Chapter 11 Social Control, Deviance, and Crime

1/66

Earn XP

Description and Tags

LO1 Define social control, identify its relationship to deviance, and differentiate among its varying types. LO2 Compare the different criteria that are highlighted as the foundation for determining deviance and explain the view that deviance is socially constructed. LO3 Explain the relationship between the concepts of deviance and crime. LO4 Outline the contrasting views of how laws are created, identify the legal meaning of a crime, and differentiate among crime classifications. LO5 Describe the criminal justice system and the rationale for punishment as the primary means for controlling crime. LO6 Discuss critiques of traditional forms of punishment and explain how restorative justice differs from retributive forms of punishment. LO7 Identify and describe the theories used to explain the causes of deviance and those that explain our perceptions of and reactions to particular behaviours and characteristics.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

67 Terms

Social control and deviance

Actions intended to prevent, correct, punish, or cure people, behaviours, and characteristics that are perceived as unnacceptable.

These unacceptable behaviours are considered deviant: A person, behaviour, or characteristic perceived as unacceptable.

Not just police enforcing the law. But how many of us recognize that we are those people who are socially controlled? And how many of us recognize that at the same time we are also the ones who are doing the controlling

Examples of acceptable behaviour and deviance and how easy it can be changed

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally altered what we perceived as acceptable (e.g., wearing masks and physical distancing) and what we viewed as deviant (e.g., not wearing masks, sitting or standing less than two metres apart from someone else)

How are measures of social control applied?

When a person breaks the norm and commits an unacceptable behaviour, measures of social control are applied.

Sometimes measures of social control are formal, implemented through an “official” mechanism that carries some institutionalized authority—such as a workplace dress code dictating that you must conceal your tattoos or piercings, or the police arresting and charging you with a crime.

But they can be applied much more casually, Other times, we are subjected to informal measures of social control in everyday social interaction—bullied for your gender identity or expression, or stared at because of your physical appearance.

When are measures of social control applied?

Some forms of control are intended to punish or cure (and may be formal or informal) after a deviant behaviour or characteristic has been detected. Examples include receiving a ticket for texting while driving or being teased about your weight. Other forms of control are intended to prevent deviance from occurring in the first place—for example, educational programs in schools that teach children about the dangers of smoking (to prevent substance use) or community programs that provide leisure activities for inner-city youth (to prevent criminal activity). Sometimes we even exert measures of social control upon ourselves, such as by going on a diet to lose weight or studying harder for a final exam to avoid failing a class.

SO who does social control affect?

Thus, social control is not just targeted at “some people.” We are all subjected to measures of control every single day. Furthermore, sometimes we are the ones who stare at, tease, or bully others; we are the parents disciplining our children for breaking the house rules; we are the people who avoid making eye contact with a homeless person; we are the people who enter professions that formally exert measures of social control (as teachers, police officers, employees in the university’s registrar’s office, or group home workers)

What makes a behaviour deviant? Is it as simple as one would think?

why are some perceived as unacceptable, whereas others are not? What do texting while driving, having a non-conforming gender identity or expression, not wearing a mask during the COVID-19 pandemic, and wearing “inappropriate” clothes to work have in common?

They all violate norms!!! Unacceptable! In fact, you will often see “deviance” defined as a behaviour that violates society’s norms.

But from a sociological perspective, deviance is far more complex than this definition suggests. Norms are not universal and unchanging but rather are socially constructed. Societies evolve and change over time, which means that norms change over time as well. Think about it, if you described something as “rawdogging it” a couple years ago, people would think you’re crazy/deviant, but now its the norm.

Furthermore, society is composed of countless different social groups. Which group’s specific expectations for behaviour are the ones being used as the standards for judgment in society more generally?

Four qualities that can make up someones definition of deviance

within academia, there is some disagreement over the definition of deviance. Some scholars put forward “objective” definitions that highlight a specific quality that inherently makes certain acts deviant and in need of social control (Bereska, 2022; Inderbitzin et al., 2020). At the same time, these scholars often dispute precisely what that quality is (Sacco, 1992).

Are behaviours that are statistically uncommon the ones in need of control (e.g., being very thin, having purple hair)?

Or is it those that cause harm that are unacceptable (e.g., criminal activity, failing to wear a mask during a pandemic)?

Might it be behaviours and characteristics that “most Canadians” disapprove of (e.g., racism)?

Maybe it is those that violate norms, as the dictionary suggests (e.g., closing the elevator door when someone is rushing to get on).

Each of these four qualities has served as the definition of deviance for some scholars.

Contradictions in definition of deviance

But even “objective” criteria can be called into question because there are times when a behaviour fits one of these criteria (e.g., is statistically rare) yet is not considered unacceptable or subjected to measures of social control. For example, although health authorities told us to wear masks during the COVID-19 pandemic, images in the news showed us many locations were few people were doing so (e.g., beaches, political rallies for American president Donald Trump). Although wearing masks was statistically uncommon in numerous places, it was still considered acceptable—and even expected by many. Conversely, alcohol consumption is statistically common among high school students (Health Canada, 2017) but is still considered to be unacceptable by many parents (who punish their underage children for coming home drunk from a party) and by the state (in that the law prohibits the sale of alcohol to people under a certain age)

So each of these violates one condition of deviance but satisfies another, it is hard to define deviance solidly.

subjective definition

Because the definition of deviance is so interderminate, scholars focus on a subjective definition that rather identifies why we categorize certain acts to be deviant, what makes acts socially unacceptable.

draws attention to the social processes that teach us how to label acts as good/bad, right/wrong, and normal/abnormal.

This view emphasizes the subjective manner in which deviance is socially constructed and how it is influenced by the structure of power in society. For instance, although cannabis consumption is considered acceptable now (in that it is legal for adults), the sale of cannabis was considered criminal in Canada for almost a century

From this perspective, deviance is defined as those acts deemed unacceptable by the moral codes that emerge from positions of power in society

So, then, why are you given a ticket for texting while driving? Because legislators have determined that doing so is unacceptable, and law enforcement agencies are tasked with enforcing that view. Why are individuals who are LGBTQIA2S+ frequently victimized by hate crimes? Because they are perceived by some as stepping outside the dualisms equating sex, gender, and sexuality that have historically dominated Euro-Canadian discourses. In some cases, there will be agreement in society that a specific act is unacceptable (e.g., murder). In other cases, there will be less agreement or even considerable dispute (e.g., getting a tattoo).

different types of deviance

Deviance scholars study a wide range of behaviours and characteristics (Bereska, 2022): cyber deviance (e.g., cyber bullying, digital piracy); body modification (e.g., tattoos); the sex industry (e.g., pornography, exotic dancing); bodies deemed to be “too fat” or “too thin”; substance use; mental illness; alternative religious groups; criminal activity; and more.

What behaviours are subjected to the most formal measures of social control?

Criminal behaviours are often viewed as acts that most of us would agree are unacceptable. Furthermore, they are subjected to the most formal, institutionalized measures of social control in contemporary society—those stemming from the criminal justice system.

criminologists

Scholars who focus their analyses on crime

What is a crime?

Which behaviours, exactly, are considered criminal? They are those that are deemed by legislators as so unacceptable that they must be embodied in government legislation. At that point, a behaviour is labelled a crime; in other words, a crime is any behaviour that violates criminal law.

Is crime a label that changes?

Which acts receive this label is not static but varies over time. For example, medically assisted dying was illegal (and was labelled “doctor-assisted suicide”) until 2015, when the Supreme Court of Canada ruled the law unconstitutional because it violated people’s basic human rights. During that same year, we saw another change in criminal law, when the non-consensual sharing of sexual images via social media became illegal.

Constitution changes, and things either gain or loose their label as a crime.

3 Perspectives on the nature of the law

consensual

conflict

interactionist

bonus: balance

Consensual view

the behaviours that are legislated against in criminal law, people have all generally agreed that they should be legislated against. it is presumed that the ensuing measures of social control are then equally applied to everyone.

Basically says that criminal law is there and everyone agrees it should be.

However, other scholars argue that there is a political aspect to law creation, wherein laws do not necessarily reflect public opinion.

Conflict view

the ruling class creates and uses the law to serve its own interests

Interactionist view

legistlation emerges from interactions between special interest groups who have identified a social problem and powerful groups they approach to resolve that problem (the government).

Do people view the law as a balnce

Finally, others view the law as a “balance” that has been struck among the opinions of special interest groups, the attitudes of the majority, and the interests of the powerful.

Canadian enforcment of criminal social control

Whatever the process of law creation, in Canada, we can find the outcome of that process in the Criminal Code of Canada (1985), which lists crimes and their corresponding penalties.

How does Canadian legislation define ciminal activity and intent?

According to Canadian legislation, a criminal offence has occurred when a criminal act has taken place and there was corresponding intent to commit the act

Intent here refers to “blameworthy” in the sense that a “reasonable” person would understand the outcome of those actions. For instance, an adult may deliberately take and keep someone’s unattended purse, including the money it contains. In contrast, there would not be intent if the person took the purse in order to return it to the owner.

Taking the purse you might automatically consider the action a crime, but the intent behind the action is really what determines it all.

Is the application of the law as a social control equal?

Criminal laws apply equally to everyone, independent of ascribed or achieved characteristics, such as ethnicity or social status. Hence, all who commit the same act of theft and who have the capacity to do so with intent are subject to arrest and, if convicted, will face similar consequences for this violation against society. However, research has found that although the law may be intended to apply to everyone, in practice, the application of the law is not always neutral. Members of some social groups (especially racialized groups) are more likely than others to be monitored by law enforcement, arrested, charged, found guilty, and sentenced to imprisonment (Becker, 1963; Foster et al., 2018; Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2018). We see this today in the treatment of racialized groups (see Chapter 8), and in particular, the over representation of Indigenous people in the Canadian criminal justice system

Common law system

Canada’s legal system has roots in early English common law. It was a system developed by judges, based on decisions from individual court cases that set precedents such that future cases of that nature was to be treaeted in a similar fashion.

ince its origins, common law has continuously evolved as sociocultural circumstances have broadened

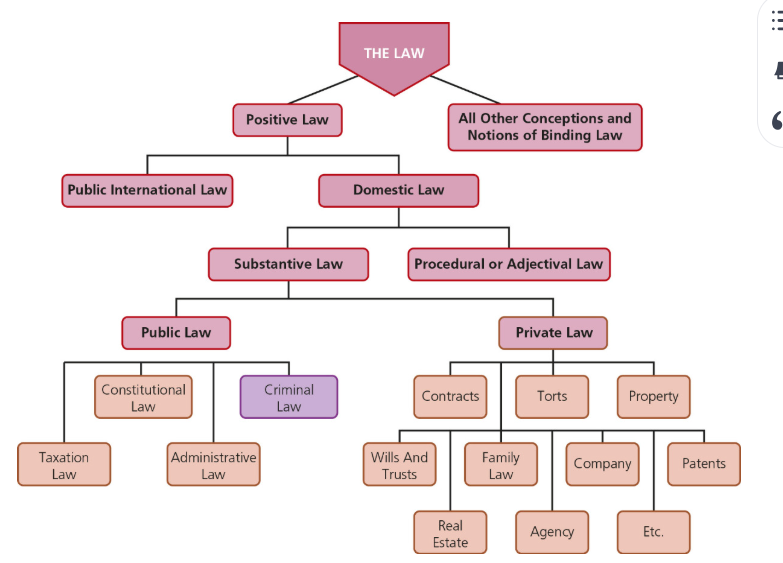

Two main types of law in Canada

private and public

Private law

concerns relationships between individuals, often in the form of contracts and agreements (e.g., marriage, property, and wills)

When there is an issue involving private law (i.e., wrongs against a person), the offending party pays for damages or otherwise compensates for the wrongdoing (Vago et al., 2018). For example, traffic laws pertaining to speed limits are developed at the provincial and municipal levels under private law, and offenders pay fines, receive demerit points, and/or pay compensation to victims.

public law

public law concerns relationships between the individual and society (e.g., constitutional law, criminal law, and taxation law)

issues under public law are considered wrongs against the state. For example, by trafficking an illegal substance, a drug dealer is considered to be causing harm to society as a whole; consequently, under public law, court cases are not between a victim (e.g., the person who became ill from the drugs they purchased) and the accused but rather between the Crown and the accused. When wrongs are against the state, the penalties are more severe (such as imprisonment). The public law in Canada, which includes the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act, and the Controlled Substances Act, is the area of law that criminologists focus their attention on. All of these acts are located on the federal government’s “Justice Laws Website”

Different levels of the perceived seriousness of crimes

Crimes are often categorized on the basis of their perceived seriousness.

Least serious: Summary conviction offenses. Cause the least harm. Punishable by max 2 yr or fine of max $5000. Ex. causing disturbance, falsifying an employment record, and taking a motor vehicle without consent.

Most serious: Indictable conviction offenses, cause the most harm. Varying penalties but can result in life in prison. ex. human trafficking, terrorism, murder.

hybrid: Some offences, such as assault or sexual assault, range in the level of seriousness depending on a number of factors (e.g., whether or not a weapon was used, whether there was a threat to a third party, and the amount of harm incurred by the victim) (Criminal Code, 1985); they are referred to as hybrid offences because they can be prosecuted as summary or indictable convictions

What is the intended victim of harm and how does it affect the serverity of the crime?

Crimes are also treated somewhat differently within the legal system depending on the intended victim of harm. Violent crimes are offences committed against a person, such as assault, sexual assault, manslaughter, and homicide. Property crimes are “economic” offences committed against property enacted to bring about financial gain, such as identity theft, credit card theft, or break and enter

how does Information on the number and nature of crimes originate (UCR)

Information on the number and nature of crimes originates with individual police agencies, which collect information using a standardized procedure, the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (UCR).

The UCR surveys are forwarded annually to Statistics Canada, which compiles the data into statistics that give us information about crimes, which can then be compared across cities and provinces, over time, and with other countries that use similar systems of recording (e.g., the United States). Statistics tell us that most of the crimes reported in 2018 in Canada were property crimes, with notable increases from previous years occurring as a result of thefts over $5,000, shoplifting of $5,000 and under, and fraud (including identity theft) (Moreau, 2019). There was a slight increase in violent crimes for 2018, largely stemming from higher rates of police-reported sexual assaults coinciding with the #Me Too movement (see Sociology Online) which peaked on social media in 2017 (Moreau, 2019). Note that crime statistics also fluctuate with changes to legislation as evident in decreases to cannabis-related offenses involving possession and increases to drug-impaired driving rates following the legalization of cannabis for recreational purposes in 2018. Overall, crime rates have gone up slightly for the last four years but are still significantly lower than what they were a decade earlier

Crime ratre

the number of criminal incidents reported to the police divided by the population

Crime severity index (CSI)

The crime severity index (CSI) takes into account the severity of crimes as well, which provides a more comprehensive overview of crime patterns.

Every criminal offence in the Criminal Code is assigned a weight based on severity (according to the sentences associated with that offence); the crime severity index is calculated each year by multiplying the volume of reported crimes by their severity. Between 2017 and 2018, the amount of crime and the severity of crime increased for half of the provinces and two territories, as reflected in higher CSI for 24 of the 35 census metropolitan areas (Moreau, 2019). Offences contributing to the increases vary from city to city. For example, Quebec had a lower CSI in 2018, attributed to large decreases in homicide and attempted murder compared to the year prior when there was a mass shooting. CSI is typically high in the Prairie Provinces as evident in the rates for Lethbridge, Regina, Winnipeg, and Saskatoon

What is the limitation of crime statistics? What can help scientists get a more accurate view of crime?

The main limitation of official statistics is that they contain information only on crimes that came to the attention of the police and resulted in convictions. This means that some crimes are underestimated (e.g., especially those involving victims who are reluctant to contact the police), some are more accurately recorded (e.g., motor vehicle thefts), and others may actually be over represented (e.g., crimes deemed a priority by individual police agencies).

To help gain a broader perspective, official statistics are sometimes supplemented by data obtained from victimization surveys. The General Social Survey (GSS), which is conducted regularly in Canada, includes questions on whether respondents have been victimized by a criminal act in the past 12 months and whether they reported the incident to the police. The 2014 GSS reported that about one in every five Canadians age 15 and over had been a victim of a criminal incident within the previous year. Yet just under one-third of these incidents were reported to the police

Victimless crimes

Criminal offenses that involve consensual relations in the exchange of illegal goods or serices.

they include drug use, prostitution, and online gambling. These are sometimes referred to as “crimes involving morality” or “crimes against public order”

The view that crimes are victimless since harm is unlikely to befall anyone outside the consenting parties is contested, particularly in cases involving highly addicting drugs, such as methamphetamine (or “crystal meth”) which overtakes its users and destroys them and their families. Crystal meth contributes to other violent and property crimes, and it is on the rise in Canadian communities (Moreau, 2019). High levels of debate are also evident in controversies over the decriminalization of prostitution.

History of prostitution laws in Canada

Prior to 2013, in Canada, the act of prostitution (exchanging money for some type of sexual behaviour) was not illegal. However, it was difficult to engage in prostitution without violating a criminal law related to prostitution, such as communicating in public in order to obtain prostitution services, operating a bawdy house (a brothel), or living off the avails of prostitution (pimping). In 2013, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down Canada’s prostitution laws, stating that they threatened the health and safety of sex trade workers and that the workers were entitled to the same level of occupational safety as employees in any other industry (CBC, 2013). Once these laws were struck down, sex trade workers were able to hire bodyguards, work in a common location (a brothel), hire drivers, and take other steps to improve their safety. Although many sex trade workers, as well as the Sex Professionals of Canada, applauded this ruling, others argued that the ruling would drive prostitution indoors, where police officers and social workers would have more difficulty identifying those who might be in need of help

The Supreme Court gave the federal government one year to develop a new prostitution law if it so chose. In 2014, the government did introduce new legislation, emphasizing the criminalization of “johns” (the customers) and pimps. Many sex trade workers, and the Sex Professionals of Canada, were outraged, arguing that the new legislation did not follow the intent of the Supreme Court’s ruling—that, in fact, they would now be at even greater risk of violence than under previous legislation. Furthermore, the new legislation explicitly casts sex trade workers as victims of sexual exploitation, devoid of agency and choice (Davies, 2015).

White collar crime

Criminal offences involving the missappropriation of financial resourves or identity theft

Coporate crime

Criminal ofences carried out by the organizations or by knowledgeabke enployees in the course of their employment.

cybercrime and organized crime

which involves criminal acts committed using computer technology. Cybercrimes are wide-ranging and include “phishing” (misleading transmissions designed to obtain passwords or other sensitive forms of personal data); “ripping” (software used to circumvent copyrights); “hacking” (infiltrating a host server); “luring” (using electronic means to contact children); and “stalking” (via frequent unwanted electronic contact), as well as other forms of organized crime (two or more people participating in illegal activitie

s for gain) such as trafficking drugs and humans (Arntfield, 2019, pp. 496–497). In May 2017, a massive cyber attack using ransomware with the name “Wanna Cry” was launched worldwide, with reports of 75,000 cases in more than 99 countries (BBC News, 2017). The attack encrypted computer user files, including those of the National Health Service in England and Scotland, and restricted access until a ransom was paid. More recently, COVID-19 has led to numerous opportunities for specialized fraud scams. For example, criminals have used people’s identities to sign up for the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and they set up fake online ads for products that are high in demand such as hand sanitizers (Government of Canada, 2020). Organized crime has also been linked to cases of COVID-phishing, counterfeit medical supplies, and unauthorized testing kits (Fitzpatrick, 2020).

The criminal justice system

The social institution responsible for the apprehension, posecution, and punishment of criminal offenders

Comrpises the police, courts, and prisons.

Begins with the commission of an act/behaviour, which may result in arrest if the police are involved.

There are three levels that law enforcement operates at in Canada, from the national RCMP to the provincial and municipal.

After initial contact with the police, who may then lay a charge (through a Crown attorney), someone accused of a crime comes into contact with the courts, which hear the case and treat the individual using principles of fairness and justice.

The court system comprises various courts (e.g., provincial courts, federal courts) that have different areas of authority.

Most cases involve summary conviction offences and are dealt with in the provincial and territorial courts. After being convicted, offenders may end up at the end point of the criminal justice system, where they serve time in a provincial or federal prison. Most convicted offenders are the responsibility of provincial correctional services. Only those who are sentenced to two or more years in prison become a federal responsibility under Correctional Service of Canada.

What criminals are federal responsibility

Those who are sentenced to two or more years in prison become the governments responsibility under Correctional Service of Canada.

how do we control criminal behaviour, what is retribution

apply social controls such as punishment.

Although punishment in the form of penalties such as paying a fine or spending time in prison is sometimes viewed as a form of retribution (a morally justified consequence, as in an “eye for an eye”), from the perspective of criminal law, the main purpose of punishment is to deter people from committing crimes.

Deterrence theory, think about specific and general deterrence

Deterrence theory rests on the assumption that punishment can be used to prevent crime.

Deterrence can operate on a specific and general level such that an offender is deterred from repeating the act in the future as a result of receiving the punishment (specific deterrence), whereas others in society also come to avoid the act by witnessing the consequences for the offender (general deterrence)

Deterrence theory originated with the classical school of criminology, a perspective from the late 18th and early 19th centuries attributed to Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794).

This school of thought rests on the premise that people are rational and that crime, therefore, is the end result of a decision-making process wherein the individual decides that the benefits of committing the act outweigh the perceived costs.

Social order can be achieved through deterrence if rules (laws) with appropriate punishments are put into writing and enforced by the state (Tierney, 2009).

How does punishment need to be enacted in order to prevent crime?

According to Beccaria 1764/1963, Punishment must be prompt, severe, and certain.

Promptness. The punishment should occur very close in time to when the actual event happened in order to establish an association between the act and its consequence.

Severity. The punishment must be severe enough to outweigh the benefits but not so severe that it constitutes torture.

Certainty. There must a high probability that an offender will be caught and that the punishment will be carried out.

Based on these three characters, why does the criminal justice system today face difficulty?

One difficulty faced by the criminal justice system today is that punishment often does not meet the three criteria simultaneously and thus cannot effectively deter future crime.

Is deterrence theory the ultimate correct way to go about social control?

Also, critics of deterrence theory call into question the very notion of deterrence itself. They suggest that offenders’ actions are often not the result of rational decision making and point out that countries with very harsh penalties, such as the death sentence, or high rates of incarceration have not managed to reduce crime rates.

What are the reasons/intentions behind incarceration, besides punishment?

Besides deterrence, punishment that involves incarceration—especially a lengthy jail sentence—generally serves as a means for protecting society from an offender who might otherwise continue to do harm.

Incarceration is also an opportunity for rehabilitating an offender, which involves helping the offender become law abiding, perhaps by providing resources to help them overcome addictions or develop anger management skills.

What does the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (1992) say about the purpose of CSC?

According to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (1992), the purpose of Correctional Service Canada is to contribute to the maintenance of a just, peaceful, and safe society by

(a) carrying out sentences imposed by courts through the safe and humane custody and supervision of offenders; and

(b) assisting in the rehabilitation of offenders and their reintegration into the community as law-abiding citizens through the provision of programs in penitentiaries and in the community. (p. 5)

Abolitionism

A movement calling for a complete overhaul or dismantling of the criminal justice system

Most societies, including Canada, have relied largely on punishment (or retribution) to deal with offenders and to protect society from further harm. Sociologists question whether the extensive use of punishment is effective for rehabilitating offenders or deterring future crime and whether it is the best overall use of societal resources (see Sociology in Practice).

Tierney (2009, pp. 2–3) notes that abolitionists claim that imprisonment

is a punitive response that deflects attention from the social circumstances and experiences that lead to offending in the first place. Ignores the reasons that the people committed the offence.

is the culmination of social control and judicial processes that discriminate on the bases of class and “race.” The criminal justice system concentrates on the crimes of the powerless rather than the crimes of the powerful; focuses on the crimes that are more negotiable rather than the big crimes that affect the whole world. Ex. persecutes a woman stealing but doesn’t do anything to a huge company breaking emissions rules.

does not provide an appropriate setting for rehabilitation, or as abolitionists put it, dispute settlement and the integration of the offender into society. On the contrary, imprisonment exacerbates social exclusion and reduces the likelihood of successful reintegration into society. This is reflected in high rates of recidivism; rehabilitation system is not great

may remove an individual from society and thus the opportunity to offend, but only in terms of the “outside world.” A great deal of offending—for example, violence and illicit drug use—occurs in prisons;

places the offender into a brutal and brutalizing enclosed society, one in which there are countless opportunities to learn new criminal skills and join new criminal networks; just adds fuel to the flames of being a criminal

increases, rather than reduces, feelings of anger, resentment, humiliation, frustration, and alienation.1

Ombudsperson

An ombudsperson is an independent body with authority to conduct thorough, impartial, independent investigations and to make recommendations to government organizations with respect to the problems of citizens.

The office of the correctional investigator (OCI) serves as an ombudsperson for federal inmates.

The OCI investigates complaints made by federal offenders (about issues involving themselves or made on behalf of other offenders) or complaints initiated by family members on behalf of inmates.

The OCI also prioritizes a variety of issues, including access to physical and mental health care, deaths in custody, and Indigenous issues (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2020a).

What is the OCI reports about the justice system currently and its indigenous population?

The OCI writes reports on its findings that include recommendations for acts that need to be taken to improve corrections in Canada. In a news release on January 21, 2020, Zinger emphasized the “deepening “Indigenization” of Canada’s correctional system,” where over-representation of Indigenous people in prison has surpassed 30 percent (see below) (Office of the Correctional Investigator, 2020b).

Zinger calls for the same urgent actions directed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the National Inquiry into Mission and Murdered Indigenous Women, and other studies, namely:

Transfer resources and responsibility to Indigenous groups and communities for the care, custody and supervision of Indigenous offenders.

Appoint a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections.

Increase access and availability of culturally relevant correctional programming.

Clarify and enhance the role of Indigenous Elders.

Improve engagement with Indigenous communities and enhance their capacity to provide reintegration services.

Enhance access to screening, diagnosis, and treatment of Indigenous offenders affected by Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.

Develop assessment and classification tools responsive to the needs and realities of Indigenous people caught up in the criminal justice system

Peacemaking criminology

Recognizing the limitations of a criminal justice system focused mainly on retribution, critical and feminist criminologists have developed alternative frameworks to the “war on crime.” For example, peacemaking criminology is a non-violent movement and approach to crime that centres on transforming individuals and society in order to reduce the suffering and social injustices that result from structural inequalities based on class, race, and gender

Basically focus on reducing the incentive to commit crime in the first place and the social strucutres that inecntive crime for certain people born with different life chances

Restorative justice

An approach to justice based on informal processes that are emphasizing healing and reparation of harm that offenders have caused victims and community members rather than focusing on punishing the offender

In this approach, the offender is required to assume responsibility for their actions and to attempt to make some kind of restitution to the victim (such as a formal apology).

Restorative justice also emphasizes the need to involve all of the stakeholders in the process of justice (victims, offenders, and other members of the community).

Finally, restorative justice rests on the premise of rebuilding relationships

Restorative justice practices including indigenous practices

Restorative justice practices have taken a number of forms, including victim–offender reconciliation programs, victim–offender mediation, community justice circles, and reparative probation programs (Winterdyk, 2019). Prior to colonization, Indigenous Peoples regularly practised restorative justice, and, more recently, attempts have been made to reimplement restorative justice programs in various communities. For example, the Tsuu T’ina Peacemaker Court in Alberta (established in 2000), the Cree-speaking and Dene-speaking courts in Saskatchewan (introduced in 2001 and 2006, respectively), the Gladue Court in Ontario (which commenced in 2001 and was expanded to three courts in 2007), and the First Nations Court in British Columbia (which opened in 2006) all utilize sanctioned traditional forms of dispute resolution (Whonnock, 2008). You can view an interactive map to locate restorative justice programs near you at

How does functionalist perspective explain the cause of deviance

Social structure causes deviance.

Durkheim said that deviance emerges from anomie. When society changes too rapidly (such as during the process of industrialization or when there is a global pandemic), people become unsure of precisely what is expected of them, and feelings of normlessness emerge. When normlessness occurs, people engage in deviant behaviour, like people hoarding TP during beginning of covid.

Why does durkheim say that a little bit of deviance is important

But Durkheim suggested that only excessive levels of deviance are harmful to society, when they disrupt the smooth running of the social order. Less than excessive levels of deviance can actually contribute to the maintenance of the social order. For instance, seeing someone being punished for a transgression reminds us of the rules; this resembles the concept of general deterrence, discussed earlier in the chapter.

Robert Merton theory of devianve, classic strain theory

Like Durkheim, Merton connected deviance to the social structure. He explained that an individual’s location within the social structure—for example, in terms of socioeconomic status—contributes to deviance.

People who occupy certain locations face more constraints than those located in other parts. These constraints, which can lead to deviance, arise from institutionalized goals and legitimate means.

The institutionalized goals of todays society include wealth, power, and prestege. From early childhood, we are socialized to aspire to earn a lot of money, be leaders rather than followers, and attain respect. This is basically the motivation to act.

We’re taught that the legitimate means for attaining these goals (socially accepted ways) include “real ways” like getting a good education, working hard, and investing money wisely.

However, Merton pointed out that society is structured in a way that some people, such as children growing up in inner-city neighbourhoods, have less access to those legitimate means. Regardless of their lack of legitimate means, most people will still dream of achieving institutionalized goals; hence, a “gap” exists between the goals and the means for obtaining them, which creates a sense of “strain.” People respond to this “gap” in different ways; that is, they engage in different modes of adaptation.

SO basically, society has told us the goals we need to achieve and taught us the socially acceptable way to achieve the goals. However this socially acceptable way is not equally accessable to all, not fair, and some people reach the goals much easier than others because of their access to the legitimate means. There is a gap between the goals and means of acheiving them.

How do people in classic strain theory respond to the gap, different modes of adaptation

Most people continue to aspire to conventional goals and do their best to pursue the legitimate means of achieving them (e.g., getting a university degree). Merton labelled this mode of adaptation conformity, and the associated behaviour is considered acceptable.

Others respond to the gap by accepting the goals of wealth, power, and prestige but rejecting the legitimate means of obtaining them. Using innovation, they find alternative means—for instance, obtaining wealth through credit card fraud, becoming powerful through gang membership, or gaining prestige by using performance-enhancing drugs to become a star athlete.

Some people engage in ritualism, giving up on the institutionalized goals but continuing to engage in the means, such as by reliably working at their low-paid jobs until retirement even though they will never earn enough money to obtain a mortgage for a home.

Others may adapt to the discrepancy between means and goals by rejecting the institutionalized goals and the legitimate means, perhaps escaping into substance abuse or not even bothering to look for work anymore—a mode of adaptation called retreatism.

Finally, some people engage in rebellion, rejecting the current goals and means but living according to an alternative set of goals and means. For instance, in the 1960s, some hippies created alternative lifestyles for themselves in communes, pursuing peace and love and sharing material goods. In the present day, extremist groups (such as Blood & Honour or Boko Haram) reflect rebellion in their use of violence to create a world that corresponds to their ideological visions.

So what does durkhiem and mertons descriptions have in common about the cause of deviance?

In Merton’s description of the structural constraints that lead some people into deviance and Durkheim’s suggestion that excessive levels of deviance emerge in contexts of anomie, we see the foundational assumptions of the functionalist perspective at work. That is, something in the social structure, rather than in the individual, causes varied forms of deviance.

Durkhiem suggests a collapse of social strucutre is the cause, where mertons is a result of placing/status in the social structure.

Theories about deviance that fall outside of the five core theoretical perspectives

learning theories propose that people learn from others to act in deviant ways (Bereska, 2022). We might learn deviant behaviour in our peer groups (e.g., how to use performance-enhancing drugs to gain a competitive advantage in sports), by being rewarded for deviant acts or imitating the deviant actions of others (e.g., by growing up in a family with a history of substance abuse or criminal activity), or by finding ways to justify our behaviours (e.g., convincing ourselves that digital piracy doesn’t really hurt anyone) (Akers, 1977; Sykes & Matza, 1957; Sutherland, 1947).

Control theories also fall outside the core theoretical perspectives in sociology but are central to studying deviance. Control theories draw attention to the factors that restrain most of us from unacceptable acts; the absence of those factors results in deviance (Bereska, 2022). In some cases, social bonds may restrain us from deviance, like not wanting to disappoint your parents or risk losing your scholarship or your job (Hirschi, 1969). In other cases, it may be basic self-control that restrains us from deviant acts. Why do you save your money for a new phone rather than stealing it? Because you have self-control (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990).

General idea of the interactionist perspective

According to interactionist perspectives, through our interactions with significant others and the generalized other, as well as the influence of the looking-glass self, we develop understandings of what acts are acceptable or unacceptable; we also come to understand ourselves in this context and choose our actions on that basis. Although some of those understandings will be shared with other people, our interactions are not identical to anybody else’s, and as such, different understandings may develop as well. Thus, you might understand facial piercing to be deviant, whereas someone else does not.

Since we all come to understand ourselves and the world around us in different ways, we may all see deviance differently and consider different things to be deviant and not to be.

Based on the core assumptions of the interactionist perspective are several specific explanations for how we develop understandings of deviance and normality.

Lemerts labelling theory, what is primary deviance

Edwin Lemert’s (1951) labelling theory emerges from this interactionist foundation. Lemert states that we all engage in acts of primary deviance—minor acts that are done rarely or infrequently (e.g., drinking alcohol to excess).

Little acts of deviance that many of us engage in occasionally.

Because infrequent transgressions are likely to go undetected, people are able to maintain a non-deviant self-image. However, with more frequent acts of deviance, the chances of detection are greater. Lemert argues that getting caught at deviance is the impetus for a chain of events that change how people are treated and how they come to understand and identify themselves.

For example, getting caught drinking alcohol at work may lead an employer to label an employee a “problem drinker” or “alcoholic.” Because of that label, people start to treat that person differently; a person who is labelled a problem drinker at work may be reprimanded by the boss, avoided by coworkers, or required to seek treatment. Perceived as deviant, the legitimate world starts to reject them, and only similar others in the deviant world, such as one’s fellow patrons of the familiar bar, continue to accept them.

Basically not just the persons actions but the people around them influence their identity and if they engage in deviant behaviour.

Secondary deviance

Also, the deviant comes to view themselves differently as a result of the label, increasingly accepts the label, and builds a lifestyle and an identity around it—this is known as secondary deviance. A person who has been labelled a “problem drinker” may drink even more to cope with deteriorating relationships at work and/or at home because they have internalized that label and are acting in accordance with its role.

Chronic deviance as a lifestyle. People conform to the label you enforce upon them.

Stigmatization

The process by which individuals are excluded because of particular behavoiurs/characteristics.

Goffman (1963) spoke of a similar process, whereby people who engage in certain acts or who have particular characteristics face stigmatization in society; that is, they become treated as “outsiders” once they are labelled as such. Those individuals may respond to stigmatization in a number of ways, ranging from trying to hide that stigmatized characteristic to developing a lifestyle around it and publicly embracing it. Thus, the person who often drinks to excess may try to prevent detection by using mouthwash or drinking vodka out of a water bottle, or alternatively may be known to friends as throwing the best parties because of a well-stocked bar.

Conflict perspective explains deviance

According to the conflict perspectives, structures of power determine which behaviours or characteristics are defined and treated as deviant. Although different conflict scholars describe that structure of power in distinct ways (see Chapter 1), they all agree that holding power enables groups to define their own behaviours as “normal” while defining the behaviours of others as “deviant” and in need of social control. The powerful then also have the means to enforce those measures of social control, whether in creating criminal laws, legislating physical appearance (as with Bill 21 on the wearing religious symbols, which you learned about in Chapter 3), or racial profiling by law enforcement.

Feminist perspective explains deviance

Feminist perspectives draw attention to facets of deviance such as the differential standards that women and men face in determining what is considered deviant and the varying experiences they have of being socially typed as deviant and subjected to measures of social control. For instance, they point out that what are considered acceptable behaviours/characteristics in society are gendered. A male who wishes to be a daycare worker is more likely to be considered deviant than a woman with that same wish, whereas a woman who wants to work on an oil rig is more likely to be socially typed as deviant than a male in that position (Bereska, 2022). For example, some scholars have explored how societal views of prostitution emerge from larger discourses about women’s sexuality, others draw attention to systemic violence against Indigenous women and girls, and yet others have analyzed how norms governing motherhood are created, reinforced, and interpreted in specific situations (Clevenger, 2016; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019; Shdaimah & Leon, 2015). As with other critical theories, feminist perspectives on deviance emphasize the broader social processes that result in certain perceptions of and reactions to deviance carrying more weight in society as a whole.

How are social controls applied in casual day to day life?

As you have learned in this chapter, social control is not just directed at “some people”; it is directed at each one of us, for a variety of reasons. Simply by walking across your campus, you can see messages about the actions that are considered acceptable or unacceptable and forms of social control. As you walk across campus looking for “the strange in the familiar” (see Chapter 1), look closely at the following: the posters located on bulletin boards; the physical structure of campus buildings (e.g., the behaviours that are expected, condoned, frowned upon, or prohibited in particular locations); the university’s policies and regulations; and the social interactions of people (e.g., in classrooms, hallways, library, cafeteria, fitness centre, pubs).

Postmodern description of deviance, self surveillance

From a postmodern perspective, Foucault (1995) focused his attention, in part, on the internalization of social control. He focused on why we often don’t have to be controlled by others but actually control our own behaviours through self-surveillance. We live in a society where we are constantly monitored, or at least feel that we are being monitored, through surveillance cameras, photo radar, bureaucratic mechanisms that influence everything from who is/is not allowed to drive to what class you must take as a prerequisite for another course, and strangers judging our physical appearance when we walk down the street. Because of this perception of ongoing monitoring, we eventually monitor our own behaviours—we look in the mirror before leaving the house to ensure that we look “okay,” or slow down when we see a digitized speed sign farther up the street.

The extent to which our lives are intertwined with social media today has implications for surveillance. If we are active on social media, we can be under surveillance by others at any time of the day or night. A selfie that we post this morning might be viewed—and judged—by others immediately, two hours later, three weeks later, or even years later. Duffy and Chan (2019) find that this “imagined surveillance” (p. 119) of others has implications for college students’ self-surveillance and use of social media.

When deciding what to post (or not) on social media, they think about who might see it. Their friends? The person they are dating? Their grandparents? Their employer? Thinking about who the audience might be affects their actions on social media (i.e., what they will and will not post). You might even know some individuals who have multiple social media accounts, under different names, for varied audiences. For instance, they might use their real names on one social media platform that employers or potential employers can see—and post only material that frames them in a positive light. On another social media platform, they might create an account under a slightly different name that only their friends will see.