Chapter 1 Quiz (Quiz 2)

1/19

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

20 Terms

Why does Aristotle think students should know rhetoric?

More than two millennia ago, Aristotle told students that they needed to know and understand and use the arts of rhetoric for two major reasons:

To be able to get their ideas across effectively and persuasively, and

To protect themselves from being manipulated by others.

Why do we argue?

To convince and inform (9)

To persuade (11)

To make decisions (12)

To understand and explore (13)

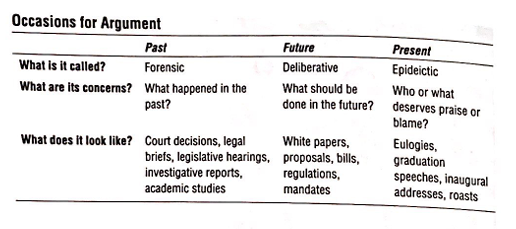

What are the differences between epideictic, forensic, and deliberative arguments?

Past- Forensic Argument: what has happened in the past (15).

Future-Deliberative Arguments: What will or should happen in the future (17).

Present-Ceremonial/epideictic argument: explore the current values of society, affirming or challenging widely shared beliefs; who or what deserves praise or blame (17).

Arguments about action: Which argument implies action? Explain .

Arguments to Persuade:

Today, climate change may be the public issue that best illustrates the chasm that sometimes separates conviction from persuasion.

Although the weight of scientific research attests to the fact that the earth is warming and that humans are responsible for a good bit of that warming, convincing people to accept this evidence and persuading them to act on it still doesn’t follow easily.

Then how does change occur?

Some theorists suggest that persuasion-understood as moving people to do more than nod in agreement-is best achieved via appeals to emotions such as fear, anger, envy, pride, sympathy, or hope.

We think that’s an oversimplication.

The fact is that persuasive arguments, whether in advertisements, political blogs, YouTube videos, tweets, or newspaper editorials, draw upon all the appeals of rhetoric (see p.24) to motivate people to act-whether it be to buy a product, pull a lever for a candidate, or volunteer for a civic organization.

Here, once again, is Camille Paglia driving home her argument that the 1984 federal law raising the drinking age in the United States to 21 was a catastrophic decision in need of reversal:

What this cruel 1984 law did is deprive young people of safe spaces where they could happily drink cheap beer, socialize, chat, and flirt in a free but controlled public environment.

Hence in the 1980s we immediately got the scourge of crude binge drinking at campus fraternity keg parties, cut off from the adult world.

Women in that boorish free-for-all were suddenly fighting off date rape.

Club drugs-Ecstasy, methamphetamine, ketamine (a veterinary tranquilizer)-surged at raves for teenagers and on the gay male circuit scene.

Paglia chooses to dramatize her argument by sharply contrasting a safer, more supportive past with a vastly more dangerous present when drinking was forced underground and young people turned to highly risky behaviors.

She doesn’t hesitate to name them either: binge drinking, club drugs, raves, and, most seriously, date rape.

This highly rhetorical, one might say emotional, argument pushes readers hard to endorse a call for serious action-the repeal of the current drinking age law.

Explain arguments aimed at winning

As this discussion suggests, in the politically divided and entertainment-driven culture of the United States today, the word argument may well call up negative images: the hostile scowl, belligerent tweet, or shaking fist of a politician or new pundit who wants to drown out other voices and prevail at all costs.

This winner-take-all view has a long history, but it often turns people off to the whole process of using reasoned conversation to identify, explore, and solve problems.

Hoping to avoid perpetual standoffs with people on “the other side,” many people now sidestep opportunities to speak their minds on issues shaping their lives and work.

We want to counter this attitude throughout this book: we urge you to examine your values and beliefs, to understand where they come from, and to voice them clearly ang cogently in arguments you make, all the while respecting the values and beliefs of others.

Some arguments, of course, are aimed at winning, especially those related to politics, business, and law.

Two candidates for office, for example vie for a majority of votes; the makers of one smartphone try to outsell their competitors by offering more features at a lower price; and two lawyers try to outwit each other in pleading to a judge and jury.

In appeal to a “judge” and “jury” (perhaps your instructor and classmates).

You might, for instance, argue that students in every field should be required to engage in service learning projects.

In doing so, you will need to offer better arguments or more convincing evidence than those with other perspectives-such as those who might regard service learning as a politicized or coercive form of education.

You can do so reasonably and responsibly, no name-calling required.

There are many reasons to argue and principled ways to do so.

We explore some of them in this section.

Rhetorical Appeals

Audiences are complicated and challenging, and you must attract and persuade large amounts of people with varying backgrounds.

“Used in the right way and deployed at the right moment, emotional, ethical, and logical appeals have enormous power [over audiences]” (22).

Pathos (Emotion), Logos (Logic), Ethos (Ethics), Kairos (Opportune Timing)

Emotional Appeals—> Pathos

Emotional appeals generate emotional responses-these responses can be fear, pity, love, anger, jealousy, joy, sympathy. etc.

This type of argument allows the writer or speaker to connect to their audience in a way that may lead them to accept a claim.

Ethical Appeals—> Ethos

Ethos appeals to credibility of speakers or writers (professional experience and character)

Character: When a speaker/writer comes across as trustworthy, fair, and respectable, audiences are far more likely to listen and accept arguments as true.

Professional Experience: When someone has the education, work history, resume, etc., to back up their claims, they have more ethos.

Logical Appeals—>Logos

Facts and Reason!

Facts: certain data, statistics, credible testimonies, clear examples.

Reason: the process of logic, rationality, sound reason.

The god of Opportunity—>Kairos

Kairos is the youngest son of Zeus: the god of opportunity.

“Seizing an opportunity,” also opportune timing for argument, is the most suitable time and place for making an argument.

“Be aware of your rhetorical moment to understand and take advantage of shifting circumstances and choose the best proofs of evidence for a particular place, situation, and audience” (29).

Arguments can be what kind of text? Explain.

As you know from your own experiences with social media, arguments are all around us, in every medium, in every genre, in everything we do.

There may be an argument on the T-shirt you put on in the morning, in the sports column you read on the bus, in the prayers you utter before an exam, in the off-the-cuff political remarks of a teacher lecturing, on the bumper sticker on the car in front of you, in the assurances of a health center nurse that “This won’t hurt one bit.”

The clothes you wear, the foods you eat, and the groups you join make nuanced, sometimes unspoken assertions about who you are and what you value.

So an argument can be any text-written, spoken, aural, or visual-that expresses a point of view.

In fact, some theorists claim that language is inherently persuasive.

When you say, “Hi, how’s it going?” in one sense you’re arguing that your hello deserves a response.

Even humor makes an argument when it causes readers to recognize-through bursts of laughter or just a faint smile-how things are and how they might be different.

More obvious as arguments are those that make direct claims based on or drawn from evidence.

Such writing often moves readers to recognize problems and to consider solutions.

Persuasion of this kind is usually easy to recognize:

The National Minimum Drinking Age Act, passed by Congress [in 1984], is a gross violation of civil liberties and must be repealed. It is absurd and unjust that young Americans can vote, marry, enter contracts, and serve in the military at 18 but cannot buy an alcoholic drink in a bar or restaurant.

-Camille Paglia, “The Drinking Age Is Past Its Prime”

We will become a society of a million pictures without much memory, a society that looks forward every second to an immediate replication of what it has just done, but one that does not sustain the difficult labor of transmitting culture from one generation to the next.

-Christine Rosen, “The Image Culture”

Intended readers

People writers hope and expect to address; you think about those readers and respond to their needs (Lunsford).

The book calls the ability to read between the lines—→_____________.

To become fact checkers, to practice what media critic Howard Rhiengold calls “crap detection”, and to read with careful attention./rhetoric

Arguments to Convince and Inform

We’re stepping into an argument ourselves in drawing what we hope is a useful distinction between convincing and-in the next section-persuading.

(Feel free to disagree with us!)

Arguments to convince lead audiences to accept a claim as true or reasonable-based on information or evidence that seems factual and reliable; arguments to persuade then seek to move people beyond conviction to action.

Academic arguments often combine both elements.

Many news reports and analyses, white papers, and academic articles aim to convince audiences by broadening what they know about a subject.

Such fact-based arguments might have no motives beyond laying out what the fact are.

Here’s an opening paragraph from a 2014 news story by Anahad O’Connor in the New York Times that itself launched a thousand arguments (and lots of huzzahs) simply by reporting the results of a recent scientific study:

Many of us have long been told that saturated fat, the type found in meat, butter and cheese, causes heart disease. But a large and exhaustive new analysis by a team of international scientists found no evidence that eating saturated fat increased heart attacks and other cardiac events.

-Anahad O’Connor, “Study Questions Fat and Heart Disease Link”

Wow.

You can imagine how carefully the reporter walked through the scientific data, knowing how this new information might be understood and repurposed by his readers.

Similarly, in a college paper on the viability of nuclear power as an alternative source of energy, you might compare the health and safety record of a nuclear plant to that of other forms of energy.

Depending upon your findings and your interpretation of the data, the result of your fact-based presentation might be to raise or alleviate concerns readers have about nuclear energy.

Of course, your decision to write the argument might be driven by your conviction that nuclear power is much safer than most people believe.

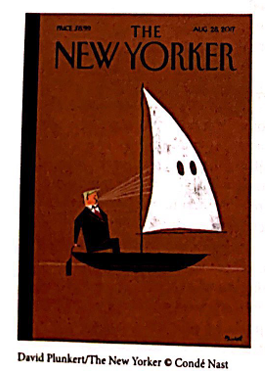

Today, images offer especially powerful arguments designed both to inform and to convince.

For example, David Plunkert’s cover art for the August 28, 2017, issue of the New Yorker is simple yet very striking.

Plunkert, who doesn’t involve himself with political subjects, said he was prompted to do so in response to what he saw as President Trump’s “weak pushback” against the hateful violence on exhibit in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 11, 2017: “A picture does a better job showing my thoughts than words do; it can have a light touch on a subject that’s extremely scary."

Arguments to Persuade

Today, climate change may be the public issue that best illustrates the chasm that sometimes separates conviction from persuasion.

Although the weight of scientific research attests to the fact that the earth is warming and that humans are responsible for a good bit of that warming, convincing people to accept this evidence and persuading them to act on it still doesn’t follow easily.

How then does change occur?

Some theorists suggest that persuasion-understood as moving people to do more than nod in agreement-is best achieved via appeals to emotions such as fear, anger, envy, pride, sympathy, or hope.

We think that’s an oversimplification.

The fact is that persuasive arguments, whether in advertisements, political blogs, YouTube videos, tweets, or newspaper editorials, draw upon all the appeals of rhetoric (see p. 24) to motivate people to act-whether it be to buy a product, pull a lever for a candidate, or volunteer for a civic organization.

Here, once again, is Camille Paglia driving home her argument that the 1984 federal law raising the drinking age in the United States to 21 was a catastrophic decision in need of reversal:

What this cruel 1984 law did is deprive young people of safe spaces where they could happily drink cheap beer, socialize, chat, and flirt in a free but controlled public environment.

Hence in the 1980s we immediately got the scourge of crude binge drinking at campus fraternity keg parties, cut off from the adult world.

Women in that boorish free-for-all were suddenly fighting off date rape.

Club drugs-Ecstasy, methamphetamine, ketamine (a veterinary tranquilizer)-surged at raves for teenagers and on the gay male circuit scene.

Paglia chooses to dramatize her argument by sharply contrasting a safer, more supportive past with a vastly more dangerous present when drinking was forced underground and young people turned to highly risky behaviors.

She doesn’t hesitate to name them either: binge drinking, club drugs, raves, and, most seriously, date rape.

This highly rhetorical, one might say emotional, argument pushes readers readers hard to endorse a call for serious action-the repeal of the current drinking age law.

Arguments to make decisions.

Closely allied to arguments to examine the options in important matters, both civil and personal–from managing out–of–controlled deficits to choosing careers.

Arguments to make decisions occur all the time in the public arena, where they are often slow to evolve, caught up in the electoral or legal squabbles, and yet driven by a genuine desire to find consensus.

In recent years, Americans have argued hard to make decisions about healthcare, the civil rights of same–sex couples, and the status of more than 11 million undocumented immigrants in the country.

Subjects so complex aren’t debated in straight lines.

They get haggled over in every imaginable medium by thousands of writers, politicians, and ordinary citizens working alone or via political organizations to have their ideas considered.

For college students, choosing a major can be an especially momentous personal decision, and one way to go about making that decision is to argue your way through several alternatives.

By the time you’ve explored the pros and cons of each alternative, you should be a little closer to a reasonable and defensible decision.

Sometimes decisions, however, are not so easy to make.

Arguments to Understand and Explore

Arguments to make decisions often begin as choices between opposing positions already set in stone.

But is it possible to examine important issues in more open–ended ways?

Many situations, again in civil or personal arenas, seem to call for arguments that genuinely explore possibilities without constraints or prejudices.

If there’s an “opponent” in such situations at all (often there is not), it’s likely to be the status quo or a current trend which, for one reason or another, puzzles just about everyone.

For example, in trying to sort through the extraordinary complexities of the 2011 budget debate, philosophy professor Gary Gutting was able to show how two distinguished economists–John Taylor and Paul Krugman–drew completely different conclusions from the exact same sets of facts.

Exploring how such a thing could occur led Gutting to conclude that the two economists were arguing from the same facts, all right, but they did not have all the facts possible.

Those missing or unknown facts allowed them to fill in the blanks as they could, thus leading them to different conclusions.

By discovering the source of a paradox, Gutting potentially open new avenues for understanding.

Exploratory arguments can also be personal, such as Zora Neale Hurston’s ironic exploration of racism and of her own identity in the essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me.”

If you keep a journal or blog, you have no doubt found yourself making arguments to explore issues near and dear to you.

Perhaps the essential argument in any such place is the writer’s realization that a problem exists–and that the writer or reader needs to understand it and respond constructively to it if possible.

Explorations of ideas that begin by trying to understand another’s perspective have been described as invitational arguments by researchers Sanja Foss, Cindy Griffin, and Josina Makau.

Such arguments are interested in inviting others to join in mutual explorations of ideas based on discovery and respect.

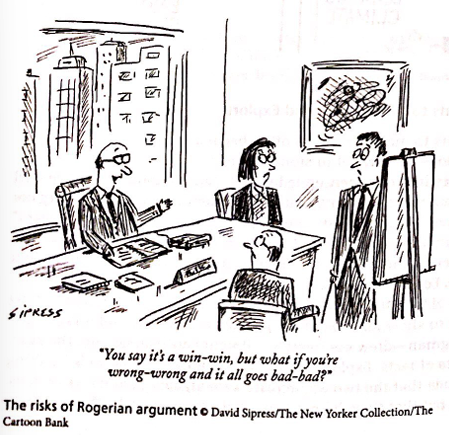

Another kind of argument, called Rogerian argument (after psychotherapist Carl Rogers), approaches audiences in similarly nonthreatening ways, finding common ground and establishing trust among those who disagree about issues.

Writers who take a Rogerian approach try to see where the other person is coming from, looking for “both/and” or win/win” solutions whenever possible.

(For more on Rogerian strategies, see Chapter 7.)

Occasions for Argument

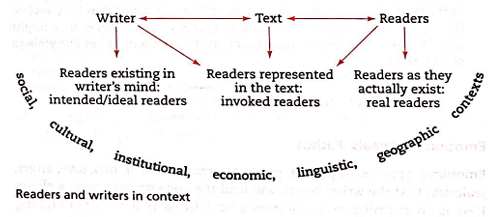

Texts usually have intended readers, the people writers hope and expect to address-let’s say, routine browsers of a newspaper’s op-ed page. Explain.

But writers also shape the responses of these actual readers in ways they imagine as appropriate or desirable-for example, maneuvering readers of editorials into making focused and knowledgeable judgements about politics and culture.

Such audiences, as imagined and fashioned by writers within their texts, are called invoked readers.

Making matters even more complicated, readers can respond to writers’ maneuvers by choosing to join the invoked audiences, to resist them, or maybe even to ignore them. Explain.

Arguments may also attract “real” readers from groups not among those that writers originally imagined or expected to reach.

You may post something on the Web, for instance, and discover that people you did not intend to address are commenting on it.

(For them, the experience may be like reading private email intended for someone else: they find themselves drawn to and fascinated by your ideas!)

As authors of this book, we think about students like you whenever we write: you are our intended readers.

But notice how in dozens of ways, from the images we choose to the tone of our language, we also invoke an audience of people who take writing arguments seriously.

We want you to become that kind of reader.