians: Robert Siegler

“Piagetian”: acquisition of better strategies over time

“Piagetian”: use of balance scale task

Different: measurement of strategies is nonverbal

Different: continuous changes to new strategies

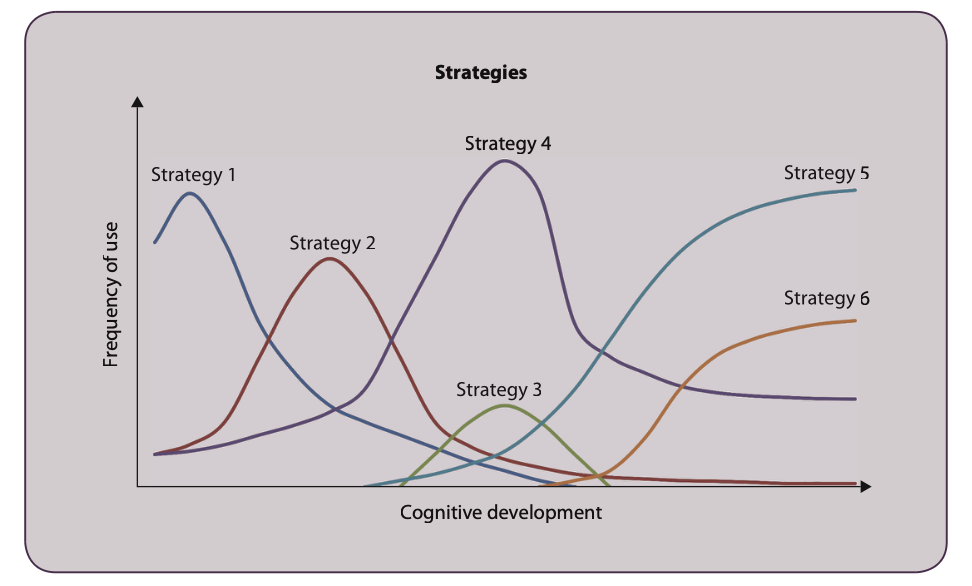

Unlike Piaget’s theory, which depicts a child as thinking about a given task in a single way, Siegler suggests that when attempting to solve tasks (e.g. arithmetic, reading, number, conservation) children may generate a variety of strategies.

For example, on tests of number conservation, while a 5-year-old child might often state that there are more counters in the longer row, but in another trial, the child may decide to count the number of counters in each row.

Siegler argues that children are most likely to use multiple strategies which compete with each other (hence overlapping waves) when they are still learning about how to solve a task.

In Siegler and Robinson’s study each child was asked to complete a number of addition problems over six sessions. The researchers found that the children tended to use four main strategies: (a) counting aloud using fingers; (b) counting on fingers without counting out loud; (c) counting out loud without using fingers; and (d) retrieving answers from memory.

Only 20 per cent of children consistently used one strategy for all of the addition problems.

When children were given exactly the same addition problem in a second testing session, 30 per cent used a different (not necessarily more sophisticated) strategy in the second testing session.

→ when children are learning about how to solve a task they have available a range of different strategies to use at the same time, rather than just one.

→ there is considerable variation in the adoption rate of new strategies. As children identify and experiment with different strategies they begin to realise that some are more effective in terms of accuracy and time than others. → some strategies become more frequently used whilst strategies that are not frequently used tend to ‘die off’ (overlapping waves).

Siegler solves Piaget’s problem of the variation in children’s thinking and also accounts for continuous change in children’s thinking.

neo-piagetians: Annette Karmiloff-Smith

“Piagetian”: neuroconstructivism

“Piagetian”: do not focus on results, but on how the child constructs the result

Different: developmental neuroscientist

Different: understanding the development of disorders, especially Williams syndrome

At birth there are hardly any connections between neurons in cortex. These connections arise based on active exploration and experience → Child ‘constructs’ its own brain

core knowledge: nativism

Elizabeth Spelke:

Infants are born with five systems of core knowledge about: objects, persons (agents), number, spaces, geometric forms.

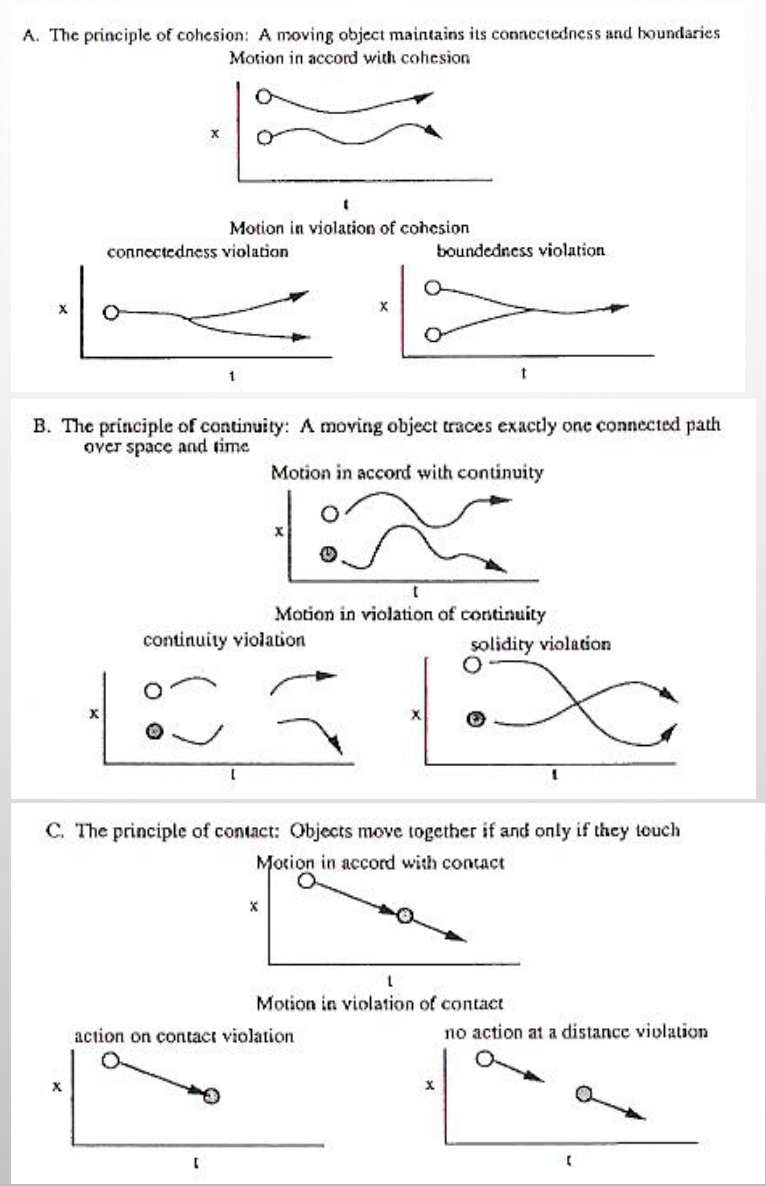

Three principles about objects and their motions:

A. Cohesion

B. Continuity

C. Contact

The importance of eye contact: infants one day after birth saw either a face looking straight at them or a face looking at them - infants look longer at the face looking at them, they turn to the face with the eyes towards them.

nativism vs constructivism

You need both to explain the development of children:

Infants are born with sensorimotor intelligence and core knowledge

With sensorimotor intelligence, infants construct their own knowledge

With core knowledge, infants have basic innate knowledge, tendencies or preferences that help them survive

Piaget on moral development

Premoral: Young children have no clear sense of morality (preoperational)

Heteronomous morality: Rules set by authority figures are sacred and unalterable (concrete operational)

Autonomous morality: Rules are agreements that can be discussed and changed (formal operational)

criticism on Piaget’s moral development

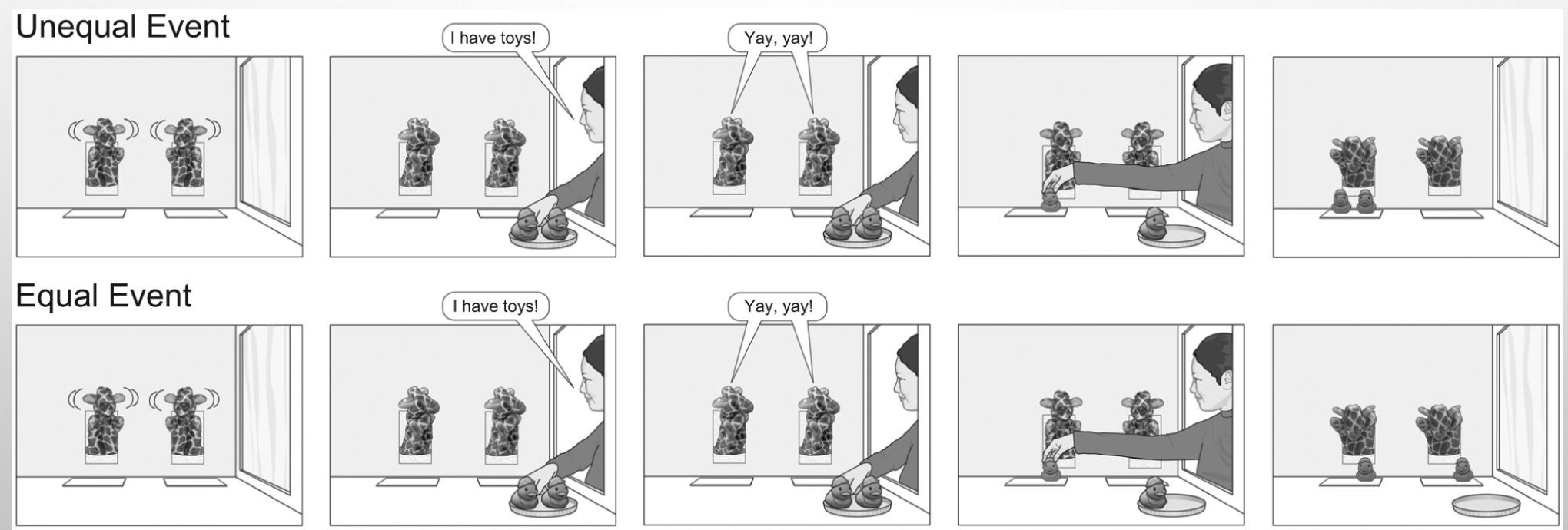

Looking time is measured. Infants (18-months-olds) look longer at the unequal event

Implication: infants were suprised/intrigued by the unequal event.

Infants seem to have a sense of fairness.

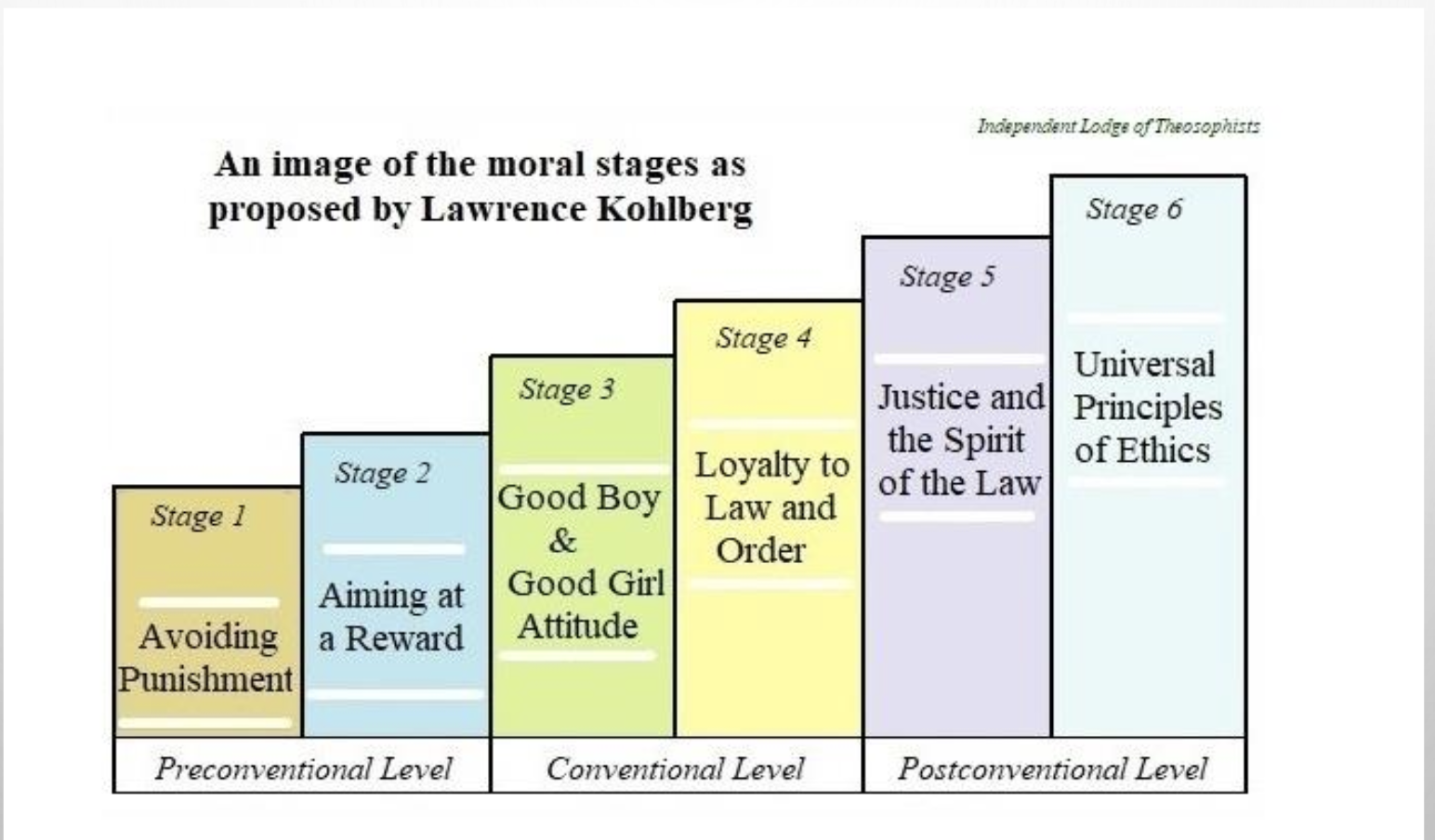

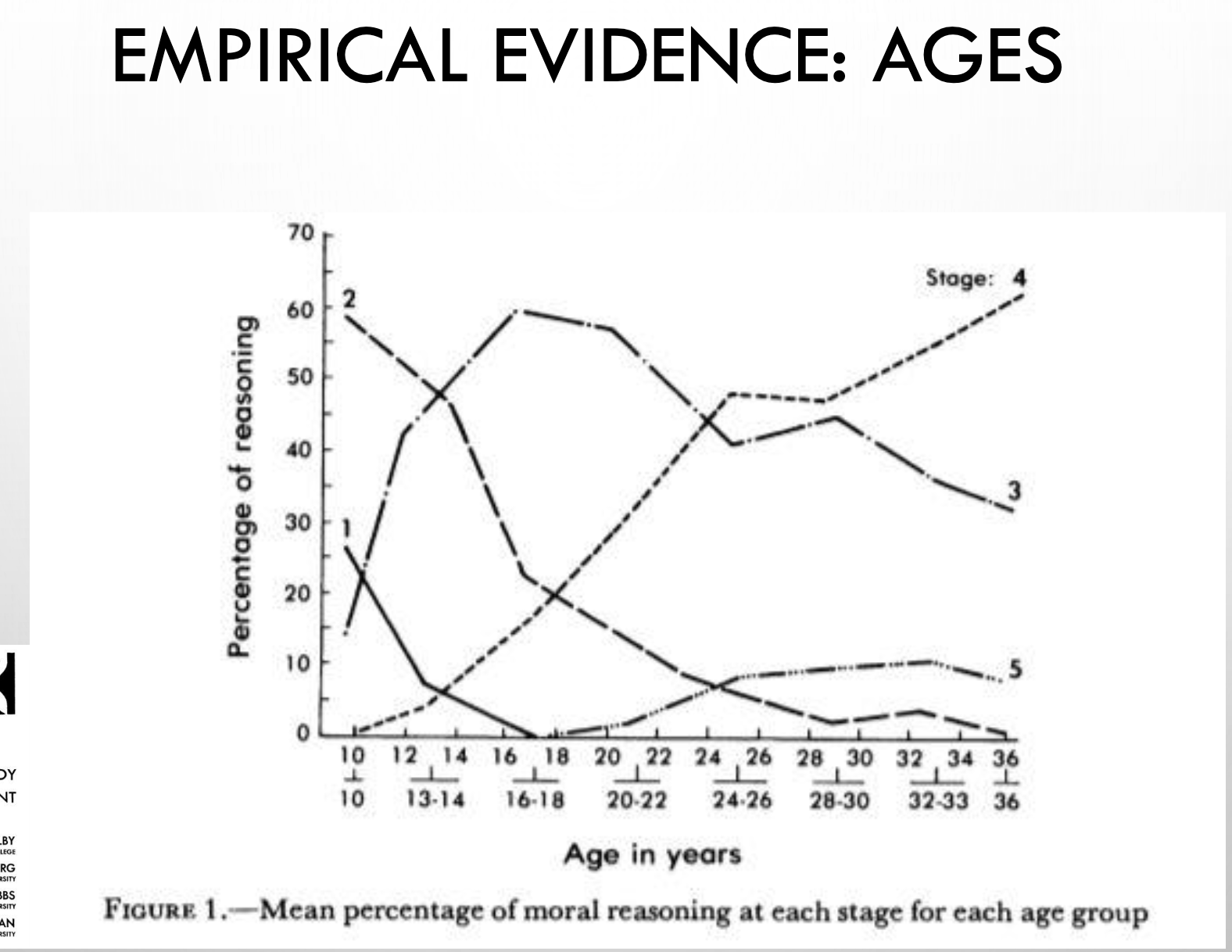

Kohlberg’s theory of moral development

Just as Piaget, Kohlberg worked with moral dilemmas

The most famous one: The Heinz dilemma (should you steal drug for wife with cancer)

Kohlberg level 1: Preconventional Morality

Stage 1: Punishment orientation

Rules are obeyed to avoid punishment

Heteronomous morality: rules are sacred

“Heinz should not steal the drugs, because the police will arrest him”

Stage 2: Instrumental orientation

Rules are obeyed for personal gain

Awareness that there are two sides to every argument

“Heinz should steal the drugs only when his wife is loving and kind”

Kohlberg level 2: Conventional Morality

Stage 3: ”Good boy” or “good girl” orientation

Rules are obeyed for approval

Interpersonal normative morality: be good, otherwise feel guilty

“Heinz should steal the drugs, otherwise his wife won’t love him anymore”

Stage 4: Maintenance of social order

Rules are obeyed to maintain the social order

Social system morality: law and order orientation

“Heinz should not steal the drugs, because when everyone is stealing, society will collapse”

Kohlberg level 3: Postconventional Morality

Stage 5: Morality of contract and individual rights

Rules are obeyed when they are impartial

Human rights and social welfare morality: make use of ethical principles

“Heinz should steal the drugs, because life is more important than money”

Stage 6: Morality of conscience (added later to the theory)

The individual establishes his or her own rules in accordance with self-selected universal ethical principles

Heinz dilemma does not apply here – this kind of morality refers to societal issues such as using violence in order to change the political system

criticism of Kohlberg’s theory of moral development

Kohlberg, just like Piaget, underestimated children’s reasoning

Judgement is not the same as action

Kohlberg’s theory does not cover all aspects of morality

Social cognition is much broader than moral reasoning

The stages are not universal – cultural differences

Moral judgement is related to personality – being able to regulate emotions is associated to faster moral development

Young children are naturally altruistic - children help and enjoy helping

Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective: psychological tools

Like Piaget, Vygotsky viewed the child as an active seeker of knowledge.

However, Vygotsky emphasised that children’s thinking is influenced by social and cultural contexts. He viewed children as being part of society and collaborators in their own learning with adults.

According to this theory we share lower mental functions such as attention and memory with other animals and these functions develop during the first two years of life. Those abilities which differentiate humans from other animals are the mental or psychological tools we acquire that transform these basic mental capacities into higher cognitive processes.

Vygotsky proposed that psychological tools are acquired through social and cultural interactions.

Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective: private speech

Vygotsky viewed language as the most important psychological tool in cognitive development.

Piaget believed that egocentric speech is a reflection of young children’s difficulty in perspective taking;

Vygotsky argued that children actually engage in private speech as a form of self-guidance (e.g. Berk, 1992).

As children master the use of language they not only use language as a means of communicating with others but also for guiding thinking and behaviour. At first children talk to themselves out loud. However, as they gain more experience with tasks (e.g. categorisation, problem-solving) they internalise their self-directed speech. Vygotsky called this private speech.

Eventually this private speech becomes the mediating tool for the child’s thinking and the child uses private speech to think and plan.

Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective: zone of proximal development

Unlike Piaget’s stage theory, Vygotsky argued that children’s learning takes place within a fuzzy range along the course of development; within the zone of proximal development (ZPD).

According to Vygotsky the zone covers three developmental levels.

The lower level is called the actual level of development and reflects what the learner can do unassisted;

The upper level of the zone is called the potential level of development and reflects what the learner cannot yet do.

Everything between these levels is called the proximal development (i.e. it is proximal to the learner’s last fully developed level).

Vygotsky drew attention to the fact that whether a child can successfully solve a problem or pass a task depends on many environmental factors (e.g. whether the child is helped by another person, whether the problem is worded clearly, and whether any cues are provided).

In more challenging tasks adults can provide the child with guidance by breaking down the task into manageable pieces, offering direct instruction, etc. For this guidance to be of benefit to the learner it must fit the child’s current level of performance. This type of teaching is referred to as scaffolding.

As the child becomes more competent and begins to master the task the adult gradually withdraws assistance. The child internalises the language and behaviours used in these social interactions and it becomes part of their private speech, which in turn mediates their thinking and planning.

With the development of new skills at a higher level of mastery both the actual level and the potential level increases. Hence, the entire ZPD is dynamic and moves with development. Unlike Piaget’s stage theory in which the child is at the same level of thinking across all domains, Vygotsky proposed that each domain has its own dynamic zone.

Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective: guided participation

Scaffolding, as a means of supporting the learner, may not be appropriate in all contexts. For example, adults often support and engage in social interactions involving pretend play but this instruction differs in nature from the direct instruction given when solving a problem-solving task.

More recently, Rogoff has suggested the term guided participation as a way of capturing children’s broad opportunities to learn through interaction with others.

While Piaget viewed pretend play as a way for children to act out situations they didn’t understand, Vygotsky saw pretend play as an area in which children advance themselves as they try out new skills.

When children engage in pretend play, imaginary situations are created from internal ideas, rather than outside stimuli eliciting responses from the individual.

In pretend play children often use one object to stand for another. Gradually, they come to realise that a symbol (an object, an idea, or an action) can be differentiated from the referent to which it refers.

Pretend play is rule-based. Children adhere to social and cultural norms that govern behaviour.

evaluation of Vygotsky’s theory

While Piaget has been criticised for emphasising the role of the individual while ignoring the role of culture in development, Vygotsky has been criticised for placing too much emphasis on the role of social interaction.

It is probably fair to say that some learning occurs through social interaction and some learning is individually constructed through discovery learning.

theory of core knowledge

= proposes that humans are endowed with a small number of domain-specific systems of core knowledge at birth and that this core knowledge becomes elaborated with experience.

Knowledge theory is often regarded as being domain-specific because theorists posit that specific modules are responsible for a particular kind of core knowledge. The principles governing reasoning in each domain are distinct because infants only apply them to entities within a specific domain.

Each set of principles forms a specific system that is characterized by a set of signature limits; and whilst there is some debate over the number of core knowledge systems, Spelke and colleagues have recently proposed that there are five systems of core knowledge:

Knowledge of objects and their motions.

Knowledge of agents and their goal-directed actions.

Knowledge of number and the operations of arithmetic.

Knowledge of places in the navigatable layout.

Knowledge of geometric forms and their length and angular relations.

These systems are at the core of mature reasoning in these domains and it is these systems that support knowledge acquisition in children.

These systems are also found in diverse cultures, and in controlled-rearing experiments, diverse species represent number, objects, agents, places and geometric forms in the same ways human infants do.

Core knowledge theory differs from the other theories mentioned in this chapter in that these theorists argue that some aspects of knowledge are innate.

Many researchers argue that it cannot provide an adequate account of child development. However, this theory does provide an account for infants’ and young children’s abilities to perceive and reason about object properties, number, and geometry.

theory of core knowledge: objects

The system of object representation centres on the spatio-temporal principles of cohesion (objects move as connected and bounded wholes), continuity (objects move on connected, unobstructive paths) and contact (objects do not interact at a distance).

These principles enable infants, and adults, to perceive object boundaries, to represent the entire shape of objects that are partly out of view, and to make predictions about how an object will behave.

Some studies by Rene Baillargeon et al. using the violation of expectancy paradigm suggest that in the first few months of life infants have some awareness of these basic object properties!

The system of object representation has a number of signature limits: infants are only able to represent about three objects at a time, and interestingly adults also fail to track entities beyond this set size limit.

Despite having no number words beyond the number two, the Piraha, a remote Amazonian group, track objects with the same signature set-size limit as adults in Western cultures.

theory of core knowledge: agents

Spatio-temporal principles do not govern infants’ representations of agents; rather intentional actions of agents are directed to goals and these goal representations guide infants’ imitations of others and their social interactions, such as helping behaviours.

There is considerable controversy as to whether infants’ representations of agents are innate.

Woodward et al. showed that infants are more likely to understand other people’s intentions in reaching for objects after they themselves have learned to intentionally reach for objects, suggesting that infants have to first learn from their own intentional actions before being able to interpret the intentional actions of others.

However, core knowledge theorists claim that recent research on efficiency in achieving goals, contingency, reciprocity, and gaze direction are the key principles that provide the signatures of agent representations.

theory of core knowledge: number

There is now a considerable wealth of evidence that infants can discriminate between visual arrays on the basis of number. This ability persists across the lifespan and is also common to non-human species.

Recent research has shown that infants can discriminate between large numbers of objects and that infants can even add and subtract.

Like the other systems, the core number system has its own signature limits.

Research has shown that infants’ numerical discrimination shows a ratio limit.

Six-month-olds can discriminate between 8 vs 16 dots in a visual array but not between 8 vs 12 dots.

Nine-month-olds can discriminate 8 vs 12 dots but not 8 vs 10 dots.

If numerical knowledge is core knowledge it should not only be present across development but should be universal (i.e. it should be present across different cultures).

The Munduruku people are an isolated tribe located in the Amazonian rainforest. Although Munduruku adults and young children received no formal instruction in mathematics they show a ratio limit on precision similar to adults in France and can perform approximate addition and subtraction on large numerosities.