Psych of lang final (lectures and textbook)

1/212

Earn XP

Description and Tags

sorry if things overlap from lectures to textbook! but if they do that means they are probably the most important :)

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

213 Terms

Monolingual

A person who can speak only one language

Key points:

Less common globally

Most common in countries with little linguistic diversity

Bilingual

A person who can speak two or more languages.

Key points:

Most people in the world are ____

____ rarely speak all languages with equal proficiency

Balanced Bilingual

A person who grows up speaking two languages and can communicate equally well in both.

Key points:

Very rare

Both languages have equal proficiency in speaking, understanding, reading, and writing

Unbalanced Bilingual

A bilingual person with greater proficiency in one language (dominant language).

Key points:

Most bilinguals fall into this category

The weaker language is often the second language (L2)

Language–Dialect Distinction

The distinction is more political than linguistic.

Examples:

French vs Italian → separate languages because separate countries

Chinese “dialects” → often not mutually intelligible but considered one language

Dialect

A regional or social variety of a language.

Examples:

British English vs American English

Southern vs Northern dialects

Mutual Intelligibility

The degree to which speakers of two varieties can understand each other.

Examples:

American and British English → mutually intelligible

Mandarin and Cantonese → not mutually intelligible

Social Attitudes & Mutual Intelligibility

Key insight:

Understanding is influenced by social bias, not just linguistic ability

Example: Scandinavian languages

Swedes understand Danish poorly

Danes understand Swedish well

Preschool children understand both equally → bias develops in adulthood

Heritage Language

The language spoken at home and tied to family and cultural identity.

Key points:

Easier for expressing emotions and family topics

Often maintained by first-generation immigrants

Societal Language

The language spoken by the majority in a society.

Key points:

Used for school, work, and public life

May feel easier for abstract or formal topics

First generation

keep heritage identity, speak societal language with accent

Accent switching can occur depending on social group

Second generation

aim to assimilate, speak societal language with local accent

Accent switching can occur depending on social group

Codeswitching

Switching between languages within a single conversation or sentence.

Key points:

Can happen between sentences or mid-sentence

Seen even in young bilingual children

Rule-governed, not random

Organization of the Bilingual Mind — Lexical Decision Task

Participants decide quickly whether a letter string is a real word.

Key finding:

Bilinguals activate both languages simultaneously

Example:

NOCHE → not English, but Spanish word

Slower reaction time for Spanish-English bilinguals

Cross-Language Priming

A word in one language speeds recognition of a related word in another language.

Example:

German ARZT → primes English NURSE

Depends on number of shared senses

L2 → L1 priming more likely

L1 → L2 priming less likely

Eye-Tracking Evidence

Words are recognized before they’re fully spoken.

Example:

Russian marka → stamp

English marker

Russian-English bilinguals look at both objects

Translation Equivalents

Words in different languages referring to the same concept.

Example:

dog ↔ chien

Mutual Exclusivity (Children)

Children assume a new word refers to a new concept.

Key exception:

Bilingual children do not apply this across languages

Shows awareness of two linguistic systems

Cognates

Words with similar form and meaning across languages.

Examples:

English–German (shared origin)

English–French (borrowing)

Interlingual Homographs

Words that look the same across languages but differ in meaning.

Key point:

Both meanings are briefly activated

Examples:

German Gift → poison

German Chef → boss

Dutch spot → mockery

The Bilingual Disadvantage — Observed Disadvantages

Smaller vocabulary in each language

More difficulty retrieving words

More tip-of-the-tongue states

Important:

Measurable in labs

No major impact on daily communication

Tip-of-the-Tongue (ToT)

Temporary inability to retrieve a known word.

More common when:

Word is low frequency

Speaker is bilingual

Lexical Decision Differences — Monolinguals

rely on surface familiarity

Lexical Decision Differences — Bilinguals

rely on meaning

Bilinguals process semantics even for nonwords

Explaining the Bilingual Disadvantage — Weaker Links Hypothesis

Bilinguals use each word less often

Lower frequency → weaker memory links

Leads to slower lexical access

Interference Hypothesis

Both languages are always active

Translation equivalents compete

Requires constant inhibition

Example:

DOG vs CHIEN interference

Models of the Bilingual Lexicon — Revised Hierarchical Model

Separate lexicons for each language

Shared conceptual system

Strength of links depends on proficiency

Balanced bilingual:

Strong links both ways

Unbalanced bilingual:

Easier L2 → L1 translation

Priming mostly L1 → L2

Sense Model — Core Idea

Words have multiple meanings (senses) that don’t fully overlap across languages.

Concrete words

more shared senses

Faster translation

Abstract words

less overlap

Picture Naming Evidence

Chinese-typical images → faster in Chinese

Western-typical images → faster in English

Meaning includes sensory & visual information

The Bilingual Advantage — Metalinguistic Awareness

Understanding how language works.

Benefits:

Better communication

Greater creativity and problem solving

Adaptive Control Hypothesis

Language control strengthens general cognitive control.

Result:

Better multitasking

Faster task switching

Executive Control Components

Interference inhibition

Selective attention

Mental flexibility

Simon Task

An experimental procedure that requires participants to respond to the colour of a stimulus regardless of its location

Bilinguals show less slowdown on incongruent trials

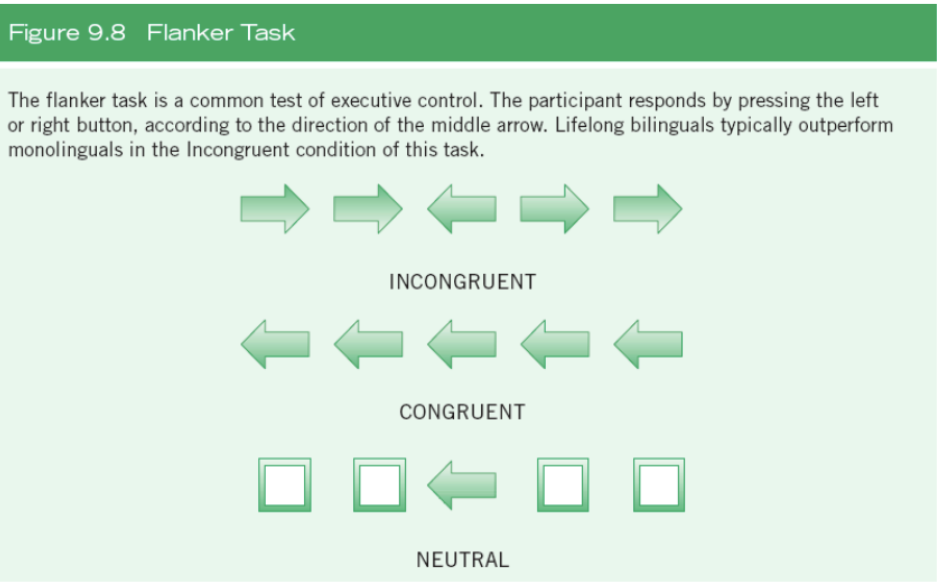

Flanker Task

Measure of executive control

Participants respond to direction of central arrow, regardless of direction other arrows are pointing

Executive Control Across Lifespan — Monolinguals

peaks in young adulthood

EC low in childhood, peaks in young adulthood, declines in later adulthood

Executive Control Across Lifespan — Bilinguals

develops early, remains high

Language Development (Infancy) — Protoconversation

Early social exchanges between an infant and a caregiver that resemble conversations even though the infant is not yet using words.

Protoconversation (more details)

Key characteristics:

Turn-taking (infant does not vocalize over caregiver)

Mutual gaze

Facial expressions

Gestures

Vocalizations

What infants learn (before words):

Conversational timing

Volume and pitch

Emotional expression

Gestural communication (e.g., pointing)

Why it matters:

teach the structure of conversation long before language itself develops.

Infant Attention to Face (Eyes vs Mouth)

Developmental pattern:

~4 months: Infants focus mostly on the caregiver’s eyes

5–12 months: Shift attention more to the mouth

After 12 months: Shift back to the eyes

Why the shift happens:

Mouth provides articulatory information for speech sounds

Eyes provide emotional and social information

Language Comprehension Difficulty & Visual Attention

When comprehension is difficult, both infants and adults look more at the speaker’s mouth

Examples:

12-month-olds hearing an unfamiliar language

Adults listening to a language they don’t understand

Conclusion:

Looking at the mouth supports speech perception; looking at eyes supports emotion understanding.

Speaker Variability

Early stage:

Infants initially encode words with:

Speaker voice

Accent

Emotional inflection

By 7–8 months:

Infants recognize familiar words across different speakers

Can generalize across prosodic contexts

Prosodic context

Rhythm, stress, and intonation of speech

Walking & Talking — Motor Development as a Catalyst

Motor development triggers advances in cognitive, social, and language development.

Babbling & Motor Rhythms — Reduplicated babbling

Repeated CV syllables (e.g., da-da-da, ma-ma-ma)

Babbling & Motor Rhythms — Timing

Emerges around same time as rhythmic arm movements (e.g., shaking a rattle)

Babbling & Motor Rhythms — Interpretation

Shared neural capacity for rhythmic movement in limbs and speech articulators.

Self-Locomotion & Language Explosion

Key milestone:

Crawling or walking

Effects:

Active exploration

Hands free to manipulate objects

More independent interactions

Why language improves:

More objects encountered → more labels needed

More caregiver speech

More complex social interactions

Walking Changes Communication

New communication dynamics:

Toddler asserts will

Challenges authority

Begins “talking back”

Result:

Rich sociolinguistic interactions

Vocabulary spurt in second year

Practical reason parents talk more:

To keep the child safe (“stop,” “don’t touch,” etc.)

Caregiver Interaction — Business Talk

Caregiver speech focused on instructions and prohibitions.

Examples:

“Stop.”

“Don’t touch that.”

“Drink your milk.”

Risk:

If dominant, increases likelihood of language delays or disorders.

Caregiver Interaction — Descriptive Talk

Speech that labels objects and comments on shared attention.

Examples:

“That’s a wagon.” to a one year old

“That’s a red wagon like yours.” to a two year old

Why it matters:

Drives higher-order language development

Encourages vocabulary growth and syntax

Key principle:

Language development thrives on talk with no immediate goal.

Critical Period

A biologically determined window during which language must be acquired for full proficiency.

Case Studies — Genie

Extreme deprivation

Failed to acquire full grammar

Evidence for critical period

Case Studies — Victor (Wild Boy of Aveyron)

Lived without language input

Limited success learning language

Case Studies — Oxana Malaya

Lived with dogs

Later acquired language

Shows some plasticity but limits remain

The Preschool Years — Fast Mapping

Learning a new word after one or two exposures.

Age:

Begins around 2 years

Limitation:

Memory for word may fade without reinforcement

The Preschool Years — Slow Mapping

Gradual consolidation of a word’s pronunciation and meaning over multiple exposures.

Importance:

Essential for long-term vocabulary development

Lexical Configuration

Result of fast mapping

Linking sound → meaning

Lexical engagement

Result of slow mapping

Linking word to other known words and concepts

Mental Lexicon Structure

Words are connected by:

Synonyms

Antonyms

Categories

Co-occurrence frequency

Key insight:

Vocabulary is a network, not a list.

Preschool Categories — Category Hierarchies

Superordinate (animal)

Basic level (dog) ← learned first

Subordinate (dalmatian)

Basic Level Categories

Categories that are neither too broad nor too specific.

Examples:

Dog

Chair

Why its important:

Cognitively salient

Learned first

Scaffold learning of other categories

Syntax Development — Pattern-Based Learning

Preschoolers rely on familiar word sequences

Example:

Easier: sit in your chair

Harder: sit in your truck

Conclusion:

Abstract grammatical rules emerge later.

Oral Language & Academic Success

Strong predictor:

Oral narrative ability in kindergarten

Assessment method:

Picture-based storytelling

Skills involved:

Pronunciation

Vocabulary

Syntax

Discourse structure

Oral language supports

Reading

Writing

Math

Decoding

Converting print into spoken word forms.

Requires:

Print knowledge

Alphabet knowledge

Phonological awareness

Short- and long-term memory

Phonological Short-Term Memory

Role:

Holds sound sequences during decoding

Poor readers:

Forget beginning of word before reaching the end

Working memory overload

Orthography

Spelling system of a language

Deep Orthography (English)

Inconsistent mapping between letters and sounds

Examples:

Tough

Though

Through

Bough

Consequence:

Readers rely heavily on spoken vocabulary.

Vocabulary Growth

Growth continues throughout life

Most rapid during school years

~40,000 words learned between grades 1–12

Vocabulary & Literacy

Large vocabulary → reading success

Small vocabulary → academic risk

Contextual Abstraction

Inferring word meaning from surrounding text.

Depends on:

Word difficulty

Text complexity

Number of unknown words

Morphological Analysis

Breaking words into morphemes to infer meaning.

Example:

violinist → someone who plays violin

Morphological Awareness

Understanding that words contain meaningful units.

Improves with instruction

Adulthood & Aging — Auditory Decline

Sensory level:

Cochlear damage

Perceptual level:

Brain processing changes

Compensation Strategies — Older adults

Have larger vocabularies

Use context and semantics

Rely on pragmatic knowledge

Elderspeak

Simplified speech used with older adults.

Features:

Slow rate

Simple sentences

Repetition

Parallel:

Infant-directed speech

Language Development (Adolescence) — Teen Speech Characteristics

Fillers: like, you know

Speed prioritized over accuracy

More errors in demanding tasks

Syntax vs Vocabulary

More complex syntax

Simpler vocabulary

More fillers

Breath Pausing

Fewer pauses

Pauses at major linguistic boundaries (sentences)

The Whorf Hypothesis (Sapir–Whorf)

The language we speak affects how we think and perceive the world.

Linguistic Determinism (Strong Version)

People can only perceive and categorize the world according to the structures provided by their language.

Implication:

Thought is constrained by language

Without words for something, you cannot think about it

Status:

Generally rejected as too extreme

Linguistic Relativity (Weak Version)

The language people speak influences (but does not determine) how they perceive and think.

Status:

Widely accepted

Innatism

Perceptual and cognitive processes are not influenced by language at all.

Position on spectrum:

Innatism ← Linguistic Relativity → Linguistic Determinism

Language & Thought — Verbal Thinking

Inner dialogue

Language-based reasoning

Language & Thought — Visual Thinking

Mental imagery

Spatial representations

Aphantasia

Inability to voluntarily form mental images.

Significance:

Demonstrates individual differences in thinking styles

Whorf’s Observations (1956)

Much conscious thought is linguistic

Languages carve up the world differently

Conclusion:

Language must influence thought

Colour Perception

Visible light spectrum is continuous

Humans perceive discrete colour categories

Language Differences

Languages differ in number of basic colour terms

Supports linguistic relativity

Universal Patterns

Common colour category centers across languages

Supports innatism

Focal Colours

Best example of a colour category.

Six universal focal colours:

Black

White

Red

Green

Yellow

Blue

Categorical Perception of Colour — Sorting Task

Participants sort colour chips into groups.

Findings:

Blue–green speakers sort into two categories

Grue speakers (one word for blue & green) sort differently

Grue Speakers

Speakers whose language has one term for both blue and green.

Boundary Disagreement

Blue–green speakers agree on boundary

Grue speakers disagree

Delayed Match-to-Sample Task

Procedure:

See target colour

Delay

Choose which item matches

Result:

Blue–green speakers perform better on blue vs green distinctions

Ekman’s Universal Emotions

Original six:

Happiness

Sadness

Fear

Surprise

Anger

Disgust

Later added:

Contempt

Picture Naming Task

Participants name emotion in face

Large variability within and across cultures

Picture Matching Task

Decide if two faces show same emotion

Even more disagreement