FINAL JAPANESE ART HISTORY FLASHCARDS

1/257

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

258 Terms

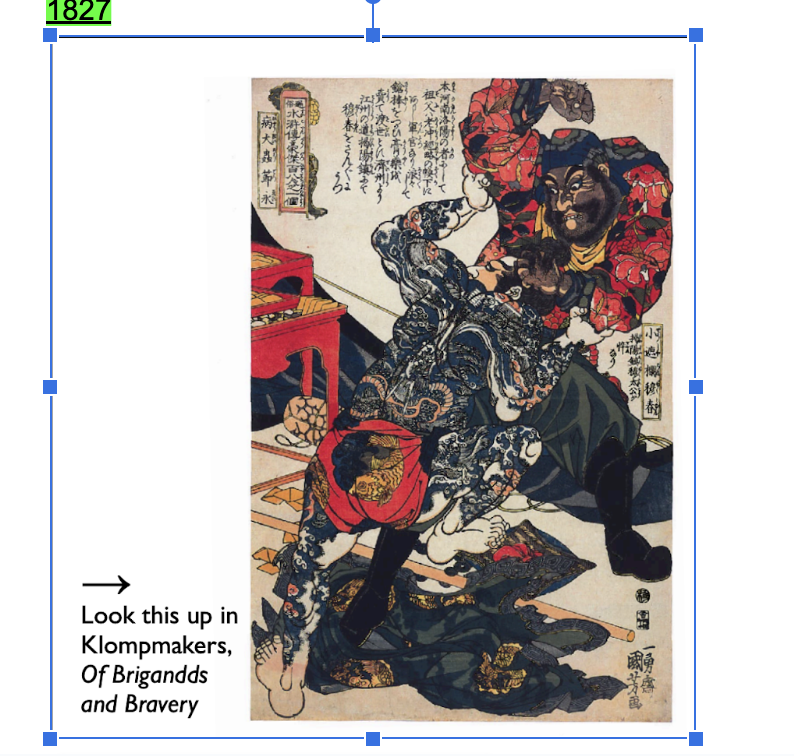

#1) Setsuei (The Sick Tiger) Series: 108 Heroes of the Suikōden

Period: Edo Period

Materials: Woodblock print on washi (mulberry paper)

-Ukiyo-e style

-Use of dramatic action, vibrant color, and expressive detail

Series: 108 Heroes of the Suikōden (The Water Margin)

aArtist: Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Date: 1827

Period: Edo Period (Tokugawa Japan)

Shows a muscular warrior crouched in a tense, dynamic pose beside a weakened tiger.

Bold black outlines, expressive linework, dramatic gestures, and carefully stylized anatomy.

The landscape background is flattened and symbolic, not realistic.

The composition is full of motion and narrative tension, evoking action and inner strength.

#1) Materials and Technique

-Woodblock print on washi (mulberry paper)

-Ukiyo-e style

-Use of dramatic action, vibrant color, and expressive detail

#1) Historical Significance

Reflected social frustrations under strict Tokugawa rule.

Helped launch Kuniyoshi’s fame and popularity of warrior prints

Served as moral inspiration during a time of rigid social order.

#1) Social Aspects

Audience: Urban commoners (chōnin) — merchants, artisans, townspeople.

Admired heroes who resisted injustice — appealed to those excluded from power

Functioned as both entertainment and a form of ethical storytelling.

#1) Political Aspects

Heroes portrayed as righteous rebels, critiquing Tokugawa authroity

based on foreign (Chinese) source to avoid censorship.

#1) Technological Aspects

High-level woodblock print technology:

Part of the Edo period’s mass production of affordable art.

Innovations in figure movement, drama, and visual storytelling.

#1) Review:

Focus on Kuniyoshi’s role in popularizing Suikōden in Japan.

Link between Chinese narrative + Japanese values.

Think about how art expresses social and political tensions in coded ways.

Know how Ukiyo-e functioned technically and culturally.

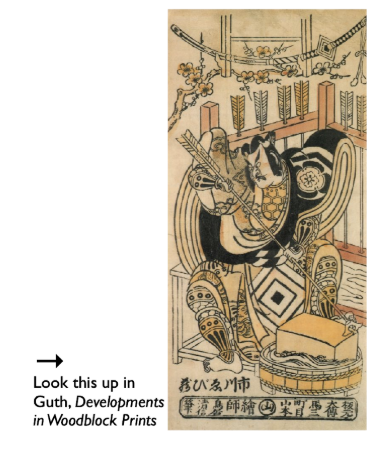

#2)

The Actor Ichikawa Danjūrō II as Soga Gorō;

By Torii Kiyonobu II

Torii Kiyonobu II: Actor Danjūro II

1735 1735 Kabuki Actor: Danjūrō

Kabuki Actor: Danjūrō

Edo Period

Woodblock print on washi

A colorful woodblock print from the Edo period, likely a kabuki yakusha-e (actor portrait).

Bold black contour lines, stylized poses, and flat planes of color.

The figure is highly theatrical, with exaggerated gesture, makeup (kumadori), and elaborate robes that suggest a heroic persona.

There is no illusion of depth, reflecting Edo-period visual conventions that prioritized drama over realism.

#2 Materials and Techinque

Hand-colored woodblock print

Bold line work, iconic poses, and facial expressions

Torii school stylistic conventions

#2) Significance of the Object in Relation to its Historical Context:

-close connection between Kabuki theater and woodblock prints

-Helped define the visual identity of famous actors and shaped public perception of celebrity.

-Captures the persona and stylized performance of Ichikawa Danjūrō II, a legendary Kabuki star.

#2) Social Aspect

Aimed at urban commoners (especially merchants and artisans) who were fans of Kabuki

Prints acted like celebrity posters or fan merchandise, making performers accessible to the public.

Promoted shared cultural literacy in the floating world (ukiyo), with recognizable roles and stylized gestures.

#2) Political Aspect

Kabuki was both regulated and popular, allowing controlled escapism within strict Tokugawa social hierarchy.

Actor prints allowed indirect exploration of identity, performance, and class mobility, subtly pushing against rigid norms.

While not overtly political, prints reflected the desires and tensions of an increasingly self-aware urban class.

#2) Technological Aspects

Pre-nishiki-e printing, limited color palettes and manual coloring.

Involves collaboration between designer (Kiyonobu II), carver, and printer.

Part of the evolving technology that would lead to full-color printing later in the century

Ukiyo-e

-Part of the Ukiyo-e tradition, though it emphasizes warrior heroes (musha-e) rather than pleasure scenes.

-“Setsuei (The Sick Tiger)” is a powerful example of ukiyo-e’s evolution—combining traditional woodblock print techniques with dynamic storytelling and heroic imagery. Kuniyoshi’s work represents a turning point where ukiyo-e expanded from scenes of urban leisure to action-packed, emotionally resonant narratives that captivated Edo audiences.

-classic Ukiyo-e genre showing Kabuki actors, a major theme of "floating world" imagery.

“Pictures of the Floating World”. Ukiyo-e artists produced woodblock prints and paintings that depicted scenes from everyday life, kabuki theater, beautiful women (bijin-ga), landscapes, and historical or mythical stories.

Edo Period (1615-1868)

Created during the Edo period, reflecting the values, tensions, and culture of Tokugawa Japan.

Also from the Edo period, at a time when Kabuki culture and woodblock prints were becoming popular among townspeople.

Pictures of the Floating World

emphasis of living in the moment and ignoring poverty and struggle whilst in a temporary world

Expands the definition — it reflects fantasy and escapism via moral action and heroism.

Directly tied — depicts a Kabuki actor, part of the floating world’s entertainment culture.

Woodblock Prints

woodblocks to create multiple impressions of an image. Artists design an image, then carve it onto a wooden block, which is then inked and pressed onto paper to create prints (allow for mass production)

A prime example of high-level polychrome woodblock printing, produced for mass audience.

Courtesans (Yoshiwara)

red light district and vibrant cultural center known for high class courtesans (prostitutes), and especially development of ukiyo-e prints, theater, fashion

Actors

-Shares theatricality and drama — heroic figures often shown in Kabuki-style poses.

-Direct subject — portrays Kabuki star Danjūrō II, central to Kabuki culture and popular celebrity.

Secularization

decline in importance of religion Emphasizes moral themes (justice, loyalty) in a non-religious, entertainment-oriented format. |

Popularization

Helped popularize Suikōden legends and heroic themes among common people. |

Helped spread Kabuki celebrity culture, bringing live theater into print form for the masses. |

Kabuki

Indirectly influenced by Kabuki poses and storytelling methods.

Directly depicts a Kabuki actor in role, blending theater and print. |

Censorship

censorship of ukiyo-e done through seals of approval, was required for approval to be sold

Mitate-e (Parody or allusion prints)

a subgenre of ukiyo-e that employs allusions, puns, and incongruities, often to parody classical art or events

Summary of how these Key Terms connect to Objects #1 and #2

1) Pictures of the floating world

2) Woodblock Prints

3) Courtesans (Yoshiwara)

4) Actors (Kabuki)

5) Secularization

6) Popularization

7) Censorship

8) Mitat-e

Object #1) Setseui (“The Sick Tiger”) 108 Heroes of the Suikoden

Object #2) Donjuro II as Soga Goro

Both prints are part of Ukiyo-e, reflecting how art captured urban entertainment and public fascination with heroes and performers.

Kiyonobu’s print fits directly into Kabuki culture, celebrity worship, and early actor portraiture.

Kuniyoshi’s print reflects the broadening of Ukiyo-e themes in the 19th century — from courtesans and actors to morally driven warrior tales.

Both respond to popular demand, use the woodblock medium, and navigate censorship by staying within allowed cultural boundaries.

Together, they show how Ukiyo-e evolved from pleasure district portraits to include action, fantasy, and moral storytelling — while still appealing to the same urban audience.

#3) Hokusai, In the Hollow of a Wave off the Coast at Kanagawa, AKA: The Great. Wave. 1830-33

Hokusai’s The Great Wave

Edo Period

Polychrome woodblock print

Printed on washi

A woodblock print from the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series, designed with masterful use of line, shape, and negative space.

The central wave arches like a claw, with foam stylized into sharp fingers — about to crash over the rowboats below.

Mount Fuji, small and serene, sits in the distance, contrasting with the monumental scale of the wave.

The composition uses bold Prussian blue and carefully layered gradation (bokashi) to create a sense of depth.

Though naturalistic in theme, the image is highly stylized, using asymmetry and rhythmic forms rather than realism.

#3) Technique

Ukiyo-e woodblock printing

Prussian blue (imported pigment), indicating increased access to foreign materials

#3) Significance of Object in Relation to its Historical Context:

Screech argues the wave may reference maritime disasters, such as recent shipwrecks and the power of the sea, reflecting Japan’s pre-modern anxiety toward the ocean.

Reflects the tension between nature and man, and Japan’s vulnerability as a seafaring nation.

Symbolic of both awe and fear — natural forces dwarf even sacred Mount Fuji.

Emerged during a period of economic stagnation, rising merchant class, and growing curiosity about the outside world despite sakoku (isolation policy).

#3) Social Aspect:

Aimed at urban commoners, especially merchants, who could afford these prints

Appealed to the popular imagination, showing nature's power and the sublimity of Fuji

Reflects a deepening appreciation for landscape prints among the Edo middle class

#3) Political Aspect

Not overtly political, but created during Japan’s sakoku (closed-country) policy

The inclusion of Western materials (Prussian blue) and composition hints at cultural exchange despite political isolation

The looming wave may subtly express unease about Japan’s fragile geopolitical position, especially as Western naval threats would soon grow

#3) Technological Aspects:

Advanced multiblock woodcut process, mastery of depth and movement

Use of Prussian blue was innovative, imported via Dutch traders at Nagasaki

Reflects technical innovation in landscape composition — unprecedented dynamism and scale in Japanese print

Hokusai CONNECTION TO KEY TERMS

Mt. Fuji

36 Views of Mount Fuji, artwork made on Fuji because bro was interested in immortality

Central symbol in the background — appears tiny compared to the wave. Screech notes it is a sacred mountain, and its name puns on “no death” (fu + shi). This makes it an auspicious sign, even when facing maritime danger. Fuji is a spiritual anchor amid chaos

Birds

Not explicitly present in this image, but in other Hokusai prints birds represent freedom, perspective, and narrative contrast — here, the absence of birds emphasizes the human vulnerability to nature. |

Ghosts

The wave has ghost-like, clawing fingers, almost monstrous, giving it a supernatural, threatening presence. Screech suggests this evokes maritime dread, like the haunting power of the sea.

Representations of traditional ghost stories

Pedagogy

method and practice of teaching; Hokusai published work that shared his techniques

Part of Hokusai’s project to educate through art — teaches visual storytelling, moral reflection (mortality, nature’s power), and deep appreciation of composition and design. Also shows Hokusai’s teaching legacy to younger artists

Composition

contains a huge wave, and Mt. Fuji is smaller in the background, in between two waves. There is an organizational principle, where the profile of the biggest wave is parallel to another wave beneath it, and is repeated

Masterful: the wave forms a spiral that frames Mt. Fuji. The dynamic diagonal sweeps from top left to bottom right, pulling the viewer into the scene. Asymmetrical balance creates drama. Boats are tilted and unstable, increasing tension.

Materials

Materials - Prussian Blue, brushwork, ukiyo-e polychromatic print Polychrome woodblock print using imported Prussian blue — a cutting-edge material that allowed intense, deep color. The use of this pigment shows global trade impact during sakoku, even if indirect. |

Meaning

representation of the unpredictable nature of life, the power of nature, and the struggle between humanity and the elements

Layers of meaning: nature’s overwhelming force; man’s frailty; Fuji as eternal and sacred; a commentary on Japan’s isolation and vulnerability. Screech suggests it is an image of near-death and also hope, rooted in Fuji’s symbolism.

Seriality

Part of the Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji series. Hokusai shows Fuji from different locations, in varied weather, and through different human experiences. Seriality allows viewers to see changing contexts, while Fuji remains constant.

Part of 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, first in the series

“To the Dutch, all was in the hands of God... Hokusai showed the very same thing... Mt. Fuji is not only hallowed, but its name puns on ‘no death.’”

— T. Screech, Maritime Disasters and Auspicious Images (2021)

Screech argues that The Great Wave is not just a nature scene, but a spiritual image:

The wave becomes a destructive force that humans (the fishermen) struggle against.

But Mt. Fuji remains unmoved, symbolizing eternal stability, divinity, and possibly salvation.

The wordplay on Fuji = "no death" suggests that even amid chaos, there's a promise of endurance or rebirth.

1) Mt. Fuji

2) Birds

3) Ghosts

4) Pedagogy

Great Wave off of Kanagawa

5) Composition

6) Materials

7) Meaning

8) Seriality

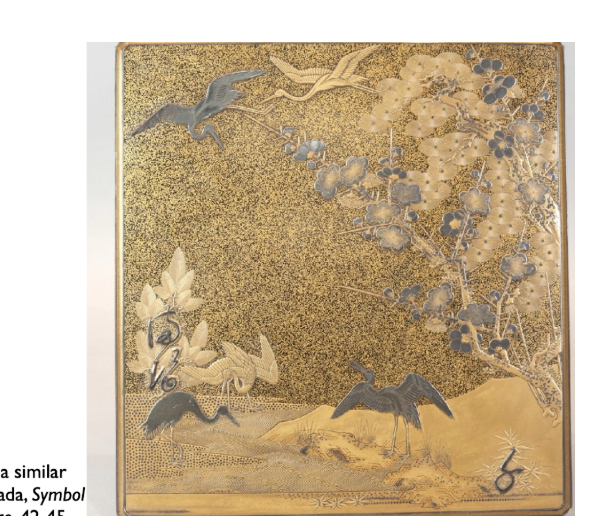

#4) Writing Box with Cranes, Pines, Plum Blossoms, Characters

Edo Period: A time of political stability under Tokugawa rule, economic growth, and flourishing of elite and merchant culture.

Luxury arts like lacquer were prized among samurai, aristocrats, and wealthy merchants.

Material: Lacquered wood, decorated with gold and silver maki-e (sprinkled metal powder), and mother-of-pearl inlay in some cases

Often featured black roiro lacquer base for a mirror-like polish.

This is a lacquered writing box (suzuribako)—a traditional Japanese object used for calligraphy tools (inkstone, brush, water dropper).

The surface is richly decorated with gold and silver maki-e (sprinkled metal powder lacquer technique), creating a luxurious, textured appearance.

Cranes, pine trees, and plum blossoms are elegantly arranged—these are all seasonal and auspicious motifs in Japanese art.

The design is asymmetrical but harmonious, with motifs emerging out of the gold ground and flowing gracefully across the lid.

There is a visual balance between positive space (the forms) and negative space (background lacquer), emphasizing refinement and restraint.

#4) Technique

Maki-e: Sprinkling gold or silver powders into wet lacquer, layered for depth and shimmering effect.

Takamaki-e (raised design) and hiramaki-e (flat design) used to distinguish textures like feathers or tree bark.

Finely detailed work involved multiple polishing and layering stages, showing exceptional craftsmanship.

#4) Signficiance in Historical Context

Such boxes were functional luxury items for calligraphy and poetry writing, but also status symbols.

The imagery of cranes, pine, and plum blossoms signifies longevity, renewal, and resilience — common auspicious themes in Edo aesthetics.

As Okada notes, the use of symbolic motifs reflects Confucian values and seasonal awareness, aligning with elite ideals of refinement.

#4) Social Aspect

Owned by elite samurai or wealthy merchant-class women; reflects a cultivated, literate lifestyle.

Lacquer boxes were often wedding gifts or heirlooms, underscoring family ties and cultural education.

Demonstrated the owner's aesthetic taste and social refinement.

#4) Political Aspect

These luxury goods were a way for the Tokugawa regime to promote cultural identity and social order.

Reinforced status hierarchy — only certain classes could afford or legally own such ornate items.

Designs subtly reinforced ideals of harmony and longevity, mirroring Tokugawa political messaging.

Technological Aspects

Represents peak Edo lacquer technology — including refined layering, burnishing, and metal powder control.

Advances in adhesives, carving tools, and polishing techniques allowed for ever finer and more complex designs.

Shows transmission of techniques from Kōami and Kajikawa lacquer schools, prominent artisans of the time.

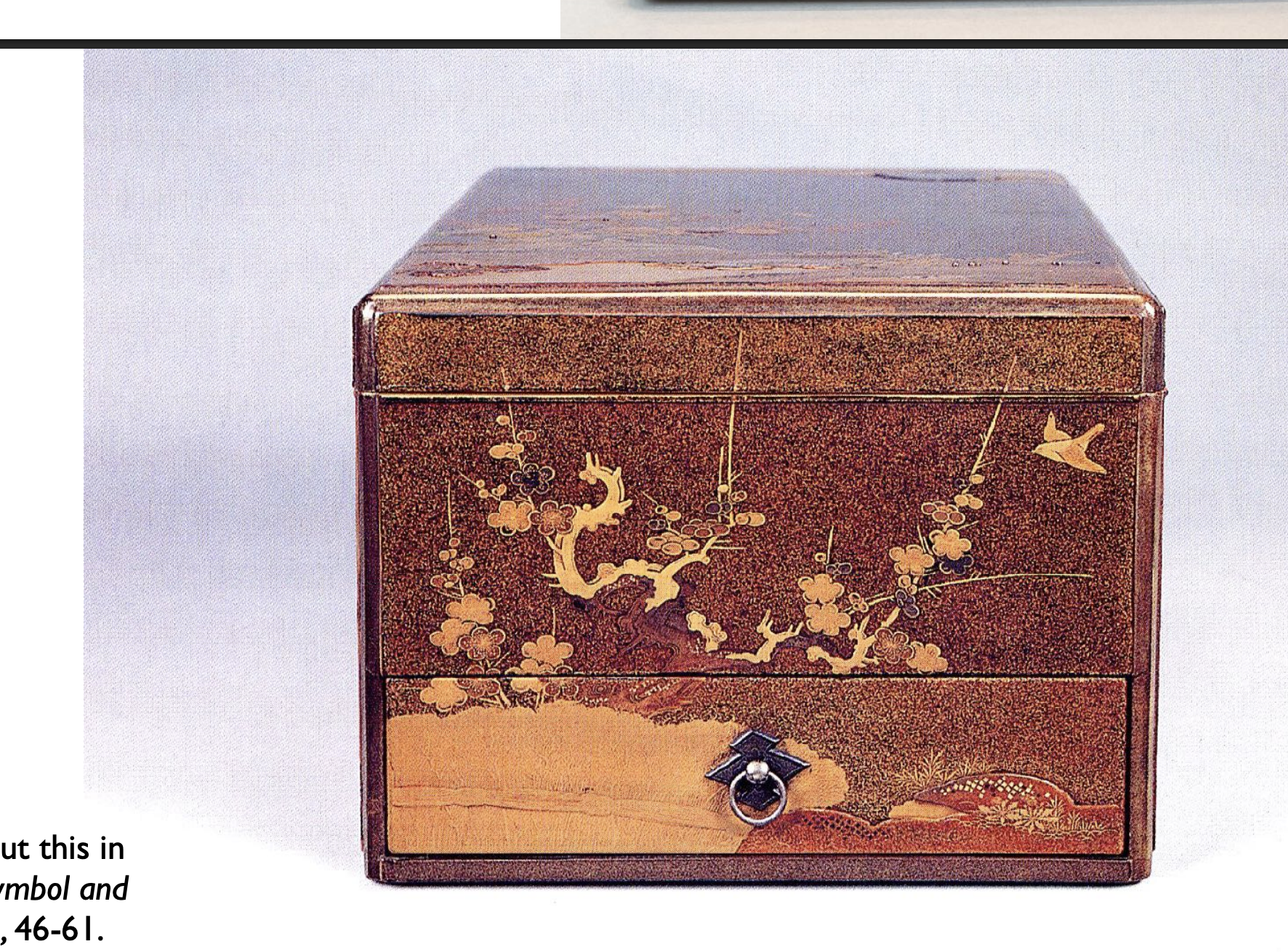

#5 Tebako Handbox, cosmetic container, motifs of the 4 seasons

Edo Period: The rise of the merchant class and elite women’s culture increased demand for elegant domestic items.

Material: Lacquered wood, decorated with gold and silver maki-e (sprinkled metal), mother-of-pearl inlay, and occasionally lead or tin details for added visual complexity.

Observations:

A tebako is a lacquered handbox, often used to store cosmetics, personal items, or ceremonial accessories.

This object is richly decorated with motifs of the four seasons—typically including:

Cherry blossoms (spring)

Irises or flowing water (summer)

Maple leaves (autumn)

Pine, bamboo, or plum blossoms (winter)

The box is adorned with maki-e (sprinkled gold/silver powder lacquer) and raden (mother-of-pearl inlay), creating dazzling reflective surfaces.

The visual layout flows naturally, often following the rhythm of nature, with careful asymmetry and negative space, common in Japanese aesthetics.

The surface design may wrap seamlessly around the box, creating a 360-degree viewing experience.

#5) Techniques

Utilizes multiple maki-e techniques:

Hiramaki-e (flat sprinkled designs)

Takamaki-e (raised maki-e for dimension)

Raden (mother-of-pearl inlay)

Highly detailed imagery of seasonal motifs (e.g., cherry blossoms, autumn leaves, snow-covered bamboo) layered through polishing and burnishing.

#5) Significance of Object in Historical Context:

Tebako were used by elite women to store cosmetics, perfumes, or writing tools — objects of personal grooming and poetic life.

The motifs of the four seasons reflect classical aesthetics, evoking mono no aware (sensitivity to impermanence).

Okada emphasizes that these boxes transcended function, serving as visual expressions of culture seasonality and refined taste

#5) Social Aspect

Symbol of elite femininity, literacy, and artistic engagement.

Often given as marriage gifts to samurai or aristocratic women, tying beauty to moral and seasonal awareness.

Represented social status, aesthetic sophistication, and cultural education within the confines of gendered expectations

#5) Political Aspect

Reflects the Tokugawa social order, where sumptuary laws restricted visual excess to elite circles.

Displays how state-sponsored cultural values (stability, nature, decorum) were embedded in objects of daily use.

Luxurious yet coded with conservative symbolism — reinforcing Confucian ideals of harmony and propriety.

#5) Technological Aspects

Advanced lacquer techniques reflect generations of refined craftsmanship.

Workshops perfected seasonal landscape designs through intricate layering, drying, and polishing processes.

Demonstrates technical control over color contrasts, textural variation, and optical effects like depth and shimmer.

Connections to Key Art Terms of #4 and #5

Lacquer

Plant used to make lacquer, via the toxic sap (refine and remove impurities)

The object is made of lacquered wood, using the sap of the Rhus verniciflua tree (Japanese lacquer tree). This natural resin is durable, water-resistant, and capable of holding gold and silver decoration.

Rhus verniciflua

The base lacquer of the writing box is made from the sap of this tree. Its ability to harden into a glossy finish allows for the intricate, layered artwork typical of high-quality Edo lacquerware. |

Lacquer decorating techniques: maki-e

The writing box is decorated using maki-e ("sprinkled picture") techniques: powdered gold and silver are applied to wet lacquer to create elegant imagery.

Writing boxes (suzuribako

This object is a suzuribako — a writing box used to store inkstones, brushes, and other calligraphy tools. Beyond function, it symbolizes literary refinement and the importance of poetry and seasonal awareness in elite culture

- straight forward, but associated with aristocrats, and members linked to the ruling class. Could also be associated with the merchant class, as some who were wealthy wanted to replicate

Hand box (tebako) |

the writing box shares decorative and symbolic qualities with tebako

often used as marriage gifts or status items.

Both types of boxes feature seasonal motifs and employ luxury materials to convey meaning.

It was central to women’s grooming and elegance in the Edo period. As a seasonal and symbolic art piece, the motifs express cycles of life and nature, reinforcing cultural ideals of femininity and time.

used to hold womens cosmetics, used as part of a trousseau (marriage gift). Each panel associated with a different season

Inrō (seal case)

signature seal used to confirm documents (men only). Bypassed Sumptuary Laws (illegal for merchants to display wealth)

Japanning

The Tebako, like the suzuribako, inspired Western fascination with Japanese lacquerware. European craftspeople in the 17th–18th centuries sought to imitate this refinement in boxes and vanity items using japanning techniques.

Though Japanning refers to European imitation of Asian lacquer techniques, this box represents the original Japanese model that inspired Western crafts.

a historical finishing process, particularly popular in Europe, where materials like wood, metal, and tin were coated with varnishes and then baked to achieve a durable, hard, and shiny finish, often imitating the appearance of lacquered work from Japan and China

Summary of Key Connections from #4 and #5

1) Rhus verniciflua

2) Lacquer Decorating

3) Techniques: Maki-e

4) Writing box (suzuribako)

5) Hand box (tebako)

6) Inrō (seal case)

7) Japanning

The Writing Box with Cranes, Pines, and Plum Blossoms embodies Edo-period lacquer aesthetics at their peak. It not only utilizes the maki-e technique and Rhus verniciflua lacquer, but also fits into the broader world of elite portable objects like tebako and inrō. As an authentic suzuribako, it shows how writing tools became symbols of refinement, and how lacquer art influenced even European decorative arts through japanning.

The Tebako — a handbox for cosmetics — embodies the same artistic traditions and cultural values as the Writing Box with Cranes, Pines, and Plum Blossoms. Both are:

Crafted with Rhus verniciflua lacquer

Decorated with maki-e techniques

Rich in seasonal and symbolic motifs

Used in elite circles to express refinement, literacy (in the case of suzuribako), or beauty (in the case of tebako)

Connected to global decorative arts through their influence on Japanning in Europe

They are part of a broader ecosystem of Edo-period portable luxury items that communicated identity, gender roles, and aesthetic ideals through art and function.

Meiji Period

Marked by rapid modernization and Westernization after centuries of isolation.

Aimed at transforming Japan into a modern imperial power, with new institutions, technologies, and architectural forms reflecting global ambitions

#6) Akasaka Detached Palace, Architect: KATAYAMA Tokuma, Tokyo, 1897-1909, Meiji Period

Architect: Katayama Tokuma

Location: Tokyo, Japan

Date: 1897–1909

Period: Meiji Period (1868–1912)

Material:

Steel frame, stone, granite, marble, and glass — all hallmarks of Western-style palace architecture.

Extensive use of imported materials alongside Japanese craftsmanship to show technological capability and cultural fusion.

Observations:

The Akasaka Palace is a monumental Western-style Neo-Baroque building, featuring:

A symmetrical façade with a central pediment and side wings.

Columns, pilasters, balustrades, arched windows, and decorative stone carving — all hallmarks of European royal architecture.

A grand entrance staircase, mansard roof, and ornamental metalwork, which reference French Second Empire architecture (think Versailles).

Lavish interior spaces including ballrooms, chandeliers, and gilded ornamentation — highly ceremonial and performative in nature.

#6) Technique

European-style construction: neo-Baroque and neo-Renaissance design, modeled after Western royal palaces.

Employed Western architectural techniques:

Katayama Tokuma, implemented Beaux-Arts principles like axial symmetry, grand staircases, and ornamented façades.

#6) Significance of Object in Relation to its Historical Context:

Symbol of Japan’s entry into global modernity and empire-building.

showing that Japan had "caught up" with the West.

Part of a broader movement to redefine national identity through imperial spectacle and visual power,

Signaled Japan’s ambition to be seen as an equal among colonial powers.

#6) Social Aspect

Embodied the rise of a new elite class

Reflected a shift in taste and authority

Reinforced social hierarchy through architecture: palatial spaces were inaccessible to the public but visible as symbols of prestige.

#6) Political Aspect

Served as visual propaganda for the Meiji state — representing order, strength, and international legitimacy.

, but a diplomatic stage for the imperial household to receive foreign powers.

buildings like this shaped Japan’s image as a modern, civilized nation,

#6) Tecnological Aspects

Western engineering, including gas lighting, modern plumbing, and heating systems.

successful adoption of global building technologies

Hybrid use of Japanese artisans and European architectural knowledge showcased Japan’s adaptive skill in technological transfer

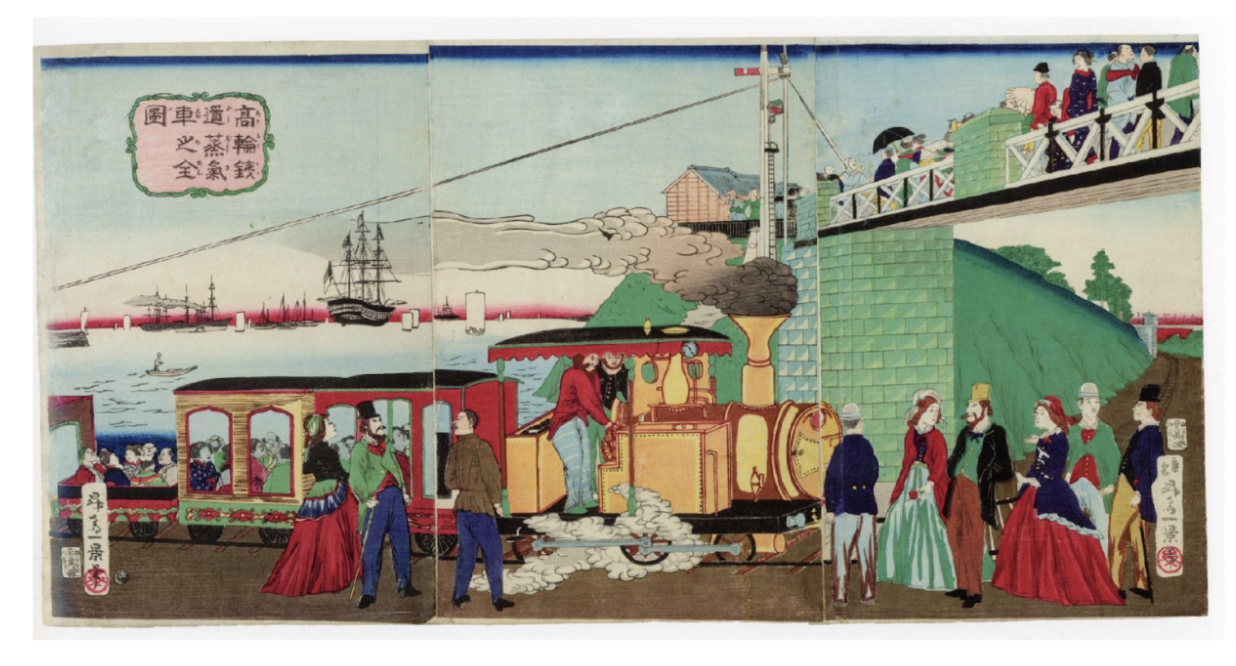

#7) Shōsai IKKEI, Complete View of a Steam Engine at Takanawa, 1871-72. Woodblock print.

Meiji period: time of massive political, social, and technological transformation as Japan transitioned from feudal isolation to modernization and Westernization.

Material: Woodblock print (nishiki-e) on paper

Ink and color on paper using traditional Japanese print methods, even as the subject matter reflects modern Western technology.

This is a color woodblock print showing a steam locomotive moving along the new railway line near Takanawa, a suburb of Tokyo.

The train, with puffs of white steam and dark smokestack, cuts across the composition, emphasizing speed and mechanical power.

People in traditional Japanese clothing gather near the tracks, observing the locomotive—often in a state of awe or curiosity.

The scenic background includes elements of traditional Japanese landscape art: trees, water, and sky, using established ukiyo-e techniques like bold outlines and flat colors.

The juxtaposition of foreign technology with Japanese setting and figures is a striking feature of the composition.

#7) Technique

Traditional ukiyo-e woodblock printing,

Maintains stylistic features of Edo-period prints (bold lines, vivid colors), but introduces modern/foreign subject matter—in this case, a steam locomotive.

Artist uses panoramic perspective and detailed technical illustration to depict something newly visible in Japan: the steam train.

$7) Significance in Historuical Context

This print visually documents Japan’s rapid modernization under the Meiji government, specifically the arrival of Western industrial technology like railways.

Trains represented not just transportation, but a symbol of progress, empire-building, and national power.

Foxwell emphasizes how artists like Ikkei created “transitional imagery” to help Japanese viewers visually process unfamiliar modern elements using familiar artistic language.

#7) Social Aspect

This print helped the public understand and normalize modern technology.

It also reflects a shift in popular taste: from kabuki actors and courtesans to trains, soldiers, and machines—marking a new phase of popular education through images

As Foxwell writes, these prints were a form of visual pedagogy, helping people reconcile traditional Japanese aesthetics with modern realities.

#7) Political Aspect

The image supports the Meiji state’s agenda of modernization and Westernization.

Prints like this celebrated and visually legitimated state authority and technological progress in the public imagination.

#7 Technological Aspects

Subject matter is the steam locomotive, introduced from Britain, showing Japan’s engagement with global technology.

print itself is a hybrid of traditional technique and modern subject, marking a key moment in the evolution of Japanese visual culture.

how woodblock printmaking adapted to depict new machinery and industrial subjects despite its non-mechanical, handmade nature.

#8) A Collection of Pictures of Chignon Wigs to Put On, 1887. Woodblock prints. By artist: Toyohara CHIKANOBU,

Artist: Toyohara Chikanobu

Meiji Period: A moment of rapid change in gender roles, fashion, and national identity under modernization.

Material: Polychrome woodblock print on paper.

Produced using traditional ukiyo-e techniques (color, ink, and multiple blocks), but showcasing contemporary Meiji fashion trends.

#8) Technique

Highly detailed rendering of female hairstyles (chignon wigs)—often standardized wigs worn by modernizing Meiji women, particularly in official or semi-official roles.

#8) Sig in Historical Context

print reflects the codification of modern womanhood in the Meiji era.

The wigs represent a new, semi-official appearance for women aligned with state ideals of progress, modernity, and modest femininity.

promotes visual standardization, part of the Meiji state’s larger project of modern identity construction.

#8) Social Aspect

Offers a view into changing roles and visibility of women during the Meiji period

Hair became symbolic of one’s alignment with modern, civic ideals; women were visually recruited into the national modernization project.

The artwork functioned like a visual guidebook—educational and aspirational—especially for middle-class women adapting to new expectations.

#8) Political Aspect

Tied to the Meiji government’s effort to modernize public appearance and behavior, especially in court and civil service.

Women’s outward presentation (including wigs) was politically loaded, signaling their participation in the new, Western-modeled imperial nation.

Print participates in state-aligned image-making, promoting approved versions of womanhood.

#8) Tech Aspects

While the medium is traditional, the subject reflects a mechanized or standardized approach to beauty: wigs that could be worn rather than natural hairstyles.

mass production and reproduction of fashion and personal identity were emerging through both print culture and commodities.

hybrid identity: traditional aesthetic in form, but modern and industrial in content.

Key Connections to Terms #6, #7, #8

Meiji Architecture / Meiji Modern

#6) Exemplifies Western-style imperial architecture; designed in Neo-Baroque style to assert Japan’s modernity.

#7) The steam train was a symbol of modernization and industrial advancement. This image shows how new technology entered public consciousness.

#8) Shows how even female appearance became codified and modernized, reflecting new norms for women in public/civic life

Unequal Treaties/Meiji Restoration

Unequal treaties - agreements imposed on weaker nations by stronger powers, where they forced the weaker nations to cede territory, grant privileges to foreign citizens, and infringe on their sovereignty

Meiji Restoration: coup d’etat, establishment of new government. Rapid industrialization and modernization in response to pressures and influence of Western powers

#6) The palace is part of the post-1868 effort to prove Japan’s civilizational parity with the West and recover full sovereignty.

#7) In response to foreign pressure (e.g. Black Ships), the Restoration sought military, technological, and economic parity with the West. Railroads were part of this. |

Pseudo-Saracenic Style

blend of Western (specifically Indo-Saracenic) and Japanese architectural elements, with a focus on incorporating Indian architectural motifs

#6) Not directly present here, but the palace reflects Japan's hybrid adoption of Western styles, like Neo-Baroque and Beaux-Arts, in architecture.

Rokumeikan

#6) Built for political reasons, as an essential tool of state for convincing foreign visitors that Japan was entering the reincarnation of urban civilization. Contains round arches, from Italian architecture

Both the Rokumeikan and Akasaka Palace symbolized Japan’s diplomatic theater—spaces meant to impress Westerners and normalize elite Japanese in Western dress and etiquette.

Black Ships

the American warships that arrived in Japan. These ships forced Japan to open its doors to Western trade and diplomatic relations after its 220-year isolation policy. The arrival of the Black Ships, coupled with the perceived weakness of the Tokugawa Shogunate, ultimately led to the collapse of the shogunate and the establishment of the Meiji Restoration

#7) Complete View of a Steam Engine at Takanawa: triptych, made of 3 woodblock prints, a representation of the first train in Japan (important as its like westernization)

The train is a technological descendant of Western incursion and a visual counter-narrative to Japanese vulnerability. |

Bustle

#8) Wigs symbolized a stylized form of Westernization, similar to the bustle in dress reform. Both aligned female bodies with new roles in Meiji society.

Style of clothing , where the bottom half of the dress protrudes 90 degrees out from the butt. Typically made of whale bone

Synchronicity

#7) Foxwell argues that Meiji prints helped synchronize old visual forms with new realities. Here, traditional woodblock form depicts a radically new subject.

#8) Foxwell’s central idea: this print bridges tradition and modernity—traditional print technique with new social ideals.

Hybrid, using traditional forms of woodblock print to depict and express current modernization and Westernization of technology and womanhood

Neo Baroque Style

#6) Directly applies: the palace uses aedicula, rustication, pediments, and acroteria—hallmarks of Baroque revival architecture.

#7)

This print contains both Edo-period aesthetic conventions and Meiji-era content, showing how past and future coexisted in art. |

#8) The co-presence of Edo-period aesthetics and modern Meiji ideals exemplifies the coexistence Foxwell describes.

Gold Standard

#8) Like the gold standard’s imposition of economic uniformity, these wigs suggest a push toward social and visual uniformity under the modern state

“Architecture became an essen+al tool of state for

convincing the flood of foreign visitors entering Japan of

its reincarna+on as an urban and urbane civiliza+on.

Architecture was charged with a mission of the highest

na+onal significance: proclaiming loudly on every city

block and street corner Japan's assurance and authority

as a modern state.” — William Coaldrake, Building the

Meiji State, p.209.

This quote emphasizes architecture as propaganda — buildings were designed not just for use, but to project modernity and national strength to foreigners and Japanese alike.

#6) This Western-style palace directly reflects the state’s effort to perform modernity. Its Neo-Baroque style, inspired by European palaces, was used to impress foreign diplomats and assert Japan’s new international identity.

#7)Though not a building, this print captures the infrastructure of modernization (railways, steam power) — physical proof of Japan’s entry into industrial modernity.

even mechanical and urban structures became tools for visual messaging, showing that Japan was no longer isolated or “backward.”

#8) It reflects cultural architecture: the body and fashion as structured, designed, and modernized. The presentation of fashionable wigs links to Japan’s efforts to appear “urbane” and cultured — especially as women were often symbols of national civility and refinement.

Coaldrake: |

Architecture as a national tool to project modernity to foreigners |

Akasaka Palace (Western architecture), Steam Engine (tech as infrastructure), Chikanobu’s Wigs (cultural modernization) |

““Multiple versions of Japan seemed to coexist in the

same space.”

— Chelsea Foxwell, “Toward Synchronicity: Meiji Art

in Transition,” Meiji Modern, p.14”

This quote addresses synchronicity — the coexistence of tradition and modernity, East and West, past and present during the Meiji period.

#6)While Neo-Baroque in design, the palace was inhabited by Japanese elites in kimono, creating visual tension.

It’s a perfect example of Foxwell’s idea — an architectural shell of the West filled with Japanese ceremonial tradition.

It shows the state trying to manage multiple identities at once: modern and imperial, Western and uniquely Japanese

#7) This print shows a Western machine rolling through Japanese space, often watched by onlookers in traditional dress.

It reflects the layering of time periods — industrial modernity coexisting with a still deeply Edo-period visual world.

A direct visual of synchronicity: foreign technology within a Japanese scene.

#8) The wigs blend Edo-period aesthetics with new Meiji beauty ideals — some chignons are more elaborate, others Western-influenced.

Women’s appearance became a site where Japan’s hybridity was staged and explored.

Like Foxwell says: multiple versions of Japan (traditional femininity, modern fashion, national identity) appear on a single body.

Foxwell |

Japan was layered — tradition and modernity coexisted |

All 3 show synchronicity: Western and Japanese elements merging within one visual or physical space |

6,7,8 Summary Table

Akasaka Palace | Neo-Baroque, Meiji Architecture, Coaldrake, Rokumeikan | Modern imperial identity, Western legitimation, diplomacy |

Steam Engine Print | Synchronicity, Foxwell, Black Ships, Meiji Restoration | Technology, modernization, visual education |

Chignon Wig Print | Bustle, Synchronicity, Gender roles, Visual pedagogy | Gendered modernization, state-controlled aesthetics |

1) Unequal Treaties

2) Meiji Restoration

3) Pseudo-Saracenic Style

4) Rokumeikan

5) Black Ships

6) Bustle

7) Synchronicity

8) Neo Baroque Style

9) Gold Standard

#9) Incense Burner (Kōro), 1870-75 Bronze, with gilt, silver, shibuichi, and shakudo H: 5’ Signed by Suzuki CHŌKICH

Mejiji Period: time of rapid modernization and international diplomacy.

Created during Japan’s efforts to present itself as an advanced industrial and artistic power in World’s Fairs and international exhibitions.

Material of Object:

Bronze, with inlays of

Gilt (gold)

Silver

Shibuichi (copper–silver alloy)

Shakudō (copper–gold alloy with dark patina)

#9) Technique:

Highly technical mixed-metal work (kōdōgu tradition) adapted to large-scale sculpture.

Use of inlay, high-relief, and intricate carving—elevated from traditional sword-fitting techniques to monumental decorative arts.

Signed by Suzuki Chōkichi, a master metalworker who was officially appointed by the Imperial Household Agency.

#9) Significance in Historical Context:

-Represents Japan’s entry into global art markets and diplomatic exhibitions

-Demonstrates how Japan repurposed elite Edo-period craft skills into luxury export commodities during the Meiji Restoration.

-Part of Japan’s broader effort to refashion its national image through decorative arts, showing mastery of both tradition and industrial modernity.

#9) Social Aspect:

-Reflects the professionalization and elevation of craftsmen like Suzuki Chōkichi into internationally recognized artists.

-Responded to Western demand for exotic, masterfully crafted Japanese objects

-Symbolizes how Meiji society redefined artisan identities, moving from swordsmiths and craftsmen to modern designers and cultural ambassadors.

#9) Political Aspect

Served as a cultural diplomatic object—part of Japan’s soft-power strategy to impress foreign powers and assert its status as a modern empire.

The Meiji government sponsored these works as national showcases at World’s Fairs, using them to counter stereotypes of Japan as feudal or primitive

Often presented alongside architecture and industrial products to show a holistic vision of modernity.

#9) Tech Aspects

Reflects Meiji-period advances in metallurgy and scaling up craft production without losing intricacy.

Combines traditional alloy techniques (e.g. shakudō, shibuichi) with modern tools and exhibition-driven standards.

Demonstrates Japan’s ability to compete with European bronze casting and luxury metalwork on a global stage.