Animal Physiology Exam 4

1/99

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

100 Terms

Mechanoreceptors

Touch, pressure, proprioception | Ionotropic

Vestibular receptors

Balance; body position and movement | Ionotropic

Osmoreceptors

Osmotic pressure | Ionotropic

Auditory receptors

Sound | Ionotropic

Thermoreceptors

Heating and cooling | Ionotropic

Electroreceptors

Electric fields in water | Ionotropic

Some Taste Chemoreceptors; insects?

Salty and sour in vertebrates | Ionotropic

Some taste chemoreceptors

Sweet, bitter, and umami (proteinaceous) invertebrates | Metabotropic

Olfactory chemoreceptors

Chemicals generally from a distance | Metabotropic in vertebrates Ionotropic or mixed in insects

Photoreceptors

Light | Metabotropic

Magnetoreceptors

Position or change of magnetic field | Unknown

Glycolysis

•Glucose 6 Phosphate

–G6P

•Fructose 6 Phosphate

–F6P

•Fructose 1,6 Diphosphate

–F1,6BP

•Dihydroxy acetone phosphate

–DHAP

•Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate

–GAP

•1,3 diphosphoglyceric acid

–1,3 BPG

•3 diphosphoglyceric acid

–3 PG

•2 Diphosphoglyceric acid

–2 PG

•Phosphoenol pyruvic acid

–PEP

•Pyruvate Kinase

–PK

•Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase

–GAPDH

•Phosphoglycerate kinase

–PGK

•Pyruvate kinase

–PK

G6P

Glucose 6 Phosphate

F6P

Fructose 6 Phosphate

F1,6BP

•Fructose 1,6 Diphosphate

DHAP

•Dihydroxy acetone phosphate

GAP

•Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate

1,3 BPG

•1,3 diphosphoglyceric acid

3 PG

•3 diphosphoglyceric acid

2 PG

•2 Diphosphoglyceric acid

PEP

•Phosphoenol pyruvic acid

PK

•Pyruvate Kinase

GAPDH

•Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase

PGK

•Phosphoglycerate kinase

PK

•Pyruvate kinase

Principles of Energy Use in Animals

Energy Input: Enters the body as chemical energy from food.

Energy Output: Leaves the body as:

Heat: The primary output from metabolic inefficiencies and maintenance.

Chemical Energy: In exported organic matter (e.g., waste, growth).

External Work: Mechanical energy from movement.

Physiological Work

Absorbed chemical energy is used for:

Growth: Biosynthesis and accumulation of energy in body tissues.

Maintenance: Basic cellular functions.

Generation of External Work: Muscle contraction.

Body Size and Metabolic Demand

Inverse Relationship: Smaller animals have a higher metabolic rate per unit of body mass.

Example (Meadow Vole): Weighs 30g, eats 6x its body weight in a week.

Example (White Rhino): Weighs 1900kg, eats one-third its body weight in a week.

The Central Energy Pathway: Glycolysis

Location: Cytosol of the cell.

Oxygen Requirement: Does not require oxygen (anaerobic).

Process: Breaks down one glucose (6C) molecule into two pyruvic acid (3C) molecules.

Net ATP Gain: 2 ATP molecules (produces 4 ATP but consumes 2).

Key Enzymes & Intermediates:

Hexokinase & Phosphofructokinase (PFK): Key regulatory enzymes.

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH): Produces NADH.

Phosphoglycerate Kinase (PGK) & Pyruvate Kinase (PK): Produce ATP.

The Citric Acid Cycle (Krebs Cycle / TCA Cycle)

Location: Mitochondrial matrix.

Oxygen Requirement: Requires the presence of oxygen to run, but does not use it directly.

Process:

Each pyruvate is converted to Acetyl Coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA), producing 1 NADH and CO₂.

One cycle per Acetyl-CoA molecule.

Per Acetyl-CoA (Double for one glucose):

3 NADH

1 FADH₂

1 GTP (equivalent to ATP)

CO₂

The Electron Transport Chain (ETC) & Oxidative Phosphorylation

Location: Inner mitochondrial membrane.

Oxygen Requirement: Requires and uses oxygen. Oxygen is the final electron acceptor.

Process (Proton Pumping):

Electrons from NADH and FADH₂ are passed through four complexes (I-IV).

Energy from electron transfer pumps protons (H⁺) into the intermembrane space, creating a proton gradient.

Complex I: Accepts electrons from NADH. Moves 4 protons.

Complex II: Accepts electrons from FADH₂. Does not move protons.

Complex III & IV: Move more protons.

Total Proton Movement:

NADH: ~10 protons

FADH₂: ~6 protons

ATP Synthesis (Oxidative Phosphorylation)

ATP Synthase (Complex V): Protons flow back into the matrix through this enzyme, powering ATP production.

ATP Yield

NADH: ~2.5 ATP

FADH₂: ~1.5 ATP

Correction: In ETC diagrams, "2H" often represents electrons, not protons. Protons are pumped separately.

Uncoupling Protein 1 (UCP1) - Generating Heat

Function: Provides an alternative path for protons to flow back into the matrix, bypassing ATP synthase. This dissipates the proton gradient as heat instead of producing ATP.

Biological Purpose:

Thermoregulation: Found in brown fat (common in babies) to generate heat. Adults have more heat-insulating white fat.

Hibernation: Animals like polar bears use this to generate body heat while hibernating, when ATP demand is low.

Physiological Regulation: The body decides whether to send protons through ATP synthase (for ATP) or UCP1 (for heat) based on needs (e.g., cold exposure).

Anaerobic Conditions (No O₂)

Lactic Acid Metabolism

Scenario: During intense exercise when oxygen demand outstrips supply.

Process: Pyruvate from glycolysis is converted into lactic acid. This allows glycolysis to continue producing a small amount of ATP without oxygen.

Consequence: Lactic acid accumulation lowers pH in muscles, causing fatigue and pain.

Aerobic Conditions (O₂ Present)

Lactic Acid Metabolism

Process: Lactic acid can be converted back to pyruvate in the liver.

Fates of Pyruvate:

Gluconeogenesis: Carbon chains are used to rebuild glucose/glycogen stores.

Oxidation: Enter the Krebs Cycle and ETC to produce ATP, CO₂, and H₂O.

Short-Term, High-Intensity Exercise (e.g., 100m dash)

Fuel Sources During Exercise

Primarily uses ATP from anaerobic glycolysis (muscle glycogen and glucose).

Medium-Duration Exercise (e.g., 800m run)

Fuel Sources During Exercise

Uses a mix of anaerobic glycolysis and aerobic catabolism of glycogen/glucose.

Long-Term, Low-Intensity Exercise (e.g., 10,000m run)

Fuel Sources During Exercise

Glycogen stores are depleted.

The body relies almost exclusively on aerobic catabolism using lipids (fatty acids).

Fuel Sources During Exercise Insight

To reduce body fat percentage, low-intensity exercise for an extended duration is more effective than short, high-intensity bursts. The X-axis on fuel-use graphs is time, not distance.

Oxygen Deficit

At the start of exercise, the body's oxygen uptake lags behind the theoretical demand. The body covers this deficit using anaerobic pathways, leading to lactic acid buildup.

EPOC (Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption)

“Oxygen Debt”

After exercise, oxygen consumption remains elevated to:

"Repay" the oxygen deficit.

Convert lactic acid back to pyruvate.

Replenish ATP and oxygen stores.

This is why you continue to breathe heavily after you stop exercising.

Introduction to the Reproductive System

Core Purpose & Unique Characteristics

Sole Function: To pass genetic material to the next generation.

Distinct from Urinary System: Interconnected but not dependent.

Resource-Dependent: Functions optimally only when the body senses ample nutrients and resources. Reproduction is suppressed during starvation or stress.

Long Development: Takes from birth until puberty to become fully functional, unlike other organ systems.

Requirements for Successful Reproduction

Gamete Meeting: Egg and sperm must meet, requiring correct environmental cues, developed organs, resources, attraction, and successful mating.

Viable Offspring: Requires zygote development, provisioning for the offspring, proper early epigenetics, and evading predators.

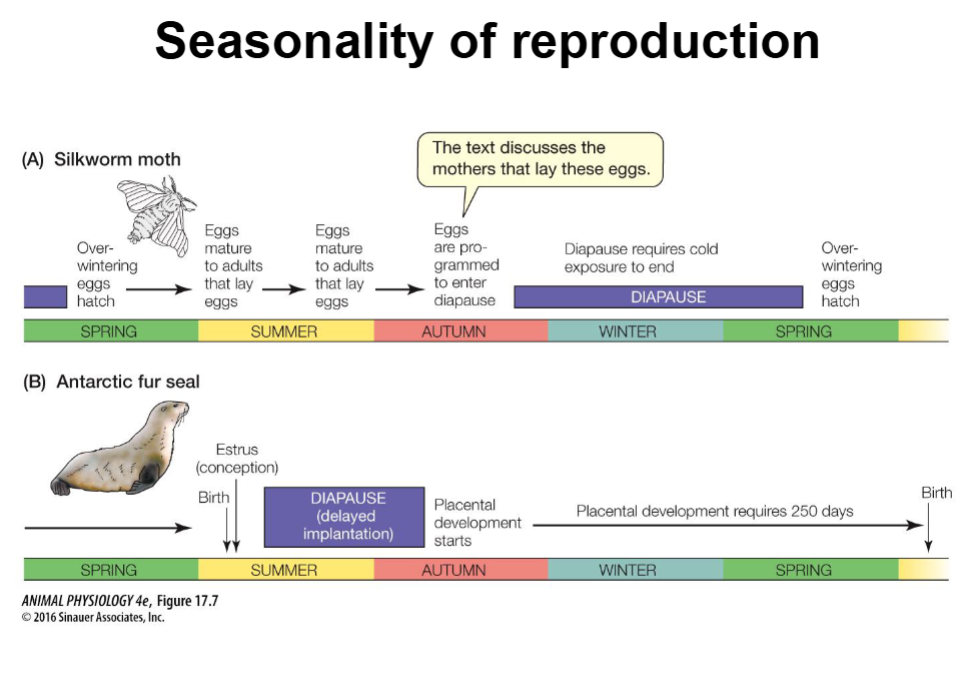

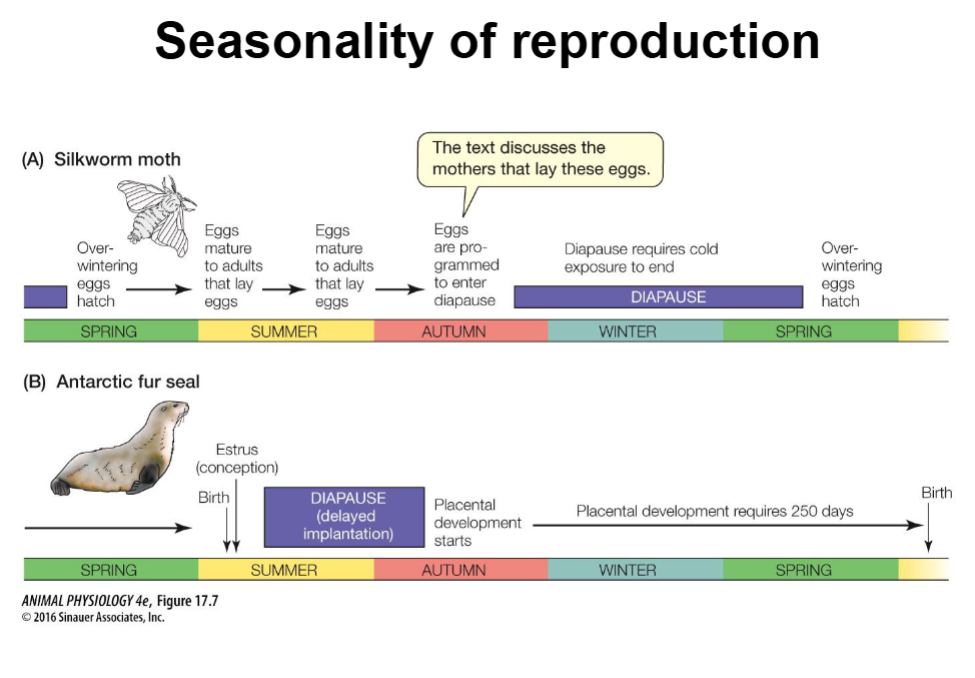

Seasonality and Environmental Cues

Migration: Many species (birds, herds) migrate to follow resources (food, warmer temperatures) for successful breeding.

Diapause: A state of suspended development (e.g., silkworm moth eggs require winter cold to trigger epigenetic changes for hatching).

Delayed Implantation: Some animals conceive but delay embryo implantation to ensure birth occurs in resource-rich spring/summer.

Overarching Principle: Reproduction is timed to ensure access to resources for the offspring.

Sexual Development

Default State: In the absence of specific genetic triggers, the female reproductive structure is the default developmental pathway.

Male Development: Requires the activation of a specific set of genes.

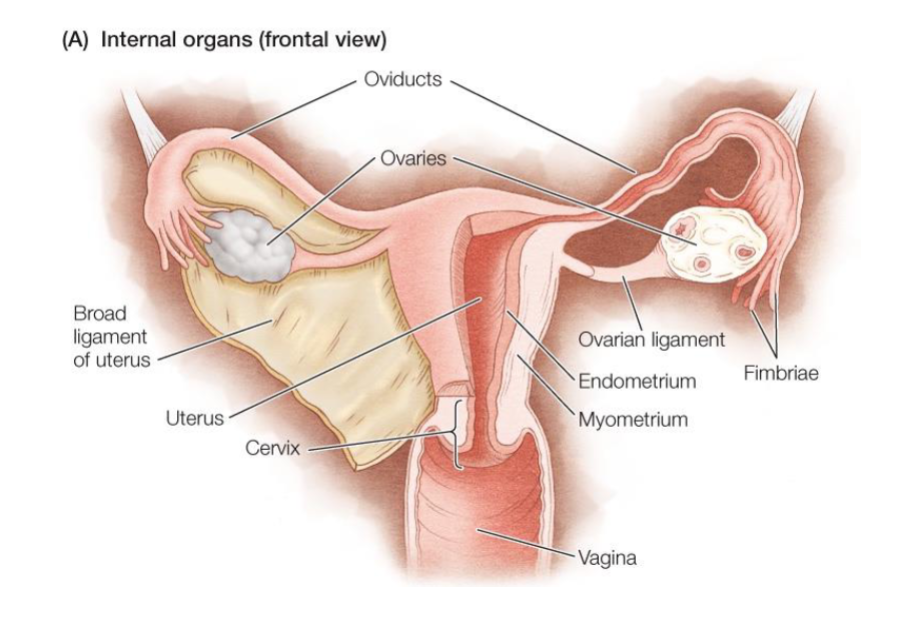

Basic Female Reproductive Anatomy (From Outside to Inside)

Vagina: External orifice.

Cervix: Muscular opening to the uterus.

Uterus: Where the embryo must implant for a viable pregnancy. Implantation elsewhere (e.g., oviduct) is dangerous and non-viable.

Oviducts (Fallopian Tubes): Site of fertilization.

Ovaries: Produce and house the follicles (eggs).

The Ovarian Reserve & Follicle Development

Ovarian Reserve: The total number of primordial follicles is fixed during fetal development. This number is set for life and cannot be replenished.

Impact of Environment: Toxins exposure during a mother's pregnancy can damage the developing fetus's ovarian reserve, affecting future fertility.

Puberty Trigger: The primary driver is nutrition. High-nutrient diets are linked to earlier puberty onset.

Modern Concern: Earlier puberty + later age of childbearing = potential for a diminished quality ovarian reserve when individuals are ready to have children.

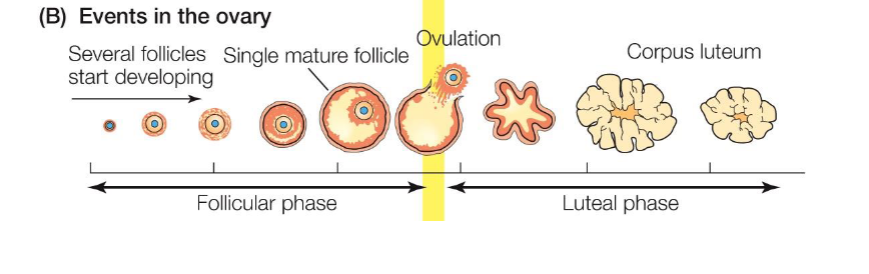

The Menstrual/Ovarian Cycle

Primordial Follicles: The fixed pool of dormant follicles.

Activation (Epigenetic Change): Each cycle, a group of primordial follicles is activated to become Primary Follicles.

Selection: From the primary follicles, a few are selected to become Secondary Follicles, and finally, one (or more, species-dependent) becomes a Mature Follicle. Selection is influenced by spatial location in the ovary and hormone exposure.

Ovulation: The mature follicle releases its egg (a secondary oocyte).

Fate of Unselected Follicles: All non-recruited follicles undergo apoptosis (cell death). A fresh batch is selected in the next cycle.

Corpus Luteum Formation: The ruptured follicle becomes the corpus luteum.

Corpus Luteum & Early Pregnancy

If NO Pregnancy Occurs: The corpus luteum degenerates via apoptosis.

If Pregnancy Occurs:

The fertilized embryo implants in the uterus.

The implanted embryo secretes hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin).

hCG signals the corpus luteum to persist and produce progesterone.

Progesterone provides critical hormonal support to maintain the early pregnancy until the placenta takes over.

Complexity of Reproduction

Reproduction is a multi-faceted process involving numerous steps for success:

Pre-Fertilization: Monitoring environmental cues, relocation, organ development, resource acquisition, mate attraction, and spawning/copulation.

Post-Fertilization: Zygote development, offspring provisioning, epigenetic tagging, parental time investment, confronting environmental stresses, and predator evasion.

The ultimate goal is the production of successful offspring.

Components of Reproduction

(A) Mate Association: Males and females find each other, often via pheromones (e.g., blue crabs).

(B) Annual Reproductive Cycle: Timing is crucial, often controlled by photoperiod and hormones like melatonin and testosterone (e.g., deer antler growth).

(C) Functions of Organs & Cells: Specific structures have dedicated roles (e.g., ovarian follicles secrete estrogens to prepare for pregnancy).

(D) Reproductive Coordination & Control: Post-ejaculation biochemical changes (capacitation) are needed for sperm to fertilize effectively.

(E) Provisioning of Offspring: Parents expend energy to feed their young (e.g., terns catching fish).

(F) Distinctive Physiology of Young: Offspring may have completely different forms and functions from adults (e.g., aquatic, gill-breathing damselfly larvae vs. terrestrial adults).

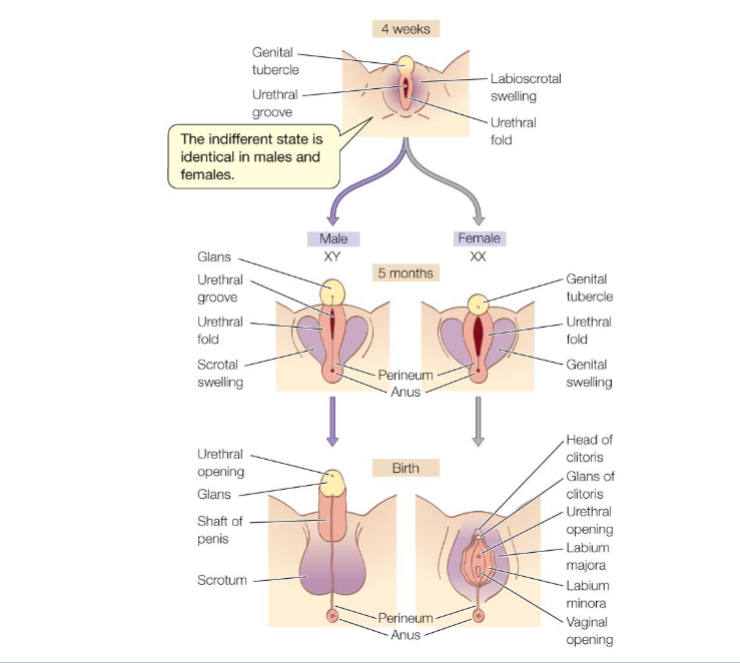

Sex Determination & Differentiation

Sex Determination: The process of establishing an individual's biological sex. It's often genetically based (e.g., XX/XY in mammals) but can be more complex and is influenced by epigenetics and environmental factors.

Differentiation of External Genitalia: Males and females start from an identical "indifferent state" in the womb. Hormonal signals (primarily androgens like testosterone) then drive the development of either male or female external genitalia.

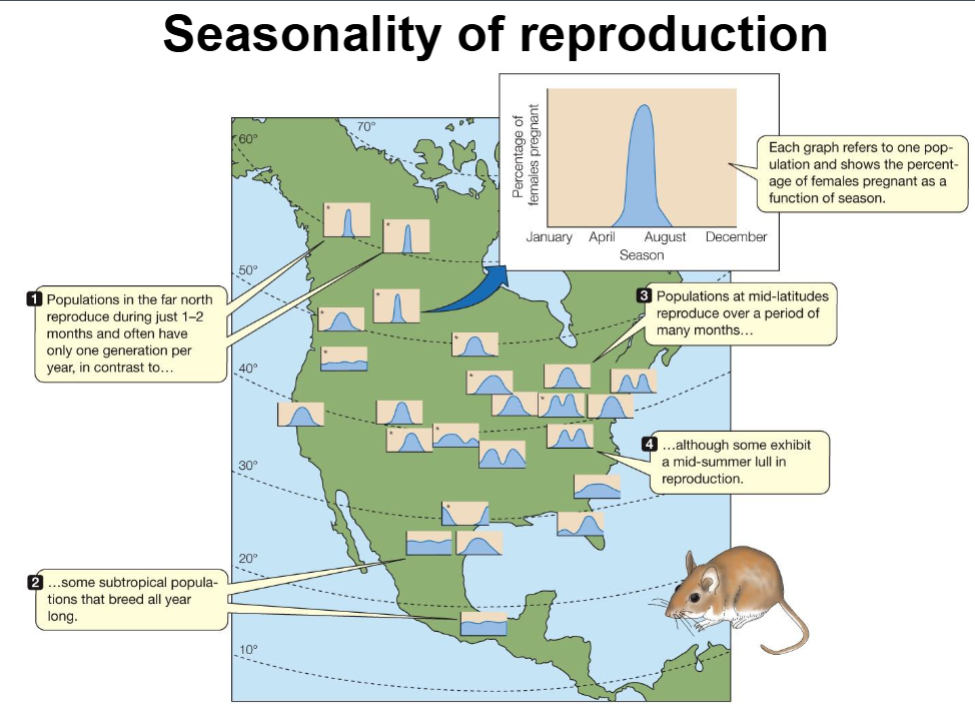

Seasonality of Reproduction

Reproduction is often timed to maximize offspring survival, leading to seasonal patterns.

Far North: Short, intense reproductive window (1-2 months), often one generation per year.

Subtropics: Can breed year-round.

Mid-Latitudes: Extended reproductive period, sometimes with a mid-summer lull.

Examples:

Silkworm Moth: Uses diapause (a dormant state) to overwinter as eggs, requiring cold exposure to resume development.

Antarctic Fur Seal: Employs delayed implantation (embryonic diapause), where the embryo's development is paused after conception to time birth for a favorable season.

Anatomy

Internal Organs: Ovaries, Oviducts (Fallopian Tubes), Uterus (with Endometrium and Myometrium), Cervix, Vagina.

Support Structures: Broad ligament, Ovarian ligament.

The Ovary & Folliculogenesis:

Ovarian Reserve: The finite number of primordial follicles a female is born with. This is the rule for most mammals (exceptions like zebrafish exist).

Follicle Development: Primordial → Primary → Secondary → Mature (Graafian) Follicle.

Ovulation: The mature follicle ruptures, releasing a secondary oocyte.

Corpus Luteum: The ruptured follicle transforms into this structure, which secretes progesterone.

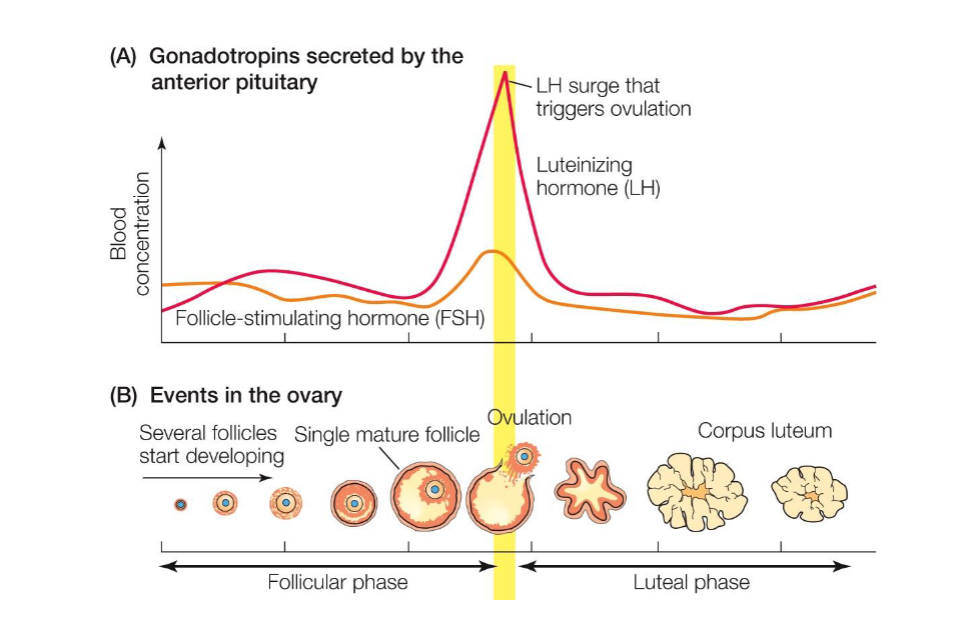

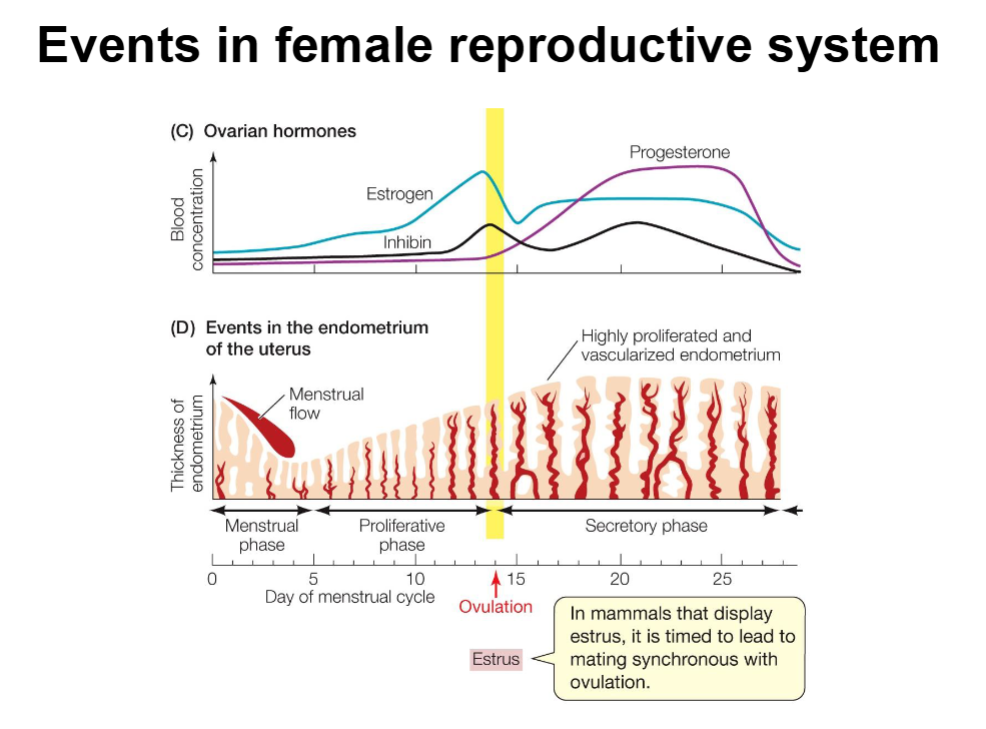

The Menstrual / Estrous Cycle

Key Distinction: The menstrual cycle (humans, some primates) involves the shedding of the endometrial lining (menstruation). The estrous cycle (most other mammals) involves reabsorption of the lining and females only mate when in "heat" or estrus.

Hormonal Control & Phases

The cycle is orchestrated by hormones from the Hypothalamus (GnRH), Anterior Pituitary (FSH, LH), and Ovaries (Estrogen, Progesterone).

Follicular Phase

FSH rises, stimulating a cohort of follicles to develop.

One follicle becomes dominant by producing more FSH/LH receptors.

Estrogen rises gradually, produced by granulosa cells via the "2-Cell Model":

LH stimulates theca cells to produce androgens.

FSH stimulates granulosa cells to convert androgens to estrogen using the enzyme aromatase.

Rising estrogen stimulates proliferation of the endometrium (Proliferative Phase).

Inhibin is secreted, which inhibits FSH to prevent other follicles from developing.

Ovulation

A surge in Estrogen triggers a massive LH surge from the pituitary.

The LH surge triggers ovulation (~24-36 hours later).

Luteal Phase

The ruptured follicle becomes the Corpus Luteum.

The Corpus Luteum secretes Progesterone and some estrogen.

Progesterone transforms the endometrium into a secretory state, making it highly vascularized and ready for embryo implantation.

If no pregnancy occurs, the Corpus Luteum degenerates, progesterone falls, and the endometrial lining is shed (Menstrual Phase).

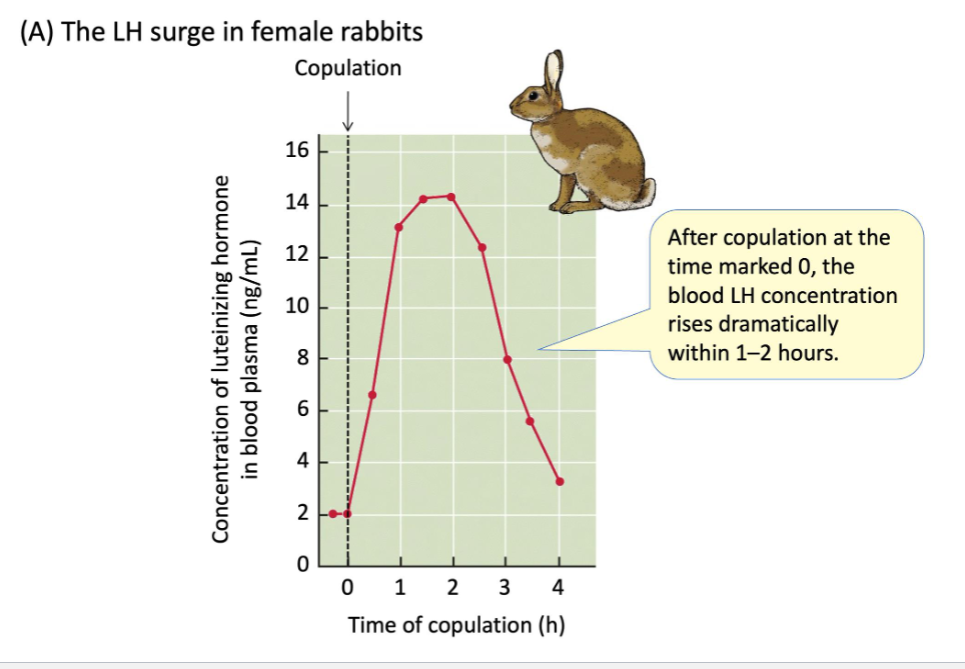

Induced vs. Spontaneous Ovulation

Spontaneous Ovulation (Humans): The LH surge and ovulation occur cyclically without the need for copulation.

Induced Ovulation (Rabbits, Cats, many domestic animals): Copulation provides the sensory stimulus that triggers the neuroendocrine pathway leading to the GnRH and LH surges, causing ovulation. This ensures ovulation is timed with mating.

The Rabbit Model (A Key Example of Induced Ovulation)

The Stimulus: Female rabbits show estrus-like behaviors and will allow copulation. The physical act of copulation is the critical trigger.

The Neuroendocrine Pathway:

Sensory Activation: Copulation stimulates sensory neurons in the cervix and vagina.

Signal to Brain: These neurons send impulses to the brainstem, which then stimulates the hypothalamus via norepinephrine.

GnRH Release: The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

LH Surge: GnRH travels to the anterior pituitary, causing a massive, rapid release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH).

Ovulation: The LH surge travels in the blood to the ovaries and triggers ovulation within hours.

Biological Significance: This mechanism ensures that ovulation and fertilization are perfectly synchronized. It prevents the "waste" of ovulating an egg if no male is present. In species like cats, this also allows a single litter to be fathered by multiple males.

Male Anatomy

Testes: Located in the scrotum for temperature regulation (essential for spermatogenesis). Produce sperm and testosterone (from Leydig cells).

Sperm Pathway: Testes → Epididymis (maturation) → Vas Deferens.

Accessory Glands:

Seminal Vesicles & Prostate Gland: Produce the bulk of semen, which provides nutrients and a conducive environment for sperm.

Bulbourethral Glands: Secrete a pre-ejaculate mucus.

Sperm vs. Semen: Sperm are the male gametes; semen is the fluid that carries and supports them.

Sperm Structure

Head: Contains the nucleus (DNA) and the acrosome (enzyme-filled cap crucial for fertilization).

Midpiece: Packed with mitochondria to provide energy for movement.

Tail (Flagellum): Propels the sperm.

Testicular Activity Timeline

A prenatal testosterone surge drives somatic sex differentiation.

Activity is low during childhood.

At puberty, rising testosterone drives sperm production and secondary sexual characteristics.

Males do not have a "gamete reserve" and can produce sperm throughout life, unlike the female ovarian reserve.

Hormonal Axis: Hypothalamus (GnRH) → Anterior Pituitary (LH, FSH) → Testes.

LH stimulates Leydig cells to produce Testosterone.

FSH (with Testosterone) supports Sertoli cells in spermatogenesis.

Testosterone is required for sperm mitosis/meiosis and exerts negative feedback on the hypothalamus/pituitary.

Inhibin from Sertoli cells inhibits FSH.

Testes Size & Mating Systems

In multi-male mating systems (where sperm competition is high), males have evolved relatively larger testes to produce more sperm and increase reproductive success.

In single-male mating systems, testes size is smaller relative to body size.

The Journey to Fertilization

Sperm Arrival: Many sperm arrive at the secondary oocyte, surrounded by granulosa cells and the zona pellucida.

Acrosomal Reaction: The sperm head binds to species-specific receptors on the zona pellucida. This triggers the release of acrosomal enzymes, allowing the sperm to digest a path through the zona.

Sperm-Oocyte Fusion: The sperm crosses the perivitelline space. Proteins on the sperm (Izumo1) bind with proteins on the oocyte (Juno).

Block to Polyspermy: Upon fusion, the oocyte becomes impermeable to other sperm, ensuring only one sperm fertilizes the egg.

Zygote Formation: The sperm releases its genetic material into the oocyte, forming a zygote.

Hormonal Support of Pregnancy

After fertilization, the developing embryo secretes Chorionic Gonadotropin (CG - e.g., hCG in humans).

CG rescues the Corpus Luteum, preventing it from degenerating.

The Corpus Luteum continues to secrete Progesterone and Estrogen, which are essential for maintaining the pregnancy.

If pregnancy occurs, these hormone levels remain high. If not, they plummet, leading to menstruation.

The post-partum drop in estrogen and progesterone can contribute to post-partum depression.

Birth (Parturition)

Birth is a positive feedback loop.

The fetus, pushing against the cervix, stimulates mechanoreceptors.

This signal is sent to the hypothalamus, which stimulates the posterior pituitary to release Oxytocin.

Oxytocin stimulates powerful uterine (myometrial) contractions.

Contractions force the fetus further down, stimulating more mechanoreceptors, leading to more oxytocin release—a cycle that continues until birth.

Oxytocin also stimulates the release of prostaglandins, which further strengthen contractions.

Costs of Reproduction & Lactation

Energetic Costs

The most energy-demanding period for a mother is lactation, not pregnancy. Energy intake peaks during nursing to support milk production.

Mammary Glands & Lactation

Structure: Composed of alveoli (milk-producing sacs), milk ducts, and a teat/canal.

Hormonal Control (Another Positive Feedback Loop):

Suckling by the young provides the sensory stimulus.

This signal inhibits Dopamine and increases TRH, leading the Anterior Pituitary to release Prolactin.

Prolactin stimulates alveolar epithelial cells to produce milk.

The signal also causes the Posterior Pituitary to release Oxytocin.

Oxytocin causes myoepithelial cells surrounding the alveoli to contract, ejecting milk into the ducts (the "let-down" reflex).

Ionotropic Transduction

Mechanism: The stimulus (e.g., a chemical, pressure) directly binds to and opens an ion channel on the sensory receptor cell.

Effect: Ions (e.g., Na+, K+) flow directly across the membrane, leading to rapid depolarization and generation of an action potential. This is a fast and simple system.

Examples: Mechanoreceptors (touch, pressure, vibration), Vestibular receptors (balance), Auditory receptors (sound), Thermoreceptors (heat/cold), Electroreceptors, and taste receptors for Salty and Sour.

Metabotropic Transduction

Mechanism: The stimulus binds to a receptor that is coupled to a G-protein. This activates an intracellular second messenger system (e.g., cyclic AMP, IP3).

Effect: The second messenger cascade can then open ion channels. This process is slower but allows for significant signal amplification and complex regulation.

Examples: Taste receptors for Sweet, Bitter, and Umami, Olfactory (smell) receptors, and Photoreceptors (vision).

General Principles of Senses

Each sense (vision, hearing, smell, taste) has dedicated receptor cells and independent neural pathways to the brain.

Information from different senses is processed in distinct regions of the brain.

Some senses (taste, vision, hearing) have local ganglia for rapid, local processing, while others (touch, smell) send signals directly to the CNS.

The Labeled-Lines Principle

Each sensory modality (vision, hearing, etc.) has its own dedicated receptor cells and independent neural pathways to the brain.

Action potentials from each type of receptor are fundamentally similar, but the brain interprets them differently based on which "line" they arrive on.

Example: Action potentials from the optic nerve are always interpreted as light, while those from the auditory nerve are always interpreted as sound, even if the stimulus is different.

These pathways can interact in the brain (e.g., smell influences taste), but the loss of one sense does not eliminate the others.

The Insect Model: A Simple Mechanoreceptor

Structure: A bristle shaft is connected to supporting cells and a sensory neuron at its base.

Function: Displacement of the bristle (by wind, touch, etc.) deforms the cell membrane of the sensory neuron.

Coding Stimulus Intensity & Duration: The nervous system encodes information through two key variables:

The Amplitude of the Receptor Potential: A stronger stimulus produces a larger depolarization (receptor potential).

The Frequency of Action Potentials: A larger receptor potential (from a more intense or rapidly changing stimulus) leads to a higher frequency of action potentials being sent to the CNS.

Mammalian Skin Mechanoreceptors

The skin contains multiple specialized receptors that provide a detailed "map" of tactile information.

Pacinian Corpuscle: Located deep in the dermis. senses Vibration. It is an extremely phasic receptor.

Ruffini Ending: Located in the dermis. senses Pressure. It is a tonic receptor.

Meissner's Corpuscle: Located close to the skin surface in the dermis. senses Light Touch. It is a phasic receptor.

Merkel Disc: Located at the border of the epidermis and dermis. senses Touch and Pressure. It is a tonic receptor.

Free Nerve Endings: Located throughout the skin. sense Pain, Itch, and Temperature.

Tonic Receptors (Merkel Disc, Ruffini Ending)

Fire action potentials continuously throughout a prolonged stimulus.

They signal the presence and duration of a stimulus.

The firing frequency can change with stimulus intensity (e.g., Merkel discs fire more during increasing pressure).

Phasic Receptors (Meissner's Corpuscle)

Fire action potentials primarily at the beginning and end of a stimulus.

They signal the change in a stimulus.

They adapt quickly and stop firing if the stimulus remains constant.

Extremely Phasic Receptors (Pacinian Corpuscle)

Fire action potentials only at the exact moment of a change (e.g., the onset of vibration).

They are exquisitely sensitive to rapid changes in the stimulus.

Central Nervous System Processing

The raw data from these receptors is sent to the somatosensory cortex.

The CNS can habituate to constant stimuli (e.g., the feeling of clothes on your skin), even if the tonic receptors are still firing. It prioritizes new or changing information for conscious attention.

Outer Ear

Pinna: The external ear; funnels sound waves into the auditory canal.

Auditory Canal: Channels sound to the tympanic membrane.

Middle Ear

Tympanic Membrane (Eardrum): Vibrates in response to sound waves.

Ossicles (Malleus, Incus, Stapes): Three tiny bones that amplify and transmit vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear. The stapes footplate sits in the Oval Window.

Inner Ear

Cochlea: A fluid-filled, spiral-shaped organ where sound is transduced.

Vestibular System (Semicircular Canals, Utricle, Saccule): Responsible for balance (detecting head rotation and linear acceleration).

How Hearing Works: A Journey from Air to Electricity

Sound Collection & Amplification: Sound waves are funneled by the pinna, strike the tympanic membrane, and are mechanically amplified by the ossicles.

Fluid Motion: The stapes vibrates against the oval window, creating pressure waves in the fluid (perilymph) inside the cochlea.

Frequency Analysis by the Basilar Membrane

Transduction by Hair Cells

Frequency Analysis by the Basilar Membrane

The Basilar Membrane runs the length of the coiled cochlea. It is stiff and narrow at the base (near the oval window) and wide and flexible at the apex (the tip).

This gradient means different frequencies cause maximal vibration at different points along the membrane.

High-frequency sounds peak near the base.

Low-frequency sounds travel further and peak near the apex.

Transduction by Hair Cells

Sitting on the basilar membrane is the Organ of Corti, which contains hair cells—the actual sensory receptors.

The stereocilia ("hairs") of these cells are embedded in an overlying tectorial membrane.

When the basilar membrane vibrates, the hair cells shear against the tectorial membrane, bending the stereocilia.

This bending opens mechanically-gated ion channels, depolarizing the hair cell and causing the release of neurotransmitters.

This signal is sent to the brain via the cochlear nerve.

Key Concepts in Auditory Processing

The Cochlear Amplifier: In living cochleas, the response of the basilar membrane is significantly sharpened and amplified by the active, motile properties of the outer hair cells, leading to better frequency resolution and sensitivity.

Sound Localization: The brain determines the location of a sound by comparing:

Timing Differences: When a sound reaches the left vs. right ear.

Intensity Differences: The slight difference in loudness between the two ears.

Hearing Ranges: Different mammals hear different frequency ranges. Humans (~20 Hz - 20 kHz) are in the middle of the spectrum. Bats and dolphins use very high-frequency sounds (ultrasound) for echolocation, while elephants use very low-frequency sounds (infrasound) for long-distance communication.

Comparative Anatomy: Insects use a tympanal organ, a membrane with air sacs and sensory neurons, to detect sound.

Debunking the Tongue Map

The old "tongue map" showing specific zones for sweet, sour, salty, and bitter is incorrect.

All five basic tastes (Sweet, Salty, Sour, Bitter, Umami) can be detected by receptors all over the tongue.

The density of specific receptors can vary by region and by individual, leading to differences in taste sensitivity.

Anatomy of Taste

Papillae: The small bumps on the tongue. They come in several types (e.g., fungiform, circumvallate) and contain taste buds.

Taste Buds: Clusters of 50-150 taste receptor cells, located within the papillae.

Taste Receptor Cells: These cells have microvilli that project into a taste pore, where they contact tastants (chemicals in food). They synapse with sensory neurons at their base.

Anatomy of Smell

Olfactory Epithelium: A patch of specialized tissue high in the nasal cavity containing olfactory receptor cells. These are true neurons and the only neurons known to be replaced throughout life.

Olfactory Receptor Cells: Bipolar neurons with cilia that project into the mucus layer. The cilia contain the odorant receptor proteins.

Olfactory Bulb: The structure at the front of the brain where the axons of the olfactory receptor cells converge.

Glomeruli: Spherical structures in the olfactory bulb where the axons of receptor cells expressing the same odorant receptor converge, synapsing with mitral cells.

Olfactory Signal Transduction

Mechanism: Metabotropic.

An odorant molecule binds to a specific G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) on the cilia of an olfactory receptor cell.

This activates a G-protein (G_olf), which in turn activates the enzyme adenylyl cyclase.

Adenylyl cyclase produces cyclic AMP (cAMP).

cAMP binds to and opens cation channels (Na+, Ca2+), leading to depolarization.

The incoming Ca2+ also opens Ca2+-activated Cl- channels, causing Cl- to flow out of the cell, further depolarizing it and amplifying the signal.

The Vomeronasal Organ (VNO or Jacobson's Organ)

An accessory olfactory organ found in many terrestrial vertebrates (e.g., mice, cats, snakes).

It is located in the nasal cavity or palate and detects non-volatile chemical signals (pheromones), which often convey social and reproductive information.

It has its own neural pathway to the brain (accessory olfactory bulb) and uses a similar but distinct metabotropic transduction pathway (often involving the G-protein G_o and IP3).

The Basic Principle of Vision

Vision depends on light from a source reflecting off objects and entering the eye.

The eye is a biological camera that focuses this light onto a sheet of photoreceptor cells.

What an animal "sees" is determined by the structure and capabilities of its visual system (types of photoreceptors, lens quality, neural processing), not by the external world itself.

Evolution and Diversity of Eyes

The gene Pax6 is a master control gene that initiates eye development across a wide range of animal lineages.

Eyes have evolved independently multiple times, but all use the same basic building blocks:

Photoreceptor Cells: Cells containing light-sensitive pigments.

Pigment Cells: To block light and allow directional sensing.

A Lens: To focus light (in more complex eyes).

Examples range from simple eyespots in flatworms to the compound eyes of insects (made of many ommatidia) to the single-lens camera eyes of vertebrates and cephalopods (like squid and octopus).

The Photopigments: Rhodospin

The key photopigment in most animal eyes is rhodopsin.

It consists of a protein called opsin and a light-absorbing molecule derived from Vitamin A called retinal.

The Molecular Basis of Sight:

In the dark, retinal is in the 11-cis form.

When a photon of light is absorbed, retinal instantly isomerizes (changes shape) to the all-trans form.

This shape change causes the opsin protein to change its conformation, activating it. This activated opsin is called metarhodopsin II.

Anatomy of the Mammalian Eye

Cornea & Lens: Focus incoming light onto the retina. The lens changes shape (accommodation) to focus on near or far objects.

Retina: The light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye. It contains the photoreceptor cells and neural circuitry.

Fovea: A small, central region of the retina packed with cone photoreceptors. It is responsible for high-acuity (sharp) and color vision. The lens focuses light precisely here.

Optic Nerve: Carries visual information from the retina to the brain.

Photoreceptors: Rods and Cones

Rods:

Function: Vision in dim light (scotopic vision).

Sensitivity: Very high; can respond to a single photon.

Location: Spread throughout the retina, but absent from the fovea.

Acuity: Low; many rods converge on a single neuron, providing sensitivity but poor detail.

Color Vision: None; only one type of rod pigment.

Cones:

Function: Vision in bright light (photopic vision) and color vision.

Sensitivity: Low; require bright light to activate.

Location: Highly concentrated in the fovea.

Acuity: High; often a one-to-one connection with neurons, providing high detail.

Color Vision: Yes; three types of cones in humans, each with a different opsin sensitive to short (S/blue), medium (M/green), or long (L/red) wavelengths.

Phototransduction: The "Dark Current"

This is a unique system where light inhibits the receptor cell.

In the DARK (Depolarized State):

Cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels in the photoreceptor outer segment are high.

cGMP binds to and keeps cGMP-gated Na+ channels OPEN.

Na+ flows in, depolarizing the cell. This is called the "dark current."

In this depolarized state, the photoreceptor continuously releases the neurotransmitter glutamate.

In the LIGHT (Hyperpolarized State):

Light isomerizes retinal, activating rhodopsin.

Activated rhodopsin triggers a G-protein (transducin) cascade.

This cascade activates an enzyme (PDE) that breaks down cGMP.

cGMP levels drop.

The cGMP-gated Na+ channels CLOSE.

The "dark current" stops, and the cell hyperpolarizes (its membrane potential becomes more negative).

This hyperpolarization reduces the release of glutamate.

This reduction in neurotransmitter release is the signal that light has been detected, which is then processed by the complex neural network of the retina (bipolar cells, ganglion cells) before being sent to the brain via the optic nerve.