ARTH 102 - High Renaissance & Venetian Renaissance

1/16

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

17 Terms

The High Renaissance

c. 1495-1520 (late 15th, early 16th century), sought to represent the divine in figures of ideal beauty and perfection, studied human anatomy, center of study and development was Florence, sometimes Rome

da Vinci, “The Virgin of the Rocks”, c. 1485, oil on panel.

Commissioned by the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, a lay brotherhood, for their chapel in the church of San Francisco Grande in Milan, this version of the painting was never delivered. Portrays an imagined meeting of John the Bapist and Jesus as infants in the presence of the Virgin and an angel, the figure are at the edge of a pond, framed by a grotto. Characteristic of the High Ren: balanced pyramidal comp, complexity of the poses, use of atmospheric perspective. Characteristic of Leos interests and technique: the landscape, whch is not a specific location but based upon his extensive studies of the natural world, and the use of 'sfumato’ (italian for smoky), a variant of chiaroscuro, it is more subtle in its transitions of color and tone, producing an overall atmospheric quality from which form and volume emerge.

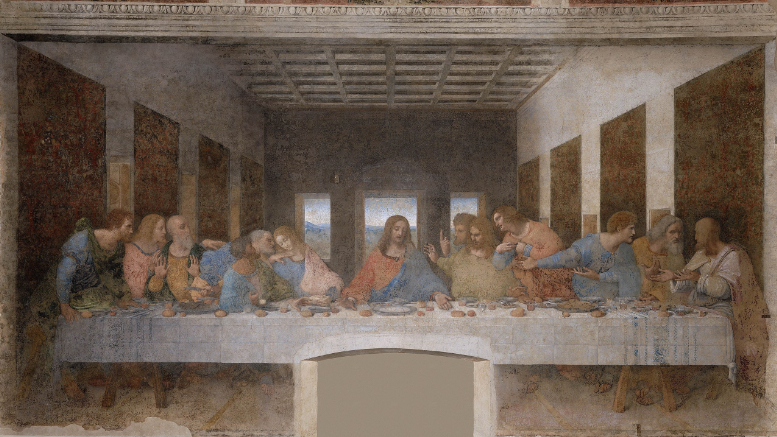

Da Vinci’s Last Supper, 1495-98, oil and tempera fresco.

Commissioned by the Duke of Milan for the refectory (dining hall) of the Dominican monastery. Leo illustrates the narrative moment in which the apostles react to Christ’s announcement that one of them will betray him, organizing them in four groups of 3, each with a distinct gesture and emotional composition, framed by the light of a window from the rear wall. Christ, in contrast, is calm and in a pyramidal pose at the center of the comp, framed by the light of a window from the rear wall. Leo’s use of linear perspective is seen in the receding lines of the ceiling coffers and the wall tapestries, the vanishing point positioned behind Christ’s head.

Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, c. 1503-05, oil on panel. Sitter was Lisa Gherardini, wife of a wealthy Florentine merchant, but pictured in simple attire and unadorned. Portrait innovative bc: 3 quarter pose (her torso turned towards the viewer as opposed to being in strict profile), half length pose (seen from the waist), inclusion of the hands. Landscape is a combo of Leo’s studies of the natural world rather than a specific location. Mysterious forms and hazy rendering contribute to what has been described as the mystery of the sitter’s expression.

Michelangelo’s Pieta, 1498-1500, Marble statue. Commissioned by a French cardinal for his funeral chapel in the Old Saint Peter’s church in Rome.

A Pietá (meaning pity or compassion), which refers to the image of the Virgin cradling the body of her dead son, was a more popular subject in northern Europe. The understated emotion and technical skill (note how the texture of the skin and the weight of the figure of Christ are conveyed), apparent in this early work, established Michelangelo’s career.

Michelangelo

1475-1564, apprenticed in painting. Learned the basics of sculpture by studying the Medici’s collection of antique statues while living with them, and from the overseer of that collection, who had been a student of Donatello.

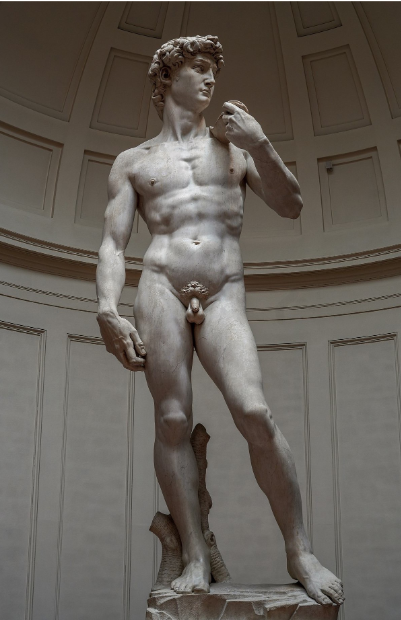

Michelangelo’s David, 1501-04, Marble. Commissioned for an exterior butress (support) of the cathedral of Florence, 40’ above street level, the statue was instead placed in the Piazza della Signoria, in front of Florence’s town hall as a

symbol of the restored Florentine republic. The figure exemplifies Michelangelo’s mastery of the human form, which he learned from his careful studies of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture.

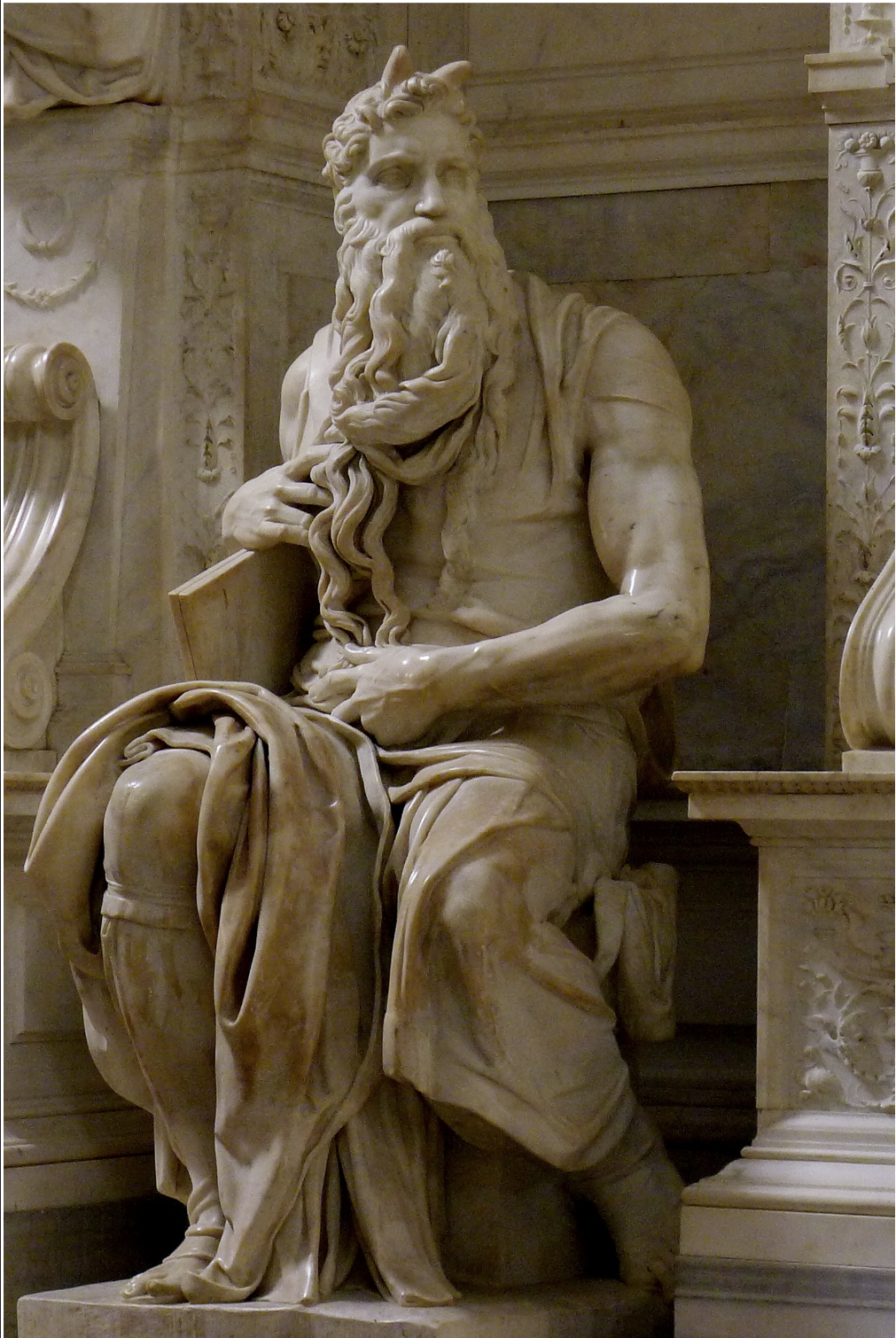

Michelangelo, Moses, 1513-1515, Marble, San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

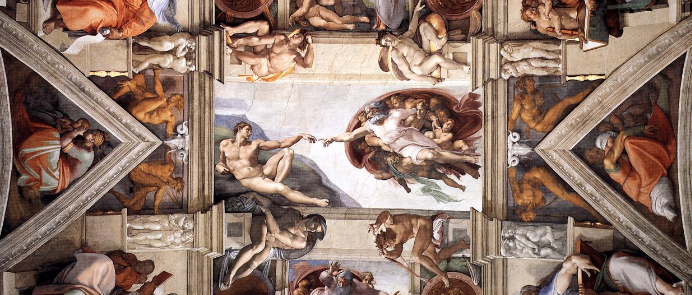

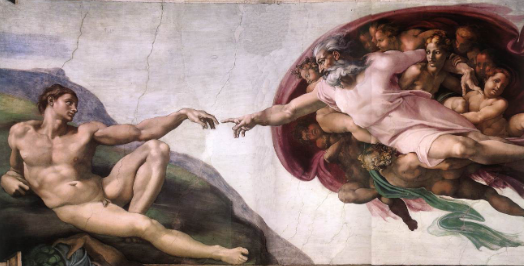

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, ceiling frescoes, 1508-1512, the Vatican. Michelangelo subdivided the barrel vault ceiling of the Chapel with illusionistic transverse arches framing nine scenes from the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis that foretell the coming of Christ

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel. Nude male figures (“ignudi”), frame the scenes. Acorns, which appear with some of the ignudi, are a reference to Pope Julius’s family name, delle Rovere (rovere meaning oak). Michelangelo symbolizes the force of life being transmitted by God to the still listless figure of Adam through their outstretched arms and fingers, which are about to meet.

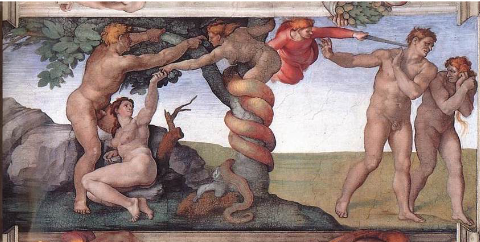

Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel, The Fall of Man and The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

Two of the four frescos Raphael painted, The Parnassus, left, 1509-10, and The School of Athens, right, 1510-11.

Raphael was called to Rome in 1508 by Pope Julius II to decorate what was then the pope’s library at the Vatican Palace (now the Stanza della Segnatura, Room of the Signature). The frescos represent the four areas of knowledge as conceived in the 16th century, theology, philosophy,

the literary arts, and justice. Together, they are a summation of High Renaissance humanism in uniting humanist classical learning, what was understood about the world through reason and science, with the teachings of the Church, God and the divine.

Raphael’s The School of Athens, 1509, fresco. At the center are the two great classical philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, representing their distinct philosophical schools of thought, the theoretical and the empirical. They are surrounded by other ancient classical thinkers, positioned within an imagined classical Roman architectural setting of receding barrel vault arches. At left and right are illusionistic renderings of statues of Apollo, the Greek and Roman god of music and poetry, and Athena (Greek)/ Minerva (Roman), goddess of war and wisdom. The single-point perspective places the vanishing point behind the two

philosophers. The complexity, grace, and sculptural quality of the varied figures in combination with the composition reflect the influence of both Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Compared to Perugino’s Christ Handling the Keys to St. Peter, bc of the single point perspective and similar composition. Raphael was a student of his.

Plato (428-348 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE),in the center, identified by, among other things, their books, The Timaeus (Plato) and Ethics (Aristotle). Pythagoras, on Plato’s side of the fresco, discovered the laws of mathematics. Euclid, on Aristotle’s side, developed the foundations of geometry. His features

are thought to be based on those of the High Renaissance architect, Bramante. Heraclitus (front left, thinking while laying against a desk), who influenced Plato. His features are based upon those of Michelangelo and his pose on Michelangelo’s Isaiah.

Venitian art in the Renaissance

Venice became a major artistic center towards the end of the 15th century.

Venetian painting is characterized by its use of color and, like the art of Northern Europe, its masterful rendering of light and atmosphere. Also as in the north, oil paint was the dominant medium. In Venice, it was applied on white ground in translucent layers. Because it dries slowly, oil paint can be subtly blended.

Venetian artists introduced a new kind of genre to painting, the pastoral concert. Its subject was the idyllic landscape, populated with gods, nymphs, shepherds, and peasants. As a genre, it became one of the most important contributions of Renaissance Venice, with an impact lasting into the 19th century.

Giovanni Bellini’s (c. 1430-1507) Saint Francis in the Desert c. 1475-1480, oin on panel.

Saint Francis, founder of the Franciscan order (1209), had, while on a retreat in the wilderness, a vision of receiving the stigmata (the wounds of Christ) from an angel. Usually represented literally, Bellini, in the humanist tradition of the Renaissance, represents the divine by the natural light bathing Saint Francis as he

experiences his vision.

Titian (Tiziano Vedellio, 1488/90 – 1576) Pastoral Concert (Fête champêtre), 1508-09, Oil/canvas

Titan, considered the most important Venetian artist of the 16th century, is believed to have been an assistant to both Bellini and Giorgione. It is also likely that, as a young ar4st, he studied the work of Michelangelo and Raphael through engravings.

Like Giorgione’s The Tempest, the painting poses questions as to its meaning, it, too, best interpreted within the context of pastoral poetry. A common subject of pastoral poetry concerned musical contests between shepherds in which contestants called upon the Muses for inspiration for their songs’ verses. The female figures, then, may represent muses, as such, not physically present, which would explain why the male figures do not notice them. The men, distinguished by their attire, may, in turn, represent a well-dressed, learned poet seeking inspiration from the songs of a rural shepherd.

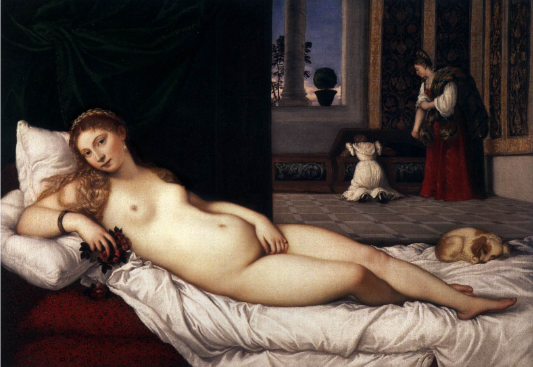

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1536-38. oil on canvas

Compared to Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, c, 1510, oil on canvas

One of the genres introduced to western art by the Venetian artists was the reclining female nude. Whereas Giorgione’s Venus was intended to represent the goddess (it had originally included a figure of Cupid, later painted out), Titian’s painting, although based on the Giorgione, likely was not. Instead, the subject was intended as a nude, painted for the pleasure of its patron, the soon to be Duke of Urbino, acquiring its title at a later date.

Both paintings present their subjects stretched languidly across the width of the canvases, each sensually posed. Whereas Giorgione’s Venus appears to be sleeping, thereby unaware of the gaze she inspires, Titian’s figure confronts the viewer directly, looking back with her own gaze. It is possible that Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus was completed by Titian, following Giorgione’s death.