Speakers accent

1/18

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

19 Terms

Tutorial 9: Linking Ideas

Rating emotional speech based on the dimensions of valence and activation results in fairly distinct categories, although there is some overlap Rating emotions in this way allows us to observe phonetic/acoustic patterns Valence (moderate correlations) High F0 and large F0 range Low jitter High HNR Activation (strong correlations) High F0 and large F0 range Low jitter High shimmer Low SPI

Inter-speaker variation: low-level differences

Physical differences speaker physical size affects the size of the larynx and the size of the vocal tract Physiological differences speakers vary in the precise anatomy/physiology of the vocal apparatus and its neural control Phonetic differences speakers may vary in their default pitch or voice quality speakers may use different habitual settings for jaw height, lip position, or velum height speakers may use different habitual gestures for the execution of phonological units speakers may have prosodic differences: preferences for certain intonation, speaking rate, rhythm, or fluency

Inter-speaker variation: high-level differences

Phonological differences speaker differences can also show up as changes to the inventory of phonological segments used in the lexicon, or to distributional differences in how the inventory is exploited in different groups of words Lexical & syntactic differences speakers may show preferences for particular words, or preferences for certain word sequences, or preferences for certain syntactic constructions Cognitive & social differences speakers as individuals may show preferences for certain topics of discussion, express certain attitudes to events in the world, be knowledgeable about certain fields, differ in intelligence or personality

Intra-speaker variation

Content: changes to the linguistic content can affect the distribution of fundamental frequency, the range of spectral qualities, and spectral dynamics Style: changes to the required intelligibility, familiarity of the interlocutor, or formality of the situation Emotion: the nature of the emotional state of the speaker and their level of arousal will affect their speech Health: the health of the speaker may change Age: people’s speech may vary as they get older Acoustic environment & channel: the recording itself can be affected by noise, reverberation, or audio channel Disguise/imitation: the speaker may be acting, imitating another speaker, or disguising their voice

Terminology

An accent is simply a particular manner or style of pronunciation. Everyone, in this definition, has an accent. A dialect refers to the types and meanings of the words available to a speaker and the range of grammatical patterns into which they can be combined. A dialect may be associated with more than one accent. A language is made up from a group of related dialects and their associated accents. How dialects are grouped into languages can be geopolitical decision rather than a linguistic one. Are they mutually intelligible? An idiolect is the combination of dialect and accent for one particular speaker.

Accent variation

Phonological Inventory: sound inventory used in the mental lexicon to represent the pronunciation of words can vary from speaker to speaker. e.g., “cot”, “caught” (1 or 2 vowels) e.g., “witch”, “which” (1 or 2 consonants) Lexical Distribution: distributional differences in terms of which segments are used in which words e.g., “bath”, “plant”, “pass” (use of /A/, /æ/) e.g., “cup”, “rub” (use of /2/, /U/) e.g., “farm” (post-vocalic /ô/ or not?)

Accent variation

Allophonic variation: variations can occur in terms of the choice and distribution of allophones, for example: clear and dark variants of /l/ replacement of syllable-final /t/ with [P] or inter-syllabic /t/ with [R] or [P] Segmental quality: changes in articulatory implementation of the same phonemes, particularly vowels e.g., Northern Irish English /aU/ as [5Y]∼[30] Prosody: variations also exist in prosody, both in terms of syllable timing and in terms of intonation e.g., High-Rising Terminal intonation (“uptalk”)

Accent variation: second language (L2) accent

The phonetic and phonological properties of a speaker’s first language may influence their pronunciation of a second language, particularly if that is learned later in life. In this area of study, open questions include: whether it is possible to predict which sounds will be problematic knowing the phonology of the two languages whether non-native forms persist because of problems in production or perception whether an ability to learn native-like pronunciation worsens with age

How do innovations arise? (sound change actuation)

Misperception hearing one sound as another e.g., “tough” Misinterpretation choose wrong phonological form e.g., “an eke-name” cerise → “cherries” Multiple languages Mixing of cultures e.g., Multicultural London English

Why do innovations spread? (sound change diffusion)

Pronunciation variants become social symbols Example of Ethnocentrism “Ethnocentrism is a nearly universal syndrome of attitudes and behaviors. The attitudes include seeing one’s own group (the in-group) as virtuous and superior and an out-group as contemptible and inferior” Axelrod & Hammond (2003) Regional & non-regional accents Geographical considerations separation + time = divergence

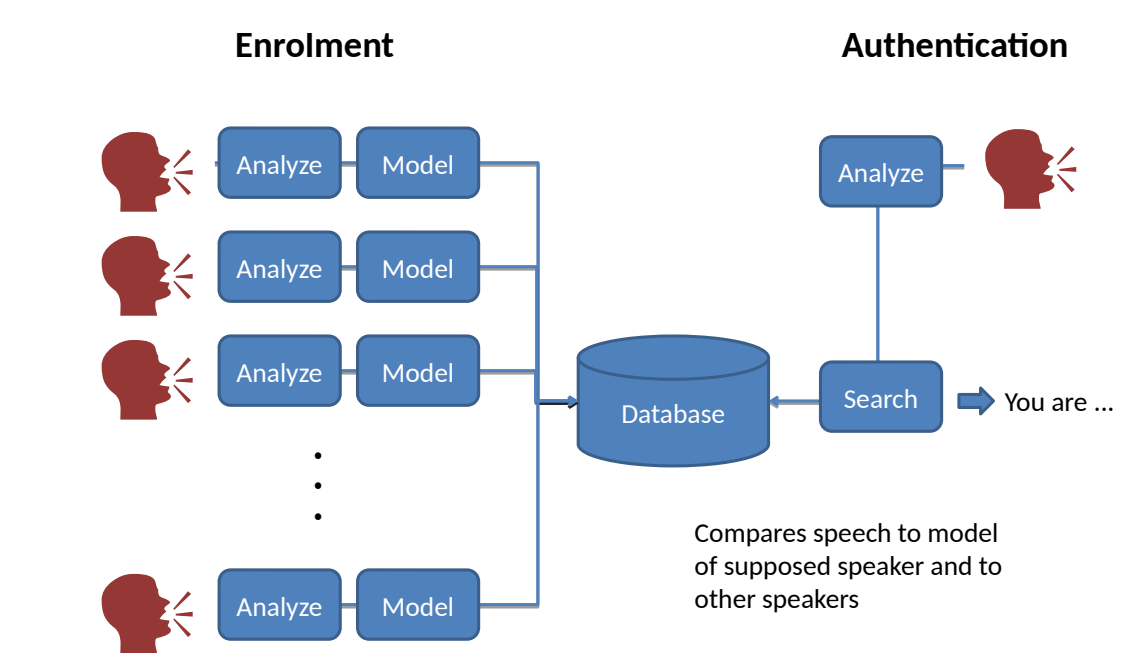

Speaker recognition

Comparing to only the average form of each known speaker (left) is misleading You also need to take into account the possible variability of other speakers (right)

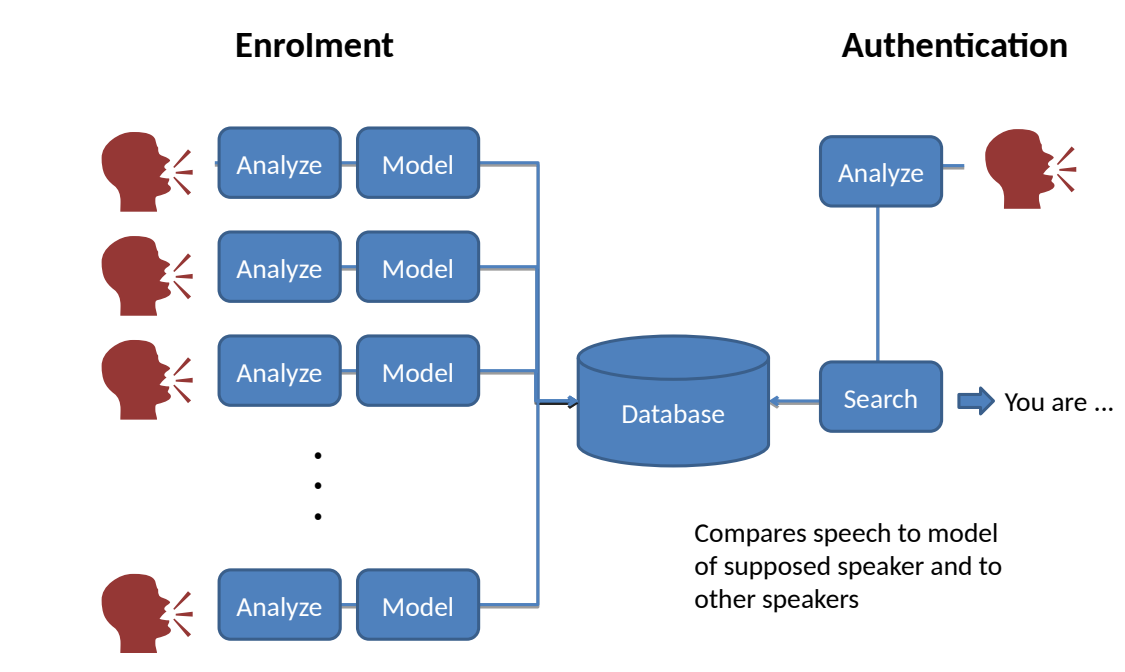

Automatic speaker recognition

Established technology for authentication Provides mechanism for confirmation of identity Challenges someone to speak a pre-enrolled text, or even a new text Establishes likelihood that speaker is who they say Error rates ∼ 1% False rejection of true speaker: 1 in 100 False acceptance of impostor: 1 in 100

Speaker recognition flow: train on features, test on new audio

Which speech features?

Which speech features?

Prefer low-level features independent of what was said only require small amount of data Prefer features less easy for speaker to change not: pitch, voice quality but: spectral qualities affected by vocal tract size, habitual settings, and accent Prefer features that vary widely across speakers combinations of spectral properties rather than single formant frequencies

Value of predictable speech content

Speakers are easier to identify if you know what they are saying not just the “sound” of their voice but how they use sound to encode linguistic messages gives access to idiolect, their personal accent Automated systems work better when they are “text-dependent” (reading the same text, saying the same phrase)

Forensic speaker approach and goals

Approaches Listen for idiosyncratic habits pronunciation voice quality prosody Back up with instrumental measures fundamental frequency timing voice quality formant frequencies spectral shape of fricatives Goals Speaker comparison e.g., two speech recordings, one as evidence from a crime and one from the suspect: are they the same person? Speaker identification e.g., identify from a recording who the speaker is

Accent studies

Ground-breaking work by William Labov (1966) on variation in New Yorker accent (“fourth floor”) Social class post-vocalic /ô/ /D/ as [d] Middle class 25% 17% Working class 13% 45% Lower class 11% 56% Modern corpus studies: Accents of the British Isles Accents of North Carolina New Zealand English Intonational varieties of English

summary

Speakers vary at all levels in the linguistic hierarchy – from the vocal tract to linguistic habits Speakers are highly variable in the way they use speech It is not always possible to identify or discriminate speakers from their voices First language accents arise and change through the copying of innovations for social purposes Second language accents are strongly influenced by the phonetic and phonological form of the speaker’s first language Innovations arise from sound change, which lead over time to accent differences Modern accent studies use data-driven experimental methods to automatically differentiate and cluster speakers